Abstract

Interest in lateral-flow devices (LFDs) as potential point-of-care assays for the diagnosis of infectious diseases has increased. Our objective was to evaluate the interlaboratory and interstudy reproducibility and the effects of antifungal therapy on an LFD developed for invasive pulmonary aspergillosis (IPA) detection. An established neutropenic guinea pig model of IPA caused by Aspergillus fumigatus was used. At predetermined time points (1 h and 3, 5, and 7 days postinoculation), blood and bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid were collected from infected and uninfected animals. In a separate experiment, guinea pigs were treated with posaconazole (10 mg/kg of body weight orally [p.o.] twice a day [BID]), voriconazole (10 mg/kg p.o. BID), liposomal amphotericin B (10 mg/kg intraperitoneally [i.p.] once a day [QD]), or caspofungin (2 mg/kg i.p. QD), and samples were collected on days 7 and 11. Each laboratory independently evaluated the IgG monoclonal antibody-based LFD. Galactomannan and (1→3)-β-d-glucan were also measured using commercially available kits. Good interlaboratory agreement was observed with the LFD, as the results for 97% (32/33) of the serum and 78.8% (26/33) of the BAL fluid samples from infected animals were in agreement. Good interstudy agreement was also observed. The serum sensitivity of each surrogate-marker assay was reduced in animals treated with antifungals. In contrast, these markers remained elevated within the BAL fluids of treated animals, which was consistent with the fungal burden and histopathology results. These results demonstrate that the LFD assay is reproducible between different laboratories and studies. However, the sensitivity of this assay and other markers of IPA may be reduced with serum in the presence of antifungal therapy.

INTRODUCTION

Invasive pulmonary aspergillosis (IPA) remains a clinically challenging opportunistic fungal infection and leads to significant morbidity and mortality in heavily immunocompromised patients (1). Despite recent advances in antifungal pharmacology and the availability of agents with improved efficacy and safety, response rates in the treatment of IPA remain suboptimal. The prompt diagnosis of this disease can have a significant impact on patient outcomes, as the early diagnosis and initiation of antifungal therapy have been shown to reduce mortality in patients with invasive fungal infections, including IPA (2–4). Detection of IPA relies on supporting evidence from clinical, microbiological, radiological, serological, and histopathological investigations. Rapid diagnosis of this disease has focused on the detection of surrogate markers of infection, including components of the cell wall within different biological fluids, such as serum, bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid, and urine. Commercially available assays include those that detect galactomannan (GM) and (1→3)-β-d-glucan, which are now included in the diagnostic criteria for IPA (5). Although these tests have advanced the diagnosis of this invasive mycosis, they do have limitations, including the time required to run these assays and return the results to the clinicians and the equipment needed to perform the assays, as well as the potential for false-positive reactions. In addition, the sensitivity of these assays may be reduced with antifungal exposure (6–8).

Lateral-flow technology can be used to incorporate immunochromatographic assays into simple-to-use devices for point-of-care diagnosis of infectious diseases. These lateral-flow devices (LFDs) have been used in the diagnosis of diseases caused by bacteria, fungi, toxins, and viruses, including HIV (9–13). We have previously reported on the successful incorporation of an Aspergillus-specific murine monoclonal antibody (MAb) into an LFD. This monoclonal antibody (JF5 IgG3) binds to an extracellular glycoprotein antigen secreted constitutively during the active growth of Aspergillus hyphae (14). This LFD has been shown to be sensitive and specific for the rapid serodiagnosis of IPA in an established guinea pig model of this invasive fungal infection (15). Furthermore, recent studies have reported preliminary findings of the potential of the LFD to diagnose IPA in hematological malignancy patients by using BAL fluids (16, 17). Here, we expand upon these initial studies by investigating LFD detection of the Aspergillus antigen in guinea pig BAL fluid and serum samples simultaneously and comparing the results to those of commercial GM and (1→3)-β-d-glucan tests. In doing so, we (i) evaluate the interlaboratory variability of the LFD, (ii) determine the reproducibility of this assay between different studies, and (iii) assess the effects of antifungal exposure on this novel assay for IPA detection.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Isolate.

Aspergillus fumigatus clinical isolate 293 was grown on potato dextrose agar at 37°C for 7 days. Conidia were harvested by washing and scraping agar surfaces with 0.1% Tween 80 in sterile physiological saline and filtering for removal of hyphal fragments. Conidia were then concentrated through centrifugation and resuspended to give a final working concentration of ∼1 × 108 conidia/ml, which was measured with a hemocytometer and confirmed by enumeration of CFU.

Animal model.

Two days prior to infection, male Hartley guinea pigs (weight, 0.5 kg; Charles River Laboratories, Wilmington, MA) were rendered immunosuppressed with cyclophosphamide (250 mg/kg of body weight intraperitoneally [i.p.]; Mead Johnson, Princeton, NJ) and cortisone acetate (250 mg/kg subcutaneously; Sigma, St. Louis, MO). Additional doses of cyclophosphamide (200 mg/kg) and cortisone acetate (250 mg/kg) were administered on day 3 postinoculation (18). Ceftazidime (100 mg/kg subcutaneously) was administered daily for prevention of bacterial infections. Guinea pigs were exposed to A. fumigatus 293 conidia at 1 × 108 conidia/ml for 1 h in an aerosol chamber (18, 19). In the antifungal treatment, experiment guinea pigs were divided to receive one of five regimens beginning at 1 day postinoculation (n = 8 per group): (i) control, (ii) posaconazole at 10 mg/kg orally (p.o.) twice a day (BID), (iii) voriconazole at 10 mg/kg orally BID, (iv) liposomal amphotericin B at 10 mg/kg intraperitoneally once a day (QD), or (v) caspofungin at 2 mg/kg intraperitoneally QD. Treatment was continued through day 8, and animals were monitored off therapy until day 11. Uninfected immunosuppressed controls were also included in each experiment. All animal procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Texas (UT) Health Science Center at San Antonio, and animals were maintained in accordance with the Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care (20).

Sample collection.

Blood and BAL fluids were collected from animals at multiple time points in separate studies performed consecutively in 2010 and 2011. These were used to assess the interlaboratory and interstudy reproducibility of the LFD. In these studies, guinea pigs were challenged with A. fumigatus 293 conidia but were not treated with antifungal agents. Samples were collected from the animals at 1 h postchallenge and on days 3, 5, and 7. An additional study conducted in 2011 and 2012 assessed the effects of antifungal therapy on the sensitivity of the LFD, as well as the commercial GM and (1→3)-β-d-glucan assays. In this study, samples were collected on days 5, 7, and 11 postchallenge. In all three studies, blood was collected by cardiac puncture and allowed to clot, and the serum was collected following centrifugation. For BAL fluid, a catheter was inserted into the trachea, and 3 ml of sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) was instilled into the lungs, with a recovery volume of approximately 2 ml for each animal. The fluid was then carefully removed and placed into a sterile container. Samples were also collected from uninfected controls at each time point. The serum and BAL fluids were stored frozen at −80°C until assayed.

Lateral-flow device assay.

A previously described lateral-flow device was used to allow simple and rapid diagnosis of invasive aspergillosis (14, 15). Briefly, an IgG monoclonal antibody (JF5 IgG3) raised against an extracellular antigen secreted constitutively during the active growth of Aspergillus was immobilized to a defined capture zone on a porous nitrocellulose membrane. JF5 IgG was also conjugated to colloidal gold particles to serve as the detection reagent. The sample (100 μl of serum or BAL fluid) was added to a release pad containing the antibody-gold conjugate, which bound the target antigen, and then passed along the porous membrane by capillary action and bound to the antibody immobilized in the capture zone. Alternatively, processing was performed by mixing 50 μl of the sample with 100 μl of 4% sodium EDTA in PBS, followed by heating in a boiling water bath for 3 min (17). The mixture was then centrifuged for 5 min at 14,000 rpm, and 100 μl of the supernatant was added to the LFD. Test results were available within 10 to 15 min after loading the sample. Bound antigen-antibody-gold complex was observed as a red line with an intensity proportional to the antigen concentration, and results were recorded as weak positive (+), moderate positive (++), and strong positive (+++). Regardless of intensity, all positive test results indicate the presence of the JF5 antigen. Anti-mouse immunoglobulin immobilized to the membrane in a separate zone served as an internal control. In the absence of the Aspergillus antigen, no complex was formed in the zone containing solid-phase antibody, and a single internal control line was observed. This result was recorded as negative (−) for Aspergillus antigen.

(1→3)-β-d-Glucan and galactomannan assays.

The (1→3)-β-d-glucan assay was performed using a commercially available kit (Fungitell; Associates of Cape Cod, East Falmouth, MA). Five microliters of each sample was transferred in duplicate to a 96-well cell culture tray and processed according to the manufacturer's instructions. The mean rate of change in optical density (OD; 405 nm) over time was measured using a microplate spectrophotometer (Synergy HT; BioTek Instruments, Winooski, VT), and unknowns were interpolated from a standard curve. Galactomannan was also measured with a commercially available kit (Platelia Aspergillus enzyme immunoassay; Bio-Rad Laboratories). Three hundred microliters of each sample was heat treated following the addition of an EDTA acid solution. Fifty microliters of the treated supernatant was added to microwells containing conjugate and the rat monoclonal antibody EB-A2 and was allowed to incubate. The microwells were then washed and the substrate solution was added. The substrate solution formed a complex with the bound monoclonal antibody within the well, forming a blue color. The OD values of each sample, positive control, negative control, and cutoff control (supplied by the manufacturer) were measured using a microplate spectrophotometer at 450 and 630 nm, and the galactomannan index (GMI) was calculated as the OD of each sample divided by the mean cutoff of the control OD, as specified by the manufacturer.

Fungal burden and pulmonary histopathology.

Tissue fungal burden was measured by enumeration of CFU. Lungs from each animal were weighed, placed into sterile saline containing gentamicin and chloramphenicol, and homogenized, and the number of CFU per gram of lung tissue was determined as previously described (18, 21). In addition to serum and BAL fluid, lungs were collected for histopathology. This was done to compare the results of the various surrogate markers [LFD, (1→3)-β-d-glucan, and galactomannan] in the serum and BAL fluid with the extent of invasive disease within the lungs of animals treated with antifungal agents. Portions of the lungs at the different time points were placed into 10% (vol/vol) neutral buffered formaldehyde. The lungs were then processed and embedded into paraffin wax. Sections of embedded tissue were then stained with Gomori methenamine silver (GMS) stain in order to visualize the fungal elements within the lungs.

Data analysis.

Two separate laboratories, each blinded to the results of the other, performed the lateral-flow assay independently. Differences in the number of positive samples for the same animals per time point between the laboratories and different surrogate-marker assays were assessed for significance by Fisher's exact test, and a P value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant. The overall specificity of each assay was also measured with samples from uninfected controls. All statistical tests were performed using Prism (version 5.0) software (GraphPad Software, Inc.).

RESULTS

Interlaboratory reproducibility.

To compare the interlaboratory reproducibility of the LFD, two laboratories (Exeter and the UT Health Science Center at San Antonio) independently evaluated the samples collected from the same animals in the 2011 study by applying 100 μl of serum to the LFD and recording the results 10 to 15 min later. As shown in Tables 1 and 2, there was good agreement between the laboratories (90 to 100%) at each time point for the samples collected from infected animals as well as those collected from uninfected controls. When the samples were processed (50 μl of serum plus 100 μl 4% EDTA in PBS plus heating), results similar to those for unprocessed serum directly applied to the LFD were observed. However, the antigen appeared to be detected earlier in processed BAL fluid samples (6/10 positive from one laboratory and 10/10 positive from the second laboratory on day 3 postinoculation) than in those that were applied directly (2/10 positive on day 3). While the processing of the samples did increase the early sensitivity of the LFD by brightening the background of the device, it did not reduce the specificity, as all BAL fluid samples from the uninfected group were negative. These results suggest that serum samples may be directly applied to the LFD, while further processing may improve the ability of this device to detect the Aspergillus antigen within BAL fluid.

Table 1.

Interlaboratory comparison of LFD in serum from the 2011 studya

| Serum sample source and time point | No. of serum samples positive/total no. (%) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Laboratory 1 (unprocessed serum) | Laboratory 2 (unprocessed serum) | Serum LFD agreement between labs 1 and 2 | Laboratory 2 (processed serum) | |

| Infected guinea pigs | ||||

| 1 h | 0/3 | 0/3 | 3/3 (100) | 0/3 |

| Day 3 | 0/10 | 0/10 | 10/10 (100) | 2/10 |

| Day 5 | 4/10 | 5/10 | 9/10 (90) | 7/10 |

| Day 7 | 7/10 | 7/10 | 10/10 (100) | 8/10 |

| Aggregate agreement between laboratories | 32/33 (97) | |||

| Uninfected guinea pigs | ||||

| 1 h | 0/3 | 0/3 | 3/3 (100) | 0/3 |

| Day 3 | 0/3 | 0/3 | 3/3 (100) | 0/3 |

| Day 5 | 0/3 | 0/3 | 3/3 (100) | 1/3 |

| Day 7 | 2/3 | 2/3 | 3/3 (100) | 2/3 |

| Aggregate agreement between laboratories | 12/12 (100) | |||

The unprocessed samples (100 μl) were applied directly to the LFD and the results were read 10 to 15 min later. For the processed samples, 50 μl of the serum was mixed with 100 μl of 4% sodium EDTA in PBS, followed by heating for 3 min in a boiling water bath and centrifugation. The supernatant (100 μl) was then applied to the LFD. Agreement between labs for unprocessed serum samples is calculated between individual animals.

Table 2.

Interlaboratory comparison of LFD in BAL fluid samples from the 2011 studya

| BAL fluid sample source and time point | No. of BAL fluid samples positive/total no. (%) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Laboratory 1 (processed BAL fluid) | Laboratory 2 (processed BAL fluid) | BAL fluid LFD agreement between labs 1 and 2 | Laboratory 1 (unprocessed BAL fluid) | |

| Infected guinea pigs | ||||

| 1 h | 0/3 | 0/3 | 3/3 (100) | 0/3 |

| Day 3 | 6/10 | 10/10 | 6/10 (60) | 2/10 |

| Day 5 | 10/10 | 10/10 | 10/10 (100) | 10/10 |

| Day 7 | 7/10 | 10/10 | 7/10 (70) | 9/10 |

| Aggregate agreement between laboratories | 26/33 (78.8) | |||

| Uninfected guinea pigs | ||||

| 1 h | 0/3 | 0/3 | 3/3 (100) | 0/3 |

| Day 3 | 0/3 | 0/3 | 3/3 (100) | 0/3 |

| Day 5 | 0/3 | 0/3 | 3/3 (100) | 0/3 |

| Day 7 | 0/3 | 0/3 | 3/3 (100) | 0/3 |

| Aggregate agreement between laboratories | 12/12 (100) | |||

The unprocessed samples (100 μl) were applied directly to the LFD and the results were read 10 to 15 min later. For the processed samples, 50 μl of the BAL fluid was mixed with 100 μl of 4% sodium EDTA in PBS, followed by heating for 3 min in a boiling water bath and centrifugation. The supernatant (100 μl) was then applied to the LFD. Agreement between labs for processed BAL samples is calculated between individual animals.

Interstudy reproducibility.

We also evaluated the reproducibility of the LFD for the detection of IPA by comparing the results for the 2010 and 2011 studies. The results for the LFD, (1→3)-β-d-glucan, and galactomannan assays with serum and BAL fluid samples collected in the consecutive studies are shown in Table 3. Overall, the results from the two studies conducted with this model were comparable, both for serum and for BAL fluids. There were fewer positive samples with the LFD with serum collected earlier in the course of infection in the 2011 study than in the one conducted previously; however, these differences were not significant. In addition, these results were similar to those of the clinically available assays for (1→3)-β-d-glucan and galactomannan, as there were no significant differences in the number of samples that were positive between the different assays at each time point. Although the cumulative results suggest that the LFD became positive with serum collected earlier in the course of the infection than the (1→3)-β-d-glucan assay (40% versus 5.7% positive rate in infected animals on day 3; P < 0.01), this outcome was not consistent between studies. There were also significantly fewer positive tests with BAL fluid collected from uninfected controls with the LFD than with the (1→3)-β-d-glucan and galactomannan assays (P < 0.01). These data demonstrate that the LFD assay is reproducible with consistent and specific results with serum and BAL fluid between different experiments.

Table 3.

Comparison of LFD, (1→3)-β-d-glucan, and galactomannan assays with serum and BAL fluid samples for the 2010 and 2011 studies, as well as cumulative results for each surrogate marker

| Sample, source, and time point | No. of positive results/no. of samples tested by the indicated assay (%) |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2010 |

2011 |

Cumulative results |

|||||||

| LFD | β-Glucan | GM | LFD | β-Glucan | GM | LFD | β-Glucan | GM | |

| Serum | |||||||||

| Infected guinea pigs | |||||||||

| 1 h | 0/5 | 0/5 | 1/5 | 0/3 | 0/2 | 0/3 | 0/8 (0) | 0/7 (0) | 1/8 (12.5) |

| Day 3 | 12/25 | 0/25 | 1/25 | 2/10 | 2/10 | 5/10 | 14/35 (40) | 2/35 (5.7) | 6/35 (17.1) |

| Day 5 | 14/17 | 4/17 | 10/17 | 5/10 | 4/10 | 7/10 | 19/27 (70.4) | 8/27 (29.6) | 17/27 (70) |

| Day 7 | 6/6 | 6/6 | 6/6 | 7/10 | 7/10 | 8/10 | 13/16 (81.2) | 13/16 (81.2) | 14/16 (87.5) |

| Uninfected guinea pigs | 0/10 | 2/10 | 0/10 | 2/12 | 2/10 | 4/12 | 2/22 (9.1) | 4/20 (20) | 4/22 (18.2) |

| BAL fluid | |||||||||

| Infected guinea pigs | |||||||||

| 1 h | 0/15 | 4/10 | 0/10 | 0/3 | 0/2 | 0/3 | 0/18 (0) | 4/12 (33) | 0/13 (0) |

| Day 3 | 10/15 | 10/10 | 8/10 | 10/10 | 10/10 | 10/10 | 20/25 (80) | 20/20 (100) | 18/20 (90) |

| Day 5 | 12/15 | 10/10 | 10/10 | 10/10 | 10/10 | 10/10 | 22/25 (88) | 20/20 (100) | 20/20 (100) |

| Day 7 | 14/14 | 10/10 | 10/10 | 10/10 | 10/10 | 10/10 | 24/24 (100) | 20/20 (100) | 20/20 (100) |

| Uninfected guinea pigs | 0/21 | 7/16 | 5/16 | 0/12 | 2/10 | 1/12 | 0/33 (0) | 9/26 (34.6) | 6/28 (21) |

Influence of antifungal therapy on LFD, (1→3)-β-d-glucan, and galactomannan assays.

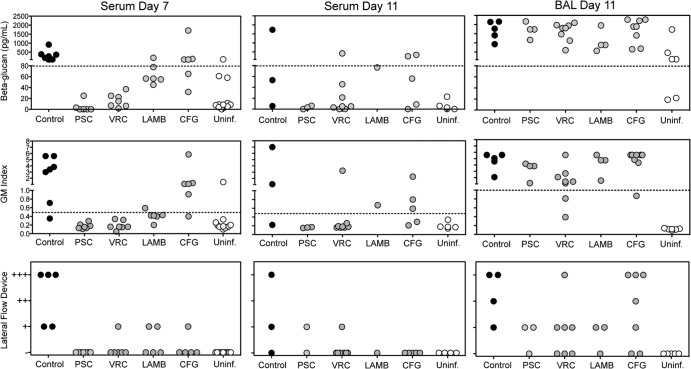

We also evaluated whether exposure to antifungal agents would affect the ability of the LFD, (1→3)-β-d-glucan, and galactomannan assays to detect their respective surrogate markers of IPA in both serum and BAL fluids. Both (1→3)-β-d-glucan concentrations and the GM index were lower for the serum of animals that received antifungal therapy than the serum of untreated controls (Fig. 1). This was especially evident with posaconazole, voriconazole, and liposomal amphotericin B, as these surrogate markers were below the threshold of positivity [(1→3)-β-d-glucan, 80 pg/ml; serum GM index, 0.5) in the majority of guinea pigs at day 7 [1 positive result for both the (1→3)-β-d-glucan and galactomannan assays in 19 tested samples from infected guinea pigs]. In contrast, the two markers within the serum were above these thresholds in most animals treated with caspofungin. The results of the LFD were also affected by antifungal exposure, as at this time point, most serum samples from animals that received antifungal therapy were negative, including those samples taken from animals that received caspofungin (4 positive results from 22 tested samples). In contrast, the majority of samples collected from untreated infected controls were positive with each assay. Similar results were also observed on day 11.

Fig 1.

(1→3)-β-d-Glucan, galactomannan, and LFD results using serum and BAL fluid from guinea pigs with invasive aspergillosis that were exposed to antifungal agents. Antifungal therapy with posaconazole (PSC; 10 mg/kg p.o. BID), voriconazole (VRC; 10 mg/kg p.o. BID), liposomal amphotericin B (LAMB; 10 mg/kg i.p. QD), or caspofungin (CFG; 2 mg/kg i.p. QD) began 1 day after aerosol inoculation and continued through day 8. Serum samples were collected on day 7 and day 11 from animals that survived to the study endpoint, and BAL fluid samples were collected on day 11. Uninf., uninfected.

The results with the serum of animals that received antifungal therapy are in contrast to what was observed with the BAL fluid and the fungal burden data. As shown in Fig. 1, the majority of BAL fluid samples remained positive with each assay, despite exposure to antifungal agents. For the assay of galactomannan in the BAL fluid samples, a GM index of ≥1.0 was considered the threshold value for positivity. The results for all three diagnostic tests with BAL fluid are in agreement with the pulmonary fungal burden data, as the CFU counts within the lungs of the animals that received therapy (mean range, 3.26 to 3.95 log10 CFU/g) did not differ significantly from those within the lungs of the untreated controls (3.84 log10 CFU/g), regardless of the antifungal agent that was used (Fig. 2). Invasive hyphae were also seen in the infected controls as well as those treated with liposomal amphotericin B or caspofungin (representative histopathology sections are shown in Fig. 2). Although lung damage was observed in animals treated with posaconazole, no hyphae were observed. For voriconazole, no hyphae were visible and little damage was found within these sections. It is unclear from these data if the histopathology results are due to sampling bias for posaconazole and voriconazole or if hyphae were absent but the lung fungal burden and surrogate-marker results were caused by the presence of germlings or fragmented hyphae secondary to antifungal exposure. Aspergillus colonies were not detected within the lungs of uninfected controls. This is consistent with the results of the galactomannan and LFD assays, which were negative with the BAL fluid. However, the (1→3)-β-d-glucan assay was positive with the majority of BAL fluid samples collected from uninfected controls.

Fig 2.

Pulmonary fungal burden (A) and representative histopathology sections (B) for guinea pigs that received antifungal therapy. Antifungal therapy with posaconazole (PSC; 10 mg/kg p.o. BID), voriconazole (VRC; 10 mg/kg p.o. BID), liposomal amphotericin B (LAMB; 10 mg/kg i.p. QD), or caspofungin (CFG; 2 mg/kg i.p. QD) began 1 day after aerosol inoculation and continued through day 8. Lungs were collected on day 11 or when the animals succumbed to infection, and the lines depict the median log10 numbers of CFU/g. For histopathology, lung sections were stained with GMS and viewed at ×200 magnification by light microscopy.

DISCUSSION

The prompt diagnosis of invasive pulmonary aspergillosis can have significant impacts on patient outcomes. Early diagnosis and initiation of antifungal therapy have been shown to reduce mortality in patients with invasive fungal infections, including IPA (2–4). In the absence of a single “gold standard” test, the diagnosis of this opportunistic mycosis relies on clinical data and microbiology and histopathology, where feasible. Rapid diagnosis of this disease has focused on the detection of surrogate markers of infection within the serum and BAL fluid. Two commercially available tests for measuring surrogate markers of invasive aspergillosis include the Fungitell (1→3)-β-d-glucan and Platelia Aspergillus galactomannan assays. The Fungitell test is a chromogenic assay based on the activation of the horseshoe crab coagulation cascade by (1→3)-β-d-glucan and uses amebocyte enzymes from Limulus polyphemus (22). When this fungal cell wall component is present, the coagulation cascade is triggered and ultimately results in the release of a chromogenic peptide that can be measured using a microplate spectrophotometer. The Platelia Aspergillus enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay kit (Bio-Rad) uses a rat monoclonal antibody (EB-A2) directed against the immunodominant epitope within galactomannan, a cell wall component of Aspergillus released during growth (23–25). Both assays have improved the diagnosis of IPA and are part of the Infectious Diseases Society of America guidelines for diagnosis of this invasive fungal infection (5). However, these assays do have limitations, including the need for dedicated time and equipment to perform the tests, which may increase the time that it takes for the results to reach clinicians and delay the start of appropriate antifungal therapy. Thus, there is a need for the development of point-of-care devices, such as LFDs, that allow the rapid, reliable, and routine testing of samples from patients at high risk for IPA.

We have previously reported the development of an LFD that utilizes an IgG3 MAb, JF5, that binds to an extracellular antigen secreted constitutively during the active growth of Aspergillus. The JF5 monoclonal antibody reacts strongly with antigens from Aspergillus species but does not react with other pathogenic fungi, including Candida species, Cryptococcus neoformans, Fusarium species, Scedosporium prolificans, Pseudallescheria boydii, or the causative agents of mucormycosis (14). Benefits of this investigational assay include the short time needed to obtain results (10 to 15 min) and the minimal processing of samples. In addition, the LFD became positive early during the course of infection in a previous study with this guinea pig model of IPA, while maintaining specificity with negative results for uninfected controls (15). However, in the present study, the earlier detection of the antigen with the LFD was not consistent for all experiments. This is likely due to the inherent variability of animal responses to infection and the associated production of diagnostic markers in each set of experiments, and further work is needed to determine the consistency of the LFD in detecting disease earlier than surrogate-marker assays.

The results of the current study are encouraging, as they demonstrated that the results of this LFD are reproducible between laboratories and different studies. Little variance was observed between the two laboratories, and the cumulative results of this study and our previous work show that this assay is comparable to the clinically available assays for the detection of (1→3)-β-d-glucan and galactomannan. We also demonstrate that the sensitivity of the LFD with BAL fluid may be improved with minimal sample processing without compromising its specificity, as there were significantly fewer positive samples from uninfected guinea pigs with this test than with the other assays.

However, the sensitivity of the LFD, along with that of the (1→3)-β-d-glucan and galactomannan tests, was affected by antifungal exposure. The ability of each diagnostic assay to detect the surrogate markers of disease within the serum was reduced in animals exposed to antifungals. These results are consistent with previous reports of the reduced sensitivity of the (1→3)-β-d-glucan and galactomannan assays in patients with IPA who received antifungal therapy (6, 8). In our study, this most likely represents the suppression of disease dissemination and reduction of the Aspergillus antigens within the sera to levels below the limit of detection for each surrogate-marker assay but not clearance of the disease from the lungs, as the pulmonary fungal burden remained elevated even in animals that received antifungal therapy. In addition, positive results were observed with the BAL fluid samples for each diagnostic assay. We have previously demonstrated that commonly used antifungals and antibiotics at clinically relevant concentrations do not result in false-positive or false-negative results with the LFD (26).

Although the results of this study are promising, one limitation is that this LFD has been evaluated in only one animal model of IPA. Thus, there is a need for additional studies with this assay. In addition, positive results occurred with each surrogate-marker assay with some samples collected from uninfected controls. As these guinea pigs were not exposed to A. fumigatus conidia via the aerosol chamber and were separated from the infected control group throughout the course of these experiments and fungal colonies were not detected within the lungs, this most likely represents environmental exposure to Aspergillus antigens. The sterile food and bedding used in the housing of these animals tested positive by each surrogate-marker assay used in these studies and may be a source of these antigens (data not shown). Finally, while the results with a small number of clinical samples have been promising (14), a larger number of samples from patients with proven or probable IPA need to be evaluated in order to confirm the potential clinical utility of this LFD for the diagnosis of this infectious disease.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Marcos Olivo for his assistance with the animal models.

This work was supported by contracts from the National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIH/NIAID; contract numbers N01-AI-30041 and HHSN272201000038I/HHSN27200002—task order A05) to T. F. Patterson and NIH/NIAID grant R21AI085393 to N. P. Wiederhold and C. R. Thornton.

N.P.W. has received research support from Pfizer, Schering-Plough, Merck, Basilea, and Astellas and has served on advisory boards for Merck, Astellas, Toyama, and Viamet. T.F.P. has received research grants to the UT Health Science Center at San Antonio from Astellas, Basilea, Merck, and Pfizer and has served as a consultant for Astellas, Basilea, Merck, Pfizer, and Toyama. C.R.T. has received support from Pfizer. None of the other authors has a conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 21 November 2012

REFERENCES

- 1. Lin SJ, Schranz J, Teutsch SM. 2001. Aspergillosis case-fatality rate: systematic review of the literature. Clin. Infect. Dis. 32:358–366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Caillot D, Casasnovas O, Bernard A, Couaillier JF, Durand C, Cuisenier B, Solary E, Piard F, Petrella T, Bonnin A, Couillault G, Dumas M, Guy H. 1997. Improved management of invasive pulmonary aspergillosis in neutropenic patients using early thoracic computed tomographic scan and surgery. J. Clin. Oncol. 15:139–147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Garey KW, Rege M, Pai MP, Mingo DE, Suda KJ, Turpin RS, Bearden DT. 2006. Time to initiation of fluconazole therapy impacts mortality in patients with candidemia: a multi-institutional study. Clin. Infect. Dis. 43:25–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Greene RE, Schlamm HT, Oestmann JW, Stark P, Durand C, Lortholary O, Wingard JR, Herbrecht R, Ribaud P, Patterson TF, Troke PF, Denning DW, Bennett JE, de Pauw BE, Rubin RH. 2007. Imaging findings in acute invasive pulmonary aspergillosis: clinical significance of the halo sign. Clin. Infect. Dis. 44:373–379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Walsh TJ, Anaissie EJ, Denning DW, Herbrecht R, Kontoyiannis DP, Marr KA, Morrison VA, Segal BH, Steinbach WJ, Stevens DA, van Burik JA, Wingard JR, Patterson TF. 2008. Treatment of aspergillosis: clinical practice guidelines of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin. Infect. Dis. 46:327–360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Marr KA, Laverdiere M, Gugel A, Leisenring W. 2005. Antifungal therapy decreases sensitivity of the Aspergillus galactomannan enzyme immunoassay. Clin. Infect. Dis. 40:1762–1769 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. McCulloch E, Ramage G, Rajendran R, Lappin DF, Jones B, Warn P, Shrief R, Kirkpatrick WR, Patterson TF, Williams C. 2012. Antifungal treatment affects the laboratory diagnosis of invasive aspergillosis. J. Clin. Pathol. 65:83–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Senn L, Robinson JO, Schmidt S, Knaup M, Asahi N, Satomura S, Matsuura S, Duvoisin B, Bille J, Calandra T, Marchetti O. 2008. 1,3-beta-d-Glucan antigenemia for early diagnosis of invasive fungal infections in neutropenic patients with acute leukemia. Clin. Infect. Dis. 46:878–885 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Iweala OI. 2004. HIV diagnostic tests: an overview. Contraception 70:141–147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Jarvis JN, Percival A, Bauman S, Pelfrey J, Meintjes G, Williams GN, Longley N, Harrison TS, Kozel TR. 2011. Evaluation of a novel point-of-care cryptococcal antigen test on serum, plasma, and urine from patients with HIV-associated cryptococcal meningitis. Clin. Infect. Dis. 53:1019–1023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ketema F, Zeh C, Edelman DC, Saville R, Constantine NT. 2001. Assessment of the performance of a rapid, lateral flow assay for the detection of antibodies to HIV. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 27:63–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Sharma SK, Eblen BS, Bull RL, Burr DH, Whiting RC. 2005. Evaluation of lateral-flow Clostridium botulinum neurotoxin detection kits for food analysis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71:3935–3941 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Smits HL, Eapen CK, Sugathan S, Kuriakose M, Gasem MH, Yersin C, Sasaki D, Pujianto B, Vestering M, Abdoel TH, Gussenhoven GC. 2001. Lateral-flow assay for rapid serodiagnosis of human leptospirosis. Clin. Diagn. Lab. Immunol. 8:166–169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Thornton CR. 2008. Development of an immunochromatographic lateral-flow device for rapid serodiagnosis of invasive aspergillosis. Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 15:1095–1105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Wiederhold NP, Thornton CR, Najvar LK, Kirkpatrick WR, Bocanegra R, Patterson TF. 2009. Comparison of lateral flow technology and galactomannan and (1→3)-beta-d-glucan assays for detection of invasive pulmonary aspergillosis. Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 16:1844–1846 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hoenigl M, Koidl C, Duettmann W, Seeber K, Wagner J, Buzina W, Wolfler A, Raggam RB, Thornton CR, Krause R. 2012. Bronchoalveolar lavage lateral-flow device test for invasive pulmonary aspergillosis diagnosis in haematological malignancy and solid organ transplant patients. J. Infect. 65:588–591 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Thornton C, Johnson G, Agrawal S. 2012. Detection of invasive pulmonary aspergillosis in haematological malignancy patients by using lateral-flow technology. J. Vis. Exp. pii=e3721. doi:10.3791/3721 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Vallor AC, Kirkpatrick WR, Najvar LK, Bocanegra R, Kinney MC, Fothergill AW, Herrera ML, Wickes BL, Graybill JR, Patterson TF. 2008. Assessment of Aspergillus fumigatus burden in pulmonary tissue of guinea pigs by quantitative PCR, galactomannan enzyme immunoassay, and quantitative culture. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 52:2593–2598 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Sheppard DC, Rieg G, Chiang LY, Filler SG, Edwards JE, Jr, Ibrahim AS. 2004. Novel inhalational murine model of invasive pulmonary aspergillosis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 48:1908–1911 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. National Research Council 1996. Guide for the care and use of laboratory animals. National Academies Press, Washington, DC [Google Scholar]

- 21. Sheppard DC, Graybill JR, Najvar LK, Chiang LY, Doedt T, Kirkpatrick WR, Bocanegra R, Vallor AC, Patterson TF, Filler SG. 2006. Standardization of an experimental murine model of invasive pulmonary aspergillosis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 50:3501–3503 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Associates of Cape Cod Inc 2008. Assay for (1,3)-beta-d-glucan in serum. Associates of Cape Cod Inc, East Falmouth, MA [Google Scholar]

- 23. Morelle W, Bernard M, Debeaupuis JP, Buitrago M, Tabouret M, Latge JP. 2005. Galactomannoproteins of Aspergillus fumigatus. Eukaryot. Cell 4:1308–1316 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Stynen D, Goris A, Sarfati J, Latge JP. 1995. A new sensitive sandwich enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay to detect galactofuran in patients with invasive aspergillosis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 33:497–500 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Stynen D, Sarfati J, Goris A, Prevost MC, Lesourd M, Kamphuis H, Darras V, Latge JP. 1992. Rat monoclonal antibodies against Aspergillus galactomannan. Infect. Immun. 60:2237–2245 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Wiederhold NP, Thornton CR. 2011. Lack of cross-reactivity and interference of commonly used intravenous antimicrobials with a lateral-flow device for the diagnosis of invasive aspergillosis, abstr M-1538. Abstr. 51st Intersci. Conf. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother., Chicago, IL American Society for Microbiology, Washington, DC [Google Scholar]