Abstract

Mycoplasmas, which have been shown to be the causative pathogens in recent human pneumonia epidemics, bind to solid surfaces and glide in the direction of the membrane protrusion at a pole. During gliding, the legs of the mycoplasma catch, pull, and release sialylated oligosaccharides fixed on a solid surface. Sialylated oligosaccharides are major structures on animal cell surfaces and are sometimes targeted by pathogens, such as influenza virus. In the present study, we analyzed the inhibitory effects of 16 chemically synthesized sialylated compounds on the gliding and binding of Mycoplasma mobile and Mycoplasma pneumoniae and concluded the following. (i) The recognition of sialylated oligosaccharide by mycoplasma legs proceeds in a “lock-and-key” fashion, with the binding affinity dependent on structural differences among the sialylated compounds examined. (ii) The binding of the leg and the sialylated oligosaccharide is cooperative, with Hill constants ranging from 2 to 3. (iii) Mycoplasma legs may generate a drag force after a stroke, because the gliding speed decreased and pivoting motion occurred more frequently when the number of working legs was reduced by the addition of free sialylated compounds.

INTRODUCTION

Mycoplasmas are commensal and occasionally parasitic bacteria with small genomes that lack a peptidoglycan layer (1). Several mycoplasma species form membrane protrusions (2–4), such as the head-like structure in Mycoplasma mobile and the attachment organelle in Mycoplasma pneumoniae, a pathogen that has been epidemic in recent years (5, 6). On solid surfaces, these species exhibit gliding motility in the direction of the protrusion; this motility appears to be involved in the parasitism of mycoplasmas (2, 7–9). Interestingly, mycoplasmas have no flagella or pili, and their genomes contain no genes related to known bacterial motility. In addition, no homologs of motor proteins that are common in eukaryotic motility have been found (3, 10).

M. mobile, isolated from the gills of a freshwater fish, is a fast-gliding mycoplasma (11–15). It glides smoothly and continuously on glass at an average speed of 2.0 to 4.5 μm/s, or three to seven times the length of the cell per second, exerting a force of up to 27 pN. The gliding machinery formed at the base of the membrane protrusion is composed of hundreds of units, with a flexible leg protruding from each (16–21). The legs are composed of a 349-kDa protein, Gli349, and are likely to bind and pull the solid surface, based on the energy of ATP hydrolysis (22–24). The outline of this putative mechanism may apply to M. pneumoniae, as well, although the protein responsible for glass binding, P1 adhesin, is not similar in amino acid sequence to M. mobile Gli349 (25, 26).

The gliding motility of mycoplasmas can be easily observed on glass surfaces, although mycoplasmas live in animal tissues in nature, suggesting that their intrinsic binding target is a surface structure of animal cells or the extracellular matrix. In a previous study, the binding of M. mobile to glass was inhibited by the addition of free sialyllactose, indicating that gliding cells of M. mobile bind to sialylated oligosaccharides (from serum in the medium) that are attached to the glass (27). In most observations, M. mobile cells bind to sialylated oligosaccharides on sialoproteins provided from serum included in the medium. However, the previous study did not clarify the structure of the sialylated oligosaccharides recognized by M. mobile. In addition, previous studies suggested that detailed analyses of binding inhibition would provide valuable information about the leg behaviors, which is essential to unveil the mechanism of mycoplasma gliding (19, 20, 26–28). In the present study, we analyze the inhibitory effects of 16 sialylated compounds on binding and gliding of M. mobile and M. pneumoniae and suggest the mechanism of recognition and possible leg movements.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cultivation.

M. mobile strain 163K (ATCC 43663) and M. pneumoniae M129 (the type strain of group I) were grown as previously described (14, 29).

Sialylated compounds.

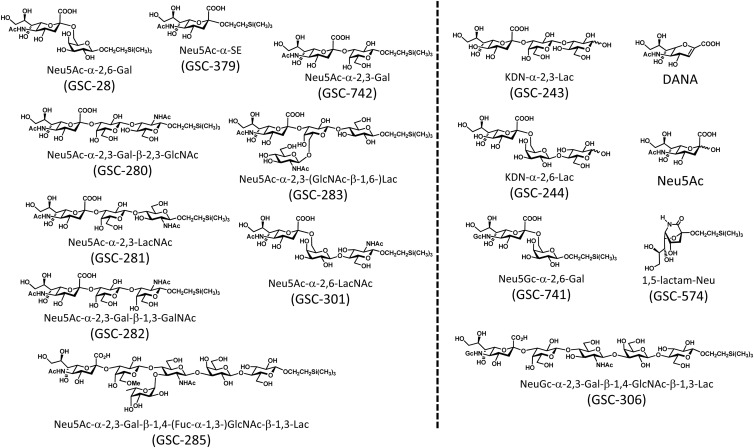

The compounds listed in Fig. 1 (GSC-28, GSC-243, GSC-244, GSC-280, GSC-281, GSC-282, GSC-283, GSC-285, GSC-301, GSC-306, GSC-379, GSC-574, GSC-741, GSC-742, DANA, and Neu5Ac) were synthesized according to the procedures described previously (30–36).

Fig 1.

The 16 sialylated compounds used in this study. The compounds on the left side of the dashed line showed inhibitory effects on mycoplasma binding and gliding.

Analyzing inhibitory effects of compounds.

To analyze the inhibition of binding, the mycoplasma suspension was mixed with sialylated compounds and inserted into a tunnel chamber (5-mm interior width, 22-mm length, 86-μm wall thickness). The tunnel chamber was constructed with a coverslip and a glass slide, assembled with double-sided tape, and precoated with growth medium containing horse serum for 60 min (22, 27, 37). For observation of M. pneumoniae, the microscope was kept at 37°C with an HT 200 stage heater (Minitube, Verona, WI) and a lens heater (MATS-LH; Tokai Hit, Shizuoka, Japan) (26, 38, 39). To analyze the removal of cells by sialylated oligosaccharides for each species, the cell suspension was inserted into a tunnel chamber kept at the appropriate temperature. After 30 min, a sialylated compound was inserted into the chamber with continuous video recording. The mycoplasmas were observed and analyzed as previously reported (27, 37, 39).

RESULTS

Time course of mycoplasma binding to the glass surface.

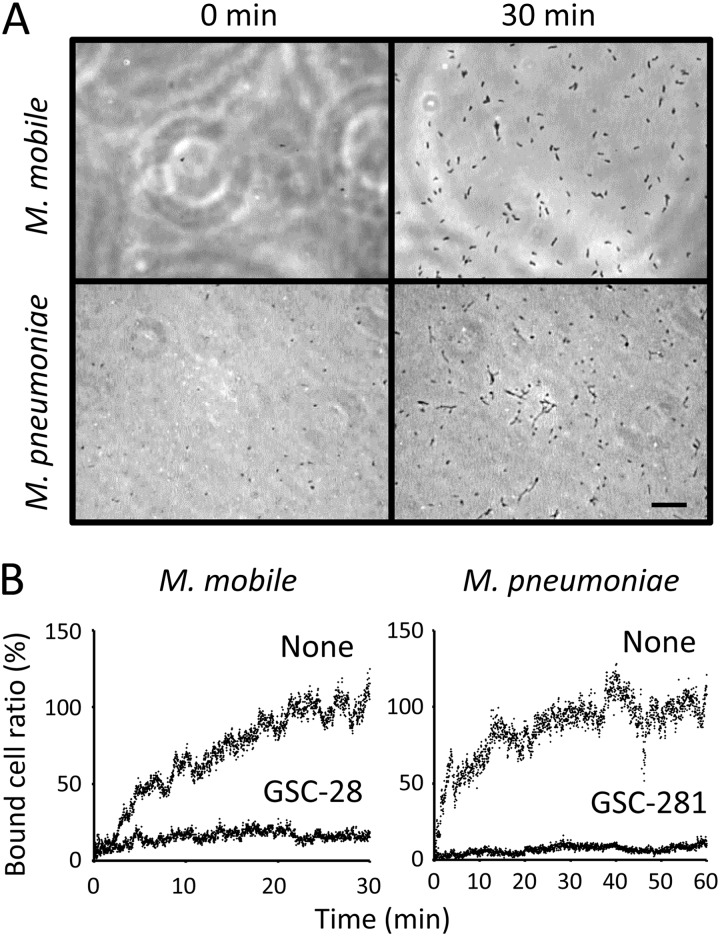

M. mobile cells suspended in buffer were inserted into a tunnel chamber precoated with the growth medium and observed for binding to glass at room temperature by phase-contrast microscopy (Fig. 2A). M. mobile started to bind to the glass from time zero, and the bound cells saturated the surface of the glass at 30 min, with about 130 cells bound to a glass area 64.0 μm wide and 85.3 μm long (Fig. 2B; see Movie S1 in the supplemental material). Ninety-eight percent of the bound cells were gliding.

Fig 2.

Time course of mycoplasma binding to a glass surface. (A) Images of the glass surface at different time points. A mycoplasma suspension was inserted into a tunnel chamber, and an area of glass surface 64.0 μm wide and 85.3 μm long was observed. Bar, 10 μm. (B) Number of bound cells. Bound cells were counted every second and are presented as a ratio to the numbers at 30 and 60 min without sialylated compounds. The binding of M. mobile and M. pneumoniae was examined in the presence of 0.05 mM sialylated compounds, as indicated in each graph. For the analyses of M. pneumoniae, the gliding cells were counted as the number of bound cells.

M. pneumoniae cells suspended in buffer were inserted into a tunnel chamber and observed at 37°C (Fig. 2B). M. pneumoniae started to bind to the glass surface from time zero, and the bound cells saturated the surface of the glass at 60 min. About 180 cells were observed to bind to a glass area 64.0 μm wide and 85.3 μm long, of which one-third were gliding and two-thirds were not.

In the following experiments, the bound cells were counted at 30 and 60 min after insertion for M. mobile and M. pneumoniae, respectively.

Inhibition of mycoplasma binding by free sialylated compounds.

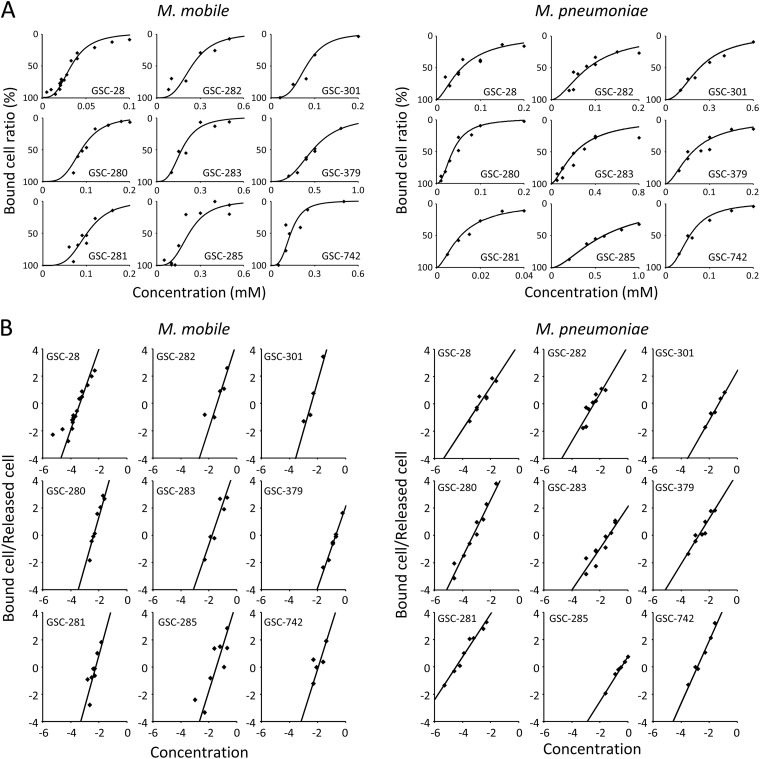

The binding of mycoplasmas to glass was inhibited by the presence of free sialylated oligosaccharides, consistent with the previous studies (27, 40, 41) (Fig. 2B). We examined the inhibitory effects of 16 chemically synthesized sialylated compounds. The cell suspension was mixed with various concentrations of free sialylated compounds and inserted into the tunnel chamber. The bound cells were counted after 30 and 60 min for M. mobile and M. pneumoniae, respectively. For the analyses of M. pneumoniae, we took the number of gliding cells as the number of bound cells, because binding of nongliding cells was not affected by the addition of free sialylated oligosaccharides, probably because P1 adhesin does not displace in that state. Nine of 16 sialylated compounds showed inhibitory effects on mycoplasma binding (Fig. 3A). Next, we measured the concentration dependence of the inhibitory effect on binding for the 9 effective compounds. The most effective compounds were GSC-28 and Neu5Ac-α-2,6-galactose for M. mobile and GSC-281 and Neu5Ac-α-2,3-lactosamine for M. pneumoniae. The concentration dependence of the inhibitory effects clearly revealed that there was cooperation for both mycoplasmas. In the analyses by Hill plot (Fig. 3B), all the results fit onto a line on the Hill equation-based plot. The Hill constants and affinities were calculated from the slope and intercept of the plot, respectively, as summarized in Table 1. The affinities of the most effective compounds, GSC-28 and GSC-281 for M. mobile and M. pneumoniae, were 4.10 × 10−5 mM and 8.82 × 10−4 mM, respectively. The Hill constants for the 9 compounds ranged from 3 to 4 for M. mobile and from 1.5 to 2.5 for M. pneumoniae. All of the effective compounds featured N-acetylneuraminic acid at the nonreducing end. Modifications in the side chain, different numbers of sugars, and changes in the level of sialic acid affected the affinity, as shown by GSC-283, GSC-285, and GSC-379, respectively.

Fig 3.

Inhibition of mycoplasma binding by sialylated compounds. (A) Concentration dependence of binding inhibition. A mycoplasma suspension was mixed with the sialylated compound indicated in each graph at various concentrations and inserted into a tunnel chamber. The M. mobile and M. pneumoniae cells bound to the glass surface were counted after 30 and 60 min, respectively. The numbers of bound cells are presented as a ratio to those without sialylated compounds. (B) Hill plot analysis of the data in panel A. The axes are logarithmic. The affinities and Hill constants are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Affinities, Hill constants, and removal rates of compounds on mycoplasma bindinga

| Compound |

M. mobile |

M. pneumoniae |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Affinityb (mM) | Hill constant | Ratec (s−1) | Affinityb (mM) | Hill constant | Ratec (s−1) | |

| GSC-28 | 4.10 × 10−5 | 2.96 | 0.116 | 1.23 × 10−2 | 1.57 | 0.026 |

| GSC-280 | 1.47 × 10−4 | 3.64 | 0.06 | 1.00 × 10−3 | 2.10 | 0.052 |

| GSC-281 | 1.79 × 10−4 | 3.77 | 0.073 | 8.82 × 10−4 | 1.57 | 0.069 |

| GSC-282 | 1.08 × 10−2 | 3.20 | 0.049 | 1.36 × 10−2 | 1.75 | 0.031 |

| GSC-283 | 5.10 × 10−3 | 3.00 | 0.044 | 1.23 × 10−1 | 1.52 | 0.01 |

| GSC-285 | 7.45 × 10−3 | 3.31 | 0.042 | 4.41 × 10−1 | 1.63 | 0.005 |

| GSC-301 | 1.24 × 10−4 | 3.60 | 0.064 | 8.50 × 10−2 | 1.80 | 0.009 |

| GSC-379 | 1.20 × 10−1 | 2.95 | 0.019 | 1.02 × 10−2 | 1.66 | 0.021 |

| GSC-742 | 1.54 × 10−3 | 3.25 | 0.071 | 1.37 × 10−3 | 2.29 | 0.039 |

No affinity was observed for the compounds shown on the right side of the dashed line in Fig. 1.

The highest affinity is underlined.

Rate of decrease in cell numbers on glass on removal of gliding mycoplasmas.

Removal of gliding mycoplasmas by free sialylated compounds.

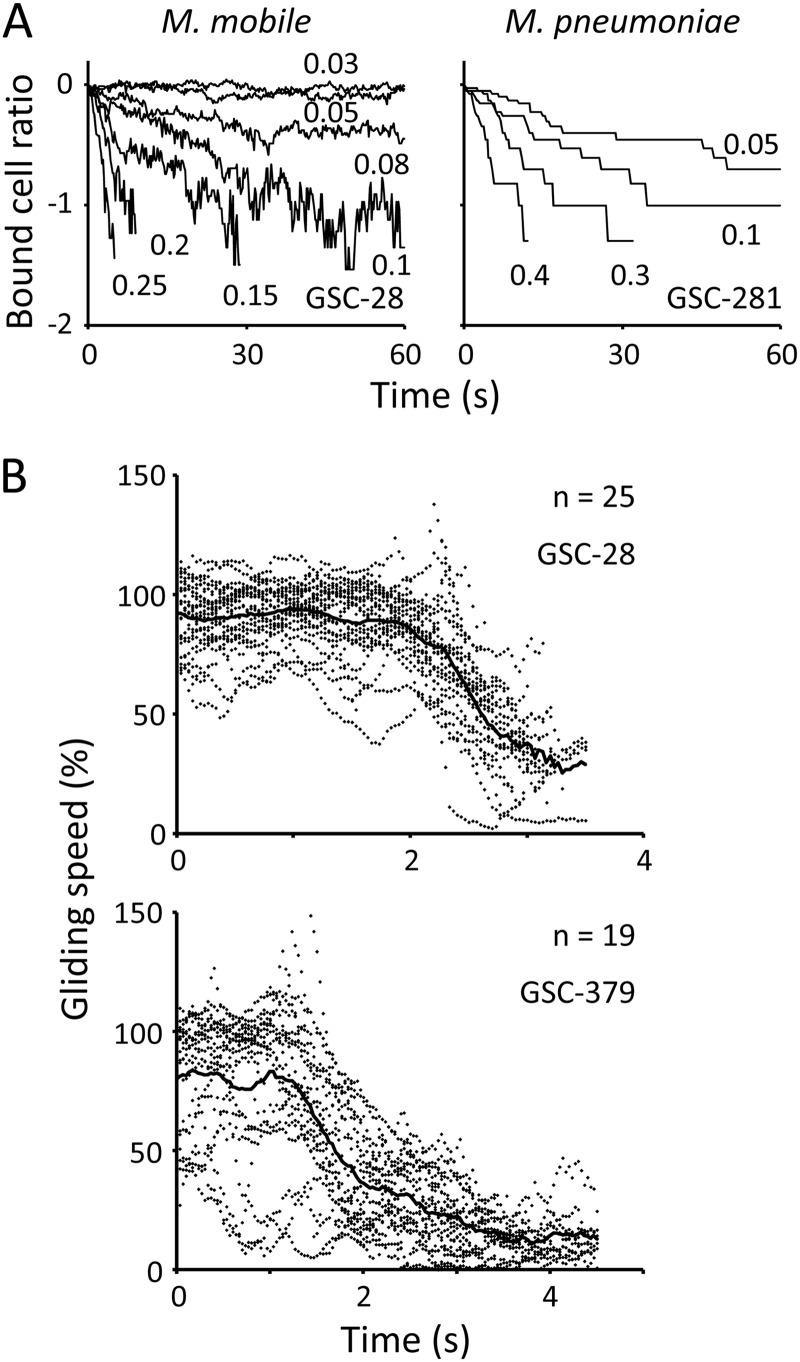

Next, we analyzed the effects of addition of sialylated compounds to gliding mycoplasmas that were already attached to the surface. The cell suspension was inserted into the tunnel chamber and incubated at room temperature. After 30 and 60 min, the sialylated oligosaccharide was added to gliding M. mobile and M. pneumoniae on glass, respectively, and the removal of gliding mycoplasmas was observed by phase-contrast microscopy (Fig. 4A; see Movies S2 and S3 in the supplemental material). The number of M. mobile cells on the glass, determined every 0.1 s, decreased exponentially with time following the first-order reaction kinetics, and the rate changed with the concentration of compound used. All cells were removed from the glass within 5 s after the addition of 0.25 mM GSC-28. The extent of inhibitory effects differed with the chemical structures of compounds, and the relative efficiency agreed with the affinities determined in Fig. 3 (Table 1). To analyze M. pneumoniae, 20 gliding cells were selected randomly, and their movements were traced. The number of bound cells decreased exponentially following first-order reaction kinetics. All cells were removed from the glass within 10 s after the addition of 0.4 mM GSC-281. The relative efficiency among the compounds was consistent with the results shown in Fig. 3 (Table 1).

Fig 4.

Removal of gliding mycoplasmas by sialylated compounds. (A) Results for the most effective compounds. The number of bound M. mobile cells is presented for every 0.2 s as a ratio to the number at time zero, which was approximately 80 cells. Twenty cells of gliding M. pneumoniae were selected randomly and observed for every second. The concentrations of compounds used are presented in the graphs in millimoles. The y axes are logarithmic. The rate was measured from the slope of the graph at the addition of 1.0 mM free sialylated compounds and is summarized in Table 1. (B) Change in M. mobile gliding speed after addition of sialylated compound. The gliding speeds of individual cells are shown as dots for every 0.03 s. The average gliding speed is shown by a solid line. Gliding speeds are presented as ratios to the speed without compounds, 2.6 and 3.3 μm/s for the graphs of GSC-28 and GSC-379, respectively.

Next, we analyzed the inhibition of M. mobile gliding in detail (see Movie S4 in the supplemental material). The gliding speeds of cells were analyzed after the addition of 0.01 mM GSC-28 and 0.5 mM GSC-379 (Fig. 4B). The gliding speeds were not changed significantly for about 2.0 s and 1.3 s by GSC-28 and GSC-379, respectively. However, the cells slowed down after those time points and reached 25.4% and 10.9% of the initial speeds at the time of detachment for GSC-28 and GSC-379, respectively. The decrease in gliding speed showed accelerating inhibition rather than first-order reaction kinetics.

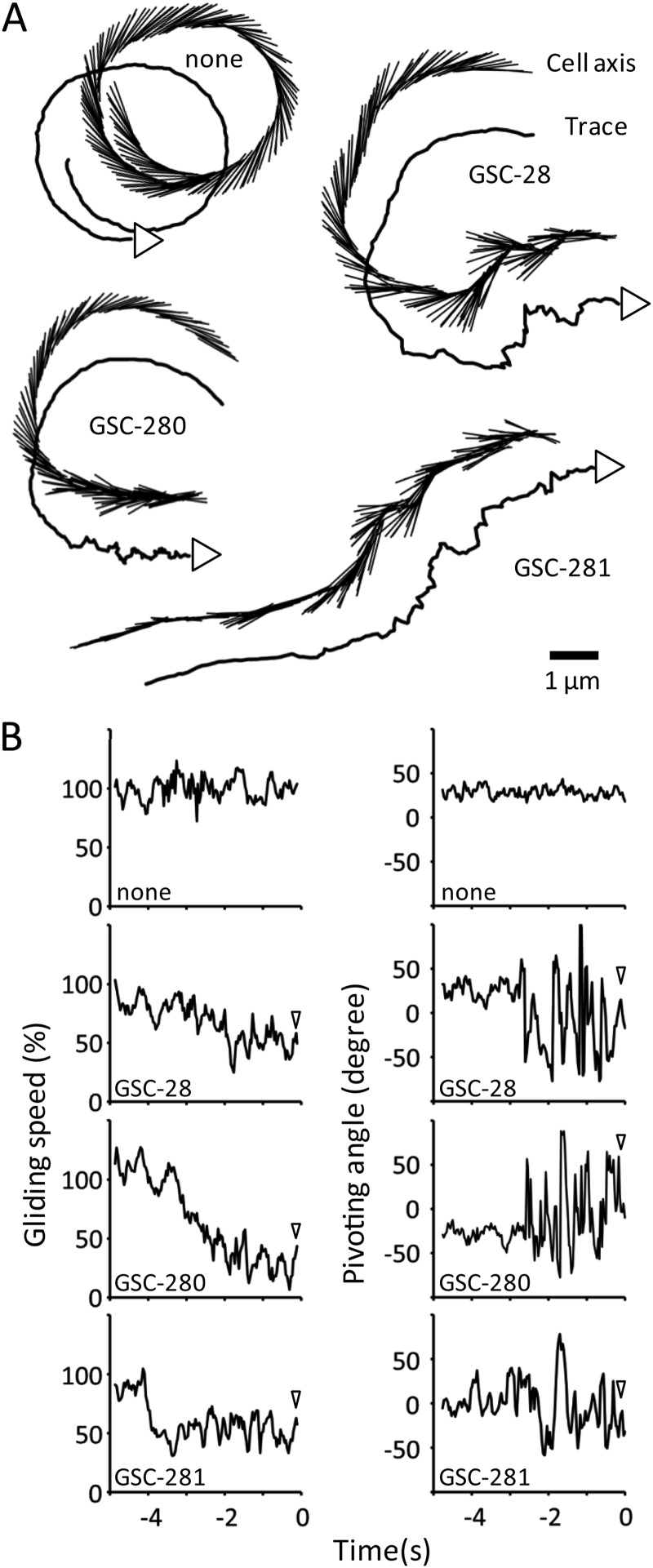

A previous study showed that M. mobile cells occasionally perform pivoting around the gliding machinery localized at the base of the membrane protrusion (37). In the present study, the cell pivoting before detachment was analyzed based on the difference between the cell axis and the preceding gliding direction over an observation period of 5 s (Fig. 5). The results showed that the frequency of cell pivoting increased 2 to 3 s before detachment for all compounds. Meanwhile, the gliding speed of each cell was substantially reduced to 50% to 80% of the initial gliding speed. The degree of pivoting or decrease in speed did not differ significantly among the compounds that could displace the gliding cells from the glass.

Fig 5.

Movement of M. mobile before detachment from the glass surface caused by sialylated compounds. (A) Cell axis and trace. The cell axis and the trace are shown for every 0.1 s from 5 s prior to detachment by the addition of the compounds indicated. In the trace marked “none,” the cell detached at the end by chance. The cells moved in the direction shown by the arrowhead attached to the trace. (B) Gliding speed and cell pivoting. The gliding speed and the pivoting angle of the cell are shown for every 0.1 s from 5 s prior to detachment. The same videos as in panel A were analyzed. The pivoting angle is the difference between the cell axis and the preceding gliding direction for 0.2 s. The gliding speed is presented as the ratio to the speed before the addition of sialylated compound. The arrowheads show the times of cell detachment.

DISCUSSION

Structures of sialylated compounds recognized by mycoplasmas.

A previous study reported that M. mobile and M. pneumoniae recognize sialyllactose and that the affinities are different between sialyllactoses with 2,3 and 2,6 linkages (27, 40, 41). However, the structures of the sialylated oligosaccharides recognized by mycoplasmas are still unclear. As sialic acids are negatively charged, two possibilities can be considered for recognition by mycoplasmas, i.e., the recognition may involve (i) the three-dimensional structures of sialic acid and neighboring sugar chains or (ii) the negative charge of the carboxyl group in the sialic acid. In the present study, we showed that the affinity between mycoplasmas and the sialylated oligosaccharides is sensitive to the differences in the structures of the sialylated oligosaccharides (Table 1) and concluded that the recognition of sialylated oligosaccharides by mycoplasmas proceeds in a “lock-and-key” fashion.

The most effective compound for M. mobile was Neu5Ac-α-2,6-galactose, which is well known as the target of human influenza virus (42). The most effective compound for M. pneumoniae was Neu5Ac-α-2,3-lactosamine, which is the target of avian influenza virus (43). This is consistent with the observed route of M. pneumoniae infection, in which M. pneumoniae binds to the lower part of the human trachea in the initial stage of infection because the structure Neu5Ac-α-2,3-lactosamine is localized there (44, 45).

As mycoplasma genomes do not have any homologs of chemotactic genes common in motile bacteria, mycoplasmas may not respond to chemoattractants, such as sugars or amino acids (10, 46). Actually, mycoplasma cells never reverse their direction of movement under microscopic observation, which is distinct from other motile bacteria (3, 47). The fact that mycoplasmas can detect the small structural difference in the sialylated oligosaccharide may suggest that mycoplasmas move to the proper environments by tracing the differences in sialylated oligosaccharides on the host tissues.

In the present study, we showed that the free sialylated oligosaccharides remove gliding M. pneumoniae cells from the glass with relative affinities similar to those for the inhibition of binding (Fig. 4 and Table 1). These results suggest that an adhesin molecule, probably P1 adhesin, acts as a foot in the gliding mechanism in the manner of Gli349 in M. mobile gliding, which is consistent with the finding that gliding can be inhibited by monoclonal antibodies (20, 26).

Cooperative binding of sialylated oligosaccharide.

In the present study, the concentration dependence of binding inhibition by all 9 of the effective compounds showed cooperativity (Fig. 2). There are two possible explanations for this cooperativity: (i) several sialylated oligosaccharides may be caught at the same time or (ii) the binding of a single sialylated oligosaccharide to a leg may increase the affinity of neighboring legs. The gliding speed was reduced with time by the addition of soluble sialylated oligosaccharides. The rate of decrease in gliding speed appeared to accelerate with time rather than following first-order reaction kinetics (Fig. 4B). These observations may suggest cooperativity in binding between the legs and the free sialylated oligosaccharides. Such time-dependent cooperativity could be explained by the second assumption suggested above. In the present study, we used the number of detached cells to evaluate the effects of free sialylated oligosaccharides. The detachment of a cell from glass is the integrated result of the binding inhibition of individual legs and may show cooperativity over time. However, the cooperativity observed in Fig. 4B was unlikely to have been caused by this scenario, because the decrease in the number of bound cells caused by free sialylated compounds followed the first-order reaction kinetics in Fig. 4A, showing that the detachment of cells occurs probabilistically, depending on the number of detached legs.

Drag force of legs after a stroke.

The maximum force generated by a mycoplasma cell was reported in a previous study to be 27 pN (12), which is about 1,800 times greater than the force calculated to be necessary for normal-speed gliding. Therefore, a decrease in the number of working legs cannot explain the decrease in gliding speed observed in the present study without additional assumptions. This apparent discrepancy can be explained by an assumption that the working legs generate drag force in a stage of the cycle for gliding (Fig. 6A). We have proposed a working model to explain the mechanism of M. mobile gliding wherein, after a stroke, the leg is removed from a sialylated compound fixed on a solid surface by the continuous movement of the cell caused by other legs (2, 3, 48). In the presence of a free sialylated compound, the decrease in the number of working legs causes a transient shortage of the propulsion force necessary to remove the legs after a stroke and results in the decrease in gliding speed.

Fig 6.

Schematic of the effects of sialylated compound on mycoplasma movements. (A) Reduction of gliding speed. (Top) Without free sialylated compounds. (Bottom) With free sialylated compounds. The white arrows show the force pulling the glass. The black arrows show the force required to remove the leg from the glass after a stroke. The dotted arrow shows the movement of the glass relative to the cell. The legs were removed from the glass surface after a stroke by the continuous movement of the cell. The number of working legs decreases when the legs catch the free sialylated compound, resulting in a decrease in the force needed to remove the legs after a stroke. (B) Cell pivoting after addition of free sialylated compounds. Shown is the lower side of a gliding M. mobile cell as viewed through the glass. The leg movements, cell pivoting, and gliding direction are indicated by small solid, dashed, and large solid arrows, respectively. (Left) Without free sialylated compounds. (Right) With free sialylated compounds. The number of working legs decreases when the legs catch the free sialylated compound. The decrease in propulsion force reduces the removal of legs after a stroke. The remaining legs form the center of the resulting pivot motion. The stroke timing of individual legs is unknown.

Previously, Nakane and Miyata reported that M. mobile cells exhibited pivoting by means of a propulsion force in gliding with a torque of up to more than 54.7 pN nm (37). In the present study, the frequency of pivoting was increased by the addition of sialylated oligosaccharides (Fig. 5). This could be explained by the effect of a drag force as follows (Fig. 6B). Mycoplasmas can glide in a straight line when there is sufficient propulsion force to allow the legs to be detached from the sialylated oligosaccharide after a stroke. However, when the propulsion force is insufficient, some of the legs do not detach, and the remaining legs form the center of the resulting pivot motion. It is unlikely that the free sialylated compounds removed the legs from the glass at random stages of the gliding cycle linked to ATP hydrolysis, because the binding of M. mobile cells starved and stopped on glass was not affected by the addition of free sialylated compounds (data not shown).

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research in Priority Areas “System Cell Engineering by Multi-Scale Manipulation,” “Innovative Nanoscience of Supermolecular Motor Proteins Working in Biomembrane,” and “Harmonized Supramolecular Motility Machinery and Its Diversity” (to M.M.); by a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (A) from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology of Japan (to M.M.); and by a grant from the Institution for Fermentation Osaka (to M.M.).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 2 November 2012

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/JB.01141-12.

REFERENCES

- 1. Razin S, Yogev D, Naot Y. 1998. Molecular biology and pathogenicity of mycoplasmas. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 62:1094–1156 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Miyata M. 2008. Centipede and inchworm models to explain Mycoplasma gliding. Trends Microbiol. 16:6–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Miyata M. 2010. Unique centipede mechanism of Mycoplasma gliding. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 64:519–537 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Miyata M, Ogaki H. 2006. Cytoskeleton of mollicutes. J. Mol. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 11:256–264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Jacobs E. 2012. Mycoplasma pneumoniae: now in the focus of clinicians and epidemiologists. Euro Surveill. 17:20084. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Pereyre S, Charron A, Hidalgo-Grass C, Touat A, Moses AE, Nir-Paz R, Bebear C. 2012. The spread of Mycoplasma pneumoniae is polyclonal in both an endemic setting in France and in an epidemic setting in Israel. PLoS One 7:e38585 doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0038585 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bredt W. 1979. Motility, p 141–145 In Barile MF, Razin S, Tully JG, Whitcomb RF. (ed), The Mycoplasmas, vol 1 Academic Press, New York, NY [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kirchhoff H. 1992. Motility, p 289–306 In Maniloff J, McElhaney RN, Finch LR, Baseman JB. (ed), Mycoplasmas—molecular biology and pathogenesis. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, DC [Google Scholar]

- 9. Krunkosky TM, Jordan JL, Chambers E, Krause DC. 2007. Mycoplasma pneumoniae host-pathogen studies in an air-liquid culture of differentiated human airway epithelial cells. Microb. Pathog. 42:98–103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Jaffe JD, Stange-Thomann N, Smith C, DeCaprio D, Fisher S, Butler J, Calvo S, Elkins T, FitzGerald MG, Hafez N, Kodira CD, Major J, Wang S, Wilkinson J, Nicol R, Nusbaum C, Birren B, Berg HC, Church GM. 2004. The complete genome and proteome of Mycoplasma mobile. Genome Res. 14:1447–1461 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hiratsuka Y, Miyata M, Tada T, Uyeda TQP. 2006. A microrotary motor powered by bacteria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 103:13618–13623 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Miyata M, Ryu WS, Berg HC. 2002. Force and velocity of Mycoplasma mobile gliding. J. Bacteriol. 184:1827–1831 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Miyata M, Uenoyama A. 2002. Movement on the cell surface of gliding bacterium, Mycoplasma mobile, is limited to its head-like structure. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 215:285–289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Miyata M, Yamamoto H, Shimizu T, Uenoyama A, Citti C, Rosengarten R. 2000. Gliding mutants of Mycoplasma mobile: relationships between motility and cell morphology, cell adhesion and microcolony formation. Microbiology 146:1311–1320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Rosengarten R, Kirchhoff H. 1987. Gliding motility of Mycoplasma sp. nov. strain 163K. J. Bacteriol. 169:1891–1898 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kusumoto A, Seto S, Jaffe JD, Miyata M. 2004. Cell surface differentiation of Mycoplasma mobile visualized by surface protein localization. Microbiology 150:4001–4008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Miyata M, Petersen J. 2004. Spike structure at interface between gliding Mycoplasma mobile cell and glass surface visualized by rapid-freeze and fracture electron microscopy. J. Bacteriol. 186:4382–4386 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Nakane D, Miyata M. 2007. Cytoskeletal “jellyfish” structure of Mycoplasma mobile. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 104:19518–19523 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Seto S, Uenoyama A, Miyata M. 2005. Identification of 521-kilodalton protein (Gli521) involved in force generation or force transmission for Mycoplasma mobile gliding. J. Bacteriol. 187:3502–3510 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Uenoyama A, Kusumoto A, Miyata M. 2004. Identification of a 349-kilodalton protein (Gli349) responsible for cytadherence and glass binding during gliding of Mycoplasma mobile. J. Bacteriol. 186:1537–1545 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Uenoyama A, Miyata M. 2005. Identification of a 123-kilodalton protein (Gli123) involved in machinery for gliding motility of Mycoplasma mobile. J. Bacteriol. 187:5578–5584 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Jaffe JD, Miyata M, Berg HC. 2004. Energetics of gliding motility in Mycoplasma mobile. J. Bacteriol. 186:4254–4261 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ohtani N, Miyata M. 2007. Identification of a novel nucleoside triphosphatase from Mycoplasma mobile: a prime candidate for motor of gliding motility. Biochem. J. 403:71–77 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Uenoyama A, Miyata M. 2005. Gliding ghosts of Mycoplasma mobile. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 102:12754–12758 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Nakane D, Adan-Kubo J, Kenri T, Miyata M. 2011. Isolation and characterization of P1 adhesin, a leg protein of the gliding bacterium Mycoplasma pneumoniae. J. Bacteriol. 193:715–722 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Seto S, Kenri T, Tomiyama T, Miyata M. 2005. Involvement of P1 adhesin in gliding motility of Mycoplasma pneumoniae as revealed by the inhibitory effects of antibody under optimized gliding conditions. J. Bacteriol. 187:1875–1877 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Nagai R, Miyata M. 2006. Gliding motility of Mycoplasma mobile can occur by repeated binding to N-acetylneuraminyllactose (sialyllactose) fixed on solid surfaces. J. Bacteriol. 188:6469–6475 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Uenoyama A, Seto S, Nakane D, Miyata M. 2009. Regions on Gli349 and Gli521 protein molecules directly involved in movements of Mycoplasma mobile gliding machinery suggested by inhibitory antibodies and mutants. J. Bacteriol. 191:1982–1985 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Lipman RP, Clyde WA, Jr, Denny FW. 1969. Characteristics of virulent, attenuated, and avirulent Mycoplasma pneumoniae strains. J. Bacteriol. 100:1037–1043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Ando H, Koike Y, Koizumi S, Ishida H, Kiso M. 2005. 1,5-Lactamized sialyl acceptors for various disialoside syntheses: novel method for the synthesis of glycan portions of Hp-s6 and HLG-2 gangliosides. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 44:6759–6763 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Fukunaga K, Ikami N, Ishida H, Kiso M. 2002. Synthesis of sialyl-α-(2–3)-neolactotetraose derivatives modified at C-2 of the N-acetylglucosamine residue: probes for investigation of acceptor specificity of human α-1,3-fucosyltransferases, FUC-TVII, and FUC-TVI. J. Carbohydr. Chem. 21:385–409 [Google Scholar]

- 32. Hasegawa A, Uchimura A, Ishida H, Kiso M. 1995. Synthesis of a sialyl Lewis X ganglioside analogue containing N-glycolyl in place of the N-acetyl group in the N-acetylneuraminic acid residue. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 59:1091–1094 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Kameyama A, Ishida H, Kiso M, Hasegawa A. 1991. Total synthesis of tumor-associated ganglioside, sialyl Lewis X. J. Carbohydr. Chem. 10:549–560 [Google Scholar]

- 34. Murase T, Kameyama A, Kartha KPR, Ishida H, Kiso M, Hasegawa A. 1989. A facile, regio and stereoselective synthesis of ganglioside GM4 and its position isomer. J. Carbohydr. Chem. 8:265–283 [Google Scholar]

- 35. Tanahashi E, Fukunaga K, Ozawa Y, Toyoda T, Ishida H, Kiso M. 2000. Synthesis of sialyl-α-(2–3)-neolactotetraose derivatives containing different sialic acids: molecular probes for elucidation of substrate specificity of human α1,3-fucosyltransferases. J. Carbohydr. Chem. 19:747–768 [Google Scholar]

- 36. Terada T, Ishida H, Kiso M, Hasegawa A. 1995. Synthesis of KDN-α-(2–6)-lactotetraosylceramide and KDN-α-(2–6)-neolactotetraosylceramide. J. Carbohydr. Chem. 14:751–768 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Nakane D, Miyata M. 2012. Mycoplasma mobile cells elongated by detergent and their pivoting movements in gliding. J. Bacteriol. 194:122–130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Kenri T, Seto S, Horino A, Sasaki Y, Sasaki T, Miyata M. 2004. Use of fluorescent-protein tagging to determine the subcellular localization of Mycoplasma pneumoniae proteins encoded by the cytadherence regulatory locus. J. Bacteriol. 186:6944–6955 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Nakane D, Miyata M. 2009. Cytoskeletal asymmetrical dumbbell structure of a gliding mycoplasma, Mycoplasma gallisepticum, revealed by negative-staining electron microscopy. J. Bacteriol. 191:3256–3264 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Krivan HC, Olson LD, Barile MF, Ginsburg V, Roberts DD. 1989. Adhesion of Mycoplasma pneumoniae to sulfated glycolipids and inhibition by dextran sulfate. J. Biol. Chem. 264:9283–9288 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Loomes LM, Uemura K, Childs RA, Paulson JC, Rogers GN, Scudder PR, Michalski JC, Hounsell EF, Taylor-Robinson D, Feizi T. 1984. Erythrocyte receptors for Mycoplasma pneumoniae are sialylated oligosaccharides of Ii antigen type. Nature 307:560–563 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Viswanathan K, Chandrasekaran A, Srinivasan A, Raman R, Sasisekharan V, Sasisekharan R. 2010. Glycans as receptors for influenza pathogenesis. Glycoconj. J. 27:561–570 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Garcia-Sastre A. 2010. Influenza virus receptor specificity: disease and transmission. Am. J. Pathol. 176:1584–1585 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Loveless RW, Griffiths S, Fryer PR, Blauth C, Feizi T. 1992. Immunoelectron microscopic studies reveal differences in distribution of sialo-oligosaccharide receptors for Mycoplasma pneumoniae on the epithelium of human and hamster bronchi. Infect. Immun. 60:4015–4023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Shinya K, Ebina M, Yamada S, Ono M, Kasai N, Kawaoka Y. 2006. Avian flu: influenza virus receptors in the human airway. Nature 440:435–436 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Himmelreich R, Hilbert H, Plagens H, Pirkl E, Li BC, Herrmann R. 1996. Complete sequence analysis of the genome of the bacterium Mycoplasma pneumoniae. Nucleic Acids Res. 24:4420–4449 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Porter SL, Wadhams GH, Armitage JP. 2011. Signal processing in complex chemotaxis pathways. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 9:153–165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Chen J, Neu J, Miyata M, Oster G. 2009. Motor-substrate interactions in mycoplasma motility explains non-Arrhenius temperature dependence. Biophys. J. 97:2930–2938 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.