Abstract

Phosphatidylcholine (PC), a common phospholipid of the eukaryotic cell membrane, is present in the cell envelope of the intracellular pathogen Brucella abortus, the etiological agent of bovine brucellosis. In this pathogen, the biosynthesis of PC proceeds mainly through the phosphatidylcholine synthase pathway; hence, it relies on the presence of choline in the milieu. These observations imply that B. abortus encodes an as-yet-unknown choline uptake system. Taking advantage of the requirement of choline uptake for PC synthesis, we devised a method that allowed us to identify a homologue of ChoX, the high-affinity periplasmic binding protein of the ABC transporter ChoXWV. Disruption of the choX gene completely abrogated PC synthesis at low choline concentrations in the medium, thus indicating that it is a high-affinity transporter needed for PC synthesis via the PC synthase (PCS) pathway. However, the synthesis of PC was restored when the mutant was incubated in media with higher choline concentrations, suggesting the presence of an alternative low-affinity choline uptake activity. By means of a fluorescence-based equilibrium-binding assay and using the kinetics of radiolabeled choline uptake, we show that ChoX binds choline with an extremely high affinity, and we also demonstrate that its activity is inhibited by increasing choline concentrations. Cell infection assays indicate that ChoX activity is required during the first phase of B. abortus intracellular traffic, suggesting that choline concentrations in the early and intermediate Brucella-containing vacuoles are limited. Altogether, these results suggest that choline transport and PC synthesis are strictly regulated in B. abortus.

INTRODUCTION

Choline is a methylated nitrogen compound that is widespread in nature. It is a precursor of several metabolites that perform numerous biological functions (1, 2), and it is predominantly used for the synthesis of essential lipid components of cell membranes (3). Quantitatively, phosphatidylcholine (PC) is the most important metabolite of choline and accounts for approximately one-half of the total membrane lipid content in eukaryotes (4). In contrast, prokaryotes most often contain membranes that are rich in phosphatidylethanolamine (PE), while PC is present in only about 10% of all known bacterial species, particularly in those that interact with eukaryotes (5, 6). Recently, several studies have started to elucidate the importance of PC in pathogenic microbe-host interactions (7–11).

Like other members of the Rhizobiaceae family, Brucella abortus, the etiological agent of brucellosis, contains PC as one of its major membrane components (8, 9, 12). Brucellosis is a worldwide zoonosis affecting both wild and domestic mammals, as well as humans (13, 14). These bacteria are facultative intracellular parasites capable of invading and proliferating intracellularly in professional and nonprofessional phagocytes, thus establishing long-lasting infections. Brucella spp. are some of the best examples of pathogens that are able to hide from the host's immune system by subverting the macrophage bactericidal defensive mechanism and creating a membrane-bound compartment that supports its intracellular replication (15). It has been postulated that most of these properties are related to the singular structure and composition of the Brucella cell envelope (CE), which is characterized by the presence of a lipopolysaccharide (LPS) with low endotoxic activities, porins, and outer membrane proteins (OMPs) that are covalently bound to the peptidoglycan layer and by the presence of PC as one of the main phospholipids (16).

In bacteria, PC is synthesized through two alternative biosynthetic pathways: (i) the phosphatidylcholine synthase (PCS) pathway, in which choline is directly condensed with cytidine diphosphate-diacylglycerol (CDP-DAG) by the PCS enzyme (17), and (ii) the methylation pathway, also known as the Kennedy pathway, which consists of three methylation steps of PE catalyzed by the enzyme phospholipid N-methyltransferase (PmtA), which uses S-adenosylmethionine (SAM) as the methyl donor (6, 17–21). The PCS pathway depends on the presence of choline for PC biosynthesis, while the methylation pathway is choline independent, since PC is synthesized from PE.

In B. abortus, PC synthesis is almost exclusively dependent on the PCS pathway. The gene coding for PmtA has accumulated several amino acid substitutions that may explain the minimal PmtA activity observed in this bacterium (8, 9).

Since there is no evidence that B. abortus can synthesize choline de novo, and because choline uptake from exogenous sources is energetically more favorable than is de novo synthesis, the PCS pathway might rely on exogenously provided choline. To achieve this goal, bacteria have evolved different uptake mechanisms for choline transport across the bacterial membrane. Most often, the binding protein-dependent ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporters have been described as fulfilling this role (7, 22–24). However, a corresponding choline transporter(s) in Brucella has not been described so far.

In this work, we identified three putative ABC-type transporters of quaternary amines and analyzed their abilities to transport choline. One of these putative transporters is highly similar to the well-characterized choline-specific ABC transport system ChoXWV of Sinorhizobium meliloti (25, 26). The open reading frame (ORF) BAB1_1593 was identified as a B. abortus homologue of ChoX, the high-affinity periplasmic binding protein of the ChoXWV system. Here, we describe for the first time a high-affinity choline transport system in B. abortus that is required for PC synthesis under specific growth conditions.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, media, and growth conditions.

The bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are listed with their relevant characteristics in Table S1 in the supplemental material. B. abortus strains were grown at 37°C on tryptic soy broth (TSB), tryptic soy agar (TSA) (Becton, Dickinson, and Co.), or Gerhardt-Wilson (GW) minimum medium (27). The media were supplemented with 1, 10, or 100 μM choline chloride (Sigma-Aldrich Co.) where indicated. When required, antibiotics were added at 5 μg ml−1 (nalidixic acid), 5 μg ml−1 (gentamicin [Gm]), or 50 μg ml−1 (ampicillin [Ap]). Escherichia coli strains were grown at 37°C in Luria-Bertani (LB) broth supplemented with 50 μg ml−1 kanamycin (Km) and 100 μg ml−1 Ap when appropriate.

Thin-layer chromatography lipid analysis.

Log-phase bacteria were used to inoculate fresh media at an initial optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.1. Each culture was supplemented with either 0.88 μM sodium [14C]acetate ([14C]AcONa) (56.50 mCi/mmol) (New England Nuclear) or 0.4 μM [methyl-14C]choline chloride (50 mCi/mmol) (New England Nuclear), and the bacteria were grown for 48 h to reach an OD600 of ∼0.8 to 0.9 (three duplication rounds) to allow for radioactive molecule incorporation. Cells were harvested by centrifugation and lipids were extracted according to the method of Bligh and Dyer (28). Total lipid extracts were separated on silica gel plates (Kieselgel 60; Merck) by using chloroform-methanol-water (14:6:1 [vol/vol/vol]) as a running solvent. The radioactive lipid profile was analyzed after 7 days of plate exposure to Kodak BioMax film at −80°C.

Choline uptake assay.

For radioactive choline uptake analyses, cultures of wild-type B. abortus, the B. abortus ΔchoX mutant, the B. abortus pcs mutant, or the complemented B. abortus ΔchoX pDK51-choX strain were grown in GW minimal medium with or without 10 or 100 μΜ cold choline chloride. Cells were washed three times with ice-chilled GW medium and adjusted to an OD600 of 0.5 with GW medium. The reaction mixtures were initiated by the addition of [3H]choline chloride (80.6 Ci/mmol) (New England Nuclear) to a final concentration of 3.3 μM and incubated at 37°C, and aliquots were taken at different time points (0 to 90 min). Samples were immediately chilled on ice, washed five times with ice-chilled GW medium, and centrifuged, and cell pellets were resuspended in 500 μl of scintillation liquid. The radioactivities of the cell pellets were determined with a scintillation spectrometer (Wallac 1414 controlled by WinSpectral). To assess uptake kinetics at different choline concentrations, the bacteria were incubated for 7 min at 37°C in GW medium with a mix of [3H]choline-cold choline (1:100 [vol/vol]) ranging from 6.25 × 10−2 μM to 64 μM, and the incorporated radioactivities in the cell pellets were determined as described above.

Data bank searches and sequence alignments.

The domain search tool of the Protein Families Database (http://pfam.sanger.ac.uk) (29) was used to identify B. abortus strain 2308 proteins containing high identity percentages to the substrate-binding domain of the ABC-type glycine-betaine transport system OpuAC (PF04069).

Protein homologues of B. abortus 2308 ChoX were searched via the Web server of the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI BLAST) (30). The sequence alignments of ChoX homologues were performed using Web-based ClustalW2 (31) from the European Bioinformatics Institute (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/msa/clustalw2).

Cloning, generation of mutants, and complemented strains.

Unmarked deletion mutants of the selected candidate genes (see Table S1 in the supplemental material) were generated as follows: DNA fragments (∼500 bp) containing the flanking regions of BAB1_1593, BAB1_0226, and BAB2_0502 were amplified from B. abortus 2308 genomic DNA with modified primers carrying BamHI and SphI restriction sites in the 5′ and 3′ ends, respectively. The PCR amplicons were ligated to the BamHI and SphI sites of the mobilizable suicide vector pK18mobsacB (32); the resulting plasmid was transformed in Escherichia coli S17λ-pir and subsequently conjugated to B. abortus 2308. Single recombinants were selected with kanamycin and replica plated in TSA supplemented with 10% sucrose to counterselect the double recombinants. Deletion of the selected gene was confirmed by colony PCR and sequence analysis. Using these procedures, the mutant strains B. abortus ΔchoX, B. abortus Δ2_0502, and B. abortus Δ1_0226 were generated. To obtain the double mutant strain, B. abortus Δ2_0502 and B. abortus Δ1_0226 were conjugated with E. coli S17λ-pir carrying pK18mobsacB-choX. The exconjugants were selected with kanamycin and plated on 10% sucrose in order to select the clean deletion of the choX gene.

To construct the pDK51-choX complementing plasmid, the amplicon containing the choX gene under its own promoter was ligated to the pDK51 vector (33), a pBBRMCS-4 derivative lacking the lac promoter. The plasmid was transferred by biparental conjugation to the B. abortus ΔchoX mutant, and the resulting complemented strain was selected with ampicillin.

Protein expression and purification.

E. coli BL21-CodonPlus cells carrying the expression plasmid pET28a(+)-choX were grown in 250 ml of M9 minimal medium with 0.2% glucose as a carbon source and chloramphenicol (20 μg ml−1) on a rotary shaker (250 rpm) at 37°C. Protein expression was induced by the addition of isopropyl 1-thio-β-d-galactopyranoside (final concentration, 1 mM), performed when the culture reached an OD600 of 0.7. After induction, the bacterial culture was incubated for 6 additional hours, and the cells were harvested by centrifugation (6,000 × g, 15 min, 4°C). The cell pellet was resuspended in lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.6], 150 mM NaCl, 1.5% Triton X-100, 0.5 mg ml−1 lysozyme, and protease inhibitor cocktail) and subjected to 5 sonication pulses of 1 min each. Insoluble material was removed by centrifugation (6,000 × g, 15 min) and subsequent filtration with a 0.45-μm filter. Soluble fractions were applied to a nickel-Sepharose (GE Healthcare) column for affinity purification of the His-tagged ChoX. Buffer A (500 mM NaCl, 50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.6]) was used for washing the column, and buffer B (500 mM NaCl, 50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.6], 500 mM imidazole) was used for the elution of nonspecific protein binding at two low-concentration steps of 8% and 12% (40 mM and 60 mM imidazole, respectively). Recombinant ChoX was eluted from the affinity matrix by using an imidazole gradient from 60 mM to 500 mM (at a flow rate of 1 ml/min). ChoX elution was observed at ∼150 mM imidazole. To exchange the buffer of the eluted ChoX-containing fractions, the protein was dialyzed (24 h at 4°C) against 3 liters of substrate-binding buffer for an intrinsic tryptophan fluorescence-based assay. Protein purity was assessed and quantification was performed by Coomassie blue staining of SDS-polyacrylamide gel (10%) and Bradford protein assays, respectively.

Size exclusion chromatography.

Size exclusion chromatography was performed using a Superdex 75 10/30 column run with 50 mM NaCl, 10 mM phosphate, and 2.7 mM KCl (pH 7.4) at a flow rate of 0.5 ml/min. The column was calibrated with the globular proteins aldolase (158 kDa), ovalbumin (43 kDa), myoglobin (17.6 kDa), and vitamin B12 (1.355 kDa) to obtain an R2 value of 0.9977 for the calibration curve. A 250-μl aliquot of purified ChoX (preincubated with or without a saturating concentration of choline) at a concentration of 0.5 mg ml−1 was injected, and the elution volume (VE) was determined. Using the calibration curve and the VE, the ChoX size was calculated and the presence of monomers and/or homopolymers was evaluated.

Fluorescence-based ligand-binding assays.

Intrinsic tryptophan fluorescence was used to determine the binding affinity of ChoX for the different ligands (26). The excitation wavelength was set to 295 nm, fluorescence emissions were monitored from 305 nm to 400 nm (slit widths of 5 nm) at 25°C in 3-mm cells, and background fluorescence (buffer without protein) was subtracted from all protein-substrate-binding measurements. Different amounts (340 nM for choline and 1 μM for betaine, l-proline, and l-carnitine) of 100 mM ligand stock solution (comprising 50 mM NaCl, 10 mM phosphate, 2.7 mM KCl [pH 7.4]) were added to purified ChoX in the same buffer solution. The KD (ligand dissociation constant) for each ChoX-substrate complex was obtained by fitting a single-binding-site model to the measured fluorescence intensity at a fixed wavelength at different ligand concentrations. The wavelengths used were 340 nm for betaine and 317 nm for the other ligands. The binding affinity of ChoX for choline was averaged from three independent measurements.

Cell culture infection.

J774.A1 macrophage-like cell lines were maintained in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, streptomycin (50 μg ml−1), and penicillin (50 U ml−1) in a 5% CO2 atmosphere at 37°C (all solutions and media were purchased from Gibco). Cells (5 × 104 per well) were seeded on 24-well plates without antibiotics and were incubated under these conditions for 24 h. B. abortus infections were carried out with bacteria grown in GW medium without choline or in TSB (with choline excess) at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 50:1. The plates were centrifuged for 10 min at 300 × g to promote bacterium-cell contact and were kept 30 min at 37°C to allow for bacterial internalization. The wells were washed three times with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and fresh RPMI medium with 50 μg ml−1 gentamicin, and 100 μg ml−1 streptomycin was added to kill noninternalized bacteria. At the indicated times, the cells were washed three times with PBS and lysed with 500 μl of 0.1% Triton X-100 (Sigma-Aldrich). The number of intracellular CFU was determined by plating serial dilutions on TSA with the appropriate antibiotic.

Infection of mice.

Eight-week-old female BALB/c mice were inoculated orally with 1 × 1010 CFU of B. abortus strains resuspended in PBS. At the indicated time postinoculation (p.i.), spleens from the infected mice were removed and homogenized in 2 ml of PBS. Serial dilutions from individualized organs were plated on TSA to quantify the recovered CFU.

RESULTS

PC synthesis in B. abortus occurs mainly through the PCS pathway.

To confirm our previous observations that B. abortus depends on exogenous choline for PC synthesis, the lipid profiles of B. abortus 2308 and the corresponding B. abortus pcs mutant were analyzed by thin-layer chromatography (TLC) after in vivo labeling with [14C]choline or [14C]AcONa as described in Materials and Methods.

The spots corresponding to PC, PE, ornithine lipid (OL), cardiolipin (CL), and phosphatidylglycerol (PG) were observed in B. abortus 2308 labeled with [14C]AcONa (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). When [14C]choline was used, only a major spot corresponding to PC was detected clearly (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). As expected, we were unable to detect PC synthesis in the B. abortus pcs mutant labeled with [14C]choline; only a faint spot, probably corresponding to PC, was observed when the mutant was labeled with [14C]AcONa, confirming our previous findings that, at least under the conditions assayed, PC biosynthesis occurs mainly through the choline-dependent PCS pathway (8).

These observations imply that a functional choline uptake system must be present in B. abortus and that PC synthesis could be a useful and indicative method for identifying the putative choline transporter(s).

Choline uptake in B. abortus.

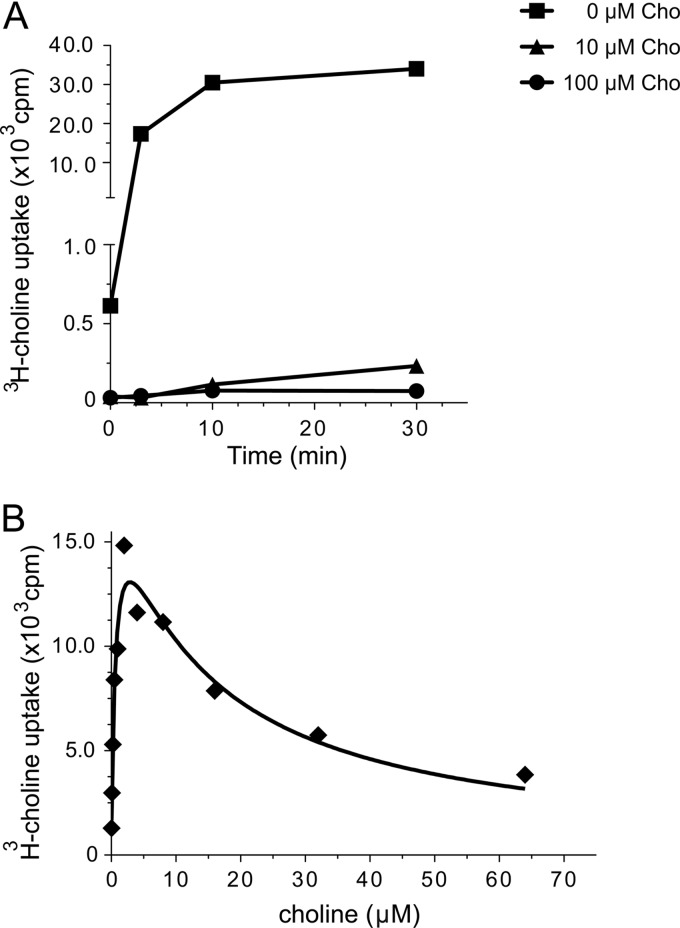

To characterize choline transport in B. abortus, the kinetics of radiolabeled choline uptake was assayed. For this purpose, B. abortus 2308 pregrown in GW medium with or without the addition of choline was incubated with 3.3 μM [3H]choline, and at the indicated time points, choline uptake was scored as indicated in Materials and Methods.

When cells were pregrown in GW medium without choline, radiolabeled choline incorporation rapidly increased during the first 10 min of incubation, and thereafter, the metabolite uptake reached a plateau. Notably, when bacteria were pregrown in GW medium with 10 μM or 100 μM choline, radiolabeled choline uptake was reduced 250- and 400-fold, respectively, indicating that the addition of choline to the growth medium resulted in uptake inhibition (Fig. 1A). To confirm the observed inhibitory role of choline in its own transport, the uptake was assessed at different choline concentrations. As shown in Fig. 1B, choline uptake reached maximum incorporation at 2 μM choline, but at higher concentrations, there was a significant level of substrate inhibition. From these results, we conclude that B. abortus encodes a high-affinity choline transport system whose activity seems to be tightly regulated.

Fig 1.

B. abortus choline uptake kinetics. (A) Samples containing 5 × 108 B. abortus 2308 cells pregrown in GW medium supplemented with 0, 10, or 100 μM cold choline chloride (Cho) were incubated in the presence of [3H]choline. At the indicated times, the samples were pelleted and washed, and the incorporated radioactivities were measured as indicated in Materials and Methods. (B) Samples of B. abortus 2308 (2.5 × 108 cells) grown in GW medium without choline chloride were incubated for 7 min in the presence of increasing concentrations of [3H]choline-cold choline (1:100 [vol/vol]), and the incorporated radioactivities were measured as indicated in Materials and Methods. Each graphic shows a representative of three experiments.

Identification of candidate choline-binding proteins in Brucella abortus.

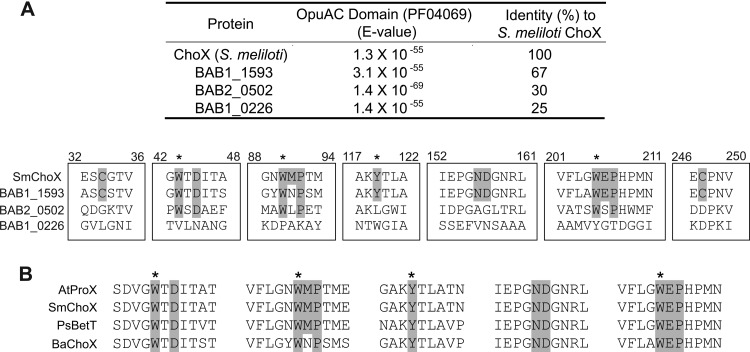

To examine the potential choline transporters in B. abortus, we searched the B. abortus 2308 genome for proteins with domains that were involved in quaternary ammonium compound transport. We found three ORFs, BAB1_0226, BAB1_1593, and BAB2_0502, which share high similarity with the OpuAC protein families (Pfam) domain implicated in glycine-betaine, l-carnitine, l-proline, histidine, and choline transport in closely related species (Fig. 2A). These ORFs showed low levels of identity to the S. meliloti high-affinity choline-binding protein ChoX; BAB1_1593 was the candidate with the highest identity level (67%) (Fig. 2B). Alignment analysis revealed that BAB1_1593 contains all the relevant amino acids required for choline binding in the S. meliloti homologue, whereas BAB1_0226 and BAB2_0502 harbor several substitutions at critical positions (in particular, W43, W90, Y119, and W205) for the binding activity of the S. meliloti ChoX protein (Fig. 2A). In the genomic context, we found an ATPase and an inner membrane protein flanking each candidate gene (see Fig. S6 in the supplemental material). These genes and their genomic organization correspond to those of an ABC transport system. From this analysis, we infer that BAB1_0226, BAB1_1593, and BAB2_0502 are the substrate-binding components of ABC transporters that could be involved in choline uptake in B. abortus.

Fig 2.

Analysis of choline-binding protein candidates. (A) Comparison of B. abortus proteins containing an OpuAC domain. The E values are used to indicate the significance of the OpuAC prediction for each protein. The second column shows the percentage of identity between B. abortus OpuAC proteins and the S. meliloti high-affinity choline-binding protein, ChoX. The relevant amino acids for the overall fold of S. meliloti ChoX are highlighted, including those that participate in one disulfide bridge (Cys33 to Cys247) and two cis-peptide bonds (Met91-Pro92 and Glu206-Pro207). Aromatic residues which are key determinants of the binding pocket (Trp43, Trp90, Tyr119, and Trp205) are indicated by asterisks above the sequences. (B) Comparison of the amino acid sequences of the B. abortus choX (BaChoX) and the proline-glycine-betaine substrate-binding protein of A. tumefaciens (AtProX) (AT5A_08575), ChoX of S. meliloti (SmChoX) (SMc02737), and BetT of Pseudomonas syringae (PsBetT) (PSPTO_5269).

The BAB1_1593 protein is required for choline-dependent PC synthesis.

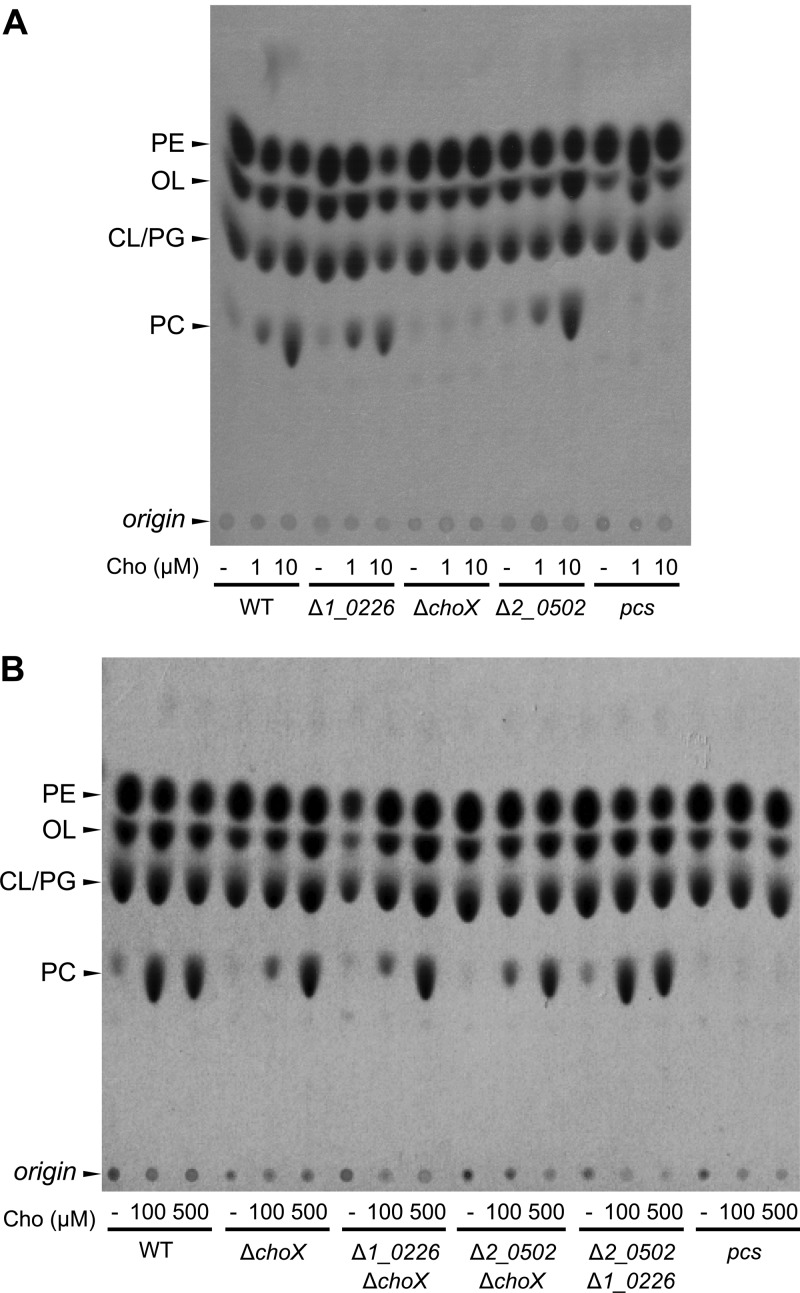

In order to identify the transporter(s) involved in choline uptake, unmarked deletion mutants on the three putative substrate-binding proteins (hereafter named B. abortus Δ1_0226, B. abortus ΔchoX, and B. abortus Δ2_0502) were generated, and PC synthesis from exogenous choline was used as the read-through method. The mutants and the wild-type strain were grown for 24 h in choline-depleted medium and then transferred to GW medium supplemented with increasing choline concentrations (0, 1 μM, and 10 μM) and [14C]AcONa, as described in Materials and Methods.

As shown in Fig. 3A, B. abortus Δ1_0226 and B. abortus Δ2_0502 were capable of synthesizing PC amounts comparable to those observed with the wild-type strain. As expected, the intensity of the PC spot increased with increasing choline concentrations in the culture medium. However, the B. abortus ΔchoX mutant and the negative control strain B. abortus pcs were both unable to synthesize PC at the substrate concentrations analyzed.

Fig 3.

PC synthesis is defective in the B. abortus ΔchoX mutant. (A) Lipid profile of mutants at low choline concentrations. The bacteria were grown in GW medium with sodium [14C]acetate supplemented with 0, 1, or 10 μM choline (Cho), and total lipid extracts were analyzed by monodimensional TLC. (B) Lipid profile of mutants at high choline concentrations. The bacteria were grown in GW medium with sodium [14C]acetate supplemented with 0, 100, or 500 μM Cho and processed as described above. WT, wild-type B. abortus 2308; Δ1_0226, ΔchoX, and Δ2_0502, B. abortus single-deletion mutants carrying a deletion in the gene BAB1_0226, BAB1_1593, or BAB2_0502, respectively; Δ1_0226 ΔchoX, Δ2_0502 ΔchoX, and Δ1_0226 Δ2_0502, B. abortus double-deletion mutants with mutations in the same genes mentioned above; pcs, B. abortus pcs mutant; PE, phosphatidylethanolamine; PC, phosphatidylcholine; CL, cardiolipin; PG, phosphatidylglycerol; OL, ornithine lipid.

These results indicate that at low micromolar choline concentrations, PC synthesis requires a functional BAB1_1593 gene, suggesting that this substrate-binding protein is necessary for choline uptake in Brucella spp.

To assess whether BAB1_0226 and BAB2_0502 play any role in PC synthesis that could be masked by BAB1_1593 activity at higher choline concentrations, the double mutant strains B. abortus Δ1_0226 ΔchoX, B. abortus Δ2_0502 ΔchoX, and B. abortus Δ2_0502 Δ1_0226 were generated, and PC synthesis was evaluated at high choline concentrations (0 μM, 100 μM, and 500 μM). As can be observed in the lipid profile in Fig. 3B, at 500 μM choline, all strains synthesized PC amounts comparable to that of the parental strain, suggesting the presence of secondary low-affinity choline transport activity. However, in the presence of 100 μM choline, only the B. abortus Δ2_0502 Δ1_0226 mutant, which has a functional BAB1_1593 gene, was capable of synthesizing wild-type PC amounts. Single and double mutants with a choX deletion displayed a significant reduction of PC levels. From these experiments, we conclude that ChoX is the only high-affinity choline-binding protein necessary for PC synthesis at low micromolar choline concentrations.

Choline uptake is severely impaired in the B. abortus ΔchoX mutant.

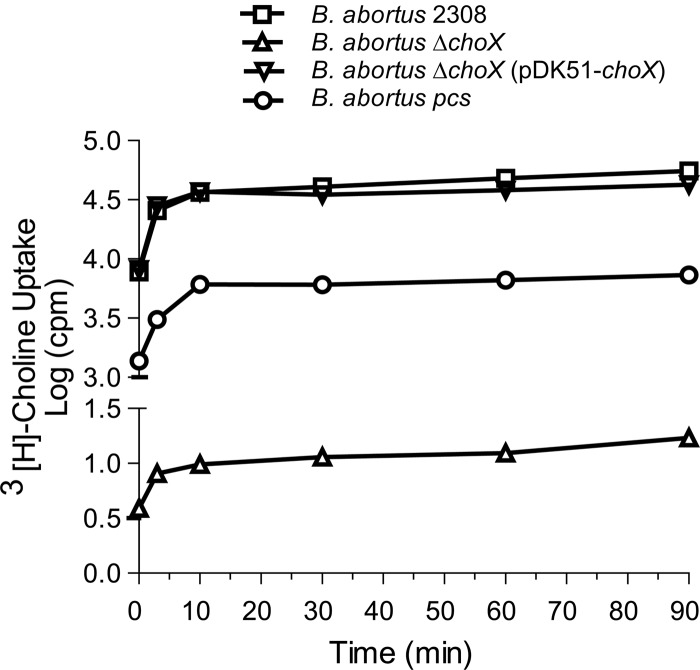

In order to confirm that ChoX is necessary for choline transport, we analyzed the kinetics of radiolabeled choline uptake in B. abortus 2308, B. abortus ΔchoX, B. abortus ΔchoX (pDK51-choX), and B. abortus pcs.

Deletion of the choX gene severely impaired choline uptake by 3 orders of magnitude at all of the evaluated times relative to the uptake of the wild-type strain (Fig. 4). The choline uptake deficiency of B. abortus ΔchoX completely reverted to wild-type levels through ectopic expression of choX in the pDK51 vector. Interestingly, B. abortus pcs showed an 85% reduction in choline incorporation levels compared to that of the wild-type strain, although choX is not affected in this mutant. This result suggests that the above-mentioned regulation of choline uptake might be related to PC biosynthesis, but the underlying mechanism remains to be determined.

Fig 4.

Choline uptake is severely impaired in B. abortus ΔchoX. The amounts of radiolabeled choline incorporated by B. abortus 2308, the B. abortus ΔchoX mutant, the B. abortus ΔchoX (pDK51-choX) complemented strain, and the B. abortus pcs mutant are shown. The strains were incubated at 37°C with [3H]choline (0.1 μCi/reaction) for the indicated times. The curves indicate the mean values from two independent experiments. The standard error bars are smaller than the symbols.

Taken together, our data demonstrate that ChoX is directly involved in choline uptake and suggest that it is a tightly regulated process affected by the exogenous choline concentration and the synthesis of PC.

B. abortus ChoX is a high-affinity choline-binding protein.

N-terminally His6-tagged ChoX was produced in E. coli BL21 and purified to homogeneity by nickel-chelate affinity chromatography and size exclusion chromatography. Consistent with the predicted molecular mass (34.9 kDa), the major ChoX peak corresponded with a calculated molecular mass of 34.75 kDa (according to the elution volumes of the standards) (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material). Furthermore, no differences were observed when the protein was incubated in the presence or absence of choline, indicating that this protein binds to its substrate as a monomer.

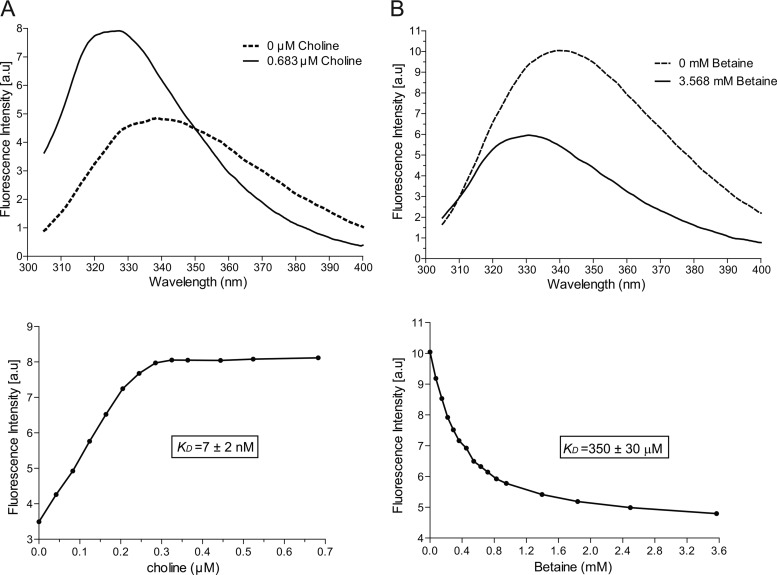

In order to demonstrate the binding activity of ChoX, we performed a fluorescence-based equilibrium-binding assay by taking advantage of the quenching of intrinsic tryptophan fluorescence as described previously for the S. meliloti homologue (26). As shown in Fig. 5A, the emission spectrum resulted in an 11-nm blue shift from 338.5 nm in the absence of substrate to 327.5 nm in the presence of 0.68 μM choline. Likewise, the binding of betaine to the periplasmic-binding protein induced a 9.0-nm emission spectrum shift from 339.5 nm in the absence of betaine to 330.5 nm in the presence of 3.57 mM betaine. Fluorescence intensities at fixed wavelengths (340 nm for betaine and 317 nm for the other substrates) were used to determine the dissociation constant (KD) according to a single-site model (Fig. 5B). The measured dissociation constants were 7 ± 2 nM for choline and 350 ± 30 μM for betaine, whereas no specific binding of ChoX to l-carnitine or l-proline was observed (see Fig. S3 in the supplemental material). Taken together, these results indicate that ChoX is a high-affinity periplasmic-binding protein specific to choline.

Fig 5.

Ligand-binding analysis of B. abortus ChoX. The binding affinities of B. abortus ChoX for choline and betaine were determined via intrinsic tryptophan fluorescence quenching after the addition of different ligand concentrations to purified ChoX. (A) Emission spectra of ChoX (200 nM) in the absence or presence of saturating amounts of choline (upper panel). Changes in fluorescence intensities at a fixed wavelength (317 nm) were plotted against the ligand concentration (lower panel) and were used for calculation of the dissociation constants (KD). (B) Binding of betaine to ChoX (1 μM) under saturating concentrations of the substrate (upper panel). The changes in emissions at 340 nm were used to determine the binding affinities (lower panel). All data sets were fitted to the equation of a single-binding-site model, and each KD was calculated as the mean value ± the standard deviation (SD) from at least three independent experiments. a.u, arbitrary units.

ChoX is required for choline uptake during the intracellular stages of B. abortus.

It has been described that the synthesis of PC through the PCS pathway is important for the intracellular stages of B. abortus and for virulence in the mouse infection model (8, 9). Upon internalization, Brucella spp. are found in a modified phagosome called the Brucella-containing vacuole (BCV), in which the bacterium survives and eventually replicates (15). The BCV suffers a maturation process characterized by limited interactions with the endocytic pathway and sustained interactions with the endoplasmic reticulum to form the replicative BCV (34). The BCV has been postulated to be a nutrient-limited low-oxygen compartment (35), and given that PC synthesis depends largely on choline uptake via ChoX only at low micromolar concentrations of choline, we then assessed whether choline uptake via ChoX is also important for the intracellular stages of B. abortus.

To this end, we infected J774A.1 macrophage-like cells with B. abortus strain 2308 and the B. abortus ΔchoX and B. abortus pcs mutants. In order to prevent choline transport before the host cell internalization has taken place, the bacteria were cultured in choline-free medium and the cell line was maintained in choline-free medium during the entire internalization process. Afterward, the cell culture medium was restored, and antibiotics were added to kill noninternalized bacteria, as described in Materials and Methods.

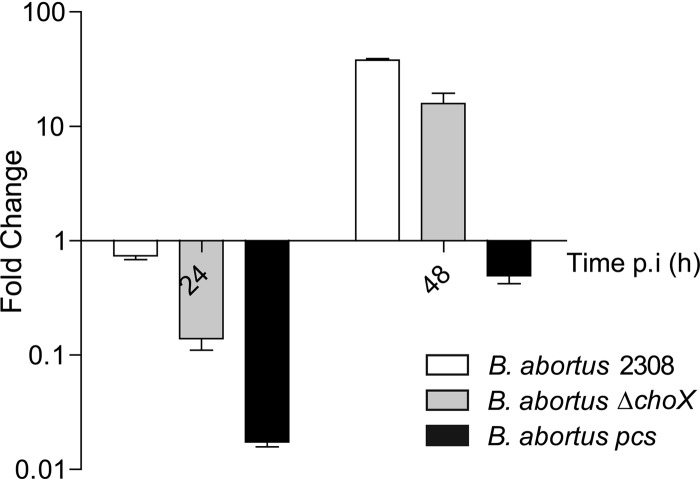

The number of CFU recovered from J774.A1 macrophages infected with the B. abortus ΔchoX mutant displayed no significant differences with the wild-type or the B. abortus pcs mutant at 4 h p.i., indicating that choline uptake and PC synthesis are not relevant in the early intracellular stages (see Fig. S4A in the supplemental material). However, at 24 h p.i., both the B. abortus ΔchoX and B. abortus pcs mutants showed significant drops in their CFU counts in comparison to that of the wild type; this indicates that both ChoX and the PCS pathway are important for the intracellular survival of B. abortus (Fig. 6). Subsequently, the number of CFU of the B. abortus ΔchoX mutant increased exponentially, with growth rates comparable to that of the wild type, whereas the intracellular replication of the B. abortus pcs mutant remained affected. When the wild-type strain and the B. abortus ΔchoX mutant were cultured before infection in a choline-rich medium, such as TSB, there were no significant differences in the numbers of CFU recovered from cells at the analyzed times (see Fig. S4B in the supplemental material).

Fig 6.

ChoX is required for the early intracellular steps of B. abortus. Intracellular replication of B. abortus 2308, B. abortus pcs, and B. abortus ΔchoX in J774.A1 macrophages (MOI of 50:1). The viabilities of the intracellular bacteria were determined at 4 h, 24 h, and 48 h postinfection by enumeration of the CFU. The data represent the relative changes in the numbers of CFU/ml at the indicated times over the CFU/ml at 4 h p.i. The values are the mean relative change of CFU/ml ± the SD from a representative experiment (of three independent measurements) performed in duplicate.

These results indicate that B. abortus depends on the high-affinity choline-binding protein ChoX during the first stage of intracellular infection, suggesting that choline concentrations in the early and/or intermediate BCV are below 100 μM. Once the replicative BCV has been formed, ChoX is not required, which implies that this BCV is a choline-rich compartment and that another yet-uncharacterized choline uptake system is required for PC synthesis.

To analyze the role of ChoX in virulence, mice were intragastrically inoculated with a choline-depleted wild-type strain, the B. abortus ΔchoX mutant, or the B. abortus pcs mutant, and 30 days later, the numbers of CFU recovered from the spleens were quantified. The numbers of CFU from B. abortus ΔchoX-infected mice were not significantly different than those from mice infected with the parental strain, whereas the virulence of the B. abortus pcs mutant was severely impaired (see Fig. S5 in the supplemental material). These results confirm the importance of PC synthesis for B. abortus virulence and indicate that ChoX is dispensable for choline transport in this infection model.

DISCUSSION

Phosphatidylcholine is a major component of the Brucella cell envelope and is an important virulence determinant in cells and in mouse infection models (12). This pathogen has a clear preference for using the PCS pathway rather than the PmtA pathway for PC synthesis, and in this work, we have provided additional evidence supporting this notion (8, 9). When B. abortus 2308 was cultured in a medium containing radiolabeled choline or acetate, the bulk of the label was transferred to PC, whereas no radiolabeled spot corresponding to PC was detected in the B. abortus pcs mutant (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). Thus, based on these and previous findings, and the fact that the PCS pathway depends on choline for PC biosynthesis, we hypothesized that B. abortus encodes a choline transporter that is responsible for choline uptake and, hence, for PC formation.

To characterize the choline transport activities of B. abortus, we assessed the uptake of radiolabeled choline. We observed that the presence of choline in the medium inhibits its own transport in a dose-dependent manner. Choline uptake reached a maximum incorporation at 2 μM choline, but the uptake kinetics decreased 250- and 400-fold when choline concentrations in the medium were 10 and 100 μM (Fig. 1). Moreover, choline uptake in the B. abortus pcs mutant was reduced by 1 order of magnitude relative to that of the wild type (Fig. 4), indicating that choline transport and PC biosynthesis are controlled by a strict yet-unidentified regulatory mechanism that depends on environmental choline concentrations. The opposite effect was observed in S. meliloti and Agrobacterium tumefaciens, two other members of the α-2 subclass of proteobacteria, where choline acts as an inducer of the ChoXWV transport system (7, 22). One interesting investigation for future studies will be to elucidate the molecular mechanism underlying this regulation of choline uptake.

In order to identify the putative choline transporter of B. abortus and take advantage of the dependence of PC biosynthesis on exogenous choline and the kinetics of choline uptake, we analyzed the ability of three mutants to synthesize PC from radiolabeled choline in putative choline-binding proteins (Fig. 2 and 3). This procedure allowed us to identify a 969-bp ORF (BAB1_1593) that encodes a typical soluble ligand-binding periplasmic protein. This gene, named choX, seems to be part of an operon that encodes an integral inner membrane protein (BAB1_1594) and an ATPase (BAB1_1595). Additionally, other important characteristics of this protein are the presence of an OpuAC domain (implicated in quaternary ammonium compound transport) and high similarity to the S. meliloti choline transporter ChoX (Fig. 2).

Deletion of the choX gene completely abrogated PC synthesis at choline concentrations below 10 μM (Fig. 3A), thus suggesting that this protein is important for PC synthesis via the PCS pathway. The restoration of PC synthesis observed when the B. abortus ΔchoX mutant was incubated at choline concentrations higher than 100 μM suggests that B. abortus contains at least one extra transporter involved in low-affinity choline uptake. This putative quaternary amine transporter, which is not one of the other two ABC transporter candidates evaluated (Fig. 3B), could be responsible for low-affinity choline uptake and, hence, PC synthesis in the B. abortus ΔchoX mutant. Alternatively, the transmembrane component ChoW (BAB1_1594) might contain a low-affinity binding site for the translocation of choline across the bacterial membrane, as this was demonstrated for other ABC transporter mutants that lacked the high-affinity periplasmic binding component but retained certain substrate specificities even with reduced substrate affinities (36, 37). These hypotheses are currently being tested. Nevertheless, while a low-affinity choline transport mechanism remains to be identified, in this work, we describe an ABC substrate-binding protein that participates in high-affinity choline uptake. As expected, the choline uptake experiments demonstrated that at low micromolar concentrations of choline, the B. abortus ΔchoX mutant was completely impaired in its ability to transport choline, while no phenotypic defect was found in the complemented strain (Fig. 4).

Betaine and choline are known components of plant and animal tissues, with betaine being associated most often with osmoprotection and choline being present as a precursor for the major membrane lipid PC. As choline is also the precursor of glycine-betaine, it can function as an osmoprotectant, as has been demonstrated already for many bacterial species (38, 39).

In this study, we have established that purified ChoX is a 322-amino acid (aa) protein that binds choline with extremely high affinity and selectivity (KD of 7 nM), but this is not the case for betaine, l-proline, or l-carnitine (Fig. 5; see also Fig. S3 in the supplemental material). The extremely high affinity of B. abortus ChoX for choline is 3 orders of magnitude higher than that of its closest ChoX orthologs from S. meliloti and A. tumefaciens (7, 22). Alignment analysis (Fig. 2) indicated that B. abortus ChoX conserves the four aromatic amino acids (W43, W90, Y119, and W205) that form the hydrophobic pocket required for choline binding, as revealed in the three-dimensional structure of S. meliloti ChoX (25, 26). However, in contrast to the N89 and M91 neighboring W90 in the polypeptide chain of S. meliloti ChoX, the B. abortus choline-binding protein contains two nonconservative substitutions, Y93 and N95, which may alter the structure of the choline-binding pocket. These substitutions might be the reason for the extremely high affinity of B. abortus ChoX and the peculiar substrate inhibitions observed in the choline uptake assays.

Homodimerization of the quaternary ammonium compound transporter was demonstrated previously for the osmoregulatory OpuA transporter of Lactococcus lactis (40). For this reason, the possibility of homodimerization was also evaluated for B. abortus ChoX. As in the S. meliloti and A. tumefaciens ChoX proteins, no dimer formation was observed upon choline binding.

Several lines of evidence suggest that the Brucella-containing vacuole (BCV) is a nutrient-limited low-oxygen neutral or slightly acidic membrane-bound compartment in which Brucella survives and eventually replicates (35). Given the importance of PC synthesis for the intracellular stages of B. abortus (8, 9), we evaluated the role of ChoX in B. abortus virulence. We could not detect any obvious phenotypic defect in the B. abortus ΔchoX mutant when the bacteria were grown in rich TSB medium before infection (see Fig. S4B in the supplemental material). However, when the mutant was cultured in choline-deprived minimal medium, a clear defect in the number of intracellular CFU recovered at 24 h postinfection was observed (Fig. 6; see also Fig. S4A in the supplemental material). This finding indicates that ChoX activity is required during the first phase of B. abortus intracellular traffic, suggesting that choline concentrations in the early and intermediate BCVs are in the low micromolar range. Once the replicative BCV is established, ChoX activity is not necessary, although the biosynthesis of PC via the PCS pathway is essential for intracellular replication.

Likewise, PCS activity is required for infection in mice, while ChoX activity is not. Since the concentration of physiological choline in plasma is ∼10 μM (41–43), we hypothesize that choline concentrations in the replicative BCVs are high enough to achieve choline uptake for PC synthesis through low-affinity transport activities and are independent of the high-affinity choline-binding protein ChoX.

Although PC is quantitatively the most important metabolite of choline, it also serves as a precursor of glycine-betaine, a compatible solute important for osmoadaptation and a labile donor of methyl groups for the remethylation of homocysteine to methionine (3). At this stage, we cannot rule out that the deficiency in the intracellular survival of the B. abortus ΔchoX mutant is the result of another important function of choline that is not related to PC synthesis.

In the present work, we describe a fundamental component of the PC biosynthetic pathway in B. abortus, a high-affinity choline transporter that is required for PC synthesis under low environmental choline concentrations. At present, many questions remain to be answered, and it will be of great interest to learn exactly how this transporter works and the mechanisms by which it is regulated. Currently, all these questions are under investigation.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This study has been supported by grant PICT 2007 from Agencia Nacional de Promoción Científica y Tecnológica (ANPCyT) (http://www.agencia.gov.ar/), Argentina (to D.J.C.).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 16 November 2012

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/JB.01929-12.

REFERENCES

- 1. Blusztajn JK. 1998. Choline, a vital amine. Science 281: 794–795 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Michel V, Yuan Z, Ramsubir S, Bakovic M. 2006. Choline transport for phospholipid synthesis. Exp. Biol. Med. (Maywood) 231: 490–504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Zeisel SH, Da Costa KA, Franklin PD, Alexander EA, Lamont JT, Sheard NF, Beiser A. 1991. Choline, an essential nutrient for humans. FASEB J. 5: 2093–2098 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Zeisel SH. 1997. Choline: essential for brain development and function. Adv. Pediatr. 44: 263–295 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Aktas M, Wessel M, Hacker S, Klusener S, Gleichenhagen J, Narberhaus F. 2010. Phosphatidylcholine biosynthesis and its significance in bacteria interacting with eukaryotic cells. Eur. J. Cell Biol. 89: 888–894 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Sohlenkamp C, Lopez-Lara IM, Geiger O. 2003. Biosynthesis of phosphatidylcholine in bacteria. Prog. Lipid Res. 42: 115–162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Aktas M, Jost KA, Fritz C, Narberhaus F. 2011. Choline uptake in Agrobacterium tumefaciens by the high-affinity ChoXWV transporter. J. Bacteriol. 193: 5119–5129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Comerci DJ, Altabe S, de Mendoza D, Ugalde RA. 2006. Brucella abortus synthesizes phosphatidylcholine from choline provided by the host. J. Bacteriol. 188: 1929–1934 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Conde-Alvarez R, Grilló MJ, Salcedo SP, de Miguel MJ, Fugier E, Gorvel JP, Moriyón I, Iriarte M. 2006. Synthesis of phosphatidylcholine, a typical eukaryotic phospholipid, is necessary for full virulence of the intracellular bacterial parasite Brucella abortus. Cell. Microbiol. 8: 1322–1335 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Conover GM, Martinez-Morales F, Heidtman MI, Luo ZQ, Tang M, Chen C, Geiger O, Isberg RR. 2008. Phosphatidylcholine synthesis is required for optimal function of Legionella pneumophila virulence determinants. Cell. Microbiol. 10: 514–528 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Wessel M, Klüsener S, Gödeke J, Fritz C, Hacker S, Narberhaus F. 2006. Virulence of Agrobacterium tumefaciens requires phosphatidylcholine in the bacterial membrane. Mol. Microbiol. 62: 906–915 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Thiele OW, Kehr W. 1969. The “free” lipids of Brucella abortus Bang. Concerning the neutral lipids. Eur. J. Biochem. 9: 167–175 (In German.) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Corbel MJ. 1997. Brucellosis: an overview. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 3: 213–221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Moreno E, Moriyon I. 2002. Brucella melitensis: a nasty bug with hidden credentials for virulence. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 99: 1–3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Celli J, de Chastellier C, Franchini DM, Pizarro-Cerda J, Moreno E, Gorvel JP. 2003. Brucella evades macrophage killing via VirB-dependent sustained interactions with the endoplasmic reticulum. J. Exp. Med. 198: 545–556 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Moriyón I, López-Goñi I. 1998. Structure and properties of the outer membranes of Brucella abortus and Brucella melitensis. Int. Microbiol. 1: 19–26 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Sohlenkamp C, de Rudder KE, Rohrs VV, Lopez-Lara IM, Geiger O. 2000. Cloning and characterization of the gene for phosphatidylcholine synthase. J. Biol. Chem. 275: 27500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. de Rudder KE, Sohlenkamp C, Geiger O. 1999. Plant-exuded choline is used for rhizobial membrane lipid biosynthesis by phosphatidylcholine synthase. J. Biol. Chem. 274:20011–20016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kent C, Gee P, Lee SY, Bian X, Fenno JC. 2004. A CDP-choline pathway for phosphatidylcholine biosynthesis in Treponema denticola. Mol. Microbiol. 51: 471–481 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lopez-Lara IM, Geiger O. 2001. Novel pathway for phosphatidylcholine biosynthesis in bacteria associated with eukaryotes. J. Biotechnol. 91: 211–221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Martinez-Morales F, Schobert M, Lopez-Lara IM, Geiger O. 2003. Pathways for phosphatidylcholine biosynthesis in bacteria. Microbiology 149: 3461–3471 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Dupont L, Garcia I, Poggi MC, Alloing G, Mandon K, Le Rudulier DD. 2004. The Sinorhizobium meliloti ABC transporter Cho is highly specific for choline and expressed in bacteroids from Medicago sativa nodules. J. Bacteriol. 186: 5988–5996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Styrvold OB, Falkenberg P, Landfald B, Eshoo MW, Bjornsen T, Strom AR. 1986. Selection, mapping, and characterization of osmoregulatory mutants of Escherichia coli blocked in the choline-glycine betaine pathway. J. Bacteriol. 165: 856–863 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Chen C, Malek AA, Wargo MJ, Hogan DA, Beattie GA. 2010. The ATP-binding cassette transporter Cbc (choline/betaine/carnitine) recruits multiple substrate-binding proteins with strong specificity for distinct quaternary ammonium compounds. Mol. Microbiol. 75: 29–45 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Oswald C, Smits SH, Höing M, Bremer E, Schmitt L. 2009. Structural analysis of the choline-binding protein ChoX in a semi-closed and ligand-free conformation. Biol. Chem. 390: 1163–1170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Oswald C, Smits SH, Höing M, Sohn-Bösser L, Dupont L, Le Rudulier D, Schmitt L, Bremer E. 2008. Crystal structures of the choline/acetylcholine substrate-binding protein ChoX from Sinorhizobium meliloti in the liganded and unliganded-closed states. J. Biol. Chem. 283: 32848–32859 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Gerhardt P. 1958. The nutrition of brucellae. Bacteriol. Rev. 22: 81–98 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Bligh EG, Dyer WJ. 1959. A rapid method of total lipid extraction and purification. Can. J. Biochem. Physiol. 37: 911–917 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Punta M, Coggill PC, Eberhardt RY, Mistry J, Tate J, Boursnell C, Pang N, Forslund K, Ceric G, Clements J, Heger A, Holm L, Sonnhammer EL, Eddy SR, Bateman A, Finn RD. 2012. The Pfam protein families database. Nucleic Acids Res. 40: D290–D301 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Altschul SF, Madden TL, Schaffer AA, Zhang J, Zhang Z, Miller W, Lipman DJ. 1997. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 25: 3389–3402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Thompson JD, Higgins DG, Gibson TJ. 1994. CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 22: 4673–4680 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Sieira R, Comerci DJ, Pietrasanta LI, Ugalde RA. 2004. Integration host factor is involved in transcriptional regulation of the Brucella abortus virB operon. Mol. Microbiol. 54: 808–822 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Marchesini MI, Ugalde JE, Czibener C, Comerci DJ, Ugalde RA. 2004. N-terminal-capturing screening system for the isolation of Brucella abortus genes encoding surface exposed and secreted proteins. Microb. Pathog. 37: 95–105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Celli J, Salcedo SP, Gorvel JP. 2005. Brucella coopts the small GTPase Sar1 for intracellular replication. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 102: 1673–1678 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Kohler S, Foulongne V, Ouahrani-Bettache S, Bourg G, Teyssier J, Ramuz M, Liautard JP. 2002. The analysis of the intramacrophagic virulome of Brucella suis deciphers the environment encountered by the pathogen inside the macrophage host cell. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 99: 15711–15716 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Treptow NA, Shuman HA. 1985. Genetic evidence for substrate and periplasmic-binding-protein recognition by the MalF and MalG proteins, cytoplasmic membrane components of the Escherichia coli maltose transport system. J. Bacteriol. 163: 654–660 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Wright L, Blagova E, Levdikov VM, Brannigan JA, Pattenden RJ, Chambers J, Wilkinson AJ. 2004. Crystallization of the oligopeptide-binding protein AppA from Bacillus subtilis. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 60: 175–177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Smith LT, Pocard JA, Bernard T, Le Rudulier D. 1988. Osmotic control of glycine betaine biosynthesis and degradation in Rhizobium meliloti. J. Bacteriol. 170: 3142–3149 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Boch J, Kempf B, Bremer E. 1994. Osmoregulation in Bacillus subtilis: synthesis of the osmoprotectant glycine betaine from exogenously provided choline. J. Bacteriol. 176: 5364–5371 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. van der Heide T, Poolman B. 2000. Osmoregulated ABC-transport system of Lactococcus lactis senses water stress via changes in the physical state of the membrane. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 97: 7102–7106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Konstantinova SV, Tell GS, Vollset SE, Nygard O, Bleie O, Ueland PM. 2008. Divergent associations of plasma choline and betaine with components of metabolic syndrome in middle age and elderly men and women. J. Nutr. 138: 914–920 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Lockman PR, Allen DD. 2002. The transport of choline. Drug Dev. Ind. Pharm. 28: 749–771 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Pomfret EA, daCosta KA, Schurman LL, Zeisel SH. 1989. Measurement of choline and choline metabolite concentrations using high-pressure liquid chromatography and gas chromatography-mass spectrometry. Anal. Biochem. 180: 85–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.