Abstract

Context

Although previous researchers have begun to identify sources of athletic training student stress, the specific reasons for student frustrations are not yet fully understood. It is important for athletic training administrators to understand sources of student frustration to provide a supportive learning environment.

Objective

To determine the factors that lead to feelings of frustration while completing a professional athletic training education program (ATEP).

Design

Qualitative study.

Setting

National Athletic Trainers' Association (NATA) accredited postprofessional education program.

Patients or Other Participants

Fourteen successful graduates (12 women, 2 men) of accredited professional undergraduate ATEPs enrolled in an NATA-accredited postprofessional education program.

Data Collection and Analysis

We conducted semistructured interviews and analyzed data with a grounded theory approach using open, axial, and selective coding procedures. We negotiated over the coding scheme and performed peer debriefings and member checks to ensure trustworthiness of the results.

Results

Four themes emerged from the data: (1) Athletic training student frustrations appear to stem from the amount of stress involved in completing an ATEP, leading to anxiety and feelings of being overwhelmed. (2) The interactions students have with classmates, faculty, and preceptors can also be a source of frustration for athletic training students. (3) Monotonous clinical experiences often left students feeling disengaged. (4) Students questioned entering the athletic training profession because of the fear of work-life balance problems and low compensation.

Conclusions

In order to reduce frustration, athletic training education programs should validate students' decisions to pursue athletic training and validate their contributions to the ATEP; provide clinical education experiences with graded autonomy; encourage positive personal interactions between students, faculty, and preceptors; and successfully model the benefits of a career in athletic training.

Key Words: stress, retention, matriculation

Key Points

-

•

Graduates of athletic training education programs experience numerous pressures and stresses over their academic career.

-

•

Negative interactions with fellow students and instructors in addition to monotonous clinical experiences can increase frustration levels among athletic training students.

-

•

Athletic training education programs are encouraged to foster a dynamic, positive, and nurturing learning environment in order to reduce athletic training students' frustrations.

Exploring potential threats to athletic training student success is becoming more valuable to athletic training educators. Retaining and graduating strong students is a key factor to preserve the status and quality of athletic training education programs (ATEPs).1 Recruits today have a much larger range of health care-related programs from which to choose,2 making an ATEP's reputation increasingly important. Fostering a supportive learning environment for students may improve retention rates and supply the workforce with sufficient clinicians as the profession expects to see a 37% increase in the number of positions available by the year 2018.3

Previous researchers4 have found that students who switch from athletic training to different academic programs often do so because of poor integration into the academic and clinical portions of their ATEP. Integration is achieved when students find congruency with the ATEP community, which in turn enhances commitments to their program and educational goals5 by engaging them in a positive atmosphere. Stress and student frustration occur when students are not engaged appropriately with graded autonomy during clinical education.6 This finding is unfortunate as many students spend much of their clinical education experiences unengaged.7 Athletic training students (ATSs) have also listed a lack of respect during their clinical experiences as a point of frustration.6 The time commitment of clinical education and the wide range of responsibilities ATSs undertake have been shown to result in burnout, especially during the senior year.8 Other work9 has identified academic and financial concerns as the greatest sources of stress for ATSs, especially during midterms and the end of the semester due to examinations. Finally, stress levels have been found to be higher for females, seniors, and older students.10 Sources of ATS stress, frustration, and burnout can not only hinder integration but also lead students toward feelings of apathy for their studies,9 thoughts of departing their ATEP,4 or contemplations of leaving the profession.8

Although sources of ATS stress and burnout have begun to be acknowledged, the factors that may increase student frustrations while completing their undergraduate degree are yet to be fully understood. It is important for athletic training faculty, staff, and preceptors to more fully understand the sources of ATSs' frustrations to provide a supportive learning environment. Therefore, the purpose of this research was to describe which factors caused frustration for recent graduates enrolled in a National Athletic Trainers' Association (NATA) accredited postprofessional degree program. We felt exploring factors that frustrate successful graduates seeking advanced training in athletic training would lead to an understanding of how to provide an educational environment capable of fostering student success.

METHODS

We chose to use qualitative methods to allow us to understand student experiences in ATEPs in a holistic, complete manner.11 We asked participants to volunteer for an in-depth, semistructured interview lasting approximately 30 minutes. Keeping the interviews semistructured allowed the data collection to remain flexible and dynamic, as we were able to ask the participants to elaborate where appropriate. The semistructured nature of the interviews also facilitated follow-up questioning, which allowed us to ensure that the interview transcripts were fully detailed. The interview questions were devised based on previous work examining the reasons why students enrolled in an introduction to sports medicine class were not interested in pursuing a career in athletic training2 and reasons for departure among students who left an ATEP.4 We asked participants questions about their specific experiences during their undergraduate degree programs. Examples of interview questions can be seen in the Table. An athletic trainer (AT) who was independent from the researchers and experienced in qualitative research examined the interview questions for content. We also had a recently certified AT who was independent from the researchers pilot test the questions for clarity. The institutional review board of the host institution approved this research.

Table.

Example Interview Questions

| Can you describe what, if anything, frustrated you while you were in your ATEP? Please explain. |

| During your professional preparation, either in the classroom, clinical site, or in some other aspect of your education, was there a specific event where you experienced the feeling that, “I am not sure I have what it takes to be an athletic trainer”? Please explain. |

| Did you ever think of leaving your ATEP? Why or why not? If so, to go to which other program? |

| Did you have classmates who left the ATEP? If so, why do you think they left? What program do you think they went to? |

| What least attracts you to a career in athletic training? Please explain. |

Abbreviation: ATEP, athletic training education program.

Participants

Fourteen students (12 women, 2 men; mean age = 22.21 ± 1.05 years; 11 certified) who were enrolled in one NATA accredited postprofessional education program, volunteered to participate in this study. The participants came from a convenience sample consisting of students seeking advanced education in athletic training. The participants represented a wide range of Commission on Accreditation of Athletic Training Education (CAATE)-accredited professional undergraduate ATEPs across the United States. Specifically, our participants graduated from 14 different programs from 3 main Carnegie Foundation Classifications; 6 from research institutions, 6 from master's institutions, and 2 from baccalaureate colleges.12 We also had representation from 11 different states and 6 of the 10 NATA districts, illustrating the geographic diversity of our participants' programs. We settled on our population because we thought these participants would have different perspectives than a population from only one undergraduate institution or only one geographic region.

Data Collection and Analysis

We obtained permission to talk to the group of potential participants that we identified from their graduate program director. We chose to recruit our participants at the end of one of their graduate classes. The lead investigator asked for volunteers to take part in the study after explaining the purpose, risks, and benefits of participation as well as giving example interview questions to show the volunteers what to expect during data collection. The lead investigator also informed the potential participants that they would have the ability to withdraw from the study at any time during data collection or skip without penalty any questions they did not feel comfortable answering. Participants gave informed consent to participate by signing up for an interview date and time. Fourteen of the 15 present members of the graduate class agreed to participate in the study. The lead investigator completed tape recorded, in-person, one-on-one semistructured interviews with each of the participants. All of the interviews occurred within 2 months of the participants' undergraduate graduation. We monitored the data for saturation throughout the data- collection process by constantly examining the data for new information and later transcribed the interviews verbatim, giving each participant an identification number and pseudonym to facilitate data analysis while maintaining confidentiality.

We chose to use grounded theory to analyze the data, as it helps explain patterns of behavior for selected groups.13 Our primary purpose was to generate a theory to explain factors leading to recent ATEP graduates becoming frustrated during their time as undergraduate students, making the selection of grounded theory appropriate. We allowed our codes to develop from the data instead of proposing an a priori scheme because we used grounded theory.14 We used NVivo (version 8; QSR International Pty Ltd, Cambridge, MA) to assist with the development of the coding scheme. We performed open, axial, and selective coding procedures to analyze the data.15 We broke the data down into discrete parts line by line, noting similarities among those parts during open coding. Axial coding involved connecting data to form major themes and subthemes. Finally, we identified central themes through selective coding, a process involving relating themes to one another and validating the relationships among those themes.15 We wrote analytic memos during the coding process to maintain interpretive credibility of our data analysis.16 Both authors have been trained in qualitative methods through graduate-level coursework and are athletic training educators.

Trustworthiness

We took multiple measures to ensure trustworthiness (ie, authenticity of the data and conclusions)11 throughout this study. We transcribed the interviews verbatim before coding and subsequent data analysis. Initially, we analyzed the interview data independently and then negotiated over the coding themes until we reached 100% agreement. The negotiation process involved combining and renaming codes as needed in order to reach agreement on specific themes and subthemes. We also performed member checks with all of the participants to verify the accuracy of our transcriptions and interpretations. Finally, a third researcher trained in qualitative methods with no stake in the current study examined the coding scheme and verified the final themes.

RESULTS

Coding and subsequent analysis of the interview transcripts revealed the following 4 themes:

-

1.

Our participants became frustrated because of the student life strain involved in program completion.

-

2.

The negative actions of others can be a source of stress for ATSs.

-

3.

Monotonous clinical experiences often cause ATSs to feel disengaged.

-

4.

Career considerations affect decisions to enter the profession of athletic training.

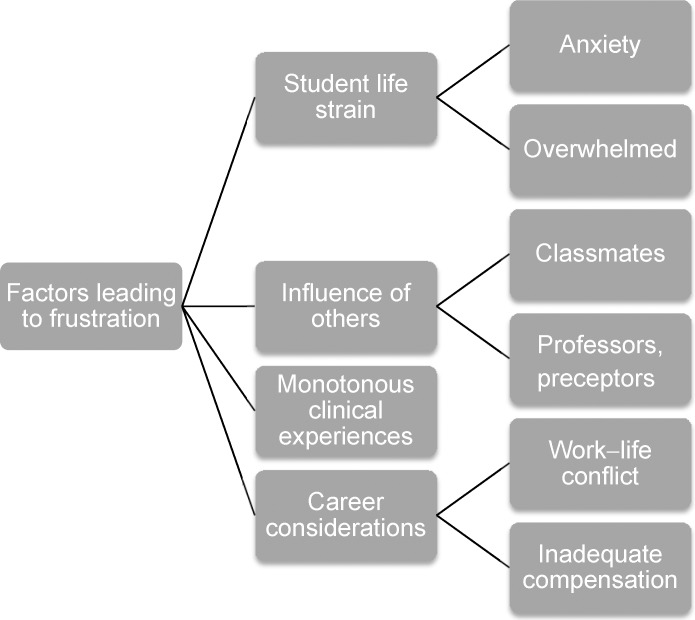

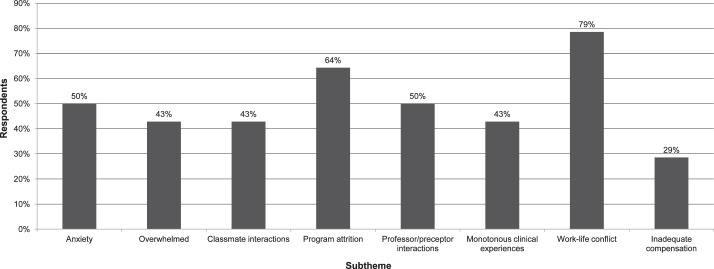

The relationships and construction of the primary themes from the subthemes that we identified in the axial coding process are illustrated in Figure 1. The percentages of participants who identified each subtheme as a source of frustration are displayed in Figure 2.

Figure 1.

Themes identified as factors leading to athletic training student frustrations.

Figure 2.

Percentage of participants responding to each subtheme.

Student Strain

Participants often became frustrated with the amount of time it took to complete the ATEP, which led to anxiety (7 of 14) and feelings of being overwhelmed (6 of 14). One participant (#14) explained her anxiety about belonging in her program by stating

Um, I guess my sophomore [year] with all, the way [institution's name] program is, your hardest classes are sophomore year I guess, and I definitely, there were many times when I was like, I don't know if I can do this, I don't know if I'm smart enough to be an athletic trainer. You learn so much stuff at one time.

Another participant (#8) explained his anxiety when first starting in his ATEP:

Everything was just kind of thrown at you all at once. It was more scary instead of encouraging. You would think that it would be kind of the opposite. . . Just hearing about it made me kind of want to not do it.

Later in the conversation, he went on to explain his anxiety over his clinical skills. He said, “I mean I've definitely gotten down at times, like you know when you're starting off and you do an eval[uation] and you kind of miss that big thing.” Participant #5 also felt anxious about her clinical skills. She explained how she second guessed her skills during clinical education: “I was like, if I was by myself, I don't know what I would do in this situation.”

Other participants discussed how they became overwhelmed while completing their ATEP requirements. Participant #14 had difficulty managing her time between didactic and clinical education:

Um, I just think I was overwhelmed, with all the coursework and then on top of having to do a lot of [clinical education] hours. I was with football a lot my sophomore year and it was a lot of time. Time management was hard.

Similarly, participant #3 stated:

There were times when it was just overwhelming if you had a lot of hard classes at one time, but you'll have that with anything. You just have to have good time management skills I guess.

Participant #4 explained why she considered changing her major during her sophomore year. “I think it was just ah, not sure of the atmosphere, like I said, of all the classes and I don't know of a specific thing. I think [I was] just overwhelmed.” Participant #2 summed up her stress trying to manage all of her responsibilities:

Having the time to do it [academic work] is what makes it difficult. So not having the time because you know you're spending 4 hours a day out at the practice field or traveling all weekend, that's what makes it difficult. It adds up and it takes a toll on you.

Finally, one participant (#6) stated:

[It was] hard for me to experience the rest of college. It just, it just sucks a lot of time out of your [schedule]. Being that young, I would think it would be hard for a lot of people to give that up.

Influence of Others

The actions of the participants' classmates, professors, and preceptors can lead to frustration while completing an athletic training degree. Distressing interactions occurred with classmates for almost half (6 of 14) of the participants. Participant #1 stated:

I think at times in the classroom, even though having the small class was really beneficial, it was hard with the same people over and over again in every class. You kinda wanted a little bit of a break at times. While it was good, it also had its drawbacks.

An example of these drawbacks was the mistrust that often occurred among classmates. Participant #8 became frustrated with the gossip that occurred within his class and explained his frustrations as “Just the bickering between each other, the lack of trust between anyone, gossip, it was just, just ridiculous.”

Most participants (9 of 14) noted that attrition within their ATEPs was common. Participant #3 described how attrition within her program caused disturbances:

I'd say what frustrated me was that other people were dropping out so like someone would drop out right before our junior year and they had already set up our clinical rotations so everyone else has to shuffle what they are doing to make up for other people's decisions I guess. It can get a little stressful when you have to switch around clinical sites or take on additional rotations at the last minute.

Overall, classmates were believed to have an influence on the frustrations felt by the participants.

Seven participants also listed interactions with professors and preceptors as a cause of frustration. Participant #2 became irritated by instructors and preceptors:

There were just so many times they would just pile on the work and then just you feel like expect us to be out there [at our clinical sites] earlier than we were supposed to be for things and just not understanding if we had a school conflict, if we had an exam, or if we're like completely burnt out. Things like that they just, they didn't really have the whole sympathy of the fact that we were full-time students taking 18 credits a semester and balancing life in addition [to clinical education].

Another participant (#10) explained how her preceptor was a poor role model:

I had the same athletic training supervisor, same CI [preceptor] and ah, he didn't have a very positive outlook on the profession. He didn't want to be there. He liked to sit in his office and play on his computer. He was a smart guy, just unmotivated, and so, um, that was a little, a lot frustrating to deal with. He was the reason [another student] ended up quitting [the program] um, after midseason. . . you could tell that he didn't want to be there and you're kind of like why are you in this profession if you don't want to do anything.

Participant #8 went to a large state flagship institution with National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) Division I athletics. He often became frustrated with the lack of communication between his professors and his preceptors. He stated, “Sometimes I just felt like the clinical side and the academic side weren't always on the same page.” He went on to describe a situation in which requirements for didactic education interfered with clinical education and concluded by saying

You're [professors] making us [students] look bad in a sense, looking like we're trying to get out of something and they [preceptors] don't understand so you guys [preceptors and professors] should just communicate.

A final interesting finding comes from participant #4. She noted that her high school AT actually tried to talk her out of seeking admission into an ATEP:

She actually said that I shouldn't get into it [athletic training], which was kind of ironic. She said it was very time consuming and not the way to go, go physical therapy, but I realize that maybe she just wasn't meant for this type of field and that I just enjoyed it so much that it didn't matter [at] the time.

Monotonous Clinical Experiences

Unexciting clinical education experiences often left students feeling disengaged and that their time was being wasted. Six of our 14 participants listed an example of how they were not engaging in active learning during clinical education. Participant #11 considered departing his ATEP:

I was putting a ridiculous amount of hours in and basically, you know, glorified water boy, and because it is big-time athletics, they really can't let you have too, too much independence. They do need to oversee everything and um, I was there all the time and wasting a lot of time and filling up a lot of water cups and not doing too much else. You could set someone up with [electrical] stim[ulation]. I mean you started doing injury evaluations but at the same time all your work, someone else was going to redo it again afterwards. It didn't feel like, maybe because someone else was going to do it, you didn't put your whole heart into it because you knew what you found really didn't matter whether you got it right or wrong.

Participant #4 became frustrated during her clinical experience with football:

My [preceptor] there wasn't the most organized person. He would have you come in for ridiculous times and some of us would just be sitting around doing nothing. And I was like, I could be studying or doing something more productive. That was probably one of the most frustrating things.

Participant #9 explained why she became frustrated with her clinical experiences:

I think at [institution's name] we were kind of shadowed too much. We didn't really have enough individual interaction with the athletes, like we were on a short leash.

Participant #13 also stated:

You're really not doing all that much and that's kind of frustrating for me because I don't like, you know what I mean, [to] sit in the athletic training room and, you know, twiddle my thumbs.

Career Considerations

Perceived future work-life conflict and inadequate compensation emerged as reasons for participants being anxious about entering the athletic training profession. Most (11 of 14) mentioned the perceived time commitment involved in being an AT as a source of frustration. Participant #2 planned to balance family responsibilities with a career in athletic training:

Um, I mean I would like to be able to have a family some day so I just, you know, being able to have the time for my family and be able to devote [time] to them, you know as much as I can. I'm preparing to have to make a lot of sacrifices and hopefully not have to sacrifice too much with my job but at the same time, I will have to adjust in order to have my goals for family and things like that are a little bit higher priority. Work isn't going to be my life, just be a part of it.

Participant #6 responded to the question of what least attracted her to a career in AT:

The hours, I would think. Eventually I want to start a family, um, so that's going to be difficult, but I'm not looking down that barrel anytime soon, so I'm not worried about it now, but I know for sure it'll be an issue later ‘cause I won't want to give up my job, but I'll also want to spend a lot of time with my kids, so that kind of freaks me out.

It is interesting to note this theme also emerged from one of the male participant's interviews. Participant #8 explained why he questioned finishing a degree in athletic training:

There were times where it's midnight and I'm getting done with a practice or a game on like a Friday night or a Saturday night. It's those types where you're always kind of like I don't know if this is for me, you know. I kind of want, you know, a family. So that would probably be the biggest, just the crazy hours where you're just sitting there kind of like ah, this is fine now because I have no schedule but later in life, looking into the future, this could be totally different.

Low compensation was another theme that emerged from the interview data. Several (4 of 14) participants listed compensation as a concern when they thought of securing a career in athletic training. Participant #7 responded, “not the money,” when asked what most attracts her to a career in athletic training. Three others responded, “the money,” when asked what least attracts them to a career in athletic training.

DISCUSSION

The current study provides a deeper understanding of the factors that frustrate ATSs while completing their undergraduate ATEP. This research adds to the current body of knowledge by explaining reasons not only successful ATSs but also those who chose to gain advanced training in athletic training became frustrated. It is important to note, however, that the themes did not present in isolation; some overlap occurred.

The purpose of using a grounded theory approach to data analysis is to create a theory based on the data: in this case, the interviews.17 The overlap that occurred between our themes helped us develop a theory to decrease ATSs' frustrations. We believe providing a supportive environment can counteract many of the frustrations our participants encountered while completing their ATEP. We settled on this overarching theme because many of the frustrations occurred due to an environment that was not sympathetic to the needs of the ATSs. We also believe an encouraging and understanding environment can counteract the frustrations ATSs encounter by allowing students to voice concerns and talk through difficult situations they encounter.

Student Strain

The participants reported being overwhelmed at times trying to balance the time requirements of clinical and didactic education. Students devote an immense amount of time to complete an ATEP because of the rigors of the coursework and clinical education expectations,9 leading to our finding of students becoming anxious and overwhelmed. Several participants became anxious about finishing a degree because they were not sure they could be successful ATs. Our participants also listed taking several difficult classes simultaneously and the time commitment necessary to successfully meet clinical education responsibilities as common reasons for becoming overwhelmed. Our finding is similar to that of previous authors9 who found academics to be a major source of stress for ATSs. We believe student stress over academics may stem from retention criteria ATEPs are required to have in place by the CAATE.18 Athletic training education programs often have grade point average cutoffs and grade thresholds that must be met to allow students to successfully matriculate. We also speculate that students in ATEPs are competitive, often seeking to outperform their classmates. Competition may be exacerbated by the small nature of ATEPs facilitating comparisons between students. In order to decrease stress over clinical education requirements, expectations should be kept reasonable to allow ATSs sufficient time for academic work and social activities, leading to full integration into campus life.19

Athletic training educators should encourage students while keeping the learning environment dynamic and interesting.19 Recognizing the success of ATSs20 is also an important factor leading to the validation of students' participation in an ATEP. We believe validating21 ATSs may be necessary to help them believe they belong in the ATEP, to overcome disconfirming experiences, and to help decrease the stress levels involved in completing an ATEP. Because ATEPs are rigorous, students may need to be reminded that they belong in the program and that they can be successful. It appears to be critically important for faculty and preceptors to understand the need for students to receive positive reinforcement, especially early in clinical education. Providing students with validation of their belonging in the ATEP may positively affect persistence decisions and improve student morale while helping them cope with their stress. Proper academic and clinical socialization may help students understand their role in the ATEP, making expectations clear and fostering mentoring relationships with classmates, faculty, staff, and preceptors.4,22 Mentoring relationships23 can provide a supportive environment for students to become socialized to professional responsibilities. It is important to note, however, that students must also be challenged. A balance must exist between support and challenge for students to remain engaged in their own learning.24

Influence of Others

Based on the fact that our results contradict earlier findings,4,22 it appears the individuals with whom ATSs interact on a daily basis have the ability to fortify or diminish students' desire to finish their degree in athletic training. Earlier researchers4,22 found peer interactions positively influenced ATS persistence decisions. Our participants listed classmate interactions as a common source of frustration for them. This finding is particularly interesting because socialization and peer-support groups for ATSs are believed to be a key factor in retention.2,4 We speculate students may spend too much time together in the close cohort style common in athletic training education. It appears to be important for ATSs to find activities outside of athletic training in which to become involved to support life balance early in their professional experiences.

Our participants also listed interactions with some professors and preceptors as stressful. In order to avoid negative experiences, faculty and preceptors should engage with students individually. Personal interactions can assist students' transition to college life25 and help socialize students into an ATEP. Often, the source of tension was a lack of communication between faculty and preceptors or a lack of understanding of the ebbs and flows of academic work by faculty and preceptors. It is interesting to note that communication problems appear to occur within ATEPs, regardless of the size and competitiveness of the intercollegiate athletics program. As many athletic training programs use multiple off-campus clinical education sites as well, it appears that students can become frustrated by a lack of communication, regardless of the level or location of their clinical assignment. Effective communication between faculty and preceptors can help improve student learning by coordinating didactic and clinical education experiences and promoting ATEP coherence.19 Based on our results, appropriate communication between faculty and staff can also facilitate a clear understanding of student expectations. Finally, faculty and preceptors must also act as professional role models to ATSs. Students enjoy clinical education because it allows them to picture themselves working as ATs in the future.22 Preceptors must properly model athletic training careers and professional behaviors because ATSs look up to them as mentors and role models.23

Monotonous Clinical Experiences

Our finding that the participants became frustrated with monotonous clinical education experiences is not surprising, as students spend 59% of their time unengaged during clinical education.7 One reason for poor clinical education experiences may be that preceptors do not have sufficient time to spend teaching students because they are fulfilling the demands of patient care.26 This issue highlights the need for constant evaluation of both clinical sites and preceptors in order to be sure that the educational needs of the students are being met. In cases where the students are spending the majority of their clinical time unengaged in learning experiences, there may be a need to discontinue the practice of assigning students to particular sites for clinical education purposes.

Several participants also mentioned they performed tedious and menial tasks (filling water coolers, cleaning, etc) while they were completing clinical education requirements. Students performing such tasks is also not surprising; it has been previously listed as a common occurrence during clinical education.1 One participant even noted that classmates dropping out of the major often led to a shifting of clinical assignments in order to provide particular sites with adequate numbers of student helpers. Practices such as this are strongly discouraged because they not only cause additional stress to the student but also foster the idea that students are in their clinical placements to work as opposed to learn.

It is important for ATSs to be properly socialized into their clinical placement to allow them to become integrated into the daily health care operations of their clinical site. Proper clinical socialization will allow students to understand their role in the health care facility while pursuing meaningful educational experiences.4 Students may become passive bystanders while their preceptor completes all health care tasks if they do not understand how they fit into the health care team.27 Students should be placed in clinical education sites that can provide engaging experiences with appropriate autonomy, allowing students to learn actively.22

In 2005, the CAATE guidelines for the supervision of AT students shifted to require preceptors to be physically present to intervene if necessary on behalf of the ATS and the patient.18 Since the implementation of stricter supervision requirements, there has been much debate among athletic training educators and clinicians about how best to develop clinical skills.28 From this discussion, the idea of situational29 or graded autonomy has come to fruition. When using supervised or graded autonomy, the preceptor uses a supervisory style based on the needs and abilities of students.29 Therefore, students perform tasks they are familiar with independently while the preceptor provides feedback on students' performance and probes students for an explanation of why their actions are appropriate.28,29 Students are then able to engage with preceptors in reflective conversations and able to self-reflect on their learning in an important way.30 We believe using the situational or graded autonomy framework for clinical education can help keep students engaged during clinical education experiences while easing the transition of taking on more responsibility because millennial students require assistance in developing the ability to make decisions on their own.31 Also, the rapport between a student and a preceptor should be a mentoring relationship to facilitate the development of student critical thinking aptitude while using skills appropriate to the student's education level.28

Career-Life Balance

Similar to previous work,2 most participants listed the irregular and long hours required for careers in athletic training as drawbacks to entering the profession. It is important to note the sex imbalance of the current study when interpreting our results, although work-life balance issues have been found for high school ATs from both sexes.32 Most of our participants were females, which means the theme of having enough time for a family is not surprising. One male participant also mentioned the difficulty an athletic training career will cause him with regard to meeting family responsibilities due to the long and late hours that may be required. Preceptors should model the ways in which they achieve work-life balance to ATSs to help reduce the anxiety over potential future stress. Athletic training education programs should also seek out and identify ATs who have achieved an appropriate work-life balance and encourage them to serve as preceptors and role models for ATSs. We recognize that work-life balance is something that many ATs continue to struggle to achieve.32,33

Several participants also listed low compensation as a drawback to entering the athletic training profession; however, these students were in the minority. We believe compensation remains a point of contention among ATs, although improvements are being made based on the low number of students who recognized it as a drawback to entering the profession. The efforts of the NATA to improve working conditions and compensation for ATs should continue. We recommend students become acquainted with the salary surveys that are published by the NATA to better understand fair compensation. We also encourage students to become members of the NATA and support initiatives to improve compensation and working conditions for ATs.

Limitations

It is important to note several limitations of the current study. Although our participants represented ATEPs from a diverse range of institutions from across the United States, it is difficult to generalize our results to a wide range of ATEPs nationwide. Our participants represented only a small portion of recent graduates from ATEPs in the United States. However, the use of qualitative methods allowed us to gain an in-depth perspective of our participants' experiences. The current study was also not sex balanced (12 women, 2 men), which may have altered our results. However, as of 2010, more than 62% of noncertified student NATA members were female, indicating an increasing number of women entering athletic training education programs.34 Finally, our participants were enrolled in an NATA-accredited postprofessional education program. Perhaps studying participants from a different population would have produced different results, as our participants were seeking advanced training in athletic training. Nevertheless, we believe the current study is a first step in gaining an in-depth analysis of frustrations among ATSs.

CONCLUSIONS

We believe the current study is important, as many students who dropped out of ATEPs that have been studied previously4,20 may have done so because they could not handle the rigor of the program.20 The current study focuses on high-achieving students who have chosen to pursue an advanced degree in athletic training, the students educators should want to strive to keep in their ATEPs. Therefore, faculty should work to manipulate the factors found in the present study to provide a supportive environment for students who have the ability to finish an ATEP and be successful future professionals.

We identified 4 common sources of frustration and stress among students while completing the requirements of an ATEP. Faculty and preceptors should appreciate the efforts of ATSs and be mindful of the expectations placed on them. It is important for ATSs to have time to participate in activities outside the ATEP to find life balance. Athletic training educators should focus on interacting with students on a personal level while validating student membership by providing a supportive and exciting atmosphere to maximize student success. Finally, faculty and preceptors should act as professional role models and mentors while appropriately modeling athletic training careers.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Amy Orange for examining the interview questions; Jay Sedory, for pilot testing the interview questions; and Chris Bloom and Lauren Germain, for examining the coding scheme and verifying the final categories.

REFERENCES

- 1.Herzog VW. The Effect of Student Satisfaction on Freshman Retention in Undergraduate Athletic Training Education Programs [dissertation] Huntington, WV: Marshall University;; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mensch J, Mitchell M. Choosing a career in athletic training: exploring the perceptions of potential recruits. J Athl Train. 2008;43(1):70–79. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-43.1.70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lacey TA, Wright B. Occupational employment projections to 2018. Monthly Labor Review. 2009;132(11):82–123. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dodge TM, Mitchell MF, Mensch JM. Student retention in athletic training education programs. J Athl Train. 2009;44(2):197–207. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-44.2.197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Deil-Amen R. Socio-academic integrative moments: rethinking academic and social integration among two-year college students in career-related programs. J High Educ. 2011;82(1):54–91. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Heinerichs S, Gardiner-Shires A. An investigation into athletic training students perceptions of frustration during the clinical experience. Athl Train Educ J. 2011;6(1 suppl):S22. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Miller MG, Berry DC. An assessment of athletic training students' clinical-placement hours. J Athl Train. 2002;37(4 suppl):S229–S235. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Riter TS, Kaiser DA, Hopkins JT, Pennington TR, Chamberlain R, Eggett D. Presence of burnout in undergraduate athletic training students at one western US university. Athl Train Educ J. 2008;3(2):57–66. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stilger VG, Etzel EF, Lantz CD. Life-stress sources and symptoms of collegiate student athletic trainers over the course of an academic year. J Athl Train. 2001;36(4):401–407. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Higgins MJ. Defining Causes of Perceived Stress in Athletic Training Students Enrolled in CAATE Accredited Athletic Training Education Programs [dissertation] Minneapolis, MN: Capella University;; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pitney WA, Parker J. Qualitative inquiry in athletic training: principles, possibilities, and promises. J Athl Train. 2001;36(2):185–189. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.The Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching. The Carnegie Classification of Institutions of Higher Education. 2011. http://classifications.carnegiefoundation.org/. Accessed January 5.

- 13.Strauss AL, Corbin JM. Grounded theory methodology. In: Denzin NK, Lincoln YS, editors. Handbook of Qualitative Research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc.;; 1994. pp. 273–285. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pitney WA, Parker J. Qualitative research applications in athletic training. J Athl Train. 2002;37(4 suppl):S168–S173. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Strauss AL, Corbin JM. Basics of Qualitative Research: Grounded Theory Procedures and Techniques. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications, Inc.;; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Glaser BG, Strauss AL. The purpose and credibility of qualitative research. Nurs Res. 1966;15(1):56–61. doi: 10.1097/00006199-196601510-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Glaser BG, Strauss AL. The Discovery of Grounded Theory. Chicago, IL: Aldine;; 1967. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Commission on Accreditation of Athletic Training Education. Standards for the Academic Accreditation of Professional Athletic Training Programs. 2012. http://www.caate.net Accessed September 13, 2012.

- 19.Dodge TM, Walker SE, Laursen RM. Promoting coherence in athletic training education programs. Athl Train Educ J. 2009;4(2):46–51. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Herzog VW, Anderson D, Starkey C. Increasing freshman applications in the secondary admissions process. Athl Train Educ J. 2008;3(2):67–73. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rendon LI. Validating culturally diverse students: toward a new model of learning and student development. Innov High Educ. 1994;19(1):33–51. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bowman TG, Dodge TM. Factors of persistence among graduates of athletic training education programs. J Athl Train. 2011;46(6):665–71. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-46.6.665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pitney WA, Ehlers GG. A grounded theory study of the mentoring process involved with undergraduate athletic training students. J Athl Train. 2004;39(4):344–351. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Daloz LA. Effective Teaching and Mentoring: Realizing the Transformational Power of Adult Learning Experiences. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass;; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Racchini J. Enhancing student retention. Athl Ther Today. 2005;10(3):48–50. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Weidner TG, Henning JM. Historical perspective of athletic training clinical education. J Athl Train. 2002;37(4 suppl):S222–S228. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Neill KM, McCoy AK, Parry CB, Cohran J, Curtis JC, Ransom RB. The clinical experiences of novice nursing students. Nurse Educ. 1998;23(4):16–21. doi: 10.1097/00006223-199807000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sexton P, Levy LS, Willeford KS et al. Supervised autonomy. Athl Train Educ J. 2009;4(1):14–18. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Levy LS, Gardner G, Barnum MG et al. Situational supervision for athletic training clinical education. Athl Train Educ J. 2009;4(1):19–22. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Scriber K, Trowbridge C. Is direct supervision in clinical education for athletic training students always necessary to enhance student learning? Athl Train Educ J. 2009;4(1):32–37. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Monaco M, Martin M. The millennial student: a new generation of learners. Athl Train Educ J. 2007;2(2):42–46. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pitney WA, Mazerolle SA, Pagnotta KD. Work-family conflict among athletic trainers in the secondary school setting. J Athl Train. 2011;46(2):185–193. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-46.2.185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mazerolle SA, Pitney WA, Casa DJ, Pagnotta KD. Assessing strategies to manage work and life balance of athletic trainers working in the National Collegiate Athletic Association Division I setting. J Athl Train. 2011;46(2):194–205. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-46.2.194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.National Athletic Trainers' Association. Member statistics. www.nata.org Accessed September 24, 2011.