Abstract

Context

Injuries are a significant problem in the world of sports. Hope and social support are very important features in providing psychological help as people face life challenges such as sport injuries.

Objective

To examine how hope and social support uniquely and jointly predict postinjury rehabilitation beliefs, rehabilitation behavior, and subjective well-being.

Design

Cross-sectional study.

Setting

Four sports-injury rehabilitation centers of local universities in Taiwan.

Participants

A total of 224 injured Taiwanese collegiate student-athletes.

Main Outcomes Measure(s)

The Trait Hope Scale, the Sports Injury Rehabilitation Beliefs Survey, the Satisfaction with Life Scale, the Positive Affective and Negative Affective Scale, and the Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support were completed by participants after they received their regular rehabilitation treatment.

Results

We conducted hierarchical regressions and found that social support and 2 types of hope in injured athletes predicted their rehabilitation beliefs and subjective well-being. However, only hope agency predicted their rehabilitation behavior. Also, hope and social support had an interactive effect on the prediction of subjective well-being; for participants with low hope pathways, the perception of more social support was associated with higher levels of subjective well-being, whereas social support had only a relatively low association with subjective well-being among participants with high hope pathways.

Conclusions

Enhancing hope perceptions and strengthening injured athletes' social support during rehabilitation are beneficial to rehabilitation behavior and subjective well-being.

Key Words: athletic injuries, psychology, return to play

Key Points

-

•

Social support and both hope pathways and hope agency predicted rehabilitation beliefs and subjective well-being in injured athletes, but only hope agency predicted rehabilitation behavior.

-

•

For injured athletes with low hope pathways, more perceived social support was associated with greater subjective well-being. However, in those with high hope pathways, social support had only a small association with subjective well-being.

-

•

Hope and social support are psychological strengths that may be beneficial to an injured athlete's rehabilitation and subjective well-being.

Sports injuries are critical and challenging problems for athletes. Injuries may not only lead to decreased competitive performance but also impose long-term or permanent limitations upon athletes' independent functioning.1 Thus, complying with prescribed treatment plans becomes extremely important for injured athletes in order to reduce the effects of sports injuries and return to competition as quickly as possible.2 In their integrated model of psychological response to the sport-injury and rehabilitation process, Wiese-Bjornstal et al3 proposed that personal and situational factors continuously exert their effects on psychological responses and rehabilitation processes. Based on this model, we consider hope a personal factor and social support a situational factor in predicting injured athletes' thoughts, feelings, and behavior during the rehabilitation process.

Hope is conceptualized as an individual's traitlike cognitive perception that entails belief in his or her ability to reach desired goals.4,5 Researchers in the field of medicine and health psychology consider hope an important factor in helping people to persevere when they face challenges and threats, such as end-stage renal failure, chronic pain, traumatic physical disability, and sport injury.6–9 Important features of the hope model4,5 are the 2 components that shape one's hope perception: the ability to initiate and to maintain the actions necessary to reach a goal (ie, hope agency) and the positive belief that one is able to generate routes to goals (ie, hope pathways). In sport settings, empirical evidence10,11 showed that both agentic thinking and pathways to formulate one's hope perception are very important. Therefore, the association of hope with injured athletes' cognition, emotion, and behavior during rehabilitation is worthy of investigation.

In addition, social support is another important factor influencing injured athletes. Social support not only provides the resources needed to help individuals cope with the stress of injury but also provides a feeling of attachment to others.12,13 Researchers in sports medicine and sport psychology13–15 considered social support a buffering factor that mediates the stress-injury relationship. Multiple authors have demonstrated positive relationships between social support and treatment adherence and motivation,13 psychological functioning,16 greater life satisfaction,17 rehabilitation beliefs,18 and increased recovery rates of injured athletes.19

In addition to the antecedent variables (ie, personal factors and situational factors), 2 important outcome variables are worthy of further investigation: rehabilitation beliefs20 and subjective well-being.21 Originally derived from the framework of Protection Motivation Theory (PMT),22 rehabilitation beliefs represent an individual's cognitive appraisal as to whether rehabilitation programs can help injured athletes heal fully and return successfully to sport.20 We presume that, if individuals perceive a high threat and susceptibility to health problems and perceive treatment as effective and valued, their adherence to the treatment program will increase. Other studies23,24 also demonstrated that rehabilitation beliefs are related to adherence to the sport-injury rehabilitation program. However, only a few investigators18 examined the influence of injured athletes' perceptions of social support on their rehabilitation beliefs, and the association between hope and rehabilitation beliefs is still unknown.

Another outcome variable worthy of examination is subjective well-being,21 which is defined as an optimal state of human experience. Most of the previous research on injured athletes focused on rehabilitation-related outcome variables (eg, rehabilitation behaviors, treatment adherence and motivation, recovery rates). However, sport injury can endanger not only their sport experiences but also their mental health. When that happens, positive psychological strengths such as hope and social support may also help injured athletes to maintain a more optimistic and positive mental mindset.

Thus, based on the aforementioned studies, the model of Wiese-Bjornstal et al3 provides researchers with an insightful framework for understanding injured athletes. It is surprising that no authors have examined their suggestion3 that personal and situational factors interactively influence the thoughts and feelings of injured athletes. Therefore, the purpose of our investigation was to examine how hope and social support uniquely and jointly predict postinjury rehabilitation beliefs, rehabilitation behavior, and subjective well-being.

METHODS

Study Population

We recruited 232 collegiate student-athletes in Taiwan to participate. After preliminary data screening, a total of 224 participants (96.6%; age = 20.02 ± 1.47 years, Table 1) were included. All athletes reported sustaining at least 1 type of sport injury, and on average, 42 ± 53.37 days (range, 3–360 days) had elapsed between the injury and data collection. During the period of data collection, all were receiving rehabilitation treatment. Based on the length of time activity was restricted, 32 athletes described their injury as severe (greater than 3 weeks), 135 as moderate (1–3 weeks), and 57 as mild (less than 1 week).

Table 1.

Frequency Distribution of Injured Athletes' Demographics (N = 224)

| Characteristic |

n (%) |

| Sex | |

| Male | 104 (46.43) |

| Female | 120 (53.57) |

| Competitive level | |

| International | 112 (50.00) |

| National | 108 (48.21) |

| Intercollegiate | 4 (1.79) |

| Sport | |

| Track and field | 46 (20.54) |

| Basketball | 30 (13.39) |

| Volleyball | 30 (13.39) |

| Tae kwon do | 28 (12.5) |

| Chinese martial arts | 20 (8.93) |

| Judo | 13 (5.80) |

| Table tennis | 12 (5.36) |

| Other sportsa | 45 (20.09) |

| Duration of injury, db | |

| ≤30 | 127 (56.70) |

| 31 to 180 (approximate) | 91 (40.63) |

| ≥181 | 6 (2.68) |

| Perceived injury severity | |

| Severe | 32 (14.29) |

| Moderate | 135 (60.27) |

| Mild | 57 (25.45) |

| Location of injury | |

| Arm, shoulder, hand | 55 (24.55) |

| Waist, back | 30 (13.39) |

| Leg | 18 (8.04) |

| Ankle | 58 (25.89) |

| Knee | 35 (15.63) |

| Other injuries | 28 (12.50) |

Middle- to long-distance running, tai chi, soccer, tennis, dancing, rugby, weight lifting.

Days between injury and data collection.

Data-Collection Procedures

Official approval for this study was obtained from the university's institutional review board. The second author (Y.H.) contacted the rehabilitation center's supervisors and administrators personally to explain the research purpose and data-collection procedures. After gaining permission, the first author (F.J.H.L.) and several well-trained graduate students collected the data at 4 sport-injury rehabilitation centers of local universities in Taiwan. Potential participants were contacted individually by the investigators during or after their regular rehabilitation treatments and informed of the general research purpose and research procedure and assured of confidentiality. All who agreed to participate in the study signed a consent form first, and then during or after their rehabilitation treatments, they completed the questionnaires, which consisted of a demographic survey, the Trait Hope Scale (THS), the Sports Injury Rehabilitation Beliefs Survey (SIRBS), the Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS), the Positive Affective and Negative Affective Scale (PANAS), and the Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MSPSS). It took approximately 15 to 20 minutes to fill out these questionnaires, and all participants received a convenient store coupon (worth about $3.30) as a token of appreciation.

Measures

Demographic information collected consisted of sex, age, sport, years of competition, and competitive level. With regard to the injury, participants were asked to report the duration of injury, the location of injury, and their perceptions of injury severity (mild, moderate, or severe). Also, 1 question asked participants to rate their perceived rehabilitation compliance on a 10-point Likert scale (1 = did not follow the prescribed regimen at all, 10 = completely followed the prescribed regimen). This score represented the injured athlete's rehabilitation behavior.

Trait Hope Scale.

We used a Chinese version of the THS. The original THS, developed by Snyder et al,25 is a 12-item measure (including 4 spurious items) that assesses an individual's dispositional hope. Four items assess participants' perception of hope agency (eg, “I energetically pursue my goals”), and 4 items assess hope pathways (eg, “I can think of many ways to get out of a jam”) on an 8-point Likert scale (1 = definitely false to me, 8 = definitely true to me). We used the back-translation method to produce a revised version. Based on the results of exploratory factor analysis (EFA), we reduced the original 8 items to 5 items representing 2 subscales due to low factor loadings. The total variance was 58.23%, and the Cronbach α coefficient was 0.81 for hope pathways and 0.73 for hope agency, as indicated in Table 2.

Table 2.

Descriptive Data and Variable Intercorrelation Matrix

| 1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

9 |

10 |

11 |

12 |

13 |

14 |

15 |

|

| 1. Hope (pathways) | 0.81a | 0.59b | 0.31b | 0.15b | 0.19b | 0.30b | 0.25b | 0.34b | –0.12 | 0.32b | 0.19b | 0.33b | 0.18b | 0.33b | 0.26b |

| 2. Hope (agency) | 0.73 | 0.26b | 0.11 | 0.15b | 0.35b | 0.37b | 0.29b | 0.01 | 0.29b | 0.27b | 0.24b | 0.15b | 0.33b | 0.28b | |

| 3. Emotional support | 0.90 | 0.42b | 0.58b | 0.63b | 0.21b | 0.32b | –0.03 | 0.25b | 0.13 | 0.26b | 0.17b | 0.24b | 0.11 | ||

| 4. Informational support | 0.83 | 0.48b | 0.52b | 0.08 | 0.12 | 0.05 | 0.22b | 0.16b | 0.16b | 0.14b | 0.14b | 0.06 | |||

| 5. Tangible support | 0.81 | 0.47b | 0.19b | 0.31b | –0.04 | 0.29b | 0.15b | 0.19b | 0.19b | 0.14b | 0.19b | ||||

| 6. Respect support | 0.88 | 0.30b | 0.33b | –0.06 | 0.31b | 0.13b | 0.16b | 0.19b | 0.17b | 0.12 | |||||

| 7. Subjective well-being | 0.85 | 0.52b | –0.15b | 0.08 | 0.07 | –0.07 | 0.08 | 0.03 | 0.18b | ||||||

| 8. Positive affect | 0.81 | –0.19b | 0.16b | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.09 | 0.03 | 0.08 | |||||||

| 9. Negative affect | 0.78 | 0.08 | 0.14b | 0.10 | 0.02 | 0.01 | –0.05 | ||||||||

| 10. Susceptibility | 0.86 | 0.41b | 0.60b | 0.62b | 0.56b | 0.30b | |||||||||

| 11. Treatment efficacy | 0.81 | 0.45b | 0.31b | 0.46b | 0.16b | ||||||||||

| 12. Self-efficacy | 0.90 | 0.54b | 0.59b | 0.27b | |||||||||||

| 13. Rehabilitation value | 0.87 | 0.42b | 0.26b | ||||||||||||

| 14. Severity | ---- | 0.23b | |||||||||||||

| 15. Rehabilitation behavior | ---- | ||||||||||||||

| Mean | 6.29 | 6.29 | 3.07 | 3.05 | 2.79 | 3.15 | 3.73 | 3.95 | 3.20 | 5.19 | 5.47 | 5.75 | 5.04 | 5.96 | |

| SD | 0.96 | 1.07 | 0.57 | 0.67 | 0.69 | 0.55 | 0.89 | 0.89 | 0.88 | 0.93 | 1.06 | 0.95 | 1.25 | 1.03 |

Cronbach α for each subscale is found on the diagonal.

P < .05.

Sports Injury Rehabilitation Beliefs Survey

The SIRBS was developed by Taylor and May.20 It assesses an individual's appraisal of rehabilitation treatment after a sport injury. The original SIRBS has 19 items that measure 5 dimensions of rehabilitation beliefs pertaining to threat appraisal (susceptibility and severity) and coping appraisal (treatment efficacy, self-efficacy, and rehabilitation value). Participants indicated their perception about each item (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree). After the back-translation procedure, EFA, and item analysis, we retained 17 items, and the 5 factors that emerged were in line with a previous study20 and explained 63.84% of the variance. The Cronbach α coefficient ranged from 0.81 to 0.90.

Subjective Well-Being

Subjective well-being was assessed with the SWLS26 and the Chinese version of the PANAS.27 The SWLS is a 5-item measure assessing participants' overall evaluation of their lives. Participants indicate the extent to which they agree with each item (eg, “I am satisfied with my life”) on a 7-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree). Responses were summed, and higher scores indicated greater overall satisfaction with life. The Chinese version of the SWLS revealed a single factor structure, as Diener et al26 indicated, accounting for 56.48% of the variance, and the Cronbach α coefficient was 0.85.

The Chinese version of the PANAS27 assesses 4 positive affects (joyfulness, pleasantness, satisfaction, and pride) and 4 negative affects (fearfulness, anger, guilt, and sadness). Participants respond to all items by indicating the degree to which they are experiencing that affect at the present time on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = not at all, 5 = very strongly). The positive affect score is derived by averaging all 4 positive affects, and the negative affect score is derived by averaging all 4 negative affects. The EFA yielded 2 factors that accounted for 51.37% of the variance, and the Cronbach α coefficient was 0.81 for positive affects and 0.78 for negative affects.

Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support

To assess injured athletes' perceived social support, we adopted the Lan28 Chinese version of the Social Support Scale. The Lan scale was modified from Rees and Hardy's29 4-dimensional model of social support and assessed 4 aspects of social support: emotional, informational, tangible, and esteem. Participants responded to MSPSS measures by indicating on a 4-point Likert scale (1 = never, 4 = always) how often they received social support in each dimension from significant others when in difficult situations. The EFA was used to examine factorial structures, and 5 items were deleted from the original 26-item draft due to low factor loadings. Therefore, a 21-item MSPSS was used in the subsequent analysis. The Cronbach α coefficients ranged from 0.81 to 0.90.

Statistical Analyses

We used descriptive statistical analysis to examine the properties of the collected data. The results indicated acceptable skewness and kurtosis in all items: skewness ranged from 0.556 to −1.183, and kurtosis ranged from 1.440 to −1.084. Furthermore, we examined the effects of sex and injury severity on all variables. Men scored higher on hope pathways and hope agency than women did, and women perceived more emotional support than men did (Wilks λ = 0.862, F = 2.021, P = .016). Also, we found that moderately injured athletes' hope pathways were higher than those for severely injured athletes (Wilks λ = .748, F = 1.833, P = .006). For these reasons, we controlled for sex differences and injury severity on the subsequent hierarchical regression.

The correlations of all variables were analyzed with Pearson product moment correlations. It is worth pointing out that we treated predictors differently in this study. For social support, we used composite scores; however, hope scores were separated into hope pathways and hope agency for theoretical reasons. For criteria, we used composite scores for rehabilitation behavior (scoring 1 question as previously stated), subjective well-being (adding life satisfaction to positive affects and subtracting negative affects) and rehabilitation beliefs (average of scores on 5 subscales).

Next, we used hierarchical regression analysis to examine the unique and joint contributions of hope and social support to predicting injured athletes' rehabilitation behavior, subjective well-being, and rehabilitation beliefs. The control variables (sex and injury severity) were entered into the regression first. In the second and third steps, we examined the main effects of hope and social support on each major dependent variable. Finally, the full model with interaction effects of hope and social support (hope pathways × social support, hope agency × social support) was tested. Based on procedures recommended by Cohen et al,30 we graphed all significant interactions to show the relationship between social support and dependent variables using data of 1 standard deviation above and below the mean for hope pathways or hope agency.

RESULTS

Descriptive Statistics and Correlation Matrices

Descriptive statistics including the mean, standard deviation, Cronbach α, and correlation coefficients for all variables are shown in Table 2. Bivariate correlation analyses demonstrated that both types of hope correlated with all outcome variables except negative affect. Most social support components also correlated with all outcome variables except negative affect; however, only tangible social support correlated with rehabilitation behavior. Further, subjective well-being had no correlation with rehabilitation beliefs, whereas all rehabilitation belief components correlated with rehabilitation behavior. Finally, the Cronbach α coefficient for all measures ranged from 0.73 to 0.90, indicating acceptable reliability in our measures.

Hierarchical Regression Analysis

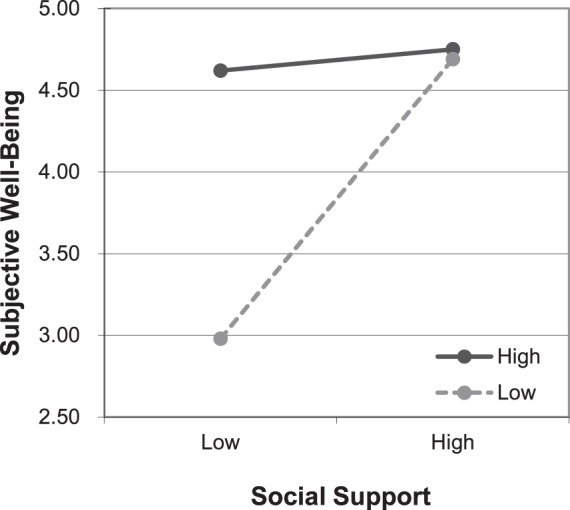

The predictive value of hope and social support on subjective well-being is illustrated in Table 3. The main effects of both types of hope and social support were significant. As hypothesized, the interaction between hope pathways and social support significantly predicted subjective well-being; the interaction uniquely accounted for 4% of the variance. Based on the findings of Cohen et al,30 our graph of the interaction (Figure) indicated that, for participants with low hope pathways (1 standard deviation below the mean), the perception of more social support was associated with higher levels of subjective well-being, whereas social support only had a relatively low association with subjective well-being in participants with high hope pathways (1 standard deviation above the mean). The full model accounted for 19.5% of subjective well-being. In terms of the predictive value of hope and social support on rehabilitation beliefs, the main effects of both types of hope and social support were significant and accounted for 15.3% of the variance. However, no interaction effect was found. Finally, we noted that only hope agency predicted rehabilitation behavior, and it accounted for 8.7% of the variance. No interaction effect was seen.

Table 3.

Hierarchical Regression Model of Subjective Well-Beinga (N = 224)

| Step 1 |

Step 2 |

Step 3 |

Step 4 |

|||||

| B |

β |

B |

β |

B |

β |

B |

β |

|

| Constant | 5.02b | 5.29b | 5.19b | 5.30b | ||||

| Sex | –0.14 | –0.03 | –0.46 | –0.11 | –0.39 | –0.10 | –0.37 | –0.09 |

| Injury severity | –0.23 | –0.07 | –0.29 | –0.09 | –0.26 | –0.08 | –0.27 | –0.09 |

| Hope pathways | 0.48b | 0.24 | 0.42b | 0.22 | 0.43b | 0.22 | ||

| Hope agency | 0.40b | 0.20 | 0.36b | 0.18 | 0.38b | 0.19 | ||

| Social support | 0.25b | 0.13 | 0.22 | 0.11 | ||||

| Hope path × social support | –0.43b | –0.22 | ||||||

| Hope agency × social support | 0.07 | 0.03 | ||||||

| R2 | 0.01 | 0.17 | 0.18 | 0.22 | ||||

| Adjusted R2 | 0.00 | 0.15 | 0.16 | 0.20 | ||||

| Changed in R2 | 0.16b | 0.01 | 0.04b | |||||

Dependent variable: subjective well-being.

P < .05.

Figure.

Relationship between subjective well-being and social support by hope pathway. For participants with high hope pathways (solid line), social support had a relatively small association with subjective well-being. For participants with low hope pathways (dotted line), the perception of more social support was associated with a higher level of subjective well-being.

DISCUSSION

Adopting the model of Wiese-Bjornstal et al3 as a research framework, we found that, consistent with our hypotheses, both types of hope and social support predicted injured athletes' subjective well-being and rehabilitation beliefs. Specifically, the interaction effect between hope pathways and social support significantly predicted subjective well-being and accounted for 4% of the unique variance in the main effects. However, only hope agency predicted rehabilitation behavior.

Previous researchers6–9 suggested that hope predicts psychological adjustment and the self-worth of ill individuals. Consistent with the extant literature, we found that hope also predicted rehabilitation behavior, subjective well-being, and rehabilitation beliefs in the context of sport injuries. Hope represents an individual's perception of reaching his or her desired goal. It is not surprising that greater perceived ability to reach the goal (hope agency) and stronger beliefs about finding routes to the goal (hope pathways) are positively associated with rehabilitation behavior, subjective well-being, and rehabilitation beliefs. Therefore, strategies that provide clear goals and protocols to pursue a successful recovery may enhance injured athletes' hope pathways and hope agency and, in turn, enhance their adherence.7,19 Also, as expected, our results showed that social support predicted injured athletes' subjective well-being and rehabilitation beliefs. Social support is an effective buffer between adverse life events and negative responses.13–15 Empirical research2,31 on mental toughness also noted the importance of social support as facilitating treatment adherence and motivation. Taken together, our findings support the notion that human psychological strengths, including hope and perceived social support, are critical for helping injured athletes.

Further, our finding that hope pathways and social support interactively affect subjective well-being provides a novel contribution to the sports-injury literature. The interaction effect indicates that, among participants with low hope pathways, the perception of more social support is associated with higher levels of subjective well-being. In contrast, among participants with high hope pathways, social support had only a relatively small influence on subjective well-being. Thus, for athletes with lower hope pathways, social support appears to provide essential assistance in facing life challenges such as injuries. In the area of athletic training, these findings have specific implications for practice and training. First, embedded in the theory and empirical evidence of hope, providing both hope pathways and hope agency for injured athletes is important in helping injured athletes. Education programs and workshops focusing on finding ways to reach their goals and remain mentally energized toward these goals may be included in injured athletes' rehabilitation regimens. Second, social support appears to have significant effects on injured athletes' well-being, especially those with lower hope pathways. An athlete's support network, such as family members, partners, peers, teammates, coaches, and other individuals close to an athlete, may become a source of strength.12,18 Athletic trainers play a key role in the prevention, recognition, management, and rehabilitation of injuries in athletes.13 This is the first examination of the interaction between hope and social support, and we used a composite score for social support. Further investigation into different types and sources of social support would better our understanding of injury-related phenomena and provide more specific plans for treatment.

Limitations and Suggestions

Although the present study provides preliminary evidence of the ability of hope and social support to predict injured athletes' rehabilitation behavior, subjective well-being, and rehabilitation beliefs, several limitations are worthy of further discussion. First, this study was cross-sectional in nature. The relationships of hope, social support, and injured athletes' rehabilitation behavior, subjective well-being, and rehabilitation beliefs do not imply a causal relationship. Further prospective or experimental studies are needed to confirm the effects. These studies may also provide more robust, theory-driven intervention strategies for those who work closely with injured athletes. Second, the participants in our study were mostly elite collegiate student-athletes, which may limit the generalizability of our results. The Taiwanese government has special systems to develop competitive sports at the college level. Elite collegiate student-athletes in Taiwan predominantly study at sport colleges and devote half their time to training. In addition, most of athletes in our study competed at a high level of sports (both nationally and internationally, see Table 1). These factors likely result in different levels of adherence to treatment regimens laid out by coaches and schools and may have influenced our ability to predict rehabilitation behaviors, subjective well-being, and rehabilitation beliefs.

Third, even though our measurement of social support has preliminary reliability and validity, it lacks cross-cultural validation. Because this is the first exploration of the interaction between hope and social support, we used a composite score for social support to simplify the analysis. However, different types of social support may have different influences. For instance, emotional support is crucial to an injured athlete shortly after injury, but over time, he or she may prefer more informational support. Further investigation of the different types of social support from varied resources (such as family members, peers, coaches, and so on) would better our understanding of injury-related phenomena and provide more specific suggestions for intervention. Similarly, while measuring rehabilitation behavior, we used only 1 question regarding participants' perception of their compliance with prescribed regimens. Future investigators should use objective measures such as the Sport Injury Rehabilitation Adherence Scale32 or rehabilitation records to increase the ecologic validity of rehabilitation behavior measurements. Finally, we used the model of Wiese-Bjornstal et al3 as a framework in the present study, but other insightful models demonstrate the psychosocial influences on injuries. For example, the Williams and Andersen14 multicomponent theoretical model of stress and injury was also used as a theoretical framework by many psychosocial injury researchers. In this model, social support was also regarded as a coping resource. Sequential links based on these theoretical models would be fruitful and warrant further investigation.

CONCLUSIONS

Injuries are an important concern in the world of sports. Many renowned athletes temporarily suspend their schedules because of injuries (eg, tennis super star Rafael Nadal stopped training for 10 days because of an adductor longus rupture) or withdraw forever from sport because of catastrophic injury. Therefore, coaches, athletes, administrators, athletic trainers, and related personnel must work together to prevent sport injuries and promote adherence to rehabilitation regimens after injuries. In keeping with current mainstream psychology that stresses the role of humans' strengths and merits in helping people face challenges, our findings suggest that hope and social support are psychological strengths that humans possess and may be beneficial to sport-injury rehabilitation and athletes' well-being.

REFERENCES

- 1.Tunick R, Clement D, Etzel E. College student-athletes and counseling services in the New Millennium. In: Etzel EF, editor. Counseling and Psychological Services for College Student-Athletes. Morgantown, WV: Fitness Information Inc;; 2009. pp. 403–450. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Levy AR, Polman RC, Clough PJ, McNaughton LR. Adherence to sport injury programmes: a conceptual review. Res Sports Med. 2006;14(2):149–162. doi: 10.1080/15438620600651132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wiese-Bjornstal DM, Smith AM, Shaffer SM, Morrey MA. An integrated model of response to sport injury: psychological and sociological dynamics. J Appl Sport Psychol. 1998;10(1):46–69. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Snyder CR. Hope theory: rainbows in mind. Psychol Inq. 2002;13(4):249–235. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Snyder CR, Lopez S. Handbook of Positive Psychology. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press;; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Billington E, Simpson J, Unwin J, Bray D, Giles D. Does hope predict adjustment to end-stage renal failure and consequent dialysis? Br J Health Psychol. 2008;13(pt 4):683–699. doi: 10.1348/135910707X248959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Snyder CR, Lehman KA, Kluck B, Monsson Y. Hope for rehabilitation and vice versa. Rehabil Psychol. 2006;51(2):89–112. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Elliot TR, Witty TE, Herrick SM, Hoffman JT. Negotiating reality after physical losses: hope, depression, and disability. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1991;61(4):608–613. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.61.4.608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kennedy P, Evans M, Sandhu N. Psychological adjustment to spinal cord injury: the contribution of coping, hope, and cognitive appraisals. Psychol Health Med. 2009;14(1):17–23. doi: 10.1080/13548500802001801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Curry LA, Snyder CR, Cook DL, Ruby BC, Rehm M. Role of hope in academic and sport achievement. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1997;73(6):1257–1267. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.73.6.1257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rolo C, Gould D. An intervention for fostering hope, athletic and academic performance in university student-athletes. Int Coach Psychol Review. 2007;2(1):44–61. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Williams RA, Appaneal RN. Sport psychology and counseling: social support and sport injury. Int J Athl Ther Train. 2010;15(4):xxx. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yang J, Peek-Asa C, Lowe JB, Heiden E, Foster DT. Social support patterns of collegiate athletes before and after injury. J Athl Train. 2010;45(4):372–379. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-45.4.372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Williams JM, Andersen MB. Psychosocial antecedents of sport injury: review and critique of the stress and injury model. J Appl Sport Psychol. 1998;10(1):5–25. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Petrie TA. The moderation effects of social support and plying status on the life stress-injury relationship. J Appl Sport Psychol. 1993;5(1):1–16. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Smith RE, Smoll FL, Ptacek JT. Conjunctive moderator variables in vulnerability and resiliency research: life stress, social support and coping skill, and adolescent sport injuries. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1990;58(2):360–370. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.58.2.360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Malinauskas R. The associations among social support, stress, life satisfaction as perceived by injured college athletes. Soc Behav Pers. 2010;38(6):741–752. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bone JB, Fry MD. The influence of injured athletes' perceptions of social support from ATCs on their beliefs about rehabilitation. J Sport Rehabil. 2006;15(2):156–167. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ievleva L, Orlick T. Mental links to enhance healing: an exploratory study. Sport Psychol. 1991;5(1):25–40. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Taylor AH, Threat May S. and coping appraisal as determinants of compliance with sports injury rehabilitation: an application of Protection Motivation Theory. J Sports Sci. 1996;14(6):471–482. doi: 10.1080/02640419608727734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Diener E. Social Indicator Research Series. Champaign, IL: Springer;; 2009. The science of well-being; pp. 11–58. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rippetoe PA, Rogers RW. Effects of components of protection motivation theory on adaptive and maladaptive coping with health threat. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1975;52(3):596–604. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.52.3.596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brewer BW. Adherence to sport injury rehabilitation regimens. In: Bull SJ, editor. Adherence Issues in Sport and Exercise. Chichester, UK: Wiley;; 2001. pp. 145–168. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Grindley EJ, Zizzi S, Nasypany AM. Use of protection motivation theory, affect, and barriers to understand and predict adherence to outpatient rehabilitation. Phys Ther. 2008;88(12):1592–1540. doi: 10.2522/ptj.20070076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Snyder CR, Irving L, Hope Anderson J. and health: measuring the will and the ways. In: Snyder CR, Forsyth DR, editors. Handbook of Social and Clinical Psychology. Elmsford, NY: Pergamon;; 1991. pp. 285–305. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Diener E, Emmons RA, Larson RJ, Griffin S. The Satisfaction with Life Scale. J Pers Assess. 1985;49(1):71–75. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa4901_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wu HC. The Study of Leisure Satisfaction and Subjective Well-Being: An Example of Taipei Metropolitan Area [dissertation] Taipei: National Taiwan Normal University;; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lan CM. A Study on the Relations Among Distress Disclosure, Non-Supportive Social Responses, Anxiety and Depression of College Students [dissertation] Taiwan: National Kaohsiung Normal University;; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rees T, Hardy L. An investigation of the social support experiences of high level sports performers. Sport Psychol. 2000;14(4):327–347. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cohen J, Cohen P, West SG, Aiken LS. Applied Multiple Regression/Correlation Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates;; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nicholls AR, Polman RCJ, Levy AR, Backhouse SH. Mental toughness, optimism, pessimism and coping among athletes. Pers Ind Diff. 2008;44(5):1182–1192. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brewer WB, Van Raalte JL, Petitpas AJ, et al. Preliminary psychometric evaluation of a measure of adherence to clinic-based sport injury rehabilitation. Phys Ther Sport. 2000;1(3):68–74. [Google Scholar]