Abstract

Wolbachia as an endosymbiont is widespread in insects and other arthropods and is best known for reproductive manipulations of the host. Recently, it has been shown that wMelpop and wMel strains of Wolbachia inhibit the replication of several RNA viruses, including dengue virus, and other vector-borne pathogens (e.g., Plasmodium and filarial nematodes) in mosquitoes, providing an alternative approach to limit the transmission of vector-borne pathogens. In this study, we tested the effect of Wolbachia on the replication of West Nile Virus (WNV). Surprisingly, accumulation of the genomic RNA of WNV for all three strains of WNV tested (New York 99, Kunjin, and New South Wales) was enhanced in Wolbachia-infected Aedes aegypti cells (Aag2). However, the amount of secreted virus was significantly reduced in the presence of Wolbachia. Intrathoracic injections showed that replication of WNV in A. aegypti mosquitoes infected with wMel strain of Wolbachia was not inhibited, whereas wMelPop strain of Wolbachia significantly reduced the replication of WNV in mosquitoes. Further, when wMelPop mosquitoes were orally fed with WNV, virus infection, transmission, and dissemination rates were very low in Wolbachia-free mosquitoes and were completely inhibited in the presence of Wolbachia. The results suggest that (i) despite the enhancement of viral genomic RNA replication in the Wolbachia-infected cell line the production of secreted virus was significantly inhibited, (ii) the antiviral effect in intrathoracically infected mosquitoes depends on the strain of Wolbachia, and (iii) replication of the virus in orally fed mosquitoes was completely inhibited in wMelPop strain of Wolbachia.

INTRODUCTION

Wolbachia pipientis is an intracellular endosymbiotic bacterium that has been reported from several groups of invertebrates. The bacteria are widespread in insects and are estimated to be present in ca. 65% of insect species (1). Wolbachia is mainly known for its effects on reproductive traits of hosts causing feminization, male-killing, and most commonly cytoplasmic incompatibility (CI) (2). Due to the induced CI effect, production of unviable progeny when an uninfected male mates with a Wolbachia-infected female, the endosymbiotic bacteria rapidly invade and spread within the host population (3). In addition to the manipulations of reproduction, recent reports have shown that certain strains of Wolbachia cause life-shortening and behavioral changes in the host (4, 5). Most importantly, Wolbachia infection also inhibits replication of RNA viruses (e.g., dengue virus [DENV], Chikungunya virus [CHIKV], Drosophila C virus) and other insect-transmitted pathogens (filarial nematode and Plasmodium) (6–9). This provided a breakthrough to utilize Wolbachia for the control of vector-borne diseases by targeting the vector. The introduction of wMel and wMelPop-CLA strains of Wolbachia into Aedes aegypti, which is the main vector of DENV, provided an opportunity to generate insects that do not support replication of the virus (10); hence, inhibiting transmission of the virus. wMel-infected A. aegypti mosquitoes have recently been released in the wild in Australia and shown to successfully invade and establish in two natural populations of the mosquitoes (11). However, the mechanism of inhibition of virus replication by Wolbachia is still unknown.

Flaviviruses are the most common insect-transmitted viruses (arboviruses) and include viruses such as dengue virus, West Nile virus, Japanese encephalitis virus, and yellow fever virus. We recently showed that a microRNA (miRNA) is encoded by the Kunjin strain of West Nile virus (WNVKUN), KUN-miR-1, from the terminal 3′ stem-loop (3′SL) located in the 3′UTR of the virus genome and that noncoding subgenomic flavivirus RNA (sfRNA) is likely to be the main source of KUN-miR-1 (12). miRNAs are small noncoding RNAs of ∼22 nucleotides that have been shown to play important roles in the regulation of gene expression and are involved in various biological processes such as development, cancer, and host-pathogen interactions. Interaction of miRNAs with target mRNAs leads either to the degradation of mRNA, the repression of translation, or in certain instances the upregulation of transcript levels (13, 14). KUN-miR-1 miRNA was found to be essential for virus replication as inhibition of the miRNA by a sequence-specific synthetic inhibitor RNA reduced replication of the virus (12). The target of KUN-miR-1 was determined to be the host GATA4 transcription factor, which is induced following virus infection. GATA4 induction was also shown to be essential for replication of WNVKUN since silencing of GATA4 by RNAi significantly reduced replication of the viral RNA.

In this study, we found that Wolbachia infection of mosquito cells enhances replication and accumulation of the genomic RNA (gRNA) of different WNV strains, i.e., highly pathogenic New York 99 (WNVNY99), nonpathogenic Kunjin MRM61C (WNVKUN), and a recently isolated virulent strain of Kunjin from a 2011 outbreak in horses in New South Wales (Australia) (WNVNSW2011) (15). Interestingly, we found that GATA4, which enhances WNV replication, is also upregulated in Wolbachia-infected cells which may have led to more efficient replication of the gRNA. However, titration of secreted virus showed that the amount of secreted virus was significantly reduced in the presence of Wolbachia, which is consistent with the previously published significant inhibition of DENV replication in Wolbachia-infected cells (8). In vivo experiments by intrathoracic injections showed that WNV replication was not inhibited in wMel-infected A. aegypti mosquitoes, but its replication was significantly reduced in wMelPop-infected mosquitoes. In contrast, oral feeding of A. aegypti mosquitoes showed that A. aegypti is confirmed to be a poor vector of WNV and that wMelPop completely inhibited infection of these mosquitoes with the virus.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mosquito cells and viral infection.

A. aegypti Aag2 cells and Wolbachia-infected Aag2 cells (aag2.wMelPop-CLA) were maintained in Schneider's medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Life Technologies) as monolayers (16). Cells were infected at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 1 with either wild-type or mutant WN viruses defective in the generation of sfRNA/miR-1 (12, 17). Three strains of WNV were used in the present study: New York 99 (WNVNY99), Kunjin MRM61C (WNVKUN), and Kunjin New South Wales (WNVNSW2011). Cells were also infected with DENV type 2 as described above. Virus titers in the supernatants of infected cells were determined by standard plaque assay on BHK cells.

Virus infection and transmission rates in mosquitoes.

PGYP1.OUT mosquitoes (designated as wMelPop) derived from A. aegypti stably transinfected with wMelPop-CLA strain of Wolbachia (4), and MGYP2.OUT mosquitoes (designated as wMel) derived from A. aegypti stably transinfected with wMel strain of Wolbachia (10) and their tetracycline-treated, Wolbachia-free but genetically identical mosquito lines (designated as Tet-cured). Insects were reared at 27°C with 70% relative humidity and a 12-h light regime. Larvae were maintained with fish food pellets (Tetra, Melle, Germany), and adults were offered 10% sucrose solution.

Female mosquitoes of 3 to 5 days old were intrathoracically inoculated with WNVNSW2011 virus stock [6.5 × 108 50% tissue culture infective dose(s) (TCID50)/ml], at a maximal volume of 69 nl per mosquito, using a Nanoject II Auto-Nanoliter injector (Drummond Scientific). The inoculated mosquitoes were kept at 27°C until sampling. Saliva and body samples were collected at 7 and 10 days postinoculation. The saliva was sampled by inserting the proboscis into a pipette tip loaded with 20 μl of fetal bovine serum (FBS) and allowing the mosquito to salivate for 45 min. The saliva samples and the body parts were stored at −80°C until testing.

The body and saliva samples were tested for the presence of WNVNSW2011 by cell culture–enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) (18) to determine infection and transmission rates, respectively. The body of each mosquito was homogenized in 500 μl of grinding media (RPMI 1640, supplemented with 2% FBS, 1% Pen-Strep, and 1% amphotericin B [Fungizone]), followed by centrifugation at 9,000 rpm for 5 min, at 4°C. The supernatant (100 μl/well) was used to inoculate C6/36 A. albopictus cell monolayers in duplicate for virus detection in 96-well tissue culture plates. The saliva samples were each mixed with 50 μl of grinding media, and the entire mixture was inoculated onto a C6/36 monolayer. Five days after inoculation, WNVNSW2011 in the monolayers was detected by a flavivirus specific monoclonal antibody 4G4 (19). The positive body samples were subjected to titration for WNVNSW2011 load by cell culture-ELISA (18).

For oral feeding, +Wol and −Wol A. aegypti mosquitoes were fed with sheep blood containing 107.05 TCID50 of WNVKUN/ml. The mosquitoes were collected at 4, 7, and 10 days postfeeding, and infection, disseminated infection, and transmission rates were determined as described above.

qRT-PCR.

GATA4 transcript levels were determined by quantitative reverse transcription-PCR (qRT-PCR) using specific primers to GATA4 (forward, 5′-GGGACCGATTCTACGTATG-3′; reverse, 5′-CGTAGAATGTTCAATCTGC-3′). To analyze virus RNA replication with qRT-PCR, specific primers to the genomic RNA (gRNA) in the capsid gene region were used (for WNVKUN and WNVNSW2011, forward [5′-GCGAGCTGTTTCTTAGCACGA-3′] and reverse [5′-CCGTGAACCTAAAAAACGCC-3′]; for WNVNY99, forward [5′-GCGGCGGCAATATTCATG-3′] and reverse [5′-ACGTTGTAGGCAAAGGGCAA-3′]). RPS17 was used as a normalizing reference. The PCR conditions were 50°C for 2 min, 95°C for 2 min, followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 15 s, 60°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 15 s, followed in turn by the melting curve (68 to 95°C). In all of the qPCRs, SYBR Premix Ex Taq II (TaKaRa), which utilizes SYBR green, was used. The Student t test was used to compare differences in means between different treatments. Fold changes in gRNA and GATA4 were calculated first by normalizing data against RPS17 cellular gene, followed by normalizing data against mock or control treatment.

RESULTS

Wolbachia infection induces expression of GATA4 in mosquito cells.

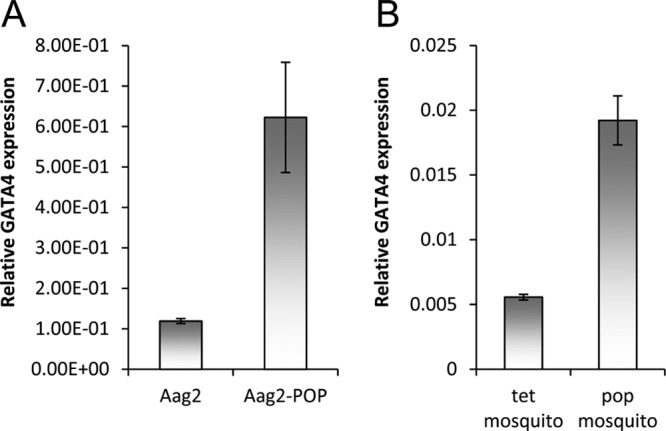

Following our investigations into differential expression of mosquito host miRNAs and mRNAs upon Wolbachia wMelPop-CLA infection, the expression of GATA4 (GenBank accession number XM_001654324) was significantly increased in A. aegypti Aag2 cells infected with wMelPop-CLA (aag2.wMelPop-CLA) compared to noninfected Aag2 cells (Fig. 1A; P < 0.05). To find out whether GATA4 is also upregulated in A. aegypti mosquitoes infected with wMelPop-CLA (+Wol), we tested +Wol mosquitoes and those without Wolbachia (−Wol) by qRT-PCR. The results confirmed that GATA4 is also upregulated in +Wol mosquitoes (Fig. 1B; P < 0.001).

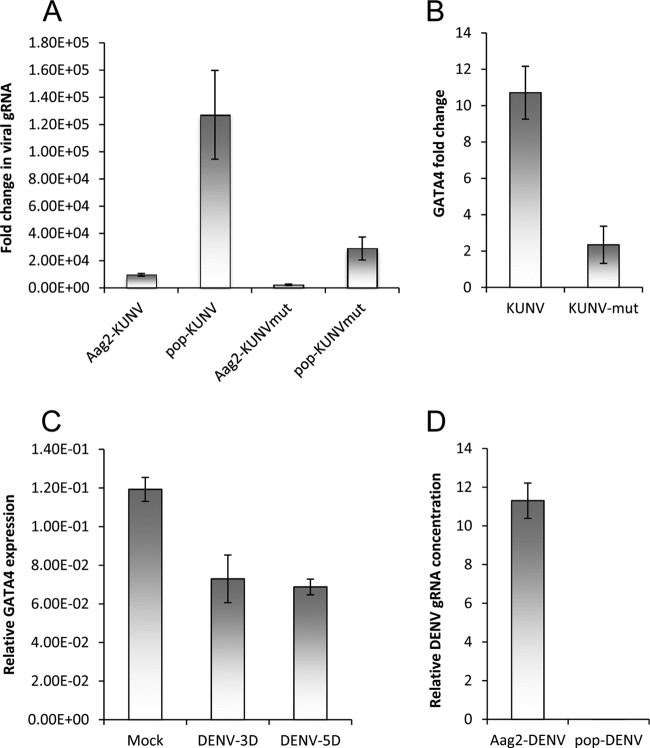

Fig 1.

Wolbachia wMelPop-CLA induces GATA4 transcript levels both in vitro and in vivo. (A) qRT-PCR analysis of RNA from Aag2 and aag2.wMelPop-CLA cells (Aag2-pop) using specific primers to GATA4. (B) qRT-PCR analysis of A. aegypti mosquitoes without (tet; treated with tetracycline) and with wMelPop-CLA (pop). Error bars indicate standard deviations of averages from two biological and three technical replicates.

Wolbachia infection enhances WNV gRNA replication in mosquito cell line but inhibits virus assembly and/or secretion.

Previous studies have shown that Wolbachia infection inhibits replication of a variety of RNA viruses (6–9). Since we recently showed that KUN-miR-1 encoded by WNV upregulates GATA4 transcript levels which in turn enhances replication of WNVKUN (12), we investigated replication of the virus in Wolbachia-infected Aag2 cells, considering that they have increased levels of GATA4 expression (Fig. 1A). When cells were analyzed 72 h after WNVKUN infection by qRT-PCR using specific primers to the capsid-coding region of viral genomic RNA, we found 13-fold more virus RNA replication in aag2.wMelPop-CLA cells compared to Aag2 cells (Fig. 2A; compare Aag2-KUNV and pop-KUNV; P < 0.0001). A mutant of WNVKUN (IRAΔCS3) that produces significantly less KUN-miR-1 replicated poorly (4-fold less RNA) in Aag2 cells in comparison to the wild-type virus (12, 17) (see also Fig. 2A, compare Aag2-KUNVmut and Aag2-KUNV; P < 0.0001). Interestingly, we found that the RNA of this mutant virus replicated more efficiently (12-fold more) in aag2.wMelPop-CLA cells compared to Aag2 cells (Fig. 2A; compare Aag2-KUNVmut and pop-KUNVmut; P < 0.0001). In addition, qRT-PCR results confirmed that the wild-type WNVKUN induced GATA4 transcription significantly higher than the mutant virus in Aag2 cells (Fig. 2B; P < 0.0001). This further confirmed that GATA4 induced by KUN-miR-1 and/or by Wolbachia infection enhances WNVKUN gRNA replication.

Fig 2.

Viral gRNA and GATA4 levels in WNVKUN and DENV-infected Aag2 cells. (A) Fold changes of WNVKUN and mutant (KUNVmut) WNVKUN gRNA in Aag2 and aag2.wMelPop-CLA cells (pop) 3 days after infection analyzed by qRT-PCR using specific primers to the viral capsid protein gene. (B) Fold changes of GATA4 transcripts in Aag2 cells infected with WNVKUN for 3 days and its mutant (KUNVmut) analyzed by qRT-PCR. (C) Fold changes of GATA4 transcripts in aag2.wMelPop-CLA cells either mock-infected or infected with DENV at 3 (3D) and 5 (5D) days postinfection. (D) Relative gRNA levels of DENV in Aag2 and aag2.wMelPop-CLA cells 5 days postinfection. Error bars indicate the standard deviations of averages from two biological and three technical replicates.

To find out whether another flavivirus, DENV, also induces expression of GATA4, we infected Aag2 cells with DENV (type 2) and analyzed total RNA extracted from cells at 3 and 5 days after infection. Interestingly, we found that in contrast to WNV infection, GATA4 transcription was reduced in DENV-infected cells (Fig. 2C; P < 0.05). Although the 3′SL from which KUN-miR-1 is processed is conserved among flaviviruses (17), the miRNA sequence is different between WNV and DENV. Even if a miRNA is produced from DENV 3′SL, it would not have sufficient complementarity with the sequence targeted by KUN-miR-1 in the GATA4 mRNA. We also confirmed that under our experimental conditions Wolbachia inhibits DENV gRNA replication in aag2.wMelPop-CLA cells compared to Aag2 cells (Fig. 2D), which is consistent with previous findings (8).

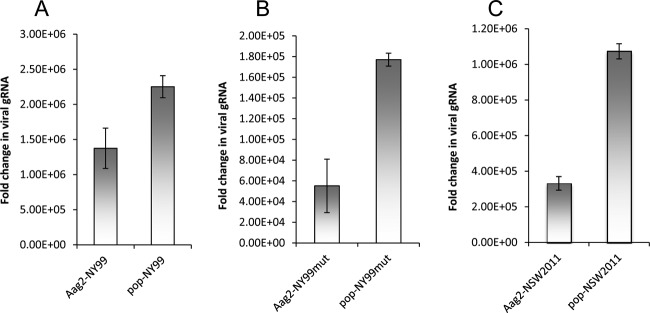

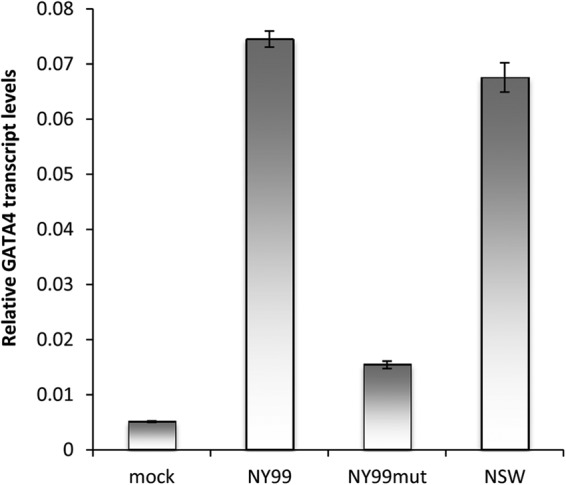

The virulent WNVNY99 strain has 98% amino acid sequence identity with the nonpathogenic WNVKUN strain (20). Since its emergence in the United States in 1999 and until 2010, ∼1.8 million people have been infected, with ∼360,000 illnesses, close to 13,000 reported cases of encephalitis, and 1,308 deaths (21). We examined WNVNY99 replication in Aag2 and aag2.wMelPop-CLA cells by qRT-PCR and verified that significantly more viral gRNA was produced in aag2.wMelPop-CLA cells compared to Aag2 cells (Fig. 3A; P = 0.0007). In addition, significantly more viral gRNA was produced in aag2.wMelPop-CLA cells compared to Aag2 cells infected with a WNVNY99 IRAΔCS3 mutant defective in sfRNA production (NY99mut, will be described elsewhere) (Fig. 3B; P = 0.0003). A more virulent strain of WNVKUN was recently isolated from a 2011 outbreak in horses in New South Wales, Australia (WNVNSW2011) that has 99% amino acid sequence identity to WNVKUN (15). We also confirmed that significantly more WNVNSW2011 gRNA was produced in aag2.wMelPop-CLA cells compared to Aag2 cells (Fig. 3C; P < 0.0001). Subsequently, we also confirmed that GATA4 expression is significantly upregulated in both WNVNY99- and WNVNSW2011-infected cells (Fig. 4; P < 0.0001). However, significantly less GATA4 was produced in Aag2 cells infected with a NY99mut (defective in sfRNA production, therefore defective in KUN-miR-1 homolog production) (Fig. 4; P < 0.0001). Overall, these results clearly demonstrate that GATA4 is induced by all WNV strains (KUN, NY99, and NSW2011) examined. It is therefore likely that Wolbachia infection enhances replication of the WNV gRNA by having significantly upregulated levels of GATA4 prior to infection.

Fig 3.

WNVNY99 and WNVNSW2011 RNA replicates and accumulates more efficiently in wMelPop-infected cells. (A) qRT-PCR analysis of RNA from Aag2 and aag2.wMelPop-CLA (pop) cells infected with WNVNY99. (B) qRT-PCR analysis of RNA from Aag2 and aag2.wMelPop-CLA (pop) cells infected with a WNVNY99 mutant (NY99mut) defective in production of sfRNA. (C) qRT-PCR analysis of RNA from Aag2 and aag2.wMelPop-CLA (pop) cells infected with WNVNSW2011. Specific primers to the viral capsid protein were used. Cells were collected 3 days after infection. Error bars indicate the standard deviations of averages from two biological and three technical replicates.

Fig 4.

WNVNY99 and WNVNSW2011 both induce GATA4 transcription. Aag2 cells were infected with WNVNY99 (NY99), WNVNY99 mutant (NY99mut), and WNVNSW2011 (NSW2011) for 3 days, and their extracted RNAs were analyzed by qRT-PCR using specific primers to their capsid protein genes. Error bars indicate the standard deviations of averages from two biological and three technical replicates.

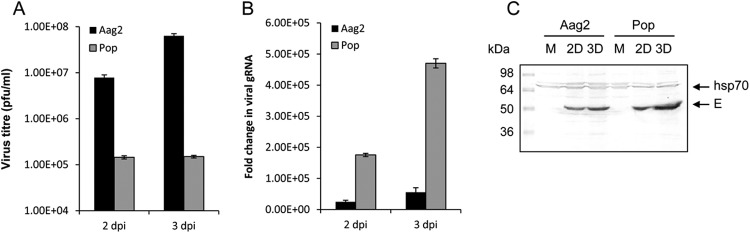

Since WNV gRNA replication was enhanced in Wolbachia-infected cells, we explored if this translates into more virus production in the culture medium of aag2.wMelPop-CLA cells. Aag2 and aag2.wMelPop-CLA cells were infected with WNVKUN and subsequently cells and media were collected from the cells at days 2 and 3 postinfection. Interestingly, plaque assays revealed that significantly fewer virus particles were produced in the culture medium of aag2.wMelPop-CLA cells compared to Aag2 cells (Fig. 5A; P < 0.0001). This experiment with three biological replicates was independently repeated twice with reproducible results. When RNA extracted from cells from the same experiment was analyzed by qRT-PCR, significantly more viral gRNA was found in aag2.wMelPop-CLA cells compared to Aag2 cells (Fig. 5B; P < 0.0001), a finding consistent with the results shown above. In addition, Western blot analysis of cells from the same experiment using antibodies to the WNV protein E revealed that more viral protein was produced in aag2.wMelPop-CLA cells at 3 days postinfection compared to Aag2 cells (Fig. 5C). This suggested that although viral gRNA replication and protein production is enhanced in Wolbachia-infected cells, virus assembly and/or secretion is conversely inhibited in the presence of Wolbachia.

Fig 5.

Wolbachia enhances WNV RNA accumulation but inhibits virus assembly/secretion in wMelPop-infected cells. (A) Plaque assay of media collected from Aag2 and aag2.wMelPop-CLA cells (Pop) infected with WNVKUN at 2 and 3 days postinfection. Error bars indicate standard deviations of averages from three biological replicates. (B) qRT-PCR analysis of RNA extracted from cells in panel A using specific primers to the viral capsid protein. Error bars indicate the standard deviations of averages from three biological and three technical replicates. (C) Western blot analysis of cells from panel A probed with antibodies to the WNV E protein (E arrow) and hsp70 as a loading control. Each lane is a mixture of cells from three biological replicates.

Effect of Wolbachia infection on WNV replication in mosquitoes.

Previous studies (8, 10), and the confirmation shown in Fig. 2D, have shown that Wolbachia inhibits replication of DENV in A. aegypti cells and mosquitoes. Consistent with these, we demonstrated that Wolbachia inhibits the production of secreted WNV in aag2.wMelPop-CLA cells. To investigate the effect of Wolbachia on WNV replication in mosquitoes, A. aegypti mosquitoes infected with wMel or wMelPop strains of Wolbachia were intrathoracically injected with WNVNSW2011. Subsequently, the rates of infection and dissemination were determined in injected mosquitoes (Table 1). Virus titers were determined in the saliva and body samples by cell culture-ELISA using a monoclonal antibody to 4G4 (α-nonstructural protein 1). The infection rate of WNV in wMel mosquitoes was 100% in both +Wol and −Wol mosquitoes (Table 1). Transmission rate was also 49 and 66% at 7 and 10 days after inoculation, respectively (Table 1). In contrast, the transmission rate for DENV in wMel-infected A. aegypti mosquito lines MGYP2 and MGYP2.OUT were reported as 4.2% and 0%, respectively (10). This suggested that wMel does not have the same inhibitory effect on WNV as on DENV. However, in wMelPop mosquitoes, inhibition of WNV infection was observed as the infection rate was determined to be 42 and 50% at 7 and 10 days after infection, respectively, compared to 100% in −Wol mosquitoes at both days (Table 1). In wMelPop mosquitoes, transmission rates for WNV were determined to be 0% for both 7 and 10 days after inoculation (Table 1).

Table 1.

WNV body infection rate and transmission rate following intrathoracic inoculation in A. aegypti mosquitoesa

| Time point (days) | Status | Body |

Saliva |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total no. of samples | No. of positive samples | IR (%) | Total no. of samples | No. of positive samples | TR (%) | ||

| 7 | Tet-cured | 43 | 43 | 100 | 43 | 43 | 100 |

| wMel | 37 | 37 | 100 | 37 | 18 | 49 | |

| 10 | Tet-cured | 39 | 39 | 100 | 39 | 39 | 100 |

| wMel | 35 | 35 | 100 | 35 | 23 | 66 | |

| 7 | Tet-cured | 29 | 29 | 100 | 29 | 24 | 82.8 |

| wMelPop | 26 | 11 | 42 | 26 | 0 | 0 | |

| 10 | Tet-cured | 26 | 26 | 100 | 26 | 24 | 92.3 |

| wMelPop | 26 | 13 | 50 | 26 | 0 | 0 | |

IR, infection rate; TR, transmission rate.

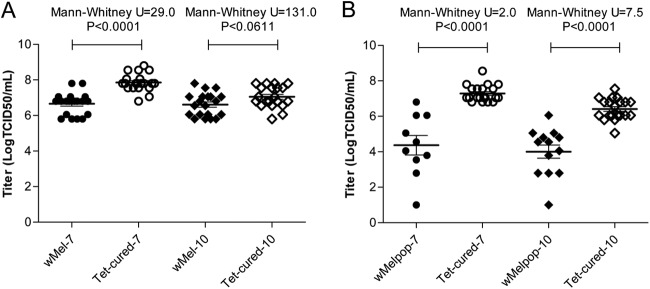

When virus loads were determined in wMel and wMelPop mosquitoes injected with WNVNSW2011, significantly lower viral loads were detected in wMel mosquitoes at 7 days after inoculation compared to −Wol mosquitoes (Fig. 6A; P < 0.0001). However, at 10 days after inoculation there was no significant difference between +Wol and −Wol mosquitoes (Fig. 6A; P = 0.0611). In wMel DENV-infected mosquitoes, virus levels were strikingly lower (1,500-fold fewer) than that of −Wol mosquitoes at 14 days postinoculation (10). This demonstrated that the wMel strain of Wolbachia does not inhibit WNV replication in mosquitoes when they are injected intrathoracically with the virus. However, in wMelPop mosquitoes significantly lower WNV loads were detected both 7 and 10 days after inoculation compared to −Wol mosquitoes (Fig. 6B; P < 0.0001).

Fig 6.

Virus titers in WNVNSW2011-positive A. aegypti mosquitoes. The first 20 positive body samples from each group of mosquitoes collected at 7 and 10 days after viral inoculation were selected for determining virus titers by ELISA using monoclonal antibody against NS1 protein, 4G4. (A and B) Virus titer in wMel and Tet-cured mosquitoes (A) and wMelPop and Tet-cured mosquitoes (B) at 7 and 10 days after WNVNSW2011 inoculations.

To mimic the natural route of mosquito infection, A. aegypti +Wol (wMelPop) and −Wol mosquitoes were orally fed with WNVKUN. Compared to intrathoracic inoculation (Table 1), the infection, disseminated infection and transmission rates were substantially lower in −Wol mosquitoes (Table 2), which confirms that A. aegypti has a very poor vector competency for WNV (22–24) and that the gut provides a strong barrier against WNV infection. In +Wol mosquitoes, the infection, disseminated infection and transmission rates were all negligible (Table 2).

Table 2.

WNV body infection rate, disseminated infection rate, and transmission rate following oral feeding in A. aegypti mosquitoes

| Mosquito line | % Infected (no. infected) at indicated day after oral feedinga |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Day 4 |

Day 7 |

Day 10 |

|||||||

| IR | DIR | TR | IR | DIR | TR | IR | DIR | TR | |

| wMelPop | 0 (40) | 0 (40) | 0 (40) | 0 (40) | 0 (40) | 0 (40) | 0 (40) | 0 (40) | 0 (40) |

| Tet-cured | 21.9 (41) | 4.8 (41) | 0 (41) | 7.5 (40) | 5 (40) | 0 (40) | 15 (40) | 12.5 (40) | 2.5 (40) |

IR, infection rate; DIR, disseminated infection rate; TR, transmission rate.

DISCUSSION

Vector-borne viruses, mostly belonging to the family Flaviviridae, cause significant number of mortalities/morbidities around the world. Among mosquito-borne flaviviruses, DENV and WNV account for ∼50 million of cases per year worldwide (21, 25). In regard to both viruses, control options for the diseases caused by the viruses are limited, and there are no effective vaccines available for either. Therefore, control measures have concentrated on reducing the vector populations. With the development of resistance to chemical pesticides in mosquitoes, environmental contaminations caused by chemicals and public awareness, alternative approaches to chemical control to reduce mosquito vector populations or limit transmission of viruses are of immense importance. Wolbachia as a widespread endosymbiont of insects have provided promise in disease control by reducing the life span of mosquito vectors (4) and most importantly by inhibiting replication of arboviruses such DENV and CHIKV in mosquitoes (8). Recently, a wMel-infected population of A. aegypti was tested under controlled field conditions and was shown to block DENV transmission in the mosquito, providing an approach to inhibit DENV spread (10).

In the present study, we showed that Wolbachia enhances replication of WNV gRNA and protein production in an A. aegypti cell line (Aag2) infected with wMelPop but inhibits virus assembly and/or secretion, with the latter being consistent with published data for other arboviruses, such as DENV and CHIKV (26). We also showed that three different strains of WNV (NY99, KUNV, and NSW2011) had enhanced gRNA replication and accumulation in aag2.wMelPop-CLA cells. In contrast, under the same conditions, DENV gRNA replication and accumulation was significantly inhibited in aag2.wMelPop-CLA cells. This suggests that Wolbachia may inhibit WNV and DENV production by different mechanisms. Although Wolbachia clearly inhibits DENV viral gRNA replication and consequently virus production, the effect of Wolbachia on WNV infection appears to occur at the later stages of infection, interfering either with viral RNA packaging or with virion assembly or virus secretion from infected cells. This interesting observation clearly requires further investigations.

At 7 and 10 days after intrathoracic injection of WNVNSW2011 in A. aegypti, differences in virus loads were greater in wMelPop compared to wMel-infected mosquitoes in relation to uninfected mosquitoes, but the difference at 10 days after infection in wMel mosquitoes was not significant. The wMel strain is known to have more specific tissue tropisms than wMelPop, and our processing of whole bodies rather than legs could lead to masking of interference by Wolbachia due to the presence of both positive and negative tissues in the body samples. This is a plausible explanation considering that the antiviral protection of Wolbachia has been shown to strongly correlate with the density and the tissue tropism of Wolbachia (27, 28). In wMelPop mosquitoes, however, WNV replication was inhibited. Consistently, wMelPop inhibited WNV infection of A. aegypti mosquitoes when they were orally fed, although the infection rate of the mosquitoes was substantially lower in orally fed mosquitoes (15%) compared to intrathoracically inoculated mosquitoes (100%). Inhibition of WNV replication in Drosophila melanogaster flies and Culex quinquefasciatus mosquitoes harboring native Wolbachia endosymbionts was also shown previously (26).

Furthermore, we showed that induction of the transcription factor GATA4 by Wolbachia is likely to be the mechanism of the enhancement of WNV gRNA replication. We previously showed that a WNVKUN virus-encoded miRNA, KUN-miR-1, upregulates the expression of GATA4 upon infection of Aag2 cells (12). In the present study, we showed that the more virulent strains WNWNY99 and WNVNSW2011, which are closely related to WNVKUN, also induce the expression of GATA4. We hypothesize that increased expression of GATA4 mRNA directly increases GATA4 protein levels. Therefore, considering that Wolbachia-infected mosquito cells overexpress GATA4, it would make this protein readily available to the virus from the moment it enters the host. This may give WNV an advantage to establish RNA replication compared to cells without Wolbachia. Notably, GATA4 expression decreases in DENV-infected cells, suggesting that DENV gRNA replication may not require GATA4. In animals, GATA transcription factors are ubiquitous and play important roles in various biological processes such as development, differentiation, and innate immunity (29). They all share one or two zinc finger DNA binding domains with the conserved CX2CX17CX2C motifs (30). In A. aegypti, members of the GATA family have been shown to regulate egg development by repressing or activating genes involved in the process. GATA4, specifically, is expressed after a blood meal and acts as a transcriptional activator of vitellogenin (vg), which is an important protein in vitellogenesis and egg development (31). In addition, GATA4 in conjunction with NF-κB transcription factors were found to be required for induction of lipophorin receptor gene involved in A. aegypti systemic immune responses and lipid metabolism (32). In insects, lipophorin is the main lipid carrier protein transporting lipids to various tissues and is also involved in immune responses (32, 33). It is not clear at this stage how upregulation of GATA4 by KUN-miR-1 or Wolbachia may facilitate WNV gRNA replication in mosquito cells, and this requires further investigation.

In conclusion, we have shown that the wMelPop strain of Wolbachia enhances replication of WNV gRNA in vitro, whereas it inhibits replication of DENV gRNA. However, similar to DENV infection, production of secreted WNV virions was inhibited by Wolbachia. In addition, in wMel-carrying A. aegypti mosquitoes, replication of the WNV (NSW2011 strain) was not inhibited when injected intrathoracically with the virus. In wMelPop-carrying mosquitoes, however, WNV replication was inhibited both when inoculated intrathoracically and when orally fed with WNV. The enhancement of replication of the WNV gRNA in Wolbachia-infected A. aegypti cells appears to correlate with the upregulation of GATA4, which had been shown to facilitate replication of the virus gRNA (12). A. aegypti is not considered the primary vector of WNVs, but the virus has the potential to infect and be disseminated by this mosquito (22–24). Infection and dissemination rates of up to 86%, respectively, were reported for A. aegypti infected with WNV (24). In our study, we found very low infection rates of A. aegypti (15%) when mosquitoes free of Wolbachia were orally fed with WNV, and this rate was nil in Wolbachia-infected mosquitoes. In this context, these results suggest that the Wolbachia-infected A. aegypti mosquitoes released in the field to control the transmission of DENV (10) are not likely to pose a threat in enhancing replication of various strains of WNV. Further studies should direct toward the mechanism(s) by which GATA4 in Wolbachia- or WNV-infected cells is induced and how does induction of the transcription factor facilitates replication of the virus gRNA. In addition, the mechanism by which WNV RNA packaging and/or virion assembly/secretion is inhibited concurrently with the enhancement of viral RNA replication and accumulation merits further investigation.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by grants to S.A. and A.A.K. from the Australian Research Council (DP110102112) and the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia (APP1027110) and to B.H.K. from the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia (496601).

We thank Jon Darbro for technical support, Scott O'Neill (Monash University, Australia) for supplying Wolbachia-infected and tetracycline-cured lines from the Eliminate Dengue Program administered by the Foundation for the National Institutes of Health, and Peter Kirkland from the Elizabeth Macarthur Agriculture Institute in Australia for providing the WNVNSW2011 isolate.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 31 October 2012

REFERENCES

- 1. Hilgenboecker K, Hammerstein P, Schlattmann P, Telschow A, Werren JH. 2008. How many species are infected with Wolbachia?: a statistical analysis of current data. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 218:215–220 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Tram U, Fredrick K, Werren JH, Sullivan W. 2006. Paternal chromosome segregation during the first mitotic division determines cytoplasmic incompatibility phenotype. J. Cell Sci. 119:3655–3663 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hoffman AA, Turelli M. 1997. Cytoplasmic incompatibility in insects, p 42–80 In O'Neill SL, Hoffman AA, Werren JH. (ed), Influential passengers: inherited microorganisms and arthropod reproduction. Oxford University Press, Oxford, England [Google Scholar]

- 4. McMeniman CJ, Lane RV, Cass BN, Fong AWC, Sidhu M, Wang Y-F, O'Neill SL. 2009. Stable introduction of a life-shortening Wolbachia infection into the mosquito Aedes aegypti. Science 323:141–144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Moreira LA, Saig E, Turley AP, Ribeiro JMC, O'Neill SL, McGraw EA. 2009. Human probing behavior of Aedes aegypti when infected with a life-shortening strain of Wolbachia. PLoS Neg. Trop. Dis. 3:6 doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0000568 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hedges LM, Brownlie JC, O'Neill SL, Johnson KN. 2008. Wolbachia and virus protection in insects. Science 322:702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kambris Z, Cook PE, Phuc HK, Sinkins SP. 2009. Immune activation by life-shortening Wolbachia and reduced filarial competence in mosquitoes. Science 326:134–136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Moreira LA, Iturbe-Ormaetxe I, Jeffery JA, Lu GJ, Pyke AT, Hedges LM, Rocha BC, Hall-Mendelin S, Day A, Riegler M, Hugo LE, Johnson KN, Kay BH, McGraw EA, van den Hurk AF, Ryan PA, O'Neill SL. 2009. A Wolbachia symbiont in Aedes aegypti limits infection with Dengue, Chikungunya, and Plasmodium. Cell 139:1268–1278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Teixeira L, Ferreira A, Ashburner M. 2008. The bacterial symbiont Wolbachia induces resistance to RNA viral infections in Drosophila melanogaster. PLoS Biol. 6:2753–2763 doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.1000002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Walker T, Johnson PH, Moreira LA, Iturbe-Ormaetxe I, Frentiu FD, McMeniman CJ, Leong YS, Dong Y, Axford J, Kriesner P, Lloyd AL, Ritchie SA, O'Neill SL, Hoffman AA. 2011. The wMel Wolbachia strain blocks dengue and invades caged Aedes aegypti populations. Nature 476:450–453 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hoffmann AA, Montgomery BL, Popovici I, Iturbe-Ormaetxe I, Johnson PH, Muzzi F, Greenfield M, Durkan M, Leong YS, Dong Y, Cook H, Axford J, Callahan AG, Kenny N, Omodei C, McGraw EA, Ryan PA, Ritchie SA, Turelli M, O'Neill SL. 2011. Successful establishment of Wolbachia in Aedes populations to suppress dengue transmission. Nature 476:454–457 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hussain M, Torres S, Schnettler E, Funk A, Grundhoff A, Pijlman GP, Khromykh AA, Asgari S. 2012. West Nile virus encodes a microRNA-like small RNA in the 3′ untranslated region which upregulates GATA4 mRNA and facilitates virus replication in mosquito cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 40:2210–2223 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bartel DP. 2009. MicroRNAs: target recognition and regulatory functions. Cell 23:215–233 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lytle JR, Yario TA, Steitz JA. 2007. Target mRNAs are repressed as efficiently by microRNA-binding sites in the 5′ UTR as in the 3′ UTR. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 104:9667–9672 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Frost MJ, Zhang J, Edmonds JH, Prow NA, Gu X, Davis R, Hornitzky C, Arzey KE, Finlaison D, Hick P, Read A, Hobson-Peters J, May FJ, Doggett SL, Haniotis J, Russell RC, Hall RA, Khromykh AA, Kirkland PD. 2012. Characterization of virulent West Nile virus Kunjin strain, Australia, 2011. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 18:792–800 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hussain M, Frentiu FD, Moreira LA, O'Neill SL, Asgari S. 2011. Wolbachia utilizes host microRNAs to manipulate host gene expression and facilitate colonization of the dengue vector Aedes aegypti. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 108:9250–9255 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Pijlman GP, Funk A, Kondratieva N, Leung J, van der AA L, Liu W, Palmenberg AC, Hall RA, Khromykh AA. 2008. A highly structured, nuclease-resistant noncoding RNA produced by flaviviruses is required for pathogenicity. Cell Host Microbe 4:579–591 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Broom AK, Hall RA, Johansen CA, Oliveira N, Howard MA, Lindsay MD, Kay BH, Mackenzie JS. 1998. Identification of Australian arboviruses in inoculated cell cultures using monoclonal antibodies in ELISA. Pathology 30:286–288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Clark DC, Lobigs M, Lee E, Howard MJ, Clark K, Blitvich BJ, Hall RA. 2007. In situ reactions of monoclonal antibodies with a viable mutant of Murray Valley encephalitis virus reveal an absence of dimeric NS1 protein. J. Gen. Virol. 88:1175–1183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Audsley M, Edmonds J, Liu W, Mokhonov V, Mokhonova E, Melian EB. 2011. Virulence determinants between New York 99 and Kunjin strains of West Nile virus. Virology 414:63–73 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kilpatrick AM. 2011. Globalization, land use, and the invasion of West Nile virus. Science 334:323–327 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Higgs S, Snow K, Gould EA. 2004. The potential for West Nile virus to establish outside of its natural range: a consideration of potential mosquito vectors in the United Kingdom. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 98:82–87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Turell MJ, O'Guinn ML, Dohm DJ, Jones AW. 2001. Vector competence of North American mosquitoes (Diptera: Culicidae) for West Nile virus. J. Med. Entomol. 38:130–134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Vanlandingham DL, McGee CE, Klinger KA, Vessey N, Fredregillo C, Higgs S. 2007. Relative susceptibilities of South Texas mosquitoes to infection with West Nile virus. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 77:925–928 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kyle JL, Harris E. 2008. Global spread and persistence of dengue. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 62:71–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Glaser RL, Meola MA. 2010. The native Wolbachia endosymbionts of Drosophila melanogaster and Culex quinquefasciatus increase host resistance to West Nile virus infection. PLoS One 5:e11977 doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0011977 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Lu P, Bian G, Pan X, Xi Z. 2012. Wolbachia induces density-dependent inhibition to dengue virus in mosquito cells. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 6:e1754 doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0001754 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Osborne SE, Iturbe-Ormaetxe I, Brownlie JC, O'Neill SL, Johnson KN. 2012. Antiviral protection and the importance of Wolbachia density and tissue tropism in Drosophila. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 78:6922–6929 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Shapira M, Hamlin BJ, Rong J, Chen K, Ronen M, Tan MW. 2006. A conserved role for a GATA transcription factor in regulating epithelial innate immune responses. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 103:14086–14091 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Lowry JA, Atchley WR. 2000. Molecular evolution of the GATA family of transcription factors: conservation within the DNA-binding domain. J. Mol. Evol. 50:103–105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Park JH, Attardo GM, Hansen IA, Raikhel AS. 2006. GATA factor translation is the final downstream step in the amino acid/target-of-rapamycin-mediated vitellogenin gene expression in the an autogenous mosquito Aedes aegypti. J. Biol. Chem. 281:11167–11176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Cheon HM, Shin SW, Bian G, Park JH, Raikhel AS. 2006. Regulation of lipid metabolism genes, lipid carrier protein lipophorin, and its receptor during immune challenge in the mosquito Aedes aegypti. J. Biol. Chem. 281:8426–8435 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ma G, Hay D, Li D, Asgari S, Schmidt O. 2006. Recognition and inactivation of LPS by lipophorin particles. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 30:619–626 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]