Abstract

Porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus (PRRSV) is one of the most important viral pathogens in the swine industry. Emerging evidence indicates that the host microRNAs (miRNAs) are involved in host-pathogen interactions. However, whether host miRNAs can target PRRSV and be used to inhibit PRRSV infection has not been reported. Recently, microRNA 181 (miR-181) has been identified as a positive regulator of immune response, and here we report that miR-181 can directly impair PRRSV infection. Our results showed that delivered miR-181 mimics can strongly inhibit PRRSV replication in vitro through specifically binding to a highly (over 96%) conserved region in the downstream of open reading frame 4 (ORF4) of the viral genomic RNA. The inhibition of PRRSV replication was specific and dose dependent. In PRRSV-infected Marc-145 cells, the viral mRNAs could compete with miR-181-targeted sequence in luciferase vector to interact with miR-181 and result in less inhibition of luciferase activity, further demonstrating the specific interactions between miR-181 and PRRSV RNAs. As expected, miR-181 and other potential PRRSV-targeting miRNAs (such as miR-206) are expressed much more abundantly in minimally permissive cells or tissues than in highly permissive cells or tissues. Importantly, highly pathogenic PRRSV (HP-PRRSV) strain-infected pigs treated with miR-181 mimics showed substantially decreased viral loads in blood and relief from PRRSV-induced fever compared to negative-control (NC)-treated controls. These results indicate the important role of host miRNAs in modulating PRRSV infection and viral pathogenesis and also support the idea that host miRNAs could be useful for RNA interference (RNAi)-mediated antiviral therapeutic strategies.

INTRODUCTION

Porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus (PRRSV) is one of the most economically important viral pathogens in pigs, leading to significant economic losses in the swine industry worldwide. PRRS is characterized by severe reproductive failure in sows and respiratory syndromes and persistent infection in young pigs. Atypical PRRS is characterized by high fever, high morbidity, and high mortality in pigs of all ages and emerged in China in 2006. The causative agent was confirmed to be a highly pathogenic PRRSV (HP-PRRSV) with a discontinuous deletion of 30 amino acids in nonstructural protein 2 (NSP2) (1). PRRSV is classified within the family Arteriviridae, order Nidovirales. It has a single-stranded, 5′-capped positive-sense RNA genome of approximately 15.4 kb, containing at least 9 opening reading frames (ORFs) (1, 2).

MicroRNAs (miRNAs), which can be produced by hosts or viruses, are a class of small noncoding RNAs that can inhibit gene expression through base-pairing interactions between the loaded miRNA and its mRNA target. Recent studies have reported that cellular miRNAs can target viral RNAs during infections, resulting in inhibition of virus replication as a new antiviral defense (3–8) or a new pathway to alter the virus life cycle (9–11), whereas virus-derived miRNAs could regulate the viral life cycle by targeting viral genes (12, 13) or host genes (14) and escape host immunity by targeting cellular genes (15, 16). Surprisingly, miR-122, a liver-specific miRNA, facilitates hepatitis C virus (HCV) replication by binding to the 5′ untranslated region (UTR) of the viral genomic RNA (gRNA) (17). Likewise, miRNAs such as miR-155 and miR-326 are also involved in innate and adaptive immune systems (18, 19). Meanwhile, RNA interference (RNAi)-based therapies have been widely studied for treating fatal disorders or virus infection (20). However, most studies of viral infection in vivo have been based on exogenous small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) (21–27) rather than host miRNAs except one case in which host miR-122 was confirmed as a target for HCV treatment by therapeutic silencing of endogenous miR-122 in HCV-infected primates (28). Whether host miRNAs can target PRRSV RNA and be used as a therapeutic tool against virus infection has not been characterized.

Transcription of PRRSV genomic RNA can produce a full-length genomic mRNA and at least 6 subgenomic mRNAs (sgRNAs) (29), and the viral genomic RNA has a long UTR in the downstream of ORF1ab. Thus, we hypothesize that the long UTR might provide targets for host miRNAs. In this study, we investigated the function of miRNAs in inhibition of PRRSV infection in cell culture and then expanded our work to an animal model for molecular therapy. Our data demonstrated that miR-181 effectively inhibited PRRSV replication by targeting viral genomic RNA in vitro and in vivo. These data suggest that host miRNAs might play an important role in modulating PRRSV infections and viral pathogenesis and might be useful in RNAi-mediated antiviral therapeutic strategies.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells, tissues, and viruses.

HeLa and (PRRSV-permissive) Marc-145 cells were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and penicillin-streptomycin. Porcine alveolar macrophages (PAMs) were obtained by lung lavage of 8-week-old specific-pathogen-free (SPF) pigs and maintained in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% FBS and penicillin-streptomycin. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were isolated from SPF pigs by Ficoll-Paque (Sigma) density gradient centrifugation according to the manufacturer's instructions. Microglias were obtained as previously described (30). Peritoneal macrophages were obtained by lavage of the peritoneal cavity of SPF pigs. Tissues were collected from HP-PRRSV strain JXwn06-infected 4-week-old pigs.

Two type 2 PRRSV strains were used to infect PAMs or Marc-145 cells: CH-1a and JXwn06. CH-1a was the first strain isolated in China (GenBank accession no. AY032626), and JXwn06 is an HP-PRRSV strain (GenBank accession no. EF641008.1) isolated from a pig farm with an atypical PRRS outbreak in Jiangxi Province, China, in 2006 (31). Viruses were propagated in PAMs or Marc-145 cells.

For analysis of PRRSV growth, supernatants from cell cultures were collected at different time points after virus inoculation, and viral titers were determined by an microtitration infectivity assay and expressed as 50% tissue culture infective doses (TCID50s) as previously described (27).

Deep sequencing.

Deep sequencing was performed by LC Sciences (Houston, TX) on PAMs inoculated with a mock dose or with PRRSV CH-1a at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 1 for 24 h. Briefly, 10 μg total RNA for each sample was used to construct the small RNA libraries. RNA fragments 15 to 50 nucleotides (nt) in length were isolated by the use of a denaturing PAGE gel and quantified following gel elution and ethanol precipitation. The Sequence Read Archive (SRA) adapters (Illumina) were ligated to small RNAs, and reverse transcription (RT) was performed using Moloney murine leukemia virus (MMLV) (Invitrogen) with RT primers recommended by Illumina. The cDNA was amplified with pfx DNA polymerase (Invitrogen) in 20 cycles of PCR using Illumina's small RNA primers selecting for ∼80- to 115-bp products on a 12% Tris-borate-EDTA (TBE) PAGE gel. This fraction was eluted, and the recovered cDNAs were precipitated and quantified on a NanoDrop instrument (Thermo Scientific) and on a TBS-380 minifluorometer (Turner Biosystems) using PicoGreen double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) quantization reagent (Invitrogen). The concentration of the sample was adjusted to 10 nM, and a total of 10 μl was sequenced on an Illumina GAIIx system following the vendor's instructions. Raw sequencing data were filtered for composition, the presence of adaptor dimers, length, sequence repetition, and copy numbers. The filtered data were then mapped to the known miRNAs of all organisms listed in the current miRBase (http://www.mirbase.org) and Sus scrofa genome. miRNAs sequenced for over 100 counts in either sample are listed in data set 1.

miRNA target prediction and conservation analysis.

miRNA targets in PRRSV JXwn06 or CH-1a RNA were predicted by RegRNA (32) (http://regrna.mbc.nctu.edu.tw/index.php) or ViTa (33) (http://vita.mbc.nctu.edu.tw/). Since many experimental or computational approaches have shown that the UTR is the preferred location of miRNA target sites (34), we kept the targets restricted to only the long UTR (∼3.4 kb) of the genomic RNA and excluded the targets located only in the coding region. For conservation analysis, we aligned targeting sequences in 171 virus strains, including 158 genotype 2 strains and 13 genotype 1 strains collected from GenBank (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/GenBank), using MEGA 5 software (35).

miRNA mimics.

Mimics for miRNA were synthesized by Genepharma. miRNA mimics are double-stranded RNA oligonucleotides modified by 2′-O-methyl with sequence complementary to the mature miRNA annotated in miRBase. For miR-181 mimics, the sense sequences are as follows: for miR-181a (181a), 5′-AACAUUCAACGCUGUCGGUGAGUU-3′; for miR-181b (181b), 5′-AACAUUCAUUGCUGUCGGUGGGUU-3′; for miR-181c (181c), 5′-AACAUUCAACCUGUCGGUGAGU-3′; and for miR-181d (181d), 5′-AACAUUCAUUGUUGUCGGUGGGUU-3′.

For miR-181 mutants, the corresponding non-seed-mutated miR-181a mimic (L1U, L9U, and L1L9U) or seed-mutated miR-181 family mimic (a-m, b-m, c-m, and d-m) sense sequences are as follows (underlined letters are mutated bases): for L1U, 5′-UACAUUCAACGCUGUCGGUGAGUU-3′; for L9U, 5′-AACAUUCAUCGCUGUCGGUGAGUU-3′; for L1L9U, 5′-UACAUUCAUCGCUGUCGGUGAGUU-3′; for a-m, 5′-AUGUAUCAACGCUGUCGGUGAGUU-3′; for b-m, 5′-AUGUAUCAUUGCUGUCGGUGGGUU-3′; for c-m, 5′-AUGUAUCAACCUGUCGGUGAGU-3′; and for d-m, 5′-AUGUAUCAUUGUUGUCGGUGGGUU-3′. The negative-control (NC) mimic sequence is as follows: 5′-UUC UCCGAACGUGUCACGUTT-3′.

Transfection of miRNA mimic and viral infections.

All the miRNA or NC mimics were transfected into PAMs or Marc-145 cells at a concentration of 60 nM (except for the dose-dependent experiments) using HiPerfect transfection reagents (Qiagen). Twenty-four hours after transfection, cells were infected with PRRSV JXwn06 or CH-1a at an MOI of 0.05 except for analysis of viral growth experiments.

RNA isolation and qPCR.

Total RNA and microRNA were extracted with TRIzol (Invitrogen) following the manufacturer's instructions. MMLV reverse transcriptase was used for reverse transcription according to the manufacturer's protocol (Promega). Quantitative RT-PCR (qPCR) analysis was performed using a ViiA 7 real-time PCR system (Applied Biosystems) and a FastSYBR mixture (CoWin Biotech Co., Ltd. [CWBIO]). For detection of endogenous miRNAs, 1 μg of total RNA was polyadenylated and reverse transcribed as previously described (36) using a universal adapter primer (5′-GCGAGCACAGAATTAATACGACTCACTATAGGTTTTTTTTTTTTVN-3′). The obtained 40-μl cDNA was then diluted in RNase-free water (1:20), and 9 μl of the diluted cDNA was amplified using a FastSYBR mixture (CWBIO) with a miRNA-specific forward primer and the Uni-miR-Reverse primer 5′-GCGAGCACAGAATTAATACGACTCAC-3′. For detection of 2′-O-methyl-modified miR-181, total RNA was directly reverse transcribed with the specific primer 5′-GCGAGCACAGAATTAATACGACTCACTATAGGCGTACTCACCGACA-3′ and was then amplified using a FastSYBR mixture (CWBIO) with a miR-181-specific forward primer (5′-GCGAGCACAGAAAACATTCAACC-3′) and the universal primer. Relative expression was analyzed using the ΔΔCt method (37), and U6 RNA was set up as an endogenous control. The absolute quantity was calculated by calibration to a synthetic RNA standard (Genepharma) of known concentrations. Estimation of the total cumulative expression of 13 miRNAs was calculated by addition of the absolute quantity of each miRNA. The levels of ORF7 RNA, alpha interferon (IFN-α), IFN-β, and tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) mRNA were quantified using a FastSYBR mixture (CWBIO). For quantitative analysis of genomic and subgenomic mRNAs, primers used for qPCR were designed (see Table 1) as previously described (38). All the forward primers were the same because genomic and subgenomic mRNAs share the same leader sequence and the PCR replicon was designed to be smaller than 250 bp. Relative expression levels were analyzed using the ΔΔCt method (37), and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) mRNA was set up for use as an endogenous control. All PCR experiments were done in triplicate. Other primers are listed in Table 2.

Table 1.

Quantitative RT-PCR primers for genomic and subgenomic mRNAs

| Primer | Sequence (5′→3′) | Position in the genome (bp) (JXwn06) |

|---|---|---|

| Common forward primer | AGGGGTCTGTCCCTAACACCTTG | 123–145 |

| gRNA reverse primer | CACCCTGGCATTGGGGGTACA | 237–217 |

| sgRNA2 reverse primer | AAATTCCGTGAAAGCATCCACAAA | 12053–12030 |

| sgRNA3 reverse primer | TGCAACGGAGGAAAATATGGAGGA | 12648–12625 |

| sgRNA4 reverse primer | AACCAACCAAGAGGAAAAGAAAGG | 13184–13161 |

| sgRNA5 reverse primer | CAGCACGCGGTCAAGCACTTCC | 13726–13705 |

| sgRNA6 reverse primer | GCTGTGCTATCATTGCAGAAGTC | 14325–14303 |

| sgRNA7 reverse primer | TGCTGCTTGCCGTTGTTATTTGG | 14824–14802 |

Table 2.

Quantitative RT-PCR primers for host genes

| Target | Forward primer (5′→3′) | Reverse primer (5′→3′) |

|---|---|---|

| GAPDH | CCTTCCGTGTCCCTACTGCCAAC | GACGCCTGCTTCACCACCTTCT |

| ORF7 | AATAACAACGGCAAGCAGCA | GCACAGTATGATGCGTCGGC |

| TNF-α | ACCACGCTCTTCTGCCTACTGC | TCCCTCGGCTTTGACATTGGCTAC |

| IFN-β | AGCACTGGCTGGAATGAAACCG | CTCCAGGTCATCCATCTGCCCA |

| IFN-α | CTGCTGCCTGGAATGAGAGCC | TGACACAGGCTTCCAGGTCCC |

| U6 snRNA | CTCGCTTCGGCAGCACA | AACGCTTCACGAATTTGCGT |

| miR-181a | CGGAACATTCAACGCTGTCGGT | GCGAGCACAGAATTAATACGACTCAC |

| miR-181b | CGGAACATTCATTGCTGTCGGT | GCGAGCACAGAATTAATACGACTCAC |

| miR-181c | CGGAACATTCAACCTGTCGGT | GCGAGCACAGAATTAATACGACTCAC |

| miR-181d | CGGAACATTCATTGTTGTCGGT | GCGAGCACAGAATTAATACGACTCAC |

| miR-21 | CGGTAGCTTATCAGACTGATGTTGA | GCGAGCACAGAATTAATACGACTCAC |

| miR-206 | TGGAATGTAAGGAAGTGTGTGA | GCGAGCACAGAATTAATACGACTCAC |

| miR-106a | AAAAGTGCTTACAGTGCAGGTAG | GCGAGCACAGAATTAATACGACTCAC |

| miR-128 | TCACAGTGAACCGGTCTCT | GCGAGCACAGAATTAATACGACTCAC |

| miR-130a | CAGTGCAATGTTAAAAGGGCAT | GCGAGCACAGAATTAATACGACTCAC |

| miR-140-3p | TACCACAGGGTAGAACCACGGA | GCGAGCACAGAATTAATACGACTCAC |

| miR-18 | TAAGGTGCATCTAGTGCAGATA | GCGAGCACAGAATTAATACGACTCAC |

| miR-188-5p | CATCCCTTGCATGGTGGAGGGT | GCGAGCACAGAATTAATACGACTCAC |

| miR-299-5p | ATGGTTTACCGTCCCACATAC | GCGAGCACAGAATTAATACGACTCAC |

| miR-301a | CAGTGCAATAGTATTGTCAAAGC | GCGAGCACAGAATTAATACGACTCAC |

| miR-30-5p | TGTAAACATCCTCGACTGGAAG | GCGAGCACAGAATTAATACGACTCAC |

| miR-338 | TCCAGCATCAGTGATTTTGTTG | GCGAGCACAGAATTAATACGACTCAC |

| miR-93 | CAAAGTGCTGTTCGTGCAGGTAG | GCGAGCACAGAATTAATACGACTCAC |

IFA.

For detection of PRRSV in PAMs, an immunofluorescence assay (IFA) was performed on PAMs transfected with miR-181 family or mutant mimics and subsequently infected with PRRSV JXwn06 at an MOI of 0.05 for 36 h. The cells were fixed with cold methanol-acetone (1:1) for 10 min at 4 °C, washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) three times, and then blocked with 10% goat serum–PBS for 30 min at room temperature. Cells were then incubated with monoclonal antibodies (MAbs) (SDOW17; Rural Technologies) against PRRSV nucleocapsid protein at 37 °C for 1 h. After being washed with PBS three times, cells were incubated with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG antibody at 37°C for 1 h and then washed with PBS. Slides were mounted using a solution of 50% glycerol–PBS. Cells were then examined by fluorescence microscopy.

Construction of pGL3 target luciferase reporters.

For generation of a miR-181 target luciferase reporter wild-type (WT) construct (pGL3-Target-WT), a 340-bp genomic fragment (bp 13527 to 13866) containing the miR-181 target locus was isolated from PRRSV JXwn06 genomic RNA by RT-PCR amplification with high-fidelity PrimeSTAR HS DNA Polymerase from TaKaRa, using forward (5′-GCTCTAGACTGTGTGCGTCAACTTTACCA-3′) and reverse (5′-GCTCTAGACCAGCCAATCTGTGCCATTC-3′) primers. The resulting PCR product was then subcloned into the XbaI site downstream of the luciferase gene in the pGL3-control vector (Promega). To generate a miR-181 target-mutated reporter construct (pGL3-Target-Mut), mutations at positions corresponding to the miR-181 seed region were introduced using a site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene) according to the manufacturer's instructions and the following primers (underlined letters are mutated bases): forward, 5′-CCATCCTACTGGCAATTTGATACATCAAGTATGTTGGGGAAGTGC-3′; and reverse, 5′-GCACTTCCCCAACATACTTGATGTATCAAATTGCCAGTAGGATGG-3′. Briefly, mutant plasmids were generated by PCR using 15 ng of the parent vector as the template under the following conditions: 95°C for 1 min, followed by 20 cycles of 95°C for 30 s, 55°C for 1 min, and 68°C for 10 min. The resulting mixture was digested with 1 μl of Dpn-1 for 1 h at 37°C in order to remove the parental DNA. The remaining DNA was used to transform DH5α (TaKaRa), and a number of colonies were obtained. Mutant plasmids were confirmed by sequencing.

Cell transfection and luciferase reporter assays.

HeLa cells were cotransfected with a mixture of luciferase reporter plasmids, pRL-TK renilla luciferase plasmids, and miR-181 mimics (a mixture of four miR-181 members) or miR-181-Mut mimics (a mixture of four seed-mutated miR-181 members) using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). For competitively binding experiments, Marc-145 cells were inoculated with PRRSV at an MOI of 0.1 or 1 for 3 h and then cotransfected with a mixture of luciferase reporter plasmids, pRL-TK renilla luciferase plasmids, and miR-181 mimics or miR-181-Mut mimics. Thirty-six hours later, cells were lysed and the firefly and Renilla luciferase activities were measured using a dual luciferase reporter assay system (Promega) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The transfection efficiency was normalized by division of the firefly luciferase activity value by the renilla luciferase activity value.

Western blot analysis and RISC immunoprecipitation assay.

For detection of PRRSV nucleocapsid (N) protein or pig Ago2 protein, PAM lysates were produced using radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) lysis buffer supplemented with protease and phosphatase inhibitors. Protein concentrations of the extracts were measured with a bicinchoninic acid (BCA) assay (Beyotime). Equal amounts of the samples were loaded and subjected to SDS-PAGE, transferred onto polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membranes, and then blotted as previously described (39). An RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC) immunoprecipitation assay was performed as previously described (40). Briefly, PAMs were plated in 10-cm-diameter culture plates (1 × 107 cells/plate) 24 h before transfections. Cells were transfected with NC mimics or miR-181c mimics using HiPerfect reagents (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer's instructions and subsequently infected with PRRSV JXwn06 for 36 h. Mouse anti-Ago2 monoclonal antibody (clone 2E12-1C9; Abnova) was used for detection of pig Ago2 protein in input cell lysates.

Animal experiments with miRNA delivery.

All animal studies were performed according to protocols approved by the animal welfare committee of China Agricultural University. NC mimics or miR-181c mimics (2.5 mg/kg of body weight per dose) mixed with D5W solution (23) in a final volume of 2 ml were administered to 4-week-old SPF pigs through intranasal instillation (n = 3 for the control group; n = 4 for the miR-181c group), and 5 h later, pigs were inoculated intranasally with 1.5 ml of PRRSV JXwn06 (105.2 TCID50/ml), mimicking the natural route of PRRSV infection. At day 5 post-PRRSV infection, second deliveries of NC mimics or miR-181c mimics were performed using the same dose and route as the first time. The rectal temperature of each pig was monitored daily until it died. Viral load was detected at 3, 7, 10, 14, and 21 days postinfection (dpi) in blood samples from each pig by qPCR. We confirmed that all pigs were negative for the presence of PRRSV before virus challenge.

Statistical analysis.

The appropriate statistical analyses were used and are presented in each figure legend. A P value of less than 0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

MiR-181 family members had strong activity against PRRSV.

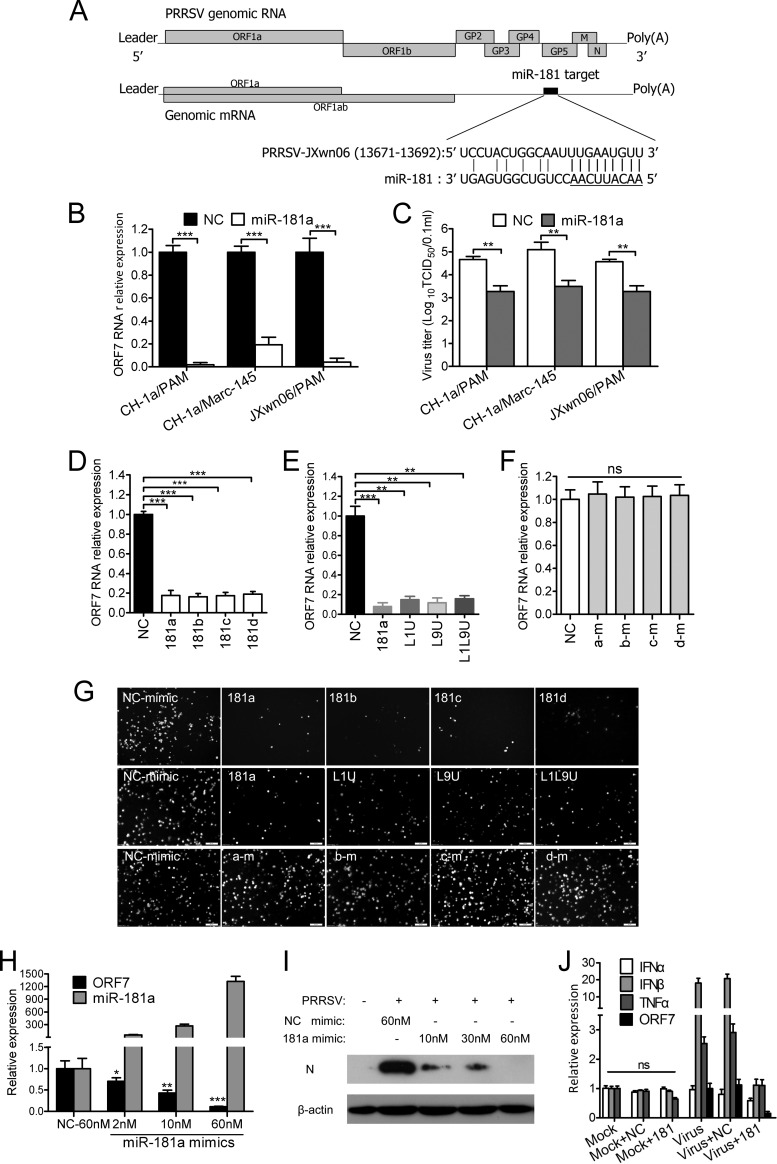

To examine which miRNAs can directly target the long UTR of PRRSV genomic RNA, we performed computational prediction analysis of the HP-PRRSV strain JXwn06 and the traditional type 2 PRRSV strain CH-1a using RegRNA (32) or ViTa (33) to predict miRNA target sites. Prediction results indicated that miR-181 could target the site (bp 13684 to 13691) in viral genomic RNA through seed base pairing (Fig. 1A). This target region was highly (96.84%) conserved in type 2 PRRSV, which now circulates in most commercial swine industries throughout the world.

Fig 1.

miR-181 inhibits viral gene expression and PRRSV production. (A) A model of miR-181 targeting PRRSV genomic RNA. In this model, we hypothesized that miR-181 could inhibit PRRSV replication by targeting 9 nucleotides in the viral genomic RNA as indicated. (B) qPCR analysis of viral ORF7 RNA from PAMs or Marc-145 cells transfected with negative control mimics (NC) or miR-181a mimics was performed 24 h after the transfection followed by infection with PRRSV CH-1a or JXwn06 for 24 h. (C) Virus titers in PAMs or Marc-145 cells transfected with NC or miR-181a mimics for 24 h and then infected with PRRSV CH-1a or JXwn06 for 36 h. (D to F) Analysis of ORF7 RNA levels in PAMs transfected with NC mimics, miR-181 family mimics (181a,181b, 181c, or 181d) (D), non-seed-mutated miR-181a mimics (L1U, L9U, or L1L9U) (E), or seed-mutated miR-181 family mimics (a-m, b-m, c-m, or d-m) (F) for 24 h and then infected with PRRSV JXwn06 for 24 h. (G) Immunofluorescence assay analysis of PRRSV N protein in PAMs transfected with miRNA mimics corresponding to panels D to F and infected with PRRSV JXwn06 for 36 h. (H and I) Dose-dependent downregulation of ORF7 gene expression was analyzed by qPCR (H) or subjected to Western blot analysis (I) in PAMs transfected with the indicated doses of miR-181a mimics for 24 h and then infected with PRRSV JXwn06 for 24 h (H) or 36 h (I). (J) qPCR analysis of IFN-α, IFN-β, or TNF-α mRNA and viral ORF7 RNA from PAMs transfected with NC or miR-181a mimics and infected with PRRSV JXwn06 for 24 h, normalized to GAPDH. Data are representative of the results of three independent experiments (means ± standard deviations [SD]). Statistical significance was analyzed by t test; *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001; ns, not significant.

To investigate whether miR-181 can inhibit PRRSV replication, we transfected chemically modified (2′-O-methyl-modified) miR-181 mimics into PAMs or Marc-145 cells before PRRSV infection and then examined viral gene expression and virus production. As expected, transfection of miR-181a mimics resulted in an over 80% reduction of the ORF7 gene expression of PRRSV CH-1a or JXwn06 strains (Fig. 1B) and repressed PRRSV production by at least 30-fold in PAMs or Marc-145 cells (Fig. 1C). Since all members of the same miRNA family (i.e., miRNAs with the same sequence at nucleotides 2 to 8) share the same predicted targets (34), we reasoned that all the miR-181 members can suppress PRRSV gene expression. Results from qPCR showed that all of the miR-181 family members did have anti-PRRSV activity in PAMs (Fig. 1D). As previously reported, miRNA-mRNA interaction may require seed-matched sites at nt 2 to 8 (34). Thus, we mutated miR-181a mimics at nonseed nucleotide 1, 9, or 1 and 9 and miR-181 members at seed nucleotides 2 to 5 (a-m, b-m, c-m, and d-m). Our results showed that three miR-181a mutants with nonseed mutations did not lose their ability to inhibit PRRSV gene expression (Fig. 1E). In contrast, seed mutations at nt 2 to 5 abrogated the ability of members of the miR-181 family to repress ORF7 gene expression (Fig. 1F), suggesting that the seed region was required for inhibiting PRRSV replication. To further investigate the effect of miR-181 inhibition on PRRSV infection, we used an immunofluorescence assay to detect PRRSV in PAMs. Results showed that PRRSV infection in PAMs was suppressed by all of the miR-181 family members (Fig. 1G, top) and miR-181a nonseed mutants (Fig. 1G, middle) but was not affected by miR-181 seed mutants (Fig. 1G, bottom). miR-181-mediated inhibition was further confirmed to occur in a dose-dependent manner. As shown in Fig. 1H and I, both the ORF7 mRNA level and protein level were significantly decreased as the levels of introduced miR-181a mimics increased in PAMs. Additionally, to rule out the possibility that this antiviral effect was due to miRNA mimic-stimulated TLR3 signal pathway effects, we transfected miRNA mimics into PAMs infected with or without PRRSV, and 24 h later we analyzed IFN-α/β or TNF-α expression. Our results showed that introduction of miRNA mimics did not induce IFN-α/β or TNF-α expression in either mock- or PRRSV-infected PAMs (Fig. 1J). Taken together, these results demonstrated that miR-181 was a strong inhibitor of PRRSV replication.

MiR-181c showed the strongest inhibition of PRRSV replication.

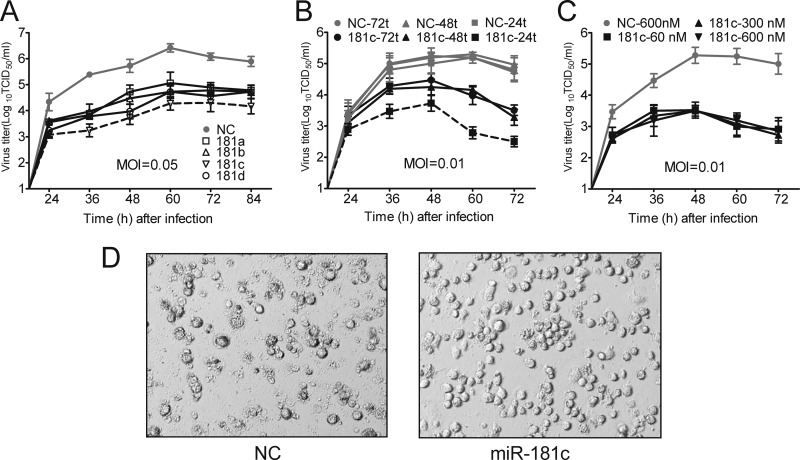

Since miR-181 was confirmed to have activity against PRRSV, we next analyzed the dynamics of HP-PRRSV isolate JXwn06 growth in PAMs transfected with miR-181 mimics. Viral growth was suppressed about 100-fold in PAMs transfected with all four miR-181 family members (Fig. 2A). Notably, miR-181c was the most efficient suppressor among the miR-181 family members. Then, we investigated the influence of different times between transfection and infection on the effect of inhibition. As shown in Fig. 2B, viral growth was inhibited much more significantly in PAMs infected with PRRSV at 24 h posttransfection than at 48 h or 72 h posttransfection, suggesting that cellular transcripts may competitively bind to miR-181c, resulting in exhaustion of introduced miR-181c. Next, we tested if transfection with an extremely higher dose of miR-181c mimics could increase its inhibitory effect on viral growth. Our results showed that miR-181c reached its maximum inhibitory effects at a dose of 60 nM (Fig. 2C). Importantly, miR-181c significantly relieved the PRRSV-induced cytopathogenic effect (CPE) in PAMs in comparison to control microRNA-treated PAM results, showing more viable intact PAMs and fewer dead cells (Fig. 2D). These results indicated that miR-181 family members, especially miR-181c, could effectively inhibit PRRSV JXwn06 replication in PAMs.

Fig 2.

Analysis of dynamics of PRRSV growth in PAMs transfected with miR-181 mimics. (A) Viral growth curves in PAMs transfected with NC or miR-181 family mimics for 24 h and then infected with PRRSV JXwn06 at an MOI of 0.05. Culture supernatants were collected at the indicated times and titrated. (B) The experiments were performed as described for panel A, except that an MOI of 0.01 was used and the miR-181c mimics were transfected for 24 h, 48 h, or 72 h. (C) The experiments were performed as described for panel A, except that an MOI of 0.01 was used and the miR-181c mimics were transfected at a concentration of 60 nM, 300 nM, or 600 nM. (D) PAMs from panel A were observed for development of CPE by bright-field microscopy at 84 h pi. Data are representative of the results of three independent experiments (means ± SD).

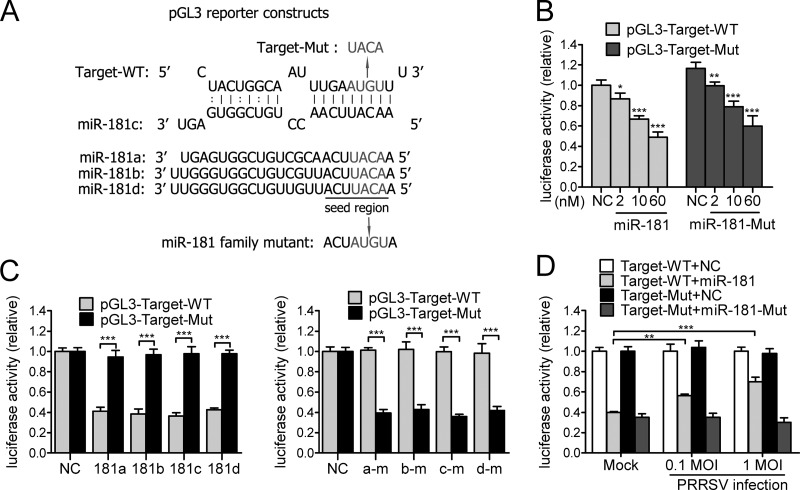

Direct targeting of the PRRSV genomic RNA by miR-181.

To confirm that the reduced viral gene expression and viral growth were due to direct targeting of PRRSV genomic RNA by miR-181, we created pGL3-Target-WT, a reporter construct containing the predicted target site region in the 3′ UTR, and another construct, pGL3-Target-Mut, with mutations of four nucleotides in the seed region (Fig. 3A). The reporter constructs and miRNA mimics were then cotransfected into HeLa cells and the luciferase activity was analyzed. As expected, wild-type miR-181 inhibited the luciferase activity of pGL3-Target-WT in a dose-dependent manner and miR-181 mutants inhibited the luciferase activity of correlated pGL3-Target-Mut dose dependently too (Fig. 3B). All four miR-181 family members significantly inhibited the luciferase activity of pGL3-Target-WT by ∼60% but did not suppress pGL3-Target-Mut activity (Fig. 3C). In the reciprocal experiment, four miR-181 family mutants significantly inhibited the luciferase activity of pGL3-Target-Mut but did not affect pGL3-Target-WT activity (Fig. 3C). To further verify that the direct viral RNA-miRNA interaction was truly involved in the inhibition of PRRSV replication, we proposed that PRRSV RNAs could mimic competing endogenous RNAs (41) to sequester miR-181 to indirectly regulate pGL3-Target-WT luciferase activity. To test this possibility, we cotransfected Marc-145 cells with miRNA mimics and luciferase reporter constructs after mock infection or PRRSV infection. Inhibition of pGL3-Target-WT luciferase activity by miR-181 was diminished 20% to 30% by PRRSV infection compared to mock infection, but the inhibition of pGL3-Target-Mut luciferase activity by miR-181 mutants was not affected (Fig. 3D), suggesting that PRRSV RNAs competed with pGL3-Target-WT to bind miR-181 and resulted in fewer miR-181 mimics to bind their target sites in luciferase reporter constructs. Taken together, these results demonstrated that miR-181 could directly target PRRSV genomic RNA.

Fig 3.

miR-181 directly targets PRRSV genomic RNA. (A) Predicted binding site for members of the miR-181 family in PRRSV genomic RNA. Gray indicates nucleotides replaced with the sequence indicated by the arrow in mutant reporter constructs or miR-181 family mutants. (B) Luciferase activity in lysates of HeLa cells cotransfected with pGL3-Target-WT or pGL3-Target-Mut reporter construct and either miR-181 (miR-181 member mixture) or miR-181-Mut (miR-181 member mutant mixture) mimics at different concentrations as indicated except that 60 nM was used for NC mimics. (C) Luciferase activity in lysates of HeLa cells as described for panel B except that miR-181 family members (181a, 181b, 181c, and 181d) (left) or mutant members (a-m, b-m, c-m, or d-m) (right) were cotransfected into cells with the two reporter constructs as indicated. (D) Luciferase activity in lysates of Marc-145 cells infected with PRRSV CH-1a at an MOI of 0.1 or 1 and cotransfected with reporter constructs and miRNA mimics. Data are representative of the results of three independent experiments (means ± SD). Statistical significance was analyzed by t test. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001; ns, not significant.

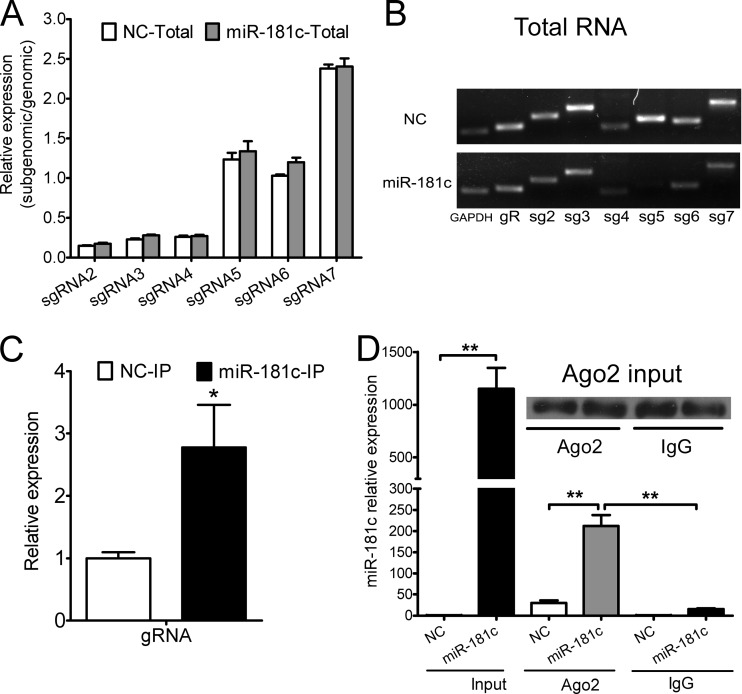

Physical interaction of miR-181c with viral genomic RNA.

As we indicated in Fig. 1A, miR-181 may target PRRSV genomic RNA. To obtain evidence for this model, we examined the physical interaction between viral RNAs and miR-181c using an RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC) immunoprecipitation assay. Even though the relative expression of each subgenomic mRNA in comparison to genomic RNA remained consistent between two treatments (Fig. 4A) in the whole-cell lysates, the expression of PRRSV JXwn06 genomic RNA and of six subgenomic mRNAs in PAMs transfected with miR-181c mimics was significantly decreased compared to that of the NC mimics (Fig. 4B), indicating that miR-181c was more likely to interact with the genomic RNA than with subgenomic mRNAs. Then, input cell lysates were immunoblotted using antibody against Ago2. In the coimmunoprecipitated RNA of cell lysates, we detected more than 2-fold enrichment for viral genomic RNA in the presence of miR-181c mimics compared to NC mimics (Fig. 4C). miR-181c associated with Ago2 protein was significantly enriched to a 15-fold increase compared to the IgG isotype control level (Fig. 4D). Taken together, these results demonstrated that miR-181c physically interacted with viral genomic RNA in the RISC.

Fig 4.

miR-181c physically binds to viral genomic RNA in the RISC. (A) qPCR analysis of the relative expression of subgenomic mRNAs (sgRNAs) in comparison to genomic RNA (gRNA) among RNAs extracted from total samples of lysates from PAMs transfected with NC or miR-181c mimics and subsequently infected with PRRSV JXwn06 at an MOI of 0.05, normalized to GAPDH. (B) RT-PCR assay of gRNA (gR) or sgRNAs (sg) from panel A. (C) qPCR analysis of genomic RNA among RNAs extracted from RISC immunoprecipitates of the cells as described for panel A, normalized to GAPDH. (D) qPCR analysis of miR-181c among RNAs extracted from total samples, RISC immunoprecipitates, or IgG (isotype control) immunoprecipitates of lysates from PAMs as described for panel A, normalized to GAPDH. Top, Western blot analysis of Ago2 in input cell lysates. Data are representative of the results of three independent experiments (means ± SD). Statistical significance was analyzed by t test. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001.

In minimally permissive cells or tissues, miR-181 and other potential PRRSV-targeting miRNAs are more abundant.

Since miR-181 was confirmed to suppress PRRSV replication, we next tried to analyze the PRRSV-targeting miRNAs in different cells or tissues to see if the expression of virus-targeting miRNAs was negatively correlated with viral replication capacity. In a natural host, PRRSV has a tropism for cells of the monocyte-macrophage lineage and replicates preferentially in PAMs and subsets of macrophages in lymphoid tissues but not in peritoneal macrophages (42). Thus, we first determined miR-181 expression in PAMs. qPCR analysis showed that none of the miR-181 family members were abundant in PAMs and that their expression was approximately 1,000-fold lower than that of miR-21, which was highly expressed in PAMs (even more than U6 RNA). PRRSV JXwn06 infection did not alter the expression profile of miR-181 family members except that miR-181c expression was decreased (Fig. 5A), which was consistent with our deep sequencing data (data not shown). Next, we analyzed miR-181 expression in minimally permissive or nonpermissive cells, including microglias (1, 43), peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) (44), and peritoneal macrophages (45). Copy number estimations revealed that miR-181 family members in those cells were expressed at much higher levels than in PAMs (Fig. 5B). For example, the expression of miR-181a in peritoneal macrophages, microglias, and PBMCs was about 30-, 8-, and 2-fold higher than that in PAMs, respectively. And expression of miR-181c in peritoneal macrophages, microglias, and PBMCs was about 25-, 10-, and 9-fold higher than that in PAMs, respectively.

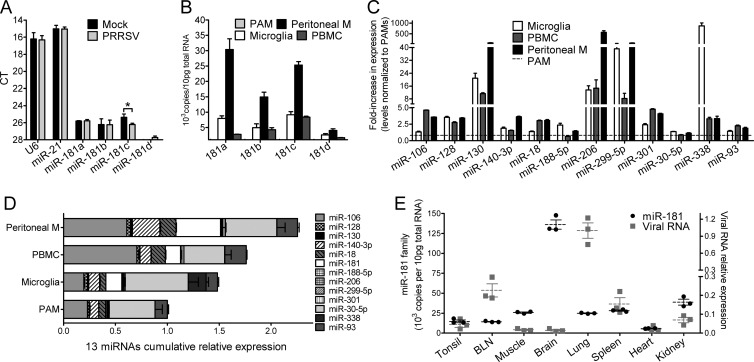

Fig 5.

Analysis of miR-181 and potential PRRSV-targeting miRNAs in different primary cells and tissues. (A) qPCR analysis of miR-181 family or miR-21 levels from PAMs with mock infection or PRRSV JXwn06 infection for 24 h (24 h pi). CT, cycle threshold. U6 RNA is a reference control. (B) qPCR analysis of miR-181 family levels in PAMs, microglias, PBMCs, or peritoneal macrophages (Peritoneal M) isolated from specific-pathogen-free (SPF) pigs. (C) Average fold increase in levels of potential PRRSV-targeting miRNAs in cells analyzed as described for panel B normalized to PAMs, as determined by qPCR. (D) Estimation of total cumulative expression of 13 miRNAs in cells analyzed by qPCR as described for panel B. Relative expression levels in comparison to PAMs are shown. Data in panels A to D are representative of the results of three independent experiments (means ± standard errors [SE]). (E) qPCR analysis of miR-181 family levels and viral RNA (ORF7) level in different tissues from pigs infected with PRRSV strain JXwn06 (the tissue samples were collected from another animal study). Each data point represents one pig. Data represent a plot of the means of miRNA or viral RNA levels from three individual samples (means ± SE).

There are more predicted microRNAs besides miR-181 that could target PRRSV. Therefore, we analyzed the expression of miR-206 and all 11 of the other potential PRRSV-targeting miRNAs (whose targets are more than 90% conserved in PRRSV strains, as predicted) in PAMs, peritoneal macrophages, microglias, and PBMCs. In minimally permissive or nonpermissive cells, most of these miRNAs were expressed at levels much higher than those in PAMs. For example, expression of miR-206 in peritoneal macrophages, microglias, and PBMCs was about 500-, 16-, and 14-fold higher than that in PAMs, respectively (Fig. 5C). Next, we estimated the cumulative expression of 13 miRNAs according to the absolute quantity of each miRNA. The total expression of the 13 PRRSV-targeting miRNAs in peritoneal macrophages, PBMCs, or microglias was higher (1.5- to 2.4-fold increase) than that in PAMs (Fig. 5D). Notably, some of these miRNAs, such as miR-106, miR-140-3p, miR-18, miR-181, miR-338, and miR-93, contributed more to this difference than others (Fig. 5D), suggesting that these miRNAs could be related to the low PRRSV replication capacity in those cells. Finally, we examined the expression of miR-181 in different tissues from PRRSV-infected pigs. The viral load level was high in lung and bronchial lymph nodes (BLN), and miR-181 expression level was relatively low in them, which was contrary to the results in brain. Viral loads in lung and BLN were ∼100 and 20 times higher than that in brain, respectively. However, miR-181 expression levels were ∼5 and 10 times higher in brain than that in lung and BLN, respectively (Fig. 5E).

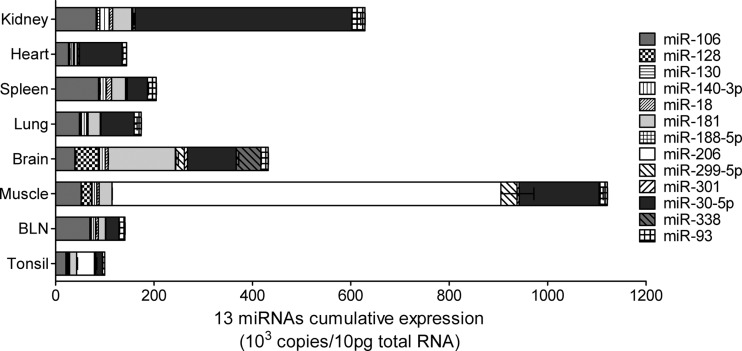

We next estimated the total cumulative miRNA copy numbers of miR-181 and other potential PRRSV-targeting miRNAs in eight tissues. Our results showed that tissues with a low viral load (such as kidney, brain, and muscle) expressed more PRRSV-targeting miRNAs, while tissues with a high viral load (such as lung, BLN, and spleen) had fewer PRRSV-targeting miRNAs (Fig. 6 and 5E). Interestingly, miR-206 was specifically expressed at a high level in muscle; miR-128, miR-181, and miR-338 were specific for brain; and miR-30-5p was specifically expressed at a higher level in kidney (Fig. 6), suggesting that these tissue-specific miRNAs may influence PRRSV natural infection in the corresponding tissues.

Fig 6.

Analysis of total cumulative expression of potential PRRSV-targeting miRNAs in different tissues. Estimations of total cumulative expression of 13 miRNAs in eight tissues from pigs infected with PRRSV JXwn06 determined by qPCR (the tissue samples were collected as described for Fig. 5E) are shown. Data represent the means of miRNA levels from three individual samples (means ± SE).

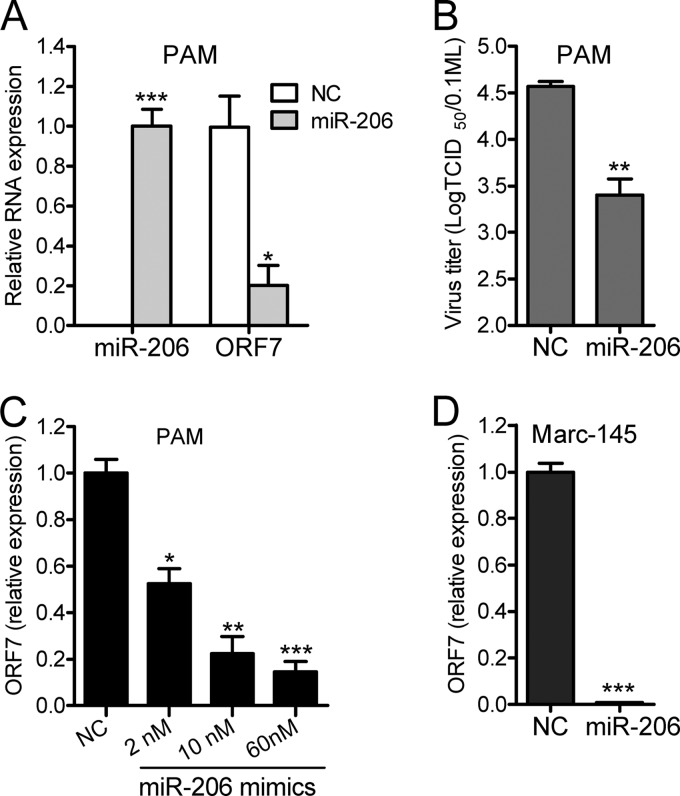

To verify that other potential PRRSV-targeting miRNAs can also inhibit PRRSV replication, we selected miR-206 to test its activity against PRRSV infection. As shown in Fig. 7, miR-206 suppressed both HP-PRRSV strain JXwn06 replication in PAMs and traditional type 2 strain CH-1a infection in Marc-145 cells. And this inhibition occurred in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 7C). Whether other potential PRRSV-targeting miRNAs can also impair PRRSV infection remains to be investigated in the future.

Fig 7.

miR-206 inhibits PRRSV replication. (A) qPCR analysis of miR-206 or viral ORF7 RNA from PAMs transfected with NC or miR-206 mimics and then infected with PRRSV JXwn06 for 24 h, presented relative to the expression of U6 RNA or GAPDH mRNA. (B) Virus titers in PAMs transfected with NC or miR-206 mimics and infected with PRRSV JXwn06 for 36 h. (C) Dose dependency of downregulation of ORF7 gene expression was observed in PAMs transfected with the indicated dose of miR-206 mimics and infected with PRRSV JXwn06 for 24 h. (D) qPCR analysis of viral ORF7 RNA from Marc-145 cells transfected with NC or miR-206 mimics and infected with PRRSV CH-1a for 24 h. Data are representative of the results of three independent experiments (means ± SD). Statistical significance was analyzed by Student's t test. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001.

In summary, these findings provided clues that miR-181 and other host miRNAs might be associated with viral replication capacity or viral tropism in different cells or tissues.

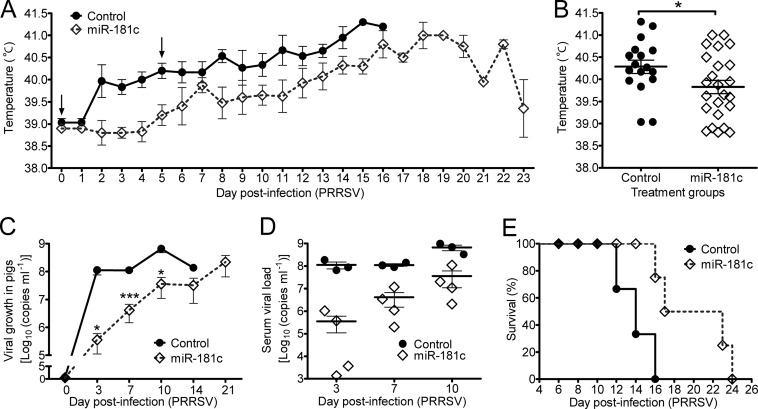

Intranasal delivery of miR-181c inhibited highly pathogenic PRRSV replication in pigs.

Finally, to address whether miR-181-mediated inhibition of PRRSV replication can be used in therapy, we tested the anti-PRRSV effects of miR-181c in HP-PRRSV JXwn06-infected pigs. The delivery route of intranasal inhalation has been applied in many siRNA-mediated therapies against respiratory viruses (21, 23, 27). Thus, we intranasally delivered chemically modified miR-181c mimics (2.5 mg/kg per dose) mixed with D5W solution, which has been used as a carrier in clinics (46) or applied in delivery of siRNA (23, 46), into 4-week-old SPF pigs (n = 4). Five hours later, pigs were challenged intranasally with HP-PRRSV JXwn06 (each with 1 ml of 105.2 TCID50 PRRSV). The miR-181c treatment group was given miR-181c mimics (2.5 mg/kg per dose) for a second time 5 days postinfection (dpi). Pigs in the control group (n = 3) were given NC miRNA mimics and challenged with HP-PRRSV JXwn06 in the same way as the miR-181c group. It is well known that HP-PRRSV strain infection is characterized by high fever, high morbidity, and high mortality in pigs (1). Therefore, we recorded the rectal temperature of each pig daily until it died (Fig. 8A). We found that the rectal temperature of pigs in the miR-181c treatment group did not rise until 5 days after infection, while the temperature of pigs in the control group rapidly rose to 40°C (about 1°C higher) at 2 dpi, suggesting that the first miR-181c administration took effect at the initial stage. At 7 dpi, the rectal temperature of pigs in the miR-181c group rose close to the level of the control group shortly but afterward decreased again and rose slowly in comparison to the control group level, suggesting that the second miR-181c administration had started working. Comparison of the mean rectal temperatures of the two groups revealed a temperature 0.5°C lower in the miR-181c group than that in the control group (Fig. 8B). Meanwhile, PRRSV RNA copies were analyzed in the serum samples at 3, 7, 10, 14, and 21 dpi (Fig. 8C and D). The average viral RNA load in serum was 100- to 300-fold lower in the miR-181c group than that in the control group at 3, 7, and 10 dpi. The viral growth curve showed that PRRSV growth of the miR-181c group rose slowly and peaked at 21 dpi, while viral growth of the control group rose rapidly to 108 (RNA copies/ml) at 3 dpi and peaked at ∼109 (RNA copies/ml) at 10 dpi (Fig. 8C). Notably, two of the four pigs from the miR-181c group showed an extremely low viral RNA level at 3 dpi and then reached the viral RNA levels of the other two later at 7 and 10 dpi (Fig. 8D), respectively. HP-PRRSV JXwn06 is highly virulent and can cause 100% mortality when animals are challenged with 1 ml of 105.2 TCID50 PRRSV (Fig. 8E). However, the survival curve showed that the miR-181c group survived significantly longer (20 days) than the control group (14 days) (Fig. 8E). These results provided direct evidence that miR-181c could inhibit PRRSV replication in vivo and that therapeutic miR-181c delivery could relieve the severity of the infection in pigs infected with the HP-PRRSV strain to make them survive longer, highlighting the possibility of treating PRRSV-infected pigs with miR-181 in the future.

Fig 8.

miR-181c exhibits antiviral activity in vivo and relieves pigs from PRRSV-induced fever. (A) Rectal temperature curve of pigs from two groups after PRRSV JXwn06 infection. The arrows indicate the day of NC or miR-181c administration (control group, n = 3; miR-181c group, n = 4). (B) Distribution of average rectal temperatures. Each data point represents a value of rectal temperature of one pig on 1 day throughout the 23-day period. (C) Viral growth curves in pigs of two groups. Viral ORF7 RNA copy numbers were determined in serum samples at the indicated times. (D) Analysis of viral load in serum from 3 individuals with control administration or 4 individuals with miR-181c administration at the indicated times. (E) Survival curves of pigs treated with miR-181c or NC mimics after PRRSV JXwn06 infection. Pigs treated with miR-181c survived significantly longer than control-treated pigs, 20 and 14 days, respectively (log rank test; P = 0.0152). Data in panels A to D are presented as means ± SE. Statistical significance was analyzed by t test. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001.

DISCUSSION

Cellular miRNAs have been identified to target viruses in host cells in many reports (3, 5–9). However, most of these studies were performed in cell cultures and did not use cellular miRNA as a therapeutic tool to directly target virus in vivo except one case in which host miR-122 was used as a target for HCV treatment in primates (28). The rationale for that report was that miR-122 can facilitate HCV replication (17). In the present study, we investigated whether the cellular miRNA-mediated RNAi could play an important role in controlling PRRSV replication and be used as a therapeutic tool for treating viral diseases. Here, we showed that transfection of miR-181 mimics inhibited PRRSV replication through targeting highly conserved regions in the viral genomic RNA and that therapeutic miR-181c mimics could protect pigs against PRRSV infection.

There have been many reports showing that cellular miRNAs could interact with virus RNAs, resulting in inhibition of virus replication (5, 6, 8, 9, 11). Our results here showed that miR-181 could inhibit PRRSV infection, further confirming that cellular miRNAs could counteract viral infections. However, in a review paper (47), the authors proposed that it is unlikely that cellular miRNAs have evolved specifically as an antiviral defense mechanism, because miRNAs are conserved across a wide variety of species but viruses usually have very narrow species tropism and the polymerases of viruses often have a high mutation rate resulting in poorly conserved miRNA targets. This was supported by our data showing that many predicted miRNA targets in PRRSV genome were not well conserved and that PRRSV-targeting miRNAs, including miR-181, were not upregulated in response to PRRSV infection, suggesting that miR-181 interaction with PRRSV might be just a fortuitous natural phenomenon. Nevertheless, cellular miRNAs still have the potential to have a great impact on virus replication just like the impact of miR-122 interacting with HCV (17), and our results did reveal a big role played by host miR-181 in controlling PRRSV replication in animals.

Even though the miRNA-mediated antiviral response may not have evolved specifically for targeting particular virus infection, it has been proposed that cellular miRNAs may influence viral tropism in the natural context (47, 48). This hypothesis is supported by compelling evidence that miR-122 plays a key role in determining the tropism of HCV (49). In our work, we further showed that the expression of miR-181 and some other miRNAs negatively correlated with PRRSV infectivity in different cells and tissues (Fig. 5 and 6). In its natural host, PRRSV has a tropism for cells of the monocyte-macrophage lineage such as PAMs and subsets of macrophages in lymphoid tissues but not for peritoneal macrophages. Freshly isolated peripheral blood monocytes (BMo) are refractory to infection, and only about 1% to 2% of them can be infected with PRRSV. Interestingly, miR-181 was expressed at a much higher level in peritoneal macrophages and peripheral blood monocytes than in PAMs (∼42- and 10-fold higher than that in PAMs, respectively), and the total level of miRNAs which could potentially target PRRSV in peritoneal macrophages and peripheral blood monocytes was also higher than that in PAMs, supporting the hypothesis that miR-181 and other PRRSV-targeting miRNAs could play an important role in determining PRRSV tropism for cells. It is difficult to isolate macrophages from all tissues, so we determined the miRNA expression in tissues directly. PRRSV-targeting miRNAs such as miR-181 and miR-338 were abundant in brain, at a level that was about 5 times higher than that in lung, whereas virus load in lung was about 100 times higher than in brain (Fig. 5 and 6). Thus, our findings provided evidence that the cellular miRNAs proposed in this work might be associated with PRRSV tropism or viral replication capacity in different cells or tissues, indirectly supporting the role of cellular miRNAs in controlling virus replication.

Since siRNAs were shown to be an effective tool to knock down gene expression, the use of siRNAs has been applied in many fields such as treatment for diseases (20). In fact, many studies have been done in vivo to test whether siRNAs could be used to treat viral diseases (21–27). However, outcomes of siRNA-mediated therapeutics have raised a number of issues about their safety. One of these issues is the potential side effect caused by siRNAs, which is called the miRNA-like off-target effect (50). Exogenous siRNAs can act as miRNAs, each cellular miRNA can potentially target hundreds of genes (51), and introduction of siRNAs or miRNAs can have serious consequences. Thus, the use of host miRNAs for directly targeting virus in therapies represents a big challenge. In our study, we did not test whether miR-181c could induce severe side effects. Nevertheless, miR-181 is characterized by favorable immunological functions such as positive regulation of immunity (52–55) and could be considered an adjuvant for the treatment of viral diseases or immunization. In fact, our unpublished data did show that transfection of miR-181 mimics resulted in a degradation of some of the reported cellular targets (such as NLK, DUSP5, PTPN22, PTPN22, Bcl2, and CD69). However, whether delivered miR-181 mimics could positively enhance immunity in pigs remains to be investigated in future studies.

Another issue related to RNAi-mediated therapeutics is that viruses are able to rapidly evolve escape mutants that can avoid further inhibition by introduced siRNAs (56, 57). It is true that PRRSV can mutate rapidly, and estimations showed a mutation rate of 1 to 3 × 10−2 substitutions per site and year, which is similar to that of other rapidly evolving RNA viruses (58). However, the predicted target region for miR-181 is highly conserved in type 2 PRRSV. Obviously, much work needs to be done to verify this possibility.

In our study, we found that miR-181c strongly inhibited PRRSV replication in vitro, and PRRSV replication seemed to be suppressed remarkably in vivo at the initial phase. Our results were consistent with two recent studies (59, 60) which reported that recombinant viruses containing miRNA target sequences could be modulated or eliminated by host endogenous miRNAs, suggesting that viruses could be targeted by miRNA in vivo. In their studies, the incorporated miRNA target sequences were all perfectly complementary to the cellular miRNAs. However, in our study, miR-181 interacted with PRRSV RNA through partial complementarity, indicating the potential of miR-181 to control PRRSV replication in vitro and in vivo.

In the animal experiments, we demonstrated that miR-181c could repress PRRSV replication in pigs (Fig. 8). After the first delivery of miR-181c, average virus load in serum was about 400-fold lower than that in the control group. Surprisingly, in 2 of the 4 miR-181c-treated pigs, there was a ∼104- to 105-fold reduction of virus load compared to control pig results and the load was about 2 to 5 × 102-fold lower than in the other two miR-181c-treated pigs. The reason for this result could be that we efficiently delivered the miR-181c into the former two pigs (the latter two pigs might have sneezed out part of the miR-181c). However, in the late period of the experiments, it appeared that PRRSV replication could not be controlled. We speculated that the treatment consisting of only two deliveries of miR-181c at day 0 and day 5 could not provide enough protection against PRRSV infection. On the other hand, although PRRSV preferentially infects macrophages in lung, it also infects macrophages in other tissues. Thus, because of the delivery route limitation, the intranasal delivery could not protect other tissues such as lymph nodes and spleen from PRRSV infection. And once the virus spreads to other tissues, it is hard to control by intranasal delivery. Therefore, developing a new and effective delivery route or multiple deliveries might be helpful for controlling PRRSV replication in vivo.

Overall, our work provides evidence for the important role played by host miRNAs in modulating PRRSV replication under natural conditions and the potential relationship between host miRNAs and viral pathogenesis and also implies that cellular miRNAs can be considered therapeutic tools for antiviral therapy in the future.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (30770101) and the Faculty Starting Grant and State Key Laboratory of Agrobiotechnology (grants 2010SKLAB06-1 and 2012SKLAB01-6), China Agricultural University, China.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 14 November 2012

REFERENCES

- 1. Tian K, Yu X, Zhao T, Feng Y, Cao Z, Wang C, Hu Y, Chen X, Hu D, Tian X, Liu D, Zhang S, Deng X, Ding Y, Yang L, Zhang Y, Xiao H, Qiao M, Wang B, Hou L, Wang X, Yang X, Kang L, Sun M, Jin P, Wang S, Kitamura Y, Yan J, Gao GF. 2007. Emergence of fatal PRRSV variants: unparalleled outbreaks of atypical PRRS in China and molecular dissection of the unique hallmark. PLoS One 2:e526 doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0000526 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Thiel HJ, Meyers G, Stark R, Tautz N, Rumenapf T, Unger G, Conzelmann KK. 1993. Molecular characterization of positive-strand RNA viruses: pestiviruses and the porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus (PRRSV). Arch. Virol. Suppl. 7:41–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Lecellier CH, Dunoyer P, Arar K, Lehmann-Che J, Eyquem S, Himber C, Saib A, Voinnet O. 2005. A cellular microRNA mediates antiviral defense in human cells. Science 308:557–560 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Li HW, Ding SW. 2005. Antiviral silencing in animals. FEBS Lett. 579:5965–5973 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Nathans R, Chu CY, Serquina AK, Lu CC, Cao H, Rana TM. 2009. Cellular microRNA and P bodies modulate host-HIV-1 interactions. Mol. Cell 34:696–709 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Otsuka M, Jing Q, Georgel P, New L, Chen JM, Mols J, Kang YJ, Jiang ZF, Du X, Cook R, Das SC, Pattnaik AK, Beutler B, Han JH. 2007. Hypersusceptibility to vesicular stomatitis virus infection in Dicer1-deficient mice is due to impaired miR24 and miR93 expression. Immunity 27:123–134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Pedersen IM, Cheng G, Wieland S, Volinia S, Croce CM, Chisari FV, David M. 2007. Interferon modulation of cellular microRNAs as an antiviral mechanism. Nature 449:919–922 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Song L, Liu H, Gao S, Jiang W, Huang W. 2010. Cellular microRNAs inhibit replication of the H1N1 influenza A virus in infected cells. J. Virol. 84:8849–8860 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Chen Y, Shen A, Rider PJ, Yu Y, Wu K, Mu Y, Hao Q, Liu Y, Gong H, Zhu Y, Liu F, Wu J. 2011. A liver-specific microRNA binds to a highly conserved RNA sequence of hepatitis B virus and negatively regulates viral gene expression and replication. FASEB J. 25:4511–4521 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Gottwein E, Cullen BR. 2008. Viral and cellular microRNAs as determinants of viral pathogenesis and immunity. Cell Host Microbe 3:375–387 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Huang J, Wang F, Argyris E, Chen K, Liang Z, Tian H, Huang W, Squires K, Verlinghieri G, Zhang H. 2007. Cellular microRNAs contribute to HIV-1 latency in resting primary CD4+ T lymphocytes. Nat. Med. 13:1241–1247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Pfeffer S, Zavolan M, Grasser FA, Chien M, Russo JJ, Ju J, John B, Enright AJ, Marks D, Sander C, Tuschl T. 2004. Identification of virus-encoded microRNAs. Science 304:734–736 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Umbach JL, Kramer MF, Jurak I, Karnowski HW, Coen DM, Cullen BR. 2008. MicroRNAs expressed by herpes simplex virus 1 during latent infection regulate viral mRNAs. Nature 454:780–783 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lu CC, Li Z, Chu CY, Feng J, Sun R, Rana TM. 2010. MicroRNAs encoded by Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus regulate viral life cycle. EMBO Rep. 11:784–790 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kim S, Lee S, Shin J, Kim Y, Evnouchidou I, Kim D, Kim YK, Kim YE, Ahn JH, Riddell SR, Stratikos E, Kim VN, Ahn K. 2011. Human cytomegalovirus microRNA miR-US4-1 inhibits CD8(+) T cell responses by targeting the aminopeptidase ERAP1. Nat. Immunol. 12:984–991 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Nachmani D, Lankry D, Wolf DG, Mandelboim O. 2010. The human cytomegalovirus microRNA miR-UL112 acts synergistically with a cellular microRNA to escape immune elimination. Nat. Immunol. 11:806–813 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Jopling CL, Yi M, Lancaster AM, Lemon SM, Sarnow P. 2005. Modulation of hepatitis C virus RNA abundance by a liver-specific microRNA. Science 309:1577–1581 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lodish HF, Zhou B, Liu G, Chen CZ. 2008. Micromanagement of the immune system by microRNAs. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 8:120–130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. O'Connell RM, Rao DS, Chaudhuri AA, Baltimore D. 2010. Physiological and pathological roles for microRNAs in the immune system. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 10:111–122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Davidson BL, McCray PB., Jr 2011. Current prospects for RNA interference-based therapies. Nat. Rev. Genet. 12:329–340 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Bitko V, Musiyenko A, Shulyayeva O, Barik S. 2005. Inhibition of respiratory viruses by nasally administered siRNA. Nat. Med. 11:50–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Geisbert TW, Lee AC, Robbins M, Geisbert JB, Honko AN, Sood V, Johnson JC, de Jong S, Tavakoli I, Judge A, Hensley LE, Maclachlan I. 2010. Postexposure protection of non-human primates against a lethal Ebola virus challenge with RNA interference: a proof-of-concept study. Lancet 375:1896–1905 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Li BJ, Tang Q, Cheng D, Qin C, Xie FY, Wei Q, Xu J, Liu Y, Zheng BJ, Woodle MC, Zhong N, Lu PY. 2005. Using siRNA in prophylactic and therapeutic regimens against SARS coronavirus in Rhesus macaque. Nat. Med. 11:944–951 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Palliser D, Chowdhury D, Wang QY, Lee SJ, Bronson RT, Knipe DM, Lieberman J. 2006. An siRNA-based microbicide protects mice from lethal herpes simplex virus 2 infection. Nature 439:89–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Tompkins SM, Lo CY, Tumpey TM, Epstein SL. 2004. Protection against lethal influenza virus challenge by RNA interference in vivo. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 101:8682–8686 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Wu Y, Navarro F, Lal A, Basar E, Pandey RK, Manoharan M, Feng Y, Lee SJ, Lieberman J, Palliser D. 2009. Durable protection from herpes simplex virus-2 transmission following intravaginal application of siRNAs targeting both a viral and host gene. Cell Host Microbe 5:84–94 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Zhang W, Yang H, Kong X, Mohapatra S, San Juan-Vergara H, Hellermann G, Behera S, Singam R, Lockey RF, Mohapatra SS. 2005. Inhibition of respiratory syncytial virus infection with intranasal siRNA nanoparticles targeting the viral NS1 gene. Nat. Med. 11:56–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Lanford RE, Hildebrandt-Eriksen ES, Petri A, Persson R, Lindow M, Munk ME, Kauppinen S, Orum H. 2010. Therapeutic silencing of microRNA-122 in primates with chronic hepatitis C virus infection. Science 327:198–201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Pasternak AO, Spaan WJ, Snijder EJ. 2006. Nidovirus transcription: how to make sense.? J. Gen. Virol. 87:1403–1421 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Hu S, Chao CC, Khanna KV, Gekker G, Peterson PK, Molitor TW. 1996. Cytokine and free radical production by porcine microglia. Clin. Immunol. Immunopathol. 78:93–96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Zhou L, Zhang J, Zeng J, Yin S, Li Y, Zheng L, Guo X, Ge X, Yang H. 2009. The 30-amino-acid deletion in the Nsp2 of highly pathogenic porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus emerging in China is not related to its virulence. J. Virol. 83:5156–5167 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Huang HY, Chien CH, Jen KH, Huang HD. 2006. RegRNA: an integrated web server for identifying regulatory RNA motifs and elements. Nucleic Acids Res. 34:W429–W434 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Hsu PW, Lin LZ, Hsu SD, Hsu JB, Huang HD. 2007. ViTa: prediction of host microRNAs targets on viruses. Nucleic Acids Res. 35:D381–D385 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Bartel DP. 2009. MicroRNAs: target recognition and regulatory functions. Cell 136:215–233 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Tamura K, Peterson D, Peterson N, Stecher G, Nei M, Kumar S. 2011. MEGA5: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis using maximum likelihood, evolutionary distance, and maximum parsimony methods. Mol. Biol. Evol. 28:2731–2739 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Yang CH, Yue J, Fan M, Pfeffer LM. 2010. IFN induces miR-21 through a signal transducer and activator of transcription 3-dependent pathway as a suppressive negative feedback on IFN-induced apoptosis. Cancer Res. 70:8108–8116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Bookout AL, Cummins CL, Mangelsdorf DJ, Pesola JM, Kramer MF. 2006. High-throughput real-time quantitative reverse transcription PCR. Curr. Protoc. Mol. Biol. 73:15.8.1–15.8.28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Moreno JL, Zuniga S, Enjuanes L, Sola I. 2008. Identification of a coronavirus transcription enhancer. J. Virol. 82:3882–3893 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Fu Y, Quan R, Zhang H, Hou J, Tang J, Feng WH. 2012. Porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus induces interleukin-15 through the NF-κB signaling pathway. J. Virol. 86:7625–7636 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Wang W-X, Wilfred BR, Hu Y, Stromberg AJ, Nelson PT. 2010. Anti-Argonaute RIP-Chip shows that miRNA transfections alter global patterns of mRNA recruitment to microribonucleoprotein complexes. RNA 16:394–404 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Salmena L, Poliseno L, Tay Y, Kats L, Pandolfi PP. 2011. A ceRNA hypothesis: the Rosetta Stone of a hidden RNA language? Cell 146:353–358 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Van Breedam W, Delputte PL, Van Gorp H, Misinzo G, Vanderheijden N, Duan XB, Nauwynck HJ. 2010. Porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus entry into the porcine macrophage. J. Gen. Virol. 91:1659–1667 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Rossow KD, Shivers JL, Yeske PE, Polson DD, Rowland RRR, Lawson SR, Murtaugh MP, Nelson EA, Collins JE. 1999. Porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus infection in neonatal pigs characterised by marked neurovirulence. Vet. Rec. 144:444–448 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Christopher-Hennings J, Holler LD, Benfield DA, Nelson EA. 2001. Detection and duration of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus in semen, serum, peripheral blood mononuclear cells, and tissues from Yorkshire, Hampshire, and Landrace boars. J. Vet. Diagn. Invest. 13:133–142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Duan X, Nauwynck HJ, Pensaert MB. 1997. Effects of origin and state of differentiation and activation of monocytes/macrophages on their susceptibility to porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus (PRRSV). Arch. Virol. 142:2483–2497 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Ghanayem NS, Yee L, Nelson T, Wong S, Gordon JB, Marcdante K, Rice TB. 2001. Stability of dopamine and epinephrine solutions up to 84 hours. Pediatr. Crit. Care Med. 2:315–317 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Umbach JL, Cullen BR. 2009. The role of RNAi and microRNAs in animal virus replication and antiviral immunity. Genes Dev. 23:1151–1164 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Cullen BR. 2006. Viruses and microRNAs. Nat. Genet. 38(Suppl):S25–S30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Fukuhara T, Kambara H, Shiokawa M, Ono C, Katoh H, Morita E, Okuzaki D, Maehara Y, Koike K, Matsuura Y. 2012. Expression of microRNA miR-122 facilitates an efficient replication in nonhepatic cells upon infection with hepatitis C virus. J. Virol. 86:7918–7933 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Jackson AL, Linsley PS. 2010. Recognizing and avoiding siRNA off-target effects for target identification and therapeutic application. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 9:57–67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Selbach M, Schwanhausser B, Thierfelder N, Fang Z, Khanin R, Rajewsky N. 2008. Widespread changes in protein synthesis induced by microRNAs. Nature 455:58–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Chen CZ, Li L, Lodish HF, Bartel DP. 2004. MicroRNAs modulate hematopoietic lineage differentiation. Science 303:83–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Cichocki F, Felices M, McCullar V, Presnell SR, Al-Attar A, Lutz CT, Miller JS. 2011. Cutting edge: microRNA-181 promotes human NK cell development by regulating Notch signaling. J. Immunol. 187:6171–6175 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Li QJ, Chau J, Ebert PJ, Sylvester G, Min H, Liu G, Braich R, Manoharan M, Soutschek J, Skare P, Klein LO, Davis MM, Chen CZ. 2007. miR-181a is an intrinsic modulator of T cell sensitivity and selection. Cell 129:147–161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Neilson JR, Zheng GXY, Burge CB, Sharp PA. 2007. Dynamic regulation of miRNA expression in ordered stages of cellular development. Genes Dev. 21:578–589 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Boden D, Pusch O, Lee F, Tucker L, Ramratnam B. 2003. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 escape from RNA interference. J. Virol. 77:11531–11535 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Das AT, Brummelkamp TR, Westerhout EM, Vink M, Madiredjo M, Bernards R, Berkhout B. 2004. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 escapes from RNA interference-mediated inhibition. J. Virol. 78:2601–2605 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Prieto C, Vazquez A, Nunez JI, Alvarez E, Simarro I, Castro JM. 2009. Influence of time on the genetic heterogeneity of Spanish porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus isolates. Vet. J. 180:363–370 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Heiss BL, Maximova OA, Thach DC, Speicher JM, Pletnev AG. 2012. MicroRNA targeting of neurotropic flavivirus: effective control of virus escape and reversion to neurovirulent phenotype. J. Virol. 86:5647–5659 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Kelly EJ, Nace R, Barber GN, Russell SJ. 2010. Attenuation of vesicular stomatitis virus encephalitis through microRNA targeting. J. Virol. 84:1550–1562 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]