Abstract

Chronic airway disorders, including chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), cystic fibrosis, and asthma, are associated with persistent pulmonary inflammation and goblet cell metaplasia and contribute to significant morbidity and mortality worldwide. While the molecular pathogenesis of these disorders is actively studied, little is known regarding the transcriptional control of goblet cell differentiation and mucus hyperproduction. Herein, we demonstrated that pulmonary allergen sensitization induces expression of FOXM1 transcription factor in airway epithelial and inflammatory cells. Conditional deletion of the Foxm1 gene from either airway epithelium or myeloid inflammatory cells decreased goblet cell metaplasia, reduced lung inflammation, and decreased airway resistance in response to house dust mite allergen (HDM). FOXM1 induced goblet cell metaplasia and Muc5AC expression through the transcriptional activation of Spdef. FOXM1 deletion reduced expression of CCL11, CCL24, and the chemokine receptors CCR2 and CX3CR1, resulting in decreased recruitment of eosinophils and macrophages to the lung. Deletion of FOXM1 from dendritic cells impaired the uptake of HDM antigens and decreased cell surface expression of major histocompatibility complex II (MHC II) and costimulatory molecule CD86, decreasing production of Th2 cytokines by activated T cells. Finally, pharmacological inhibition of FOXM1 by ARF peptide prevented HDM-mediated pulmonary responses. FOXM1 regulates genes critical for allergen-induced lung inflammation and goblet cell metaplasia.

INTRODUCTION

Asthma is one of the most common chronic respiratory diseases, affecting approximately 300 million individuals worldwide and representing a significant and growing cause of morbidity, mortality, and health care cost. Asthma is characterized by persistent pulmonary inflammation, goblet cell metaplasia, airway hyperresponsiveness, and lung remodeling (1). Eosinophilic inflammation and aberrant activation of T cells by pulmonary dendritic cell are important components in asthma pathogenesis. Cytokines/chemokines, including interleukin 4 (IL-4), IL-5, IL-13, IL-9, IL-17, IL-25, IL-33, and eotaxins, are produced by various resident and inflammatory cells in response to allergens that contribute to the pathogenesis of asthma (2–4). New therapeutic approaches are needed to improve patient care and reduce health care costs related to asthma.

Increased mucus production by goblet cells is a key feature in asthma and other chronic respiratory disorders, including chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), cystic fibrosis, and interstitial lung diseases (5, 6). In response to allergen stimulation, goblet cells differentiate from nonciliated epithelial cells in peripheral airways or basal cells in cartilaginous airways and trachea (7–9). Signaling pathways and transcriptional networks that control goblet cell differentiation have been increasingly studied. These include JAK/STAT-6, Notch, epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK), and NF-κB (8, 10–12). Notch signaling induces goblet cell metaplasia during lung development and lung injury (8). In response to allergen stimulation in mouse models, IL-4 receptor/STAT-6 signaling induces differentiation of goblet cells from Clara cells through upregulation of SPDEF and inhibition of TTF-1 and FOXA2 transcription factors (13). In the mouse, transgenic expression of SPDEF in Clara cells is sufficient to induce their differentiation into goblet cells, whereas Spdef−/− mice lack airway goblet cells (13, 14). SPDEF induces expression of various goblet cell genes, including Muc5ac, Muc16, Foxa3, Agr2, and glycosyltransferase genes, that regulate mucus production associated with acquisition of the goblet cell phenotype (14). While SPDEF is both necessary and sufficient for differentiation of goblet cells, upstream regulators of SPDEF remain poorly understood.

FOXM1 (previously known as HFH-11B, Trident, Win, or MPP2) is a member of the Forkhead box (FOX) family of transcription factors that share homology in the Winged Helix/Forkhead DNA binding domain (15, 16). Targeted deletion of the Foxm1 gene in mice (Foxm1−/−) is embryonic lethal due to multiple abnormalities in the development of the lung, liver, heart, and blood vessels (17–20). FOXM1 inactivation in cycling cells caused delays in DNA replication and mitosis, and altered expression of cell cycle regulatory genes (20–23). Consistent with an important role of FOXM1 in cell cycle progression, FOXM1 induced proliferation of tumor cells during development of lung, liver, brain, and prostate cancers (21, 24–27). Likewise, FOXM1 accelerated cellular proliferation during acute lung and liver injuries (28, 29).

While FOXM1 is an important regulator of cellular proliferation, a number of cell cycle-independent functions of FOXM1 were recently described (30). Depending on cell/tissue specificity, FOXM1 induces surfactant production by type II alveolar epithelial cells (31), increases differentiation of type I epithelial cells (32), regulates expression of tight junction proteins in endothelial cells (33, 34), and increases macrophage recruitment after liver injury (35). Deletion of Foxm1 from embryonic lung epithelium causes respiratory failure after birth (31), whereas deletion of Foxm1 from alveolar type II cells of adult mice impairs alveolar barrier repair after acute lung injury (32). Although these studies demonstrated that FOXM1 is a critical transcriptional regulator of alveolar epithelial cells, the role of FOXM1 in the airway epithelium remains unknown. Herein, we demonstrate that house dust mite allergen (HDM) increases FOXM1 expression in airway epithelium and inflammatory cells. We used genetic and pharmacological approaches to inhibit FOXM1 and identify molecular mechanisms by which FOXM1 influences pulmonary allergic responses.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mouse strains.

Generation of a Foxm1flox/flox (Foxm1fl/fl) mouse line, which contains LoxP sequences flanking DNA binding and transcriptional activation domains of the Foxm1 gene (exons 4 to 7), was previously described (19). The Foxm1fl/fl mice were bred with CCSP–rtTAtg/−/Otet-Cretg/tg mice (line 2) (14) to generate CCSP–rtTAtg/−/Otet-Cretg/−/Foxm1fl/fl mice (CCSP-Foxm1fl/fl). Foxm1 deletion from Clara cells was achieved by doxycycline (Dox; 625 mg/kg; Harlan Teklad, Madison, WI), which was administered to mice in their food (36). Controls included CCSP-Foxm1fl/fl mice without Dox, Dox-treated Foxm1fl/fl littermates, and mice expressing Cre alone (Dox-treated CCSP–rtTAtg/−/Otet-Cretg/−/Foxm1wt/wt mice). LysM-Cretg/− Foxm1fl/fl mice were generated and described previously (35). Transgenic mice were maintained in a C57BL/6 genetic background. LysM-Cre deletes Foxm1 in cells of myeloid lineage (37) as well as in a subset of alveolar type II cells (38).

Allergen stimulation and treatment with ARF peptide.

Animal studies were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee, and human studies were approved by the institutional review board (IRB) of Cincinnati Children's Hospital Research Foundation. Ovalbumin (OVA) was given intraperitoneally (i.p.) on days 0, 7, and 14 (100 μg of OVA mixed with 1 mg of aluminum hydroxide) followed by two intranasal treatments of OVA (50 μg) or saline on days 24 and 27 as described previously (39, 40). HDM extract (50 μg diluted in saline; Greer Laboratories) was given intratracheally (i.t.) on days 0 and 14. Twenty-four hours after the last HDM or OVA challenge, lungs were harvested and used for bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) collection, paraffin embedding, and preparation of RNA. The following enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kits were used to measure mouse cytokines and chemokines in BALF: IL-4, IL-5, IL-13, IL-12p70, and CCL2 (all from eBioscience), and eotaxin (Abcam). Airway resistance was assessed on tracheostomized 8-week-old mice using a computerized FlexiVent system (SCIREQ, Montreal, Canada) as described previously (41). Methacholine was delivered using an Aeroneb nebulizer (SCIREQ).

For pharmacological inhibition of FOXM1, we synthesized the (d-Arg)9-ARF(26–44) peptide containing a fluorescent tetramethylrhodamine (TMR) tag and nine N-terminal d-Arg residues to enhance the cellular uptake (21, 42). Eight-week-old BALB/c mice were subjected to i.t. administration of HDM on days 0 and 14. ARF peptide or control mutant peptide (21, 42) was administered i.t. on days 13 and 15 (1 mg/kg of body weight, diluted in saline). Forty-eight hours after the last peptide treatment, mice were sacrificed.

Immunohistochemical staining.

Lungs were inflated, fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, and embedded in paraffin blocks. Five-μm sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) or Alcian blue or used for immunohistochemistry as described previously (26, 31, 43). The following antibodies were used for immunostaining: FOXM1 (1:1,000, K-19, sc500; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), Cre recombinase (1:15,000, 69050-3; Novagen), Clara cell-secreted protein (CCSP; 1:2,000, WRAB-CCSP; Seven Hill Bioreagents), Ki-67 (1:500, clone Tec-3; Dako), PH3 (1:500, sc8656r; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), FOXA2 (1:4,000, WRAB-FoxA2; Seven Hills Bioreagents); FOXA3 (1:200, sc5361; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), β-tubulin (1:100, MU178-UC, BioGenex), SPDEF (1:2,000; generated in the lab of J. A. Whitsett [14]), MUC5AC (1:100, 45M1, ab3649; Abcam), alpha-smooth muscle actin (αSMA, 1:10,000, clone A5228; Sigma), and proSP-C (1:2,000) (31). Antibody-antigen complexes were detected using biotinylated secondary antibody followed by avidin-biotin-horseradish peroxidase complex (ABC), and 3,3′-diaminobenzidine (DAB) substrate (all from Vector Lab). Sections were counterstained with nuclear fast red (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA). For colocalization experiments, secondary antibodies conjugated with Alexa Fluor 488 or Alexa Fluor 594 (Invitrogen/Molecular Probes) were used as previously described (43, 44). Slides were counterstained with DAPI (4′,6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole; Vector Lab). Fluorescent images were obtained using a Zeiss Axioplan2 microscope equipped with an Axiocam MRm digital camera and Axiovision 4.3 software (Carl Zeiss Microimaging, Thornwood, NY).

Flow cytometry.

Inflammatory cells were prepared from lung tissue of HDM-treated LysM-Cre Foxm1fl/fl and control Foxm1fl/fl mice as described previously (45). Briefly, lungs were perfused with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), removed, gently minced with scissors, and then placed in RPMI 1640 medium containing Liberase (37.5 μg/ml; Roche Diagnostics) and DNase I (0.5 mg/ml, Sigma) for 40 min at 37°C in a CO2 incubator. After digestion, lung tissue was forced through a 40-μm cell strainer. Red blood cells were lysed with ammonium-chloride-potassium (ACK) lysis buffer (Invitrogen).

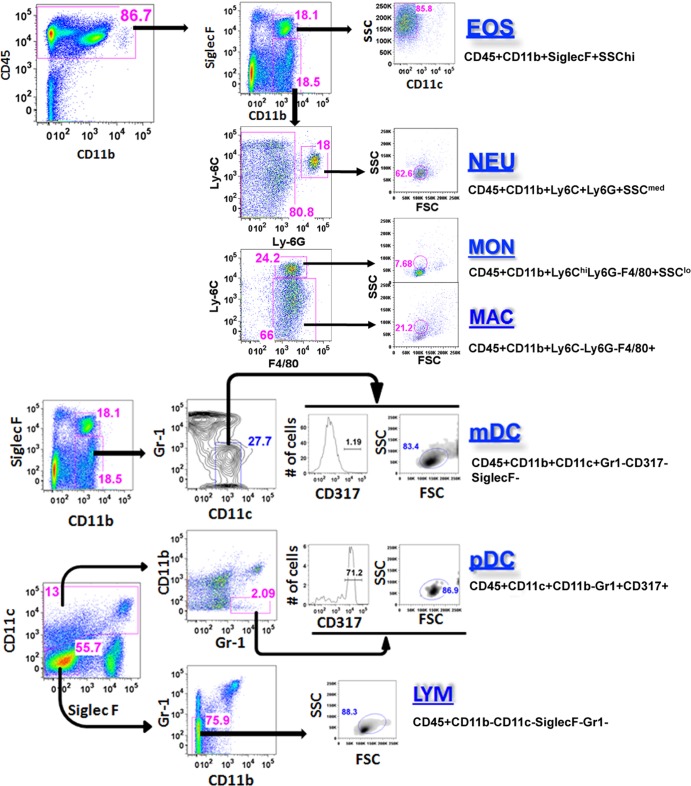

Inflammatory cells were stained with fluorescently labeled antibodies against CD11b, CD45, Ly-6C, Ly-6G, F4/80, SiglecF, Gr-1, CD11c, CD317, major histocompatibility complex II (MHC II), and CD86 as previously described (35, 46). Staining was performed at 4°C following incubation with Fc-Block (anti-mouse CD16/32, clone 93; eBiosciences, San Diego, CA) for 30 min. Following antibodies were used: anti-F4/80 (clone BM8; eBiosciences), anti-CD11b (clone M1/70; eBiosciences), anti-Ly-6C (clone HK1.4; BioLegend, San Diego, CA), anti-Ly-6G (clone 1A8; BioLegend), anti-CD86 (clone PO3; BioLegend), anti-CD317 (clone eBio927, eBiosciences), anti-MHC II (clone M5/114.15.2; eBiosciences), anti-CD11c (clone N418; eBiosciences), anti-SiglecF (clone E50-2440; BD Pharmingen), anti-Gr1 (RB6-8C5; eBiosciences), and anti-CD45 (clone 30-F11; BD Pharmingen). Dead cells were excluded using 7-aminoactinomycin (7-AAD) stain (eBiosciences). Stained cells were separated using cell sorting (five-laser FACSAria II; BD Biosciences). The following specific cell subsets were identified by using the indicated surface marker phenotypes: eosinophils, CD45+ CD11b+ CD11c− SiglecF+; neutrophils, CD45+ CD11b+ Ly6C+ Ly6G+; macrophages, CD45+ CD11b+ Ly6C− Ly6G− F4 80+; monocytes, CD45+ CD11b+ Ly6Chi Ly6G− F4 80+; myeloid dendritic cells (mDC), CD45+ CD11b+ CD11c+ Gr1− CD317− SiglecF−; and plasmacytoid dendritic cells (pDC), CD45+ CD11b− CD11c+ Gr1+ CD317+. Purified cells were used for RNA preparation and cell culture.

Coculture of mDCs and T cells.

mDC were isolated from lung tissue of HDM-treated mice, restimulated in vitro with 15 μg/ml of HDM labeled with IRD700 (Licor), and then cocultured with CD4+ T cells purified from spleens of HDM-treated wild-type (WT) mice (5 T cells/1 mDC). After 5 days in culture, cells were used for fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) analysis to examine IRD700, MHC II, and CD86 in dendritic cells. ELISA was used to measure IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13 in culture media.

Quantitative real-time RT-PCR (qRT-PCR).

RNA was prepared from whole lung tissue, FACS-sorted inflammatory cells, and epithelial cells isolated by laser capture microdissection. The Veritas microdissecting system (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA) was used for the laser capture microdissection of frozen lung sections as described previously (44). A StepOnePlus real-time PCR system (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) was used as described previously (31, 47). Samples were amplified with TaqMan gene expression master mix (Applied Biosystems) combined with inventoried TaqMan gene expression assays for the gene of interest (Table 1). Reactions were analyzed in triplicate. Expression levels were normalized to β-actin mRNA.

Table 1.

TaqMan primers for qRT-PCRs

| Mouse gene in TaqMan expression assay | Catalog no. |

|---|---|

| foxm1 | Mm01184444_g1 |

| beta-actin | Mm00607939_s1 |

| ccl2 | Mm99999056_m1 |

| ccl3 | Mm00441259_g1 |

| ccl4 | Mm00443111_m1 |

| ccl5 | Mm01302427_m1 |

| ccl11 | Mm00441238_m1 |

| ccl17 | Mm01244826_g1 |

| ccl24 | Mm00444701_m1 |

| ccr2 | Mm00438270_m1 |

| ccr3 | Mm00515543_s1 |

| cx3cl1 | Mm00436454_m1 |

| cx3cr1 | Mm02620111_s1 |

| foxa2 | Mm00839704_mH |

| foxa3 | Mm00484714_m1 |

| gm-csf | Mm01290062_m1 |

| gm-csfra | Mm00438331_g1 |

| il-1a | Mm99999060_m1 |

| il-1b | Mm01336189_m1 |

| il-4 | Mm00445260_m1 |

| il-5 | Mm00439646_m1 |

| il-6 | Mm01210733_m1 |

| il-10 | Mm99999062_m1 |

| il-12p35 | Mm00434165_m1 |

| il-13 | Mm00434205_g1 |

| il-33 | Mm00505403_m1 |

| ltc4s | Mm00521864_m1 |

| mcl-1 | Mm00725832_s1 |

| muc5ac | Mm01276725_g1 |

| ptgs2 | Mm00478374_m1 |

| sox-2 | Mm00488369_s1 |

| Spdef | Mm00600221_m1 |

| Integrin aM | Mm01271259_g1 |

| tnfa | Mm00443258_m1 |

Cotransfection studies.

U2OS cells were transfected with either cytomegalovirus (CMV)-FoxM1b or control empty CMV plasmids, as well as with a luciferase (LUC) reporter driven by the 2.8-kb mouse Spdef promoter (13, 14). The 2.8-kb mouse Spdef promoter was subcloned into the pGL3-LUC vector. CMV-Renilla was used as an internal control to normalize transfection efficiency. A dual LUC assay (Promega) was performed as described previously (31).

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assays.

ChIP assays were performed using in situ cross-linked human bronchial epithelial Beas-2B cells as described previously (31, 48, 49). Rabbit anti-Foxm1 antibodies (Abs) (C-20; Santa Cruz) and control rabbit IgG (Vector Lab) were used for ChIP. Promoter DNA was amplified using sense and antisense primers shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Primers for ChIP assays

| Primera | Sequence |

|---|---|

| hSPDEF (S) | CCTGCAAGGGTTAATCAGGAGCCT |

| hSPDEF (AS) | GCAGTGTGGACACGGCAGAGTGCA |

| hCCL24 (S) | GACCTCTCATTGTCTGTTACACAC |

| hCCL24 (AS) | CTGAGCCTCAGTTACTTCAGCTG |

| hCCL11 (S) | TTGGTCTACTCTACTTCATTGCTGA |

| hCCL11 (AS) | AACCTCAGTGGCTCAGTGGAA |

S, sense; AS, antisense.

Statistical analysis.

Post hoc analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used for multiple-group comparison. For comparison between two groups, Student's t test was used to determine statistical significance. P values of ≤0.05 were considered significant. Values for all measurements were expressed as means ± standard deviations (SD).

RESULTS

Pulmonary FOXM1 expression is increased after allergen stimulation.

Two mouse models of allergic airway diseases were used to assess the expression of FOXM1 after allergen stimulation, including treatment with OVA and house dust mite extract (HDM). Although FOXM1 was not detected in lungs of mice treated with saline, FOXM1 was induced in subsets of bronchiolar epithelial cells and inflammatory cells in each of the mouse models of experimental asthma (Fig. 1A). Increases in FOXM1 staining and Foxm1 mRNA were observed 24 to 72 h after final HDM treatment (Fig. 1A and B). Consistent with data from mouse lung tissue, FOXM1 staining was increased in bronchiolar epithelium and inflammatory cells of patients with severe asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) (Fig. 1D). In contrast, FOXM1-expressing cells were rarely seen in normal human lungs (Fig. 1D) Thus, allergen stimulation induced FOXM1 expression in mouse and human lungs.

Fig 1.

FOXM1 is increased after allergen stimulation. (A) FOXM1 is increased in mouse models of asthma. Paraffin sections were prepared from lungs of WT BALB/c mice 24 and 72 h after the last HDM challenge or 48 h after the last OVA challenge. Five mice were used in each group. Lung sections were stained with FOXM1 Abs (dark brown) and counterstained with nuclear fast red (red). FOXM1 staining is increased in airway epithelial cells and inflammatory cells after OVA or HDM treatment. FOXM1 was not found in WT mice treated with saline (left panels). (B) qRT-PCR of total lung RNAs shows increased expression of Foxm1 at different time points. Data are means ± standard errors of the means (SEM) (n = 5 mice/group; *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01). (C) HDM induces FOXM1 in myeloid cells. Lung tissue was harvested from WT mice 48 h after the last HDM challenge. Cells were purified using flow cytometry-based cell sorting. Cell surface markers are shown in Fig. 2. Foxm1 mRNA was detected in various types of inflammatory cells by qRT-PCR. Foxm1 mRNA was not detected in eosinophils. (D) FOXM1 staining in lungs of patients with asthma and COPD. FOXM1 staining was increased in airway epithelium (arrows), peribronchial regions, and cells located within the lumen (arrowheads) in patients with COPD and asthma but not in control lungs (n = 5). (E and F) FOXM1 (red) colocalized with CCSP (green) in HDM-treated airway epithelium of WT mice (E) and asthmatic human lungs (F). FOXM1 is also found in subsets of MUC5AC-positive goblet cells from mouse and human lungs. Abbreviations: Br, bronchiole; Ve, vessel. Bars, 50 μm (A and D) and 10 μm (E and F).

To identify airway epithelial cells expressing FOXM1 in response to HDM challenge, colocalization experiments were performed. The majority of FOXM1-positive cells expressed the Clara cell-secreted protein (CCSP) (Fig. 1E), a marker of Clara cells. FOXM1 was also found in goblet cells expressing low levels of MUC5AC, whereas FOXM1 was absent from goblet cells expressing high levels of MUC5AC (Fig. 1E). FOXM1 was also found in subsets of Clara and goblet cells from patients with severe asthma (Fig. 1F). To identify inflammatory cells expressing FOXM1 after allergen stimulation, cells were isolated from lungs of HDM-treated mice and purified by flow cytometry-based cell sorting (Fig. 2). High levels of Foxm1 mRNA were found in neutrophils, monocytes and macrophages from HDM-treated lungs, whereas myeloid dendritic cells (mDCs) and lymphocytes expressed low levels of Foxm1 mRNA (Fig. 1C). Foxm1 mRNA was undetectable in eosinophils (Fig. 1C). FOXM1 protein and mRNA were absent from airway epithelial and myeloid cells of saline-treated mice (Fig. 1A and data not shown), indicating that HDM treatment was required to induce FOXM1 expression in the lung.

Fig 2.

Identification and purification of inflammatory cells from HDM-challenged lung tissue. Inflammatory cells were isolated from either LysM-Cre Foxm1fl/fl or control Foxm1fl/fl lungs. Flow cytometry was used to identify myeloid inflammatory cells. The cell surface marker phenotypes used were as follows: eosinophils, CD45+ CD11b+ CD11c− SiglecF+ SSChi; neutrophils, CD45+ CD11b+ Ly6G+ Ly6C+ SSCmed; monocytes, CD45+ CD11b+ Ly6G− Ly6Chi F4 80+ SSClo; macrophages, CD45+ CD11b+ Ly6G− Ly6C− F4 80+; myeloid dendritic cells (mDCs), autofluorescencelo CD45+ CD11b+ CD11c+ Gr1− CD317−; plasmacytoid dendritic cells (pDCs), autofluorescencelo CD45+ CD11b− CD11c+ Gr1+ CD317+; lymphocytes, CD45+ CD11b− CD11c− Gr1− SiglecF−. Cells were used for either RNA isolation or cell culture experiments.

Conditional deletion of FOXM1 from myeloid cells.

To determine the role of FOXM1 in myeloid cells after allergen exposure, LysM-Cre Foxm1fl/fl mice were used. The LysM-Cre Foxm1fl/fl mice contain LoxP-flanked Foxm1-floxed alleles (Foxm1fl/fl) (19) and the LysM-Cre transgene (37), mediating a conditional deletion of exons 4 to 7, which encode DNA-binding and C-terminal transcriptional activation domains of the FOXM1 protein (19). LysM-Cre deletes Foxm1 in cells of myeloid lineage, including macrophages, monocytes, DCs, and granulocytes (37), and in a subset of alveolar type II cells (38). In untreated LysM-Cre Foxm1fl/fl mice, lung structure and cell counts in bone marrow and peripheral blood were unaltered (33, 35). To assess requirements for FOXM1 in the asthma model, LysM-Cre Foxm1fl/fl and control Foxm1fl/fl mice were subjected to the HDM sensitization/challenge protocol.

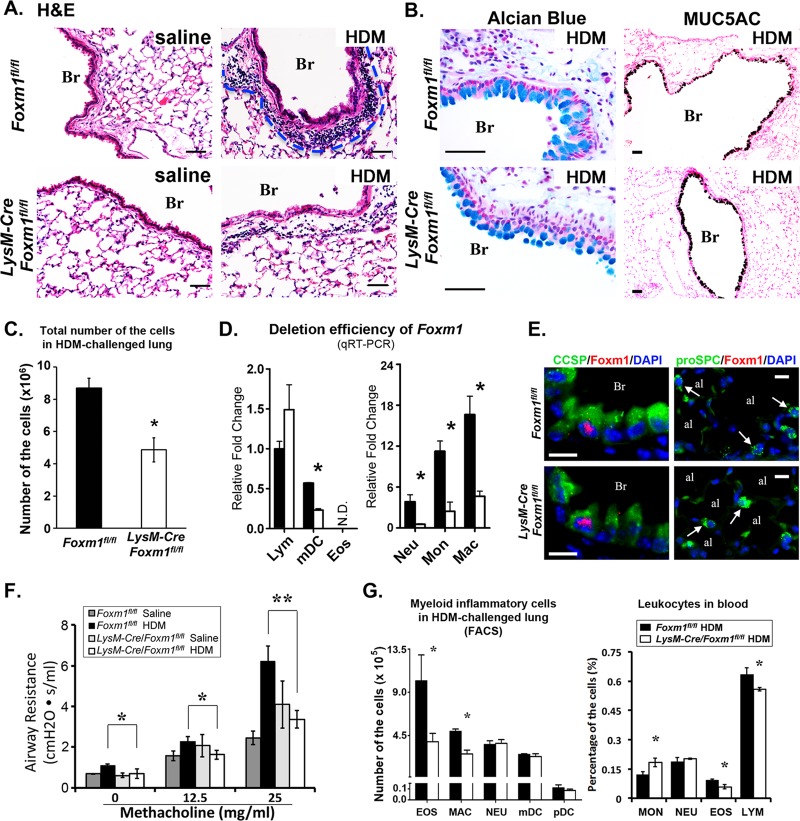

To address the efficiency of FOXM1 deletion, inflammatory cells were isolated from lungs of LysM-Cre Foxm1fl/fl and control Foxm1fl/fl mice 48 h after the last HDM challenge. A 70 to 90% reduction in Foxm1 mRNA was observed in monocytes, macrophages, mDCs, and neutrophils obtained from LysM-Cre Foxm1fl/fl mice, whereas Foxm1 mRNA in lymphocytes was unchanged (Fig. 3D), a finding consistent with efficient deletion of Foxm1 from myeloid cells (37). FOXM1 was present in a subset of Clara cells but absent from alveolar type II cells of HDM-treated LysM-Cre Foxm1fl/fl and control lungs (Fig. 3E).

Fig 3.

Deletion of FOXM1 from myeloid cells decreased airway resistance and lung inflammation after HDM challenge. (A and B) Pulmonary inflammation was assessed in LysM-Cre Foxm1fl/fl mice after HDM treatment. Control Foxm1fl/fl and LysM-Cre Foxm1fl/fl mice were treated with HDM or saline and harvested 72 h after the last challenge. H&E staining shows decreased peribronchial inflammation in HDM-treated LysM-Cre Foxm1fl/fl mice (A). The number of inflammatory cells was counted in 10 random sections using 5 mice in each group (C). A P value of <0.05 is shown with an asterisk. Alcian blue staining and immunostaining for MUC5AC were similar in HDM-treated Foxm1fl/fl and LysM-Cre Foxm1fl/fl lungs (B). (D) Efficiency of Foxm1 deletion in myeloid cells. Cells were purified from lungs of HDM-treated Foxm1fl/fl and LysM-Cre Foxm1fl/fl mice by flow cytometry (see Fig. 2 for cell surface markers) and used for qRT-PCR. Foxm1 mRNA was decreased in macrophages, monocytes, neutrophils, and mDCs of HDM-treated LysM-Cre Foxm1fl/fl mice. Six mice were used in each group. (E) Colocalization experiments show the presence of FOXM1 in a subset of CCSP-positive Clara cells (left panels). FOXM1 is not expressed in proSPC-positive type II cells (right panels). (F) Decreased airway resistance in HDM-treated LysM-Cre Foxm1fl/fl mice. FlexiVent was used to measure airway resistance in 8 to 10 mice in each group. (G) Leukocyte counts in HDM-treated LysM-Cre Foxm1fl/fl mice. Flow cytometry was used to determine the number of various inflammatory subsets using cell surface markers described in Fig. 2. Eosinophils and macrophages were decreased in lung tissue of HDM-treated LysM-Cre Foxm1fl/fl mice (left). In peripheral blood, percentages of eosinophils and lymphocytes were significantly reduced, but the percentage of circulating monocytes was increased after deletion of FOXM1 (right). Five mice were used in each group. Abbreviations: Br, bronchiole; al, alveoli. Bars, 50 μm (A and B) and 10 μm (E).

Deletion of FOXM1 from myeloid cells reduced pulmonary inflammation and airway resistance after HDM challenge.

Consistent with previous studies (50, 51), HDM exposure induced goblet cell metaplasia in pulmonary airways and caused inflammation in interstitial tissue surrounding airways and pulmonary blood vessels (Fig. 3A and B). While goblet cell metaplasia was similar in control Foxm1fl/fl and LysM-Cre Foxm1fl/fl mice (Fig. 3B), total number of inflammatory cells was lower in LysM-Cre Foxm1fl/fl lungs (Fig. 3A and C). Numbers of eosinophils and macrophages were decreased in lung tissue of HDM-treated LysM-Cre Foxm1fl/fl mice, whereas numbers of neutrophils and mDCs were unchanged (Fig. 3G, left). In peripheral blood of HDM-treated LysM-Cre Foxm1fl/fl mice, percentages of eosinophils and lymphocytes were significantly reduced but the percentage of circulating monocytes was increased (Fig. 3G, right), a finding consistent with decreased migration and maturation of FOXM1-deficient monocytes from peripheral blood into injured liver (35). Consistent with decreased pulmonary inflammation in HDM-treated LysM-Cre Foxm1fl/fl mice, airway resistance after methacholine treatment was significantly decreased (Fig. 3F).

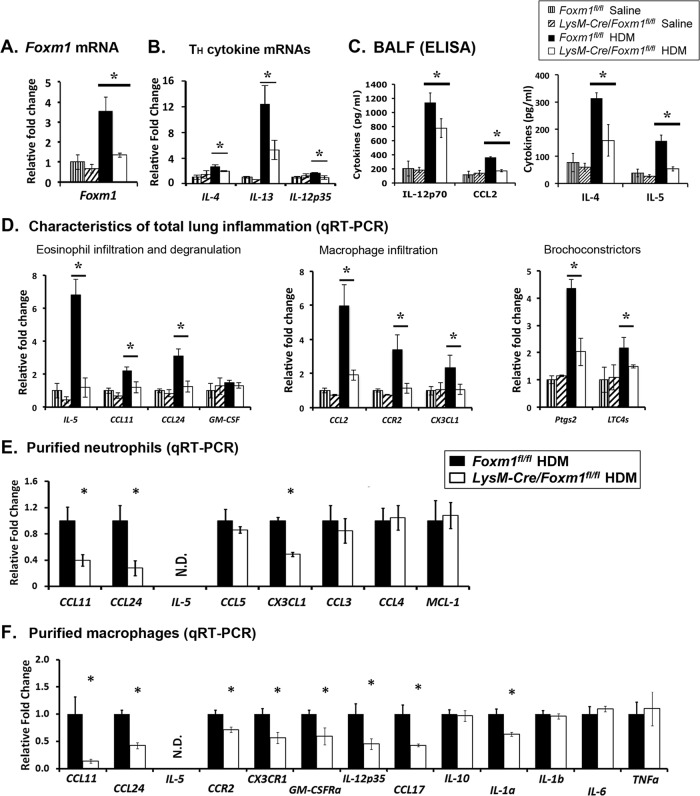

Total lung RNA was used to identify genes regulated by FOXM1 in response to HDM stimulation. Foxm1 mRNA was increased in HDM-treated Foxm1fl/fl lungs but not in LysM-Cre Foxm1fl/fl lungs (Fig. 4A). Consistent with the loss of Foxm1, Ccr2 mRNA, a known FOXM1 target (35), was significantly decreased (Fig. 4D). While granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) mRNA was not changed, mRNAs of IL-4, IL-13, IL-12, IL-5, Ccl11 (eotaxin-1), Ccl24 (eotaxin-2), Ccl2, Cx3cl1, Ptgs2, and Ltc4s, all critical for recruitment of inflammatory cells and airway hyperreactivity after allergen stimulation (52–55), were reduced in HDM-treated LysM-Cre Foxm1fl/fl lungs (Fig. 4B and D). Protein levels of IL-4, IL-5, CCL2, and IL-12p70 were decreased in BALF of HDM-treated LysM-Cre Foxm1fl/fl mice, as demonstrated by ELISA (Fig. 4C). Expression of proinflammatory genes was also examined in purified neutrophils and macrophages isolated from HDM-treated lungs. In both cell types, decreased Foxm1 mRNA was associated with reduced Ccl11 and Ccl24 (Fig. 4E and F), findings consistent with decreased numbers of eosinophils (Fig. 3G). Cx3cl1 mRNA was decreased in FOXM1-deficient neutrophils (Fig. 4E), whereas Cx3cr1, Ccr2, GM-CSFrα, IL-1α, IL-12p35 and Ccl17 mRNAs were reduced in FOXM1-deficient macrophages (Fig. 4F). The loss of FOXM1 did not influence IL-1β, IL-6, tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), IL-10, CCL3, CCL4, or Mcl-1 mRNAs (Fig. 4E and F). Thus, deletion of FOXM1 altered expression of proinflammatory genes in neutrophils and macrophages, possibly contributing to decreased lung inflammation and reduced airway resistance after HDM challenge.

Fig 4.

Deletion of Foxm1 in myeloid cells reduced lung inflammation and decreased expression of proinflammatory genes after HDM treatment. Lung tissue and BALF were obtained from Foxm1fl/fl and LysM-Cre Foxm1fl/fl mice 72 h after the last HDM challenge. (A and B) qRT-PCR shows decreased mRNAs of Foxm1, IL-4, IL-13, and IL-12p32 in whole lung tissue from HDM-treated LysM-Cre Foxm1fl/fl mice. (C) ELISA shows decreased IL-4, IL-5, CCL2, and IL-12p70 proteins in BALF of HDM-treated LysM-Cre Foxm1fl/fl mice. (D) Gene expression profile in LysM-Cre Foxm1fl/fl lungs. qRT-PCR was used to quantitate mRNAs of various inflammatory mediators in total lung tissue (5 mice in each group). (E and F) qRT-PCR shows mRNAs of inflammatory mediators in purified neutrophils (E) and macrophages (F). Cells were isolated from HDM-treated lungs (n = 5) by cell sorting (see Fig. 2 for cell surface markers). *, P < 0.05. N.D., not detected.

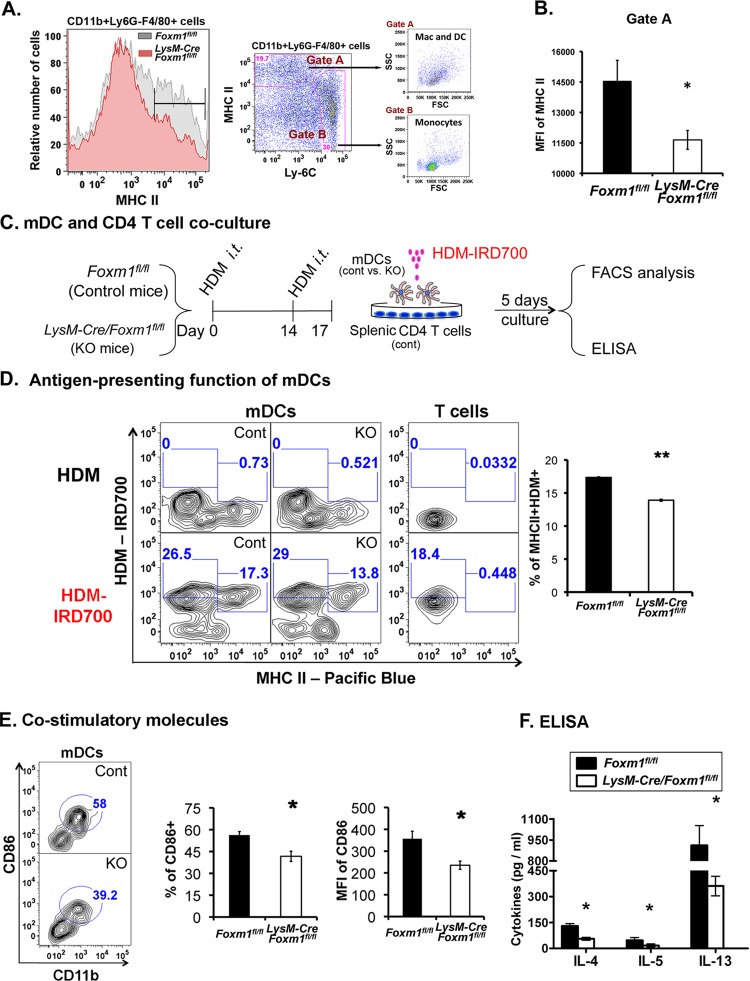

Impaired T cell activation in FOXM1-deficient mDCs.

Total numbers of myeloid and plasmacytoid DCs were not altered in HDM-treated LysM-Cre Foxm1fl/fl lungs (Fig. 3G). However, reduced Th2 cytokines IL-5, IL-4, and IL-13 in the lungs and BALF of these mice (Fig. 4B and C) are consistent with impaired function of antigen-presenting cells, resulting in decreased activation of T cells. Cell surface expression of MHC II, a receptor critical for antigen presentation and T-cell activation, was examined in antigen-presenting cells from HDM-treated lungs. Mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of MHC II was decreased in antigen-presenting myeloid cells (macrophages and DC) from LysM-Cre Foxm1fl/fl lungs (Fig. 5A and B). To examine antigen presentation in vitro, mDCs were purified from HDM-sensitized LysM-Cre Foxm1fl/fl or Foxm1fl/fl lungs, restimulated with fluorescently labeled HDM antigens in vitro, and cultured with splenic CD4+ T cells from HDM-treated Foxm1fl/fl mice (Fig. 5C). The percentage of MHC II+ HDM+ mDCs was decreased after the loss of FOXM1 (Fig. 5D). FOXM1-deficient mDCs exhibited diminished cell surface expression of CD86 (B7.2) (Fig. 5E), a costimulatory molecule important for activation of T cells (56, 57). The percentage of CD86+ mDCs was also reduced (Fig. 5E). Finally, the T-cell-produced cytokines IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13 were decreased in supernatants from cell cultures containing FOXM1-deficient mDCs (Fig. 5F), a result consistent with decreased activation of T cells. Thus, deletion of FOXM1 from mDCs resulted in decreased cell surface expression of MHC II and CD86 and reduced activation of T cells in response to HDM in vitro and in vivo. Altogether, our results demonstrate that expression of FOXM1 in myeloid cells is critical for lung inflammation after allergen stimulation.

Fig 5.

Decreased cell surface expression of MHC II and CD86 in LysM-Cre Foxm1fl/fl mDCs. (A and B) Impaired MHC class II expression on the surfaces of FOXM1-deficient antigen-presenting cells after HDM sensitization in vivo. Antigen-presenting cells were purified from lung tissue of Foxm1fl/fl and LysM-Cre Foxm1fl/fl mice 72 h after the last HDM challenge. The mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of MHC II was determined by flow cytometry. Five mice were used in each group. *, P < 0.05. (C to F), Decreased activation of T cells by LysM-Cre Foxm1fl/fl mDCs in vitro. A schematic shows experimental design of coculture of pulmonary mDCs with splenic CD4+ T cells (C). Pulmonary mDCs and splenic Foxm1fl/fl CD4+ T cells were isolated from HDM-sensitized mice, restimulated with infrared dye 700 (IRD700)-labeled HDM antigens in vitro, and cultured for 5 days (5 T cells/1 mDC). Uptake of IRD700-labeled HDM and cell surface expression of MHC II were measured by flow cytometry in 5 independent cell cultures (D). The percentage of MHC II+ HDM+ mDCs was lower in LysM-Cre Foxm1fl/fl mDCs (D, right). The percentage of CD86-positive mDCs and MFI of CD86 were reduced in LysM-Cre Foxm1fl/fl mDCs (E). ELISA was used to examine concentrations of IL-4, IL-5 and IL-13 in the culture supernatants (F). *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01.

FOXM1 deletion from Clara cells reduced pulmonary inflammation and decreased airway resistance after HDM challenge.

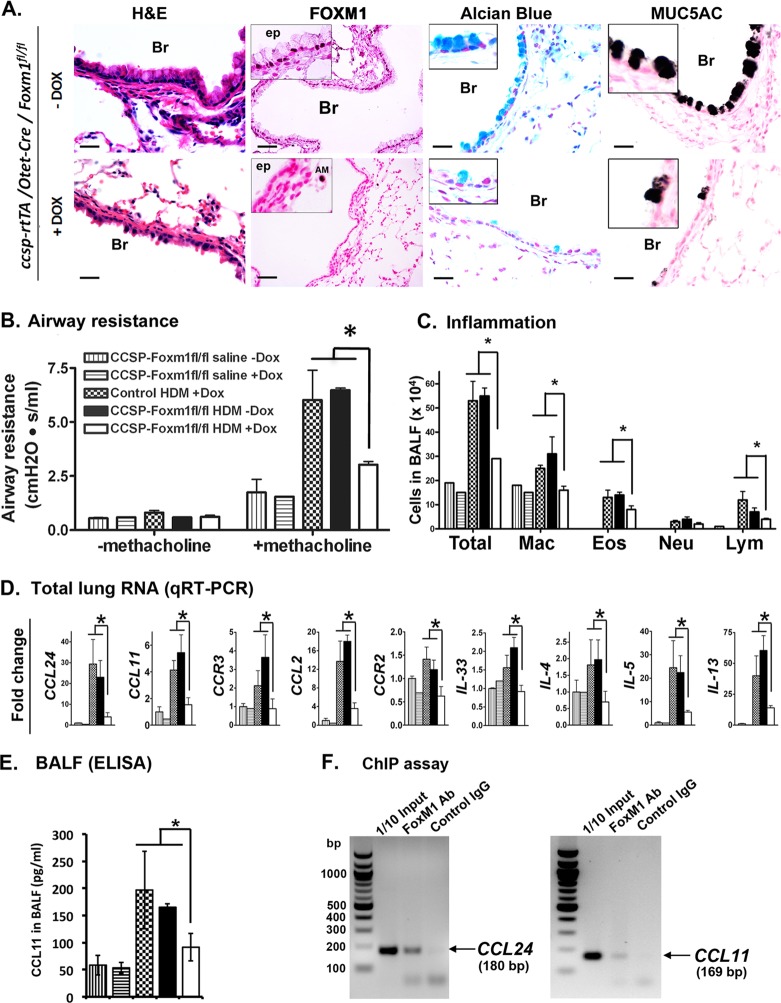

FOXM1 is increased in airway epithelial cells of asthma patients and mice treated with OVA and HDM (Fig. 1). To determine the role of FOXM1 in airway epithelial cells after allergen exposure, triple-transgenic mice containing Foxm1fl/fl, the Scgb1a1 (CCSP)–rtTAtg/− and the Otet-Cretg/− transgenes (CCSP–rtTAtg/−/Otet-Cretg/−/Foxm1fl/fl or CCSP-Foxm1−/− mice) were produced. To induce Cre expression in airway epithelial cells, doxycycline (Dox) was given 5 days after sensitization with HDM. In the presence of Dox, the reverse tetracycline transactivator (rtTA) binds to the TetO promoter and induces expression of Cre recombinase, deleting DNA binding and transcriptional activation domains of the FOXM1 protein (49). Specific loss of FOXM1 protein from airway epithelium of CCSP-Foxm1−/− mice was shown by immunostaining (Fig. 6A). In response to HDM, airway resistance in CCSP-Foxm1−/− mice was reduced compared to controls (Dox-treated Foxm1fl/fl mice and CCSP-Foxm1fl/fl mice without Dox) (Fig. 6B). FOXM1 deletion from Clara cells reduced pulmonary inflammation in response to HDM, as shown by decreased numbers of inflammatory cells in BALF (Fig. 6C), and reduced mRNA and protein levels of eotaxins, IL-4, IL-5, IL-13, IL-33, Ccl2, Ccr2, and Ccr3 in lung tissue (Fig. 6D and E). FOXM1 specifically bound to promoter regions of eotaxin genes (Ccl11 and Ccl24) as demonstrated by ChIP assay (Fig. 6F). Reduced expression of proinflammatory mediators can contribute to decreased inflammation in HDM-treated CCSP-Foxm1−/− mice. Thus, FOXM1 deletion from airway epithelium inhibits pulmonary inflammation and decreases airway resistance after HDM challenge.

Fig 6.

Deletion of Foxm1 in Clara cells prevented goblet cell metaplasia in response to HDM. (A) Decreased goblet cell metaplasia in HDM-treated CCSP-Foxm1−/− mice. Lungs were harvested 72 h after the last HDM challenge. FOXM1 staining is absent in airway epithelium (ep) of Dox-treated CCSP-Foxm1−/− mice, while FOXM1 is detectable in alveolar macrophages (AM). FOXM1 is present in airway epithelium of mice without Dox (controls). Decreased numbers of goblet cells in Dox-treated CCSP-Foxm1−/− mice are shown by H&E staining, Alcian blue staining, and immunostaining for MUC5AC. Bars, 50 μm. (B) Decreased airway resistance in HDM-treated CCSP-Foxm1−/− mice (7 to 12 mice in each group). The methacholine concentration was 6 mg/ml. (C) The number of inflammatory cells was decreased in BALF of CCSP-Foxm1−/− mice compared to controls. BALF was collected 72 h after the last HDM challenge. Five hundred cells were counted to determine the percentage of the cells (5 mice in each group). (D) Decreased mRNAs of proinflammatory genes in CCSP-Foxm1−/− mice. Total lung RNA was prepared 48 h after the last HDM challenge and examined by qRT-PCR. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01. (E) ELISA shows decreased CCL11 protein in BALF of HDM-treated LysM-Cre Foxm1fl/fl mice. (F) ChIP assay was performed in BEAS-2B cells. Endogenous FOXM1 protein specifically binds to the promoter regions of Ccl11 and Ccl24 genes (F).

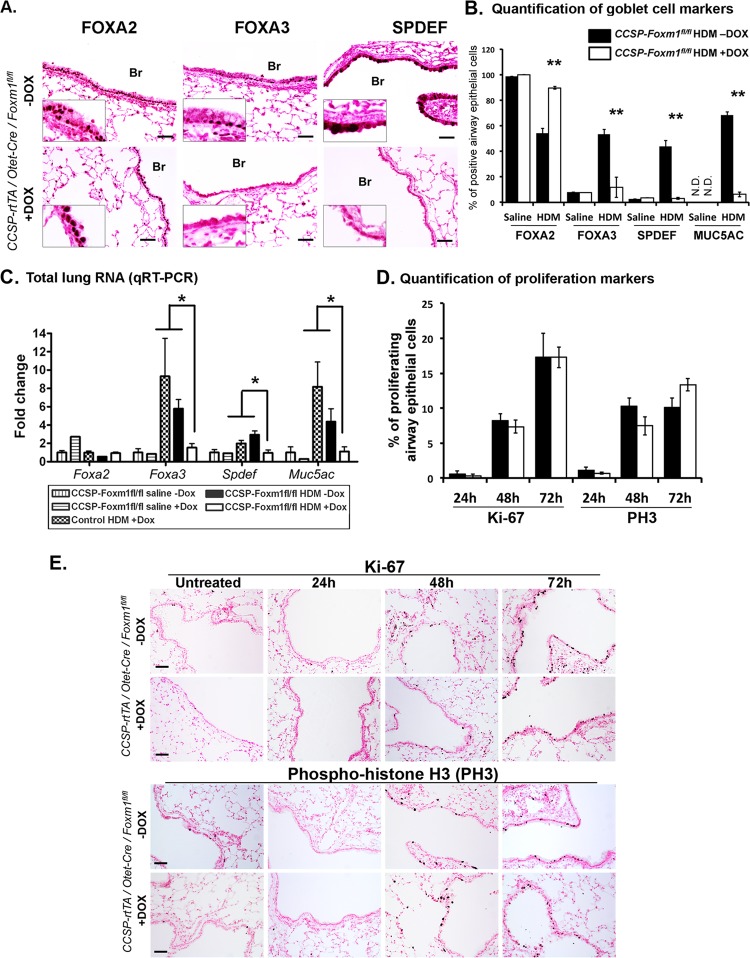

FOXM1 deletion decreased goblet cell metaplasia in airway epithelium.

Decreased numbers of goblet cells were observed in airway epithelium of HDM-treated CCSP-Foxm1−/− mice (Fig. 6A). Decreased staining and mRNAs of Spdef and Foxa3, transcriptional regulators associated with goblet cell metaplasia (14), were consistent with reduced differentiation of goblet cells in CCSP-Foxm1−/− lungs (Fig. 7A to C). The number of FOXA2-positive cells was increased in HDM-treated CCSP-Foxm1−/− lungs (Fig. 7B). FOXM1 colocalized with SPDEF in airway epithelium of HDM-treated mice, whereas the loss of FOXM1 prevented SPDEF expression (Fig. 8A). In cotransfection experiments, CMV-FoxM1b expression vector induced promoter activity of Spdef (Fig. 8D). ChIP assay demonstrated that endogenous FOXM1 protein specifically bound to the Spdef promoter (Fig. 8E), indicating that Spdef is a direct transcriptional target of FOXM1. Staining for proliferation-specific Ki-67 and PH3 showed no differences in proliferation of airway epithelial cells between CCSP-Foxm1−/− and control lungs (Fig. 7D and E), suggesting a cell cycle-independent function of FOXM1 in formation of goblet cell metaplasia. Interestingly, time course studies demonstrated that FOXM1 was induced prior to SPDEF but was decreased following upregulation of SPDEF (Fig. 8B), suggesting a negative feedback mechanism by which Spdef and Foxm1 interact. Consistent with these results, Foxm1 mRNA was increased in airway epithelium obtained by laser capture microdissection from HDM-treated Spdef−/− lungs (Fig. 8C). Although the loss of SPDEF did not influence Sox2 mRNA, expression of Foxa3 was decreased (Fig. 8C), a result consistent with previous studies (14). Altogether, our results demonstrated an important role for FOXM1 in regulation of transcriptional network critical for differentiation of goblet cells in the mouse asthma models.

Fig 7.

Decreased expression of SPDEF, FOXA3, and MUC5AC in FOXM1-deficient airway epithelium. (A to C) Mice were sacrificed and lungs were harvested 72 h after the last HDM challenge. SPDEF and FOXA3 are decreased in lung sections from HDM-treated CCSP-Foxm1−/− mice. The number of goblet cells (B) and levels of mRNAs of Spdef, Foxa3, and Muc5ac are decreased in whole lung tissue of HDM-treated CCSP-Foxm1−/− mice (C). mRNA levels were determined by qRT-PCR. (D and E) Cellular proliferation is not affected in HDM-treated CCSP-Foxm1−/− mice. Proliferating cells were visualized using Abs against Ki-67 and PH3 (E). The number of proliferating cells is unaltered after deletion of FOXM1 (D). Ten random Ki-67-stained sections from 5 mice were counted for each group. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01. Br, bronchiole. Bars, 50 μm.

Fig 8.

FOXM1 is required for induction of SPDEF. (A) FOXM1 coexpressed with SPDEF in airway epithelial cells of HDM-treated mice. CCSP-Foxm1−/− and control mice were treated with HDM and harvested 24 h after the last HDM challenge. FOXM1 (red) colocalizes with SPDEF (green) in epithelial cells of control lungs (−Dox; top) but not in CCSP-Foxm1−/− mice (+Dox; bottom). (B) FOXM1 is decreased in SPDEF-positive goblet cells at 72 h after the last HDM challenge (yellow arrows). FOXM1 expression is maintained in Clara cells (white arrows). HDM-treated WT mice were used for immunostaining. Br, bronchiole. (C) Increased Foxm1 mRNA in airway epithelial cells from Spdef−/− mice. RT-PCR shows the absence of Spdef mRNA in Spdef−/− lungs (bottom). Laser-capture microdissection of airway epithelial cells was performed 24 h after the last HDM treatment. Foxm1, Sox2, and Foxa3 mRNAs were measured in microdissected epithelial cells by qRT-PCR (top). (D and E) SPDEF is a direct transcriptional target of FOXM1. CMV-FoxM1b plasmid induced LUC activity driven by Spdef promoter after cotransfection in U2OS cells. CMV-empty plasmid was used as a control. Endogenous FOXM1 protein specifically binds to the promoter region of Spdef gene, as demonstrated by a ChIP assay (E). Bars, 20 μm.

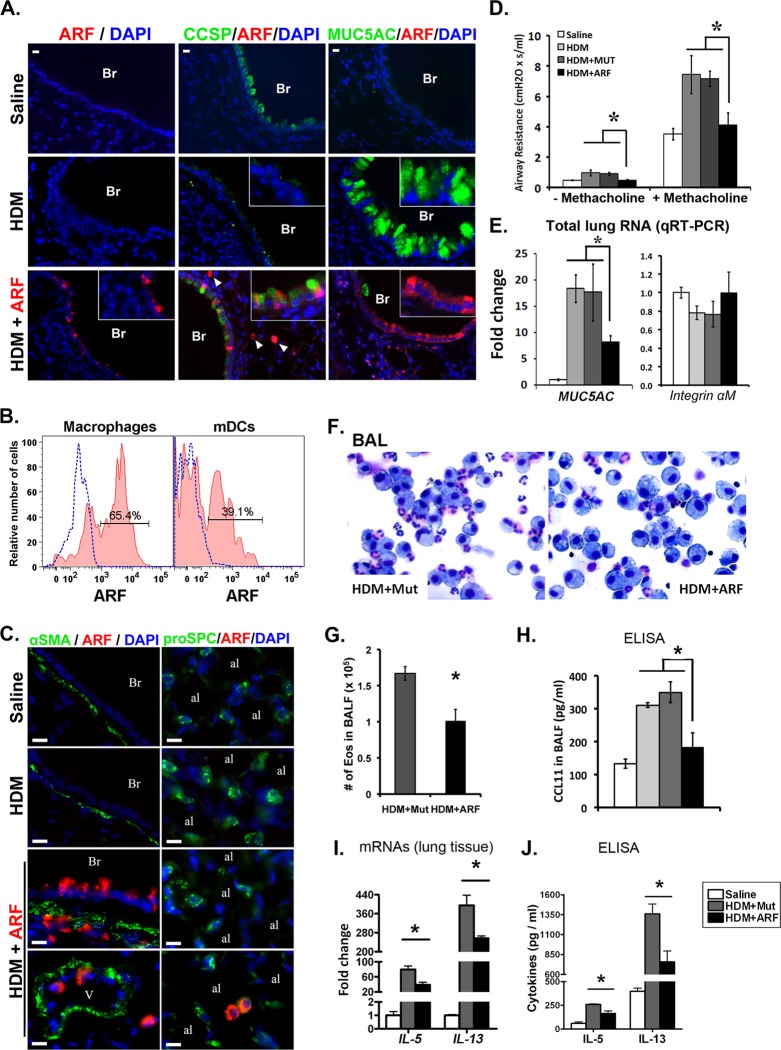

Pharmacological inhibition of FOXM1 decreased pulmonary inflammation and goblet cell metaplasia in response to HDM.

Since genetic deletion of Foxm1 from either airway epithelium or inflammatory cells protected the lung from HDM-induced inflammation (Fig. 3 to 6), we tested whether pharmacological inactivation of FOXM1 influenced the pathogenesis of the asthma-like phenotype. Previous studies demonstrated that a membrane-penetrating ARF peptide specifically binds the FOXM1 protein and inhibits FOXM1 transcriptional activity in vitro and in vivo (21, 42, 58). The ARF peptide, containing a fluorescent tetramethylrhodamine (TMR) tag and nine N-terminal d-Arg residues to enhance cellular uptake (21, 42), was administered into the tracheas of HDM-treated WT mice on days 13 and 15. TMR-labeled mutant ARF peptide, which does not bind the FOXM1 protein (21), was used as a control. TMR fluorescence was detected in airway epithelium (Fig. 9A), inflammatory cells (Fig. 9C), and peribronchial interstitium (Fig. 9C), indicating that the ARF peptide was effectively delivered to pulmonary airways in vivo. Flow cytometry demonstrated that 65.4% ± 3.5% of pulmonary macrophages and 39.1% ± 9.7% of mDCs contained TMR-labeled ARF peptide (Fig. 9B). In the alveolar region, TMR fluorescence was detected in a subset of macrophages but not in alveolar type II cells (Fig. 9C). Airway resistance was significantly decreased in ARF-treated mice compared to controls (Fig. 9D). Goblet cell metaplasia was reduced, as indicated by decreased MUC5AC protein and mRNA (Fig. 9A and E) and increased CCSP staining in ARF peptide-treated airways (Fig. 9A). The ARF peptide decreased the number of eosinophils in BALF (Fig. 9F and G) and reduced IL-5, IL-13, and CCL11 proteins and mRNAs (Fig. 9H to J), findings consistent with reduced pulmonary inflammation. Protein levels of CCL2 were unaltered (Fig. 9H). Altogether, inhibition of FOXM1 by the ARF peptide protected the lung from goblet cell metaplasia and pulmonary inflammation induced by HDM exposure.

Fig 9.

Inhibition of FOXM1 by ARF peptide prevents goblet cell metaplasia and reduced airway resistance. (A to C) ARF peptide inhibited airway resistance in HDM-treated mice. BALB/c mice were subjected to intratracheal administration of HDM on days 0 and 14. ARF peptide or mutated ARF peptide (Mut) was given on days 13 and 15. Mice were sacrificed on day 16. ARF peptide reduced the number of MUC5AC-positive goblet cells and increased the number of CCSP-positive Clara cells (A). TMR fluorescence (red) shows the presence of ARF peptide in airway epithelium (A, insets), inflammatory cells (A, arrowheads; C, bottom) and peribronchial smooth muscle (C) of HDM-treated lungs. Flow cytometry shows TMR fluorescence in pulmonary macrophages and mDCs (B). (D) Airway resistance was decreased in ARF-treated mice compared to controls (7 mice per group). Concentration of methacholine was 6 mg/ml. (E) qRT-PCR shows a reduction in Muc5ac mRNA in ARF-treated lungs. Integrin αM mRNA was not changed. (F and G) ARF peptide decreased the number and the percentage of eosinophils in BALF. Five hundred cells were counted to calculate the percentage of eosinophils (5 mice in each group). (H to J) IL-5, IL-13, and CCL11 were measured in BALF by ELISA (H and J) and in total lung RNA by qRT-PCR (I). *, P < 0.05. Br, bronchiole; Ve, vessel; al, alveoli. Bars, 20 μm (A) and 10 μm (C).

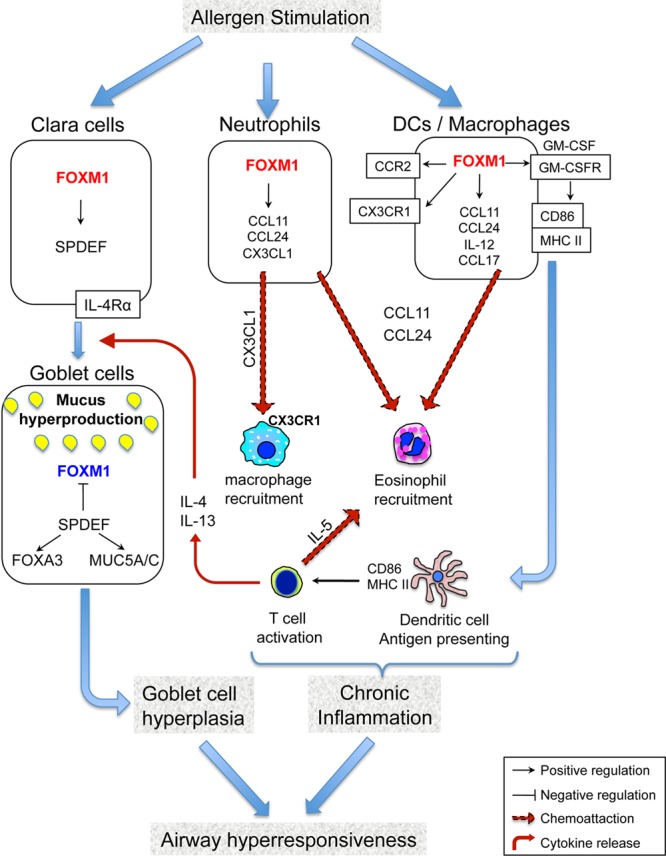

DISCUSSION

Chronic airway diseases, including asthma, COPD, cystic fibrosis (CF), and interstitial lung disease are associated with significant morbidity, mortality, and health care costs worldwide. In the present study, we demonstrated the essential role of FOXM1 transcription factor in inducing lung inflammation and goblet cell metaplasia in response to allergen exposure and Th2 stimulation (Fig. 10). Pharmacological targeting of FOXM1 and its effectors provides a novel therapeutic strategy to prevent goblet cell metaplasia and pulmonary inflammation in chronic lung disease.

Fig 10.

Model of FOXM1-induced goblet cell metaplasia and allergen-mediated lung inflammation. FOXM1 induces differentiation of Clara cells into goblet cells through direct transcriptional activation of Spdef. SPDEF inhibits FOXM1 in differentiated goblet cells. FOXM1 increases the cell surface expression of MHC II and CD86 in mDCs, leading to increased activation of T cells and increased production of IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13. FOXM1 recruits eosinophils and macrophages into the lung tissue, at least in part, by activating eotaxins, CCR2, CX3CR1, IL-5, and CX3CL1.

FOXM1 promotes allergen-induced lung inflammation.

In this study, we found that FOXM1 induces expression of proinflammatory genes in myeloid cells, a finding consistent with an important role of FOXM1 in allergen-induced lung inflammation. Previous studies demonstrated that FOXM1 induces transcriptional activity of Ccr2 and Cx3cr1 (33, 35), encoding chemokine receptors critical for recruitment of macrophages to injured tissues (59–61). CCR2 and CX3CR1 were decreased in FOXM1-deficient macrophages after CCl4-mediated liver injury (35) and butylated hydroxytoluene (BHT)-mediated lung injury (33). Consistent with these previous studies, Ccr2 and Cx3cr1 mRNAs were reduced in FOXM1-deficient macrophages in an HDM model, implicating FOXM1 in the regulation of these genes during allergen-mediated lung inflammation. Loss of FOXM1 was associated with decreases in GM-CSFRα and IL-1α, both of which mediate macrophage maturation, migration, and survival (52, 62). Thus, FOXM1 may play a cell-autonomous role in macrophage recruitment to the lung tissue after allergen exposure (Fig. 10).

Specialized populations of DC are critical for antigen presentation and T-cell activation during the pathogenesis of asthma in mice and humans (63, 64). In the present study, FOXM1 was found in mDCs. Reduced Th2 cytokines in lungs of LysM-Cre Foxm1fl/fl mice suggest impaired mDC function in response to allergen stimulation, resulting in decreased activation of T cells. Since MHC II cell surface expression was reduced in FOXM1-deficient mDC, antigen presentation may be impaired by the deletion of FOXM1. In addition to the antigenic signal, FOXM1 may influence T-cell activation by inducing expression of CD86, a molecule providing second costimulatory signal to T cells (56, 57). Diminished activation of T cells by DCs may contribute to decreased lung inflammation in LysM-Cre Foxm1fl/fl mice (Fig. 10).

Although eosinophils do not express FOXM1, reduced numbers of eosinophils were found in HDM-treated LysM-Cre Foxm1fl/fl lungs, a finding associated with decreased IL-5 and eotaxins. Since eotaxins are produced by various cells types, FOXM1 may play an indirect or non-cell-autonomous role in eosinophilic recruitment in response to allergen stimulation. The findings that both eotaxin 1 and eotaxin 2 are reduced in FOXM1-deficient macrophages and neutrophils and that FOXM1 bound to eotaxin promoters suggest a direct regulation of eotaxin genes by FOXM1. Since IL-5 is produced by activated T cells (65), reduced T-cell activation by FOXM1-deficient DCs may contribute to reduced IL-5 levels and diminished eosinophilic inflammation in LysM-Cre Foxm1fl/fl lungs (Fig. 10). Although HDM stimulation increased FOXM1 expression in neutrophils, their numbers were not altered by the deletion of FOXM1. These data suggest that FOXM1 is dispensable for recruitment of neutrophils to the lung tissue in HDM model, a finding consistent with previous studies showing the FOXM1-independent recruitment of neutrophils after CCl4-mediated liver injury (35).

Interestingly, inflammatory cells and proinflammatory cytokines were reduced after deletion of FOXM1 from airway epithelial cells. Published studies demonstrated that in response to allergen stimulation airway epithelial cells produce proinflammatory chemokines, such as CCL2 (MCP1), eotaxin-1 (CCL11) and eotaxin-2 (CCL24), that are critical for recruitment of macrophages and eosinophils to the lung (52, 54, 65). Therefore, decreased expression of these proinflammatory mediators can contribute to decreased inflammation in HDM-treated CCSP-Foxm1−/− mice. In addition, decreased numbers of macrophages in HDM-treated CCSP-Foxm1−/− lungs may lead to an impairment in antigen presentation and T cell activation, resulting in decreased production of Th2 cytokines and contributing to diminished airway resistance. Altogether, our results support the concept that FOXM1 induces allergen-mediated lung inflammation through both cell-autonomous and non-cell-autonomous mechanisms.

FOXM1 induces goblet cell metaplasia after Th2 stimulation.

Goblet cell metaplasia is a prominent feature of asthma, yet there is incomplete knowledge of transcriptional programs that influence airway epithelial cell differentiation leading to the accumulation of goblet cells, and increased mucus production in asthmatic airways. In the present study, we found that FOXM1 influences goblet cell metaplasia through multiple mechanisms. First, FOXM1 increases antigen presentation by DCs, leading to increased production of IL-4 and IL-13 by activated T cells. IL-4 and IL-13, acting through multiple signaling pathways, including IL-4R receptors/Stat-6, induce goblet cell differentiation in response to various allergens (66–69). Thus, diminished T-cell activation and the reduction of IL-4 and IL-13 in HDM model may impair goblet cell differentiation, leading to decreased goblet cell metaplasia in FOXM1-deficient airways. Second, we found that FOXM1 directly induces goblet cell metaplasia through transcriptional activation of Spdef, a critical regulator of mucus production and goblet cell differentiation. SPDEF transcription factor is both necessary and sufficient to induce goblet cell differentiation in mice and is induced in goblet cells in lungs of individuals with asthma, COPD, and CF (13, 14). Transgenic expression of SPDEF in Clara cells induced their differentiation into goblet cells, whereas genetic ablation of Spdef gene prevented goblet cell metaplasia after Th2 stimulation (13, 14). SPDEF induces goblet cell differentiation in association with the expression of Foxa3, Muc5ac, and Arg2 and reduction of expression of genes associated with Clara cell phenotype, including Ttf1 and Foxa2 (13). In the present study, genetic deletion of Foxm1 was sufficient to decrease SPDEF in airway epithelial cells. Thus, reduced levels of SPDEF may contribute to attenuated goblet cell metaplasia in FOXM1-deficient airways. Interestingly, expression of FOXM1 was significantly decreased after upregulation of SPDEF in airway epithelium, suggesting a negative feedback mechanism by which SPDEF can counterregulate FOXM1. Consistent with the inhibitory effect of SPDEF on FOXM1, airway epithelial cells of Spdef−/− mice exhibited increased Foxm1 mRNA after HDM exposure. Taken together, present findings demonstrate that FOXM1 regulates signaling and transcriptional networks critical for differentiation of goblet cells in response to allergen exposure (Fig. 10).

Pharmacological inhibition of FOXM1 is a promising therapeutic approach in asthma treatment.

The present study demonstrated that inhibition of FOXM1 by ARF peptide or genetic inactivation of Foxm1 gene reduces the severity of lung responses to HDM. The ARF peptide effectively inhibited both goblet cell metaplasia and eosinophilic inflammation, decreasing airway resistance in HDM-treated mice. Previous studies showed that a membrane-penetrating ARF peptide specifically binds to FOXM1 with high affinity, sequestering the ARF peptide/FOXM1 complex inside the cell and inhibiting FOXM1 transcriptional activity (21, 42, 58). In the present study, we found that the ARF peptide decreased IL-5, IL-13, and CCL11 after HDM stimulation, findings consistent with reduced expression of these genes in FOXM1-deficient mice. Inhibition of FOXM1 in inflammatory cells may account for decreased levels of proinflammatory cytokines and reduced airway resistance in response to HDM. These results also suggest that pharmacological inhibition of FOXM1 may be beneficial for treatment of asthma in human patients. Although increased permeability and disruption of alveolar barriers were found in mice with a conditional inactivation of Foxm1 from either endothelial cells (70) or alveolar type II cells (32), we did not observe pulmonary edema and lung inflammation in the alveolar regions of ARF-treated mice. In the present study, ARF peptide accumulates in airway epithelial cells, peribronchial interstitium, and macrophages, causing local inhibition of FOXM1 in HDM-treated airways.

In summary, FOXM1 was required for the induction of goblet cell metaplasia, mediated in part via direct transcriptional activation of Spdef. FOXM1 promoted antigen presentation by increasing the cell surface expression of MHC II and CD86 in dendritic cells, causing activation of T cells and increased production of Th2 cytokines. FOXM1 induces recruitment of eosinophils and macrophages by activating eotaxins, IL-5, CCR2, and CX3CR1. Altogether, FOXM1 is critical for goblet cell metaplasia and lung inflammation in response to allergen stimulation.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Craig Bolte for helpful comments, Li Yang and J. Snyder for technical assistance, and Ann Maher for secretarial support.

This work was supported by NIH grants HL84151 (to V.V.K.), CA142724 (to T.V.K.) HL095580, and U01-HL110964 and by the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation Research Development Program (to J.A.W.).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 12 November 2012

REFERENCES

- 1. Ober C, Yao TC. 2011. The genetics of asthma and allergic disease: a 21st century perspective. Immunol. Rev. 242:10–30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Herrick CA, Bottomly K. 2003. To respond or not to respond: T cells in allergic asthma. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 3:405–412 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Saenz SA, Noti M, Artis D. 2010. Innate immune cell populations function as initiators and effectors in Th2 cytokine responses. Trends Immunol. 31:407–413 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Smith DE. 2010. IL-33: a tissue derived cytokine pathway involved in allergic inflammation and asthma. Clin. Exp. Allergy 40:200–208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Warburton D, El-Hashash A, Carraro G, Tiozzo C, Sala F, Rogers O, De Langhe S, Kemp PJ, Riccardi D, Torday J, Bellusci S, Shi W, Lubkin SR, Jesudason E. 2010. Lung organogenesis. Curr. Top. Dev. Biol. 90:73–158 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Whitsett JA, Wert SE, Trapnell BC. 2004. Genetic disorders influencing lung formation and function at birth. Hum. Mol. Genet. 13(Spec no 2):R207–R215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Rawlins EL, Okubo T, Xue Y, Brass DM, Auten RL, Hasegawa H, Wang F, Hogan BL. 2009. The role of Scgb1a1+ Clara cells in the long-term maintenance and repair of lung airway, but not alveolar, epithelium. Cell Stem Cell 4:525–534 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Rock JR, Gao X, Xue Y, Randell SH, Kong YY, Hogan BL. 2011. Notch-dependent differentiation of adult airway basal stem cells. Cell Stem Cell 8:639–648 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Rock JR, Onaitis MW, Rawlins EL, Lu Y, Clark CP, Xue Y, Randell SH, Hogan BL. 2009. Basal cells as stem cells of the mouse trachea and human airway epithelium. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 106:12771–12775 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Doherty T, Broide D. 2007. Cytokines and growth factors in airway remodeling in asthma. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 19:676–680 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Tyner JW, Kim EY, Ide K, Pelletier MR, Roswit WT, Morton JD, Battaile JT, Patel AC, Patterson GA, Castro M, Spoor MS, You Y, Brody SL, Holtzman MJ. 2006. Blocking airway mucous cell metaplasia by inhibiting EGFR antiapoptosis and IL-13 transdifferentiation signals. J. Clin. Invest. 116:309–321 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Wills-Karp M. 2004. Interleukin-13 in asthma pathogenesis. Immunol. Rev. 202:175–190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Park KS, Korfhagen TR, Bruno MD, Kitzmiller JA, Wan H, Wert SE, Khurana Hershey GK, Chen G, Whitsett JA. 2007. SPDEF regulates goblet cell hyperplasia in the airway epithelium. J. Clin. Invest. 117:978–988 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Chen G, Korfhagen TR, Xu Y, Kitzmiller J, Wert SE, Maeda Y, Gregorieff A, Clevers H, Whitsett JA. 2009. SPDEF is required for mouse pulmonary goblet cell differentiation and regulates a network of genes associated with mucus production. J. Clin. Invest. 119:2914–2924 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Clark KL, Halay ED, Lai E, Burley SK. 1993. Co-crystal structure of the HNF-3/fork head DNA-recognition motif resembles histone H5. Nature 364:412–420 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kim IM, Zhou Y, Ramakrishna S, Hughes DE, Solway J, Costa RH, Kalinichenko VV. 2005. Functional characterization of evolutionary conserved DNA regions in forkhead box f1 gene locus. J. Biol. Chem. 280:37908–37916 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kim IM, Ramakrishna S, Gusarova GA, Yoder HM, Costa RH, Kalinichenko VV. 2005. The forkhead box M1 transcription factor is essential for embryonic development of pulmonary vasculature. J. Biol. Chem. 280:22278–22286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Korver W, Schilham MW, Moerer P, van den Hoff MJ, Dam K, Lamers WH, Medema RH, Clevers H. 1998. Uncoupling of S phase and mitosis in cardiomyocytes and hepatocytes lacking the winged-helix transcription factor trident. Curr. Biol. 8:1327–1330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Krupczak-Hollis K, Wang X, Kalinichenko VV, Gusarova GA, Wang I-C, Dennewitz MB, Yoder HM, Kiyokawa H, Kaestner KH, Costa RH. 2004. The mouse Forkhead Box m1 transcription factor is essential for hepatoblast mitosis and development of intrahepatic bile ducts and vessels during liver morphogenesis. Dev. Biol. 276:74–88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ramakrishna S, Kim IM, Petrovic V, Malin D, Wang IC, Kalin TV, Meliton L, Zhao YY, Ackerson T, Qin Y, Malik AB, Costa RH, Kalinichenko VV. 2007. Myocardium defects and ventricular hypoplasia in mice homozygous null for the Forkhead Box M1 transcription factor. Dev. Dyn. 236:1000–1013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kalinichenko VV, Major M, Wang X, Petrovic V, Kuechle J, Yoder HM, Shin B, Datta A, Raychaudhuri P, Costa RH. 2004. Forkhead Box m1b transcription factor is essential for development of hepatocellular carcinomas and is negatively regulated by the p19ARF tumor suppressor. Genes Dev. 18:830–850 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Major ML, Lepe R, Costa RH. 2004. Forkhead Box M1B (FoxM1B) transcriptional activity requires binding of Cdk/Cyclin complexes for phosphorylation-dependent recruitment of p300/CBP coactivators. Mol. Cell. Biol. 24:2649–2661 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Wang X, Kiyokawa H, Dennewitz MB, Costa RH. 2002. The Forkhead Box m1b transcription factor is essential for hepatocyte DNA replication and mitosis during mouse liver regeneration. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 99:16881–16886 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kalin TV, Wang IC, Ackerson TJ, Major ML, Detrisac CJ, Kalinichenko VV, Lyubimov A, Costa RH. 2006. Increased levels of the FoxM1 transcription factor accelerate development and progression of prostate carcinomas in both TRAMP and LADY transgenic mice. Cancer Res. 66:1712–1720 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kim IM, Ackerson T, Ramakrishna S, Tretiakova M, Wang IC, Kalin TV, Major ML, Gusarova GA, Yoder HM, Costa RH, Kalinichenko VV. 2006. The Forkhead Box m1 transcription factor stimulates the proliferation of tumor cells during development of lung cancer. Cancer Res. 66:2153–2161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Wang IC, Meliton L, Ren X, Zhang Y, Balli D, Snyder J, Whitsett JA, Kalinichenko VV, Kalin TV. 2009. Deletion of Forkhead Box M1 transcription factor from respiratory epithelial cells inhibits pulmonary tumorigenesis. PLoS One 4:e6609 doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0006609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Zhang N, Wei P, Gong A, Chiu WT, Lee HT, Colman H, Huang H, Xue J, Liu M, Wang Y, Sawaya R, Xie K, Yung WK, Medema RH, He X, Huang S. 2011. FoxM1 promotes beta-catenin nuclear localization and controls Wnt target-gene expression and glioma tumorigenesis. Cancer Cell 20:427–442 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kalinichenko VV, Gusarova GA, Tan Y, Wang IC, Major ML, Wang X, Yoder HM, Costa RH. 2003. Ubiquitous expression of the forkhead box M1B transgene accelerates proliferation of distinct pulmonary cell-types following lung injury. J. Biol. Chem. 278:37888–37894 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Wang X, Hung N-J, Costa RH. 2001. Earlier expression of the transcription factor HFH 11B (FOXM1B) Diminishes Induction of p21CIP1/WAF1 levels and accelerates mouse hepatocyte entry into S-phase following carbon tetrachloride liver injury. Hepatology 33:1404–1414 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kalin TV, Ustiyan V, Kalinichenko VV. 2011. Multiple faces of FoxM1 transcription factor: lessons from transgenic mouse models. Cell Cycle 10:396–405 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kalin TV, Wang IC, Meliton L, Zhang Y, Wert SE, Ren X, Snyder J, Bell SM, Graf L, Jr, Whitsett JA, Kalinichenko VV. 2008. Forkhead Box m1 transcription factor is required for perinatal lung function. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 105:19330–19335 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Liu Y, Sadikot RT, Adami GR, Kalinichenko VV, Pendyala S, Natarajan V, Zhao YY, Malik AB. 2011. FoxM1 mediates the progenitor function of type II epithelial cells in repairing alveolar injury induced by Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Exp. Med. 208:1473–1484 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Balli D, Ren X, Chou FS, Cross E, Zhang Y, Kalinichenko VV, Kalin TV. 2012. Foxm1 transcription factor is required for macrophage migration during lung inflammation and tumor formation. Oncogene 31:3875–3888 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Mirza MK, Sun Y, Zhao YD, Potula HH, Frey RS, Vogel SM, Malik AB, Zhao YY. 2010. FoxM1 regulates re-annealing of endothelial adherens junctions through transcriptional control of beta-catenin expression. J. Exp. Med. 207:1675–1685 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Ren X, Zhang Y, Snyder J, Cross ER, Shah TA, Kalin TV, Kalinichenko VV. 2010. Forkhead box M1 transcription factor is required for macrophage recruitment during liver repair. Mol. Cell. Biol. 30:5381–5393 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Wang IC, Snyder J, Zhang Y, Lander J, Nakafuku Y, Lin J, Chen G, Kalin TV, Whitsett JA, Kalinichenko VV. 2012. Foxm1 mediates cross talk between Kras/mitogen-activated protein kinase and canonical Wnt pathways during development of respiratory epithelium. Mol. Cell. Biol. 32:3838–3850 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Clausen BE, Burkhardt C, Reith W, Renkawitz R, Forster I. 1999. Conditional gene targeting in macrophages and granulocytes using LysMcre mice. Transgenic Res. 8:265–277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Hume DA. 2011. Applications of myeloid-specific promoters in transgenic mice support in vivo imaging and functional genomics but do not support the concept of distinct macrophage and dendritic cell lineages or roles in immunity. J. Leukoc. Biol. 89:525–538 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Kalin TV, Meliton L, Meliton AY, Zhu X, Whitsett JA, Kalinichenko VV. 2008. Pulmonary mastocytosis and enhanced lung inflammation in mice heterozygous null for the Foxf1 gene. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 39:390–399 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Wan H, Kaestner KH, Ang SL, Ikegami M, Finkelman FD, Stahlman MT, Fulkerson PC, Rothenberg ME, Whitsett JA. 2004. Foxa2 regulates alveolarization and goblet cell hyperplasia. Development 131:953–964 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Xu Y, Saegusa C, Schehr A, Grant S, Whitsett JA, Ikegami M. 2009. C/EBPα is required for pulmonary cytoprotection during hyperoxia. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 297:L286–L298 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Gusarova GA, Wang IC, Major ML, Kalinichenko VV, Ackerson T, Petrovic V, Costa RH. 2007. A cell-penetrating ARF peptide inhibitor of FoxM1 in mouse hepatocellular carcinoma treatment. J. Clin. Invest. 117:99–111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Wang IC, Zhang Y, Snyder J, Sutherland MJ, Burhans MS, Shannon JM, Park HJ, Whitsett JA, Kalinichenko VV. 2010. Increased expression of FoxM1 transcription factor in respiratory epithelium inhibits lung sacculation and causes Clara cell hyperplasia. Dev. Biol. 347:301–314 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Ustiyan V, Wang IC, Ren X, Zhang Y, Snyder J, Xu Y, Wert SE, Lessard JL, Kalin TV, Kalinichenko VV. 2009. Forkhead box M1 transcriptional factor is required for smooth muscle cells during embryonic development of blood vessels and esophagus. Dev. Biol. 336:266–279 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Lewkowich IP, Herman NS, Schleifer KW, Dance MP, Chen BL, Dienger KM, Sproles AA, Shah JS, Kohl J, Belkaid Y, Wills-Karp M. 2005. CD4+CD25+ T cells protect against experimentally induced asthma and alter pulmonary dendritic cell phenotype and function. J. Exp. Med. 202:1549–1561 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Kalinichenko VV, Mokyr MB, Graf LH, Jr, Cohen RL, Chambers DA. 1999. Norepinephrine-mediated inhibition of antitumor cytotoxic T lymphocyte generation involves a beta-adrenergic receptor mechanism and decreased TNF-alpha gene expression. J. Immunol. 163:2492–2499 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Wang IC, Meliton L, Tretiakova M, Costa RH, Kalinichenko VV, Kalin TV. 2008. Transgenic expression of the forkhead box M1 transcription factor induces formation of lung tumors. Oncogene 27:4137–4149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Malin D, Kim IM, Boetticher E, Kalin TV, Ramakrishna S, Meliton L, Ustiyan V, Zhu X, Kalinichenko VV. 2007. Forkhead box F1 is essential for migration of mesenchymal cells and directly induces integrin-beta3 expression. Mol. Cell. Biol. 27:2486–2498 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Ustiyan V, Wert SE, Ikegami M, Wang IC, Kalin TV, Whitsett JA, Kalinichenko VV. 2012. Foxm1 transcription factor is critical for proliferation and differentiation of Clara cells during development of conducting airways. Dev. Biol. 370:198–212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Le Cras TD, Acciani TH, Mushaben EM, Kramer EL, Pastura PA, Hardie WD, Korfhagen TR, Sivaprasad U, Ericksen M, Gibson AM, Holtzman MJ, Whitsett JA, Hershey GK. 2011. Epithelial EGF receptor signaling mediates airway hyperreactivity and remodeling in a mouse model of chronic asthma. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 300:L414–L421 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Lewkowich IP, Lajoie S, Clark JR, Herman NS, Sproles AA, Wills-Karp M. 2008. Allergen uptake, activation, and IL-23 production by pulmonary myeloid DCs drives airway hyperresponsiveness in asthma-susceptible mice. PLoS One 3:e3879 doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0003879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Monteseirin J. 2009. Neutrophils and asthma. J. Investig. Allergol. Clin. Immunol. 19:340–354 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Perkins C, Wills-Karp M, Finkelman FD. 2006. IL-4 induces IL-13-independent allergic airway inflammation. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 118:410–419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Robays LJ, Maes T, Lebecque S, Lira SA, Kuziel WA, Brusselle GG, Joos GF, Vermaelen KV. 2007. Chemokine receptor CCR2 but not CCR5 or CCR6 mediates the increase in pulmonary dendritic cells during allergic airway inflammation. J. Immunol. 178:5305–5311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Varol C, Landsman L, Fogg DK, Greenshtein L, Gildor B, Margalit R, Kalchenko V, Geissmann F, Jung S. 2007. Monocytes give rise to mucosal, but not splenic, conventional dendritic cells. J. Exp. Med. 204:171–180 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Carreno BM, Collins M. 2002. The B7 family of ligands and its receptors: new pathways for costimulation and inhibition of immune responses. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 20:29–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Sharpe AH, Freeman GJ. 2002. The B7-CD28 superfamily. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2:116–126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Park HJ, Gusarova G, Wang Z, Carr JR, Li J, Kim KH, Qiu J, Park YD, Williamson PR, Hay N, Tyner AL, Lau LF, Costa RH, Raychaudhuri P. 2011. Deregulation of FoxM1b leads to tumour metastasis. EMBO Mol. Med. 3:21–34 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Holt MP, Cheng L, Ju C. 2008. Identification and characterization of infiltrating macrophages in acetaminophen-induced liver injury. J. Leukoc. Biol. 84:1410–1421 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Srivastava M, Jung S, Wilhelm J, Fink L, Buhling F, Welte T, Bohle RM, Seeger W, Lohmeyer J, Maus UA. 2005. The inflammatory versus constitutive trafficking of mononuclear phagocytes into the alveolar space of mice is associated with drastic changes in their gene expression profiles. J. Immunol. 175:1884–1893 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Zhang J, Patel JM. 2010. Role of the CX3CL1-CX3CR1 axis in chronic inflammatory lung diseases. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Med. 3:233–244 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Cates EC, Gajewska BU, Goncharova S, Alvarez D, Fattouh R, Coyle AJ, Gutierrez-Ramos JC, Jordana M. 2003. Effect of GM-CSF on immune, inflammatory, and clinical responses to ragweed in a novel mouse model of mucosal sensitization. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 111:1076–1086 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Hammad H, Plantinga M, Deswarte K, Pouliot P, Willart MA, Kool M, Muskens F, Lambrecht BN. 2010. Inflammatory dendritic cells—not basophils—are necessary and sufficient for induction of Th2 immunity to inhaled house dust mite allergen. J. Exp. Med. 207:2097–2111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Minnicozzi M, Sawyer RT, Fenton MJ. 2011. Innate immunity in allergic disease. Immunol. Rev. 242:106–127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Rothenberg ME, Hogan SP. 2006. The eosinophil. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 24:147–174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Fichtner-Feigl S, Strober W, Kawakami K, Puri RK, Kitani A. 2006. IL-13 signaling through the IL-13alpha2 receptor is involved in induction of TGF-beta1 production and fibrosis. Nat. Med. 12:99–106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Gavett SH, O'Hearn DJ, Karp CL, Patel EA, Schofield BH, Finkelman FD, Wills-Karp M. 1997. Interleukin-4 receptor blockade prevents airway responses induced by antigen challenge in mice. Am. J. Physiol. 272:L253–L261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Miloux B, Laurent P, Bonnin O, Lupker J, Caput D, Vita N, Ferrara P. 1997. Cloning of the human IL-13R alpha1 chain and reconstitution with the IL4R alpha of a functional IL-4/IL-13 receptor complex. FEBS Lett. 401:163–166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Tomkinson A, Duez C, Cieslewicz G, Pratt JC, Joetham A, Shanafelt MC, Gundel R, Gelfand EW. 2001. A murine IL-4 receptor antagonist that inhibits IL-4- and IL-13-induced responses prevents antigen-induced airway eosinophilia and airway hyperresponsiveness. J. Immunol. 166:5792–5800 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Zhao YY, Gao XP, Zhao YD, Mirza MK, Frey RS, Kalinichenko VV, Wang IC, Costa RH, Malik AB. 2006. Endothelial cell-restricted disruption of FoxM1 impairs endothelial repair following LPS-induced vascular injury. J. Clin. Invest. 116:2333–2343 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]