Abstract

Core binding factor beta (CBFβ), a transcription regulator through RUNX binding, was recently reported critical for Vif function. Here, we mapped the primary functional domain important for Vif function to amino acids 15 to 126 of CBFβ. We also revealed that different lengths and regions are required for CBFβ to assist Vif or RUNX. The important interaction domains that are uniquely required for Vif but not RUNX function represent novel targets for the development of HIV inhibitors.

TEXT

Core binding factor beta (CBFβ) regulates host genes specific to hematopoiesis and osteogenesis (1–3) by forming heterodimers with CBFα (i.e., RUNX). CBFβ does not function by binding DNA directly (1); instead, it greatly enhances the affinity of RUNX for DNA, specifically with the core binding sites of various promoters and enhancers (4), such as the macrophage colony-stimulating factor receptor (MCSFR) promoter (5). This enhancement would affect the transcription of various genes in human cells, resulting in the regulation of cell differentiation and proliferation (3, 6).

It has recently been shown by several research groups (7–11) that CBFβ is also a crucial determinant of the proper functioning of the viral infectivity factor (Vif) of HIV-1. HIV-1 Vif is necessary for viral survival in the host, since it serves to inactivate the host restriction factors (APOBEC3 proteins) present in HIV-1's natural target cells, including macrophages and CD4+ T cells (12–25). Vif hijacks the cellular Cullin5-ElonginB-ElonginC proteins to form a virus-specific E3 ubiquitin ligase complex (26) that targets APOBEC proteins (such as APOBEC3G [A3G]) for proteasomal degradation (26–35). However, Vif's contribution to A3G degradation is almost completely abolished when the expression of CBFβ is silenced (9, 10). Furthermore, mutations in Vif that disrupt CBFβ binding prevent Vif from suppressing the antiviral activity of A3G. CBFβ interacts specifically with HIV-1 Vif to uniquely control its interaction with Culllin5, but not with ElonginB/ElonginC or A3G. Both wild-type CBFβ (either isoform 1–182 or isoform 1–187) and C-terminal-truncated CBFβ (residues 1 to 140) interact with Vif in vitro, and Vif's solubility is greatly improved when it is coexpressed with CBFβ (11). CBFβ has been found to influence HIV-1 Vif's stability (9), Cul5 binding (10), and mediation of A3G degradation (7–11).

In the current study, we have further examined several internal regions of CBFβ that are crucial either for assisting Vif or regulating RUNX activity. By testing both N- and C-terminal truncation mutants of CBFβ, we have also identified a minimally functional fragment of CBFβ that can mediate the Vif-induced degradation of A3G. Overall, we have demonstrated that different domains of CBFβ are required for the protein's Vif- and RUNX-related functions, indicating that the CBFβ-Vif interaction and CBFβ-RUNX binding require different domains of CBFβ and suggesting new possibilities for anti-HIV-1 drug design.

CBFβ1–126 is fully functional in Vif-induced depletion of A3G.

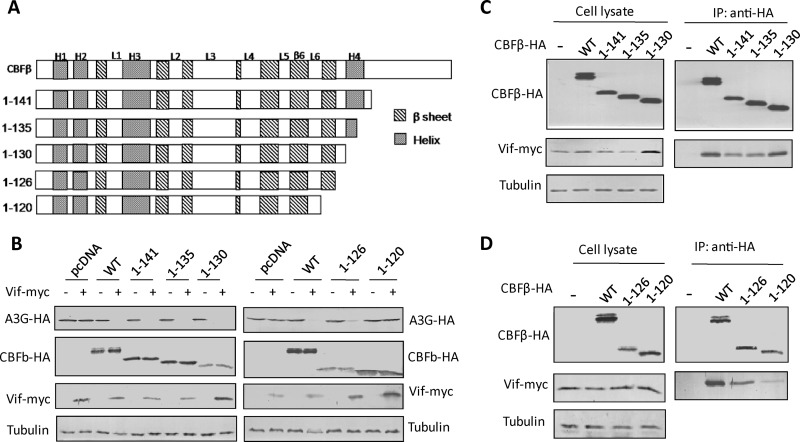

The interaction between C-terminal-truncated CBFβ and the Vif protein in vitro (11) triggered our interest in examining these CBFβ variants for their potency in contributing to Vif function. PCR was performed with pCBFβ-myc (10) as the template. The purified product was inserted into pcDNA3.1(-) (Invitrogen) to generate pCBFβ-HA. pCBFβ1-141-HA, pCBFβ1-135-HA, pCBFβ1-130-HA, pCBFβ1-126-HA, and pCBFβ1-120-HA were then constructed from pCBFβ-HA by site-directed mutagenesis and confirmed by DNA sequencing (Fig. 1A).

Fig 1.

CBFβ N-terminal residues1 to 126 are sufficient to support Vif in inducing A3G degradation. (A) Cartoon of CBFβ C-terminal truncation. (B) Effect of C-terminal CBFβ deletions on Vif-mediated A3G degradation. A3G-HA, HXB2-Vif, and CBFβ variants were cotransfected into CBFβ-knocked down HEK293T cells, and Western blotting was carried out to detect A3G, Vif, and CBFβ expression. Results are representative of three independent experiments. (C and D) Co-IP to detect interactions between HIV-Vif and the CBFβ variants in the absence of A3G. Results are representative of three independent experiments.

To determine the relative potency of CBFβ mutants with regard to their effects on Vif-mediated A3G degradation, we cotransfected HEK293T cells with the C-terminal-truncated CBFβ constructs and Vif- and A3G-expressing vectors; the expression of endogenous CBFβ had been depleted in these cells by the introduction of shRNA (CloneID numbers TRCN0000016644, TRCN0000016645; Open Biosystems). In brief, CBFβ knocked down HEK293T cells at 80% confluence were cotransfected with 300 ng of A3G-HA plasmid, 900 ng of Vif-myc plasmid (both gifts of K. Strebel), and 1 μg of one of the CBFβ-HA variant constructs. Cells were harvested at 48 h posttransfection. Western blotting was carried out with anti-hemagglutinin (anti-HA) antibody (catalog number 715500; Invitrogen) to detect A3G and CBFβ and with anti-Myc antibody (MMS-101P; Covance) to detect Vif.

The interactions between CBFβ variants and Vif were then characterized by coimmunoprecipitation (co-IP). Cells were harvested at 48 h posttransfection, washed with 1× phosphate-buffered saline, and suspended in lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5], 150 mM NaCl, and 0.5% to 1.5% NP-40, supplemented with Roche protease inhibitor cocktail). Samples were sonicated at 15% power for 60 s with a 3-s break every 3 s and then centrifuged to obtain a clear supernatant. Input samples were incubated with HA-labeled beads (Roche) for 3 h, then washed several times with wash buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5], 100 mM NaCl, 0.1 mM EDTA, and 0.05% Tween 20). The samples were then eluted with 100 mM glycine-HCl (pH 2.5).

We first discovered that CBFβ1–141 could still inactivate A3G in the presence of Vif (Fig. 1B); this inhibition was later determined to be due to a potent interaction between CBFβ1–141 and Vif (Fig. 1C) that resembled our previously reported finding for Escherichia coli (11). Further study revealed that deletion of amino acid residues 127 to 182 or fewer residues (CBFβ1–135, CBFβ1–130, and CBFβ1–126) had very little impact on CBFβ's ability to assist Vif, suggesting that the long C-terminal tail of CBFβ is not required for the Vif-induced degradation of A3G or even for binding to Vif (Fig. 1B to D). However, further deletion of six more residues at the C terminus (CBFβ1–120) almost completely abolished the ability of CBFβ to contribute to Vif-induced A3G degradation (Fig. 1B). Our IP results indicated that these six residues (121 to 126) are critical for the interaction of CBFβ with Vif (Fig. 1D). Therefore, binding to Vif is critical for CBFβ enhancement of Vif function. Vif expression appears quite variable, depending on the cotransfected CBFβ variant. However, there is no direct correlation between Vif function and the ability of CBFβ truncations to enhance Vif expression. For example, CBFβ1–120 showed increased Vif expression but did not support Vif-mediated A3G degradation (Fig. 1B).

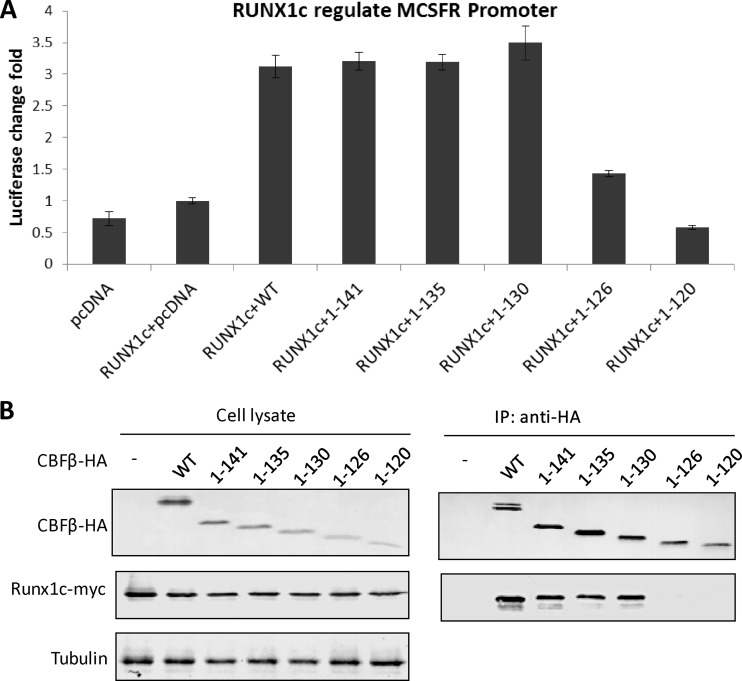

CBFβ1–130, but not CBFβ1–126, can fully support RUNX1-mediated gene transcription.

Inside eukaryotic cells, CBFβ has a natural binding factor named RUNX, and CBFβ-RUNX binding has been shown to be essential for regulation of host gene expression (36, 37). It would therefore be interesting to determine whether a CBFβ variant that is able to assist Vif could still regulate a RUNX1-mediated promoter. Therefore, we transfected CBFβ-knocked down HEK293T cells with 500 ng of a firefly luciferase MCSFR promoter construct (pMCSFR-luc) (38), 500 ng of the RUNX1c-myc plasmid (gift of A. Friedman), and 1 μg of each CBFβ-HA variant construct in triplicate. At 48 h posttransfection, the cells were lysed, and the luciferase activity was quantified with the Promega dual-luciferase reporter assay system according to the manufacturer's protocol.

Surprisingly, although CBFβ1–126 was fully functional in terms of the Vif-induced degradation of A3G, it lost the ability to regulate RUNX1 (a >2-fold decrease); in contrast, all other longer variants, including CBFβ1–130, maintained the ability to regulate RUNX1 (Fig. 2A). Further investigation suggested that although binding to RUNX was detected for all the other functional CBFβ variants (Fig. 2B), CBFβ1–126 and CBFβ1–120 were unable to bind RUNX1 efficiently (Fig. 2B). Therefore, we concluded that different lengths of CBFβ are required for its role in Vif function and for its role in RUNX function, with residues 127 to 130 being essential for RUNX1-mediated gene transcription.

Fig 2.

CBFβ1–130, but not CBFβ1–126 or CBFβ1–120, can interact with RUNX1c and regulate gene transcription mediated by RUNX1c. (A) Luciferase assays confirmed that CBFβ1–130 is functional in terms of RUNX1c regulation of the MCSFR promoter. It has been reported that endogenous RUNX1 expression is very low in HEK293 cells. For the MCSFR promoter assay, exogenous RUNX1 was introduced into HEK293 cells, as previously described (38). For all luciferase tests, the ratio of the luciferase count of the MCSFR promoter-Luc plus Runx1 and a control vector was used as the reference and was set to 1. Results are representative of four independent experiments. Each bar is the average of three replicates from the same experiment (error bars indicate standard deviations). (B) CBFβ1–130 can still interact with RUNX1c, while CBFβ1–126 and CBFβ1–120 do not have this capability. Results are representative of three independent experiments.

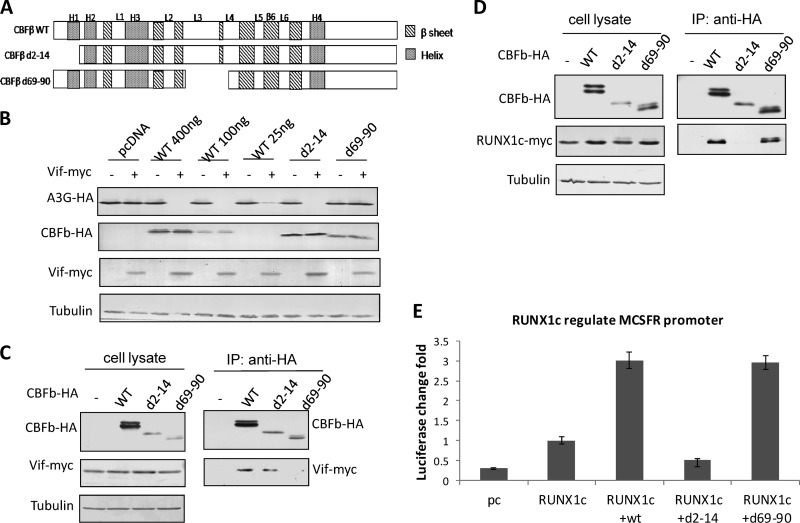

CBFβ acts through different domains in its interactions with Vif and RUNX1.

The differing potencies of CBFβ1–126 and CBFβ1–130 with regard to RUNX1 led us to hypothesize that CBFβ may function through different domains in assisting Vif and RUNX1. We therefore tested this hypothesis by using CBFβd2-14 and CBFβd69-90 (Fig. 3A), which were previously reported to have different abilities to bind Vif (10). Consistently, CBFβ variant d2-14, which could still bind Vif, was fully functional in assisting with the degradation of A3G (Fig. 3B and C), indicating that the first 14 residues of CBFβ are also dispensable for Vif assistance. In contrast, CBFβ variant d69-90 failed to bind Vif and assist in degrading A3G (Fig. 3B and C), confirming that the CBFβ-Vif interaction is essential for the downstream degradation of A3G. The RUNX1-mediated promoter test presented a different story, however, with d2-14, but not d69-90, failing to bind RUNX and support RUNX function (Fig. 3D and E). Therefore, CBFβ indeed interacts with RUNX and Vif through different binding regions.

Fig 3.

CBFβ acts through different domains to assist Vif and RUNX1. (A) Cartoon of CBFβ domain truncations. (B) Functional comparison of wild-type and mutant CBFβ, N-terminal CBFβ truncation d2-14, showed that the mutant could support Vif function in degrading A3G, while truncation d69-90 was defective for Vif-induced A3G degradation. Results are representative of five independent experiments. (C) Co-IP showed that CBFβd2-14 could bind Vif, but d69-90 could not. Results are representative of three independent experiments. (D) CBFβd69-90 could bind RUNX1c, but d2-14 could not. Results are representative of three independent experiments. (E) Luciferase assays confirmed that CBFβd69-90 was fully functional in terms of RUNX1c regulation of the MCSFR promoter, but d2-14 was not. Results are representative of three independent experiments. Each bar is the average of three replicates from the same experiment (error bars indicate standard deviations).

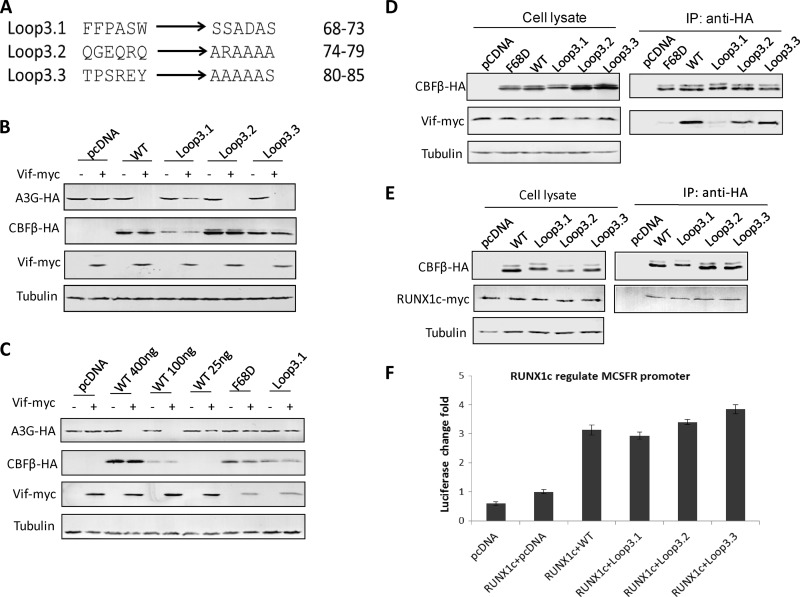

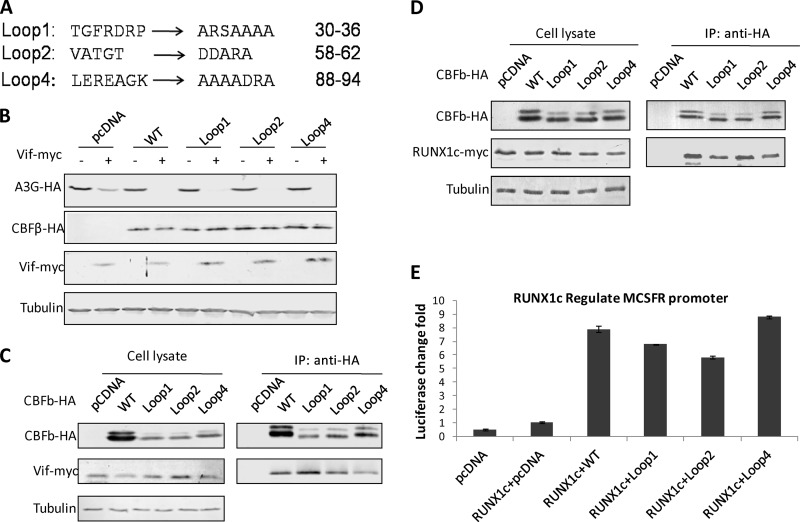

Loop3, but not other loops of CBFβ, is important for inactivation of A3G.

CBFβd69-90, whose deletion covers the majority of the longest loop (Loop3, residues 68 to 85) in the published CBFβ structure (PDB 1H9D) (39), is deficient for Vif binding (10), indicating the importance of this loop for Vif binding. We therefore introduced several mutations into Loop3: pCBFβLoop3.1-HA, pCBFβLoop3.2-HA, and pCBFβLoop3.3-HA were synthesized and sequenced by Shanghai Generay Biotech Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China) (Fig. 4A). Further tests indicated that only the first 6 amino acids of Loop3 were important for the degradation of A3G, since mutations in this area led to a partial rescue of A3G in the presence of Vif (Fig. 4B and D). We did notice that the expression of Loop3.1 in Fig. 4B was lower than that of wild-type CBFβ, so a dose-dependent experiment was conducted with wild-type CBFβ, and we again observed the inability of Loop3.1 in assisting Vif (Fig. 4C). Consisting of CBFβd69-90, this mutation did not alter CBFβ's capacity to assist RUNX1 (Fig. 4E and F). Similar tests were also performed with other CBFβ loops, including Loop1, Loop2, and Loop4, to identify other potential Vif binding domains (Fig. 5A). Loop5 was excluded because of its possible interaction with RUNX, according to the reported crystal structure (39). Analysis of Loop1, Loop2, and Loop4 mutants indicated that these areas were not important for either Vif-mediated degradation of A3G or for RUNX1-mediated regulation of gene expression (Fig. 5B to E). It is possible that these loop mutants may have an increased affinity for Vif (Fig. 5C).

Fig 4.

Mutations occurring on Loop3 of CBFβ have no impact on RUNX1-mediated transcription, while the first six residues of Loop3 are important for Vif-induced degradation of A3G. (A) Mutations designed for Loop3 of CBFβ. In general, Ala scanning mutagenesis was performed. However, to achieve the maximum effect, small amino acids, such as Gly and Ala, were changed to charged amino acids. Hydrophobic amino acids with aromatic long side chain, such as Phe and Try, were changed to hydrophilic Ser residues. A similar strategy was also applied to the other loop mutations. (B) The first 6 amino acids in Loop3 are important for Vif-induced A3G degradation. Results are representative of four independent experiments. (C) Functional comparison of wild-type CBFβ and mutant CBFβ (Loop3.1 and F68D). Both mutant CBFβ Loop3.1 and F68D lost the capability for assisting Vif in degrading A3G compared to wild-type CBFβ. Results are representative of three independent experiments. (D) Co-IP indicated that Loop3.1 malfunctions because of a compromised interaction with Vif. Results are representative of three independent experiments. (E) Co-IP confirmed that the mutations on Loop3 did not affect the CBFβ-RUNX1c interaction. Results are representative of three independent experiments. (F) Luciferase assays confirmed that all Loop3 mutants were fully functional with regard to Runx1c-mediated regulation of the MCSFR promoter. Results are representative of three independent experiments. Each bar is the average of three replicates from the same experiment (error bars indicate standard deviations).

Fig 5.

Mutations occurring in other loops of CBFβ have no impact on either RUNX1-mediated transcription or Vif-induced A3G degradation. (A) Mutations designed for Loop1, Loop2, and Loop4. (B) No crucial residue was detected in these loops in terms of Vif-induced A3G degradation. Results are representative of four independent experiments. (C) Co-IP confirmed that mutations in Loop1, Loop2, or Loop4 do not affect the CBFβ-Vif interaction. Results are representative of three independent experiments. (D) Co-IP confirmed that mutations in Loop1, Loop2, or Loop4 do not affect the CBFβ-RUNX1c interaction. Results are representative of three independent experiments. (E) Luciferase assays confirmed that all these mutants were fully functional in terms of RUNX1c-mediated regulation of the MCSFR promoter. Results are representative of three independent experiments. Each bar is the average of three replicates from the same experiment (error bars indicate standard deviations).

In this study, we have now for the first time screened both the N and C termini of CBFβ for a primary functional domain that is important for Vif function. Our results with C-terminal truncations of different lengths suggested that the entire C-terminal tail, together with the last helix (H4), is not required for assisting Vif; our examination of CBFβd2-14, on the other hand, revealed that residues 2 to 14 of CBFβ are also dispensable. Therefore, we conclude that CBFβ15–126 contains the minimum fragment required for CBFβ to maintain the ability to assist in the Vif-induced degradation of A3G.

CBFβ is essential for mouse embryo development. It was surprising that we connected functional CBFβ truncations, such as CBFβ1–126 and CBFβ1–130, to Vif and RUNX, respectively, since it has been reported that the CBFβ155 isoform, composed of CBFβ1–133 plus residues 161 to 182 cannot restore the development of murine embryos (4). Since we determined that the C-terminal tail of CBFβ131–182 is dispensable for both Vif-induced A3G degradation and RUNX1-mediated transcription of the MCSFR promoter, it is possible that the C-terminal tail of CBFβ has a novel function in embryo development. It is also possible that different domains on CBFβ are required for the regulation of different host genes.

We previously reported that Loop3 of CBFβ may be important for Vif binding (10). In the current study, we determined that the first six amino acids (68 to 73) in Loop3 of CBFβ are important for Vif binding and function. During the preparation of this paper, Hultquist et al. reported findings (8) that shared some similarities with ours. For example, they observed that CBFβF68D was defective for Vif binding and function. It is not clear whether only F68 in Loop3 is important for Vif binding and function. We observed that CBFβF68S could still support Vif function (data not shown). Further study will be required to determine the importance of amino acids 69 to 73 of CBFβ in Vif binding/function.

Various distinct regions of CBFβ were shown in this study to be important either for Vif's ability to degrade A3G or for RUNX-mediated regulation of host genes. However, no regions have been discovered yet that have an impact on both functions of CBFβ. Hultquist et al. recently screened a series of CBFβ mutants and also found no mutants that affected both the Vif-related and RUNX-related activities (8). In addition, according to the known structure of the binding region between CBFβ and RUNX, the region (Loop3) of CBFβ that has been found to be critical for Vif binding has no contact with RUNX1. Therefore, the one protein, CBFβ, must fulfill different requirements for HIV-1 Vif-mediated A3G degradation and RUNX1-mediated transcription. A more detailed understanding of the CBFβ-Vif binding interface should provide crucial information for designing anti-HIV-1 drugs that will not interrupt normal CBFβ-RUNX function in human cells.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank K. Strebel, A. Friedman, and S. L. Evans for critical reagents; S. L. Evans, J. Hou, and L. Li for technical assistance; R. Markham, J. Margolick, and J. Bream for thoughtful discussions; and D. McClellan for editorial assistance.

This work was supported in part by funding from the Chinese Ministry of Science and Technology (2012CB911100) and Chinese Ministry of Education (IRT1016), the Key Laboratory of Molecular Virology, Jilin Province (20102209), China, and a grant (2R56AI62644-6) from the NIAID.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 21 November 2012

REFERENCES

- 1. Adya N, Castilla LH, Liu PP. 2000. Function of CBFβ/Bro proteins. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 11:361–368 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. de Bruijn MF, Speck NA. 2004. Core-binding factors in hematopoiesis and immune function. Oncogene 23:4238–4248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Speck NA. 2001. Core binding factor and its role in normal hematopoietic development. Curr. Opin. Hematol. 8:192–196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Wang Q, Stacy T, Miller JD, Lewis AF, Gu TL, Huang X, Bushweller JH, Bories JC, Alt FW, Ryan G, Liu PP, Wynshaw-Boris A, Binder M, Marin-Padilla M, Sharpe AH, Speck NA. 1996. The CBFβ subunit is essential for CBFα2 (AML1) function in vivo. Cell 87:697–708 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Rhoades KL, Hetherington CJ, Rowley JD, Hiebert SW, Nucifora G, Tenen DG, Zhang DE. 1996. Synergistic up-regulation of the myeloid-specific promoter for the macrophage colony-stimulating factor receptor by AML1 and the t(8;21) fusion protein may contribute to leukemogenesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 93:11895–11900 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Miyazono K, Maeda S, Imamura T. 2004. Coordinate regulation of cell growth and differentiation by TGF-beta superfamily and Runx proteins. Oncogene 23:4232–4237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hultquist JF, Binka M, LaRue RS, Simon V, Harris RS. 2012. Vif proteins of human and simian immunodeficiency viruses require cellular CBFβ to degrade APOBEC3 restriction factors. J. Virol. 86:2874–2877 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hultquist JF, McDougle RM, Anderson BD, Harris R. 13 August 2012, posting date HIV type 1 Vif and the RUNX transcription factors interact with core binding factor β on genetically distinct surfaces. AIDS Res. Hum. Retroviruses 28:1543–1551 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Jager S, Kim DY, Hultquist JF, Shindo K, LaRue RS, Kwon E, Li M, Anderson BD, Yen L, Stanley D, Mahon C, Kane J, Franks-Skiba K, Cimermancic P, Burlingame A, Sali A, Craik CS, Harris RS, Gross JD, Krogan NJ. 2012. Vif hijacks CBF-beta to degrade APOBEC3G and promote HIV-1 infection. Nature 481:371–375 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Zhang W, Du J, Evans SL, Yu Y, Yu XF. 2012. T-cell differentiation factor CBF-beta regulates HIV-1 Vif-mediated evasion of host restriction. Nature 481:376–379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Zhou X, Evans SL, Han X, Liu Y, Yu XF. 2012. Characterization of the interaction of full-length HIV-1 Vif protein with its key regulator CBFβ and CRL5 E3 ubiquitin ligase components. PLoS One 7:e33495 doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0033495 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bieniasz PD. 2004. Intrinsic immunity: a front-line defense against viral attack. Nat. Immunol. 5:1109–1115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Chiu YL, Greene WC. 2008. The APOBEC3 cytidine deaminases: an innate defensive network opposing exogenous retroviruses and endogenous retroelements. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 26:317–353 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Cullen BR. 2006. Role and mechanism of action of the APOBEC3 family of antiretroviral resistance factors. J. Virol. 80:1067–1076 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Goff SP. 2004. Retrovirus restriction factors. Mol. Cell 16:849–859 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Harris RS, Liddament MT. 2004. Retroviral restriction by APOBEC proteins. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 4:868–877 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Jarmuz A, Chester A, Bayliss J, Gisbourne J, Dunham I, Scott J, Navaratnam N. 2002. An anthropoid-specific locus of orphan C to U RNA-editing enzymes on chromosome 22. Genomics 79:285–296 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Malim MH, Emerman M. 2008. HIV-1 accessory proteins: ensuring viral survival in a hostile environment. Cell Host Microbe 3:388–398 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Navarro F, Landau NR. 2004. Recent insights into HIV-1 Vif. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 16:477–482 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Niewiadomska AM, Yu XF. 2009. Host restriction of HIV-1 by APOBEC3 and viral evasion through Vif. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 339:1–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Rogozin IB, Basu MK, Jordan IK, Pavlov YI, Koonin EV. 2005. APOBEC4, a new member of the AID/APOBEC family of polynucleotide (deoxy)cytidine deaminases predicted by computational analysis. Cell Cycle 4:1281–1285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Rose KM, Marin M, Kozak SL, Kabat D. 2004. Transcriptional regulation of APOBEC3G, a cytidine deaminase that hypermutates human immunodeficiency virus. J. Biol. Chem. 279:41744–41749 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Rose KM, Marin M, Kozak SL, Kabat D. 2004. The viral infectivity factor (Vif) of HIV-1 unveiled. Trends Mol. Med. 10:291–297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Sheehy AM, Gaddis NC, Choi JD, Malim MH. 2002. Isolation of a human gene that inhibits HIV-1 infection and is suppressed by the viral Vif protein. Nature 418:646–650 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Turelli P, Trono D. 2005. Editing at the crossroad of innate and adaptive immunity. Science 307:1061–1065 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Yu X, Yu Y, Liu B, Luo K, Kong W, Mao P, Yu XF. 2003. Induction of APOBEC3G ubiquitination and degradation by an HIV-1 Vif-Cul5-SCF complex. Science 302:1056–1060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Conticello SG, Harris RS, Neuberger MS. 2003. The Vif protein of HIV triggers degradation of the human antiretroviral DNA deaminase APOBEC3G. Curr. Biol. 13:2009–2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Liu B, Yu X, Luo K, Yu Y, Yu XF. 2004. Influence of primate lentiviral Vif and proteasome inhibitors on human immunodeficiency virus type 1 virion packaging of APOBEC3G. J. Virol. 78:2072–2081 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Luo K, Xiao Z, Ehrlich E, Yu Y, Liu B, Zheng S, Yu XF. 2005. Primate lentiviral virion infectivity factors are substrate receptors that assemble with cullin 5-E3 ligase through a HCCH motif to suppress APOBEC3G. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 102:11444–11449 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Marin M, Rose KM, Kozak SL, Kabat D. 2003. HIV-1 Vif protein binds the editing enzyme APOBEC3G and induces its degradation. Nat. Med. 9:1398–1403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Mehle A, Goncalves J, Santa-Marta M, McPike M, Gabuzda D. 2004. Phosphorylation of a novel SOCS-box regulates assembly of the HIV-1 Vif-Cul5 complex that promotes APOBEC3G degradation. Genes Dev. 18:2861–2866 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Mehle A, Strack B, Ancuta P, Zhang C, McPike M, Gabuzda D. 2004. Vif overcomes the innate antiviral activity of APOBEC3G by promoting its degradation in the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 279:7792–7798 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Sheehy AM, Gaddis NC, Malim MH. 2003. The antiretroviral enzyme APOBEC3G is degraded by the proteasome in response to HIV-1 Vif. Nat. Med. 9:1404–1407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Stopak K, de Noronha C, Yonemoto W, Greene WC. 2003. HIV-1 Vif blocks the antiviral activity of APOBEC3G by impairing both its translation and intracellular stability. Mol. Cell 12:591–601 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Yu Y, Xiao Z, Ehrlich ES, Yu X, Yu XF. 2004. Selective assembly of HIV-1 Vif-Cul5-ElonginB-ElonginC E3 ubiquitin ligase complex through a novel SOCS box and upstream cysteines. Genes Dev. 18:2867–2872 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Durst KL, Hiebert SW. 2004. Role of RUNX family members in transcriptional repression and gene silencing. Oncogene 23:4220–4224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Ito Y. 2004. Oncogenic potential of the RUNX gene family: overview. Oncogene 23:4198–4208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Kamikubo Y, Zhao L, Wunderlich M, Corpora T, Hyde RK, Paul TA, Kundu M, Garrett L, Compton S, Huang G, Wolff L, Ito Y, Bushweller J, Mulloy JC, Liu PP. 2010. Accelerated leukemogenesis by truncated CBF beta-SMMHC defective in high-affinity binding with RUNX1. Cancer Cell 17:455–468 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Tahirov TH, Inoue-Bungo T, Morii H, Fujikawa A, Sasaki M, Kimura K, Shiina M, Sato K, Kumasaka T, Yamamoto M, Ishii S, Ogata K. 2001. Structural analyses of DNA recognition by the AML1/Runx-1 Runt domain and its allosteric control by CBFβ. Cell 104:755–767 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]