Abstract

Viral infections of the central nervous system (CNS) can trigger an antiviral immune response, which initiates an inflammatory cascade to control viral replication and dissemination. The extent of the proinflammatory response in the CNS and the timing of the release of proinflammatory cytokines can lead to neuronal excitability. Tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) and interleukin-6 (IL-6), two proinflammatory cytokines, have been linked to the development of acute seizures in Theiler's murine encephalomyelitis virus-induced encephalitis. It is unclear the extent to which the infiltrating macrophages versus resident CNS cells, such as microglia, contribute to acute seizures, as both cell types produce TNF-α and IL-6. In this study, we show that following infection a significantly higher number of microglia produced TNF-α than did infiltrating macrophages. In contrast, infiltrating macrophages produced significantly more IL-6. Mice treated with minocycline or wogonin, both of which limit infiltration of immune cells into the CNS and their activation, had significantly fewer macrophages infiltrating the brain, and significantly fewer mice had seizures. Therefore, our studies implicate infiltrating macrophages as an important source of IL-6 that contributes to the development of acute seizures.

INTRODUCTION

Although the etiology of seizures is largely unknown, infection of the central nervous system (CNS) is a significant risk factor for acquired epilepsy. There have been over 100 viruses implicated in the development of seizures in humans, including herpesviruses, Japanese encephalitis virus, Nipah virus, influenza viruses, and nonpoliovirus picornaviruses (reviewed in reference1). Therefore, due to the large number and types of viruses, identifying and deciphering the mechanism by which viral infection induces seizures have been challenging. For example, two members of the family Picornaviridae, Enterovirus (EV) and Parechovirus (PeV), have been shown to induce seizures in infected children; however, the available diagnostic tests for EVs do not detect PeVs (2, 3). A recent retrospective study, using pediatric cerebrospinal fluid samples previously screened for EV, demonstrated that the inclusion of a novel PeV-specific PCR assay led to a 31% increase in the detection of viruses causing virally induced CNS symptoms and neonatal sepsis (4). Therefore, the role of viral infection in the induction of seizures has not been fully recognized, possibly due to the sensitivity and specificity of currently available viral diagnostic tests.

While there are many important, established animal models for the study of seizures/epilepsy, such as status epilepticus and trauma- and stroke-induced seizure models, these models do not mirror virally induced seizures in humans (1). A significant difficulty with earlier viral models is that infected animals either died as a result of acute encephalitis and/or they did not have seizures following infection. Our laboratory has recently developed the first infection-driven animal model for epilepsy, called the Theiler's murine encephalomyelitis virus (TMEV)-induced seizure model (5, 6). Approximately 50% of TMEV-infected C57BL/6 mice had seizures between days 3 to 10 postinfection (p.i.) (5). C57BL/6 mice infected with TMEV were able to clear the virus-infected cells by about day 14 p.i. Furthermore, approximately 50% of the mice that had acute seizures went on to develop spontaneous seizures after an undefined latent period (approximately 2 months), suggesting that a certain percentage of mice, as is seen in humans, have an epilepsy-like phenotype following viral encephalitis (5, 6). Therefore, the TMEV-induced seizure model is a viable model system to investigate the effect of an antiviral immune response on the CNS that could potentially lead to seizures/epilepsy.

TMEV is a picornavirus that naturally infects mice (7, 8). TMEV infects a variety of cells both in the CNS and in the periphery, including macrophages, dendritic cells, microglia, and astrocytes (9–12). Infection of cells with TMEV triggers a proinflammatory response consisting of type I interferons, tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), interleukin-6 (IL)-6, and various chemokines (13–18). The extent of the proinflammatory response in the CNS and the timing of the release of proinflammatory cytokines such as IL-6 and TNF-α can lead to neuronal excitability prior to the induction of the adaptive immune response, thereby implicating a role for the innate immune system in the induction of seizures. Therefore, TMEV infection has been used by our group to address how the innate immune system may have a pivotal role in the development of seizures/epilepsy.

Our recent work demonstrated an important role for microglia and macrophages in acute seizures (15, 16, 19). PCR arrays and antibody depletion studies were used to determine that monocyte-derived cells were important in the development of acute seizures (16). In addition, previous work from our laboratory suggested that both resident cells and infiltrating cells synergistically drive acute seizures, possibly through the secretion of IL-6 (16). However, it remains unclear the extent to which the infiltrating macrophages versus resident CNS cells, such as microglia, contribute to acute seizures (reviewed in reference1). Our rationale for defining what immune cells are involved in the induction of seizures is based on the potential of developing therapeutics that could be directed at these various cell types, ultimately resulting in innovative approaches for the prevention and inhibition of seizures/epilepsy.

In our current study, we demonstrate that peripheral macrophages infiltrating the brains of TMEV-infected mice at the onset of seizures (day 3 p.i.) are important in the induction of seizures. In addition, we provide evidence that both microglia and macrophages synergistically contribute to the induction of seizures by differentially secreting TNF-α and IL-6. Importantly, administration of the anti-inflammatory compound wogonin was shown to inhibit the entry of peripheral macrophages into the CNS and was effective in the treatment of seizures in the TMEV-induced seizure model. These data provide proof-of-concept evidence for IL-6+ macrophages being involved in the development of seizures.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals.

All animal experiments were conducted in accordance with the guidelines prepared by the Committee on Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, Institute of Laboratory Animals Resources, National Research Council. C57BL/6 mice were obtained from the Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). Transgenic mice expressing green fluorescence protein (GFP) [C57BL/6CrSlc-Tg (ACTb-EGFP) OsbC14-Y01-FM131] were provided by Gerald Spangrude (University of Utah). GFP chimeric mice were generated as previously described (16). Briefly, donor bone marrow cells were obtained from euthanized mice that were at least 8 weeks old. The bone marrow cells were isolated from the tibias and femurs of the donor mice by injecting phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 5% Cosmic calf serum (CCS; HyClone, Logan, UT). Red blood cells were lysed with ACK buffer (0.15 M ammonium chloride, 10 mM potassium bicarbonate [pH 7.2 to 7.4]) for 5 min, and the remaining cells were washed in PBS and counted. For chimeric generation, 5 × 106 donor cells were intravenously (i.v.) injected into lethally irradiated (1,200 rads) recipient mice (16). Mice were monitored for the 6 weeks required for engraftment before infection with TMEV. The success of the engraftment was determined by assessing, via flow cytometry, the levels of GFP+ bone marrow cells obtained at the termination of the experiment.

TMEV infection.

Mice used were either 5- to 6-week-old C57BL/6 mice or 11- to 12-week-old GFP chimeric mice. Mice were anesthetized with isofluorane by inhalation and infected intracerebrally (i.c.) with 3 × 105 PFU of the Daniels (DA) strain of TMEV or mock infected with PBS at a final volume of 20 μl per mouse. The DA strain of TMEV was propagated as previously described (20).

Peripheral mononuclear cell phenotyping.

Peripheral blood was obtained from mice 5 days prior to TMEV infection and 48 h after TMEV infection. Blood was obtained by submandibular bleed using Goldenrod lancets (MEDIpoint, Inc., Mineola, NY) and collected in BD Vacutainer tubes (BD Bioscience, San Jose, CA). Whole blood was stained with the indicated antibodies for 30 min at room temperature and lysed for 20 min with whole blood lysis buffer (BD Bioscience). Cells were washed two times, fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, and analyzed by flow cytometry.

Brain mononuclear cell phenotyping.

On day 3 p.i., mice were euthanized and perfused with PBS. Subsequently, cells were mechanically isolated from the brains and suspended in RPMI 1640 medium (Mediatech, Herndon, VA) supplemented with 1% l-glutamine (Mediatech), 1% antibiotics (Mediatech), 50 μM 2-mercaptoethanol (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), and 10% CCS. Cells were further purified with Histopaque-1083 (Sigma). Cells were treated with Fc block (BD Bioscience), stained with the indicated anti-mouse antibodies for 30 min at 4°C (anti-CD45–v500, anti-CD11c–peridinin chlorophyll protein [PerCP]-Cy5.5, anti-CD3e–allophycocyanin [APC]-Cy7, and anti-CD86–phycoerythrin [PE]-Cy7 [all obtained from BD Bioscience]; anti-CD19–v450, anti-CD11b–APC, anti-major histocompatibility complex [MHC] class II antigen–PE, anti-NK1.1–PE [all obtained from eBioscience, San Diego, CA]), and analyzed by flow cytometry. Brain-derived cells were stained and analyzed individually for each mouse. Gating was determined based on fluorescence-minus-one (FMO) with isotype-matched immunoglobulin controls. More specifically, FMO controls contained each antibody conjugate used in the experiment except one, with the addition of the appropriate isotype control for the excluded fluorochrome. This was performed for each fluorochrome, using TMEV-infected brain samples. Live cells were determined by forward and side scatter fluorescence on a BD FACSCanto II apparatus (BD Bioscience). Cell sorting was performed at the University of Utah core facility on a FACSAria-II SORP (BD Bioscience). Approximately 5 × 104 sorted R2 cells were spun down onto slides using a Cytospin 2 (Shandon, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA), according to the manufacturer's instructions. The slides were then air dried at room temperature for 5 min, incubated with acetone for 5 min, air dried, and stained with hematoxylin (Harris) and eosin. Cell morphology of cells was determined by light microscopy. Flow cytometry data analysis was performed using FlowJo software (Tree Star, Inc., Ashland, OR).

Direct ICS.

Direct intracellular cytokine staining (ICS) was performed as previously described (21). Briefly, mice were injected i.v. with 250 μg brefeldin A (Sigma) per mouse 6 h prior to harvesting the brains. GFP chimeric mice were perfused with PBS, and brains were rapidly processed on ice. Extracellular surface staining for anti-CD11b–APC, and 7-amino-actinomycin D (7-AAD; BD Bioscience) was used for dead cell exclusion. Cells were then fixed and permeabilized with Cytofix/Cytoperm buffer (BD Bioscience), washed in Perm/Wash buffer (BD Bioscience), and stained with 0.5 μg/ml anti-IL-6–PE and anti-TNF-α–v450 (eBioscience) for 45 min at 4°C. Cells were washed with PBS containing 5% CCS prior to flow cytometry analysis.

Immunohistochemistry.

Mice were euthanized between days 5 and 14 p.i. Animals were perfused with PBS, followed by 4% paraformaldehyde, and brains were harvested, divided into five coronal slabs, and embedded in paraffin. Multiple 4-μm-thick tissue sections were cut and mounted onto slides. Viral antigen-positive cells were detected on paraffin sections using TMEV hyperimmune rabbit serum, as previously described (20, 22). GFP+ cells were detected with rabbit anti-GFP (Abcam, Cambridge, MA). Secondary fluorescent antibody was donkey anti-rabbit IgG–fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC; Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, West Grove, PA). Fluorescence was detected on a Nikon Eclipse E800 microscope, and analysis was performed using Image-Pro Plus imaging software (Media Cybernetics, Inc., Bethesda, MD).

For IL-6 staining, sections were incubated with 3% normal donkey serum (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories) for 30 min at room temperature, followed by incubation with rat (monoclonal) anti-mouse IL-6 unconjugated primary antibody (1:2,000 dilution in PBS; Invitrogen, San Diego, CA) overnight at 4°C. The next day, excess primary antibody was washed off with PBS, and the sections were sequentially incubated for 30 min at room temperature first with 1% hydrogen peroxide to block and then with donkey anti-rat IgG–biotin-SP–conjugated secondary antibody (1:2,500 dilution in PBS; Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories). The sections were visualized using the Vectastain ABC kit according to the manufacturer's recommendations (Vector Laboratories Inc., Burlingame, CA) in conjunction with 3,3′-diaminobenzidine tetrahydrochloride (Sigma) and 0.01% hydrogen peroxide (Sigma) treatment in PBS, followed by counterstaining with hematoxylin.

TNF-α staining was performed similarly to the IL-6 staining with slight modification. Briefly, an antigen retrieval step was performed by incubating slides in acid citrate buffer at 96°C for 30 min. Additionally, the primary antibody was anti-TNF-α (1:200 dilution in PBS; Abcam), and the secondary antibody was donkey anti-rabbit IgG–biotin (1:1,500 dilution in PBS; Jackson ImmunoResearch).

Enumeration of IL-6- and TNF-α-stained cells was performed in a blinded fashion with a light microscope, using one slide per brain and evaluating the section containing the hippocampal/dentate gyral region of the brain. Cytokine staining was enumerated in the following brain regions: dentate gyrus (DG), CA1, and CA2-CA3, all regions of the hippocampus, and the parietal cortex (PC). Using Image-Pro Plus imaging software, these regions were outlined on images (×10 magnification) of the section, and both IL-6- and TNF-α-stained cells were counted. A two-tailed t test was used to compare groups, and a P value of <0.05 was considered significant.

Wogonin and minocycline treatment.

Wogonin (5,7-dihydroxy-8-methoxy-2-phenyl-4H-chromen-4-one; Sigma) was administered at 3 mg/kg of body weight once a day. Five- to 6-week-old C57BL/6 mice were injected intraperitoneally (i.p.) 24 h prior to TMEV infection i.c. (3 × 105 PFU) and daily thereafter. Mice treated with vehicle (100% dimethyl sulfoxide [DMSO; Sigma]) were infected and injected in parallel with the wogonin-treated mice. Mice were monitored daily for seizures through day 21 p.i. Minocycline (Sigma) was administered i.p. two times a day at 50 mg/kg starting 24 h prior to TMEV infection (3 × 105 PFU) and continuing daily thereafter, as previously described (16).

Seizure scoring.

The monitoring of seizure activity was performed as previously described (16). Briefly, mice were observed for 2 h each day. Seizure activity was graded using the Racine scale: stage 1, mouth and facial movements; stage 2, head nodding; stage 3, forelimb clonus; stage 4, rearing; stage 5, rearing and falling (23, 24).

RESULTS

Immune cells in peripheral blood of TMEV-infected mice.

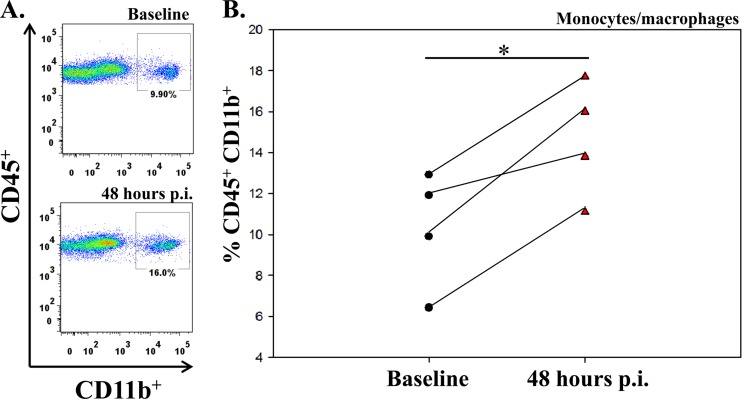

To determine the numbers of specific mononuclear cells in the peripheral blood of individual TMEV-infected mice compared to uninfected mice, blood was collected 5 days prior to and 48 h after infection. The numbers of mononuclear cells expressing markers for monocytes/macrophages (CD45+ CD11b+), dendritic cells (CD45+ CD11c+), T cells (CD45+ CD3+), and B cells (CD45+ CD19+) were determined by flow cytometry. The numbers of each cell type, except dendritic cells, was significantly higher in the peripheral blood following infection (48 h p.i.) compared to baseline (5 days prior to infection) (Table 1). Analysis of CD45+ CD11b+ monocytes/macrophages in the peripheral blood of individual TMEV-infected mice (Fig. 1) clearly demonstrated a significant increase in peripheral monocytes/macrophages for each mouse following infection (P < 0.05) (Fig. 1B).

Table 1.

TMEV infection increases the numbers of immune cells in the periphery

| Cell type | Phenotypic markers | Freq. of cells by type (mean ± SEM) ata: |

P valueb | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 48 h p.i. | |||

| Monocyte/ macrophage | CD45+ CD11b+ | 10.3 ± 1.4 | 14.7 ± 1.4 | 0.02 |

| Dendritic cell | CD45+ CD11c+ | 2.6 ± 0.4 | 3.0 ± 0.8 | NS |

| T cell | CD45+ CD3+ | 23.1 ± 2.2 | 33.4 ± 1.93 | 0.001 |

| B cell | CD45+ CD19+ | 36.5 ± 0.9 | 49.9 ± 0.9 | 0.002 |

Frequency (Freq. [%]) of cells of the indicated lymphocyte subsets in the periphery of mice 5 days prior to infection compared to blood obtained 48 h p.i. with TMEV. Data are means ± standards errors of the means for 4 mice per group.

Student's paired t test was used to determine P values. NS, not significant.

Fig 1.

Flow cytometry analysis of CD45+ CD11b+ monocytes/macrophages in the periphery of TMEV-infected mice. (A) Peripheral blood was collected from a single representative mouse by cheek bleed prior to infection (upper panel) and 48 h after TMEV infection (lower panel). (B) Graph of the flow cytometric data of each of 4 mice before infection (baseline; circles) and 48 h p.i. (red triangles). *, P < 0.05, Student's paired t test.

Phenotypic analysis of immune cells infiltrating the brains of TMEV-infected mice.

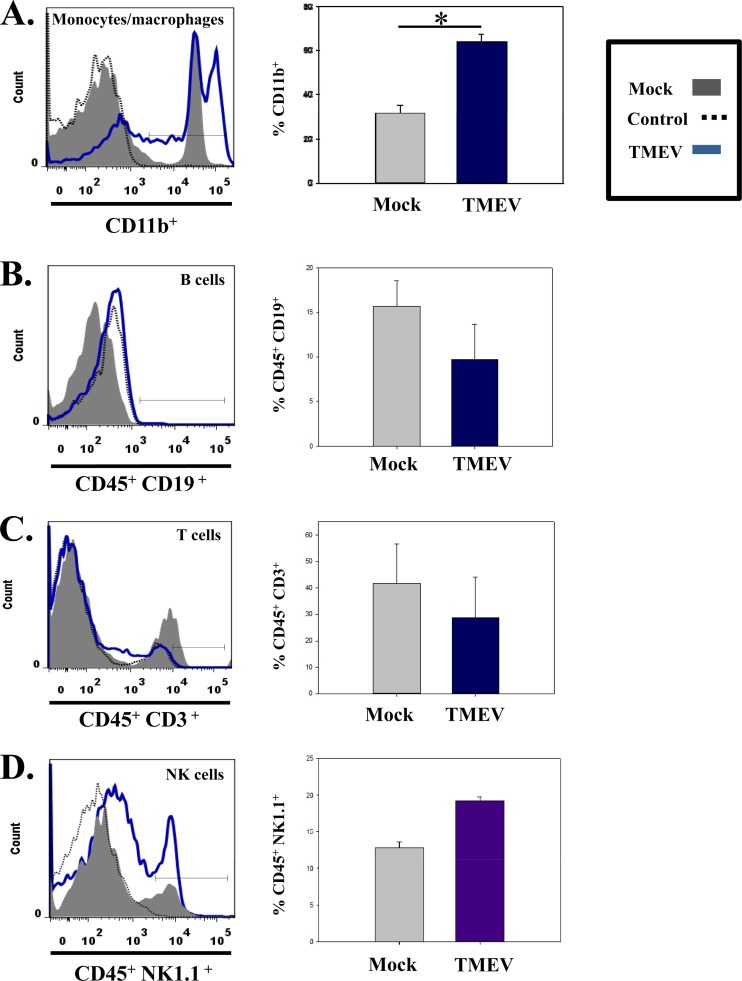

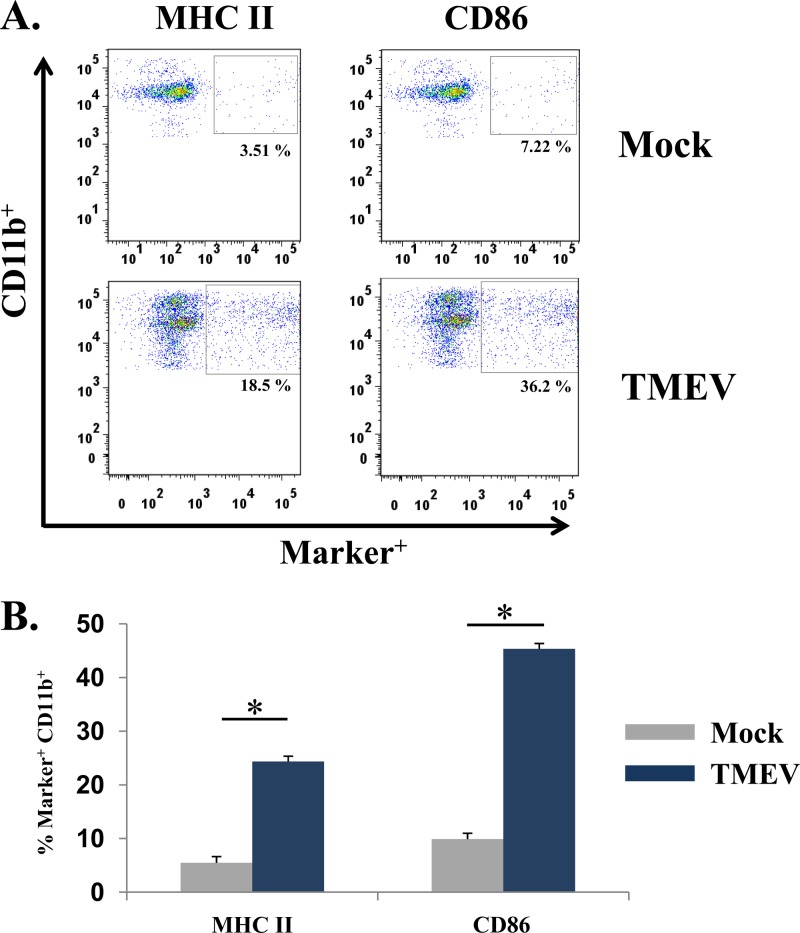

Previous work from our laboratory suggested that monocytes/macrophages were important in the induction of acute seizures (16). To determine if the increase in the number of peripheral blood mononuclear cells reflected what was occurring in the brain, we obtained brains from either mock- or TMEV-infected mice 3 days p.i. (a time point just prior to the onset of seizures). Quantification of cells isolated from the brains of infected mice in comparison to cells isolated from the brains of mock-infected mice showed a marked increase in the numbers of cells expressing CD11b (infiltrating macrophages and microglia) (P < 0.05) (Fig. 2A). CD45 was deliberately not used in the initial CD11b analysis as a means of including the resident monocyte-derived CNS cells (microglia) in addition to infiltrating macrophages in the analysis, thereby taking a more comprehensive approach to determine if there was an increase in CD11b expression. In contrast to the CD11b population, at 72 h p.i. few if any B cells (CD45+ CD19+) (Fig. 2B), T cells (CD45+ CD3+) (Fig. 2C), or natural killer cells (CD45+ NK1.1+) (Fig. 2D) were detected. In addition, phenotypic analysis of markers of activation of CD11b+ monocyte-derived cells showed a significant increase in MHC class II and CD86 expression on the CD11b+ cell populations isolated from the brains of TMEV-infected mice compared to mock-infected mice (P < 0.05) (Fig. 3). These results suggest that peripheral macrophages infiltrating the brain are involved in the development of acute seizures and, importantly, that the peripheral blood does not mirror what is occurring in the CNS.

Fig 2.

Numbers of specific cell types in the brains of TMEV-infected mice. Representative flow cytometry histograms (left panels) of cells isolated from the brains of either mock-infected (gray) or TMEV-infected (blue) mice. The cell types shown are monocytes/macrophages (CD11b+) (A), B cells (CD45+ CD19+) (B), T cells (CD45+ CD3+) (C), and natural killer cells (CD45+ NK1.1+) (D). Control responses (black dotted lines) were determined by the FMO method as described in Materials and Methods. Quantification of flow cytometry data (right panels) from three different experiments are presented as the mean + standard error of the mean with a total of 4 mice per group. Mock-infected mice were injected in parallel with TMEV-infected mice for each experiment. *, P < 0.05, Student's paired t test.

Fig 3.

Detection of markers of activation of CD11b+ monocyte-derived cells in the brains of TMEV-infected mice. (A) Representative flow cytometry plots of CD11b+ cells from the brains of either mock-infected (top panels) or TMEV-infected (lower panels) mice. Activation markers examined included MHC II and CD86. Gates (small boxes with percent of total cells found within gate) were set according to FMO, as described in Materials and Methods. (B) Quantification of flow cytometry data from three separate experiments, presented as the means + standard errors of the means of 4 mice per group. *, P < 0.05, Student's paired t test.

Resident microglia versus infiltrating macrophages.

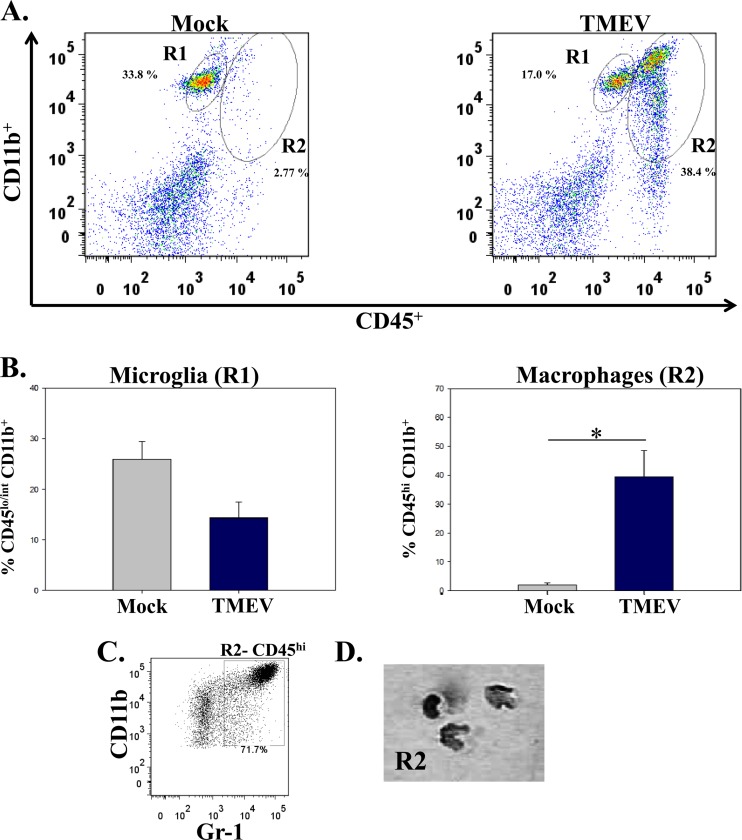

Both microglia and macrophages are derived from myeloid progenitor cells and, therefore, express similar cell surface markers (25). To determine whether resident microglia, instead of infiltrating macrophages, could be the CD11b+ cells found in the brains of TMEV-infected mice, phenotypic markers were used to differentiate microglia from macrophages; microglia have low to intermediate expression of CD45 and high CD11b expression, whereas macrophages express high levels of both CD45 and CD11b on the cell surface (26, 27). Cells from TMEV-infected mouse brains had macrophages (CD45hi CD11b+) (Fig. 4A, R2) infiltrating the brain compared to mock-infected mouse brain cells. The number of macrophages (CD45hi CD11b+) (Fig. 4B, R2) was significantly higher (P < 0.05) in TMEV-infected mice (39.3 ± 9.1 [mean ± standard error of the mean]) than in mock-infected mice (2.0 ± 0.8). The number of microglia (CD45lo/int CD11b+) (Fig. 4B, R1) was lower in the TMEV-infected mice (14.3 ± 3.2) than in mock-infected mice (25.9 ± 3.5), but this difference was not statistically significant. To verify that CD45hi CD11b+ cells were monocyte-derived cells and not neutrophils, the CD45hi CD11b+ (R2) cells expressing GR-1 protein were sorted, spun down onto a slide, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (Fig. 4C and D). The R2-sorted population was predominately monocytes and eosinophils, not cells with segmented nuclei (representative of neutrophils) (Fig. 4D).

Fig 4.

Differentiation between microglia and macrophages in the brains of TMEV-infected mice. (A) Representative flow cytometry plots of microglia (CD45lo/int CD11b+; R1) and macrophages (CD45hi CD11b+; R2) isolated from the brain of either a mock-infected mouse (left panel) or a TMEV-infected mouse (right panel). Gates were set according to FMO, as described in Materials and Methods. (B) Quantification of flow cytometry data from three separate experiments, presented as the means + standard errors of the means for 4 mice per group. *, P < 0.05, Student's paired t test. (C) Inflammatory monocytes (CD45hi CD11b+ Gr-1+) were analyzed by fluorescence-activated cell sorting. (D) Photomicrograph of cells stained with hematoxylin and eosin after they were cytospun.

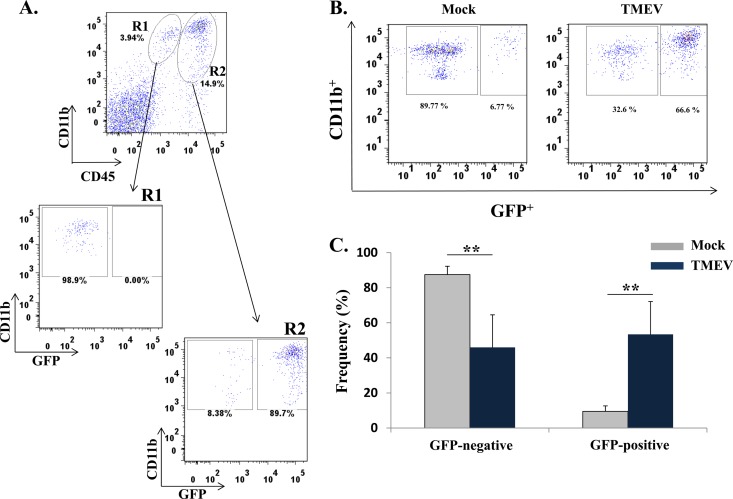

GFP chimeric mice were used to confirm that macrophages were infiltrating the brains of TMEV-infected mice and to exclude the possibility that microglia, expressing high levels of CD45 upon activation following infection, could account for the higher number of CD45hi CD11b+ cells present in the brains of TMEV-infected mice (Fig. 4, R2). GFP chimeric mice were generated by adoptive transfer of GFP+ bone marrow cells into C57BL/6 lethally irradiated mice (26, 28–31). Although the chimeric mice were older than the wild-type mice, previous work from our laboratory had demonstrated that age does not have an effect on the number of mice having seizures after TMEV infection (16). GFP chimeric mice were infected with TMEV, and phenotypic analysis was used to quantify the numbers of CD11c− CD11b+ GFP+/− cells (Fig. 5). Flow cytometric differentiation of microglia from macrophages confirmed that the R1 resident microglia population (CD45lo/int CD11b+) was the CD11c− CD11b+ GFP− cells, and the R2 infiltrating macrophage population (CD45hi CD11b+) was the CD11c− CD11b+ GFP+ cells (Fig. 5A). The brains from TMEV-infected mice had a significantly higher number of GFP+ cells, i.e., macrophages (53.42 ± 18.7) than brains from mock-infected chimeric mice (9.5 ± 3.1; P < 0.005) (Fig. 5B and C). The number of GFP− cells (microglia) quantified from the brains of TMEV-infected mice (46 ± 18.6) was significantly lower than in mock-infected mice (87.5 ± 4.8; P < 0.005) (Fig. 5C). Taken together, these results demonstrate that macrophages are the dominant cell type infiltrating the brain during acute seizures.

Fig 5.

Bone marrow-derived GFP+ cells (macrophages) infiltrate the brains of TMEV-infected mice. Brains were harvested 72 h p.i. The generation of GFP chimeric mice is described in Materials and Methods. (A) Representative flow cytometry plots of cells obtained from the brain of a TMEV-infected chimeric mouse in which the microglial (R1) and macrophage (R2) cell populations were assayed for GFP expression. (B) Representative flow cytometry plots of cells, obtained from the brains of either a mock-infected chimeric mouse (left panel) or a TMEV-infected chimeric mouse (right panel), that were assayed for the presence of the following cell surface markers: CD11c− CD11b+ GFP+/−. (C) Quantification of flow cytometry data from three separate experiments, presented as the means + standard errors of the means of 5 mice per group. **, P < 0.005, Student's paired t test.

Link between the number of mice having seizures and macrophages infiltrating the brain.

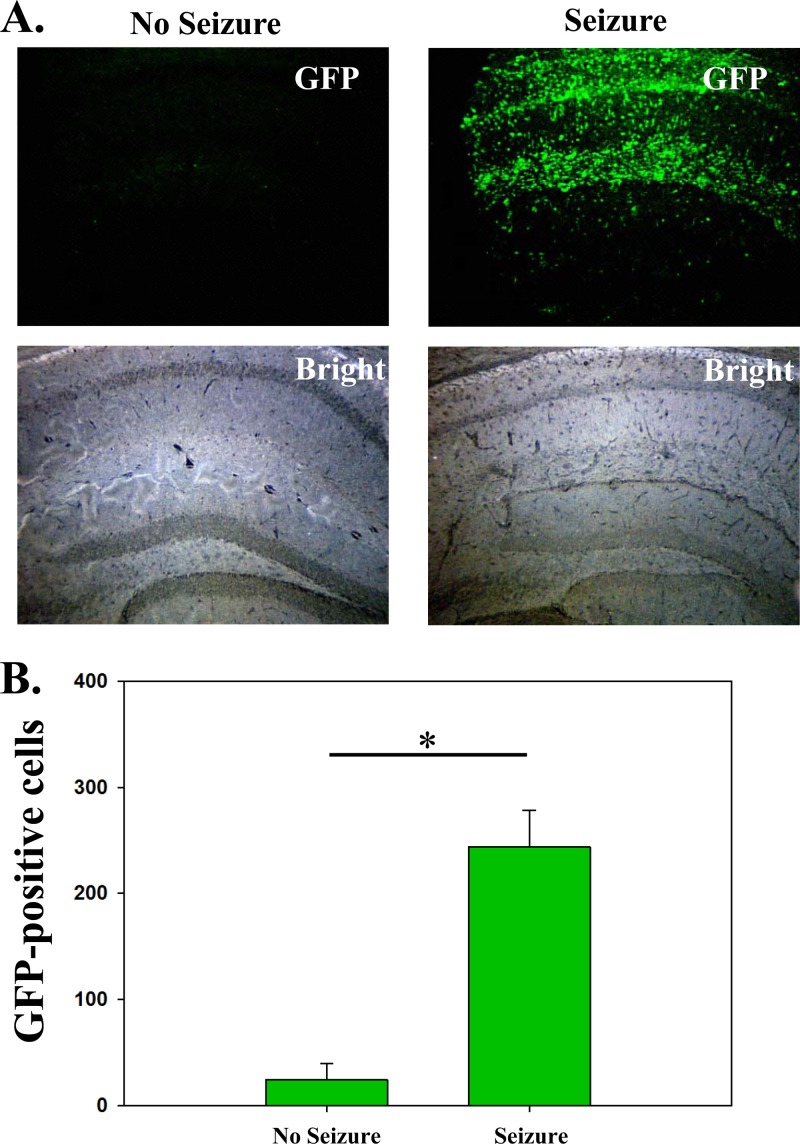

To establish a link between macrophages infiltrating the brain and mice having seizures, GFP chimeric mice were infected with TMEV and monitored daily for seizures. Mice were sacrificed between days 5 and 14 p.i., and brain sections were stained for GFP (infiltrating cells) (Fig. 6A). The GFP+ macrophages were quantified in the right hemisphere of the brains (site of injection) in a blinded fashion using Image-Pro Plus (Fig. 6B). Tissue sections from both mice having seizures and mice not having seizures were equally split between day 5 and day 14 for this analysis. There was a significant difference in the number of GFP+ macrophages in the brains of mice that had seizures (n = 6) versus mice that did not have seizures (n = 4; P < 0.05) (Fig. 6B). In support of previous work (32), the number of viral antigen-positive cells found to be present in the brains of these mice was markedly increased in mice with seizures (1,541 ± 654) than in mice without seizures (144 ± 87). These results show a link between macrophages infiltrating the brain and animals experiencing a seizure.

Fig 6.

Mice that have seizures have a significantly higher number of GFP+ infiltrating macrophages in the brain. Mice were observed for seizures daily as described in Materials and Methods. (A) Representative immunofluorescence of brain sections from mice that either had seizures (right panels) or did not have seizures (left panels). GFP+ cells (infiltrating macrophages) are shown in green. (B) Quantification of GFP+ cells. Whole-tissue slides were quantified for the right hemisphere (site of injection). *, P < 0.05, t test.

Microglial cell versus macrophage cytokine production.

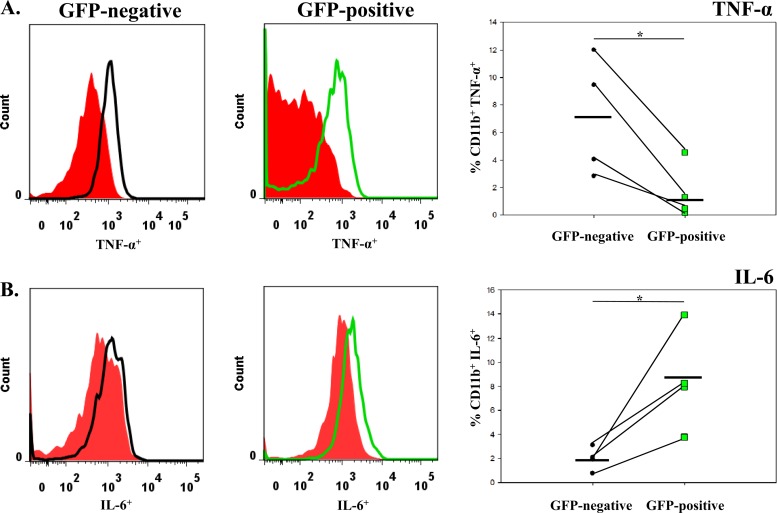

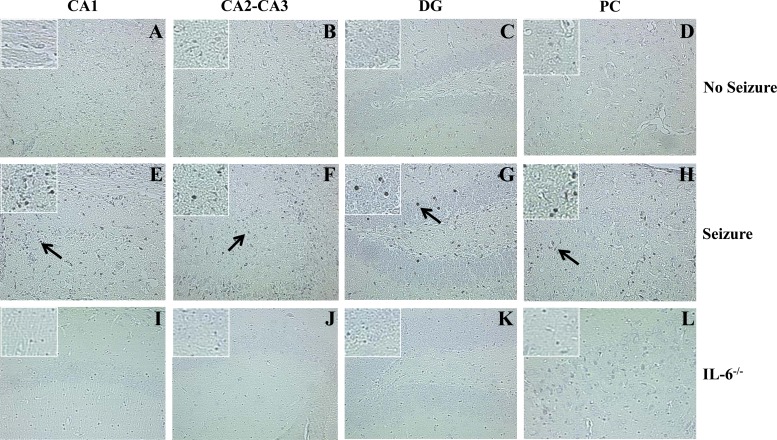

Both TNF-α and IL-6 cause the amplification of proinflammatory signals within the CNS, which can lead to neuronal excitability and its related neuropathology (16, 33–35). To determine if microglia and/or macrophages produce these cytokines following infection, cells were isolated from the brains of mock- and TMEV-infected GFP chimeric mice on day 3 p.i., and ex vivo ICS staining was performed for TNF-α and IL-6 (Fig. 7). None of the mice at day 3 p.i. was observed to have seizures, thereby not allowing a comparison between mice that had seizures and mice that did not have seizures. However, we could compare the cytokine levels between resident microglia and infiltrating macrophages. Significantly higher numbers of microglia (GFP−) were positive for TNF-α versus macrophages (GFP+; P < 0.05) (Fig. 7A). Conversely, macrophages (GFP+) represented significantly higher numbers of cells positive for IL-6 in comparison to microglia (GFP−; P < 0.05) (Fig. 7B). Furthermore, R1 and R2 cells from TMEV-infected wild-type mice were stained for IL-6, and the R2 infiltrating macrophages had a markedly higher number of IL-6+ cells than the R1 resident microglia cells (data not shown), thereby supporting the GFP chimeric cytokine results (Fig. 7). To confirm that TMEV-infected mice experiencing seizures had more IL-6+ and TNF-α+ cells in the brains than did controls and mice not experiencing seizures, immunohistochemical staining was performed (Tables 2 and 3; Fig. 8 and 9). There was a significant increase (P < 0.05) in the number of IL-6+ cells in the CA2-CA3 region of the hippocampus and PC region in mice that had seizures (Table 2; Fig. 8). Conversely, the DG and CA1 regions of the hippocampus had a significantly higher (P < 0.05) number of TNF-α+ cells (Table 3; Fig. 9). Taken together, microglia make up the majority of the TNF-α-producing cells, and infiltrating macrophages make up the majority of the IL-6-producing cells, which suggests that microglia and macrophages synergistically produce proinflammatory cytokines that potentially lead to the induction of acute seizures.

Fig 7.

TNF-α and IL-6 cytokine levels in GFP chimeric mice. TNF-α and IL-6 cytokine levels were assessed in GFP− and GFP+ cells isolated from TMEV-infected mouse brains. (A) TNF-α levels; (B) IL-6 levels. The red histograms are the FMO controls. The black line is representative of CD11c− CD11b+ GFP− cells. The green line is representative of CD11c− CD11b+ GFP+ cells. Each symbol in the far right graphs is representative of one mouse. The mean value is shown by the black line. *, P < 0.05, Student's paired t test.

Table 2.

TMEV infection leads to an increase in IL-6+ cells in mice that had seizures

| Mice (n) | No. of IL-6+ cells in compartment (mean ± SEM)a |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DG | CA1 | CA2-CA3 | PC | |

| Control (4) | 2.25 ± 0.75 | 2.75 ± 0.95 | 1 ± 0 | 2.25 ± 0.48 |

| Seizure (3) | 36 ± 24.34 | 42.25 ± 21.83 | 42.75 ± 20.78 | 43.38 ± 19.79 |

| No seizure (4) | 2 ± 1.08 | 8.25 ± 1.31 | 3.75 ± 1.49 | 7 ± 1.68 |

| P valueb | NS | NS | <0.05 | <0.05 |

Data are means ± standard errors of the means for the indicated number of mice per group. DG, dentate gyrus; PC, parietal cortex.

A t test was used to determine P values. Values were considered significant if P was <0.05 for both the control (IL-6 knockout mouse tissue sections) and no-seizure mice. NS, not significant.

Table 3.

TMEV infection leads to an increase in TNF-α+ cells in mice that had seizures

| Mice (n) | No. of TNF-α+ cells in compartment (mean ± SEM)a |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DG | CA1 | CA2-CA3 | PC | |

| Control (4) | 2.50 ± 1.55 | 6.75 ± 3.61 | 2.75 ± 0.85 | 1.75 ± 0.48 |

| Seizure (6) | 54.33 ± 14.73 | 85.67 ± 24.7 | 113.33 ± 50.05 | 84.00 ± 24.11 |

| No Seizure (4) | 6 ± 1.58 | 18.75 ± 5.02 | 8.5 ± 1.66 | 53 ± 50.34 |

| P valueb | <0.05 | <0.05 | NS | NS |

Data are means ± the standard errors of the means for the indicated number of mice per group. DG, dentate gyrus; PC, parietal cortex.

A t test was used to determine P values. Values were considered significant if P was <0.05 for both the control (no primary antibody) and no-seizure mice. NS, not significant.

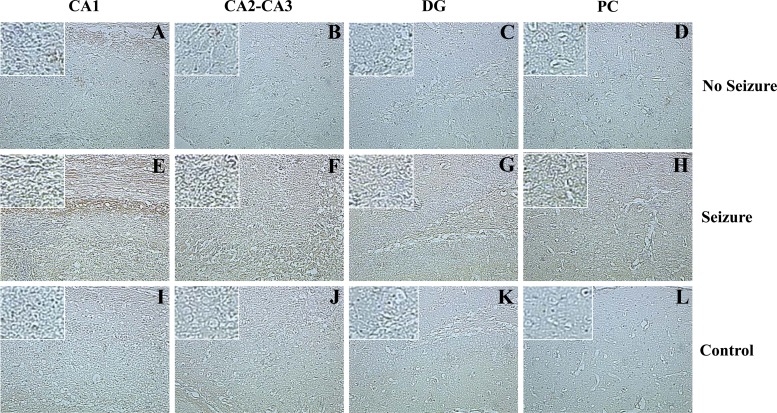

Fig 8.

IL-6+ cells in GFP chimeric mice, shown in representative hippocampal tissue sections immunohistochemically stained for IL-6. All representative brain tissue sections were obtained from TMEV-infected mice at day 7 p.i. (A to D) Sections from a mouse that did not experience seizures. (E to H) Sections from a mouse that experienced seizures. (I to L) Sections from a C57BL/6 IL-6−/− mouse. Arrows point to IL-6+ cells. Magnification, ×20; for insets, magnification is ×40. Control (IL-6−/−) TMEV-infected mice were stained in conjunction with the experimental tissue sections. CA, cornu ammonis; DG, dentate gyrus; PC, parietal cortex.

Fig 9.

TNF-α+ cells in GFP chimeric mice, shown in representative hippocampal tissue sections immunohistochemically stained for TNF-α. All representative brain tissue sections were obtained from TMEV-infected mice at day 7 p.i. (A to D) Sections from a mouse that did not experience seizures. (E to H) Sections from a mouse that experienced seizures. (I to L) Sections from a mouse that experienced seizures with no primary antibody (Ab). Brown indicates TNF-α staining. Magnification, ×20; for insets, magnification is ×40. Control (no primary Ab) TMEV-infected mice were stained in conjunction with the experimental tissue sections. CA, cornu ammonis; DG, dentate gyrus; PC, parietal cortex.

Inhibition of macrophage infiltration.

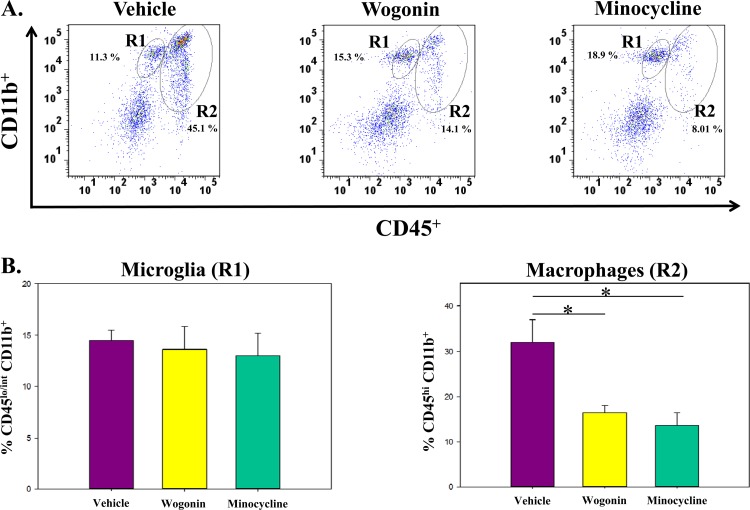

The natural root extract wogonin and the antibiotic minocycline were used to inhibit macrophage activity. Wogonin has antioxidant properties and can induce apoptosis of cells that have been previously sensitized by TNF-α (36, 37). Minocycline has anti-inflammatory properties that lead to lower CNS excitability (38). Flow cytometry was performed on cells isolated on day 3 p.i. from the brains of TMEV-infected C57BL/6 mice, which were treated with vehicle (DMSO), wogonin, or minocycline (Fig. 10). The number of microglial cells (R1) was not statistically different between the three treatment groups, but the number of infiltrating macrophages (R2) was significantly lower in the wogonin-treated (16.4%) and minocycline-treated (13.6%) groups versus the vehicle-treated group (32.1%; P < 0.05) (Fig. 10B). Both wogonin and minocycline inhibited the infiltration of macrophages by approximately 2-fold.

Fig 10.

TMEV-infected C57BL/6 mice treated with minocycline and wogonin have a significantly lower number of infiltrating macrophages in the brain than do vehicle-treated mice. (A) Representative flow cytometry plots of cells obtained on day 3 p.i. from the brains of TMEV-infected mice treated with vehicle (DMSO), wogonin, or minocycline. Microglial cells are CD45lo/int CD11b+ (R1). Macrophages are CD45hi CD11b+ (R2). (B) No significant differences in the numbers of microglia (R1) were detected. Minocycline- and wogonin-treated mice had significantly fewer macrophages (R2) that infiltrated into the brain than did vehicle-treated mice. Data are means + standard errors of the means for 5 mice per group. *, P < 0.05, Student's paired t test.

Fewer mice experience seizures when treated with wogonin.

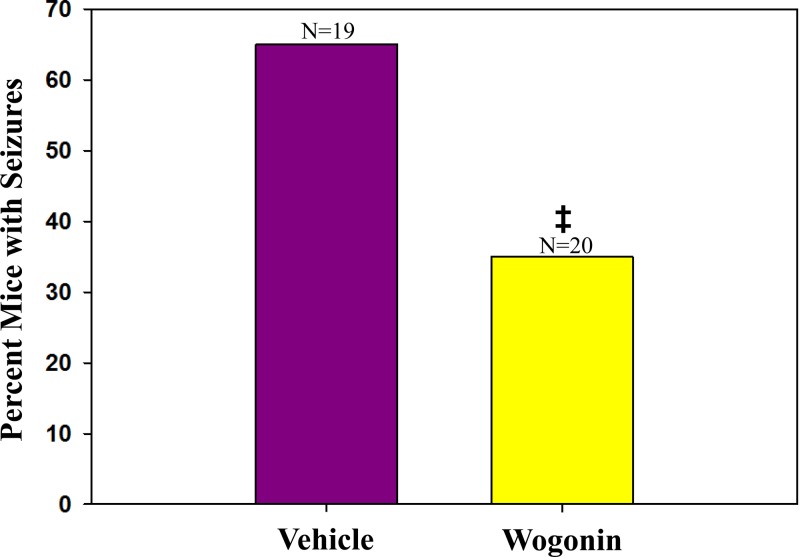

Previous work by our laboratory using the TMEV-induced seizure model demonstrated that minocycline was able to significantly inhibit the number of mice having seizures by approximately half (16, 39). Therefore, to determine if wogonin had a similar effect as minocycline on the number of mice having seizures, TMEV-infected C57BL/6 mice were treated with either vehicle (DMSO) or wogonin (3 mg/kg/day) and monitored daily for seizures. Mice treated with wogonin had significantly fewer seizures (35%) than vehicle-treated mice (63%; P < 0.05) (Fig. 11). This was about a 2-fold reduction in the number of mice having seizures, similar to the 2-fold reduction in the number of mice having seizures following minocycline treatment and similar to the 2-fold reduction in the number of infiltrating macrophages following treatment with wogonin. These results indicate that the inhibition of macrophages by 2-fold could potentially have a therapeutic benefit.

Fig 11.

Seizure frequencies (Racine scale, stages 3 to 5) in wogonin- and vehicle-treated mice. C57BL/6 mice infected with TMEV were treated, as described in Materials and Methods, with either vehicle (DMSO) or wogonin and monitored for seizures. Wogonin-treated mice had significantly fewer seizures (35%) than vehicle-treated mice (63%). ‡, P < 0.05, chi-square test. The total number of mice infected is shown above each individual bar in the graph. The percentage of mice was determined based on the number of mice with seizures divided by the total number of mice infected for each group, × 100.

DISCUSSION

The role of the immune system in seizures/epilepsy is largely unknown; however, evidence of proinflammatory mechanisms being involved in seizures/epilepsy has been described in experimental models (reviewed in reference40). Previous studies performed in our TMEV-induced seizure model demonstrated that the inhibition of monocytes resulted in significantly fewer mice experiencing seizures; therefore, monocyte-derived cells (microglia and macrophages) contributed to the induction of seizures (reviewed in reference1). In this study, we found a significantly higher number of macrophages in the brains of TMEV-infected mice that had seizures than in mock-infected mice. Furthermore, treatment with the anti-inflammatory compounds wogonin and minocycline significantly reduced the number of macrophages infiltrating the brain. Therefore, infiltrating macrophages drive acute seizures during viral infection, likely through IL-6 production.

Various cell types of the innate immune system have been hypothesized to be involved in the induction of seizures, including monocytes and neutrophils (41). Mononuclear cell infiltration in epilepsy has been described in mesial temporal lobe epilepsy (TLE) patients; based on the pan-mononuclear cell marker anti-CD45 antibody, a higher number of mononuclear cells (CD45+) were observed in the hippocampus of mesial TLE patients compared to control non-mesial TLE stained tissue sections (42, 43). This suggests widespread activation of the innate immune system in epileptic patients (42, 43). Consistent with these reports, in the present study, cells isolated from TMEV-infected mouse brains had a significantly higher number of mononuclear cells (CD45+) (data not shown). Furthermore, phenotypic analyses of TMEV-infected mouse brain cells clearly showed macrophages (CD45hi CD11b+) as being the major mononuclear cell population infiltrating the brain at day 3 p.i. (Fig. 2 and 4).

We examined the role of neutrophils in our previous studies by depleting neutrophils through the administration of the anti-granulocyte differentiation antigen-1 (Gr-1) antibody (clone RB6-8C5) (16). We found that there was no significant effect on the number of mice having seizures (16). However, a study using a different seizure model identified infiltrating neutrophils in the brains of mice that had seizures when examined after day 7 of seizure induction (43). The anti-Gr-1 antibody (clone RB6-8C5) has been shown to be nonspecific for neutrophils (44); therefore, we verified that the majority of cells in the CD45hi CD11b+ R2 population were monocytes, as opposed to neutrophils, by sorting the R2 population of cells and performing hematoxylin and eosin staining (Fig. 4C and D). Taken together, these results suggest that neutrophils could be involved in the development of epilepsy, but not in the induction of acute seizures during viral encephalitis (16, 41, 43).

Through the use of GFP chimeric mice, we demonstrated that monocyte-derived CD11b+ GFP+ cells were present in the brain following TMEV infection (Fig. 5B and C). In turn, we showed that these GFP+ cells were infiltrating macrophages (Fig. 5A). Further analysis of these TMEV-infected GFP chimeric mice showed that those mice that experienced seizures had a significantly higher number of GFP+ cells (infiltrating macrophages) in the brain tissue sections versus TMEV-infected GFP chimeric mice that did not have seizures (Fig. 6). Therefore, these results demonstrate a link between macrophage infiltration and mice experiencing seizures.

Activated microglia and macrophages release inflammatory cytokines, prostaglandins, and nitric oxide, possibly leading to neuronal excitability and neuronal damage (45). In our study, TMEV-infected mice had significantly higher expression of MHC class II and CD86 on monocytes, indicating that microglia and macrophages were highly activated (Fig. 3). Furthermore, in our model, fewer IL-6-deficient and TNF receptor 1 knockout mice infected with TMEV experienced seizures than did wild-type infected mice, implicating both IL-6 and TNF-α in the pathogenesis of seizures (15, 16, 39). However, the pathological changes in mice experiencing seizures were consistent, regardless of the mouse genetic background, suggesting that the amount, timing, and the type of cell producing these cytokines could be factors in cytokines having a pathogenic role in viral encephalitis-induced seizures. For example, exercise-induced IL-6 production in the CNS has been shown to decrease apoptosis of dentate granule neurons in the hippocampus after chemical treatment in mice that exercised compared to mice that did not exercise (46). Conversely, overexpression of IL-6, a key activator of astrocytes and microglia, above a theoretical threshold leads to immunopathology, including severe motor impairments, in various models (47, 48). Single-cell analysis of brain cells demonstrated that both microglia and macrophages produced TNF-α and IL-6 in TMEV-infected mice (Fig. 7). However, significantly more infiltrating macrophages were IL-6+ versus resident microglia (Fig. 7). Conversely, resident microglia had a significantly higher number of TNF-α+ cells than infiltrating macrophages (Fig. 7). Taken together, the increase in IL-6-producing macrophages infiltrating the brain, in conjunction with resident microglia producing TNF-α, could be elevating the levels of proinflammatory cytokines above a protective/reparative threshold to a pathological state, causing neuronal excitability, damage, and seizures. Once the threshold to a pathological state is crossed during viral encephalitis, the mice will experience seizures and have similar pathology due to the antiviral immune response, thereby accounting for the observation that the immunopathology in the mice that have seizures is similar between mice regardless of the viral titer (32). However, the role(s) of astrocytes and other resident CNS cells producing these cytokines has not yet been characterized. Therefore, further experiments are needed to characterize the role(s) of IL-6 and TNF-α in the induction of seizures.

The inhibition of seizures with anti-inflammatory compounds has provided indirect experimental evidence that inflammation is important in the induction of seizures (49–51). For example, administration of minocycline prior to kainic acid (KA)-induced status epilepticus significantly decreased the number of activated microglia in the hippocampus (49). Furthermore, administration of minocycline to TMEV-infected mice resulted in significantly fewer mice having seizures (16, 39). However, these studies did not determine the effect of minocycline on peripheral macrophages (16, 39, 49). In our study, minocycline administered to TMEV-infected mice significantly reduced the number of macrophages infiltrating the brains by approximately 2-fold (Fig. 10). Another potential anti-convulsive compound, wogonin (52), was administering to TMEV-infected mice. Similar to minocycline, wogonin treatment resulted in an approximately 2-fold decrease in infiltrating macrophages (Fig. 10) and significantly fewer mice experiencing seizures (Fig. 11). Taken together, these results link the number of infiltrating macrophages to the number of mice experiencing seizures. Unfortunately, a potential side effect of an anti-inflammatory compound is the suppression of the immune response to a pathogen. This could leave the host susceptible to viral persistence and/or opportunistic infection. However, in our study, immunohistochemical staining (on days 14 and 21 p.i.) for TMEV on brain tissue sections of vehicle-treated and wogonin-treated TMEV-infected mice showed no difference in the number of cells containing TMEV antigen (data not shown). Whether wogonin targets activated TMEV-specific T cells is not known; however, due to the low concentration of wogonin administered, a certain percentage of activated TMEV-specific T cells may escape targeting and be sufficient for viral clearance. These results are in agreement with previous reports that demonstrated wogonin specifically targeted activated cells and not resting immune cells (36, 53). Therefore, wogonin-treated mice are able to clear TMEV, even though wogonin inhibits activated macrophages.

In conclusion, these results demonstrate a role for infiltrating macrophages as a pathological mechanism in the induction of acute seizures, possibly through secretion of IL-6 in the CNS. Furthermore, administration of anti-inflammatory compounds, such as wogonin, in the treatment of seizures could provide a nontoxic therapeutic approach for seizures/epilepsy, and work is under way to determine the mechanism of action that wogonin may use on IL-6-producing cells to inhibit seizures in the CNS.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the Emma Mary Deland Foundation and NIH grants 5R01NS065714-03 (R.S.F.) and T32AI055434 (M.F.C.).

We thank Nikki J. Kennett, Braden T. McElreath, Lincoln R. Neugebauer, and Samantha Lee for technical assistance, Christian Niedzwecki for thoughtful discussions on problems with which clinicians are posed in treating seizure patients in the clinic, and Kathleen Borick and Daniel J. Harper for the outstanding preparation of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 5 December 2012

REFERENCES

- 1. Libbey JE, Fujinami RS. 2011. Neurotropic viral infections leading to epilepsy: focus on Theiler's murine encephalomyelitis virus. Future Virol. 6:1339–1350 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Verboon-Maciolek MA, Krediet TG, Gerards LJ, de Vries LS, Groenendaal F, van Loon AM. 2008. Severe neonatal parechovirus infection and similarity with enterovirus infection. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 27:241–245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Verboon-Maciolek MA, Krediet TG, Gerards LJ, Fleer A, van Loon TM. 2005. Clinical and epidemiologic characteristics of viral infections in a neonatal intensive care unit during a 12-year period. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 24:901–904 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Wolthers KC, Benschop KS, Schinkel J, Molenkamp R, Bergevoet RM, Spijkerman IJ, Kraakman HC, Pajkrt D. 2008. Human parechoviruses as an important viral cause of sepsis-like illness and meningitis in young children. Clin. Infect. Dis. 47:358–363 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Libbey JE, Kirkman NJ, Smith MCP, Tanaka T, Wilcox KS, White HS, Fujinami RS. 2008. Seizures following picornavirus infection. Epilepsia 49:1066–1074 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Stewart K-AA, Wilcox KS, Fujinami RS, White HS. 2010. Theiler's virus infection chronically alters seizure susceptibility. Epilepsia 51:1418–1428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Theiler M. 1937. Spontaneous encephalomyelitis of mice, a new virus disease. J. Exp. Med. 65:705–719 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Theiler M, Gard S. 1940. Encephalomyelitis of mice. I. Characteristics and pathogenesis of the virus. J. Exp. Med. 72:49–67 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hou W, So EY, Kim BS. 2007. Role of dendritic cells in differential susceptibility to viral demyelinating disease. PLoS Pathog. 3:e124 doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.0030124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Olson JK, Girvin AM, Miller SD. 2001. Direct activation of innate and antigen-presenting functions of microglia following infection with Theiler's virus. J. Virol. 75:9780–9789 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Palma JP, Kim BS. 2001. Induction of selected chemokines in glial cells infected with Theiler's virus. J. Neuroimmunol. 117:166–170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Sethi P, Lipton HL. 1983. Location and distribution of virus antigen in the central nervous system of mice persistently infected with Theiler's virus. Br. J. Exp. Pathol. 64:57–65 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Chang JR, Zaczynska E, Katsetos CD, Platsoucas CD, Oleszak EL. 2000. Differential expression of TGF-β, IL-2, and other cytokines in the CNS of Theiler's murine encephalomyelitis virus-infected susceptible and resistant strains of mice. Virology 278:346–360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Inoue A, Koh C-S, Yahikozawa H, Yanagisawa N, Yagita H, Ishihara Y, Kim BS. 1996. The level of tumor necrosis factor-alpha producing cells in the spinal cord correlates with the degree of Theiler's murine encephalomyelitis virus-induced demyelinating disease. Int. Immunol. 8:1001–1008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kirkman NJ, Libbey JE, Wilcox KS, White HS, Fujinami RS. 2010. Innate but not adaptive immune responses contribute to behavioral seizures following viral infection. Epilepsia 51:454–464 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Libbey JE, Kennett NJ, Wilcox KS, White HS, Fujinami RS. 2011. Interleukin-6, produced by resident cells of the central nervous system and infiltrating cells, contributes to the development of seizures following viral infection. J. Virol. 85:6913–6922 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Rubio N, Sanz-Rodriguez F, Lipton HL. 2006. Theiler's virus induces the MIP-2 chemokine (CXCL2) in astrocytes from genetically susceptible but not from resistant mouse strains. Cell. Immunol. 239:31–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Theil DJ, Tsunoda I, Libbey JE, Derfuss TJ, Fujinami RS. 2000. Alterations in cytokine but not chemokine mRNA expression during three distinct Theiler's virus infections. J. Neuroimmunol. 104:22–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Libbey JE, Kirkman NJ, Wilcox KS, White HS, Fujinami RS. 2010. Role for complement in the development of seizures following acute viral infection. J. Virol. 84:6452–6460 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Zurbriggen A, Fujinami RS. 1989. A neutralization-resistant Theiler's virus variant produces an altered disease pattern in the mouse central nervous system. J. Virol. 63:1505–1513 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Liu F, Whitton JL. 2005. Cutting edge: re-evaluating the in vivo cytokine responses of CD8+ T cells during primary and secondary viral infections. J. Immunol. 174:5936–5940 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Tsunoda I, Wada Y, Libbey JE, Cannon TS, Whitby FG, Fujinami RS. 2001. Prolonged gray matter disease without demyelination caused by Theiler's murine encephalomyelitis virus with a mutation in VP2 puff B. J. Virol. 75:7494–7505 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Benkovic SA, O'Callaghan JP, Miller DB. 2004. Sensitive indicators of injury reveal hippocampal damage in C57BL/6J mice treated with kainic acid in the absence of tonic-clonic seizures. Brain Res. 1024:59–76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Racine RJ. 1972. Modification of seizure activity by electrical stimulation. II. Motor seizure. Electroencephalogr. Clin. Neurophysiol. 32:281–294 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ginhoux F, Greter M, Leboeuf M, Nandi S, See P, Gokhan S, Mehler MF, Conway SJ, Ng LG, Stanley ER, Samokhvalov IM, Merad M. 2010. Fate mapping analysis reveals that adult microglia derive from primitive macrophages. Science 330:841–845 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ford AL, Goodsall AL, Hickey WF, Sedgwick JD. 1995. Normal adult ramified microglia separated from other central nervous system macrophages by flow cytometric sorting. Phenotypic differences defined and direct ex vivo antigen presentation to myelin basic protein-reactive CD4+ T cells compared. J. Immunol. 154:4309–4321 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Sedgwick JD, Schwender S, Imrich H, Dorries R, Butcher GW, ter Meulen V. 1991. Isolation and direct characterization of resident microglial cells from the normal and inflamed central nervous system. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 88:7438–7442 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. de Groot CJ, Huppes W, Sminia T, Kraal G, Dijkstra CD. 1992. Determination of the origin and nature of brain macrophages and microglial cells in mouse central nervous system, using non-radioactive in situ hybridization and immunoperoxidase techniques. Glia 6:301–309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Hickey WF, Vass K, Lassmann H. 1992. Bone marrow-derived elements in the central nervous system: an immunohistochemical and ultrastructural survey of rat chimeras. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 51:246–256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Krall WJ, Challita PM, Perlmutter LS, Skelton DC, Kohn DB. 1994. Cells expressing human glucocerebrosidase from a retroviral vector repopulate macrophages and central nervous system microglia after murine bone marrow transplantation. Blood 83:2737–2748 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Matsumoto Y, Fujiwara M. 1987. Absence of donor-type major histocompatibility complex class I antigen-bearing microglia in the rat central nervous system of radiation bone marrow chimeras. J. Neuroimmunol. 17:71–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Libbey JE, Kennett NJ, Wilcox KS, White HS, Fujinami RS. 2011. Lack of correlation of central nervous system inflammation and neuropathology with the development of seizures following acute virus infection. J. Virol. 85:8149–8157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Akassoglou K, Probert L, Kontogeorgos G, Kollias G. 1997. Astrocyte-specific but not neuron-specific transmembrane TNF triggers inflammation and degeneration in the central nervous system of transgenic mice. J. Immunol. 158:438–445 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Kalueff AV, Lehtimaki KA, Ylinen A, Honkaniemi J, Peltola J. 2004. Intranasal administration of human IL-6 increases the severity of chemically induced seizures in rats. Neurosci. Lett. 365:106–110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Probert L, Akassoglou K, Pasparakis M, Kontogeorgos G, Kollias G. 1995. Spontaneous inflammatory demyelinating disease in transgenic mice showing central nervous system-specific expression of tumor necrosis factor alpha. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 92:11294–11298 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Fas SC, Baumann S, Zhu JY, Giaisi M, Treiber MK, Mahlknecht U, Krammer PH, Li-Weber M. 2006. Wogonin sensitizes resistant malignant cells to TNFalpha- and TRAIL-induced apoptosis. Blood 108:3700–3706 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Shao ZH, Li CQ, Vanden Hoek TL, Becker LB, Schumacker PT, Wu JA, Attele AS, Yuan CS. 1999. Extract from Scutellaria baicalensis Georgi attenuates oxidant stress in cardiomyocytes. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 31:1885–1895 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Riazi K, Galic MA, Kuzmiski JB, Ho W, Sharkey KA, Pittman QJ. 2008. Microglial activation and TNFα production mediate altered CNS excitability following peripheral inflammation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 105:17151–17156 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Libbey JE, Kennett NJ, Wilcox KS, White HS, Fujinami RS. 2011. Once initiated, viral encephalitis-induced seizures are consistent no matter the treatment or lack of interleukin-6. J. Neurol. Virol. 17:496–499 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Vezzani A. 2005. Inflammation and epilepsy. Epilepsy Curr. 5:1–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Fabene PF, Mora GN, Martinello M, Rossi B, Merigo F, Ottoboni L, Bach S, Angiari S, Benati D, Chakir A, Zanetti L, Schio F, Osculati A, Marzola P, Nicolato E, Homeister JW, Xia L, Lowe JB, McEver RP, Osculati F, Sbarbati A, Butcher EC, Constantin G. 2008. A role for leukocyte-endothelial adhesion mechanisms in epilepsy. Nat. Med. 14:1377–1383 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Loup F, Wieser HG, Yonekawa Y, Aguzzi A, Fritschy JM. 2000. Selective alterations in GABAA receptor subtypes in human temporal lobe epilepsy. J. Neurosci. 20:5401–5419 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Zattoni M, Mura ML, Deprez F, Schwendener RA, Engelhardt B, Frei K, Fritschy JM. 2011. Brain infiltration of leukocytes contributes to the pathophysiology of temporal lobe epilepsy. J. Neurosci. 31:4037–4050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Daley JM, Thomay AA, Connolly MD, Reichner JS, Albina JE. 2008. Use of Ly6G-specific monoclonal antibody to deplete neutrophils in mice. J. Leukoc. Biol. 83:64–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Nadeau S, Rivest S. 2000. Role of microglial-derived tumor necrosis factor in mediating CD14 transcription and nuclear factor κB activity in the brain during endotoxemia. J. Neurosci. 20:3456–3468 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Funk JA, Gohlke J, Kraft AD, McPherson CA, Collins JB, Harry GJ. 2011. Voluntary exercise protects hippocampal neurons from trimethyltin injury: possible role of interleukin-6 to modulate tumor necrosis factor receptor-mediated neurotoxicity. Brain Behav. Immun. 25:1063–1077 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Bauer S, Kerr BJ, Patterson PH. 2007. The neuropoietic cytokine family in development, plasticity, disease and injury. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 8:221–232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Lacroix S, Chang L, Rose-John S, Tuszynski MH. 2002. Delivery of hyper-interleukin-6 to the injured spinal cord increases neutrophil and macrophage infiltration and inhibits axonal growth. J. Comp. Neurol. 454:213–228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Abraham J, Fox PD, Condello C, Bartolini A, Koh S. 2012. Minocycline attenuates microglia activation and blocks the long-term epileptogenic effects of early-life seizures. Neurobiol. Dis. 46:425–430 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Marchi N, Fan Q, Ghosh C, Fazio V, Bertolini F, Betto G, Batra A, Carlton E, Najm I, Granata T, Janigro D. 2009. Antagonism of peripheral inflammation reduces the severity of status epilepticus. Neurobiol. Dis. 33:171–181 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Maroso M, Balosso S, Ravizza T, Liu J, Aronica E, Iyer AM, Rossetti C, Molteni M, Casalgrandi M, Manfredi AA, Bianchi ME, Vezzani A. 2010. Toll-like receptor 4 and high-mobility group box-1 are involved in ictogenesis and can be targeted to reduce seizures. Nat. Med. 16:413–419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Park HG, Yoon SY, Choi JY, Lee GS, Choi JH, Shin CY, Son KH, Lee YS, Kim WK, Ryu JH, Ko KH, Cheong JH. 2007. Anticonvulsant effect of wogonin isolated from Scutellaria baicalensis. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 574:112–119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Polier G, Ding J, Konkimalla BV, Eick D, Ribeiro N, Kohler R, Giaisi M, Efferth T, Desaubry L, Krammer PH, Li-Weber M. 2011. Wogonin and related natural flavones are inhibitors of CDK9 that induce apoptosis in cancer cells by transcriptional suppression of Mcl-1. Cell Death Dis. 2:e182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]