Abstract

Steroidogenic factor 1 (SF-1 or NR5A1) is a nuclear receptor that controls adrenogenital cell growth and differentiation. Adrenogenital primordial cells from SF-1 knockout mice die of apoptosis, but the mechanism by which SF-1 regulates cell survival is not entirely clear. Besides functioning in the nucleus, SF-1 also resides in the centrosome and controls centrosome homeostasis. Here, we show that SF-1 restricts centrosome overduplication by inhibiting aberrant activation of DNA-dependent protein kinase (DNA-PK) in the centrosome. SF-1 was found to be associated with Ku70/Ku80 only in the centrosome, sequestering them from the catalytic subunit of DNA-PK (DNA-PKcs). In the absence of SF-1, DNA-PKcs was recruited to the centrosome and activated, causing aberrant activation of centrosomal Akt and cyclin-dependent kinase 2 (CDK2)/cyclin A and leading to centrosome overduplication. Centrosome overduplication caused by SF-1 depletion was averted by the elimination of DNA-PKcs, Ku70/80, or cyclin A or by the inhibition of CDK2 or Akt. In the nucleus, SF-1 did not interact with Ku70/80, and SF-1 depletion did not activate a nuclear DNA damage response. Centriole biogenesis was also unaffected. Thus, centrosomal DNA-PK signaling triggers centrosome overduplication, and this centrosomal event, but not the nuclear DNA damage response, is controlled by SF-1.

INTRODUCTION

Steroidogenic factor 1 (SF-1; Ad4BP or NR5A1) is a transcription factor in the nuclear receptor superfamily expressed mainly in the adrenals, gonads, and parts of the brain. It regulates expression of genes involved in reproduction, metabolism, and other endocrine functions by binding to specific DNA sequences (1, 2). In addition to transcriptional activation, SF-1 also plays an important role in adrenogonadal development (3). The adrenals and gonads in Sf-1 null mice are lost due to the apoptosis of adrenogenital primordial cells during embryonic development (3), indicating the requirement of SF-1 for proper growth of adrenal glands and gonads.

The mechanism by which SF-1 regulates adrenogenital cell growth is still not clear. SF-1 may activate genes involved in cell proliferation (4). In addition, SF-1 also regulates adrenal cell growth by maintaining centrosome homeostasis (5). When SF-1 is depleted in adrenocortical cells, centrosomes undergo overduplication, resulting in aberrant mitosis and apoptosis.

The centrosome is composed of a pair of perpendicular microtubule cylinders (centrioles) and the surrounding pericentriolar materials (PCM). It is the primary microtubule-organizing center during the interphase of the cell cycle. During mitosis, the centrosomes form spindle poles that facilitate equal separation of duplicated chromosomes. Thus, centrosome homeostasis is important for the maintenance of genomic integrity (6, 7).

During each cell cycle, centrosomes duplicate once in a tightly controlled manner in coordination with DNA replication (7–9). Like DNA replication, centrosome duplication requires cyclin-dependent kinase 2 (CDK2) (10). Phosphorylation of CP110, Mps1, and nucleophosmin (NPM) by CDK2 causes the initiation of centrosome duplication (11–13). Centrosome overduplication is uncoupled from DNA replication when the levels of cyclin-CDK2 complexes are elevated. Thus, the precise control of CDK2 activity is important to maintain centrosome homeostasis.

CDK2 activity is also tightly coordinated with genomic DNA integrity. When cells suffer from sever DNA damage, CDK2 is activated by DNA damage checkpoint proteins, resulting in centrosome amplification and cell death (14, 15). This DNA damage checkpoint protein-regulated event prevents tumorigenesis by eliminating cells with unrepaired genome (16).

DNA damage checkpoint proteins, like ataxia telangiectasia mutated (ATM), ATM- and Rad3-related (ATR), and DNA-dependent protein kinase (DNA-PK), are activated to repair damaged genome (16). Among these proteins, DNA-PK participates in the repair of DNA double-strand breaks (17). In the presence of DNA double-strand breaks, Ku70/Ku80 heterodimers are recruited to the break sites followed by recruitment of the catalytic subunit of DNA-PK (DNA-PKcs) to form an active DNA-PK. Once DNA-PK is activated, its downstream effectors are recruited to the damaged sites to repair damaged genome. In addition, DNA-PK also plays an important role in maintaining cell cycle arrest and cell survival by activating Akt signaling upon DNA damage (18). Thus, DNA-PK has multiple functions in response to DNA damage.

DNA-PK resides in both the nucleus and the centrosome (19). Unlike those of nuclear DNA-PK, neither the function nor the regulation of centrosomal DNA-PK has been carefully investigated. Here, we demonstrate that proper regulation of centrosomal DNA-PK is important for centrosome homeostasis, and centrosome-associated DNA-PK activity in the interphase of adrenocortical Y1 and testicular Leydig MA10 cells is regulated by nuclear receptor SF-1. We found that SF-1 interacted and sequestered Ku70 and Ku80 from DNA-PKcs in the centrosome of Y1 cells. The depletion of SF-1 led to the recruitment of DNA-PKcs followed by the activation of Akt and CDK2/cyclin A in the centrosome, leading to centrosome overduplication. Thus, we have uncovered a novel role of nuclear receptor SF-1 in the centrosome that prevents centrosome overduplication by limiting the activation of centrosomal DNA-PK.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plasmids.

The pcDNA5-3-FLAG-SF-1 plasmid has been described previously (20). Y1 cells were transfected with pcDNA5-3-FLAG-SF-1 using Lipofectamine and Plus reagents (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Cell culture and drug treatment.

Mouse adrenocortical Y1 and mouse Leydig tumor MA-10 cells were grown in Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium (DMEM)–F-12 medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere at 5% CO2. Human embryonic kidney 293FT cells were grown in DMEM and 10% fetal bovine serum at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere at 5% CO2. These cells were regularly examined for the presence of SF-1 and were free of mycoplasma contamination by immunoblotting, immunofluorescence, and 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) staining according to the guidelines. For drug treatment, cells were incubated alone or with 10 μM roscovitine or 100 nM CDK2 inhibitor II (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany), 2 mM hydroxyurea (HU), 1 mM vanillin, 2 mM caffeine, 50 μM Akt inhibitor (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany), 10 μM KU-55933, or 10 μM Chk2 inhibitor II (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) for 24 h before analysis. For induction of the DNA damage response, cells were treated with 100 μM etoposide for 2 h.

Subcellular fractionation and centrosomal protein extraction.

Subcellular fractions and crude centrosomes were prepared by modifying a published procedure (21). Briefly, 4 × 109 cells were treated with nocodazole (10 μg/ml) and cytochalasin B (5 μg/ml) for 60 min, followed by sequential washes with cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), 8% (wt/wt) sucrose in 0.1× PBS, and 10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0. Cells were then lysed in lysis buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 0.5% NP-40, and 0.1% β-mercaptoethanol), and the cell lysate was centrifuged at 2,000 × g. The nuclear pellet was further lysed with lysis buffer containing 0.5% NP-40, 300 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, and the protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche, Mannhein, Germany).

The cytoplasmic fraction was centrifuged again at 10,000 × g for 1 h on a 50% sucrose (wt/wt) cushion layer. Supernatant was removed, and the resulting sucrose cushion containing the concentrated centrosome was centrifuged over discontinuous 65, 50, and 40% (wt/wt) sucrose for Y1 at 35,000 × g. Samples (300 μl/fraction) were collected from the bottom of the tube, and the crude centrosomes were enriched in sucrose fraction 5 at about 45 to 50% density.

Centrosomal protein was extracted from sucrose fraction 5 by modifying a previously described procedure (22). Sucrose fraction 5 was agitated in 20 ml of extraction buffer containing 20 mM Tris, pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM dithiothreitol (DTT), 2 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF), and the protease and phosphatase inhibitor cocktail (Roche, Mannheim, Germany) on ice for 30 min, followed by centrifugation at 15,000 rpm at 4°C for 10 min. The supernatant was concentrated on an Amicon filter (10-kDa cutoff, 5% bovine serum albumin [BSA] preblocked; Millipore, MA) by centrifugation at 4,000 × g at 4°C for 1 h. The aggregate in the protein concentrate was removed by centrifugation at 15,000 rpm for 30 min, and the supernatant was used as centrosome extracts.

Tetracycline-inducible cDNA expression and RNA interference (RNAi).

Lentiviral systems for gene silencing and tetracycline-inducible cDNA expression were obtained from the Taiwan National RNAi Core Facility. The pTrip-aOn plasmid was constructed by inserting the coding sequence of the Tet-On advanced transcriptional activator into pTrip-IRES-neo downstream from the elongation factor 1 alpha promoter. The pAS4w-EYFP and pAS4w-SF-1 plasmids were constructed by inserting the SF-1 or enhanced yellow fluorescent protein (EYFP) coding sequence into pAS4w.1.Pbsd, which contains seven copies of modified tetO sequence. For tetracycline-inducible SF-1 overexpression, Y1 cells were infected with pTrip-aOn lentivirus at a multiplicity of infection of 3 and incubated for 24 h before G418 (500 μg/ml) selection. After selection, pooled G418-resistant cells were infected again by the pAS4w-EYFP or pAS4w-SF1 lentivirus at a multiplicity of infection of 3 and incubated for 24 h before selection by 10 μg/ml blasticidin. The surviving cells were pooled and amplified for use in subsequent experiments. To induce SF-1 expression, cells were treated with 1 μg/ml doxycycline for 48 h.

Sequences of short hairpin RNA (shRNA) in the pLKO.1 vector are the following: pLKO.1-shluc (target sequence, 5′-CCTAAGGTTAAGTCGCCCTCG-3′), pLKO.1-shsf1#2 (target sequence, 5′-CGCACCATCAAGTCTGAGTAT-3′), pLKO.1-shsf1#3 (target sequence, 5′-CGTCTGTCTCAAGTTCCTCAT-3′), pLKO.1-shCCNA2#2 (target sequence, 5′-CCTGACTATCAAGAAGACATT-3′), pLKO.1-shCCNA2#5 (target sequence, 5′-GCTTCGAAGTTTGAAGAAATA-3′), pLKO.1-shDNAPKcs#5 (target sequence, 5′-GCTGCATACAACTGTGCCATT-3′), pLKO.1-shKu70#1 (target sequence, 5′-AGCTCAGAAGCCCAGCCACTT-3′), and pLKO.1-shKu80#3 (target sequence, 5′-CGGAAGTGATATCATTCCTTT-3′).

Lentiviruses were collected from media of 293FT cells cotransfected with pLKO.1-derived plasmids and packaging vectors pCMVdelR8.91 and pMD.G according to the protocols provided by the Taiwan National RNAi Core Facility.

Antibodies.

The following antibodies were obtained commercially: anti-γ-tubulin, polyclonal anti-FLAG, anti-cyclin A, monoclonal anti-FLAG M2, anti-α-tubulin, and anti-acetylated-α-tubulin (Sigma, St. Louis, MO); anti-CEP170 (Bethyl, Montgomery, TX); anti-CDK2, anti-cyclin E, anti-CDK2 phospho-Thr160, anti-Akt, anti-Akt phospho-Thr308, anti-ATR, and anti-ATR phospho-Ser428 (Cell Signaling, Beverly, MA); anti-centrin 20H5 (Millipore, Billerica, MA); polyclonal anticentrin, anti-Chk1, anti-Chk1 phospho-Ser345, and anti-H2AX phospho-Ser139 (Abcam, Cambridge, United Kingdom); anti-Ku70, anti-Ku80, and anti-ATM (Genetex, Trvine, CA); anti-ATM phospho-S1981 (Epitomics, Burlingame, CA); anti-Odf2, anti-hnRNP A1, anti-DNA-PKcs, and anti-DNA-PKcs phospho-Thr 2609 (Santa Cruz Biotech, Santa Cruz, CA); and anti-mitochondrial complex II (MitoSciences, Eugene, OR). The immune sera against SF-1 (23) have been described previously.

Immunoprecipitation assay.

Protein extracts were incubated with specific antibodies for 1 h at 4°C before further incubation with protein G beads for 1 h at 4°C. The beads were washed with buffer containing 10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 120 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM PMSF, and the protease and phosphatase inhibitor cocktail. The samples were eluted with FLAG peptide or sample buffer.

Immunofluorescence microscopy.

Cells were grown on glass coverslips at 37°C before fixation with ice-cold methanol at −20°C for 6 min. To visualize centriolar acetylated α-tubulin staining, cells were treated with 30 μM nocodazole on ice for 1 h to depolymerize microtubule networks, followed by brief extraction with saponin (200 ng/10 ml) for 2 min and being fixed with ice-cold methanol for 5 min. After blocking with 5% BSA for 1 h, cells were incubated with antibodies for 24 h at 4°C. After extensive washing with PBS, cells were incubated with fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated and Cy3-conjugated secondary antibodies (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) for 1 h in the dark. The nuclei were stained with DAPI (0.1 μg/ml) simultaneously. After extensive washing, the coverslips were mounted in 50% glycerol on glass slides. Fluorescent cells were examined with an AxioImager Z1 fluorescence microscope or an LSM 510 confocal microscope (both from Zeiss, Switzerland). The number of centrosomes and centrioles from more than 100 cells was counted under the microscope in three independent experiments and shown as means ± standard deviations (SD). Student's t test was performed to analyze the differences between groups. The fluorescence intensity in the region of centrosome as defined by γ-tubulin signal (in μm2) was quantified by MetaMorph software (Molecular Devices, Downingtown, PA).

RESULTS

SF-1 prevents centrosome overduplication without disturbing centriole biogenesis.

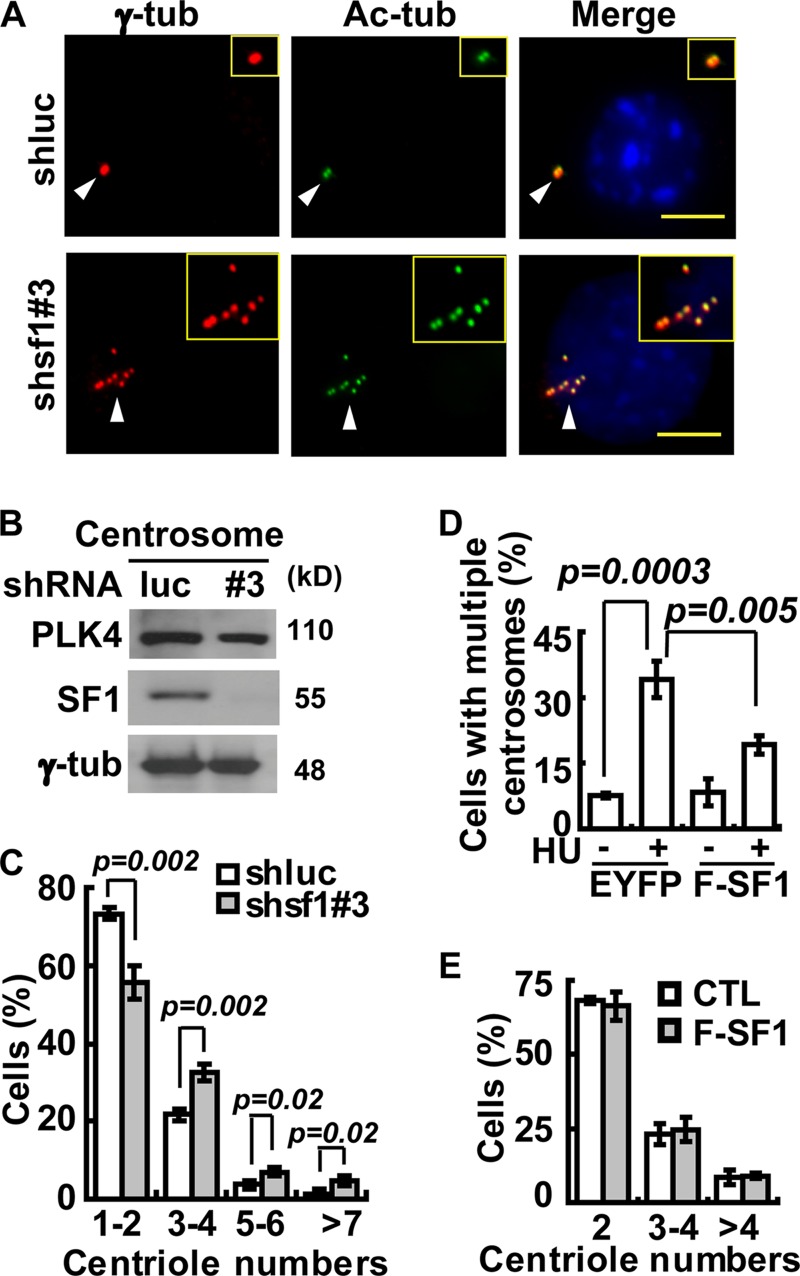

We have previously found that SF-1 resides in both the nucleus and centrosomes (5). Here, we found that SF-1 was present at the centriole at all cell cycle stages, including the interphase and mitosis (see Fig. S1A in the supplemental material). To investigate the role of centrosome-associated SF-1 further, the centrosomes in SF-1-deficient Y1 cells were examined by staining with either γ-tubulin or with acetylated tubulin after microtubule depolymerization (Fig. 1A). After SF-1 depletion by shsf1#3, centrioles appeared scattered, reminiscent of those found in hydroxyurea (HU)-treated cells (10) but different from the rosette centriole structure typical of PLK4 overexpression (24). Indeed, the amount of PLK4 in the centrosome extracts of shsf1#3 Y1 cells was similar to that in the shluc control cells (Fig. 1B). Furthermore, immunofluorescence revealed normal amounts of centriolar proteins, like CPAP, centrin, SAS6, and CP110, in each centriole, even though there were multiple centrioles upon SF-1 depletion (see Fig. S1B). Immunoblot analysis also reveals normal levels of SAS6, CP110, and CEP170 in Y1 cells depleted of SF-1 by shsf1#2 or shsf1#3 (see Fig. S1C). Thus, proteins involved in centriole biogenesis were not affected by SF-1 depletion.

Fig 1.

SF-1 prevents centrosome overduplication during S phase without affecting PLK4. (A) SF-1 depletion induces formation of multiple centrioles. Immunofluorescence staining of centrioles with acetylated tubulin (Ac-tub) and of centrosomes with γ-tubulin (γ-tub) in shluc and shsf1#3 Y1 cells. Centrosomes are indicated by arrowheads. Scale bars are 5 μm. Insets are magnifications of centrioles. (B) SF-1 depletion does not affect PLK4. Immunoblot analysis of shluc (luc) or shsf1#3 (#3) Y1 centrosome extracts with antibodies against PLK4, SF-1, and γ-tubulin (γ-tub). (C) SF-1 depletion results in centriole overduplication. Quantification of centriole numbers in shluc and shsf1#3 cell populations is shown. (D) SF-1 overexpression inhibits hydroxyurea-induced centrosome amplification. Y1 cells overexpressing EYFP or F-SF1 were treated with hydroxyurea (HU) or left untreated. Quantification of EYFP and F-SF1 cell populations with centrosome amplification is shown. (E) SF-1 overexpression does not affect centriole duplication. Quantification of control (CTL) or F-SF1-overexpressing Y1 cells with different centriole numbers is shown. All quantitations are represented as means ± SD from three independent experiments, and more than 300 cells were counted in each group.

When counting the number of centrioles, we found that the populations of cells containing 1 to 2 centrioles (unduplicated) were reduced following SF-1 depletion, while those containing 3 to 4 centrioles (duplicated) and more than 4 centrioles (overduplicated centrioles) were increased (Fig. 1C). These data indicate that SF-1 has a role in the control of centrosome homeostasis but not centriole biogenesis.

We further tested the effect of SF-1 overexpression on centrosome numbers. Adrenocortical Y1 cell pools overexpressing FLAG-tagged SF-1 (F-SF-1) or EYFP under the control of doxycycline were generated. These cells were arrested in S phase by HU to allow more time for centrosome reduplication. Prolonged S phase led to an increase in the number of EYFP control cells that contained multiple centrosomes (Fig. 1D), yet this number was reduced in cells overexpressing F-SF-1. F-SF-1 overexpression, however, had no effect on centriole numbers (Fig. 1E), indicating that SF-1 overexpression did not disturb centriole biogenesis. Thus, both overexpression and loss-of-function data indicate that SF-1 inhibits centrosome overduplication.

SF-1 depletion induces centrosome overduplication by activating centrosomal CDK2/cyclin A.

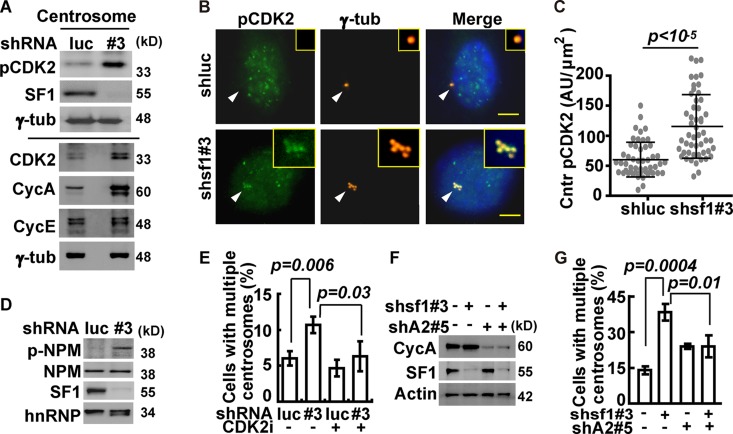

Since centriole duplication requires CDK2 (10), we examined CDK2 activity after SF-1 depletion. Larger amounts of CDK2 and active Thr160-phosphorylated CDK2 (pCDK2) were detected in the centrosome of shsf1#3 cells by immunoblotting (Fig. 2A) and by immunostaining (Fig. 2B and C). CDK2 activity, detected by the increased phosphorylation of its substrate nucleophosmin, was also increased in shsf1#3 cells (Fig. 2D). These data indicate that SF-1 depletion induces CDK2 activation in the centrosome.

Fig 2.

Centrosome overduplication caused by SF-1 depletion depends on centrosomal CDK2/cyclin A. Y1 cells were infected with shluc (luc) or shsf1#3 (#3) lentivirus before their centrosomes were quantified, and immunoblotting of cell or centrosomal extracts was performed with the respective antibodies indicated at the left of the gel. Results of quantification are shown as means ± SD from three independent experiments; more than 300 cells were measured in each group. (A) Accumulation of phosphorylated CDK2 in the centrosome following SF-1 depletion. (B and C) Phospho-Thr160 CDK2 (pCDK2) accumulates in the centrosome following SF-1 depletion. (B) Immunofluorescence staining of pCDK2 and γ-tubulin (γ-tub). Centrosomes are indicated by arrowheads. Scale bars are 5 μm. Insets are magnifications of centrosomes. (C) Quantification of centrosomal (Cntr) pCDK2 intensity revealed by γ-tubulin staining in arbitrary units (AU) divided by the area (μm2) of the centrosome. (D) Nucleophosmin in SF-1-deficient Y1 cells is hyperphosphorylated. Nuclear extracts of shluc (luc) or shsf1#3 (#3) lentivirus-infected Y1 cells were analyzed with antibodies against SF-1, nucleophosmin phosphorylated at Thr199 (p-NPM), nucleophosmin (NPM), and hnRNPA1 (hnRNP). (E) Centrosome overduplication depends on CDK2 in SF-1-deficient Y1 cells. Quantification of shluc (luc) and shsf1#3 (#3) cell populations with centrosome amplification in the presence or absence of CDK2 inhibitor II (CDK2i) is shown. (F) Efficient depletion of cyclin A and SF-1. Immunoblot analysis of Y1 cell extracts after protein depletion by shRNA against cyclin A (shA2#5) and shsf1#3, respectively, is shown. β-Actin (Actin) is used as a loading control. (G) Depletion of cyclin A by shA2#5 relieves cells of centrosome amplification caused by SF-1 depletion with shsf1#3.

When the activity of CDK2 was blocked by a specific inhibitor, CDK2 inhibitor II (CDK2i), the multiple-centrosome phenotype caused by shsf1#3 was suppressed (Fig. 2E). Inhibiting CDK2 activity by roscovitine in mouse testicular Leydig MA-10 cells also blocked the formation of multiple centrosomes caused by SF-1 depletion with shsf1#2 or shsf1#3 (see Fig. S1D in the supplemental material). Thus, centrosome overduplication induced by SF-1 depletion depends on CDK2 in both adrenocortical Y1 and Leydig MA-10 cells.

The cause of centrosomal CDK2 activation was further investigated. The levels of pCDK2, CDK2, cyclin E, and cyclin A in the nucleus or cytoplasm were not changed after SF-1 depletion by shsf1#3 (see Fig. S1E in the supplemental material). However, in the centrosomal fraction, the levels of CDK2 and cyclin A were increased after SF-1 depletion, while that of cyclin E was not changed (Fig. 2A). To confirm the role of cyclin A, we depleted it simultaneously with SF-1. Two shRNA sequences, shCCNA2#2 and shCCNA2#5, blocked cyclin A expression efficiently (Fig. 2F; also see Fig. S1F and G). Although cyclin A depletion by shCCNA2#5 induced centrosome amplification slightly, double depletion of cyclin A and SF-1 blocked centrosome overduplication caused by SF-1 depletion with shsf1#3 (Fig. 2G). Cyclin A depletion by the other sequence, shCCNA2#2, also yielded the same result (see Fig. S1G and H). Thus, cyclin A participates in centrosome overduplication induced by SF-1 depletion.

SF-1 interacts with Ku70 and Ku80 in the centrosome but not in the nucleus.

To investigate the mechanism by which SF-1 prevents centrosome overduplication, we first isolated centrosomes from Y1 extract by several centrifugation steps followed by discontinuous sucrose gradient ultracentrifugation using a published procedure (21). SF-1 and γ-tubulin were sedimented at the same fraction, number 5 (see Fig. S2A in the supplemental material), at about 45 to 50% sucrose (see Fig. S2B). This centrosome fraction was not contaminated by the nuclear and mitochondrial proteins in immunoblot analysis (see Fig. S2A). When the cell extract overexpressing FLAG-green fluorescent protein (GFP) was subjected to the same scheme, FLAG-GFP was present in the cytoplasmic and postcentrosomal supernatant fractions but not in the centrosomal fraction (see Fig. S2C). This further demonstrates the purity of our centrosomal fraction.

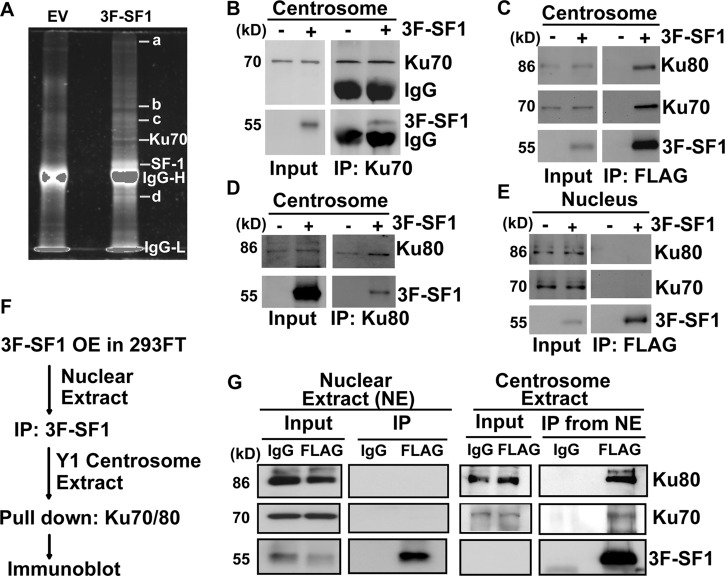

Proteins in centrosomal fraction 5 were extracted for further purification (see Fig. S2D in the supplemental material) according to an established protocol (22). While centriolar component proteins Odf2, acetylated tubulins, and SAS6 were refractory to extraction and remained in the pellet, SF-1, Ku70, and Ku80 were extracted efficiently into the supernatant (see Fig. S2E). SF-1 and its interacting proteins in the supernatant then were isolated by immunoprecipitation with anti-FLAG antibody from centrosomes of 4 × 109 Y1 cells overexpressing 3-FLAG-SF-1. Proteins in the immunoprecipitate were separated by gel electrophoresis (Fig. 3A). In addition to those of immunoglobulin (IgG) and SF-1, many proteins bands were present. One band of about 70 kDa was identified by mass spectrometry as autoantigen Ku70 (see Fig. S3A and B in the supplemental material).

Fig 3.

SF-1 interacts with Ku70/Ku80 in the centrosome but not the nucleus. (A) Gel electrophoresis of 3-FLAG-SF1 (3F-SF1) and its associated centrosomal proteins after immunoprecipitation (IP) with anti-FLAG antibody. EV, immunoprecipitates from cells overexpress empty vector only. IgG-H, IgG heavy chain; IgG-L, IgG light chain. Visible bands are marked by letters a to d. (B to D) SF-1 interacts with Ku70 and Ku80 in the centrosome. Centrosomal extracts of 3F-SF1-transfected Y1 cells were immunoprecipitated with anti-Ku70 (B), anti-FLAG (C), and anti-Ku80 (D) antibodies followed by immunoblotting with antibodies against FLAG, Ku70, and Ku80. (E) SF-1 does not interact with Ku70 and Ku80 in the nucleus. Nuclear extracts of 3F-SF1-transfected Y1 (E) or 293FT (G) cells were immunoprecipitated with anti-FLAG antibody or random IgG, followed by immunoblotting with antibodies against FLAG, Ku70, and Ku80. (F and G) 3F-SF1 from 293FT nuclear extracts pulls down Ku70/80 in Y1 centrosome extracts. (F) The scheme of the analysis. Nuclear extracts of 3F-SF1-transfected 293FT cells were immunoprecipitated with anti-FLAG antibody or random IgG followed by being pulled down with Y1 centrosomal extracts. (G) Immunoblot analysis with antibodies against FLAG, Ku70, and Ku80. NE, nuclear extract.

The interaction of Ku70 with 3-FLAG-SF-1 was confirmed by FLAG immunoblot analysis following coimmunoprecipitation of the centrosomal proteins with antibodies against Ku70 (Fig. 3B). Conversely, Ku70 was detected when centrosomal proteins were immunoprecipitated with 3-FLAG-SF-1 (Fig. 3C; also see Fig. S3C in the supplemental material). In addition, Ku80 was also present in the 3-FLAG-SF-1 immunoprecipitate (Fig. 3C; also see Fig. S3C) and vice versa (Fig. 3D). When the centrosome preparation was analyzed by gel filtration chromatography (see Fig. S3D), SF-1 was eluted at fraction 18 together with Ku70 and Ku80 in a complex of around 2 MDa (see Fig. S3E). Thus, combining data from mass spectrometry, immunoprecipitation, and size-exclusion chromatography, we conclude that SF-1 forms a complex with Ku70 and Ku80 in the centrosome.

Although Ku70/80 interacted with SF-1 in the centrosome, in the nuclear extract Ku70 and Ku80 were not coprecipitated by antibody against 3-FLAG-SF-1 (Fig. 3E). To confirm this, we overexpressed 3-FLAG-SF-1 in 293FT, a cell line devoid of SF-1, and the nuclear extracts were immunoprecipitated by antibody against 3-FLAG-SF-1 (Fig. 3F). Ku70 and Ku80 were not coprecipitated with SF-1 in the nuclear fraction of 293FT cells (Fig. 3G). However, when supplemented with centrosomal extract of Y1 cells, Ku70 and Ku80 were detected in the 3-FLAG-SF-1 immunoprecipitate of 293FT nuclear extract (Fig. 3G). This result indicates that Y1 centrosomal but not nuclear components are required for complex formation between SF-1 and Ku70/Ku80.

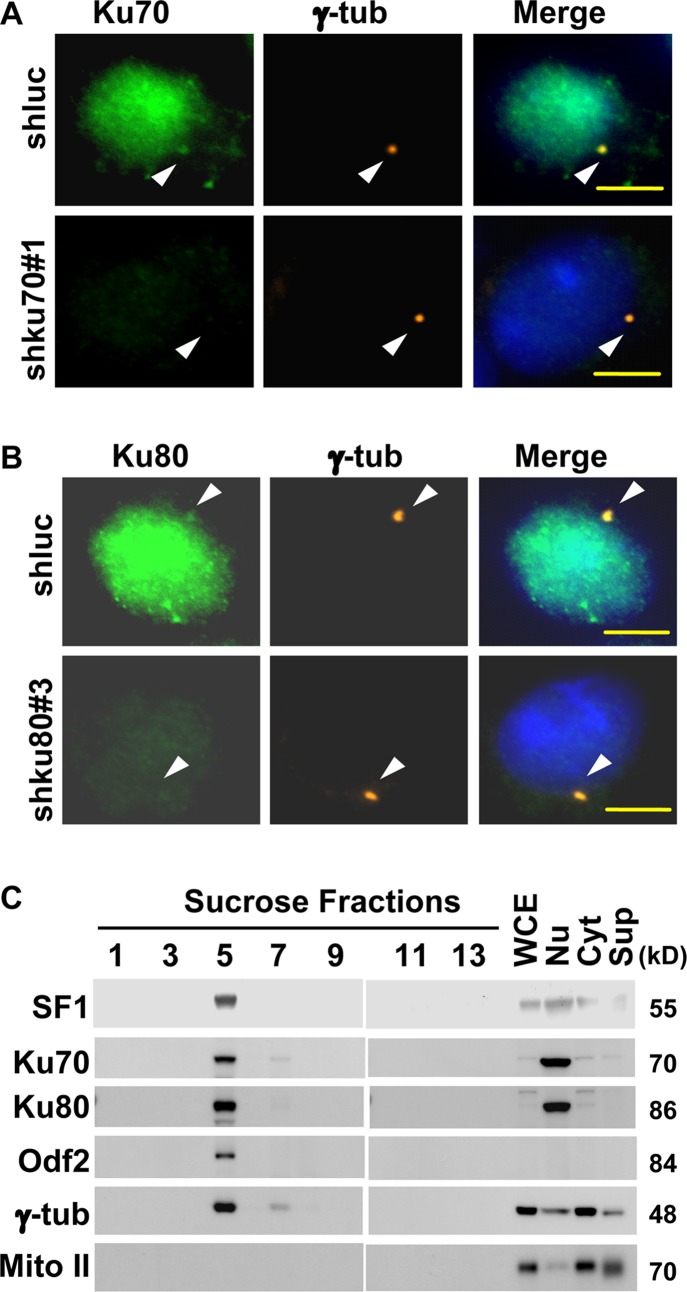

The subcellular localization of Ku70 and Ku80 was examined by immunofluorescence microscopy. Ku70 (Fig. 4A) and Ku80 (Fig. 4B) were present in the centrosome in addition to the nucleus and the cytoplasm, as shown by their colocalization with γ-tubulin in mouse adrenocortical Y1 cells and by the lack of staining when they were depleted of shku70#1 and shku80#3, respectively (Fig. 4A and B; also see Fig. S4A and B in the supplemental material). In addition, Ku70, Ku80, Odf2, and γ-tubulin were also present in the same centrosomal fraction, sucrose fraction 5 from Y1 (Fig. 4C), further confirming the centrosomal localization of Ku70/80.

Fig 4.

Ku70 and Ku80 are centrosomal proteins. (A and B) Ku70 and Ku80 are located in the centrosome. Double staining of Y1 cells with antibodies against Ku70 (A), Ku80 (B), and γ-tubulin (γ-tub) after Y1 cells were infected with shluc, shku70#1, or shku80#3 lentivirus. Centrosomes are indicated by arrowheads. Scale bars are 5 μm. (C) Cosedimentation of Ku70/Ku80 with γ-tubulin from Y1 cells in sucrose gradient ultracentrifugation. Immunoblots of proteins in fractionated cell extracts are shown. Cyt, cytoplasmic fraction; Nu, nuclear fraction; Sup, postcentrosomal supernatant; WCE, whole-cell extract; γ-tub, γ-tubulin; Mito II, mitochondrial complex II.

SF-1 depletion leads to accumulation and activation of DNA-PKcs in the centrosome.

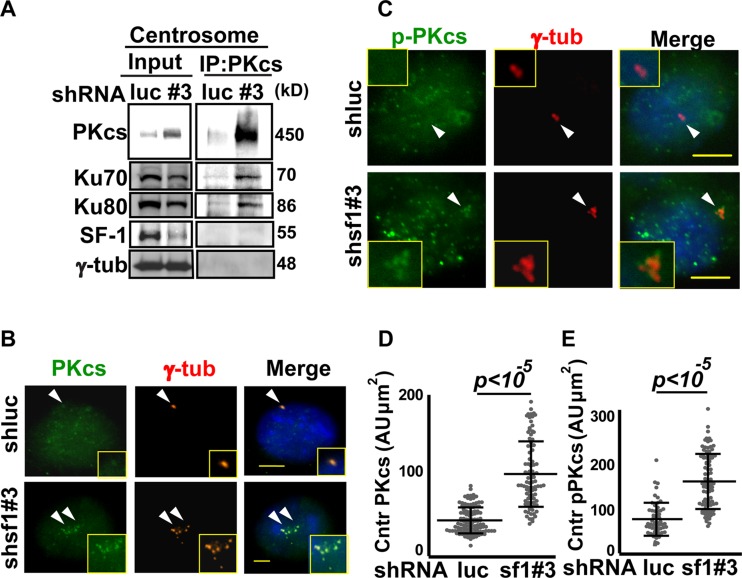

Since SF-1 interacted with Ku70/80 in the centrosome, we checked whether SF-1 is required for centrosomal residency of Ku proteins. Ku70 and Ku80 were present abundantly in the centrosomes of Y1 cells, and their levels were not changed after SF-1 depletion (see Fig. S4C and D in the supplemental material). Ku70/80 heterodimer together with a catalytic subunit (DNA-PKcs) constitute DNA-dependent protein kinase (DNA-PK). We tested whether centrosomal DNA-PKcs is regulated by SF-1. Following SF-1 depletion by shsf1#3, elevated amounts of DNA-PKcs (Fig. 5A; also see Fig. S5A in the supplemental material) and Thr2609-phosphorylated DNA-PKcs (pDNA-PKcs) were detected by immunoblot analysis (see Fig. S5A and E). Immunofluorescence examination followed by quantitation of the signals also showed the increase of DNA-PKcs and Thr2609-phosphorylated DNA-PKcs in the centrosome after SF-1 deletion (Fig. 5B to E). Since Thr2609-phosphorylated DNA-PKcs represents active DNA-PK, these data indicate that SF-1 depletion results in accumulation and activation of DNA-PKcs in the centrosome of Y1 cells. Centrosomal Ku70 and Ku80 were also pulled down by DNA-PKcs following SF-1 depletion by shsf1#3 (Fig. 5A). This result indicates that SF-1 depletion results in accumulation and activation of DNA-PKcs at the centrosome.

Fig 5.

SF-1 depletion results in accumulation of phospho-DNA-PKcs in the centrosome. (A) DNA-PKcs interaction with Ku70/Ku80 in the centrosome following SF-1 depletion. Immunoblot analysis of centrosomal extracts of Y1 cells expressing shRNA against shluc (luc) or shsf1#3 (#3) before (Input) or after immunoprecipitation (IP) with anti-DNA-PKcs (PKcs) antibody. The antibodies used for immunoblot analysis are listed at the left of the gels. γ-tub, γ-tubulin. (B to E) DNA-PKcs and its phosphorylated form are increased in the centrosome following SF-1 depletion. Immunofluorescence staining of DNA-PKcs (PKcs) (B) or phospho-Thr2609 of DNA-PKcs (pPKcs) (C) and γ-tubulin (γ-tub) in shluc and shsf1#3 Y1 cells. Centrosomes are indicated by arrowheads. Scale bars are 5 μm. Insets are magnifications of centrosomes. Quantifications of centrosomal (Cntr) PKcs (D) or pPKcs (E) intensity revealed by γ-tubulin staining are shown in arbitrary units (AU) divided by the area (μm2) of centrosome. All results are from at least three independent experiments expressed as the means ± SD.

SF-1 depletion leads to activation of centrosomal DNA-PK/Akt signaling and centrosome overduplication.

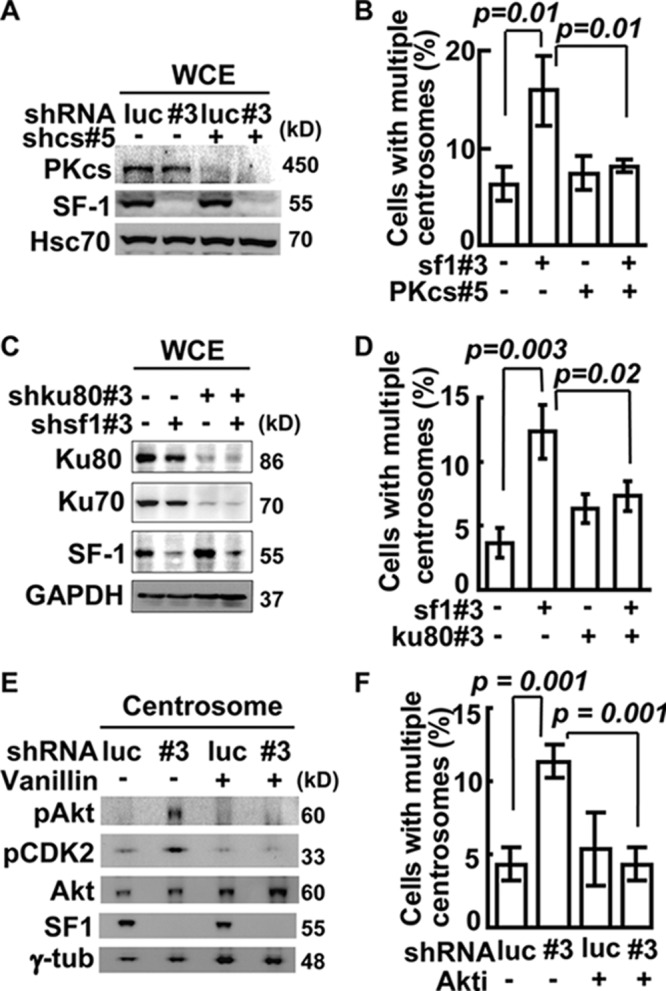

To test the role of DNA-PK in centrosome numbers, we first inhibited its activity with vanillin. Vanillin suppressed centrosome amplification caused by SF-1 depletion in Y1 (see Fig. S5B in the supplemental material) and MA-10 (see Fig. S5C). We also depleted DNA-PKcs specifically by shcs#5 shRNA (Fig. 6A) after screening five different shRNA sequences (see Fig. S5D). DNA-PKcs depletion prevented centrosome overduplication caused by shsf1#3 (Fig. 6B). The effects of Ku70 and Ku80 were also examined by shRNA depletion. Immunoblot assay showed that efficient depletion of Ku80 led to the depletion of Ku70 (Fig. 6C); it also suppressed centrosome amplification in SF-1-deficient Y1 cells (Fig. 6D). These results indicate that all DNA-PK subunits, including Ku70 and Ku80, are involved in centrosome amplification induced by SF-1 depletion. Thus, DNA-PK participates in SF-1-mediated centrosome overduplication.

Fig 6.

Centrosome overduplication induced by SF-1 depletion depends on DNA-PK/Akt signaling. (A) Efficient depletion of DNA-PKcs and SF-1 by shRNA. Whole-cell extracts (WCE) from shluc (luc)-, shsf1#3 (#3)-, and/or DNA-PKcs#5 (shcs#5)-infected Y1 cells were analyzed by immunoblotting. (B) Quantification of population of cells with multiple centrosomes in Y1 cells after depletion of SF-1 with shsf1#3 and/or DNA-PKcs with shcs#5. (C) Efficient depletion of Ku70/80 and SF-1 by shRNA. Whole-cell extracts (WCE) from Y1 cells depleted of SF-1 by shsf1#3 and/or Ku80 by shku80#3 were analyzed by immunoblotting. (D) Requirement of Ku for centrosome overduplication induced by SF-1 depletion. Quantification of populations of cells with multiple centrosomes in shsf1#3- and/or shku80#3-infected Y1 cells is shown. (E) Activation of centrosomal Akt upon SF-1 depletion depends on DNA-PK. Centrosome extracts from shluc (luc)- or shsf1#3 (#3)-infected Y1 cells in the presence or absence of vanillin were analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-phospho-Thr308 of Akt (pAkt), anti-phospho-Thr160 of CDK2 (pCDK2), anti-Akt, and anti-γ-tubulin (γ-tub) antibodies. (F) Centrosome overduplication caused by SF-1 depletion depends on Akt. Quantification of Y1 cells with multiple centrosomes after shluc (luc) or shsf1#3 (#3) lentivirus infection with or without Akt inhibitor (Akti) is shown. Quantification of populations of cells with amplified centrosomes in shluc (luc) or shsf1#3 (#3) lentivirus-infected Y1 cells are expressed as means ± SD from three independent experiments; more than 300 cells were measured in each group.

To investigate the downstream effector that mediates DNA-PK function in centrosome homeostasis, we examined Akt (PKB), because its activity can be activated by DNA-PK in response to DNA damage (18) and its activation can induce centrosome amplification (25). Following SF-1 depletion, in the centrosome Thr308-phosphorylated Akt (pAkt) and pCDK2 were increased (Fig. 6E; also see Fig. S5A and E in the supplemental material), but p53 was not phosphorylated (see Fig. S5E). The increased phosphorylation of these proteins was blocked by DNA-PKcs depletion (see Fig. S5E) or by the DNA-PK inhibitor vanillin (Fig. 6E), further indicating the importance of DNA-PK in triggering Akt and CDK2 activation. The global levels of DNA-PKcs (Fig. 6A), Akt, and pAkt (see Fig. S5F) in the whole-cell lysate, however, were not changed following SF-1 depletion. This indicates that the DNA-PK/Akt signaling cascade occurs only in the centrosome, consistent with our data that only centrosomal DNA-PK was activated in response to SF-1 depletion.

The effect of Akt was further checked by treating Y1 cells with Akt inhibitor (Akti). It resulted in a reduction of cells with multiple centrosomes caused by shsf1#3 (Fig. 6F). Thus, centrosomal Akt participates in centrosome overduplication induced by SF-1 depletion.

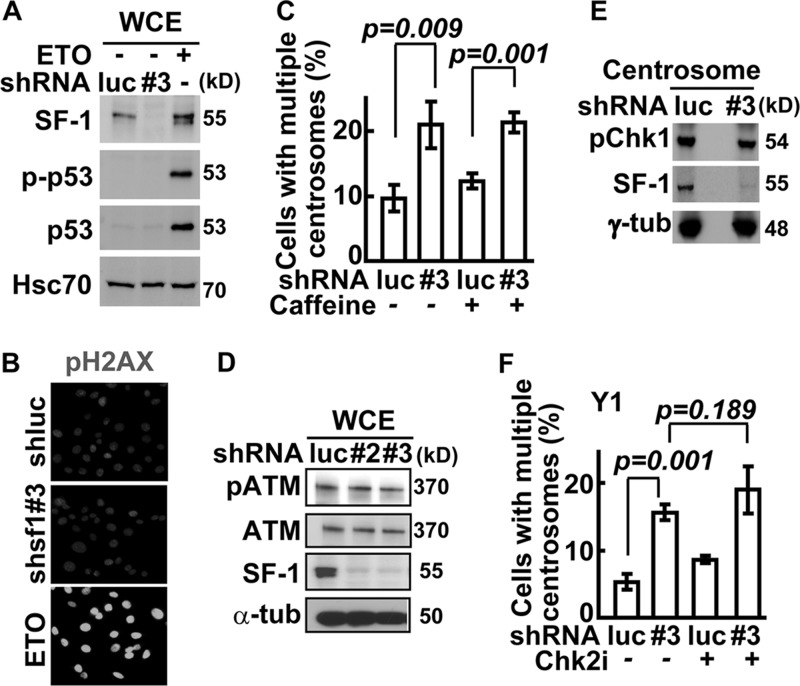

SF-1 depletion does not activate DNA damage response.

DNA-PK is usually activated in response to DNA damage, so we tested whether the activation of DNA-PK caused by SF-1 depletion was the result of DNA damage. The key indicators of DNA damage are the phosphorylation and stabilization of p53 (26) and phosphorylation of H2AX (27). SF-1 depletion from Y1 (Fig. 7A) or MA-10 (see Fig. S6A in the supplemental material) cells did not trigger accumulation of p53, Ser15-phosphorylated p53 (p-p53), or H2AX phosphorylation at Ser139 (Fig. 7B; also see Fig. S6B), all of which were induced by etoposide. The DNA damage response induced by etoposide also did not affect SF-1 amounts and its subcellular localization (see Fig. S6C). These data indicate that DNA-PK activation caused by SF-1 deficiency in Y1 and MA-10 cells does not involve DNA damage.

Fig 7.

SF-1 depletion does not activate nuclear DNA damage response. (A) SF-1 depletion does not activate p53. Whole-cell extracts (WCE) from Y1 cells infected with shluc (luc) or shsf1#3 (#3) lentivirus or treated with etoposide (ETO) were analyzed by immunoblotting. (B) SF-1 depletion does not induce nuclear DNA damage response. shluc or shsf1#3 lentivirus-infected or etoposide (ETO)-treated Y1 cells were costained with DNA dye (DAPI) and antibody against phospho-Ser139 of H2AX (pH2AX). (C) Effect of caffeine on centrosome numbers. Quantification of populations of cells with multiple centrosomes in shluc or shsf1#3 lentivirus-infected Y1 cells in the presence or absence of caffeine is shown. (D) ATM is not affected by SF-1 depletion. Whole-cell extracts (WCE) from Y1 cells infected with shluc (luc), shsf1#2 (#2), or shsf1#3 (#3) lentivirus were analyzed by immunoblotting with antibodies against SF-1, phospho-Ser1981 of ATM (pATM), ATM, or α-tubulin (α-tub). (E) Centrosomal Chk1 is not affected by SF-1 depletion. Centrosome extracts of shluc (luc) or shsf1#3 (#3) lentivirus-infected Y1 were analyzed by immunoblot assay with antibodies against phospho-Ser345 of Chk1 (pChk1), SF-1, and γ-tubulin (γ-tub). (F) Chk2 inhibitor does not affect centrosome overduplication in SF-1-deficient Y1 cells. Quantification of populations of cells with multiple centrosomes in shluc (luc) or shsf1#3 (#3) lentivirus-infected Y1 cells in the presence or absence of Chk2 inhibitor II (Chk2i) is shown. All results are expressed as the means ± SD from at least three independent experiments; more than 300 cells were counted in each group.

In addition to DNA-PK, the involvement of ATM and ATR in centrosome overduplication was also examined. Neither ATM/ATR inhibitor caffeine nor the ATM-specific inhibitor KU-55933 (ATMi) interfered with centrosome overduplication induced by SF-1 depletion (Fig. 7C; also see Fig. S6D in the supplemental material). The level of ATM and its phosphorylation also were not changed following SF-1 depletion by shsf1#2 or shsf1#3 (Fig. 7D). The phosphorylation of ATR substrate, Chk1, was not changed in the centrosome (Fig. 7E). Also, Chk2 inhibitor II (Chk2i) did not interfere with centrosome overduplication induced by SF-1 depletion (Fig. 7F). These data suggest that, unlike DNA-PK, ATM/ATR and Chk1/2 probably do not participate in centrosome overduplication induced by SF-1 depletion.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we have delineated the mechanism by which nuclear receptor SF-1 prevents centrosome overduplication. We found that SF-1 sequestered Ku70 and Ku80 from DNA-PKcs in the centrosome. SF-1 depletion resulted in centrosomal recruitment and activation of DNA-PKcs, which in turn activated Akt and CDK2 in a signaling cascade, leading to centrosome overduplication. Our results thus provide a novel mechanism by which centrosome homeostasis is regulated by centrosomal DNA-PK.

Centrosomal SF-1 prevents centrosome overduplication.

SF-1 is a transcription factor that controls sexual differentiation and development of adrenocortical and gonadal cells (2). Although the functions of SF-1 in transcription have been well characterized, the mechanism by which SF-1 participates in cell growth control remains largely unknown. Our earlier results show that SF-1 resides in the centrosome and controls centrosomal homeostasis (5). Here, we show that centrosomal SF-1 prevents centrosome overduplication by restricting the activities of DNA-PK/Akt signaling within the centrosome; this can be one of the means by which SF-1 controls the growth and survival of adrenocortical progenitor cells.

In this study, we demonstrate that centrosome homeostasis is controlled by SF-1 in steroidogenic cells. SF-1 functions as a guardian to prevent centrosome overduplication under stressed conditions. However, its overexpression does not block centrosome duplication; rather, it inhibits centrosome overduplication induced by hydroxyurea. Therefore, SF-1 does not control normal centrosome duplication, it prevents abnormal centrosome overduplication. Many centrosomal proteins, such as Dido (28) and Cep76 (29), also prevent centrosome overduplication without regulating normal centrosome duplication. The role of SF-1 in the centrosome is similar to that of Dido and Cep76, which keep centrosome copy numbers in check.

SF-1 prevents centrosome overduplication without affecting centriole biogenesis. The level of PLK4 was not affected following SF-1 depletion. The centrosome phenotype that we observed also differs from those found in cells defective in centriole biogenesis machinery, SAS-4, SAS-5, and SAS-6 (30 –32). Thus, centrosome overduplication induced by SF-1 depletion is not due to the problem in centriole assembly; rather, it is due to a defect in the control of centrosome duplication because the levels of CDK2/cyclin A were increased.

We show here that the phosphorylation and accumulation of CDK2 in the centrosome depends on DNA-PK activation. The mechanism of CDK2 phosphorylation after DNA-PK/Akt activation is still unclear. CDK2 is activated by Akt in endothelial cells of the developing blood vessel upon stimulation by vascular endothelial growth factor, and this CDK2 activity leads to centrosome amplification (33). Thus, the activation of CDK2 by Akt signaling and the subsequent centrosome overduplication may also occur in other types of cells, such as adrenal and gonadal cells.

Centrosomal DNA-PK controls centrosome duplication in the absence of DNA damage.

DNA damage and centrosome amplification are two distinct but closely coordinated events (34, 35). When cells incur DNA damage, ATM, ATR, and DNA-PK are activated to arrest cell cycles for damage repair and cell survival (16, 18). ATM and ATR also trigger centrosome amplification to eliminate cells deficient in DNA repair (34, 35). Here, we demonstrate that elevated activity of centrosomal DNA-PK can also lead to centrosome amplification. Thus, DNA-PK joins ATM and ATR in regulating both DNA damage repair and centrosome duplication.

Although the nuclear DNA-PK is activated by DNA damage, here we show that DNA-PK activation in the centrosome is independent of DNA damage and is regulated by centrosomal SF-1 in Y1 and MA10 cells. Following SF-1 depletion, DNA-PKcs is recruited to the centrosome, forming a complex with Ku, and activated. Our report is not the only case of DNA-PK activation without DNA damage. Centrosomal DNA-PK is also activated during mitosis under both stressed and unstressed conditions (36, 37). Thus, the activation of DNA-PK in the centrosome does not appear to require DNA breaks.

DNA-PK/Akt signaling was activated in the centrosome upon SF-1 depletion, whereas the nuclear DNA damage response was not activated. The activation of DNA-PK/Akt signaling in different subcellular compartments appears to affect cells in opposite directions. In the nucleus, the activation of DNA-PK/Akt signaling promotes cell survival (18). Here, we show that the activation of centrosomal DNA-PK/Akt signaling results in centrosome overduplication, which usually leads to mitotic defects (5). Thus, the subcellular site of DNA-PK/Akt signaling appears to be important for the outcome. In the nucleus, this activation leads to survival, while in the centrosome this activation leads to genomic instability.

DNA-PK is activated in the centrosome during mitosis, and this activity is required for normal progression of mitosis (36, 37). During interphase, DNA-PK should not be activated in the centrosome. Here, we show that aberrant activation of centrosomal DNA-PK during interphase induces centrosome overduplication. Thus, centrosomal DNA-PK activity has to be tightly regulated at all stages of the cell cycle to maintain genomic integrity.

We show that SF-1 prevents aberrant activation of DNA-PK during interphase in steroidogenic cells. In nonsteroidogenic cells that do not express SF-1, the activity of centrosomal DNA-PK during interphase should be modulated by other factors. We speculate that unknown factors sequester centrosomal Ku70/Ku80. Once these regulatory factors are removed, DNA-PKcs would be recruited to the centrosome and activated. It will be interesting to find out what regulates centrosomal DNA-PK activity in those cells that do not express SF-1.

In summary, we have demonstrated that centrosomal SF-1 is involved in the control of centrosome homeostasis by interacting with centrosomal DNA-PK subunits Ku70/80 and regulating DNA-PK/Akt signaling. Our results thus reveal a novel function of DNA-PK/Akt signaling in centrosome cycle control and provide a mechanism by which centrosomal DNA-PK controls centrosome homeostasis.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Cheng-Hsilin Hsieh for technical assistance in mass spectrometry, Tang K. Tang for the anti-CPAP and anti-SAS6 antibodies, and Chung Wang for the anti-Hsc70 antibodies. RNAi reagents were obtained from the National RNAi Core Facility located at the Institute of Molecular Biology/Genomic Research Center, Academia Sinica, supported by the National Research Program for Genomic Medicine, NSC 97-3112-B-001-016.

This work was supported by grants from Academia Sinica and the National Science Council, Taiwan (NSC100-2321-B-001-006).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 19 November 2012

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/MCB01064-12.

REFERENCES

- 1. Parker KL, Schimmer BP. 1997. Steroidogenic factor 1: a key determinant of endocrine development and function. Endocr. Rev. 18: 361–377 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Val P, Lefrancois-Martinez AM, Veyssiere G, Martinez A. 2003. SF-1 a key player in the development and differentiation of steroidogenic tissues. Nucl. Recept. 1: 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Luo X, Ikeda Y, Parker KL. 1994. A cell-specific nuclear receptor is essential for adrenal and gonadal development and sexual differentiation. Cell 77: 481–490 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Doghman M, Karpova T, Rodrigues GA, Arhatte M, De Moura J, Cavalli LR, Virolle V, Barbry P, Zambetti GP, Figueiredo BC, Heckert LL, Lalli E. 2007. Increased steroidogenic factor-1 dosage triggers adrenocortical cell proliferation and cancer. Mol. Endocrinol. 21: 2968–2987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lai PY, Wang CY, Chen WY, Kao YH, Tsai HM, Tachibana T, Chang WC, Chung BC. 2011. Steroidogenic factor 1 (NR5A1) resides in centrosomes and maintains genomic stability by controlling centrosome homeostasis. Cell Death Differ. 18: 1836–1844 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Fukasawa K. 2005. Centrosome amplification, chromosome instability and cancer development. Cancer Lett. 230: 6–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hinchcliffe EH, Sluder G. 2001. “It takes two to tango”: understanding how centrosome duplication is regulated throughout the cell cycle. Genes Dev. 15: 1167–1181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ganem NJ, Godinho SA, Pellman D. 2009. A mechanism linking extra centrosomes to chromosomal instability. Nature 460: 278–282 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Pihan GA, Purohit A, Wallace J, Knecht H, Woda B, Quesenberry P, Doxsey SJ. 1998. Centrosome defects and genetic instability in malignant tumors. Cancer Res. 58: 3974–3985 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Meraldi P, Lukas J, Fry AM, Bartek J, Nigg EA. 1999. Centrosome duplication in mammalian somatic cells requires E2F and Cdk2-cyclin A. Nat. Cell Biol. 1: 88–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Chen Z, Indjeian VB, McManus M, Wang L, Dynlacht BD. 2002. CP110, a cell cycle-dependent CDK substrate, regulates centrosome duplication in human cells. Dev. Cell 3: 339–350 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kasbek C, Yang CH, Yusof AM, Chapman HM, Winey M, Fisk HA. 2007. Preventing the degradation of mps1 at centrosomes is sufficient to cause centrosome reduplication in human cells. Mol. Biol. Cell 18: 4457–4469 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Okuda M, Horn HF, Tarapore P, Tokuyama Y, Smulian AG, Chan PK, Knudsen ES, Hofmann IA, Snyder JD, Bove KE, Fukasawa K. 2000. Nucleophosmin/B23 is a target of CDK2/cyclin E in centrosome duplication. Cell 103: 127–140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Bourke E, Brown JA, Takeda S, Hochegger H, Morrison CG. 2010. DNA damage induces Chk1-dependent threonine-160 phosphorylation and activation of Cdk2. Oncogene 29: 616–624 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Dodson H, Bourke E, Jeffers LJ, Vagnarelli P, Sonoda E, Takeda S, Earnshaw WC, Merdes A, Morrison C. 2004. Centrosome amplification induced by DNA damage occurs during a prolonged G2 phase and involves ATM. EMBO J. 23: 3864–3873 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ciccia A, Elledge SJ. 2010. The DNA damage response: making it safe to play with knives. Mol. Cell 40: 179–204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Collis SJ, DeWeese TL, Jeggo PA, Parker AR. 2005. The life and death of DNA-PK. Oncogene 24: 949–961 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Bozulic L, Surucu B, Hynx D, Hemmings BA. 2008. PKBalpha/Akt1 acts downstream of DNA-PK in the DNA double-strand break response and promotes survival. Mol. Cell 30: 203–213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Zhang S, Hemmerich P, Grosse F. 2007. Centrosomal localization of DNA damage checkpoint proteins. J. Cell. Biochem. 101: 451–465 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Chen WY, Juan LJ, Chung BC. 2005. SF-1 (nuclear receptor 5A1) activity is activated by cyclic AMP via p300-mediated recruitment to active foci, acetylation, and increased DNA binding. Mol. Cell. Biol. 25: 10442–10453 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Bornens M, Paintrand M, Berges J, Marty MC, Karsenti E. 1987. Structural and chemical characterization of isolated centrosomes. Cell Motil. Cytoskeleton 8: 238–249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Bahmanyar S, Kaplan DD, Deluca JG, Giddings TH, Jr, O'Toole ET, Winey M, Salmon ED, Casey PJ, Nelson WJ, Barth AI. 2008. Beta-catenin is a Nek2 substrate involved in centrosome separation. Genes Dev. 22: 91–105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Chen WY, Lee WC, Hsu NC, Huang F, Chung BC. 2004. SUMO modification of repression domains modulates function of nuclear receptor 5A1 (steroidogenic factor-1). J. Biol. Chem. 279: 38730–38735 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Habedanck R, Stierhof YD, Wilkinson CJ, Nigg EA. 2005. The Polo kinase Plk4 functions in centriole duplication. Nat. Cell Biol. 7: 1140–1146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Nam HJ, Chae S, Jang SH, Cho H, Lee JH. 2010. The PI3K-Akt mediates oncogenic Met-induced centrosome amplification and chromosome instability. Carcinogenesis 31: 1531–1540 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Banin S, Moyal L, Shieh S, Taya Y, Anderson CW, Chessa L, Smorodinsky NI, Prives C, Reiss Y, Shiloh Y, Ziv Y. 1998. Enhanced phosphorylation of p53 by ATM in response to DNA damage. Science 281: 1674–1677 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Paull TT, Rogakou EP, Yamazaki V, Kirchgessner CU, Gellert M, Bonner WM. 2000. A critical role for histone H2AX in recruitment of repair factors to nuclear foci after DNA damage. Curr. Biol. 10: 886–895 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Trachana V, van Wely KH, Guerrero AA, Futterer A, Martinez AC. 2007. Dido disruption leads to centrosome amplification and mitotic checkpoint defects compromising chromosome stability. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 104: 2691–2696 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Tsang WY, Spektor A, Vijayakumar S, Bista BR, Li J, Sanchez I, Duensing S, Dynlacht BD. 2009. Cep76, a centrosomal protein that specifically restrains centriole reduplication. Dev. Cell 16: 649–660 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Bettencourt-Dias M, Glover DM. 2007. Centrosome biogenesis and function: centrosomics brings new understanding. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 8: 451–463 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Stevens NR, Roque H, Raff JW. 2010. DSas-6 and Ana2 coassemble into tubules to promote centriole duplication and engagement. Dev. Cell 19: 913–919 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Tang CJ, Fu RH, Wu KS, Hsu WB, Tang TK. 2009. CPAP is a cell-cycle regulated protein that controls centriole length. Nat. Cell Biol. 11: 825–831 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Taylor SM, Nevis KR, Park HL, Rogers GC, Rogers SL, Cook JG, Bautch VL. 2010. Angiogenic factor signaling regulates centrosome duplication in endothelial cells of developing blood vessels. Blood 116: 3108–3117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Bourke E, Dodson H, Merdes A, Cuffe L, Zachos G, Walker M, Gillespie D, Morrison CG. 2007. DNA damage induces Chk1-dependent centrosome amplification. EMBO Rep. 8: 603–609 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Shimada M, Komatsu K. 2009. Emerging connection between centrosome and DNA repair machinery. J. Radiat. Res. (Tokyo) 50: 295–301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Lee KJ, Lin YF, Chou HY, Yajima H, Fattah KR, Lee SC, Chen BP. 2011. Involvement of DNA-dependent protein kinase in normal cell cycle progression through mitosis. J. Biol. Chem. 286: 12796–12802 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Shang ZF, Huang B, Xu QZ, Zhang SM, Fan R, Liu XD, Wang Y, Zhou PK. 2010. Inactivation of DNA-dependent protein kinase leads to spindle disruption and mitotic catastrophe with attenuated checkpoint protein 2 phosphorylation in response to DNA damage. Cancer Res. 70: 3657–3666 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.