Glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) and GLP-2 are peptide hormones encoded by the proglucagon gene that are cosecreted in equimolar amounts from enteroendocrine L-cells of the intestine in response to nutrients, primarily carbohydrates and fats (1). Most is known about GLP-1, which stimulates the pancreatic secretion of insulin in a glucose-dependent manner while inhibiting the secretion of glucagon, gastric emptying, and satiety. This tonic effect maintains glucose homeostasis and is chiefly controlled by the enzymatic degradation of the peptide in the circulation by dipeptidyl peptidase-4 (DPP-4) (2). This has led to the development of new therapies for diabetes, including GLP-1 receptor analogs and inhibitors of DPP-4 (3).

By contrast to GLP-1, the physiological and therapeutic roles of GLP-2 are less clear. GLP-2 inhibits postprandial gastric motility/secretion and intestinal hexose transport and has a trophic effect on intestinal epithelium that implies a specific role in intestinal repair processes (4). GLP-2 may antagonize the effects of GLP-1 on glucose homeostasis by enhancing the pancreatic release of glucagon but could also have a cooperative, short-term effect on satiety. Its biological actions are mediated by a specific G-protein–coupled receptor.

Recent studies have also suggested that GLP-1 and possibly GLP-2 may be involved in regulating fat absorption and chylomicron biogenesis (5–8), pointing to a regulatory role in postprandial lipid metabolism. This has implications for atherogenesis and vascular disease in diabetes and insulin-resistant states. GLP-1 may improve while GLP-2 may aggravate postprandial lipemia, but exactly how these biological actions are intertwined in health and disease remains unclear.

In this issue of Diabetes, Adeli and colleagues (9) report a well-designed set of experiments investigating the time-dependent effects of GLP-1, GLP-2, and the coinfusions of both gut peptides on postprandial chylomicron metabolism in chow-fed and fructose-fed male Syrian golden hamsters. An olive oil load was administered via oral gavage and intravenous dosing regimens were used that achieved physiological concentrations of the peptides. Poloxamer was administered to protect newly formed chylomicrons from catabolism and enable estimation of their secretion. The short-term (30 min) intravenous infusion of GLP-1 reduced whereas GLP-2 increased postprandial apolipoprotein (apo) B48 and triglyceride concentrations and chylomicron particle secretion in the chow-fed hamsters. The acute coinfusion of both peptides resulted in a net increase in these indices of postprandial lipemia, but this was reversed to a dominant effect of GLP-1 in experiments that sampled over 2 and 6 h and after administration of a DPP-4 inhibitor. With the more prolonged infusions, GLP-1 had a dominant effect over GLP-2 in decreasing chylomicron particle secretion. The acute inhibitory effects of GLP-1 on chylomicron secretion were augmented by including glucose in the oral fat load. In the fructose-fed hamsters, postprandial lipemia was enhanced compared with the chow model, with a more pronounced response to GLP-2 and impaired response to GLP-1.

How valid are these studies? The Syrian golden hamster is an accepted model for studying glucose and lipid metabolism because the fructose-fed state reflects diet-induced insulin resistance and dyslipidemia (10); however, only male animals were studied. The experiments were designed to simulate the acute and prolonged physiological responses of the GLPs to a fat load. However, the oral challenge of fat alone does not represent a mixed meal, noting that glucose has a major modulating effect on the release of both GLPs and insulin. Measurement of chylomicron particle turnover was based on an indirect method in which particle catabolism was artificially blocked and secretion estimated using noncompartmental analysis. Chylomicron biogenesis integrates a complex series of processes and is most appropriately studied using endogenous labeling with tracers and multicompartmental modeling (11). The effects of the GLPs on the catabolism of postprandial chylomicrons cannot be strictly excluded in this experimental model.

The findings are physiologically significant, however. After initial luminal hydrolysis of dietary triglycerides, chylomicron biogenesis by the enterocyte involves the reesterification of fatty acids and sn-2-monoacylglycerol by diglyceride acyltransferase followed by stepwise lipidation of apoB48 by microsomal triglyceride transfer protein to form the mature chylomicron particle (12). Under physiological conditions, insulin partially inhibits these processes by reducing lipogenesis in the enterocyte, enhancing degradation of intracellular apoB48, and decreasing the expression of microsomal triglyceride transfer protein (13,14). GLP-1 augments these effects via its incretin response, but GLP-2 appears to antagonize them by increasing lipid absorption via CD36/fatty acid translocase (7). The current study proffers a temporal dimension to these events: release of GLP-1 initially slows chylomicron biogenesis, but its duration of action is curtailed by more rapid catabolism by DPP-4 relative to GLP-2, which in turns facilitates biogenesis over a longer period. The physiological coordination of these actions may be most relevant to the so called “ileal brake” phenomenon (15), whereby GLP-1 increases the delivery of fat to the ileum thereby activating a satiety signal and GLP-2 acts to complete the absorption of fat in the proximal intestine. Whether increased absorption of fat by GLP-2 also mediates satiety remains unclear. Insulin modulates the impact of GLPs on chylomicron secretion but critically also accelerates the turnover of chylomicron particles by stimulating their catabolism by lipoprotein lipase and hepatic receptors (12,16). The relative effects of GLP-1 and GLP-2 on gastric emptying, intestinal motility, and lymphatic and splanchnic blood flow as well VLDL and apoC3 metabolism and their consequence for postprandial chylomicron metabolism remain to be investigated.

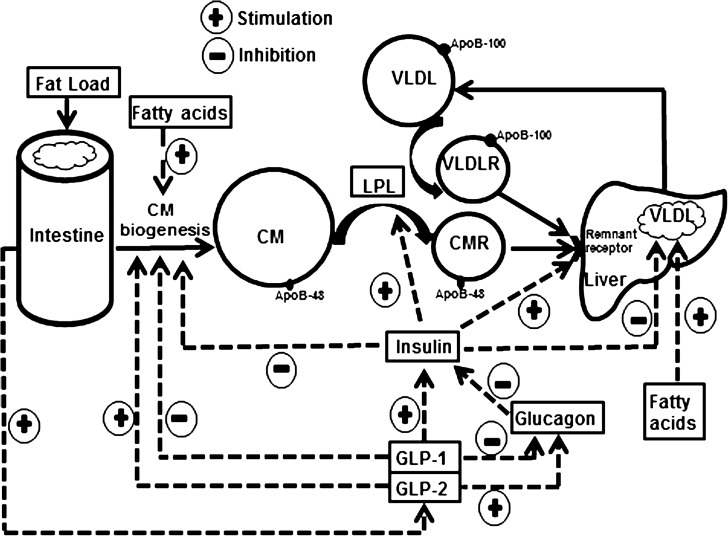

The pathophysiological significance of this study relates to the mechanism of increased production of chylomicrons in insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes (12,16,17). The roles of impaired insulin signaling, inflammation, increased availability of fatty acids, and enhanced lipogenesis in accelerating chylomicron secretion by enterocytes have been well emphasized. Enterocytic resistance to the direct effects of GLP-1, as well as increased sensitivity to GLP-2, may augment postprandial lipemia in insulin resistance by increasing chylomicron biogenesis. Figure 1 summarizes the potential role of GLP-1, GLP-2, insulin, and glucagon in regulating the postprandial metabolism of chylomicron and VLDL particles (FIG. 1).

FIG. 1.

Potential role of GLP-1, GLP-2, insulin, and glucagon in regulating the postprandial metabolism of chylomicron and VLDL particles. GLP-1 and GLP-2 have opposing effects on chylomicron metabolism in response to dietary fat load. GLP-1 inhibits intestinal chylomicron biogenesis, stimulates insulin secretion, and suppresses glucagon secretion, whereas GLP-2 stimulates chylomicron biogenesis and glucagon secretion. Under normal physiological conditions, insulin inhibits chylomicron and VLDL synthesis and secretion but stimulates lipoprotein lipase LPL and hepatic receptor activities, thereby enhancing the removal of chylomicron and VLDL remnant particles by liver. Postprandial dyslipidemia in type 2 diabetes may result from an imbalance in the secretion and catabolism of GLP-1 and GLP-2, together with the effect of insulin resistance and increased availability of fatty acids to enterocyte and hepatocyte. CM, chylomicron; CMR: chylomicron remnant; LPL, lipoprotein lipase; VLDLR, very-low-density lipoprotein remnant.

These findings also further explain the mechanism of action of DPP-4 inhibitors in improving dyslipidemia by sustaining the action of GLP-1 relative to GLP-2 (3). Whether specific inhibition of GLP-2 can mitigate postprandial dyslipidemia remains untested. Activation of GLP-2 may conversely be useful in treating injury or dysfunction of intestinal mucosal epithelium, including ischemic damage and short bowel syndromes (18). Specific regulation of GLP-mediated mechanisms may have less potential for managing of diabetic dyslipidemia than improvement in glycemic control with more rigorous lifestyle interventions and use of statins and triglyceride regulating agents, including fibrates, n-3 fatty acids, and niacin (19).

Beyond beneficial effects atherogenic dyslipidemia, GLP-1 may directly mitigate the risk of vascular disease in diabetes by improving endothelial function and blood pressure and decreasing inflammation (20). Whether GLP-2 augments or antagonizes these effects also warrants further investigation.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

No potential conflicts of interest relevant to this article were reported.

Footnotes

See accompanying original article, p. 373.

REFERENCES

- 1.Drucker DJ. Minireview: the glucagon-like peptides. Endocrinology 2001;142:521–527 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mentlein R, Gallwitz B, Schmidt WE. Dipeptidyl-peptidase IV hydrolyses gastric inhibitory polypeptide, glucagon-like peptide-1(7-36)amide, peptide histidine methionine and is responsible for their degradation in human serum. Eur J Biochem 1993;214:829–835 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Farr S, Adeli K. Incretin-based therapies for treatment of postprandial dyslipidemia in insulin-resistant states. Curr Opin Lipidol 2012;23:56–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Drucker DJ. Glucagon-like peptide 2. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2001;86:1759–1764 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hsieh J, Longuet C, Baker CL, et al. The glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor is essential for postprandial lipoprotein synthesis and secretion in hamsters and mice. Diabetologia 2010;53:552–561 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Qin X, Shen H, Liu M, et al. GLP-1 reduces intestinal lymph flow, triglyceride absorption, and apolipoprotein production in rats. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 2005;288:G943–G949 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hsieh J, Longuet C, Maida A, et al. Glucagon-like peptide-2 increases intestinal lipid absorption and chylomicron production via CD36. Gastroenterology 2009;137:997–1005, 1005, e1–e4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Meier JJ, Nauck MA, Pott A, et al. Glucagon-like peptide 2 stimulates glucagon secretion, enhances lipid absorption, and inhibits gastric acid secretion in humans. Gastroenterology 2006;130:44–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hein GJ, Baker C, Hsieh J, Farr S, Adeli K. GLP-1 and GLP-2 as yin and yang of intestinal lipoprotein production: evidence for predominance of GLP-2–stimulated postprandial lipemia in normal and insulin-resistant states. Diabetes 2013;62:373–381 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Federico LM, Naples M, Taylor D, Adeli K. Intestinal insulin resistance and aberrant production of apolipoprotein B48 lipoproteins in an animal model of insulin resistance and metabolic dyslipidemia: evidence for activation of protein tyrosine phosphatase-1B, extracellular signal-related kinase, and sterol regulatory element-binding protein-1c in the fructose-fed hamster intestine. Diabetes 2006;55:1316–1326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Barrett PHR, Chan DC, Watts GF. Thematic review series: patient-oriented research. Design and analysis of lipoprotein tracer kinetics studies in humans. J Lipid Res 2006;47:1607–1619 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Xiao C, Hsieh J, Adeli K, Lewis GF. Gut-liver interaction in triglyceride-rich lipoprotein metabolism. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 2011;301:E429–E446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Levy E, Sinnett D, Thibault L, Nguyen TD, Delvin E, Ménard D. Insulin modulation of newly synthesized apolipoproteins B-100 and B-48 in human fetal intestine: gene expression and mRNA editing are not involved. FEBS Lett 1996;393:253–258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Au WS, Kung HF, Lin MC. Regulation of microsomal triglyceride transfer protein gene by insulin in HepG2 cells: roles of MAPKerk and MAPKp38. Diabetes 2003;52:1073–1080 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Maljaars PW, Peters HP, Mela DJ, Masclee AA. Ileal brake: a sensible food target for appetite control. A review. Physiol Behav 2008;95:271–281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pang J, Chan DC, Barrett PHR, Watts GF. Postprandial dyslipidaemia and diabetes: mechanistic and therapeutic aspects. Curr Opin Lipidol 2012;23:303–309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Duez H, Pavlic M, Lewis GF. Mechanism of intestinal lipoprotein overproduction in insulin resistant humans. Atheroscler Suppl 2008;9:33–38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jeppesen PB. Glucagon-like peptide-2: update of the recent clinical trials. Gastroenterology 2006;130(Suppl. 1):S127–S131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Watts GF, Karpe F. Triglycerides and atherogenic dyslipidaemia: extending treatment beyond statins in the high-risk cardiovascular patient. Heart 2011;97:350–356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sivertsen J, Rosenmeier J, Holst JJ, Vilsbøll T. The effect of glucagon-like peptide 1 on cardiovascular risk. Nat Rev Cardiol 2012;9:209–222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]