Abstract

Glucagon and glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) are produced in pancreatic α-cells and enteroendocrine L-cells, respectively, in a tissue-specific manner from the same precursor, proglucagon, that is encoded by glucagon gene (Gcg), and play critical roles in glucose homeostasis. Here, we studied glucose homeostasis and β-cell function of Gcg-deficient mice that are homozygous for a Gcg-GFP knock-in allele (Gcggfp/gfp). The Gcggfp/gfp mice displayed improved glucose tolerance and enhanced insulin secretion, as assessed by both oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) and intraperitoneal glucose tolerance test (IPGTT). Responses of glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP) to both oral and intraperitoneal glucose loads were unexpectedly enhanced in Gcggfp/gfp mice, and immunohistochemistry localized GIP to pancreatic β-cells of Gcggfp/gfp mice. Furthermore, secretion of GIP in response to glucose was detected in isolated islets of Gcggfp/gfp mice. Blockade of GIP action in vitro and in vivo by cAMP antagonism and genetic deletion of the GIP receptor, respectively, almost completely abrogated enhanced insulin secretion in Gcggfp/gfp mice. These results indicate that ectopic GIP expression in β-cells maintains insulin secretion in the absence of proglucagon-derived peptides (PGDPs), revealing a novel compensatory mechanism for sustaining incretin hormone action in islets.

The glucagon gene encodes proglucagon, a precursor of multiple peptides including glucagon, GLP-1, oxyntomodulin, and GLP-2 (1,2). Glucagon is produced in pancreatic α-cells, whereas GLPs are found in intestinal L-cells (1,2). Glucagon has been recognized as a major counteracting hormone to insulin in regulating glucose homeostasis (3,4). The main action of glucagon is to stimulate hepatic glucose production by promoting gluconeogenesis and glycogenolysis while inhibiting glycogen synthesis and glycolysis in response to hypoglycemia (4,5). Dysregulation of glucagon secretion contributes to the pathophysiology of diabetes mellitus through increased hepatic glucose production (6,7). Furthermore, experimental suppression of hyperglucagonemia corrects postprandial hyperglycemia in individuals with type 2 diabetes (7). Therefore, inhibition of glucagon action represents one potential approach to the treatment of type 2 diabetes (4,8).

The importance of glucagon in regulating glucose homeostasis has been demonstrated by using genetically modified mouse models and by pharmacological interventions that suppress glucagon signaling (9–15). In such models, suppression of glucagon signaling increases circulating levels not only of glucagon but also of GLP-1. The increased GLP-1 levels, in turn, contribute to improved function of pancreatic β-cells. Mice with targeted deletion of the glucagon receptor gene (Gcgr−/−) exhibit increased plasma GLP-1 levels, enhanced insulin secretion in vivo, and resistance to streptozotocin-induced destruction of pancreatic β-cells (14,16). It also has been demonstrated that treatment with Gcgr antisense oligonucleotides improves glucose tolerance and increases circulating levels of active GLP-1 in rodent diabetic models (13). In addition, treatment with Gcgr antisense oligonucleotides increases both GLP-1 and the insulin content of islets in db/db mice (13).

GLP-1 and GIP, which is produced in intestinal K-cells, both have been recognized as incretins (1,17). Both GLP-1 and GIP stimulate insulin secretion and are secreted by intestinal endocrine cells in response to ingestion of nutrients, including carbohydrates, lipids, and proteins. In addition to insulinotropic effects, both GLP-1 and GIP promote β-cell proliferation and inhibit apoptosis (1,18). However, these peptides exert differential effects on glucagon secretion. GLP-1 inhibits the postprandial glucagon response, whereas GIP enhances it in a glucose-dependent manner (1,19,20).

To determine the consequences of loss of glucagon action in the absence of concomitant upregulation of GLP-1 production, we recently established a mouse model in which the entire proglucagon gene is disrupted by insertion of GFP. Both GFP and PGDPs are expressed in pancreatic α-cells and intestinal L-cells in heterozygous Gcggfp/+ mice. The homozygous (Gcggfp/gfp) mice lack all PGDPs and display hyperplasia of GFP-positive “α”-cells in pancreatic islets but not of “L”-cells in the intestine (2,21). In the current study, we characterized glucose tolerance and β-cell function in Gcggfp/gfp mice to elucidate the consequences of PGDP deficiency on islet function and glucose homeostasis.

RESEARCH DESIGN AND METHODS

Animal studies.

The establishment of the glucagon--GFP knock-in mouse has been described previously in detail (21). Gcggfp/+ and Gipr+/− mice (22), which had been backcrossed to C57BL/6J background for at least eight generations, were provided by the RIKEN BRC through the National Bio-Resource Project of the MRXT (Japan). Double heterozygote Gcggfp/+ and Gipr+/− mice were intercrossed to obtain Gcggfp/+Gipr+/−, Gcggfp/gfpGipr+/−, and Gcggfp/+Gipr−/− single knockout littermates and Gcggfp/gfpGipr−/− double knockout (DKO) mice. All mice were housed in a temperature-controlled room under a standard 12-h light/dark cycle. All procedures were performed according to a protocol approved by the Nagoya University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Glucose tolerance test and measurement of insulin and GIP.

After 16 h of food deprivation in 12- to 26-week-old male mice, 2 g/kg body weight d-glucose was administered in OGTT or IPGTT. Blood was collected at the indicated times to measure glucose, insulin, and GIP levels. Blood glucose levels were measured with Antsense II (Horiba, Kyoto, Japan). Plasma levels of insulin and GIP were determined using a mouse insulin enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay kit (Morinaga, Tokyo, Japan) and a rat/mouse GIP (TOTAL) enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay kit (Millipore, Billerica, MA), respectively.

Islet isolation and measurement of insulin and GIP secretion and GIP content.

Pancreatic islets of 5- to 7-month-old male mice were isolated using the collagenase digestion method (23), and isolated islets were cultured for 2 h in RPMI 1640 medium containing 10% (volume/volume) fetal bovine serum under humidified conditions of 95% air and 5% CO2. The islets were incubated for 30 min with Krebs-Ringer buffer containing 2.8 mmol/L glucose. Thereafter, five size-matched islets were collected from each plate and then incubated in 100 µL of buffer containing 2.8, 4.2, or 16.7 mmol/L glucose for 30 min. In some experiments, 500 μmol/L Rp-cAMP was included in the incubation medium. Concentrations of insulin released into the medium and cellular insulin content were measured by radioimmunoassay (Eiken Chemical, Tokyo, Japan), and insulin secretion was normalized to cellular insulin content. To analyze GIP secretion, 10 islets were incubated in 100 μL RPMI 1640 medium containing 16.7 mmol/L glucose for 16 h and GIP concentration in the medium was determined by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay as described. For determination of insulin and GIP content, islets were lysed in acid ethanol, and cell extracts were collected. GIP content was normalized to insulin content.

Immunohistochemistry, morphometric analysis, and electron microscopy.

The pancreata of Gcg+/+, Gcggfp/+, Gcggfp/gfp, Gcggfp/gfpGipr−/−, Gcgr−/−, GLP-1 receptor knockout (Glp1r−/−), and Gcgr−/−Glp1r−/− mice were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde and embedded in paraffin. Sections were incubated overnight at 4°C with primary antibodies against insulin (1:500; Abcam, Tokyo, Japan), glucagon (1:500; Abcam), and GIP (1:500; Peninsula, San Carlos, CA), followed by 90-min incubation in Alexa Fluor-conjugated secondary antibody (1:300; Alexa Fluor 488 or Alexa Fluor 594; Invitrogen, Grand Island, NY) at room temperature. Fluorescent images of Alexa Fluor and GFP were taken using an HS BZ-9000 fluorescent microscope system (Keyence, Osaka, Japan) or LSM710 confocal microscope (Zeiss, Birkerod, Denmark). For morphometric analyses, the pancreata were resected from 9-week-old Gcg+/+ and Gcggfp/gfp male mice. Serial sections of 4-µm thickness were cut from each paraffin block at 200-µm intervals, and 5 sections were randomly selected from each mouse and immunostained for insulin and glucagon. The number of islets analyzed was 192 in Gcg+/+ mice and 745 in Gcggfp/gfp mice. The total area of islets, glucagon-positive or GFP-positive cells (α-cells), and insulin-positive cells (β-cells) relative to the sectional area or total pancreas area was determined by using the HS BZ-II analysis application. For conventional transmission electron microscopy, animals were perfused intracardially with 2% paraformaldehyde/2.5% glutaraldehyde. Pancreata were postfixed with 1% OsO4 and then processed using a standard method. Ultra-thin sections were examined by a JEOL-1210 electron microscope.

Isolation of tissue RNA and quantitative real-time RT-PCR.

Total RNA was isolated from the intestine and isolated islets using TRIzol reagent and the RNeasy Plus Kit (Qiagen, Tokyo, Japan), respectively. Synthesis of complementary DNA and quantitative real-time RT-PCR were performed with the ABI 7300 Real Time PCR System using a Power SYBR Green RNA to CT 1-Step kit (Applied Biosystems, Carlsbad, CA). The following oligonucleotide primers were used: mouse GIP, 5′-ATCCGACAACAAGACTTCGT-3′ (sense) and 5′-ATCATCACTGAGGCTCTTGG-3′ (antisense); and mouse GIP receptor, 5′-GGATCTTGGAGAGACCACACTC-3′ (sense) and 5′-TAAGATGAGTAGGGCTAGCAGCAG-3′ (antisense). The sequences of the primers used for mouse insulin 1 and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase have been described previously (21). The mRNA levels were normalized with respect to those of insulin 1 or glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase.

Statistical analysis.

Data are presented as mean ± SEM. Significance was evaluated using Student t test or ANOVA followed by posttest comparisons when applicable. P < 0.05 was regarded as statistically significant.

RESULTS

The Gcggfp/gfp mouse exhibits enhanced insulin secretion.

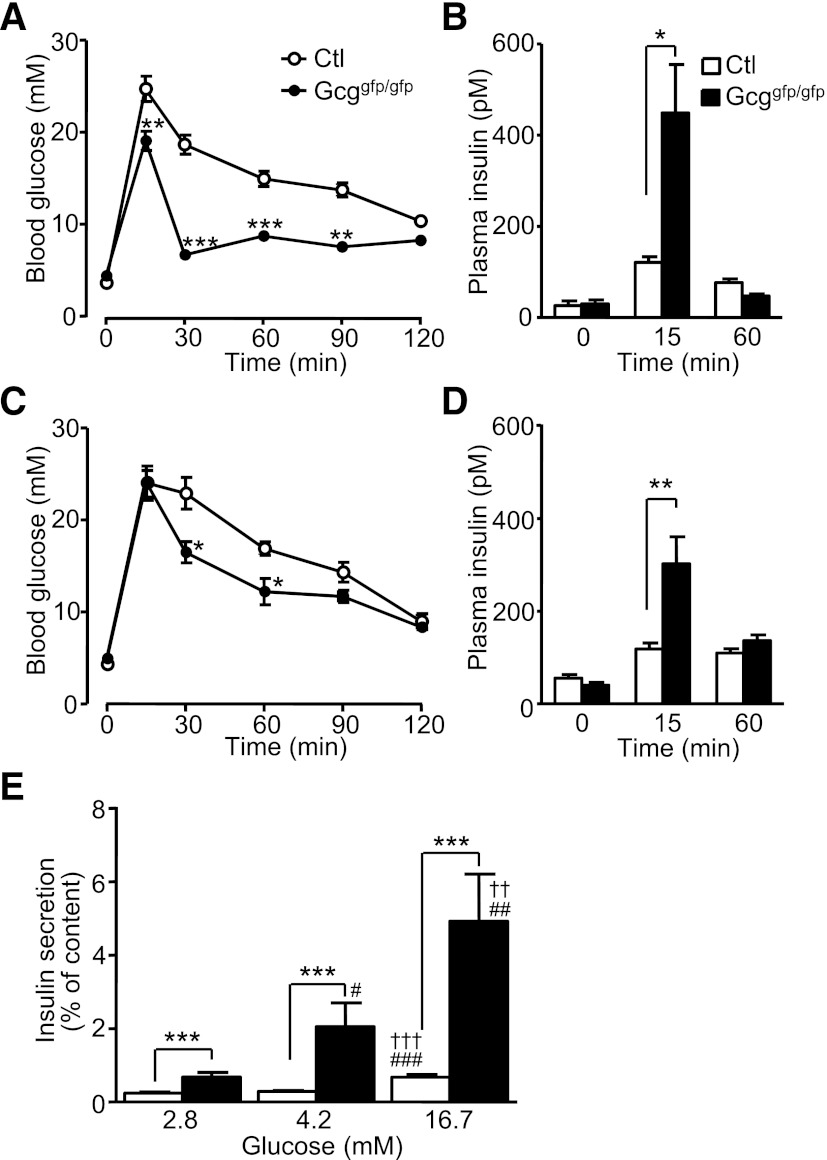

We first evaluated glucose tolerance and insulin secretion in Gcggfp/gfp mice. As shown in Fig. 1A and 1C, Gcggfp/gfp mice displayed improved oral and intraperitoneal glucose tolerance. Insulin secretion during the OGTT, in which secretion of incretins is stimulated, was significantly enhanced to a much greater extent despite lack of GLP-1 in Gcggfp/gfp compared with control mice (Fig. 1B). Significantly increased insulin responses in Gcggfp/gfp mice also were observed during the IPGTT, suggesting that compensatory mechanisms have evolved to upregulate β-cell function independent of the requirement for enteral glucose exposure (Fig. 1D). Because these results suggested that Gcggfp/gfp mice may have development of enhanced β-cell function in an autonomous manner, we examined glucose-induced insulin secretion from isolated islets. Insulin secretion from islets of Gcggfp/gfp mice at 2.8 mmol/L glucose was significantly higher than in islets from control mice (Fig. 1E). Insulin secretion from Gcggfp/gfp islets was significantly greater across a range of glucose levels, from 2.8 to 16.7 mmol/L (Fig. 1E).

FIG. 1.

Disruption of PGDPs improves glucose tolerance and enhances insulin secretion. Blood glucose levels (A) and plasma insulin levels (B) in the OGTT in 12- to 15-week-old control (Ctl, Gcg+/+ and Gcggfp/+) and Gcggfp/gfp mice (n = 5–6 mice per group). Blood glucose levels (C) and plasma insulin levels (D) in the IPGTT in 11- to 22-week-old mice (n = 9–10 mice per group). E: Glucose-induced insulin secretion from isolated islets. Pancreatic islets were isolated from 5- to 7-month-old control (Gcg+/+ and Gcggfp/+, n = 13–18 in each group) and Gcggfp/gfp (n = 8–9 in each group) mice and incubated with the indicated concentration of glucose for 30 min. Insulin secretion is expressed as the ratio of insulin released into the medium relative to insulin content. Values are expressed as means ± SEM. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001 vs. Ctl. ††P < 0.01. †††P < 0.001 vs. 4.2 mmol/L glucose. #P < 0.05; ##P < 0.01; ###P < 0.001 vs. 2.8 mmol/L glucose.

β-Cell mass is not increased in Gcggfp/gfp mice.

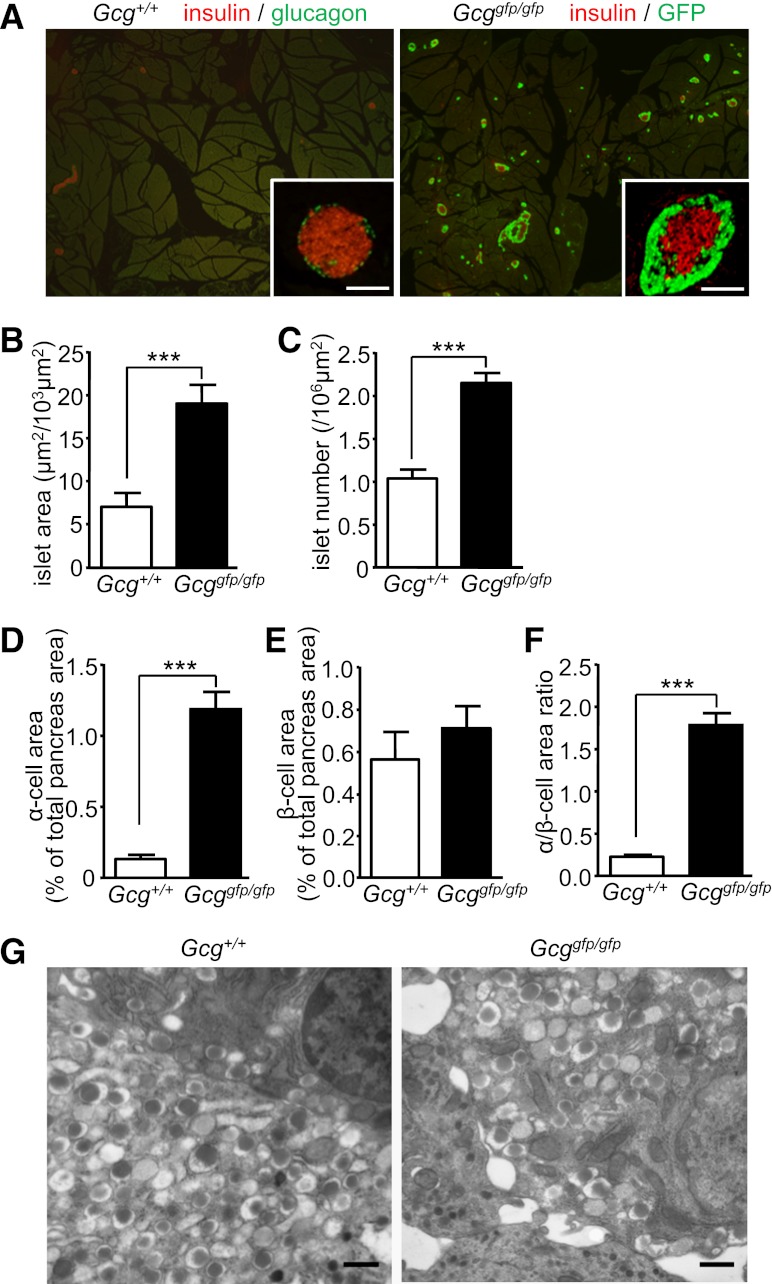

To understand the mechanisms by which Gcggfp/gfp mice exhibit improved islet function, we analyzed the morphology of pancreatic islets. Although by definition α-cells classically contain glucagon, we refer to GFP-positive cells in Gcggfp/gfp mice as α-cells for simplicity throughout this article. As shown in Fig. 2A, increased islet number and hyperplasia of GFP-positive “α”-cells were conspicuous in Gcggfp/gfp mice. Morphometric analysis revealed increases in both islet area and islet number in Gcggfp/gfp mice (Fig. 2B, C). Whereas the α-cell area in the pancreata of Gcggfp/gfp mice was significantly increased (Fig. 2D), the insulin-positive (β-cell) area in the pancreata of Gcggfp/gfp mice was similar to that in Gcg+/+ mice (Fig. 2E). Accordingly, the ratio of α-cell area to β-cell area was increased in Gcggfp/gfp mice (Fig. 2F). In electron microscopic analysis, the distribution of dense-core vesicles in β-cells, which contain insulin, was unchanged between Gcggfp/gfp and control mice (Fig. 2G). Hence, the increased β-cell function observed in Gcggfp/gfp mice in vivo is not secondary to increased numbers of β-cells.

FIG. 2.

Gcggfp/gfp mice exhibit α-cell hyperplasia. A: Representative pancreatic sections from 9-week-old Gcg+/+ (left) and Gcggfp/gfp (right) mice. In the left panel, sections were immunostained for glucagon (green) and insulin (red). In the right panel, sections were immunostained for insulin (red) and shown with autofluorescence of GFP. Scale bar, 100 µm. B–F: Morphometric analysis of islets. B: Islet area shown relative to a 103-µm2 sectional area. C: Islet number shown relative to a 106-µm2 sectional area. D: The α-cell area shown as glucagon-positive or GFP-positive area relative to total pancreas area. E: The β-cell area shown as insulin-positive area relative to total pancreas area. F: The α-cell/β-cell area ratio shown as a ratio of glucagon-positive or GFP-positive area relative to insulin-positive area. G: Electron microscopy of islets. Scale bar, 500 nm. Values are expressed as means ± SEM. ***P < 0.001. (A high-quality digital representation of this figure is available in the online issue.)

Gcggfp/gfp mice exhibit enhanced GIP secretion and increased GIP expression in pancreatic islets.

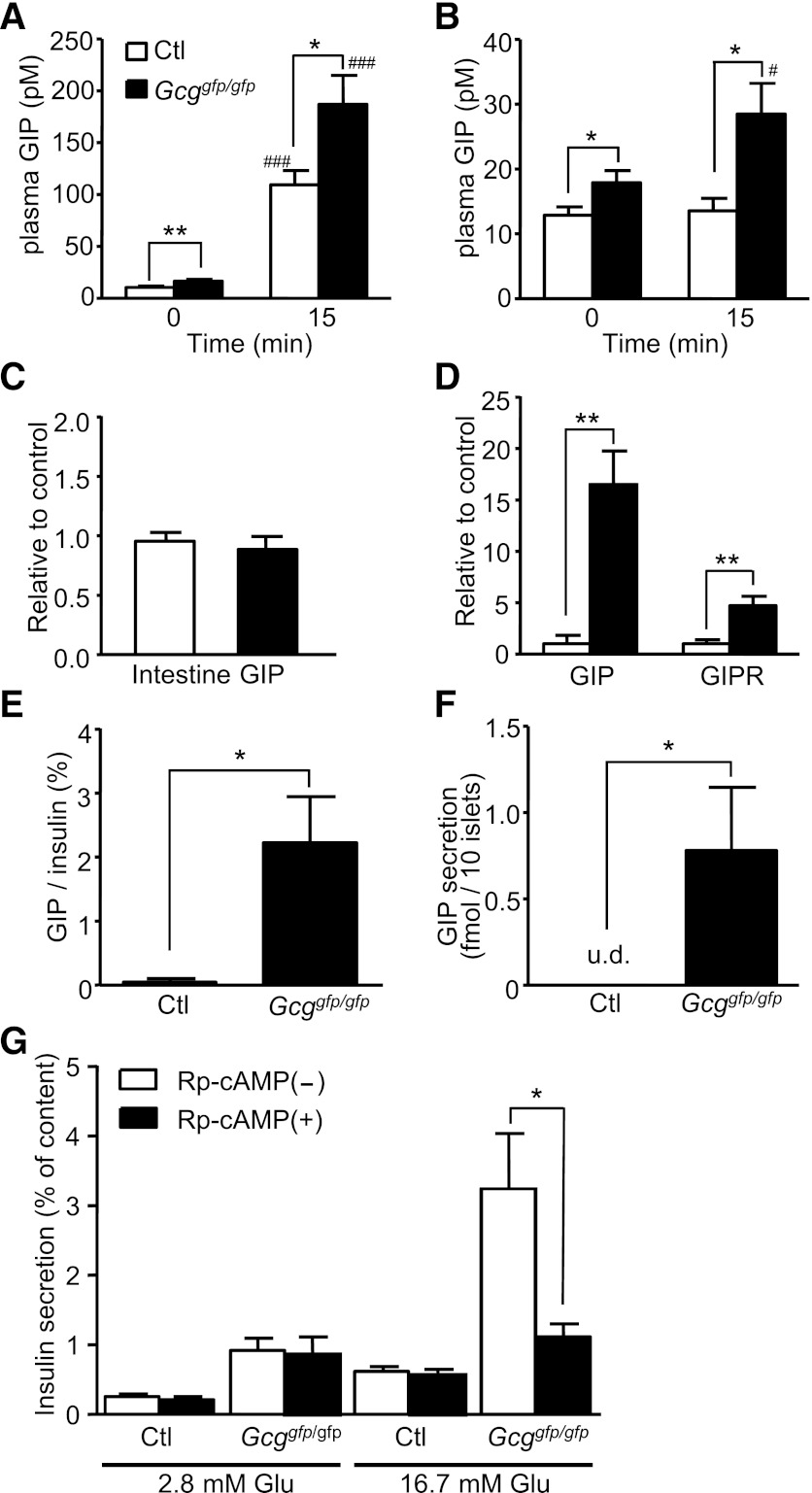

Because GIP secretion is increased in Glp1r−/− mice (24), we analyzed plasma GIP levels during OGTT and IPGTT in Gcggfp/gfp mice. As shown in Fig. 3A and 3B, plasma GIP levels at baseline in Gcggfp/gfp mice were modestly, yet significantly, higher than those in control mice. In the OGTT, plasma GIP levels at 15 min were increased both in the Gcggfp/gfp and in the control mice; however, GIP levels in the Gcggfp/gfp mice were significantly higher (Fig. 3A). Although circulating glucose levels do not classically influence intestinal GIP secretion, plasma GIP levels at 15 min were significantly increased in Gcggfp/gfp mice but not in control mice during the IPGTT (Fig. 3B). We then investigated whether GIP expression in the Gcggfp/gfp intestine is increased; however, levels of GIP mRNA expression in the intestine were comparable between Gcggfp/gfp and control mice (Fig. 3C).

FIG. 3.

Gcggfp/gfp mice display enhanced GIP secretion and GIP expression in pancreatic islets, and enhancement of glucose-induced insulin secretion is blocked by Rp-cAMP in Gcggfp/gfp mice. Plasma GIP levels at 0 and 15 min after oral (A) or intraperitoneal (B) glucose administration in 12- to 17-week-old control (Ctl, Gcg+/+, and Gcggfp/+) and Gcggfp/gfp mice (n = 6–11 mice per group). C: mRNA expression of GIP in the intestine (n = 6–8). The expression level of GIP mRNA was normalized to that of glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase mRNA. D: mRNA expression of GIP and GIP receptor (GIPR) in isolated islets (n = 4). The expression levels normalized to that of insulin 1 are shown. E: GIP content in isolated islets (n = 5–7). GIP content was normalized to insulin content. F: GIP secretion from islets (n = 5–8). Isolated islets were incubated with 16.7 mmol/L glucose for 16 h. G: Effect of Rp-cAMP on glucose-induced insulin secretion. Isolated islets from control (n = 14–22 in each group) and Gcggfp/gfp (n = 13–22 in each group) mice were incubated with the indicated concentration of glucose and 500 μmol/L Rp-cAMP for 30 min. Insulin secretion is expressed as the ratio of insulin released into the medium relative to insulin content. Values are expressed as means ± SEM. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01. #P < 0.05; ###P < 0.001 vs. 0 min. u.d., undetectable.

Recently, it has been reported that GIP is expressed in and secreted from pancreatic α-cells (25); therefore, we examined GIP expression in isolated islets. The expression levels of both GIP and GIPR mRNA in Gcggfp/gfp mice were markedly higher than those in control mice (Fig. 3D). GIP content in islets of Gcggfp/gfp mice also was significantly higher than in control islets (Fig. 3E). The GIP secreted from Gcggfp/gfp islets was detected after incubation in the presence of 16.7 mmol/L glucose for 16 h, whereas GIP was not detected in medium from Gcggfp/+ islets (Fig. 3F). The GIP secretion from Gcggfp/gfp islets also was undetectable when islets were incubated in 2.8 mmol/L glucose (data not shown). To elucidate the contribution of islet-derived GIP to augmented insulin secretion in Gcggfp/gfp mice, we analyzed the effect of blocking GIP signaling in isolated islets. Because GIP signaling is mostly mediated through intracellular cAMP signaling, we used Rp-cAMP, a cAMP antagonist that blocks activation of protein kinase A and Epac (26). Treatment with 500 μmol/L Rp-cAMP significantly attenuated glucose-induced insulin secretion from isolated islets of Gcggfp/gfp mice, whereas the insulin response to glucose in the control islets was not suppressed by Rp-cAMP (Fig. 3G). These results indicate that cAMP signaling plays a pivotal role in enhanced insulin secretion in Gcggfp/gfp islets and is consistent with a role for islet-derived GIP in augment islet function.

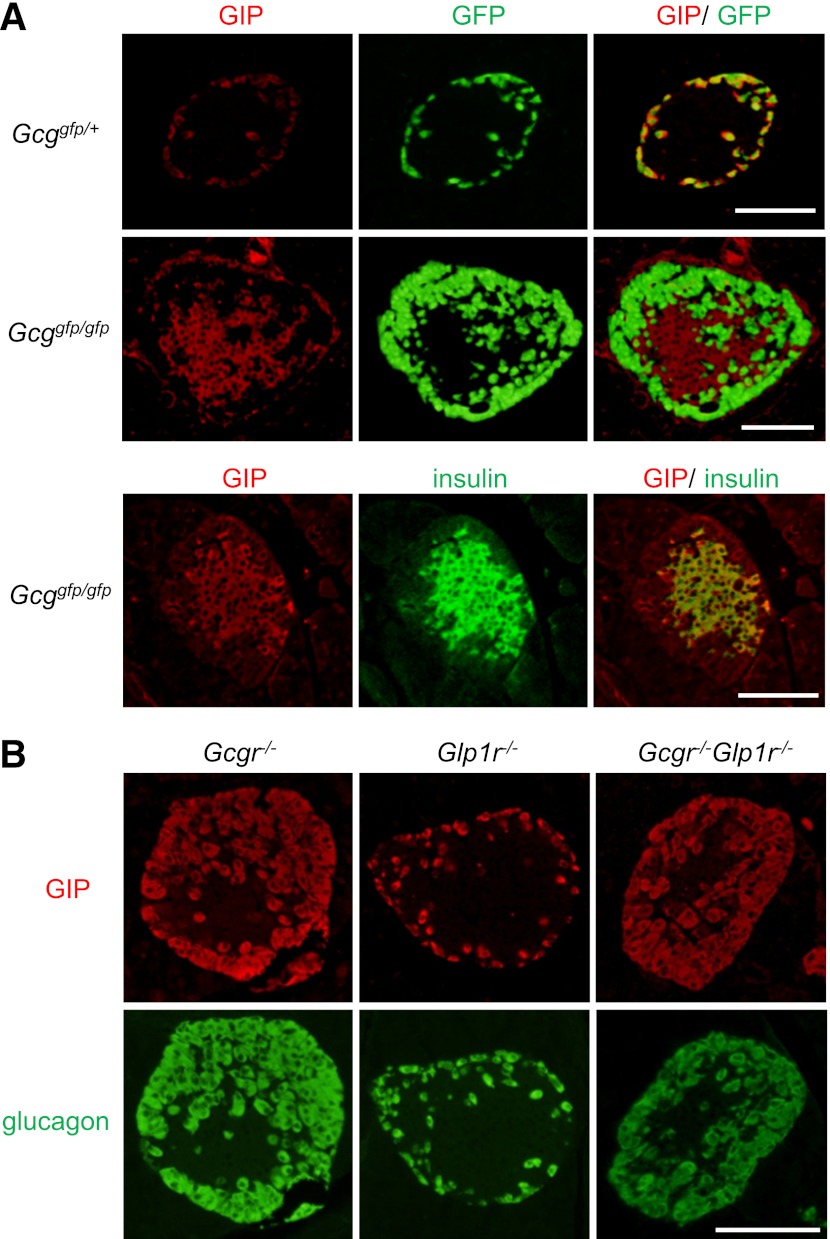

GIP is expressed in pancreatic β-cells in Gcggfp/gfp mice.

We next assessed the cellular localization of GIP in the islets. The GIP immunoreactivity was distributed in the islet periphery and colocalized with GFP expressed in α-cells in the islets of Gcggfp/+ mice as previously reported (25) (Fig. 4A). In contrast, GIP was predominantly present in insulin-positive cells in islets of Gcggfp/gfp mice (Fig. 4A); the localization of GIP immunoreactivity in β-cells was independently confirmed using another antibody for GIP (Supplementary Fig. 1). Interestingly, GIP expression in β-cells was observed at embryonic day 18.5 in both control and Gcggfp/gfp mice (Supplementary Fig. 2). To address the possible contribution of loss of glucagon and/or GLP-1 signaling in the altered intraislet expression pattern of GIP, we analyzed GIP expression in islets from mice deficient in GCGR (Gcgr−/−), GLP1R (Glp1r−/−), or both (Gcgr−/−Glp1r−/−) (27). As shown in Fig. 4B, GIP immunoreactivity was localized in α-cells in these animals, suggesting that induction of β-cell GIP expression in islets of Gcggfp/gfp mice does not arise secondary to loss of GCGR or GLP1R signaling. We also performed immunohistochemical localization of two transcription factors, namely Pdx1 and Pax6, which have been shown previously to regulate GIP expression in intestinal K-cells (28). However, no differences in expression patterns of these transcription factors in β-cells of Gcggfp/gfp or Gcggfp/+ mice (Supplementary Fig. 3) were observed, suggesting that transcription factors other than Pdx1 and Pax6 regulate GIP expression in β-cells.

FIG. 4.

GIP is expressed in pancreatic β-cells in Gcggfp/gfp mice, but not in Gcgr−/−, Glp1r−/−, or Gcgr−/−Glp1r−/− mice. A: Representative immunostaining for GIP (red) and insulin (green), and GFP fluorescence (green) of islets from Gcggfp/gfp mice and Gcggfp/+ mice. B: Representative immunostaining for GIP (red) and glucagon (green) of islets from Gcgr−/−, Glp1r−/−, and Gcgr−/−Glp1r−/− mice. Scale bar, 100 µm. (A high-quality digital representation of this figure is available in the online issue.)

Disruption of the Gipr gene abrogates enhanced insulin secretion in Gcggfp/gfp mice.

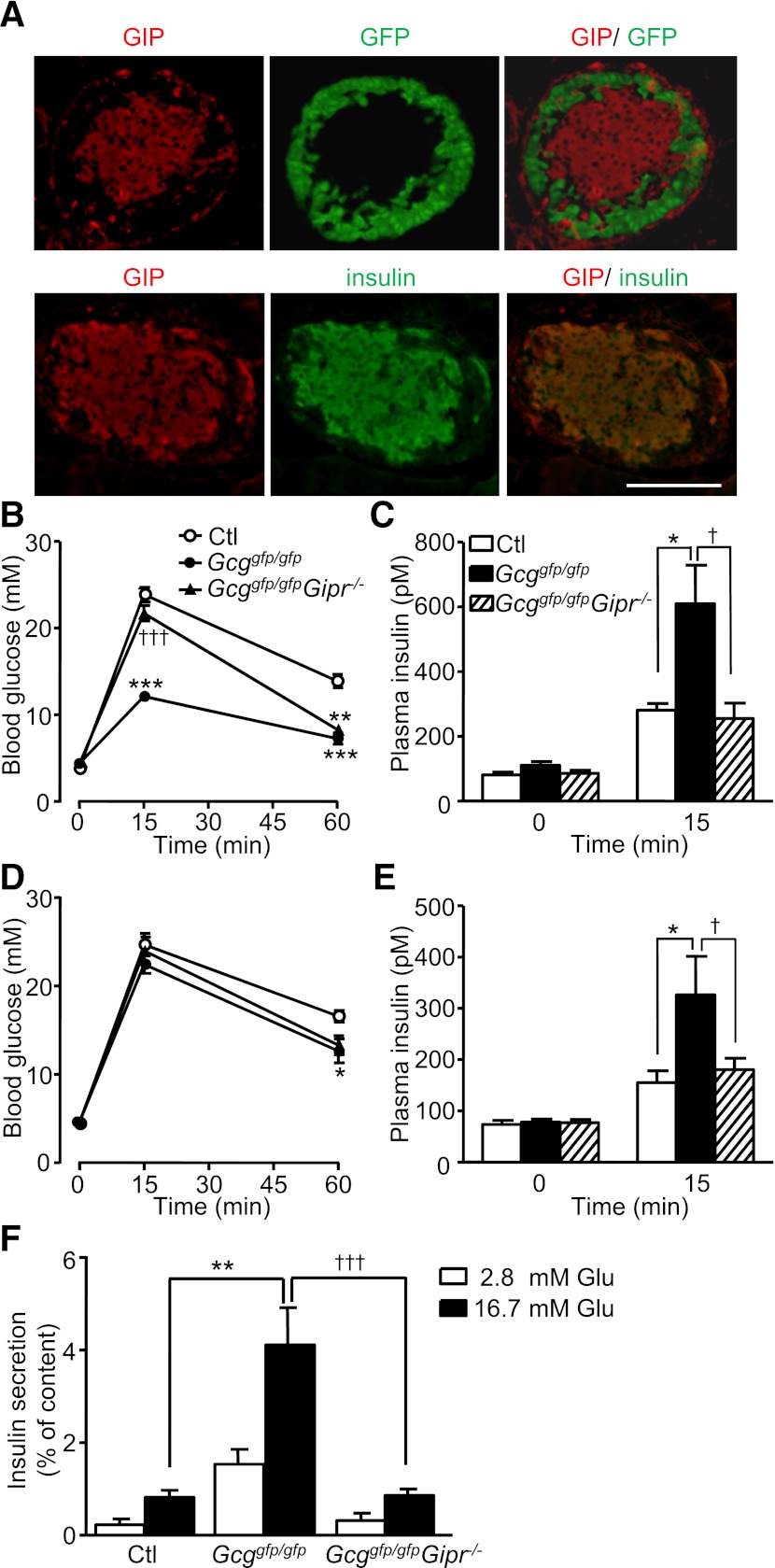

To clarify the contribution of enhanced GIP action in the phenotype of Gcggfp/gfp mice, we generated and analyzed Gcggfp/gfpGipr−/− DKO mice. As observed in Gcggfp/gfp mice, immunohistochemical analyses localized GIP to β-cells of Gcggfp/gfpGipr−/− DKO mice (Fig. 5A), thus ruling out the possibility that the action of GIP itself is required for the altered expression pattern of GIP in islets. The hyperplasia of GFP-positive α-cells in the Gcggfp/gfpGipr−/− DKO mice was comparable with that in the Gcggfp/gfp mice (data not shown), indicating that GIPR signaling is not required for hyperplasia of “α”-cells. We then examined glucose tolerance and insulin secretion in the Gcggfp/gfpGipr−/− DKO mice in comparison with Gcggfp/gfp and control mice. Blood glucose levels in the Gcggfp/gfpGipr−/− DKO mice at 15 min after oral glucose loading were higher than those in Gcggfp/gfp mice (Fig. 5B), and increased insulin levels in Gcggfp/gfp mice were comparatively diminished in Gcggfp/gfpGipr−/− mice to a similar degree to levels in control mice (Fig. 5C). During the IPGTT, blood glucose levels were comparable between all three groups (Fig. 5D), whereas plasma insulin levels at 15 min after intraperitoneal glucose administration were lower in Gcggfp/gfpGipr−/− mice and similar to those in control mice (Fig. 5E). Furthermore, the enhancement of glucose-induced insulin secretion from isolated islets of Gcggfp/gfp mice was markedly attenuated in Gcggfp/gfpGipr−/− mice (Fig. 5F). These findings indicate that islet-derived GIP potentiates glucose-induced insulin secretion.

FIG. 5.

Lack of GIP receptor signaling abrogates enhanced insulin secretion in Gcggfp/gfp mice. A: Representative immunostaining for GIP (red) and insulin (green), and GFP fluorescence (green) of islets from Gcggfp/gfpGipr−/− mice. Scale bar, 100 µm. B: Blood glucose levels during the OGTT in 15- to 24-week-old control (Ctl), Gcggfp/gfp, and Gcggfp/gfpGipr−/− mice (n = 5–7 mice per group). C: Plasma insulin levels at 0 and 15 min after oral glucose loading. D: Blood glucose levels during the IPGTT in 13- to 22-week-old mice (n = 6–8 mice per group). E: Plasma insulin levels 0 and 15 min after intraperitoneal glucose administration. F: Glucose-induced insulin secretion from isolated islets. Pancreatic islets were isolated from 5- to 7-month-old control (Ctl), Gcggfp/gfp, and Gcggfp/gfpGipr−/− mice, and then incubated with the indicated concentration of glucose for 30 min. Insulin secretion is expressed as the ratio of insulin released into the medium relative to insulin content. Values are expressed as means ± SEM. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001 vs. Ctl. †P < 0.05; †††P < 0.001 vs. Gcggfp/gfp, Ctl, Gcggfp/+Gipr+/−; Gcggfp/gfp, Gcggfp/gfpGipr+/+, and Gcggfp/gfpGipr+/−. (A high-quality digital representation of this figure is available in the online issue.)

DISCUSSION

In the current study, we characterized β-cell function in mice with absence of all PGDPs, including glucagon and GLP-1. Several studies using genetic and pharmacological suppression of glucagon signaling in animal models have demonstrated improvement not only of hepatic glucose metabolism but also of β-cell function (9–15). Deletion of the GCGR appears to increase GLP-1 production in islets, resulting in improved β-cell function (13,14,16). Although the Gcggfp/gfp mice lack glucagon, it was assumed that β-cell function in the Gcggfp/gfp mice would be impaired because of concomitant lack of GLP-1. Unexpectedly, however, we observed improved glucose tolerance and enhanced β-cell function in Gcggfp/gfp mice. These findings strongly suggest the emergence of novel compensatory mechanisms that maintain β-cell function in Gcggfp/gfp mice. Because GIP secretion was enhanced in Gcggfp/gfp mice (Fig. 4), the possible involvement of GIP was further explored in this study.

Glp1r−/− mice exhibit increased GIP secretion and sensitivity, which compensates for the lack of GLP-1 action (24). Mice lacking both the GLP1R and the GCGR show enhanced GIP sensitivity in islets, even though GIP levels are not increased (27). Interestingly, upregulation of GIPR mRNA levels was observed in Gcggfp/gfp islets, suggesting that enhanced GIP action serves as one of the compensatory mechanisms for lack of GLP-1 signaling. Gcgr−/−Glp1r−/− mice are similar to Gcggfp/gfp mice in that they lack both glucagon and GLP-1 signaling, but they exhibit preferential preservation of insulin secretion during the OGTT but not the IPGTT (27). In contrast, our findings of enhanced insulin secretion during both OGTT and IPGTT suggested that unlike findings in Gcgr−/−Glp1r−/− mice, enteral glucose–stimulated gut–derived factors were not likely to account for the enhanced β-cell function in Gcggfp/gfp mice.

Recently, it has been reported that GIP is expressed in pancreatic α-cells (25); however, whether GIP secretion from α-cells is stimulated by glucose remains unclear. It has been demonstrated that GIP secretion from intestinal K-cells is not stimulated by intraperitoneal glucose loading (1,18). The current study demonstrates that serum GIP levels are increased during the IPGTT in Gcggfp/gfp, but not in control mice. Furthermore, we confirmed enhanced GIP secretion from Gcggfp/gfp islets and GIP expression in β-cells in Gcggfp/gfp islets (Figs. 3F and 4A). These results suggest that glucose stimulates GIP secretion from β-cells of Gcggfp/gfp islets but not from normal islets, and are consistent with the functional observations. The mechanisms underlying emergence of GIP expression in β-cells remain unclear. Because GIP expression is observed in α-cells but not β-cells of Gcgr−/−, Glp1r−/−, and Gcgr−/−Glp1r−/− mice, as well as in controls, the loss of glucagon or GLP-1 action does not contribute to β-cell GIP expression. In addition, GIP expression was observed in β-cells in Gcggfp/gfpGipr−/− mice, demonstrating that GIP itself is not required to induce GIP expression in β-cells.

Both blockade of GIP signaling by a cAMP antagonist in vitro (Fig. 3F) and elimination of the GIPR in vivo (Fig. 5) blunted the enhanced insulin response to glucose in Gcggfp/gfp mice. These results indicate that islet-derived GIP augments glucose-induced insulin secretion in an autocrine and/or paracrine manner in Gcggfp/gfp mice. However, enhanced endogenous GIP action does not appear to increase β-cell mass in Gcggfp/gfp islets. This observation may reflect a permissive need for elevated glucose levels to reveal the proliferative actions of GIP and is in accord with reports that GLP-1 promotes proliferation and survival of β-cells more strongly than GIP under hyperglycemic conditions (29).

In the current study, we demonstrate that glucose-induced insulin secretion by Gcggfp/gfpGipr−/− islets is comparable with that of control islets both in vivo and in vitro. These results contrast with observations in another model deficient in actions of both GLP-1 and GIP. Mice deficient in receptors for both GLP-1 and GIP (Glp1r−/−Gipr−/−) showed impaired insulin secretion in response to oral glucose administration compared with controls (30). During the course of the current study, it was reported that blockade of glucagon receptor expression improved oral glucose tolerance in Glp1r−/−Gipr−/− mice (27). It was also shown that islet expression of cholecystokinin A receptor and G-protein-coupled receptor 119 are increased on blockade of glucagon receptor expression and are involved in improved glucose tolerance (27). Such mechanisms also may contribute to the relative improvement in glucose tolerance in Gcggfp/gfpGipr−/− mice compared with Glp1r−/−Gipr−/− mice.

In animal models deficient in glucagon activity, hyperplasia of α-cells or GFP-positive cells in Gcggfp/gfp islets has been observed. However, the mechanisms underlying hyperplasia remain largely unelucidated. Although glucagon itself may directly suppress proliferation of α-cells, several findings indicate that indirect signals arising from glucagon target organs also may play important roles in the development of hyperplasia. It has been reported that mice with liver-specific GSα deficiency display pancreatic α-cell hyperplasia (31), indicating that the direct effect of glucagon on α-cells is insufficient to block aberrant α-cell proliferation. Recently, Imai et al (32) have demonstrated that signals from the liver mediated through the autonomic nervous system regulate β-cell proliferation. In addition, it has been demonstrated that hepatic metabolism, especially amino acid metabolism, is remodeled in animal models deficient in glucagon action (33,34). Such metabolic and/or neural signals from extraislet organs also may be involved in altered proliferation and function of α-cells. These indirect mechanisms also may account for the aberrant expression of GIP observed in β-cells of Gcggfp/gfp islets.

Glucagon is believed not to cross the placenta (35). Because hyperplasia of α-cells gradually develops after birth in Gcggfp/gfp mice, this is consistent with loss of glucagon signaling indirectly contributing to the development of α-cell hyperplasia, as suggested by Chen et al. (31). GIP expression in β-cells is observed at embryonic day 18.5 in both control and Gcggfp/gfp mice (Supplementary Fig. 2). These findings differ from a previous report that showed that GIP was generally coexpressed with glucagon by immunostaining (36). Although Gcggfp/+ mice expressed GIP in both insulin-positive β-cells and in insulin-negative cells that may be α-cells, GIP is expressed only in β-cells in Gcggfp/gfp mice. This difference in GIP distribution between Gcggfp/+ and Gcggfp/gfp can be detected by embryonic day 18.5, when α-cell hyperplasia has not developed in Gcggfp/gfp mice. Therefore, these findings indicate that α-cell hyperplasia is not a prerequisite for altered GIP expression in islets.

In conclusion, we demonstrate that elimination of PGDPs results in enhancement of β-cell function that can be attributed to induction of GIP expression in β-cells. It is recognized that GIP is one of the most important factors in the regulation of insulin secretion when blood glucose levels increase after ingestion of nutrients (18). Our results show that GIP produced by β-cells is secreted when blood glucose levels increase, even if nutrients are not ingested via the gastrointestinal tract. Future investigations should elucidate the conditions required for and mechanisms underlying the ectopic expression of GIP in β-cells.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported in part by grants-in-aid for Scientific Research from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (22590974 to N.O. and 21659232 to Y.H.) and a grant-in-aid for Scientific Research from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology–Japan (23122507 to Y.H.). D.J.D. is supported by a Canada Research Chair in Regulatory Peptides, a BBDC-Novo Nordisk Chair in Incretin Biology, and Canadian Institute for Health Research operating grants 93749 and 82700.

No potential conflicts of interest relevant to this article were reported.

A.F., Yus.S. M.Y., C.S., E.S.-M., T.H., Y.T., S.A., Y.H., and N.O. researched data. A.F., Yus.S., S.T., D.J.D., Y.M., Yut.S., Y.O., Y.H., and N.O. contributed to discussion. A.F. wrote the manuscript. Yus.S., S.T., D.J.D., Y.M., Yut.S., and Y.O. reviewed the manuscript. Y.H. and N.O. edited the manuscript. N.O. is the guarantor of this work and had full access to all the data, and takes full responsibility for the integrity of data and the accuracy of data analysis.

The authors are indebted to Dr. Maureen Charron (Albert Einstein College of Medicine, New York, NY) for facilitation of the study with Gcgr−/− tissues. The authors are grateful to Dr. Susumu Seino (Kobe University Graduate School of Medicine, Kobe, Japan) and Nobuya Inagaki (Kyoto University Graduate School of Medicine, Kyoto, Japan) for their helpful discussion and suggestions. The authors also thank Dr. Harumi Takahashi (Kobe University Graduate School of Medicine, Kobe, Japan) for technical assistance with islet experiments, Osamu Takahashi (Keyence, Osaka, Japan) for expert technical assistance with fluorescence microscopy, and Michiko Yamada and Mayumi Katagiri (Nagoya University Graduate School of Medicine, Nagoya, Japan) for technical assistance.

Footnotes

This article contains Supplementary Data online at http://diabetes.diabetesjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.2337/db12-0294/-/DC1.

REFERENCES

- 1.Baggio LL, Drucker DJ. Biology of incretins: GLP-1 and GIP. Gastroenterology 2007;132:2131–2157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hayashi Y. Metabolic impact of glucagon deficiency. Diabetes Obes Metab 2011;13(Suppl 1):151–157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Unger RH. Glucagon physiology and pathophysiology in the light of new advances. Diabetologia 1985;28:574–578 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jiang G, Zhang BB. Glucagon and regulation of glucose metabolism. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 2003;284:E671–E678 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cherrington AD, Chiasson JL, Liljenquist JE, Lacy WW, Park CR. Control of hepatic glucose output by glucagon and insulin in the intact dog. Biochem Soc Symp 1978;43:31–45 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baron AD, Schaeffer L, Shragg P, Kolterman OG. Role of hyperglucagonemia in maintenance of increased rates of hepatic glucose output in type II diabetics. Diabetes 1987;36:274–283 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shah P, Vella A, Basu A, Basu R, Schwenk WF, Rizza RA. Lack of suppression of glucagon contributes to postprandial hyperglycemia in subjects with type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2000;85:4053–4059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dallas-Yang Q, Shen X, Strowski M, et al. Hepatic glucagon receptor binding and glucose-lowering in vivo by peptidyl and non-peptidyl glucagon receptor antagonists. Eur J Pharmacol 2004;501:225–234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brand CL, Rolin B, Jørgensen PN, Svendsen I, Kristensen JS, Holst JJ. Immunoneutralization of endogenous glucagon with monoclonal glucagon antibody normalizes hyperglycaemia in moderately streptozotocin-diabetic rats. Diabetologia 1994;37:985–993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gelling RW, Du XQ, Dichmann DS, et al. Lower blood glucose, hyperglucagonemia, and pancreatic α cell hyperplasia in glucagon receptor knockout mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2003;100:1438–1443 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liang Y, Osborne MC, Monia BP, et al. Reduction in glucagon receptor expression by an antisense oligonucleotide ameliorates diabetic syndrome in db/db mice. Diabetes 2004;53:410–417 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Parker JC, Andrews KM, Allen MR, Stock JL, McNeish JD. Glycemic control in mice with targeted disruption of the glucagon receptor gene. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2002;290:839–843 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sloop KW, Cao JX, Siesky AM, et al. Hepatic and glucagon-like peptide-1-mediated reversal of diabetes by glucagon receptor antisense oligonucleotide inhibitors. J Clin Invest 2004;113:1571–1581 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sørensen H, Winzell MS, Brand CL, et al. Glucagon receptor knockout mice display increased insulin sensitivity and impaired β-cell function. Diabetes 2006;55:3463–3469 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Winzell MS, Brand CL, Wierup N, et al. Glucagon receptor antagonism improves islet function in mice with insulin resistance induced by a high-fat diet. Diabetologia 2007;50:1453–1462 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Conarello SL, Jiang G, Mu J, et al. Glucagon receptor knockout mice are resistant to diet-induced obesity and streptozotocin-mediated beta cell loss and hyperglycaemia. Diabetologia 2007;50:142–150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Seino Y, Fukushima M, Yabe D. GIP and GLP-1, the two incretin hormones: Similarities and differences. J Diabetes Invest 2010;1:8–23 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cho YM, Kieffer TJ. K-cells and glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide in health and disease. Vitam Horm 2010;84:111–150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Taminato T, Seino Y, Goto Y, Inoue Y, Kadowaki S. Synthetic gastric inhibitory polypeptide. Stimulatory effect on insulin and glucagon secretion in the rat. Diabetes 1977;26:480–484 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Christensen M, Vedtofte L, Holst JJ, Vilsbøll T, Knop FK. Glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide: a bifunctional glucose-dependent regulator of glucagon and insulin secretion in humans. Diabetes 2011;60:3103–3109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hayashi Y, Yamamoto M, Mizoguchi H, et al. Mice deficient for glucagon gene-derived peptides display normoglycemia and hyperplasia of islet α-cells but not of intestinal L-cells. Mol Endocrinol 2009;23:1990–1999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Miyawaki K, Yamada Y, Yano H, et al. Glucose intolerance caused by a defect in the entero-insular axis: a study in gastric inhibitory polypeptide receptor knockout mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1999;96:14843–14847 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wollheim CB, Meda P, Halban PA. Isolation of pancreatic islets and primary culture of the intact microorgans or of dispersed islet cells. Methods Enzymol 1990;192:188–223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pederson RA, Satkunarajah M, McIntosh CH, et al. Enhanced glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide secretion and insulinotropic action in glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor -/- mice. Diabetes 1998;47:1046–1052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fujita Y, Wideman RD, Asadi A, et al. Glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide is expressed in pancreatic islet α-cells and promotes insulin secretion. Gastroenterology 2010;138:1966–1975 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Seino S, Shibasaki T. PKA-dependent and PKA-independent pathways for cAMP-regulated exocytosis. Physiol Rev 2005;85:1303–1342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ali S, Lamont BJ, Charron MJ, Drucker DJ. Dual elimination of the glucagon and GLP-1 receptors in mice reveals plasticity in the incretin axis. J Clin Invest 2011;121:1917–1929 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fujita Y, Chui JW, King DS, et al. Pax6 and Pdx1 are required for production of glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide in proglucagon-expressing L cells. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 2008;295:E648–E657 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Maida A, Hansotia T, Longuet C, Seino Y, Drucker DJ. Differential importance of glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide vs glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor signaling for beta cell survival in mice. Gastroenterology 2009;137:2146–2157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hansotia T, Baggio LL, Delmeire D, et al. Double incretin receptor knockout (DIRKO) mice reveal an essential role for the enteroinsular axis in transducing the glucoregulatory actions of DPP-IV inhibitors. Diabetes 2004;53:1326–1335 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chen M, Mema E, Kelleher J, et al. Absence of the glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor does not affect the metabolic phenotype of mice with liver-specific G(s)α deficiency. Endocrinology 2011;152:3343–3350 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Imai J, Katagiri H, Yamada T, et al. Regulation of pancreatic β cell mass by neuronal signals from the liver. Science 2008;322:1250–1254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Watanabe C, Seino Y, Miyahira H, et al. Remodeling of hepatic metabolism and hyperaminoacidemia in mice deficient in proglucagon-derived peptides. Diabetes 2012;61:74–84 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yang J, MacDougall ML, McDowell MT, et al. Polyomic profiling reveals significant hepatic metabolic alterations in glucagon-receptor (GCGR) knockout mice: implications on anti-glucagon therapies for diabetes. BMC Genomics 2011;12:281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Spellacy WN, Buhi WC. Glucagon, insulin and glucose levels in maternal and imbilical cord plasma with studies of placental transfer. Obstet Gynecol 1976;47:291–294 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Prasadan K, Koizumi M, Tulachan S, et al. The expression and function of glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide in the embryonic mouse pancreas. Diabetes 2011;60:548–554 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]