Abstract

Adults with Sickle Cell Disease (SCD) experience multiple disease-related complications, but few studies have examined relationships between these events and health-related quality of life (HRQOL). We determined the number and type of previous or co-occurring SCD related complications and their reported HRQOL in a cohort of 1046 adults from the Comprehensive Sickle Cell Centers (CSCC). Participants had a median age of 28.0 years (48% male, 73% SS or Sβ0 thalassemia) and had experienced several SCD-related complications (mean 3.8 ± 2.0), which were influenced by age, gender and hemoglobinopathy type (p<0.0001). In multivariate models, increasing age reduced all SF-36 scales scores (p<0.05) except mental health, while female gender additionally diminished physical function and vitality scale scores (p< 0.01). Of possible complications, only vaso-occlusive crisis, asthma, or avascular necrosis diminished SF-36 scale scores. Chronic antidepressants usage predominantly diminished scores on bodily pain, vitality, social functioning, emotional role, and mental health scales, while chronic opioid usage diminished all scale scores (p<0.01). Our study documents substantial impairment of HRQOL in adults with SCD that was influenced by only a few of many possible medical complications. It suggests that more effective treatments of persistent pain and depression would provide the largest HRQOL benefit.

Keywords: Quality of life, Sickle Cell Disease, SF-36, pain, complications

The burden of disease for the patient and the complexity of disease management for the healthcare team are increased (1, 2) when multiple concurrent medical conditions (3-5) or medical and mental health conditions (6-8) occur in primary care and/or aging populations. A number of diseases, such as sickle cell disease, can impact a variety of organ systems resulting in multiple different disease-related symptoms or complications. However, the extent of co-existent multiple medical complications in SCD have not been well described. Most previous large natural history studies, such as those from the Cooperative Study of Sickle Cell Disease (CSSCD) (9), focused on in-depth characterizations of specific complications. The relationship of SCD complications to diminished HRQOL has been established for frequent sickle pain or opioid usage (10-13). The small size of these prior HRQOL studies limited their ability to examine the HRQOL effects of other less frequent SCD complications.

During the 2003-2008 funding cycle of the Comprehensive Sickle Cell Centers, the investigators developed and implemented a clinical database (the C-Data Project) to record the occurrence of 62 selected SCD complications in a cohort of adults and children seen at the participating clinical sites. Nineteen of these SCD-related complications were selected for use in this study based on their clinical relevance, relative frequency, and their potential influence on HRQOL (14). Of the 1180 enrolled subjects, 1067 individuals completed Medical History I and II, and the SF-36 (See Methods). The average age of the 545 women (52%) and 501 men (48%) was 31.4 years (standard deviation [SD] 11.8) with a range of 18 to 72 years (median 28 years). The participants were largely Black (90%) of non-Hispanic ethnicity (92%). The sample included 763 adults with SS or Sβ0 thalassemia (73%) and 283 adults with SC or Sβ+ thalassemia (27%). (Table I Supplemental materials)

The prior occurrence of acute vaso-occlusive (sickle cell) pain was the most common complication (89%) followed by acute chest syndrome (69%), and gall bladder disease (49%). A number of chronic complications were relatively common, including avascular necrosis of the hips/shoulders (AVN) (29%), transfusion-related iron overload (17%), priapism (16%), leg ulcers (12%), and retinopathy (12%). Two distinct associated medical conditions were prevalent: asthma (20%) and hypertension (12%). Continuous use of oral opioids greater than 30 days in the prior year was reported by 37%, while oral antidepressants use was reported by 11%. (Table I Supplemental materials)

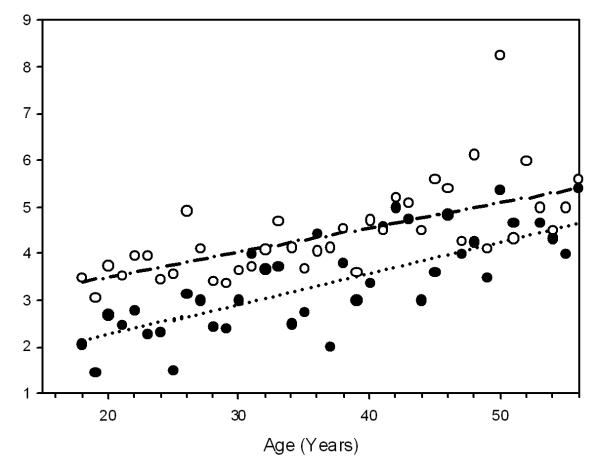

Most adults had experienced more than one SCD-related complication (mean 3.8 ± 2.0, median 4), and more than one affected organ system (mean 3.3 ± 1.5, median 3) (Figure 1A, 1B of the Supplemental materials). The number of complications increased substantially with increasing age (p<0.001). Persons with SS or Sβ0 thalassemia reported significantly more complications at any age than individuals with SC or Sβ+ thalassemia (p<0.001), a finding present in both females and males (Figure 1). These findings are consistent with previous studies reporting a milder initial clinical course and longer life expectancy for those individuals with SC or Sβ+ thalassemia (15, 16).

Figure 1.

Relationship Between Age and the Mean Number of Complications per Individual

The SF-36™ version 2.0 (17) is a non-disease-specific measure of HRQOL that has 36 items to assess 8 aspects of health: physical functioning, physical role functioning, emotional role functioning, social functioning, pain, mental health, general health, vitality. General health is separately rated using a 5 point categorical scale from excellent to poor, while change in health since the previous year is rated using a 5 point categorical scale from much better to much worse. Two-hundred twenty-four subjects (22%) rated their health status as fair or poor (Figure 2A supplemental materials). In an ordinal logistic model, a higher probability of reporting poor health status was associated with increasing age (p< 0.01, odds ratio (OR) 1.4, 95% CI 1.2-1.5 for every additional 10 years of age), usage of opioid analgesics (p<0.01, OR 2.0, 95% CI 1.5-2.7), previous occurrence of vaso-occulsive pain (p<0.01, OR 2.2, 95% CI 1.3-3.6), or asthma (p<0.05, OR 1.4, 95% CI 1.0-1.9). Participants also reported their current health status compared to the previous year. In our sample, 386 subjects (37%) rated their general health as somewhat worse or much worse than the previous year (Figure 2B supplemental materials).

All individual SF-36 scale scores were significantly decreased compared to the general US population (mean of 50), particularly on the general health scale, while the vitality and mental health scales were less severely decreased (Table I), similar to a previous study (12). With the exception of the mental health scales, a consistent clinically significant decrement in scale scores was evident with advancing age, with almost all of the declines occurring between the 18-19, 20-29, and 30-39 age groups (Table I). In exploratory regression tree models, the prior occurrence of some medical complications was not associated with significant changes in scale scores, including acute chest syndrome, gall bladder disease (cholelithiasis), retinopathy, proteinuria, pulmonary hypertension, viral hepatitis, osteomyelitis, and renal insufficiency. The occurrence of several other complications, associated conditions, or usage of medication, including pain, the frequent usage of oral opioids, AVN of the shoulders/hips, asthma, leg ulcers, and usage of oral antidepressants had statistically significant individual effects (p<0.05) on scale scores. Table II shows the effect of these variables when subsequently entered into multiple regression models for each SF-36 subscale. Gender, age, frequent opioid usage, asthma (all p<0.01), and to a lesser extent AVN (p<0.05), were associated with diminished scores on the physical functioning scale of the SF-36. Age (p<0.05), antidepressant usage (p<0.05), and frequent opioid usage (p<0.01) were associated with diminished scores on all scale scores except mental health. The occurrence of asthma further reduced (p<0.05) role physical, bodily pain, general health, and vitality scales, while the occurrence of sickle pain further reduced (p<0.05) bodily pain, general health, and vitality scales. Antidepressant usage or the frequent usage of opioids were the only complications that reduced mental health scale scores (p<0.01). The presence of leg ulcers did not have a significant added effect on any of the scale scores.

Table I.

SF-36 scores by Age Group

| Entire Population |

18-19 Years |

20-29 Years |

30-39 Years |

40-49 Years |

50-72 Years |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (N=1046) | (N=179) | (N=403) | (N=226) | (N=139) | (N=99) | ||

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | p-value* | |

| Physical Functioning | 41.8 (11.1) | 45.7 (10.0) | 44.5 (9.7) | 40.1 (11.0) | 36.9 (11.1) | 34.9 (11.8) | <0.001 |

| Role-Physical | 40.8 (11.2) | 44.8 (10.5) | 42.4 (10.9) | 38.5 (11.2) | 37.1 (10.8) | 37.1 (10.7) | <0.001 |

| Bodily Pain | 40.7 (11.5) | 45.7 (12.3) | 41.4 (11.3) | 38.5 (11.0) | 37.7 (10.1) | 37.9 (10.1) | <0.001 |

| General Health | 37.5 (10.7) | 41.5 (11.1) | 37.9 (10.2) | 36.4 (11.1) | 34.1 (9.7) | 35.8 (10.5) | <0.001 |

| Vitality | 46.6 (10.6) | 49.7 (10.8) | 47.0 (10.6) | 44.5 (10.8) | 45.3 (10.0) | 45.5 (10.0) | <0.001 |

| Social Functioning | 41.5 (11.7) | 45.5 (10.0) | 42.7 (11.5) | 39.2 (12.4) | 37.6 (11.6) | 40.7 (11.0) | <0.001 |

| Role-Emotional | 41.6 (13.9) | 44.4 (12.4) | 43.4 (13.2) | 39.6 (14.2) | 37.5 (15.5) | 40.1 (13.9) | <0.001 |

| Mental Health | 46.3 (11.4) | 48.3 (10.1) | 46.6 (11.2) | 44.8 (12.5) | 44.4 (11.9) | 47.5 (10.4) | 0.082 |

| Physical Summary Measure |

39.6 (10.0) | 44.3 (9.4) | 41.3 (9.1) | 37.8 (9.5) | 35.6 (9.6) | 34.1 (10.4) | <0.001 |

| Mental Summary Measure |

45.6 (11.9) | 47.6 (10.4) | 46.0 (11.4) | 43.8 (12.8) | 43.5 (13.4) | 47.4 (11.5) | 0.070 |

P-value from separate simple linear regression models with each SF36 score as a dependent variable and continuous age as the independent variable.

Table II.

Effects of Medications/Medical Complications on SF-36 Scores

| Gender | Age | Phenotype | Antidepressant | Opioid Usage |

AVN | Leg Ulcers |

Asthma | VOC | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physical Functioning |

-3.54** | -0.25** | -0.33 | -0.92 | -4.46** | -1.85* | -1.36 | -2.77** | -2.30 |

| Role-Physical | 0.02 | -0.19** | -0.00 | -2.49* | -4.54** | -1.19 | 2.01 | -2.57** | -1.77 |

| Bodily Pain | -0.99 | -0.16** | -1.35 | -3.30* | -5.76** | 0.21 | 0.77 | -2.30* | -4.61** |

| General Health |

-0.43 | -0.13** | 0.35 | -2.91* | -4.27** | -0.59 | 1.15 | -2.10* | -5.46** |

| Vitality | -3.33** | -0.07* | -0.40 | -6.36** | -3.14** | 0.35 | 1.44 | -1.96* | -3.37* |

| Social Functioning |

-0.98 | -0.12** | -1.64 | -6.20** | -4.55** | -0.10 | 0.34 | -1.20 | -2.50 |

| Role- Emotional |

0.50 | -0.17** | 0.04 | -6.35** | -3.83** | -0.18 | 2.40 | -2.68* | 0.16 |

| Mental Health | -0.75 | -0.01 | -1.04 | -7.00** | -2.41** | 0.12 | 0.27 | -1.44 | -0.35 |

| Physical Summary Measure |

-1.87** | -0.22** | -0.15 | -0.44** | -5.18** | -1.24 | 0.20 | -2.48** | -4.45** |

| Mental Summary Measure |

-0.24 | -0.03 | -0.73 | -8.63** | -2.57** | 0.55 | 1.66 | -1.40 | -0.29 |

p< 0.01

0.01<p ≤ 0.05 P-values are from multiple linear regression models controlling for all listed covariates. Male and SS-SB0 thalassemia are the reference levels for gender and phenotype, respectively.

The PiSCES study found that the frequency of home opioid usage was predictive of the frequency of daily pain in the PiSCES study (9). Mean daily pain intensity had a similar broad negative effect on SF-36 domain scores (10) as observed for chronic opioid usage in this study. Pain occurrence is also associated with additional decrements in HRQOL in a number of other chronic disorders including rheumatoid arthritis (22), inflammatory bowel disease (23), and AIDS (24). Similar additive decrements have been noted for combinations of a number of medical and mental health conditions in the general medical population (25). The negative impact of the combination of depression and painful medical conditions has been shown in rheumatoid arthritis and in sickle cell disease (26-27), which may be relevant to the additive decrement in reported HRQOL from antidepressant usage observed in this study. A negative impact of asthma was expected given recent positive associations between asthma and painful episodes in children (18, 19) and mortality in adults (20). The occurrence of AVN had only a weak additive detrimental effect on HRQOL in these regression models, likely because of the close association of this complication with vaso-occlusive pain (21), and the inclusion of chronic opioid usage in the models.

This study utilized a large contemporary adult SCD cohort that provided an opportunity to examine the relationship between clinical events and patient-reported quality of life. Most older individuals in this cohort, or those who regularly took oral opioid analgesics, rated their general health as either fair or poor, and many individuals reported their general health as worse than in the previous year. The majority of patients in this cohort experienced multiple disease-related complications with older individuals experiencing a greater number of complications. However, the occurrence of only a few specific complications progressively diminished SF-36 scale scores, including vaso-occlusive crisis, associated conditions such as asthma, and the chronic usage of oral opioids or antidepressants, indicative of chronic pain and depression. While the large number of concurrent complications underscores the medical complexity of this disorder in adults, from the patient’s perspective the occurrence of acute and chronic pain impairs health status and quality of life more than any other disease-related complication. Our study suggests that more effective management of persistent pain and depression could substantially improve the quality of life for many adults with SCD. Unfortunately, persistent pain is a very complex phenomenon in this disorder (6), and more studies are needed to demonstrate effective management strategies.

A number of limitations of this study should be noted. Non-English speaking participants were not included. Since most clinical sites did not have reliable patient registries, a random subject enrollment design was not employed. Subject selection could be biased toward more symptomatic individuals as recruitment was targeted to those individuals frequently seen at their centers, as this population was believed most likely to return for subsequent studies. It is not possible to determine if the clinical severity documented in this cohort is representative of the wider SCD population or those of other sickle cell centers as there are no contemporary population based SCD cohorts available for comparison.

METHODS

Adult patients (age ≥ 18 years) with any form of SCD at participating CSCC Centers and affiliate sites were eligible for C-Data Project enrollment if seen within the last 24 months and expected to return for care. Subject enrollment occurred either at the time of a special C-Data Project recruitment event or at a routine clinic visit. Nine CSCC centers, representing 19 clinical sites, participated in the C-Data Project. At the time of initial enrollment, study staff collected a detailed health history (Medical History I) and administered psychosocial and health behavior interviews (Medical History II) that required approximately 10 minutes to complete. The health history data on medical conditions, SCD complications, surgeries, medication usage, procedures, and medical tests were subsequently verified by medical record review. Only medical history data verified by medical records was used in this study. The SF-36™ version 2 was self-administered in accordance with the provided guidelines and interview “script”. Subjects with limited literacy had the questions read to them. Non-English versions were not used in this study. Scores were calculated using the version 2 scoring algorithm for each of the eight SF36 dimensions, which norms the scale scores to data from the US general population to a mean of 50 with a standard deviation of 10 for each scale.

Only those subjects with complete informed consent, baseline data (Medical History I and II), and SF36 were included in the analysis for this manuscript. Statistical analyses for this manuscript were generated using SAS/STAT® software, Version 9.1 of the SAS System for Windows (Cary, NC). In addition to reporting summary statistics on the baseline and demographic variables, the hypothesis that age, gender and phenotype had no relationship to the number of complications was examined using an F-test from a linear model of the number of complications, controlling for age, gender, and phenotype. A linear model was fit to each SF-36 subscale with age group as a covariate. Descriptive p-values were generated from the F-test. The relationship between complications and the SF-36 subscales was examined by first eliminating complications (from the 19 selected complications in the C-Data database) that did not show a strong association using Cartesian and regression trees (CART). (28). Multivariable models (ordinal logistic and linear models) were created using only the subset of variables that had a descriptive p-value of >0.05 for any of the trees. An ordinal logistic model was used to examine the relationship between the SF-36 general health scale (5 points) and the SF-36 change in perceived health scale (5 points) controlling for age, gender, phenotype, antidepressant use, use of opioid analgesics, and the presence of AVN, ulcers, vaso-occlusive crisis (VOC), or asthma. The relationship between each SF-36 subscale and age, gender, phenotype, antidepressant use, use of opioid analgesics, and the presence of AVN, ulcers, VOC, or asthma was estimated using an F-test from a linear model.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Role of Funding Source The C-Data Project was supported by the NHLBI, Award Number U54HL070587. Protocol design, study conduct, data analysis, and the manuscript content were solely the responsibility of the investigators and authors, and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NHLBI or the National Institutes of Health.

Protocol Team The C-Data Protocol Team included: Susan Lieff, PhD; Karen Kesler, PhD; Zora Rogers, MD; Carlton Dampier, MD; Winfred Wang, MD; Cage Johnson, MD; George Buchanan, MD; Kwaku Ohene-Frempong, MD; Samir Ballas, MD; and Matthew Heeney, MD.

Statistical and Data Coordinating Center Rho Federal Systems of Rho, Inc. provided planning and organizational support for this study including protocol development and the full range of clinical, epidemiologic, data management, and statistical activities.

Regulatory Review The protocol was approved by a peer review Protocol Review Committee, and monitored by a Data Safety Monitoring Board, appointed by NHLBI. The study was also approved by the local Institutional Review Boards at each of the CSCC CTC clinical sites.

Collaborating Institutions The C-Data Project was a collaboration of the following institutions, investigators, and study coordinators. Site principal investigators are indicated by asterisks.

Boston Medical Center, Boston, MA—Lillian McMahon, MD*, Asif Qureshi, Shafat Quadri; Children’s Hospital of Boston, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, MA—Matthew Heeney, MD*, Tiffany Kang, Amber Smith; Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, MA—Maureen Okam, MD*, Ainsley Ross, Carole Tremonti; Montefiore Medical Center, Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Bronx, NY—Lennette Benjamin, MD*, Gwendolyn Swinson, Arlette Paul; Children’s Hospital at Montefiore, Bronx, NY—Catherine Driscoll, MD*; The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, Philadelphia, PA—Kim Smith-Whitley, MD*, Henrietta Enninful-Eghan, Tannoa Jackson; Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, Cincinnati, OH—Karen Kalinyak, MD*, Tammy Nordheim, Marlene Eaton; Duke University Medical Center, Durham, NC—Laura DeCastro, MD*, Michael Armstrong, MD*, Jude Jonassaint, Christle Cameron, Amanda Mandy; University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC—Kenneth Ataga, MD*, Ruth Baldwin, Perrior Anderson; Drexel University College of Medicine, St. Christopher’s Hospital for Children, Philadelphia, PA—Carlton Dampier, MD*, Camille Coleman; Cardeza Foundation for Hematologic Research, Thomas Jefferson University, Philadelphia, PA—Samir Ballas, MD*, April Deoria, Carol Wexler; University of Louisville, Louisville, KY—Ashok Raj, MD*, Salvatore Bertolone, MD, Claudia Grandinetti; Children’s Hospital and Research Center Oakland, Oakland, CA—Elliott Vichinsky, MD*, Christine Hoehner, Susan Paulukonis; University of Miami, Miami, FL—Ofelia Alvarez, MD*, Patricia Williams, Mary Donovan; University of California, San Francisco, San Francisco, CA—James Huang, MD*, Laura Quill, Jonah Todd-Geddes; St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital, Memphis, TN—Winfred Wang, MD*, Karen Winton, Lynn Wynn; University of Texas Southwestern, Dallas, TX—Zora Rogers, MD*, Cynthia Rutherford, MD*, Leah Adix, Nancy Lee; University of Oklahoma Health Sciences, Oklahoma City, OK—Joan Parkhurst Cain, MD*, Christina Gonzalez, Annette Johnson; University of Texas Medical Branch, Galveston, TX—David Bessman, MD*, Lisa Hernandez Garcia, Phyllis Crawford.

References

- 1.Valderas JM, Starfield B, Sibbald B, Salisbury C, Roland M. Defining comorbidity: implications for understanding health and health services. Ann Fam Med. 2009;7:357–363. doi: 10.1370/afm.983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Smith SM, O’Dowd T. Chronic diseases: what happens when they come in multiples? Br J Gen Pract. 2007;57:268–270. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fortin M, Bravo G, Hudon C, Lapointe L, Almirall J, Dubois MF, Vanasse A. Relationship between multimorbidity and health-related quality of life of patients in primary care. Qual Life Res. 2006;15:83–91. doi: 10.1007/s11136-005-8661-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rijken M, van Kerkhof M, Dekker J, Schellevis FG. Comorbidity of chronic diseases: effects of disease pairs on physical and mental functioning. Qual Life Res. 2005;14:45–55. doi: 10.1007/s11136-004-0616-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Saarni SI, Suvisaari J, Sintonen H, Koskinen S, Harkanen T, Lonnqvist J. The health-related quality-of-life impact of chronic conditions varied with age in general population. J Clin Epidemiol. 2007;60:1288–1297. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2007.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fenn HH, Bauer MS, Altshuler L, Evans DR, Williford WO, Kilbourne AM, Beresford TP, Kirk G, Stedman M, Fiore L. Medical comorbidity and health-related quality of life in bipolar disorder across the adult age span. J Affect Disord. 2005;86:47–60. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2004.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sareen J, Jacobi F, Cox BJ, Belik SL, Clara I, Stein MB. Disability and poor quality of life associated with comorbid anxiety disorders and physical conditions. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:2109–2116. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.19.2109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shih M, Simon PA. Health-related quality of life among adults with serious psychological distress and chronic medical conditions. Qual Life Res. 2008;17:521–528. doi: 10.1007/s11136-008-9330-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gaston M, Rosse WF. THE COOPERATIVE STUDY OF SICKLE-CELL DISEASE - REVIEW OF STUDY DESIGN AND OBJECTIVES. American Journal of Pediatric Hematology Oncology. 1982;4:197–201. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barakat LP, Patterson CA, Daniel LC, Dampier C. Quality of life among adolescents with sickle cell disease: mediation of pain by internalizing symptoms and parenting stress. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2008;6:60. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-6-60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brandow AM, Brousseau DC, Pajewski NM, Panepinto JA. Vaso-occlusive painful events in sickle cell disease: impact on child well-being. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2010;54:92–97. doi: 10.1002/pbc.22222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McClish DK, Penberthy LT, Bovbjerg VE, Roberts JD, Aisiku IP, Levenson JL, Roseff SD, Smith WR. Health related quality of life in sickle cell patients: the PiSCES project. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2005;3:50. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-3-50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Panepinto JA, O’Mahar KM, DeBaun MR, Loberiza FR, Scott JP. Health-related quality of life in children with sickle cell disease: child and parent perception. Br J Haematol. 2005;130:437–444. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2005.05622.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ballas SK, Lieff S, Benjamin LJ, Dampier CD, Heeney MM, Hoppe C, Johnson CS, Rogers ZR, Smith-Whitley K, Wang WC, Telen MJ. Definitions of the phenotypic manifestations of sickle cell disease. Am J Hematol. 2010;85:6–13. doi: 10.1002/ajh.21550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Powars DR, Hiti A, Ramicone E, Johnson C, Chan L. Outcome in hemoglobin SC disease: a four-decade observational study of clinical, hematologic, and genetic factors. Am J Hematol. 2002;70:206–215. doi: 10.1002/ajh.10140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Platt OS, Brambilla DJ, Rosse WF, Milner PF, Castro O, Steinberg MH, Klug PP. Mortality in sickle cell disease. Life expectancy and risk factors for early death. N Engl J Med. 1994;330:1639–1644. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199406093302303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ware JE, Jr., Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care. 1992;30:473–483. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Morris CR. Asthma management: reinventing the wheel in sickle cell disease. American Journal of Hematology. 2009;84:234–241. doi: 10.1002/ajh.21359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Boyd JH, Macklin EA, Strunk RC, DeBaun MR. Asthma is associated with acute chest syndrome and pain in children with sickle cell anemia. Blood. 2006;108:2923–2927. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-01-011072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Boyd JH, Macklin EA, Strunk RC, DeBaun MR. Asthma is associated with increased mortality in individuals with sickle cell anemia. Haematologica. 2007;92:1115–1118. doi: 10.3324/haematol.11213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kato GJ, Gladwin MT, Steinberg MH. Deconstructing sickle cell disease: reappraisal of the role of hemolysis in the development of clinical subphenotypes. Blood Reviews. 2007;21:37–47. doi: 10.1016/j.blre.2006.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rupp I, Boshuizen HC, Jacobi CE, Dinant HJ, van den Bos G. Comorbidity in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: effect on health-related quality of life. J Rheumatol. 2004;31:58–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Palm O, Bernklev T, Moum B, Gran JT. Non-inflammatory joint pain in patients with inflammatory bowel disease is prevalent and has a significant impact on health related quality of life. J Rheumatol. 2005;32:1755–1759. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rosenfeld B, Breitbart W, McDonald MV, Passik SD, Thaler H, Portenoy RK. Pain in ambulatory AIDS patients. II: Impact of pain on psychological functioning and quality of life. Pain. 1996;68:323–328. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(96)03220-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Baune BT, Caniato RN, Arolt V, Berger K. The effects of dysthymic disorder on health-related quality of life and disability days in persons with comorbid medical conditions in the general population. Psychother Psychosom. 2009;78:161–166. doi: 10.1159/000206870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wolfe F, Michaud K. Predicting depression in rheumatoid arthritis: the signal importance of pain extent and fatigue, and comorbidity. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;61:667–673. doi: 10.1002/art.24428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Levenson JL, McClish DK, Dahman BA, Bovbjerg VE, de ACV, Penberthy LT, Aisiku IP, Roberts JD, Roseff SD, Smith WR. Depression and anxiety in adults with sickle cell disease: the PiSCES project. Psychosom Med. 2008;70:192–196. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e31815ff5c5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Breiman L. Classification and regression trees. Wadsworth International Group; Belmont, Calif.: 1984. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.