Abstract

A typical marine bacterial cell in coastal seawater contains only ∼200 molecules of mRNA, each of which lasts only a few minutes before being degraded. Such a surprisingly small and dynamic cellular mRNA reservoir has important implications for understanding the bacterium's responses to environmental signals, as well as for our ability to measure those responses. In this perspective, we review the available data on transcript dynamics in environmental bacteria, and then consider the consequences of a small and transient mRNA inventory for functional metagenomic studies of microbial communities.

Keywords: mRNA, metatranscriptomics, macromolecules, bacteria

mRNA content of bacterial cells

Classic microbiological studies of the composition of exponentially growing Escherichia coli concluded that each cell harbors ∼1380 mRNA molecules (Neidhardt, 1996), a small number compared with other macromolecule inventories (that is, >3000 genes and >2 000 000 proteins). Similarly, recent single-molecule detection in individual E. coli cells based on high-resolution fluorescence detection of tagged mRNAs determined that the number of transcripts per gene per cell averaged only 0.4 (range: 0.02–3; see Supplementary Table S6 in Taniguchi et al., 2010). Assuming the 137 genes analyzed by this method are typical of the other ∼4400 genes (that is, those that were not tagged), each exponentially growing E. coli cell contains ∼1800 mRNA molecules, in good agreement with earlier work.

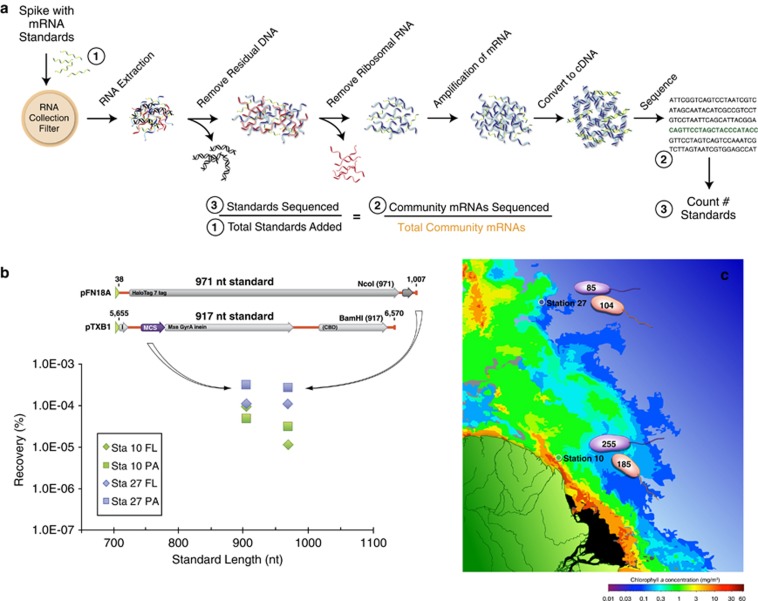

For bacterial cells in natural environments, methodological approaches to mRNA measurements that require laboratory cultures or genetic modifications are not feasible; many environmental taxa are not readily cultured and those that are would no longer reflect in situ macromolecule composition. Taking an alternate approach, we constructed artificial mRNA standards (Figure 1) and added them in known quantities to bacterioplankton communities at the initiation of RNA extraction (Gifford et al., 2011; Satinsky et al., in preparation). The extent to which the internal standards are diluted by natural mRNAs in high-throughput sequence libraries of the transcriptomes allows estimation of the number of mRNAs in the sampled community (Figure 1). In marine microbial communities from southeastern US coastal waters and the Amazon River plume, we estimated ∼200 mRNAs per cell (Table 1), a value less than for laboratory-grown cells (Table 1) but consistent with expectations for lower macromolecule inventories in environmental cells (Lee and Fuhrman, 1987; Simon and Azam, 1989; Schut et al., 1993).

Figure 1.

The use of internal standards (artificial mRNAs produced by in vitro transcription of vector templates) in metatranscriptomic studies allows calculation of average per-cell mRNA inventories. (a) A known number of internal standards are spiked into a microbial sample. In this example, 917 and 971 nt standards were added to a filter in an extraction tube containing lysis buffer just before initiating RNA extraction (see Gifford et al., 2011 for complete protocol). The ratio of standards added:standards recovered in the high-throughput sequence library allows estimation of the numbers of natural mRNAs in the sampled community. (b) Recovery ratio of internal standards in Illumina libraries from free-living (FL) and particle-associated (PA) metatranscriptomes from two locations in the Amazon River plume in May 2010. Standards were produced by reverse transcription from the T7 promoter (green arrowhead) of two linearized commercial cloning vectors (Promega, Fitchburg, WI, USA; New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA, USA). (c) Based on internal standard recovery in the mRNA library, the average number of transcripts per SYBR green-stained bacterial cell was calculated for the free-living (0.2 to <2 μm size range; purple cells) and particle-associated (>2 μm size range; orange cells) size fractions at two stations in the Amazon River plume. The total abundance of prokaryotic transcripts was 2.3 × 1011 l−1 at Station 27 and 8.5 × 1011 l−1 at Station 10. The background color is modified from a MODIS Aqua image of chlorophyll a concentrations.

Table 1. Estimates of per cell mRNA inventories for laboratory bacterial cultures (top) and natural marine bacteria (bottom).

| Cells | Method | Total RNA content (fg cell−1) | mRNAs cell−1 | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Laboratory studies | ||||

| Escherichia coli | Biochemical analysis | NA | 1380 | Neidhardt and Umbarger, 1996 |

| Escherichia coli | Single-cell microscopy | NA | 1800a | Taniguchi et al., 2010 |

| Vibrio alginolyticus | RNA recovery | 28 | 2288b | Kramer and Singleton, 1992 |

| Natural communities | ||||

| Coastal bacterioplankton, GA | Internal standard | NA | 142–238 | Gifford et al., 2011 |

| Bacterioplankton, Amazon Plume | Internal standard | NA | 85–255 | Satinsky et al., in preparation |

| Coastal bacterioplankton, GA | RNA recovery | 0.6–1.3 | 96–190b | Gifford et al., 2011 |

| Coastal bacterioplankton, NY | RNA recovery | 1.6–5.4 | 135–458b | Lee and Kemp, 1994 |

| Coastal bacterioplankton, CA | RNA recovery | 1.9–9.5 | 161–805b | Simon and Azam, 1989 |

Abbreviation: NA, not available.

Calculated by extrapolation from 137 genes (see text).

Calculated by assuming total RNA contains 4% mRNA by mass (Neidhardt and Umbarger, 1996) and bacterial mRNAs have an average length of 924 nucleotides (Xu et al., 2006) and therefore an average weight of 4.72 × 10−4 fg.

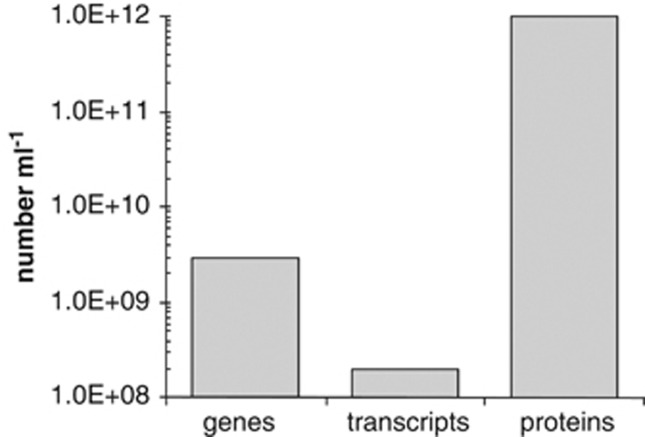

mRNA content of bacteria in natural environments can also be estimated based on the quantity of RNA recovered from a known number of cells. This calculation requires estimates of RNA extraction efficiency (we assumed 50%), the make-up of bacterial RNA (we assumed 4% mRNA by mass; Neidhardt and Umbarger, 1996), and the average length of a bacterial mRNA (we assumed 924 nt; Xu et al., 2006). By this method, bacterioplankton cells in various coastal environments have an average mRNA content of ∼300 molecules (Table 1), with calculations for freshwaters, soils and sediments likely to be similar. Thus, several lines of evidence suggest that bacterial communities in nature maintain a considerably lower inventory of transcripts compared with genes and proteins (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Bacterioplankton macromolecule inventories in a milliliter of typical coastal seawater. Bacterial mRNAs are an order of magnitude less abundant than genes, and almost four orders of magnitude less abundant than proteins.

mRNA half-life

Various measures of global half-lives of mRNA in laboratory-grown E. coli cells converge at about 5 min (range: ∼1–8 min; Ingraham et al., 1983; Bernstein et al., 2002; Selinger et al., 2003; Taniguchi et al., 2010). For Bacillus subtilis, the average half-life of mRNA has also been estimated at ∼5 min (Hambraeus et al., 2003), and that of laboratory-grown marine cyanobacterium Prochlorococcus MED4 mRNA at 2.4 min (Steglich et al., 2010). Half-lives of mRNAs appear to be independent of cell growth rate (Bernstein et al., 2002; Dennis and Bremer, 1974), and consequently lifetimes should be similarly short for environmental cells (Steglich et al., 2010). Even in the case of cells in extreme environments with very slow growth rates (Price and Sowers, 2004; Jørgensen, 2011), mRNA half-life will likely be short with respect to the timescale of environmental changes.

Response of mRNA levels to environmental cues

This bacterial ‘just-in-time' management strategy for mRNAs (low inventories, rapid turnover) is tremendously powerful for indicating near-real-time conditions experienced by cells, information that is not possible to extract from gene inventories. For example, bacterial mRNA pools have provided assays of the bioreactive components of dissolved organic carbon pools based on transcriptome changes in amended seawater (McCarren et al., 2010; Poretsky et al., 2010; Shi et al., 2012); identified bacterial degradation pathways based on shifts in mRNA composition with increased substrate concentrations (Vila-Costa et al., 2010); characterized short-term reactions to altered CO2 (Gilbert et al., 2008) and pollutant concentrations (de Menezes et al., 2012); and revealed niche differentiation among co-occurring autotrophs (Liu et al., 2012) and heterotrophs (Gifford et al., 2012). Changes in transcript inventories provide a sensitive window into the fluctuating cues perceived by microbes in their environment, and therefore the signals that drive changes in ecosystem function.

Correlation between mRNA and protein abundance in a single cell

If mRNA levels consistently predicted protein levels, then metatranscriptomic data would also be useful for another critical challenge in microbial ecology: to estimate rates of biogeochemically important transformations. Yet systems biologists realized a number of years ago that there is surprisingly little correlation between abundance of a protein in a cell and abundance of the transcript that mediates its synthesis. In the single-cell study of fluorescently tagged E. coli strains mentioned above (Taniguchi et al., 2010), the correlation coefficient between per cell mRNA and protein levels of the same gene averaged zero for the genes tested. There are various reasons for a poor relationship between single-cell mRNAs and protein abundance, including post-transcriptional processing and regulation (Maier et al., 2009), random fluctuations in low-copy mRNAs (Kaufmann and van Oudenaarden, 2007), uneven partitioning of macromolecules during cell division (Golding et al., 2005) and variable translation efficiencies (that is, the number of completed proteins per mRNA per time; Maier et al., 2009). However, the most important factor responsible for poor mRNA–protein correlations is the long half-life of proteins relative to mRNAs. A typical bacterial protein half-life is ∼20 h (Koch and Levy, 1955; Mandelstam, 1957; Borek et al., 1958), which is about two orders of magnitude longer than an mRNA half-life. Thus, most proteins persist in a bacterial cell long after the mRNAs that encoded them have been degraded.

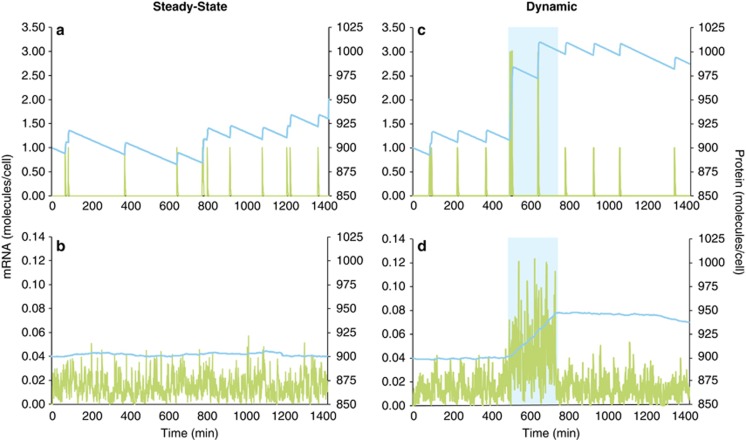

Correlation between mRNA and protein abundance in a population

Despite the poor correlations between single-cell mRNA and protein abundances observed by Taniguchi et al. (2010), their data coalesced into a predictable relationship when averaged across many cells growing under steady-state conditions; that is, the population mean of mRNA copies successfully predicted the population mean of proteins when the cells were under constant growth conditions. In a gross sense, the universal mechanism of protein production from mRNA requires a correlation between the two when abundances are integrated over time or space. Measures of mRNA and protein relationships in natural bacterial populations are similarly averaged across a population, which should smooth out variation at the single-cell level to a consistent relationship for a given gene under steady-state conditions. A basic simulation model of macromolecule inventories (Supplementary Materials) that compares a single cell to a population of cells in a constant environment bears this out. Although the model shows it is not possible to predict protein levels from mRNA levels in just one cell (Figure 3a; simulated protein and mRNA half-lives are 12 h and 1.5 min, respectively), the ratio between the two is consistent at the population level, even for a population as small as 100 cells (Figure 3b).

Figure 3.

Simulation model of levels of mRNA (green lines) and protein (blue lines) of the same gene in a single cell (a, c) or averaged for a population of 100 cells (b, d) during a 24-h period. In the steady-state version of the model (a, b), which could represent either constitutive gene expression or an unchanging extrinsic regulatory signal, each cell experiences up to 10 randomly timed transcription events per day and produces a single mRNA molecule at each event (Supplementary Materials). In the dynamic version (c, d), extrinsic signaling upregulates gene transcription for a 4-h period (500–740 min; blue shading) through an increase in transcriptional burst size to three mRNA molecules per transcription event. Both model types were initialized with 900 protein molecules per cell, and both assume 7 proteins are translated from each mRNA template, that the half-life of mRNA is 1.5 min, and that the half-life of protein is 12 h. Varying the parameter values (for example, frequency of transcription events, mRNA burst size, proteins translated per message, macromolecule half-lives) changes the size of the final mRNA and protein pools, but they remain poorly synchronized under dynamic extrinsic conditions.

However, if a shift in environmental conditions (for example, a nutrient pulse) triggers a change in gene transcription rates, the population-wide relationship is quickly disrupted because of the mismatched half-lives of mRNA and proteins (Figures 3c and d). mRNA inventories respond sensitively to both the beginning and end of the environmental signal because they are short-lived relative to its duration. Relative shifts in protein inventories are slow, however, both because proteins are long-lived and because their high standing stocks (reaching into the thousands for the protein product of a single gene in one cell) make them less responsive. Thus, the ratio between mRNA and protein is variable and, importantly, not reflective of instantaneous conditions experienced by the cell. Such non-steady-state situations are likely to be common in the ocean, for example, the strong 24-h rhythm imposed by solar energy inputs and the shorter-lived variations in dissolved organic carbon concentrations around particles and cells (Fenchel, 2002; Azam and Malfatti, 2007; Stocker et al., 2008). This mismatch between mRNA and protein dynamics can be partially ameliorated by targeted protein degradation when an environmental signal dissipates, or by proteins with an atypically short half-life (for example, 1 h for AraC in E. coli or 19 min for photosystem protein D1 in Synechocystis PCC 6803; Kolodrubetz and Schleif, 1981; Tyystjärvi et al., 1994). Nonetheless, the conditions under which mRNA abundance is a strict proxy for protein abundance in a dynamic ocean may be rare for regulated genes (Figure 3).

Similar arguments can be made regarding the assumption that protein abundance is a reliable proxy for cellular rates, as post-translational regulation of protein activity and concentration of substrate both strongly affect catalysis rates. For instance, expression of bacterial enzymes can be constitutive and therefore unlinked to environmental signals (for example, proteorhodopsin in marine Flavobacteria and SAR11, and DMSP lyases in marine roseobacters; Curson et al., 2008; Riedel et al., 2010; Steindler et al., 2011); induced proteins may outlive the resources they were synthesized to exploit (for example, in microscale substrate patches or plumes that dissipate in within minutes; Stocker et al., 2008); and proteins expressed in response to a scarcity may actually be most abundant when reaction rates are lowest (for example, ammonium or phosphate transporters during nutrient starvation; Gyaneshwar et al., 2005; Sowell et al., 2009). Even for pure cultures growing under laboratory conditions, systems biology-based analyses typically show that protein levels cannot be readily correlated with metabolic flux (Ovacik and Androulakis, 2008).

All in all, a large number of factors confound simple relationships between mRNA and protein as well as between protein and transformation rates for most bacterial genes at any given time. The inefficiencies that likely stem from these mismatches may be part of the overhead of responding quickly to environmental change. Interestingly, one of the key differences proposed to distinguish ‘copiotrophic' versus ‘oligotrophic' marine bacterioplankton is the ability to react to environmental variation (Giovannoni et al., 2005; Lauro et al., 2009). Presumably, the trade-off between the ability to benefit from a transient substrate on the one hand, versus maintaining a protein that has outlived its usefulness on the other, is at least one element of the evolutionary fine tuning of bacterial regulation.

The prognosis for metatranscriptomics

The integration of diverse molecular-level processes to predict system-level phenotypes is a unifying challenge in modern biology, with the system of interest ranging from a bacterium to an entire ecosystem. In the field of marine microbial ecology, it is anticipated that amassing of ‘meta-omics' data sets will bring insights into the interaction networks underpinning biogeochemically relevant processes (Doney et al., 2004; Raes and Bork, 2008). In turn, this will build better predictions of system behavior in the context of changing global climate and increasing human perturbations. Our appraisal of the inherent challenges of community mRNA analysis does not in any way diminish its value as a tool in these important efforts. Instead, we argue for identifying the most powerful and appropriate use of the technology. Sizing up the potential for a small yet dynamic metatranscriptome to contribute to the important goals of ‘eco-systems' biology leads to four key observations: (1) the abundance of mRNAs from functional genes is not a reliable rate proxy for those functions in naturally fluctuating environments, and neither is the abundance of proteins; (2) instantaneous inventories of mRNA pools are nonetheless highly informative about ongoing ecologically relevant processes; (3) fluctuations in mRNAs pools provide a highly sensitive bioassay for environmental signals that are relevant to microbes; and (4) replicated, manipulative experiments fully leverage the value of metatranscriptomes for revealing the microbes that perceive a specific environmental change and the metabolic pathways they invoke to respond to it.

Acknowledgments

We thank C English for graphics support. This project was supported by funding from the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation (Marine Microbiology Investigator and River Ocean Continuum of the Amazon Awards), and National Science Foundation grants MCB-0702125 and MCB-1129326.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Supplementary Information accompanies the paper on The ISME Journal website (http://www.nature.com/ismej)

Supplementary Material

References

- Azam F, Malfatti F. Microbial structuring of marine ecosystems. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2007;5:966–966. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein JA, Khodursky AB, Lin P-H, Lin-Chao S, Cohen SN. Global analysis of mRNA decay and abundance in Escherichia coli at single-gene resolution using two-color fluorescent DNA microarrays. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:9697–9702. doi: 10.1073/pnas.112318199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borek E, Ponticorvo L, Rittenberg D. Protein turnover in microorganisms. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1958;44:369–374. doi: 10.1073/pnas.44.5.369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curson ARJ, Rogers R, Todd JD, Brearley CA, Johnston AWB. Molecular genetic analysis of a dimethylsulfoniopropionate lyase that liberates the climate-changing gas dimethylsulfide in several marine a-proteobacteria and Rhodobacter sphaeroides. Environ Microbiol. 2008;10:757–767. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2007.01499.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Menezes A, Clipson N, Doyle E.2012Comparative metatranscriptomics reveals widespread community responses during phenanthrene degradation in soil Environ Microbiole-pub ahead of print;doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2012.02781.x [DOI] [PubMed]

- Dennis PP, Bremer H. Macromolecular composition during steady-state growth of Escherichia coli B/r. J Bact. 1974;119:270–281. doi: 10.1128/jb.119.1.270-281.1974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doney SC, Abbott MR, Cullen JJ, Karl DM, Rothstein L. From genes to ecosystems: the ocean's new frontier. Front Ecol Environ. 2004;2:457–468. [Google Scholar]

- Fenchel T. Microbial behavior in a heterogeneous world. Science. 2002;296:1068–1071. doi: 10.1126/science.1070118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gifford SM, Sharma S, Booth M, Moran MA.2012Expression patterns reveal niche diversification in a marine microbial assemblage ISME J(in press). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Gifford SM, Sharma S, Rinta-Kanto JM, Moran M. Quantitative analysis of a deeply-sequenced marine microbial metatranscriptome. ISME J. 2011;5:461–472. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2010.141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert JA, Field D, Huang Y, Edwards R, Li W, Gilna P, et al. Detection of large numbers of novel sequences in the metatranscriptomes of complex marine microbial communities. PLoS One. 2008;3:e3042. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giovannoni SJ, Tripp HJ, Givan S, Podar M, Vergin KL, Baptista D, et al. Genome streamlining in a cosmopolitan oceanic bacterium. Science. 2005;309:1242–1245. doi: 10.1126/science.1114057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golding I, Paulsson J, Zawilski SM, Cox EC. Real-time kinetics of gene activity in individual bacteria. Cell. 2005;123:1025–1036. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.09.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gyaneshwar P, Paliy O, McAuliffe J, Popham DL, Jordan MI, Kustu S. Sulfur and nitrogen limitation in Escherichia coli K-12: specific homeostatic responses. J Bacteriol. 2005;187:1074–1090. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.3.1074-1090.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hambraeus G, von Wachefeldt C, Hederstedt L. Genome-wide survey of mRNA half-lives in Bacillus subtilis identifies extremely stable mRNAs. Mol Gen Genomics. 2003;269:706–714. doi: 10.1007/s00438-003-0883-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingraham JL, Maaløe O, Neidhardt FC. The Growth of the Bacterial Cell. Sinauer Associates: Sunderland, MA; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Jørgensen BB. Deep subseafloor microbial cells on physiological standby. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:18193–18194. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1115421108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufmann BB, van Oudenaarden A. Stochastic gene expression: from single molecules to the proteome. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2007;17:107–112. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2007.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koch AL, Levy HR. Protein turnover in growing cultures of Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 1955;217:947–958. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolodrubetz D, Schleif R. Identification of AraC protein and two-dimensional gels, its in vivo instability and normal level. J Mol Biol. 1981;149:133–139. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(81)90265-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer JG, Singleton FL. Variations in rRNA content of marine Vibrio spp. during starvation-survival and recovery. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1992;58:201–207. doi: 10.1128/aem.58.1.201-207.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lauro FM, McDougald D, Williams TJ, Egan S, Rice S, DeMaere MZ, et al. A tale of two lifestyles: the genomic basis of trophic strategy in bacteria. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:15527–15533. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0903507106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S, Fuhrman JA. Relationships between biovolume and biomass of naturally derived marine bacterioplankton. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1987;53:1298–1303. doi: 10.1128/aem.53.6.1298-1303.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S, Kemp PF. Single-cell RNA content of natural marine planktonic bacteria measured by hybridization with multiple 16S rRNA-targeted fluorescent probes. Limnol Oceanogr. 1994;39:869–879. [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z, Klatt CG, Wood JM, Rusch DB, Ludwig M, Wittekindt N, et al. Metatranscriptomic analyses of chlorophototrophs of a hot-spring microbial mat. ISME J. 2012;5:1279–1290. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2011.37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maier T, Güell M, Serrano L. Correlation of mRNA and protein in complex biological samples. FEBS Lett. 2009;583:3966–3973. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2009.10.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandelstam J. Turnover of protein in growing and non-growing populations of Escherichia coli. Biochem J. 1957;6:110–119. doi: 10.1042/bj0690110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarren J, Becker JW, Repeta DJ, Shi Y, Young CR, Malmstrom RR, et al. Microbial community transcriptomes reveal microbes and metabolic pathways associated with dissolved organic matter turnover in the sea. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:16420–16427. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1010732107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neidhardt FC. Escherichia Coli and Salmonella: Cellular and Molecular Biology. ASM Press: Washington, DC; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Neidhardt FC, Umbarger HE.1996Chemical composition of Escherichia coliIn: Neidhardt FC, Curtiss R III, Ingraham JL, Lin ECC, Low KB, Magasanik B, Reznikoff WS, Riley M, Schaechter M, Umbarger HE (eds)Escherichia Coli and Salmonella Typhimurium: Cellular and Molecular Biology2nd edn.ASM Press: Washington, DC; 13–16. [Google Scholar]

- Ovacik MA, Androulakis IP. On the potential for integrating gene expression and metabolic flux data. Curr Bioinform. 2008;3:142–148. [Google Scholar]

- Poretsky RS, Sun S, Mou X, Moran M. Transporter genes expressed by coastal bacterioplankton in response to dissolved organic carbon. Environ Microbiol. 2010;12:616–627. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2009.02102.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price PB, Sowers T. Temperature dependence of metabolic rates for microbial growth, maintenance, and survival. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:4631–4636. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400522101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raes J, Bork P. Molecular eco-systems biology: towards an understanding of community function. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2008;6:693–699. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riedel T, Tomasch J, Buchholz I, Jacobs J, Kollenberg M, Gerdts G, et al. Constitutive expression of the proteorhodopsin gene by a flavobacterium strain representative of the proteorhodopsin-producing microbial community in the North Sea. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2010;76:3187–3197. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02971-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satinsky BM, Smith CB, Crump BC, Sharma S, Dougherty M, Fortunato C, et al. Taking stock of the meta-ome: microbial gene transcription ratios in the Amazon River Plume(in preparation).

- Schut F, De Vries EJ, Gottschal JC, Robertson BR, Harder W, Prins RA, et al. Isolation of typical marine bacteria by dilution culture: growth, maintenance, and characteristics of isolates under laboratory conditions. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1993;59:2150–2160. doi: 10.1128/aem.59.7.2150-2160.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selinger DW, Saxena RM, Cheung KJ, Church GM, Rosenow C. Global RNA half-life analysis in Escherichia coli reveals positional patterns of transcript degradation. Genome Res. 2003;13:216–223. doi: 10.1101/gr.912603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi Y, McCarren J, DeLong EF. Transcriptional responses of surface water marine microbial assemblages to deep-sea water amendment. Environ Microbiol. 2012;14:191–206. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2011.02598.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon M, Azam F. Protein content and protein synthesis rates of planktonic bacteria. Mar Ecol Prog Ser. 1989;51:201–213. [Google Scholar]

- Sowell SM, Wilhelm LJ, Norbeck AD, Lipton MS, Nicora CD, Barofsky DF, et al. Transport functions dominate the SAR11 metaproteome at low-nutrient extremes in the Sargasso Sea. ISME J. 2009;3:93–105. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2008.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steglich C, Lindell D, Futschik M, Rector T, Steen R, Chisholm SW. Short RNA half-lives in the slow-growing marine cyanobacterium Prochlorococcus. Genome Biol. 2010;11:R54. doi: 10.1186/gb-2010-11-5-r54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steindler L, Schwalbach MS, Smith DP, Chan F, Giovannoni SJ. Energy starved Candidatus Pelagibacter ubique substitutes light-mediated ATP production for endogenous carbon respiration. PLoS One. 2011;6:e19725. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0019725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stocker R, Seymour JR, Samadani A, Hunt DE, Polz MF. Rapid chemotactic response enables marine bacteria to exploit ephemeral microscale nutrient patches. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:4209–4214. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0709765105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taniguchi Y, Choi PJ, Li G-W, Chen H, Babu M, Hearn J, et al. Quantifying E. coli proteome and transcriptome with single-molecule sensitivity in single cells. Science. 2010;329:533–538. doi: 10.1126/science.1188308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyystjärvi T, Aro EM, Jansson C, Mäenpää. Changes of amino acid sequence in PEST-like area and QEEET motif affect degradation rate of D1 polypeptide in photosystem II. Plant Mol Biol. 1994;25:517–526. doi: 10.1007/BF00043879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vila-Costa M, Rinta-Kanto JM, Sun S, Sharma S, Poretsky R, Moran MA. Transcriptomic analysis of a marine bacterial community enriched with dimethylsulfoniopropionate. ISME J. 2010;4:1410–1420. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2010.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu L, Chen H, Hu X, Zhang R, Zhang Z, Luo ZW. Average gene length is highly conserved in prokaryotes and eukaryotes and diverges only between the two kingdoms. Mol Biol Evol. 2006;23:1107–1108. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msk019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.