Abstract

Background

One of the consequences of climate change is the increased frequency and intensity of heat waves which can cause serious health impacts. In Québec, July 2010 was marked by an unprecedented heat wave in recent history. The purpose of this study is to estimate certain health impacts of this heat wave.

Methods

The crude daily death and emergency department admission rates during the heat wave were analyzed in relation to comparison periods using 95% confidence intervals.

Results

During the heat wave, the crude daily rates showed a significant increase of 33% for deaths and 4% for emergency department admissions in relation to comparison periods. No displacement of mortality was observed over a 60-day horizon.

Conclusions

The all-cause death indicator seems to be sufficiently sensitive and specific for surveillance of exceedences of critical temperature thresholds, which makes it useful for a heat health-watch system. Many public health actions combined with the increased use of air conditioning in recent decades have contributed to a marked reduction in mortality during heat waves. However, an important residual risk remains, which needs to be more vigorously addressed by public health authorities in light of the expected increase in the frequency and severity of heat waves and the aging of the population.

Background

One of the most indisputable consequences of climate change is the increased frequency and intensity of heat waves [1]. A heat wave can have particularly serious health impacts, even in the context of developed countries. In three weeks, the number of deaths due to the 2003 heat wave in eight European countries was close to 35,000 people [2]. In the United States, the heat wave that hit California for two weeks in 2006 led to an excess of at least 140 deaths, but also 16,166 emergency department admissions and 1,182 hospitalizations [3]. In Canada, 2010 was the hottest year and summer ever recorded in 63 years of meteorological observations [4]. For Ontario and Québec, July 2010 was marked by an unprecedented heat wave from July 4th to 9th, with maximum temperatures reaching 30°C or more, minimum temperatures above 20°C, and high humidity. The purpose of this study is to estimate certain health impacts of the July 2010 heat wave in Québec. More precisely, this study describes the number of deaths and emergency room admissions related to the heat wave, and discusses how this could be explained compared to previous similar episodes.

Methods

Sources of data

The meteorological data are from Environment Canada. In this study, they include the minimum and maximum daily temperatures observed at the reference weather stations located within health regions (HRs). A reference station is a station considered as representative of a given region by Environment Canada [5]. The number of deaths (all causes) was extracted from three databases of the Institut de la Statistique du Québec: daily files (2010), provisional files (2008–2009), and final files (2005–2007); provisional files are usually quite similar to final files except for a few changes in final cause of death (no impact for this study as all-cause is used) and the addition of deaths occurring out of province, which could result in a very slight underestimation of the daily death rates here. In the daily files database, age is available only according to three strata: < 65, 65–74, and > 74. The number of emergency department admissions (all causes) comes from the Relevé quotidien de la situation dans les urgences et les centres hospitaliers (RQSUCH, daily report of the situation in emergency departments and hospitals) of the ministère de la Santé et des Services sociaux du Québec (Quebec ministry of Health and Social Services), just like the population numbers taken from demographic projections [6]. All data used in this study is openly available.

Analysis periods

The heat wave period has been defined as the days in July 2010 when the moving averages (over three days) of the minimum and maximum temperatures of the HRs were equal to or exceeded certain predefined thresholds (Table 1). These thresholds, established previously [5,7] in 16 of the 18 HRs of Québec, were defined in such a way as to predict the hot periods that could produce significant excesses in fatalities of 60% or more, compared to the 1981–2005 historical daily average. The level of 60% was used because of the low number of daily deaths in historical data per HR, in order to increase the statistical stability of thresholds and decrease the number of false alerts in forecasts.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the heat wave, by health region (HR)

|

HR |

Date of start |

Total duration (days) |

Maximum temperatures |

Minimum temperatures |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |

|

|

Thresholds (°C) |

Highest |

Thresholds (°C) |

Highest |

||

| °C | Number of days after the start | °C | Number of days after the start | |||||

| Capitale-Nationale |

05/07 |

5 |

31.0 |

33.4 |

2 |

16.0 |

21.0 |

1 |

| Chaudière-Appalaches |

05/07 |

5 |

31.0 |

33.5 |

2 |

16.0 |

21.2 |

3 |

| Estrie |

05/07 |

5 |

31.0 |

33.3 |

3 |

18.0 |

22.2 |

3 |

| Lanaudière |

05/07 |

5 |

33.0 |

34.8 |

3 |

20.0 |

22.8 |

2 |

| Laval |

05/07 |

4 |

33.0 |

33.7 |

3 |

20.0 |

25.5 |

1 |

| Montérégie |

05/07 |

4 |

33.0 |

34.7 |

3 |

20.0 |

24.0 |

1 |

| Montréal |

05/07 |

4 |

33.0 |

33.7 |

3 |

20.0 |

25.5 |

1 |

| Outaouais | 04/07 | 5 | 31.0 | 34.3 | 4 | 18.0 | 20.3 | 2 |

To estimate the health impacts, the period of interest corresponded to the heat wave plus the following three days (hereafter called the impact period). The three days are added to take into account the delayed effects of heat on health and are based on the known duration of the impacts of heat on all-cause mortality [8-12]. To evaluate a potential mortality displacement (also known as harvesting effect), the total mortality in the 60 days (without a heat wave) after the impact period was also studied. The comparison periods met the following criteria: 1) corresponded to the same days of the week during the years 2005, 2006, 2007, 2008, and 2009; 2) corresponded to the dates closest to the 2010 impact period; and 3) did not include any heat wave.

Statistical analyses

The crude death and emergency department admission rates for the impact period were analyzed in relation to the comparison periods using 95% confidence intervals [13]. Since the crude rate follows a Poisson distribution, the method used to calculate confidence intervals for crude rate is the normal approximation of the natural logarithm of the rate [14].

Results

Characteristics of the heat wave

In July 2010, eight of the 18 HRs of Québec experienced a heat wave lasting an average of 4.6 days (range: 4 to 5 days). The highest maximum temperatures varied from 33.3 to 34.8°C and were observed for 2.9 days on average (range: 2 to 4 days) after the start of the heat wave, whereas the highest minimum temperatures fluctuated between 20.3 and 25.5°C and were observed for 1.8 days on average (range: 1 to 3 days) after the start (Table 1). These values, just like the averages, were clearly higher in July 2010 (compared to 2005–2009) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Average temperatures during the heat wave (2010) and the comparison periods (2005–2009), by health region (HR)

|

HR |

Maximum temperatures (°C) |

Minimum temperatures (°C) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2010 | 2005-2009 | 2010 | 2005-2009 | |

| Capitale-Nationale |

32.3 |

24.0 |

19.7 |

12.8 |

| Chaudière-Appalaches |

32.1 |

23.6 |

19.8 |

11.2 |

| Estrie |

32.3 |

24.8 |

21.0 |

12.5 |

| Lanaudière |

33.6 |

25.3 |

21.2 |

13.6 |

| Laval |

33.4 |

24.8 |

24.0 |

15.8 |

| Montérégie |

34.0 |

24.7 |

21.6 |

14.0 |

| Montréal |

33.4 |

24.8 |

24.0 |

15.8 |

| Outaouais | 33.1 | 23.9 | 18.5 | 12.4 |

Health impacts

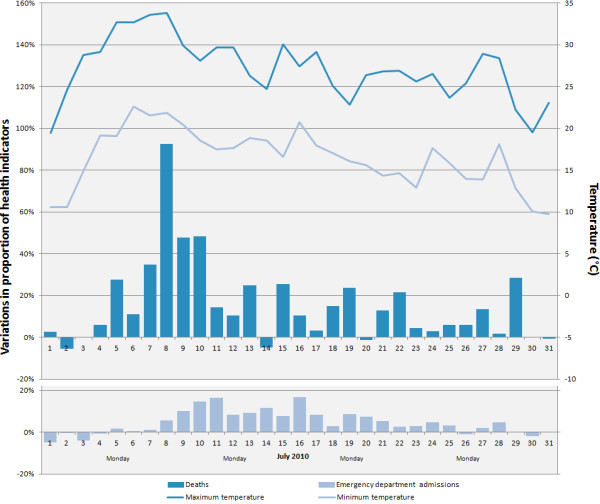

Collectively, the eight HRs affected by the heat wave (approximately six million people) showed a significant increase of 33% in the crude death rate (about 280 extra deaths) and 4% in the crude emergency department admission rate (about 3400 extra admissions), compared to 2005–2009 (Table 3). The 2010 crude rates by age group showed a significant increase of about 33% compared to 2005–2009 for the 0–64 year and 75 year or older group; the 65–74 year group showed a non-significant increase (Table 4). Four of the eight HRs (Capitale Nationale, Chaudière-Appalaches, Laval and Montréal) had higher emergency department admission rates, and three (Montréal, Montérégie and the Outaouais) had higher death rates (Table 3). The deaths show a 93% maximum daily increase on the fourth day of the heat wave, and the emergency department admissions, a 17% increase on the seventh day of the period (Figure 1).

Table 3.

Crude death and emergency department admission rates, by health region (HR) and study period

|

HR (population 2010) |

Period |

Deaths |

Emergency dept. admissions |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n* | Crude rates per 100,000 person-days (95% CI) | n* | Crude rates per 100,000 person-days (95% CI) | ||

| All HRs (5 985 001) |

2005-2009 |

760 |

1.77 (1.71–1.83) |

47 635 |

110.89 (110.45–111.34) |

| |

2010 |

1 039 |

2.35 (2.22–2.50) |

51 054 |

115.70 (114.70–116.70) |

| Capitale Nationale (687 950) |

2005-2009 |

107 |

1.98 (1.82–2.16) |

9 219 |

171.09 (169.54–172.66) |

| |

2010 |

114 |

2.07 (1.72–2.49) |

9 704 |

176.32 (172.85–179.86) |

| Chaudière-Appalaches (405 576) |

2005-2009 |

58 |

1.81 (1.61–2.03) |

3 676 |

115.17 (113.52–116.85) |

| |

2010 |

53 |

1.63 (1.25–2.14) |

5 058 |

155.89 (151.65–160.25) |

| Estrie (308 335) |

2005-2009 |

47 |

1.96 (1.72–2.22) |

4 032 |

166.45 (164.17–168.77) |

| |

2010 |

54 |

2.19 (1.68–2.86) |

4 080 |

165.40 (160.41–170.56) |

| Lanaudière (468 381) |

2005-2009 |

55 |

1.56 (1.39–1.76) |

2 308 |

65.24 (64.06–66.44) |

| |

2010 |

77 |

2.05 (1.64–2.57) |

2 425 |

64.72 (62.19–67.35) |

| Laval (396 186) |

2005-2009 |

42 |

1.58 (1.38–1.81) |

1 264 |

47.70 (46.54–48.89) |

| |

2010 |

62 |

2.24 (1.74–2.87) |

1 500 |

54.09 (51.42–56.89) |

| Montérégie (1 444 047) |

2005-2009 |

165 |

1.69 (1.58–1.81) |

7 889 |

80.65 (79.85–81.45) |

| |

2010 |

233 |

2.31 (2.03–2.62) |

8 299 |

82.10 (80.35–83.89) |

| Montréal (1 912 388) |

2005-2009 |

240 |

1.82 (1.72–1.93) |

15 498 |

117.50 (116.67–118.33) |

| |

2010 |

376 |

2.81 (2.54–3.11) |

16 233 |

121.19 (119.34–123.07) |

| Outaouais (362 138) |

2005-2009 |

46 |

1.63 (1.43–1.86) |

3 747 |

134.24 (132.33–136.17) |

| 2010 | 70 | 2.42 (1.91–3.05) | 3 765 | 129.96 (125.87–134.18) | |

The 2010 rates, statistically different from the comparison rates (2005–2009) based on the confidence intervals (CI), are shown in bold.

* Average numbers for the 2005–2009 period.

Table 4.

Crude death rates, by age and study period for all regions affected

|

Age group |

Period |

Deaths |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| n* | Crude rates per 100,000 person-days (95% CI) | ||

| 0-64 years |

2005-2009 |

178 |

0.49 (0.46–0.52) |

| |

2010 |

240 |

0.65 (0.58–0.74) |

| 65-74 years |

2005-2009 |

132 |

3.99 (3.70–4.31) |

| |

2010 |

160 |

4.40 (3.77–5.14) |

| 75+ years |

2005-2009 |

450 |

15.99 (15.34–16.66) |

| 2010 | 639 | 21.22 (19.64–22.93) | |

The 2010 rates, statistically different from the comparison rates (2005–2009) based on the confidence intervals (CI), are shown in bold.

* Average numbers for the 2005–2009 period.

Figure 1.

Evolution of daily variations in proportion of health indicators in all of the eight RSSs of Quebec affected by the heat waves from July 1st to 31st, 2010 versus the comparison periods (2005-2009) and daily averages of July 2010 temperatures.

Mortality displacement

Mortality displacement (or harvesting effect) could not be studied in three of the eight HRs affected by the July 2010 heat wave due to the presence of other heat episodes in the 60 days following the impact period. In the five other HRs (Lanaudière, Laval, Montérégie, Montréal and Québec; about 5 million people), crude daily death rates comparable to those reported in 2005–2009 were observed over the following 60-day period (Table 5).

Table 5.

Crude death rates during the 60 days following the 2010 heat waves, by health region (HR) and study period

|

HR (2010 population) |

Period |

Deaths |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| n* | Crude rates per 100,000 person-days (95% CI) | ||

| All HRs (4 908 952) |

2005-2009 |

5 189 |

1.81 (1.79–1.83) |

| |

2010 |

5 397 |

1.83 (1.78–1.88) |

| Capitale Nationale (687 950) |

2005-2009 |

805 |

1.99 (1.93–2.05) |

| |

2010 |

804 |

1.95 (1.82–2.09) |

| Lanaudière (468 381) |

2005-2009 |

431 |

1.62 (1.56–1.69) |

| |

2010 |

436 |

1.55 (1.41–1.70) |

| Laval (396 186) |

2005-2009 |

370 |

1.63 (1.56–1.71) |

| |

2010 |

428 |

1.80 (1.64–1.98) |

| Montérégie (1 444 047) |

2005-2009 |

1 390 |

1.66 (1.62–1.70) |

| |

2010 |

1 483 |

1.71 (1.63–1.80) |

| Montréal (1 912 388) |

2005-2009 |

2 193 |

1.94 (1.90–1.98) |

| 2010 | 2 246 | 1.96 (1.88–2.04) | |

CI = confidence intervals.

* Average numbers for the 2005–2009 period.

Discussion

Collectively, the eight Québec HRs affected by the July 2010 heat wave showed significant increases in the crude death and emergency department admission rates in relation to the comparison periods. However, the regional analysis identified important variations. Only three HRs had a significant increase in crude emergency department admission rates, and only the Montréal health region had higher emergency department admission and death rates simultaneously. Finally, no mortality displacement was observed over a 60-day horizon.

Deaths

As elsewhere worldwide, this study shows that heat waves can be fatal weather events [15-18]: the significant increase (33%) in crude rate is comparable to the results reported elsewhere [16,19]. However, it is lower than during two similar episodes that occurred in the Montréal HR in 1987 and 1994 when the daily mortality exceeded 100% of the historical average [20]. At the time of these previous episodes, no public health intervention plan existed and no preventive measures had been implemented. Since 2006, a formal Heat Action Plan [21] has been implemented at the provincial level for all relevant HRs, promoting a proactive approach. Moreover, the new thresholds proposed [5,7], although based on a 60% excess mortality of historical heat wave episodes, were used to establish forecast thresholds for full public health intervention before the heat wave, or at its very beginning. Since we know that heat-related deaths are largely preventable through appropriate communication and prevention [22], this more organized and proactive approach could partly explain the lower excess mortality, even with an aging population. This situation could also be partly explained by the gradual changes in the population's behaviour during heat waves, notably the increased use of air conditioning systems. Since 1987, for all households in the province of Québec, the ownership of air conditioning systems increased from 15% to 42% in 2010 [23,24]. However, the actual use of air conditioning is not measured and will vary significantly according to income, even during heat waves [25]. Unfortunately, none of this data is available by HR, which could have helped greatly in the interpretation of some of our results.

This study also shows that heat-related mortality increases rapidly from the start of the heat wave [8-11], and some of its health impacts are detectable up to three days after the maximum temperature peak [12,26]. Thus, some regional differences in heat exposure (and occurrence/ absence of rain) could explain the regional variability. The HRs of Montréal and Montérégie are the most populous in Québec, and contain significant urban heat island areas which promote an increased exposure of the population to heat [12,22,27,28]. Also, the characteristics of the heat wave are different from one region to another (Table 1). The highest maximum temperatures (≥ 34°C) involve only three HRs, including those of Outaouais and Montérégie. Otherwise, the highest minimum temperatures (≥ 24°C) involve only three HRs, including those of Montréal and Montérégie. In these highly urbanized regions, the minimum temperature peaks were reached very rapidly, namely 24 hours after the start of the heat wave. It seems that the maximum value of the minimum temperature and the time to reach this peak are important factors in estimating the intensity of a heat wave and the severity of its impacts [29,30].

The lack of statistically different impacts in the HRs other than Montréal, Outaouais and Montérégie could also be due to the small numbers of health events in the less populated regions and to the related low power of detection, or even to differences related to certain individual parameters such as age [16,19,22] or health status [12,31-34], but we have no evidence to this effect. Other studies would be needed to clarify these aspects.

The graph (Figure 1) of the daily variations (2010 vs. 2005–2009) of the all-cause deaths between July 1 and 31, 2010, suggests that this indicator has several qualities that make it useful in watching for and monitoring heat waves. In fact, there is a short period (a few hours) between the start of the heat wave and the increase in deaths, and deaths increase right from the first day. The all-cause death indicator seems to be sufficiently sensitive and specific to exceedences of the temperature thresholds, because the daily variations in deaths clearly reflect the fluctuations in temperatures during the heat wave. In this case, analysis of mortality over a 60-day horizon after the heat wave does not show any significant lower mortality, contrary to some other studies [35-38]. For some heat waves, a decrease in mortality was observed during the weeks after the wave. This short-term forward shift in mortality is also referred to as mortality displacement, or harvesting effect. This reduction in mortality usually suggests that the heat wave particularly affected individuals whose health is already so compromised that they would have died in the short term anyway [39]. Hence, in the absence of mortality displacement, it seems that the deaths measured in this study were primarily due to the July 2010 heat wave, and not to the early mortality of weakened individuals. On the other hand, we may not have detected lower forward mortality because of our methodology (e.g., periods chosen for studying the delayed effects) or the characteristics of our studied populations compared to other studies [40].

Finally, our results do not reveal a greater increase in deaths in the elderly (75 years of age and older) compared to the 0–64 year group as in other studies [22,30,41-43]. The Québec population may have various strategies for adapting to heat, independent of their age (e.g., heat wave warnings issued in the regions involved, and action plans targeting the elderly). Nonetheless, it is also possible that this absence of a greater increase in deaths in the elderly could be explained by the coarse nature of the variable (in the Québec daily death record, age is classified according to three strata only: < 65, 65–74, and > 74).

Emergency department admissions

In this study, the significant increase in emergency department admissions (4%) for all of the HRs affected by the July 2010 heat wave is similar to the increase recently observed in a California study (3%) [3]. In addition, there are some rate variations across the HRs that could be explained by local factors, but we do not have enough information to reach any conclusion about the reasons for these variations. Furthermore, the graph (Figure 1) of the daily variations in emergency department admissions (2010 vs. 2005–2009) indicates that they are modest and do not reflect the fluctuations in temperature. Such modest variations in the impact of a heat wave on these daily variations were also reported in a French study in 2005 [44]. Based on this information, the usefulness of this indicator for monitoring the health impact of a heat wave is not as clear as in the case of deaths. Nevertheless, this indicator remains useful for hospital management in such a context.

Limitations

Our study is based on the analysis of a single heat episode, which limits the generalization of results. The study is also affected by the difficulty in characterizing exposure in ecological studies. As well, the temperature values come from a single reference weather station per HR, even though each HR generally includes several cities. However, even if there could be some variation in temperatures in different parts of a region, the reference station reflects well the temperatures of the most populated areas, and thus provides valid temperatures for most of the population, according to the definition of a reference station by Environment Canada. Additionally, the presence of heat islands (and associated risk) is also greater in the more urbanized areas.

It should be mentioned that the temporary death file contains only coarse information about age and no information about the diagnosis, which limits further data interpretation. Finally, the analysis did not take atmospheric pollutants into account. This could have explained some regional differences regarding the impact on mortality, but this remains a hypothesis since the effect of atmospheric pollution on the temperature-mortality relationship remains highly controversial [15,27,40,45].

Conclusions

In Québec, public health and civil-preparedness intervention during heat wave episodes is based on a common intervention guide developed in 2004 and updated in 2006 [21], on Environment Canada weather forecasts, on specific intervention thresholds by regions, and on the Système de surveillance et de prévention des impacts sanitaires des évènements météorologiques extrêmes (SUPREME, system for surveillance and prevention of the health impacts of extreme weather events) [46,47]. This system, developed by the Institut national de santé publique du Québec, has been available since May 2010 for the province’s regional and central public health authorities. Based on weather forecasts and population vulnerability indicators, heat wave warnings can be issued and interventions implemented to prevent various health impacts in such a context. These actions, combined with major advancements in air conditioning in the last 20 years, have contributed to a marked reduction in mortality during heat waves, even in the presence of a doubling of the proportion of the elderly during the same period of time. Important residual risk remains, however, which needs to be more vigorously addressed by public health authorities in light of the expected increase in frequency and severity of heat waves and the expected further aging of the population.

Competing interests

No competing interest is declared. This research was funded by the Green Fund in the framework of Action 21 of the Québec government’s 2006–2012 Climate Change Action Plan.

Authors’ contributions

RB and GL were the principal researchers and authors. PG, DB and FC were co-authors and co-investigators. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:

Contributor Information

Ray Bustinza, Email: ray.bustinza@inspq.qc.ca.

Germain Lebel, Email: germain.lebel@inspq.qc.ca.

Pierre Gosselin, Email: pierre.gosselin@inspq.qc.ca.

Diane Bélanger, Email: diane.belanger@crchul.ulaval.ca.

Fateh Chebana, Email: fateh.chebana@ete.inrs.ca.

Acknowledgements

We thank Environment Canada and Hydro-Québec for providing various data used for this study.

References

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Special report on managing the risks of extreme events and disasters to advance climate change adaptation: summary for policymakers. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK; 2012. p. 19. [Google Scholar]

- Chaouki N. Climate Change & Health. World Health Organisation, Rabat; 2009. p. 34. [Google Scholar]

- Knowlton K, Rotkin-Ellman M, King G, Margolis HG, Smith D, Solomon G, Trent R, English P. The 2006 California heat wave: impacts on hospitalizations and emergency department visits. Environ Health Perspect. 2009;117:61–67. doi: 10.1289/ehp.11594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canada's top ten weather stories for 2010. [ http://www.ec.gc.ca/meteo-weather/default.asp?lang = En&n = 53E29740-1]

- Martel B, Giroux J-X, Gosselin P, Chebana F, Ouarda TBMJ, Charron C. Indicateurs et seuils météorologiques pour les systèmes de veille-avertissement lors de vagues de chaleur au Québec. Institut national de santé publique du Québec, Québec; 2010. p. 65. [Google Scholar]

- Projections de la population du Québec, selon le territoire de RSS, le sexe et le groupe d'âge de 5 ans, au 1er juillet, 2006 à 2031. [ http://publications.msss.gouv.qc.ca/statisti/zip%20pop%202010/Projections_RSS_2006-2031.zip]

- Chebana F, Martel B, Gosselin P, Giroux JX, Ouarda TB. A general and flexible methodology to define thresholds for heat health watch and warning systems, applied to the province of Quebec (Canada) Int J Biometeorol. 2012. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Besancenot J. Vagues de chaleur et mortalité dans les grandes agglomérations urbaines. Environnement, risques & santé. 2002;1:229–240. [Google Scholar]

- Curriero FC, Heiner KS, Samet JM, Zeger SL, Strug L, Patz JA. Temperature and mortality in 11 cities of the eastern United States. Am J Epidemiol. 2002;155:80–87. doi: 10.1093/aje/155.1.80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunst AE, Looman CWN, Mackenbach JP. Outdoor air temperature and mortality in the Netherlands: a time-series analysis. Am J Epidemiol. 1993;137:331–341. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a116680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitman S, Good G, Donoghue ER, Benbow N, Shou W, Mou S. Mortality in Chicago attributed to the July 1995 heat wave. Am J Public Health. 1997;87:1515–1518. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.87.9.1515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ledrans M, Isnard H. Impact sanitaire de la vague de chaleur d'août 2003 en France: bilan et perspectives, octobre 2003. InVS, Saint-Maurice, France; 2003. p. 120. [Google Scholar]

- Rothman KJ, Greenland S, Lash TL. Modern Epidemiology. Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia, PA; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Institut national de santé publique du Québec, Groupe de travail des indicateurs du Plan commun de surveillance à l'Infocentre de santé publique. Cadre méthodologique des indicateurs du Plan commun de surveillance à l'Infocentre de santé publique. Institut national de santé publique du Québec, Québec; 2009. p. 79. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson BG, Bell ML. Weather-related mortality: how heat, cold, and heat waves affect mortality in the United States. Epidemiology. 2009;20:205–213. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e318190ee08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basagana X, Sartini C, Barrera-Gomez J, Dadvand P, Cunillera J, Ostro B, Sunyer J, Medina-Ramon M. Heat waves and cause-specific mortality at all ages. Epidemiology. 2011;22:765–772. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e31823031c5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gasparrini A, Armstrong B. The impact of heat waves on mortality. Epidemiology. 2011;22:68–73. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e3181fdcd99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LeTertre A, Lefranc A, Eilstein D, Declercq C, Medina S, Blanchard M, Chardon B, Fabre P, Filleul L, Jusot JF. et al. Impact of the 2003 heatwave on all-cause mortality in 9 French cities. Epidemiology. 2006;17:75–79. doi: 10.1097/01.ede.0000187650.36636.1f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DIppoliti D, Michelozzi P, Marino C, De'Donato F, Menne B, Katsouyanni K, Kirchmayer U, Analitis A, Medina-Ramon M, Paldy A. et al. The impact of heat waves on mortality in 9 European cities: results from the EuroHEAT project. Environ Health. 2010;9:37. doi: 10.1186/1476-069X-9-37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Litvak E, Fortier I, Gouillou M, Jehanno A, Kosatsky T. Programme de vigie et de prévention des effets de la chaleur accablante à Montréal: définition épidémiologique des seuils d'alerte et de mobilisation pour Montréal. Direction de santé publique, Agence de développement de réseaux locaux de services de santé et de services sociaux de Montréal, Montréal; 2005. p. 34. [Google Scholar]

- Laplante L, Roman S. In: Guide d'intervention: chaleur accablante volet santé publique. Laplante L, Roman S, editor. Comité chaleur accablante de la TNCSE, Québec; 2006. p. 168. [Google Scholar]

- Kovats RS, Hajat S. Heat stress and public health: a critical review. Annu Rev Public Health. 2008;29:41–55. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.29.020907.090843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hydro-Québec. Utilisation de l'électricité dans le marché résidentiel. Rapport interne, septembre 2010. Hydro-Québec, Montréal; 2010. p. 37. [Google Scholar]

- Gosselin P, Bélanger D, Doyon B. In: Human Health in a Changing Climate. Séguin J, editor. Health Canada, Ottawa; 2008. Health impacts of climate change; pp. 211–302. [Google Scholar]

- Bélanger D, Gosselin P, Valois P, Abdous B. Vagues de chaleur au Québec méridional: adaptations actuelles et suggestions d'adaptation futures. Institut national de santé publique du Québec, Québec; 2006. p. 218. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann B, Hertel S, Boes T, Weiland D, Jockel KH. Increased cause-specific mortality associated with 2003 heat wave in Essen, Germany. J Toxicol Environ Health A. 2008;71:759–765. doi: 10.1080/15287390801985539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luber G, McGeehin M. Climate change and extreme heat events. AM J Prev Med. 2008;35:429–435. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2008.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haines A, Kovats RS, Campbell-Lendrum D, Corvalan C. Climate change and human health: Impacts, vulnerability and public health. Public Health. 2006;120:585–596. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2006.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramlow JM, Kuller LH. Effects of the summer heat wave of 1988 on daily mortality in Allegheny County. PA. Public Health Rep. 1990;105:283–289. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGeehin MA, Mirabelli M. Potential impacts of climate variability and change on temperature-related morbidity and mortality in the United States. Environ Health Perspect. 2001;109:185–189. doi: 10.1289/ehp.109-1240665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorente C, Sérazin C, Salines G, Adonias G, Gourvellec G, Lauzeille D, Malon A, Rivière S. In: Étude des facteurs de risque de décès des personnes âgées résidant en établissement durant la vague de chaleur d'août 2003. Lorente C, Sérazin C, Salines G, Adonias G, Gourvellec G, Lauzeille D, Malon A, Rivière S, editor. Institut de Veille Sanitaire, Saint-Maurice, France; 2005. p. 114. [Google Scholar]

- Semenza JC, Rubin CH, Falter KH, Selanikio JD, Flanders WD, Howe HL, Wilhelm JL. Heat-related deaths during the July 1995 heat wave in Chicago. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:84–90. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199607113350203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Semenza JC, McCullough JE, Flanders WD, McGeehin MA, Lumpkin JR. Excess hospital admissions during the July 1995 heat wave in Chicago. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 1999;16:269–277. doi: 10.1016/S0749-3797(99)00025-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Health and Global Environmental Change, Series. http://www.euro.who.int/document/e82629.pdf.

- Auger N, Kosatsky T. Chaleur accablante. Mise à jour de la littérature concernant les impacts de santé publique et proposition de mesures d'adaptation. Régie régionale de la santé et des services sociaux de Montréal-Centre; 2002. p. 35. [Google Scholar]

- Baccini M, Biggeri A, Accetta G, Kosatsky T, Katsouyanni K, Analitis A, Anderson HR, Bisanti L, D'Ippoliti D, Danova J. et al. Heat effects on mortality in 15 European cities. Epidemiology. 2008;19:711–719. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e318176bfcd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hajat S, Armstrong BG, Gouveia N, Wilkinson P. Mortality displacement of heat-related deaths: a comparison of Delhi, Sao Paulo, and London. Epidemiology. 2005;16:613–620. doi: 10.1097/01.ede.0000164559.41092.2a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Tertre A, Lefranc A, Eilstein D, Declercq C, Medina S, Blanchard M, Chardon B, Fabre P, Filleul L, Jusot JF. et al. Impact of the 2003 heatwave on all-cause mortality in 9 French cities. Epidemiology. 2006;17:75–79. doi: 10.1097/01.ede.0000187650.36636.1f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huynen MM, Martens P, Schram D, Weijenberg MP, Kunst AE. The impact of heat waves and cold spells on mortality rates in the Dutch population. Environ Health Perspect. 2001;109:463–470. doi: 10.1289/ehp.01109463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basu R. High ambient temperature and mortality: a review of epidemiologic studies from 2001 to 2008. Environ Health. 2009;8:40. doi: 10.1186/1476-069X-8-40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Applegate WB, Runyan JW Jr, Brasfield L, Williams ML, Konigsberg C, Fouche C. Analysis of the 1980 heat wave in Memphis. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1981;29:337–342. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1981.tb01238.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballester F, Corella D, Perez-Hoyos S, Saez M, Hervas A. Mortality as a function of temperature. A study in Valencia, Spain, 1991–1993. Int J Epidemiol. 1997;26:551–561. doi: 10.1093/ije/26.3.551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institut de Veille Sanitaire. Impact sanitaire de la vague de chaleur en France survenue en août 2003. Institut de Veille Sanitaire, Saint-Maurice, France; 2003. p. 75. [Google Scholar]

- Etchevers A, Sarter H, Laaidi K, Empereur-Bissonnet P. Impact sanitaire de la vague de chaleur du mois du juin 2005. BEH. 2006;19-20:138–140. [Google Scholar]

- Hajat S, Kovats RS, Atkinson RW, Haines A. Impact of hot temperature on death in London: a time series approach. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2002;56:367–372. doi: 10.1136/jech.56.5.367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toutant S, Gosselin P, Bélanger D, Bustinza R, Rivest S. An open source web application for the surveillance and prevention of the impacts on public health of extreme meteorological events: the SUPREME system. Int J Health Geogr. 2011;10:39. doi: 10.1186/1476-072X-10-39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bustinza R, Toutant S, Bélanger D, Gosselin P. Outil de vigie et surveillance des vagues de chaleur. BISE. Institut national de santé publique du Québec, Québec; 2011. [Google Scholar]