Abstract

Purpose

Interhospital critical care transfers are common, yet few studies address the underlying reasons for transfers. We examined clinician and patient/surrogateperceptions about interhospital transfers and assessed their agreement on these transfers.

Materials and Methods

A mixed-mode survey of three major stakeholders in interhospital transfers to an academic medical intensive care unit (MICU) from August 2007 to April 2008.

Results

62 hospitals transferred 138 patients during the study period. Response rates varied among stakeholders (accepting physician: 90%, referring physicians: 20%, patients/surrogates: 33%). All three groups frequently endorsed quality of care and need for a specific test/procedure as important. Referring hospital reputation and quality were rarely endorsed. Accepting physicians and patients/surrogates substantially agreed on the need for a specific test (kappa=0.70) and increased survival (kappa=0.78), but otherwise had fair to poor agreement. Referring physicians and patients/surrogates rarely agreed and sometimes disagreed greater than expected by chance (kappa <0). Physician pairs strongly agreed on the importance of accepting hospital experience (kappa=0.96), but agreed less on patient satisfaction at the referring hospital (kappa=0.37) and referring hospital reputation (kappa=0.35).

Conclusions

Stakeholders do not always agree on the reasons for critical care transfers. Efforts to improve communication are warranted to insure informed patient choices.

Keywords: intensive care, critical care, interhospital transfer, survey

INTRODUCTION

An estimated 4.5% of admissions to an intensive care unit (ICU) involve interhospital transfers, leading to roughly 50,000 ICU transfers per year in the United States. These transfers account for significant health care expenditures yet are not always associated with improved patient satisfaction and outcomes. This disconnect has led to some health care opinion leaders to call for a more strategic approach to interhospital ICU transfers, and to the reorganization of adult critical care. Proposed strategies include regionalized critical care, in which select patients would be systematically transferred to designated centers of excellence, and ICU telemedicine, in which transfers might be avoided by providing remote expertise to small hospitals.

Prior to introducing broad system reforms such as these, it is important to better understand the reasons underlying interhospital ICU transfers under the current system. Patients could undergo transfer to receive higher quality care in the form of clinical expertise and vigilance, to receive a specific test or procedure, for family convenience, or because either they or their families are unsatisfied with the care received at the referring hospital. Each of these scenarios have different implications for patients and clinicians involved in the transfer decision, as well as the effectiveness of strategies to modify the incidence, timeliness and outcomes of transfers as a whole.

At present there are few studies examining the reasoning of various stakeholders involved in interhospital ICU transfers. Little is known about which caregivers initiate transfers, and whether patients and physicians even agree on the underlying reasons for transfer. To learn more about the reasons underlying interhospital transfers to an academic medical ICU, we conducted a survey of the major stakeholders involved in these transfers (accepting physicians, referring physicians, and patients or their surrogates). Given that agreement on the reasons for interhospital ICU transfers is likely a reflection of high-quality communication, we sought to determine whether there was agreement about the reasons for transfer among the various stakeholders.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study Design and Subjects

We performed a mixed-mode survey of key stakeholders in interhospital ICU transfers into the medical ICU (MICU) of the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania from August 2007 to April 2008. The Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania is a 685 bed urban academic medical center that serves as a tertiary referral center for southeastern Pennsylvania, southern New Jersey, and Delaware. The MICU contains 24 beds, all of which operate under a high-intensity physician staffing model in which patient care is provided by one of two medical teams lead by intensivist physicians. Staff intensivists rotate in the MICU for two weeks at a time during which they share duties coordinating referring hospital transfers. Transfers into the MICU during the study period were identified using the hospital’s interhospital transfer tracking log and confirmed by contacting the attending intensivist coordinating transfers at the time. There are no formal bed occupancy or clinical criteria for accepting interhospital transfers at HUP. The only specific policy regards insurance status: transfers with an emergency medical need are accepted regardless of insurance status, whereas elective transfers are considered only for those patients who have health insurance. We sought to survey the three key-stakeholders involved: the accepting physician (i.e. the MICU attending that accepted the patient in transfer), the referring physician (i.e. the referring hospital attending physician at the time of transfer) and the patient or their surrogate.

Survey Development and Administration

We developed the survey based on previous qualitative analyses of interhospital transfers. We focused on three hypothesized domains: hospital resources and quality, patient/surrogate convenience, and patient/surrogate satisfaction or concerns. We constructed these questions as a series of 12 statements about potential factors underlying the transfer, followed by either a binary response, i.e. yes/no, with an option for uncertain; or a Likert response, i.e. agree, neutral, disagree, with an option for uncertain (Table 1). We also asked referring physicians and patient/surrogates to identify the person most responsible for initiating the transfer process from seven options: the ICU doctor, another doctor, a nurse, another staff member, themselves, or a friend or relative.

Table 1.

Survey Questions provided to stakeholders at the time of transfer. Responses to all statements were either “yes”, “no”, or “uncertain”, or, “agree”, “neutral”, “disagree”, or “uncertain”.

| Survey Statement |

|---|

| Resources and Quality |

| The physicians at the accepting hospital could provide a higher quality of care |

| The patient needed a specific test/procedure that was not available at the referring hospital |

| Physicians experienced with the patient’s medical care are at the accepting hospital |

| Transferring the patient increased their chance of survival |

| Convenience |

| The patient or family’s home is closer to the accepting hospital |

| Insurance or lack of insurance necessitated transfer |

| Patient Satisfaction and Concerns |

| The patient or patient’s family requested a transfer to another hospital |

| The patient or patient’s family was not satisfied with the level of care at the referring hospital |

| The patient or patient’s family was concerned that their health was not improving |

| The patient or patient’s family was not satisfied with the general reputation of the referring hospital |

| The patient or patient’s family had a positive view of the accepting hospital based on a past experience |

| The patient or patient’s family had a positive view of the accepting hospital due to its general reputation |

After initial development we further refined the survey through a series of focus groups and pilot periods. First, we reviewed the survey in two focus groups comprised of health services researchers experienced in survey research (n=12). Second, we piloted the survey on 10 interhospital transfers, administering the instrument to accepting physicians, referring physicians, and patients or their surrogate decision makers (n=20). At each step we asked participants to comment about the wording and clarity of the survey and made revisions based upon their feedback.

After obtaining informed consent, the survey was administered through either an in-person interview (accepting physicians and patient/surrogates) or telephone interview (referring physicians). All interviews were performed within 48 hours of transfer. A trained research assistant performed the interviews and recorded the responses. Up to two attempts were made to contact all stakeholders. We offered no incentives for participation.

Analysis

In addition to the survey data, we collected clinical and demographic data on the transferred patients via chart abstraction. For those patients or surrogates who refused consent, no patient-level data were collected. We also collected data on the referring hospitals using the 2006 American Hospital Association Annual Survey. Distance from the referring hospital to the accepting hospital was calculated as the linear arc distance in miles using exact latitudes and longitudes. Patient and hospital characteristics are summarized as frequency (percent), mean ± standard deviation.

We calculated survey response rate as the number of completed surveys by a respondent divided by the number of patients transferred during the study period. Survey questions about the reason for transfer were summarized as the percent responding in agreement that the particular reason for transfer was important (i.e. responding either “yes” or “agree” depending on the response type). All other responses were grouped into a single category indicating that the reason for transfer was not considered important. We ranked reasons for transfer by the percent of respondents in agreement that a particular reason was important in the transfer decision. We did not attempt to determine the single most important reason for transfer, as in the pilot phase respondents were reluctant were identify a single most important reason and frequently declined to answer the question.

We compared stakeholders’ agreement on reasons deemed important for a given transfer using the multi-rater Kappa statistic to assess concordance on the raw responses. We performed this analysis separately for the three pairs of stakeholders: accepting physicians and referring physicians: accepting physicians and patients/surrogates, and referring physicians/and patients/surrogates. By necessity these analyses were only performed when both pairs participated in the study. Following Landis and Koch’s conventions, we interpreted concordance as almost perfect (kappa: 0.81–1), substantial (kappa: 0.61–0.8), moderate (kappa: 0.41–0.6), fair (kappa: 0.21–0.4), slight (kappa: 0.01–0.2) or poor (kappa: ≤ 0). Quantitative analyses were performed using Stata 9.2 (StataCorp, College Station, Texas). The University of Pennsylvania Institutional Review Board approved the study protocol.

RESULTS

During the study period 138 patients were transferred from referring hospitals to the MICU. We received 124 surveys from accepting physicians, 27 surveys from referring physicians, and 46 surveys from patients or their surrogates for overall response rates of 90%, 20%, and 33%, respectively. Patient characteristics are shown in Table 2. A majority of patients were transferred from referring hospital intensive care units (78%), with fewer transferred from emergency departments (22%). At the time of transfer, 47% of the patients were mechanically ventilated. Seventy-two (53%) of patients were seen at the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania as an outpatient prior to the time of transfer and 41 (30%) had a prior admission. Patients were transferred with a wide range of primary diagnoses, with acute respiratory failure/acute lung injury (25%), cirrhosis/hepatic failure (14%), malignancy (11%), and sepsis (9%) predominating.

Table 2.

Patient Demographics (N = 138)

| Variable | Value a |

|---|---|

| Age in years, Mean | 54 +/− 18 |

| Female gender, N (%) | 59 (43) |

| Ethnicity, N (%) | |

| Black | 29 (21) |

| White | 92 (67) |

| Hispanic/Other | 5 (4) |

| Unknown | 12 (8) |

| Admission Source, N (%) | |

| Outside Hospital Emergency Department | 31 (22) |

| Outside Hospital Intensive Care Unit | 107 (78) |

| Ventilated at time of Transfer, N (%) | 62 (47) |

| Mechanism of Transfer, N (%) | |

| Ambulance | 100 (72) |

| Helicopter | 38 (28) |

| Prior Encounters at Accepting Hospital, N (%) | |

| Prior outpatient visit | 72 (53) |

| Prior admission | 41 (30) |

| Distance from patient home in miles, Mean | |

| From home to the referring hospital | 20.5 +/− 61 |

| From home to accepting hospital | 44 +/− 100 |

| Diagnosis at time of transfer, N (%) | |

| Cardiovascular | 5 (4) |

| Neurologic | 5 (4) |

| Pulmonary | |

| Intervention/Procedure | 3 (2) |

| Hemoptysis | 3 (2) |

| Transplant Evaluation | 8 (6) |

| Respiratory Failure/Acute Lung Injury | 35 (25) |

| Gastrointestinal | 9 (6) |

| Cirrhosis/Hepatic Failure | 19 (14) |

| Sepsis | 12 (9) |

| Malignancy | 15 (11) |

| Drug Overdose/Poisoning | 9 (6) |

| Other | 15 (11) |

Values are presented as number (percent) or mean +/− standard deviation as appropriate.

Sixty-two different hospitals transferred patients to the medical ICU during our study period. Transferring hospital characteristics are shown in Table 3. Thirty-three hospitals (55%) were located in the state of Pennsylvania. The transferring hospitals tended to be large teaching hospitals: 37 (60%) had an academic affiliation, with an average of 318 hospital beds and 23.5 ICU beds. The average distance from the transferring hospital to the study hospital was 55 miles.

Table 3.

Transferring hospital characteristics (N=62)

| Variable | Valuea |

|---|---|

| State | |

| Pennsylvania, N (%) | 34 (55) |

| Out of State, N (%) | 28 (45) |

| Distance to accepting hospital in miles, Mean | 55 +/− 129 |

| Total hospital beds, Mean | 318 +/− 191 |

| Total hospital ICU beds, Mean | 23.5 +/− 21.5 |

| Affiliation with a medical school, N (%) | 37 (60) |

Values are presented as number (percent) or mean +/− standard deviation as appropriate.

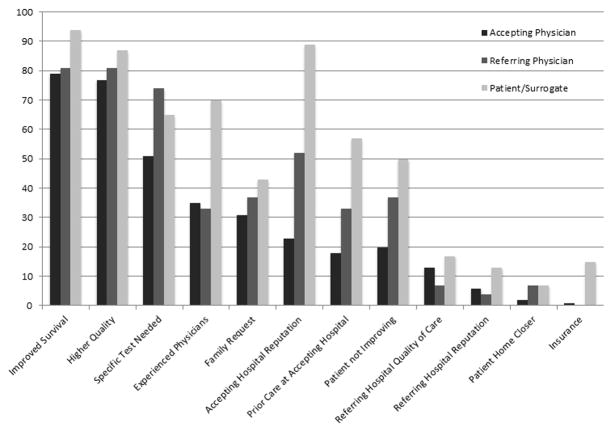

For all respondents, the percent of stakeholders rating a reason for interhospital ICU transfer as important is provided in Figure 1. In general, accepting physicians, referring physicians and patients/surrogates all agreed that increased chance of survival (79%, 81%, and 94%, respectively), quality of care at HUP (77%, 81%, and 87%, respectively) and need for a specific test or procedure (51%, 74%, and 65%, respectively) were important reasons for transfer. Accepting physicians, referring physicians, and patients/surrogates were less likely to rate patient or family requesting the transfer (31%, 37%, and 43%, respectively) as important reasons for transfer. Additionally, accepting physicians, referring physicians, and patients/surrogates rarely rated patient or surrogate satisfaction with the care at the referring hospital (13%, 7%, and 17%, respectively), patient or surrogate satisfaction with the general reputation of the referring hospital (6%, 4%, and 13%, respectively), accepting hospital proximity to the patient’s home (2%, 7%, and 7%, respectively), or insurance (1%, 0%, and 15%, respectively) as important reasons for transfer

Figure 1.

Percent of accepting physicians (n=124), referring physicians (n=27), and patients/surrogates (n=46) rating a reason for inter-hospital ICU transfer as important

Both admitting physicians and referring physicians were less likely than patients/surrogates to endorse having experienced physicians at the accepting hospital (35%, 33%, and 70%, respectively) as a major reason to transfer, and they were also less likely to rate that the patient feeling that their health was not improving was important to the transfer process (20%, 37%, and 50%, respectively). Both accepting physicians and referring physicians were also less likely than patients/surrogates to rate having a positive view of the accepting hospital based on prior experience (18%, 33%, and 57%, respectively) and the accepting hospital’s general reputation (23%, 52%, and 89%, respectively).

Concordance between stakeholders for specific transfer pairs is shown in Table 4. Overall there were 26 accepting physician and referring physician pairs, 45 accepting physician and patient/surrogate pairs, and 16 referring physician and patient/surrogate pairs. Physicians had almost perfect agreement on specific transfers when patient survival (k=0.87), experienced physicians at HUP (k=0.96), and family request (k=0.82) were reasons for transfer. While rarely endorsed as an important reason, inter-physician concordance was substantial when either felt that the proximity of the patient’s home to the accepting hospital (k=0.76) was part of the decision to transfer. Otherwise, inter-physician concordance was fair to moderate for the remaining reasons.

Table 4.

Survey Statements are accompanied by their inter-stakeholder concordance values (kappa statistics) for accepting physicians and referring physicians (n = 26 pairs), accepting physician and patient/surrogates (n = 45 pairs) and referring physicians and patient/surrogates (n = 16 pairs).

| Accepting Physician and Referring Physician (n = 26) | Accepting Physician and Patient/Surrogate (n= 45) | Referring Physician and Patient/Surrogate (n = 16) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Resources and Quality | |||

| Higher Quality of Care at Accepting Hospital | 0.39 | 0.37 | -1.03 |

| Specific Test/Procedure Available at Accepting Hospital | 0.40 | 0.70 | - |

| Experienced Physicians at Accepting Hospital | 0.96 | 0.57 | 0.57 |

| Improved Chance of Survival at Accepting Hospital | 0.87 | 0.78 | 0.48 |

| Convenience | |||

| Patient Home Closer to Accepting Hospital | 0.76 | 0.33 | - |

| Insurance or Lack of Insurance Necessitated Transfer | - | 0.49 | - |

| Patient Satisfaction and Concerns | |||

| Request for Transfer to Another Hospital | 0.82 | 0.64 | -1.08 |

| Not Satisfied with Quality of Care at Referring Hospital | 0.37 | 0.22 | 0.38 |

| Patient not Improving at Referring Hospital | 0.59 | 0.23 | -0.28 |

| Not Satisfied with Referring Hospital Reputation | 0.35 | 0.35 | 0.47 |

| Positive Prior Experience at Accepting Hospital | 0.43 | 0.24 | 0.39 |

| Positive View of Accepting Hospital Reputation | 0.43 | 0.21 | 0.27 |

Accepting physicians and patients had substantial agreement on specific transfers when increased survival (k=0.78), the need for a specific procedure or test (0.70), and patient or family request (0.64) were felt to be reasons for transfer. Despite a high percentage of stakeholders that viewed quality at the accepting hospital as important, the concordance among this group was only moderate (0.37). Otherwise, accepting physicians and patients/surrogates had fair to moderate agreement when rating specific reasons for transfer.

Regarding referring physician and patient/surrogate pairs, there was moderate agreement on having experienced physicians at the accepting hospital (k=0.57), increased chance of survival (k=0.48), and dissatisfaction with the referring hospital reputation (k=0.47). There was fair agreement on dissatisfaction with the quality of care at the referring hospital (k=0.38), having a positive view of the accepting hospital based on past experiences (k=0.39), and on its general reputation (k=0.27). For these pairs, there was less agreement than would be expected by chance when quality of care at the accepting hospital (k= −1.03), patient or family requesting transfer (k= −1.08), and when patients or surrogates were concerned that their health was not improving (k= −0.28) were rated as reasons for transfer. Referring physicians and patients/surrogates did not have substantial or near perfect agreement on any specific reasons for transfer.

DISCUSSION

Interhospital transfers of critically ill patients play a major role in the critical care delivery system, yet the reasons underlying critical care transfers are largely unknown. In a survey of the three major stakeholders involved in interhospital ICU transfers, we found that the reasons commonly rated as important to the transfer process varied across stakeholders, with often little or no agreement for specific transfer reasons.

Perhaps the most concerning finding in our study is that physicians and patients rarely agree, and occasionally disagree, on the specific reasons for critical care transfers. Although this lack of agreement does not prove ineffective communication, it doesraise concerns about the quality of decision-making occurring in the transfer process. Ideally, a request for a critical care transfer should arise from a patient-centered discussion between a patient and a referring provider that addresses the merits and potential risks of undergoing a transfer. Reasonably, the accepting hospital should be chosen based on their ability to provide an expertise or service that is currently not available at the referring hospital. The lack of agreement among stakeholders suggests that transfers occur through much more haphazard mechanisms. Poor patient-physician communication may result in transfers that are solely based on perceived differences in quality, but yet actually stem from patient concerns surrounding their prognosis or questions about their care currently not being addressed. Improving the quality of communication between patients and providers at referring ICUs may result in increased patient satisfaction and potentially a reduction in the number of transfers driven by patient dissatisfaction or concerns.

Our study is among several to highlight shortcomings that exist around communication during inter-hospital transfers. In a qualitative study that focused on interhospital transfers, Dy et al showed that patients undergoing transfers commonly cited poor physician-communication as a major reason to request a transfer. They also found that referring physicians and patients often disagreed about who initiated the transfer process, a finding that our study supports. Together, these studies reinforce that patient preferences may be misunderstood or minimized in the process of critical care interhospital transfers. This variability in the quality of communication is not specific to critical care transfers alone. Many areas of medicine also struggle to optimize communication through the inclusion of patient perspectives. Perhaps the some of the more well-known include variations in the quality of end of life communication and in the process of providing informed consent. Similar to these areas of healthcare, strategies to improve the process of critical care transfers must include efforts to improve communication among key stakeholders.

The divergence of stakeholder opinions on the reasons for transfers calls into question the notion that there is one reason for any given transfer. When a critically ill patient with a readily identifiable disease presents to a hospital that cannot provide definitive intervention, prompt agreement on a single reason for transfer may be easily attainable. For example, if a patient presents with an acute myocardial infarction to a hospital that does not provide percutaneous coronary angiography, that patient is likely to undergo an emergent transfer to a center capable of providing that treatment. It is very likely that all three stakeholders clearly understand the reason for transfer in this circumstance as well as the time sensitive nature of the desired treatment. Conversely, many patients that undergo critical care transfers do not have specific diagnoses that mandate specific interventions. Critically ill patients comprise a wide range of diagnoses that includes both specific diseases as well as non-specific syndromes. While some of these diseases and syndromes may benefit from a transfer to a higher functioning ICU during the initial stages of critical illness, many patients undergo critical care transfers in the later phases of critical illness – a time where the benefits of a tested interventions such as low stretch mechanical ventilation or exposure to a multidisciplinary staffing model have little evidence to suggest superiority. Due to this complexity, it is conceivable that many critically ill patients undergo interhospital transfers for reasons that may differ depending on which stakeholder is asked. Clearly, the perception that there is one reason for a transfer is not an empirically valid concept in a diverse population of critically ill patients.

The ambiguity and lack of concordance that currently exists around many critical care transfers calls into question whether the majority of patients that currently undergo interhospital ICU transfers derive a mortality benefit from these transfers. Even if transfers do improve mortality, some patients, if made aware, may not wish to trade a marginal improvement in outcome if it means further distancing themselves from their social support structure. One study suggested in a rural group of Veterans awaiting elective surgery that there is a strong patient preference for local care even when travel to a regional center would result in lower operative mortality. Although stakeholders in our study rarely endorsed patient proximity as a reason for transfer, there is a clear need to better understand patient characteristics and their likely of benefitting from a transfer prior to implementing a regionalized system where interhospital transfers would increase in volume.

Our study has several limitations. First, this was a single center study of consecutive consented patients presenting to a medical ICU over a nine month period. These results may not generalize to other specialty ICUs or other ICUs in other regions of the United States. Second, the survey response rate of both the patients or their surrogates and the referring physicians was low, as patients and surrogates were frequently unable to complete the survey within 48 hours of arrival to the accepting hospital and referring physicians were difficult to contact post-transfer. Having more data on why survey response rates were low for these stakeholders would have provided more granular information on the process of communication during interhospital transfers. However, due to data collection limitations placed by our institutional review board, we were unable to collect data on patients who refused consent. Third, this study also could not examine time spent at the referring hospital. There may be important differences in reasons for transfer depending on how long the patient spent at the referring hospital. For example, patients transferred after a prolonged hospitalization at the referring hospital may be more likely to endorse fear of not improving after failing to respond to an initial trial of critical care. Whereas, a patient presenting to a referring hospital may quickly be transferred if that patient has an established relationship with the accepting hospital, or if that patient is need a specific test upon presentation. Lastly, there were no data available for those patients denied transfer by the accepting physician. Given that denied transfers likely represent a disagreement between the accepting physicians and either the referring physician or patient, the absence of this information suggests that the true concordance may be even lower than we estimated.

CONCLUSION

In sum, we found that the reasons behind interhospital ICU transfers generally reflect the perception that there are additional resources and quality at the accepting hospital, although there is a wide amount of variability. In looking at specific transfers, there is a substantial amount of discordance among the major stakeholders in the transfer process. If the field of critical care is to move towards a formal regionalized approach, there needs to be a better understanding of the reasons behind the initiation of transfers with a particular emphasis placed on understanding patient preferences and on ensuring that patients be transferred to centers with the highest available quality of care.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Wagner is supported by T32HL098054 from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Dr. Iwashyna is supported by K08HL091249 from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute.

Footnotes

Financial Support: We have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Iwashyna TJ, et al. The structure of critical care transfer networks. Med Care. 2009;47(7):787–93. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e318197b1f5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Iwashyna TJ, Courey AJ. Guided transfer of critically ill patients: where patients are transferred can be an informed choice. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2011 doi: 10.1097/MCC.0b013e32834b3e55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Iwashyna TJ, et al. Uncharted paths: hospital networks in critical care. Chest. 2009;135(3):827–33. doi: 10.1378/chest.08-1052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Manthous CA. Leapfrog and critical care: evidence- and reality-based intensive care for the 21st century. Am J Med. 2004;116(3):188–93. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2003.08.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gasperino J. The Leapfrog initiative for intensive care unit physician staffing and its impact on intensive care unit performance: A narrative review. Health Policy. 2011;102(2–3):223–8. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2011.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kelley MA, et al. The critical care crisis in the United States: a report from the profession. Chest. 2004;125(4):1514–7. doi: 10.1378/chest.125.4.1514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barnato AE, et al. Prioritizing the organization and management of intensive care services in the United States: the PrOMIS Conference. Crit Care Med. 2007;35(4):1003–11. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000259535.06205.B4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kahn JM, et al. Hospital volume and the outcomes of mechanical ventilation. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(1):41–50. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa053993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Peelen L, et al. The influence of volume and intensive care unit organization on hospital mortality in patients admitted with severe sepsis: a retrospective multicentre cohort study. Crit Care. 2007;11(2):R40. doi: 10.1186/cc5727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kahn JM, et al. Regionalization of medical critical care: what can we learn from the trauma experience? Crit Care Med. 2008;36(11):3085–8. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31818c37b2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kahn JM, et al. Potential value of regionalized intensive care for mechanically ventilated medical patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;177(3):285–91. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200708-1214OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jacobs P, Rapoport J, Edbrooke D. Economies of scale in British intensive care units and combined intensive care/high dependency units. Intensive Care Med. 2004;30(4):660–4. doi: 10.1007/s00134-003-2123-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kahn JM, et al. Physician attitudes toward regionalization of adult critical care: a national survey. Crit Care Med. 2009;37(7):2149–54. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181a009d0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rosenfeld BA, et al. Intensive care unit telemedicine: alternate paradigm for providing continuous intensivist care. Crit Care Med. 2000;28(12):3925–31. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200012000-00034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Breslow MJ, et al. Effect of a multiple-site intensive care unit telemedicine program on clinical and economic outcomes: an alternative paradigm for intensivist staffing. Crit Care Med. 2004;32(1):31–8. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000104204.61296.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thomas EJ, et al. Association of telemedicine for remote monitoring of intensive care patients with mortality, complications, and length of stay. JAMA. 2009;302(24):2671–8. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dy SM, Rubin HR, Lehmann HP. Why do patients and families request transfers to tertiary care? a qualitative study. Soc Sci Med. 2005;61(8):1846–53. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.03.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pronovost PJ, et al. Physician staffing patterns and clinical outcomes in critically ill patients: a systematic review. JAMA. 2002;288(17):2151–62. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.17.2151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Landis JR, Koch GG. An application of hierarchical kappa-type statistics in the assessment of majority agreement among multiple observers. Biometrics. 1977;33(2):363–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Levy MM. Shared decision-making in the ICU: entering a new era. Crit Care Med. 2004;32(9):1966–8. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000140089.67373.0b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gombeski WR, Jr, et al. Selection of a hospital for a transfer: the roles of patients, families, physicians and payers. J Hosp Mark. 1997;12(1):61–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hirth RA, et al. Willingness to pay for diagnostic certainty: comparing patients, physicians, and managed care executives. J Gen Intern Med. 1999;14(3):193–5. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1999.00313.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rentsch D, et al. Hospitalisation process seen by patients and health care professionals. Soc Sci Med. 2003;57(3):571–6. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(02)00404-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hofmann JC, et al. Patient preferences for communication with physicians about end-of-life decisions. SUPPORT Investigators. Study to Understand Prognoses and Preference for Outcomes and Risks of Treatment. Ann Intern Med. 1997;127(1):1–12. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-127-1-199707010-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Steinhauser KE, et al. Factors considered important at the end of life by patients, family, physicians, and other care providers. JAMA. 2000;284(19):2476–82. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.19.2476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ross JS, et al. Hospital volume and 30-day mortality for three common medical conditions. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(12):1110–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa0907130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Finlayson SR, et al. Patient preferences for location of care: implications for regionalization. Med Care. 1999;37(2):204–9. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199902000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]