Abstract

Mitochondria are important organelles for providing the ATP and carbon skeletons required to sustain cell growth. While these organelles also participate in other key metabolic functions across species, they have a specialized role in plants of optimizing photosynthesis through participating in photorespiration. It is therefore critical to map the protein composition of mitochondria in plants to gain a better understanding of their regulation and define the uniqueness of their metabolic networks. To date, <30% of the predicted number of mitochondrial proteins has been verified experimentally by proteomics and/or GFP localization studies. In this mini-review, we will provide an overview of the advances in mitochondrial proteomics in the model plant Arabidopsis thaliana over the past 5 years. The ultimate goal of mapping the mitochondrial proteome in Arabidopsis is to discover novel mitochondrial components that are critical during development in plants as well as genes involved in developmental abnormalities, such as those implicated in mitochondrial-linked cytoplasmic male sterility.

Keywords: Arabidopsis thaliana, mitochondria, proteomics, heterogeneity, protein complex, post-translational modifications, functional proteomics

Introduction

Mitochondria are semi-autonomous, double membrane bound organelles with unique morphologies and highly specialized functions. While these organelles are well-recognized for energy metabolism via coupling the oxidation of organic acids with oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS), they also have diverse functional roles such as metabolism of amino acids and biosynthesis of cofactors and vitamins. Mitochondria in plants are set apart from their mammalian counterparts by their mediation of photosynthesis through providing alternative electron sinks for photosynthetic products and their participating in photorespiration (Padmasree et al., 2002). In order to fully understand the functional roles of mitochondria in photosynthetic cells, it is essential to establish their total protein make-up (proteome) and their post-translational modifications (PTMs), as well as to generate a protein atlas that collects information about mitochondrial protein expression patterns during stress and in different cells, tissues, and organs.

Arabidopsis thaliana became the first model system for plants after its genome was fully sequenced and made publicly available in 2000 (The Arabidopsis Genome Initiative, 2000). In the last decade, tremendous progress has been made, by both experimental and bioinformatics approaches, to define the mitochondrial proteome in this model plant species. Like its yeast and mammalian counterparts, most of the mitochondrial proteins in Arabidopsis are encoded by the nuclear genome. Based on the analyses of the N-terminal targeting peptide sequences in Arabidopsis, there are about 2500 predicted nuclear-encoded mitochondrial proteins (representing 7–10% of all encoded proteins) with broad functional roles (Heazlewood et al., 2007; Cui et al., 2011). In comparison, the mitochondrial genome encodes for only 57 gene products (Unseld et al., 1997). The first extensive experimental studies of the mitochondrial proteome in Arabidopsis identified ∼100–150 proteins (Kruft et al., 2001; Millar et al., 2001; Werhahn and Braun, 2002; Millar and Heazlewood, 2003). Improvement of organelle purification procedure, availability of different protein mapping strategies, enhanced sensitivity of peptide detection by mass spectrometry (MS), and improved genomic resources and peptide identification software have driven a significant increase in the number of mitochondrial proteins identified across different model species – from 843 in Arabidopsis (Table S1A in Supplementary Material) and 851 in yeast (Reinders et al., 2006), to 1404 in mouse (Forner et al., 2009).

Given the number of proteins identified so far in Arabidopsis mitochondrion, it is clear that our understanding of its composition and functions in plants is far from complete. In this mini-review, we will provide an update on the status of Arabidopsis mitochondrial proteomics research based on published data in the past 5 years (2007–2012). We would refer readers to previous review articles for more comprehensive overviews on the progress of plant mitochondrial proteomics in the preceding years (Millar et al., 2005, 2011; Ito et al., 2007; Dudkina et al., 2010).

How Far are We from Compiling the Complete Set of Arabidopsis Mitochondrial Proteins?

A recent in-depth analysis of the proteome in Percoll-purified mitochondria has identified a non-redundant set of 572 proteins in Arabidopsis cell culture (Taylor et al., 2011). With a combined proteomics, localization experiment and literature confirmation approach, a set of 38 mitochondrial proteins have been found in or associated with the mitochondrial outer membrane (Duncan et al., 2011). More recently, a total of 66 novel integral membrane proteins have been identified in mitochondria using a MS-based quantitative enrichment approach (Tan et al., 2012). A new set of components with unknown functions have also been identified in a number of recent studies, including the analysis of the mitochondrial fraction from: (i) separated protein complexes (Klodmann et al., 2010; Klodmann and Braun 2011; Klodmann et al., 2011; Schertl et al., 2012); (ii) enriched phospho-proteome (Ito et al., 2009); (iii) different tissue types (Lee et al., 2012); (iv) various time points of a diurnal cycle (Lee et al., 2010); and (v) cells subjected to biotic stress (Livaja et al., 2008).

While various large-scale proteomics studies over the last 5 years have led to the identification of a non-redundant set of 843 putative mitochondrial proteins (Table S1A in Supplementary Material), it remains difficult to discriminate true mitochondrial proteins from contaminants, particularly for low abundant proteins, in a sample. It has been estimated that about 11% of the total spot intensity on a 2-D map of mitochondria from Arabidopsis cell culture are proteins originated from other compartments (Taylor et al., 2011). By querying previous evidence from literature and/or consensus subcellular localization prediction score from publicly available databases [SUBA3 (Heazlewood et al., 2007); ARAMEMNON7.0 (Schwacke et al., 2003)], we define a set of 504 proteins which can be assigned to be mitochondrial-localized in Arabidopsis with high confidence (Table S1B in Supplementary Material). This approach is biased toward proteins that are highly abundant and does not explicitly imply that the remaining proteins are in fact contaminants from other compartments. Some of these proteins lack a predictable targeting presequence, may be dual-targeted to multiple compartments and/or are present in relatively low amount, thus their localization should be confirmed in the future through multiple independent proteomic analyses and/or by fluorescent protein localization.

According to the SUBA database, a number of GFP tagging studies have revealed the mitochondrial localization of 222 proteins that cannot be identified through proteomic approaches (Table S1C in Supplementary Material), most of which are low abundance proteins involved in the processing and maintenance of the mitochondrial genome. Together with the proteomics set, 726 proteins can be confidently assigned as mitochondrial, <30% of the presumed number of predicted proteins. To further expand the current Arabidopsis mitochondrial protein compendium, it is essential to overcome the challenge of identifying low abundance proteins. To achieve this a number of approaches could be employed including protein enrichment tools, such as proteominer (Fröhlich et al., 2012) or protein fractionation approaches including strong cation exchange (SCX) or off-gel electrophoresis (OGE) prior to RP-LC-MS (Chenau et al., 2008; Ito et al., 2011). Together with biological fractionation approaches such as investigation of pre-fractionated sub-mitochondrial compartments or enrichment by metal or co-factor binding approaches and advances in LC-MS techniques and equipment, it is likely that an increasing number of low abundance proteins will be revealed.

Functions of the Mitochondrial Proteome in Arabidopsis

Mitochondrial protein functions and abundance

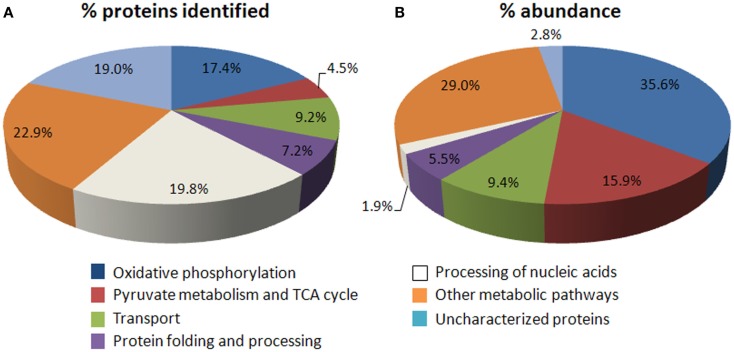

Of the confirmed set of mitochondrial proteins (Table S1B in Supplementary Material), ∼22% are components of pyruvate metabolism/TCA cycle and OXPHOS, while a similar number (∼20%) are identified as subunits of machinery for mitochondrial gene expression and maintenance (Figure 1A). In the yeast mitochondrial proteome, a similar proportion (∼15%) of identified proteins are involved in energy metabolism (Schmidt et al., 2010). When comparing the abundance of proteins in these functional categories using the recently published LC-MS/MS data (Taylor et al., 2011), energy metabolism comprises over 50% of the total protein abundance in mitochondria, whereas <2% is associated with processing mitochondrial DNA/RNA (Figure 1B). The observed abundance of proteins in energy metabolism is consistent with the main role of mitochondria in the cell and bulk of the chemical reactions performed in the organelle; in contrast, the low abundance of proteins for mitochondrial DNA/RNA processing can probably be attributed to their relatively less stable nature so that they can respond rapidly to external stimuli or to changes in energy cost (Schwanhausser et al., 2011), the transient need for their functions during the life of cells and presumably the high specific activity of their functions. At the whole cellular level, components in this functional category have recently been shown to have a high turnover rate in Arabidopsis (Li et al., 2012). Mitochondrial proteins involving nucleic acid processing appear to perform highly specialized functions and do not seem to have overlapping specificity. Only ∼12% of the proteins in the yeast mitochondrial proteome are dedicated to genome maintenance and processing (Schmidt et al., 2010). The proportion is higher in Arabidopsis due to the presence of multiple plant-specific pentatricopeptide repeat (PPR) proteins and/or its larger genome size which may require more proteins to maintain and process. Each PPR protein recognizes and acts on a single site in a specific transcript sequence (Delannoy et al., 2007).

Figure 1.

Overview of the number and abundance of mitochondrial proteins across functional categories. (A) Pie chart showing of functional categories of the confirmed set of 726 mitochondrial proteins (see Table S1B,C in Supplementary Material). A comparison with the more complete yeast mitochondrial proteome shows that similar proportion of proteins involving energy metabolism as well as proteins with unknown functions has been found (Schmidt et al., 2010). In addition, more proteins are involved in mitochondrial genome maintenance (white) in plants (∼20%) than in yeast (∼12%), due to the presence of numerous plant-specific pentatricopeptide repeat (PPR) proteins and a larger genome size. (B) Distribution of the abundance of proteins that can be identified by gel-free MS (Taylor et al., 2011) across seven functional categories.

Several of the unknown proteins identified by our earlier study (Heazlewood et al., 2004) have since been re-assigned as plant-specific components of OXPHOS (Klodmann and Braun, 2011). The most nebulous subset of the known proteome is the more than 18% of the identified proteins that remain without any functional class. However, while this subset are great in number they contribute to <2% of mitochondrial protein abundance. Interestingly, these include a number of plant-specific proteins. It is therefore clear that many more studies are required to elucidate the functions of this subset of proteins which can potentially lead to the discovery of novel plant-specific mitochondrial metabolic pathways/functions.

Protein complexes and interactome

Multiple proteins/isoforms often assembled into large complexes which serve vital metabolic and regulatory roles. While earlier reports have extensively analyzed the structure and function of individual enzyme complexes of interest, such as glycine decarboxylase complex (Douce et al., 2001), it is uncertain whether other mitochondrial proteins could also organize into macromolecular structures. Using 2-D blue-native/SDS-PAGE, Klodmann et al. (2011) found 35 different protein complexes in mitochondria from Arabidopsis cell culture. OXPHOS complexes are amongst the largest and the most abundant protein complexes in mitochondria. Mitochondrial complex assemblies are also dominated by components in the TCA cycle, amino acid metabolism, PPR proteins, and pre-protein import apparatus. While the preliminary compositions of these proteins complexes have been proposed based on the number of subunits identified and their migration on the first and second dimension, they must be verified through independent biochemical analysis.

A number of mitochondrial proteins of diverse function have been identified to interact with metal ions (Tan et al., 2010) and/or have binding affinity with ATP (Ito et al., 2006) in Arabidopsis. In contrast, studies on the more transient direct interactions (functional and physical) between multiple mitochondrial proteins in plants are lacking. Such detailed studies in the future will lead to the construction of plant mitochondrial interactome, to sit alongside side the complexome, and help to define unique metabolic regulations in plants that differentiate them from yeast and mammals.

Post-translational modifications

The complexity of Arabidopsis mitochondrial proteome is further implicated by the dynamic regulation of PTMs which can control activity, stability, and structural characteristics of proteins. Proteins with PTMs often appear as multiple spots with different pI and/or molecular mass on a 2-D gel, and the region of a peptide with modified residues can be detected as an altered m/z ion species by MS. Recent large-scale proteomic studies have reported a number of PTMs in Arabidopsis mitochondrial proteome (Table 1), including oxidation (Tan et al., 2010; Solheim et al., 2012), phosphorylation (Ito et al., 2009; Taylor et al., 2011), S-nitrosylation (Palmieri et al., 2010), N-terminal acetylation (Huang et al., 2009), and lysine acetylation (Finkemeier et al., 2011). However, there appears to be no evidence for specific preference of PTMs to particular functional categories of identified proteins (Table 1), suggesting that PTMs have a wide variety of functional targets in the mitochondrion.

Table 1.

The set of mitochondrial proteins in Arabidopsis with known post-translational modifications.

| AGI accession | Protein ID | PTM | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| OXIDATIVE PHOSPHORYLATION | |||

| AT1G15120 | Complex III QCR6-1, Hinge protein | N-acetylation | Huang et al. (2009) |

| AT1G22840 | Cytochrome | Lys acetylation | Finkemeier et al. (2011) |

| N-acetylation | Huang et al. (2009) | ||

| AT1G47420 | SDH5 succinate dehydrogenase subunit 5 | Phosphorylation | Ito et al. (2009) |

| AT1G51980 | MPP alpha-1 mitochondrial processing peptidase alpha subunit | Oxidation | Solheim et al. (2012) |

| AT3G12260 | NADH dehydrogenase B14 subunit | N-acetylation | Huang et al. (2009) |

| AT3G62810 | Complex 1 family protein/LVR family protein | N-acetylation | Huang et al. (2009) |

| AT4G21105 | COX X4 | Oxidation | Solheim et al. (2012) |

| AT5G08670 | ATP synthase beta subunit | Oxidation | Solheim et al. (2012) |

| AT5G52840 | NADH dehydrogenase B13 subunit | Phosphorylation | Taylor et al. (2011) |

| AT5G66760 | SDH1-1 succinate dehydrogenase flavoprotein subunit | Phosphorylation | Ito et al. (2009) |

| ATMG01190 | ATP synthase alpha-1 subunit | S-Nitrosylation | Palmieri et al. (2010) |

| Oxidation | Solheim et al. (2012) | ||

| PYRUVATE METABOLISM AND TCA CYCLE | |||

| AT1G24180 | E1 alpha-2 (pyruvate dehydrogenase) | Phosphorylation | Ito et al. (2009) |

| AT1G48030 | mtLPD-1 (mtlipoamide dehydrogenase-1) | S-Nitrosylation | Palmieri et al. (2010) |

| Oxidation | Solheim et al. (2012) | ||

| AT1G53240 | Malate dehydrogenase-1 | Oxidation | Solheim et al. (2012) |

| At1G59900 | E1 alpha-1 (pyruvate dehydrogenase) | Phosphorylation | Ito et al. (2009) |

| AT2G05710 | Aconitate hydratase-2 | Phosphorylation | Taylor et al., 2011; ref therein |

| Oxidation | Tan et al. (2010) | ||

| AT2G20420 | Succinyl-CoA ligase (GDP-forming) beta-chain | Oxidation | Solheim et al. (2012) |

| AT3G13930 | E3-1 (dihydrolipoamide dehydrogenase) | Phosphorylation | Taylor et al., 2011; ref therein |

| AT3G15020 | Malate dehydrogenase-2 | Oxidation | Solheim et al. (2012) |

| AT3G17240 | mtLPD-2 (mtlipoamide dehydrogenase-2) | S-Nitrosylation | Palmieri et al. (2010) |

| AT4G26970 | Aconitate hydratase-1 | Oxidation | Tan et al. (2010) |

| AT5G03290 | Isocitrate dehydrogenase-5 | Oxidation | Solheim et al. (2012) |

| TRANSPORT | |||

| AT2G29530 | Translocase inner membrane subunit 10, TIM10 | N-acetylation | Huang et al. (2009) |

| AT3G08580 | AAC1 (ADP/ATP carrier 1) | Oxidation | Solheim et al. (2012) |

| AT3G46560 | Translocase inner membrane subunit 9, TIM9 | N-acetylation | Huang et al. (2009) |

| AT5G13490 | AAC2 (ADP/ATP carrier 2) | Oxidation | Solheim et al. (2012) |

| AT5G14040 | mt phosphate transporter | Oxidation | Solheim et al. (2012) |

| AT5G50810 | Translocase inner membrane subunit 8, TIM8 | N-acetylation | Huang et al. (2009) |

| NUCLEIC ACID PROCESSING AND PROTEIN FOLDING AND STABILITY | |||

| AT1G74230 | GR-RBP5 (glycine-rich RNA-binding protein 5) | Phosphorylation | Ito et al. (2009) |

| AT3G13160 | PPR8-2 | Oxidation | Solheim et al. (2012) |

| AT3G23990 | HSP60-3B | Oxidation | Solheim et al. (2012) |

| AT4G02930 | Elongation factor Tu | Oxidation | Solheim et al. (2012) |

| AT4G26780 | Co-chaperone grpE | Phosphorylation | Ito et al. (2009) |

| AT4G37910 | Heat shock protein HSP70-1 | Phosphorylation | Taylor et al., 2011; ref therein |

| AT5G26860 | LON1 (LON protease 1) | Phosphorylation | Ito et al. (2009) |

| AT5G40770 | Prohibitin-3 | N-acetylation | Huang et al. (2009) |

| AT5G61030 | GR-RBP3 (glycine-rich RNA-binding protein 3) | Phosphorylation | Ito et al. (2009) |

| PHOTORESPIRATION | |||

| AT1G11860 | GDT1 aminomethyltransferase | S-Nitrosylation | Palmieri et al. (2010) |

| Phosphorylation | Taylor et al. (2011) | ||

| AT1G32470 | GDH Glycine decarboxylase H subunit | S-Nitrosylation | Palmieri et al. (2010) |

| Oxidation | Solheim et al. (2012) | ||

| AT2G35370 | GDH Glycine decarboxylase H subunit | S-Nitrosylation | Palmieri et al. (2010) |

| Oxidation | Solheim et al. (2012) | ||

| AT4G33010 | Glycine decarboxylase P-protein 1 | S-Nitrosylation | Palmieri et al. (2010) |

| Oxidation | Solheim et al. (2012) | ||

| AT4G37930 | SHM1 (serine transhydroxymethyltransferase 1) | S-Nitrosylation | Palmieri et al. (2010) |

| Oxidation | Solheim et al. (2012) | ||

| AT5G26780 | SHM2 (serine hydroxymethyltransferase 2) | Oxidation | Solheim et al. (2012) |

| OTHER METABOLISM | |||

| AT3G61440 | Cyanoalanine synthase | Phosphorylation | Taylor et al., 2011; ref therein |

| AT3G22200 | 4-Aminobutyrate aminotransferase | Oxidation | Solheim et al. (2012) |

| AT4G15940 | Fumarylacetoacetate hydrolase family protein | N-acetylation | Huang et al. (2009) |

| AT5G07440 | GDH2 (glutamate dehydrogenase-2) | Phosphorylation | Ito et al. (2009) |

| N-acetylation | Huang et al. (2009) | ||

| Oxidation | Solheim et al. (2012) | ||

| AT5G14780 | FDH Formate dehydrogenase | Phosphorylation | Ito et al. (2009) |

| Oxidation | Solheim et al. (2012) | ||

| AT5G18170 | GDH1 (glutamate dehydrogenase-1) | Phosphorylation | Ito et al. (2009) |

| N-acetylation | Huang et al. (2009) | ||

| AT5G50370 | Adenylate kinase family | Phosphorylation | Taylor et al. (2011) |

| N-acetylation | Huang et al. (2009) | ||

| AT5G63400 | ADK1 Adenylate kinase 1 | N-acetylation | Huang et al. (2009) |

| PROTEINS WITH UNKNOWN FUNCTIONS | |||

| AT2G39795 | mt glycoprotein family protein | Phosphorylation | Ito et al. (2009) |

| AT3G18240 | Unknown protein | Phosphorylation | Ito et al. (2009) |

| AT3G55605 | Mitochondrial glycoprotein family protein | Phosphorylation | Ito et al. (2009) |

| AT4G21460 | Unknown protein | Phosphorylation | Ito et al. (2009) |

| AT4G27585 | Stomatin-like protein | Phosphorylation | Ito et al. (2009) |

| AT4G23885 | Unknown protein | N-acetylation | Huang et al. (2009) |

PTM, post-translational modification(s).

The total number of identified proteins with PTMs is very likely a gross underestimation due to a number of technical challenges, such as the loss of PTMs during mitochondrial purification procedures and the relatively low abundance of the modified peptides compared to their unmodified counterparts. Also, it is not clear how many proteins, including those listed in Table 1, are functionally modified through enzyme-catalyzed mitochondrial processes in vivo. For example, degradation products observed on a 2-D gel often perceive as artificial post-purification events. These concerns can be at least partially overcome by enrichment of modified peptides/proteins and/or repeat analysis of multiple replicates to ensure that similar changes can be observed in all samples. Alternatively, the incorporation of radioactive tracers into proteins in vivo (cells) or in vitro (isolated mitochondria) can be used to identify proteins with reversible PTMs. For instance, 18 phosphoproteins have recently been identified by [γ32P]-ATP labeling and affinity enrichment of isolated mitochondria (Ito et al., 2009).

Changes in the Mitochondrial Proteome in Different Tissues and in Response to Oxidative Stress

The mitochondrial proteome is not static, but has many components that are dynamically regulated in order to meet energy and metabolic needs required by the cell in response to developmental and/or environmental changes. There are many different cell/tissue/organ types which have functions that are unique to plants. Thus, mitochondrial composition, metabolism, and stress response in these cells/tissues/organs from Arabidopsis will be different from what has been observed in yeast and animals.

Analysis of the mitochondria proteome from photosynthetic shoots, non-photosynthetic cell culture, and roots identified major differences in the abundance of enzymes of the TCA cycle and photorespiration (Lee et al., 2008, 2011). Quantitative comparison of the mitochondrial proteome across 10 different time points covering 24-h of the life of Arabidopsis shoots also uncovers day (photosynthetic)- and night (non-photosynthetic)-enhanced proteins in central carbon metabolism (Lee et al., 2010). In these studies, the abundances of OXPHOS complexes in purified mitochondria generally remain unaltered but their respiratory capacity differs depending on the choice and/or availability of substrates (Lee et al., 2008, 2011). However, on a whole tissue basis differences in mitochondrial electron transport chain complex ratios between tissues has been reported (Peters et al., 2012). Lee et al. (2012) have reported changes in the isolated Arabidopsis mitochondrial proteome beyond differences in the cellular photosynthetic capacity. Changes in the abundance of a wide variety of mitochondrial proteins can be observed from cells/tissues from various vegetative and reproductive phases of development. Differences in protein accumulation and metabolic specializations of these mitochondria generally coincide with the main physiological role of each corresponding tissue type, such as glycine cleavage via photorespiration in shoot and maintenance of mitochondrial redox environment in flowers. In mouse, it has been reported that just over half of all proteins identified by gel-free MS approach can be found in all the investigated organs (Pagliarini et al., 2008). However, the number of mitochondrial proteins that are highly tissue-specific (i.e., totally absent in at least one tissue) in Arabidopsis remains to be defined. Such analysis will assist in identifying mitochondrial components that causes plant-specific developmental phenotypes, e.g., cytoplasm male sterility.

Using a gel-free quantitative MS approach, Tan et al. (2012) recently identify a number of integral membrane proteins in mitochondria that are altered in abundance in response to cold and/or various chemical stresses. These proteins include the components of the alternative NADH dehydrogenases, alternative oxidase, and uncoupling proteins, but also several stress-sensitive subunits within the OXPHOS complexes. Together with a similar study by Sweetlove et al. (2002), it is concluded that the reduction in respiration in response to chemical-induced oxidative stress is a consequence of coordinated changes in the mitochondrial proteome, particularly OXPHOS complex subunits and stress-related components.

Application of Proteomics to Analyze Mitochondrial Protein Functions

Over the last decade, advances in the understanding of mitochondrial composition and protein complex assembly have led to the identification of many genes associated with genetic diseases in humans (Calvo and Mootha, 2010). In contrast, plant proteomics still needs to discover novel mitochondrial components that are associated with known developmental defects in plants. Nevertheless, by combining proteomics and reverse-genetics strategies, a number of recent studies have highlighted the unique role of a mitochondrial component of interest in Arabidopsis that had not been unraveled by other biochemical and molecular techniques. Metabolite analyses of malate dehydrogenase (MDH) antisense and knockout lines in tomato and Arabidopsis respectively show an elevated foliar ascorbate level (Nunes-Nesi et al., 2005; Tomaz et al., 2010). Such accumulation coincides with the reduction of Complex I-associated galacton-1,4-lactone dehydrogenase (GLDH) abundance in the mitochondrial proteome of a MDH double mutant (mmdh1mmdh2; Tomaz et al., 2010), indicating that there might be a complex metabolic regulation/interaction between OXPHOS, TCA cycle, and cellular ascorbate biosynthesis. A mutation in mitochondrial Lon protease leads to a retarded growth phenotype (Rigas et al., 2009), which can be explained by an altered abundance of enzymes in the TCA cycle and OXPHOS, a decrease in the abundance of breakdown products and a small increase in the number of proteins with oxidized peptides, but not by heightened oxidative stress (Solheim et al., 2012). In contrast, knockout of the protease AtFtsH4 does not significantly affect Arabidopsis growth under long day conditions, but changes rosette development under short-day conditions (Gibala et al., 2009). The phenotypes correlate with elevated levels of oxidative stress, increased abundance of Hsp70 and prohibitins, and decreased abundance of ATP synthase subunits.

Conclusion and Perspectives

The availability of the full genome sequence of Arabidopsis for more than a decade, advances in various proteomic technologies, as well as their wider adoption, have provided an opportunity to understand the protein make-up of mitochondria and their underlying metabolism in this plant more than in any other. Significant progress in extracting information on PTMs and protein abundances has also improved our insight into the dynamic regulation of the mitochondrial proteome in a cellular/organismal context. However, further work is needed to characterize mitochondrial proteins according to their sub-organellar localization. In-depth identification of components in the intermembrane space has not been reported since the improvements in MS analysis in recent years. Recent discoveries of a pyruvate transporter (Herzig et al., 2012) and a calcium uniporter (Baughman et al., 2011) in mouse mitochondria have been conducted through an integrated proteomics, bioinformatics, and genetics strategy. Thus, identification of low abundance proteins should allow us to complete the catalog of mitochondrial proteins in Arabidopsis, which will provide us several candidates for identifying plant-specific transporters or metabolic pathways by a similar approach.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at http://www.frontiersin.org/Plant_Proteomics/10.3389/fpls.2013.00004/abstract

Mitochondrial proteins identified by mass spectrometry or fluorescent protein localization studies. (A) All proteins identified from isolated mitochondria from Arabidopsis using proteomics in the last 5 years. (B) A set of proteins which has a high probably being located in the mitochondrion. For the inclusion of a protein in the list, it should meet the following criteria: (i) A protein is automatically considered mitochondrial if at least two studies have identified it in isolated mitochondrial fraction. However, a protein is considered to be non-mitochondrial if it is identified in equal number of or more non-mitochondrial proteomics studies than the mitochondrial ones. (ii) If the location of a protein is verified independently by fluorescent protein localization analysis, then (ii) is ignored and it is included in the list. (iii) If a protein is identified by one study, the localization based on SUBAcon score and/or ARAMEMNON localization consensus score is also considered. (C) Mitochondrial protein confirmed through fluorescent protein localization studies (according to SUBA) only and not by proteomics.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded through a grant to the ARC Centre of Excellence in Plant Energy Biology (CE0561495; A. Harvey Millar). A. Harvey Millar is funded as an ARC Australian Future Fellow (FT110100242) and Chun Pong Lee is a receipt of an EMBO Fellowship (ALTF1140-2011).

References

- Baughman J. M., Perocchi F., Girgis H. S., Plovanich M., Belcher-Timme C. A., Sancak Y., et al. (2011). Integrative genomics identifies MCU as an essential component of the mitochondrial calcium uniporter. Nature 476, 341–345 10.1038/nature10234 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calvo S. E., Mootha V. K. (2010). The mitochondrial proteome and human disease. Annu. Rev. Genomics Hum. Genet. 11, 25–44 10.1146/annurev-genom-082509-141720 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chenau J., Michelland S., Sidibe J., Seve M. (2008). Peptides OFFGEL electrophoresis: a suitable pre-analytical step for complex eukaryotic samples fractionation compatible with quantitative iTRAQ labeling. Proteome Sci. 6, 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui J., Liu J., Li Y., Shi T. (2011). Integrative identification of Arabidopsis mitochondrial proteome and its function exploitation through protein interaction network. PLoS ONE 6:e16022. 10.1371/journal.pone.0016022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delannoy E., Stanley W. A., Bond C. S., Small I. D. (2007). Pentatricopeptide repeat (PPR) proteins as sequence-specificity factors in post-transcriptional processes in organelles. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 35, 1643–1647 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Douce R., Bourguignon J., Neuburger M., Rébeillé F. (2001). The glycine decarboxylase system: a fascinating complex. Trends Plant Sci. 6, 167–176 10.1016/S1360-1385(01)01892-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dudkina N. V., Kouril R., Peters K., Braun H.-P., Boekema E. J. (2010). Structure and function of mitochondrial supercomplexes. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1797, 664–670 10.1016/j.bbabio.2009.12.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan O., Taylor N. L., Carrie C., Eubel H., Kubiszewski-Jakubiak S., Zhang B., et al. (2011). Multiple lines of evidence localize signaling, morphology, and lipid biosynthesis machinery to the mitochondrial outer membrane of Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 157, 1093–1113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkemeier I., Laxa M., Miguet L., Howden A. J. M., Sweetlove L. J. (2011). Proteins of diverse function and subcellular location are lysine acetylated in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 155, 1779–1790 10.1104/pp.110.171595 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forner F., Kumar C., Luber C. A., Fromme T., Klingenspor M., Mann M. (2009). Proteome differences between brown and white fat mitochondria reveal specialized metabolic functions. Cell Metab. 10, 324–335 10.1016/j.cmet.2009.08.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fröhlich A., Gaupels F., Sarioglu H., Holzmeister C., Spannagl M., Durner J., et al. (2012). Looking deep inside: detection of low-abundance proteins in leaf extracts of Arabidopsis and phloem exudates of pumpkin. Plant Physiol. 159, 902–914 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibala M., Kicia M., Sakamoto W., Gola E. M., Kubrakiewicz J., Smakowska E., et al. (2009). The lack of mitochondrial AtFtsH4 protease alters Arabidopsis leaf morphology at the late stage of rosette development under short-day photoperiod. Plant J. 59, 685–699 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2009.03907.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heazlewood J. L., Tonti-Filippini J. S., Gout A. M., Day D. A., Whelan J., Millar A. H. (2004). Experimental analysis of the Arabidopsis mitochondrial proteome highlights signaling and regulatory components, provides assessment of targeting prediction programs, and indicates plant-specific mitochondrial proteins. Plant Cell 16, 241–256 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heazlewood J. L., Verboom R. E., Tonti-Filippini J., Small I., Millar A. H. (2007). SUBA: the Arabidopsis subcellular database. Nucleic Acid Res. 35, D213–D218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herzig S., Raemy E., Montessuit S., Veuthey J.-L., Zamboni N., Westermann B., et al. (2012). Identification and functional expression of the mitochondrial pyruvate carrier. Science 337, 93–96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang S., Taylor N. L., Whelan J., Millar A. H. (2009). Refining the definition of plant mitochondrial presequences through analysis of sorting signals, N-terminal modifications, and cleavage motifs. Plant Physiol. 150, 1272–1285 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito J., Batth T. S., Petzold C. J., Redding-Johanson A. M., Mukhopadhyay A., Verboom R., et al. (2011). Analysis of the Arabidopsis cytosolic proteome highlights subcellular partitioning of central plant metabolism. J. Proteome Res. 10, 1571–1582 10.1021/pr200437v [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito J., Heazlewood J. L., Millar A. H. (2006). Analysis of the soluble atp-binding proteome of plant mitochondria identifies new proteins and nucleotide triphosphate interactions within the matrix. J. Proteome Res. 5, 3459–3469 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito J., Heazlewood J. L., Millar A. H. (2007). The plant mitochondrial proteome and the challenge of defining the posttranslational modifications responsible for signalling and stress effects on respiratory functions. Physiol. Plant. 129, 207–224 [Google Scholar]

- Ito J., Taylor N. L., Castleden I., Weckwerth W., Millar A. H., Heazlewood J. L. (2009). A survey of the Arabidopsis thaliana mitochondrial phosphoproteome. Proteomics 9, 4229–4240 10.1002/pmic.200900064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klodmann J., Braun H.-P. (2011). Proteomic approach to characterize mitochondrial complex I from plants. Phytochemistry 72, 1071–1080 10.1016/j.phytochem.2010.11.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klodmann J., Senkler M., Rode C., Braun H.-P. (2011). Defining the protein complex proteome of plant mitochondria. Plant Physiol. 157, 587–598 10.1104/pp.111.182352 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klodmann J., Sunderhaus S., Nimtz M., Jänsch L., Braun H.-P. (2010). Internal architecture of mitochondrial complex I from Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell 22, 797–810 10.1105/tpc.109.073726 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kruft V., Eubel H., Jaensch L., Werhahn W., Braun H.-P. (2001). Proteomic approach to identify novel mitochondrial proteins in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 127, 1694–1710 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee C. P., Eubel H., Millar A. H. (2010). Diurnal changes in mitochondrial function reveal daily optimization of light and dark respiratory metabolism in Arabidopsis. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 9, 2125–2139 10.1074/mcp.M110.001214 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee C. P., Eubel H., O’Toole N., Millar A. H. (2008). Heterogeneity of the mitochondrial proteome for photosynthetic and non-photosynthetic Arabidopsis metabolism. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 7, 1297–1316 10.1074/mcp.M700535-MCP200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee C. P., Eubel H., O’Toole N., Millar A. H. (2011). Combining proteomics of root and shoot mitochondria and transcript analysis to define constitutive and variable components in plant mitochondria. Phytochemistry 72, 1092–1108 10.1016/j.phytochem.2010.12.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee C. P., Eubel H., Solheim C., Millar A. H. (2012). Mitochondrial proteome heterogeneity between tissues from the vegetative and reproductive stages of Arabidopsis thaliana development. J. Proteome Res. 11, 3326–3343 10.1021/pr3004166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L., Nelson C. J., Solheim C., Whelan J., Millar A. H. (2012). Determining degradation and synthesis rates of Arabidopsis proteins using the kinetics of progressive 15N labeling of two-dimensional gel-separated protein spots. Mol. Cell Proteomics 11, M111.010025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livaja M., Palmieri M. C., von Rad U., Durner J. (2008). The effect of the bacterial effector protein harpin on transcriptional profile and mitochondrial proteins of Arabidopsis thaliana. J. Proteomics 71, 148–159 10.1016/j.jprot.2008.04.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millar A. H., Heazlewood J. L. (2003). Genomic and proteomic analysis of mitochondrial carrier proteins in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 131, 443–453 10.1104/pp.009985 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millar A. H., Heazlewood J. L., Kristensen B. K., Braun H.-P., Moller I. M. (2005). The plant mitochondrial proteome. Trends Plant Sci. 10, 36–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millar A. H., Sweetlove L. J., Giege P., Leaver C. J. (2001). Analysis of the Arabidopsis mitochondrial proteome. Plant Physiol. 127, 1711–1727 10.1104/pp.010387 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millar A. H., Whelan J., Soole K. L., Day D. A. (2011). Organization and regulation of mitochondrial respiration in plants. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 62, 79–104 10.1146/annurev-arplant-042110-103857 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nunes-Nesi A., Carrari F., Lytovchenko A., Smith A. M., Loureiro M. E., Ratcliffe R. G., et al. (2005). Enhanced photosynthetic performance and growth as a consequence of decreasing mitochondrial malate dehydrogenase activity in transgenic tomato plants. Plant Physiol. 137, 611–622 10.1104/pp.104.055566 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Padmasree K., Padmavathi L., Raghavendra A. S. (2002). Essentiality of mitochondrial oxidative metabolism for photosynthesis: optimization of carbon assimilation and protection against photoinhibition. Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 37, 71–119 10.1080/10409230290771465 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pagliarini D. J., Calvo S. E., Chang B., Sheth S. A., Vafai S. B., Ong S. E., et al. (2008). A mitochondrial protein compendium elucidates complex I disease biology. Cell 134, 112–123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmieri M. C., Lindermayr C., Bauwe H., Steinhauser C., Durner J. (2010). Regulation of plant glycine decarboxylase by S-nitrosylation and glutathionylation. Plant Physiol. 152, 1514–1528 10.1104/pp.109.152579 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters K., Nießen M., Peterhänsel C., Späth B., Hölzle A., Binder S., et al. (2012). Complex I-complex II ratio strongly differs in various organs of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Mol. Biol. 79, 273–284 10.1007/s11103-012-9911-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinders J., Zahedi R. P., Pfanner N., Meisinger C., Sickmann A. (2006). Toward the complete yeast mitochondrial proteome: multidimensional separation techniques for mitochondrial proteomics. J. Proteome Res. 5, 1543–1554 10.1021/pr050350q [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rigas S., Daras G., Laxa M., Marathias N., Fasseas C., Sweetlove L. J., et al. (2009). Role of Lon1 protease in post-germinative growth and maintenance of mitochondrial function in Arabidopsis thaliana. New Phytol. 181, 588–600 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2008.02701.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schertl P., Sunderhaus S., Klodmann J., Grozeff G. E. G., Bartoli C. G., Braun H.-P. (2012). l-Galactono-1,4-lactone dehydrogenase (GLDH) forms part of three subcomplexes of mitochondrial complex I in Arabidopsis thaliana. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 14412–14419 10.1074/jbc.M111.305144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt O., Pfanner N., Meisinger C. (2010). Mitochondrial protein import: from proteomics to functional mechanisms. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 11, 655–667 10.1038/nrm2959 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwacke R., Schneider A., van der Graaff E., Fischer K., Catoni E., Desimone M., et al. (2003). ARAMEMNON, a novel database for Arabidopsis integral membrane proteins. Plant Physiol. 131, 16–26 10.1104/pp.011577 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwanhausser B., Busse D., Li N., Dittmar G., Schuchhardt J., Wolf J., et al. (2011). Global quantification of mammalian gene expression control. Nature 473, 337–342 10.1038/nature10098 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solheim C., Li L., Hatzopoulos P., Millar A. H. (2012). Loss of Lon1 in Arabidopsis changes the mitochondrial proteome leading to altered metabolite profiles and growth retardation without an accumulation of oxidative damage. Plant Physiol. 160, 1187–1203 10.1104/pp.112.203711 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sweetlove L. J., Heazlewood J. L., Herald V., Holtzapffel R., Day D. A., Leaver C. J., et al. (2002). The impact of oxidative stress on Arabidopsis mitochondria. Plant J. 32, 891–904 10.1046/j.1365-313X.2002.01474.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan Y.-F., Millar A. H., Taylor N. L. (2012). Components of mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation vary in abundance following exposure to cold and chemical stresses. J. Proteome Res. 11, 3860–3879 10.1021/pr3003535 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan Y.-F., O’Toole N., Taylor N. L., Millar A. H. (2010). Divalent metal ions in plant mitochondria and their role in interactions with proteins and oxidative stress-induced damage to respiratory function. Plant Physiol. 152, 747–761 10.1104/pp.109.147942 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor N. L., Heazlewood J. L., Millar A. H. (2011). The Arabidopsis thaliana 2-D gel mitochondrial proteome: Refining the value of reference maps for assessing protein abundance, contaminants and post-translational modifications. Proteomics 11, 1720–1733 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Arabidopsis Genome Initiative. (2000). Analysis of the genome sequence of the flowering plant Arabidopsis thaliana. Nature 408, 796–815 10.1038/35048692 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomaz T., Bagard M., Pracharoenwattana I., Lindén P., Lee C. P., Carroll A. J., et al. (2010). Mitochondrial malate dehydrogenase lowers leaf respiration and alters photorespiration and plant growth in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 154, 1143–1157 10.1104/pp.110.161612 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unseld M., Marienfeld J. R., Brandt P., Brennicke A. (1997). The mitochondrial genome of Arabidopsis thaliana contains 57 genes in 366,924 nucleotides. Nat. Genet. 15, 57–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werhahn W., Braun H.-P. (2002). Biochemical dissection of the mitochondrial proteome from Arabidopsis thaliana by three-dimensional gel electrophoresis. Electrophoresis 23, 640–646 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Mitochondrial proteins identified by mass spectrometry or fluorescent protein localization studies. (A) All proteins identified from isolated mitochondria from Arabidopsis using proteomics in the last 5 years. (B) A set of proteins which has a high probably being located in the mitochondrion. For the inclusion of a protein in the list, it should meet the following criteria: (i) A protein is automatically considered mitochondrial if at least two studies have identified it in isolated mitochondrial fraction. However, a protein is considered to be non-mitochondrial if it is identified in equal number of or more non-mitochondrial proteomics studies than the mitochondrial ones. (ii) If the location of a protein is verified independently by fluorescent protein localization analysis, then (ii) is ignored and it is included in the list. (iii) If a protein is identified by one study, the localization based on SUBAcon score and/or ARAMEMNON localization consensus score is also considered. (C) Mitochondrial protein confirmed through fluorescent protein localization studies (according to SUBA) only and not by proteomics.