Abstract

Study Design

Controlled laboratory study.

Objective

To investigate the in vivo biomechanical effect of degenerative lumbar spondylolisthesis (DLS) on the motion of the facet joint during various functional weight-bearing activities.

Summary of Background Data

Although the morphological changes of the facet joints in patients with DLS have been reported in a few studies, no data has been reported on the kinematics of these facet joints.

Methods

Ten patients with DLS at L4–L5 were studied. Each patient underwent a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan to obtain three-dimensional (3D) models of the lumbar vertebrae from L2–L5 as well as a dual fluoroscopic imaging scan in different postures: flexion-extension, left-right bending and left-right torsion. The positions of the vertebrae were reproduced by matching the MRI-based vertebral models to the fluoroscopic images. The kinematics of the facet joint and the ranges of motion (ROMs) were compared with those of healthy subjects and those of patients with degenerative disc diseases (DDD) previously published.

Results

In DLS patients, the range of rotation of the facet joints was significantly less at the DLS level (L4–L5) than that at the adjacent levels (L2–L3 and L3–L4), while the range of translation was similar at all levels. The range of rotation at the facet joints of the DLS level decreased compared to those of both the DDD patients and healthy subjects at the corresponding vertebral level (L4–L5), while no significant difference was found in the range of translation. The ROM of facet joints in DLS and in DDD patients was similar at the adjacent levels (L2–L3 and L3–L4).

Conclusion

The range of rotation decreased at the facet joints at the DLS level (L4–L5) in patients compared to those in healthy subjects and DDD patients. This decrease in range of rotation implies that the DLS disease may cause restabilization of the joint. The data may help the selection of conservative treatment or different surgical techniques for the DLS patients.

Keywords: Degenerative lumbar spondylolisthesis, facet joint kinematics, facet orientation, facet joint osteoarthritis, disc degeneration

INTRODUCTION

Degenerative lumbar spondylolisthesis (DLS) is characterized as the slipping forward of one lumbar vertebra on another with an intact neutral arch. DLS is most commonly seen at the L4–L5 level and affects women more frequently than men 1, 2. Patients with DLS may suffer from low back pain and other related disabilities 3. Numerous surgical techniques have been used to treat DLS patients, including decompression, decompression and fusion (with or without an interbody device)4, and most recently, interspinous spacer devices5. Lumbar facet joints play an important role in stabilizing the segmental spine unit 6. Slippage of the vertebrae occurs when the locking mechanism of the facet joint fails7. Therefore, an objective evaluation of the biomechanical functions of the facet joints in DLS patients is critical for improvement of the surgical treatment techniques.

Both kinematics and morphological changes in the facet joints have been related to DLS8–14. Several radiographic studies have indicated a correlation between DLS and an increased sagittal orientation of the facet joints at L4–L5 segment8, 9. These studies have demonstrated that the pedicle-facet angle, W-shaped facet joint10, facet joint osteoarthritis11, the presence of synovial cysts12, increased fluid signal of the facet joint 13 and facet joint fusion 14 are all linked to DLS. Few studies have used cadaveric specimens or animal models to examine the motion characteristics of normal facet joints15, 16. The kinematics of the facet joints were also measured using computed tomography (CT) 17 and kinematic magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) 18 in living human subjects. However, little is known about the kinematics response of the facet joint in pathological spine19. There is no study reporting on the motion of facet joints in patients with DLS.

Recently, we validated a combined dual fluoroscopic imaging system (DFIS) to investigate in vivo motion of the lumbar spine, including the facet joints of healthy participants20 and DDD patients21. The system was shown to be robust for investigation of spine kinematics motion during weight-bearing, functional activities. The purpose of this study was to use the DFIS to investigate the 6 degree-of –freedom (DOF) motion of the lumbar facet joint of DLS patients. We hypothesized that the facet joints at the DLS level would demonstrate distinct alterations in motion characteristics during in vivo activities in comparison to those of the healthy participants and DDD patients.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patient Characteristics

Ten patients diagnosed with L4–L5 DLS (3 men and 7 women; mean age = 72.6 years; mean height = 162.2 cm; mean weight = 65.2 kg) were recruited from a single academic center. Based on the clinical and radiographic assessments, we graded the vertebral slippage of all patients as I using the Meyerding classification method22. Degeneration of the disc was graded using Pfirrmann classification23 and facet joints was graded using Weishaupt scale24(Table 1).

Table 1.

Mean Facet Joint Osteoarthritis and Disc Degeneration among normal Participants, DDD, and DLS

| Level | Group | Disc Degeneration | Range of grade | Left facet joint | Range of grade | Right facet joint | Range of grade |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L2–L3 | Normal | 1.1(0.4) | 1–2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| DDD | 1.4(0.5) | 1–2 | 0.8(0.5) | 0–1 | 0.8(0.5) | 0–1 | |

| DLS | 2.4(0.7) | 1–3 | 1.4(0.7) | 0–2 | 1.3(0.7) | 0–2 | |

| L3–L4 | Normal | 1.6(0.5) | 1–3 | 0.1(0.4) | 0–1 | 0 | 0 |

| DDD | 1.6(0.8) | 1–3 | 0.8(0.5) | 0–1 | 0.8(0.5) | 0–1 | |

| DLS | 2.6(1.1) | 2–4 | 1.6(0.5) | 1–2 | 1.5(0.5) | 1–2 | |

| L4–L5 | Normal | 1.9(0.6) | 1–3 | 0.1(0.4) | 0–1 | 0.1(0.4) | 0–1 |

| DDD | 4.2(0.8) | 3–5 | 2.5(0.8) | 1–3 | 2.4(0.7) | 1–3 | |

| DLS | 4.7(0.8) | 4–5 | 2.8(0.5) | 1–3 | 2.6(0.5) | 1–3 |

Normal=normal subject (N=8)

DDD=degenerative Disc Disease (N=10)

DLS=degenerative lumbar spondylolisthesis (N=10)

The value were presented as mean (SD)

Ten DDD patients (7 men and 3 women; mean age = 51.8 years; mean height= 169 cm, mean weight= 65.7kg) and eight healthy participants (3 male and 5 female participant; mean age=54.4years; mean height= 163.5cm; mean weight =63.5kg) tested in our previous studies were used as comparison controls. We also graded the lumbar discs and the facet joints of the healthy participants and DDD patients using the Pfirmann classification and Weishaupt scales. (Table 1)

Approval by our institutional review board for this study was obtained prior to the initiation of this study. We obtained informed consent from each patient before any testing was performed.

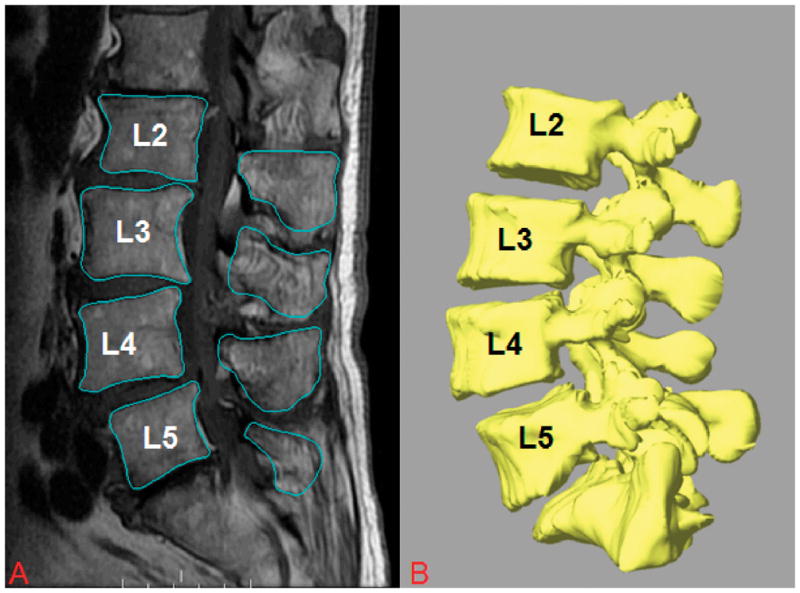

Imaging technique

Each patient was scanned using a 3-T MRI scanner (Siemens Medical Solutions MAGNETOM Trio) with a spine surface coil and a T2-weighted fat-suppressed 3-D spoiled gradient recalled sequence. The MR images of the spinal segments were then imported into a solid modeling software (Rhinoceros® Robert McNeel & Associates, Seattle, Washington) to construct 3-D anatomical vertebral models of L2-L5 using a protocol established in our laboratory19, 25(Figure 1A). Mesh models of the vertebrae were created from bony contours (Figure 1B).

Fig. 1.

A, Digitized contours of lumbar vertebrae of patients with DLS at L4–L5 in the sagittal plane. B, Three-dimensional anatomical vertebral model of L2–L5, constructed from the magnetic resonance imaging.

The lumbar spine of each patient was imaged with different poses of the body using a dual fluoroscopic imaging system (DFIS) (Figure 2A, B). The subject was asked to stand to position the lumbar spine within the views of the two fluoroscopes, and to actively move into different poses: standing position, maximum trunk flexion-extension, maximum left-right bending, and maximum left-right torsion. The subject was asked to hold each pose for about 1 second while the two fluoroscopes took simultaneous images from two orthogonal directions. The poses were monitored by an orthopedic surgeon to reduce variation. Every subject was asked to minimize his/her hip motions to maximize lumbar spine motion.

Fig. 2.

A, The experimental setup of the dual fluoroscopic imaging system(DFIS) for capturing the lumbar spine positions of living subjects. B, Virtual reproduction of the DFIS and the vertebral positions..

Lumbar facet joint motion

The in vivo positions of the vertebrae at various weight-bearing body positions were reproduced in the Rhinoceros modeling software using the MRI-based 3D models and the previously captured pair of orthogonal fluoroscopic images of the vertebrae. The 3D vertebral models were introduced into the virtual fluoroscopic system and viewed from the perspectives of the 2 virtual fluoroscopes. A model of the vertebrae can be independently translated and rotated in 6DOF until its outline matches the osseous outlines captured on the fluoroscopic images19, 25. Using this technique, we reproduced the vertebral positions during in vivo weight-bearing activities at each selected pose. The accuracy of the technique has been validated to be 0.3 mm and 0.7° in determination of in-vivo spinal translation and rotation25.

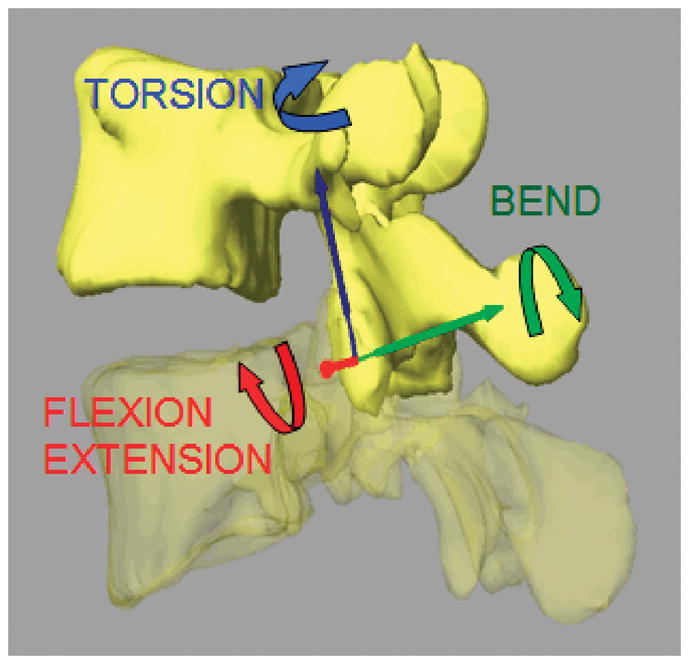

Right-hand Cartesian coordinate systems were created to quantify the 6DOF motions of the facet joints. The origin of the coordinate system was designated at the volumetric center of the facet joint (Figure 3). The x-axis, set perpendicular to the joint surface, represented the mediolateral direction. The z-axis, set in the plane parallel to the facet sliding surface and along the long axis of the facet joint, represented the craniocaudal direction. The y-axis, set in the sagittal plane perpendicular to the z-x plane, represented the anterior-posterior direction. The same coordinate systems were adopted for both the inferior facet of cranial vertebra and the superior facet of the caudal vertebra at the standing position such that the standing position was used as a reference position. After reproducing the in vivo vertebral positions using the 3D anatomic vertebral models, the kinematics of the facet joints at different body positions was directly measured from the coordinated system of the inferior facet joint with respect to that of the superior facet joint. The ranges of motion (ROMs) of the facet joints were then determined during the flexion-extension, left-right bending, and left-right torsion of the body.

Fig. 3.

Anatomic coordinate system to measure kinematics of the facet joints.

Facet orientation

The transverse and longitudal angles of the facet joints were measured in relation to the midsagittal plane of the vertebral body. The orientation and inclination of the facet joints were measured using the method described in the literature 20, 26, 27 (Figure 4, 5). The transverse facet angle was defined as the angle between the projection of the line representing the facet width onto the transverse plane and the anteroposterior axis of the vertebra. The longitudinal facet angle was defined as the angle between the projection of the line representing the facet length onto the sagittal plane and the line of the craniocaudal axis of the vertebra.

Fig. 4.

The transverse facet angle was defined as the angle between the projection of the line representing the facet width onto the transverse plane and the anteroposterior axis of the vertebra.

Fig. 5.

The longitudinal facet angle was defined as the angle between the projection of the line representing the facet length onto the sagittal plane and the line of the craniocaudal axis of the vertebra.

Statistical analysis

Two-way repeated measures ANOVA were used to compare the facet ROM and facet orientation at L2–L3, L3–L4 and L4–L5 vertebral levels within each group. A multiway ANOVA was used to compare the kinematics among the healthy subjects, DDD and DLS patients. The subject group was the categorical factor. The vertebral level and the activity were the dependent variables. The level of significance was set at P<0.05. When a statistically significant difference was detected, a Newman-Keuls post hoc test was performed. The statistical analysis was performed using the Statistica software (StatSoft version 8.0, Tulsa, Ok).

RESULTS

ROMs of facet joints in DLS patients (Table 2)

Table 2.

Comparison of Translation Ranges Among normal Participants, DDD, and DLS

| L2–L3 | L3–L4 | L4–L5 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ML | AP | CC | ML | AP | CC | ML | AP | CC | |

| Left-right torsion | |||||||||

| Normal | 1.2(0.7) | 1.1(0.8) | 1.2(0.6) | 1.3(0.8) | 1.1(1.0) | 1.4(0.9) | 2.2(0.6) | 1.3(0.7) | 2.3(1.0) |

| DDD | 1.2(0.9) | 1.5(0.8) | 1.5(1.4) | 1.9(1.1) | 0.8(0.8) | 1.7(1.3) | 2.5(1.4) | 1.5(1.1) | 1.7(1.5) |

| DLS | 1.8(1.0) | 1.1(1.0) | 1.6(1.3) | 1.5(1.3) | 1.2(0.7) | 1.3(0.7) | 2.5(1.0) | 1.6(0.5) | 1.6(1.4) |

| Left-right bending | |||||||||

| Normal | 1.0(0.7) | 1.3(0.8) | 1.5(1.4) | 1.5(1.3) | 1.4(1.1) | 1.4(0.9) | 1.6(1.2) | 1.5(1.1) | 1.7(1.4) |

| DDD | 0.8(0.7) | 1.0(0.7) | 2.0(1.8) | 1.9(1.7) | 1.2(0.7) | 2.0(1.9) | 1.8(1.2) | 1.4(1.2) | 2.0(1.6) |

| DLS | 1.4(0.6) | 1.5(0.8) | 1.5(0.7) | 2.1(1.8) | 1.6(0.7) | 1.4(0.9) | 2.5(1.5) | 2.0(1.6) | 1.5(0.9) |

| Flexion-extension | |||||||||

| Normal | 1.2(0.7) | 1.3(0.6) | 3.6(2.4) | 1.4(0.9) | 1.3(1.0) | 4.1(1.4) | 1.8(1.1) | 1.3(0.9) | 2.4(1.4) |

| DDD | 1.4(0.7) | 1.2(0.5) | 2.6(2.2) | 2.2(1.7) | 1.3(1.2) | 2.4(2.0) | 2.1(1.5) | 1.0(0.9) | 3.2(1.7) |

| DLS | 1.7(1.0) | 1.4(1.2) | 2.3(1.5) | 1.6(1.4) | 2.3(1.3) | 2.6(1.8) | 2.2(1.5) | 1.6(1.0) | 3.3(1.1) |

Translation around axis: ML, AP and CC.

The values were presented as mean (SD) in millimeter.

ML, mediolateral; AP, indicate anterioposterior; CC, craniocaudal.

DDD=degenerative disc disease, DLS=degenerative lumbar spondylolisthesis, Normal=normal subject

Flexion-extension of the trunk

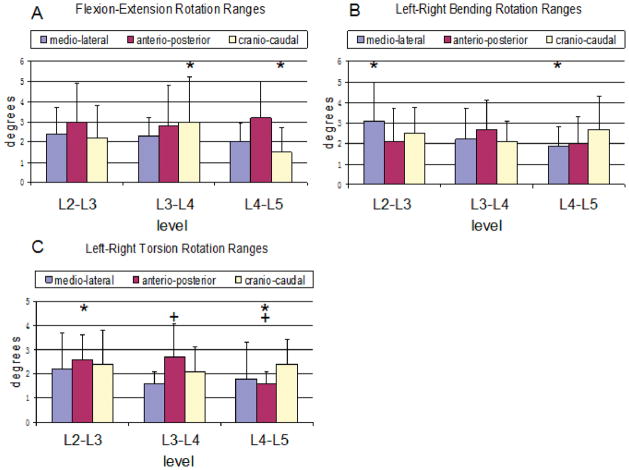

The average range of rotation around all three axes varied from 1.5° to 3.2° at the DLS levels (L4–L5) and 2.2° to 3.0° at the adjacent levels (L2–L3 and L3–L4). The range of coupled rotation along the craniocaudal (z-) axis at the DLS level was significantly less than in the L3–L4 level (P=0.044) (Figure 6A).

Fig. 6.

Range of facet joint rotations in patients with DLS around three principal axes under (A) torsion, (B) bending, and (C) flexion of the torso. The symbols (*,+) represent statistical significance upon between level comparison (P<0.05).

The average range of translation along all three axes varied from 1.6 to 3.3 mm at the DLS level and 1.4 to 2.6 mm at adjacent levels. Vertebral translations during flexion-extension were not significantly different between the studied levels. (Table 2)

Left-right bending of the trunk

The average range of rotation around all three axes varied from 1.9° to 2.7° at the DLS levels (L4–L5) and 2.1° to 3.1° at the adjacent levels (L2–L3 and L3–L4). The range of coupled rotation along the mediolateral (x-) axis was significantly less at the DLS level than in the adjacent L2–L3 level (P=0.05) (Figure 6B).

The average range of translation along all three axes varied from 1.5 to 2.5 mm at the DLS level and 1.4 to 2.1 mm at adjacent levels. Vertebral translations during left-right torsion were not significantly different between the studied levels. (Table 2)

Left-right torsion of the trunk

The average range of rotation around all three axes varied from 1.6° to 2.4° at the DLS levels (L4–L5) and 1.6° to 2.7° at the adjacent levels (L2–L3 and L3–L4). The range of coupled rotation along the anterioposterior (y-) axis was significantly less at the DLS level than in the adjacent L2–L3 (P=0.01) and L3–L4 levels (P=0.04) (Figure 6C).

The average rangs of translation along the three axes varied from 1.6 to 2.5 mm at DLS level and 1.1 to 1.8 mm at adjacent levels. There was no significant difference between the studied levels. (Table 2)

Comparison with healthy participants and DDD patients

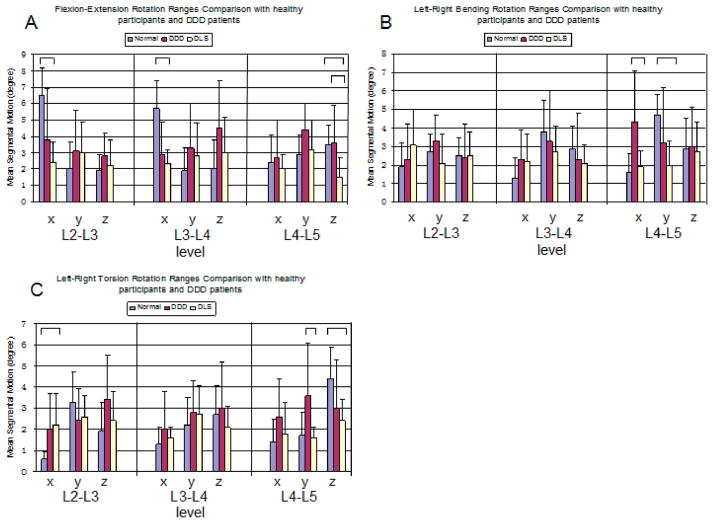

Flexion-extension of the trunk

The primary rotations around the mediolateral (x-) axis at the DLS level (L4–L5) were not significantly different compared to the healthy participants and the DDD patients (Figure 7A). However, the coupled rotations of the DLS patients were significantly smaller around the cranial-caudal (z-) axis, where the DLS patients had a range of rotation of 1.5°±1.2°, the healthy participants had 3.6°±2.3° (P=0.02), and the DDD patients had 3.5°±1.2° (P=0.004).

Fig. 7.

Range of facet joint rotation in patients among DLS, DDD and normal subjects around three principal axes under (A) torsion, (B) bending, and (C) flexion of the torso. The bar represent statistical significance upon between group comparison (P<0.05).

The DLS patients showed significantly lower range of primary rotation than the healthy subjects at the adjacent levels L3–L4 (DLS: 2.3°± 0.9° vs. healthy: 5.7°±1.7° P=0.0001) and L2–L3 (DLS: 2.4°± 1.3° vs. healthy: 6.5°±1.7° P=0.0001). No significant differences were observed between the DLS patients and the healthy subjects in coupled rotations.

Left-right bending of the trunk

The primary rotations around the anteroposterior axis (y-) at the DLS level (L4–L5) were decreased significantly compared to the healthy subjects (Figure 7B). The DLS patients had a range of rotation of 2.0°± 1.3° and the healthy participants had a range of rotation of 4.7°± 1.1°(P=0.001). The coupled rotation of the DLS patients around the mediolateral (x-) axis was significantly smaller compared to the DDD patients (DLS: 1.9°±0.9° vs. DDD: 4.3°±2.8° P=0.023).

At the adjacent levels L3–L4 and L2–L3, no significant difference was observed among the DLS, DDD and healthy subjects.

Left-right torsion of the trunk

The primary rotations at the DLS level (L4–L5) were not significantly different from the primary rotations of the DDD patients (Figure 7C), but were significantly lower than those of the healthy participants (DLS: 2.4°± 1.0° vs. healthy: 4.4°±1.5° P=0.01). The coupled rotations of the DLS patients around the anterioposterior (y-) axis were significantly smaller compared with those of the DDD patients (DLS: 1.6°±0.5° vs. DDD: 3.6°±2.5° P=0.02).

At the adjacent level L3–L4, no significant difference was observed among the DLS, DDD and healthy subjects. At the L2–L3 level, the rotation around the mediolateral (x-) axis was similar with the DDD patients but significantly larger than the healthy participants (DLS: 2.2°±1.5° vs. healthy: 0.6°±0.3° P=0.019).

Translations

The ranges of translation at L2–L3, L3–L4, and L4–L5 were compared among the DLS patients, the DDD patients and the healthy participants (Table 2). The range of translation was between 0.8 and 3.2 mm in the DDD patients, 0.8 and 4.1 mm in the normal participants, and 1.1 and 3.3 mm in the DLS patients. In general, there are no significant differences among the three participant groups. (Table 2).

Facet orientation

The transverse and longitudinal angles for both the superior and inferior facets were presented in (Table 3, 4). In the DLS patients, the transverse orientation of the L4 inferior articular facet angle relative to the coronal plane was more sagittal than the healthy participants (P<0.05). The longitudinal orientation of the facet joints was not significantly different between the DLS patients and the healthy subjects at the L4–L5 level (P>0.05).

Table 3.

Transverse Orientation of Lumbar Facets in degree Comparison with the normal participants

| vertebra | Left superior | Right superior | Left inferior | Right inferior | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DLS | Normal | DLS | Normal | DLS | Normal | DLS | Normal | |

| L2 | 22(10) | 22(13) | 21(10) | 21(11) | ||||

| L3 | 22(6) | 18(6) | 24(7) | 21(8) | 27(11) | 29(16) | 27(10) | 30(12) |

| L4 | 25(9) | 27(10) | 28(6) | 29(7) | 28(8)* | 40(16)* | 28(9)+ | 39(13)+ |

| L5 | 31(9) | 38(16) | 32(8) | 41(12) | ||||

The values for orientation are mean (standard deviation)

(*,+) L4 superior articular facet angle relative to the coronal plane was more sagittal than healthy participants (P<0.05)

Table 4.

Longitudinal Orientation of Lumbar Facets in degree Comparison with the normal participants

| vertebra | Left superior | Right superior | Left inferior | Right inferior | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DLS | Normal | DLS | Normal | DLS | Normal | DLS | Normal | |

| L2 | 165(7) | 170(6) | 165(7) | 170(5) | ||||

| L3 | 167(6) | 167(7) | 168(7) | 168(5) | 164(7) | 166(4) | 163(6) | 166(5) |

| L4 | 165(6) | 167(7) | 167(7) | 167(8) | 162(6) | 163(6) | 164(5) | 163(6) |

| L5 | 166(7) | 168(5) | 166(6) | 168(5) | ||||

The values for longitudinal orientation are mean (standard deviation)

DISCUSSION

In this study, we investigated the ROMs of lumbar facet joints in elderly patients with Grade 1 DLS at L4–L5 during functional weightbearing activities and compared the data to those of healthy subjects 20 and DDD patients 21 that have been reported previously. At the DLS level, no significant difference was found in the range of translation of the facet joint when compared to the range of translation in healthy subjects and DDD patients. However, in general, the range of rotation of the facet joint in the DLS group decreased compared to both DDD patients and healthy subjects. The data on adjacent levels was similar to that observed from DDD patients. These findings indicate that DLS is correlated to the alteration of movement in the facet joint and restabilizes the joints at the involved level.

Few studies have reported on the kinematics of the lumbar facet joints 15, 28. Svedmark et al. assessed the movement of the lumbar facet joint in healthy participants during flexion-extension using CT scanning and the volume registration techniques 28. Kozanek et al. described the motion of the facet joints in vivo and found that the motion was different between L4–L5 and the above two levels 20. Li et al. indicated that rotation increased significantly not only at DDD levels but also at the adjacent levels 21. No data was reported on the 6DOF kinematics of the facet joints in patients with DLS during in vivo physiologic weight-bearing avtivities.

Kirkaldy-Willis and Farfan proposed a pathway describing DLS development 29, where the advancing segmental degeneration of human spine follows a course from stable to dysfunctional and unstable to restabilized conditions. However, it is difficult to examine this pathway by following a patient group through the entire process of lumbar vertebral degeneration. In this study, we selected a normal subject group and a DDD patient group from our previous studies as comparison groups. The subjects in these two groups had average ages of 54.4 and 51.8 years, respectively. The reported data indicated that segmental motion increased in patients with moderate facet joint and disc degeneration as compared to the normal subjects 21. The data in this present study further indicated that when disc degeneration progressed to grade 5 and the facet joint to grade 3, segmental motion decreased in DLS patients compared to healthy subjects. The decrease in segmental motion implies that a restablization of the facet joint occurs when DDD progresses to DLS. These results are consistent with previous assumptions on the structural and biomechanical changes in the facet joint that occur with degeneration of the vertebral segments18, 30. However, we have to note that the average age of DLS patients was higher than the ages of the normal subjects and the DDD patients. Age may also be another factor that leads to the reduced motion in the facet joint.

The kinematic difference noted in this study may be correlated to the structural change of the lumbar facet. Grobler and Fujiwara et al. indicated that the DLS group had a greater sagittal orientation at the L4 to L5 facet joint than the asymptomatic group 31, 32. In this present study, a significantly greater sagittal facet orientation was also found when compared to the healthy subjects in L4–L5 level. These results imply that the facet joint motion can be increased in the sagittal plane of the DLS patients. However, the range of rotation of the facet joint in the DLS group decreased compared to the healthy subjects. It is difficult to draw a conclusion whether increasing sagittal orientation is a causative factor or the consequence of DLS. Interestingly, our kinematic data indicated that the range of translation of the facet joint is not significantly increased compared to the normal groups in the sagittal plane. This may indicate that the facet joint geometry is adapted from the DLS disease progress.

The findings of our study may have valuable clinical implications. Decompression only or decompression with spinal fusion, which has been conventionally used in surgical treatments for DLS patients 33. However, there is an ongoing discussion as to whether additional fusion is superior to decompression surgery alone. Several follow-up outcome studies have shown that decompression plus fusion improved patient outcomes compared to decompression alone34, 35. However, there are also reports indicating that a decompression could result in similar clinical outcomes as the decompression and instrumented fusion36. Segmental instability is an important factor in determining the surgical method. An unstable DLS is usually treated with fusion surgery, which has always been referenced as the gold standard for instability 37. Current kinematic studies, however, indicate that for elderly patients with Grade 1 DLS, there is no significant instability in the motions of facet joints during active in vivo function of the body. This information may help the selection of conservative treatment or different surgical techniques for the DLS patients. Recently, several interspinous devices have been introduced as an alternative to fusion surgeries for elderly patients with Grade 1 DLS 5, 38. However, the efficiency of these devices in treating DLS has yet to be shown in long term follow up studies.

There are several limitations in this study that need to be noted. The study only focused on an elderly DLS patient population and the sample size was relatively small. However, we specifically selected patients with DLS at the L4–L5 level, who are within the age range of most patients that are commonly treated for degenerative spondylolisthesis. In addition, we only examined the range of motion of the L2–L3, L3–L4, and L4–L5 segments during the three weightbearing functional activities because the size of the field view of the fluoroscopes was limited. Despite these limitations, the present study provides new data on aberrant facet joint motion characteristics in DLS patients with various physiologic loading conditions.

In conclusion, the present study used an in vivo technique to quantify abnormal motion of the lumbar facet joint in DLS patients during various weight-bearing positions. The data could provide baseline information to help identify and characterize the pathologic motion of the facet joint under in-vivo physiological conditions. This information may help develop specified conservative or surgical techniques and evaluate the effect of new surgical modalities for treatment of DLS patients.

Acknowledgments

This study was partially supported by the NIH (R21AR057989), National Natural Science Foundation of China (81000796) and Beijing Nova Program (2011085) and China Scholarship Council (2011911025)

Footnotes

Approval of the study by our institutional review board was obtained prior to the initiation of this study. Informed consent was obtained from each patient before any testing was performed.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Rosenberg NJ. Degenerative spondylolisthesis. Predisposing factors. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1975;57:467–474. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kalichman L, Kim DH, Li L, et al. Spondylolysis and spondylolisthesis: prevalence and association with low back pain in the adult community-based population. Spine. 2009;34:199–205. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e31818edcfd. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jacobsen S, Sonne-Holm S, Rovsing H, et al. Degenerative lumbar spondylolisthesis: an epidemiological perspective: the Copenhagen Osteoarthritis Study. Spine. 2007;32:120–125. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000250979.12398.96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Weinstein JN, Lurie JD, Tosteson TD, et al. Surgical versus nonsurgical treatment for lumbar degenerative spondylolisthesis. New Engl J Med. 2007;356:2257–2270. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa070302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hong SW, Lee HY, Kim KH, et al. Interspinous ligamentoplasty in the treatment of degenerative spondylolisthesis: midterm clinical results. J Neurosurg Spine. 2010;13:27–35. doi: 10.3171/2010.3.SPINE0957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kalichman L, Hunter DJ. Lumbar facet joint osteoarthritis: a review. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2007;37:69–80. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2007.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jayakumar P, Nnadi C, Saifuddin A, et al. Dynamic degenerative lumbar spondylolisthesis: diagnosis with axial loaded magnetic resonance imaging. Spine. 2006;31:E298–301. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000216602.98524.07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boden SD, Riew KD, Yamaguchi K, et al. Orientation of the lumbar facet joints: association with degenerative disc disease. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1996;78:403–11. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199603000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Berlemann U, Jeszenszky DJ, Buhler DW, et al. The role of lumbar lordosis, vertebral end-plate inclination, disc height, and facet orientation in degenerative spondylolisthesis. J Spinal Disord Tech. 1999;12:68–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Iguchi T, Wakami T, Kurihara A, et al. Lumbar multilevel degenerative spondylolisthesis: radiological evaluation and factors related to anterolisthesis and retrolisthesis. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2002;15:93–99. doi: 10.1097/00024720-200204000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kalichman L, Suri P, Guermazi A, et al. Facet orientation and tropism: associations with facet joint osteoarthritis and degeneratives. Spine. 2009;34:E579–585. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181aa2acb. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alicioglu B, Sut N. Synovial cysts of the lumbar facet joints: a retrospective magnetic resonance imaging study investigating their relation with degenerative spondylolisthesis. Prague medical report. 2009;110:301–309. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chaput C, Padon D, Rush J, et al. The significance of increased fluid signal on magnetic resonance imaging in lumbar facets in relationship to degenerative spondylolisthesis. Spine. 2007;32:1883–1887. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e318113271a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lattig F, Fekete TF, Grob D, et al. Lumbar facet joint effusion in MRI: a sign of instability in degenerative spondylolisthesis? Eur spine J. 2012;21:276–281. doi: 10.1007/s00586-011-1993-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jegapragasan M, Cook DJ, Gladowski DA, Kanter AS, Cheng BC. Characterization of articulation of the lumbar facets in the human cadaveric spine using a facet-based coordinate system. Spine J. 2011;11:340–346. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2011.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wood KB, Schendel MJ, Pashman RS, et al. In vivo analysis of canine intervertebral and facet motion. Spine. 1992;17:1180–1186. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199210000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Adams MA, Hutton WC. The mechanical function of the lumbar apophyseal joints. Spine. 1983;8:327–330. doi: 10.1097/00007632-198304000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kong MH, Morishita Y, He W, et al. Lumbar segmental mobility according to the grade of the disc, the facet joint, the muscle, and the ligament pathology by using kinetic magnetic resonance imaging. Spine. 2009;34:2537–2544. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181b353ea. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li G, Wang S, Passias P, et al. Segmental in vivo vertebral motion during functional human lumbar spine activities. Eur spine J. 2009;18:1013–1021. doi: 10.1007/s00586-009-0936-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kozanek M, Wang S, Passias PG, et al. Range of motion and orientation of the lumbar facet joints in vivo. Spine. 2009;34:E689–696. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181ab4456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li W, Wang S, Xia Q, et al. Lumbar facet joint motion in patients with degenerative disc disease at affected and adjacent levels: an in vivo biomechanical study. Spine. 2011;36:E629–637. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181faaef7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ganju A. Isthmic spondylolisthesis. Neurosurgical focus. 2002;13:E1. doi: 10.3171/foc.2002.13.1.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pfirrmann CW, Metzdorf A, Zanetti M, et al. Magnetic resonance classification of lumbar intervertebral disc degeneration. Spine. 2001;26:1873–1878. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200109010-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Weishaupt D, Schweitzer ME, Alam F, et al. MR imaging of inflammatory joint diseases of the foot and ankle. Skeletal Radiol. 1999;28:663–669. doi: 10.1007/s002560050571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang S, Passias P, Li G, et al. Measurement of vertebral kinematics using noninvasive image matching method-validation and application. Spine. 2008;33:E355–361. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181715295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Masharawi Y, Rothschild B, Dar G, et al. Facet orientation in the thoracolumbar spine: three-dimensional anatomic and biomechanical analysis. Spine. 2004;29:1755–1763. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000134575.04084.ef. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Panjabi MM, Goel V, Oxland T, et al. Human lumbar vertebrae. Quantitative three-dimensional anatomy. Spine. 1992;17:299–306. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199203000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Svedmark P, Tullberg T, Noz ME, et al. Three-dimensional movements of the lumbar spine facet joints and segmental movements: in vivo examinations of normal subjects with a new non-invasive method. Eur spine J. 2011;21:599–605. doi: 10.1007/s00586-011-1988-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kirkaldy-Willis WH, Farfan HF. Instability of the lumbar spine. Clin Orthop. 1982:110–123. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fujiwara A, Lim TH, An HS, et al. The effect of disc degeneration and facet joint osteoarthritis on the segmental flexibility of the lumbar spine. Spine. 2000;25:3036–3044. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200012010-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Grobler LJ, Robertson PA, Novotny JE, et al. Etiology of spondylolisthesis. Assessment of the role played by lumbar facet joint morphology. Spine. 1993;18:80–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fujiwara A, Tamai K, An HS, et al. Orientation and osteoarthritis of the lumbar facet joint. Clin Orthop. 2001:88–94. doi: 10.1097/00003086-200104000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sengupta DK, Herkowitz HN. Degenerative spondylolisthesis: review of current trends and controversies. Spine. 2005;30:S71–81. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000155579.88537.8e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nork SE, Hu SS, Workman KL, Glazer PA, Bradford DS. Patient outcomes after decompression and instrumented posterior spinal fusion for degenerative spondylolisthesis. Spine. 1999;24:561–569. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199903150-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Herkowitz HN, Kurz LT. Degenerative lumbar spondylolisthesis with spinal stenosis. A prospective study comparing decompression with decompression and intertransverse process arthrodesis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1991;73:802–808. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rampersaud YR, Wai E, Abraham E, et al. Health Related Quality of Life Following Decompression Compared to Decompression and Fusion for Degenerative Spondylolisthesis: A Canadian Multicenter Study. Spine J. 2010;10:S35–36. doi: 10.1503/cjs.032213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pearson A, Blood E, Lurie J, et al. Degenerative spondylolisthesis versus spinal stenosis: does a slip matter? Comparison of baseline characteristics and outcomes (SPORT) Spine. 2010;35:298. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181bdafd1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lee SH, Lee JH, Hong SW, et al. Spinopelvic alignment after interspinous soft stabilization with a tension band system in grade 1 degenerative lumbar spondylolisthesis. Spine. 2010;35:E691. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181d2607e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]