Background: Ubiquitination plays critical roles in many cellular processes.

Results: The Entamoeba histolytica ubiquitin activating, conjugating, and ligating enzymes interact and transfer ubiquitin.

Conclusion: E. histolytica possesses a functional ubiquitination cascade with key differences from mammalian homologs.

Significance: The E. histolytica ubiquitin-proteasome pathway may provide therapeutic targets for amoebic colitis and amoebiasis.

Keywords: Enzyme Structure, Parasite, Protein Degradation, Protein Structure, Ubiquitin, Ubiquitin-conjugating Enzyme (Ubc), Ubiquitin Ligase

Abstract

Ubiquitination is important for numerous cellular processes in most eukaryotic organisms, including cellular proliferation, development, and protein turnover by the proteasome. The intestinal parasite Entamoeba histolytica harbors an extensive ubiquitin-proteasome system. Proteasome inhibitors are known to impair parasite proliferation and encystation, suggesting the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway as a viable therapeutic target. However, no functional studies of the E. histolytica ubiquitination enzymes have yet emerged. Here, we have cloned and characterized multiple E. histolytica ubiquitination components, spanning ubiquitin and its activating (E1), conjugating (E2), and ligating (E3) enzymes. Crystal structures of EhUbiquitin reveal a clustering of unique residues on the α1 helix surface, including an eighth surface lysine not found in other organisms, which may allow for a unique polyubiquitin linkage in E. histolytica. EhUbiquitin is activated by and forms a thioester bond with EhUba1 (E1) in vitro, in an ATP- and magnesium-dependent fashion. EhUba1 exhibits a greater maximal initial velocity of pyrophosphate:ATP exchange than its human homolog, suggesting different kinetics of ubiquitin activation in E. histolytica. EhUba1 engages the E2 enzyme EhUbc5 through its ubiquitin-fold domain to transfer the EhUbiquitin thioester. However, EhUbc5 has a >10-fold preference for EhUba1∼Ub compared with unconjugated EhUba1. A crystal structure of EhUbc5 allowed prediction of a noncovalent “backside” interaction with EhUbiquitin and E3 enzymes. EhUbc5 selectively engages EhRING1 (E3) to the exclusion of two HECT family E3 ligases, and mutagenesis indicates a conserved mode of E2/RING-E3 interaction in E. histolytica.

Introduction

Post-translational modification by ubiquitin and ubiquitin-like modifiers (ULMs)3 plays critical roles in the cellular biology of many eukaryotes (1). Isopeptide bond-mediated attachment of monoubiquitin or polyubiquitin chains to specific target proteins regulates processes as diverse as cell cycle progression, development, and the immune response (2). Polyubiquitination also serves as a primary signal for protein turnover, targeting proteins for degradation by the 26 S proteasome (3). ULM attachments are catalyzed by conserved enzyme cascades, with ATP-dependent ULM activation catalyzed by E1, conjugation by E2, and targeting of specific protein substrates by E3 ligases (3). Ubiquitin-activating enzymes (E1s) in eukaryotes serve to adenylate ubiquitin, consuming ATP and releasing pyrophosphate (PPi). Subsequently, a thioester bond is formed between an E1 active site cysteine and the dual-glycine C terminus of the activated ubiquitin, releasing AMP, and a second ubiquitin molecule is also adenylated (4). The resulting E1∼Ub thioester complex engages a ULM-conjugating enzyme (E2), with major contributions to the E1/E2 interface arising from the E1 ubiquitin-fold domain (UFD) (5). The thioester bond between the ubiquitin C terminus and the E1 enzyme is transferred to a conserved cysteine residue on the E2, resulting in a covalent E2∼Ub adduct (6). E3 ubiquitin-ligating enzymes can be classified into two major groups, containing either homology to the E6AP C terminus (HECT) or really interesting new gene related (RING) domains (3). HECT family E3 enzymes possess a catalytic cysteine that accepts the ubiquitin thioester from bound E2∼Ub prior to ubiquitin isopeptide bond formation with a lysine acceptor (7). In the case of RING E3 enzymes, ubiquitin is directly transferred to the target protein from E2∼Ub; the RING E3 enzyme serves primarily as an adaptor pairing ubiquitin-charged E2 enzymes with specific E3-bound substrates (3). However, RING interactions with E2∼Ub also prime the E2 for efficient ubiquitin conjugation to acceptor lysines (8). Ubiquitin monomers can be added directly to surface lysines on substrate proteins, or can instead be linked into polyubiquitin chains, utilizing any of the seven lysines on the surface of ubiquitin, although some polyubiquitin linkages are more frequently utilized than others (9).

The single-celled intestinal parasite Entamoeba histolytica is the causative agent of amoebic colitis and systemic amoebiasis, with the latter characterized by cysts in liver, lungs, and brain (10). Spread in an encysted form, E. histolytica infection is endemic in developing countries with poor barriers between sewage and drinking water (11). Although E. histolytica has been the subject of research for more than 50 years, the relatively recent sequencing of its genome (12) affords the opportunity for further insight into cellular machinery that may be amenable to pharmacologic manipulation, such as the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway. The cloning and characterization of an E. histolytica ubiquitin gene (termed Ehubiquitin) highlighted a surprising degree of sequence divergence from homologs in humans and lower organisms, given the remarkably high degree of conservation among other species (13). Despite its relatively dissimilar sequence, EhUbiquitin complements deletion of the polyubiquitin gene ubi4 in yeast, suggesting conserved functions in E. histolytica (14). More recent bioinformatic analyses of the E. histolytica genome revealed an extensive family of putative ubiquitin activating, conjugating, and ligating enzymes, as well as parallel systems for other ubiquitin-like modifiers (15). However, functional studies of this putative ubiquitination machinery have not yet emerged. Interestingly, treatment with proteasome inhibitors impairs growth of E. histolytica trophozoites and encystation in the related species Entamoeba invadens, suggesting that the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway may be a valuable therapeutic target (16). Altered expression of ubiquitin-proteasomal genes has also been correlated with perturbations in virulence (e.g. Ref. 17). Our own study of heterotrimeric G-protein signaling in E. histolytica demonstrated that markers of trophozoite virulence are enhanced or reduced upon overexpression of the Gα subunit, EhGα1, or a dominant-negative EhGα1 mutant, respectively (18). A transcriptome analysis by RNA-seq revealed differential expression of multiple ubiquitin-proteasome pathway-related genes upon expression of wild-type or mutant EhGα1, including the Ehubiquitin gene itself (Table 1). In the present study, we sought to characterize, both structurally and biochemically, various components of the E. histolytica ubiquitination machinery, spanning ubiquitin and its interacting E1–E3 enzymes. We hypothesize that differences revealed between the E. histolytica components and well studied mammalian homologs may elucidate a potential means for specific targeting of ubiquitination within the parasitic amoeba.

TABLE 1.

Ubiquitin and proteasome system genes differentially transcribed in E. histolytica trophozoites expressing EhGα1 or the dominant-negative EhGα1S37C

| Gene name | AmoebaDB accession no. | Fold-change upon EhGα1 expression | Fold-change upon EhGα1S37C expression |

|---|---|---|---|

| p value | |||

| Ubiquitin system/proteasome | |||

| Hypothetical (RING finger domain) | EHI_104520 | 1.9 (0.004) | |

| Ubiquitin-activating enzyme | EHI_004850 | 1.7 (0.013) | |

| Zinc finger protein (RING-type) | EHI_165120 | 1.8 (0.004) | |

| Ulp1 protease family, C-terminal catalytic | EHI_138530 | 2.2 (0.002) | |

| F-box domain containing protein | EHI_103710 | −1.9 (0.007) | |

| 26 S Protease regulatory subunit | EHI_185410 | −1.8 (0.011) | |

| RING zinc finger protein | EHI_023310 | −2.1 (0.008) | |

| Hypothetical (UBX domain) | EHI_027910 | −2.5 (< 0.001) | |

| Proteasome subunit α type 3 | EHI_098060 | −2.0 (0.007) | |

| Zinc finger protein (RING-type) | EHI_130650 | −1.9 (0.004) | |

| RING zinc finger protein | EHI_161980 | −2.1 (< 0.001) | |

| Zinc finger, RING-type | EHI_159840 | −2.3 (< 0.001) | |

| Proteasome subunit α type 2-A | EHI_052140 | 1.7 (0.019) | |

| WWE domain | EHI_069610 | 1.7 (< 0.001) | |

| Ubiquitin | EHI_083410 | 2.2 (< 0.001) | |

| Zinc finger, RING-type | EHI_110790 | 2.3 (< 0.001) | |

| Ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme E2 | EHI_131530 | 2.0 (< 0.001) | |

| Ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme E2 | EHI_135460 | 1.8 (0.009) | |

| 26 S Protease regulatory subunit | EHI_177320 | 1.9 (< 0.001) | |

| 19 S Cap proteasome S2 subunit | EHI_198010 | 3.6 (< 0.001) | |

| 26 S Protease regulatory subunit | EHI_053020 | 2.2 (0.020) | |

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Cloning and Protein Purification

Genomic DNA was isolated from the virulent HM-1:IMSS strain of E. histolytica using a DNeasy Blood and Tissue Kit (Qiagen). Open reading frames of Ehubiquitin (AmoebaDB accession EHI_083410), Ehuba1 (EHI_020270), Ehubc5 (EHI_083560), Ehring1 (EHI_020100), Ehhect1 (EHI_011530), and Ehhect2 (EHI_124600) were PCR amplified from genomic DNA and subcloned as hexahistidine fusions into a pET vector-based ligation-independent cloning vector, pLIC-His, as described previously (19). PCR primer sequences were: Ehubiquitin, 5′-ATGCAAATATTTGTTAAGAC-3′ and 5′-TTAATATCCTCCTCTTAATC-3′; Ehuba1, 5′-ATGACACAACAAATTGATGAAGCCGTATTG-3′ and 5′-TTAGAAATTCAAAAGAACATCTGGAAATTC-3′; Ehubc5, 5′-ATGGCTATGCGTAGAATTCAAAAAG-3′ and 5′-TTATGGTCGAGCATACATAC-3′; Ehring1, 5′-ATGTCAAGAGAAGATTGTG-3′ and 5′-TTAGTGATAAATAATTCGGTG-3′; Ehhect1, 5′-ATGCGGAAACACCTCAAATAACAAATAA-3′ and 5′-TTAAATTAAACCAAATCCATTTGTATT-3′; Ehhect2, 5′-ATGAGACCGGCTTGGAGACTTA-3′ and 5′-TTAAGAAAATGCAAATCCTGATTTTGATG-3′. Fragments subcloned and purified as recombinant proteins included the ubiquitin-fold domain of EhUba1 (amino acids 882–984), EhRING1 (amino acids 1–246), EhHECT1 HECT domain (amino acids 277–660), and EhHECT2 HECT domain (amino acids 370–750). Point mutations to EhUbc5 were made using PCR and the overlap extension method (20).

Recombinant human Uba1, derived from insect cells, was purchased from Boston Biochem. Ubiquitin from bovine erythrocytes was purchased from Sigma. Because the sequences of bovine and human ubiquitin are identical, the protein is referred to as human ubiquitin throughout the study, for clarity. For each of the E. histolytica components, BL21 Escherichia coli were grown to an A600 nm of 0.8 at 37 °C and expression was induced with 500 μm isopropyl β-d-thiogalactopyranoside for 14–16 h at 20 °C. Pelleted bacterial cells were resuspended in N1 buffer containing 30 mm HEPES, pH 8.0, 250 mm NaCl, and 30 mm imidazole and lysed by high-pressure homogenization with an Emulsiflex (Avestin; Ottawa, Canada). Cellular lysates were cleared by centrifugation at 100,000 × g for 1 h at 4 °C, and the supernatant was applied to a nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid (NTA) FPLC column (GE Healthcare), washed extensively with N1, and eluted in N1 buffer with 300 mm imidzaole. For proteins used in biochemical experiments, eluted protein was pooled and resolved using a size exclusion column (HiLoad 16/60 Superdex 200, GE Healthcare) in S200 buffer containing 50 mm HEPES, pH 7.5, and 100 mm NaCl (5 mm ZnCl2 was included in the case of EhRING1 purification). For proteins used in crystallographic studies, protein eluted from the NTA column was pooled and dialyzed into imidazole-free N1 supplemented with 5 mm DTT overnight at 4 °C in the presence of His6-tobacco etch virus protease to cleave the N-terminal affinity tag. The dialysate was then passed over a second NTA column to remove tobacco etch virus protease and uncleaved protein, followed by resolution by size exclusion in S200 buffer. All proteins except EhUba1 were concentrated to 0.25–2 mm and snap frozen in a dry ice/ethanol bath for storage at −80 °C. EhUba1 was found to precipitate upon freeze/thaw, but could be stably maintained at 4 °C for at least 2 weeks. Protein concentration was determined by A280 nm measurements upon denaturation in 8 m guanidine hydrochloride, based on predicted extinction coefficients for each protein using Expasy.

Crystallization and Structure Determinations of EhUbiquitin and EhUbc5

Crystals of EhUbiquitin were obtained by vapor diffusion from hanging drops at 18 °C in two different crystal forms. EhUbiquitin crystal form 1 was obtained by mixing EhUbiquitin at 17 mg/ml (1:1) with crystallization solution containing 25% (w/v) PEG 3350 and 100 mm citric acid, pH 3.5. A single crystal grew to ∼500 × 400 × 400 μm over 5 days, exhibiting the symmetry of space group P3221 (a = b = 49.8 Å, c = 63.8 Å, α = β = 90°, γ = 120°) and containing one monomer in the asymmetric unit. For the second crystal form, EhUbiquitin at 13 mg/ml in S200 buffer was mixed 1:1 with (and equilibrated against) crystallization solution containing 22% (w/v) PEG 3350, 200 mm LiSO4, and 100 mm BisTris, pH 5.5. Crystals grew to ∼200 × 100 × 100 μm over 3 days, exhibiting the symmetry of space group P212121 (a = 38.6 Å, b = 49.9 Å, c = 76.8 Å, α = β = γ = 90°) and containing two monomers in the asymmetric unit. For data collection at 100 K, crystals were serially transferred for ∼1 min into crystallization solution supplemented with 30% (v/v) glycerol in 10% increments and plunged into liquid nitrogen. Native data sets were collected at the GM/CA-CAT 23-ID-B beamline at the Advanced Photon Source (Argonne National Laboratory). Data were processed using HKL2000 (21). The crystal structure model of human ubiquitin (PDB code 1UBQ) was used as a molecular replacement search model using PHENIX AutoMR (22). Refinement was carried out using phenix.refine (22), interspersed with manual revisions of the model using the program Coot (23). Refinement consisted of conjugate-gradient minimization and calculation of individual anisotropic displacement and translation/libration/screw parameters (24). The current model of crystal form 1 contains one EhUbiquitin monomer; residues 7–10 and 73–77 could not be located in the electron density. Ramachandran plot analysis indicated 100% favored residues. The current model of crystal form 2 contains two EhUbiquitin monomers; residues 75–77 of chain A and 74–77 of chain B could not be accurately modeled in the electron density. Ramachandran plot analysis indicated 98.6% favored, 1.4% allowed, and 0% disallowed residues.

Crystals of EhUbc5 were obtained by vapor diffusion from hanging drops at 18 °C. EhUbc5 at 8 mg/ml in S200 buffer was mixed 1:1 with (and equilibrated against) crystallization solution containing 100 mm Tris, pH 7.5, 14% (w/v) polyvinylpyrrolidone K15, and 500 μm CoCl2. Hexagonal crystals grew to ∼400 × 300 × 200 μm over 5 days and exhibited the symmetry of space group P212121 (a = 47.0 Å, b = 49.6 Å, c = 63.5 Å, α = β = γ = 90°) with one monomer in the asymmetric unit. For data collection at 100 K, crystals were transferred for ∼1 min into crystallization solution supplemented with 25% glycerol and plunged into liquid nitrogen. A native data set was collected at the SER-CAT 22BM beamline at the Advanced Photon Source (Argonne National Laboratory). Data processing and refinement were carried out similarly to EhUbiquitin, as mentioned above. A molecular replacement solution was obtained using the crystal structure model of human UbcH5b (PDB code 2ESK), modified to exclude water. The current model contains one EhUbc5 monomer with a cobalt ion coordinated by surface residues and by a monomer from the neighboring asymmetric unit. All EhUbc5 residues could be located in the electron density. Ramachandran plot analysis indicated 97.3% favored, 2.7% allowed, and 0% disallowed residues.

In Vitro Ubiquitin Transfer Assay

Ubiquitin transfer experiments were conducted essentially as previously described for NEDD8ylation (25), with adaptations to allow visualization of EhUba1∼EhUb thioester formation. Briefly, 1 μm EhUba1, 5 μm wild-type or mutant EhUbc5, and 15 μm EhUbiquitin were incubated 15 min at room temperature in ubiquitin transfer buffer containing 50 mm HEPES, pH 7.5, 100 mm NaCl, 10 mm MgCl2, and 5 mm ATP. The reactions were halted by denaturation in 5× nonreducing SDS sample buffer, and 50 mm DTT was added to specified reactions for 10 min prior to protein separation by denaturing SDS-PAGE and staining with Coomassie Blue.

In Vitro Polyubiquitin Chain Formation Assay

Polyubiquitin chain formation experiments were conducted essentially as previously described (26). 50 nm EhUba1, 1 μm EhUbc5, 8 μm N-terminal FLAG epitope-tagged EhUbiquitin, and 10 μm EhRING1 were incubated at 37 °C for 45 min in reaction buffer containing 50 mm HEPES, pH 7.5, 100 mm NaCl, 10 mm MgCl2, and 5 mm ATP. Reactions were halted by denaturation in 5× reducing SDS sample buffer, and 50 mm DTT was added to all reactions 10 min prior to protein separation by SDS-PAGE. Proteins were transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane and probed with anti-FLAG (M2 monoclonal; Sigma).

PPi:ATP Radioisotope Exchange Assay

Isotope exchange assays were conducted as previously described (4). All assays were performed at 37 °C and contained 6 nm E1 ubiquitin-activating enzyme, 1 μm ubiquitin protein, 100 μm AMP, 10 mm MgCl2, 100 μm nonradioactive pyrophosphate (PPi), and variable ATP concentrations. Reactions were initiated by addition of the E1 enzyme. Concentrations of EhUba1 and human Uba1 were determined by the Bradford method. Incubation times were <15 min and within the linear portion of the progress curve (prior to approaching equilibrium). Incorporation of 32PPi into ATP was determined by adsorbing the ATP to activated charcoal. Reactions were quenched with 5% (w/v) trichloroacetic acid (TCA) containing 4 mm nonradioactive PPi, mixed with a 10% (w/v) slurry of charcoal in 2% TCA, pelleted by centrifugation, and washed three times with 2% TCA. Charcoal-bound radioactivity was quantified by Cherenkov radiation. Background radiation from control reactions lacking E1 was subtracted, and no significant exchange was observed in the absence of E1, ubiquitin, or ATP. All assays were performed in duplicate, and error bars represent S.E. from three independent experiments. Data were fit by linear regression using GraphPad Prism version 5.0. Approximate Km and Vmax values were derived from a Lineweaver-Burk plot, where the y intercept = 1/Vmax and the x intercept = −1/Km.

Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) Assays

SPR-based measurements of protein-protein interactions were performed on a Biacore 3000 (GE Healthcare), essentially as described previously (19). Briefly, purified His6-EhUbc5 and His6-EhUbc5(F62A) proteins were separately immobilized on an NTA biosensor chip using covalent capture coupling (27). EhUbiquitin, EhUba1, or E3 ligase proteins were injected in 30-μl volumes at increasing concentrations. For binding experiments with EhUba1-EhUb, 20 μm EhUba1 and 50 μm EhUbiquitin were incubated 20 min at 30 °C in buffer containing 50 mm HEPES, pH 7.5, 100 mm NaCl, 1 mm ATP, and 10 mm MgCl2 to allow for ubiquitin activation and thioester formation. EhUba1-EhUb was injected in 30 μl volumes using the KINJECT command with a 300-s dissociation time. Each EhUba1-EhUb injection was followed by a 10-μl injection of 50 mm DTT to detach thioester-coupled EhUbiquitin from the EhUbc5 surface. Experiments were performed in running buffer containing 50 mm HEPES, pH 7.4, 150 mm NaCl, 0.05% Nonidet P-40 alternative (Calbiochem), 50 μm EDTA, and 1 mm MgCl2. Background changes in refractive index upon injection of samples was subtracted from all curves using BIAevaluation software version 3.0 (GE Healthcare). Equilibrium binding analyses were conducted as previously described (28) using GraphPad Prism version 5.0 to determine binding affinities.

RESULTS

Structural Features of a Divergent Ubiquitin from E. histolytica

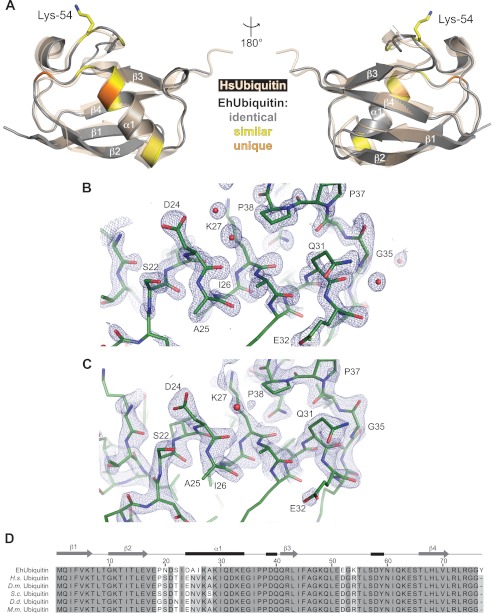

To give spatial context to the variant residues within E. histolytica ubiquitin (13) and their effects, if any, on the overall structure, we crystallized EhUbiquitin and determined its structure in two crystal forms. Under the first set of conditions, a single crystal was obtained that yielded diffraction data extending to 1.35-Å resolution. Although the diffraction data were of otherwise high quality (Table 2), detector overload resulted in exclusion of a significant fraction of low-resolution data during processing. Incomplete low-resolution data were manifested as unusually high R-factors and average B-factors during refinement (Table 2); however, the electron density was of good quality (Fig. 1B), with clear electron density obtained for the divergent residues of EhUbiquitin upon phasing by molecular replacement with human ubiquitin (PDB code 1UBQ). We also obtained EhUbiquitin crystals under a second condition, and a structure was determined using diffraction data to 2.15 Å (Table 2 and Fig. 1C). The data collection and refinement statistics corresponding to the second EhUbiquitin crystal form were near the mean of other deposited structures of similar resolution (22). Although the structures derived from both diffraction data sets were essentially identical, the second crystal form was utilized for further analyses due to the unusually high R-factors of crystal form 1.

TABLE 2.

Data collection and refinement statistics for EhUbiquitin and EhUbc5

| EhUbiquitin (#1) | EhUbiquitin (#2) | EhUbc5 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| PDB accession code | 4GU2 | 4GSW | 4GPR |

| Data collection | |||

| Space group | P3221 | P212121 | P212121 |

| Cell dimensions | |||

| a, b, c (Å) | 49.80, 49.80, 63.83 | 38.61, 49.87, 76.82 | 46.97, 49.58, 63.46 |

| α, β, γ (°) | 90.0, 90.0, 120.0 | 90.0, 90.0, 90.0 | 90.0, 90.0, 90.0 |

| Wavelength (Å) | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| Resolution (Å) | 25.7–1.35 (1.36–1.35)a | 40.0–2.15 (2.17–2.15)a | 50.0–1.60 (1.62–1.60)a |

| No. unique reflections | 20493 (486) | 8430 (210) | 19998 (426) |

| Rmerge (%) | 4.3 (55.7)b | 8.5 (27.9)b | 4.4 (30.9)b |

| I/σI | 100 (6.9) | 32.8 (3.1) | 45.6 (2.8) |

| Completeness (%) | 99.0 (100.0) | 97.5 (96.8) | 99.2 (87.3) |

| Redundancy | 19.2 (17.9) | 3.5 (3.3) | 8.2 (3.7) |

| Wilson B-factor (Å2) | 18.9 | 31.9 | 17.1 |

| Refinement | |||

| Resolution (Å) | 25.6–1.35 (1.42–1.35) | 34.5–2.15 (2.28–2.15) | 39.0–1.60 (1.64–1.60) |

| No. reflections | 20454 (2718) | 8379 (1154) | 19950 (1148) |

| Rwork/Rfree (%) | 22.0/27.4 (22.8/31.3) | 20.9/27.1 (26.6/35.0) | 17.6/20.5 (20.6/26.0) |

| No. atoms | |||

| Protein | 1157 | 1171 | 1195 |

| Ligand/ion | 1 | ||

| Water | 66 | 44 | 179 |

| Average B-factors (Å2) | |||

| Protein | 55.2 | 41.5 | 15.0 |

| Ligand/ion | 8.1 | ||

| Water | 58.5 | 41.9 | 27.2 |

| Root mean square deviations | |||

| Bond lengths (Å) | 0.015 | 0.014 | 0.014 |

| Bond angles (°) | 1.642 | 1.493 | 1.504 |

a Values in parentheses are for highest-resolution shell.

b All data were collected from a single crystal.

FIGURE 1.

Sequence variations in EhUbiquitin cluster on a single surface. A, the crystal structure of EhUbiquitin (gray) is superimposed with human ubiquitin (wheat; PDB code 1UBQ), highlighting the similarities of their backbone structures. Sequence and structural alignments were used to identify conservative (yellow) and nonsimilar (orange) amino acid differences between the E. histolytica and human homologs. The nonidentical residues of the EhUbiquitin cluster onto a single surface dominated by the first α-helix. EhUbiquitin possesses an additional surface lysine (Lys-54) that may allow for unique polyubiquitin linkage in E. histolytica. B, diffraction data for EhUbiquitin crystal form 1 extended to 1.35-Å resolution. Despite low-resolution incompleteness, the 2Fo − Fc electron density map contoured to σ = 3.0 was of good quality. Red spheres represent ordered water molecules. C, diffraction data from the EhUbiquitin crystal form 2 were of high quality, given a lower resolution limit of 2.15 Å. The 2Fo − Fc electron density map is contoured to σ = 3.0. D, the protein sequence of EhUbiquitin was aligned to ubiquitin molecules from other species. EhUbiquitin shows the highest degree of sequence divergence, with 7 nonidentical residues compared with human ubiquitin. The predicted sequence of EhUbiquitin also includes a C-terminal tyrosine that may be cleaved in E. histolytica trophozoites to expose a conserved C-terminal Gly-Gly motif. D.m. indicates Drosophila melanogaster; S.c. is S. cerevisiae, H.s. is Homo sapiens; D.d. is Dictyostelium discoideum; and M.m. is Mus musculus.

The Cα trace of EhUbiquitin is highly similar to human ubiquitin (root mean square deviation 0.78 Å; Fig. 1A). This finding is consistent with the protein core residues being identical between the two homologs (13), with the exception of position 26, which exhibits a subtle variation of isoleucine in E. histolytica compared with the conserved valine in a broad diversity of other species (Fig. 1D). Mapping the variant EhUbiquitin residues compared with its human homolog revealed clustering of divergent residues on a single surface, dominated by the α1 helix and including proximal portions of the β2-α1 and β3-β4 loops (Fig. 1A). Notably, one of the residues unique to E. histolytica (Fig. 1D) is an extra surface lysine (Lys-54). Because each surface lysine on mammalian ubiquitin can be utilized for polyubiquitin chain formation (9), it may be that E. histolytica possesses a unique Lys-54 linkage polyubiquitination pattern.

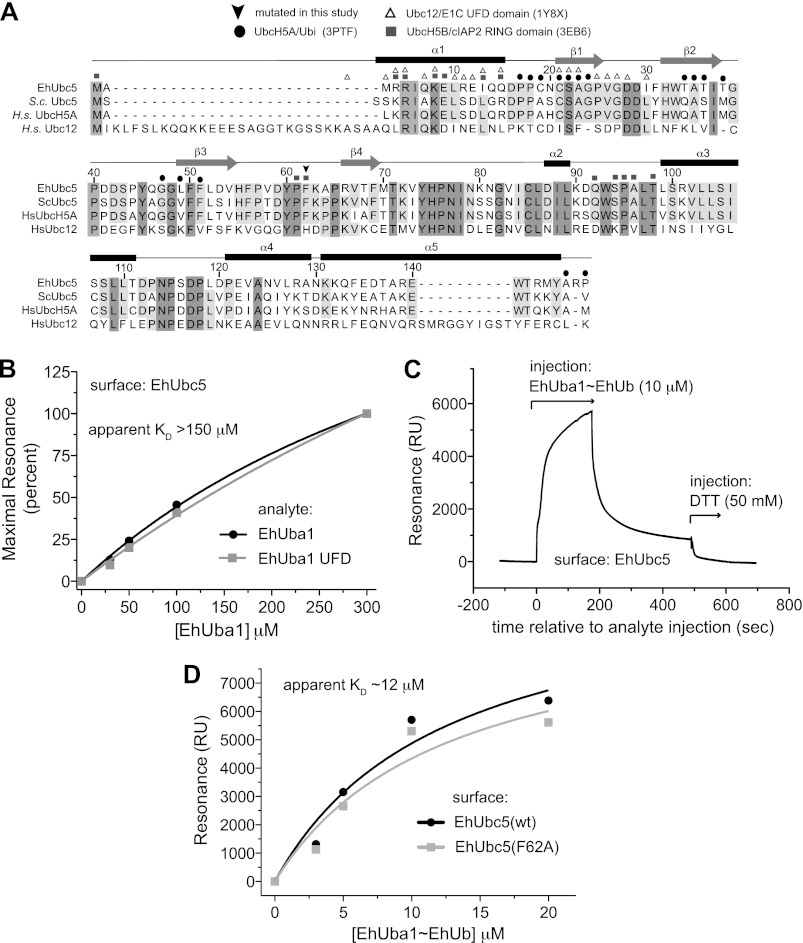

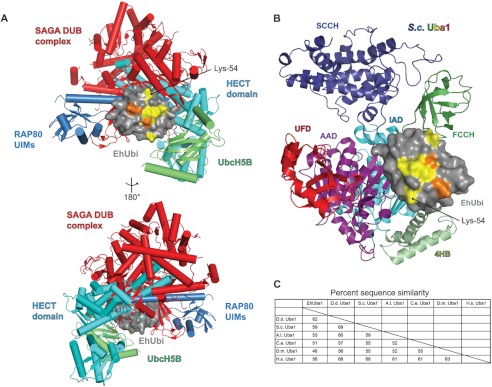

To identify potential interactions that may involve the divergent EhUbiquitin surface, we superimposed the EhUbiquitin structure on a number of ubiquitin complex structures available in the RCSB database. Most of the surface of ubiquitin is utilized by one or more ubiquitin-binding proteins; however, the well characterized interactions with E2 conjugating enzymes (e.g. UbcH5), HECT family E3 ligases, deubiquitinating enzymes (e.g. the SAGA complex), and ubiquitin-interacting motifs (e.g. RAP80) are not predicted to form significant interactions with the unique ubiquitin residues of E. histolytica (Fig. 2A). Thus, at this time, we do not predict that the sequence variation seen in EhUbiquitin will significantly affect its interactions with similar ubiquitin-binding proteins encoded by the E. histolytica genome. The distinct EhUbiquitin surface may be utilized for other interactions unique to E. histolytica. However, no specific function of the divergent EhUbiquitin surface can be ascribed at this time.

FIGURE 2.

The divergent EhUbiquitin surface is not frequently utilized by structurally elucidated ubiquitin-binding proteins. A, the nonidentical residues of EhUbiquitin cluster onto a single surface dominated by the first α-helix. This ubiquitin surface is not utilized by many of the best-studied and structurally characterized ubiquitin binding partners. EhUbiquitin (gray) was superimposed on structural models of ULM homologs in complex with ULM-interacting proteins. Ubiquitin thioester formation with conjugating E2 enzymes and a HECT family E3 ligase are represented by UbcH5B (PDB code 3A33) (6) and the Nedd4 HECT domain (PDB code 2XBB) (40), respectively. Ubiquitin interaction with de-ubiquitinating (DUB) enzymes is illustrated by the SAGA DUB complex (PDB code 3MHS) (41). A ubiquitin interacting motif (UIM) protein is also exemplified by RAP80 (PDB code 3A1Q) (42). B, the domain structure of yeast Uba1 is drawn and colored as in Ref. 30. The interaction of EhUbiquitin with E1 enzymes was modeled by superposition of EhUbiquitin with yeast Uba1∼Ub (PDB code 3CMM). The divergent residues of EhUbiquitin (colored yellow and orange as in Fig. 1) are not predicted to alter interaction with E1 enzymes. IAD indicates the inactive adenylation domain, FCCH is the first catalytic cysteine half-domain, 4HB is the four-helix bundle domain, AAD is the active adenylation domain, SCCH is the second catalytic cysteine half-domain, and UFD is the ubiquitin-fold domain. C, E1 enzyme sequence similarity and identity were compared across species. EhUba1 is most similar to that of the slime mold D. discoideum.

EhUbiquitin Is Activated by the E1 Enzyme EhUba1

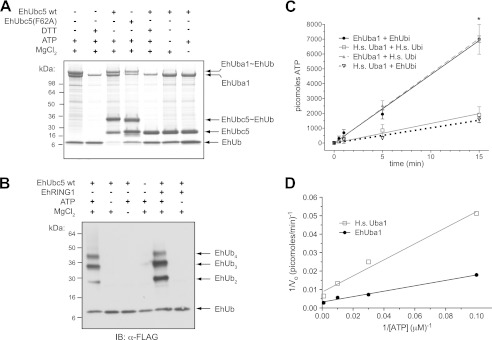

The E. histolytica genome encodes a single predicted ubiquitin-activating E1 enzyme, as well as predicted activating enzymes for Nedd8, SUMO, and other ubiquitin-like modifiers (15). The putative ubiquitin-activating enzyme EhUba1 (AmoebaDB accession EHI_020270) was cloned from genomic DNA, expressed, and purified from E. coli. EhUba1 possesses a predicted domain structure similar to Saccharomyces cerevisiae Uba1 and other eukaryotic E1s (not shown). The sequence of EhUba1 was most similar to that of the slime mold D. discoideum, followed by S. cerevisiae, when compared with a broad spectrum of E1 enzyme sequences from different species (Fig. 2C). To determine whether EhUba1 was capable of activating EhUbiquitin, we examined in vitro ubiquitin transfer with purified components. EhUba1 was seen to form a typical thioester bond with EhUbiquitin that was sensitive to reduction by DTT (Fig. 3A). Magnesium and ATP were required for ubiquitin activation and thioester bond formation, suggesting a conserved mechanism of ubiquitin activation in E. histolytica. A number of mammalian E2 enzymes, together with an E1, are capable of catalyzing formation of isopeptide-linked polyubiquitin chains (29). In vitro polyubiquitination experiments revealed that EhUbc5, together with EhUba1 could efficiently promote formation of EhUbiquitin chains up to four molecules in length (Fig. 3B). Polyubiquitin chain formation required E2 enzyme, as well as the EhUba1 cofactors of magnesium and ATP.

FIGURE 3.

The ubiquitin-activating enzyme EhUba1 catalyzes EhUbiquitin thioester formation and transfer to the E2 enzyme EhUbc5. A, recombinant EhUba1 derived from E. coli forms a thioester bond with EhUbiquitin in an ATP- and magnesium-dependent fashion, as illustrated by SDS-PAGE and Coomassie Blue staining under nonreducing conditions. Activated EhUbiquitin is seen to be transferred to the ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme EhUbc5. Each of the covalent interactions detected was sensitive to 50 mm DTT reducing agent. The loss-of-E3-binding mutant EhUbc5(F62A) did not significantly affect ubiquitin thioester formation. B, EhUba1 and EhUbc5 were sufficient to catalyze polyubiquitin chain formation in the presence of ATP and magnesium, as detected by SDS-PAGE and Western blotting (IB) under reducing conditions. EhUba1 and EhUbc5 were seen to efficiently promote formation of chains up to four ubiquitin molecules under these conditions, and addition of EhRING1 had modest effects. C, PPi:ATP radioisotope exchange was utilized to compare in vitro ubiquitin activation by EhUba1 and human Uba1 in the presence of 6 nm E1 enzyme, 1 μm ubiquitin, 1 mm ATP, 100 μm AMP, and 100 μm nonradioactive PPi. Under these conditions EhUba1 exhibited a statistically significant ∼3.5-fold increase in isotope exchange rate compared with its human homolog (460 ± 33 (95% C.I.) versus 132 ± 46 (95% C.I.) pmol/min). The observed difference in ubiquitin activation kinetics is apparently intrinsic to the E1 enzyme, because the isotope exchange rate was independent of the ubiquitin species utilized. These data represent average values of triplicate experiments with mean ± S.E. * indicates a statistically significant difference between EhUba1 and human Uba1 determined by Student's t test. D, the dependence of human Uba1- and EhUba1-mediated isotope exchange on ATP was assessed under identical conditions as panel C, excepting ATP concentration. A Lineweaver-Burk plot allowed estimation of Km and Vmax values describing E1 activity with respect to ATP. Under these conditions, the apparent Km and Vmax values were 45 μm and 459 pmol/min (95% C.I. 392–552 pmol/min) for the E. histolytica components and 50 μm and 115 pmol/min (95% C.I. 93–152 pmol/min) for the human components, with respect to ATP. Each initial velocity measurement was conducted in duplicate, and the displayed results are representative of two independent experiments.

We next sought to compare the activities of ubiquitin activating enzymes from E. histolytica and humans. To quantify the kinetics of enzyme-dependent incorporation of pyrophosphate (PPi) into ATP, an in vitro radioactive 32PPi:ATP isotope exchange assay was employed as described previously (4). In the presence of 1 μm ubiquitin protein, 100 μm AMP, 10 mm MgCl2, and 100 μm nonradioactive PPi, the initial rate of PPi:ATP exchange catalyzed by human Uba1 was 132 pmol/min (linear regression 95% confidence interval (C.I.) 88–176 pmol/min) (Fig. 3C), in good agreement with previous measurements under similar conditions (4). EhUba1, in contrast, exhibited a significantly faster initial isotope exchange velocity of 460 pmol/min (95% C.I. 428–493 pmol/min), under identical conditions. The ∼3.5-fold greater velocity of exchange for EhUba1 compared with human Uba1 is intrinsic to the E1 enzyme, given that the respective exchange rates in the presence of either human or E. histolytica ubiquitin substrates were indistinguishable (Fig. 3C). A superimposition of EhUbiquitin with the structural model of S. cerevisiae Uba1∼Ub suggests that the divergent ubiquitin surface in E. histolytica is not utilized in the E1/ubiquitin interface (Fig. 2B), consistent with similar kinetics of the E1 enzymes in activating either the human or E. histolytica ubiquitin substrate. Residues that contact ATP in other E1 enzymes (e.g. Ref. 30), such as the GXGXXGCE motif, are well conserved in EhUba1 (not shown). A Lineweaver-Burk plot was constructed based upon PPi:ATP exchange experiments with varying ATP concentrations, allowing estimation of Km and Vmax with respect to the ATP substrate for both human and E. histolytica E1 enzymes (Fig. 3D). EhUba1 exhibited higher velocities of isotope exchange with Vmax = 459 pmol/min (95% C.I. 392–552 pmol/min), compared with its human homolog with Vmax = 115 pmol/min (95% C.I. 93–152 pmol/min) under these conditions. However, the Km values with respect to ATP were highly similar, being 45 and 50 μm, respectively (Fig. 3D).

EhUba1 Engages the E2 Enzyme EhUbc5 and Transfers Activated EhUbiquitin

A number of predicted E2 ubiquitin-conjugating enzymes have been identified within the E. histolytica genome, although none has been functionally assessed (15). We cloned a subset of candidate E2s from the E. histolytica genome and attempted to express and purify each of them from E. coli. One E2 protein (Amoeba DB accession EHI_083560; Fig. 4A) with similarity to yeast Ubc4 and Ubc5 (termed EhUbc5) was highly expressed and thus selected for further study. Surface plasmon resonance was performed with immobilized EhUbc5, indicating a low affinity interaction with non-ubiquitin-associated EhUba1 (Fig. 4B). A KD value for the EhUba1/EhUbc5 interaction could not be precisely quantified by equilibrium binding analyses due to the protein concentration limitations of our assay, but was greater than 150 μm. The isolated ubiquitin-fold domain (UFD) of EhUba1 (amino acids 882–984) exhibited a similar apparent affinity for EhUbc5, indicating its sufficiency for binding the E2 (Fig. 4B). In similar SPR experiments, EhUba1 was first allowed to activate EhUbiquitin and form an EhUba1∼Ub thioester complex (under conditions similar to Fig. 3A) prior to injection over an EhUbc5 surface. Following dissociation of EhUba1∼Ub, persistent residual resonance was observed (Fig. 4C), suggesting that some activated ubiquitin may be transferred covalently to the EhUbc5-laden surface. Indeed, the residual resonance due to the apparent thioester-coupled EhUbiquitin could be rapidly eliminated by injection of the reducing agent DTT (Fig. 4C). An equilibrium binding analysis suggested at least a 10-fold greater affinity of EhUbc5 for EhUba1∼Ub than for unconjugated EhUba1 (Fig. 4D). Notably, the apparent affinity of EhUbc5 for EhUba1∼EhUb (KD ≈ 12 μm) is likely underestimated by this approach, given that saturation could not be reached with each analyte injection (Fig. 4C) and the reported EhUba1∼EhUb concentrations (Fig. 4D) assume that 100% of the EhUba1 enzyme injected was conjugated to ubiquitin. However, correction of either potential source of error would further lower the apparent EhUba1∼Ub/EhUbc5 dissociation constant value, resulting in a >10-fold preference of EhUbc5 for EhUbiquitin-conjugated over unconjugated EhUba1. Transfer of the EhUbiquitin thioester from EhUba1 to EhUbc5 was also demonstrated by an in vitro assay (Fig. 3A). Ubiquitin activation by EhUba1 and subsequent transfer to the E2 enzyme was found to be dependent on the presence of ATP and magnesium. The EhUbc5-EhUb thioester bond was also sensitive to the reducing agent DTT.

FIGURE 4.

EhUba1 interacts directly with EhUbc5 through its ubiquitin-fold domain, and affinity is enhanced by the presence of activated EhUbiquitin. A, the protein sequence of EhUbc5 was aligned to its closest homologs in yeast and humans, as well as human Ubc12. The secondary structure elements reflect the crystal structure of EhUbc5. Residues involved in interaction with E2 binding partners were derived from previously published structures (PDB IDs in parentheses). The majority of predicted interaction residues are conserved in EhUbc5. B, surface plasmon resonance was utilized to measure direct binding of either unconjugated EhUba1 or its isolated UFD to immobilized EhUbc5. EhUba1 binds EhUbc5 with low affinity in the absence of activated EhUbiquitin, and the UFD of EhUba1 is sufficient for binding. C, EhUba1 was allowed to form covalent linkage with activated EhUbiquitin prior to injection over immobilized EhUbc5. Residual resonance following injection of EhUba1-EhUb was sensitive to the reducing agent DTT, likely indicating thioester transfer of EhUbiquitin to the immobilized EhUbc5. D, the apparent affinity of EhUba1∼EhUb for EhUbc5 was significantly higher than that of unconjugated EhUba1 (panel B). The apparent KD value of ∼12 μm is likely overestimated because less than 100% of the injected EhUba1 is expect to be conjugated to EhUbiquitin (Fig. 3) and equilibrium of binding could not be reached under these experimental conditions (panel C). The loss of E3-binding mutant EhUbc5(F62A) did not significantly affect affinity for EhUba1∼EhUb.

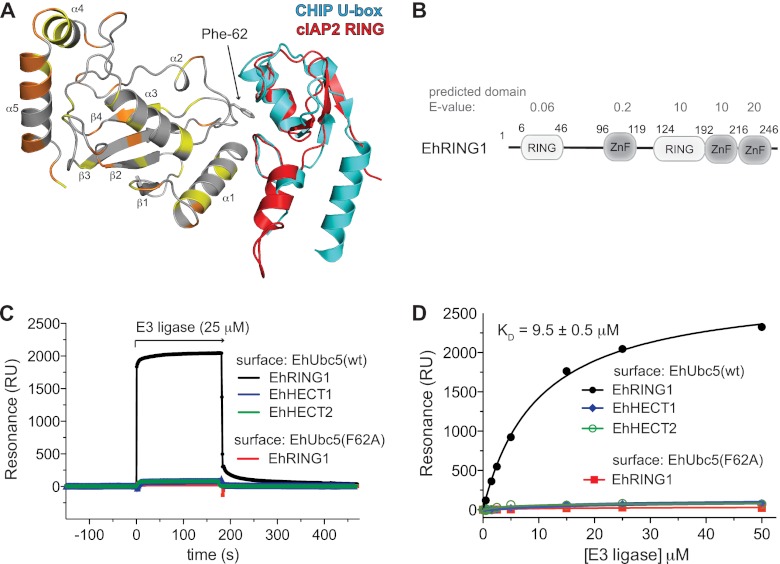

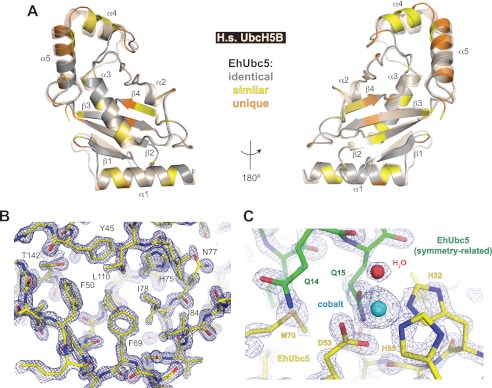

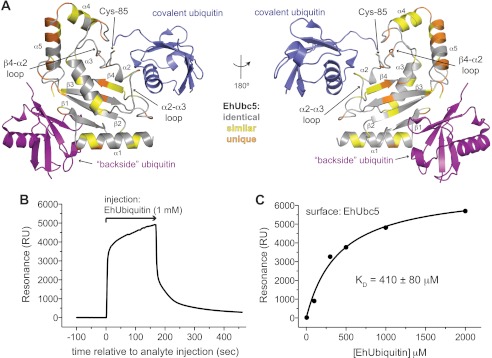

Structural Features of the E2 Ubiquitin-conjugating Enzyme EhUbc5 and Its Noncovalent Interaction with EhUbiquitin

To gain further insight into ubiquitin conjugation in E. histolytica, EhUbc5 was crystallized and its structure determined by molecular replacement with diffraction data extending to 1.6-Å resolution (Table 2). Although EhUbc5 crystallized under a variety of conditions, the crystal form described here required a cobalt (II) salt. A cobalt ion could be identified in the electron density, contacting EhUbc5 molecules in adjacent asymmetric units (Fig. 5C). The cobalt ion appears to be octahedrally coordinated with two histidine and one aspartate ligand from one EhUbc5 monomer, complemented by a glutamine from a symmetry-related EhUbc5 and by a water molecule. The overall structural model of EhUbc5 is remarkably similar to human UbcH5B (Cα root mean square deviation of 0.69 Å), given only 73% sequence identity and 83% similarity (Figs. 4A and 5A). As seen in the case of EhUbiquitin, the majority of the EhUbc5 hydrophobic core is identical to human UbcH5B, whereas divergent residues predominantly reside on the protein surface (Fig. 5, A and B). The β4-α2 and α2-α3 loops are highly conserved among E2 enzymes, including EhUbc5 (Fig. 4A), suggesting a likely conserved mode of interaction with covalently attached ubiquitin (Fig. 6A). In particular, EhUbc5 Cys-85 likely forms a thioester bond with the C terminus of activated EhUbiquitin (Fig. 3A). E2 enzymes are also known to bind ubiquitin-like modifiers in a noncovalent, “backside” interaction thought to be important for assembly of polyubiquitin chains (31, 32). To assess a potential noncovalent interaction between EhUbc5 and EhUbiquitin, we predicted E2 enzyme residues likely to be involved based on the known interaction between human UbcH5A and human ubiquitin (Fig. 4A) (33). The analogous residues in EhUbc5 were 62% identical and 87% similar, suggesting a potentially conserved noncovalent interaction with EhUbiquitin. In support of this hypothesis, EhUbiquitin was found to bind EhUbc5, as measured by SPR (Fig. 6, B and C). The apparent low affinity of the EhUbc5/EhUbiquitin interaction (KD = 410 ± 80 μm) is consistent with other monoubiquitin interactions, specifically homologous noncovalent interactions with other E2 enzymes (KD values ∼100–500 μm) (2, 31).

FIGURE 5.

The crystal structure of EhUbc5 is highly similar to human UbcH5B despite sequence divergence. A, the crystal structure of EhUbc5 (gray) is superimposed on its closest human homolog, UbcH5B (wheat, PDB code 2ESK) (43). Sequence and structural alignment was used to identify conservative (yellow) and nonsimilar (orange) amino acid differences between the E. histolytica and human homologs. B, a representative 2Fo − Fc electron density map of the EhUbc5 hydrophobic core, contoured to σ = 2.5, was rendered using PyMol. C, cobalt (cyan sphere) was required for crystallization and found incorporated in the crystal lattice at an interface between symmetry-related EhUbc5 molecules. Cobalt ion (cyan sphere) is coordinated by two histidines and an aspartic acid from one EhUbc5 molecule (yellow), a glutamine from the adjacent EhUbc5 molecule (green), and a water molecule. Each of the six apparent coordinating groups is 2.1–2.2 Å from the cobalt ion. The 2Fo − Fc electron density map is contoured to σ = 3.5.

FIGURE 6.

EhUbc5 engages EhUbiquitin through covalent thioester and noncovalent backside interactions. A, the predicted interactions of EhUbc5 with thioester-conjugated ubiquitin (blue) and noncovalent backside bound ubiquitin (purple) was modeled by superimposition of EhUbc5 with human UbcH5B∼Ub (PDB code 3A33) (6) and noncovalent UbcH5A/Ub (PDB code 3PTF) (33). The two predicted ubiquitin interfaces of EhUbc5 are relatively well conserved, suggesting similar modes of interaction in E. histolytica. B and C, EhUbc5 interacts noncovalently with EhUbiquitin, as determined by SPR. The low affinity of interaction is consistent with the analogous interaction between human E2 domains and human ubiquitin (2).

EhUbc5 Engages a RING Family E3 Ubiquitin Ligase

We next sought to identify E3 ligases in E. histolytica that may partner with EhUbc5 to ubiquitinate specific substrate proteins. The E. histolytica genome encodes a large number of putative E3 enzymes including HECT, RING, PHD, and U-box domain-containing proteins (15). A subset of candidate E3s were cloned from E. histolytica genomic DNA and expressed in E. coli. Of this subset, one RING family E3 and two HECT domains could be purified to near homogeneity in quantities suitable for biochemical experiments. The RING family protein (AmoebaDB accession EHI_020100), here termed EhRING1, contains predicted RING and zinc finger motifs according to SMART (34), although significant sequence divergence results in relatively high domain prediction E-values (Fig. 7B). We were unable to identify a clear homolog for EhRING1 in either humans or yeast. The first 246 amino acids of EhRING1 were seen to bind EhUbc5 with a dissociation constant of 9.5 ± 0.5 μm, as determined by SPR (Fig. 7, B and C). In contrast, the HECT domains of two putative E3 ligases, termed EhHECT1 (EHI_011530) and EhHECT2 (EHI_124600), did not bind immobilized EhUbc5 (Fig. 7, B and C). A superimposition of EhUbc5 on crystal structure models of E2 enzymes in complex with a cIAP2 RING domain (35) and the CHIP U-box domain (36) suggests a well conserved EhUbc5 surface at the predicted RING family E3 binding site (Fig. 7A). To test whether EhUbc5 engages EhRING1 in a similar fashion, we mutated the conserved phenylalanine 62 to alanine, a residue predicted to contribute to RING binding. Indeed, EhUbc5(F62A) displayed a drastically reduced affinity for EhRING1 (Fig. 7). However, EhUbc5(F62A) maintained its ability to form a thioester bond with activated EhUbiquitin (Fig. 3A) and to bind EhUba1-EhUb (Fig. 4D), indicating proper folding of the point-mutated EhUbc5 protein. EhRING1 had only modest effects, if any, on EhUbc5-catalyzed polyubiquitin chain formation, as assessed qualitatively by in vitro assays (Fig. 3B).

FIGURE 7.

EhUbc5 exhibits a conserved mode of interaction with a RING family E3 ligase. A, the predicted interaction between EhUbc5 and RING family E3 ligases was modeled by superposition of EhUbc5 on the structural coordinates of the human UbcH5-CHIP U-box complex (PDB code 2OXQ) (36) and the UbcH5-cIAP2 RING domain complex (PDB code 3EB6) (35). Phenylalanine 62 is highly conserved across species and contributes to the E2/RING E3 interface. B, EhRING1 possesses an N-terminal predicted RING domain and zinc finger (ZnF) domain, as well as additional, weakly predicted RING and zinc finger domains. Domain prediction E-values were derived using SMART (34). All biochemical experiments described in this study were conducted with EhRING1 residues 1–246. C and D, EhUbc5 bound a putative RING family E3 ubiquitin ligase from E. histolytica with low micromolar affinity, but not two HECT family E3 ligases, as measured by SPR. Mutation of Phe-62 drastically reduced the affinity of EhUbc5 for EhRING1, indicating a likely conserved mode of E2/E3 interaction in E. histolytica.

DISCUSSION

Our experiments demonstrate the presence of a functional ubiquitin activation and conjugation pathway in E. histolytica. The substantial differences in the EhUbiquitin protein sequence compared with other species cluster on a single surface, constructed primarily of the α1 helix. Our analyses suggest that this particular surface is not central to the structurally elucidated ubiquitin interfaces with E1s, E2s, HECT, and RING E3s, ubiquitin interacting motifs, and deubiquitinating enzymes in other species. However, the high degree of conservation at this surface in a diverse set of other organisms suggests a likely role(s) in ubiquitin functions. EhUbiquitin may have evolved to lack these functions, allowing sequence drift on the α1 helix and surrounding surface. Alternatively, EhUbiquitin may have evolved an as yet undetermined alternative use for this surface. The function of the α1 helix region has not yet been established in E. histolytica; accordingly, its potential value as a therapeutic target is unclear. Of particular interest is the presence of an eighth surface lysine (Lys-54) unique to EhUbiquitin (arginine in all other organisms examined) and included in the divergent surface. Complex polyubiquitination patterns utilizing all seven surface lysines and the N terminus of ubiquitin exist in other species, corresponding to an array of interaction modes and affinities for various ubiquitin binding domains (37). Thus, it is likely that additional unique polyubiquitination patterns and interactions arise in E. histolytica, involving the additional exposed lysine. Further studies are necessary to determine the prevalence of Lys-54 polyubiquitination in E. histolytica and its potential functions.

EhUba1 appears to activate ubiquitin in a similar fashion to its homologs in other species. However, the observed significant difference in maximal velocity of PPi:ATP exchange compared with human Uba1 suggests differences in ubiquitin activation kinetics. Additional work is needed to determine whether ubiquitin activation by this enzyme is necessary for parasitic virulence, and whether specific inhibition of EhUba1 is a viable therapeutic goal. Inhibitors of mammalian E1s have been used with some success, demonstrating the feasibility of this approach (38).

EhUbc5 exhibited a striking selectivity for EhUba1∼Ub compared with unconjugated EhUba1. Because the EhUba1 UFD bound EhUbc5 with an affinity similar to that of unconjugated EhUba1, it appears that some portion of the EhUba1∼Ub complex, in addition to the UFD, contributes to E2 binding following ubiquitin activation. An altered EhUba1 conformation, or perhaps the EhUbiquitin molecule itself, may provide a higher affinity surface for EhUbc5. This functionality may help EhUbc5 recognize ubiquitin-bound E1 for efficient transfer and/or allow for rapid release of the E1-E2 complex once ubiquitin transfer has occurred. The noncovalent interaction of EhUbiquitin with EhUbc5 suggests a likely conserved mechanism for conjugating polyubiquitin chains (31). EhUbc5 was also seen to engage a RING family E3 (EhRING1) through a conserved mode of interaction, to the exclusion of two HECT family E3s. This finding suggests a possible RING E3 specificity for EhUbc5; however, we cannot rule out the possibility that EhUbc5 interacts with other, untested HECT E3 ligases, like its yeast homologs (39). It is unclear at this time which target proteins are ubiquitinated downstream of EhUbc5 and EhRING1.

The E. histolytica ubiquitin-proteasome pathway may provide therapeutic targets for potential treatment of amoebic colitis and amoebiasis. Of particular feasibility may be a proteasome inhibitor with selectivity for the E. histolytica protein target, given the previously demonstrated effects of proteasome inhibition on trophozoite proliferation and encystation (16). Alternatively, EhUba1-specific E1 inhibition may be expected to grossly perturb trophozoite function and viability, given the necessity of ubiquitin activation for multiple vital cellular processes in other eukaryotes (38).

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Michael Miley and Mischa Machius at the University of North Carolina Center for Structural Biology for crystallographic assistance and Biacore 3000 access. Crystallographic experiments were conducted at the 22-BM and 23-ID-B beamlines at the Advanced Photon Source (Argonne National Labs). We thank Drs. Joe Harrison and Brian Kuhlman (University of North Carolina), as well as Drs. Jill Hurst and Henrik Dohlman (University of North Carolina), for helpful discussions.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grant R01 GM082892 (to D. P. S.).

- ULM

- ubiquitin-like modifier

- UFD

- ubiquitin-fold domain

- HECT

- homology to the E6AP C terminus

- NTA

- nitrilotriacetic acid

- BisTris

- 2-[bis(2-hydroxyethyl)amino]-2-(hydroxymethyl)propane-1,3-diol

- SPR

- surface plasmon resonance

- PDB

- Protein Data Bank

- C.I.

- confidence interval.

REFERENCES

- 1. Burroughs A. M., Iyer L. M., Aravind L. (2012) Structure and evolution of ubiquitin and ubiquitin-related domains. Methods Mol. Biol. 832, 15–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hicke L., Schubert H. L., Hill C. P. (2005) Ubiquitin-binding domains. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 6, 610–621 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Deshaies R. J., Joazeiro C. A. (2009) RING domain E3 ubiquitin ligases. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 78, 399–434 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Haas A. L., Rose I. A. (1982) The mechanism of ubiquitin activating enzyme. A kinetic and equilibrium analysis. J. Biol. Chem. 257, 10329–10337 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Huang D. T., Paydar A., Zhuang M., Waddell M. B., Holton J. M., Schulman B. A. (2005) Structural basis for recruitment of Ubc12 by an E2 binding domain in NEDD8's E1. Mol. Cell 17, 341–350 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Sakata E., Satoh T., Yamamoto S., Yamaguchi Y., Yagi-Utsumi M., Kurimoto E., Tanaka K., Wakatsuki S., Kato K. (2010) Crystal structure of UbcH5b-ubiquitin intermediate. Insight into the formation of the self-assembled E2∼Ub conjugates. Structure 18, 138–147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Huang L., Kinnucan E., Wang G., Beaudenon S., Howley P. M., Huibregtse J. M., Pavletich N. P. (1999) Structure of an E6AP-UbcH7 complex. Insights into ubiquitination by the E2-E3 enzyme cascade. Science 286, 1321–1326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Plechanovova A., Jaffray E. G., Tatham M. H., Naismith J. H., Hay R. T. (2012) Structure of a RING E3 ligase and ubiquitin-loaded E2 primed for catalysis. Nature 489, 115–120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Emmerich C. H., Schmukle A. C., Walczak H. (2011) The emerging role of linear ubiquitination in cell signaling. Sci. Signal. 4, re5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Haque R., Huston C. D., Hughes M., Houpt E., Petri W. A., Jr. (2003) Amebiasis. N. Engl. J. Med. 348, 1565–1573 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Stanley S. L., Jr. (2003) Amoebiasis. Lancet 361, 1025–1034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Loftus B., Anderson I., Davies R., Alsmark U. C., Samuelson J., Amedeo P., Roncaglia P., Berriman M., Hirt R. P., Mann B. J., Nozaki T., Suh B., Pop M., Duchene M., Ackers J., Tannich E., Leippe M., Hofer M., Bruchhaus I., Willhoeft U., Bhattacharya A., Chillingworth T., Churcher C., Hance Z., Harris B., Harris D., Jagels K., Moule S., Mungall K., Ormond D., Squares R., Whitehead S., Quail M. A., Rabbinowitsch E., Norbertczak H., Price C., Wang Z., Guillén N., Gilchrist C., Stroup S. E., Bhattacharya S., Lohia A., Foster P. G., Sicheritz-Ponten T., Weber C., Singh U., Mukherjee C., El-Sayed N. M., Petri W. A., Jr., Clark C. G., Embley T. M., Barrell B., Fraser C. M., Hall N. (2005) The genome of the protist parasite Entamoeba histolytica. Nature 433, 865–868 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Wöstmann C., Tannich E., Bakker-Grunwald T. (1992) Ubiquitin of Entamoeba histolytica deviates in six amino acid residues from the consensus of all other known ubiquitins. FEBS Lett. 308, 54–58 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Wöstmann C., Liakopoulos D., Ciechanover A., Bakker-Grunwald T. (1996) Characterization of ubiquitin genes and -transcripts and demonstration of a ubiquitin-conjugating system in Entamoeba histolytica. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 82, 81–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Arya S., Sharma G., Gupta P., Tiwari S. (2012) In silico analysis of ubiquitin/ubiquitin-like modifiers and their conjugating enzymes in Entamoeba species. Parasitol. Res. 111, 37–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Makioka A., Kumagai M., Ohtomo H., Kobayashi S., Takeuchi T. (2002) Effect of proteasome inhibitors on the growth, encystation, and excystation of Entamoeba histolytica and Entamoeba invadens. Parasitol. Res. 88, 454–459 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Gilchrist C. A., Houpt E., Trapaidze N., Fei Z., Crasta O., Asgharpour A., Evans C., Martino-Catt S., Baba D. J., Stroup S., Hamano S., Ehrenkaufer G., Okada M., Singh U., Nozaki T., Mann B. J., Petri W. A., Jr. (2006) Impact of intestinal colonization and invasion on the Entamoeba histolytica transcriptome. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 147, 163–176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Bosch D. E., Kimple A. J., Muller R. E., Giguere P. M., Machius M. M., Willard F. S., Temple B. R., Siderovski D. P. (2012) Heterotrimeric G-protein signaling is critical to pathogenic processes in Entamoeba histolytica. PLoS Pathogens 8, e1003040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bosch D. E., Wittchen E. S., Qiu C., Burridge K., Siderovski D. P. (2011) Unique structural and nucleotide exchange features of the Rho1 GTPase of Entamoeba histolytica. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 39236–39246 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ho S. N., Hunt H. D., Horton R. M., Pullen J. K., Pease L. R. (1989) Site-directed mutagenesis by overlap extension using the polymerase chain reaction. Gene 77, 51–59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Otwinowski Z., Minor W. (1997) Processing of x-ray diffraction data collected in oscillation mode. Methods Enzymol. 276, 307–326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Adams P. D., Afonine P. V., Bunkóczi G., Chen V. B., Davis I. W., Echols N., Headd J. J., Hung L. W., Kapral G. J., Grosse-Kunstleve R. W., McCoy A. J., Moriarty N. W., Oeffner R., Read R. J., Richardson D. C., Richardson J. S., Terwilliger T. C., Zwart P. H. (2010) PHENIX. A comprehensive Python-based system for macromolecular structure solution. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 66, 213–221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Emsley P., Lohkamp B., Scott W. G., Cowtan K. (2010) Features and development of Coot. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 66, 486–501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Painter J., Merritt E. A. (2006) Optimal description of a protein structure in terms of multiple groups undergoing TLS motion. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 62, 439–450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Calabrese M. F., Scott D. C., Duda D. M., Grace C. R., Kurinov I., Kriwacki R. W., Schulman B. A. (2011) A RING E3-substrate complex poised for ubiquitin-like protein transfer. Structural insights into cullin-RING ligases. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 18, 947–949 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Yin Q., Lin S. C., Lamothe B., Lu M., Lo Y. C., Hura G., Zheng L., Rich R. L., Campos A. D., Myszka D. G., Lenardo M. J., Darnay B. G., Wu H. (2009) E2 interaction and dimerization in the crystal structure of TRAF6. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 16, 658–666 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kimple A. J., Muller R. E., Siderovski D. P., Willard F. S. (2010) A capture coupling method for the covalent immobilization of hexahistidine-tagged proteins for surface plasmon resonance. Methods Mol. Biol. 627, 91–100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kimple R. J., Willard F. S., Hains M. D., Jones M. B., Nweke G. K., Siderovski D. P. (2004) Guanine nucleotide dissociation inhibitor activity of the triple GoLoco motif protein G18. Alanine-to-aspartate mutation restores function to an inactive second GoLoco motif. Biochem. J. 378, 801–808 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Hochstrasser M. (2006) Lingering mysteries of ubiquitin-chain assembly. Cell 124, 27–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Lee I., Schindelin H. (2008) Structural insights into E1-catalyzed ubiquitin activation and transfer to conjugating enzymes. Cell 134, 268–278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Brzovic P. S., Lissounov A., Christensen D. E., Hoyt D. W., Klevit R. E. (2006) A UbcH5/ubiquitin noncovalent complex is required for processive BRCA1-directed ubiquitination. Mol. Cell 21, 873–880 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Knipscheer P., van Dijk W. J., Olsen J. V., Mann M., Sixma T. K. (2007) Noncovalent interaction between Ubc9 and SUMO promotes SUMO chain formation. EMBO J. 26, 2797–2807 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Bosanac I., Phu L., Pan B., Zilberleyb I., Maurer B., Dixit V. M., Hymowitz S. G., Kirkpatrick D. S. (2011) Modulation of K11-linkage formation by variable loop residues within UbcH5A. J. Mol. Biol. 408, 420–431 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Letunic I., Doerks T., Bork P. (2012) SMART 7. Recent updates to the protein domain annotation resource. Nucleic Acids Res. 40, D302–305 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Mace P. D., Linke K., Feltham R., Schumacher F. R., Smith C. A., Vaux D. L., Silke J., Day C. L. (2008) Structures of the cIAP2 RING domain reveal conformational changes associated with ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme (E2) recruitment. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 31633–31640 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Xu Z., Kohli E., Devlin K. I., Bold M., Nix J. C., Misra S. (2008) Interactions between the quality control ubiquitin ligase CHIP and ubiquitin conjugating enzymes. BMC Struct. Biol. 8, 26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Husnjak K., Dikic I. (2012) Ubiquitin-binding proteins. Decoders of ubiquitin-mediated cellular functions. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 81, 291–322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Edelmann M. J., Nicholson B., Kessler B. M. (2011) Pharmacological targets in the ubiquitin system offer new ways of treating cancer, neurodegenerative disorders and infectious diseases. Expert Rev. Mol. Med. 13, e35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Stoll K. E., Brzovic P. S., Davis T. N., Klevit R. E. (2011) The essential Ubc4/Ubc5 function in yeast is HECT E3-dependent, and RING E3-dependent pathways require only monoubiquitin transfer by Ubc4. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 15165–15170 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Maspero E., Mari S., Valentini E., Musacchio A., Fish A., Pasqualato S., Polo S. (2011) Structure of the HECT-ubiquitin complex and its role in ubiquitin chain elongation. EMBO Rep. 12, 342–349 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Samara N. L., Datta A. B., Berndsen C. E., Zhang X., Yao T., Cohen R. E., Wolberger C. (2010) Structural insights into the assembly and function of the SAGA deubiquitinating module. Science 328, 1025–1029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Sato Y., Yoshikawa A., Mimura H., Yamashita M., Yamagata A., Fukai S. (2009) Structural basis for specific recognition of Lys 63-linked polyubiquitin chains by tandem UIMs of RAP80. EMBO J. 28, 2461–2468 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Ozkan E., Yu H., Deisenhofer J. (2005) Mechanistic insight into the allosteric activation of a ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme by RING-type ubiquitin ligases. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 18890–18895 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]