Background: Mammalian eIF4B stimulates eIF4A helicase activity, but its function in promoting translation initiation in yeast is unclear.

Results: Yeast eIF4B enhances eIF4G·eIF4A association in vivo and in vitro.

Conclusion: yeIF4B stimulates eIF4F assembly by promoting an eIF4G HEAT domain conformation conducive for binding eIF4A.

Significance: A new function is established for eIF4B of supporting eIF4F assembly for mRNA activation.

Keywords: Protein Complexes, Protein-Protein Interactions, Translation Control, Translation Initiation Factors, Yeast, eIF4A, eIF4B, eIF4G, Yeast

Abstract

Translation initiation factor eIF4F (eukaryotic initiation factor 4F), composed of eIF4E, eIF4G, and eIF4A, binds to the m7G cap structure of mRNA and stimulates recruitment of the 43S preinitiation complex and subsequent scanning to the initiation codon. The HEAT domain of eIF4G stabilizes the active conformation of eIF4A required for its RNA helicase activity. Mammalian eIF4B also stimulates eIF4A activity, but this function appears to be lacking in yeast, making it unclear how yeast eIF4B (yeIF4B/Tif3) stimulates translation. We identified Ts− mutations in the HEAT domains of yeast eIF4G1 and eIF4G2 that are suppressed by overexpressing either yeIF4B or eIF4A, whereas others are suppressed only by eIF4A overexpression. Importantly, suppression of HEAT domain substitutions by yeIF4B overexpression was correlated with the restoration of native eIF4A·eIF4G complexes in vivo, and the rescue of specific mutant eIF4A·eIF4G complexes by yeIF4B was reconstituted in vitro. Association of eIF4A with WT eIF4G in vivo also was enhanced by yeIF4B overexpression and was impaired in cells lacking yeIF4B. Furthermore, we detected native complexes containing eIF4G and yeIF4B but lacking eIF4A. These and other findings lead us to propose that yeIF4B acts in vivo to promote eIF4F assembly by enhancing a conformation of the HEAT domain of yeast eIF4G conducive for stable binding to eIF4A.

Introduction

Selection of the translation initiation codon in eukaryotic mRNA generally occurs by the scanning mechanism, beginning with attachment of the small (40S) ribosomal subunit harboring the eIF2·GTP·Met-tRNAiMet ternary complex and various other initiation factors (the 43S PIC)2 to the 5′-untranslated region (5′-UTR) of the mRNA. This reaction is stimulated by eIF4F, bound to the m7G cap structure of the mRNA, composed of cap-binding protein eIF4E, eIF4G, and the DEAD-box RNA helicase eIF4A. Mammalian eIF4G acts as a scaffold harboring binding domains in its N terminus for poly(A)-binding protein (PABP) and eIF4E and in its middle and C-terminal regions for eIF4A and eIF3. Through its eIF4E and PABP binding domains and ssRNA-binding activity, eIF4G coordinates multiple, independent interactions with the mRNA to assemble a stable eIF4F·mRNA·PABP complex. The helicase activity of eIF4A is thought to generate an ssRNA binding site for the ribosome in the 5′-UTR, and in mammals, eIF4G·eIF3 association stabilizes interaction between this activated mRNP and the 43S PIC. After attaching to the mRNA, the 43S PIC scans the 5′-UTR for an AUG triplet, and AUG recognition triggers irreversible hydrolysis of the GTP bound to eIF2, with dissociation of eIF1 enabling release of Pi from eIF2-GDP, to produce a stable 48S PIC. Following release of eIF2-GDP, the large (60S) subunit joins to produce an 80S initiation complex competent for polypeptide synthesis (reviewed in Refs. 1 and 2).

eIF4A exhibits ATP-dependent RNA duplex unwinding activity that requires a closed conformation of its N- and C-terminal RecA-like domains. It is believed that eIF4A disrupts short RNA helices and binds to the resulting single strands in the ATP-bound state and that ATP hydrolysis releases eIF4A for another round of duplex melting (reviewed in Ref. 3). Association of eIF4A with eIF4G in the eIF4F complex activates its ATPase and helicase activities (4–6) and, accordingly, enhances the ability of eIF4A to stimulate translation initiation (7–11). The eIF4A-binding regions in yeast eIF4G consist of HEAT domains, each containing 10 α-helices that form a right-handed solenoid (12). Structural analysis of eIF4A·eIF4G complexes revealed that interactions of the RecA-like domains of eIF4A with different sets of α-helices in the HEAT domain juxtapose the ATP- and RNA-binding determinants in a partially closed conformation poised to interact with substrates and to release products (5, 13, 14). The association of eIF4A with the eIF4G·eIF4E subassembly of eIF4F is also expected to recruit eIF4A to the 5′-end of mRNAs, where it can generate an ssRNA binding site for the PIC in the 5′-UTR. Our recent findings indicate that yeast eIF4G imparts a preference in yeast eIF4A for unwinding duplexes with single-stranded 5′-overhangs, which also should help direct eIF4A to mRNA 5′-ends and provide 5′ to 3′ directionality to scanning (6).

In mammals, the ATPase and helicase activities of eIF4A are also stimulated by eIF4B (4), which contains multiple ssRNA-binding domains (15, 16); however, the activation mechanism is poorly understood. Direct interaction of eIF4B with eIF4A is not readily detected, although efficient complex formation occurs in the presence of ssRNA and ATP (17–19). Hence, eIF4B might stimulate helicase activity by enhancing domain closure in the eIF4A·ATP·mRNA complex, by stabilizing a conformation of this complex incompatible with mRNA duplex formation, or by helping to recruit eIF4A·ATP to single-stranded stretches in the mRNA. There is also evidence that eIF4B increases the efficiency of coupling ATP hydrolysis to duplex unwinding by eIF4F (20).

Beyond stimulating eIF4A helicase activity, it was suggested that mammalian eIF4B can promote ribosome attachment more directly by binding simultaneously to mRNA and 18S rRNA through its multiple RNA-binding domains (21) or by forming a protein bridge between the eIF4F·mRNP and eIF3 in the PIC (22). Other proposals envision a role for eIF4B in conferring 5′–3′ directionality to scanning. In one scenario, eIF4B interacts with eIF4A·eIF4G complexes bound to unwound mRNA at the exit channel of the 40S subunit to prevent backsliding of the PIC (23). In another model, eIF4A·eIF4G complexes disrupt helical structures in advance of the PIC, and eIF4B prevents reannealing of the unwound mRNA until it feeds into the 40S entry channel (18). Both models feature an eIF4G·eIF4A·eIF4B heterotrimer; however, there is evidence that eIF4A binding by eIF4G and eIF4B is mutually exclusive and that prior association with eIF4G enables eIF4A to form a stable mRNP with eIF4B following its dissociation from eIF4G (19).

Budding yeast harbors two eIF4G isoforms (1 and 2) that are ∼50% identical in sequence and related to mammalian eIF4G (24), except that the yeast proteins contain only one HEAT domain. The two yeast isoforms are functionally redundant (25), and either is sufficient for cell viability (24). The interactions of eIF4E and eIF4A with their respective binding domains in eIF4G1 or eIF4G2 are essential for efficient translation in vivo (9–11, 26). Yeast eIF4A and the yeast homolog of eIF4B (yeIF4B/Tif3) enhance the translation of reporter mRNAs with structured leaders but are also required for efficient translation of mRNAs with short unstructured 5′-UTRs (27, 28). Although yeIF4B is nonessential, tif3Δ cells grow poorly, especially at low temperatures (28).

The available genetic evidence is consistent with the possibility that yeIF4B stimulates translation in vivo by promoting eIF4F function (28, 29), and we showed previously that eIF4F and yeIF4B are both required for rapid recruitment of 43S PICs on native capped mRNAs in vitro (30). Surprisingly, however, yeIF4B does not stimulate eIF4A helicase activity in vitro (31), although yeast eIF4A can be activated by mammalian eIF4B (27) and mammalian eIF4B can functionally replace yeIF4B in a cell-free translation system (28). Thus, either the conditions required for activation of yeast eIF4A by yeIF4B remain to be identified, or this is not the critical function of yeIF4B. Moreover, direct interaction of yeIF4B with eIF4A or eIF4G has not been described. Hence, it is currently unclear how yeIF4B stimulates 48S PIC assembly and whether this function involves eIF4A-dependent or eIF4A-independent activities.

Interestingly, despite a relatively high affinity of yeast eIF4A for eIF4G in vitro (10, 30), interaction between eIF4G and eIF4A at native levels has not been detected in cell extracts under conditions where the eIF4E·eIF4G interaction, of similar affinity, is readily observed (9, 33–35). This situation stands in contrast to the relative ease of isolating intact eIF4F from mammalian cells (36). Accordingly, it has been suggested that eIF4G-eIF4A interaction in yeast cells is transient, being modulated by post-translational modifications or regulatory proteins, and depends on prior interaction of eIF4G with another factor that can expose the eIF4A binding site in the HEAT domain (10).

In the present study, we uncovered evidence for interaction between yeast eIF4G and yeIF4B in vivo that can restore complex formation between eIF4A and mutant eIF4G proteins harboring particular HEAT domain substitutions, and we reconstituted the ability of yeIF4B to rescue eIF4A·eIF4G interaction for one such mutant using purified components. We also found that yeIF4B enhances eIF4A·eIF4G interaction in vivo even in the case of WT eIF4G. Our results suggest that one aspect of yeIF4B function is to promote binding of eIF4A to the eIF4G·eIF4E subassembly of eIF4F with attendant recruitment of eIF4A to the cap structure of mRNA to promote 43S PIC attachment and subsequent scanning for the start codon.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Plasmids and Yeast Strains

All plasmids employed in this study are listed in Tables 1 and 2, and yeast strains are described in Table 3. Mutations in tif4631-HA-Bam or tif4632-HA were introduced into pEP88 or pEP41, respectively, by the QuikChange II site-directed mutagenesis system (Agilent Technologies) and verified by sequencing the entire coding sequence. Yeast strains YAS2282 and YAS2069 were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA). All novel yeast strains in Table 3 were constructed by introducing a TRP1 CEN4 plasmid with the appropriate TIF4631-HA or TIF4632-HA allele into YAS2282. The resulting transformants were replica-plated on 5-fluoroorotic acid medium lacking tryptophan (FOA−Trp) and incubated at 30 °C to evict the resident URA3 plasmid containing WT TIF4632 (37–39). No visible growth on FOA−Trp plates after 5–7 days indicated a lethal phenotype.

TABLE 1.

Yeast plasmids used in this study

| Yeast plasmid | Relevant feature | Source |

|---|---|---|

| pBAS2004 | TIF4632 URA3 CEN4 | Refs. 38 and 46 |

| pBAS2068 | TIF4632 TRP1 CEN4 | Ref. 38 |

| YCplac22 | sc TRP1 plasmid | Ref. 47 |

| pAS486 | p(HA)TIF4632 TRP1 CEN4 | Ref. 34 |

| pEP41a | TIF4632-HA TRP1 CEN4 | This study |

| pEP88 | TIF4631-HA-Bam TRP1 CEN4 | Ref. 39 |

| pEP81b | tif4632-HA-L574F TRP1 CEN4 | This study |

| pEP245b | tif4631-HA-Bam-L614F TRP1 CEN4 | This study |

| pEP256b | tif4631-HA-Bam-W579A TRP1 CEN4 | This study |

| pEP258b | tif4632-HA-M570K TRP1 CEN4 | This study |

| pEP259b | tif4631-HA-Bam-R835A/F838A TRP1 CEN4 | This study |

| pEP260b | tif4632-HA-W539A TRP1 CEN4 | This study |

| pEP261b | tif4632-HA-T578I TRP1 CEN4 | This study |

| pBAS3432 | TIF1 in hc URA3 plasmid | Ref. 9 |

| p3349c | TIF2 in hc URA3 plasmid | Ref. 48 |

| p3350c | TIF3 in hc URA3 plasmid | Ref. 48 |

| YEplac195 | hc URA3 plasmid | Ref. 47 |

| M3925 | trp1::KanMX3 | Ref. 40 |

| pFJZ043 | tif3Δ::hisG::URA3::hisG | This study |

| pRS315 | lc LEU2 plasmid | Ref. 49 |

| pEP329b | tif4632-HA-M570K in lc LEU2 plasmid | This study |

a This plasmid is identical to pAS486 except that a HpaI site within the ORF was eliminated by substituting one nt (TTA to TTG at codon 209) without changing the encoded amino acid sequence.

b Mutations producing the indicated amino acid substitutions in tif4631-HA-Bam or tif4632-HA were introduced into pEP88 or pEP41 by the QuikChange II site-directed mutagenesis system (Agilent Technologies).

c The hc plasmids derived from YEplac195 containing TIF2 or TIF3 (48) were renamed p3349 and p3350, respectively.

TABLE 2.

Bacterial plasmids used in this study

| Bacterial plasmid | Relevant feature | Source |

|---|---|---|

| pEPB26 | PT7lac-GST-TIF4632(504–914)-His6 PT7lac-CDC33 | This study |

| pEPB27 | PT7lac-GST-TIF4632(504–914)-L574F-His6 PT7lac-CDC33 | This study |

| pEPB29 | PT7lac-GST-TIF4632(504–914)-W539A-His6 PT7lac-CDC33 | This study |

TABLE 3.

Yeast strains used in this study

| Strain | Genotype | Source |

|---|---|---|

| YAS2282 | MATa ade2 his3 leu2 trp1 ura3 pep4::HIS3 tif4631::leu2hisg tif4632::ura3 pBAS2004 [pTIF4632 URA3 CEN4] | Ref. 46 |

| YAS2069 | MATa ade2-1 his3-11,15 leu2-3,111 trp1-1 ura3-1 pep4::HIS3 tif4631::LEU2 tif4632::ura3 pBAS2078 [pTIF4631 TRP1 CEN4] | Ref. 38 |

| YAS1951 | MATa ade2-1 his3-11,15 leu2-3,111 trp1-1 ura3-1 pep4::HIS3 tif4631::LEU2 tif4632::ura3 pBAS2068 [pTIF4632 TRP1 CEN4] | Ref. 38 |

| EPY41 | MATa ade2 his3 leu2 trp1 ura3 pep4::HIS3 tif4631::leu2hisg tif4632::ura3 pEP41 [TIF4632-HA TRP1 CEN4] | This study |

| EPY81 | MATa ade2 his3 leu2 trp1 ura3 pep4::HIS3 tif4631::leu2hisg tif4632::ura3 pEP81 [tif4632-HA-L574F TRP1 CEN4] | This study |

| EPY88 | MATa ade2 his3 leu2 trp1 ura3 pep4::HIS3 tif4631::leu2hisg tif4632::ura3 pEP88 [TIF4631-HA-Bam TRP1 CEN4] | Ref. 39 |

| EPY89 | MATa ade2 his3 leu2 trp1 ura3 pep4::HIS3 tif4631::leu2hisg tif4632::ura3 pEP81 [tif4632-HA-L574F TRP1 CEN4] p3350 [TIF3 in hc URA3 plasmid] | This study |

| EPY90 | MATa ade2 his3 leu2 trp1 ura3 pep4::HIS3 tif4631::leu2hisg tif4632::ura3 pEP81 [tif4632-HA-L574F TRP1 CEN4] pBAS3432 [TIF1 in hc URA3 plasmid] | This study |

| EPY91 | MATa ade2 his3 leu2 trp1 ura3 pep4::HIS3 tif4631::leu2hisg tif4632::ura3 pEP81 [tif4632-HA-L574F TRP1 CEN4] p3349 [TIF2 in hc URA3 plasmid] | This study |

| EPY139 | MATa ade2 his3 leu2 trp1 ura3 pep4::HIS3 tif4631::leu2hisg tif4632::ura3 pEP41 [TIF4632-HA TRP1 CEN4] p3350 [TIF3 in hc URA3 plasmid] | This study |

| EPY232 | MATa ade2 his3 leu2 trp1 ura3 pep4::HIS3 tif4631::leu2hisg tif4632::ura3 pEP81 [tif4632-HA-L574F TRP1 CEN4] YEplac195 [hc URA3 plasmid] | This study |

| EPY234 | MATa ade2 his3 leu2 trp1 ura3 pep4::HIS3 tif4631::leu2hisg tif4632::ura3 pEP41 [TIF4632-HA TRP1 CEN4] YEplac195 [hc URA3 plasmid] | This study |

| EPY245 | MATa ade2 his3 leu2 trp1 ura3 pep4::HIS3 tif4631::leu2hisg tif4632::ura3 pEP245 [tif4631-HA-Bam-L614F TRP1 CEN4] | This study |

| EPY246 | MATa ade2 his3 leu2 trp1 ura3 pep4::HIS3 tif4631::leu2hisg tif4632::ura3 pEP245 [tif4631-HA-Bam-L614F TRP1 CEN4] p3350 [TIF3 in hc URA3 plasmid] | This study |

| EPY247 | MATa ade2 his3 leu2 trp1 ura3 pep4::HIS3 tif4631::leu2hisg tif4632::ura3 pEP245 [tif4631-HA-Bam-L614F TRP1 CEN4] YEplac195 [hc URA3 plasmid] | This study |

| EPY248 | MATa ade2 his3 leu2 trp1 ura3 pep4::HIS3 tif4631::leu2hisg tif4632::ura3 pEP245 [tif4631-HA-Bam-L614F TRP1 CEN4] pBAS3432 [TIF1 in hc URA3 plasmid] | This study |

| EPY249 | MATa ade2 his3 leu2 trp1 ura3 pep4::HIS3 tif4631::leu2hisg tif4632::ura3 pEP245 [tif4631-HA-Bam-L614F TRP1 CEN4] p3349 [TIF2 in hc URA3 plasmid] | This study |

| EPY251 | MATa ade2 his3 leu2 trp1 ura3 pep4::HIS3 tif4631::leu2hisg tif4632::ura3 pEP88 [TIF4631-HA-Bam TRP1 CEN4] YEplac195 [hc URA3 plasmid] | This study |

| EPY252 | MATa ade2 his3 leu2 trp1 ura3 pep4::HIS3 tif4631::LEU2 tif4632::ura3 pBAS2078 [pTIF4631 TRP1 CEN4] p3350 [TIF3 in hc URA3 plasmid] | This study |

| EPY253 | MATa ade2 his3 leu2 trp1 ura3 pep4::HIS3 tif4631::LEU2 tif4632::ura3 pBAS2078 [pTIF4631 TRP1 CEN4] pBAS3432 [TIF1 in hc URA3 plasmid] | This study |

| EPY254 | MATa ade2 his3 leu2 trp1 ura3 pep4::HIS3 tif4631::LEU2 tif4632::ura3 pBAS2078 [pTIF4631 TRP1 CEN4] p3349 [TIF2 in hc URA3 plasmid] | This study |

| EPY255 | MATa ade2 his3 leu2 trp1 ura3 pep4::HIS3 tif4631::LEU2 tif4632::ura3 pBAS2078 [pTIF4631 TRP1 CEN4] YEplac195 [hc URA3 plasmid] | This study |

| EPY256 | MATa ade2 his3 leu2 trp1 ura3 pep4::HIS3 tif4631::leu2hisg tif4632::ura3 pEP256 [tif4631-HA-Bam-W579A TRP1 CEN4] | This study |

| EPY258 | MATa ade2 his3 leu2 trp1 ura3 pep4::HIS3 tif4631::leu2hisg tif4632::ura3 pEP258 [tif4632-HA-M570K TRP1 CEN4] | This study |

| EPY259 | MATa ade2 his3 leu2 trp1 ura3 pep4::HIS3 tif4631::leu2hisg tif4632::ura3 pEP259 [tif4631-HA-Bam-R835A/F838A TRP1 CEN4] | This study |

| EPY260 | MATa ade2 his3 leu2 trp1 ura3 pep4::HIS3 tif4631::leu2hisg tif4632::ura3 pEP260 [tif4632-HA-W539A TRP1 CEN4] | This study |

| EPY261 | MATa ade2 his3 leu2 trp1 ura3 pep4::HIS3 tif4631::leu2hisg tif4632::ura3 pEP261 [tif4632-HA-T578I TRP1 CEN4] | This study |

| EPY265 | MATa ade2 his3 leu2 trp1 ura3 pep4::HIS3 tif4631::leu2hisg tif4632::ura3 pEP258 [tif4632-HA-M570K TRP1 CEN4] p3350 [TIF3 in hc URA3 plasmid] | This study |

| EPY266 | MATa ade2 his3 leu2 trp1 ura3 pep4::HIS3 tif4631::leu2hisg tif4632::ura3 pEP258 [tif4632-HA-M570K TRP1 CEN4] pBAS3432 [TIF1 in hc URA3 plasmid] | This study |

| EPY267 | MATa ade2 his3 leu2 trp1 ura3 pep4::HIS3 tif4631::leu2hisg tif4632::ura3 pEP258 [tif4632-HA-M570K TRP1 CEN4] p3349 [TIF2 in hc URA3 plasmid] | This study |

| EPY268 | MATa ade2 his3 leu2 trp1 ura3 pep4::HIS3 tif4631::leu2hisg tif4632::ura3 pEP258 [tif4632-HA-M570K TRP1 CEN4] YEplac195 [hc URA3 plasmid] | This study |

| EPY278 | MATa ade2 his3 leu2 trp1 ura3 pep4::HIS3 tif4631::leu2hisg tif4632::ura3 pEP260 [tif4632-HA-W539A TRP1 CEN4] p3350 [TIF3 in hc URA3 plasmid] | This study |

| EPY279 | MATa ade2 his3 leu2 trp1 ura3 pep4::HIS3 tif4631::leu2hisg tif4632::ura3 pEP260 [tif4632-HA-W539A TRP1 CEN4] pBAS3432 [TIF1 in hc URA3 plasmid] | This study |

| EPY281 | MATa ade2 his3 leu2 trp1 ura3 pep4::HIS3 tif4631::leu2hisg tif4632::ura3 pEP260 [tif4632-HA-W539A TRP1 CEN4] YEplac195 [hc URA3 plasmid] | This study |

| EPY282 | MATa ade2 his3 leu2 trp1 ura3 pep4::HIS3 tif4631::leu2hisg tif4632::ura3 pEP261 [tif4632-HA-T578I TRP1 CEN4] p3350 [TIF3 in hc URA3 plasmid] | This study |

| EPY283 | MATa ade2 his3 leu2 trp1 ura3 pep4::HIS3 tif4631::leu2hisg tif4632::ura3 pEP261 [tif4632-HA-T578I TRP1 CEN4] pBAS3432 [TIF1 in hc URA3 plasmid] | This study |

| EPY285 | MATa ade2 his3 leu2 trp1 ura3 pep4::HIS3 tif4631::leu2hisg tif4632::ura3 pEP261 [tif4632-HA-T578I TRP1 CEN4] YEplac195 [hc URA3 plasmid] | This study |

| EPY286 | MATa ade2 his3 leu2 trp1 ura3 pep4::HIS3 tif4631::leu2hisg tif4632::ura3 pEP259 [tif4631-HA-Bam-R835A/F838A TRP1 CEN4] p3350 [TIF3 in hc URA3 plasmid] | This study |

| EPY287 | MATa ade2 his3 leu2 trp1 ura3 pep4::HIS3 tif4631::leu2hisg tif4632::ura3 pEP259 [tif4631-HA-Bam-R835A/F838A TRP1 CEN4] pBAS3432 [TIF1 in hc URA3 plasmid] | This study |

| EPY288 | MATa ade2 his3 leu2 trp1 ura3 pep4::HIS3 tif4631::leu2hisg tif4632::ura3 pEP259 [tif4631-HA-Bam-R835A/F838A TRP1 CEN4] p3349 [TIF2 in hc URA3 plasmid] | This study |

| EPY289 | MATa ade2 his3 leu2 trp1 ura3 pep4::HIS3 tif4631::leu2hisg tif4632::ura3 pEP259 [tif4631-HA-Bam-R835A/F838A TRP1 CEN4] YEplac195 [hc URA3 plasmid] | This study |

| EPY294 | MATa ade2-1 his3-11,15 leu2-3,111 trp1-1 ura3-1 pep4::HIS3 tif4631::LEU2 tif4632::ura3 pBAS2068 [pTIF4632 TRP1 CEN4] p3350 [TIF3 in hc URA3 plasmid] | This study |

| EPY297 | MATa ade2-1 his3-11,15 leu2-3,111 trp1-1 ura3-1 pep4::HIS3 tif4631::LEU2 tif4632::ura3 pBAS2068 [pTIF4632 TRP1 CEN4] YEplac195 [hc URA3 plasmid] | This study |

| FJZ001 | MATα/MATa his3-Δ1/his3-Δ1 leu2-Δ0/leu2-Δ0 met15-Δ0/MET15 LYS2/lys2-Δ0 ura3-Δ0/ura3-Δ0 TIF3/tif3::hisG | This study |

| FJZ046 | MATα his3-Δ1 leu2-Δ0 met15-Δ0 lys2-Δ0 ura3-Δ0 TIF3 | This study |

| FJZ052 | MATα his3-Δ1 leu2-Δ0 met15-Δ0 lys2-Δ0 ura3-Δ0 tif3Δ::hisG | This study |

| FJZ102 | MATα his3-Δ1 leu2-Δ0 met15-Δ0 lys2-Δ0 ura3-Δ0 trpΔ::KanMX tif3Δ::hisG | This study |

| FJZ107 | MATα his3-Δ1 leu2-Δ0 met15-Δ0 lys2-Δ0 ura3-Δ0 trpΔ::KanMX TIF3 | This study |

| BY4743 | MATα/MATa his3-Δ1/his3-Δ1 leu2-Δ0/leu2-Δ0 met15-Δ0/MET15 LYS2/lys2-Δ0 ura3-Δ0/ura3-Δ0 | Ref. 32 |

To construct the tif3Δ yeast strain used in Fig. 6, C–F, one TIF3 allele in diploid strain BY4743 was disrupted by using the tif3Δ::hisG-URA3-hisG cassette obtained from plasmid pFJZ043, selecting for Ura+ transformants, to produce strain FJZ001. Haploid strains FJZ052 (tif3Δ) and FJZ046 (TIF3) were obtained by isolating Ura+ and Ura− ascospore clones, respectively, by tetrad dissection after sporulation of FJZ001 and then eliminating the URA3 marker from the Ura+ isolate by counterselection on medium containing 5-FOA to generate the unmarked tif3Δ::hisG allele in FJZ052. The presence of tif3Δ in FJZ052 was verified by PCR analysis of chromosomal DNA using primers PZ001 (5′-AGTACCAGATTGAGCTCAGC-3′), PZ002 (5′-CGAGCTTCGCTTATAGTCAT-3′), and PZ004 (5′-CCCGAATTCCCAAGAAGAGGGGGAGGTGC-3′). To construct trp1Δ strains FJZ102 (tif3Δ) and FJZ107 (WT), FJZ001 was transformed with the trp1Δ::KanMX3 fragment obtained from plasmid M3925 (40), followed by tetrad dissection of a sporulated KanR diploid transformant to obtain a Trp− Ura+ ascospore and subsequent counterselection on 5-FOA medium to evict URA3 from the tif3Δ::hisG-URA3-hisG allele.

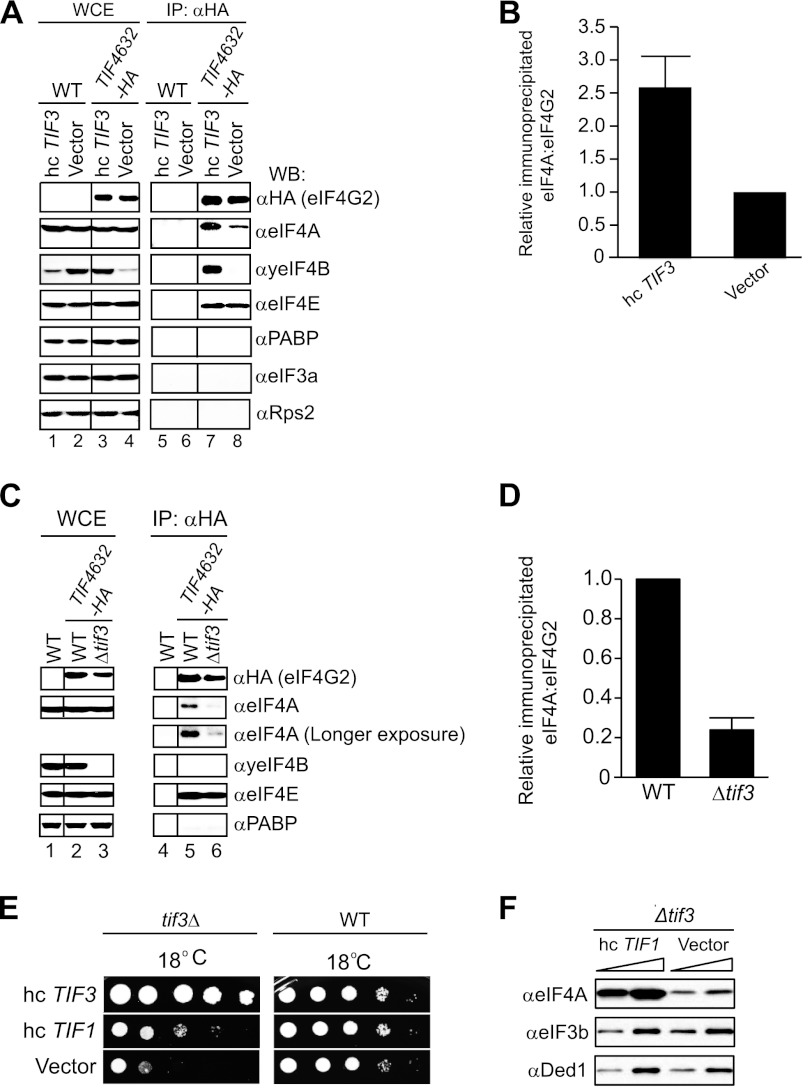

FIGURE 6.

yeIF4B promotes association between eIF4A and wild-type eIF4G in vivo. A, overexpression of yeIF4B enhances association of eIF4A with WT eIF4G2-HA in vivo. Shown is co-IP analysis of WT eIF4G2-HA using transformants of strain harboring hc TIF3 plasmid (EPY139) or empty vector (EPY234) (lanes 3 and 4 and lanes 7 and 8) and cognate transformants of control untagged strains (EPY294 and EPY297) (lanes 1 and 2 and lanes 5 and 6), conducted as described in Fig. 3, D–F, except that antibodies against eIF3a/Tif32 and 40S protein Rps2 were included. B, seven independent co-IP experiments were conducted as in A, and WB signals for eIF4A and eIF4G2 were quantified by videodensitometry using National Institutes of Health ImageJ software. eIF4A/eIF4G2 ratios were calculated for the hc TIF3 transformants and normalized to the corresponding ratios for empty vector transformants, and the mean ± S.E. (error bars) ratios are plotted. C, elimination of yeIF4B weakens association of eIF4A with WT eIF4G2-HA in vivo. Shown is co-IP analysis of transformants of isogenic WT (FJZ107) and tif3Δ (FJZ102) strains harboring TIF4632-HA plasmid pEP41 (lanes 2 and 3 and lanes 5 and 6) and the WT strain harboring empty vector (YCplac22) (lanes 1 and 4) carried out as in A. D, quantification of results from eight independent co-IP experiments conducted as in C. E, growth phenotypes of transformants of tif3Δ (FJZ052) and WT (FJZ046) strains harboring the indicated hc plasmids were assessed as in Fig. 1, A–C, except that cells were incubated at 18 °C for 9 days (tif3Δ) or 4 days (WT). F, WB analysis of WCEs from the relevant tif3Δ strains described in E using antibodies against eIF4A and eIF3b/Ded1 (as loading controls). Samples in A and C were run on the same gels, respectively, but rearranged for comparative purposes. The rearrangements are indicated by dividing lines.

Coimmunoprecipitation and Immunoblot Analysis

Yeast strains were grown in 100 ml of SC−Trp also lacking uracil (SC−Ura,−Trp) to an A600 of 0.5–0.8, and whole cell extracts (WCEs) were prepared as described previously (39). For coimmunoprecipitation, 1–3 mg of prepared WCEs were diluted with lysis buffer (50 mm Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 50 mm NaCl, 0.1% Triton X-100, 10% glycerol, 1 mm EDTA, 10 μg/ml aprotinin, 10 μg/ml leupeptin, 10 μg/ml pepstatin, 1 mm 4-(2-aminoethyl) benzenesulfonyl fluoride, 1 mm DTT, Complete protease inhibitor mixture tablets (EDTA-free, Roche Applied Science)) to 500 μl and incubated with 12.5 μg of agarose-conjugated anti-HA antibodies overnight at 4 °C with rocking. Immune complexes captured on agarose beads were collected by centrifugation and washed twice with 500 μl of lysis buffer (without protease inhibitors). The complexes were then incubated at 26 °C for 30 min in the presence or absence of RNases A and T1, washed twice with 500 μl of lysis buffer (without protease inhibitors), and resuspended in 40 μl of 2× Laemmli sample buffer. After boiling for 5 min, samples were resolved by 4–20% SDS-PAGE, transferred to PVDF membranes, and probed with appropriate antibodies. Immune complexes were visualized by ECL (GE Healthcare) according to the manufacturer's instructions. For Western blot analysis of WCEs for Fig. 1, E and F, extracts were prepared by trichloroacetic acid extraction, as described previously (41).

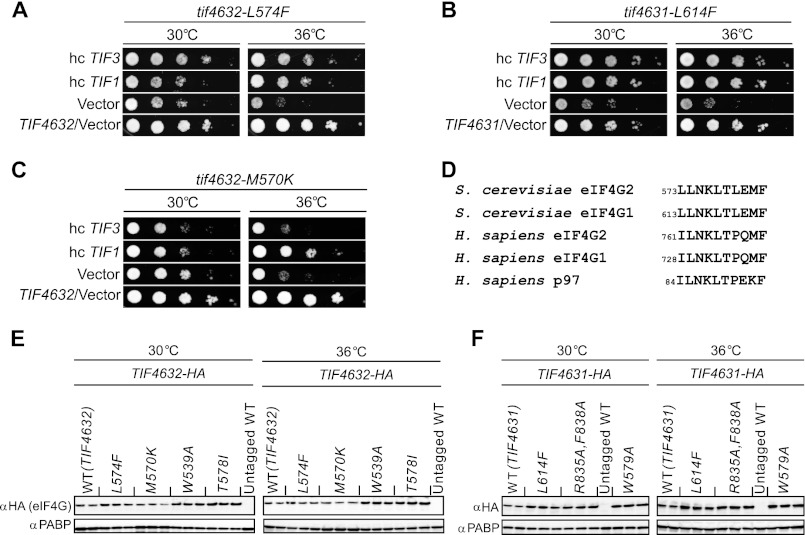

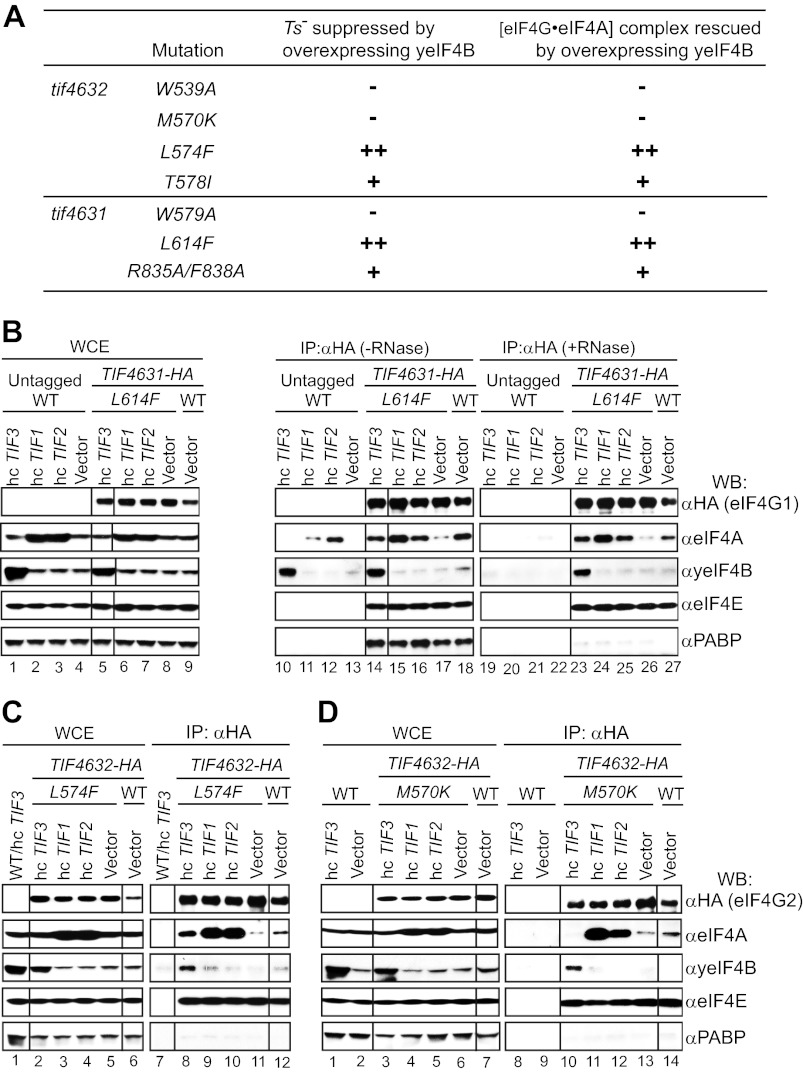

FIGURE 1.

Overexpression of yeIF4B reduces the Ts− phenotypes of particular substitutions in the HEAT domains of eIF4G1 and eIF4G2. A–C, an hc plasmid containing TIF1 (pBAS3432), TIF3 (p3350), or an empty vector (YEplac195) was introduced into the following yeast strains harboring the indicated tif4632-HA or tif4631-HA mutant alleles as the only source of eIF4G: EPY81 (tif4632-L574F), EPY245 (tif4631-L614F), and EPY258 (tif4632-M570K) in A–C, respectively. These transformants, plus an empty vector transformant of TIF4632 strain EPY234, were spotted in serial 10-fold dilutions on SC−Trp,−Ura and incubated at 30 or 36 °C for 2 days. D, amino acid sequence alignments of known eIF4G and eIF4G-related proteins. E and F, WB analyses of HA-tagged eIF4G proteins in WCEs. Yeast strains harboring the indicated TIF4632-HA alleles (E) or TIF4631-HA alleles (F) were cultured at 30 °C in SC-Trp to A600 of 0.2–0.4 and shifted to the indicated temperatures for 7 h. WCEs were prepared under denaturing conditions and subjected to WB analysis with antibodies against HA or PABP (to provide a loading control). The following HA-tagged strains were analyzed: EPY41, EPY81, EPY258, EPY260, EPY261, EPY88, EPY245, EPY259, and EPY256. Two to three independent transformants from each strain were examined for the WB analysis. Untagged WT strains YAS1951 and YAS2069 were examined in parallel as controls.

Antibodies

Rat polyclonal anti-Tif3, rabbit polyclonal anti-eIF4A, mouse monoclonal anti-PABP, rabbit polyclonal anti-eIF4E, anti-Rps2, and rabbit polyclonal anti-Ded1 antibodies were kind gifts from M. Altmann, P. Linder, M. S. Swanson, J. E. G. McCarthy, J. Warner, and T. Chang, respectively. Mouse monoclonal anti-HA antibodies for immunoblotting and immunoprecipitation were purchased from Roche Applied Science and Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. (Santa Cruz, CA), respectively. Antibodies directed against Tif32 (42) and Rps2 (43) were described previously.

Recombinant Protein Production and Purification

Tetramethylrhodamine-labeled eIF4A (eIF4A-RH) (6, 30), yeIF4B (30, 44), and GST-eIF4G2(504–914) (WT, L574F, or W539A) (30, 39) were purified as described previously.

Fluorescence Anisotropy Assays

Fluorescence anisotropy measurements of equilibrium binding constants (Kd) were performed as described previously with minor modifications (6, 30, 45). Briefly, to examine the effect of yeIF4B on GST-eIF4G2(504–914)·eIF4A-RH complex formation, eIF4A-RH (30 nm) was mixed with yeIF4B (1 μm) in 300 μl of 1× Recon buffer (30 mm HEPES-KOH (pH 7.4), 100 mm KOAc (pH 7.6), 3 mm Mg(OAc)2, 2 mm DTT) in a quartz cuvette. Micrococcal nuclease-treated/purified GST-eIF4G2(504–914) proteins were added, and the fluorescence anisotropy of eIF4A-RH was measured on a Spex Fluorolog-3 spectrofluorometer (Horiba Jobin Yvon) with an excitation wavelength of 550 nm and emission wavelength of 580 nm. As controls, Kd values for GST-eIF4G2(504–914)·eIF4A-RH complexes were determined in the absence of yeIF4B. Dissociation constants were calculated by fitting the anisotropy data to a hyperbolic function using Kaleidagraph software (Synergy).

RESULTS

Overexpression of yeIF4B Suppresses Particular eIF4G Mutations Affecting the eIF4A/eIF4G Interface

To shed light on the role of yeIF4B in promoting eIF4F function in vivo, we isolated point mutations in the gene encoding eIF4G2 (TIF4632) that confer temperature-sensitive (Ts−) growth and screened them for suppression of this phenotype by overexpressing WT yeIF4B from a high copy (hc) TIF3 plasmid. Point mutations were generated at random in a single-copy plasmid-borne HA-TIF4632 allele, encoding eIF4G2 with an N-terminal HA tag and driven by the TIF4632 promoter, and mutant alleles were introduced by plasmid-shuffling into a strain harboring disruptions of the genomic alleles encoding eIF4G1 and eIF4G2. Hence, the plasmid-encoded gene products are the only eIF4G proteins present in the cells and are expressed at levels similar to that of native eIF4G2. Ten different Ts− alleles were thus identified, six of them harboring at least one mutation in the HEAT domain. Overexpressing eIF4A from an hc TIF1 plasmid suppressed the Ts− phenotypes of the mutants containing substitutions in the HEAT domain (data not shown), as expected if the mutations weaken eIF4G2-eIF4A interaction in the manner described previously for other HEAT domain substitutions (9). Interestingly, the Ts− phenotype of one of the mutants was also suppressed by overexpressing yeIF4B (data not shown), raising the possibility that a high concentration of yeIF4B can overcome a defective interaction between eIF4A and the eIF4G2 mutant. Because the TIF4632 allele of interest harbored multiple mutations, site-directed mutagenesis was employed to generate a panel of alleles with single mutations. The outcome of this analysis was that the tif4632-L574F mutation (henceforth referred to as L574F) was found to be necessary and sufficient for the Ts− phenotype displayed by the original compound mutation (data not shown), and, importantly, the Ts− phenotype conferred by L574F is mitigated by overexpressing either yeIF4B or eIF4A in the mutant cells (Fig. 1A, hc TIF3 and hc TIF1 versus vector, 36 °C).

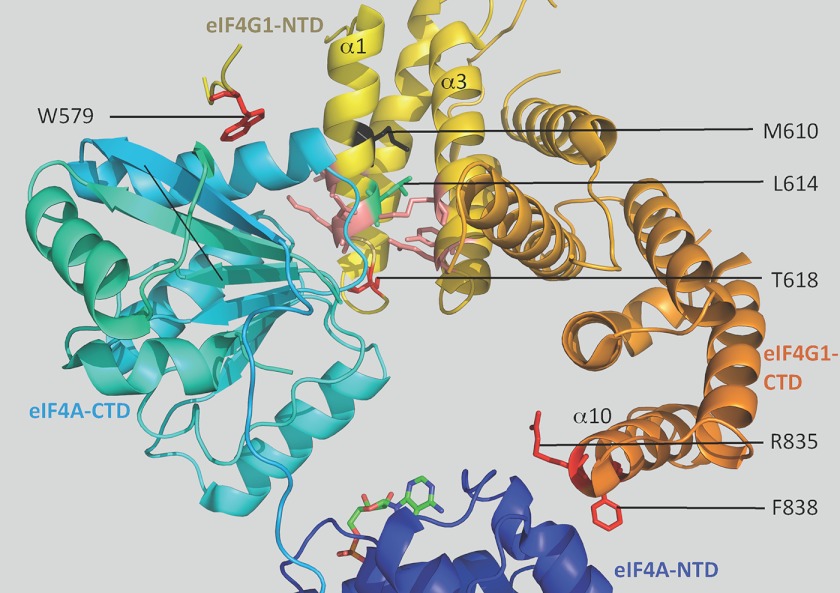

The HEAT domains of eIF4G2 and eIF4G1 are highly similar (24), and the Leu residue in eIF4G2 altered by L574F aligns with Leu-614 of yeast eIF4G1 (Fig. 1D). Because a crystal structure of the complex between yeast eIF4A and the eIF4G1 HEAT domain is available (5), we examined the phenotype of the corresponding Phe substitution at Leu-614 of eIF4G1. Remarkably, the tif4631-L641F mutation likewise confers a Ts− phenotype that is efficiently suppressed by overexpressing yeIF4B or eIF4A (Fig. 1B, 36 °C). As illustrated in Fig. 2, Leu-614 is located near the end of helix α1 of the HEAT domain of eIF4G1, close to several residues in α1 or the α1-α2 turn that make side chain contacts with residues in the eIF4A CTD (5). Because the side chain of Leu-614 projects into the HEAT domain rather than outward toward eIF4A (Fig. 2), its replacement with Phe would presumably weaken eIF4G HEAT domain interactions with the eIF4A-CTD indirectly. It might perturb the orientation of helix α1 in a way that weakens its contacts with eIF4A, or it might alter the disposition of nearby residues in helix α3 that make additional contacts with eIF4A (5) (Fig. 2). We envisioned that interaction of yeIF4B with the mutant eIF4G-HEAT domain, driven by the elevated cellular concentration of yeIF4B, would compensate for such perturbations of the eIF4A·eIF4G interface, either by restoring the WT conformation of HEAT domain helices or by interacting simultaneously with eIF4A and eIF4G to bridge their interaction within a hypothetical eIF4A·eIF4G·eIF4B trimeric complex.

FIGURE 2.

Structural details of the yeast eIF4G1/eIF4A interface. Shown is a ribbon diagram of a portion of the x-ray crystal structure of the complex of yeast eIF4A·AMP and the HEAT domain of eIF4G1 (Protein Data Bank code 2VSO), with helices α1, α3, and α10 of the HEAT domain labeled. Stick depictions of the side chains of selected residues are shown in different colors. Red- and salmon-colored residues make side chain contacts with eIF4A residues, including eIF4G1 residues Ser-612, Asn-615, and Lys-616 in α1 and Lys-655 and Glu-659 in α3 (5).

It should be noted that neither L574F nor L614F reduces the steady-state level of the cognate eIF4G protein in cells grown at 30 or 36 °C, as judged by Western blot (WB) analysis of WCEs using anti-HA antibodies (Fig. 1, E and F). Indeed, the mutants (except for M570K) are expressed at levels somewhat higher than the corresponding WT proteins. Thus, the mechanism of suppression by yeIF4B overexpression does not involve rescue of unstable mutant eIF4G proteins.

We reasoned that if yeIF4B overexpression suppresses the L574F and L614F substitutions by simply bridging the interaction of eIF4A with eIF4G in a trimeric complex, then it might be possible to suppress other HEAT domain substitutions that weaken the eIF4A/eIF4G interface. To test this idea, we first used site-directed mutagenesis to identify M570K as the substitution responsible for the Ts− phenotype of a second compound mutation we had identified in eIF4G2 that is suppressed by overexpressing eIF4A but not yeIF4B (data not shown). The Ts− phenotype of the single M570K mutation is suppressed by eIF4A overexpression to roughly the same extent seen for L574F (cf. 36 °C for hc TIF1 in Fig. 1, A and C); however, yeIF4B overexpression has no impact on growth of the M570K strain (Fig. 1C, hc TIF3, 36 °C).

Interestingly, Met-610, the eIF4G1 residue corresponding to that altered in eIF4G2-M570K is only one helical turn from Leu-614 in helix α1; however, Met-610 lies deeper in the HEAT domain and farther from the eIF4A interface (5) (Fig. 2). Moreover, M570K would introduce a positively charged side chain into the interior of the HEAT domain. Accordingly, it seemed likely that M570K would alter the tertiary structure of the HEAT domain more substantially than would L574F. Indeed, whereas we could purify a recombinant fragment of eIF4G2-L574F for in vitro experiments described below, the corresponding fragment of eIF4G2-M570K was degraded during purification (data not shown). In addition, eIF4G2-M570K is expressed at a level somewhat below that of WT eIF4G2 (Fig. 1E). These findings are compatible with a model in which overexpressed yeIF4B suppresses the L574F substitution by restoring the native orientation of α1 or α3 residues in the HEAT domain that interact directly with the eIF4A-CTD, whereas this mechanism is not effective for M570K because it provokes a more severe disruption of HEAT domain structure and protein stability. As discussed below, the reduced expression level of the M570K mutant contributes to its inability to be rescued by excess yeIF4B.

We also examined substitutions in eIF4G residues that make direct side chain contacts with eIF4A, reasoning that these alterations would be less efficiently rescued by overexpressed yeIF4B if the latter acts primarily to correct a non-productive orientation of α-helices in the HEAT domain. It was shown that a segment of eIF4G1 located N-terminal to the HEAT domain, which includes Trp-579, interacts with a hydrophobic groove on the surface of the eIF4A-CTD, outside of the primary eIF4A·eIF4G1-HEAT interface (Fig. 2). The W579A substitution weakens eIF4A binding to eIF4G1 in vitro and confers a Ts− phenotype in vivo (5). Consistent with this, we observed Ts− phenotypes for both eIF4G1-W579A and the corresponding eIF4G2-W539A mutant, and, as might be expected, overexpression of eIF4A partially suppressed these growth defects; however, overexpression of yeIF4B had no effect on the Ts− phenotypes of either mutant (Fig. 3A, 36 °C) (data not shown). Thus, the effects of eliminating these eIF4G·eIF4A contacts located outside of the HEAT domains of eIF4G1 or eIF4G2 cannot be rescued by excess yeIF4B. Importantly, both eIF4G1-W579A and eIF4G2-W539A are expressed at levels greater than or equal to that of eIF4G1-L614F and eIF4G2-L574F at 30 or 36 °C (Fig. 1, E and F), indicating that the failure to rescue the W579A and W539A substitutions by excess yeIF4B cannot be attributed to lower abundance of the eIF4G mutant proteins.

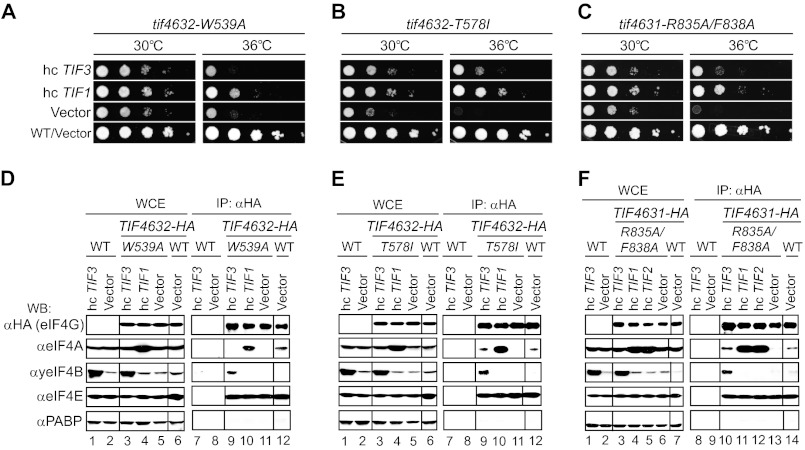

FIGURE 3.

Overexpressing yeIF4B reduces the Ts− phenotype and rescues the interaction defect of eIF4A with particular eIF4G substitution mutants. A–C, growth phenotypes of the indicated tif4632 or tif4631 mutant strains harboring hc plasmids containing TIF3 or TIF1 or an empty vector were assessed as in Fig. 1, A–C, using the following strains: EPY278, EPY279, EPY281, EPY234, EPY282, EPY283, EPY285, EPY286, EPY287, EPY289, and EPY251. D–F, the strains described in A–C plus EPY288, EPY294/EPY252 (untagged WT TIF4632/1 strain harboring hc TIF3 plasmid), or EPY297/EPY255 (empty vector) were cultured at 30 °C in SC−Ura,−Trp to an A600 of 0.5–0.8. WCEs were immunoprecipitated with anti-HA antibodies, and immune complexes were treated with RNases A and T1 and subjected to WB analysis using antibodies listed on the left. Aliquots of 2.5% input extracts (WCE lanes) or 12.5–37.5% immune complexes (IP: αHA lanes) were examined. Lanes 1 and 2 and lanes 7 and 8 in D–E and lanes 1 and 2 and lanes 8 and 9 in F contain samples from the untagged WT control strains. Samples in D–F were run on the same gels, respectively, but rearranged for comparative purposes. The rearrangements are indicated by dividing lines.

We also made an Ile substitution of Thr-618 in the α1-α2 turn of eIF4G1 (Fig. 2), shown to confer a Ts− phenotype (11), which should eliminate a hydrogen bond with eIF4A-CTD residue Thr-286 (5), plus an Ile substitution of the corresponding eIF4G2 residue Thr-578. In addition, we made single and double Ala substitutions of two residues in the last (10th) helix of the eIF4G HEAT domain that make direct contacts with the eIF4A-NTD, Arg-835 and Phe-838 in eIF4G1 (Fig. 2) and Arg-795 and Phe-798 in eIF4G2. The eIF4G1-T618I and eIF4G2-R795A/F798A substitutions were lethal (data not shown), whereas the corresponding eIF4G2-T578I and eIF4G1-R835A/F838A substitutions conferred Ts− phenotypes that were mitigated by eIF4A overexpression. These latter mutations were also partially suppressed by yeIF4B overexpression (Fig. 3, B and C, 36 °C); however, in contrast to the situation above for eIF4G2-L574F and eIF4G1-L614F (Fig. 1, A and B), the Ts− phenotypes of eIF4G2-T578I and eIF4G1-R835A/F838A were suppressed more efficiently by eIF4A than by yeIF4B overexpression (Fig. 3, B and C, hc TIF1 versus hc TIF3, 36 °C). Again, the less efficient suppression of these last mutants cannot be attributed to lower protein abundance because the steady-state levels of eIF4G2-T578I and eIF4G1-R835A/F838A are equal to or greater than those of the highly suppressible eIF4G2-L574F and eIF4G1-L614F mutants (Fig. 1, E and F).

Suppression of eIF4G-HEAT Mutations Is Correlated with Rescue of Native eIF4G·eIF4A Complexes in Cell Extracts

We wished to test our hypothesis that yeIF4B overexpression can rescue complex formation between eIF4A and a subset of eIF4G-HEAT mutants in vivo. Accordingly, we immunoprecipitated WCEs with anti-HA antibodies and measured by WB analysis the amounts of eIF4A that coimmunoprecipitate with HA-eIF4G proteins in the presence or absence of yeIF4B overexpression. As noted above, association of yeast eIF4A with WT eIF4G has not been observed in whole cell extracts at native levels of eIF4A and eIF4G expression (9, 35). However, we succeeded in coimmunoprecipitating a small fraction of eIF4A with WT HA-eIF4G1 from WCEs in a manner judged to be specific by the failure to coimmunoprecipitate eIF4A with untagged eIF4G (Fig. 4B, lane 18 versus lane 13, αeIF4A). This interaction was at least partially resistant to treatment of immune complexes with RNases A and T1, as was the co-immunoprecipitation (co-IP) of eIF4E with HA-eIF4G1 (Fig. 4B, lane 27 versus lane 18, αeIF4A and αeIF4E). In agreement with our previous results, co-IP of PABP with HA-eIF4G1 was greatly reduced by RNase treatment (Fig. 4B, lane 27 versus lane 18, αPABP) because the PABP-eIF4G interaction does not withstand co-IP analysis without the stabilizing influence of polyadenylated mRNA (39). In some experiments, a small amount of yeIF4B was also recovered specifically with WT HA-eIF4G in RNase-treated immune complexes (Fig. 4B, lane 27 versus lane 22, αyeIF4B), which in all cases was increased dramatically on yeIF4B overexpression (lane 23 versus lane 19).

FIGURE 4.

Correlation between the ability of overexpressed yeIF4B to suppress the Ts− phenotype and rescue defective interaction of eIF4A·eIF4G conferred by eIF4G substitutions. A, summary of the ability of yeIF4B overexpression to restore cell growth at 36 °C and the coimmunoprecipitation of native eIF4A·eIF4G complexes for different eIF4G mutants. Results from Figs. 1 and 3 and B–D below are summarized qualitatively. Note that increasing the abundance of the M570K variant above the WT level allows yeIF4B overexpression to partially suppress the Ts− phenotype and to restore the M570K-eIF4A interaction defect (see supplemental Fig. S1). B, the hc TIF1, hc TIF3, and empty vector transformants of the tif4631-HA-L614F mutant described in Fig. 1B or a hc TIF2 transformant of the same strain (EPY249) and an empty vector transformant of isogenic TIF4631-HA strain (EPY251) were cultured as in Fig. 3, D–F, along with transformants of untagged WT TIF4631 strain harboring the same plasmids as negative controls (EPY252, EPY253, EPY254, and EPY255; lanes 1–4, 10–13, and 19–22). WCEs were immunoprecipitated with anti-HA antibodies. Immune complexes were incubated at 26 °C for 30 min in the presence (lanes 19–27) or absence (lanes 10–18) of RNases A and T1 and subjected to WB analysis with antibodies listed on the right. Aliquots of 2.5% input extracts (WCE lanes) or 12.5–37.5% immune complexes (IP: αHA lanes) were examined. C and D, similar to B except using transformants of the tif4632-HA-L574F and tif4632-HA-M570K mutants described in Fig. 1, A and C, respectively, and hc TIF3 or vector transformants of untagged WT TIF4632 strain and examining only RNase-treated immune complexes. Samples in B–D were run on the same gels, respectively, but rearranged for comparative purposes. The rearrangements are indicated by dividing lines.

Having established an assay for native eIF4G·eIF4A complexes, we tested the prediction of our genetic analysis (summarized in Fig. 4A) that the L614F substitution weakens eIF4G1 association with eIF4A in a manner rescued by yeIF4B overexpression. Indeed, L614F clearly reduced the amount of coimmunoprecipitating eIF4A compared with that seen for WT eIF4G1, with or without RNase treatment (Fig. 4B, lane 17 versus lane 18 and lane 26 versus lane 27, αeIF4A). Furthermore, overexpressing eIF4A1 (encoded by TIF1) or eIF4A2 (TIF2) rescued the co-IP of eIF4A with the L614F mutant (Fig. 4B, lanes 24 and 25 versus lane 26, αeIF4A). Note that this last conclusion should be restricted to RNase-treated complexes because overexpressed eIF4A shows nonspecific association with immune complexes prepared with WCEs containing only untagged eIF4G (Fig. 4B, lanes 11 and 12 versus lane 13, αeIF4A). Importantly, overexpressing yeIF4B also produced a marked increase in the amount of eIF4A coimmunoprecipitating with eIF4G1-L614F (Fig. 4B, lane 23 versus lane 26, αeIF4A) without affecting the steady-state level of eIF4A in the WCE (Fig. 4B, lanes 5 and 8, αeIF4A). Overexpressing yeIF4B had no effect on the amount of eIF4E that coimmunoprecipitated with eIF4G1-L614F (Fig. 4B, lane 23 versus lane 26, αeIF4E), indicating that yeIF4B specifically stimulates eIF4A association with the mutant eIF4G1 protein. As mentioned above, analysis of the RNase-treated complexes revealed that overexpressing yeIF4B also increases its own association with eIF4G1-L614F (Fig. 4B, lane 23 versus lane 26, αyeIF4B). These findings support our conclusion that the L614F substitution in eIF4G1 disrupts its interaction with eIF4A in a manner rescued by elevated levels of yeIF4B in a manner associated with increased binding of yeIF4B to the mutant eIF4G1 protein. The fact that the co-IP of yeIF4B with eIF4G1 in cells overexpressing yeIF4B is resistant to RNase treatment (Fig. 4B, lane 14 versus lane 23, αyeIF4B) suggests that the enhanced level of yeIF4B·eIF4G complexes seen under these conditions does not depend on tethering of these two proteins to the same mRNA molecules.

We extended the co-IP analysis to include the corresponding eIF4G2-L574F substitution, whose Ts− phenotype is also suppressed by yeIF4B overexpression (genetic data summarized in Fig. 4A), with similar results. In this and all subsequent experiments, we employed RNase treatment to eliminate nonspecific recovery of eIF4A and yeIF4B in immune complexes when they are overexpressed. As shown in Fig. 4C, the L574F substitution reduces the amount of eIF4A that coimmunoprecipitates with the mutant HA-eIF4G2 protein (lane 11 versus lane 12, αeIF4A), and overexpressing eIF4A or yeIF4B increases the level of coimmunoprecipitating eIF4A above that seen for WT HA-eIF4G2 (lanes 8–10 versus lanes 11 and 12, αeIF4A). Furthermore, overexpressing yeIF4B increases the amount of yeIF4B itself coimmunoprecipitated with the eIF4G2 mutant above that seen for WT eIF4G2 (lane 8 versus lane 12, αyeIF4B). Thus, suppression of the eIF4G2-L574F substitution by yeIF4B overexpression is associated with restoration of its interaction with eIF4A and also an elevated, RNase-resistant interaction with yeIF4B.

Quite different results were obtained for the eIF4G2-M570K and eIF4G2-W539A substitutions, whose Ts− phenotypes are not suppressed by yeIF4B overexpression (summarized in Fig. 4A). As shown in Fig. 4D, the M570K substitution evokes the expected reduction in the co-IP of eIF4A with the mutant HA-eIF4G2 protein (lane 13 versus lane 14, αeIF4A), and overexpressing eIF4A increases the amount of coimmunoprecipitating eIF4A above that seen for WT HA-eIF4G2 (lanes 11 and 12 versus lanes 13 and 14, αeIF4A). Moreover, overexpressing yeIF4B increases the amount of yeIF4B itself associated with the eIF4G2-M570K mutant (lane 10 versus lane 13, αyeIF4B); however, it does not increase the co-IP of eIF4A with the mutant eIF4G2 protein (lanes 10 and 13, αeIF4A). Similar results were obtained for the eIF4G2-W539A substitution in Fig. 3D, where it can be seen that overexpressing eIF4A, but not yeIF4B, rescues the impaired interaction of this eIF4G2 variant with eIF4A (lanes 9–12, αeIF4A), despite increased association of yeIF4B with the eIF4G2 mutant (lane 9 versus lane 11, αyeIF4B). Thus, in accordance with the genetic data (Fig. 4A), overexpressing yeIF4B does not restore eIF4A association with the eIF4G2-M570K or eIF4G2-W539A variants in vivo, although these mutants interact effectively with yeIF4B itself.

We also conducted co-IP analysis for the eIF4G2-T578I and eIF4G1-R835A/F838A variants, whose genetic suppression by yeIF4B overexpression is appreciable but less extensive than that given by eIF4A overexpression in the same mutants and also less extensive than that seen for the L614F/L574F substitutions of eIF4G1/eIF4G2 (as summarized in Fig. 4A). In both cases, overexpression of yeIF4B leads to detectable co-IP of eIF4A with the mutant eIF4G proteins; however, the amount of co-precipitating eIF4A is below that achieved by overexpressing eIF4A (Fig. 3, E (lanes 9–11) and F (lanes 10–13)). We found reproducibly in several independent experiments that the amounts of eIF4A that coimmunoprecipitated with these two mutant proteins on overexpressing yeIF4B versus overproducing eIF4A differed more substantially than that seen for the eIF4G1-L614F and eIF4G2-L574F mutants discussed above. Thus, the relative efficiency of suppression of the Ts− phenotypes of different eIF4G variants correlates well with the relative amounts of eIF4A that coimmunoprecipitated with the mutant proteins in cells overexpressing yeIF4B (summarized in Fig. 4A).

Finally, we examined the possibility that the failure of yeIF4B overexpression to rescue the eIF4G2-M570K mutant might reflect the relatively lower abundance of this variant compared with all others we examined for suppression (Fig. 1, E and F). To this end, we introduced extra copies of the M570K allele on a second low copy plasmid, which predictably increased the steady-state level of this variant above that of WT eIF4G2 (supplemental Fig. S1B, compare Sc versus Lc lanes). Introducing additional copies of M570K alone does not improve cell growth (supplemental Fig. S1A, row 2 versus row 4); nor does it increase the amount of eIF4A that coimmunoprecipitates with this eIF4G2 mutant (supplemental Fig. S1C, lanes 12 and 13). However, overexpressing yeIF4B confers a detectable improvement of growth by the cells harboring extra copies of the M570K allele (supplemental Fig. S1A, row 1 versus row 3). Excess yeIF4B also increases the amount of eIF4A that coimmunoprecipitates with the M570K mutant (Fig. S1C, lane 11 versus lane 13). These findings extend the correlation summarized in Fig. 4A between suppression of the Ts− phenotypes of eIF4G mutants and restoration of their association with eIF4A on yeIF4B overexpression. Presumably, under the stimulatory influence of excess yeIF4B, the increased abundance of the eIF4G2-M570K mutant achieved in these last experiments drives complex formation with eIF4A by mass action.

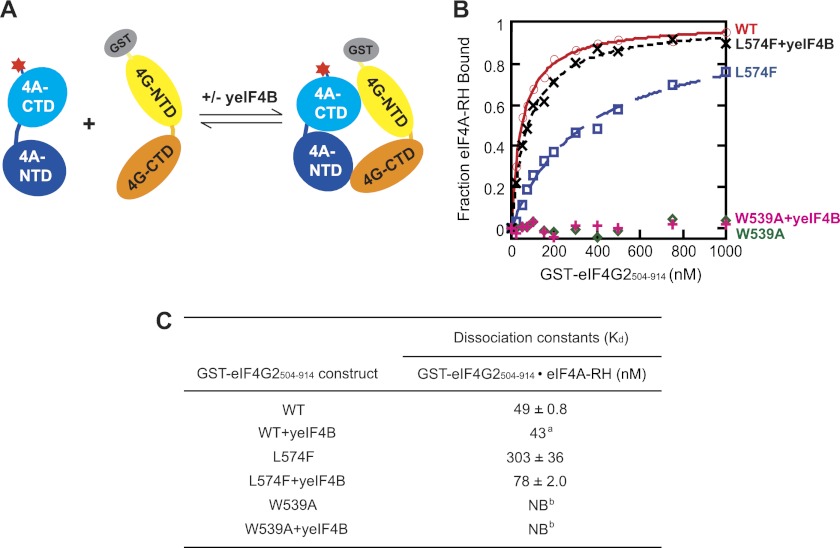

yeIF4B Can Partially Restore eIF4A Association with the L574F Variant of the eIF4G2-CTD in Vitro

We sought next to determine whether the ability of overexpressed yeIF4B to rescue eIF4A·eIF4G2-L574F complexes in vivo could be reconstituted in vitro with purified components. To this end, we conducted in vitro binding assays with a GST fusion to eIF4G2 C-terminal residues 504–914 (encompassing the HEAT domain) and eIF4A-RH, purified as recombinant proteins from Escherichia coli. The binding affinity of eIF4A for the WT or mutant eIF4G2 proteins was determined by measuring the increase in fluorescence anisotropy of eIF4A-RH upon titrating the unlabeled GST-eIF4G2(504–914) protein in the presence or absence of excess WT yeIF4B (Fig. 5A). In the absence of yeIF4B, eIF4A-RH bound to WT GST-eIF4G2(504–914) with a Kd of ∼50 nm, within the range reported previously for yeast eIF4A interaction with eIF4G1 (10, 30). As expected, the affinity of eIF4A-RH for the L574F variant was significantly reduced, displaying a ∼7-fold higher Kd for the complex formed with GST-eIF4G2(504–914)-L574F (Fig. 5, B and C). Importantly, when the same reaction was conducted in the presence of 1 μm yeIF4B, the Kd for the complex formed with the L574F variant decreased by a factor of ∼4, reaching a value within a factor of ∼2 of the Kd for the WT complex (Fig. 5, B and C). Thus, yeIF4B can partially rescue complex formation between eIF4A and the L574F variant of the eIF4G2 HEAT domain in vitro.

FIGURE 5.

yeIF4B selectively enhances stability of the eIF4A complex formed with the HEAT domain of eIF4G2-L574F in vitro. A, schematic representation of the fluorescence anisotropy assay to monitor binding of eIF4A labeled with tetramethylrhodamine (red star) and GST fusions to residues 504–914 of different eIF4G2 proteins in the presence or absence of yeIF4B. B, eIF4A-RH (30 nm) was incubated with increasing amounts of the indicated GST-eIF4G2(504–914) proteins in the presence or absence of 1 μm yeIF4B, and the change in fluorescence anisotropy of eIF4A-RH was measured for each concentration of GST-eIF4G2(504–914). Each point is the average of several independent experiments. Kd values calculated from the data are listed in C. C, Kd values calculated from 3–6 independent experiments conducted as in B with S.E. a, average of two independent experiments; b, no binding detected.

We showed above that the growth defect conferred by the W539A substitution in eIF4G2 cannot be suppressed by yeIF4B overexpression (Fig. 3A). Consistent with this, the W539A variant of GST-eIF4G2(504–914) showed no detectable binding to eIF4A-RH either in the absence or presence of 1 μm yeIF4B (Fig. 5, B and C). Hence, our in vitro binding assays recapitulate the ability of increased concentrations of yeIF4B to rescue selectively eIF4A interaction with the L574F, but not the W539A, variant of eIF4G2. In separate experiments, we found that 1 μm yeIF4B does not significantly reduce the Kd for the complex formed between eIF4A-RH and wild-type GST-eIF4G2(504–914) (Fig. 5C), underscoring the specificity of the effect of yeIF4B on eIF4A binding to the L574F variant. These results are consistent with our conclusion that yeIF4B does not simply bridge the interaction between eIF4A and eIF4G, because in this scenario it might be expected that yeIF4B would reduce the Kd for the complex between eIF4A and WT GST-eIF4G2(504–914) and also confer at least partial rescue of eIF4A interaction with the W539A variant.

Evidence that yeIF4B Promotes Association between eIF4A and WT eIF4G in Vivo

As noted above, interaction between eIF4G and eIF4A at native expression levels in yeast cell extracts had not been detected previously (9, 35), and only a small amount of eIF4G1·eIF4A complex was observed when eIF4A was overexpressed from a strong (GAL) promoter (10). It was speculated that the eIF4G-eIF4A interaction in yeast cells is transient and might depend on interaction of eIF4G with another factor that exposes the eIF4A binding site in the HEAT domain (10). In view of our finding that overexpressing yeIF4B rescues eIF4A interaction with certain eIF4G HEAT domain mutants, we explored whether yeIF4B has a role in promoting eIF4A interaction with WT eIF4G in vivo. Supporting this hypothesis, we found that overexpressing yeIF4B produces a significant ∼2.5-fold increase in the amount of eIF4A coimmunoprecipitating with WT eIF4G2 (Fig. 6, A and B). Moreover, deletion of TIF3 reduces the coimmunoprecipitation of eIF4A with eIF4G2 by a factor of ∼4 (Fig. 6, C and D). Overexpressing or eliminating yeIF4B had little or no effect on the amounts of eIF4A in the WCEs; nor did it affect the amounts of eIF4E that coimmunoprecipitated with eIF4G2 (Fig. 6, A and C). These results suggest that yeIF4B promotes complex formation between eIF4A and wild-type eIF4G2 in vivo. Below we propose an explanation for the ability of yeIF4B to increase the amount of eIF4A associated with WT eIF4G2 in WCEs (Fig. 6, A and B) but not in reactions with purified proteins (Fig. 5C).

We envisioned that the stimulatory effect of yeIF4B on eIF4G·eIF4A complex formation would enhance the recruitment of eIF4A to eIF4F complexes bound to capped 5′-ends of mRNA and that this would represent one aspect of the stimulatory effect of yeIF4B on translation initiation in vivo. If so, then overexpressing eIF4A, which is sufficient to enhance native eIF4G·eIF4A assembly (e.g. Fig. 4B, lanes 24 and 25 versus lane 27, αeIF4A), should mitigate the growth defect of tif3Δ cells. Consistent with this prediction, we found that overexpressing eIF4A improved the growth at 18 °C of tif3Δ cells but did not affect the growth of WT TIF3 cells (Fig. 6E). We verified that eIF4A was overexpressed in the tif3Δ transformants harboring hc TIF1 (Fig. 6F). It is important to note, however, that tif3Δ cells overexpressing eIF4A still grow much more slowly than isogenic WT TIF3 cells (Fig. 6E), indicating that yeIF4B has other critical functions in translation beyond stabilization of eIF4A·eIF4G complexes.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we demonstrated that various point mutations in the HEAT domains of eIF4G1 and eIF4G2 that weaken the binding to eIF4A and hence are suppressed in vivo by overexpressing eIF4A also are suppressed by overexpressing yeIF4B. Although suppression of Ts− phenotypes of eIF4G HEAT mutations by eIF4A overexpression was reported previously for other eIF4G mutations (9), comparable suppression by yeIF4B overexpression is a novel finding of this study. In addition, we succeeded in establishing conditions for assaying the abundance of native eIF4A·eIF4G complexes in cell extracts and determined that these interactions are resistant to RNase treatment and, thus, persist without having these factors tethered to the same mRNA molecules. We are unsure why we have succeeded in specific coimmunoprecipitation of native eIF4A and eIF4G proteins where previous attempts have failed, but it might be attributable to using highly concentrated WCEs and omitting detergents from the wash buffers. In any event, using this assay, we demonstrated a robust correlation between suppression of the Ts− phenotypes of particular eIF4G mutations and restoration of a WT level (or even greater) of eIF4A association with eIF4G in WCEs of cells overexpressing yeIF4B. This correlation strongly suggests that an excess of yeIF4B reduces the growth defects conferred by eIF4G HEAT domain mutations by rescuing eIF4A·eIF4G assembly in vivo. We extended this correlation with the results of in vitro experiments on purified proteins, demonstrating that whereas both L574F and W539A substitutions in eIF4G2 reduce its affinity for eIF4A, detectable interaction with eIF4A was enhanced by an elevated concentration of yeIF4B only for the L574F variant. These last findings are in accordance with the fact that the Ts− phenotype and defective interaction with eIF4A conferred by L574F, but not that of W539A, are suppressed by yeIF4B overexpression in vivo. The eIF4G1 residue corresponding to Trp-539 (Trp-579) lies in a segment outside of the HEAT domain that interacts with the eIF4A-CTD (Fig. 2). Together, the results demonstrate that high concentrations of yeIF4B can mitigate the deleterious effects of HEAT domain mutations on the stability of native eIF4G·eIF4A complexes and the attendant defects in translation initiation produced by these mutations in vivo.

The ability of yeIF4B to restore eIF4A association with the eIF4G2-L574F mutant in vitro using purified proteins suggests that yeIF4B can interact directly with eIF4G, eIF4A, or both proteins in a manner that restores eIF4G·eIF4A association. The possibility of direct interaction of yeIF4B with eIF4G is supported by our ability to detect coimmunoprecipitation of yeIF4B but not eIF4A with eIF4G2-M570K (expressed from a single-copy allele) and eIF4G2-W539A upon yeIF4B overexpression (e.g. see Fig. 4D, lane 10). Because these eIF4G·yeIF4B complexes are resistant to an RNase treatment sufficient to significantly reduce association of PABP with eIF4G, the eIF4G·yeIF4B interaction detected in these assays is not likely to be bridged by mRNA or PABP. In addition, we showed previously that immune complexes prepared under these conditions are devoid of detectable eIF3 or 40S subunits (39). Although we cannot rule out the possibility that another factor mediates or stabilizes the interaction between eIF4G and eIF4B observed in these immune complexes, our data are significant in providing the first evidence that yeIF4B is physically associated with eIF4G in native complexes that do not contain eIF4A, intact mRNA, or 43S PICs. As noted above, stimulation of eIF4A helicase activity by yeIF4B has not been demonstrated in vitro, and although genetic data are consistent with a role for yeIF4B in promoting eIF4F function, it has been unclear whether yeIF4B acts in close cooperation with eIF4F or, rather, by a parallel mechanism. Our findings of mRNA-independent eIF4G·yeIF4B association in cell extracts suggest that yeIF4B stimulates eIF4F function in a manner involving direct contact between these two factors.

In addition to rescuing eIF4A association with certain eIF4G mutants, we observed that yeIF4B also promotes native complex formation between eIF4A and wild-type eIF4G2. Thus, overexpressing yeIF4B increased co-IP of eIF4A with WT eIF4G2, whereas the absence of yeIF4B in tif3Δ cells markedly reduced detectable eIF4G2·eIF4A complexes. These findings suggest that at least one function of yeIF4B in vivo is to stimulate interaction of eIF4A with the HEAT domain of eIF4G, which is crucial for achieving the active conformation of eIF4A (5, 13, 14). Enhancing eIF4G·eIF4A association should also facilitate recruitment of eIF4A to eIF4F complexes at the 5′-ends of mRNAs, where eIF4A helicase function can produce a single-stranded RNA binding site for the 43S PIC. Our finding that eIF4A overexpression confers an appreciable, if modest, improvement of the growth of tif3Δ cells is consistent with the idea that stimulating eIF4A·eIF4F assembly is one aspect of yeIF4B function in vivo, although the substantial growth defect remaining in these cells clearly indicates that yeIF4B has other important functions in the initiation pathway. Our model also helps to explain previous findings of Linder and co-workers (29) that the Ts− phenotype conferred by the A79V substitution in eIF4A is very efficiently suppressed by overexpressing yeIF4B. We envision that because the defect in eIF4A helicase activity is rate-limiting for translation in the A79V mutant, the ability of overexpressed yeIF4B to enhance eIF4A·eIF4G assembly provides a strong improvement of mutant cell growth.

How does yeIF4B overexpression promote association of eIF4A with HEAT mutants of eIF4G? Our findings that yeIF4B can be coimmunoprecipitated with all of the eIF4G mutants we tested but rescues eIF4A association only for the HEAT domain mutants seems inconsistent with the possibility that yeIF4B merely bridges the eIF4G·eIF4A complex by binding simultaneously to both eIF4G and eIF4A. We cannot rule out the possibility that the W579A and W539A substitutions mapping outside of the HEAT domains of eIF4G1/eIF4G2 cannot be rescued by excess yeIF4B simply because they confer a stronger eIF4A binding defect than do the HEAT domain substitutions. However, this possibility seems less likely if one considers that the growth defects of the eIF4G1-W579A and eIF4G2-W539A mutants are less severe than those of eIF4G2-T578I and eIF4G1-R835A/F838A, whose association with eIF4A is rescued by excess yeIF4B. It is noteworthy that Nielsen et al. (19) found that interactions of mammalian eIF4A with eIF4G and eIF4B (in the presence of ssRNA) are mutually exclusive, precluding formation of a trimeric complex. Consistent with this, we showed here that yeIF4B does not reduce the Kd for the eIF4G·eIF4A complex formed with WT GST-eIF4G2(504–914), which might have been expected upon formation of a trimeric complex. Furthermore, whereas we have been able to detect the GST-eIF4G2(504–914)·eIF4A complex by native gel electrophoresis in vitro, the presence of yeIF4B at high concentrations did not alter the mobility of this binary complex, providing no evidence for the trimeric complex (data not shown). Finally, although overexpressing yeIF4B enhances complex formation between eIF4A and eIF4G in vivo, overexpressing eIF4A does not increase the abundance of eIF4B·eIF4G complexes (e.g. Fig. 4B, lanes 24–26). These findings do not support a model in which eIF4A binds more tightly to a yeIF4B·eIF4G subcomplex within a trimeric complex than it binds to eIF4G alone in eIF4A·eIF4G binary complexes.

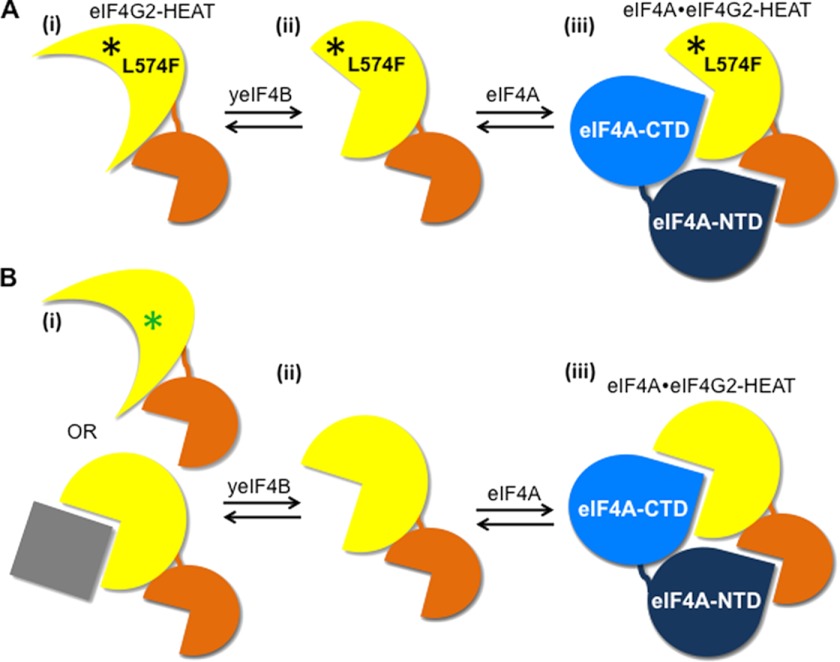

Thus, in the absence of physical evidence for a yeIF4B·eIF4G·eIF4A trimeric complex, we propose instead that interaction of yeIF4B with the L574F or L614F mutant corrects the deleterious effects of these substitutions on the orientation of helix α1 or α3 in the HEAT domain, both of which harbor multiple points of contact with eIF4A, and thereby restores a conformation competent for binding eIF4A (Fig. 7). Dissociation of yeIF4B from the eIF4G HEAT domain would precede complex formation between eIF4G and eIF4A, such that a trimeric complex does not accumulate. In this view, interaction of yeIF4B with the eIF4G HEAT domain is transient and operates in a manner akin to a chaperone-substrate interaction. The lack of suppression of the single-copy M570K allele by yeIF4B overexpression probably reflects the combined effect of its relatively lower abundance and a greater disruption of HEAT domain structure by insertion of positively charged Lys deep into the space between helices α1 and α3 (Fig. 2), which also renders the protein more susceptible to proteolysis compared with the L574F variant.

FIGURE 7.

Hypothetical model for the ability of overexpressed yeIF4B to rescue eIF4A association with eIF4G2 HEAT domain mutants and promote assembly of WT eIF4G·eIF4A complexes in vivo. The HEAT domain of WT (B) or L574F mutant (A) eIF4G2 is depicted using yellow and orange shapes to represent helices 1–5 and 6–10, respectively, connected by a linker. The RecA-like domains of eIF4A are depicted using light and dark blue shapes that can be inserted into the pockets formed by the HEAT domain helices, as observed in the x-ray crystal structure of the eIF4G1·eIF4A complex described in the legend to Fig. 2. A, the L574F substitution in eIF4G2 distorts the packing of HEAT domain helices 1–3 in a manner that weakens their direct contacts with the eIF4A-CTD (i). Transient interaction of the mutant HEAT domain with yeIF4B in cells overexpressing the latter overcomes the moderate distortions conferred by L574F (ii) to achieve a conformation competent for stable complex formation with eIF4A (iii). B, In the case of WT eIF4G2, a hypothetical post-translational modification (green asterisk) or interacting protein (gray box) provokes a distortion of the WT HEAT domain in yeast cells, which might resemble that produced by the L574F substitution (i), and transient interaction with yeIF4B overcomes the putative modifications of the WT HEAT domain (ii) to stabilize the conformation conducive to stable complex formation with eIF4A (iii).

The Ts− phenotypes of the eIF4G2-T578I and eIF4G1-R835A/F838A mutants were diminished by yeIF4B overexpression but less efficiently than by overexpressing eIF4A. Because these substitutions eliminate specific contacts at the eIF4A/eIF4G interface, their binding defects should be less responsive to yeIF4B overexpression if (as we postulate) yeIF4B acts primarily to promote the proper conformation of HEAT domain helices conducive to eIF4A binding. Indeed, it appeared from the co-IP analysis that yeIF4B overexpression was relatively less effective at enhancing eIF4A·eIF4G association for the T578I and R835A/F838A substitutions compared with the highly suppressible L574F and L614F substitutions. Finally, we propose that the Ts− phenotypes and eIF4A binding defects produced by eIF4G2-W539A and eIF4G1-W579A are insensitive to excess yeIF4B primarily because these residues lie outside of the HEAT domain.

It should be noted that excess yeIF4B did not fully suppress the Ts− phenotypes of the T578I and R835A/F838A mutants although the amounts of eIF4A associated with these variants upon yeIF4B overexpression were equal to or greater than that observed for WT eIF4G at native levels of factor expression (e.g. Fig. 3E, compare lanes 9 and 12, αeIF4A). Accordingly, we conclude that the loss of direct contacts with eIF4A conferred by these eIF4G substitutions not only weakens the eIF4A·eIF4G complex but also impairs eIF4G function in modulating the conformation of eIF4A to promote the binding of substrates, ATP hydrolysis, or release of products and that the latter defect(s) persists even when eIF4A·eIF4G assembly is restored by overexpressing yeIF4B or eIF4A.

Our model in which yeIF4B promotes the productive conformation of the eIF4G HEAT domain is supported by our finding that overexpressing yeIF4B elevates native complexes formed between eIF4A and WT eIF4G, but can the model be reconciled with our ostensibly contradictory findings that yeIF4B has no effect on the stability (Kd) of the complex between eIF4A and the WT eIF4G2 HEAT domain in vitro? One explanation would be that the recombinant WT eIF4G2 HEAT domain expressed in bacteria spontaneously assumes a conformation conducive for eIF4A binding without prior interaction with yeIF4B, and because a trimeric complex cannot form, excess yeIF4B has no impact on the stability of the eIF4A·GST-eIF4G2(504–914) complex in vitro. In yeast cells, by contrast, a post-translational modification or interaction with an inhibitory factor would provoke an altered state or conformation of the HEAT domain incompatible with stable eIF4A binding, possibly mimicking the effects of the L574F and L614F substitutions. Transient interaction with yeIF4B would overcome these effects and stabilize the HEAT domain conformation conducive for eIF4A binding (Fig. 7), and overexpressing yeIF4B would increase the proportion of eIF4G present in the favorable conformation to drive assembly of eIF4G·eIF4A binary complexes to abnormally high levels. Because the hypothetical post-translational modification or inhibitory factor would be missing from the in vitro analysis, we would not observe a stimulatory effect of yeIF4B on eIF4A binding to the WT HEAT domain in these experiments. This model can also explain the fact that overexpressing eIF4A does not increase the amount of yeIF4B that coimmunoprecipitates with eIF4G (although the reverse is true), because yeIF4B would interact transiently with eIF4G and could not form stable trimeric complexes with eIF4A and eIF4G in vivo (19).

An attractive feature of this hypothesis is that it also resolves the longstanding paradox that native eIF4G·eIF4A complexes have been difficult to recover in cell extracts although the recombinant factors display a relatively strong interaction in vitro (Kd of ∼50 nm; our observations and see Refs. 10 and 30). Indeed, failing to detect eIF4G·eIF4A complexes at normal expression levels, Trachsel and co-workers (10) previously suggested that the eIF4G·eIF4A interaction might be impeded in vivo by a post-translational modification or unknown regulatory factor and that interaction with another stimulatory factor would transiently expose the eIF4A binding site in eIF4G. Our results suggest that yeIF4B performs this predicted stimulatory function in vivo.

In conclusion, by uncovering a class of eIF4G HEAT domain mutations whose Ts− phenotypes are suppressed by yeIF4B overexpression and by elucidating the molecular mechanism of suppression, we detected a novel interaction between eIF4G and yeIF4B and revealed an unforeseen function for yeIF4B in promoting complex formation between eIF4G and eIF4A in vivo. This activity of yeIF4B should facilitate the known roles of eIF4G in stimulating eIF4A helicase activity and (in conjunction with eIF4E) of recruiting eIF4A to the capped 5′-ends of mRNA. Our results also suggest that yeIF4B is capable of reversing an inhibitory mechanism that appears to operate in WT yeast cells to limit association of eIF4A with the eIF4G·eIF4E subcomplex of eIF4F. It will be interesting to determine whether this novel function of yeIF4B is enlisted to regulate eIF4F assembly under specific physiological conditions.

Acknowledgments

We thank Byung-Sik Shin and Tom Dever for suggestions and excellent technical advice, and we are very grateful to Michael Altmann, Patrick Linder, Maury Swanson, John McCarthy, Tien-Hsien Chang, and Jon Warner for kind gifts of antibodies or plasmids.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by the National Institutes of Health Intramural Research Program and National Institutes of Health Grant GM62128 (to J. R. L.). This work was also supported by an American Heart Association award (to S. E. W.).

This article contains supplemental Fig. S1.

- PIC

- preinitiation complex

- PABP

- poly(A)-binding protein

- FOA

- fluoroorotic acid

- WCE

- whole cell extract

- hc

- high copy

- IP

- immunoprecipitation

- WB

- Western blot

- eIF4A-RH

- tetramethylrhodamine-labeled eIF4A

- yeIF4B

- yeast eIF4B

- mRNP

- messenger ribonucleoprotein.

REFERENCES

- 1. Pestova T. V., Lorsch J. R., Hellen C. U. T. (2007) The mechanism of translation initiation in eukaryotes. in Translational Control in Biology and Medicine (Mathews M., Sonenberg N., Hershey J. W. B., eds) pp. 87–128, Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hinnebusch A. G. (2011) Molecular mechanism of scanning and start codon selection in eukaryotes. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 75, 434–467, first page of table of contents [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Parsyan A., Svitkin Y., Shahbazian D., Gkogkas C., Lasko P., Merrick W. C., Sonenberg N. (2011) mRNA helicases. The tacticians of translational control. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 12, 235–245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Rogers G. W., Jr., Komar A. A., Merrick W. C. (2002) eIF4A. The godfather of the DEAD box helicases. Prog. Nucleic Acid. Res. Mol. Biol. 72, 307–331 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Schütz P., Bumann M., Oberholzer A. E., Bieniossek C., Trachsel H., Altmann M., Baumann U. (2008) Crystal structure of the yeast eIF4A-eIF4G complex. An RNA-helicase controlled by protein-protein interactions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 9564–9569 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Rajagopal V., Park E. H., Hinnebusch A. G., Lorsch J. R. (2012) Specific domains in yeast translation initiation factor eIF4G strongly bias RNA unwinding activity of the eIF4F complex toward duplexes with 5′-overhangs. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 20301–20312 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Pause A., Méthot N., Svitkin Y., Merrick W. C., Sonenberg N. (1994) Dominant negative mutants of mammalian translation initiation factor eIF-4A define a critical role for eIF-4F in cap-dependent and cap-independent initiation of translation. EMBO J. 13, 1205–1215 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Imataka H., Sonenberg N. (1997) Human eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4G (eIF4G) possesses two separate and independent binding sites for eIF4A. Mol. Cell. Biol. 17, 6940–6947 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Neff C. L., Sachs A. B. (1999) Eukaryotic translation initiation factors 4G and 4A from Saccharomyces cerevisiae interact physically and functionally. Mol. Cell. Biol. 19, 5557–5564 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Dominguez D., Altmann M., Benz J., Baumann U., Trachsel H. (1999) Interaction of translation initiation factor eIF4G with eIF4A in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 26720–26726 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Dominguez D., Kislig E., Altmann M., Trachsel H. (2001) Structural and functional similarities between the central eukaryotic initiation factor (eIF)4A-binding domain of mammalian eIF4G and the eIF4A-binding domain of yeast eIF4G. Biochem. J. 355, 223–230 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Marcotrigiano J., Lomakin I. B., Sonenberg N., Pestova T. V., Hellen C. U., Burley S. K. (2001) A conserved HEAT domain within eIF4G directs assembly of the translation initiation machinery. Mol. Cell 7, 193–203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Oberer M., Marintchev A., Wagner G. (2005) Structural basis for the enhancement of eIF4A helicase activity by eIF4G. Genes Dev. 19, 2212–2223 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hilbert M., Kebbel F., Gubaev A., Klostermeier D. (2011) eIF4G stimulates the activity of the DEAD box protein eIF4A by a conformational guidance mechanism. Nucleic Acids Res. 39, 2260–2270 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Méthot N., Pause A., Hershey J. W., Sonenberg N. (1994) The translation initiation factor eIF-4B contains an RNA-binding region that is distinct and independent from its ribonucleoprotein consensus sequence. Mol. Cell Biol. 14, 2307–2316 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Naranda T., Strong W. B., Menaya J., Fabbri B. J., Hershey J. W. (1994) Two structural domains of initiation factor eIF-4B are involved in binding to RNA. J. Biol. Chem. 269, 14465–14472 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Rozovsky N., Butterworth A. C., Moore M. J. (2008) Interactions between eIF4AI and its accessory factors eIF4B and eIF4H. RNA 14, 2136–2148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Marintchev A., Edmonds K. A., Marintcheva B., Hendrickson E., Oberer M., Suzuki C., Herdy B., Sonenberg N., Wagner G. (2009) Topology and regulation of the human eIF4A/4G/4H helicase complex in translation initiation. Cell 136, 447–460 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Nielsen K. H., Behrens M. A., He Y., Oliveira C. L., Jensen L. S., Hoffmann S. V., Pedersen J. S., Andersen G. R. (2011) Synergistic activation of eIF4A by eIF4B and eIF4G. Nucleic Acids Res. 39, 2678–2689 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Özeş A. R., Feoktistova K., Avanzino B. C., Fraser C. S. (2011) Duplex unwinding and ATPase activities of the DEAD-box helicase eIF4A are coupled by eIF4G and eIF4B. J. Mol. Biol. 412, 674–687 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Methot N., Pickett G., Keene J. D., Sonenberg N. (1996) In vitro RNA selection identifies RNA ligands that specifically bind to eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4B. The role of the RNA remotif. RNA 2, 38–50 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Méthot N., Song M. S., Sonenberg N. (1996) A region rich in aspartic acid, arginine, tyrosine, and glycine (DRYG) mediates eukaryotic initiation factor 4B (eIF4B) self-association and interaction with eIF3. Mol. Cell Biol. 16, 5328–5334 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Spirin A. S. (2009) How does a scanning ribosomal particle move along the 5′-untranslated region of eukaryotic mRNA? Brownian Ratchet model. Biochemistry 48, 10688–1069219835415 [Google Scholar]

- 24. Goyer C., Altmann M., Lee H. S., Blanc A., Deshmukh M., Woolford J. L., Jr., Trachsel H., Sonenberg N. (1993) TIF4631 and TIF4632. Two yeast genes encoding the high-molecular-weight subunits of the cap-binding protein complex (eukaryotic initiation factor 4F) contain an RNA recognition motif-like sequence and carry out an essential function. Mol. Cell Biol. 13, 4860–4874 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Clarkson B. K., Gilbert W. V., Doudna J. A. (2010) Functional overlap between eIF4G isoforms in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. PLoS One 5, e9114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Tarun S. Z., Jr., Wells S. E., Deardorff J. A., Sachs A. B. (1997) Translation initiation factor eIF4G mediates in vitro poly(A) tail-dependent translation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 94, 9046–9051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Blum S., Schmid S. R., Pause A., Buser P., Linder P., Sonenberg N., Trachsel H. (1992) ATP hydrolysis by initiation factor 4A is required for translation initiation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 89, 7664–7668 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]