Background: Phosphorylation of Arp2 increases nucleating activity of the Arp2/3 complex, but its role in complex cell processes remains undetermined.

Results: A mutant Arp2 that cannot be phosphorylated delays Dictyostelium development and impairs chemotaxis toward cAMP independently of development.

Conclusion: Disrupting Arp2 phosphorylation reveals an unexpected role for Arp2/3 complex in development.

Significance: Phosphorylation of the Arp2/3 complex is emerging as a previously unrecognized regulatory mechanism.

Keywords: Actin, Cell Migration, Cell Polarity, Chemotaxis, Dictyostelium, Arp2/3 Complex

Abstract

Phosphorylation of the actin-related protein 2 (Arp2) subunit of the Arp2/3 complex on evolutionarily conserved threonine and tyrosine residues was recently identified and shown to be necessary for nucleating activity of the Arp2/3 complex and membrane protrusion of Drosophila cells. Here we use the Dictyostelium diploid system to replace the essential Arp2 protein with mutants that cannot be phosphorylated at Thr-235/6 and Tyr-200. We found that aggregation of the resulting mutant cells after starvation was substantially slowed with delayed early developmental gene expression and that chemotaxis toward a cAMP gradient was defective with loss of polarity and attenuated F-actin assembly. Chemotaxis toward cAMP was also diminished with reduced cell speed and directionality and shorter pseudopod lifetime when Arp2 phosphorylation mutant cells were allowed to develop longer to a responsive state similar to that of wild-type cells. However, clathrin-mediated endocytosis and chemotaxis under agar to folate in vegetative cells were only subtly affected in Arp2 phosphorylation mutants. Thus, phosphorylation of threonine and tyrosine is important for a subset of the functions of the Arp2/3 complex, in particular an unexpected major role in regulating development.

Introduction

The Arp2/33 complex, a seven-subunit protein complex that includes actin-related proteins Arp2 and Arp3 and five accessory proteins, is a key generator of actin filament (F-actin) networks in most eukaryotic cells. F-actin networks assembled by the Arp2/3 complex drive membrane dynamics at the leading edge of migrating cells, at endocytic cups, and at moving endosomes (1). The complex generates F-actin networks by binding to the side of existing actin “mother” filaments and nucleating new branched “daughter” filaments (2, 3). Consistent with a role of Arp2/3 complex in driving actin-dependent cell processes, dysregulation of the complex is associated with diseases such as immune cell disorders and cancer metastasis (4).

The coupling of signaling networks and extracellular cues to activation of the Arp2/3 complex and actin polymerization has been well studied. The complex is activated by binding to a mother filament (5) and by binding of nucleation-promoting factors (NPFs) that include members of the Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome protein (WASP) and SCAR/WASP and Verprolin homologous protein (WAVE) families, which are activated by the Rho family GTPases Cdc42 and Rac (1). A current view is that binding of a mother filament, an activated NPF, and ATP induces conformational changes in the orientation of subunits in the Arp2/3 complex whereby realignment of the Arp2 and Arp3 subunits mimics the short pitch of an actin dimer (6, 7) to facilitate rapid F-actin assembly. However, we recently showed that NPF binding is not sufficient for activating the complex and that phosphorylation of the Arp2 subunit at either Thr-237/238 or Tyr-202 (human sequence) is also necessary (8). We further showed that phosphorylation of Arp2 induces a reorientation of Arp2 relative to Arp3 by destabilizing a network of salt bridge interactions at the interface of the Arp2, Arp3, and ARPC4 subunits (9). These findings suggest a new view of how the complex is regulated and indicate that it is a coincidence detector requiring both NPF binding and phosphorylation of Arp2 for activation in response to extracellular cues.

The Arp2 phosphorylation sites are conserved from yeasts to mammals. The importance of these sites for NPF-induced F-actin assembly was confirmed biochemically using purified Arp2/3 complex from Acanthamoeba castellani and bovine brain (8) and recombinant wild-type and phosphorylation mutant human Arp2/3 complex (9). Their significance for membrane protrusion was also confirmed using wild-type and mutant Arp2 in Drosophila S2 cells (8). However, their functional significance for a complex cell behavior like directional migration has not been reported. In the current study, we asked whether the identified Arp2 phosphorylation is necessary for chemotaxis of Dictyostelium cells. Dictyostelium is a useful and well established model system to study regulated actin cytoskeleton dynamics. As in other organisms, the Arp2/3 complex in Dictyostelium is required for F-actin assembly in processes such as macropinocytosis, phagocytosis, and chemotaxis (10). The Arp2 gene is essential for Dictyostelium growth (11), and altering the Arp2 subunit by adding a GFP tag impairs chemoattractant-induced actin polymerization (12), confirming that the Arp2/3 complex serves as a major actin nucleator in Dictyostelium as in other organisms. We found that cells expressing a mutant Arp2 with alanine substitutions for Thr-235/236 and a phenylalanine substitution for Tyr-200 developed poorly and chemotaxed to cAMP inefficiently, including being less polarized and having decreased speed of movement. However, when undeveloped cells were constrained by a layer of agarose, these defects were broadly reversed, demonstrating that the mutant Arp2 retains some wild-type protein functions. Our findings reveal different regulatory mechanisms for Arp2/3 complex activity for distinct cell behaviors.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Generation of Arp2 Mutant Constructs

The Dictyostelium Arp2 residues that are orthologous to the sites of phosphorylation in A. castellani Arp2 and conserved throughout eukaryotes are Tyr-200, Thr-235, and Thr-236. We used PCR-based site-specific mutagenesis to alter the encoded amino acids to non-phosphorylatable residues as follows: T235A/T236A double mutant was created, and Y200F was then created in this to give the triple non-phosphorylatable mutant. These mutant alleles as well as a wild-type allele also encoded an amino-terminal Myc epitope for confirmation of their expression by Western blot.

The PCR primers used are detailed in supplemental Table S1. For the mutant alleles, after making the two separate 5′ and 3′ regions by PCR, they were used as dual templates to make the full-length construct by fusion PCR using primers DdArp2-Myc-fwd and DdArp2-Not1-rev. Full-length products were cloned into pCR-Blunt-TOPO (Invitrogen) and sequenced. Inserts were removed using BamHI-NotI and inserted into the backbone of the extrachromosomal vector pRHI76 that had been cut with BglII-NotI. The resulting plasmids containing the myc-arpB alleles were named pJSK19 (WT), pMZ106 (T235A/T236A), and pMZ107 (Y200F/T235A/T236A).

Parasexual Replacement of Endogenous arp2 with myc-arp2 Alleles

The diploid strain DJK45, which contains one WT copy of arpB and one copy disrupted by insertion of the blasticidin S resistance gene, was used as the parental strain. Plasmids pJSK19, pMZ106, and pMZ107 were individually transformed into DJK45 by electroporation using a BTX ECM399 electroporation system (Harvard Apparatus) set to 380 V. Transformants were grown in plastic dishes in HL5 medium with G418 (10 μg/ml) until clones could be seen. These were harvested by dislodging with a pipette, and cells were then mixed with 0.2 ml culture of Klebsiella aerogenes and plated onto SM agar plates containing 2 μg/ml thiabendazole. Individual clones appearing on these plates were repicked into axenic medium containing G418 and blasticidin (10 μg/ml), and the thymidine/uracil auxotrophy of the cells was tested (diploids that came through the procedure were non-auxotrophic; haploid strains all turned out to be auxotrophic for thymidine as noted previously (11)). The Myc-Arp2 replacement strains were named Arp2WTR (WT), Arp2T>A (T235A/T236A), and Arp2TY>AF (Y200F/T235A/T236A). Western blots for Arp2 and Myc were performed as described previously (11).

cAMP Chemotaxis (Micropipette Assay and Under-agarose Assay)

For starvation, cells were harvested and washed with 20 mm phosphate buffer, pH 6.5 twice and resuspended at a density of 1 × 107 cells/ml in the phosphate buffer. To induce cAMP signaling, cells were pulsed with 30–60 nm cAMP every 6 min for 5 h. In some cases, cells were pulsed for 8 h. For the micropipette assay, developed cells were placed on the plate, and their migration toward cAMP delivered by a micropipette was recorded every 6 s for 30 min. Tracking of cell migration was done using the MultiTracker and Chemotaxis tool plugins for ImageJ, and statistics were analyzed using Prism software. For the cAMP under-agarose assay, pulsed cells were diluted to 2 × 105 cells/ml in phosphate buffer, pipetted up and down to disaggregate any clumped cells, and placed in a well cut into a dish of 0.6% agarose containing 50 nm cAMP. Only cells competent to leave the well and migrate under the agarose can be studied in this assay. Cells were imaged with a 60× 1.4 numeric aperture oil lens using differential interference contrast microscopy on a Nikon TE2000 microscope. Frames were captured every 2 s using a Q Imaging Retiga EXi Fast 1394 camera and Micromanager software. To determine pseudopod extension speed, a line was drawn through the extending pseudopod in ImageJ, the image stack was resliced to generate a kymograph, and the slope of this was measured.

In Vivo Actin Polymerization

Actin polymerization stimulated by exogenous 2 μm cAMP was determined by measuring fluorescence of F-actin labeled with rhodamine-phalloidin as described previously (13). The fluorescence intensity of rhodamine-phalloidin was measured using a SpectraMax M5 plate reader (GE Healthcare).

Development

To determine developmental phenotypes, cells were harvested and washed twice with 20 mm phosphate buffer, pH 6.5 and seeded on phosphate-buffered agar plates, and images of developing cells were taken at 0, 6, and 16 h. To test stream formation under buffer condition, the harvested cells were seeded at a density of 1 × 106 cells/cm2 in 6-well dishes containing 20 mm phosphate buffer, and the developmental phenotypes were recorded every 15 min for 12 h using an Axiovert S-100 microscope (Carl Zeiss).

Immunoblotting

Cell lysate preparation and immunoblotting were performed as described previously (13). After starvation, cells were obtained at the indicated time of development. Blots were probed with anti-cAMP receptor 1 (cAR1) and anti-adenylyl cyclase A (ACA) antibodies, and signal was detected with enhanced chemiluminescence (Pierce). Rabbit anti-cAR1 and anti-ACA antibodies were generous gifts from P. Devreotes, Johns Hopkins University.

Detection of Arp2 Phosphorylation

Dictyostelium SCAR-VCA domain (amino acids 369–443) was used to affinity enrich the Arp2/3 complex. The SCAR-VCA cDNA fragment was amplified using primers 5′-ggatccggtggaggtgcctctga-3′ and 5′-ctcgagttaatcccaatcagaatca-3′ by PCR and cloned in-frame into a BamHI/XhoI site of pGEX6P-2 vector. GST-fused SCAR-VCA was expressed in Escherichia coli BL21 cells and purified with glutathione-Sepharose beads (Pierce). The Arp2/3 complex from cell lysates of vegetative and 5-h-starved Arp2WTR cells was purified using affinity chromatography with GST-SCAR-VCA immobilized beads. Affinity complexes were untreated or treated with YOP tyrosine phosphatase and λ-phosphatase (New England Biolabs) and separated by SDS-PAGE. Phosphorylation and Myc-tagged Arp2 subunit were detected by immunoblotting with anti-phosphotyrosine (Millipore), anti-phosphothreonine (Cell Signaling Technology), and anti-Myc antibodies.

Folate Chemotaxis

Vegetatively growing cells were harvested from HL5 dishes and transferred to a well cut into a dish of 0.5× SM agar. 0.5 mg/ml folic acid was placed into a parallel well cut 1.5 cm away. Cells exiting the well and chemotaxing underneath the agar were filmed either at high magnification and frame rate (60× differential interference contrast oil objective, 1–2 frames/s) to observe their detailed behavior or low magnification and frame rate (10× phase objective, 2 frames/min) to assess their directionality.

cAMP Chemotaxis (Insall Chamber)

Cells were allowed to develop on plastic dishes in 10 mm phosphate buffer, pH 6.5 containing 2 mm MgCl2 and 1 mm CaCl2. To ensure all strains reached an equivalent stage of development before being used, they were filmed (10× phase contrast, 1 frame/15 s) and harvested when synchronous movement was observed. cAMP chemotaxis assays using the Insall chemotaxis chamber were performed as described (14).

Total Internal Reflection Fluorescence Microscopy

Cells were transfected with the plasmid pDM641 (co-expression vector for GFP-ARPC4 and LifeAct red fluorescent protein) and selected using hygromycin (50 μg/ml) as described (15). Transformants were observed using total internal reflection fluorescence microscopy as described (16). To measure spot lifetimes, image stacks were opened in ImageJ and resliced so that spots appeared as continuous lines, which were directly measured using the Line tool. To measure spot generation frequency, images were converted to 8-bit, and the ImageJ plugin SpotTracker was used to enhance spots (using a 1.25-pixel-diameter threshold). Resultant image stacks were threshold-adjusted, and the Analyze Particles tool was used to identify all spots present that were between 4 and 40 square pixels in size. Spot generation rate was normalized for the previously calculated lifetimes.

Endocytosis

Uptake of membrane was measured using the lipophilic dye FM1-43 as described (17).

RESULTS

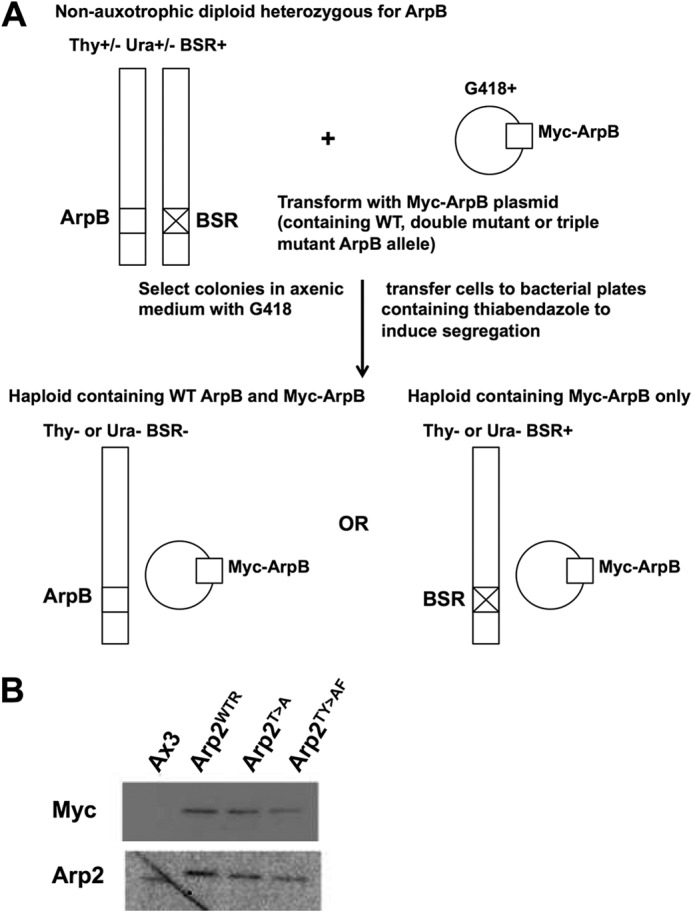

Replacement of the Arp2 Gene with Phosphorylation-deficient Mutants

To explore the role of phosphorylation in Arp2 function, we replaced the Dictyostelium arpB gene with alleles encoding unphosphorylatable mutants. Because Arp2 is essential for viability, we used the established diploid system (11) (Fig. 1). Briefly, a heterozygote with one wild-type and one knocked out copy of arpB was transfected with an extrachromosomal vector encoding Myc-tagged wild-type Arp2 or mutant Arp2 lacking identified phosphorylation sites. Transformants were segregated to form haploids. Clones inheriting a genomic arpB knock-out rescued by the Myc-tagged extrachromosomal copy were recognized by loss of the smaller, untagged Arp2 (Fig. 1B). We obtained clones containing the replacement arpB alleles and named these strains Arp2WTR (arpB− rescued with wild-type arpB), Arp2T>A (Arp2 double mutant containing T235A/T236A substitutions), and Arp2TY>AF (Arp2 triple mutant containing T235A/T236A and Y200F). The growth rates of the strains were comparable (doubling time in shaking axenic culture ranging between 14 and 18 h in different experiments), although all replacements grew more slowly than unaltered Ax3 cells (average doubling time, 10.5 h). All replacement strains were also able to grow on bacterial plates. Cell size was not altered in the replacement strains: for cells growing in axenic medium on plastic dishes, mean cell sizes were10.3 (Ax3), 10.2 (Arp2WTR), 9.7 (Arp2T>A), and 10.0 μm (Arp2TY>AF). By comparison, mutants in the SCAR complex become substantially smaller (18). These results demonstrate that phosphorylation on Tyr-200, Thr-235, and Thr-236 is not essential for the role of Arp2 in cell viability. These data also imply that Arp2 unphosphorylatable mutations do not affect structural integrity of the Arp2/3 complex because Arp2 is essential for Dictyostelium growth (11). This is consistent with our previous data that recombinant human Arp2/3 complex with an unphosphorylatable Arp2 mutant is assembled correctly with unchanged subunit stoichiometry but reduced actin nucleating activity (9).

FIGURE 1.

Replacement of endogenous arpB by mutant alleles. A, the parent diploid strain DJK45 carries one intact copy of arpB (on chromosome 2) and a second copy that has been disrupted by insertion of the blasticidin S resistance (BSR) gene. DJK45 is also heterozygous for Thy and Ura by virtue of having the endogenous ura locus completely disrupted and one copy of the thy locus disrupted by insertion of the ura locus into it (on chromosome 3). Therefore, haploid replacements must be auxotrophic either for Thy or Ura and be blasticidin- and G418-resistant (11). B, Western blots probed with anti-Myc and anti-Arp2 show that the three replacement strains carry only the introduced epitope-tagged version of Arp2 and no endogenous Arp2.

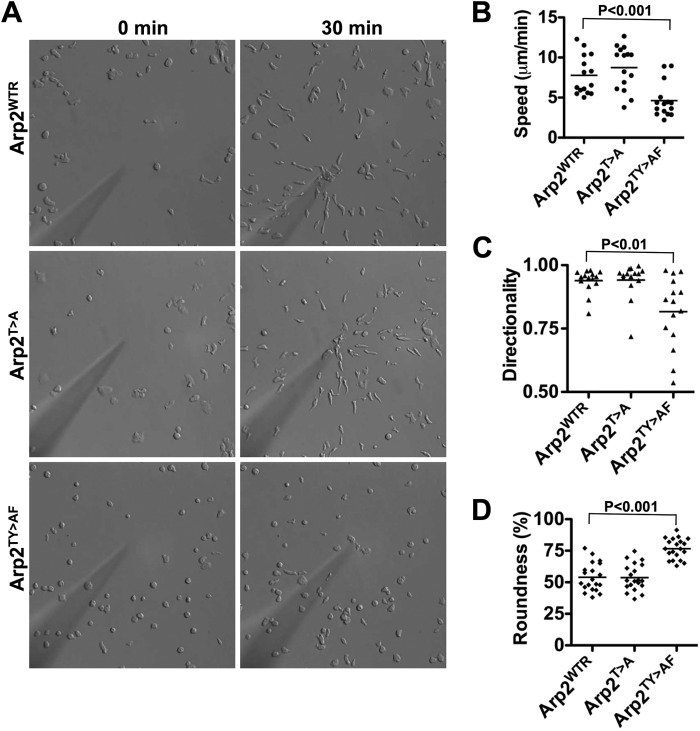

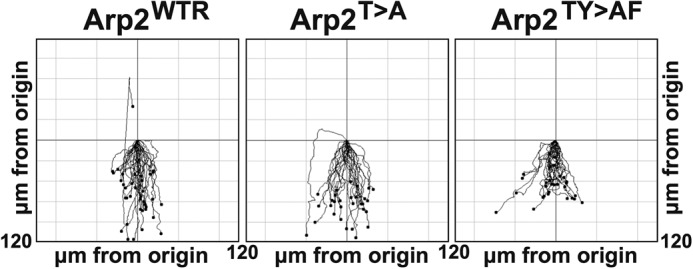

Chemotaxis toward cAMP Is Impaired in Arp2TY>AF Cells

Because of the importance of the Arp2/3 complex in cell migration, we tested chemotaxis of Arp2 mutant cells toward cAMP. Cells were developed by stimulating with cAMP every 6 min for 5 h after which chemotaxis toward a point source of cAMP was measured by live cell videomicroscopy. Arp2WTR cells acquired an elongated morphology in response to cAMP and migrated at a speed of 7.78 ± 2.44 μm/min with a directionality of 0.94 ± 0.05 (Fig. 2, A–C, and supplemental Movie 1), which was not significantly different from Ax3 cells (supplemental Fig. S1). The morphology, speed, and directionality of Arp2T>A were also similar to Arp2WTR (Fig. 2, A–C, and supplemental Movie 2). However, most Arp2TY>AF cells failed to adopt an elongated morphology and migrated at a significantly slower speed of 4.62 ± 2.13 μm/min and more randomly as indicated by a reduced and greatly variable directionality of 0.82 ± 0.14 (Fig. 2, A–C, and supplemental Movie 3). Scoring morphological roundness as an index of polarity revealed that Arp2TY>AF cells were less polarized (76.6 ± 8.12%) compared with Arp2WTR (54.0 ± 11.2%) and Arp2T>A cells (53.8 ± 10.6%) (Fig. 2D). Impaired chemotaxis of Arp2TY>AF cells but not Arp2T>A cells suggests that phosphorylation of Arp2 at either threonines or tyrosine is necessary for full function, although the effects are less severe than the loss of Arp2/3 complex activity reported for A. castellani, Drosophila (8), and human (9) cells.

FIGURE 2.

Chemotaxis and polarity are impaired in developed Arp2TY>AF cells. Chemotaxis toward cAMP of cells pulsed with cAMP for 5 h was recorded for 30 min. A, Arp2WTR and Arp2T>A cells acquired a polarized elongated morphology and moved toward the tip of a micropipette releasing cAMP. Arp2TY>AF cells chemotaxed inefficiently with significantly decreased speed (B), directionality (C), and morphological elongation (D). Lines are the mean value of cell behavior.

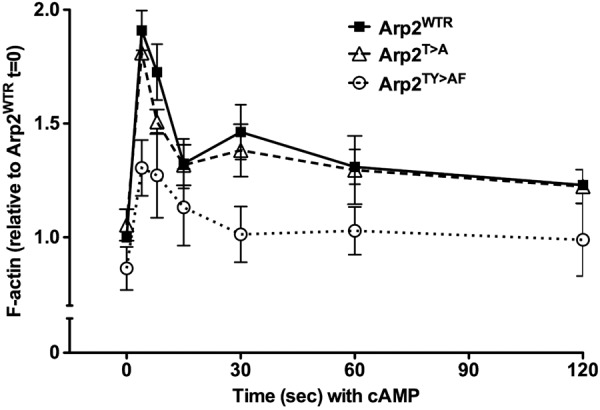

Consistent with impaired chemotaxis and polarity toward a gradient of cAMP, Arp2TY>AF cells had attenuated de novo assembly of F-actin in response to a uniform concentration of 2 μm cAMP. Arp2WTR and Arp2T>A cells had a characteristic biphasic increase in F-actin with a 1.91-fold increase over basal at 4 s in the first phase and a 1.46-fold increase at 30 s in the second phase (Fig. 3) similar to Ax3 cells (supplemental Fig. S2). In response to cAMP, the kinetics, -fold increase, and total F-actin in Arp2TY>AF cells were markedly different compared with Arp2WTR cells (Fig. 3). The first phase was prolonged, and the second phase was nearly absent. Although total F-actin did increase in Arp2TY>AF cells, the maximal abundance in the first phase was significantly less than in Ax3, Arp2WTR, and Arp2T>A cells. Hence, in response to cAMP, developed Arp2TY>AF cells showed reduced chemotaxis, adopted a less polarized morphology, and had attenuated F-actin abundance.

FIGURE 3.

F-actin assembly in response to a uniform concentration of cAMP is impaired in Arp2TY>AF cells. Cells pulsed with cAMP for 5 h were stimulated with 2 μm cAMP, and aliquots of cells were taken at the indicated times. Total F-actin was determined by fluorescence of rhodamine-phalloidin in Triton X-100-insoluble fractions and expressed relative to F-actin of Arp2WTR cells at time 0 in the absence of cAMP. During the first phase response to cAMP, maximum F-actin at 4 s was significantly less in Arp2TY>AF cells than in Arp2WTR or Arp2TY>AF cells, and the second phase of F-actin assembly seen in Arp2WTR and Arp2T>A cells was absent in Arp2TY>AF cells. Data are means ± S.E. (error bars) of three independent cell preparations.

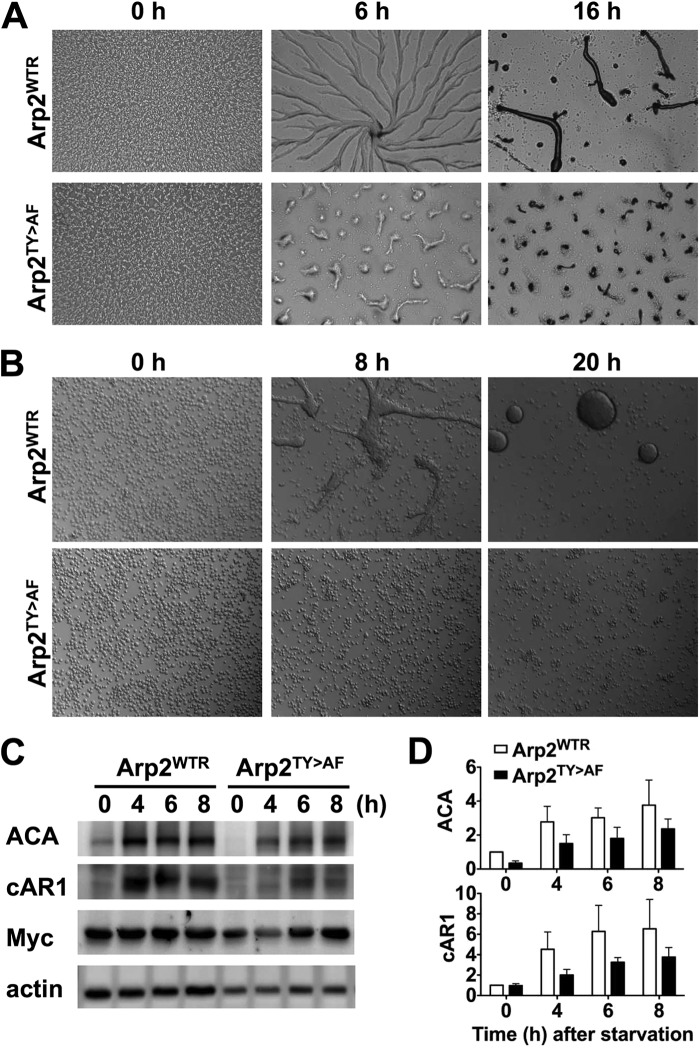

Arp2TY>AF Cells Have Delayed Development

We next asked whether impaired chemotaxis of Arp2TY>AF cells could in part be due to delayed development. Upon starvation, Dictyostelium cells undergo a developmental program that includes expression of genes necessary for chemotactic competence to cAMP, promoting cell aggregation and the formation of multicellular fruiting bodies. On non-nutrient agar plates, starved Arp2WTR cells formed streams and an aggregation center at 6 h, and they culminated into fruiting bodies at 16 h (Fig. 4A). In contrast, although Arp2TY>AF cells formed small aggregates, streams were not visible at 6 h, and aberrant, small fruiting bodies formed at 16 h. Development of Arp2TY>AF cells was more markedly impaired under the more stringent condition of being submerged in non-nutrient buffer. Arp2WTR and Arp2T>A cells formed streams at 8 h and tight aggregates at 20 h (Fig. 4B and supplemental Movies 4 and 5). Arp2TY>AF cells failed to aggregate at 8 h and had formed only a few small, loose aggregates at 20 h (Fig. 4B and supplemental Movie 6).

FIGURE 4.

Arp2TY>AF cells have delayed development. A, development on non-nutrient agar plates. From representative images taken at the indicated times, Arp2WTR cells showed streams at 6 h and fruiting bodies at 16 h. In contrast, Arp2TY>AF cells formed smaller aggregates at 6 h and defective fruiting bodies at 16 h. B, submerged development. From representative images taken at the indicated times, Arp2WTR cells formed substantial tight aggregates at 8 h, but Arp2TY>AF cells failed to develop aggregates at 8 h and showed a few small, loose aggregates 20 h. C, expression of early developmental marker genes, indicated by immunoblotting cell lysates for ACA and the cAR1, was delayed and attenuated in Arp2TY>AF cells compared with Arp2WTR cells. Myc immunoblot shows similar expression of Myc-tagged Arp2 in Arp2WTR and Arp2TY>AF cells. D, quantitative analysis of ACA and cAR1 expression during development. All data were normalized to actin and are shown relative to the expression in Arp2WTR at 0 h. Data are means ± S.E. (error bars) of three independent cell preparations.

Starvation-induced expression of cAR1 and ACA, which produces cAMP, was delayed and attenuated in Arp2TY>AF (Fig. 4C). Immunoblotting cell lysates revealed that ACA and cAR1 expression in Arp2WTR (Fig. 4C) and Arp2T>A cells (data not shown) rapidly increased at 4 h, and this increased level was sustained at 8 h. In contrast, their expression in Arp2TY>AF cells gradually increased until 8 h, and the abundance was markedly less. Quantitative analysis showed that at 4 and 6 h the average abundance of ACA and cAR1 in Arp2TY>AF was significantly less than in Arp2WTR cells (p < 0.05; n = 3) (Fig. 4D). Immunoblotting the replaced copy of Arp2 with anti-Myc antibodies indicated similar expression in Arp2WTR and Arp2TY>AF cells (Fig. 4C) that was unchanged at 14 h of starvation (data not shown). These data clearly, and unexpectedly, show that Arp2 phosphorylation is important for normal development.

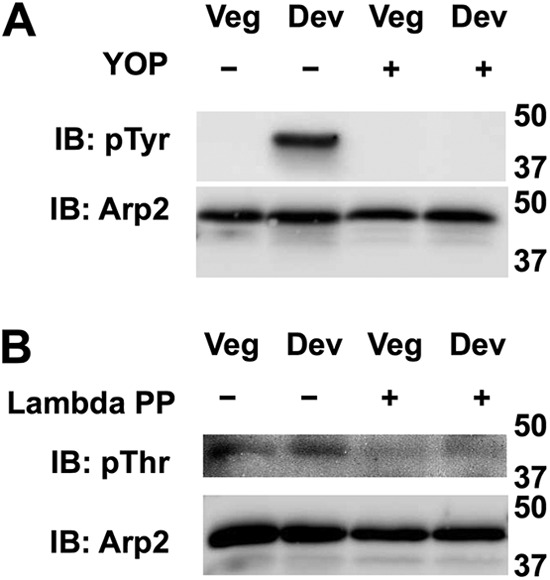

Tyrosine Phosphorylation of Arp2 Increases during Development

We next asked whether Arp2 phosphorylation changes during development. Arp2/3 complex in lysates from vegetative and 5-h-developed cells was affinity-enriched using GST-fused SCAR-VCA domain, and phosphorylation was determined by immunoblotting with phosphotyrosine- or phosphothreonine-specific antibodies. Myc-tagged Arp2 was pulled down by GST-SCAR-VCA but not GST alone (data not shown). Tyrosine phosphorylation of Arp2 was not detected in vegetative cells, but a strong signal was observed in developed cells (Fig. 5). In contrast, threonine phosphorylation of Arp2 was seen in vegetative cells, but the abundance did not change in developed cells (Fig. 5). Specificity of the phosphotyrosine and phosphothreonine signal was confirmed by absence of labeling in SCAR-VCA complexes treated with YOP and λ-phosphatases, respectively (Fig. 5). These data confirm that native Arp2 in cells is phosphorylated on tyrosine and threonine residues, but only tyrosine phosphorylation increases in developed cells.

FIGURE 5.

Tyrosine phosphorylation of Arp2 increases during development. A, immunoblotting (IB) Arp2/3 complex affinity-enriched by GST-SCAR-VCA with phosphotyrosine-specific antibodies indicated tyrosine phosphorylated Arp2 was not detected in vegetative (Veg) cells but induced in developed (Dev) cells. Phosphotyrosine (pTyr) labeling was absent in samples treated with YOP phosphatase. B, immunoblotting affinity-enriched complexes with phosphothreonine (pThr)-specific antibodies showed phosphorylation of Arp2 subunit in vegetative cells that did not increase in developed cells and was absent in samples treated with λ-phosphatase (PP).

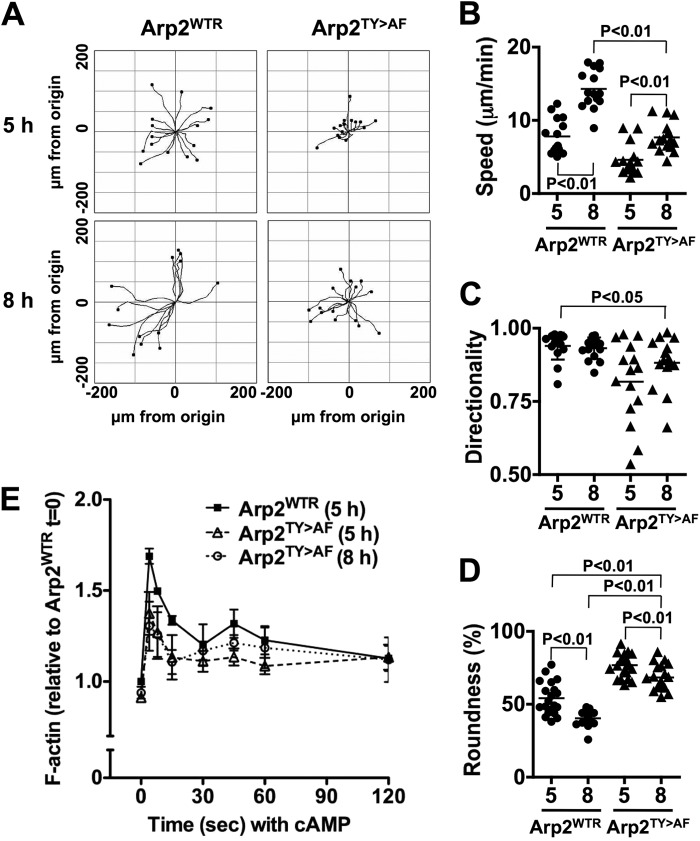

Longer Development of Arp2TY>AF Cells Partially Restores Chemotaxis but Not Initial F-actin Assembly

The developmental defects in Arp2TY>AF cells could contribute to their impaired chemotactic competence. To separate effects of development and migration, we tested whether longer development of Arp2TY>AF cells could restore chemotaxis, scoring for migration trajectory toward cAMP and cell morphology (Fig. 6A). Although ACA and cAR1 expression in Arp2TY>AF cells was attenuated because the abundance of ACA and cAR1 at 8 h was ∼80% of that of Arp2WTR cells at 4 h (Fig. 4D), we used cells starved for 8 h. To visualize chemotactic behavior over time, we plotted the trajectory of cells migrating toward the cAMP source for 20 min. Longer development increased migration of both Arp2WTR and Arp2TY>AF cells (Fig. 6A). Further analysis of these data indicated that Arp2WTR cells developed for 8 h had significantly increased chemotaxis speed compared with 5-h development (Fig. 6B) with no change in directionality (Fig. 6C). Arp2WTR cells developed for 8 h also had a more elongated morphology as indicated by significantly reduced roundness compared with Arp2WTR cells developed for 5 h (Fig. 6D). Longer development of Arp2TY>AF cells also increased chemotaxis speed to an average value that was similar to that of Arp2WTR cells at 5 h but significantly less than that of Arp2WTR cells at 8 h (Fig. 6B). Although directionality of Arp2TY>AF cells at 8 h increased slightly, it was not significantly different from that of Arp2TY>AF cells at 5 h but was different from that of Arp2WTR cells at 5 and 8 h (Fig. 6C). There was also less variability in directionality of Arp2TY>AF cells at 8 h compared with 5 h. Longer development of Arp2TY>AF cells partially restored morphological polarity, although cells remained more round than Arp2WTR cells at 5 and 8 h (Fig. 6D). The kinetics of actin polymerization and abundance of F-actin were not different in Arp2WTR cells developed for 5 and 8 h (data not shown). Longer development of Arp2TY>AF cells partially restored the second phase but not the first phase of F-actin assembly in response to cAMP (Fig. 6E). The weaker chemotaxis of Arp2TY>AF cells despite increased expression of cAR1 and ACA with longer development suggests that defective F-actin assembly in response to cAMP was not simply caused by lower receptor expression.

FIGURE 6.

Longer development time of Arp2TY>AF cells partially rescues impaired chemotaxis but not F-actin abundance with cAMP. When pulsed with cAMP for 8 h, Arp2TY>AF cells had increased speed and directionality compared with cells pulsed with cAMP after 5 h of development, but they remained less polarized than Arp2WTR cells. A, tracks of 15 cells chemotaxing for 20 min were used to determine speed (B), directionality (C), and roundness (D). Speed and directionality but not roundness of Arp2TY>AF cells were mostly restored with a longer development time. E, cAMP-induced F-actin assembly shows that longer development time of Arp2TY>AF cells has no effect on F-actin abundance during the first phase but partially restores a second phase response. Data are means ± S.E. (error bars) of three independent cell preparations. Lines are the mean value of cell behavior.

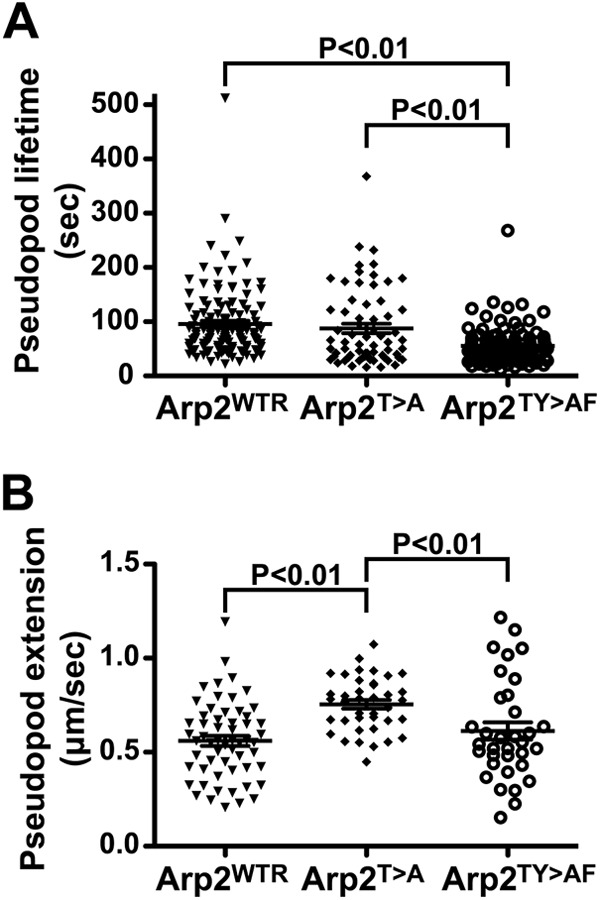

Longer Development of Arp2TY>AF Cells Does Not Restore Wild-type cAMP Chemotaxis under Agarose

To further examine effects of the Arp2 mutant on cAMP chemotaxis, we made use of the under-agarose chemotaxis assay (19). In this assay, the spatial limitations imposed by the agarose allow pseudopod behavior to be imaged in greater detail. Arp2TY>AF cells showed a clear defect in pseudopod lifetime, which was reduced by roughly 40% compared with Arp2WTR and Arp2T>A cells (Fig. 7A and supplemental Movie 7). There was no defect in the instantaneous speed of pseudopod extension in either of the mutant Arp2 strains with Arp2T>A cells even showing pseudopod speed increased by 20–30% compared with the other two strains (Fig. 7B). The shorter lifetime of Arp2TY>AF pseudopods may reflect the reduced second phase of actin polymerization seen in these cells.

FIGURE 7.

Pseudopod behavior during chemotaxis to cAMP under agarose. Cells were starved and pulse-developed for a total of 5 (Arp2WTR and Arp2T>A) or 7 h (Arp2TY>AF). A, analysis of pseudopod dynamics showed that Arp2TY>AF cells had shorter lived pseudopods than either Arp2WTR or Arp2T>A cells (p < 0.01). Derived values of mean ± S.E. were 95.8 ± 5.7 (Arp2WTR), 87.5 ± 8.7 (Arp2T>A), and 55.3 ± 3.3 s (Arp2TY>AF). B, the instantaneous pseudopod extension speed of Arp2TY>AF cells was not different from Arp2WTR cells, but Arp2T>A cells showed more rapid pseudopod extension than either of these strains (p < 0.01). Derived values of mean ± S.E. were 0.56 ± 0.03 (Arp2WTR), 0.75 ± 0.02 (Arp2T>A), and 0.61 ± 0.05 μm/s (Arp2TY>AF). Graphs show the data plotted with mean (line) and S.E. (bar) indicated. See also supplemental Movie 7.

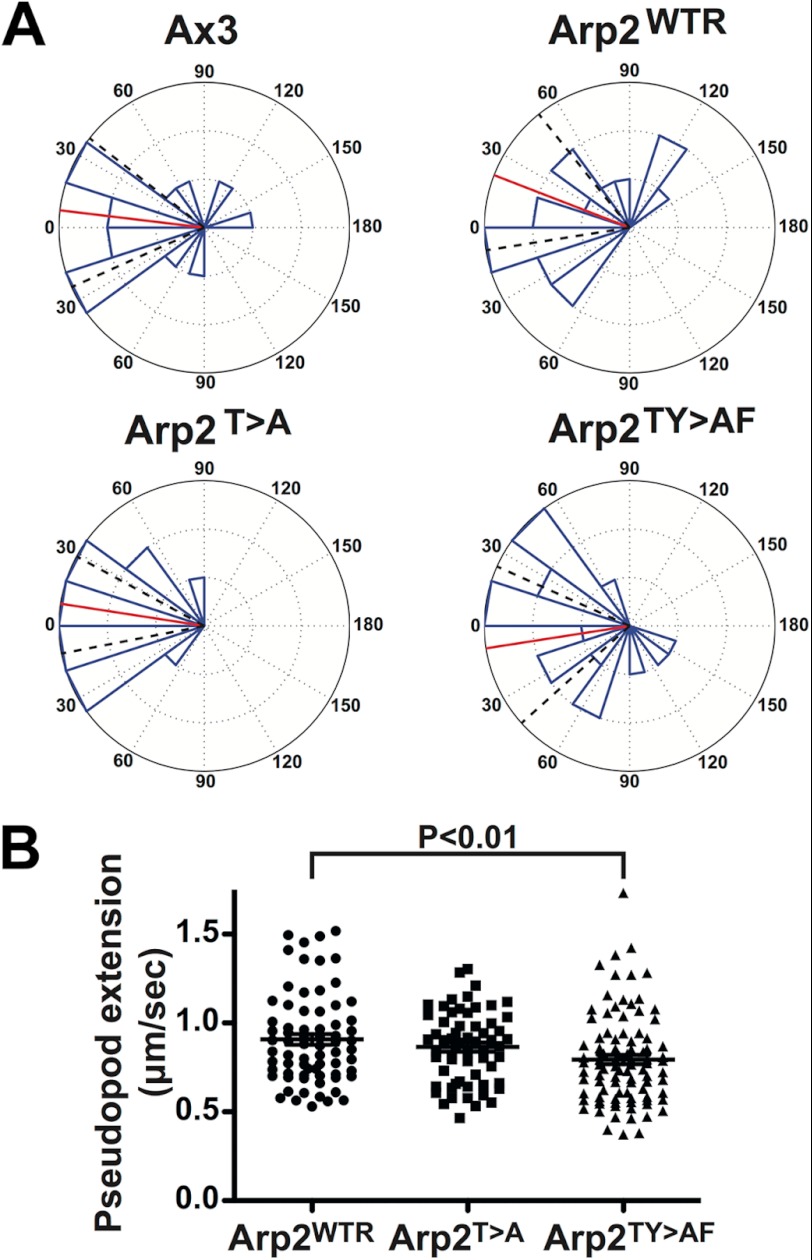

Vegetative Arp2TY>AF Cells Have Minor Defects in Folate Chemotaxis

The delayed development of Arp2TY>AF cells made it difficult to determine whether impaired chemotaxis was in part or entirely due to defective development. We therefore examined chemotaxis of vegetative cells up a gradient of folic acid using under-agarose assays (Fig. 8A and supplemental Movie 8). Under these conditions, Arp2TY>AF had minor defects in chemotactic behavior that were more modest than those described for cAMP chemotaxis (Fig. 8A and Table 1), including a 10% slower overall speed of movement than Arp2WTR cells. However, speed was not significantly different from Arp2T>A cells. Arp2TY>AF cells also had a 12.5% slower pseudopod extension speed than Arp2WTR cells, but Arp2T>A cells did not differ significantly from the other two strains (Fig. 8B). Thus, the phosphorylation sites were not essential for the Arp2/3 complex function in vegetative cells using the under-agarose chemotaxis assay, although there were small but clearly measurable defects in Arp2TY>AF cells. The under-agarose assay can mask a number of problems with migrating cells. For example, vegetative scar− cells are essentially nonmotile under liquid on a plastic surface but migrate at a substantial fraction of the speed of wild-type cells under agar due to a complex adhesion defect (20). Thus, the behavior of Arp2TY>AF under agar implies that the fundamental mechanisms of pseudopod generation are intact, but the refinement and control are defective.

FIGURE 8.

Chemotaxis of vegetative cells to folic acid. Cells moving under agarose in a gradient of folic acid were tracked. A, results from one typical experiment presented as a rose plot (number of cells, 16–18 for each strain). The red line shows the mean cell behavior, and the dotted black lines show the 95% confidence intervals. Signal is directly at the left. A summary of these data is shown in Table 1. B, instantaneous pseudopod speed of Arp2 replacement strains. Data are combined from three different experiments. Derived values for the mean ± S.E. are 0.91 ± 0.03 (Arp2WTR), 0.86 ± 0.03 (Arp2T>A), and 0.79 ± 0.03 μm/s (Arp2TY>AF). The Arp2TY>AF pseudopod extension speed is significantly slower than that of Arp2WTR (p < 0.01). Data are plotted with mean (line) and S.E. (bar) indicated. See also supplemental Movie 8.

TABLE 1.

Parameters derived from under-agarose chemotaxis toward folate

Values are mean ± S.D.

| Cell line | Chemotactic index | Total speed of movement | Speed of movement up gradient |

|---|---|---|---|

| μm/min | μm/min | ||

| Ax3 | 0.79 ± 0.25 | 11.9 ± 1.7 | 4.2 ± 3.2 |

| Arp2WTR | 0.76 ± 0.23 | 11.3 ± 1.7 | 5.2 ± 1.8 |

| Arp2T>A | 0.84 ± 0.24 | 10.8 ± 2.7 | 5.7 ± 3.1 |

| Arp2TY>AF | 0.77 ± 0.22 | 10.1 ± 1.6a | 4.3 ± 2.2 |

a p < 0.05 with respect to Ax3 and Arp2WTR.

Vegetative Arp2TY>AF Cells Have Normal Clathrin Behavior

As another index of Arp2/3 function in vegetative cells, we examined sites of clathrin-mediated endocytosis because the Arp2/3 complex is associated with these sites in Dictyostelium cells. We transfected the strains with a plasmid encoding both GFP-ARPC4 (to mark the Arp2/3 complex) and the F-actin marker LifeAct monomeric red fluorescent protein. Endocytic events were visualized in total internal reflection fluorescence microscopy as transient spots on the basal surface of the cell (supplemental Movie 9). The lifetime of the spots was assessed in the three Arp2 replacement strains as well as in Ax3 cells (Table 2). There was no significant difference in the GFP-ARPC4 spot lifetime for Ax3, Arp2WTR, or Arp2TY>AF. The GFP-ARPC4 spot lifetime was significantly increased in the Arp2T>A cells. The frequency of endocytic spot generation (normalized for these lifetimes) was found to be equivalent in all strains, ∼0.5–0.6 events/min/μm2 of surface area (data not shown). Despite the extended lifetime of Arp2T>A endocytic spots, we did not observe any significant difference in the rate of uptake of the lipophilic dye FM1-43 (a marker of membrane internalization; data not shown). This is perhaps not surprising because a clathrin mutant itself shows little disruption of dye uptake in such an assay (21).

TABLE 2.

Lifetimes of the Arp2/3 complex spots during endocytosis

Values are mean ± S.D.

| Cell line | Spot lifetime |

|---|---|

| s | |

| Ax3 | 20.8 ± 5.3 |

| Arp2WTR | 20.5 ± 4.0 |

| Arp2T>A | 25.5 ± 6.1a |

| Arp2TY>AF | 20.5 ± 5.7 |

a p < 0.01 with respect to Ax3, Arp2WTR, and Arp2TY>AF.

Analysis of Chemotaxis to cAMP in Arp2TY>AF Cells Free from Developmental Bias

To further investigate the apparent differences in chemotaxis of developed and vegetative Arp2TY>AF cells, we sought an unbiased method to determine efficiency of chemotaxis toward cAMP that would not be influenced by developmental factors. We plated the cells at high density onto plastic dishes in phosphate buffer with 2 mm MgCl2 and 1 mm CaCl2. Cells were allowed to develop until they began to show synchronous movement. Under these conditions, Arp2WTR and Arp2T>A cells developed at similar rates, but Arp2TY>AF cells took up to 5 h extra to reach the onset of streaming. Arp2TY>AF cells also showed defects in cell elongation and aggregation, which involved a high degree of cell collision rather than proper streaming. Nevertheless, cells were able to generate cAMP signals and undergo synchronous movement. At this stage, cells were harvested from the dishes and placed in an Insall chamber (14) in a gradient of cAMP. Their movement was then filmed over typically a 30-min period (supplemental Movie 10). The chemotactic parameters of the cells under these conditions are summarized in Fig. 9 and Table 3. When all strains were allowed to reach an equivalent highly responsive state of development, their chemotaxis toward cAMP was more similar than when cells were taken at predetermined time points. Under these conditions, Arp2TY>AF cells showed little difference in total cell speed and directionality. However, they showed a significantly reduced speed of chemotaxis up the cAMP gradient. These data suggest a direct importance of Arp2 phosphorylation in chemotaxis of developed cells independent of delayed development.

FIGURE 9.

Chemotaxis of self-pulsed cells to cAMP in Insall chamber. Cells harvested after they had initiated synchronous movement under buffer were placed in a cAMP gradient in an Insall chamber, and their movement was filmed over 30 min. Signal is directly at the bottom. Each line represents a different cell. Results shown are from one typical experiment. See also supplemental Movie 10.

TABLE 3.

Insall chamber chemotaxis of cells toward cAMP

Values are mean ± S.D.

| Cell line | Chemotactic index | Total speed of movement | Speed of movement up gradient |

|---|---|---|---|

| μm/min | μm/min | ||

| Arp2WTR | 0.98 ± 0.02 | 7.2 ± 1.7 | 5.5 ± 1.7 |

| Arp2T>A | 0.97 ± 0.03 | 7.3 ± 1.6 | 5.5 ± 1.3 |

| Arp2TY>AF | 0.95 ± 0.08 | 6.9 ± 1.4 | 4.3 ± 1.2a |

a p < 0.01 with respect to Arp2WTR and Arp2T>A.

DISCUSSION

Our findings reveal a role for Arp2 phosphorylation in selective cell functions recognized as requiring Arp2/3 complex activity. Mutations that prevent phosphorylation of Dictyostelium Arp2 Thr-235/236 and Tyr-200 do not disrupt complex assembly or endocytosis in vegetative cells and have only minor defects in chemotaxis to folate. However, development and cAMP chemotaxis are more markedly impaired, and the amount of stimulus-induced F-actin is attenuated. Impaired chemotaxis and F-actin assembly in response to cAMP by Arp2TY>AF cells but not Arp2T>A cells are consistent with previous findings that phosphorylation of Arp2 threonine or tyrosine sites functions as a logical or gate (8), although in Dictyostelium some nucleating activity may be retained with loss of phosphorylation at these sites.

We recently showed that a network of salt bridge interactions at the interface of the Arp2, Arp3, and ARPC4 subunits hold the Arp2/3 complex in an inactive orientation and that phosphorylation of Arp2 destabilizes these interactions to induce an activation-competent state (9). However, we cannot rule out the possibility of alternative mechanisms causing an activation-competent state to explain why chemotaxis with folate and endocytosis are not as dramatically impaired in Arp2TY>AF cells. The reported phosphorylation of Arp3 (8), ARPC1 (8, 22), and ARPC5 (23) subunits or an association with regulatory proteins like cortactin (24) might also generate conformational changes in the Arp2/3 complex that similarly promote NPF-induced nucleating activity. Whether distinct potencies of Arp2/3 complex nucleating activity are necessary for different actin-dependent processes remains unknown. Whether there are differences in F-actin dynamics between developed and vegetative Dictyostelium cells is an unresolved question that could be answered using the Arp2TY>AF replacement clone. Normal endocytosis by Arp2TY>AF cells could also reflect differences in the potency of Arp2/3 complex nucleating activity or the ability of different NPFs to stimulate activity of the complex. Although Arp2 phosphorylation is necessary for full nucleating activity of Arp2/3 complex with the NPFs SCAR and N-WASP, its role in activation of the complex by other NPFs remains undetermined. The NPF WASP and Scar homolog (WASH) for example is essential for exocytosis of indigestible material (25), and WASP and Scar homolog (WASH) is predicted to act in concert with other types of actin nucleators, including formins (26). There is also the possibility that in vegetative but not developed cells reduced activity of Arp2/3 complex may be compensated by other nucleators such as formins (27, 28).

Our data also show a critical role for Arp2 phosphorylation in time-dependent development and a substantial increase in tyrosine phosphorylation in developed compared with vegetative cells. An important future direction is determining the signaling mechanism and likely tyrosine kinase regulating Arp2 phosphorylation during development. Delayed development of Arp2TY>AF cells is consistent with multicellular development requiring directed migration. However, previous work showed that replacement transformants with partial loss of function in p34-arc and Arp2 have normal timing of development despite having attenuated F-actin polymerization with delayed kinetics compared with wild-type cells (12). Proper organization of actin cytoskeleton is necessary for cAMP signaling required for development (29). Additionally, cells expressing an unphosphorylatable actin mutant (Y53A) have delayed development (29) and attenuated expression of cAR1 and ACA but normal vegetative growth rates and phagocytosis similar to what we observed in Arp2TY>AF cells. Mutant cells lacking the actin cross-linking proteins cortexillins I and II have severe defects in cAMP signaling required for early development of Dictyostelium (30). Additionally, the Arp2/3 complex was recently shown to be important for vesicle trafficking (31, 32). Further studies will be necessary to reveal precisely how Arp2 phosphorylation promotes Dictyostelium development.

Our data with the Insall chamber and with longer development of Arp2TY>AF suggest distinct roles for Arp2 phosphorylation independent of development, including chemotaxis speed and directionality, polarity, and the first phase of F-actin assembly in response to cAMP. Longer development of Arp2TY>AF cells increased cAR1 and ACA expression similar to levels in Arp2WTR cells and partially restored the second phase but not the first phase of F-actin polymerization. However, other mutations of the Arp2/3 complex abolish both phases of the F-actin response (12). One current view is that the second phase determines pseudopod extension and is dependent on phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase activity (33). Longer development increases basal ACA activity and cAMP production (34) and rescues chemotaxis of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase-null cells (35). Thus, increased movement of 8-h-developed Arp2TY>AF cells could reflect partial recovery of pathways that regulate the second F-actin phase.

Coincidence detection requiring two or more regulatory inputs is an increasingly recognized signaling mode controlling cytoskeleton-associated proteins. N-WASP activity requires binding of Cdc42-GTP and either phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate, profilin. or the adaptor protein Nck (36–38). Cofilin activity requires dephosphorylation of an amino-terminal serine and release from phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate binding at the plasma membrane, the latter facilitated by deprotonation of His-133 with increased intracellular pH (39). Our study suggests coincidence regulation for increased nucleating activity of the Arp2/3 complex that includes the well established binding of NPFs to the complex and the more recently identified phosphorylation of the Arp2 subunit.

During the completion of our study, two reports were published on Arp2/3-dependent directed cell migration using genetic ablation of specific Arp2/3 complex subunits that showed conflicting findings (40, 41). Fibroblasts derived from Ink4a/Arf-deficient mice do not form lamellipodia but retain directional movement toward a growth factor chemoattractant (40). In contrast, fibroblasts differentiated from embryonic stem cells isolated from mice with a targeted deletion of the ARPC3 gene also do not form lamellipodia, but they lack directional movement toward a growth factor chemoattractant (41). Defective pseudopod persistence could explain why Arp2TY>AF cells showed different chemotactic ability between cAMP and folate because developed wild-type cells adopt a highly elongated morphology and exhibit stronger directional persistence to a cAMP gradient, but the incompatibility of these two studies mentioned above emphasizes that the role of Arp2/3 complex in migration is complex.

Overall, the requirement for Arp2 phosphorylation in some but not all of the predicted roles for Arp2/3 complex in Dictyostelium illustrates the underlying complexity of cell biological processes. Our work raises questions and identifies valuable tools for further study on the integration of multiple pathways, the mechanisms by which actin polymerization is regulated in different contexts, and the detailed roles of actin and Arp2/3 complex in normal cell behavior.

Acknowledgments

We thank Lawrence LeClaire and Andre Schönichen for helpful discussions and Gabriela Kalna for help with statistical analysis. Work by C. C. and D. L. B. was conducted in a facility constructed with support from Research Facilities Improvement Program Grant C06 RR16490 from the National Center for Research Resources, National Institute of Health.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grant GM58642 (to D. L. B.). This work was also supported by Medical Research Council Grant G117/537 and a Cancer Research UK core grant (to R. H. I.).

This article contains supplemental Figs. S1 and S2, Table S1, and Movies 1–10.

- Arp

- actin-related protein

- cAR1

- cAMP receptor 1

- ACA

- adenylyl cyclase A

- NPF

- nucleation-promoting factor

- WASP

- Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome protein

- SCAR

- Suppressor of cAMP Receptor

- VCA

- Verprolin homology, Central and Acidic

- WASH

- WASP and SCAR homolog.

REFERENCES

- 1. Insall R. H., Machesky L. M. (2009) Actin dynamics at the leading edge: from simple machinery to complex networks. Dev. Cell 17, 310–322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Mullins R. D., Heuser J. A., Pollard T. D. (1998) The interaction of Arp2/3 complex with actin: nucleation, high affinity pointed end capping, and formation of branching networks of filaments. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 95, 6181–6186 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Amann K. J., Pollard T. D. (2001) The Arp2/3 complex nucleates actin filament branches from the sides of pre-existing filaments. Nat. Cell Biol. 3, 306–310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Goley E. D., Welch M. D. (2006) The ARP2/3 complex: an actin nucleator comes of age. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 7, 713–726 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Higgs H. N., Blanchoin L., Pollard T. D. (1999) Influence of the C terminus of Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome protein (WASp) and the Arp2/3 complex on actin polymerization. Biochemistry 38, 15212–15222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Rouiller I., Xu X. P., Amann K. J., Egile C., Nickell S., Nicastro D., Li R., Pollard T. D., Volkmann N., Hanein D. (2008) The structural basis of actin filament branching by the Arp2/3 complex. J. Cell Biol. 180, 887–895 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Robinson R. C., Turbedsky K., Kaiser D. A., Marchand J. B., Higgs H. N., Choe S., Pollard T. D. (2001) Crystal structure of Arp2/3 complex. Science 294, 1679–1684 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. LeClaire L. L., 3rd, Baumgartner M., Iwasa J. H., Mullins R. D., Barber D. L. (2008) Phosphorylation of the Arp2/3 complex is necessary to nucleate actin filaments. J. Cell Biol. 182, 647–654 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Narayanan A., LeClaire L. L., 3rd, Barber D. L., Jacobson M. P. (2011) Phosphorylation of the Arp2 subunit relieves auto-inhibitory interactions for Arp2/3 complex activation. PLoS Comput. Biol. 7, e1002226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Insall R., Müller-Taubenberger A., Machesky L., Köhler J., Simmeth E., Atkinson S. J., Weber I., Gerisch G. (2001) Dynamics of the Dictyostelium Arp2/3 complex in endocytosis, cytokinesis, and chemotaxis. Cell Motil. Cytoskeleton 50, 115–128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Zaki M., King J., Fütterer K., Insall R. H. (2007) Replacement of the essential Dictyostelium Arp2 gene by its Entamoeba homologue using parasexual genetics. BMC Genet. 8, 28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Langridge P. D., Kay R. R. (2007) Mutants in the Dictyostelium Arp2/3 complex and chemoattractant-induced actin polymerization. Exp. Cell Res. 313, 2563–2574 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Choi C.-H., Patel H., Barber D. L. (2010) Expression of actin-interacting protein 1 suppresses impaired chemotaxis of Dictyostelium cells lacking the Na+-H+ exchanger NHE1. Mol. Biol. Cell 21, 3162–3170 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Muinonen-Martin A. J., Veltman D. M., Kalna G., Insall R. H. (2010) An improved chamber for direct visualisation of chemotaxis. PLoS One 5, e15309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Veltman D. M., Akar G., Bosgraaf L., Van Haastert P. J. (2009) A new set of small, extrachromosomal expression vectors for Dictyostelium discoideum. Plasmid 61, 110–118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Veltman D. M., Auciello G., Spence H. J., Machesky L. M., Rappoport J. Z., Insall R. H. (2011) Functional analysis of Dictyostelium IBARa reveals a conserved role of the I-BAR domain in endocytosis. Biochem. J. 436, 45–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Traynor D., Kay R. R. (2007) Possible roles of the endocytic cycle in cell motility. J. Cell Sci. 120, 2318–2327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ura S., Pollitt A. Y., Veltman D. M., Morrice N. A., Machesky L. M., Insall R. H. (2012) Pseudopod growth and evolution during cell movement is controlled through SCAR/WAVE dephosphorylation. Curr. Biol. 22, 553–561 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Insall R. H. (2010) Understanding eukaryotic chemotaxis: a pseudopod-centered view. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 11, 453–458 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Blagg S. L., Stewart M., Sambles C., Insall R. H. (2003) PIR121 regulates pseudopod dynamics and SCAR activity in Dictyostelium. Curr. Biol. 13, 1480–1487 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Aguado-Velasco C., Bretscher M. S. (1999) Circulation of the plasma membrane in Dictyostelium. Mol. Biol. Cell 10, 4419–4427 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Vadlamudi R. K., Li F., Barnes C. J., Bagheri-Yarmand R., Kumar R. (2004) p41-Arc subunit of human Arp2/3 complex is a p21-activated kinase-1-interacting substrate. EMBO Rep. 5, 154–160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Singh S., Powell D. W., Rane M. J., Millard T. H., Trent J. O., Pierce W. M., Klein J. B., Machesky L. M., McLeish K. R. (2003) Identification of the p16-Arc subunit of the Arp 2/3 complex as a substrate of MAPK-activated protein kinase 2 by proteomic analysis. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 36410–36417 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Weaver A. M., Karginov A. V., Kinley A. W., Weed S. A., Li Y., Parsons J. T., Cooper J. A. (2001) Cortactin promotes and stabilizes Arp2/3-induced actin filament network formation. Curr. Biol. 11, 370–374 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Carnell M., Zech T., Calaminus S. D., Ura S., Hagedorn M., Johnston S. A., May R. C., Soldati T., Machesky L. M., Insall R. H. (2011) Actin polymerization driven by WASH causes V-ATPase retrieval and vesicle neutralization before exocytosis. J. Cell Biol. 193, 831–839 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Campellone K. G., Welch M. D. (2010) A nucleator arms race: cellular control of actin assembly. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 11, 237–251 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kitayama C., Uyeda T. Q. (2003) ForC, a novel type of formin family protein lacking an FH1 domain, is involved in multicellular development in Dictyostelium discoideum. J. Cell Sci. 116, 711–723 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Schirenbeck A., Bretschneider T., Arasada R., Schleicher M., Faix J. (2005) The Diaphanous-related formin dDia2 is required for the formation and maintenance of filopodia. Nat. Cell Biol. 7, 619–625 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Shu S., Liu X., Kriebel P. W., Hong M. S., Daniels M. P., Parent C. A., Korn E. D. (2010) Expression of Y53A-actin in Dictyostelium disrupts the cytoskeleton and inhibits intracellular and intercellular chemotactic signaling. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 27713–27725 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Shu S., Liu X., Kriebel P. W., Daniels M. P., Korn E. D. (2012) Actin cross-linking proteins cortexillin I and II are required for cAMP signaling during Dictyostelium chemotaxis and development. Mol. Biol. Cell 23, 390–400 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Rajan A., Tien A. C., Haueter C. M., Schulze K. L., Bellen H. J. (2009) The Arp2/3 complex and WASp are required for apical trafficking of Delta into microvilli during cell fate specification of sensory organ precursors. Nat. Cell Biol. 11, 815–824 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Zech T., Calaminus S. D., Caswell P., Spence H. J., Carnell M., Insall R. H., Norman J., Machesky L. M. (2011) The Arp2/3 activator WASH regulates α5β1-integrin-mediated invasive migration. J. Cell Sci. 124, 3753–3759 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Chen L., Janetopoulos C., Huang Y. E., Iijima M., Borleis J., Devreotes P. N. (2003) Two phases of actin polymerization display different dependencies on PI(3,4,5)P3 accumulation and have unique roles during chemotaxis. Mol. Biol. Cell 14, 5028–5037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Das S., Rericha E. C., Bagorda A., Parent C. A. (2011) Direct biochemical measurements of signal relay during Dictyostelium development. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 38649–38658 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Takeda K., Sasaki A. T., Ha H., Seung H. A., Firtel R. A. (2007) Role of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinases in chemotaxis in Dictyostelium. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 11874–11884 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Prehoda K. E., Scott J. A., Mullins R. D., Lim W. A. (2000) Integration of multiple signals through cooperative regulation of the N-WASP-Arp2/3 complex. Science 290, 801–806 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Rohatgi R., Ho H. Y., Kirschner M. W. (2000) Mechanism of N-WASP activation by CDC42 and phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate. J. Cell Biol. 150, 1299–1310 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Higgs H. N., Pollard T. D. (2000) Activation by Cdc42 and PIP2 of Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome protein (WASp) stimulates actin nucleation by Arp2/3 complex. J. Cell Biol. 150, 1311–1320 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Frantz C., Barreiro G., Dominguez L., Chen X., Eddy R., Condeelis J., Kelly M. J., Jacobson M. P., Barber D. L. (2008) Cofilin is a pH sensor for actin free barbed end formation: role of phosphoinositide binding. J. Cell Biol. 183, 865–879 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Wu C., Asokan S. B., Berginski M. E., Haynes E. M., Sharpless N. E., Griffith J. D., Gomez S. M., Bear J. E. (2012) Arp2/3 is critical for lamellipodia and response to extracellular matrix cues but is dispensable for chemotaxis. Cell 148, 973–987 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Suraneni P., Rubinstein B., Unruh J. R., Durnin M., Hanein D., Li R. (2012) The Arp2/3 complex is required for lamellipodia extension and directional fibroblast cell migration. J. Cell Biol. 197, 239–251 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]