Background: Inflammation and fever are coincident during various disease states including sepsis.

Results: Co-exposure to inflammatory agonists during fever augments Hsp70 synthesis and extracellular release.

Conclusion: Coincident activation of TLR signaling and heat shock response could be detrimental.

Significance: The work examines the critical and complex interaction between inflammatory and heat shock response pathways in the context of sepsis and shock.

Keywords: Heat Shock Protein, Hyperthermia, Lipopolysaccharide (LPS), MAP Kinases (MAPKs), Sepsis, Alarmins, Fever, HSF1, Hsp70

Abstract

Heat shock protein (Hsp) 70 expression can be stimulated by febrile range temperature (FRT). Hsp70 has been shown to be elevated in serum of patients with sepsis, and when released from cells, extracellular Hsp70 exerts endotoxin-like effects through Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) receptors. Circulating TLR agonists and fever both persist for the first several days of sepsis, and each can activate Hsp70 expression; however, the effect of combined exposure to FRT and TLR agonists on Hsp70 expression is unknown. We found that concurrent exposure to FRT (39.5 °C) and agonists for TLR4 (LPS), TLR2 (Pam3Cys), or TLR3 (poly(IC)) synergized to increase Hsp70 expression and extracellular release in RAW264.7 macrophages. The increase in Hsp70 expression was associated with activation of p38 and ERK MAP kinases, phosphorylation of histone H3, and increased recruitment of HSF1 to the Hsp70 promoter. Pretreatment with the p38 MAPK inhibitor SB283580 but not the ERK pathway inhibitor UO126 significantly reduced Hsp70 gene modification and Hsp70 expression in RAW cells co-exposed to LPS and FRT. In mice challenged with intratracheal LPS and then exposed to febrile range hyperthermia (core temperature, ∼39.5 °C), Hsp70 levels in lung tissue and in cell-free lung lavage were increased compared with mice exposed to either hyperthermia or LPS alone. We propose a model of how enhanced Hsp70 expression and extracellular release in patients concurrently exposed to fever and TLR agonists may contribute to the pathogenesis of sepsis.

Introduction

Engagement of host pattern recognition receptors by pathogen-associated molecular patterns activates a stereotypical immune response that includes fever, leukocytosis, and circulation of acute phase proteins (1). This immune response is critical for containment and eventual clearance of pathogens (1). Certain molecules of host origin, designated alarmins, can activate the same immune response. Alarmins typically perform important intracellular functions, but when secreted through incompletely understood pathways or released from injured or dead cells, alarmins activate the same pattern recognition receptors and the similar immune response as pathogen-associated molecular patterns (2). Several candidate alarmins have been described, including high mobility group box 1 (3), uric acid (4), mitochondrial DNA (5), and extracellular heat shock proteins (Hsps)2 (6, 7). Hsp70 exhibits several properties that suggest it may be particularly important in the pathogenesis of sepsis. Although the role of Hsp70 as an alarmin is still debated (8), levels of Hsp70 in circulating leukocytes and in cell-free serum are elevated in sepsis and are associated with poor outcome (9–11). Extracellular Hsp70 can cause both early immune hyperactivation (7) and subsequent immunosuppression (12, 13), two salient pathogenetic features of severe sepsis (14). Intracellular Hsp70 exerts multiple anti-apoptotic effects, including inhibition of JNK and p38 pathways (15) and recruitment of caspase-9 to the APAF-1-containing apoptosome (16). These effects can protect the structural integrity of cells but also augment the innate immune response by prolonging leukocyte survival (17).

In eukaryotes, Hsps are transcriptionally regulated by the stress-activated transcription factor, heat shock factor 1 (HSF1) (18–20). In mammals, inactive monomeric cytosolic HSF1 is activated through an incremental process (reviewed in Ref. 21). Exposure to stress activates HSF1 homotrimerization, which exposes a cryptic nuclear localization sequence and generates a composite DNA-binding domain that promotes stable binding of the trimer to HSF1-binding element repeats in Hsp promoters. HSF1 trimerization and activation of its transactivation domain are regulated by multiple serine and threonine phosphorylation events. Transcription of Hsps is also influenced by other transcription factors, including STAT-1, STAT-3, and NF-IL-6 (22–24), tonicity enhancer-binding protein and hypoxia-inducible factor 1 (25) and NFκB (26). We previously showed that HSF1 trimerization and Hsp70 transcription were activated in A549 cells by exposure to mild hyperthermia (38.5 °C), that Hsp70 transcription increased as the exposure temperature increased from 38.5 °C to 42 °C, and that increased transcription was associated with additional HSF1 phosphorylation but not additional HSF1 trimerization (27). Hsp70 is expressed from two genes, HSPA1A and HSPA1B, that code for identical 461-amino acid sequences in humans (28).

Endotoxin, killed streptococcus, and other Toll-like receptor (TLR) agonists have been shown to activate Hsp70 expression in vitro (29) and in vivo (30). Because both fever (31) and endotoxemia (32) usually persist for the first several days of sepsis, afflicted patients are often concurrently exposed to these two stimuli for Hsp70 expression. However, to the best of our knowledge, the consequences of concurrent exposure to febrile range temperature (FRT) and TLR agonists on Hsp70 expression and its extracellular release are unknown. The objective of this study was to test the hypothesis that TLR agonists and exposure to FRT synergize to increase expression and extracellular release of Hsps.

We show that exposing mouse RAW 264.7 macrophages (RAW cells) to FRT (39.5 °C) and TLR2 or TLR4 agonists synergize to increase both intracellular expression and extracellular release of Hsp70. We demonstrate that TLR2/4 agonists enhance FRT-induced Hsp70 expression by augmenting the p38-dependent recruitment and/or stabilization of HSF1 to the Hsp70 chromatin in association with phosphorylation of histone H3. We also show that concurrent exposure to febrile range hyperthermia (core temperature, ∼39.5 °C) and intratracheal instillation of LPS induce expression of Hsp70 in mouse lung and accumulation of cell-free Hsp70 in mouse lung lavage. We propose that extracellular release of Hsp70 during sepsis provides positive feedback through its TLR agonist activity that may contribute to the dysregulation of immune function in patients with severe sepsis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents

LPS prepared by trichloroacetic acid extraction from Escherichia coli O111:B4 was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. TLR agonists Pam3Cys and poly(IC) were purchased from InvivoGen (San Diego, CA), and SB203580-hydrochloride and UO126 were obtained from EMD Biosciences (San Diego, CA). Mouse p38α (MAPK14) and negative control scrambled siRNA was obtained from Dharmacon (Thermo Scientific, Lafayette, CO).

Animals

8–10-week-old male outbred CD-1 mice weighing 25–30 g were purchased from Charles River, housed in the Baltimore Veterans Affairs Medical Center animal facility under American Association of Laboratory Animal Care-approved conditions and under the supervision of a full-time veterinarian. All animals were used within 4 weeks of delivery. All protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Maryland and the animal use subcommittee at the Baltimore Veterans Affairs Medical Center.

Hyperthermia and LPS Challenge

The mice were adapted to standard plastic cages for at least 4 days before study. To avoid the influence of diurnal cycling, all of the experiments were started at approximately the same time each day (between 8:00 and 10:00 a.m.). One sentinel mouse/experimental group was implanted with an intraperitoneal telemetric thermistor (Data Safety International, St. Paul, MN; ETA-F10) as we have previously described (33, 34) and allowed to recover for 7 days prior to further experimentation. Exposure to hyperthermia and LPS challenge and core temperature monitoring was performed as described in our previous studies (33, 34). Briefly, cages containing two mice/cage were transferred into modified Air ShieldsTM infant incubators set to 36–37 °C. Normothermic controls were handled and housed in the same way except at standard room temperature (24–25 °C). In conscious unrestrained mice, such exposures maintain core temperatures of 39.5–40 and 36.5–37 °C, respectively (33, 34). For LPS instillation, the mice were briefly anesthetized with isoflurane, and 50 μg of LPS in 50 μl of PBS was administered into the posterior pharynx with the tongue retracted until aspiration was witnessed. Twenty-four hours later, the mice were euthanized by isoflurane inhalation and cervical dislocation, and either lungs were resected and frozen in liquid nitrogen for homogenization in radioimmune precipitation assay buffer or lung lavage was performed with a total of 2 ml of PBS as we have previously described (33, 35, 36).

Cell Culture

RAW cells and the human lung epithelial-like A549 cell lines were maintained in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 50 units/ml penicillin, 50 μg/ml streptomycin, 2 mm l-glutamine, 1 mm sodium pyruvate, 10 mm HEPES buffer (Invitrogen), pH 7.3 (complete RPMI), and 10% defined FBS (Invitrogen) (Complete RPMI). The cells were routinely tested for mycoplasma infection using a commercial assay system (MycoTest; Invitrogen), and new cultures were established monthly from frozen stocks. Cell viability was determined by trypan blue dye exclusion. The cells were treated with agonists and signaling inhibitors as indicated and incubated continuously at 37 °C (normothermia) or 39.5 °C (FRT) or heat-shocked by exposing to 42 °C for 2 h and then returning to 37 °C using automatic CO2 incubators certified to have <0.2 °C temperature variation (Forma, Marietta, OH) and calibrated for each experiment using an electronic thermometer (model 5211; Fluke Instruments, Everett, WA). Supernatants were collected, clarified by centrifugation at 15,000 × g, and analyzed for Hsp70 by ELISA using a DuoSet IC total Hsp70 ELISA kit (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) at the University of Maryland Cytokine Core Laboratory on campus. The assay had a lower detection limit of 156 pg/ml. The cells were washed with PBS and then lysed in radioimmune precipitation assay buffer for immunoblotting.

Immunoblotting

Lung homogenates or cell extracts were prepared in radioimmune precipitation assay buffer containing protease and phosphatase inhibitors (Roche Applied Science), clarified by centrifugation at 15,000 × g, and protein was assayed using the Bradford method (Bio-Rad) using a bovine serum albumin standard curve. Sample containing 20 μg of total protein was resolved by SDS-PAGE and electrostatically transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membrane for immunoblotting. For two-dimensional gel electrophoresis, ∼100 μg of total protein from cell extracts was resuspended in two-dimensional sample buffer (Bio-Rad) and was resolved on the first dimension on a ZOOM® IPG Runner System (Invitrogen) using an immobilized pH 3–10 gradient IPG strip (Invitrogen). The strip was then resolved in the second dimension using a NuPAGE® Novex 4–12% gel (Invitrogen), and the resolved proteins were transferred to PVDF membranes. For immunoblotting, the membranes were blocked with 5% nonfat dry milk in TTBS (25 mm Tris, pH 7.4, 0.5 m NaCl, 0.05% Tween 20) and probed using the following antibodies: Hsp70 (StressGen, Ann Arbor, MI), β-tubulin (Millipore/Chemicon, Bellerica, MA), HSF1, phospho-ERK, phospho-ribosome S6 kinase (RSK), and their total forms from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA) and total and p38α, phospho-p38 and phospho-MAP kinase-activated protein kinase-2 (MK2) were obtained from Cell Signaling (Danvers, MA). Bands were developed using HRP-conjugated appropriate secondary antibody (Santa Cruz) and ECL detection system (Pierce, Thermo Fisher) and quantified using a gel documentation system (Fuji LAS-4000) as described earlier (33, 36, 37).

RNA Extraction and Quantitative Real Time PCR

Total RNA from RAW cells was isolated using a Qiagen kit, contaminating DNA eliminated using DNase I digestion, and RNA was reverse transcribed using oligo(dT) primers and a cDNA synthesis kit according to the manufacturer's protocol (Promega, Madison, WI) as we have previously described (36, 37). Duplicate 25-μl real time PCRs were performed in 96-well plates using a SYBR-Green reaction mix (Bio-Rad) and a Bio-Rad iCycler IQ optical module according to the supplier's protocol with the following forward and reverse primers: GAPDH, 5′-agcctcgtcccgtagacaaaat and 5′-tggcaacaatctccactttgc; and HSPA1A, 5′-ggccagggctggattact and 5′-gcaaccaccatgcaagatta. The data were quantified using the Gene Expression Ct difference method and standardized to levels of the housekeeping gene, GAPDH, using Ct values automatically determined by the thermocycler (36, 37).

Electrophoretic Mobility Shift Assay

Nuclear extracts were prepared according to the method of Schreiber et al. (38) as described earlier (37, 39), and total protein concentration was measured. Double-stranded oligonucleotides containing the consensus HSF1 binding sequence from the human Hsp-70 promoter 5′-GATCTCGGCTGGAATATTCCCGACCTGGCAGCCGA-3′ and the complementary strands were synthesized, annealed, and radiolabeled with [γ-32P]ATP using T4 polynucleotide kinase (Promega) according to the manufacturer's protocol (37, 39). Twenty-microliter EMSA reactions containing 5 μg of nuclear extract, 0.035 pmol of radiolabeled oligonucleotide, 1 μg of poly(IC), 10 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.8, 10% glycerol, 60 mm NaCl, 1 mm EDTA, and 1 mm dithiothreitol were incubated at room temperature for 30 min. For supershift and competetion assays, the reaction mixture was preincubated on ice for 30 min with either 0.5 μg of rabbit IgG or anti-HSF1 antibody (Santa Cruz) or with 10× cold probe or a nonspecific double-stranded oligonucleotide, respectively, prior to the incubation with radiolabeled oligonucleotide probe (37, 39, 40). The DNA-protein complexes were electrophoretically resolved on 4% nondenaturing polyacrylamide gels. The dried gels were analyzed by phosphorimaging (Molecular Dynamics; Sunnyvale, CA) and subsequently exposed to x-ray film.

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation Assays

ChIP assays were performed using a kit from Millipore/Upstate Biotechnology as described previously (36, 37, 39). In brief, RAW cells were treated as indicated, cross-linked using 1% formaldehyde for 15 min, washed with PBS, and collected by centrifugation. The cell pellets were resuspended in SDS lysis buffer and sonicated for three 10-s bursts using a Branson Sonifier 450 (duty cycle and output settings were 30 and 3, respectively). Sonicated cell lysates were diluted 10-fold using ChIP dilution buffer and precleared for 1 h at 4 °C using 80 μl of a 50% salmon sperm DNA-saturated protein A-agarose beads. Cross-linked chromatin was immunoprecipitated with either control IgG or using specific antibodies as indicated at 4 °C overnight, immune complexes were collected, and cross-linked protein-DNA was reverted by incubating at 65 °C for 4 h. DNA was extracted and used as template for real time PCR as described earlier (36, 41). Primer pairs spanning the HSF1-binding site on the HSPA1A promoter (forward 5′-agcaccagcacttccccaca and reverse 5′-ccgctgggccaatcagcgag) were used, and the fold enrichment with specific antibody against nonspecific antibody was determined as described previously (36, 41).

siRNA Transfections

siRNA-targeted against mouse p38α (MAPK14) and negative control scrambled siRNA was obtained from Dharmacon (Thermo, Lafayette, CO). RAW cells (2 × 106) were transfected with the RNA duplexes using the Amaxa Nucleofector kit V and Nucleofector 2b device (Lonza, Allendale, NJ), and the cells were plated in 12-well plates at 250,000 cells/well. 48 h after transfection the cells were either immunoblotted for p38α expression or stimulated with or without LPS as indicated and analyzed for Hsp70 expression in cell lysates by immunoblotting.

Cytotoxicity Assay

The cytotoxic effect of hyperthermia and LPS exposure was analyzed by measuring lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) release using the CytoTox 96 nonradioactive cytotoxicity assay kit (Promega).

Statistical Analysis

The data are displayed as the means ± S.E. Differences between two groups were analyzed by unpaired Student's t test and among multiple groups was analyzed by applying a Tukey-Kramer honestly significant difference test to a one-way analysis of variance. Differences of p < 0.05 were considered significant.

RESULTS

LPS and Other Proinflammatory Agonists Enhance Hyperthermia-induced Hsp70 Expression in Primary and Tissue Culture Cells

In RAW cells exposed to FRT for 4 h, Hsp70 mRNA levels were 14-fold greater than cells incubated at 37 °C. Treatment with 100 ng/ml LPS did not increase Hsp70 mRNA levels in RAW cells incubated at 37 °C but, when combined with FRT, increased Hsp70 mRNA levels ∼50-fold compared with untreated 37 °C cells (Fig. 1A). Exposing RAW cells to FRT for 6 h stimulated a modest increase in cell-associated Hsp70 protein levels but much less compared with cells exposed to HS (42 °C for 2 h followed by 4 h of recovery at 37 °C (compare lane 2 in Fig. 1, B and C). Stimulating RAW cells with LPS or an agonist for TLR1/2 (Pam3cys) stimulated a profound increase in Hsp70 protein in both FRT- and HS-exposed RAW cells. The TLR3 agonist, poly(IC), exerted similar effects in FRT- and HS-exposed RAW cells, albeit of lesser magnitude than LPS and Pam 3cys. In human lung epithelial-like A549 cells, treatment with IL-1β enhanced Hsp70 expression in cells incubated at 39.5 °C but not 37 °C (Fig. 1D).

FIGURE 1.

Proinflammatory agonists augment hyperthermia-induced Hsp70 expression in RAW cells. A, RAW cells were incubated with or without 100 ng/ml LPS at 37 °C or at 39.5 °C for 2 or 4 h and Hsp70 mRNA was measured by real time PCR, expressed as a ratio to GAPDH levels, and standardized to untreated 37 °C base-line levels. The results are the means ± S.E. of four experiments. * and † denote p < 0.05 versus 37 °C controls with no LPS and 39.5 °C cells with no LPS at the same time point, respectively. B and C, RAW cells were incubated with 100 ng/ml LPS, 0.5 μg/ml Pam3CSK4 (Pam3C), or 12.5 μg/ml poly(IC) (pI:C) at 39.5 °C for 6 h (B) or were exposed to HS at 42 °C for 2 h, recovered at 37 °C for 4 h (C), lysed, and immunoblotted for Hsp70 and β-tubulin. Lane 1 is untreated 37 °C control. D, A549 cells were incubated with or without 1 ng/ml IL-1β at 37 or 39.5 °C for 6 h, lysed, and immunoblotted for Hsp70 and β-tubulin. Immunoblots are representative of four independent experiments.

Effect of TLR Agonists on HSF1 Phosphorylation

We analyzed whether TLR agonists stimulated post-translational modification of HSF1 protein by treating RAW cells with TLR agonists and assessing electrophoretic mobility of HSF1 on immunoblots (Fig. 2A). A decrease in HSF1 band mobility was evident within 5 min of LPS treatment, persisted for 30 min, returned to base line by 60 min, and remained at base-line levels for the remainder of the 24-h incubation (data or not shown). To confirm that the mobility shift was due to HSF1 phosphorylation, we incubated LPS-treated RAW cell extracts with shrimp alkaline phosphatase for 30 min, which reduced the shift in HSF1 toward base-line levels exhibited by untreated control cells (Fig. 2B). Additionally, two-dimensional gel analysis and HSF1 immunoblotting of cell extracts from LPS-treated RAW cells showed a mobility shift toward lower pH as is typical of protein phosphorylation (Fig. 2C). To determine whether activating HSF1 phosphorylation was a property unique to LPS/TLR4 or was shared by agonists of other TLRs, we analyzed HSF1 mobility in 37 °C RAW cells stimulated for 30 min with agonists for TLR2 and 3 in the presence or absence of polymyxin B to exclude contamination with LPS. As expected, treating RAW cells with LPS reduced HSF1 mobility, and this effect was blocked by co-treatment with polymyxin B (Fig. 2D). Treatment with the TLR1/2 agonist, Pam3CSK4, caused a similar decrease in HSF1 mobility, but the effect persisted in the presence of polymyxin B, excluding a contribution from contaminating endotoxin. In contrast, the TLR3 agonist, poly(IC), did not stimulate a detectable shift in HSF1 mobility.

FIGURE 2.

Proinflammatory agonists induce HSF1 phosphorylation in RAW cells. A, RAW cells were incubated with 100 ng/ml LPS at 37 °C for the indicated time, lysed, and immunoblotted for HSF1 to analyze electrophoretic mobility shift. B and C, lysates from RAW cells exposed to LPS for 30 min were incubated with or without (mock) shrimp alkaline phosphatase (SAP) for 30 min and then immunoblotted for HSF1 (B) or were resolved by two-dimensional gel electrophoresis using a pH 3–10 IPG strip for the first dimension and a 10% SDS gel for the second dimension and then immunoblotted for HSF1 (C). D, RAW cells were treated with 100 ng/ml LPS, 12.5 ng/ml poly(IC) (pI:C), or 0.5 μg/ml Pam3CSK4 (Pam3C) with or without 20 μg/ml polymyxin B, and lysates were immunoblotted for HSF1. Lane 1 is untreated 37 °C control. Immunoblots are representative of four independent experiments.

Effect of Co-exposure to LPS and FRT on in Vitro HSF1-DNA Binding Activity and Recruitment of HSF1 to the Hsp70 Chromatin in RAW Cells

We analyzed whether treatment with LPS enhanced HSF1 DNA binding activity in RAW cells at 37 and 39.5 °C. RAW cells were incubated with or without 100 ng/ml LPS at 37 or 39.5 °C for 30 or 60 min, and nuclear extracts were analyzed for DNA binding-capable HSF1 trimers by EMSA using a consensus HSF1 binding sequence (36, 37, 39). As expected, DNA binding-capable HSF1 was detectable in untreated RAW cells incubated at 39.5 °C but not in cells incubated at 37 °C (Fig. 3A). Competition with cold probe and supershift with anti-HSF1 antibody established the identified band to be HSF1 (Fig. 3B). LPS treatment did not increase nuclear levels of DNA-binding HSF1 at either temperature. We used a ChIP assay to determine whether treatment with LPS stimulated specific recruitment of HSF1 to the HSPA1A promoter. As expected, incubating RAW cells for 60 min increased HSF1 recruitment to the HSF1 chromatin by ∼6-fold (p < 0.05) compared with 37 °C control cells, but surprisingly, concurrent treatment with LPS stimulated an additional >2-fold increase in HSF1 recruitment to Hsp70 chromatin in RAW cells incubated at 39.5 °C (p < 0.05) (Fig. 3C).

FIGURE 3.

LPS and FRT synergistically induce HSF1 recruitment to the HSPA1A promoter. A, RAW cells were incubated at 37 or 39.5 °C with or without 100 ng/ml LPS, and nuclear extracts were analyzed for in vitro HSF1 DNA binding activity by EMSA. Lane 1 is probe alone. Lane 2 is nuclear extract from untreated 37 °C RAW cells. B, for supershift and competition assays nuclear extracts from 39.5 °C exposed cells in EMSA reaction were preincubated for 30 min on ice before addition of the radiolabeled probe with the following: none (lane 1), IgG (lane 2), supershifting anti-HSF1 antibody (lane 3), nonspecific double-stranded oligonucleotide probe (lane 4), and 10-fold excess of unlabeled HSF1 probe (lane 5). C, RAW cells were incubated at 37 or 39.5 °C with or without 100 ng/ml LPS for 60 min and formaldehyde-cross-linked, and HSF1 ChIP assay was performed. DNA was quantified by real time PCR using specific primers spanning the HSF1-binding site on the HSPA1A gene and presented as fold enrichment compared with control IgG immunoprecipitates. The values are the means ± S.E. (n = 4). * and † denote p < 0.05 versus 37 and 39.5 °C cells without LPS.

LPS Treatment Increased Histone H3 Phosphorylation at the Hsp70 Chromatin in RAW Cells at FRT

Because treating RAW cells with LPS increased HSF1 recruitment to Hsp70 chromatin without increasing global nuclear levels of activated HSF1, we asked whether LPS treatment induces chromatin modification on the Hsp70 promoter that might increase its accessibility to HSF1. Because previous studies showed that exposure to heat shock maximally stimulated acetylation of histone H4 associated with the mouse Hsp70 promoter (42), we considered other potential chromatin modifications by which LPS augments Hsp70 expression. Treatment with arsenic activates Hsp70 transcription by stimulating both histone H4 acetylation and histone H3 phosphorylation, whereas exposure to heat shock alone only stimulated H4 acetylation (42). We used a ChIP assay to analyze the phosphorylation of histone H3 Ser10 on Hsp70 promoter in RAW cells incubated with or without LPS at 37 or 39.5 °C (Fig. 4A). Histone H3 phosphorylation on the HSF1-binding region of HSPA1A was similar in RAW cells incubated at 37 °C with or without LPS or at 39.5 °C without LPS for 60 min. However, co-exposure to 39.5 °C and LPS stimulated a 4.2-fold increase in histone H3 phosphorylation without any apparent change in total histone H3 enrichment in the same region of the Hsp70 promoter (Fig. 4B). Immunoblotting for phosphorylated forms of p38 and ERK showed that LPS treatment of RAW cells stimulated both p38 and ERK activation (Fig. 4C). We then used pharmacologic inhibitors of ERK (U0126) and p38 (SB203580) to examine the effects of inhibiting these pathways. First, we confirmed that the inhibitors effectively blocked the appropriate signaling pathway by pretreating RAW cells with U0126 or SB203580, then stimulating with LPS for 30 min at 39.5 °C, and immunoblotting for the ERK and p38 substrates, phosphorylated RSK, and MK2 (Fig. 4D). Treatment with U0126 eliminated the phosphorylated RSK2 but had no effect on MK2. MK2 phosphorylation as indicated by both the intensity of the phosphorylated MK2 band and the reduced electrophoretic mobility of both the phosphorylated and total MK2 bands was reduced by SB203580 treatment, whereas RSK phosphorylation was unaffected. To analyze the effects of p38 and ERK pathway inhibition, we pretreated RAW cells with the inhibitors or Me2SO (vehicle) for 30 min and then stimulated the cells with LPS at 39.5 °C for 2 or 6 h for analysis of RNA and protein, respectively. Treatment with SB203580 significantly blocked the increase in Hsp70 mRNA (Fig. 4E) and protein generation (Fig. 4F) in comparison with cells pretreated with Me2SO in cells co-exposed to LPS at FRH. Although LPS also activated ERK (Fig. 4C), treatment with the ERK inhibitor, U0126, did not block incremental Hsp70 expression in RAW cells co-treated with LPS and FRT (Fig. 4, E and F). Furthermore, a ChIP assay for phosphorylated histone H3 in the presence of SB203580 showed that p38 inhibition significantly reduced histone H3 phosphorylation in LPS-treated RAW cells at FRT (Fig. 4G).

FIGURE 4.

LPS and FRT synergistically increase histone H3 phosphorylation and recruitment to HSPA1A chromatin. A and B, RAW cells were incubated with or without 100 ng/ml LPS at 37 or 39.5 °C for 1 h and cross-linked with formaldehyde, and ChIP assay was performed using anti-phospho-histone H3 (Ser10) (A) or anti-histone H3 (B) antibody. Immunoprecipitated DNA was quantified by real time PCR using specific primers spanning the HSF1-binding site on the HSPA1A gene, and the fold enrichment compared with control IgG immunoprecipitates was calculated. The values are the means ± S.E. (n = 4). * and † denote p < 0.05 versus untreated 37 °C cells and untreated 39.5 °C cells, respectively. C, RAW cells were incubated at 39.5 °C with 100 ng/ml LPS for the indicated time, and lysates were immunoblotted for phospho-p38 (p) and total p38 (t) and ERK. Lane 1 is untreated 37 °C control cells. D, RAW cells were preincubated with ERK (U0126) or p38 (SB203580; SB) inhibitors for 30 min and then with 100 ng/ml LPS for 30 min at 39.5 °C, and the lysates were immunoblotted for phosphorylated (p) and total (t) RSK and MK2. Lane 1 is from untreated 37 °C control cells. Immunoblots are representative of four independent experiments. E, RAW cells were pretreated for 30 min at 37 °C with 10 μm UO126 or SB203580-hydrochloride (SB) or dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) and then stimulated with 100 ng/ml LPS for 2 h at 39.5 °C, and Hsp70 mRNA levels were measured by real time PCR and expressed as fold change versus untreated 37 °C control. F, RAW cells were pretreated with inhibitors as in C and then incubated with 100 ng/ml LPS at 37 or 39.5 °C for 6 h, and lysates were immunoblotted for Hsp70 and β-tubulin, quantified, and expressed as the Hsp70:β-tubulin ratio. The values are the means ± S.E. (n = 4). *, †, and ‡ denote p < 0.05 versus untreated (without LPS) 39.5 °C control, cells treated with LPS and U0126 or Me2SO, and similarly treated 37 °C cells. G, RAW cells were pretreated with or without 10 μm SB203580 hydrochloride for 30 min at 37 °C, and phospho-histone H3 ChIP assay was performed as describe above. * and † denote p < 0.05 versus untreated 37 °C and 39.5 °C cells without SB203580, respectively.

To further analyze the role of p38, we used siRNA to knockdown p38α. RAW cells were transfected with either scrambled negative control siRNA of p38α siRNA, and after 48 h of transfection, the cells were immunoblotted for p38α expression to confirm depletion of p38α protein levels (Fig. 5A). When the siRNA-transfected cells were stimulated with or without LPS at FRT, Hsp70 expression was significantly increased in control siRNA-transfected cells but not in cells transfected with 50 or 100 pm p38α siRNA (Fig. 5, B and C).

FIGURE 5.

p38α knockdown reduces LPS-activated Hsp70 expression at FRT. RAW cells were transfected with scrambled negative control siRNA (scramb) or 50 or 100 pmol of p38α (MAPK14) siRNA and 48 h later either immunoblotted for p38α (A) or treated with 100 ng/ml LPS at 39.5 °C for 6 h and immunoblotted for Hsp70 and β-tubulin (B). Ratios from four independent experiments were plotted (C). The data are presented as the means ± S.E. *, p < 0.05.

LPS Challenge Increased Release of Extracellular Hsp70

To begin to understand the consequences of the enhanced Hsp70 expression following co-exposure to LPS and FRT, we also analyzed the effect of LPS and hyperthermia on release of Hsp70 into the extracellular microenvironment where it can exert proinflammatory TLR4 agonist activity (7, 43). RAW cells were incubated with 0, 100, or 1000 ng/ml LPS at 37 or 39.5 °C or were exposed to a concurrent 2-h 42 °C HS, and culture supernatants were collected after 6 and 24 h and analyzed for Hsp70 by ELISA. In the absence of LPS, incubation at 39.5 °C for 6 or 24 h failed to stimulate Hsp70 release, but cells stimulated with LPS at 39.5 °C significantly increased Hsp70 release at both doses of LPS (Fig. 6, A and B). In contrast, RAW cells exposed to HS released substantially more Hsp70 even in the absence of LPS treatment (Fig. 6, C and D), but treating with LPS further increased the release of Hsp70 in the culture supernatants. To distinguish between active Hsp70 secretion and leak from dead or dying cells, we also measured LDH in the culture supernatant. Accumulation of extracellular Hsp70 was accompanied by LDH release in cells exposed to HS but occurred without detectable LDH release in cells treated with LPS at 39.5 °C (Fig. 6E).

FIGURE 6.

LPS synergizes with FRT and HS for extracellular release of Hsp70 from RAW cells. RAW cells were incubated with 0, 100, or 1000 ng/ml LPS at 37 or 39.5 °C for 6 h (A and E) or 24 h (B) or exposed to a 42 °C HS for 2 h and then incubated at 37 °C for an additional 4 h (C and E) or 22 h (D). Cell culture supernatants were collected and cleared by centrifugation, and Hsp70 was quantified by ELISA and presented as pg/ml (A–D), or LDH activity was measured (6 h) and presented as A490 of the reaction product (E). The data are presented as the means ± S.E. (n = 4). * and † denote p < 0.05 versus similarly treated 37 °C cells and 39.5 °C cells with no LPS or HS-exposed cells, respectively.

Intratracheal LPS Challenge Enhanced Hsp70 Expression in Lung of Hyperthermic Mice

As we have previously shown (33, 34), mice housed at 36–37 °C ambient temperature increased their core temperature by ∼2.5 °C to 39–40 °C and maintained the same activity level and circadian temperature pattern as in normothermic mice (Fig. 7A). Immunoblotting of lung homogenates showed ∼110% increase in mice exposed to hyperthermia and a further 68% increase when hyperthermic mice were challenged with intratracheal LPS (Fig. 7B). However, LPS challenge failed to stimulate an increase in lung-associated Hsp70 protein levels in normothermic mice. To determine whether LPS exerts similar effects on Hsp70 release in vivo, we used ELISA to analyze Hsp70 levels in cell-free lung lavage from mice exposed to hyperthermia and intratracheal LPS instillation alone and in combination. Neither LPS instillation nor hyperthermia alone stimulated significant changes in lung lavage Hsp70 levels, but the combination of LPS instillation and hyperthermia exposure for 24 h stimulated over a 2-fold increase in Hsp70 concentration compared with untreated normothermic mice (Fig. 7C).

FIGURE 7.

LPS augments hyperthermia-induced Hsp70 expression in mouse lungs. A, mice implanted with intraperitoneal thermistors were housed at either 25 °C (normothermic, NT) or 36–37 °C (hyperthermic, HT) ambient temperature and core temperature measured every 20 s. The mean temperatures for each 2-h period were calculated, and the means ± S.E. are shown (n = 4); the two groups were different with p < 0.05 by multifactorial analysis of variance. B and C, mice were intratracheally instilled with LPS or sterile PBS (control) and housed under normothermic or hyperthermic conditions for 24 h. The lungs were excised, and the homogenates were immunoblotted for Hsp70 and expressed as a ratio to β-actin (B), or lungs were lavaged and Hsp70 quantified by ELISA (C). The data are the means ± S.E. (n = 4). *, †, and § denote p < 0.05 versus PBS-treated NT controls, PBS-treated HT mice, and LPS-treated NT mice, respectively.

DISCUSSION

We have previously shown that exposure to FRT (38.5–39.5 °C) is sufficient to activate HSF1 and induce expression of Hsp70 but at much lower levels than what occurs in response to temperatures above 42 °C (27, 40). In the current study, we have extended these findings by showing that stimulating TLR-dependent signaling pathways while exposing cells to FRT or HS greatly augments Hsp70 expression and its release into the extracellular microenvironment in both in vitro cell culture and in vivo in an intratracheal LPS-induced acute lung injury model.

We used RAW 264.7, an Abelson murine leukemia virus-transformed macrophage cell line that exhibits macrophage morphology and function and expresses all TLRs except TLR5 (44). We showed that exposing RAW cells to 39.5 °C for 2–4 h increased Hsp70 mRNA levels 7–15-fold. In an earlier study, we found that exposing RAW cells to 40 °C failed to activated Hsp70 mRNA expression (45), but the cells were only heated for 30 min in the previous study. The results of the two studies are consistent with our observation that Hsp70 induction at less extreme hyperthermia requires longer exposure time (27). In the present study, we showed that co-treating RAW cells with TLR4 (LPS) or TLR2/1 (Pam3cys) agonists greatly augmented Hsp70 expression in FRT-exposed RAW cells. The TLR3 agonist, poly(IC), exerted a smaller effect on Hsp70 expression. Treating A549 human lung epithelial-like cells with IL-1β stimulated a similar increase in Hsp70 expression at FRT. TLR2 and 4 and the IL-1 receptor share the same MyD88-dependent signaling pathway, whereas TLR3 activates a distinct, MyD88-independent signaling pathway (46, 47). Both signaling pathways activate NFκB and MAP kinases, although activation of these signaling elements is indirect and delayed in MyD88-independent signaling, which may be responsible for the lower Hsp70 inducing activity of poly(IC).

Because the transcriptional activation of Hsp genes is regulated by the stress-activated transcription factor, HSF1, which itself is regulated by post-translational modification including phosphorylation (18, 48, 49), we analyzed whether the TLR agonists stimulated post-translational modification of HSF1. We found that RAW cells stimulated with TLR1/2 and TLR 4 agonists at 37 °C caused a distinct shift in HSF1 mobility on SDS and on two-dimensional gels (Fig. 2), consistent with an increase in HSF1 phosphorylation (40, 48, 50). However, the apparent phosphorylation of HSF1 by LPS in 37 °C RAW cell cultures was transient, lasting only 30 min, and was not associated with either HSF1 activation as assessed by EMSA (Fig. 3a) or induction of Hsp70 expression (Fig. 1). Analysis of the interaction of HSF1 with the Hsp70 promoter in vivo by ChIP assay demonstrated that LPS treatment doubled the recruitment of HSF1 to the Hsp70 chromatin in FRT-exposed RAW cells (Fig. 3C). Collectively, these results suggest that TLR agonists may enhance Hsp70 expression through specific effects on the HPS70 gene rather than through global modification of HSF1.

Transcriptional activation of Hsp70 is critically regulated by chromatin architecture and histone modifications (51–55), some of which are mediated through activation of MAP kinase cascades. The MAP kinase, p38, has been implicated in activation of Hsp gene transcription activated by cadmium and arsenic (42, 56) but not by HS or low pH (42, 56, 57). In fact, Thomson et al. (42) showed that arsenic treatment increased p38 activation, histone phosphorylation, and enrichment of phospho-histone H3 at the Hsp70 chromatin and that arsenic-induced histone H3 phosphorylation and Hsp70 transcription was sensitive to p38 inhibitors. LPS and other TLR agonists are known to activate MAP kinase signaling, and we have earlier shown that p38 MAPK is activated by LPS to comparable levels at 37 and 39.5 °C (36). ChIP assays using an antibody that recognizes histone H3 phosphorylated on Ser10 showed that co-treatment with LPS and FRT increased enrichment of phospho-histone H3 on the HSF1-binding region of the HSPA1A promoter (Fig. 4A) coincident with recruitment of HSF1 to the same region (Fig. 3C). Phosphorylation of Ser10 on histone H3 was the same modification shown to accompany the increase in arsenic-induced Hsp70 expression in NIH 3T3 fibroblasts (42). ERK and p38 are each activated following LPS treatment in RAW cells (36), and both kinases can stimulate phosphorylation of histone H3 through activation of MSK1 and 2 (58, 59). Park et al. (60) showed that treating RAW cells with LPS also stimulates histone H3 phosphorylation on cyclooxygenase 2-associated chromatin and activates cyclooxygenase expression, both of which were blocked by the p38 inhibitor SB203580. Histone H3 phosphorylation on Hsp70 in arsenic-treated NIH 3T3 fibroblasts was also associated with p38 activation and blocked by SB203580 (42). We found that pretreating RAW cells with the p38 MAP kinase inhibitor, SB203580, reduced the effect of LPS and FRT on HSPA1A-associated histone H3 phosphorylation (Fig. 4G) and Hsp70 mRNA and protein (Fig. 4, E and F)) expression. To further analyze the role of p38-mediated signaling, we use siRNA to knockdown p38α. Because SB203580 is known to only inhibit p38α and β isoforms and because p38α is the major isoform that is activated in inflammatory cells (61), we focused first on p38α. Interestingly, p38α depletion reduced LPS-activated Hsp70 expression in cells exposed to FRT (Fig. 5, B and C). These results suggest that p38 (primarily p38α) or one of its downstream targets participates in LPS-induced phosphorylation of histone H3 on the Hsp70 chromatin, recruitment of HSF1, and transcriptional activation of Hsp70. However, we have not excluded the contribution of additional HSF1 and histone modifications including HSF1 sumoylation (62, 63) and histone acetylation and methylation (42, 49, 54, 64).

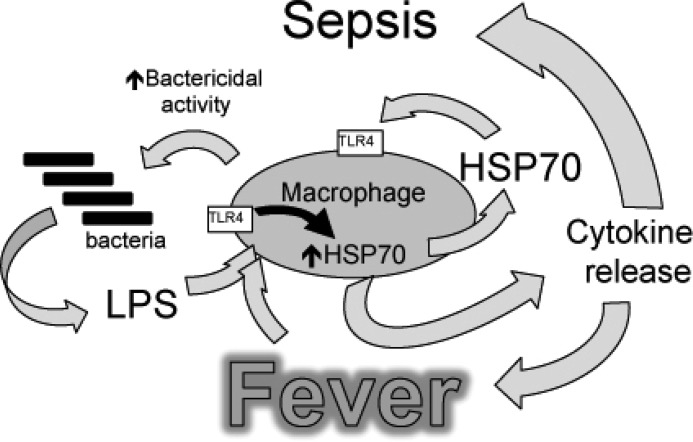

Considering that co-exposure to TLR agonists and FRT is likely to occur in human sepsis (31, 32), the results of this study suggest a possible positive feedback amplification pathway that may contribute to severe sepsis (Fig. 8). In addition to the established role as cytoprotective molecules and chaperone proteins, Hsps, and Hsp70 in particular, have more recently been detected in the extracellular milieu and have been appreciated as potential alarmins that signal through TLRs (43, 65, 66). Although there was an earlier debate about whether the TLR agonist activity of Hsp70 was the result of its contamination by bacterial products (8, 67, 68), use of recombinant Hsp70 isolated from insect cells, nonrecombinant Hsp70, boiled, or polymyxin B-treated Hsp70 have provided convincing evidence that Hsp70 has intrinsic TLR agonist activity and can activate macrophages, monocytes, dendritic cells, and natural killer cells (12, 65, 69–75). Clinical studies show that Hsp70 levels in circulating leukocytes and serum are elevated in sepsis and are associated with poor outcome (9–11). Moreover, studies with human immune cells show that extracellular Hsp70 can cause both early immune hyperactivation (7) and delayed immunosuppression (12, 13), two salient pathogenetic features of severe sepsis (14). If LPS and fever stimulate expression and extracellular release of Hsp70, the Hsp70 itself may synergize with fever to sustain the proinflammatory state through its TLR4 agonist activity (7) and stimulate additional Hsp70 expression. In addition, persistent exposure to Hsp70 may cause cross-tolerance to other TLR agonists, including endotoxin (12, 13), which may increase susceptibility to secondary infections. The association of elevated serum Hsp70 levels and mortality in sepsis is consistent with such a model.

FIGURE 8.

Model of how fever, LPS, and Hsp70 interact to cause sepsis. Proposed model of sepsis in which LPS and fever initiate a positive feedback pathway through enhanced Hsp70 expression and release and subsequent increased TLR4 activation, Hsp70 expression, and proinflammatory cytokine release.

In summary, we have shown that co-exposure to TLR agonists and febrile range hyperthermia greatly augments Hsp70 synthesis and extracellular release at least in part through the increased recruitment of HSF1 to the Hsp70 chromatin following p38-dependent phosphorylation of associated histone H3. The results suggest that the TLR agonist activity of extracellular Hsp70 may worsen sepsis and suggest a potential benefit of maintaining normothermia in patients with sepsis. However, the ultimate effect of fever suppression in sepsis awaits empiric evidence from clinical trials.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grants GM069431 (to I. S. S.) and GM066855, HL69057, and HL085256 (to J. D. H.). This work was also supported by Veterans Affairs Merit Review grants (to I. S. S. and J. D. H.).

- Hsp and HSP

- heat shock protein

- FRT

- febrile range temperature

- HSF

- heat shock factor

- TLR

- Toll-like receptor

- HS

- heat shock

- RSK

- ribosome S6 kinase

- MK

- MAP kinase-activated protein kinase

- LDH

- lactate dehydrogenase.

REFERENCES

- 1. Sriskandan S., Altmann D. M. (2008) The immunology of sepsis. J. Pathol. 214, 211–223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bianchi M. E. (2007) DAMPs, PAMPs and alarmins. All we need to know about danger. J. Leukocyte Biol. 81, 1–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Andersson U., Wang H., Palmblad K., Aveberger A. C., Bloom O., Erlandsson-Harris H., Janson A., Kokkola R., Zhang M., Yang H., Tracey K. J. (2000) High mobility group 1 protein (HMG-1) stimulates proinflammatory cytokine synthesis in human monocytes. J. Exp. Med. 192, 565–570 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Shi Y., Evans J. E., Rock K. L. (2003) Molecular identification of a danger signal that alerts the immune system to dying cells. Nature 425, 516–521 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Zhang Q., Raoof M., Chen Y., Sumi Y., Sursal T., Junger W., Brohi K., Itagaki K., Hauser C. J. (2010) Circulating mitochondrial DAMPs cause inflammatory responses to injury. Nature 464, 104–107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ohashi K., Burkart V., Flohé S., Kolb H. (2000) Cutting edge. Heat shock protein 60 is a putative endogenous ligand of the Toll-like receptor-4 complex. J. Immunol. 164, 558–561 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Asea A., Rehli M., Kabingu E., Boch J. A., Bare O., Auron P. E., Stevenson M. A., Calderwood S. K. (2002) Novel signal transduction pathway utilized by extracellular HSP70. Role of Toll-like receptor (TLR) 2 and TLR4. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 15028–15034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. van Eden W., Spiering R., Broere F., van der Zee R. (2012) A case of mistaken identity. HSPs are no DAMPs but DAMPERs. Cell Stress Chaperones 17, 281–292 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Gelain D. P., de Bittencourt Pasquali M. A., Comim M. C., Grunwald M. S., Ritter C., Tomasi C. D., Alves S. C., Quevedo J., Dal-Pizzol F., Moreira J. C. (2011) Serum heat shock protein 70 levels, oxidant status, and mortality in sepsis. Shock 35, 466–470 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Wheeler D. S., Fisher L. E., Jr., Catravas J. D., Jacobs B. R., Carcillo J. A., Wong H. R. (2005) Extracellular Hsp70 levels in children with septic shock. Pediatr. Crit. Care Med. 6, 308–311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hashiguchi N., Ogura H., Tanaka H., Koh T., Nakamori Y., Noborio M., Shiozaki T., Nishino M., Kuwagata Y., Shimazu T., Sugimoto H. (2001) Enhanced expression of heat shock proteins in activated polymorphonuclear leukocytes in patients with sepsis. J. Trauma 51, 1104–1109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Aneja R., Odoms K., Dunsmore K., Shanley T. P., Wong H. R. (2006) Extracellular heat shock protein-70 induces endotoxin tolerance in THP-1 cells. J. Immunol. 177, 7184–7192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Abboud P. A., Lahni P. M., Page K., Giuliano J. S., Jr., Harmon K., Dunsmore K. E., Wong H. R., Wheeler D. S. (2008) The role of endogenously produced extracellular Hsp72 in mononuclear cell reprogramming. Shock 30, 285–292 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Rittirsch D., Flierl M. A., Ward P. A. (2008) Harmful molecular mechanisms in sepsis. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 8, 776–787 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Park H. S., Cho S. G., Kim C. K., Hwang H. S., Noh K. T., Kim M. S., Huh S. H., Kim M. J., Ryoo K., Kim E. K., Kang W. J., Lee J. S., Seo J. S., Ko Y. G., Kim S., Choi E. J. (2002) Heat shock protein hsp72 is a negative regulator of apoptosis signal-regulating kinase 1. Mol. Cell Biol. 22, 7721–7730 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Beere H. M., Wolf B. B., Cain K., Mosser D. D., Mahboubi A., Kuwana T., Tailor P., Morimoto R. I., Cohen G. M., Green D. R. (2000) Heat-shock protein 70 inhibits apoptosis by preventing recruitment of procaspase-9 to the Apaf-1 apoptosome. Nat. Cell Biol. 2, 469–475 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Oehler R., Pusch E., Zellner M., Dungel P., Hergovics N., Homoncik M., Eliasen M. M., Brabec M., Roth E. (2001) Cell type-specific variations in the induction of Hsp70 in human leukocytes by fever like whole body hyperthermia. Cell Stress Chaperones 6, 306–315 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Pirkkala L., Nykänen P., Sistonen L. (2001) Roles of the heat shock transcription factors in regulation of the heat shock response and beyond. FASEB J. 15, 1118–1131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Morimoto R. I. (1993) Cells in stress. Transcriptional activation of heat shock genes. Science 259, 1409–1410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Christians E. S., Yan L. J., Benjamin I. J. (2002) Heat shock factor 1 and heat shock proteins. Critical partners in protection against acute cell injury. Crit. Care Med 30, S43–50 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Singh I. S., Shah N. G., Almutairy E. A., Hasday J. D. (2009) Role of HSF1 in infectious disease, in Prokaryotic and Eukaryotic Heat Shock Proteins in Infectious Disease (Pockley A. G., Santoro M. G., Calderwood S. K., ed.) pp. 1–31, Springer-Verlag New York Inc., New York [Google Scholar]

- 22. Stephanou A., Isenberg D. A., Nakajima K., Latchman D. S. (1999) Signal transducer and activator of transcription-1 and heat shock factor-1 interact and activate the transcription of the Hsp-70 and Hsp-90β gene promoters. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 1723–1728 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Stephanou A., Isenberg D. A., Akira S., Kishimoto T., Latchman D. S. (1998) The nuclear factor interleukin-6 (NF-IL6) and signal transducer and activator of transcription-3 (STAT-3) signalling pathways co-operate to mediate the activation of the hsp90β gene by interleukin-6 but have opposite effects on its inducibility by heat shock. Biochem. J. 330, 189–195 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Magalhães F. C., Passos R. L., Fonseca M. A., Oliveira K. P., Ferreira-Júnior J. B., Martini A. R., Lima M. R., Guimarães J. B., Baraúna V. G., Silami-Garcia E., Rodrigues L. O. (2010) Thermoregulatory efficiency is increased after heat acclimation in tropical natives. J. Physiol. Anthropol. 29, 1–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Gogate S. S., Fujita N., Skubutyte R., Shapiro I. M., Risbud M. V. (2012) Tonicity enhancer binding protein (TonEBP) and hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF) coordinate heat shock protein 70 (Hsp70) expression in hypoxic nucleus pulposus cells. Role of Hsp70 in HIF-1α degradation. J. Bone Miner Res. 27, 1106–1117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Wilhide M. E., Tranter M., Ren X., Chen J., Sartor M. A., Medvedovic M., Jones W. K. (2011) Identification of a NF-κB cardioprotective gene program. NF-κB regulation of Hsp70.1 contributes to cardioprotection after permanent coronary occlusion. J. Mol. Cell Cardiol. 51, 82–89 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Tulapurkar M. E., Asiegbu B. E., Singh I. S., Hasday J. D. (2009) Hyperthermia in the febrile range induces HSP72 expression proportional to exposure temperature but not to HSF-1 DNA-binding activity in human lung epithelial A549 cells. Cell Stress Chaperones 14, 499–508 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Milner C. M., Campbell R. D. (1990) Structure and expression of the three MHC-linked HSP70 genes. Immunogenetics 32, 242–251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Fincato G., Polentarutti N., Sica A., Mantovani A., Colotta F. (1991) Expression of a heat-inducible gene of the HSP70 family in human myelomonocytic cells. Regulation by bacterial products and cytokines. Blood 77, 579–586 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Zhang Y. H., Takahashi K., Jiang G. Z., Zhang X. M., Kawai M., Fukada M., Yokochi T. (1994) In vivo production of heat shock protein in mouse peritoneal macrophages by administration of lipopolysaccharide. Infect. Immun. 62, 4140–4144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Cunha B. A. (1999) Fever in the intensive care unit. Intensive Care Med. 25, 648–651 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Guidet B., Barakett V., Vassal T., Petit J. C., Offenstadt G. (1994) Endotoxemia and bacteremia in patients with sepsis syndrome in the intensive care unit. Chest 106, 1194–1201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Tulapurkar M. E., Hasday J. D., Singh I. S. (2011) Prolonged exposure to hyperthermic stress augments neutrophil recruitment to lung during the post-exposure recovery period. Int. J. Hyperthermia 27, 717–725 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Sareh H., Tulapurkar M. E., Shah N. G., Singh I. S., Hasday J. D. (2011) Response of mice to continuous 5-day passive hyperthermia resembles human heat acclimation. Cell Stress Chaperones 16, 297–307 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Rice P., Martin E., He J. R., Frank M., DeTolla L., Hester L., O'Neill T., Manka C., Benjamin I., Nagarsekar A., Singh I., Hasday J. D. (2005) Febrile-range hyperthermia augments neutrophil accumulation and enhances lung injury in experimental gram-negative bacterial pneumonia. J. Immunol. 174, 3676–3685 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Cooper Z. A., Ghosh A., Gupta A., Maity T., Benjamin I. J., Vogel S. N., Hasday J. D., Singh I. S. (2010) Febrile-range temperature modifies cytokine gene expression in LPS-stimulated macrophages by differentially modifying NF-κB recruitment to cytokine gene promoters. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 298, C171–C181 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Singh I. S., Gupta A., Nagarsekar A., Cooper Z., Manka C., Hester L., Benjamin I. J., He J. R., Hasday J. D. (2008) Heat shock co-activates interleukin-8 transcription. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 39, 235–242 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Schreiber E., Matthias P., Müller M. M., Schaffner W. (1989) Rapid detection of octamer binding proteins with 'mini-extracts,' prepared from a small number of cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 17, 6419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Singh I. S., He J. R., Calderwood S., Hasday J. D. (2002) A high affinity HSF-1 binding site in the 5′-untranslated region of the murine tumor necrosis factor-α gene is a transcriptional repressor. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 4981–4988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Singh I. S., Viscardi R. M., Kalvakolanu I., Calderwood S., Hasday J. D. (2000) Inhibition of tumor necrosis factor-α transcription in macrophages exposed to febrile range temperature. A possible role for heat shock factor-1 as a negative transcriptional regulator. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 9841–9848 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Maity T. K., Henry M. M., Tulapurkar M. E., Shah N. G., Hasday J. D., Singh I. S. (2011) Distinct, gene-specific effect of heat shock on heat shock factor-1 recruitment and gene expression of CXC chemokine genes. Cytokine 54, 61–67 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Thomson S., Hollis A., Hazzalin C. A., Mahadevan L. C. (2004) Distinct stimulus-specific histone modifications at Hsp70 chromatin targeted by the transcription factor heat shock factor-1. Mol. Cell 15, 585–594 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Calderwood S. K., Mambula S. S., Gray P. J., Jr., Theriault J. R. (2007) Extracellular heat shock proteins in cell signaling. FEBS Lett. 581, 3689–3694 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Applequist S. E., Wallin R. P., Ljunggren H. G. (2002) Variable expression of Toll-like receptor in murine innate and adaptive immune cell lines. Int. Immunol. 14, 1065–1074 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Ensor J. E., Crawford E. K., Hasday J. D. (1995) Warming macrophages to febrile range destabilizes tumor necrosis factor-α mRNA without inducing heat shock. Am. J. Physiol. 269, C1140–C1146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Vogel S. N., Fitzgerald K. A., Fenton M. J. (2003) TLRs. Differential adapter utilization by Toll-like receptors mediates TLR-specific patterns of gene expression. Mol. Interv. 3, 466–477 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Takeda K., Kaisho T., Akira S. (2003) Toll-like receptors. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 21, 335–376 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Guettouche T., Boellmann F., Lane W. S., Voellmy R. (2005) Analysis of phosphorylation of human heat shock factor 1 in cells experiencing a stress. BMC Biochem. 6, 4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Calderwood S. K., Xie Y., Wang X., Khaleque M. A., Chou S. D., Murshid A., Prince T., Zhang Y. (2010) Signal transduction pathways leading to heat shock transcription. Sign. Transduct. Insights 2, 13–24 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Singh I. S., He J. R., Hester L., Fenton M. J., Hasday J. D. (2004) Bacterial endotoxin modifies heat shock factor-1 activity in RAW 264.7 cells. Implications for TNF-α regulation during exposure to febrile range temperatures. J. Endotoxin Res. 10, 175–184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Shopland L. S., Hirayoshi K., Fernandes M., Lis J. T. (1995) HSF access to heat shock elements in vivo depends critically on promoter architecture defined by GAGA factor, TFIID, and RNA polymerase II binding sites. Genes Dev. 9, 2756–2769 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Ivaldi M. S., Karam C. S., Corces V. G. (2007) Phosphorylation of histone H3 at Ser10 facilitates RNA polymerase II release from promoter-proximal pausing in Drosophila. Genes Dev. 21, 2818–2831 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Guertin M. J., Lis J. T. (2010) Chromatin landscape dictates HSF binding to target DNA elements. PLoS Genet 6, 1001114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Dyson M. H., Thomson S., Mahadevan L. C. (2005) Heat shock, histone H3 phosphorylation and the cell cycle. Cell Cycle 4, 13–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Deleted in proof

- 56. Sugisawa N., Matsuoka M., Okuno T., Igisu H. (2004) Suppression of cadmium-induced JNK/p38 activation and HSP70 family gene expression by LL-Z1640–2 in NIH3T3 cells. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 196, 206–214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Stathopoulou K., Gaitanaki C., Beis I. (2006) Extracellular pH changes activate the p38-MAPK signalling pathway in the amphibian heart. J. Exp. Biol. 209, 1344–1354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Deak M., Clifton A. D., Lucocq L. M., Alessi D. R. (1998) Mitogen- and stress-activated protein kinase-1 (MSK1) is directly activated by MAPK and SAPK2/p38, and may mediate activation of CREB. EMBO J. 17, 4426–4441 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Davie J. R. (2003) MSK1 and MSK2 mediate mitogen- and stress-induced phosphorylation of histone H3. A controversy resolved. Sci. STKE 2003, PE33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Park G. Y., Joo M., Pedchenko T., Blackwell T. S., Christman J. W. (2004) Regulation of macrophage cyclooxygenase-2 gene expression by modifications of histone H3. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell Mol. Physiol. 286, L956–L962 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Ono K., Han J. (2000) The p38 signal transduction pathway. Activation and function. Cell Signal. 12, 1–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Hietakangas V., Anckar J., Blomster H. A., Fujimoto M., Palvimo J. J., Nakai A., Sistonen L. (2006) PDSM, a motif for phosphorylation-dependent SUMO modification. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 45–50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Hietakangas V., Ahlskog J. K., Jakobsson A. M., Hellesuo M., Sahlberg N. M., Holmberg C. I., Mikhailov A., Palvimo J. J., Pirkkala L., Sistonen L. (2003) Phosphorylation of serine 303 is a prerequisite for the stress-inducible SUMO modification of heat shock factor 1. Mol. Cell Biol. 23, 2953–2968 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Tetievsky A., Horowitz M. (2010) Posttranslational modifications in histones underlie heat acclimation-mediated cytoprotective memory. J. Appl. Physiol. 109, 1552–1561 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Vabulas R. M., Ahmad-Nejad P., Ghose S., Kirschning C. J., Issels R. D., Wagner H. (2002) HSP70 as endogenous stimulus of the Toll/interleukin-1 receptor signal pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 15107–15112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. De Nardo D., Masendycz P., Ho S., Cross M., Fleetwood A. J., Reynolds E. C., Hamilton J. A., Scholz G. M. (2005) A central role for the Hsp90.Cdc37 molecular chaperone module in interleukin-1 receptor-associated-kinase-dependent signaling by Toll-like receptors. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 9813–9822 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Gao B., Tsan M. F. (2003) Endotoxin contamination in recombinant human heat shock protein 70 (Hsp70) preparation is responsible for the induction of tumor necrosis factor α release by murine macrophages. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 174–179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Tsan M. F., Gao B. (2009) Heat shock proteins and immune system. J. Leukocyte Biol. 85, 905–910 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Asea A. (2008) Heat shock proteins and Toll-like receptors. Handb. Exp. Pharmacol. 183, 111–127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Basu S., Binder R. J., Ramalingam T., Srivastava P. K. (2001) CD91 is a common receptor for heat shock proteins gp96, hsp90, hsp70, and calreticulin. Immunity 14, 303–313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Vega V. L., Rodríguez-Silva M., Frey T., Gehrmann M., Diaz J. C., Steinem C., Multhoff G., Arispe N., De Maio A. (2008) Hsp70 translocates into the plasma membrane after stress and is released into the extracellular environment in a membrane-associated form that activates macrophages. J. Immunol. 180, 4299–4307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Wang R., Kovalchin J. T., Muhlenkamp P., Chandawarkar R. Y. (2006) Exogenous heat shock protein 70 binds macrophage lipid raft microdomain and stimulates phagocytosis, processing, and MHC-II presentation of antigens. Blood 107, 1636–1642 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Gastpar R., Gross C., Rossbacher L., Ellwart J., Riegger J., Multhoff G. (2004) The cell surface-localized heat shock protein 70 epitope TKD induces migration and cytolytic activity selectively in human NK cells. J. Immunol. 172, 972–980 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Zheng H., Nagaraja G. M., Kaur P., Asea E. E., Asea A. (2010) Chaperokine function of recombinant Hsp72 produced in insect cells using a baculovirus expression system is retained. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 349–356 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Srivastava P. K., Menoret A., Basu S., Binder R. J., McQuade K. L. (1998) Heat shock proteins come of age. Primitive functions acquire new roles in an adaptive world. Immunity 8, 657–665 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]