Abstract

Aims:

To identify the reproductive health issues associated with adolescence and the readiness to avail services like Adolescent Friendly Clinic (AFC) among urban school going children.

Materials and Methods:

A quantitative survey was carried out using a self-administered structured questionnaire among 1440 (748 girls and 692 boys) students from classes 6 -12 in 7 English medium and 23 Gujarati medium schools. Focus group discussions, 5 each with adolescent boys and girls and teachers were held from Gujarati and English medium schools.

Results:

A higher proportion of boys and girls could identify visible external changes in the opposite sex as compared to the changes not seen outwardly. The sources of information on human reproduction for most of the boys and girls were schoolbooks, television, teachers, friends and parents in the same order. Over two-thirds of the boys and girls expressed a need for more information on reproduction. Teachers also perceived that adolescents, though curious, lacked opportunities for open discussions to answer their queries related to reproductive health. One-third of the boys and one-fourth of the girls had heard about contraception. Two-thirds of boys and girls had heard of HIV/AIDS, and about half of them correctly knew various modes of transmission of HIV. Majority of the adolescents expressed their readiness to use the services of Adolescent Friendly Centre.

Conclusions and Recommendations:

Information on the human reproductive system and related issues on reproductive health need special attention. Teachers’ sensitization to adolescent health care is required.

Keywords: Adolescents, reproductive awareness, urban

INTRODUCTION

World Health Organization (WHO) defines adolescence as the period of life between 10 and 19 years of age. The adolescent experiences not only physical growth and change but also emotional, psychological, social, and mental change and growth.[1] Adolescence is a period of increased risk taking and therefore susceptibility to behavioural problems at the time of puberty and new concerns about reproductive health.[2] Adolescents constitute about 19% of the total population, yet remain a largely neglected, difficult-to-measure, and hard-to-reach population, in which the needs of adolescent girls in particular are often ignored.[3]

Nearly 20% of the 1.5 million girls married under the age of 15 years are already mothers. Twenty seven percent of married female adolescents have reported unmet needs for contraception.[4] Over 35% of all reported HIV/AIDS infections in India occur amongst young people 15-24 years age.[5]

Investments in adolescent friendly reproductive and sexual health will help in delaying the age at marriage, reducing teenage pregnancy, meet the unmet needs for contraception, reduce the incidence of HIV/AIDS and STIs and contribute to reduction of maternal, neonatal and perinatal mortality rates. Considering all these issues and need to provide services, the Government of Gujarat initiated an Adolescent Friendly Clinic (AFC) at the Medical College which worked as a center for adolescent health care, providing a special package of care and counselling, based on the needs of the adolescents.

Objectives

To identify the reproductive health issues associated with adolescence and the readiness to avail services like Adolescent Friendly Clinic (AFC) among urban school going children in Vadodara city.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Sample selection

A list of area wise distribution of schools of Baroda city was obtained from the office of the District Education Officer (DEO). The list included 177 schools affiliated to the Gujarat Secondary Education Board. Using systematic random sampling, from this list, a sample of 30 schools was selected for the study. The selected sample comprised 7 English medium and 23 Gujarati medium schools which is similar to the proportion of English medium schools in Vadodara. In the event of a school refusing permission or for logistic reasons, if it was not possible to include the school in the study sample, it was decided to take the next school on the list as replacement. As the list of schools was prepared administrative area wise, the sample had proportionate representation of all the administrative wards of the city.

Study tools

The study was carried out among adolescents of the selected urban schools. A quantitative survey was carried out using a self-administered structured questionnaire, either in English or Gujarati, among 1440 (748 girls and 692 boys) students from classes 6-12 in 7 English medium and 23 Gujarati medium schools. The questionnaire was pre-tested in both the languages. Focus group discussions, 5 each with adolescent boys and girls were held along with 5 focus group discussions with teachers from both Gujarati and English medium schools.

Considering the WHO definition of adolescents as persons in the age group of 10-19 years and the ability of school students to respond to the self-administered questionnaire, it was decided to include students from classes 6 to 12 in the study. The identified classes were explained the purpose of the study. Participation in the study was voluntary. To ensure confidentiality, the writing of the names was optional. The instruments were collected after checking for completeness. The FGDs were conducted class wise to get an idea regarding the evolving patterns by age and note the differences. It was decided to have eight participants in each FGD. FGDs were conducted with school teachers to understand their perspectives on the specific needs and common problems of the adolescents and mechanisms for resolving them. A note taker recorded each response verbal as well as non-verbal (silence, restlessness, posture, emotions, action, behavior), during the discussion. The notes were then revised, expanded, and checked immediately for completeness and accuracy. The data so collected were entered into the computer using Epi Info (version 6.04d) software.[6] Data cleaning was carried out, checked for discrepancies, and rectified. The answers to open-ended questions were grouped according to responses to quantify the emerging patterns. The responses from the FGDs were coded, grouped, and analyzed using standard techniques for analyzing FGD and emerging patterns were identified.

RESULTS

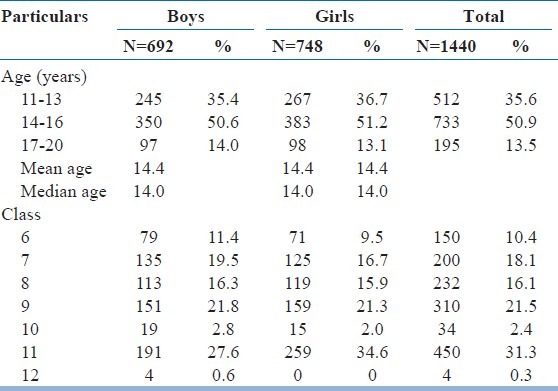

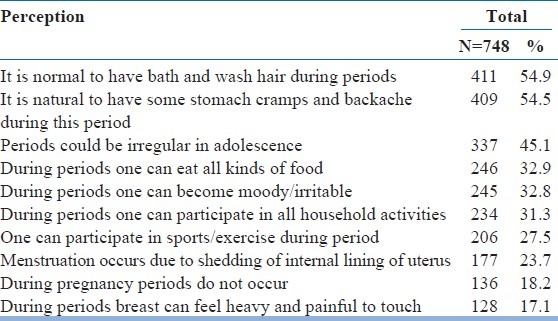

Background information of the adolescents who participated in the study are presented in [Table 1]. Boys put a premium on “gain in height” (linear growth), while for the girls’, it was the onset of menstruation that signified the change towards manhood and womanhood respectively. A higher proportion of boys and girls could identify visible external changes in the opposite sex [Tables 2 and 3]. Two-thirds of the girls had attained menarche, most of whom, had been informed about it, before they had their first period, by their mothers. A large majority did not know about biomedical reason for menses. Traditional taboos and restrictions on food and socio cultural activities were faced by many adolescent girls and were also thought to be right by many [Table 4]. With age the awareness regarding various aspects of menstruation increased. Most girls, in group discussions, also reported that they experience discomfort during menstruation.

Table 1.

Background information of the sample studied

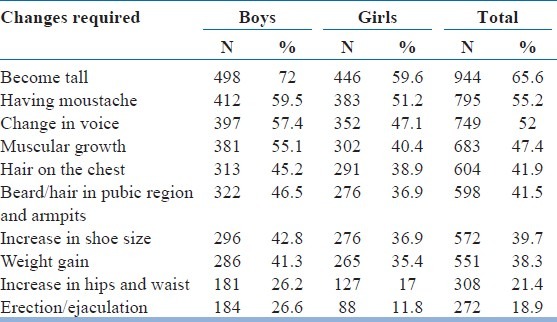

Table 2.

Changes needed for a boy to become a man as perceived by students

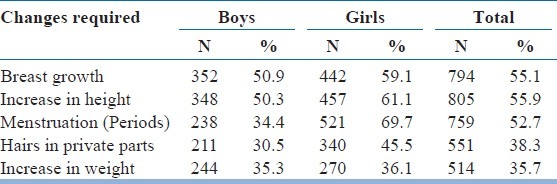

Table 3.

Changes needed for a girl to become a woman as perceived by students

Table 4.

Perceptions about various aspects of menstruation and related daily life among adolescent girls

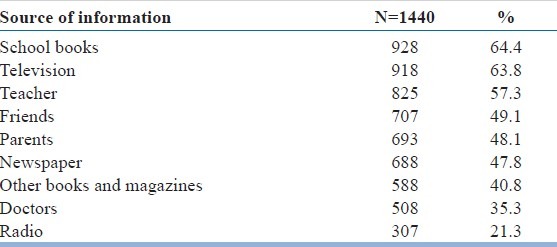

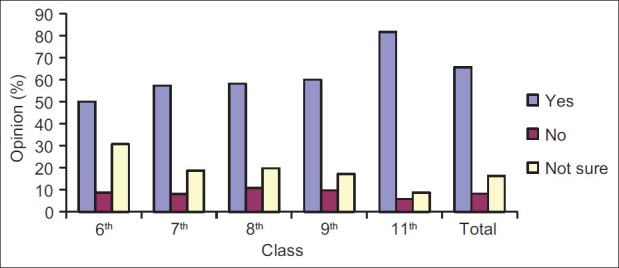

Common sources of information about human reproduction were schoolbooks, television, teachers, friends, and parents (in that order) [Table 5]. Considerable variation is seen with age. Very few of the boys and girls could correctly explain the process of reproduction. Over two-thirds of the students wanted more information on reproduction. Preferred sources for the same were mothers, doctors and teachers in the same order. One-third of the boys and one-fourth of the girls had heard about contraception, mainly Condoms (22 percent), intrauterine devices (11 percent) and oral pills (10 percent). In the group discussions, all the boys had heard about “garbh nirodhak goli” (contraceptive pills). About two-thirds of the adolescents, particularly those in the older ages, had heard about HIV / AIDS. Overall about 50 percent of adolescent boys and girls knew correctly, various modes of transmission of HIV. With age correct knowledge about various modes of transmission increased. Nearly 70 percent of adolescents were ready to use AFC, if it were to come up. Willingness to use AFC also increased with age [Figure 1].

Table 5.

Sources of information about reproduction among adolescents

Figure 1.

Readiness to use adolescent friendly clinic if available (standard wise)

Most of the teachers considered adolescence as the period between age 13 and 19 years. Teachers themselves hesitate and are uncomfortable in teaching topics related to reproduction. Though the need for reproductive health information is acknowledged by the teachers, not all are in favour of providing sex education to school children.

DISCUSSION

A higher proportion of boys and girls could identify visible external changes in the opposite sex like increase in height, change in voice, breast development, and growth of facial hair. Boys perceived breast growth, gain in height, weight and menstruation as the changes required in the girls to become women. Girls perceived that gain in height, growth of facial hair and becoming muscular (in that order), were the changes that made a boy transit into adulthood [Tables 2 and 3]. It was also seen that as age increases, knowledge about physical changes during adolescence increases. More boys and girls from the older age groups were aware of the less visible changes like erection / ejaculation, hair growth in pubic area and menstruation in the opposite sex. Mahajan and Sharma in a study conducted to assess reproductive awareness among adolescent girls found that urban adolescent girls had better knowledge regarding reproductive issues than rural adolescent girls.[7] One rural study has reported that two third of study subjects had knowledge of menstruation prior to attainment of menarche.[8]

The median age for attainment of menarche among the girls studied was 13 years. Though most of those who had started menstruating were told about it in advance, mostly by their mothers, a large number did not know the biological reason for the same, despite it being a part of their syllabus. In order to determine the prevailing myths and misconceptions and their knowledge of scientific facts regarding menstruation, adolescent girls were asked to give their opinion regarding some of the practices related to menstruation. Traditional taboos and restrictions on food and socio cultural activities like, being offered food separately, not being allowed to touch the idols of Gods, nor any family member, not being allowed to visit temples, were faced by many adolescent girls and were also thought to be right by many of them [Table 4]. Substantially higher proportion of girls in the older age groups of 14-16 years and 17-20 years knew the biomedical aspects like periods during adolescence can be irregular, cramps and discomfort are normal, mood swings are common, breasts can become heavy and painful, menstruation occurs due to the shedding of the internal lining of the uterus. With age the awareness regarding various aspects of menstruation increased. Older girls also seemed to believe less in the various food and other restrictions during menstruation. Among girls menstruation and its related problems like aches and pains was the most common problem. Only a few girls mentioned taking medicines to deal with menstrual pain. Though menstruation related problems were highlighted, no other ways of coping with the problems were mentioned by the girls. Constraints like not being able to dry the cloth (used during menstruation) in the open sunlight or the need to hide it from the male members of the family were expressed by girls from one of the schools.

During the focus group discussions, when asked what they knew about reproduction, very few of the boys and girls could correctly explain the process of reproduction. School curriculum was the source of information for those who could. This highlights the fact that school syllabus can play an important role. Watsa in a study of 4709 respondents showed that adolescents received sex information usually from mass media and friends but it was not reliable. Teachers were ill equipped to clear their doubts on sex.[9] Our study shows that the most common sources of information about human reproduction were schoolbooks, television, teachers, friends and parents as depicted in [Table 5]. This further stresses the importance of school curriculum, which if taught properly can contribute to improving the reproductive health knowledge among the adolescents. About two thirds of the adolescents wanted more information on the same and the preferred sources for them were mothers (33 percent), doctors (25 percent) and teachers (15 percent). This also reflects the acceptability of reproductive health information provided through doctors and this could become a part of the counseling activities for adolescents to be carried out by teachers. With increasing age there is a rather steep decline in the percentage of boys and girls reporting parents as the source. Teachers, books and magazines, television become more common sources with increasing age. With increasing age of adolescents, more boys, report friends as a source of information on reproduction. In other words, as boys and girls grow older they get to know about reproduction from schools, where the topic is included in the syllabus of the higher classes. With age they have greater access to various media including television, magazines and books from which they can access information on reproductive health. The role of parents as a source of information diminishes, while friends assume a greater role as a channel of information. Singh et al conducted a study in Haryana on 130 girls and observed that major source of information for reproductive facts was television (73.1) followed by radio (37.7%), parents (36.1%), friends (22.3%) posters (16.9%), teachers (6.9%) and health professionals (6.9%).[10]

One-third of the boys and one-fourth of the girls mentioned that they had heard about contraception, while one-fourth of the boys and one-third of the girls could not say anything about it (do not know). Out of those who had heard about the contraceptives, methods, like condoms (22 percent) were mentioned the most while tubectomy (0.7 percent) the least. In the group discussions, all the boys had heard about contraceptive pills. Some could even name the brand (Mala–D). One rural study conducted by Kotecha et al in 2005 found that 31% of boys and 33% of girls had heard about contraception.[11]

Most of the teachers missed the vital first three years of adolescence as they defined it as period between 13-19 years. Teachers perceived that adolescents become curious about the changes taking place in them, but they lack information and opportunities for open-discussions to get answers to their queries related to reproductive health. This contributes to the confusion, shame, and guilt among adolescents and they end up having distorted information on sex and sexuality. Though reproductive system and reproduction were part of the syllabus in classes 9, 10, and 11 in the old course, these topics were never taken up in the classroom, as teachers themselves hesitated and were uncomfortable in teaching these topics. They either made a passing reference to these topics or assigned them to their students for self-study. Teachers felt ill equipped to discuss reproductive health topics with their students and they also expect parents to impart this information to their adolescent wards. Teachers acknowledge the need for reproductive health information, but not all are in favor of providing sex education to school children. Those who expressed their reservations were mainly concerned about the impact of such education on adolescents. They feared increased knowledge might encourage promiscuity and experimentation.

Only 40 percent of the boys and 30 percent of the girls aged 11-13years had heard about HIV/AIDS as compared to more than two-thirds boys and girls belonging to the age groups of 14-16 years and 17-20 years. With age correct knowledge about various modes of transmission increased. In the 17-20 years age group, about three-fourths of the boys and girls knew that AIDS could be transmitted by receiving blood from an infected person; about two-thirds knew that it could be transmitted by having sexual relations with an infected person. One study conducted in urban area by Kotecha et al found that about 72% of young men and 47% of young women had heard about HIV.[12] Television, radio and newspapers (mass media) were the most common sources of information for HIV amongst the respondents. Only 50% knew that HIV can be present in apparently healthy looking persons. These findings were very similar to this study.

Nearly 70 percent of adolescents were ready to use AFC, if it were to come up. Less than 10 percent were not likely to use it, whereas the rest were not quite sure of it. Willingness to use AFC increases with age, boys and girls in the higher classes are more willing to utilize AFC [Figure 1]. Similar finding was observed by Kotecha et al in rural area.[11] One comparative study on utilization of adolescent health services by Nath et al found that school based services were better utilized than health facility based services.[13]

CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

Information on reproductive system, human reproduction and related issues and reproductive health are far from satisfactory and needs special attention amongst both students and teachers. Study pointed toward the need for information on reproductive system, human reproduction, and related issues and reproductive health for the students especially through curriculum as they form primary source of knowledge for them which is also easily accessible. This needs to be strengthened by capacity building of teachers to handle these topics and questions delicately. Majority of the adolescents expressed their willingness to avail the services of an AFC. Teachers’ orientation to “adolescent care” and, improving their capacity to talk and explain these topics, within the framework of course-curriculum is recommended.

Footnotes

Source of Support: World Health Organization, India

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Goldenring J. “Puberty and adolescence”. A Review provided by VeriMed Healthcare Network. Medline plus U.S. National library of Medicine. 1995 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Guidelines on Reproductive Health. New York: United Nations Population Information Network (popin); 1995. UNFPA. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Senderowitz J. World Bank Discussion Paper No 272. New Delhi: Office of the Registrar General; 1995. Adolescent health: reassessing the passage to adulthood. [Google Scholar]

- 4.New Delhi: Office of the Registrar General; 2001. Government of India Census of India. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Government of India, New Delhi. National Family Health Survey (NFHS-3)2005-06. 2007 Sep [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dean AG, Coulombier D, Brendel KA, Smith DC, Burton AG, Dicker RC, et al. Atlanta, Georgia, USA. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Atlanta, GA, US: Atlanta, Georgia; 2001. Epi_Info Version 6.04_d. A word processing, Database, and Statistical Programme for Public Health on IBM-compatible Microcomputers. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mahajan P, Sharma N. Awareness level of adolescent girls regarding HIV/AIDS (A comparative study of rural and urban areas of Jammu) J Hum Ecol. 2004;17:313–4. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dasgupta A, Sarkar N. Menstrual Hygiene: How Hygienic is the Adolescent Girl? Indian J Community Med. 2008;33:77–80. doi: 10.4103/0970-0218.40872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Watsa MC. Youth Sexuality. Mumbai (SECERT): Family Planning Association of India; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Singh MM, Devi R, Gupta SS. Awareness and health seeking behaviour of rural adolescent school girls on menstrual and reproductive health problems. Indian J Med Sci. 1999;53:439–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kotecha PV, Patel S, Baxi RK, Mazumdar VS, Misra S, Modi E. Reproductive health awareness among rural school going adolescents of Vadodara district. Indian J Sex Transm Dis. 2009;30:94–9. doi: 10.4103/2589-0557.62765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kotecha PV, Patel S. Measuring knowledge about HIV among youth: Baseline survey for urban slums of Vadodara. Indian J Sex Transm Dis. 2008;29:68–72. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nath A, Garg S. Adolescent friendly health services in India: A need of the hour. Indian J Med Sci. 2008;62:465–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]