Abstract

Pediatric Autoimmune Neuropsychiatric Disorders Associated with Streptococcal infection (PANDAS) is a group of disorders recently recognized as a clinical entity. A case of PANDAS is described here, which remitted after 1 month of treatment. Recent Group A beta-hemolytic streptococcus infection should be considered in a child who presents with a sudden explosive onset of tics or obsessive compulsive symptoms.

Keywords: PANDAS, tic disorder, obsessive compulsive disorder

INTRODUCTION

Group A beta-hemolytic streptococcus (GABHS), the etiologic agent responsible for acute rheumatic fever and Sydenham's chorea (SC), has recently been proposed to trigger tic disorders and obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD) in genetically predisposed children. With this, the spectrum of post-streptococcal disease has widened with the term “Pediatric Autoimmune Neuropsychiatric Disorders Associated with Streptococcal infection (PANDAS)”. However, in considering the prevalence of childhood-onset tic disorder and OCD, the diagnosis of PANDAS is rare. There is paucity of literature from India on PANDAS.

CASE REPORT

A 10 year-old girl presented to the pediatric outpatient department with chief complaints of abnormal involuntary movements involving the face and shoulder for the last 4 weeks. Around 1 week prior to these complaints, the patient had an episode of high-grade fever with throat pain. Few days after the resolution of fever, the parents noticed involuntary movements involving the face and shoulder. Movements were sudden, rapid and non-rhythmic. As per the parents, these movements were present whenever the child was awake. There was no history of loss of consciousness or head injury in the patient preceding or following the fever. Parents also reported that child cried too often for no apparent reason. Detailed psychiatric evaluation revealed that during the period of fever, the child had reported (even during remission of fever) fearfulness, seeing people coming to her, suggestive of visual hallucinations, which resolved spontaneously after 2-3 days. The child also showed withdrawn behavior along with emotional lability. Child was born of a non-consanguineous marriage after an uncomplicated pregnancy, full-term normal delivery at hospital. Regular immunizations were carried out. At birth, her weight and length were normal. Medical records and history suggested normal development. There was no family history of seizures or other abnormal movements/psychiatric complaints. On examination, the child was well oriented and higher mental functions were intact. Vitals were within normal limits. There were tic movements in both shoulders. Movements decreased but persisted when the child was observed in a restful state, with complete disappearance during sleep. Rest of the nervous system and other body systems were normal on examination. Hemoglobin (11.6 g/dl), total leukocyte count (8800/ mm3), differential leukocyte count (P58 L32 M8 E2), and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (11 mm fall in first hour) were within normal limits. Other blood investigations revealed normal sugar, electrolytes levels, and liver function tests. In view of recent past history of sore throat, anti-streptolysin O (ASO) titers were estimated and found to be high (350 Todd units).

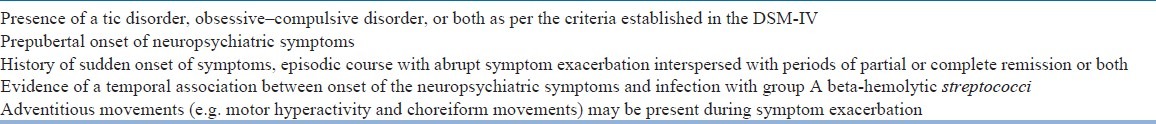

Electroencephalography (EEG) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) brain were normal. Thus, diagnosis of PANDAS syndrome was made, as our case met all the required diagnostic criteria [Table 1].

Table 1.

Criteria for the diagnosis of pediatric autoimmune, neuropsychiatric disorders[1]

Initially, the patient was treated with 10 mg Fluoxetine, but the child developed skin rashes all over, so in view of that it was stopped. Later, patient was started on Clonidine 0.1 μg ¼ QID and Clonazepam 0.25 mg BD. After 8 days of hospitalization, patient was discharged with a significant improvement. After a follow-up of 2 weeks, the patient was maintaining the improvement and is doing well at 3 months post discharge.

DISCUSSION

PANDAS are a recently described subgroup of childhood disorders, and there has been a great deal of public and physician interest in their pathophysiology, diagnosis, and management. The first 50 PANDAS patients were reported in the literature in 1998 by Swedo et al.[1] PANDAS and SC have similar clinical features, including emotional lability, attention and impulsivity difficulties, motor hyperactivity, and clumsiness with deterioration in fine motor skills. The biologic evidence that PANDAS in an autoimmune-mediated process is compelling but not conclusive. Few recent studies documented that patients of PANDAS, with onset of symptoms following GABHS pharyngitis, responded to antibiotic therapy/surgical treatment like tonsillectomy.[2,3] A potential B cell marker D8/17 has been identified.[4] MRI of the brain demonstrates basal ganglia changes consistent with inflammation,[5,6] and immunomodulatory therapies have been studied with benefit in some patients. Evidence against this mechanism also exists. A recent study refutes the role of antineuronal antibodies found in SC to be causative in PANDAS.[7] Also, antibiotic prophylaxis, although effective in SC associated with acute rheumatic fever, remains questionable in PANDAS.

Diagnosis

To make a diagnosis of PANDAS, patients must fulfill proposed criteria[1] [Table 1]. Evidence of GABHS infection includes a positive throat culture for GABHS, or elevated or increasing antibody titers (ASO, anti-DNase B) demonstrating a recent GABHS infection. In our case, high ASO titers suggested recent infection. Throat culture was negative for GABHS. As it is a post-infectious phenomenon and cases may occur even months after infection,[1] cultures may be negative by the time patient presents to the physician.

Though the laid down diagnostic criteria include episodic course of exacerbations (temporally correlated with GABHS infection) and remissions, what time period constitutes “temporal” association has not been defined. Abnormalities on MRI occur consistently in patients with SC, but in PANDAS, the clinical application of MRI studies is limited.[5,6,8] In our case also, the patient had a normal MRI of brain.

We had high index of suspicion in view of clinical picture and history of patient, and after investigations, we made the diagnosis of PANDAS.

Therapeutic options

Our patient responded to the standard drugs for control of symptoms. There are case reports showing the role of intravenous immunoglobulins (IVIG), plasma exchange, and steroids, but it is still not entirely clear that immunomodulatory therapies are beneficial.[9] It is possible that some of these children's symptoms, especially tics, spontaneously improve with time. IVIG and plasma exchange are invasive and costly therapies, often associated with side effects and at present are reserved for severe patients registered in therapeutic trials.[10] We did not use any immunomodulating agents.

Antibiotic prophylaxis

As of today, there is no recommendation for antibiotic prophylaxis for PANDAS. We did not put the patient on prophylaxis, but she is in our close follow-up.

Clinical implications

Though at present the diagnostic criteria [Table 1] should be followed to make the diagnosis of PANDAS, it is a debatable issue in certain aspects.[10] For example, what time period forms “temporal association” is not defined. A unique specificity of a clinical course consisting of abrupt onset or dramatic exacerbations has not been documented adequately. Clinical course does not seem particularly useful in distinguishing patients suspected of PANDAS from children with more typical cases of Tourette syndrome (TS) or OCD.[10] Even in the first episode, it may be prudent to consider PANDAS as diagnosis, as it guides the patient, family, and the physician in subsequent infections. These issues need scientific exploration. Close follow-up studies (of long durations) of streptococcal infections are needed in India where infections and carrier rate of GABHS are very high and literature on PANDAS is scarce.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Swedo SE, Leonard HL, Garvey M, Mittleman B, Allen AJ, Perlmutter S, et al. Pediatric autoimmune neuropsychiatric disorders associated with streptococcal infections: Clinical description of the first 50 cases. Am J Psychiatry. 1998;155:264–71. doi: 10.1176/ajp.155.2.264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Murphy ML, Pichichero ME. Prospective identification and treatment of children with pediatric autoimmune neuropsychiatric disorder associated with group A streptococcal infection (PANDAS) Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2002;156:356–61. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.156.4.356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Batuecas Caletrío A, Sánchez González F, Santa Cruz Ruiz S, Santos Gorjón P, Blanco Pérez P. PANDAS Syndrome: A new tonsillectomy indication? Acta Otorrinolaringol Esp. 2008;59:362–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Khanna AK, Buskirk DR, Williams RC, Jr, Gibofsky A, Crow MK, Menon A, et al. Presence of a non-HLA B cell antigen in rheumatic fever patients and their families as defined by a monoclonal antibody. J Clin Invest. 1989;83:1710–6. doi: 10.1172/JCI114071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Giedd JN, Rapoport JL, Kruesi MJ, Parker C, Schapiro MB, Allen AJ, et al. Sydenham's chorea: Magnetic resonance imaging of the basal ganglia. Neurology. 1995;45:2199–202. doi: 10.1212/wnl.45.12.2199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Castillo M, Kwock L, Arbelaez A. Sydenham's chorea: MRI and proton spectroscopy. Neuroradiology. 1999;41:943–5. doi: 10.1007/s002340050872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brilot F, Merheb V, Ding A, Murphy T, Dale RC. Antibody binding to neuronal surface in Sydenham chorea, but not in PANDAS or Tourette syndrome. Neurology. 2011;76:1508–13. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182181090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Giedd JN, Rapoport JL, Garvey MA, Perlmutter S, Swedo SE. MRI assessment of children with obsessive-compulsive disorder or tics associated with streptococcal infection. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157:281–3. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.2.281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Perlmutter SJ, Leitman SF, Garvey MA, Hamburger S, Feldman E, Leonard HL, et al. Therapeutic plasma exchange and intravenous immunoglobulin for obsessive-compulsive disorder and tic disorders in childhood. Lancet. 1999;354:1153–8. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)12297-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kurlan R, Kaplan EL. The pediatric autoimmune neuropsychiatric disorders associated with streptococcal infection (PANDAS) etiology for tics and obsessive-compulsive symptoms: Hypothesis or entity. Practical considerations for the clinician? Pediatrics. 2004;113:883–6. doi: 10.1542/peds.113.4.883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]