Abstract

A 39-year-old female with elevated serum cobalt levels from her bilateral hip prostheses presented with a 3-week history of blurred vision in her left eye. Optical coherence tomography revealed patchy degeneration of the photoreceptor-retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) complex. The lesions were hypofluorescent on indocyanine green angiography. We postulate that this is a case of implant-related chorio-retinal cobalt toxicity.

Keywords: Cobalt toxicity, implant related chorio-retinal toxicity, photoreceptor-retinal pigment epithelium degeneration

Cobalt toxicity, although rare, is an emerging problem given the increasing number of cobalt-alloy prostheses used for joint replacement in particular metal-on-metal hip implants. Ocular, cardiac, nervous, and endocrine manifestations have been reported in association with implant-related cobalt toxicity. Ophthalmic complications in humans, namely optic nerve atrophy, have been described in patients with toxic serum levels of cobalt.[1–3] Chorio-retinal damage, however, has only been documented in animal studies.[4,5] Here, we present a case of chorio-retinal changes presumably caused by implant-related toxic serum levels of cobalt.

Case Report

A 39-year-old female with bilateral development dysplasia of the hips, for which she had undergone bilateral hip replacements (ASR™ Hip System, DePuy Orthopaedics , Warsaw, IN, USA) 2 and 5 years ago, presented with a 3-week history of a paracentral scotoma in her left eye and bilateral ocular discomfort. She also complained of occasional metallic taste in her mouth and early morning nausea. She denied taking any medication and was not aware of any occupational exposure to toxic substances. She had no other significant medical or ocular history. The family history was unremarkable. The type of implant present in this patient has recently been recalled owing to wear-related toxic cobalt and chromium release and hazardous metallosis.

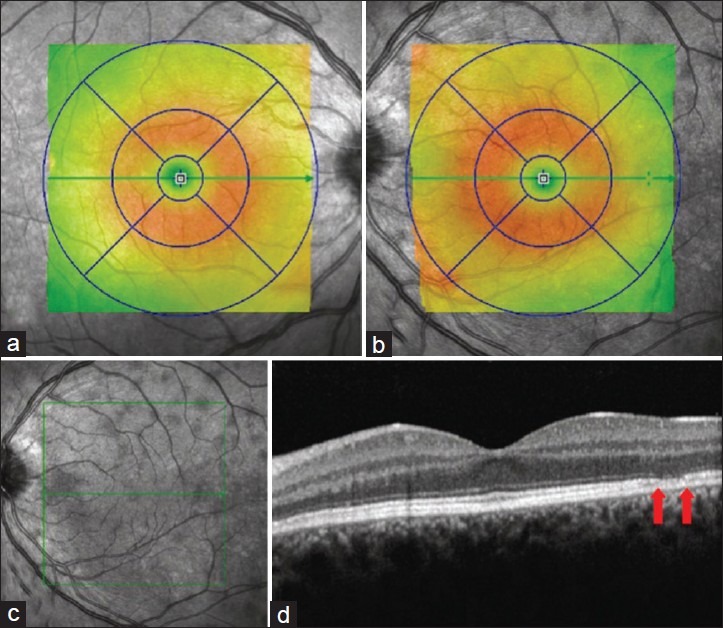

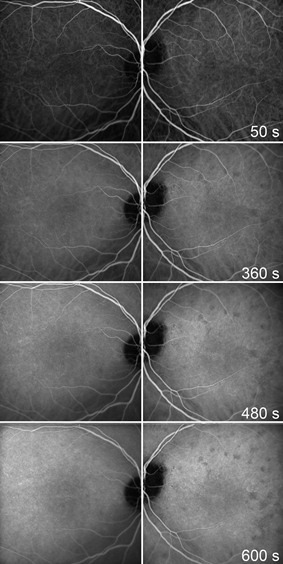

On examination, the patient had good central visual acuity of 20/16 in both eyes. No relative afferent pupillary defect was noted. Intraocular pressures were within normal limits. Both anterior segments and fundi were unremarkable under slit lamp examination and indirect fundoscopy. Automated visual field testing (Humphrey 24-2) did not reveal any visual field defect. The patient proceeded to have a high-resolution optical coherence tomography (OCT) scan, which showed several circumscribed lesions of the outer retina at the level of the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) and the photoreceptors [Fig. 1]. These patchy lesions were hypofluorescent on indocyanine green (ICG) angiography [Fig. 2] but could not be demonstrated with fluorescein angiography. The thickness map showed diffuse mild thickening of the macula, predominantly perifoveal.

Figure 1.

a and b represent retinal thickness of the right and left eye, respectively. Perifoveal diffuse thickening is seen in the left eye. c. The infrared image reveals multiple hyporeflective lesions. d. The OCT shows discrete lesions with thinning of the photoreceptor-RPE complex (arrows)

Figure 2.

The ICG angiography shows numerous hypofluorescent lesions in the affected eye

Electrophysiology testing was also performed. Occipital pattern reversal visual evoked potentials were recorded for right and left eyes, monocularly using standard 35’ checks and also with the very small 9’ checks. The responses were well developed with normal latencies for both eyes. No significant interocular or interoccipital asymmetries were noted. Cutaneous electroretinograms were recorded using a Color Dome Ganzfeld stimulator and lower eyelid electrodes without pupil dilation. Dark adaptation was standard for 20 minutes. Electroretinograms were well developed for both eyes with responses for the left were generally of slightly lower amplitudes in comparison to the right. Pattern electroretinograms recorded using 140’ check reversal stimulation (4/s) showed equal and well developed responses for both eyes. The electro-oculograms were well developed with a well-defined dark trough and light peak. The light peak was higher for the right eye compared to the left. The Arden index was satisfactory for the right eye (2.9) whereas borderline normal for the left eye (1.9).

Laboratory testing showed elevated serum cobalt and chromium levels, 757 nmol/L (0-20 nmol/L), and 595 nmol/L (10-200 nmol/L) respectively at the time of presentation. Physician assessment did not reveal any signs of other system involvement and electrocardiograph and thyroid function tests were within normal limits.

The diagnosis of toxic chorio-retinal degeneration presumably secondary to toxic serum levels of cobalt was made. The patient was advised to monitor her vision with the Amsler grid. No progression was noted on subsequent reviews, one and six months later. Thorough examinations by her orthopedic surgeon confirmed a good functional result of the implants. The serum cobalt and chromium levels remained stable. Given the lack of clinical progression, no intervention was considered necessary as yet. The patient continues to have regular follow-up with her family doctor, orthopedic surgeon, and ophthalmologist.

Discussion

The retina, one of the most metabolically active tissues in the body, requires a continuous oxygen supply to maintain optimal function. Photoreceptor cells found in the outermost layers of the retina rely mainly on choroidal blood supply. The high demand for oxygen renders these cells particularly vulnerable to hypoxia. Hence, choroidal ischemia will lead to hypoxic injury of the outer retina and consequently photoreceptor degeneration.[4]

Cobalt chloride is a hypoxia-mimicking compound, which exerts hypoxia-like effect on the local retina microenvironment. Several animal studies have shown that toxic level of cobalt will induce photoreceptor degeneration.[4,5] Hara et al. reported photoreceptor cell degeneration following intravitreal cobalt chloride injection in both rat and mouse retinas.[4] Monies et al. experimentally demonstrated choroidal vessel obliteration and alteration in the photoreceptor nucleus in rabbit retinas after intraperitoneal cobalt chloride injection.[5] We postulate that toxic serum cobalt concentrations have a similar effect on the human retina and can cause retinal degeneration.

In our patient, degenerative alterations of the photoreceptor-RPE complex were noted on OCT. The ICG angiography findings were suggestive of choroidal infarction. The distribution of the lesions noted on ICG angiography corresponded with the OCT findings and was consistent with patient's paracentral scotomas. Satisfactory visual evoked potentials and pattern electroretinograms indicated normal ganglion cells and optic nerve function. The electroretinograms showed a tendency toward slightly reduced amplitudes in left eye responses and the electro-oculograms findings suggested reduced RPE function in the left eye. Mild RPE dysfunction in the left eye demonstrated by electrophysiology testings reinforced our clinical diagnosis.

The asymmetric ocular manifestation may be explained by differences in choroidal perfusion, which can vary between eyes.[6] Asymmetric presentation had also been previously described for systemic lead toxicity.[7] We believe that this is the first case report of implant-related cobalt toxicity to the outer retina.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil.

Conflict of Interest: No.

References

- 1.Meecham HM, Humphrey P. Industrial exposure to cobalt causing optic atrophy and nerve deafness: A case report. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1991;54:374–5. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.54.4.374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rizzetti MC, Liberini P, Zarattini G, Catalani S, Pazzaglia U, Apostoli P, et al. Loss of sight and sound. Could it be the hip? Lancet. 2009;373:1052. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60490-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Steens W, von Foerster G, Katzer A. Severe cobalt poisoning with loss of sight after ceramic-metal pairing in a hip: A case report. Acta Orthop. 2006;77:830–2. doi: 10.1080/17453670610013079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hara A, Niwa M, Aoki H, Kumada M, Kunisada T, Oyama T, et al. A new model of retinal photoreceptor cell degeneration induced by a chemical hypoxia-mimicking agent, cobalt chloride. Brain Res. 2006;1109:192–200. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.06.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Monies A, Prost M. Experimental studies on lesions of eye tissues in cobalt intoxication. Klin Oczna. 1994;96:135–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen SJ, Cheng CY, Lee AF, Lee FL, Chou JC, Hsu WM, et al. Pulsatile ocular blood flow in asymmetric exudative age related macular degeneration. Br J Ophthalmol. 2001;85:1411–5. doi: 10.1136/bjo.85.12.1411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gilhotra JS, Von Lany H, Sharp DM. Retinal lead toxicity. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2007;55:152–4. doi: 10.4103/0301-4738.30716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]