Abstract

HIV-1 proteins, including the transactivator of transcription (Tat), are believed to be involved in HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders by disrupting Ca2+ homeostasis, which leads to progressive dysregulation, damage, or death of neurons in the brain. We have found previously that bath-applied Tat abnormally increased Ca2+ influx through overactivated, voltage-sensitive L-type Ca2+ channels in pyramidal neurons within the rat medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC). However, it is unknown whether the Tat-induced Ca2+ dysregulation was mediated by increased activity and/or the number of the L-channels. This study tested the hypothesis that transient/early exposure to Tat in vivo promoted enduring L-channel dysregulation in the mPFC without neuron loss. Accordingly, rats were administered a single intracerebroventricular injection of recombinant Tat (80 µg/20 µl; diluted by cerebrospinal fluids to pathophysiological concentrations) or vehicle. Rats were killed 14 days after injection for immunohistochemical assessments of the mPFC, motor cortex, caudate–putamen, and nucleus accumbens. Stereological estimates for positively stained cells indicated a significant increase in the number of cells expressing the pore-forming Cav1.2-α1c subunit of L-channels in the mPFC compared with other regions in Tat-treated or vehicle-treated rat brains. Optical density measurements showed a Tat-induced increase in glial fibrillary acidic protein expression, indicating astrogliosis in the cortical regions. There was no significant loss of neurons in any brain region investigated. These findings indicate that transient Tat exposure in vivo induced enduring L-channel dysregulation and astrogliosis in the mPFC without neuron loss. Such maladaptations may contribute toward dysregulated Ca2+ homeostasis and neuropathology in the PFC in the early stages of HIV infection.

Keywords: astrogliosis, L-type Ca2+ channels, medial prefrontal cortex, neuroAIDS

Introduction

Despite aggressive antiretroviral therapy, HIV-associated neurocognitive disorder occur in over 50% of the HIV+ population [1]. HIV-1 is carried into the central nervous system (CNS) by infected macrophages and monocytes [2]. Once the virus enters the brain, infection spreads to glial cells [2]. Antiretroviral medications do not readily cross the blood–brain barrier [3], allowing the brain to serve as a reservoir for viral replication and viral protein secretion [4]. Chronic exposure to HIV-1 viral proteins is associated with numerous consequences throughout the brain; however, some brain regions have been clinically documented to be more vulnerable to HIV/AIDS [5]. Such regions include, but are not limited to, the medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC) and basal ganglia [e.g. the caudate–putamen and nucleus accumbens (NAc)], two critical regulators of neurocognitive function, and psychomotor activity [5].

CNS exposure to HIV-1 viral proteins is associated with progressive inflammation and Ca2+ dysregulation [6]. Transactivator of transcription (Tat) is an early HIV-1 protein produced and actively released by HIV-infected cells [6]. Extracellular Tat dysregulates Ca2+ homeostasis in neurons by abnormally increasing Ca2+ influx, likely through Ca2+-permeable ionotropic glutamate receptors [7] and voltage-gated Ca2+ channels [7, 8]. Excessive cytosolic Ca2+ becomes excitotoxic; therefore, overactivation of these Ca2+ channels in neurons could contribute to the pathophysiology of Tat. Moreover, the dysregulation of Ca2+ can be exacerbated by Tat-induced maladaptations in astrocytes that result in the dysfunction of astrocyte-mediated synaptic uptake of glutamate [9]. Continual exposure to dysregulated cytosolic Ca2+ could facilitate neuronal overexcitation, damage, and death [9]. In addition, even a short-term exposure to Tat (a few minutes) is sufficient to produce dysfunction of astrocytes, leading to an enduring Ca2+ dysregulation in the affected neurons [10]. Thus, it is likely that even a transient exposure to low concentrations of Tat is sufficient to induce integrated dysregulation in astrocytes and neurons.

Cav1.2 L-type Ca2+ channels are voltage-activated Ca2+ channels existing in both neurons and astrocytes in the mPFC and basal ganglia [11, 12]. Blockade of the L-channels acutely reduces Tat-induced Ca2+ influx [8]. Thus, the L-channels likely play a critical role in Tat-induced Ca2+ dysregulation and neuropathology in the CNS. This study was designed to determine the dysregulation from transient Tat exposure in vivo on the L-channels and astrocytes in the rat PFC and basal ganglia.

Methods

Male Sprague–Dawley rats (n = 6; Harlan Labs, Indianapolis, Indiana, USA) weighing 225–250 g were housed under environmentally controlled conditions and allowed to habituate for 1 week before experimentation. Food and water were available ad libitum. All procedures followed the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (National Research Council, Washington, District of Columbia, USA) as approved by the Rush University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Recombinant Tat was provided by Dr Fatah Kashanchi (Department of Microbiology, George Mason University, Manassas, Virginia, USA) or the National Institutes of Health (NIH) AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program (Germantown, Maryland, USA). HIV-1 Tat protein was overexpressed in Escherichia coli B under the control of the lambda pL promoter. Tat-expressing cells were sonicated, clarified by centrifugation, and the insoluble Tat was resuspended in buffer containing 6M GuHCl. The Tat was chromatographed on a Sephacryl S-200 (GE Healthcare Life Sciences, Piscataway, New Jersey, USA) sizing column and finally purified to homogeneity on a C-18 reverse-phase HPLC column. The Tat protein was lyophilized and resuspended immediately before use in PBS without Mg2+ or Ca2+ 0.1 mM dithiothreitol and 0.1% BSA. Tat was dissolved in PBS and stored at − 80°C before use.

Tat was administered directly into a lateral ventricle. For this, rats were anesthetized with sodium pentobarbital (50 mg/kg, intraperitoneally; Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, Missouri, USA) and placed in a stereotaxic frame (David Kopf, Tujunga, California, USA) with the nose piece set at −3.3 mm. A scalp midline incision was made and a burr hole was drilled through the skull of one hemisphere at 0.9 mm anterior to the bregma, 1.4 mm lateral to the midline, and 4.3 mm ventral to the skull. Using a motorized injection pump (Stoelting, Wood Dale, Illinois, USA), Tat (80 µg/20 µl; n = 3) or PBS (20 µl; n = 3) was infused directly into the lateral ventricle at a rate of 1 µl/min using a 30 G needle attached to a 25 µl syringe (Hamilton Co., Reno, Nevada, USA). When diluted in the CSF, this amount of Tat is able to reach low nanomolar concentrations, within the CSF concentration range for Tat believed to be achieved in HIV+ humans [6].

The needle was left in place for an additional 3 min after the injection was administered to allow for fluid diffusion from the injector tip. The burr holes were filled with bone wax and the incision was sutured. Following recovery from anesthesia, the rats were returned to the vivarium and monitored daily; all animals showed normal grooming behaviors and weight gain without signs of infections following injections of Tat or PBS. Fourteen days after treatment, rats were deeply anesthetized using chloral hydrate (400 mg/kg intraperitoneally; Sigma-Aldrich) and perfused transcardially with ice-cold saline, followed by 4% paraformaldehyde (pH 7.4). The brains were removed and postfixed in 4% paraformaldehyde overnight. Brains were transferred to 30% sucrose until saturated, sliced into serial coronal sections (40 µm) using a sliding microtome, and sections were stored in a cryoprotectant at −20°C before use.

Primary antibody incubation was carried out with antiglial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP, 1 : 10 000; DakoCytomation, Glostrup, Denmark), anti-Cav1.2-α1c L-channel (Cav1.2, 1 : 100; Alomone Labs, Jerusalem, Israel), and antineuronal nuclear protein (NeuN, 1 : 1000; Millipore, Temecula, California, USA) for 48 h at 4°C, followed by the appropriate secondary antibodies (1 : 200; Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, California, USA). GFAP-immunoreactivity (ir) and NeuN-ir were visualized using a chromogen solution containing 3′3 diaminobenzidine and hydrogen peroxide. Cav1.2-ir was enhanced with nickel (Sigma-Aldrich). Negative controls were performed in the absence of the primary antibody.

Qualitative assessments of the entire brain were carried out for all three stains. Subsequently, optical density was utilized to verify our qualitative assessments before performing stereological counts of Cav1.2-ir and NeuN.

Qualitative assessments indicated obvious differences in staining in brain regions that were evaluated by optical density for GFAP-ir and stereological estimations of Cav1.2-ir. These areas included the mPFC, the motor cortex (MC), the caudate–putamen [dorsal striatum (Str)], and the NAc, including the core and shell subregions. The hippocampus also expressed high GFAP-ir, but this region was used for a parallel study that did not involve Cav1.2-ir and data are not presented here.

Optical density values were calculated by a treatment-blind observer using ImageJ software (NIH, Bethesda, Maryland, USA). Series of six photomicrographs were taken at × 4 magnifications and converted into gray scale containing the mPFC, MC, Str, and the NAc core/shell identified by specific anatomical landmarks [13]. The photomicrographs containing the mPFC and MC were collected between +4.2 and +2.2 mm anterior to the bregma. Consecutive sections containing the Str and the NAc core/shell were obtained between +2.2 and +1.0 mm anterior to the bregma. Optical density was measured for a 0.5 mm2 area within each brain region. Background measurements were taken from the anterior commissure and subtracted from the mean optical density value for each region [14, 15].

Stereological estimates of the total number of NeuN-ir and Cav1.2-ir cells were determined by a treatment-blind observer of regions located contralateral to the injected hemisphere to avoid the potential variability resulting from injection-related mechanical trauma. The Stereo Investigator 2000 system (MBF Bioscience, Williston, Vermont, USA) was used to perform unbiased stereological estimates per an optical fractionator procedure [16]. Under low magnification (× 1.25), the regions of interest were outlined. Optical dissectors were defined using dissector height set at 15 µm and guard zones of 2 µm. Cell counts were carried out in a counting frame of 75 µm2 at regular intervals (X = 250 µm, Y = 250 µm). The sections were analyzed using a high magnification (× 60) oil-immersion objective. The coefficient of error was calculated using the Gundersen method.

All data are presented as mean ± SEM. Comparisons between groups were made using Student’s t-test with α equal to 0.05 using SPSS software (IBM, Armonk, New York, USA).

Results

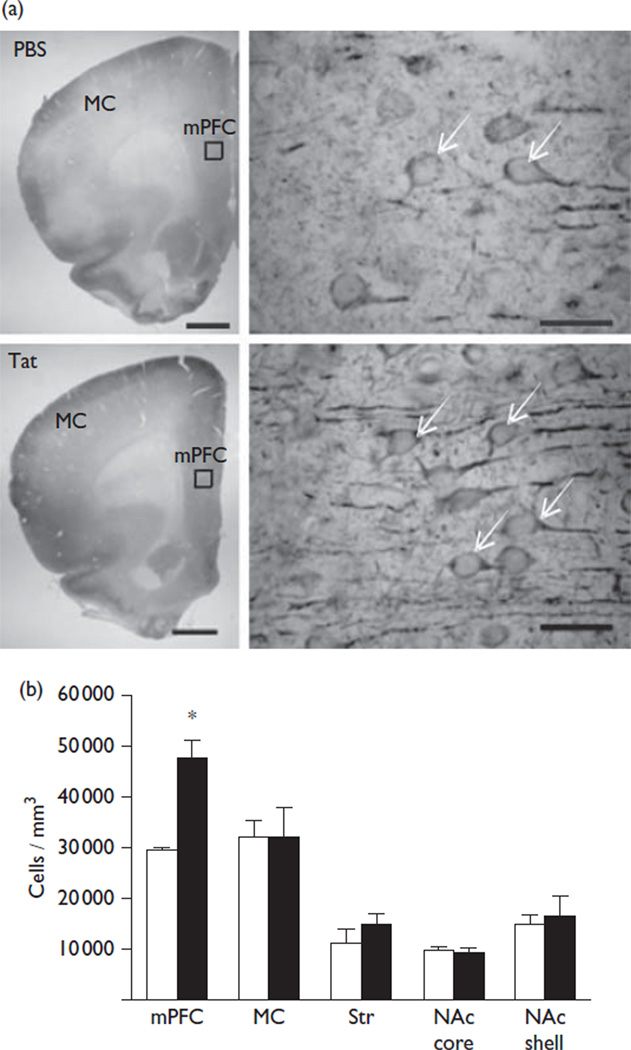

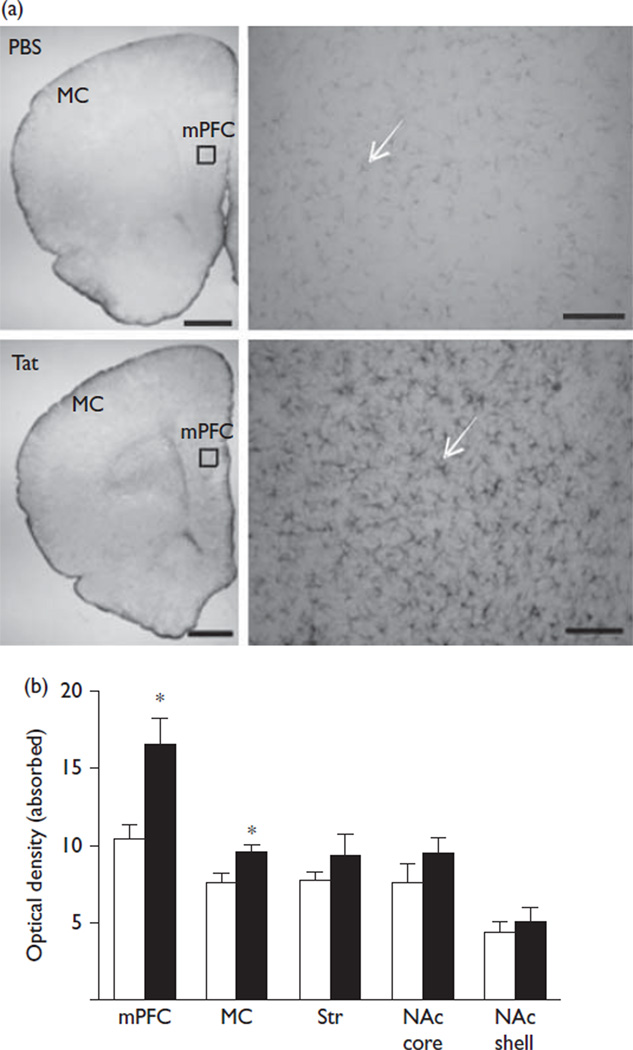

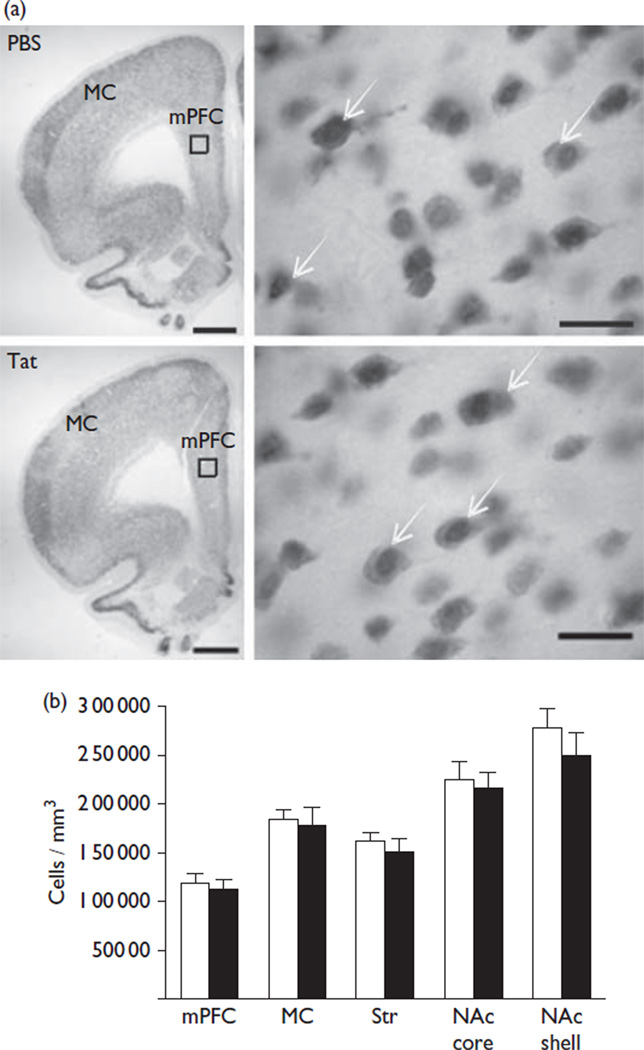

The acute intracerebroventricular injection of Tat allowed for assessments of brain mechanisms engaged during initial exposure. A pathophysiologically relevant, low nanomolar CSF concentration [6] provided the means to study cellular dysregulation without neuronal loss. We found that the Tat-injected hemisphere showed ventricular enlargement. No enlargement of the ventricles was observed in the hemisphere contralateral to intracerebroventricular Tat or in either hemisphere following the PBS injection. Stereological assessments indicated that the mPFC of Tat-treated rats showed a significantly higher number of Cav1.2-ir cells compared with vehicle-treated rats (29 480±707 vs. 47 290±3888; t(4) = 4.50, P = 0.01) (Fig. 1). These cells were located in layers five and six and were ~25 µm in diameter with a distinct nucleus, a profile that is consistent for pyramidal neurons. No significant change in the number of Cav1.2-ir cells was found in the MC, Str, and the NAc core/shell between Tat-treated and vehicle-treated rats. Optical density measurements of GFAP were performed to determine whether astrogliosis occurred at 14 days after injection. GFAP-ir is largely restricted to astrocytic processes, and does not clearly identify the small soma (<~10 µm) of astrocytes (Fig. 2). Rats exposed to Tat showed a significant increase in the GFAP-ir staining intensity within the mPFC (10.4±1.0 vs. 16.4±1.8; t(4) = 2.98, P = 0.04) and MC (7.6±0.7 vs. 10.6±0.8; t(4) = 2.87, P = 0.05) (Fig. 2) compared with the vehicle treatment. No significant alterations were observed in the Str or the NAc core/shell. There was no significant loss in the number of NeuN-ir cells in any brain region evaluated between Tat-treated rats and vehicle-treated controls (Fig. 3).

Fig. 1.

Transactivator of transcription (Tat)-induced changes in Cav1.2-α1c-ir cells. (a) Representative brain sections containing the medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC) and the motor cortex (MC) are shown at × 1.25 magnification for both vehicle (PBS) and Tat treatments in the top left images (scale bar = 1 mm) and at × 100 magnification in the top right images (scale bar = 50 µm). The regions containing the × 100 photomicrographs are indicated by a box on the × 1.25 images. Arrows denote Cav1.2-ir cells. (b) Tat significantly increased the number of Cav1.2-ir cells within the mPFC. No significant differences were observed in the MC, dorsal striatum (Str), or nucleus accumbens (NAc) core/shell (vehicle=white, Tat=black); *P<0.05.

Fig. 2.

Transactivator of transcription (Tat)-induced alterations in glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP)-ir cells. (a) Representative brain sections are shown at × 1.25 containing the medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC) and the motor cortex (MC) in the top left images for both treatments (scale bar = 1 mm). Representative × 20 magnification images of the mPFC at the top right and the location for these figures are indicated by a box on the × 1.25 images (scale bar = 100 µm). (b) Tat significantly increased the optical density of GFAP-ir cells within the mPFC and MC. No significant differences were observed in the dorsal striatum (Str) or the nucleus accumbens (NAc) core/shell (vehicle=white, Tat =black); *P<0.05. Ir, immunoreactivity.

Fig. 3.

Transactivator of transcription (Tat) did not alter the number of NeuN-ir cells. (a) Representative brain sections × 1.25 containing the medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC) and the motor cortex (MC) for both treatments are shown on the top left (scale bar = 1 mm). Representative × 100 magnification images of the mPFC at the top right and the location for these images are indicated by a box on the × 1.25 images (scale bar = 50 µm). Arrows denote NeuN-ir cells. (b) No significant loss of NeuN-ir cells was found following an intracerebroventricular microinjection of either Tat or PBS in any brain region (vehicle = white, Tat = black). Ir, immunoreactivity.

Discussion

The novel findings indicated that after a transient Tat exposure in vivothere was a significant increase in the number of Cav1.2-ir cells and astrogliosis in the cortical regions of rats. These changes were not associated with significant loss of neurons, suggesting that early exposure of the brain to Tat induces a region-specific L-channel dysregulation and astrogliosis in the mPFC, likely, without neuronal death.

In-vitro studies have verified that high nanomolar concentrations of Tat can cause excessive Ca2+ influx and death of cortical neurons, microglial cells, and monocytes, and these effects of Tat can be reduced by blockade of L-channels [17, 18]. In an in-vitro electrophysiological study [8], we observed that bath-applied Tat increased Ca2+ influx through L-channels in pyramidal cells (the neuronal type that constitutes 80–90% of PFC neurophil [19]). In the present study, we found a significant increase in the number of Cav1.2-ir cells in the mPFC from Tat-exposed rats. Although the type of cell(s) that showed Cav1.2-ir was not definitively identified, the large size and the layer location are also consistent with the pyramidal neuron profile. Whether L-channel upregulation can be attributed to increased expression/trafficking of the L-channels in the cells requires further investigation. Astrocytes also express L-channels, and the increased expression of cells positive for Cav1.2-ir that we observed may reflect enhanced expression on astroglia and/or increases in the number of infiltrating monocytes/ macrophages.

Astrogliosis is consistently reported in HIV-1 infection [20]. In rats, a single Tat injection into the Str increases GFAP-ir cells at 7 days, but is absent at 30 days after injection [21]. Our results showed an increase in GFAP-ir in the mPFC and MC 14 days after Tat injection. We did not detect striatal pathology. This is in contrast to previous studies, where an injection of Tat (50 µg) directly into the Str was reported to increase GFAP-ir and cause cell death within striatal regions [21]. Alternatively, repeated intracerebroventricular injections may be sufficient to cause gliosis in the Str, as reported previously [22].

Stereological assessments of NeuN-ir cells indicate that, despite the increased number of L-channel-expressing cells and astrogliosis, transient exposure to Tat in vivo did not cause neuronal loss in any brain regions investigated. However, the absence of detectable neuron loss does not rule out the possibility that mPFC cells may have been damaged by Tat and could progressively lead to apoptosis with longer withdrawal, longer exposure, or larger/repeated doses. We did observe an enlargement of Tat-injected ventricles (but not the contralateral ventricle or following vehicle injection). This might indicate atrophy in neuronal processes.

Conclusion

These findings indicate that the L-channel upregulation may be a reversible prelude to neurodegeneration in the mPFC, and overactivated L-channels could be a therapeutic target for treating HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders. Tat infiltration into the CNS is capable of inducing a variety of pathophysiological effects on neurons and non-neuronal cells. It is likely that such dysregulation would be cumulative in the CNS of an HIV+ individual in which the neurons would experience continuous viral protein expression. As the production of HIV-1 proteins (including Tat) is not significantly impacted by currently available antiretroviral therapies [6], it is likely that such dysregulation contributes to the profound pathology in the brain associated with later stages of HIV infection [5]. Adjuvant therapies targeting the sublethal dysregulation in neurons and non-neuronal cells that occur during the early stages of HIV-1 infection may delay or mitigate later neurodegeneration.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank USPHSG #DA 026746, #DA 033206, the Daniel F. and Ada L. Rice Foundation, Peter F. McManus Charitable Trust, and the Center for Compulsive Behavior and Addiction at Rush University.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Ozdener H. Molecular mechanisms of HIV-1 associated neurodegeneration. J Biosci. 2005;30:391–405. doi: 10.1007/BF02703676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gonzalez-Scarano F, Martin-Garcia J. The neuropathogenesis of AIDS. Nat Rev Immunol. 2005;5:69–81. doi: 10.1038/nri1527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Clifford DB. HIV-associated neurocognitive disease continues in the antiretroviral era. Top HIV Med. 2008;16:94–98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Clements JE, Gama L, Graham DR, Mankowski JL, Zink MC. A simian immunodeficiency virus macaque model of highly active antiretroviral treatment: viral latency in the periphery and the central nervous system. Curr Opin HIV AIDS. 2011;6:37–42. doi: 10.1097/COH.0b013e3283412413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ferris MJ, Mactutus CF, Booze RM. Neurotoxic profiles of HIV, psychostimulant drugs of abuse, and their concerted effect on the brain: current status of dopamine system vulnerability in neuroAIDS. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2008;32:883–909. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2008.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li W, Li G, Steiner J, Nath A. Role of Tat protein in HIV neuropathogenesis. Neurotox Res. 2009;16:205–220. doi: 10.1007/s12640-009-9047-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cheng J, Nath A, Knudsen B, Hochman S, Geiger JD, Ma M, et al. Neuronal excitatory properties of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Tat protein. Neuroscience. 1998;82:97–106. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(97)00174-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hu X-T, Al-Harthi L, Napier TC. Increased Ca2+ influx and pathophysiological mechanisms underlying the excitotoxicity of HIV-1 Tat. J Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 2011;6:S50. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhou BY, Liu Y, Kim B, Xiao Y, He JJ. Astrocyte activation and dysfunction and neuron death by HIV-1 Tat expression in astrocytes. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2004;27:296–305. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2004.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nath A, Conant K, Chen P, Scott C, Major E. Transient exposure to HIV-1 Tat protein results in cytokine production in macrophages and astrocytes: a hit and run phenomenon. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:17098–17102. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.24.17098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hille B. Ionic channels of excitable membranes. New York: Skyscrape Inc; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 12.MacVicar BA. Voltage-dependent calcium channels in glial cells. Science. 1984;226:1345–1347. doi: 10.1126/science.6095454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Paxinos G, Watson C. The rat brain in stereotaxic coordinates. New York: Academic Press; 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rademacher DJ, Napier TC, Meredith GE. Context modulates the expression of conditioned motor sensitization, cellular activation and synaptophysin immunoreactivity. Eur J Neurosci. 2007;26:2661–2668. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2007.05895.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kalman M, Hajos F. Distribution of glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP)-immunoreactive astrocytes in the rat brain. I. Forebrain. Exp Brain Res. 1989;78:147–163. doi: 10.1007/BF00230694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McBride JL, During MJ, Wuu J, Chen EY, Leurgans SE, Kordower JH. Structural and functional neuroprotection in a rat model of Huntington’s disease by viral gene transfer of GDNF. Exp Neurol. 2003;181:213–223. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4886(03)00044-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hegg CC, Hu S, Peterson PK, Thayer SA. Beta-chemokines and human immunodeficiency virus type-1 proteins evoke intracellular calcium increases in human microglia. Neuroscience. 2000;98:191–199. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(00)00101-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bonavia R, Bajetto A, Barbero S, Albini A, Noonan DM, Schettini G. HIV-1 Tat causes apoptotic death and calcium homeostasis alterations in rat neurons. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2001;288:301–308. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.5743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yuste R. Origin and classification of neocortical interneurons. Neuron. 2005;48:524–527. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brack-Werner R. Astrocytes: HIV cellular reservoirs and important participants in neuropathogenesis. AIDS. 1999;13:1–22. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199901140-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Aksenov MY, Hasselrot U, Wu G, Nath A, Anderson C, Mactutus C, et al. Temporal relationships between HIV-1 Tat-induced neuronal degeneration, OX-42 immunoreactivity, reactive astrocytosis, and protein oxidation in the rat striatum. Brain Res. 2003;987:1–9. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(03)03194-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jones M, Olafson K, Del Bigio MR, Peeling J, Nath A. Intraventricular injection of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) tat protein causes inflammation, gliosis, apoptosis, and ventricular enlargement. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 1998;57:563–570. doi: 10.1097/00005072-199806000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]