Abstract

Aims: Abnormal accumulation of α-synuclein aggregates is one of the key pathological features of many neurodegenerative movement disorders and dementias. These pathological aggregates propagate into larger brain regions as the disease progresses, with the associated clinical symptoms becoming increasingly severe and complex. However, the factors that induce α-synuclein aggregation and spreading of the aggregates remain elusive. Herein, we have evaluated the effects of the major lipid peroxidation byproduct 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal (HNE) on α-synuclein oligomerization and cell-to-cell transmission of this protein. Results: Incubation with HNE promoted the oligomerization of recombinant human α-synuclein via adduct formation at the lysine and histidine residues. HNE-induced α-synuclein oligomers evidence a little β-sheet structure and are distinct from amyloid fibrils at both conformation and ultrastructure levels. Nevertheless, the HNE-induced oligomers are capable of seeding the amyloidogenesis of monomeric α-synuclein under in vitro conditions. When neuronal cells were treated with HNE, both the translocation of α-synuclein into vesicles and the release of this protein from cells were increased. Neuronal cells can internalize HNE-modified α-synuclein oligomers, and HNE treatment increased the cell-to-cell transfer of α-synuclein proteins. Innovation and Conclusion: These results indicate that HNE induces the oligomerization of α-synuclein through covalent modification and promotes the cell-to-cell transfer of seeding-capable oligomers, thereby contributing to both the initiation and spread of α-synuclein aggregates. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 18, 770–783.

Introduction

Intracytoplasmic deposition of α-synuclein aggregates is a hallmark pathological feature of a group of neurological disorders, including Parkinson's disease (PD), dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB), multiple system atrophy, and Lewy body variant of Alzheimer's disease (17). Missense mutations in SNCA, the gene encoding for α-synuclein, and the multiplication of the chromosomal region containing SNCA have been linked to familial types of PD (14). Further, genome-wide association studies have demonstrated a significant association of SNCA with idiopathic PD (45, 47). Common outcome of these genetic variations is an increased aggregation (20). Studies in various animal models corroborate the notion that α-synuclein-induced neurological diseases are closely related with the aggregation of this protein (39). The types of aggregates responsible for these diseases have not been identified.

Innovation.

A large body of evidence suggests that aggregation of specific proteins and spread of these aggregates within the brain is critical for disease initiation and progression in major neurodegenerative diseases. However, the relationship between aggregate spread and common risk factors for neurodegenerative diseases, such as oxidative stresses, remains elusive. Our results suggest that early neuropathological lipid modifications induce α-synuclein oligomerization and promote the cell-to-cell transfer of seeding-capable oligomers, thereby contributing to both the initiation and spread of aggregates. Therefore, by preventing lipoxidation, one could regulate the abnormal modification and aggregation of α-synuclein, and thereby delay the pathogenesis of Lewy body diseases.

α-Synuclein deposition initially occurs in a few discrete regions and, as the disease progresses, it spreads into larger brain regions. This has been best characterized in PD, in which Lewy bodies initially appear in the lower brainstem, spread through the midbrain and mesocortex, and ultimately affect the neocortex (3). It has also been demonstrated that in PD patients who received mesencephalic transplants, Lewy bodies were shown to have propagated from the host to the grafted tissues (21, 22, 37). Recent studies regarding the basic biology of α-synuclein have suggested the presence of a novel mechanism for aggregate spreading. A small amount of α-synuclein can be released from neuronal cells via unconventional exocytosis (19, 27), which may include exosome-associated exocytosis (13). A significant portion of the released α-synuclein occurs as oligomeric aggregates, and this release is increased under protein misfolding stress conditions (19). Extracellular α-synuclein aggregates can be internalized into cells via endocytosis (29). Based on these properties, direct cell-to-cell transfer of α-synuclein has been demonstrated in cell cultures and animal models (11, 32). However, the factors that influence the intercellular spread of the aggregates have yet to be determined.

α-Synuclein can bind to biological membranes, and the aggregation propensity of the protein is modulated by lipid molecules (1). 4-Hydroxy-2-nonenal (HNE)–modified proteins are accumulated in the brainstem and cortical-type Lewy bodies in PD and DLB (5, 52), as well as in glial and neuronal inclusion bodies in multiple system atrophy (46). Additionally, the modification of α-synuclein by malondialdehyde, another common lipid peroxidation product, was observed in the frontal cortices and the substantia nigra in PD and DLB patients (7). Lipoxidative damages represented by protein adducts with HNE and malondialdehyde were shown to be increased in incidental Lewy body disease, thereby suggesting that lipid peroxidation and the resultant protein modification occur in the early stages of parkinsonian neuropathology (8). HNE is present at low micromolar concentrations in normal brains; however, in pathogenic conditions, it can increase up to 5 mM (49). Herein, we attempted to determine the manner in which the lipid peroxidation byproduct HNE affects α-synuclein oligomerization and the cell-to-cell transfer of this protein. We showed that the covalent modification of α-synuclein with HNE induced the formation of seeding-capable oligomers. HNE treatment administered to neuronal cells increased the secretion of α-synuclein, and thereby promoted the intercellular transfer of this protein.

Results

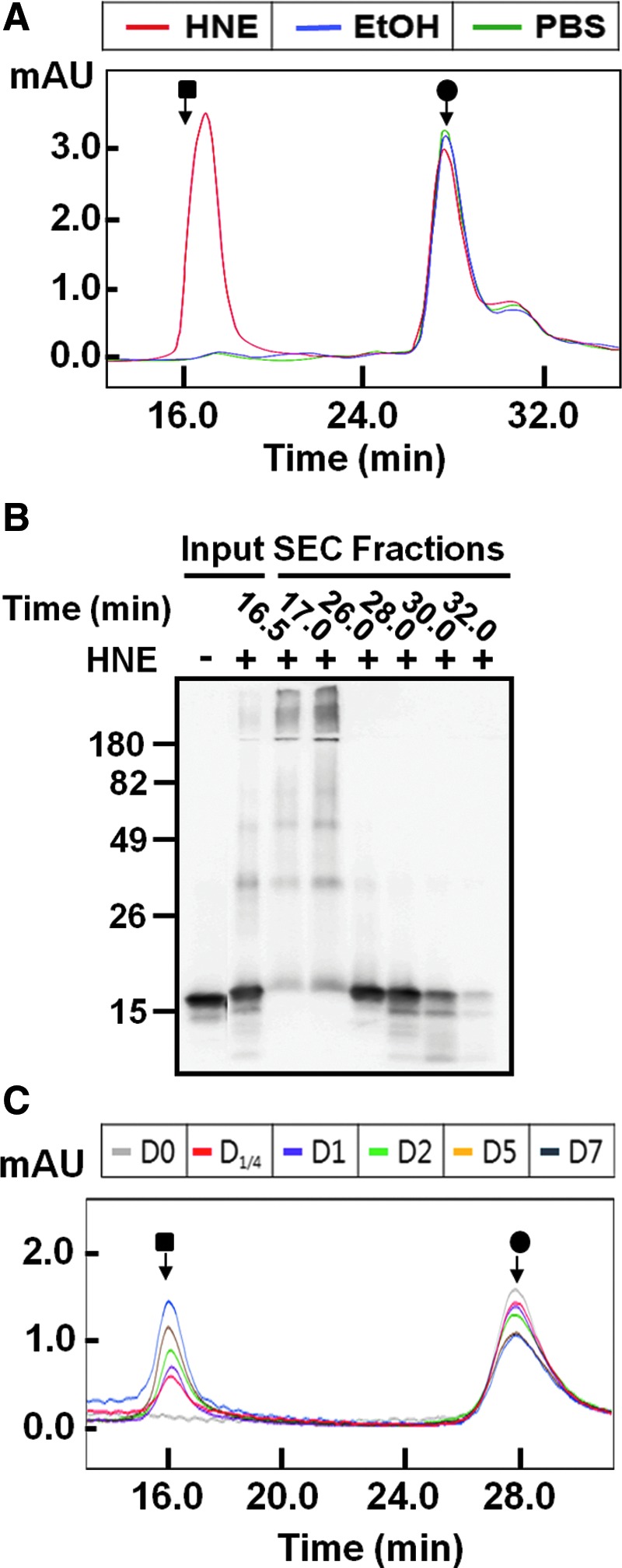

To evaluate the effects of HNE on α-synuclein oligomerization, human recombinant α-synuclein (70 μM) was incubated with 1.4 mM HNE, 2.19% (v/v) ethanol (vehicle control), or phosphate buffered saline (PBS) for 7 days at 37°C without agitation, and the samples were analyzed using size exclusion chromatography (SEC). Incubation with HNE markedly increased oligomer formation compared with controls (Fig. 1A). Western analysis of the SEC fractions showed that most of the HNE-induced oligomers are sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) stable, while some are dissociated to monomers, dimers, or tetramers (Fig. 1B). This suggests that oligomerization involves various degrees of covalent linkages between monomers. The time course analysis of the oligomerization showed a progressive increase of oligomers as the monomers were consumed (Fig. 1C).

FIG. 1.

Increased oligomerization of α-synuclein by 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal (HNE). (A) Size exclusion column chromatography (SEC) of α-synuclein proteins incubated with HNE (red trace) and an equal volume of ethanol (blue trace) or phosphate buffered saline (green trace) for 7 days. The black square and circle mark the void volume and monomer positions, respectively. (B) Western blot analysis of the SEC fractions. Note that α-synuclein proteins in the void volume fractions are mostly sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)–stable oligomers. (C) Time course of oligomerization. HNE/α-synuclein mixture (70 μM) was incubated for up to 7 days, and the samples were analyzed on SEC at the indicated times. (To see this illustration in color, the reader is referred to the web version of this article at www.liebertpub.com/ars.)

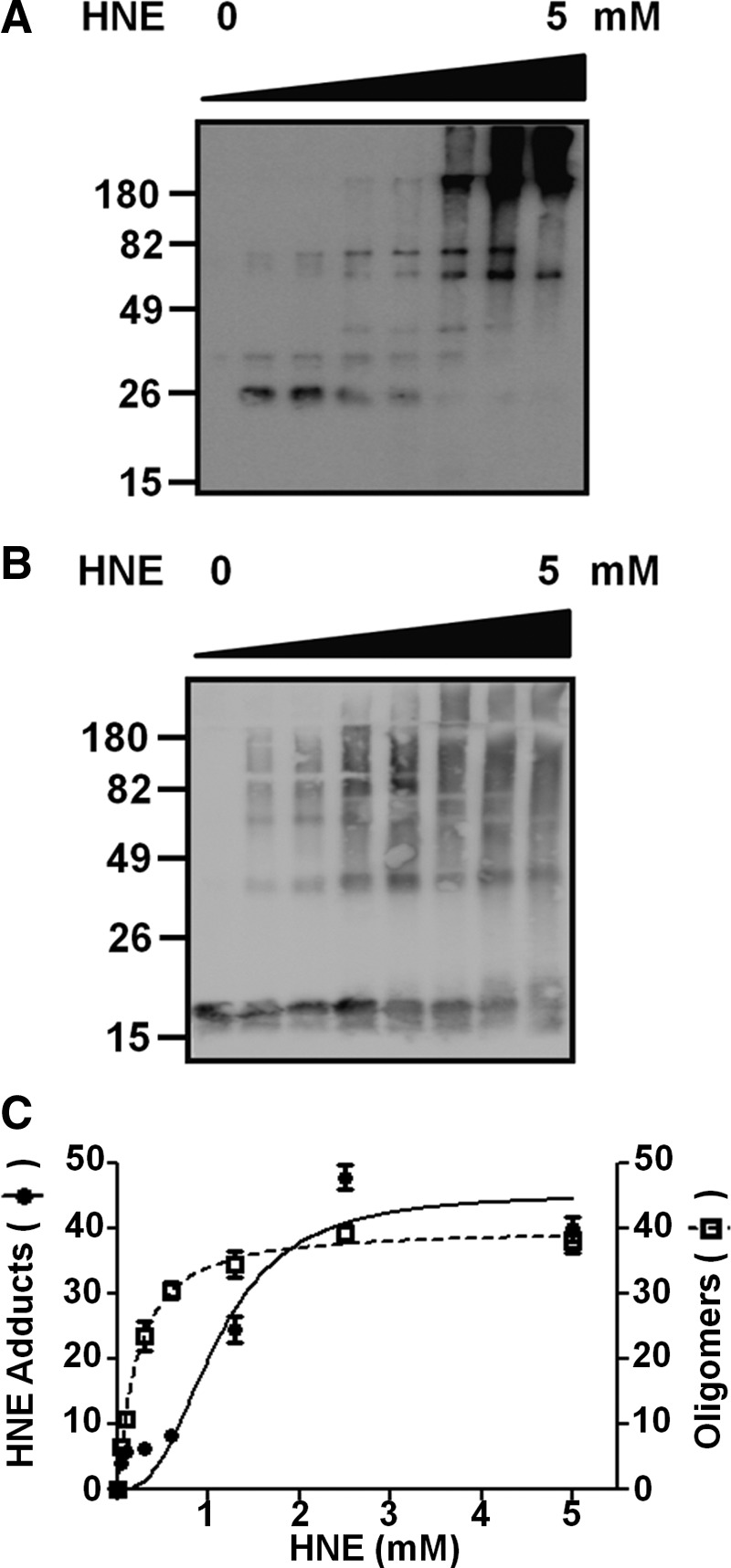

To determine whether α-synuclein is covalently modified with HNE during oligomerization, we incubated α-synuclein with different amounts of HNE and analyzed the reaction products with an antibody specific to HNE-conjugated proteins. Incubation with HNE resulted in α-synuclein-HNE adducts, and the formation of adducts occurs in a manner proportional to the amount of HNE added to the incubation (Fig. 2A, C). The increase in α-synuclein-HNE adducts coincided with SDS-stable oligomer formation (Fig. 2B, C), thereby suggesting that covalent modification with HNE affects oligomerization of α-synuclein. Supporting this notion, at millimolar concentrations of HNE, the HNE-modified forms of α-synuclein are largely oligomeric (Fig. 2A).

FIG. 2.

HNE-α-synuclein adduct formation and oligomerization. (A, B) Western analysis of α-synuclein (70 μM) after incubation with different concentrations of HNE, diluted by a factor of 2 from 5 mM to 0.078125 mM and 0 mM, using either an antibody specific for HNE-protein adducts (A) or an antibody for α-synuclein (B). (C) Quantification of HNE-α-synuclein adducts (closed circles) and α-synuclein oligomers (open squares) from the data in (A) and (B), respectively. For oligomer quantification, monomer bands were excluded from measurement.

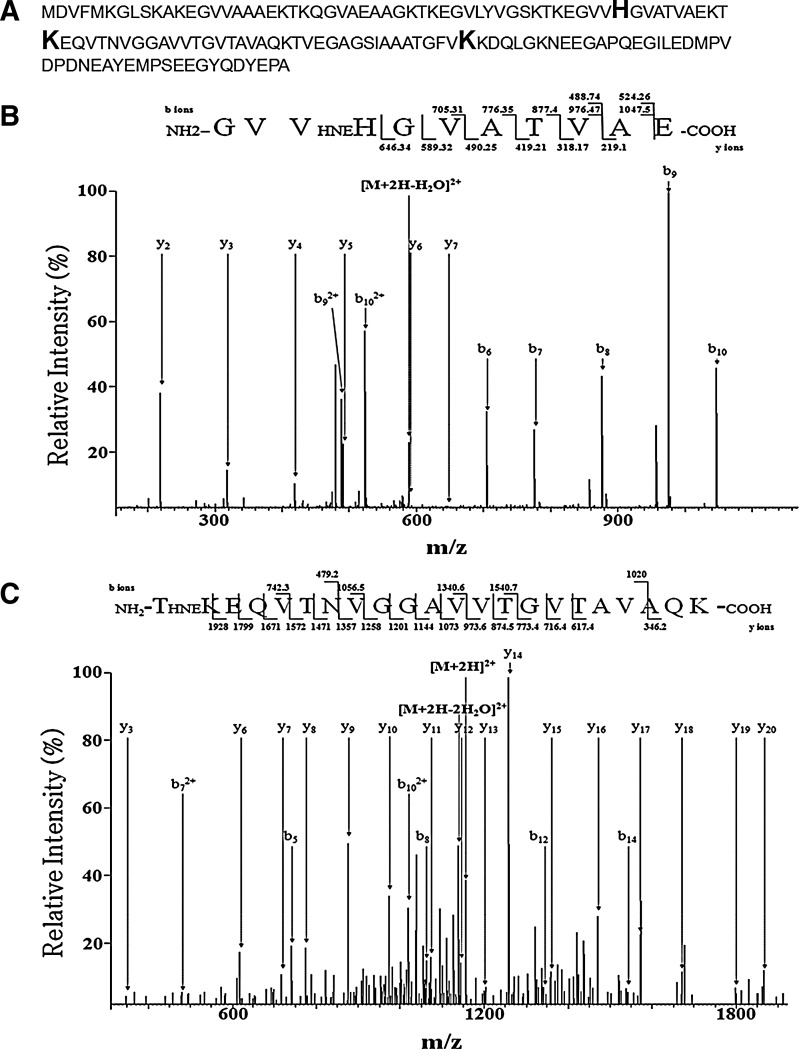

In an effort to further verify the covalent modification of α-synuclein with HNE and to determine the sites of modification, we carried out mass spectrometry with α-synuclein incubated with HNE. These HNE modifications were detected by MS/MS analysis of the peptides with the increase of mass difference corresponding to HNE (+156 Da). We have identified three sites of covalent HNE modification at histidine 50, lysine 60, and lysine 96 (Fig. 3). Figure 3B showed tandem mass spectrum corresponding to α-synuclein peptide 47–57 containing HNE modification. In this spectrum, the C-terminal 51–57 residues were assigned by the presence of a continuous series of unmodified y-ions (y2–y7) from the MS/MS of the peptide with the corresponding mass increase. The HNE modification of His50 was confirmed by the presence of modified fragment ions (b6–b10). Figure 3C showed another tandem mass spectrum corresponding to α-synuclein peptide 60–81 including Lys60 with HNE modification. Similarly, the presence of a continuous series of unmodified y-ions (y3 and y6–y20) and modified fragment ions (b5, b8, b12, and b14) confirmed HNE modification of Lys60 residue. Figure 3D showed the tandem mass spectrum corresponding to α-synuclein peptide 84–97 with the modified Lys96. In this spectrum, the N-terminal 84–95 residues were assigned by the presence of unmodified b-ions (b5–b12) and modified fragment ions (y4, y6, and y8–y10) that confirmed HNE modification of Lys96. To determine the ratio of modification with a quantitative mass spectrometry assay, selective reaction monitoring (SRM) was conducted. For SRM assay, we selected the transition involving peptide sequences, precursor ions, and product ions. Data were acquired by integrating the appropriate peaks for the modified and unmodified peptides, followed by calculation of relative peak areas of transitions for these peptides. The quantitative analysis of mass spectrometry data showed that 18.73% of α-synuclein is modified with HNE at histidine 50 and 18.14% of α-synuclein is modified with HNE at lysine 96.

FIG. 3.

Mass spectrometry of HNE-modified α-synuclein. (A) Amino acid sequence of human α-synuclein. Enlarged bold letters indicate positions modified by HNE. (B–D) MS/MS spectra of peptides contained HNE-modified His50 (B), Lys60 (C), and Lys 96 (D).

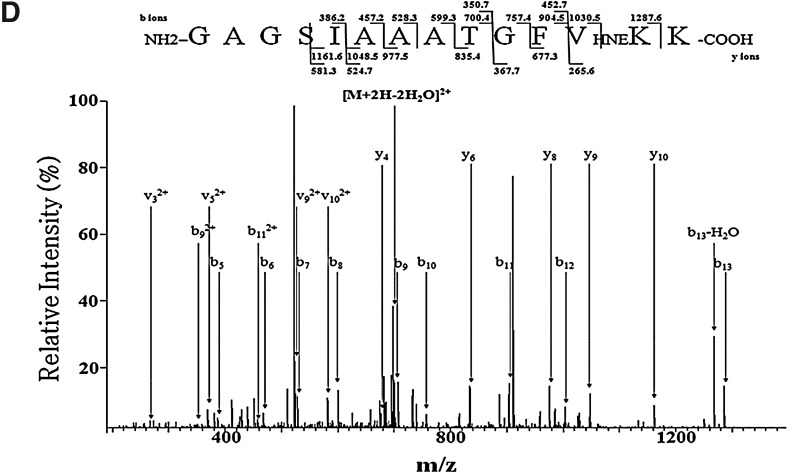

Next, we characterized the conformational properties of HNE-induced α-synuclein oligomers. Circular dichroism (CD) spectroscopy demonstrated that HNE-induced oligomers are largely devoid of stable secondary structures, showing spectra similar to those of monomeric α-synuclein and distinct from β-sheet-rich fibrils (Fig. 4A). To compare the β-sheet contents of HNE-induced oligomers with monomers and fibrils, we measured the molecular ellipticity at the 218 nm, where the β-pleated sheet has negative band (Fig. 4A). HNE-induced oligomers showed the similar molecular ellipticity with monomers, but much less negative value than the fibrils at the 218 nm. We then assessed the binding ability of HNE-induced oligomers to conformation-sensitive reagents, thioflavin T and Fila-4 antibody (42); both of these reagents bind specifically to β-sheet-rich amyloid structures. Consistent with the CD data, HNE-induced oligomers interact with neither thioflavin T nor Fila-4 antibody, whereas both reagents specifically interact with fibrils (Fig. 4B, C). These results suggest that HNE-induced α-synuclein oligomers are assembled without undergoing drastic conformational changes.

FIG. 4.

Analysis of conformation of HNE-induced α-synuclein oligomers. (A) Circular dichroism spectroscopy. α-Synuclein monomers (solid line), HNE-induced oligomers (interrupted line), and fibrils (interrupted line with spots). On the right, the graph represents the molecular ellipticities at 218 nm of α-synuclein monomers, HNE-induced oligomers, and fibrils. (B) Thioflavin T binding assay with α-synuclein monomers (M), fibrils (F), and HNE-induced oligomers (HNE-O). (C) Dot blot analysis using a conformation-specific antibody, Fila-4, which recognizes β-sheet-rich α-synuclein.

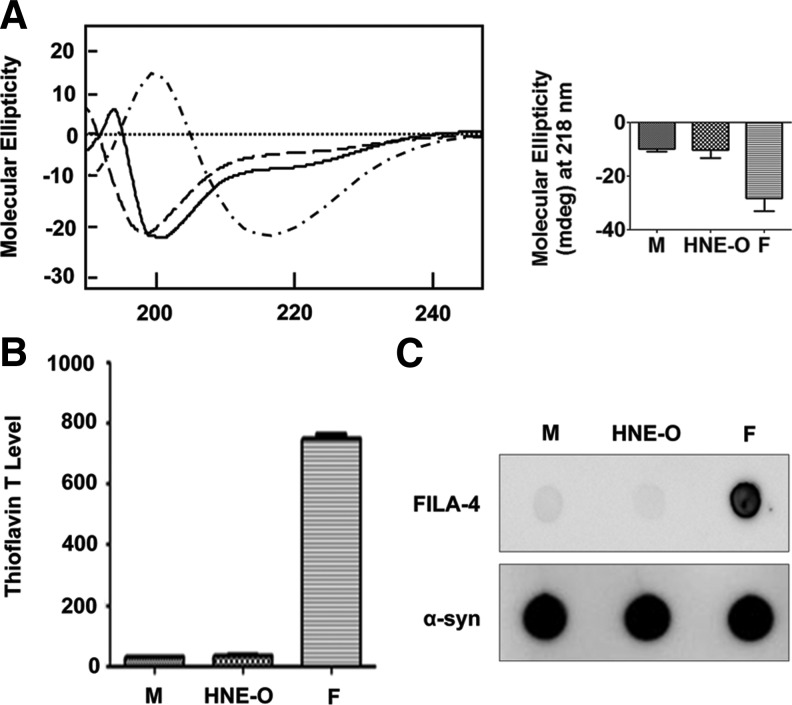

The ultrastructural characteristics of HNE-induced oligomers were analyzed using electron microscopy and atomic force microscopy. HNE-induced α-synuclein oligomers are heterogeneous in shape and size, while images obtained from HNE alone showed little discernible structure (Supplementary Fig. 1; Supplementary Data are available online at www.liebertpub.com/ars). Most of the oligomeric species can be categorized into three groups based on their shapes: spherical, curvilinear, and ring-like oligomers (Fig. 5). Electron microscopy and atomic force microscopy generated virtually identical results.

FIG. 5.

Ultrastructural analysis of HNE-induced α-synuclein oligomers. (A) Atomic force microscopy. (B) Electron microscopy. Scale bar: 200 nm. Oligomer images in white rectangles on the left images are enlarged in the tables on the right. (To see this illustration in color, the reader is referred to the web version of this article at www.liebertpub.com/ars.)

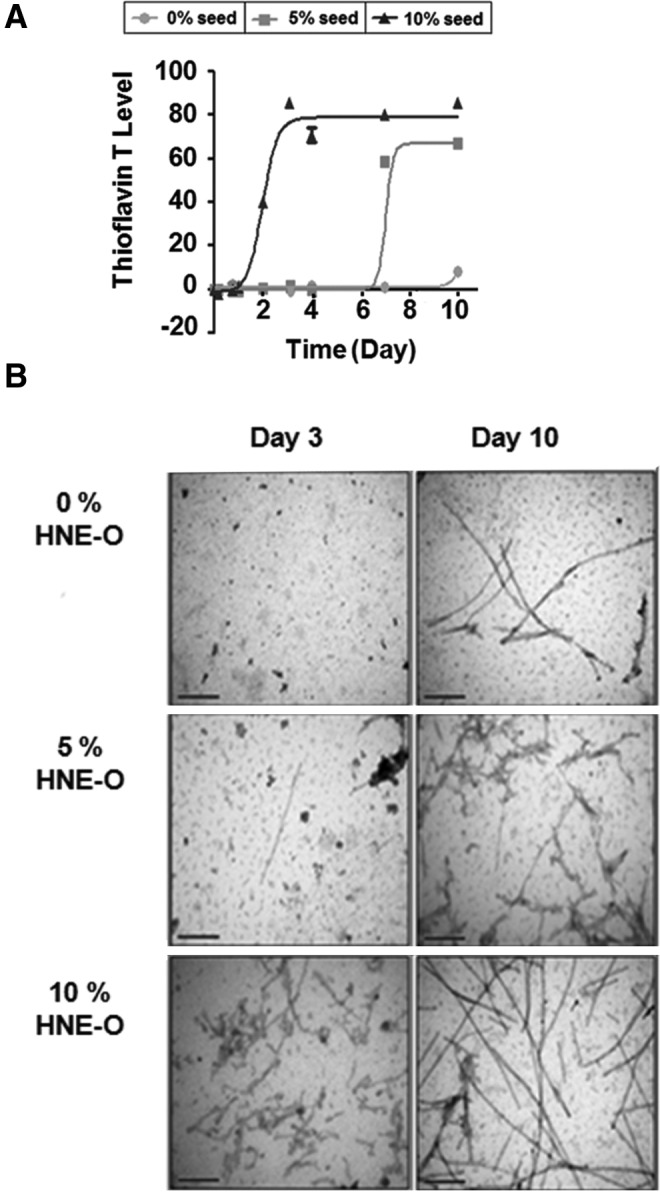

We next attempted to determine whether HNE-induced oligomers can function as seeds for the aggregation of monomeric α-synuclein. Seventy micromoles of α-synuclein containing 0%, 5%, or 10% of HNE-induced oligomers was incubated with agitation for up to 10 days, and fibrillation kinetics was measured using thioflavin T fluorescence. The addition of HNE-induced oligomers significantly accelerated the fibrillation of α-synuclein, reducing the lag phase from ∼10 days unseeded to 4 days with 5% seed and to 1 day with 10% seed (Fig. 6A). These kinetic measurements correlate with electron microscopic data showing faster and more abundant appearance of fibrils with higher amounts of HNE-induced oligomers (Fig. 6B). Therefore, HNE-induced oligomers are capable of seeding the aggregation of the native α-synuclein.

FIG. 6.

Seeding of α-synuclein fibrillation by HNE-induced oligomers. (A) Thioflavin T binding assay. Different amounts of HNE-induced oligomers (0%, circle; 5%, square; 10%, triangle) were added to 70 μM of α-synuclein monomers, and fibrillation was measured by thioflavin T over time. (B) Electron microscopy of samples in (A) at indicated times. Scale bars: 200 nm.

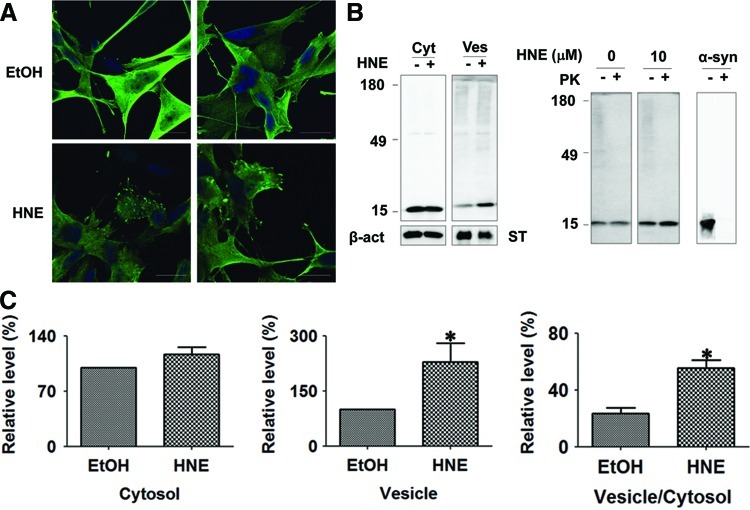

To evaluate the effects of HNE on α-synuclein in neuronal cells, we ectopically expressed α-synuclein in differentiated SH-SY5Y human neuroblastoma cells and treated the cells with 10 μM HNE or with the same volume of ethanol as a vehicle control. Immunofluorescence microscopy showed that cells treated with HNE exhibited a vesicular pattern of α-synuclein more frequently than ethanol-treated cells (Fig. 7A). The vesicular localization of α-synuclein was confirmed when cellular vesicles were isolated via flotation centrifugation; HNE treatment increased the amounts of α-synuclein in the vesicle fractions (Fig. 7B, C). Vesicular α-synuclein was resistant to proteinase K digestion, while the monomeric recombinant α-synuclein was completely digested under the same condition, validating the presence of the protein inside the vesicles (Fig. 7B). Collectively, these results indicate that increases in cellular HNE concentration result in increased α-synuclein translocation from the cytosol to vesicle inside.

FIG. 7.

HNE promotes the translocation of α-synuclein into vesicles in neuronal cells. (A) Immunofluorescence microscopy. Differentiated SH-SY5Y human neuroblastoma cells overexpressing α-synuclein were treated with either ethanol (top images) or 10 μM HNE (bottom images) for 2 days. Green: α-synuclein; blue: nuclei. Scale bars: 20 μm. (B) Vesicle fractionation. Differentiated SH-SY5Y cells overexpressing α-synuclein were treated with either ethanol (−) or 10 μM HNE (+), and vesicles were separated from the cytosol via flotation centrifugation (β-act: β-actin; ST: synaptotagmin). Right panel: vesicle preparations and recombinant α-synuclein monomers (α-syn) were subjected to proteinase K digestion to confirm the intravesicular localization of α-synuclein. (C) Levels of α-synuclein in the cytosol and vesicles. The Western data as shown in (B) were quantified. The data were normalized by the levels of β-actin (cytosol) and synaptotagmin (vesicle). Relative values were obtained by setting one of the control values as being 100 (n=3, *p<0.05). (To see this illustration in color, the reader is referred to the web version of this article at www.liebertpub.com/ars.)

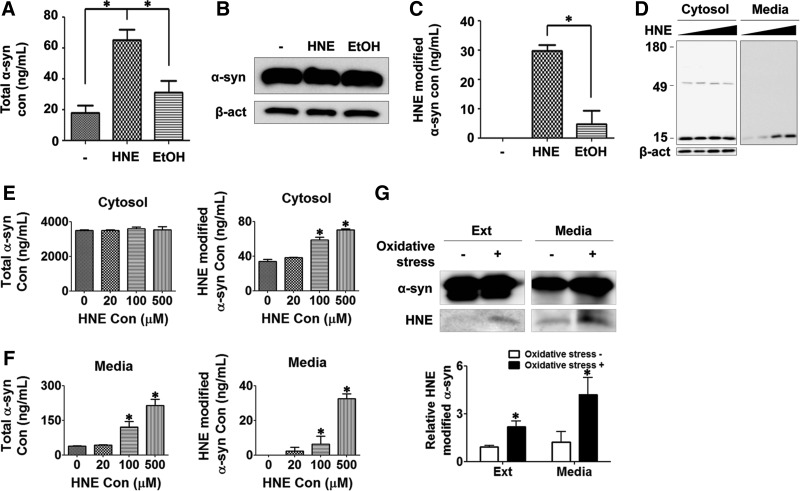

Previously, we suggested that some of the vesicular α-synuclein is released from cells via exocytosis (27). Increased vesicular localization of α-synuclein upon treatment with HNE prompted us to evaluate whether the same treatment increases the release of the protein. The amounts of α-synuclein in cell extracts and the culture media were measured via Western blotting and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), respectively, in differentiated SH-SY5Y cells expressing α-synuclein. HNE-treated cells released significantly increased amounts of α-synuclein compared with the untreated and ethanol-treated cells (Fig. 8A). In contrast, the amounts of cytoplasmic α-synuclein remained largely unchanged (Fig. 8B). To measure the amounts of HNE-modified α-synuclein in the culture media, we established a specific ELISA system using antibodies to α-synuclein and HNE-conjugated proteins. This ELISA system only recognized HNE-modified α-synuclein, and did not recognize unmodified α-synuclein or HNE-modified DJ-1 (Supplementary Fig. 2). This ELISA showed that approximately half the amount of released α-synuclein was HNE modified upon HNE treatment, whereas no or very little HNE-modified α-synuclein was detected in the culture media of untreated and ethanol-treated cells (Fig. 8C). The amounts of HNE-modified α-synuclein in the culture media of HNE-treated cells roughly equal the increment of the total released α-synuclein upon HNE treatment, thus suggesting that HNE modification is the direct cause of increased secretion (Fig. 8A, C).

FIG. 8.

Increased secretion of α-synuclein from HNE-treated cells. (A) Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) of secreted α-synuclein in culture media of differentiated SH-SY5Y cells overexpressing α-synuclein (n=3, *p<0.05). (B) Western blotting of cellular α-synuclein in cell lysates. (C) ELISA analysis of HNE-modified α-synuclein in the culture media (n=3, *p<0.05). (D) Western blotting of the endogenous α-synuclein in the cytosol and culture media of primary mouse cortical neurons after incubation with different concentrations of HNE, diluted by a factor of 5 from 500 μM to 20 μM and 0 μM. (E) ELISA analysis of the total α-synuclein and HNE-modified α-synuclein in the cytosol of primary cortical neurons treated with HNE. (F) ELISA analysis of the total α-synuclein and HNE-modified α-synuclein in culture media of primary cortical neurons treated with HNE. (G) Cells overexpressing his-tagged α-synuclein were incubated with 100 μM hydrogen peroxide and 1 mM iron sulfate for 2 days, and α-synuclein proteins were pulled down from the cell lysates and culture media and analyzed via Western blotting with α-synuclein antibody and HNE-adduct antibody. The y-axis of the graph indicates the fold increase of HNE-modified α-synuclein relative to the level of HNE-modified α-synuclein in control cell extract (n=3, *p<0.05; ext: cell extract).

To verify the effects of HNE on the endogenously expressed α-synuclein, mouse primary cortical neurons were incubated with different concentrations of HNE, and the endogenous α-synuclein proteins were analyzed in the cell extracts and culture medium. HNE treatment did not affect the expression levels of α-synuclein; however, it increased the modification with HNE and secretion of the endogenous α-synuclein in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 8D–F), validating the role of HNE in modification of α-synuclein in a physiologically relevant condition.

To assess the role of endogenous HNE, differentiated SH-SY5Y cells expressing Myc/His-tagged α-synuclein were subjected to oxidative stress with hydrogen peroxide and ferrous sulfate, and α-synuclein modification was analyzed with mass spectrometry. HNE modification at lysine 96 was detected in α-synuclein proteins isolated from both cell extracts and culture medium (Supplementary Fig. 3). However, HNE modification was not detected at other sites, suggesting that lysine 96 is the major HNE modification site under oxidative stress conditions in cells. Quantitative pull-down/Western analysis showed that HNE modification in α-synuclein was increased not only in the cytoplasm but also in the culture medium upon general oxidative stress (Fig. 8G). Under our oxidative stress condition, significant cell death was not observed (Supplementary Fig. 4). These results indicate that α-synuclein is covalently modified with endogenous HNE under oxidative stress conditions, and as a result, secretion of the modified α-synuclein is increased.

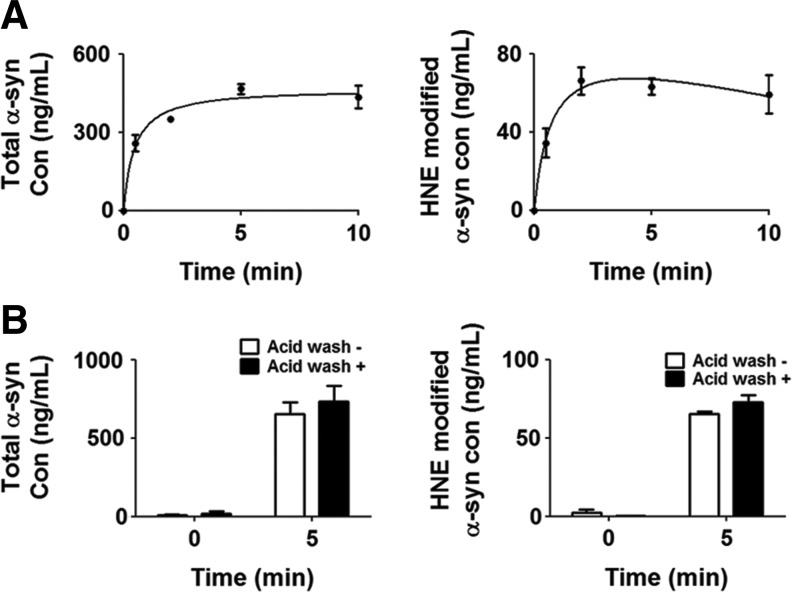

Cells can internalize extracellular α-synuclein. In an effort to determine whether cells internalize HNE-induced α-synuclein oligomers, differentiated SH-SY5Y cells were incubated in the medium containing 1 μM myc/His-tagged α-synuclein preincubated with HNE. HNE-induced α-synuclein oligomers were rapidly internalized into the cells, reaching the maximum level at ∼2 min (Fig. 9A). These high-molecular-weight oligomers were present in the cell lysates even after an acid wash, indicating complete internalization of the oligomers rather than cell surface binding (Fig. 9B).

FIG. 9.

Internalization of HNE-induced α-synuclein oligomers into differentiated SH-SY5Y cells. (A) Cells were incubated with 1 μM α-synuclein preincubated with HNE for indicated times, and cell lysates were analyzed with ELISA for the total α-synuclein and HNE-modified α-synuclein (n=3). (B) Removal of surface-bound proteins. Cells were treated as in (A) for 5 min and washed with 2 N hydrochloric acid to remove surface-bound proteins. Internalized α-synuclein was analyzed via ELISA for the total α-synuclein and HNE-modified α-synuclein (n=3).

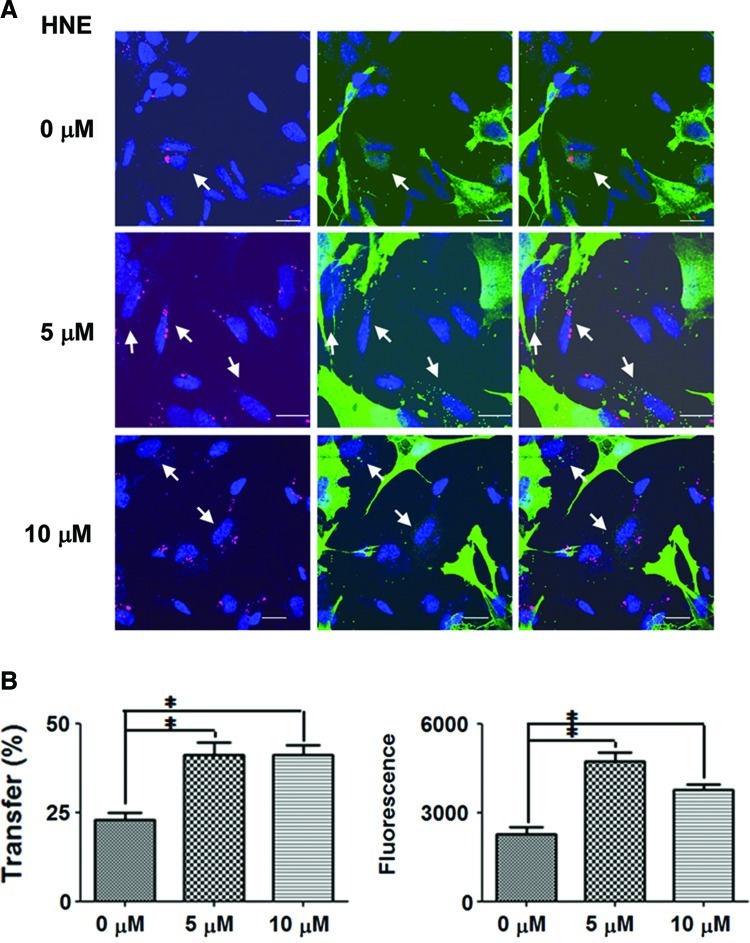

Based on the results just discussed, we assessed the possibility that HNE promotes the cell-to-cell transfer of α-synuclein. We conducted a coculture experiment, in which differentiated SH-SY5Y cells ectopically expressing α-synuclein (donor) were cultured with the same type of cells without ectopic α-synuclein expression (recipient) (11). The recipient cells were labeled with a red fluorescent dye. In the control culture with ethanol, ∼22% of recipient cells evidenced transferred α-synuclein. The transfer was increased to 42.06% and 40.52%, respectively, in the cultures with 5 μM and 10 μM HNE (Fig. 10). The intensity of fluorescence per recipient cells, which represents the amount of transferred α-synuclein, was also increased by 2.1-fold in the presence of 5 μM HNE.

FIG. 10.

HNE promotes cell-to-cell transfer of α-synuclein. (A) Differentiated SH-SY5Y cells overexpressing α-synuclein (donor cells with α-synuclein staining in the entire cytoplasm; green) were cocultured with recipient cells without ectopic expression of α-synuclein (labeled with Qtracker; red). Green dots in the recipient cells represent transferred α-synuclein (arrows). Blue: nuclei. Scale bar: 20 μm. (B) Quantification of cell-to-cell transfer. Graph on the left: percent recipient cells with transferred α-synuclein (n=4, *p<0.05). Three hundred cells were analyzed in each experiment. Graph on the right: green fluorescence intensity per μm2 in the recipient cells (n=4, *p<0.05). Three hundred cells were analyzed in each experiment.

Discussion

α-Synuclein is a soluble cytosolic protein, but also capable of dynamic reversible interactions with membranes. A significant body of evidence suggests that the membrane binding ability is functionally important. The presynaptic localization of α-synuclein requires membrane binding of this protein and is regulated by synaptic activity (16). A recent study suggested that α-synuclein functions to maintain continuous presynaptic soluble N-ethylmaleimide sensitive factor attachment protein receptors-complex assembly (4). On the other hand, interaction with lipid molecules alters the aggregation properties of α-synuclein. In particular, interaction with polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) promoted the self-assembly of this protein (43). Among lipid molecules, PUFAs are relatively vulnerable to attacks by reactive oxygen species, and upon oxidation, produce reactive aldehydes, such as HNE, acrolyn, and malondialdehyde (49). These aldehydes can diffuse within the membranes and attack membrane proteins, generating various forms of covalent adducts. Therefore, covalent modifications by peroxidation byproducts might be the underlying mechanism by which PUFAs promote α-synuclein aggregation. The current study demonstrates that the covalent modification of α-synuclein with HNE increases the formation of seeding-capable α-synuclein oligomers, and the treatment of cells with HNE induces increased release of the HNE-conjugated α-synuclein from cells, thereby promoting cell-to-cell transfer of this protein. Therefore, under oxidative stresses that affect lipid molecules, lipid peroxidation byproducts might not only affect α-synuclein modification and oligomerization in individual neurons intrinsically, but also promote the spread of the aggregates into neighboring cells.

Mass spectrometry demonstrated that α-synuclein is covalently modified by HNE via Michael addition, which generates adducts through the side chains of cysteine, histidine, and lysine (49). α-Synuclein contains one histidine, 15 lysines, and no cysteine. A previous study reported that HNE modified α-synuclein at a single histidine residue at position 50 (48). In the present study, we have identified two lysine residues at positions 60 and 96 as the sites of modification, in addition to histidine 50. Among these sites, lysine 96 has been shown to be modified by HNE upon exposure to general oxidative stress in cells both in the current and the previous studies (19), thus validating the physiological relevance of HNE modification of α-synuclein. Lysine 96 is one of the two lysine residues that are sumoylated (23). Sumoylation has been shown to increase the solubility of α-synuclein, thereby suppressing the aggregation of the protein (23). It would be intriguing to assess whether HNE modification at lysine 96 competes with sumoylation, thereby affecting the sumoylation-mediated regulation of protein solubility.

It is worth noting that α-synuclein preferentially interacts with membrane packing defects (41). Considering that lipid oxidation leads to membrane malformation, the affinity of α-synuclein for defective membranes facilitates the modification of this protein by oxidized lipid byproducts. Based on these findings, one can formulate a working model. Oxidative stresses increase the production of lipid peroxidation byproducts, resulting in membrane defects. To these defective membranes, α-synuclein is recruited and modified by reactive aldehydes, such as HNE. Via this modification, α-synuclein undergoes changes in conformational properties and becomes more prone to aggregation.

The oligomers induced by HNE in our study are distinct from those noted in previous studies. HNE-induced oligomers in the present study are, in large part, covalently connected through intermolecular crosslinks, which is consistent with the results of a previous study (40), but contrasts with another (44). Our HNE-induced oligomers have a minimal secondary structure, whereas the oligomers analyzed in the previous studies are β-sheet rich (40, 44). The ultrastructural morphologies of HNE-induced oligomers are also diverse. Our study describes annular and curvilinear protofibril-like oligomers as well as spherical oligomers, which are similar to the HNE-induced oligomers described previously by Nasstrom et al. (40), whereas another previous study involved mostly spherical oligomers (44). The reason for this discrepancy is not clear. There may have been a subtle difference in buffer compositions, α-synuclein purification conditions, or other incubation conditions. Some of these small differences might have created different patterns of conformational distribution during the incubation, such that the protein responded differently to the same modification. The diversity in the HNE-induced oligomers under in vitro conditions suggests the heterogeneity in oligomeric species that are induced by HNE in the brain, which might pose potential difficulties in controlling them.

The most striking property of HNE-induced oligomers described in the present study that is distinct from the previously described ones is their effects on the fibrillation process. In a previous study, Qin et al. (44) demonstrated that HNE modification of α-synuclein resulted in an inhibition of fibrillation. In another study, Nasstrom et al. (40) showed that HNE-induced oligomers did not form amyloid fibrils even after prolonged incubation. Since this incubation of oligomers was performed in the presence of minimal monomers, the seeding ability of the oligomers could not be evaluated. The discrepancy may be attributed to the amounts of crosslink and conformational flexibility within the resulting oligomers. The HNE-induced oligomers we describe in the current study harbor minimal secondary structures, thereby suggesting that they maintain relatively flexible conformations in assembled states. Because of the flexible conformations and preexisting intermolecular interactions, these oligomers may have an advantage for transformation into amyloid fibrils. On the other hand, the ones with compact and stable secondary structures may be the dead end of an off-pathway aggregation process. Our observation appears to be consistent with the nucleated conformational conversion model of fibrillation (33).

Oligomerization of α-synuclein has been shown to be promoted by several chemical modifiers, such as dopamine and its metabolites (6), baicalein (53), epigallocatechin gallate (12), and rifampicin (36). The oligomers induced by these modifiers are unstructured, off-pathway assembly products. On the other hand, considering their seeding abilities, the HNE-induced oligomers described in the present study appear to be on-pathway intermediates. Therefore, although the overall lack of secondary structure is common to these oligomers, the specific alignment of α-synuclein proteins within each type of oligomer might differ, thereby determining the pathway of aggregation.

The native conformation of α-synuclein is highly relevant to the changes this protein undergoes in pathological conditions and upon HNE modification. Last year, two articles (2, 50) have suggested that the native state of α-synuclein is a helix-rich tetramer. Despite these published works, the native conformation of α-synuclein remains controversial. Earlier this year, an international, multigroup team published an article, counterclaiming that α-synuclein from various sources, including the human central nervous system, human red blood cells, and Escherichia coli, exists predominantly as a disordered monomer (15). We were also not able to obtain tetrameric α-synuclein by employing a nondenaturing purification procedure. The experiment assessing the effects of HNE on conformational changes and aggregation of the tetrameric α-synuclein has to wait until the native states of this protein are clearly defined, perhaps at least until the reliable and consistent purification procedure for the tetramer is established and available.

Abnormal aggregates of α-synuclein spread from brain region to brain region. Recent evidence suggests that this spread can be attributed to the cell-to-cell transfer of α-synuclein aggregates (10, 11, 18). The first step in intercellular α-synuclein transfer is the release of this protein from neuronal cells. Exocytosis of α-synuclein is increased under conditions in which misfolded proteins are accumulated, for example, proteasomal and lysosomal inhibition, increased oxidative stresses, and mitochondrial dysfunction (19). Increased cytoplasmic dopamine concentration also promoted α-synuclein release (31). Consistent with the notion that misfolded α-synuclein is released, relaxed conformation appears to be a requirement for the secretion of this protein (19). Modification by HNE likely induces conformational abnormalities, resulting in increased translocation into vesicles and secretion, as we observed in this study. This result is consistent with the finding that secretion of HNE-modified α-synuclein is increased in cells upon exposure to general oxidative stresses.

Consistent with increased secretion, HNE treatment resulted in the promotion of the cell-to-cell transfer of α-synuclein. It has been demonstrated that α-synuclein aggregates can be transferred to neighboring cells and subsequently induce aggregation, perhaps via a seeded polymerization mechanism (9, 38, 51) or other mechanisms (34, 35). HNE-induced α-synuclein oligomers are capable of seeding in vitro, and therefore, putting our results together, it is tempting to propose the following model. An increase in oxidative stresses leads to lipid peroxidation and generates HNE and other byproducts. These reactive aldehydes subsequently covalently modify α-synuclein, resulting in increased oligomerization and secretion. Finally, secreted HNE-modified oligomers are transferred to neighboring cells and amplify aggregates via seeding in the recipient cells.

HNE-modified proteins are accumulated in the brainstem and cortical-type Lewy bodies in PD and DLB (5, 52), as well as in glial and neuronal inclusion bodies in multiple system atrophy (46). Additionally, the modification of α-synuclein by malondialdehyde, another common lipid peroxidation product, was observed in the frontal cortices and the substantia nigra in PD and DLB patients (7). Lipoxidative damages represented by protein adducts with HNE and malondialdehyde were shown to be increased in incidental Lewy body disease, thereby suggesting that lipid peroxidation and the resultant protein modification occur in the early stages of parkinsonian neuropathology (8). In this context, it is worth noting that α-synuclein aggregation in the membrane fractions, in which intracellular HNE concentration would be high, was greatly reduced by treatment with membrane-permeable antioxidants (24).

Materials and Methods

Materials

Imidazole, isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside, proteinase K, protease inhibitor cocktail, 3,3′,5,5′-tetramethylbenzidine, and Tween20 were purchased from Sigma. HNE was from Cayman Chemical. The following antibodies were used: Anti-Michael-adducts antibody for Western blotting (Calbiochem), Anti-Michael-adducts antibody for ELISA (Abcam), Anti-Myc tag antibody for ELISA (Abcam), α-synuclein antibody (Cell Signal Tech), Fila-4 antibody (gift from Poul Henning Jensen, University of Aarhus, Denmark), and β-actin antibody (Sigma). Antibodies 274 and 62 were produced as previously described (30). Fluorescence dye-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG was obtained from Jackson Immunoresearch Laboratories.

Expression and purification of α-synuclein

The human α-synuclein gene was cloned into pDualGC-mychis expression vector (Stratagene). For the expression of nontagged α-synuclein, the myc and his tag were removed from the vector using a Site Direct Mutagenesis kit (Stratagene). Protein induction and purification was conducted as previously described (31). Briefly, protein expression was induced by 0.1 mM isopropyl B-D-l-thiogalactopyranoside for 3 h at 37°C in E. coli BL21(DE3). Cell lysates in 20 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) were boiled for 15 min and centrifuged for 15 min at 10,000 g. The supernatant was passed through a syringe filter (0.22 μm; Millipore) and injected into Hi-Trap Q FF anion exchange chromatography column (GE Healthcare Bio-Science) for nontagged α-synuclein or into HisTrap affinity chromatography column (GE Healthcare Bio-Science) for his-tagged α-synuclein. Pooled fractions out of these columns were injected into an SEC column (Superdex 200 HR 10/30; GE Healthcare Bio-Science). Fractions containing α-synuclein were pooled and dialyzed against distilled water. The protein concentration was measured via a BCA protein assay (Pierce).

Generation of fibrils and HNE-modified α-synuclein oligomers

For oligomerization, 70 μM of α-synuclein monomer was incubated with 1.4 mM HNE for 7 days at 37°C without agitation. Fibrils were generated as previously described (29). Briefly, 200 μM of α-synuclein monomer was agitated for 2 weeks at 37°C in a shaking incubator (250 rpm). The protein was briefly sonicated and incubated for an additional 7 days. The α-synuclein fibrils were pelleted via ultracentrifugation at 100,000 g for 1 h and then resuspended in PBS.

Size exclusion chromatography

Proteins were passed through a 0.22 μm pore size filter and injected into a Superdex 200 HR 10/30 column using fast protein liquid chromatography. The proteins eluted in phosphate-buffered saline were monitored at 280 nm with a flow rate of 0.5 ml/min.

Western blotting and Dot blots

Western blotting was conducted as previously described (28). For Dot blotting, 5 μg of protein was spotted directly onto nitrocellulose membranes using a Dot blot apparatus (Bio-Rad), and the rest of the procedure was the same as in the Western blotting assays. Images were obtained with an LAS-3000 Luminescent Image Analysis System (FUJIFILM Life Science).

Thioflavin T assay

Protein samples (10 μM in 40 μl volume) were put into a 96-well plate and then 100 mM glycine–sodium hydroxide (NaOH) (pH 8.5) solution containing 10 μM thioflavin T (50 μl) was added to each well. After 5 min of incubation at room temperature, fluorescence was measured at an excitation of 450 nm and emission at 490 nm with a SpectraMax GEMINI EM (Molecular Devices) (31).

CD spectroscopy

Spectra of α-synuclein samples (70 μM in PBS) were recorded from 190 to 250 nm with a step size of 0.1 nm, a bandwidth of 1.0 nm, and an average time of 1 s using a J-810 spectropolarimeter (Jasco). For all spectra, an average of six scans was obtained.

Atomic force microscopy

Protein samples (10 μM) were placed on the mica and left to absorb. The mica was then washed with distilled water and dried prior to analysis with Nano-R2TM atomic force microscopy (Pacific Nano Technology).

Transmission electron microscopy

The protein sample was dropped onto the formvar-coated grid and left to absorb for 5 min. Proteins were negatively stained for 1 min with 10 μl of 0.02% (v/v) uranyl acetate. The grid was then washed with distilled water for 1 min. The protein samples were photographed using a Hitachi H-7560 electron microscope (Hitachi).

Mass spectrometry

Enzymatic digestion and MS/MS analysis of digested peptides were conducted as previously described (19). Briefly, the bands corresponding to α-synuclein were excised from the gels and subjected to sequential digestion with 12.5 ng/μl of sequencing-grade trypsin and Glu-C. The extracted peptides were loaded onto a fused-silica microcapillary column (12 cm×75 μm) packed with C18 resin (5 μm, 200 Å) and separated at a flow rate of 250 nl/min. The column was directly connected to a LTQ™ ion-trap mass spectrometer (Thermo Electron Corporation) equipped with a nanoelectrospray ion source. The acquired MS/MS spectra were searched against a small database consisting of the amino acid sequence of α-synuclein and the Human Protein Reference Database (http://www.hprd.org) having 33,437 human protein sequence entries as of October 2007 using the SEQUEST algorithm (Thermo Fisher Sci.) using the following search parameters: precursor and fragment ion mass tolerances of ± 2 Da and ± 1 Da, respectively; number of missed cleavage sites of 2; oxidation on Met (+16 Da); secondary carbonylation through the HNE attachment on His, Lys, and Arg (+156 Da) as variable modifications. After computation of the search, we validated the MS/MS-based peptide and protein identification using Scaffold 3 (Proteome Software) that is based on probability thresholds. We obtained a list of peptides that were established at a >95% probability according to the Peptide Prophet algorithm. To increase the confidence, the Protein Prophet algorithm was used for protein identifications, which has better than 99% probability and at least two identified unique peptides.

Cell culture and α-synuclein expression

Human neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y cells were cultured and differentiated as described previously (25). For α-synuclein expression, differentiated cells were transduced with adenoviral vector containing cDNA for human α-synuclein (adeno/α-syn) at a multiplicity of infection of 50. For primary cortical neurons, cerebral cortices obtained from embryonic day 16 embryos of pregnant C57/BL6 mouse were incubated with the papain solution HBBS (Hank's buffered salt solution) containing 10 U/ml papain, 0.2 mg/ml cysteine, 0.5 mM ethylenediamine tetraacetic acid, 1 mM calcium chloride, and 0.003 N NaOH), followed by incubation with the trypsin inhibitor solution (minimum essential media with Earl's salts containing 5% fetal bovine serum, 2.5 mg/ml bovine serum albumin, and 2.5 mg/ml trypsin inhibitor). After mechanical dissociation by pipetting and centrifugation, collected cells were resuspendend and plated on the poly-D-lysine/laminin-coated culture dish. Cells were cultured in neurobasal medium (Invitrogen) containing 2% of B-27 supplement (Invitrogen) and 0.5 mM Glutamax-1 (Invitrogen). Culture medium was changed every 3 days.

Preparation of cell extract and conditioned medium

Cells were washed twice in ice-cold PBS and harvested in the extraction buffer (PBS/1% TritonX-100/protease inhibitor cocktail). The extract was subjected to 16,000 g centrifugation to obtain triton-soluble (sup) and -insoluble (pellet) fractions (31). Conditioned medium was centrifuged at 10,000 g to remove cellular debris. Protease inhibitor cocktail was added to the saved supernatants and stored at−80°C prior to further analyses.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

The assay was conducted as previously described (30). Among the antibodies used, Ab274 is specific to human α-synuclein, while Ab62 and syn-1 recognize both human and mouse α-synuclein. For the total human α-synuclein, Ab62 (1 μg/ml) was used as a capture antibody, and biotinylated Ab274 (1 μg/ml) was used as a reporter. For the total mouse α-synuclein, syn-1 (BD Biosciences) and biotinylated Ab62 were used as the capture and reporter antibodies, respectively. To quantify HNE-modified α-synuclein, anti-HNE-Michael adducts (1:500; Abcam) was used as a capture antibody, and biotinylated Ab274 or Ab62 was used as a reporter antibody. For the total myc/his-tagged α-synuclein, anti-myc tag antibody (1:100; Abcam) was used as a capture antibody, and biotinylated Ab62 was used as a reporter antibody.

Vesicle preparation by flotation

The procedure for vesicle preparation has been previously described (27). Cells were harvested with buffer M [10 mM HEPES (4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethane sulfonic acid) (pH 7.2), 10 mM potassium chloride, 1 mM ethylene glycol tetraacetic acid, 250 mM sucrose, and 1% protease inhibitor cocktail]. The cells were disrupted using a dounce homogenizer. The supernatant obtained from a 1000 g spin was subsequently mixed with iodixanol (OPTI-PREP reagent; Invitrogen) to obtain a final concentration of 35%. The mixture was layered under 30% and 5% iodixanol step gradient layers. The mixture was then centrifuged for 2 h at 200,000 g, the vesicles were collected at the interphase between 5% and 30%, and the cytosol fraction was collected from the 35% bottom fraction.

Proteinase K digestion

Proteinase K was added to vesicle fractions at a final concentration of 1 mg/ml, and then incubated for 30 min at 37°C. Phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride was subsequently added to a final concentration of 5 mM to the vesicle fraction to inactivate the enzyme.

Pull-down assay

The human neuroblastoma cells overexpressing myc/his-tagged human α-synuclein was harvested in the extraction buffer (PBS/1% TritonX-100/protease inhibitor cocktail). Triton-soluble fractions were incubated with Talon metal affinity beads (BD Biosciences) for 2 h at 4°C. After removing unbound proteins by three washes, myc/his-tagged human α-synuclein was eluated with 2× Laemmli sample buffer.

Cell-to-cell transfer coculture assay

The recipient cells were labeled with a Qtracker 585 cell labeling kit as previously described (11). The labeled recipient cells were then added to donor SH-SY5Y cells on coverslips infected with α-synuclein adenoviral vector, 1 day postinfection, and cultured for one additional day. The cells were then treated with 10 μM of HNE and grown for 2 days before staining. The procedure for immunofluorescence cell staining was described elsewhere (26). Nuclei were stained with TOPRO-3 iodide (Invitrogen), and coverslips were mounted onto slide glasses using anti-fade reagent (Invitrogen). An Olympus FV1000 confocal laser scanning microscopy (Olympus) was used for observation.

Supplementary Material

Abbreviations Used

- CD

circular dichroism

- DLB

dementia with Lewy bodies

- ELISA

enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

- HNE

4-hydroxy-2-nonenal

- PBS

phosphate buffered saline

- PD

Parkinson's disease

- PUFA

polyunsaturated fatty acid

- SDS

sodium dodecyl sulfate

- SEC

size exclusion chromatography

- SRM

selective reaction monitoring

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Hyung-Sik Won for advising CD data analysis. This work was supported by the Mid-career Research Program (2011-0016465); by the Bio & Medical Technology Development Program (2011-0027751) through NRF grant funded by the Korean Ministry of Education, Science and Technology, Republic of Korea (to S.J.L.); by Seoul R&BD Program (ST090843C092792) (to S.J.L.); and by grants from the WCU program (R33-10128) from the Korean Ministry of Education, Science and Technology (to K.P.K.).

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Auluck PK. Caraveo G. Lindquist S. Alpha-synuclein: membrane interactions and toxicity in Parkinson's disease. Ann Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2010;26:211–233. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.042308.113313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bartels T. Choi JG. Selkoe DJ. Alpha-synuclein occurs physiologically as a helically folded tetramer that resists aggregation. Nature. 2011;477:107–110. doi: 10.1038/nature10324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Braak H. Del Tredici K. Invited article: nervous system pathology in sporadic Parkinson disease. Neurology. 2008;70:1916–1925. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000312279.49272.9f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Burre J. Sharma M. Tsetsenis T. Buchman V. Etherton MR. Sudhof TC. Alpha-synuclein promotes SNARE-complex assembly in vivo and in vitro. Science. 2010;329:1663–1667. doi: 10.1126/science.1195227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Castellani RJ. Perry G. Siedlak SL. Nunomura A. Shimohama S. Zhang J. Montine T. Sayre LM. Smith MA. Hydroxynonenal adducts indicate a role for lipid peroxidation in neocortical and brainstem Lewy bodies in humans. Neurosci Lett. 2002;319:25–28. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(01)02514-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Conway KA. Rochet JC. Bieganski RM. Lansbury PT., Jr Kinetic stabilization of the alpha-synuclein protofibril by a dopamine-alpha-synuclein adduct. Science. 2001;294:1346–1349. doi: 10.1126/science.1063522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dalfo E. Ferrer I. Early alpha-synuclein lipoxidation in neocortex in Lewy body diseases. Neurobiol Aging. 2008;29:408–417. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2006.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dalfo E. Portero-Otin M. Ayala V. Martinez A. Pamplona R. Ferrer I. Evidence of oxidative stress in the neocortex in incidental Lewy body disease. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2005;64:816–830. doi: 10.1097/01.jnen.0000179050.54522.5a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Danzer KM. Haasen D. Karow AR. Moussaud S. Habeck M. Giese A. Kretzschmar H. Hengerer B. Kostka M. Different species of alpha-synuclein oligomers induce calcium influx and seeding. J Neurosci. 2007;27:9220–9232. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2617-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Danzer KM. Ruf WP. Putcha P. Joyner D. Hashimoto T. Glabe C. Hyman BT. McLean PJ. Heat-shock protein 70 modulates toxic extracellular alpha-synuclein oligomers and rescues trans-synaptic toxicity. FASEB J. 2010;25:326–336. doi: 10.1096/fj.10-164624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Desplats P. Lee HJ. Bae EJ. Patrick C. Rockenstein E. Crews L. Spencer B. Masliah E. Lee SJ. Inclusion formation and neuronal cell death through neuron-to-neuron transmission of alpha-synuclein. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:13010–13015. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0903691106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ehrnhoefer DE. Bieschke J. Boeddrich A. Herbst M. Masino L. Lurz R. Engemann S. Pastore A. Wanker EE. EGCG redirects amyloidogenic polypeptides into unstructured, off-pathway oligomers. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2008;15:558–566. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Emmanouilidou E. Melachroinou K. Roumeliotis T. Garbis SD. Ntzouni M. Margaritis LH. Stefanis L. Vekrellis K. Cell-produced alpha-synuclein is secreted in a calcium-dependent manner by exosomes and impacts neuronal survival. J Neurosci. 2010;30:6838–6851. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5699-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Farrer MJ. Genetics of Parkinson disease: paradigm shifts and future prospects. Nat Rev Genet. 2006;7:306–318. doi: 10.1038/nrg1831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fauvet B. Mbefo MK. Fares MB. Desobry C. Michael S. Ardah MT. Tsika E. Coune P. Prudent M. Lion N. Eliezer D. Moore DJ. Schneider B. Aebischer P. El-Agnaf OM. Masliah E. Lashuel HA. Alpha-synuclein in central nervous system and from erythrocytes, mammalian cells, and Escherichia coli exists predominantly as disordered monomer. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:15345–15364. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.318949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fortin DL. Nemani VM. Voglmaier SM. Anthony MD. Ryan TA. Edwards RH. Neural activity controls the synaptic accumulation of {alpha}-synuclein. J Neurosci. 2005;25:10913–10921. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2922-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goedert M. Alpha-synuclein and neurodegenerative diseases. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2001;2:492–501. doi: 10.1038/35081564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hansen C. Angot E. Bergstrom AL. Steiner JA. Pieri L. Paul G. Outeiro TF. Melki R. Kallunki P. Fog K. Li JY. Brundin P. Alpha-synuclein propagates from mouse brain to grafted dopaminergic neurons and seeds aggregation in cultured human cells. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:715–725. doi: 10.1172/JCI43366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jang A. Lee HJ. Suk JE. Jung JW. Kim KP. Lee SJ. Non-classical exocytosis of alpha-synuclein is sensitive to folding states and promoted under stress conditions. J Neurochem. 2010;113:1263–1274. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2010.06695.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim C. Lee S-J. Controlling the mass action of alpha-synuclein in Parkinson's disease. J Neurochem. 2008;107:303–316. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2008.05612.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kordower JH. Chu Y. Hauser RA. Freeman TB. Olanow CW. Lewy body-like pathology in long-term embryonic nigral transplants in Parkinson's disease. Nat Med. 2008;14:504–506. doi: 10.1038/nm1747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kordower JH. Chu Y. Hauser RA. Olanow CW. Freeman TB. Transplanted dopaminergic neurons develop PD pathologic changes: a second case report. Mov Disord. 2008;23:2303–2306. doi: 10.1002/mds.22369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Krumova P. Meulmeester E. Garrido M. Tirard M. Hsiao HH. Bossis G. Urlaub H. Zweckstetter M. Kugler S. Melchior F. Bahr M. Weishaupt JH. Sumoylation inhibits {alpha}-synuclein aggregation and toxicity. J Cell Biol. 2011;194:49–60. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201010117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee H-J. Choi C. Lee S-J. Membrane-bound alpha-synuclein has a high aggregation propensity and the ability to seed the aggregation of the cytosolic form. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:671–678. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M107045200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee H-J. Khoshaghideh F. Patel S. Lee S-J. Clearance of alpha-synuclein oligomeric intermediates via the lysosomal degradation pathway. J Neurosci. 2004;24:1888–1896. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3809-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee H-J. Lee S-J. Characterization of cytoplasmic alpha-synuclein aggregates. Fibril formation is tightly linked to the inclusion-forming process in cells. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:48976–48983. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M208192200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee H-J. Patel S. Lee S-J. Intravesicular localization and exocytosis of alpha-synuclein and its aggregates. J Neurosci. 2005;25:6016–6024. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0692-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee H-J. Shin SY. Choi C. Lee YH. Lee S-J. Formation and removal of alpha-synuclein aggregates in cells exposed to mitochondrial inhibitors. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:5411–5417. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M105326200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee H-J. Suk JE. Bae EJ. Lee JH. Paik SR. Lee S-J. Assembly-dependent endocytosis and clearance of extracellular alpha-synuclein. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2008;40:1835–1849. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2008.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lee HJ. Bae EJ. Jang A. Ho DH. Cho ED. Suk JE. Yun YM. Lee SJ. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays for alpha-synuclein with species and multimeric state specificities. J Neurosci Methods. 2011;199:249–257. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2011.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lee HJ. Baek SM. Ho DH. Suk JE. Cho ED. Lee SJ. Dopamine promotes formation and secretion of non-fibrillar alpha-synuclein oligomers. Exp Mol Med. 2011;43:216–222. doi: 10.3858/emm.2011.43.4.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lee HJ. Suk JE. Patrick C. Bae EJ. Cho JH. Rho S. Hwang D. Masliah E. Lee SJ. Direct transfer of alpha-synuclein from neuron to astroglia causes inflammatory responses in synucleinopathies. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:9262–9272. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.081125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lee J. Culyba EK. Powers ET. Kelly JW. Amyloid-beta forms fibrils by nucleated conformational conversion of oligomers. Nat Chem Biol. 2011;7:602–609. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lee SJ. Desplats P. Sigurdson C. Tsigelny I. Masliah E. Cell-to-cell transmission of non-prion protein aggregates. Nat Rev Neurol. 2010;6:702–706. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2010.145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lee SJ. Lim HS. Masliah E. Lee HJ. Protein aggregate spreading in neurodegenerative diseases: problems and perspectives. Neurosci Res. 2011;70:339–348. doi: 10.1016/j.neures.2011.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Li J. Zhu M. Rajamani S. Uversky VN. Fink AL. Rifampicin inhibits alpha-synuclein fibrillation and disaggregates fibrils. Chem Biol. 2004;11:1513–1521. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2004.08.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Li JY. Englund E. Holton JL. Soulet D. Hagell P. Lees AJ. Lashley T. Quinn NP. Rehncrona S. Bjorklund A. Widner H. Revesz T. Lindvall O. Brundin P. Lewy bodies in grafted neurons in subjects with Parkinson's disease suggest host-to-graft disease propagation. Nat Med. 2008;14:501–503. doi: 10.1038/nm1746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Luk KC. Song C. O'Brien P. Stieber A. Branch JR. Brunden KR. Trojanowski JQ. Lee VM. Exogenous {alpha}-synuclein fibrils seed the formation of Lewy body-like intracellular inclusions in cultured cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:20051–20056. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0908005106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Maries E. Dass B. Collier TJ. Kordower JH. Steece-Collier K. The role of alpha-synuclein in Parkinson's disease: insights from animal models. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2003;4:727–738. doi: 10.1038/nrn1199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nasstrom T. Fagerqvist T. Barbu M. Karlsson M. Nikolajeff F. Kasrayan A. Ekberg M. Lannfelt L. Ingelsson M. Bergstrom J. The lipid peroxidation products 4-oxo-2-nonenal and 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal promote the formation of alpha-synuclein oligomers with distinct biochemical, morphological, and functional properties. Free Radic Biol Med. 2011;50:428–437. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2010.11.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nuscher B. Kamp F. Mehnert T. Odoy S. Haass C. Kahle PJ. Beyer K. Alpha-synuclein has a high affinity for packing defects in a bilayer membrane: a thermodynamics study. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:21966–21975. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M401076200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Paleologou KE. Kragh CL. Mann DM. Salem SA. Al-Shami R. Allsop D. Hassan AH. Jensen PH. El-Agnaf OM. Detection of elevated levels of soluble alpha-synuclein oligomers in post-mortem brain extracts from patients with dementia with Lewy bodies. Brain. 2009;132:1093–1101. doi: 10.1093/brain/awn349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Perrin RJ. Woods WS. Clayton DF. George JM. Exposure to long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids triggers rapid multimerization of synucleins. J Biol Chem. 2001;11:11. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M105022200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Qin Z. Hu D. Han S. Reaney SH. Di Monte DA. Fink AL. Effect of 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal modification on alpha-synuclein aggregation. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:5862–5870. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M608126200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Satake W. Nakabayashi Y. Mizuta I. Hirota Y. Ito C. Kubo M. Kawaguchi T. Tsunoda T. Watanabe M. Takeda A. Tomiyama H. Nakashima K. Hasegawa K. Obata F. Yoshikawa T. Kawakami H. Sakoda S. Yamamoto M. Hattori N. Murata M. Nakamura Y. Toda T. Genome-wide association study identifies common variants at four loci as genetic risk factors for Parkinson's disease. Nat Genet. 2009;41:1303–1307. doi: 10.1038/ng.485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shibata N. Inose Y. Toi S. Hiroi A. Yamamoto T. Kobayashi M. Involvement of 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal accumulation in multiple system atrophy. Acta Histochem Cytochem. 2010;43:69–75. doi: 10.1267/ahc.10005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Simon-Sanchez J. Schulte C. Bras JM. Sharma M. Gibbs JR. Berg D. Paisan-Ruiz C. Lichtner P. Scholz SW. Hernandez DG. Kruger R. Federoff M. Klein C. Goate A. Perlmutter J. Bonin M. Nalls MA. Illig T. Gieger C. Houlden H. Steffens M. Okun MS. Racette BA. Cookson MR. Foote KD. Fernandez HH. Traynor BJ. Schreiber S. Arepalli S. Zonozi R. Gwinn K. van der Brug M. Lopez G. Chanock SJ. Schatzkin A. Park Y. Hollenbeck A. Gao J. Huang X. Wood NW. Lorenz D. Deuschl G. Chen H. Riess O. Hardy JA. Singleton AB. Gasser T. Genome-wide association study reveals genetic risk underlying Parkinson's disease. Nat Genet. 2009;41:1308–1312. doi: 10.1038/ng.487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Trostchansky A. Lind S. Hodara R. Oe T. Blair IA. Ischiropoulos H. Rubbo H. Souza JM. Interaction with phospholipids modulates alpha-synuclein nitration and lipid-protein adduct formation. Biochem J. 2006;393:343–349. doi: 10.1042/BJ20051277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Uchida K. 4-Hydroxy-2-nonenal: a product and mediator of oxidative stress. Prog Lipid Res. 2003;42:318–343. doi: 10.1016/s0163-7827(03)00014-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wang W. Perovic I. Chittuluru J. Kaganovich A. Nguyen LT. Liao J. Auclair JR. Johnson D. Landeru A. Simorellis AK. Ju S. Cookson MR. Asturias FJ. Agar JN. Webb BN. Kang C. Ringe D. Petsko GA. Pochapsky TC. Hoang QQ. A soluble alpha-synuclein construct forms a dynamic tetramer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:17797–17802. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1113260108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Waxman EA. Giasson BI. A novel, high-efficiency cellular model of fibrillar alpha-synuclein inclusions and the examination of mutations that inhibit amyloid formation. J Neurochem. 2010;113:374–388. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2010.06592.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yoritaka A. Hattori N. Uchida K. Tanaka M. Stadtman ER. Mizuno Y. Immunohistochemical detection of 4-hydroxynonenal protein adducts in Parkinson disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:2696–26701. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.7.2696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zhu M. Rajamani S. Kaylor J. Han S. Zhou F. Fink AL. The flavonoid baicalein inhibits fibrillation of alpha-synuclein and disaggregates existing fibrils. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:26846–26857. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M403129200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.