Abstract

Objective

Securing protected health information is a critical responsibility of every healthcare organization. We explore information security practices and identify practice patterns that are associated with improved regulatory compliance.

Design

We employed Ward's cluster analysis using minimum variance based on the adoption of security practices. Variance between organizations was measured using dichotomous data indicating the presence or absence of each security practice. Using t tests, we identified the relationships between the clusters of security practices and their regulatory compliance.

Measurement

We utilized the results from the Kroll/Healthcare Information and Management Systems Society telephone-based survey of 250 US healthcare organizations including adoption status of security practices, breach incidents, and perceived compliance levels on Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health, Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act, Red Flags rules, Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, and state laws governing patient information security.

Results

Our analysis identified three clusters (which we call leaders, followers, and laggers) based on the variance of security practice patterns. The clusters have significant differences among non-technical practices rather than technical practices, and the highest level of compliance was associated with hospitals that employed a balanced approach between technical and non-technical practices (or between one-off and cultural practices).

Conclusions

Hospitals in the highest level of compliance were significantly managing third parties’ breaches and training. Audit practices were important to those who scored in the middle of the pack on compliance. Our results provide security practice benchmarks for healthcare administrators and can help policy makers in developing strategic and practical guidelines for practice adoption.

Introduction

Growing concern over healthcare information security in the USA has led to increased regulation and changes in the required security practices needed to achieve compliance. However, some surveys by both industry groups and the US Department of Health and Human Services noted wide disparity both in security practices and in perceived compliance with federal (Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health (HITECH)/Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA)) and state regulations.1 2 It is not surprising that hospital practices vary, given the varying applications and interpretations of federal and state regulation. Low levels of perceived compliance thus indicate that managers are uncertain about their own practices and the required path to compliance.

Given the variety of technical and non-technical security practices that hospitals can implement, how do managers make strategic implementation choices? How are different sets of security practices associated with perceived regulatory compliance? Although recent research has paid attention to the organizational and sociotechnical aspects of security management,3 4 there is a dearth of empirical literature that considers the relationship between the configuration of security practices and compliance. This paper represents one effort at addressing this void in the informatics literature by providing a snapshot of security practices and perceived regulatory compliance.

We utilized data from the Kroll/Healthcare Information and Management Systems Society (HIMSS) telephone-based survey of 250 US healthcare organizations. (The Kroll/HIMSS survey was conducted in December 2009. Kroll is a corporate investigations and risk-consulting firm. HIMSS is the leading organization representing the health information management systems and services industry.) Security practice patterns were classified into groups using cluster analysis, and the relationships between the clusters and perceived regulatory compliance were analyzed using t tests. We found three clusters of security practices that are associated with different levels of perceived regulatory compliance. Although high practice adoption, across the board, was generally associated with high perceived compliance, our analysis revealed specific patterns of security practices and how the patterns are related to compliance. While audit practices were important to those who scored in the middle of the pack on compliance, hospitals in the highest level of compliance were significantly managing third parties’ breaches and training. As perceived regulatory compliance may not necessarily be correlated to actual security effectiveness, we also examined their relationship using the number of security breaches. Our results provide security practice benchmarks for healthcare administrators and can help policy makers in developing strategic and practical guidelines for practice adoption.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. The next section provides research background on security and compliance from previous literature. Then, we describe our data and the research methods followed by the results. The paper concludes with a discussion of our findings and their implications for practice and future research.

Background

Security practices include management processes for detecting and mitigating information risks as well as the implementation of technical safeguards.5 6 Unfortunately, many healthcare organizations follow a reactive path of implementing technical stopgaps because information security has been considered to be largely a technical issue—independent from the business of providing care.7 8 However, that view is beginning to shift towards a more holistic sociotechnical perspective on information security, emphasizing the importance of integrating technical solutions with organizational security culture, policies, and education.9–11 A sociotechnical perspective relies on many of the same underlying mechanisms as societal laws: providing knowledge (through education) of what constitutes acceptable and unacceptable conduct to increase the efficiency of an organization's security activities.12

Given the heterogeneity of security practices, researchers and practitioners have called for organizations to be more strategic in their approach to information security—yet it has not always been clear what such an approach looks like in practice.3 4 13 Organizations are faced with a dynamic information security environment characterized by constantly changing risks and legal compliance issues.4 14 Within this environment, healthcare organizations must develop a security strategy that ensures compliance as well as protecting patient information.15 Hospitals that achieve this objective will have a highly effective information security strategy. However, many have emphasized simple checklists of technical components rather than striving to deploy strategic solutions.10 Therefore, this study attempts to provide better strategic implementation choices for hospitals by identifying the relationship between security practices and regulatory compliance.

Research methodology

Data sources

We used data that were collected via a telephone survey conducted by Kroll/HIMSS. The purpose of the survey was to examine patient data security in US healthcare facilities. It was administered to 250 randomly selected US hospitals through interviews of managers who held privacy and security responsibilities. Only one respondent per organization was invited to participate in this survey. One hundred and thirteen respondents (45%) reported their title as a health information management manager, 43 (17%) as compliance officer, 20 (8%) as senior IT executive, 18 (7%) as privacy officer, and the remaining as other IT executive, including risk manager, chief executive officer, HIPAA director and quality manager.

The data covered hospitals’ security practices (1 if adopted, 0 otherwise) and perceived regulatory compliance for HITECH, Red Flag rules, HIPAA, state security laws, and Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) regulations (measured on a 7-point scale where 1 is ‘not at all compliant’ and 7 is ‘compliant with all applicable standards’). We say ‘perceived’ compliance because compliance in most cases is not a simple binary measure. For example, under HIPAA, covered entities have a fair amount of latitude in designing and implementing security systems. Moreover, there are no certifying bodies, so it is not possible to assess compliance externally. Hospital managers can obtain outside opinions and run internal assessments, but cannot obtain a certification. Therefore, perceived compliance is a manager's assessment of the organization's adherence to the regulation. Supplementary appendices A and B (available online only) present more information about the Kroll/HIMSS survey questionnaire and the regulations covered, respectively.

Our data also include hospital size and type: size is the number of licensed beds (measured on a 3-point scale where 1 is under 100 beds, 2 is 100–299 beds, and 3 is 300 beds or more) and critical access, general medical, and academic are all (exclusive) dummy variables that describe the hospital type. Table 1 provides descriptive statistics for the variables in our analysis: 125 hospitals (50%) had fewer than 100 beds; 92 (37%) had between 100 and 299 beds; and 32 (13%) hospitals had 300 or more beds. By hospital type, 140 (56%) were general medical/surgical; 10 (4%) were academic medical centers; and the remaining (40%) included critical access, pediatric, or other specialty hospitals.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics

| Variable name | Description (dichotomous indicators unless noted) | Mean | SD | Min | Max | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Safeguarding information | ||||||

| IT sec | Technical IT security measures (ie, firewalls, encrypted e-mails, network monitoring, intrusion detection, etc) | 0.98 | 0.14 | 0.00 | 1.00 | |

| Report breaches | Process in place for reporting breaches in patient information | 0.97 | 0.17 | 0.00 | 1.00 | |

| Data access | Data access minimization (ie, giving employees only the information they need) | 0.94 | 0.24 | 0.00 | 1.00 | |

| Who they say they are | Ensuring that patient is who they say they are | 0.91 | 0.28 | 0.00 | 1.00 | |

| Access and sharing policies | Specific policy in place to monitor electronic patient health information access and sharing | 0.87 | 0.33 | 0.00 | 1.00 | |

| Auditing | ||||||

| IT audit | IT applications have audit functions that monitor the access and use of patient information | 0.95 | 0.22 | 0.00 | 1.00 | |

| Audit systems | Regular audits are conducted of systems that generate/collect/transmit patient data | 0.87 | 0.33 | 0.00 | 1.00 | |

| Audit IT logs | IT audit logs are created and analyzed for inappropriate access to patient data | 0.83 | 0.37 | 0.00 | 1.00 | |

| Audit policies | Regular scheduled meetings are conducted to review status of data security policies | 0.77 | 0.42 | 0.00 | 1.00 | |

| Audit shared data | Regular audits are conducted for processes where patient information is shared with external organizations | 0.74 | 0.44 | 0.00 | 1.00 | |

| HR management | ||||||

| Hiring practices | Hiring practices (ie, background checks) | 0.97 | 0.17 | 0.00 | 1.00 | |

| HR monitor | HR monitors completion of courses on confidential patient data for hiring and continuing education tasks | 0.88 | 0.32 | 0.00 | 1.00 | |

| Education | Formal education courses | 0.86 | 0.35 | 0.00 | 1.00 | |

| Third-party security management | ||||||

| Third-party agreement | Business associate agreement signed by third party | 0.98 | 0.14 | 0.00 | 1.00 | |

| Report third-party breaches | Ensure that third party has plan for notifying covered entities of breach | 0.79 | 0.41 | 0.00 | 1.00 | |

| Detect third-party breaches | Ensure that third party has plan for identifying breaches | 0.76 | 0.43 | 0.00 | 1.00 | |

| Third-party training | Proof of employee training | 0.61 | 0.49 | 0.00 | 1.00 | |

| Compliance (1, not at all compliant; 7, ‘compliant with all applicable standards’) | ||||||

| Overall compliance | Overall compliance by factor analysis | 0.00 | 0.90 | −4.81 | 0.81 | |

| HITECH | HITECH | 5.75 | 1.39 | 1.00 | 7.00 | |

| Red | Red Flags rule | 6.14 | 1.21 | 1.00 | 7.00 | |

| HIPAA | HIPAA | 6.59 | 0.70 | 2.00 | 7.00 | |

| State | State security laws | 6.38 | 0.97 | 1.00 | 7.00 | |

| CMS | CMS regulations | 6.61 | 0.65 | 4.00 | 7.00 | |

| Organizational information | ||||||

| Size | Size (1–100, 2–100 to 299, 3–300 + beds) | 1.63 | 0.71 | 1.00 | 3.00 | |

| Critical access | Critical access | 0.35 | 0.48 | 0.00 | 1.00 | |

| General medical | General medical/surgical | 0.55 | 0.50 | 0.00 | 1.00 | |

| Academic | Academic | 0.04 | 0.19 | 0.00 | 1.00 | |

CMS, Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services; HIPAA, Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act; HITECH, Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health; HR, human resources.

Of the 250 observations, 46 were dropped because of missing data (eg, no answer or a ‘don't know’ option), and thus our final sample included 204 US hospitals. A statistical analysis of the 46 dropped surveys indicated no non-response bias (the 46 were not significantly different on any descriptive measure or on compliance with the five regulatory regimes).

Empirical analysis

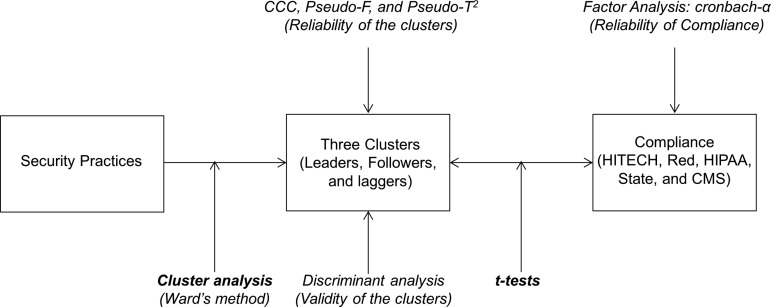

We examined patterns of security practices and the relationship between the patterns and regulatory compliance. After categorizing security practices into those that involve safeguarding information, auditing, human resources (HR) management, and third-party security management, we classified healthcare organizations based on their security practices using cluster analysis, and identified the features of practice patterns for each cluster. We further investigated the relationships between the clusters and their regulatory compliance using t tests. The reliabilities and validities of the compliance construct and clusters were examined using factor analysis, discriminant analysis, and three statistical criteria (CCC, Pseudo-F, and Pseudo-T2). Figure 1 provides an overview of our analysis.

Figure 1.

Multimethod research design. CMS, Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services; HIPAA, Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act; HITECH, Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health; Red, Red Flags rules.

First, security practices were divided into four types (ie, safeguarding, auditing, HR management, and third-party security management) to interpret our results better. We assessed the correlations between all security practices. Although a few practices were somewhat correlated within a type as shown in table 2 (cluster analysis makes no assumption about correlations), each practice provides its own unique protection features. We thus employed all security practices as one-item constructs to cluster healthcare organizations according to their adoption patterns.

Table 2.

Correlations among security practices and regulatory compliance

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | (9) | (10) | (11) | (12) | (13) | (14) | (15) | (16) | (17) | (18) | (19) | (20) | (21) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Safeguarding information | |||||||||||||||||||||

| (1) IT sec | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| (2) Report breaches | −0.02 | 1 | |||||||||||||||||||

| (3) Data access | 0.27 | −0.04 | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||

| (4) Who they say they are | 0.08 | 0.25 | 0.07 | 1 | |||||||||||||||||

| (5) Access and sharing policies | 0.05 | 0.11 | 0.15 | 0.14 | 1 | ||||||||||||||||

| Auditing | |||||||||||||||||||||

| (6) IT audit | 0.13 | −0.04 | 0.33 | 0.01 | 0.39 | 1 | |||||||||||||||

| (7) Audit systems | 0.05 | 0.28 | 0.22 | 0.24 | 0.34 | 0.19 | 1 | ||||||||||||||

| (8) Audit IT logs | 0.13 | 0.16 | 0.06 | 0.19 | 0.22 | 0.26 | 0.38 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| (9) Audit policies | 0.01 | 0.25 | 0.01 | 0.28 | 0.21 | −0.07 | 0.31 | 0.19 | 1 | ||||||||||||

| (10) Audit shared data | 0 | 0.29 | 0.09 | 0.21 | 0.17 | 0.12 | 0.47 | 0.36 | 0.31 | 1 | |||||||||||

| HR | |||||||||||||||||||||

| (11) Hiring practices | −0.02 | −0.03 | 0.08 | −0.05 | 0.02 | 0.09 | −0.07 | 0.08 | −0.03 | −0.04 | 1 | ||||||||||

| (12) HR monitor | −0.05 | 0.21 | −0.03 | 0.15 | 0.00 | −0.08 | 0.18 | 0.04 | 0.16 | 0.16 | 0.21 | 1 | |||||||||

| (13) Education | 0.04 | 0.1 | 0.14 | 0.17 | 0.01 | −0.03 | 0.22 | 0.19 | 0.21 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 1 | ||||||||

| Third party | |||||||||||||||||||||

| (14) Third-party agreement | −0.02 | −0.02 | −0.04 | −0.04 | −0.05 | −0.03 | −0.05 | −0.06 | 0.09 | 0.00 | −0.02 | −0.05 | 0.04 | 1 | |||||||

| (15) Report third-party breaches | 0.02 | 0.2 | 0.08 | 0.06 | 0.10 | 0.11 | 0.24 | 0.23 | 0.24 | 0.27 | −0.02 | 0.12 | 0.14 | 0.19 | 1 | ||||||

| (16) Detect third-party breaches | 0 | 0.17 | 0.15 | 0.03 | 0.13 | 0.14 | 0.16 | 0.18 | 0.26 | 0.29 | 0.04 | 0.12 | 0.07 | 0.17 | 0.74 | 1 | |||||

| (17) Third-party training | 0.03 | 0.16 | 0.14 | 0.17 | 0.08 | 0.14 | 0.17 | 0.26 | 0.11 | 0.25 | 0.04 | 0.08 | 0.19 | 0.18 | 0.39 | 0.39 | 1 | ||||

| Regulations | |||||||||||||||||||||

| (18) HITECH | 0.00 | 0.11 | 0.16 | 0.06 | 0.20 | 0.16 | 0.23 | 0.16 | 0.25 | 0.15 | 0.23 | 0.28 | −0.01 | −0.03 | 0.31 | 0.35 | 0.32 | 1 | |||

| (19) Red | −0.07 | 0.21 | 0.15 | 0.17 | 0.09 | 0.03 | 0.14 | 0.10 | 0.25 | 0.16 | 0.15 | 0.14 | 0.12 | 0.16 | 0.19 | 0.19 | 0.19 | 0.45 | 1 | ||

| (20) HIPAA | 0.02 | 0.15 | 0.09 | 0.01 | 0.09 | 0.16 | 0.20 | 0.15 | 0.22 | 0.18 | 0.16 | 0.07 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.27 | 0.23 | 0.26 | 0.44 | 0.29 | 1 | |

| (21) State | 0.06 | 0.16 | 0.16 | 0.12 | 0.14 | 0.16 | 0.20 | 0.22 | 0.26 | 0.16 | 0.26 | 0.08 | 0.01 | −0.02 | 0.24 | 0.26 | 0.33 | 0.39 | 0.34 | 0.57 | 1 |

| (22) CMS | 0.08 | 0.07 | 0.11 | 0.13 | 0.22 | 0.11 | 0.13 | 0.22 | 0.36 | 0.28 | 0.25 | 0.15 | −0.06 | 0.02 | 0.21 | 0.24 | 0.30 | 0.45 | 0.35 | 0.45 | 0.55 |

Note: Values in bold represent statistically significant p value at 0.05.

CMS, Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services; HIPAA, Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act; HITECH, Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health; HR, human resources; Red, Red Flags rules.

In various contexts, such as psychological testing and marketing, clustering has been found to be a useful means for exploring datasets and identifying underlying groups among individuals.16 17 In this study, we employed clustering to examine groups of association among security practices. To derive distinct and meaningful configurations from the adopted security practices, we carried out a hierarchical cluster analysis using Ward's minimum variance method, which calculates variance between hospitals using dichotomous data indicating the presence or absence of security practices. The details of Ward's clustering are provided in supplementary appendix C (available online only).

With the result from clustering, we then examined three statistical criteria in order to ensure the reliability of the appropriate number of clusters: cubic clustering criterion, pseudo-F, and pseudo-T2.18 Local peaks of the cubic clustering criterion and pseudo-F combined with a small value of the pseudo-T2 (11.6) led us to conclude that the most appropriate number of clusters was three. In addition, a large pseudo-T2 (189) of the next cluster solution at four suggests that a good solution occurred immediately at 3.19 Supplementary appendix D (available online only) provides more information and graphs about these criteria.

We further tested the validity of the clusters using discriminant analysis, which is often used to verify the results of cluster analysis. The analysis runs the data back through the minimum-variance method as a discriminant function to see how accurately hospitals are classified. The results from our analysis indicated high levels of classification accuracy (95.88%, 80.52%, and 93.33% for clusters 1, 2, and 3, respectively). Supplementary appendix E (available online only) provides details of this analysis.

Results

Clusters of security practices (Ward's clustering)

Through Ward's clustering, three statistical criteria and discriminant analysis, we found that the hospitals’ security practice adoption patterns could be classified into three clusters. As shown in table 3, cluster 1 (which we call the security leaders), have the highest levels of security-practice adoption: cluster 2 (close followers) have the second highest level, and cluster 3 (laggers) have the lowest level. The security leaders in cluster 1 and the close followers in cluster 2 consist primarily of general medical organizations, 60% and 57%, respectively, followed by critical access and academic institutes. On the other hand, the laggers in cluster 3 consist of critical access (63%) and general medical organizations (33%), with no academic institutes. In terms of size, the laggers (1.33) are significantly smaller than the security leaders (1.67) and followers (1.69). This may imply that the laggers’ low adoption is attributed to the limited budgets of relatively small hospitals.

Table 3.

Clustering security practices

| t Test | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cluster 1 (leaders) (n=97) | Cluster 2 (followers) (n=77) | Cluster 3 (laggers) (n=30) | Clusters 1 and 2 | Clusters 1 and 3 | Clusters 2 and 3 | ||||

| Security practices | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean differences and their significance | ||

| Safeguarding information | |||||||||

| IT sec | 0.99 | 0.10 | 0.99 | 0.11 | 0.93 | 0.25 | 0.00 | 0.06 | 0.06 |

| Report breaches | 1.00 | 0.00 | 0.99 | 0.11 | 0.83 | 0.38 | 0.01 | 0.17** | 0.16** |

| Data access | 1.00 | 0.00 | 0.91 | 0.29 | 0.83 | 0.38 | 0.09** | 0.17** | 0.08 |

| Who they say they are | 0.99 | 0.10 | 0.88 | 0.32 | 0.73 | 0.45 | 0.11** | 0.26*** | 0.15* |

| Access and sharing policies | 0.94 | 0.24 | 0.92 | 0.27 | 0.53 | 0.51 | 0.02 | 0.41*** | 0.39*** |

| Safeguarding mean | 0.98 | 0.09 | 0.94 | 0.22 | 0.77 | 0.39 | 0.05 | 0.21 | 0.17 |

| Auditing | |||||||||

| IT audit | 0.99 | 0.10 | 0.96 | 0.19 | 0.80 | 0.41 | 0.03 | 0.19** | 0.16** |

| Audit systems | 1.00 | 0.00 | 0.91 | 0.29 | 0.37 | 0.49 | 0.09** | 0.63*** | 0.54*** |

| Audit IT logs | 0.96 | 0.20 | 0.84 | 0.37 | 0.40 | 0.50 | 0.12** | 0.56*** | 0.44*** |

| Audit policies | 0.90 | 0.31 | 0.77 | 0.43 | 0.37 | 0.49 | 0.13** | 0.53*** | 0.4*** |

| Audit shared data | 0.90 | 0.31 | 0.77 | 0.43 | 0.13 | 0.35 | 0.13** | 0.77*** | 0.64*** |

| Auditing mean | 0.95 | 0.18 | 0.85 | 0.34 | 0.41 | 0.45 | 0.10 | 0.54 | 0.44 |

| HR management | |||||||||

| Hiring practices | 0.99 | 0.10 | 0.96 | 0.19 | 0.93 | 0.25 | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.03 |

| HR monitor | 0.96 | 0.20 | 0.84 | 0.37 | 0.73 | 0.45 | 0.12** | 0.23** | 0.11 |

| Education | 0.97 | 0.17 | 0.86 | 0.35 | 0.50 | 0.51 | 0.11** | 0.47*** | 0.36** |

| HR mean | 0.97 | 0.16 | 0.89 | 0.30 | 0.72 | 0.40 | 0.09 | 0.25 | 0.17 |

| Third-party security management | |||||||||

| Third-party agreement | 1.00 | 0.00 | 0.96 | 0.19 | 0.97 | 0.18 | 0.04 | 0.03 | −0.01 |

| Report third-party breaches | 1.00 | 0.00 | 0.69 | 0.47 | 0.40 | 0.50 | 0.31*** | 0.60*** | 0.29** |

| Detect third-party breaches | 0.99 | 0.10 | 0.61 | 0.49 | 0.40 | 0.50 | 0.38*** | 0.59*** | 0.21* |

| Third-party training | 0.96 | 0.20 | 0.32 | 0.47 | 0.20 | 0.41 | 0.64*** | 0.76*** | 0.12 |

| Third-party mean | 0.99 | 0.08 | 0.65 | 0.41 | 0.49 | 0.40 | 0.34 | 0.50 | 0.15 |

| Grand mean | 0.97 | 0.13 | 0.83 | 0.31 | 0.59 | 0.41 | 0.14 | 0.37 | 0.23 |

| Compliance | |||||||||

| Overall compliance (Cronbach's α:0.754) | 0.42 | 0.59 | −0.21 | 0.96 | −0.83 | 0.82 | 0.63*** | 1.25*** | 0.62 |

| HITECH | 6.35 | 1.07 | 5.38 | 1.31 | 4.73 | 1.60 | 0.97*** | 1.62*** | 0.65** |

| Red | 6.59 | 0.75 | 5.74 | 1.45 | 5.73 | 1.23 | 0.85*** | 0.86*** | 0.01 |

| HIPAA | 6.77 | 0.47 | 6.52 | 0.79 | 6.17 | 0.87 | 0.25** | 0.6*** | 0.35 |

| State | 6.71 | 0.59 | 6.25 | 1.00 | 5.67 | 1.37 | 0.46*** | 1.04*** | 0.58** |

| CMS | 6.85 | 0.39 | 6.53 | 0.66 | 6.03 | 0.89 | 0.32*** | 0.82*** | 0.5** |

| Compliance mean | 6.65 | 0.65 | 6.08 | 1.04 | 5.67 | 1.19 | 0.57 | 0.99 | 0.42 |

| Organizational information | |||||||||

| Size | 1.67 | 0.69 | 1.69 | 0.75 | 1.33 | 0.61 | −0.02 | 0.34** | 0.36** |

| Critical access | 0.29 | 0.46 | 0.32 | 0.47 | 0.63 | 0.49 | −0.03 | −0.34*** | −0.31** |

| General med | 0.60 | 0.49 | 0.57 | 0.50 | 0.33 | 0.48 | 0.03 | 0.27** | 0.24** |

| Academic | 0.04 | 0.20 | 0.05 | 0.22 | 0.00 | 0.00 | −0.01 | 0.04** | 0.05** |

p Values are represented by *significant at p<0.1, **significant at p<0.05, ***significant at p<0.01. Values in bold represent the average values of each type.

CMS, Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services; HIPAA, Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act; HITECH, Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health; HR, human resources; Red, Red Flags rules.

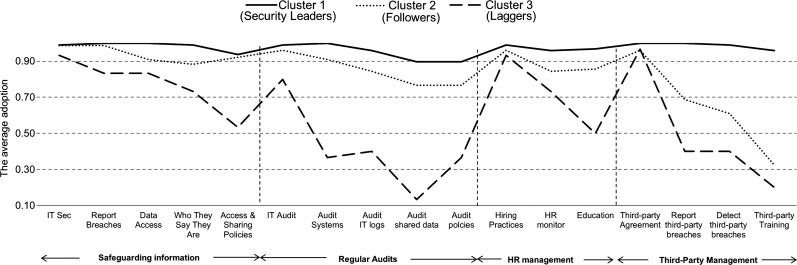

Figure 2 visually describes the clusters using the mean values of the security practices provided in table 3. It reveals interesting patterns of security practices. The security leaders in cluster 1 show high adoption across all practices while the others have big gaps. First, note that the adoption of technical solutions for safeguarding information is not significantly different (from 0.93 to 0.99) among three clusters. IT audit applications also have smaller differences (0.80 to 0.99), with the notable exception of non-technical audit practices (from 0.13 to 1.00). However, the figure shows that there was wide variation in the adoption of non-technical practices such as policies and procedures. For instance, the adoption of accessing and sharing policies ranges from 0.53 to 0.94, and the adoption of shared data audits ranges from 0.13 to 0.90.

Figure 2.

Security management clusters (average practice adoption for each cluster). HR, human resources,

Second, we can see that hospitals gave more weight to safeguarding information than to performing regular audits. All three clusters have higher mean values for safeguarding (0.98, 0.94, and 0.77 for the security leaders, followers and laggers, respectively) than auditing (0.95, 0.85, and 0.41). Furthermore, the SD for safeguarding information are smaller than for auditing (0.09, 0.22, and 0.39 vs 0.18, 0.34, and 0.45). This indicates that the adoption of safeguarding practices has fewer differences among hospitals than that of audit practices (for all clusters).

Third, in terms of HR management, most of the hospitals have adopted one-off practices such as background checking in hiring (0.99, 0.96, and 0.93). On the other hand, their adoption of cultural practices such as continuous monitoring (0.96, 0.84, and 0.74) and employee education (0.97, 0.86, and 0.50) varies.

Finally, healthcare organizations often share patient information with other external organizations, as patients move between local clinics, tertiary care centers, long-term rehabilitation centers, etc. Some non-compliance or data breaches result from loss or negligence by third parties. Therefore, we examine how a covered organization manages third-party security practices and which practices are related to its perceived compliance. From the results, we see big differences between the three clusters for third-party security management—the followers (cluster 2) and laggers (cluster 3) depended more on agreements signed by third parties than on persistently auditing breach management or training at third parties. While 97% of the laggers simply depend on third-party agreements, only 20% ensured third parties’ training programmes and 40% ensured their breach management. On the other hand, 96% of the security leaders (cluster 1) ensured training programmes at third parties and more than 99% ensured other third-party practices.

Security practices and regulatory compliance

Before examining the relationships between the clusters and regulatory compliance via t tests, we tested the reliability of regulatory compliance. In this study, we modeled regulatory compliance as an outcome variable. Compliance was self-reported by the respondents who were involved with the policies relating to the security of patient data in their organizations. In order to ensure the reliabilities of their evaluations, we conducted factor analysis to acquire ‘overall compliance’, a 5-item compliance measure from five regulations. The Cronbach's α of the 5-item compliance measure is 0.75, which is above the general threshold of 0.700 (see table 3).

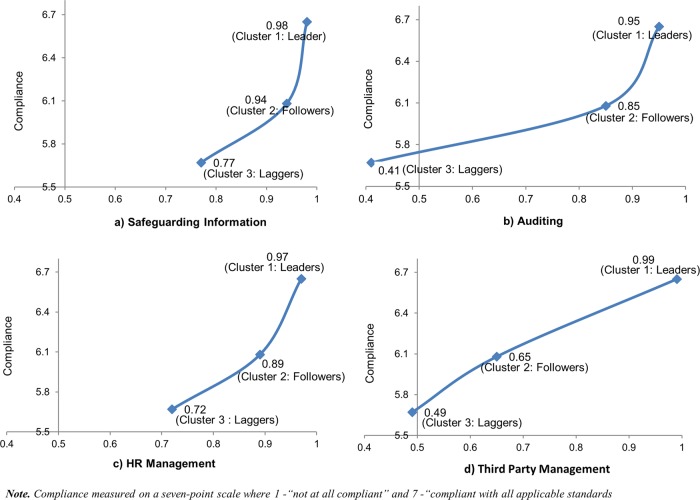

Next, we investigated (with t tests) the relationship between three clusters and regulatory compliance. The comparisons allowed us to test the association between security practices and perceived regulatory compliance. The results from overall compliance and individual regulations show very similar patterns (table 3). Figure 3 illustrates how the types of security practices vary with regulatory compliance. The graphs indicate that the effects of security practices are not uniform across the clusters as well as the four types of security practices.

Figure 3.

The relationships between security practices and regulatory compliance. HR, human resources. This figure is only reproduced in colour in the online version.

First, the adoption levels within safeguarding (0.77–0.98) and HR practices (0.72–0.97) are not significantly distinguished among the security leaders, followers and laggers (see table 3) for regulatory compliance. This indicates that the followers and laggers already reached solid adoption levels within safeguarding and HR practices.

On the other hand, the adoption levels within auditing (0.41–0.95) and third-party practices (0.49– 0.99) are widely dispersed across the three clusters. While the auditing distance between the security leaders in cluster 1 and the followers in cluster 2 is close, the laggers in cluster 3 significantly fell below the followers, as shown in table 3. In particular, regular audit policies and procedures have significantly larger differences than IT audit applications. That implies that the laggers should focus their efforts on developing auditing policies and procedures.

Finally, the followers were less likely to adopt third-party practices than the security leaders (although their adoption levels were a little higher than those of the laggers). Note that regulatory compliance (HITECH, HIPAA, and state) and third-party security management (breach practices and training) are significantly correlated (table 2), whereas third-party agreements show very low correlation. We can thus conclude that third parties’ breach management and training play a key role for covered entities’ perceived regulatory compliance (rather than third-party agreements), and furthermore those adoption levels differentiate the security leaders from the others.

Although perceived regulatory compliance is an important measure, compliance does not guarantee security performance. In fact, we found no correlation between compliance on individual measures (or our composite measure) and breach performance (see supplementary appendix F, available online only). Next, we tested the relationship between the clusters and security breaches that occurred in the past 12 months (focusing on leaders and followers because their sizes and types are similar while the lagger cluster only had 30 hospitals and their sizes and types are significantly different from the other two clusters—see table 3). t Tests between the leaders and followers showed that wider adoption of security practices is significantly associated with fewer security breaches (−0.58 at p<0.1). This implies that security performance such as preventing security breaches is not directly related to perceived regulatory compliance, but related to hospitals’ security practice patterns. Supplementary appendix F (available online only) shows security breach descriptive statistics, correlations, and the results from t tests.

Discussion

We draw several implications from the findings. First, our results imply that hospitals were trying to balance practice adoption within the four types of security practices (ie, safeguarding, auditing, HR management, and third-party security management). For example, the laggers in cluster 3 had widely adopted at least one security practice in each type (ie, third-party agreement (0.97), technical IT safeguarding measures (0.93), hiring practices (0.93), and IT audit applications (0.80)). These four representatives are ranked first to fourth within cluster 3, and the adoption levels of the first three are not significantly different from those of the security leaders in cluster 1. The followers in cluster 2 showed higher levels for practices that were very low for the laggers, while maintaining the laggers’ top four practices. Finally, the security leaders in cluster 1 had highly adopted all security practices in a balanced way. This seems to indicate that hospitals tried first to ensure coverage for major security type by adopting at least one practice, rather than comprehensively adopting practices within any single type. This may indicate that the current regulatory environment pushes hospitals towards a ‘cover the bases’ approach rather than deep adoption within any particular security type.

Second, hospitals probably put the highest priority on adopting technical safeguarding solutions (ie, firewalls, encrypted e-mails, network monitoring, intrusion detection, etc.) rather than security management processes. Similarly, in terms of auditing, they more frequently adopted IT applications to support audit functions than developing audit procedures. Despite the hospitals’ high adoption of technical solutions, their reported compliance levels varied. This compliance variation seems to be associated with the adoption levels of policies and procedures, suggesting that deploying non-technical solutions with technical solutions is important for improved regulatory compliance.

Third, hospitals with lower compliance preferred one-off practices sucha as hiring practices (eg, background checking) or third-party agreements to cultural practices such as education or developing security procedures. Improving cultural practices would be more difficult, because it requires all employees and organization partners to be involved in developing a mature security culture. As shown in table 2, the level of regulatory compliance is more closely associated with cultural practices than one-off third-party agreements.

Finally, security practices have different effects on compliance levels. Our results indicate that the laggers in cluster 3 should focus on auditing solutions to reach the middle of the pack on compliance, while ensuring third parties’ breach management and training are important to reach the highest level of compliance.

Regarding the levels of hospitals’ compliance and security practices adoption, policy makers should provide guidelines that balance adoption between technical and non-technical solutions and between one-off versus cultural tasks.

Limitations

Although this study sheds light on security practices and compliance, it is important to acknowledge the limitations. The survey data were self-reported by IT managers including IT executives, chief security officers, health information management directors, compliance officers and privacy officers in each participating organization. Therefore, our results are based on managerial perceptions of security practices and regulatory compliance. In addition, our data do not include information about hospitals’ location (to ensure anonymity). Therefore, our state compliance data are interpreted as the administrators’ evaluation with reference to their respective state security requirements.

Conclusions

We examined the adoption of security practices, with the goal of identifying dominant configurations, and their relationship to perceived regulatory compliance. Using survey data that provided the status of adopted security practices, we clustered 204 hospitals into three clusters. The clusters were based on practice similarities and associated compliance levels. While hospitals across all three clusters widely adopted technical practices, we found significant differences among non-technical practices. Furthermore, we demonstrated that audit practices play a critical role in the improved compliance we observed for the followers, while third parties’ breach management and training were important to reach the highest levels of compliance found among the leaders.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Kroll Fraud Solutions and the HIMSS Foundation for sharing survey data.

Footnotes

Contributors: MEJ: initiated the study, provided research direction, derived meaningful implications from the statistical outputs, and performed critical revision of the manuscript; JK: designed data analysis, developed statistical models, conducted analysis and interpretation of data, drafted and revised the paper.

Funding: This research was partly supported by the National Science Foundation, grant award number CNS-0910842, under the auspices of the Institute for Security, Technology, and Society (ISTS).

Competing interests: None.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.HHS (the US Department of Health and Human Services) The summary of nationwide health information network request for information responses USA: Department of Health and Human Services; 2005. http://archive.hhs.gov/news/press/2005pres/20050603.html (accessed August 2011). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pavolotsky J. Compliance best practices for information security: a perspective. corporate compliance insights 2011. http://www.corporatecomplianceinsights.com/compliance-best-practices-for-information-security-a-perspective/ (accessed January 2012).

- 3.Johnston AC, Warkentin M. Fear appeals and information security behaviors: an empirical study. MIS Quart 2010;34:549–66 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kayworth T, Whitten D. Effective information security requires a balance of social and technology factors. MIS Quart Exec 2010;9:163–75 [Google Scholar]

- 5.ITGI (IT Governance Institute) Board briefing on IT governance 2005(2) http://www.isaca.org/Knowledge-Center/Research/Documents/BoardBriefing/26904_Board_Briefing_final.pdf (accessed April 2011).

- 6.D'Arcy J, Hovav A, Galletta D. User awareness of security countermeasures and its impact on information systems misuse: a deterrence approach. Inform Syst Res 2009;20:79–98 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Urbaczewski A, Jessup LM. Does electronic monitoring of employee Internet usage work? Commun ACM 2002;45:80–3 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Murphy SN, Gainer V, Mendis M, et al. Strategies for maintaining patient privacy in i2b2. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2011;18:103–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Collmann J, Cooper T. Breaching the security of the Kaiser Permanente Internet patient portal: the organizational foundations of information security. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2007;14:239–43 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Puhakainen P, Siponen M. Improving employees’ compliance through information systems security training: an action research study. MIS Quart 2010;34:757–78 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Siponen M, Vance A. Neutralization: new insights into the problem of employee information systems security policy violations. MIS Quart 2010;34:487–502 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Herath T, Rao HR. Protection motivation and deterrence: a framework for security policy compliance in organisations. Eur J Inform Syst 2009;18:106–25 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Spears JL, Barki H. User participation in information systems security risk management. MIS Quart 2010;34:503–22 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Beard L, Schein R, Morra D, et al. The challenges in making electronic health records accessible to patients. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2010;19:116–20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McGraw G, Chess B, Migues S. Building security in maturity model: the BSIMM describes how mature software security initiatives evolve, change, and improve over time . September 2011 http://bsimm.com/download/ (accessed May 2012).

- 16.Ferratt TW, Agarwal R, Brown CV, et al. IT human resource management configurations and IT turnover: theoretical synthesis and empirical analysis. Inform Syst Res 2005;16:237–55 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ravichandran T, Rai A. Total quality management in information systems development: key constructs and relationships. J Manage Inform Syst 1999;16:119–55 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Milligan GW, Cooper MC. An examination of procedures for determining the number of clusters in a data set. Psychometrika 1985;50:159–79 [Google Scholar]

- 19.SAS Institute SAS/STAT 9.2 user's guide. 2010; 2 http://support.sas.com/documentation/cdl/en/statug/63033/PDF/default/statug.pdf (accessed April 2011).