Abstract

Background:

The psychological impacts of acne appearance and its-related negative emotional reactions have been proved; however, these reactions are varied in different populations.

Aim:

We investigated whether acne and its severity affected psychological functioning in those who suffered from this disorder among Iranians.

Materials and Methods:

One hundred and six patients with acne vulgaris who consecutively attended the dermatology outpatient clinics in Semnan city in 2008 were included. Among them, 103 patients met the study's inclusion criterion and agreed to participate. One hundred and six age and gender cross-matched healthy volunteers were included as controls that attended the clinic with their diseased relatives. All acne patients were evaluated using the Symptom Check List-90 (SCL-90).

Results:

According to the American Academy of Dermatology classification, 25.2% of the patients had mild acne, 50.5% moderate acne, and 24.3% severe acne. A higher percentage of participants than controls required further evaluation and psychological consultant when studying each psychological problem. The most common psychological symptoms requiring treatment due to disturbed daily activities in acne group were psychoticism (34.0%) and depression (31.1%), respectively. Significant positive correlations were observed between the duration of illness and SCL-90 total score. When evaluating the SCL-90 scores, patients with multiple sites of involvement were affected more severely than those with a single site of involvement.

Conclusion:

Acne vulgaris has significant effects on psychological status. Effective concomitant anti-acne therapy and psychological assessment make significant contributions for the mental health and should be strongly recommended.

Keywords: Acne, prevalence, psychodermatology

Introduction

What was known?

It has been recently substantiated the psychological impacts of acne appearance and proved its-related negative emotional reactions in the patients. The emotional impact of acne can be difficultly predictable because of the presence of many underlying factors is varied in different populations and thus identifying these determinants seems to be necessary.

Acne is a chronic inflammatory disorder of the skin that most commonly presents during adolescence, a period with psychological instability.[1] It has been known as a ubiquitous affliction with physical and emotional scars that persists throughout the life of the affected individuals. Besides experience of impaired functional status and decreased quality of life, it has been recently substantiated the psychological impacts of acne appearance and proved its-related negative emotional reactions in the patients. For instance, the occurrence of acne substantially augments the enormous stress that burdens most women, particularly the younger in today's demanding society.[2] Depression and anxiety have been suggested more prevalent among patients with acne than among control subjects.[3–6] The results of some studies indicated a higher level of emotional and social impairment, in terms of the feelings of physical discomfort, anger, and the intermingling impact of these, among these patients.[7]

Moreover, higher overall psychiatric morbidity in those with severe acne compared to normal population has been revealed.[8–10] However, the emotional impact of acne can be difficultly predictable because of the presence of many underlying factors such as patients’ age and gender, psychosocial developmental period, clinical severity of the disease, family and peer support systems, personality coping styles, and other underlying psychopathology. Thus, the impact of acne appearance on psychological status of individuals might be varied in different populations. The current study investigates whether acne and its severity affects psychological functioning in those who suffered from this disorder among Iranians.

Materials and Methods

One hundred and six patients with acne vulgaris who consecutively attended the dermatology outpatient clinics in Semnan city in 2008 were included. Among them, 103 patients met the study's inclusion criterion and agreed to participate. The study participants or their family members or relatives had no history of other skin disorders as well as no history of psychological problems. None of the patients had history of smoking and alcohol use. Also, all participants were in intermediate economic level [Table 1]. Moreover, none of them tended to special dietary patterns. The participants also had no history of anti-psychotic or anti-depressive drugs. Because of the potential effects of acne complications on late psychological events, the patients with these complications such as acne-related scars were not included into the study. One hundred and six age and gender cross-matched healthy volunteers were included as controls that attended the clinic with their diseased relatives. Examinations were performed by a single dermatologist. The institutional ethical committee approved the study design and informed consent was obtained from all patients and controls.

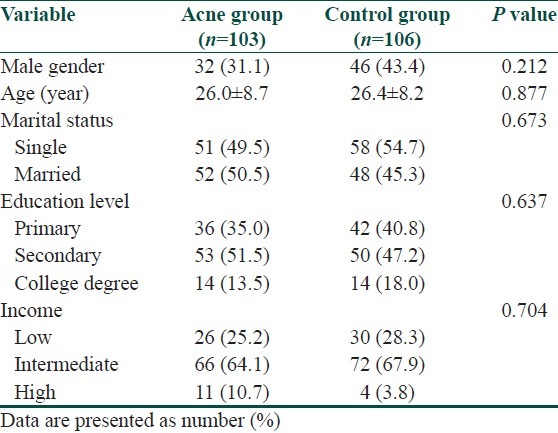

Table 1.

Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of the patients and the controls

The demographic and clinical questionnaires collected data on the demographic characteristics of the patients (age and gender), acne (localization, duration, and severity) and presence or absence of daily activity disturbance that considered as a criterion for need to treatment. Acne severity was classified as mild, moderate, or severe according to the classification of the American Academy of Dermatology[11] as: (1) Mild acne: Characterized by the presence of a few papules and pustules mixed with comedones, but no nodules; (2) Moderate acne: Characterized by the presence of many papules and pustules, together with a few nodules, and (3) severe acne: Characterized by the presence of numerous or extensive papules and pustules, as well as many nodules. Also, acne in participants was studied regarding its distribution and evaluated in 4 classes: Mostly the face and neck, mostly the body, mostly the limbs, and equally generally distributed.

All acne patients were evaluated using the Symptom Check List-90 (SCL-90) that was firstly developed by Derogatis et al.,[12] and was translated into Persian and its acceptable reliability and validity was proved among Iranian population. SCL-90 is a 90-item self-report symptom inventory. Each item of the “90” is rated on a five-point scale of distress (0-4), ranging from “not at all” to “extremely”. Psychological symptoms include somatization, obsessive–compulsive, interpersonal sensitivity, depression, anxiety, hostility, phobic anxiety, paranoid ideation, and psychoticism. Under usual circumstances, SCL-90 requires between 12 and 15 mins to be completed. We proposed that the cut-off point equaled the sum of one mean + standard deviation, which also equaled a T-score of 60 for each item. Patients with a score equal to or greater than the cut-off point are in need of detailed psychiatric assessment and consultant; as such scores indicate the presence of clinically significant symptoms.[13]

For statistically analysis, comparison of categorical variables between the independent groups was performed using Chi-square test and for determining the relationship between constant variables, Pearson's correlation coefficient was used. P values of 0.05 or less were considered statistically significant. All the statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 15.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

The patient group (103) consisted of 71 (68.9%) women and 32 (31.1%) men. Of the 106 controls, 60 (56.6%) were women and 46 (43.4%) were men. The mean ages of the patients and controls were 26.0 ± 8.7 and 26.4 ± 8.2 years, respectively. There was no significant difference between patients and controls with regard to age, gender, marital status, education level, as well as economic condition [Table 1].

According to the American Academy of Dermatology classification, 25.2% of the patients had mild acne, 50.5% moderate acne, and 24.3% severe acne. With regard to the duration of disease, 31.1% of patients had duration of less than 2 years, 33.0% had duration of 2 to 5 years and 35.9% had duration of 5 years or more.

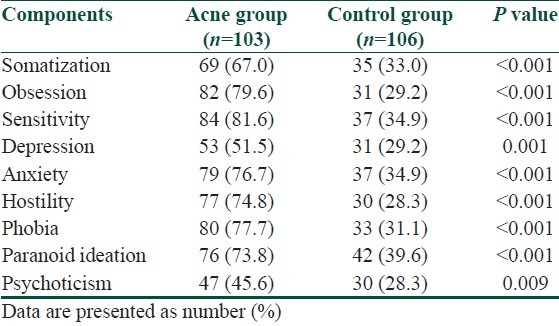

In almost 72.8% of the patients, acne localization was on the face and the neck, in 14.6% of them acne was mostly localized on the body, in 1.0% of the patients, acne was localized on the limbs and in others acne was generally distributed. As shown in Table 2, a higher percentage of participants than controls required further evaluation and psychological consultant when studying obsession (50.5, P < 0.001), sensitivity (46.7%, P < 0.001), phobia (46.6%, P < 0.001), hostility (46.5%, P < 0.001), anxiety (41.8%, P < 0.001), paranoid ideation (34.2%, P < 0.001), somatization (34.0%, P < 0.001), depression (22.3%, P = 0.001), and psychoticism (17.3%, P = 0.009) due to the appearance of primary psychological manifestations.

Table 2.

Relative frequency of patients and controls that require further evaluation and psychological consultant according to their symptom check list-90 scores

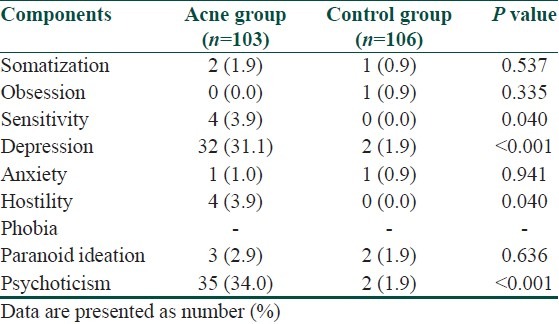

The most common psychological symptoms requiring treatment because of disturbed daily activities in acne group were psychoticism (34.0%) and depression (31.1%), respectively. Also, a higher percentage of participants than controls required beginning of the treatment when studying these two psychological symptoms as well as hostility and interpersonal sensitivity [Table 3].

Table 3.

Relative frequency of patients and controls that require psychological treatment according to their symptom check list-90 scores

Statistically significant positive correlations were observed between the duration of illness and SCL-90 total score (r = 0.456, P = 0.002). When evaluating the SCL-90 scores, patients with multiple sites of involvement were affected more severely than those with a single site of involvement (P = 0.026).

Discussion

The results of the current study revealed the negative influence of acne vulgaris on patients’ psychological status that all psychiatric symptoms such as somatization, obsession, sensitivity, depression, anxiety, hostility, phobia, paranoid ideation, and psychoticism were associated with this skin disorder. On the other hand, participants with acne had higher scores than controls in all SCL-90 items. Furthermore, the more severe acne and the longer its duration resulted in the worse psychological manifestations. Our findings could support those of many researches that have addressed the relationship between acne and psychological symptoms. In a study by Abdel-Hafez study, acne patients had significantly higher scores than controls in all items of the SCL-90.[13] In a qualitative study by Magin et al., psychological morbidity was considerable in acne patients and more prominent symptoms were embarrassment, impaired self-image, low self-esteem, self-consciousness, frustration, and anger.[14] Furthermore, in a similar study on Iranian patients, prevalence of anxiety and mean of anxiety scores were 68.3% and 9.17 ± 3.52, respectively, in patients group and 39.1% and 7.10 ± 3.07, respectively, in control group in which there was a significant difference.[15] It seems that high failure to seek appropriate medical treatments can results in disappointment of acne sufferers and therefore these patients might experience the initial symptoms of psychological problems. It was shown that out of approximately 2.7 to 3.5 million acne sufferers, only some 500,000 are presently undergoing medical treatment. Failure to seek medical treatment is closely associated with the fact that acne sufferers for the most part expect to be disappointed with the results.[16]

Our study also showed that although most of the study participants needed to psychological consultant because of their initial psychological symptoms, only overall incidence of depression and psychoticism were considerably high in the patients. We showed that the prevalence of these two problems was 31.1% and 34.0%, respectively, while the prevalence of other psychological aspects was lower than 4.0%. In some recent studies, 8% to 26% of patients with acne have been reported to suffer from at least mild depressive symptoms.[17–20] However, in some others, the rates of depressive symptoms in acne patients were considerably low that the acne did not seem to be related to depressive symptoms.[21,22] Based on our findings, the rates of depressive disorders and psychoticism can be high in acne patients in our population and therefore psychological consultations should be done in all acne patients, particularly in those with primary symptoms and primary diagnosis of these two problems.

Besides, effective treatment of acne can be accompanied by improvement in psychological impairment,[23–25] and therefore it seems that the patients with acne and concurrent appearance of the symptoms of psychological impairment require more appropriate acne therapy. In this regard, psychiatric consultation should be sought by dermatologists and patients should be followed with the cooperation of dermatologists and psychiatrists.[26] Totally, effective concomitant anti-acne therapy and psychological assessment make significant contributions for the mental health and should be strongly recommended.

What is new?

To confirm different aspects of psychological disorders in patient with acne, we evaluated these aspects and showed that effective concomitant anti-acne therapy and psychological assessment in these patients are necessary.

Acknowledgement

This study was supported by the Semnan University of Medical Sciences. We thank the University authorities who offered critical administrative support and managerial services in carrying out the study and also all researchers for their help and support.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: Nil.

References

- 1.Hahm BJ, Min SU, Yoon MY, Shin YW, Kim JS, Jung JY, et al. Changes of psychiatric parameters and their relationships by oral isotretinoin in acne patients. J Dermatol. 2009;36:255–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1346-8138.2009.00635.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fried RG, Wechsler A. Psychological problems in the acne patient. Dermatol Ther. 2006;19:237–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1529-8019.2006.00079.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yazici K, Baz K, Yazici AE, Köktürk A, Tot S, Demirseren D, et al. Disease-specific quality of life is associated with anxiety and depression in patients with acne. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2004;18:435–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2004.00946.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Polenghi MM, Zizak S, Molinari E. Emotions and acne. Dermatol Psychosomatics. 2002;3:20–5. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aktan S, Ozmen E, Sanli B. Anxiety, depression, and nature of acne vulgaris in adolescents. Int J Dermatol. 2000;39:354–7. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-4362.2000.00907.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grahame V, Dick DC, Morton CM. The psychological correlates of treatment efficacy in acne. Dermatol Psychosomat. 2002;3:119–25. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pruthi GK, Babu N. Physical and psychosocial impact of acne in adult females. Indian J Dermathol. 2012;57:26–9. doi: 10.4103/0019-5154.92672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mallon E, Newton JN, Klassen A, Stewart-Brown SL, Ryan TJ, Finlay AY. The quality of life in acne: A comparison with general medical conditions using generic questionnaires. Br J Dermatol. 1999;140:672–6. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.1999.02768.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mosam A, Vawda NB, Gordhan AH, Nkwanyana N, Aboobaker J. Quality of life issues for South Africans with acne vulgaris. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2005;30:6–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.2004.01678.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Magin PJ, Pond CD, Smith WT, Goode SM. Acne's relationship with psychiatric and psychological morbidity: Results of a school-based cohort study of adolescents. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2010;24:58–64. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2009.03354.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pochi PE, Shalita AR, Strauss JS, Webster SB, Cunliffe WJ, Katz HI, et al. Report of the consensus conference on acne classification. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1991;24:495–500. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(08)80076-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Derogatis LR, Lipman RS, Covi L. SCL-90, an outpatient psychiatric rating scale – preliminary report. Psychopharmacol Bull. 1973;9:13–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Abdel-Hafez K, Mahran AM, Hofny ER, Mohammed KA, Darweesh AM, Aal AA. The impact of acne vulgaris on the quality of life and psychologic status in patients from upper Egypt. Int J Dermatol. 2009;48:280–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2009.03838.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Magin P, Adams J, Heading G, Pond D, Smith W. Psychological sequelae of acne vulgaris: Results of a qualitative study. Can Fam Physician. 2006;52:978–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Golchai J, Khani SH, Heidarzadeh A, Eshkevari SS, Alizade N, Eftekhari H. Comparison of anxiety and depression in patients with acne vulgaris and healthy individuals. Indian J Dermatol. 2010;55:352–4. doi: 10.4103/0019-5154.74539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Korczak D. The psychological status of acne patients. Personality structure and physician-patient relations. Fortschr Med. 1989;107:309–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kellett SC, Gawkrodger DJ. The psychological and emotional impact of acne and the effect of treatment with isotretinoin. Br J Dermatol. 1999;140:273–82. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.1999.02662.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yazici K, Baz K, Yazici AE, Köktürk A, Tot S, Demirseren D, et al. Disease-specific quality of life is associated with anxiety and depression in patients with acne. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2004;18:435–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2004.00946.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ng CH, Tam MM, Celi E, Tate B, Schweitzer I. Prospective study of depressive symptoms and quality of life in acne vulgaris patients treated with isotretinoin compared to antibiotic and topical therapy. Australasian J Dermatol. 2002;43:262–70. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-0960.2002.00612.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kellett SC, Gawkroger DJ. A prospective study of the responsiveness of depression and suicidal ideation in acne patients to different phases of isotretinoin therapy. Eur J Dermatol. 2005;15:484–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Aktan S, Özmen E, Sanli B. Anxiety, depression, and nature of acne vulgaris in adolescents. Int J Dermatol. 2000;39:354–7. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-4362.2000.00907.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rehn LM, Meririnne E, Höök-Nikanne J, Isometsä E, Henriksson M. Depressive symptoms, suicidal ideation and acne: A study of male Finnish conscripts. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2008;22:561–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2007.02514.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Baldwin HE. The interaction between acne vulgaris and the psyche. Cuti. 2002;70:133–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tan JK. Psychosocial impact of acne vulgaris: Evaluating the evidence. Skin Therapy Lett. 2004;9:3–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Thomas DR. Psychosocial effects of acne. J Cutan Med Surg. 2004;8:3–5. doi: 10.1007/s10227-004-0752-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Seyhan M, Aki T, Karincaoglu Y, Ozcan H. Psychiatric morbidity in dermatology patients: Frequency and results of consultations. Indian J Dermathol. 2006;51:18–22. [Google Scholar]