Abstract

Newer management options are needed for leprosy control even at present, as it is predicted that new cases of leprosy will continue to appear for many more years in future. This article detail newer methods of clinical grading of peripheral nerve involvement (thickening, tenderness and nerve pain which are subjective in nature) and the advances made in the use of Ultrasonography and Colour Doppler as an objective imaging tool for nerves in leprosy. It also briefly discusses the newer drugs and alternative regimens as therapeutic management options which hold promise for leprosy in future.

Keywords: Clinical grading of nerve involvement, leprosy-new management options, newer drugs and regimens, ultrasonography and colour doppler imaging of nerves

Introduction

Leprosy is one of the oldest diseases known to the mankind and M. leprae was one of the first bacillus to be discovered and associated with a disease. However, advances in the management of this disease has been rather slow, compared to other bacillary diseases, due to the peculiarity of this bacillus (indolent nature, inability to grow in artificial media etc.) and the disease (long incubation period, disease spectrum dependent on host immunity etc.). Despite these short comings, great strides were made in the effective control and reaching the elimination target of leprosy in most countries of the world including India, chiefly due to the introduction of Multi Drug Therapy (MDT) in 1982 in its management.

While the numbers of leprosy patients decreased and elimination targets achieved worldwide, it should be noted that leprosy continues to occur in most parts of erstwhile endemic countries in good numbers. Unfortunately, the distinction between eradication and elimination is widely misunderstood[1] and largely as a consequence, research for newer options in leprosy has reduced considerably. There is a need to re-focus on improving the efforts for continuing education and training of existing personnel and in addition, strive to attract young minds and scientists to work for leprosy.

Newer options in leprosy

Search for improving existing management options is an ongoing process in any field and leprosy is no exception. Finding newer clinical and therapeutic options would be welcome as they benefit patients straight away while adding impetus to the leprosy programme, which seems to have reached a point of stagnation after elimination target was achieved by India in 2005 and vertical programme merged with general medical services.

Notwithstanding the slowing of research, significant advances were made in the last decade in understanding leprosy with unravelling of M. leprae genome in the year 2000 and advances made in the cellular and molecular basis for bacillary and host responses. We know now, based on its genomic configuration, the reason for the dormancy of M. leprae and it reluctance to initiate antigenic response in the host. The development of practical and quick DNA sequencing methods to detect drug resistance has helped greatly in establishing a sentinel surveillance network for drug resistance in leprosy.[2] DNA sequencing technology for M. leprae is in use for testing for drug resistance of common anti leprosy drugs such as dapsone, rifampicin and can also be applied to newer drugs such as ofloxacin as well. Compared to advances made in the cellular and molecular biology, conceiving applicable newer clinical management options seem to lag behind in the last decade.

We discuss below some of the recently introduced clinically applicable techniques and imaging options to define nerve involvement in leprosy, apart from newer drug regimens and alternatives to the existing MDT.

Advances in grading of nerve involvement in leprosy

But for nerve involvement, leprosy would have been a very simple disease as most complications and ill effects of leprosy are the direct results of nerve damage. In a study investigating the pathogenesis of neuropathy in North India, 94% of patients had nerve enlargement as the most common sign of leprosy.[3] In leprosy clinics, the nerve involvement in leprosy is assessed mostly by palpation of nerves although laboratory methods are also in use in few tertiary referral centres. Detailed below are clinical grading of peripheral nerve involvement and the use of ultrasonography as an imaging tool for nerves in leprosy.

Clinical grading of nerve thickness, tenderness and nerve pain

Palpation of peripheral nerves to assess their thickness and tenderness is an integral part of clinical examination in leprosy. Confirmation of nerve thickening by palpation is important as it is one of the clinical criteria for the diagnosis of leprosy in a patient. This is performed mainly at predetermined sites of the body along the course of the nerves commonly involved. Although terms such as mild, moderate and severe are used in rating these parameters for extent of involvement by various workers,[4] systematic method of grading of nerve thickening, tenderness and pain is not in practice.

Need for systematic grading of nerve thickening, tenderness and nerve pain

Nerve involvement in leprosy is a chronic event and once it occurs, persists for months to years. Hence, changes in their involvement during phases of leprosy reactions need to be followed up regularly and judiciously to prevent and limit the possible nerve damage and nerve function impairment (NFI). In this context, the grading of nerve thickening, tenderness and nerve pain are required for the systematic recording of these important clinical finding in the medical records at the initial and every follow-up visit for changes, to assess the effect of treatment instituted on them and the progress of the disease. Systematic grading of nerve involvement is also needed for communication of these observations between workers.

A standardized clinical grading of thickness, tenderness and nerve pain was not attempted till recently. One such grading of nerve thickness, tenderness and pain was detailed/proposed in a leprosy website in the year 2008.[5] Given below is the modified version of clinical grading of nerve thickening, nerve tenderness and nerve pain as practiced at Blue Peter Research Centre (BPRC), in Hyderabad.[6]

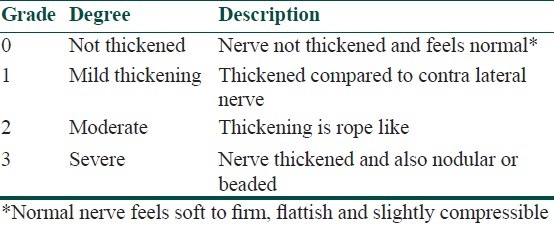

Grading of nerve thickening

A four-grade scale (0 to 3) is used to grade nerve thickening [Table 1]. The nerves are palpated at their most superficial locations and sites based on standard clinical methods. Each nerve should be palpated for at least 5 cm of its length wherever possible to detect beading or nodularity.

Table 1.

Clinical grading of nerve thickness

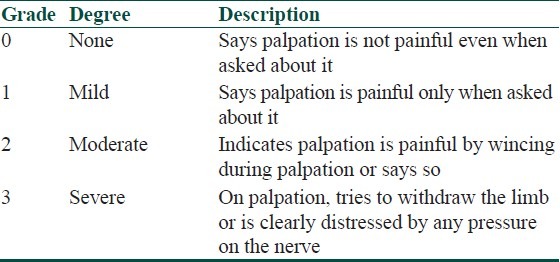

Grading of nerve tenderness

A four-grade scale (0 to 3) is used to grade tenderness [Table 2]. Nerve tenderness is elicited by applying mild to moderate pressure on the nerve during palpation. As this is a highly subjective assessment, while palpating the nerve, look for the patient's response (wincing, expression of distress on face or pulling away of limb) to evaluate the grade of tenderness. Repeated palpation of tender nerves should be avoided.

Table 2.

Clinical grading of nerve tenderness

Grading of neuropathic pain

Neuropathic pain also known as nerve pain (NP) is also defined as ‘pain initiated or caused by a primary lesion or dysfunction in the peripheral or central nervous system’.[7] According to the “Special Interest Group on Neuropathic Pain” (NeuPSIG), the definition of the Neuropathic pain is,[8] ‘pain arising as a direct consequence of a lesion or disease affecting the somatosensory system’.

Since leprosy is known to cause severe sensory loss leading to hypo/anesthesia, it is often wrongly assumed by some that NP is uncommon in leprosy. However, NP as a symptom can occur in leprosy before, during and after treatment. During active disease, patients who usually complain of NP are patients of pure neuritic leprosy and tuberculoid patients with type 1 reactions, although lepromatous patients with recurrent severe type 2 reactions can have bouts of intense nerve pain involving multiple nerve trunks. In patients ‘released from treatment’ NP occurs due to continued damage to the peripheral nerves, probably due to the persistent low grade inflammation and its sequelae. It could last for months to years.

The underlying pathological mechanisms put forward for NP include, excessive firing of pain mediating nerve cells that are insufficiently controlled by segmental and non-segmental inhibitory circuits and small fibre sensory neuropathy (SFSN) which predominantly affects small nerve fibres and its functions.[9] NP includes a wide spectrum of symptoms such as paraesthesia, dysaesthesia, hyperesthesia and allodynia along the nerve and in its area of distribution. The occurrence of paraesthesia could be in as high as in 24 % of the leprosy patients as observed in an Indian study.[3] Patient usually describes NP as ‘shooting’ ‘dragging’ ‘pulling’ or ‘electric shock like’, and also as ‘Jhum Jhum’ in nature,[10] which can force the patient to keep the limb in a position of rest. The most typical symptoms of chronic neuropathic pain in treated leprosy patients are continuous burning pain, dysesthesia, paresthesia, paroxysmal pain attacks.

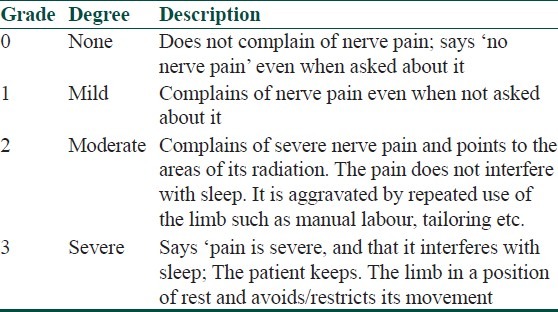

Please note that nerve tenderness is an elicitable sign, while nerve pain is a symptom complained by the patient. The grading of nerve pain is based on the severity as described by the patient, hence it does not need palpation of the nerve. Some workers have come out with a three page questionnaire for validation of neuropathic pain[11] that enquires and grades various symptoms of neuropathic pain which includes: Burning pain, squeezing pain, pressure like pain, electric shock like pain, stabbing pain, apart from dysathesia and paraesthesia. It scores each symptom separately and grades neuropathy based on the total score.

A much simpler four-grade scale (0 to 3) was proposed for grading of severity of nerve pain[6] based on the severity of the symptom/s (not on the type of symptom) which can be applied for each involved nerve in leprosy [Table 3]. Please note that ideally, nerve pain should be enquired and graded before the assessment of nerve thickening and tenderness in a leprosy patient, as palpation of nerve may modify/influence nerve pain severity grading if done later.

Table 3.

Grading of severity neuropathic pain based on symptoms

Relevance of clinical grading of nerve tenderness and NP to therapy: Grade of nerve thickening once recorded is usually not prone to changes over short intervals of days to weeks. However, grades of nerve tenderness and pain can show dramatic changes with or without treatment over short periods of time. When nerve tenderness and neuropathic pain is > grade 2; it usually requires immediate institution of corticosteroid therapy along with other measures to prevent further nerve function impairment (NFI).

How to record nerve thickness, tenderness and neuropathic pain: Nerve thickness, nerve tenderness and neuropathic pain can be designated as Th, T and NP respectively and the observations recorded in the case sheet. For example, for left ulnar nerve involvement of grade 2 thickening and tenderness and grade 1 nerve pain can be recorded as: Left Un: Th2, T2, NP1. Periodic changes can also be noted similarly in the follow-up sheets. Such detailed recordings in patients follow-up would especially be useful in clinical, drug and research studies.

Imaging of nerves in leprosy

The clinical method of assessing nerve damage is principally by palpation of nerve complemented by tools to test the integrity of nerve function by testing for motor, sensory and autonomic integrity by voluntary muscle testing (VMT), testing for sensation by graded Semmes Weinstein (SW) mono filaments and sweat test respectively. Other tests which could be performed are nerve conduction studies by ENMG and imaging of nerves by Ultrasonography (USG) and Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) which require specialized equipment and skilled technicians.

While clinical grading of nerves is subjective, recent advances in imaging of peripheral nerves have actually helped to observe structural changes in the nerves objectively. Imaging with the help of USG and MRI is being undertaken and performed worldwide for the identification of structural changes of peripheral nerve trunks over last two decades. Although MRI has shown to depict soft tissues with excellent resolution, it is expensive and time-consuming and may not always be as readily available compared with USG. Moreover, it is difficult to follow the peripheral nerves along its superficial course for identification of pathology with MRI as can be done easily with USG. The use of USG to reveal normal peripheral nerves and peripheral nerve tumors has been reported extensively in the radiology literature. Because of new technical developments, the resolution of USG has improved considerably and is sometimes even better than standard MRI.[12] Peripheral nerves have a typical USG pattern that correlates with histologic structure and USG with frequencies higher than 10 MHz are being used to support conventional USG in the depiction of superficial structures such as peripheral nerves and tendons.[13] Imaging of peripheral nerves can be done with reasonable precision with USG with broadband frequency of 10-14 MHz; CD frequency of 6-13 MHz and linear array transducer.

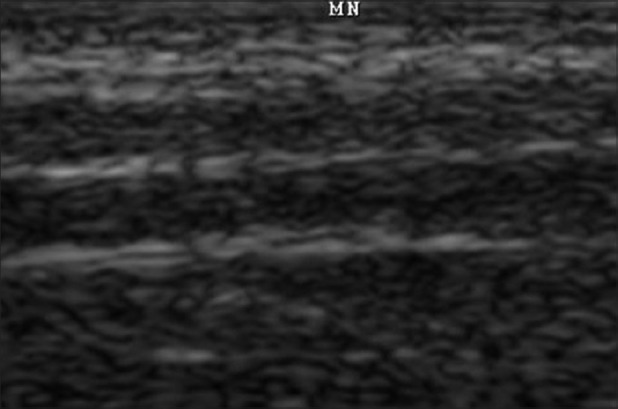

Normal peripheral nerves of extremities have been descried as markedly echogenic tubular structures with parallel linear internal echoes on longitudinal sonograms [Figure 1] with round to oval cross section on transverse scans with occasional internal punctuate echoes.[14,15] Sonographic imaging allows complete analysis of median, ulnar, posterior tibial nerve and studies have shown that the site of maximum involvement was limited to 6-10 cm above the flexor retinaculum for median nerves, 8-12 cm proximal to the cubital groove for ulnar nerves, and 4-10 cm proximal to the medial malleolus for posterior tibial nerve.[16]

Figure 1.

Ultrasonography image of the longitudinal scan of a healthy nerve

Not only can the above mentioned nerves, any peripheral nerve of reasonable thickness can be imaged by USG. Results of high resolution USG imaging on ulnar, radial, median, femoral, common peroneal, posterior tibial, sciatic nerves and on brachial plexus in healthy subjects and various disease states were already reported.[12,17] Healthy nerves show in transverse section a honeycomb like appearance made of hypo echoic fascicles surrounded by hyper echoic epineurium [Figure 2]. Nerve thickness may be quantified on longitudinal scan by measuring the antero-posterior diameter or on transverse scan by measuring the diameters in the scan or calculating the cross sectional area (CSA). The modern ultra sound machines are usually equipped with software to easily perform these measurements including CSA, accurate to the tenth of a millimetre. Studies have shown that USG was a very precise method to assess the dimensions of peripheral nerve trunks and ultrasound measurements were reliable. In addition, high resolution USG can support clinical and electro-physiologic testing for detection of a variety of nerve abnormalities, including entrapment neuropathies, trauma, infectious disorders and tumors.[18]

Figure 2.

Ultrasonography image of transverse scan of a healthy nerve showing honeycomb pattern

Most modern sonographic machines use pulsed colour doppler to assess whether structures, usually blood, are moving towards or away from the probe and its relative velocity. Color Doppler (CD) imaging of each nerve can be performed to look for absence or presence of blood flow signals in the perineural plexus and interfascicular vessels of nerve trunks. In health, neither the fascicles nor the epineurium show CD signals indicating normal (hypo) vascularity of nerve trunks. Based on identifying blood flow signals in these nerve trunks each nerve can be characterized as either normal or hypervascular. CD settings can be chosen to optimize identification of weak signals from vessels with slow velocity. To increase vascular depiction, the power mode for CD can also be used.

The increased blood flow signals seen in CD in thickened and tender peripheral nerves of leprosy supports the theory that they reflect the edematous and hyperemic changes secondary to the inflammation leading to alteration of an effective blood-nerve barrier during reversal reactions,[16] while being independent of the extent of destruction of nerve fascicles. Nerves of patients with leprosy reactions have shown increased blood flow signals in CD in the endo/perineurium, indicative of increased vascularity, giving a clue to the diagnosis of persistent reaction in them.[19] As neuritis in leprosy reactions varies in intensity, the detection of blood flow signals in those nerves with greater nerve cross sectional area and tenderness, points to its usefulness as a tool in assessing the severity of the neuritis.

Significant correlation was observed between clinical parameters of grade of thickening, sensory loss and muscle weakness and USG abnormalities of nerve echotexture, endoneural flow and CSA of nerves.[19] In leprosy, as important peripheral nerves are involved at selective sites of predilection at their most superficial locations along their course, routine USG scanning of these nerves in patients of leprosy provides an useful information on their state and extent of involvement. Follow-up USG imaging of nerves helps to know the changes in the CSA and structural integrity which could be correlated directly to treatment efficacy and clinical improvement. Moreover, such a non-invasive imaging provides documentable proof of nerve pathology which would be a welcome addition to the existing tests for detection and follow-up of nerve function impairment in these patients.

Advantages of imaging over clinical grading of nerves

The thickening of nerves appreciated on clinical examination is subjective and comparative in relation to the contralateral nerve. Moreover, confirming enlarged nerves can be often difficult in nerves such as median nerve because of their location, which can be overcome by USG imaging. USG is a very precise assessment method, while there is considerable inter-observer variability in assessing the presence of enlarged nerves by palpation.[20] In comparison, inter-observer agreement between sonographic measurements is excellent.[21] Besides enlargement, structural abnormalities such as integrity of fascicular structure, type of enlargement, edema and state of neural vascularity of nerves in leprosy patients can be studied by USG.

Newer drugs in leprosy therapy

The WHO recommended MDT regimens have been shown to be robust i.e. even if taken irregularly, they have benefited patients.[22] As a consequence, MDT for leprosy which was introduced in 1982 has changed little from its inception in its basic structure till date. The same three drugs (Dapsone, Clofazimine and Rifampicin) in the same dosages and schedules are still in use. Only significant change has been the reduction in the treatment duration of MB leprosy from 24 months to 12 months in 1998. No new drugs were introduced in to the programme, although ofloxacin and minocycline were introduced as a part of ROM (Rifampicin, Ofloxacin and Minocycline) therapy in 1998 for single lesions leprosy, only to be withdrawn quietly over next 5 years.[23]

Need for newer drugs and regimens in leprosy

Leprosy is a chronic infectious disease that has a limited number of drugs available for treatment; therefore, drug resistance is likely to pose a serious impediment to its control. The key decisive factor in determining the duration of chemotherapy is the sterilizing activity of treatment measured by the relapse rate after completion of treatment. The emergence of drug resistance is a cause for concern in this regard and is a threat to any control programme for infectious diseases. The lack of prioritization in research and also of resources, and the absence of information on the magnitude of drug resistance, cannot be considered as evidence that drug resistance does not exist in leprosy treatment.[24] It is generally believed that a combination of >2 drugs, with different mechanisms of action, taken regularly for a sufficient period, will prevent the emergence of drug resistance. The development of practical and quick DNA sequencing methods to detect drug resistance has helped greatly in establishing a sentinel surveillance network for drug resistance in leprosy. Sentinel surveillance to monitor the level of drug resistance in relapse cases has been setup by WHO in Brazil, China, Colombia, India, Myanmar, Philippines and Viet Nam.[2] At present, drug resistance to dapsone, rifampicin and the quinolones is being identified by looking at mutations in the binding sites of these drugs in large number of samples by molecular biological methods, not on the mouse footpad cultures anymore, which is a time-consuming and tedious method. Resistance to rifampicin and dapsone is reported. Clofazimine and minocycline resistance has not yet been reported.

Development of rifampicin resistance by M. leprae is considered a very serious threat to the efficacy of existing MDT programme. Patients suspected to be rifampicin resistant are also expected to be resistant dapsone. Hence, the proposed new MDT regimens could be of two types: One, to simplify treatment and facilitate supervision of multi drug administration for rifampicin-susceptible patients; and the other to treat patients with rifampicin-resistant leprosy or those who cannot tolerate rifampicin. In the year 1998 WHO technical advisory committee[25] recommended the following regimen for adults with suspected rifampicin resistance:

Daily administration of 50 mg of Clofazimine, together with 400 mg ofloxacin and 100 mg of minocycline for 6 months., followed by

Daily administration of 50 mg Clofazimine, together with 100 mg of minocycline or 400 mg of ofloxacin, for at least an additional 18 months.

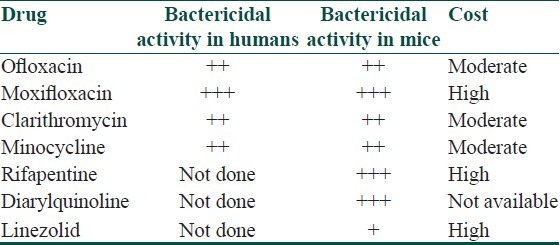

In the last two decades, new drugs with good efficacy against M. leprae have been identified which can be incorporated in multidrug regimens for leprosy [Table 4]. With the availability of these newer drugs, alternate regimens are being suggested for MB leprosy[25] which however, are still at a proposal stage. One of the very promising newer drugs[26] has been moxifloxacin, a broad-spectrum fluoroquinolone which was found to be the most active and more bactericidal than ofloxacin against M. leprae in mouse footpads. The bactericidal activity of moxifloxacin was identical to that of a single dose of rifampicin. Rifapentin, a rifamycin derivative, is another drug which has pharmacokinetic properties far more favorable than rifampicin, with significantly higher peak serum concentrations and a much longer serum half-life and was observed to be more effective than a single dose of rifampicin or the combinatinon of ROM in killing M. leprae in mouse footpad.[23]

Table 4.

Newer drug options in leprosy (modified from WHO Report of the global programme managers’ meeting on leprosy control strategy. New Delhi, India, 2009 SEA-GLP-2009.6)

Newer drug regimens suggested for leprosy in 2009 by the “WHO Report of the Global Programme Managers’ Meeting on Leprosy Control Strategy” is as follows:[27] For rifampicin susceptible MB patients a fully supervised monthly regimen could include: Rifapentin 900 mg (or rifampicin 600 mg), moxifloxacin 400 mg, and clarithromycin 1000 mg (or minocycline 200 mg) for 12 months. For rifampicin-resistant patients, the intensive phase could include moxifloxacin 400 mg, clofazimine 50 mg, clarithromycin 500 mg, and minocycline 100 mg daily supervised for six months. The continuation phase could comprise moxifloxacin 400 mg, clarithromycin 1000 mg, and minocycline 200 mg once monthly, supervised for an additional 18 months.

Conclusion

Are newer management options needed for leprosy control at present? The answer is emphatic yes, the reason being; despite the enormous reduction in the number of patients registered for treatment, it is predicted that new cases of leprosy will continue to appear for many more years. There is no evidence that the global initiative has led to the disappearance (“local eradication”) of infection or disease from any population, and leprosy continues to appear throughout Africa, Asia and Latin America.[1] Therefore, health services must sustain the provision of quality services at all levels in the foreseeable future. The ‘WHO Enhanced Global Strategy for years’ 2011-2015[28] has been formulated as a natural extension of its earlier strategies to help to sustain the gains made so far and further reduce the disease burden in all endemic countries. The strategy envisages reinforcing leprosy control agenda by investing in targeted research to find more powerful anti-leprosy drugs; to find new therapies for the prevention and management of neuritis and reactions and innovative interventions to prevent and limit disabilities due to leprosy. It is important that the current declining trend in the burden of leprosy be maintained in India and other countries where the disease is endemic. To maintain this momentum, new cases should be detected in a timely fashion, properly diagnosed and treated. Prevention and treatment of complications and nerve function impairment are to be sustained and improved by discovering newer management options for leprosy. Finally, community awareness of the disease needs to be increased so that people present for diagnosis at an early stage.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the help of Dr. TLN Praveen, Abhishek Institute of Imageology, Secunderabad, Andhra Pradesh, India for providing the USG images of peripheral nerves.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: Nil.

References

- 1.Fine PEM. Editorial. Bull World Health Organ. 2007;85:1–2. doi: 10.2471/BLT.06.039206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Drug resistance in leprosy: Reports from selected endemic countries. [cited in 2009];WHO weekly epidemiological record. 2009 84(26):261–8. Available from: http://www.who.int/wer . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.van Brakel WH, Nicholls PG, Das L, Barkataki P, Suneetha SK, Jadhav RS, et al. The INFIR Cohort Study: Investigating prediction, detection and pathogenesis of neuropathy and reactions in leprosy. Methods and baseline results of a cohort of multibacillary patients in North India. Lepr Rev. 2005;76:14–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jain S, Reddy RG, Osmani SN, Lockwood DN, Suneetha S. Childhood leprosy in an urban clinic, Hyderabad, India: Clinical presentation and the role of household contacts. Lepr Rev. 2002;73:248–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Srinivasan H. Nerve thickening standards. AIFO leprosy mailing list archives. [accessed on 2009 Feb 15]. Available from: http://www.aifo.it/english/resources/online/lml-archives/2008/210908-3.htm .

- 6.Rao PN, Suneetha S. Neuritis: Definition, clinical manifestations and proforma to record nerve impairment. In: Kar H, Kumar B, editors. IAL Text Book of Leprosy. 1st ed. New Delhi: Jaypee Brothers Medical Publishers (P) Ltd; 2010. pp. 253–9. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hietaharju A, Croft R, Alam R, Birch P, Mong A, Haanpää M. The existence of chronic neuropathic pain in treated leprosy. Lancet. 2000;356:1080–1. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02736-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Treede RD, Jensen TS, Campbell JN, Cruccu G, Dostrovsky JO, Griffin JW, et al. Redefinition of neuropathic pain and a grading system for clinical use: Consensus statement on clinical and research diagnostic criteria. Neurology. 2008;70:1630–5. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000282763.29778.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Haanpaa M, Lockwood DNJ, Hietaharju A. Neuropathic pain in leprosy. Lepr Rev. 2004;75:7–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lemaster JW, John O, Roche PW. Jhum-Jhum – a common paraesthesia in leprosy. Lepr Rev. 2001;72:100–1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bouhassira D, Attal N, Fermanian J, Alchaar H, Gautron M, Masquelier E, et al. Development and validation of the Neuropathic Pain Symptom Inventory. Pain. 2004;108:248–57. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2003.12.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Beekman R, Visser LH. High-resolution sonography of the peripheral nervous system: A review of the literature. Eur J Neurol. 2004;11:305–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2004.00773.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Silvestri E, Martinoli C, Derchi LE, Bertolotto M, Chiaramondia M, Rosenberg I. Echotexture of peripheral nerves: Correlation between USG and histologic findings and criteria to differentiate tendons. Radiology. 1995;197:291–6. doi: 10.1148/radiology.197.1.7568840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fornage BD. Peripheral nerves of the extremities: Imaging with USG. Radiology. 1988;167:179–82. doi: 10.1148/radiology.167.1.3279453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Graif M, Seton A, Nerubai J, Horoszowski H, Itzchak Y. Sciatic nerve: Sonographic evaluation and anatomic-Pathologic considerations. Radiology. 1991;181:405–8. doi: 10.1148/radiology.181.2.1924780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Martinoli C, Derchi LE, Bertolotto M, Gandolfo N, Bianchi S, Fiallo P, et al. USG and MR imaging of peripheral nerves in leprosy. Skeletol Radiol. 2000;29:142–50. doi: 10.1007/s002560050584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Visser LH. High resolution sonography of the common peroneal nerve: Detection of intraneural ganglia. Neurology. 2006;67:1473–5. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000240070.98910.bc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Martinoli C, Bianchi S, Cohen M, Graif M. Ultrasound of peripheral nerves. J Radiol. 2004;86:1869–78. doi: 10.1016/s0221-0363(05)81538-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jain S, Visser LH, Praveen TL, Rao PN, Surekha T, Ramesh E, et al. High-resolution sonography: A new technique to detect nerve damage in leprosy. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2009;3:e498. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen S, Wang Q, Chu T, Zheng M. Inter-observer reliability in assessment of sensation of skin lesion and enlargement of peripheral nerves in leprosy patients. Lepr Rev. 2006;77:371–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Beekman R, Schoemaker MC, van Der Plas JP, van den Berg LH, Franssen H, et al. Diagnostic value of high-resolution sonography in ulnar neuropathy at the elbow. Neurology. 2004;62:767–73. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000113733.62689.0d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.MDT: Managing irregular treatment FAQ. [accessed on 2010 Dec 10]. Available from: http://www.who.int/lep/mdt/irregular/en/index.html .

- 23.Rao PN. Recent advances in the control programs and therapy of leprosy. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2004;70:269–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.WHO Regional office of South-East Asia. New Delhi: 2009. Guidelines for Global Surveillance of Drug Resistance in Leprosy. SEA-GLP-2009.2. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Geneva: 1998. WHO expert committee on leprosy, WHO technical report series 874. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.WHO Report of the Global Programme Managers’ Meeting on Leprosy Control Strategy New Delhi. 2009 SEA-GLP-2009.6. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Grosset J. The new challenges for chemotherapy research: Work shop proceeding of leprosy research at new millennium. Lepr Rev. 2000;71:S100–4. doi: 10.5935/0305-7518.20000078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Enhanced Global Strategy for Further Reducing the Disease Burden due to Leprosy (Plan period: 2011-2015) New Delhi. World Health Organization. 2009 SEA-GLP-2009.3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]