Abstract

Background and purpose

Hip fractures are associated with high mortality, but the cause of this is still not entirely clear. We investigated the effect of surgical delay, weekends, holidays, and time of day admission on mortality in hip fracture patients.

Patients and methods

Using data from the Danish National Indicator Project, we identified 38,020 patients admitted from 2003 to 2010. Logistic regression analysis was used to study the association between sex, age, weekend or holiday admission, night-time admission, time to surgery, and ASA score on the one hand and mortality on the other.

Results

The risk of death in hospital increased with surgical delay (odds ratio (OR) = 1.3 per 24 h of delay), ASA score (OR (per point added) = 2.3), sex (OR for men 2.2), and age (OR (per 5 years) = 1.4). The mortality rate for patients admitted during weekends or public holidays, or at night, was similar to that found for those admitted during working days.

Interpretation

Minimizing surgical delay is the most important factor in reducing mortality in hip fracture patients.

Hip fractures are associated with a 30-day mortality rate of 7–10% (Davie et al. 1970, Parker et al. 1992, Moran et al. 2005, Rae et al. 2007). The effect of surgical delay on mortality has been studied over 2 decades. Shiga et al. (2008) concluded in a review that operative delay beyond 48 h after admission may increase the odds of 30-day all-cause mortality by 41% and of 1-year all-cause mortality by 32%. Another recent review by Leung et al. (2010) showed that there are a number of reports in the literature suggesting the beneficial effect of early surgery on improvement of short-term mortality, while other studies have not found any effect of early surgery, so no conclusion was drawn. Admission during night times, weekends, and public holidays when the number of clinical personnel is reduced has also been the subject of several studies (Bell and Redelmeier 2001, Crawford and Parker 2002, Foss and Kehlet 2006, Clarke et al. 2010, Schilling et al. 2010), but there are discrepancies among the study findings.

We investigated whether in-hospital mortality or 30-day mortality of patients 65 years of age or older admitted with acute hip fracture is exacerbated by (1) surgical delay, or (2) admission during the night, at weekends, or on public holidays rather than during normal weekdays.

Patients and methods

The study was based on data covering the entire Danish population. This was possible because all residents in Denmark are assigned a unique 10-digit personal identity number (CPR number) by the Danish Civil Registration System (CRS). The CRS has individual information on an individual’s name, sex, date of birth, place of birth, citizenship, and parents, and there is continuously updated information on vital status, place of residence, and spouse (Pedersen 2011). The CPR number is also used in all hospital records, enabling accurate linkage with the CRS.

To identify patients, we used the Danish National Indicator Project (DNIP), which is a nationwide initiative to monitor and improve the quality of care for 6 specific diseases, including acute hip fracture. Indicators, standards, and prognostic factors are implemented in all hospital units in Denmark (Mainz et al. 2004). The DNIP is characterized by a formal annual auditing process of the results, with the involvement of regional and hospital-based quality staff and all clinical units of relevance (Green 2011). Participation in the project is mandatory by law for all orthopedic departments in Denmark treating patients with acute hip fracture who are ≥ 65 years of age. According to the annual DNIP report from 2009, the coverage (i.e. the percentage of all hip fractures reported to the DNIP) ranged from 89% to 99% in the 5 regions of Denmark.

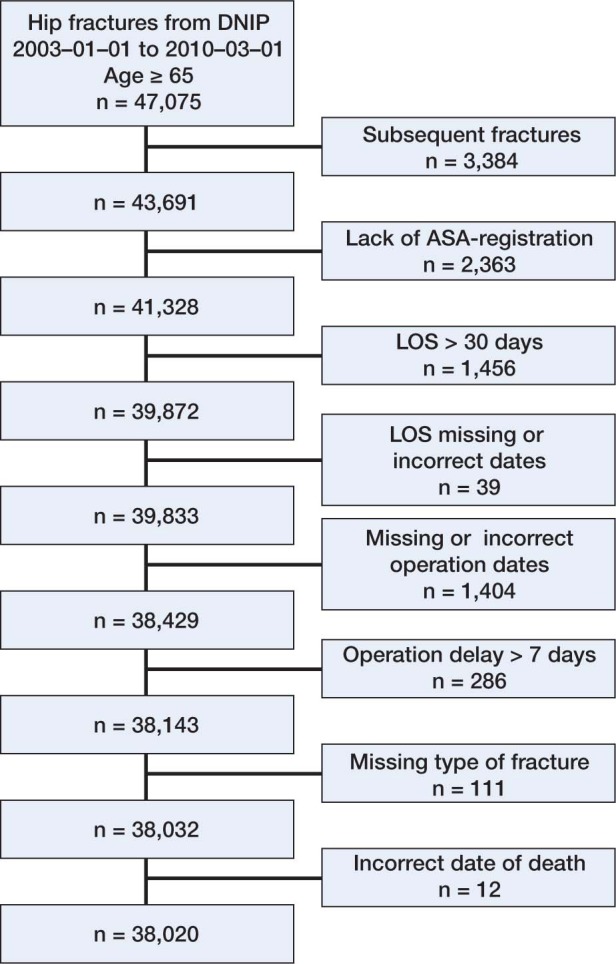

The DNIP provided us with information on 47,075 patients ≥ 65 years of age who were admitted with acute hip fracture from January 1, 2003 to March 1, 2010. We excluded 2,363 patients due to lack of ASA registration, 1,443 patients with missing or incorrect information on operation date, admission date, and/or discharge date, 111 patients with missing data on type of fracture, and 12 patients due to incorrect date of death. Furthermore, 1,456 patients with a length of stay (LOS) in hospital of longer than 30 days and 286 patients with an operation delay of more than 7 days were excluded to avoid the problem of a few patients with atypical medical problems affecting the statistics disproportionately. We restricted the study population to the first hip fracture registered in the study period, to get a statistically comparable group of patients, which excluded 3,384 subsequent fractures (Figure 1). The total number of patients included in the study was thus 38,020.

Figure 1.

The selection process.

Statistics

Normally distributed variables are shown as mean (SD) and differences between groups were analyzed using unpaired Student t-tests. Non-normally distributed variables are shown as medians with 5% and 95% percentiles, and Mann-Whitney U-tests were used to test for differences. Normality was evaluated using quantile/quantile plots. Categorical variables are shown as proportions and the differences were analyzed using chi-square tests. Odds ratios (ORs) were calculated for the predictors of in-hospital mortality and 30-day mortality using logistic regression analysis. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS statistical software. Any p-values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Demographics (Table 1)

Table 1.

Patient characteristics and mortality

| In-hospital mortality |

30-day mortality |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alive | Dead | p-value | Alive | Dead | p-value | |

| n | 36,326 | 1,694 | NA | 34,210 | 3,810 | NA |

| Women, n (%) | 26,959 (74.2) | 969 (57.2) | < 0.001 | 25,671 (75.0) | 2,257 (59.2) | < 0.001 |

| Age, years a | 82.5 (7.7) | 86.2 (7.2) | < 0.001 | 82.3 (7.6) | 86.1 (7.4) | < 0.001 |

| Length of stay (days) b | 9 (2–23) | 6 (2–20) | < 0.001 | 9 (2–23) | 5 (2–18) | < 0.001 |

| Time to operation, hours b | 22.1 (4.5–64.4) | 24.5 (4.6–74.8) | < 0.001 | 22.1 (4.5–64.4) | 23 (4.5–69.9) | 0.003 |

| ASA, n (%) | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | ||||

| ASA 1 | 3,591 (9.9) | 47 (2.8) | 3,529 (10.3) | 109 (2.9) | ||

| ASA 2 | 19,068 (52.5) | 514 (30.3) | 18,334 (53.6) | 1,248 (32.8) | ||

| ASA 3 | 12,054 (33.2) | 831 (49.1) | 11,025 (32.2) | 1,860 (48.8) | ||

| ASA 4 | 1,594 (4.4) | 290 (17.1) | 1,309 (3.8) | 575 (15.1) | ||

| ASA 5 | 19 (0.1) | 12 (0.7) | 13 (0.04) | 18 (0.5) | ||

| Type of fracture, n (%) | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | ||||

| Femoral neck fracture | 18,783 (51.7) | 766 (45.2) | 17,847 (52.2) | 1,702 (44.7) | ||

| Pertrochanteric fracture | 14,975 (41.2) | 781 (46.1) | 13,976 (40.9) | 1,780 (46.7) | ||

| Subtrochanteric fracture | 2,568 (7.1) | 147 (8.7) | 2,387 (7.0) | 328 (8.6) | ||

a Values are mean (SD).

b Values are median (range).

ASA score, 1–5: ASA 1, normal healthy patient; ASA 2, mild systemic disease; ASA 3, severe systemic disease; ASA 4, severe systemic disease that is a constant threat to life; ASA 5, a moribund patient who is not expected to survive more than 24 h with or without an operation.

NA: not applicable.

74% of the 38,020 patients admitted were women. Mean age for women was 83 (7.6) and that for men was 81 (7.7). There were 1,694 deaths in hospital (4.5%) and 3,810 deaths within 30 days (10%).

Effect of surgical delay, ASA score, age, sex, and type of fracture (Table 2)

Table 2.

Odds ratios for in-hospital mortality and 30-day mortality

| In-hospital mortality OR (95% CI) |

30-day mortality OR (95% CI) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Time to operation, per 24 h | 1.32 (1.25–1.39) | 1.24 (1.19–1.30) |

| Age, per 5 years | 1.43 (1.38–1.48) | 1.46 (1.49–1.42) |

| Sex, male vs.female | 2.23 (2.00–2.47) | 2.26 (2.09–2.43) |

| ASA, per score increment | 2.28 (2.13–2.45) | 2.32 (2.21–2.44) |

| Length of stay, per day | 0.91 (0.90–0.92) | 0.88 (0.87–0.89) |

| Type of fracture, per type increment | 1.25 (1.16–1.35) | 1.31 (1.24–1.39) |

Types of fracture: type 1, femoral neck fracture; type 2, pertrochanteric fracture; type 3, subtrochanteric fracture. We have included ASA score 1–5.

We defined “time to operation” as time from hospital admission to operation. After adjusting for ASA, age, sex, and type of fracture, the risk of death in hospital increased with surgical delay (OR = 1.3 per 24 h of delay). The risk of death within 30 days also increased with surgical delay (OR = 1.2 per 24 h of delay).

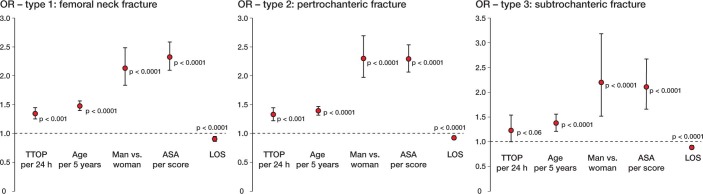

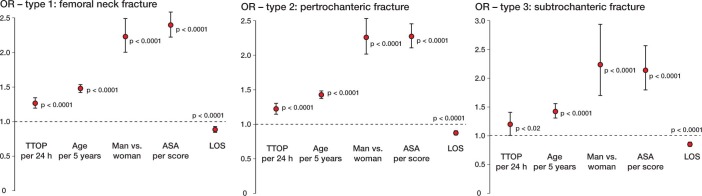

For in-hospital mortality, there was a significant change in mortality rate for ASA score (OR for every point added = 2.3), sex (OR for men = 2.2), and age (OR for every 5 years added = 1.4). We found similar results for 30-day mortality. The hip fractures were divided into the following types: type 1, femoral neck fracture; type 2, pertrochanteric; and type 3, subtrochanteric. The in-hospital mortality rate increased with type of fracture (OR per type increment = 1.3). The same was true for 30-day mortality rate (Table 2). We also calculated the odds ratio for in-hospital mortality and 30-day mortality for 5 different variables: time to operation (TTOP), age, sex, ASA score, and LOS, according to the 3 types of hip fractures (Figures 2 and 3).

Figure 2.

OR for in-hospital mortality related to five different variables for the 3 types of hip fractures. TTOP: time to operation; LOS: length of stay.

Figure 3.

OR for 30-day mortality related to five different variables for the 3 types of hip fractures. TTOP: time to operation; LOS: length of stay.

Effect of time of day, day of the week, month of admission, and holiday admission (Table 3)

Table 3.

In-hospital mortality and 30-day mortality according to month of admission, day of admission, and holiday admission

| In-hospital mortality (%) |

30-day mortality (%) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Month of admission | ||

| January | 4.8 | 10.8 |

| February | 4.8 | 10.6 |

| March | 4.6 | 9.9 |

| April | 5.0 | 10.4 |

| March | 3.9 | 9.2 |

| June | 4.1 | 9.5 |

| July | 3.9 | 9.2 |

| August | 4.1 | 9.6 |

| September | 4.6 | 10.4 |

| October | 4.5 | 10.1 |

| November | 4.4 | 9.6 |

| December | 4.7 | 10.6 |

| Day of admission | ||

| Monday | 4.2 | 10.0 |

| Tuesday | 4.6 | 9.6 |

| Wednesday | 4.6 | 9.9 |

| Thursday | 4.2 | 9.4 |

| Friday | 4.8 | 10.8 |

| Saturday | 4.5 | 10.4 |

| Sunday | 4.2 | 10.2 |

| Public holiday (PH) admission | ||

| Outside PH | 4.5 | 10.0 |

| During PH | 4.3 | 10.1 |

PH: public holiday.

The mortality rate for patients admitted during weekends was similar to the rate found for those admitted during working days. Similarly, neither month of admission nor admission during public holidays as opposed to working days had a significant effect on mortality rates. To determine whether mortality was affected by the time of admission during the day, we divided the day into 3 intervals: (1) 0800 h–1500 h, (2) 1500 h–2300 h, and (3) 2300 h–0800 h. The in-hospital mortality rate (%) for the time of admission was 4.7 for interval 1, 4.2 for interval 2, and 4.7 for interval 3 (p = 0.06). The 30-day mortality rate (%) for time of admission was 10.6 for interval 1, 9.2 for interval 2, and 10.9 for interval 3 (p < 0.001). However, the statistical significance of this effect disappeared in logistic regression analysis adjusted for time to surgery, age, sex, ASA, LOS, and type of fracture (p = 0.5). Similarly, no statistically significant effect of time of admission on in-hospital mortality was found in a logistic regression analysis adjusted for the same covariates (p = 0.2).

Longer LOS was associated with lower in-hospital mortality (OR per day = 0.91, 95% CI: 0.90–0.92) and 30-day mortality (OR per day = 0.88, 95% CI: 0.87–0.89).

Discussion

In this nationwide population-based study, we found that surgical delay after acute hip fracture is associated with a substantial increase in mortality rate: both in-hospital and at 30 days. As expected, the mortality rate was higher with increased age, higher ASA score, and male sex. More surprisingly, we found that patients who were admitted during public holidays, during weekends, and outside peak hours during the day did not have an increased mortality rate. The month of admission did not affect the mortality rate either.

The effect of surgical delay has been studied for 2 decades, with different findings. A review based on 52 studies involving 291,413 patients found that there were conflicting results regarding mortality, and the conclusion was that early surgery (within 48 h of admission) after hip fracture may reduce complications and mortality (Khan et al. 2009). Another review based on 42 studies did not find any solid evidence of the effect of early surgery on the mortality rate, but found that outcomes including morbidity and the length of hospital stay could be improved by shortening the waiting time to surgery (Leung et al. 2010). This lack of evidence may partly be explained by the fact that most studies had a low number of patients. In addition, “early surgery” was defined in different ways in different studies, which makes it difficult to compare the results.

Our study is strengthened by its population-based design, with 38,020 patients included and with detailed information on all individuals. We chose to divide the surgical delay into 24-h intervals instead of using an “early surgery” definition, and the results show that the difference between just 24 h and 48 h of surgical delay could be fatal for the patient. We therefore believe that it is of great importance to minimize the length of delay, and patients should be operated as soon as they are fit for surgery.

Not surprisingly, our analysis showed that increasing ASA score affected the mortality rate drastically, with an OR of 2.3 for every ASA point added. Also, male sex and age influenced the mortality rate. These crucial but non-modifiable factors have been the subject of interest in many previous studies, and a recent review and meta-analysis based on 75 studies involving 64,316 patients found similar results and identified these 3 factors to be strong preoperative predictors of mortality (Hu et al. 2011). Another non-modifiable factor is the type of fracture that the patient incurs. Femoral neck fractures had the lowest mortality rate, whereas subtrochanteric fractures had the highest.

The surprising result that length of stay was associated with both lower in-hospital mortality and 30-day mortality is most probably due to the fact that nursing home residents, who have the highest mortality rates (Pedersen et al. 2008), tend to be discharged early for subsequent rehabilitation at the nursing home.

The “weekend and holiday effect” on hip fracture is less studied and the results are conflicting. A study based on 3,789,917 admissions, 59,670 of which were acute hip fractures, found no significant difference in mortality between weekday and weekend admissions (Bell and Redelmeier 2001). The same was found in another study involving 4,183 patients (Clarke et al. 2010). Schilling et al. (2010) showed a higher mortality rate for weekend admissions in their study based on 166,920 patients, 8% of which were acute hip fractures, while Foss and Kehlet (2006) found an increased mortality rate for admissions during holidays but not for weekend admissions in their study involving 600 patients. We found no increase in mortality for patients admitted during weekends or holidays. Nor did time of admission or month of admission affect the mortality rate, despite the fact that it has been suggested in previous studies that reduction of staffing levels during weekends and holidays could be the cause of an increased mortality rate (Foss and Kehlet 2006, Schilling et al. 2010). Hip fracture is easy to diagnose, and a standardized treatment may compensate for the reduced staffing levels during weekends and holidays.

Conclusion

In summary, minimization of surgical delay is the most important factor in reducing the mortality rate for hip fracture. ASA score, sex, and age are also significant factors for the mortality rate. We found no increase in the mortality rate for admission during weekends or holidays.

Acknowledgments

Cecilie Laubjerg Daugaard: Study design, writing the paper, critical review of the paper. Henrik L Jørgensen: Study design, statistical calculations, critical review of the paper. Troels Riis: Study design, critical review of the paper. Jes B Lauritzen: Study design, critical review of the paper. Benn R Duus: Study design, critical review of the paper. Susanne van der Mark: Study design, critical review of the paper.

No competing interests declared.

References

- Bell CM, Redelmeier DA. Mortality among patients admitted to hospitals on weekends as compared with weekdays. N Engl J Med. 2001;345(9):663–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa003376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke MS, Wills RA, Bowman RV, Zimmerman PV, Fong KM, Coory MD, Yang IA. Exploratory study of the ‘weekend effect’ for acute medical admissions to public hospitals in Queensland. Australia. Intern Med J. 2010;40(11):777–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-5994.2009.02067.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crawford JR, Parker MJ. Seasonal variation of proximal femoral fractures in the United Kingdom. Injury. 2002;34(3):223–5. doi: 10.1016/s0020-1383(02)00211-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davie IT, MacRae WR, Malcolm-Smith NA. Anesthesia for the fractured hip. Anesth Analg. 1970;49:165–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foss NB, Kehlet H. Short-term mortality in hip fracture patients admitted during weekends and holidays. Br J Anaesth. 2006;96(4):450–4. doi: 10.1093/bja/ael012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green A. Danish clinical databases: an overview. Scand J Public Health. 2011;39:68–71. doi: 10.1177/1403494811402413. (7 Suppl) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu F, Jiang C, Shen J, Tang P, Wang Y. Preoperative predictors for mortality following hip fracture surgery: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Injury. 2012;43(6):676–85. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2011.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan SK, Kalra S, Khanna A, Thiruvengada MM, Parker MJ. Timing of surgery for hip fractures: a systematic review of 52 published studies involving 291,413 patients. Injury. 2009;40(7):692–7. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2009.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leung F, Lau TW, Kwan K, Chow SP, Kung AW. Does timing of surgery matter in fragility hip fractures? Osteoporos Int. 2010;21:529–34. doi: 10.1007/s00198-010-1391-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mainz J, Krog BR, Bjørnshave B, Bartels P. Nationwide continuous quality improvement using clinical indicators: the Danish National Indicator Project. Int J Qual Health Care (Suppl 1) 2004;16:i45–i50. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzh031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moran CG, Wenn RT, Sikand M, et al. Early mortality after hip fracture: Is delay before surgery important? J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 2005;87:483–9. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.D.01796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker MJ, Pryor GA. The timing of surgery for proximal femoral fractures. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 1992;74:203–5. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.74B2.1544952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen CB. The Danish Civil Registration System. Scand J Public Health. 2011;39(7):22–5. doi: 10.1177/1403494810387965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen SJ, Borgbjerg FM, Schousboe B, Pedersen BD, Jørgensen HL, Duus BR, Lauritzen JB. A comprehensive hip fracture program reduces complication rates and mortality. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56(10):1831–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.01945.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rae HC, Harris IA, McEvoy L, et al. Delay to surgery and mortality after hip fracture. Aust N Z J Surg. 2007;77:889–91. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-2197.2007.04267.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schilling PL, Campbell D A, Jr, Englesbe MJ, Davis MM. A comparison of in-hospital mortality risk conferred by high hospital occupancy, differences in nurse staffing levels, weekend admission, and seasonal influenza. Med Care. 2010;48(3):224–32. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181c162c0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiga T, Wajima Z, Ohe Y. Is operative delay associated with increased mortality of hip fracture patients? Systematic review, meta-analysis, and meta-regression. Can J Anaesth. 2008;55(3):146–54. doi: 10.1007/BF03016088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]