Abstract

Background and purpose

There has recently been interest in the advantages of minimally invasive surgery (MIS) over conventional surgery, and on local infiltration analgesia (LIA) during knee arthroplasty. In this randomized controlled trial, we investigated whether MIS would result in earlier home-readiness and reduced postoperative pain compared to conventional unicompartmental knee arthroplasty (UKA) where both groups received LIA.

Patients and methods

40 patients scheduled for UKA were randomized to a MIS group or a conventional surgery (CON) group. Both groups received LIA with a mixture of ropivacaine, ketorolac, and epinephrine given intra- and postoperatively. The primary endpoint was home-readiness (time to fulfillment of discharge criteria). The patients were followed for 6 months.

Results

We found no statistically significant difference in home-readiness between the MIS group (median (range) 24 (21–71) hours) and the CON group (24 (21–46) hours). No statistically significant differences between the groups were found in the secondary endpoints pain intensity, morphine consumption, knee function, hospital stay, patient satisfaction, Oxford knee score, and EQ-5D. The side effects were also similar in the two groups, except for a higher incidence of nausea on the second postoperative day in the MIS group.

Interpretation

Minimally invasive surgery did not improve outcome after unicompartmental knee arthroplasty compared to conventional surgery, when both groups received local infiltration analgesia. The surgical approach (MIS or conventional surgery) should be selected according to the surgeon’s preferences and local hospital policies.

ClinicalTrials.gov. (Identifier NCT00991445).

Knee arthroplasty is associated with moderate to severe pain, which may delay mobilization and home discharge. Several studies published over the last 2 decades have focused on improving postoperative pain management and mobilization after knee arthroplasty (Price et al. 2001, Reilly et al. 2005, Carlsson et al. 2006, Berend and Lombardi 2007). Minimally invasive surgery (MIS) and local infiltration analgesia (LIA) have contributed to improved patient outcome.

MIS, which was first introduced for unicompartmental knee arthroplasty (UKA), leaves the quadriceps muscle intact, in contrast to the conventional technique where the quadriceps tendon is split and the patella is dislocated and everted (Repicci and Eberle 1999). The fact that MIS causes less trauma to the soft tissues around the knee is believed to reduce postoperative pain and mobilization time (Price et al. 2001, Reilly et al. 2005, Carlsson et al. 2006, Berend and Lombardi 2007).

LIA involves local periarticular injection of a large volume of analgesic agents (local anesthetics combined with ketorolac and epinephrine) during the operation and 1 or more intraarticular bolus injections postoperatively (Kerr and Kohan 2008). Local anesthetic infiltration has often been part of the MIS concept and have developed together aimed to improve patient outcome (Repicci and Eberle 1999).

The use of MIS in total knee replacements has been debated (Khanna et al. 2009) and it is not universally accepted. MIS for UKA has been shown to be beneficial in a few studies (Price et al. 2001, Reilly et al. 2005, Carlsson et al. 2006, Berend and Lombardi 2007). In one of them, a randomized controlled study comparing MIS to conventional surgery in UKA (Carlsson et al. 2006), the authors found shorter hospital stay in the MIS group but no difference in postoperative pain or in range of knee motion. Furthermore, in an editorial, Röstlund and Kehlet (2007) called for studies investigating the importance of MIS together with LIA.

The main aim of this randomized controlled trial was to determine whether MIS for UKA would result in earlier home-readiness than conventional surgery when both groups received LIA. Secondary endpoints included length of hospital stay, pain intensity, morphine consumption, knee function, patient satisfaction, and quality of health. All patients were followed up for a period of 6 months.

Patients and methods

This randomized controlled trial was approved by the regional ethics committee in Uppsala, Sweden (February 2009; entry no. 2009/056). The study conformed to the Declaration of Helsinki and was registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (identifier NCT00991445).

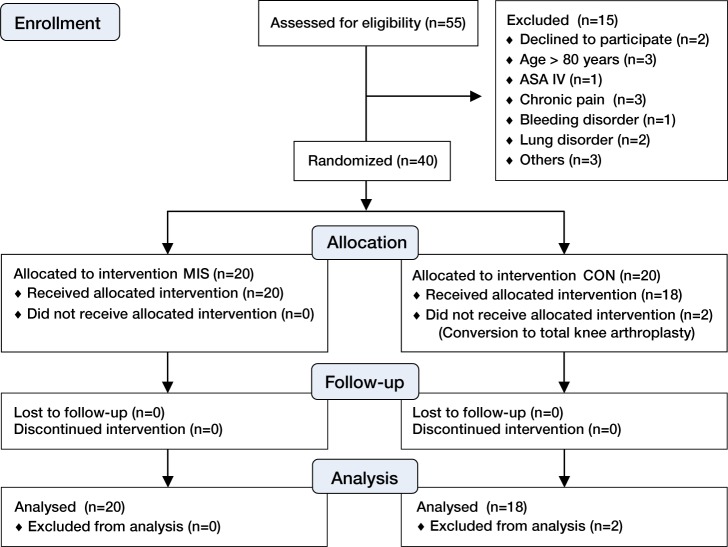

We screened 55 consecutive patients who were scheduled to undergo unilateral medial UKA for eligibility to participate in the study (Figure 1). The indications for surgery included persistent knee pain, medial radiographic changes (Ahlbäck grades I–III), correctable or almost correctable varus deformity, extension deficit of < 10º and flexion of > 100º. Patellofemoral changes were not considered to be a contraindication for surgery. Inclusion criteria were 20–80 years of age with ASA physical status I–III. Exclusion criteria were allergy or intolerance to any of the study drugs; severe liver, heart, or renal disease; chronic pain requiring opioid medication; or a bleeding disorder. 42 patients fulfilled the eligibility criteria.

Figure 1.

Study flowchart. The MIS group underwent minimally invasive surgery and the CON group underwent onventional surgery.

Written informed consent was obtained from 40 patients who agreed to participate (2 others declined). The operations were performed at the Department of Orthopedic Surgery, Örebro University Hospital, Sweden between May 2009 and March 2011. All procedures were performed by 1 of 2 senior orthopedic surgeons with long experience of both conventional and minimally invasive surgery in UKA. The main author (PE) was present at all surgeries and performed all LIA infusions.

Patients were randomized with a computer-generated sequence and each patient was assigned to either the MIS group or the CON group by opening a sealed envelope on the morning of surgery.

All patients were operated under general anesthesia, with a tourniquet applied before skin incision and removed after the compression bandage had been applied. All patients received a Link Endo-Model Sled Prosthesis (Link Sweden AB, Akersberga, Sweden). Preoperatively, the patients were given 2 g cloxacillin intravenously, and this was repeated at 8-hour intervals for the first 24 h. Dalteparin (5,000 IU) was given subcutaneously in the evening before surgery and every evening for the following 9 days.

Surgical procedure

The MIS group: The knee was exposed using a minimally invasive technique as follows. An 8- to 10-cm-long medial parapatellar skin incision was made from the upper medial pole of the patella and carried distally to the medial side of the tibial tuberosity. A medial parapatellar arthrotomy was performed from the base of the patella, leaving the muscle fibers of the vastus medialis untouched, continuing distally to the medial side of the tibial tuberosity, i.e. 2–3 cm below the joint line. The knee was brought to the figure-of-four position, and a retractor was placed behind the patellar tendon to allow visualization of the lateral compartment.

The CON group: The knee was exposed using a conventional technique in the following way. A 15- to 20-cm midline skin incision was made. A medial parapatellar arthrotomy was performed from the base of the patella and continued distally to the medial side of the tibial tuberosity. The arthrotomy was extended proximally 5–10 cm into the rectus tendon of the quadriceps muscle, to allow evertion and dislocation of the patella. The anterior cruciate ligament and the lateral compartment were inspected and evaluated.

In both groups, if the anterior cruciate ligament was found to be insufficient and/or the cartilage of the lateral compartment was damaged, the procedure was converted to a total knee arthroplasty and the patient was excluded from the study (2 patients in the CON group). The medial collateral ligament was not released.

Local infiltration analgesia technique

All patients in both groups received 400 mg ropivacaine, 30 mg ketorolac, and 0.5 mg epinephrine, diluted with normal saline to a total volume of either 116 mL in the MIS group or 156 mL in the CON group, since a larger area had to be infiltrated in the latter group.

Thus, in the MIS group, 300 mg ropivacaine (50 mL of 2 mg/mL + 20 mL of 10 mg/mL) + 30 mg ketotolac (1 mL of 30 mg/mL) + 0.5 mg epinephrine (5 mL of 0.1 mg/mL) was infiltrated into the joint capsule and ligaments, and an additional 100 mg of ropivacaine (10 mL of 10 mg/mL + 30 mL of saline) was infiltrated into the subcutaneous tissue. In the CON group, 300 mg ropivacaine (100 mL of 2 mg/mL + 10 mL of 10 mg/mL) + 30 mg ketotolac (1 mL of 30 mg/mL) + 0.5 mg epinephrine (5 mL of 0.1 mg/mL) was infiltrated into the joint capsule and ligaments and an additional 100 mg ropivacaine (10 mL of 10 mg/mL + 30 mL of saline) was infiltrated into the subcutaneous tissue.

In all patients, the surgeon placed a tunneled intraarticular multihole 20-G catheter before closing the wound in order to allow a bolus injection of the same drugs as above—through a bacterial filter—the following morning. No drains were left in the knee. A compression bandage was applied for 21 h. Ice packs were used for the first 6 h after the surgery.

21 hours postoperatively, all patients received a bolus injection (200 mg ropivacaine, 30 mg ketorolac, and 0.1 mg epinephrine; total volume 22 mL) via the intraarticular catheter. The catheter was then removed and the tip was sent for bacterial culture.

All patients received 1 g paracetamol orally 4 times daily. In the recovery room, a patient-controlled intravenous analgesia (PCA) pump with morphine (1-mg bolus and 6-min lockout time) was connected to all patients. 24 h postoperatively, the PCA pump was discontinued if VAS pain scores at rest were < 40 over a 2-h period (VAS scores range from 0–100 mm, where 0 = no pain and 100 = worst imaginable pain). Thereafter, the patients were given 1 g paracetamol and 50–100 mg tramadol orally up to 4 times a day, as needed.

Mobilization

6 h postoperatively, a first attempt was made to mobilize the patient. The patient was asked to stand up and take 5–6 steps forward with the help of a frame. This was repeated on the first postoperative morning. The ability to walk was scored as yes or no. Mobilization was also assessed using the “time to up and go” (TUG) test (Podsiadlo and Richardson 1991). This test measures the time taken to rise from an armchair, walk 3 m, turn around, walk back to the chair, and sit down. Values of < 20 s indicate that the patient is independently mobile. The TUG test was carried out preoperatively and at 3, 7, and 14 days, and then 3 and 6 months after the operation.

Outcome measures

Home-readiness and hospital stay. The patient was considered ready for discharge when all of the following criteria were fulfilled: no or mild pain (VAS < 30 at rest) sufficiently controlled by oral analgesics; ability to walk with the aid of elbow crutches, to climb 8 stairs, and to eat and drink normally; and no evidence of any surgical complications. Home-readiness was first assessed after the bolus injection at 21 h postoperatively and at least 3 times daily thereafter until the patient was discharged. Length of hospital stay (LOS) was recorded as the actual time to discharge (the operative day was day 0).

Pain. Pain intensity was assessed using the VAS at 6, 12, 21, 22, and 27 h, on days 3, 7, and 14, and 3 and 6 months postoperatively. Pain was assessed at rest and on 60º of knee flexion. The patients were asked to complete a questionnaire regarding postoperative pain on days 1, 3, and 14.

Analgesic consumption. The PCA-morphine consumption was recorded from 0 to 24 h after the surgery. The oral analgesic consumption was recorded on postoperative days 1, 2, and 3–7.

Patient satisfaction. Patient satisfaction with the quality of analgesia was assessed using a verbal rating scale from 1 to 4 (excellent = 4, good = 3, inadequate = 2, poor =1) during the first, second, and third postoperative days and after 7 days.

Functional outcome. The maximum degree of knee flexion and extension achieved were recorded preoperatively and at 24 h postoperatively, at the time of discharge, on days 3, 7, and 14, and 3 and 6 months postoperatively. The Oxford knee score is a 12-item knee questionnaire that scores from 12 (best possible) to 60 (worst possible) (Jahromi et al. 2004). The Oxford knee score was recorded preoperatively, 2 weeks postoperatively, and 3 and 6 months postoperatively. EuroQol (EQ-5D) is a self-reported measure of health, scoring health from 0 to 1 where 0 represents poor health and 1 represents perfect health (Fransen and Edmonds 1999). The patients were given EQ-5D questionnaires preoperatively and at 3 and 6 months after the operation.

Adverse events. The incidences of nausea, vomiting, pruritus, and sedation were recorded on the first and second postoperative days. All complications, adverse events, and re-admissions to the hospital during the 6-month follow-up period were also recorded.

Statistics

Sample size calculations were performed using the time to fulfillment of discharge criteria as the primary endpoint. In a pilot study, we recorded the time to home discharge in 9 patients undergoing conventional surgery using LIA without postoperative bolus injection, and we found a mean of 3.2 (SD 1.7) days. In another group of patients who were operated with MIS using LIA (Essving et al. 2009), the mean time to home discharge was 1.7 (SD 1.5) days. Assuming the same SD (1.7) in both groups and using the t-test as the statistical method with 5% two-sided significance level and 80% power to detect a difference of 1.5 days, we calculated that 17 patients would be required in each group. Accounting for patient dropouts and the large standard deviation, we included 20 patients in each group.

Due to the lack of a Gaussian distribution for home-readiness (the primary endpoint), the Mann-Whitney-U test was used. The same method was also used for the length of hospital stay, VAS pain scores, morphine consumption, patient satisfaction scores, and knee function scores including the Oxford knee score and EQ-5D. The chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test was used for analysis of dichotomous data when appropriate. The results are presented as median (range), and for the primary endpoint, 95% confidence interval (CI) was obtained using the Hodge-Lehmann method. Knee extension and flexion were also analyzed using repeated-measures analysis of variance (ANOVA). The Bonferroni-Holm method was used for corrections for multiple measures of the secondary endpoints (Table 2) (Holm 1979). In Table 2, the unadjusted p-values are presented and the critical value after correction with Bonferroni-Holm is given in the footnote. Any p-value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Data were analyzed using SPSS software version 15.0 for Windows and STATA software release 11.

Table 2.

Outcome

| Outcome | MIS group Median (range) |

n a | CON group Median (range) |

n a | Difference MIS-CON (95% CI) |

p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Analgesic consumption (mg) | ||||||

| Morphine i.v. 0–24 h | 14 (0–63) | 20 | 8 (0–51) | 18 | 4 (–2 to 12) | 0.2 |

| Tramadol p.o. 24–48 h | 200 (0–400) | 20 | 200 (0–300) | 18 | 0 (–50 to 100) | 0.6 |

| Tramadol p.o. 48–72 h | 300 (0–400) | 20 | 250 (0–400) | 17 | 50 (–50 to 150) | 0.3 |

| Tramadol p.o. day 3–7 | 1000 (0–1700) | 20 | 900 (0–1400) | 15 | 200 (–100 to 600) | 0.2 |

| Knee extension (degrees) | ||||||

| Preoperatively | 5 (0–15) | 19 | 0 (0–10) | 20 | ||

| 24 h postoperatively | 5 (0–10) | 18 | 10 (0–15) | 16 | –5 (–5 to 0) | 0.03 b |

| Discharge | 5 (0–10) | 19 | 10 (0–15) | 16 | –5 (–5 to 0) | 0.05 |

| 3 days postoperatively | 5 (0–15) | 19 | 10 (0–15) | 15 | 0 (–5 to 0) | 0.3 |

| 7 days postoperatively | 5 (0–15) | 18 | 8 (0–15) | 16 | 0 (–5 to 0) | 0.4 |

| 14 days postoperatively | 5 (0–10) | 19 | 10 (0–20) | 16 | 0 (–5 to 0) | 0.3 |

| 3 months postoperatively | 0 (0–10) | 17 | 2.5 (0–10) | 16 | 0 (–5 to 0) | 0.4 |

| 6 months postoperatively | 0 (–5–5) | 14 | 0 (0–5) | 16 | 0 (0 to 0) | 0.2 |

| Knee flexion (degrees) | ||||||

| Preoperatively | 120 (110–130) | 19 | 120 (105–135) | 17 | ||

| 24 h postoperatively | 102 (35–130) | 18 | 95 (60–110) | 16 | 10 (–5 to 20) | 0.1 |

| Discharge | 105 (30–130) | 19 | 92 (60–110) | 16 | 10 (–5 to 20) | 0.1 |

| 3 days postoperatively | 90 (50–115) | 19 | 80 (25–140) | 15 | 5 (–10 to 15) | 0.5 |

| 7 days postoperatively | 95 (50–110) | 18 | 90 (40–115) | 16 | 5 (–5 to 15) | 0.4 |

| 14 days postoperatively. | 95 (70–115) | 19 | 90 (70–115) | 16 | 5 (–5 to 15) | 0.3 |

| 3 months postoperatively | 120 (105–135) | 17 | 115 (95–130) | 18 | 5 (0 to 10) | 0.2 |

| 6 months postoperatively | 125 (110–140) | 14 | 120 (105–135) | 16 | 5 (0 to 10) | 0.1 |

| TUG test (seconds) | ||||||

| Preoperatively | 8 (4–12) | 19 | 10 (5–19) | 17 | ||

| 24 hours postoperatively | 18 (12–54) | 16 | 19 (8–54) | 15 | –1 (–5 to 4) | 0.8 |

| 3 days postoperatively | 18 (9–30) | 17 | 14 (10–32) | 15 | 2 (–1 to 6) | 0.2 |

| 7 days postoperatively | 13 (8–20) | 18 | 12 (9–27) | 15 | 0 (–3 to 3) | 0.9 |

| 14 days postoperatively | 12 (6–17) | 19 | 12 (7–22) | 16 | –1 (–3 to 2) | 0.6 |

| 3 months postoperatively | 7 (4–10) | 17 | 7 (5–11) | 15 | –1 (–2 to 1) | 0.4 |

| 6 months postoperatively | 7 (4–9) | 14 | 7 (4–10) | 16 | 0 (–2 to 1) | 0.3 |

| Patient satisfaction | ||||||

| 1 day postoperatively | 4 (2–4) | 18 | 4 (3–4) | 14 | 0 (0 to 0) | 0.9 |

| 2 days postoperatively | 3 (1–4) | 18 | 3 (2–4) | 15 | 0 (–1 to 0) | 0.5 |

| 3 days postoperatively | 3 (2–4) | 18 | 3 (2–4) | 15 | 0 (–1 to 0) | 0.7 |

| 7 days postoperatively | 3 (2–4) | 18 | 3 (2–4) | 15 | 0 (–1 to 0) | 0.6 |

| Oxford knee score | ||||||

| Preoperatively | 34 (26–43) | 19 | 34 (22–45) | 17 | ||

| 14 days postoperatively | 31 (22–53) | 17 | 30 (20–46) | 17 | 1 (–4 to 6) | 0.6 |

| 3 months postoperatively | 22 (16–38) | 16 | 22 (14–42) | 14 | 0 (–5 to 5) | 0.8 |

| 6 months postoperatively | 16 (13–26) | 14 | 17 (12–27) | 15 | –1 (–4 to 3) | 0.8 |

| EQ-5D | ||||||

| Preoperatively | 0.66 (0.09–0.80) | 20 | 0.69 (0.03–0.80) | 17 | ||

| 3 months postoperatively | 0.80 (0.66–1) | 16 | 0.85 (0.03–1) | 15 | 0 (–0.2 to 0.1) | 0.6 |

| 6 months postoperatively | 1 (0.66–1) | 14 | 1 (0.69–1) | 15 | 0 (–0.1 to 0.1) | 0.8 |

a The number of patients who participated varied depending on the patient’s ability to cooperate.

TUG test: “Timed-up-and-go” test.

Patient satisfaction: poor = 1; inadequate = 2; good = 3; excellent = 4.

Oxford knee score: 12 (best possible score) to 60 (worst possible score).

EQ-5D health outcome: 1 = perfect health; 0 = poor health.

b After Bonferroni-Holm correction, the critical value was 0.001 (0.05/33).

Results

Patients

2 patients, both in the CON group, were excluded after randomization due to intraoperative conversion to total knee arthroplasty; thus 38 patients completed the study protocol (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic data and duration of surgery a

| MIS group (n = 20) |

CON group (n = 20) |

|

|---|---|---|

| No. of females/males | 10/10 | 13/7 |

| Age, years | 62 (6) | 66 (7) |

| Weight, kg | 83 (15) | 87 (24) |

| Height, cm | 170 (9) | 165 (23) |

| BMI | 29 (4) | 28 (4) |

| ASA, I / II / III b | 9/11/0 | 7/13/0 |

| Operation time, min | 79 (8) | 73 (8) |

a Values are mean (SD), except for ASA and the number of females/males where the number of patients is shown.

b ASA physical status I: normal health; II: systemic disease with no limited activity; III: systemic disease with limited activity.

BMI: body mass index;

MIS: minimally invasive surgery;

CON: conventional exposure.

Primary endpoint

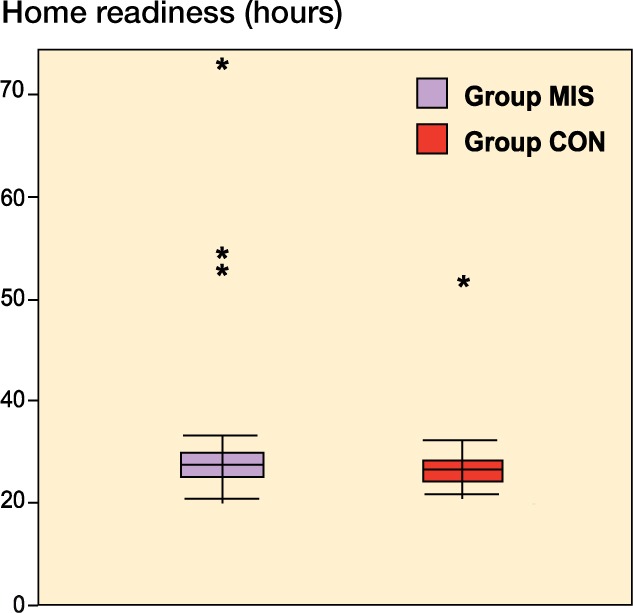

No statistically significant difference in home-readiness (time to fulfillment of discharge criteria) was found between the groups: median 24 (21–71) h in the MIS group compared to 24 (21–46) h in the CON group (p = 0.6), i.e. a difference of 0 (–1 to 2) h (Figure 2). The per-protocol principle was used for this analysis. Analysis using the intention-to-treat principle was not possible since the 2 excluded patients underwent a different procedure during the operation and did not receive the same postoperative treatment; thus, their home-readiness was not recorded. A sensitivity analysis was therefore performed, giving the 2 excluded patients either the highest or the lowest recorded value in the study. This analysis did not reveal any statistically significant differences.

Figure 2.

Home-readiness (time to fulfillment of all discharge criteria) is presented as median and interquartile range (IQR). The asterisks represent outliers with scores of more than 3 times the IQR. No statistically significant difference was found between the groups.

Secondary endpoints

There was no significant difference in length of hospital stay (LOS) between the groups: median 1 day (1–3) in the MIS group and 1 day (1–2) in the CON group (p = 0.7). The proportion of patients who were discharged during the first postoperative day was similar in both groups: 16 of 20 in the MIS group and 15 of 18 in the CON group. After 2 days, only 1 patient in group MIS remained in hospital; this patient was discharged on postoperative day 3.

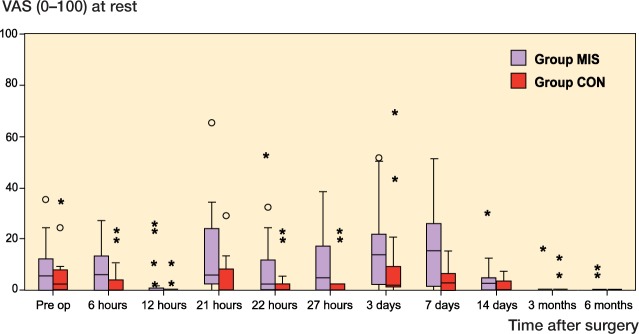

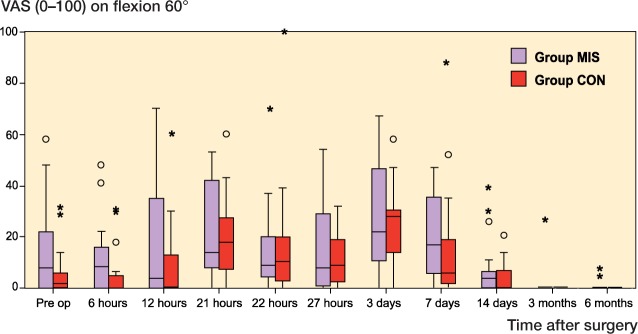

We did not find any statistically significant differences in postoperative pain intensity at rest or on flexion at any time point postoperatively (Figures 3 and 4). Median VAS pain scores were below 25 mm at all time points in both groups. The highest median VAS pain score at rest occurred on day 7 (17 mm in the MIS group) and for flexion on day 3 (24 mm in the MIS group).

Figure 3.

Pain at rest assessed using VAS and presented as median and interquartile range. The circles represent outliers with scores of more than 1.5 times the IQR, and the asterisks represent outliers with scores of more than 3 times the IQR. No statistically significant differences were found between the groups.

Figure 4.

Pain on flexion using VAS and presented as median and interquartile range. The circles represent outliers with scores of more than 1.5 times the IQR, and the asterisks represent outliers with scores of more than 3 times the IQR. No statistically significant differences were found between the groups.

We found no statistically significant differences in analgesic consumption between the groups (Table 2).

The functional outcome—including patient satisfaction, Oxford knee score, and EQ-5D—was similar in both groups (Table 2). Although there were numerical differences in the maximum knee extension and knee flexion between the groups, with better results in the MIS group, these differences did not reach statistical significance. Repeated-measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) was also performed for knee extension and flexion, but this did not reveal any statistically significant differences. No differences were found in the ability to walk with a frame 6 h postoperatively. At this time, 14 of the 17 patients in the MIS group were able to walk as compared to 13 of the 15 patients in the CON group.

We did not find any statistically significant differences between groups regarding the incidence of nausea (10 vs. 6), vomiting (6 vs. 3), pruritus (2 vs. 1), and sedation (0 vs. 0) on the first postoperative day. On the second postoperative day, there was a higher incidence of nausea in the MIS group than in the CON group, 13 vs. 3 (p = 0.006), but no significant differences between groups were found for vomiting (1 vs. 0), pruritus (3 vs. 2), or sedation (0 vs. 0).

None of the patients showed any signs of systemic toxicity of local anesthetic agents. No major surgical complications were encountered in any of the patients during the 6-month follow-up period. No patients were re-admitted to hospital because of postoperative (surgical) complications.

A positive solitary culture of coagulase-negative Staphylococcus was obtained from 1 catheter tip; however, there was no clinical evidence of local or systemic infection in the patient and no antibiotics were administered.

Discussion

Unicompartmental knee arthroplasty using minimally invasive surgery has been successfully used at our institution for over 13 years. Several advantages of using MIS for UKA have been reported: shorter incision, quicker mobilization (Price et al. 2001), and earlier discharge home (Carlsson et al. 2006). However, many surgeons hesitate to use MIS for UKA because it is a somewhat more demanding technique than conventional surgery and it entails a longer learning curve. In addition, the smaller exposure impairs visualization during surgery, which might jeopardize the preparation of the joint surfaces, positioning of the implants, and removal of superfluous bone cement. In this study, we investigated whether MIS for UKA would provide better outcome than the conventional technique, which uses a longer incision and offers better visualization.

Surprisingly, we found no difference between the surgical approaches for our primary endpoint, home-readiness. There could be several possible explanations for this. We used the local infiltration technique intraoperatively, and 1 postoperative bolus injection in both groups. In addition, we used a higher dose of ropivacaine (400 mg) than the dose used in our earlier study on UKA (Essving et al. 2009). Median VAS pain scores were below 25 mm at all time points in both groups. Furthermore, the personnel in the ward may have become more aware of the importance of early mobilization in the last few years, which may have led to earlier home-readiness. It is also possible that the frequency of assessment of home-readiness in this study (3 times a day) may have had a positive effect on mobilization in both groups.

Our findings contrast with the results of some other studies. Price et al. (2001) found that patients who underwent UKA using MIS could be mobilized twice as fast as those who underwent conventional UKA. However, that was a retrospective analysis with no records of postoperative pain levels or LOS, and LIA was not used. In the only randomized study to date comparing MIS to conventional surgery, Carlsson et al. (2006) reported a mean difference in hospital stay of 3 days (3 vs. 6) in favor of MIS. However, they found no differences in postoperative pain or knee function, and a modified LIA technique with only 40 mL of 0.25% bupivacaine-adrenalin was used and no bolus injection was administered. We know from our long experience with LIA that it is an excellent technique for reducing postoperative pain and duration of hospital stay following UKA (Essving et al. 2009). Several other studies have found similar results when using LIA during total knee arthroplasty (Busch et al. 2006, Vendittoli et al. 2006, Andersen et al. 2008, Essving et al. 2010). In our previous study using LIA for UKA, the amount of rescue analgesic consumption was similar to that in the present study, thus confirming our previous findings (Essving et al. 2009). However, the dose of ropivacaine used in this study was greater than that used in our previous one. We know from an earlier study on total knee arthroplasty and LIA that intraarticular injection of 400 mg ropivacaine does not result in systemic toxicity of local anesthetics (Essving et al. 2010). We found no signs of systemic toxicity of LIA at this dose in the present study. [OK?] Thus, good pain relief was achieved in both groups and, since pain is one of the important limiting factors for mobilization, this may explain why there were no differences in the outcomes between minimally invasive surgery and conventional surgery. Although there was a tendency of better flexion and extension in the MIS group, this was not statistically significant.

There is a possible risk of local toxicity from ropivacaine injected intraarticularly. Chondrolysis associated with the use of bupivacaine injected intraarticularly has been reported after shoulder surgery (Hansen et al. 2007). In knee arthroplasty, this is mainly of concern after UKA, since there is cartilage remaining in the joint, which may be damaged by the use of IA bupivacaine. Piper and Kim (2008) did not find any evidence of chondrotoxicity when ropivacaine was injected in vitro. Grishko et al. (2010) did not find any effect of ropivacaine on chondrocyte viability, but they found an increase in the number of apoptotic cells. In the present study, we have seen no clinical evidence of any chondrolysis during the 6 months of follow-up. 2 patients had residual pain in the medial part of the knee at the 6-month follow-up. Clinical and radiographic examination of these patients did not show any signs of implant loosening or lateral chondral damage. The LIA technique using ropivacaine has been administered in a great number of knee arthroplasties in Scandinavia during the last decade, and so far there have been no reports indicating chondrotoxicity. However, this risk remains a major concern—specifically when using bupivacaine, and patients should therefore be monitored closely and over a longer period of time.

There were few side effects and complications and there were no significant differences between the groups, except for the incidence of nausea on postoperative day 2, which was lower in conventional surgery group than in the MIS group. However, since there was no difference in PCA-morphine consumption between the groups, it is difficult to explain this finding.

Limitations of the study

The present study had some limitations. First, a larger sample size might have detected a difference in our primary endpoint between the groups. A larger study might have found statistically significant differences that were not clinically meaningful, however. In addition, the narrow confidence interval in the difference between the groups indicated that we had valid findings, and that there is no clinically important difference between the two surgical methods. Another limitation was that our study was not blinded and was therefore open to problems of observer bias. However, despite this potential bias in favor of MIS, we found no differences between the groups. The next question is whether there would have been a difference in home-readiness between the groups if we had refrained from using LIA in both groups. This model might have answered the question regarding the best technique for performing UKA. However, the results would then not have been applicable to our current clinical practice and would have lacked external validity, since LIA is used routinely not only in our hospital but also in the majority of hospitals in Sweden (The Swedish Knee Arthroplasty Register 2011). Finally, one could argue that a different implant model and instruments may have given other results. However, we have used the same system for over 20 years and performed MIS during UKA for over 13 years with this system and we have not encountered any problems.

Our results could call into question the routine use of MIS during UKA. The present study indicates that when using LIA, conventional UKA may provide acceptable postoperative pain levels and early mobilization. Since UKA is a technically demanding procedure, and since performing it with MIS makes it even more challenging for the surgeon, it can be argued that with the good postoperative pain relief achieved using LIA, conventional UKA is a good alternative to MIS.

In conclusion, we did not find that MIS offers any advantages over the conventional surgical technique in terms of home-readiness, mobilization, or functional recovery after unicompartmental knee arthroplasty, when postoperative pain relief is achieved using LIA. Local practices and the surgeon’s method of choice can be used to determine the surgical approach for UKA in each hospital.

Acknowledgments

PE: enrollment of patients, surgery, data analysis, and writing of the manuscript. KA, AG, and AL: data analysis and writing of the manuscript. LO and HS: collection of data and contribution to the manuscript. AM: data analysis and contribution to the manuscript.

We thank the personnel of the operating theaters and the wards for their help during the various phases of the study.

No competing interests declared.

References

- Andersen LO, Husted H, Otte KS, Kristensen BB, Kehlet H. High-volume infiltration analgesia in total knee arthroplasty: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2008;52:1331–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-6576.2008.01777.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berend KR, Lombardi AV., Jr Liberal indications for minimally invasive Oxford unicondylar arthroplasty provide rapid functional recovery and pain relief. Surg Technol Int. 2007;16:193–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busch CA, Shore BJ, Bhandari R, Ganapathy S, MacDonald SJ, Bourne RB, Rorabeck CH, McCalden RW. Efficacy of periarticular multimodal drug injection in total knee arthroplasty. A randomized trial. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 2006;88:959–63. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.E.00344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlsson LV, Albrektsson BE, Regner LR. Minimally invasive surgery vs conventional exposure using the Miller-Galante unicompartmental knee arthroplasty: a randomized radiostereometric study. J Arthroplasty. 2006;21:151–6. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2005.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Essving P, Axelsson K, Kjellberg J, Wallgren O, Gupta A, Lundin A. Reduced hospital stay, morphine consumption, and pain intensity with local infiltration analgesia after unicompartmental knee arthroplasty. Acta Orthop. 2009;80:213–9. doi: 10.3109/17453670902930008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Essving P, Axelsson K, Kjellberg J, Wallgren O, Gupta A, Lundin A. Reduced morphine consumption and pain intensity with local infiltration analgesia (LIA) following total knee arthroplasty. Acta Orthop. 2010;81:354–60. doi: 10.3109/17453674.2010.487241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fransen M, Edmonds J. Gait variables: appropriate objective outcome measures in rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 1999;38:663–7. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/38.7.663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grishko V, Xu M, Wilson G, Pearsall AW. Apoptosis and mitochondrial dysfunction in human chondrocytes following exposure to lidocaine, bupivacaine, and ropivacaine. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 2010;92:609–18. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.H.01847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen BP, Beck CL, Beck EP, Townsley RW. Postarthroscopic glenohumeral chondrolysis. Am J Sports Med. 2007;35(10):1628–34. doi: 10.1177/0363546507304136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holm S. Simple sequentially rejective multiple test procedure. Scand J Stat. 1979;6:65–70. [Google Scholar]

- Jahromi I, Walton NP, Dobson PJ, Lewis PL, Campbell DG. Patient-perceived outcome measures following unicompartmental knee arthroplasty with mini-incision. Int Orthop. 2004;28:286–9. doi: 10.1007/s00264-004-0573-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerr DR, Kohan L. Local infiltration analgesia: a technique for the control of acute postoperative pain following knee and hip surgery: a case study of 325 patients. Acta Orthop. 2008;79:174–83. doi: 10.1080/17453670710014950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khanna A, Gougoulias N, Longo UG, Maffulli N. Minimally invasive total knee arthroplasty: a systematic review. Orthop Clin North Am. 2009;40:479–89. doi: 10.1016/j.ocl.2009.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piper SL, Kim HT. Comparison of ropivacaine and bupivacaine toxicity in human articular chondrocytes. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 2008;90(5):986–91. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.G.01033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Podsiadlo D, Richardson S. The timed “Up & Go”: a test of basic functional mobility for frail elderly persons. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1991;39:142–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1991.tb01616.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price AJ, Webb J, Topf H, Dodd CA, Goodfellow JW, Murray DW. Rapid recovery after oxford unicompartmental arthroplasty through a short incision. J Arthroplasty. 2001;16:970–6. doi: 10.1054/arth.2001.25552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reilly KA, Beard DJ, Barker KL, Dodd CA, Price AJ, Murray DW. Efficacy of an accelerated recovery protocol for Oxford unicompartmental knee arthroplasty--a randomised controlled trial. Knee. 2005;12:351–7. doi: 10.1016/j.knee.2005.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Repicci JA, Eberle RW. Minimally invasive surgical technique for unicondylar knee arthroplasty. J South Orthop Assoc. 1999;8:20–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rostlund T, Kehlet H. High-dose local infiltration analgesia after hip and knee replacement--what is it, why does it work, and what are the future challenges? Acta Orthop. 2007;78:159–61. doi: 10.1080/17453670710013627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Swedish Knee Arthroplasty Register. http://www.knee.nko.se/english/online/uploadedFiles/115_SKAR2011_Eng1.0.pdf Annual Report 2011. [cited 2012 4 Jan] Available from:

- Vendittoli PA, Makinen P, Drolet P, Lavigne M, Fallaha M, Guertin MC, Varin F. A multimodal analgesia protocol for total knee arthroplasty. A randomized, controlled study. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 2006;88:282–9. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.E.00173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]