Abstract

Background

Preclinical Diastolic Dysfunction (PDD) has been broadly defined as subjects with left ventricular diastolic dysfunction, without the diagnosis of congestive heart failure (HF), and with normal systolic function. Our objective was to determine the risk factors associated with the progression from PDD (Stage B HF) to symptomatic (Stage C) HF.

Methods and Results

Using the resources of the Rochester Epidemiology Project, all residents of Olmsted County, MN who underwent echocardiography between 1/1/2004 and 12/31/2005 and had Grade 2-4 diastolic dysfunction (DD) and EF ≥ 50% were identified. Patients with a diagnosis of HF prior to or within 30 days of the echocardiogram were excluded. Patients were also excluded if they had a diagnosis of atrial fibrillation or severe mitral or aortic valve regurgitation at the time of the echocardiogram. A total of 388 patients met the inclusion criteria. The mean age of the cohort was 67 ± 12 years with a female (57%) predominance. Prevalence of renal insufficiency (estimated GFR <60ml/min/1.73 m2) was 34%. The 3-year cumulative probabilities of development of (Stage C) HF, development of atrial fibrillation, cardiac hospitalization, and mortality were 11.6%, 14.5%, 17.7%, and 10.1% respectively. In multivariable Cox’s proportional hazard regression analysis, we determined that age, renal dysfunction, and right ventricular systolic pressure were independently associated with the development of HF.

Conclusions

This population-based study demonstrated that in PDD (Stage B HF), there was a moderate degree of progression to symptomatic (Stage C) HF over 3 years and renal dysfunction was associated with this progression independent of age, sex, hypertension, coronary disease, and ejection fraction.

Keywords: diastolic dysfunction, heart failure, preserved ejection fraction

Heart failure (HF) is an epidemic with a prevalence of 5.3 million in Americans aged 20 and older in 2005. 1 It is being increasingly recognized that 30-50% of HF patients have normal or near-normal ejection fraction (EF) and multiple studies have shown that HF with preserved EF (HFpEF) carries a similar prognosis to HF with decreased systolic function. 2-9

In the AHA/ACCF classification of HF, stage B is defined as structural heart disease without signs/symptoms of HF.10 Preclinical diastolic dysfunction (PDD), which is part of Stage B HF, has therefore been defined as patients with diastolic dysfunction (DD), normal EF, and without HF symptoms/diagnosis. The importance of PDD is that these patients may progress to symptomatic HF and they are at increased risk for adverse cardiac events including atrial fibrillation (AF).11, 12 Despite this importance, there are few studies which have focused on the natural history of PDD.

In a population-based study from Olmsted County, Minnesota, the prevalence of mild PDD was 20.6% and moderate to severe PDD was 6.8% among subjects 45 years and older. In addition, it was shown that PDD patients had higher mortality than subjects with normal diastolic function.5 These findings were similar to another population-based study from Canberra, Australia, which found a prevalence of 23.5% for mild DD with normal EF and 5.6% for moderate or severe DD with normal EF.13

Beyond these prevalence data, we have recently reported that among a small cohort of PDD subjects the 2-year cumulative probability of development of any HF symptoms was 31.1%. Furthermore, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, coronary artery disease, and renal dysfunction were prevalent in PDD.14 However, our previous study was limited to only 82 patients and a short mean follow-up of 721 days.

It is notable that for symptomatic HF patients, it has been previously shown that renal dysfunction is an independent predictor of all-cause mortality. However, to this point, it has remained unclear whether or not renal dysfunction holds prognostic value for PDD patients. 15

Our objectives were to confirm and extend our previous preliminary findings, to determine the clinical phenotype and natural history of PDD, and to identify clinical characteristics that could predict the progression to symptomatic HF. To the best of our knowledge, our study is the largest to date focused broadly on PDD patients.

Methods

Study setting

This study was approved by the Mayo Clinic and Olmsted Medical Center Institutional Review Boards. Population-based epidemiological research is feasible in Olmsted County, Minnesota, because all care is provided by either Mayo Clinic or Olmsted Medical Center which together maintain a unified medical record which is sustained by the Rochester Epidemiology Project. 16 This record includes an indexed diagnosis for every medical encounter including outpatient, inpatient, emergency department, and death certification.16, 17

We utilized the resources of the Rochester Epidemiology Project and the Mayo Clinic echocardiography database to identify all patients in Olmsted County, Minnesota, who underwent echocardiography between 1/1/2004 and 12/31/2005. For included patients, the first echocardiogram during this period is subsequently referred to as the inclusion echocardiogram. Inclusion criteria were echocardiographic evidence of grade 2-4 diastolic dysfunction and EF ≥ 50%. Exclusion criteria were HF diagnosis prior to or within 30 days of the inclusion echocardiogram or AF at the time of the inclusion echocardiogram or severe mitral valve or aortic valve regurgitation. Data collection was obtained through complete review of the medical records both at Mayo Clinic and Olmsted Medical Center.

Echocardiographic data

Echocardiography was performed according to the guidelines of the American Society of Echocardiography and diastolic function was classified integrating pulsed-wave Doppler examination of mitral inflow before and during Valsalva maneuver and pulmonary venous inflow and Doppler tissue imaging of the mitral annulus.5, 18

Diastolic dysfunction was classified as: Grade 1 - impaired relaxation (E/A≤0.75, E/e’<10); Grade 1a - impaired relaxation (E/A≤0.75, E/e’>10); Grade 2 - “pseudonormal” pattern (0.75<E/A<1.5, DT>140 and PV S/D≥1 or E/e’≥ 10); Grade 3/4 - restrictive (E/A>1.5, &/or DT<140 ms &/or PV S/D <1≥ &/or E/e’ ≥ 10).5 We also collected data on left atrial volume (LAV) index and right ventricular systolic pressure (RVSP). E, early component of mitral filling; A, atrial component of mitral filling; E/A, ratio of the mitral early (E) and atrial (A) components of the mitral inflow velocity profile; e’, velocity of mitral annulus early diastolic motion; E/e’, ratio of early diastolic mitral inflow velocity and early diastolic mitral annular velocity; DT, deceleration time; PV, pulmonary vein; S, systolic forward flow; D, diastolic forward flow.

Additional data

For all included patients, the following data was collected from the medical record: inclusion echocardiogram information; co-morbidities; date of birth; gender; body mass index (BMI); laboratory values (electrolytes, creatinine, lipid panel) closest in time to the inclusion echocardiogram; and, if applicable, date of death. Glomerular filtration rate (GFR) was calculated via the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease (MDRD) equation.19

International Classification of Disease (ICD) and Diagnosis Related Group (DRG) codes were used to identify heart failure, AF, and all comorbidities. Specifically, heart failure patients were identified by searching the electronic medical record for a diagnosis of heart failure as denoted by International Classification of Disease (ICD9) code 428 and Diagnosis Related Group (DRG) codes 127, 291, 292, and 293. Atrial fibrillation patients were identified by searching the electronic medical record for a diagnosis of atrial fibrillation as denoted by International Classification of Disease (ICD9) code 427.

Mortality data was obtained via review of the medical records and confirmed via an automated check of registration data.

For those patients who developed HF, AF, or cardiac hospitalization, the medical record was reviewed in detail to gather the laboratory values listed above and also the complete blood counts were recorded that were closest in time to the date of the diagnosis and closest to the end of the follow-up period. Also, for these patients, cardiac medications were recorded closest in time after the inclusion echocardiogram, after the diagnosis of AF or HF, and closest to the end of the follow-up period.

Additionally, for patients who developed HF, the echocardiogram data closest to the date of diagnosis was recorded. Finally, hospitalization data was recorded for all cardiac hospitalizations during the follow-up period. A cardiac hospitalization was defined as a hospitalization during which any of the following were primary discharge diagnoses: heart failure, arrhythmias, valvular pathologies, coronary artery disease, and acute coronary syndromes. A manual review of the medical record was carried out to confirm the primary discharge diagnosis.

The beginning and end of follow-up were the inclusion echocardiogram and 6/30/2009 respectively. The primary endpoint was development of HF. The secondary endpoints were development of AF, cardiac hospitalization, and all-cause mortality. In addition, an analysis was completed for the composite endpoint of heart failure or death due to any cause.

Study Design

The study was retrospective in design since all events (exposures and outcomes) occurred prior to the start of the study period. The end of follow-up was 6/30/2009.

Statistical Analysis

Overall summaries were presented as means and standard deviations for continuous variables. Categorical variables were summarized as percentages. The cumulative probability of HF, AF, cardiac hospitalization, and death outcomes were estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method. Potential risk factors for these endpoints were evaluated using Cox proportional hazards models. The multivariable models were selected using a stepwise selection method. Only variables in the model that had a p-value of less than 0.10 were included in the final model. In addition, for those patients who developed HF we used a paired t-test to compare laboratory and echocardiographic parameters at the time of inclusion to those closest in time to HF diagnosis.

Results

Baseline Characteristics

388 patients were eligible and included. Mean follow-up was 3.9 years. Baseline clinical characteristics, cardiovascular co-morbidities and risk factors, laboratories, and inclusion echocardiogram information are reported in Table 1. Mean age was 67.1 years (SD 12.4) and there was a female preponderance, 57%. Cardiovascular diseases were prevalent: hypertension 87%, coronary artery disease 52%, history of myocardial infarction 24%, and peripheral vascular disease 11%. Cardiovascular disease risk factors were also prevalent: hyperlipidemia 76%, estimated GFR <60 ml/min/1.73m2 34%, and diabetes mellitus 30%. On the inclusion echocardiogram, the mean EF was 63.6% (SD 6.1). 368 patients (94.8%) had grade 2 DD, 18 (4.64%) had grade 3 DD, and 2 (0.52%) had grade 4 DD. RVSP was elevated at a mean of 37.5mmHg (SD 11.9) and the mean LAV index was 41.5 (SD 12.1).

Table 1.

Baseline clinical and echocardiography data for total cohort

| Variable | No. | Percent |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 388 (mean age 67.1, SD 12.4) | |

| Female Gender | 223 | 57 |

| BMI | 388 (mean BMI 29.2, SD 6.9) | |

| CV Co-morbidities | ||

| Hypertension | 338 | 87 |

| Coronary Artery Disease | 200 | 52 |

| Hx Myocardial Infarction | 94 | 24 |

| Peripheral Vascular Disease | 42 | 11 |

| CV Risk Factors | ||

| Hyperlipidemia | 293 | 76 |

| GFR <60 ml/min/1.73m2 | 133 | 34 |

| Diabetes Mellitus | 116 | 30 |

| Laboratories | Mean | SD |

| Total cholesterol | 170.5 | 39.9 |

| Triglycerides | 134.1 | 75.1 |

| HDL | 53.0 | 16.6 |

| LDL | 90.4 | 32.8 |

| BUN | 22.9 | 13.1 |

| Creatinine | 1.2 | 1.0 |

| Hemoglobin | 13.1 | 1.7 |

| Hematocrit | 38.3 | 4.9 |

| Sodium | 139.5 | 4.0 |

| Potassium | 4.3 | 0.5 |

| GFR | 72.0 | 33.2 |

| Echocardiography Data | ||

| DD Degree | Number | % |

| 2 | 368 | 95% |

| 3 | 18 | 5% |

| 4 | 2 | 1% |

| Mean | SD | |

| Ejection Fraction | 63.6 | 6.1 |

| E/e’ | 15.5 | 5.4 |

| E/A Baseline | 1.3 | 0.7 |

| DT Baseline | 200.6 | 38.6 |

| LAV Index | 41.5 | 12.1 |

| RVSP | 37.5 | 11.9 |

BMI, body mass index; CV, cardiovascular; Hx, history; GFR, glomerular filtration rate; SD, standard deviation; HDL, high density lipoprotein; LDL, low density lipoprotein; BUN, blood urea nitrogen; DD, diastolic dysfunction, E, early component of mitral filling; A, atrial component of mitral filling; E/A, ratio of the mitral early (E) and atrial (A) components of the mitral inflow velocity profile; e’, velocity of mitral annulus early diastolic motion; E/e’, ratio of early diastolic mitral inflow velocity and early diastolic mitral annular velocity; DT, deceleration time; LAV, left atrial volume.

Development of Heart Failure

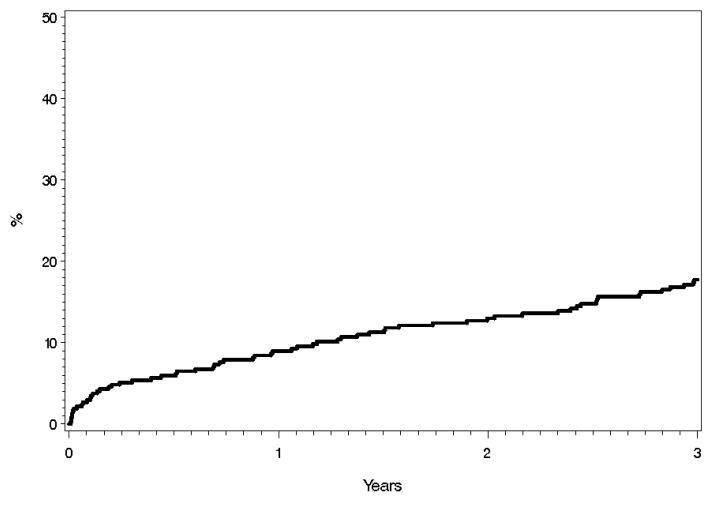

Fifty-one patients developed HF. The 1, 2, and 3 year cumulative probabilities for development of HF were 2.2%, 5.7%, and 11.6% respectively (Figure 1). Univariable analysis (Table 2) showed that age, E/e’ ratio, E/A ratio, RVSP, and GFR <60 ml/min/1.73m2 were significantly associated with the development of HF. Multivariable analysis (Table 3) showed that age, RVSP, and GFR <60 ml/min/1.73m2 were independently associated with the development of HF. Furthermore, for every 1 unit increase in the plasma Creatinine, the hazard of developing HF increased by 26% (HR=1.26, 95% CI=1.08-1.47; p=0.0039).

Figure 1.

Cumulative Probability of Development of Heart Failure by Kaplan-Meier

Table 2.

Univariable Analysis

| Outcome | HR | 95% CI | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Development of

Heart Failure |

|||

| Age | 1.067 | 1.035 – 1.100 | <0.001 |

| E/e’ Ratio | 1.063 | 1.021 – 1.106 | 0.003 |

| E/A Ratio | 1.327 | 1.049 – 1.680 | 0.019 |

| RVSP | 1.037 | 1.025 – 1.050 | <0.001 |

| GFR<60 ml/min/1.73m2 | 2.779 | 1.597 – 4.838 | <0.001 |

|

Development of

Atrial Fibrillation |

|||

| Age | 1.065 | 1.033 – 1.097 | <0.001 |

| Ejection Fraction | 1.052 | 1.003 – 1.102 | 0.036 |

| DD Grade | 2.213 | 1.148 – 4.264 | 0.018 |

| E/A Ratio | 1.413 | 1.133 – 1.762 | 0.002 |

| RVSP | 1.02 | 1.003 – 1.038 | 0.022 |

| GFR<60 ml/min/1.73m2 | 1.805 | 1.048 – 3.110 | 0.033 |

|

Cardiac

Hospitalization |

|||

| Age | 1.021 | 1.001 – 1.042 | 0.039 |

| LAV Index | 1.018 | 1.000 – 1.036 | 0.047 |

| CAD | 3.401 | 2.010 – 5.754 | <0.001 |

| COPD | 1.952 | 1.165 – 3.271 | 0.011 |

| HTN | 2.84 | 1.039 – 7.763 | 0.042 |

| MI | 3.373 | 2.168 – 5.249 | <0.001 |

| PVD | 2.663 | 1.574 – 4.505 | <0.001 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 2.079 | 1.099 – 3.931 | 0.024 |

| Mortality | |||

| Age | 1.069 | 1.036 – 1.104 | <0.001 |

| BMI | 0.927 | 0.880 – 0.977 | 0.005 |

| LAV Index | 1.02 | 1.002 – 1.038 | 0.029 |

| COPD | 1.883 | 1.003 – 3.535 | 0.049 |

| CVA | 2.243 | 1.241 – 4.053 | 0.007 |

| Hemoglobin | 0.692 | 0.527 – 0.909 | 0.008 |

| Hematocrit | 0.883 | 0.803 – 0.970 | 0.009 |

|

Composite

Endpoint of Heart Failure or Death |

|||

| Age | 1.066 | 1.042 - 1.089 | <0.001 |

| Female Gender | 1.564 | 1.026 - 2.384 | 0.038 |

| E/e’ Ratio | 1.034 | 1.001 - 1.069 | 0.043 |

| RVSP | 1.027 | 1.015 - 1.039 | <0.001 |

| CVA | 2.033 | 1.312 - 3.150 | 0.001 |

| GFR<60 ml/min/1.73m2 | 2.219 | 1.496 - 3.292 | <0.001 |

| BUN | 1.013 | 1.002 - 1.025 | 0.027 |

HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval; E, early component of mitral filling; A, atrial component of mitral filling; E/A, ratio of the mitral early (E) and atrial (A) components of the mitral inflow velocity profile; e’, velocity of mitral annulus early diastolic motion; E/e’, ratio of early diastolic mitral inflow velocity and early diastolic mitral annular velocity; RVSP, right ventricular systolic pressure; GFR, glomerular filtration rate; DD, diastolic dysfunction; CAD, coronary artery disease; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; HTN, hypertension; MI, myocardial infarction; PVD, peripheral vascular disease; BMI, body mass index; LAV, left atrial volume; CVA, history of cerebrovascular accident.

Table 3.

Multivariable Analysis

| Outcome | HR | 95% CI | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Development of

Heart Failure |

|||

| Age | 1.075 | 1.039 – 1.113 | <0.001 |

| RVSP | 1.053 | 1.036 – 1.071 | <0.001 |

| GFR<60 ml/min/1.73m2 | 2.003 | 1.122 – 3.577 | 0.019 |

|

Development of

Atrial Fibrillation |

|||

| Age | 1.063 | 1.031 – 1.096 | <0.001 |

| Ejection Fraction | 1.048 | 1.000 – 1.099 | 0.05 |

| E/A Ratio | 1.301 | 1.065 – 1.588 | 0.01 |

|

Cardiac

Hospitalization |

|||

| CAD | 2.066 | 1.127 – 3.788 | 0.019 |

| MI | 2.275 | 1.378 – 3.758 | 0.001 |

| PVD | 2.033 | 1.189 – 3.475 | 0.01 |

| Mortality | |||

| Age | 1.06 | 1.027 – 1.094 | <0.001 |

| BMI | 0.942 | 0.892 – 0.995 | 0.031 |

| LAV Index | 1.018 | 0.998 – 1.037 | 0.076 |

|

Composite

Endpoint of Heart Failure or Death |

|||

| Age | 1.058 | 1.033 – 1.083 | <0.001 |

| RVSP | 1.034 | 1.019 – 1.049 | <0.001 |

| CVA | 1.66 | 1.048 – 2.630 | 0.031 |

| GFR<60 ml/min/1.73m2 | 1.711 | 1.135 – 2.579 | 0.01 |

HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval; RVSP, right ventricular systolic pressure; GFR, glomerular filtration rate; E, early component of mitral filling; A, atrial component of mitral filling; E/A, ratio of the mitral early (E) and atrial (A) components of the mitral inflow velocity profile; CAD, coronary artery disease; MI, myocardial infarction; PVD, peripheral vascular disease; BMI, body mass index; LAV, left atrial volume; CVA, history of cerebrovascular accident.

We also wished to address whether the risk factors for the development of HF were equally predictive in the absence of diastolic abnormalities. Therefore, we included the Doppler E/e’ ratio, E/A ratio, LA volume index and deceleration time in our multivariable analysis. Even after adjusting for E/e’ ratio, E/A ratio, LA volume index and deceleration time we found that age, RSVP, and GFR<60 ml/min/1.73m2 remained independently associated with the development of HF in the multivariable analysis.

Of the 51 patients who developed HF, 33 (65%) had a subsequent echocardiogram after the inclusion echocardiogram. In this repeat echocardiogram there were no significant changes in EF, DD grade, E/e’, E/A, DT, or RVSP.

Development of Atrial Fibrillation

Fifty-two patients developed AF. The 1, 2, and 3 year cumulative probabilities for development of AF were 8.0%, 14.2%, and 14.5% respectively (Figure 2). Univariable analysis (Table 2) showed that age, EF, DD grade, E/A ratio, RVSP, and GFR <60 ml/min/1.73m2 were significantly associated with the development of AF. Multivariable analysis (Table 3) showed that age, EF, and E/A ratio were independently associated with the development of AF.

Figure 2.

Cumulative Probability of Development of Atrial Fibrillation by Kaplan-Meier

Cardiac Hospitalization

Seventy-nine patients experienced cardiac hospitalizations during the follow-up period. The 1, 2, and 3 year cumulative probabilities for cardiac hospitalization were 9.0%, 13.0%, and 17.7% respectively (Figure 3). Univariable Analysis (Table 2) showed that age, LAV index, CAD (coronary artery disease), COPD (chronic obstructive pulmonary disease), hypertension, MI (myocardial infarction), PVD (peripheral vascular disease), and hyperlipidemia were significantly associated with the development of a cardiac hospitalization. Multivariable analysis (Table 3) showed that CAD, MI, and PVD were independently associated with the development of a cardiac hospitalization. The most common discharge diagnoses were coronary artery disease (26, 33%) and atrial rhythm disorders (11, 14%).

Figure 3.

Cumulative Probability of Cardiac Hospitalization by Kaplan-Meier

Mortality

Fifty one patients died during the follow-up period. The 1, 2, and 3 year cumulative probabilities for all-cause mortality were 5.0%, 8.2%, and 10.1% respectively (Figure 4). Univariable analysis (Table 2) showed that age, BMI, LAV index, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, cerebrovascular accident (CVA), hemoglobin, and hematocrit were significantly associated with mortality. Multivariable analysis (Table 3) showed that age and BMI were independently associated with mortality and LAV index approached but did not meet significance (p-value 0.076).

Figure 4.

Cumulative Probability of All Cause Mortality by Kaplan-Meier

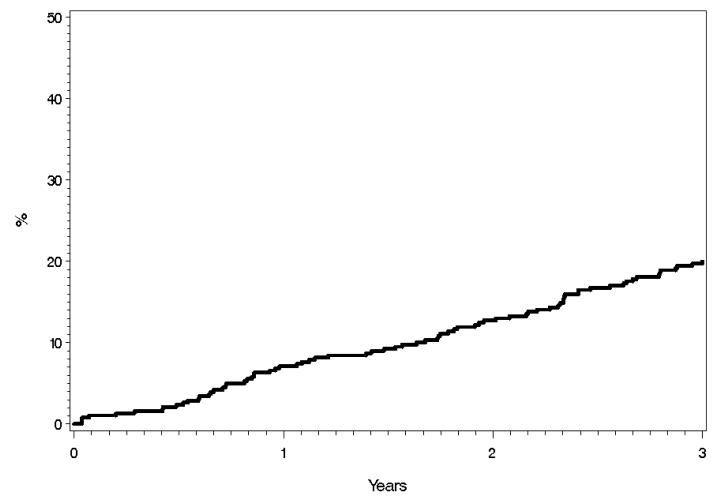

Composite endpoint for Heart Failure or Death due to any cause

Ninety nine patients developed the composite endpoint of heart failure or death due to any cause. The 1, 2, and 3 year cumulative probabilities for this composite endpoint were 7.1%, 12.7%, and 20.0% respectively (Figure 5). Univariable analysis (Table 2) showed that age, female gender, E/e’ Ratio, RVSP, CVA, GFR <60 ml/min/1.73m2, and BUN were significantly associated with the composite endpoint. Multivariable analysis (Table 3) showed that age, RVSP, CVA, and GFR <60 were independently associated with the composite endpoint.

Figure 5.

Cumulative Probability of Heart Failure or Death by Kaplan-Meier

Other Composite Endpoints

Eighty seven patients developed the composite endpoint of heart failure or atrial fibrillation and 113 patients developed the composite endpoint of heart failure or cardiac hospitalization.

Discussion

The current study confirmed the findings of previous studies which showed that PDD (Stage B HF) patients are commonly female, elderly, and have a high prevalence of cardiovascular comorbidities and risk factors. Our study also extended previous PDD studies by demonstrating that the 3-year cumulative probabilities of development of (Stage C) HF, cardiac hospitalization, development of AF, and mortality were 11.6%, 17.7%, 14.5%, and 10.1% respectively. Most importantly, we report for the first time that renal insufficiency, defined as estimated GFR <60 ml/min/1.73m2, was independently associated with the progression of PDD to overt HF (Stage C) after adjustment for age, sex, BMI, hypertension, coronary disease, EF, left atrial volume, and deceleration time. Furthermore, we found that age, RVSP, CVA, and GFR <60 ml/min/1.73m2 were independently associated with the composite endpoint of heart failure or death due to any cause.

At present, there are currently no specific therapeutic approaches which have been proven to decrease mortality in patients with HFpEF. Both this and the knowledge that DD is thought to be the major cause of HFpEF (or diastolic heart failure, DHF) highlight the need for a better understanding of DD.20, 21

One area in which we are starting to have a more clear understanding of DD is its association with renal insufficiency. Previously, it has been shown that renal insufficiency is associated with adverse events in HF patients and in patients with left ventricular systolic dysfunction.22-24 It has also been specifically reported that there is a high prevalence of renal insufficiency in DD and DHF patients.4, 14, 25 However, with the finding of renal insufficiency being independently associated with the progression of PDD to overt HF, our study is, to the best of our knowledge, the first to show a prognostic significance for renal dysfunction in PDD patients. Indeed, we found that for every 1 unit increase in the plasma creatinine, the hazard of developing HF increased by 26% (HR=1.26, 95% CI=1.08-1.47; p=0.0039).

In addition to age and renal insufficiency, RVSP was also independently associated with the progression of PDD to (Stage C) HF. This complements the work by Lam et al. who found that pulmonary arterial hypertension was present in 83% of HFpEF patients.26 In addition, it was found that pulmonary artery systolic pressure strongly predicted mortality in HFpEF patients. In combination with the findings from the present study, these data suggest that in addition to optimizing renal function, monitoring for and treating pulmonary arterial hypertension may be of particular significance in the management of DD and HFpEF.

In our study, we found a moderate degree of progression from PDD (Stage B HF) to symptomatic HF (Stage C) with 1, 2, and 3 year cumulative probabilities of 2.2%, 5.7%, and 11.6%, respectively. Of the 51 patients who developed (Stage C) HF in our study, 33 (64.7%) had a subsequent echocardiogram after the inclusion echocardiogram. It is notable that among these 33 patients, there were no significant changes in EF or DD grade indicating that the progression to HF was not simply due to a decline in systolic function or a progression of DD. This observation provides support for the discussion by Achong et al. who have suggested that the division of DD into stages or classes may erroneously imply that progression naturally occurs from one stage to the next.27 However, our study shows that there is a modest progression from PDD to HF and further work is needed to delineate the factors that influence this progression.

It has previously been shown by Redfield et al. that in the general population, even mild DD conferred an increased risk of mortality compared to subjects with normal diastolic function.5 Our study further shows that in PDD patients, there is also a moderate risk of death over 3 years with the 1, 2, and 3 year cumulative probabilities for all-cause mortality being 5.0%, 8.2%, and 10.1%, respectively. Diastolic dysfunction is also known to be associated with LA enlargement and thereby it increases the risk of AF. In addition, AF is likely to be poorly tolerated in subjects with PDD as the decrease in diastolic filling time and the loss of atrial contraction will result in increased LV end-diastolic-pressure. In our study, a diagnosis of AF was particularly common being present in 80 patients by the end of follow-up.

While our work was focused on PDD and did not address the natural history of preclinical systolic dysfunction (PSD) or asymptomatic left ventricular systolic dysfunction (ALVD) or the risk factors associated with progression of PSD or ALVD to symptomatic HF, we note that this has been well characterized previously in two key papers.

In a study focused on the natural history of ALVD (or PSD), Wang et al. from the Framingham group have shown that individuals with ALVD in the community are at high risk of HF and death even when only mild impairment of EF is present.28 In addition, Dries et al. published an elegant retrospective analysis of the Studies of Left Ventricular Dysfunction (SOLVD) Prevention Trial. In multivariate analyses it was shown that moderate renal insufficiency was associated with an increased risk for all-cause mortality in ALVD or PSD patients (RR 1.41; p<0.001) which was largely explained by an increased risk for pump-failure death (RR 1.68; p<0.007). In addition, moderate renal insufficiency was also associated with the combined end-point of death or hospitalization for heart failure (RR 1.33; p<0.001). In summary, it was concluded that moderate renal insufficiency was independently associated with an increased risk for all-cause mortality and HF progression in patients with ALVD or PSD.29

Additionally, although our study did not assess risk factors for the development of heart failure in the general population; this information is nicely summarized by the work of Listerman et al.30 The authors noted that, among other variables, renal insufficiency has been linked to increased risk for development of heart failure. Additionally, they noted that this risk persisted even after between group differences in other risk factors such as coronary artery disease were taken into account.

Furthermore, Dhingra et al recently studied the relationship between chronic kidney disease and nonfatal heart failure and cardiovascular death.31 They found that chronic kidney disease, even in absence of diabetes and hypertension at baseline, is associated with a higher risk of development of heart failure and the combined endpoint of cardiovascular death/heart failure in men.

By reflecting on these previous findings together with the findings of our own study we see that in PDD, PSD (or ALVD), and in the general population, renal function is an important prognostic indicator.

Limitations

The study was retrospective and our data relied heavily on the International Classification of Disease-9th revision coding variables to define HF. Although these codes have been validated as a diagnostic and research tool in Olmsted County, Minnesota, they do allow for potential bias. Also, because the majority of our patients had grade 2 DD this could certainly have impaired the analysis of echocardiography data as predictors of outcomes. In addition, the patients were not recruited from the community, but were clinically referred for echocardiography by their primary physicians, which may decrease the generalizability of the results. Also, although the diversity in Olmsted County is increasing, per the 2000 census, the characteristics of the Olmsted County population are similar to those of U.S. whites and these findings should, therefore, be examined in other racial and ethnic groups.16, 32 Additionally, we do not know if the risk factors for heart failure that we identified in PDD patients are also risk factors for the future progression of patients without PDD.

Conclusions

In this population based study our findings are consistent with previous studies which show that PDD (Stage B HF) patients are commonly female, elderly, and have a high prevalence of cardiovascular comorbidities and risk factors. Our study also showed a modest degree of progression from PDD to symptomatic heart failure (Stage C) over three years. In addition, by showing that renal insufficiency is independently associated with the progression of PDD to overt heart failure, our study is, to the best of our knowledge, the first to show a prognostic significance for renal dysfunction in PDD patients.

Acknowledgments

Sources of Funding This research was supported by grants from the NIH PO1 HL 76611, R01 HL-84155, the Rochester Epidemiology Project (Grant Number R01 AG034676 from the National Institute on Aging) and Mayo Foundation.

Footnotes

Disclosures None.

This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Lloyd-Jones D, Adams R, Carnethon M, De Simone G, Ferguson TB, Flegal K, Ford E, Furie K, Go A, Greenlund K, Haase N, Hailpern S, Ho M, Howard V, Kissela B, Kittner S, Lackland D, Lisabeth L, Marelli A, McDermott M, Meigs J, Mozaffarian D, Nichol G, O’Donnell C, Roger V, Rosamond W, Sacco R, Sorlie P, Stafford R, Steinberger J, Thom T, Wasserthiel-Smoller S, Wong N, Wylie-Rosett J, Hong Y. Heart disease and stroke statistics--2009 update: A report from the american heart association statistics committee and stroke statistics subcommittee. Circulation. 2009;119:e21–181. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.191261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Senni M, Redfield MM. Heart failure with preserved systolic function. A different natural history? J Am Coll Cardiol. 2001;38:1277–1282. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(01)01567-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen HH, Lainchbury JG, Senni M, Bailey KR, Redfield MM. Diastolic heart failure in the community: Clinical profile, natural history, therapy, and impact of proposed diagnostic criteria. J Card Fail. 2002;8:279–287. doi: 10.1054/jcaf.2002.128871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bursi F, Weston SA, Redfield MM, Jacobsen SJ, Pakhomov S, Nkomo VT, Meverden RA, Roger VL. Systolic and diastolic heart failure in the community. JAMA. 2006;296:2209–2216. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.18.2209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Redfield MM, Jacobsen SJ, Burnett JC, Jr., Mahoney DW, Bailey KR, Rodeheffer RJ. Burden of systolic and diastolic ventricular dysfunction in the community: Appreciating the scope of the heart failure epidemic. JAMA. 2003;289:194–202. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.2.194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Owan TE, Redfield MM. Epidemiology of diastolic heart failure. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2005;47:320–332. doi: 10.1016/j.pcad.2005.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Deswal A. Diastolic dysfunction and diastolic heart failure: Mechanisms and epidemiology. Curr Cardiol Rep. 2005;7:178–183. doi: 10.1007/s11886-005-0074-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hogg K, Swedberg K, McMurray J. Heart failure with preserved left ventricular systolic function; epidemiology, clinical characteristics, and prognosis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;43:317–327. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2003.07.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thomas MD, Fox KF, Coats AJ, Sutton GC. The epidemiological enigma of heart failure with preserved systolic function. Eur J Heart Fail. 2004;6:125–136. doi: 10.1016/j.ejheart.2003.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jessup M, Abraham WT, Casey DE, Feldman AM, Francis GS, Ganiats TG, Konstam MA, Mancini DM, Rahko PS, Silver MA, Stevenson LW, Yancy CW. 2009 focused update: Accf/aha guidelines for the diagnosis and management of heart failure in adults: A report of the american college of cardiology foundation/american heart association task force on practice guidelines: Developed in collaboration with the international society for heart and lung transplantation. Circulation. 2009;119:1977–2016. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.192064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tsang TS, Barnes ME, Gersh BJ, Takemoto Y, Rosales AG, Bailey KR, Seward JB. Prediction of risk for first age-related cardiovascular events in an elderly population: The incremental value of echocardiography. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;42:1199–1205. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(03)00943-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Takemoto Y, Barnes ME, Seward JB, Lester SJ, Appleton CA, Gersh BJ, Bailey KR, Tsang TS. Usefulness of left atrial volume in predicting first congestive heart failure in patients > or = 65 years of age with well-preserved left ventricular systolic function. Am J Cardiol. 2005;96:832–836. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2005.05.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Abhayaratna WP, Marwick TH, Smith WT, Becker NG. Characteristics of left ventricular diastolic dysfunction in the community: An echocardiographic survey. Heart. 2006;92:1259–1264. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2005.080150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Correa de Sa DD, Hodge DO, Slusser JP, Redfield MM, Simari RD, Burnett JC, Chen HH. Progression of preclinical diastolic dysfunction to the development of symptoms. Heart. 96:528–532. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2009.177980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mullens W, Abrahams Z, Skouri HN, Taylor DO, Starling RC, Francis GS, Young JB, Tang WH. Prognostic evaluation of ambulatory patients with advanced heart failure. Am J Cardiol. 2008;101:1297–1302. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2007.12.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Melton LJ., 3rd History of the rochester epidemiology project. Mayo Clin Proc. 1996;71:266–274. doi: 10.4065/71.3.266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kurland LT, Molgaard CA. The patient record in epidemiology. Sci Am. 1981;245:54–63. doi: 10.1038/scientificamerican1081-54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lang RM, Bierig M, Devereux RB, Flachskampf FA, Foster E, Pellikka PA, Picard MH, Roman MJ, Seward J, Shanewise J, Solomon S, Spencer KT, St John Sutton M, Stewart W. Recommendations for chamber quantification. Eur J Echocardiogr. 2006;7:79–108. doi: 10.1016/j.euje.2005.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Levey AS, Bosch JP, Lewis JB, Greene T, Rogers N, Roth D. A more accurate method to estimate glomerular filtration rate from serum creatinine: A new prediction equation. Modification of diet in renal disease study group. Ann Intern Med. 1999;130:461–470. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-130-6-199903160-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gandhi SK, Powers JC, Nomeir AM, Fowle K, Kitzman DW, Rankin KM, Little WC. The pathogenesis of acute pulmonary edema associated with hypertension. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:17–22. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200101043440103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zile MR, Baicu CF, Gaasch WH. Diastolic heart failure--abnormalities in active relaxation and passive stiffness of the left ventricle. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:1953–1959. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McAlister FA, Ezekowitz J, Tonelli M, Armstrong PW. Renal insufficiency and heart failure: Prognostic and therapeutic implications from a prospective cohort study. Circulation. 2004;109:1004–1009. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000116764.53225.A9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hillege HL, Girbes AR, de Kam PJ, Boomsma F, de Zeeuw D, Charlesworth A, Hampton JR, van Veldhuisen DJ. Renal function, neurohormonal activation, and survival in patients with chronic heart failure. Circulation. 2000;102:203–210. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.102.2.203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Al-Ahmad A, Rand WM, Manjunath G, Konstam MA, Salem DN, Levey AS, Sarnak MJ. Reduced kidney function and anemia as risk factors for mortality in patients with left ventricular dysfunction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2001;38:955–962. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(01)01470-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kuznetsova T, Herbots L, Lopez B, Jin Y, Richart T, Thijs L, Gonzalez A, Herregods MC, Fagard RH, Diez J, Staessen JA. Prevalence of left ventricular diastolic dysfunction in a general population. Circ Heart Fail. 2009;2:105–112. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.108.822627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lam CS, Roger VL, Rodeheffer RJ, Borlaug BA, Enders FT, Redfield MM. Pulmonary hypertension in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: A community-based study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;53:1119–1126. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.11.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Achong N, Wahi S, Marwick TH. Evolution and outcome of diastolic dysfunction. Heart. 2009;95:813–818. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2008.159020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang TJ, Evans JC, Benjamin EJ, Levy D, LeRoy EC, Vasan RS. Natural history of asymptomatic left ventricular systolic dysfunction in the community. Circulation. 2003;108:977–982. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000085166.44904.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dries DL, Exner DV, Domanski MJ, Greenberg B, Stevenson LW. The prognostic implications of renal insufficiency in asymptomatic and symptomatic patients with left ventricular systolic dysfunction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000;35:681–689. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(99)00608-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Listerman JHR, Geisberg C, Butler J. Risk factors for development of heart failure. Current Cardiology Reviews. 2007;3:1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dhingra R, Gaziano JM, Djousse L. Chronic kidney disease and the risk of heart failure in men. Circ Heart Fail. 2011;4:138–144. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.109.899070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.U.S. Census bureau . Census data for olmsted county, mn. U.S. Census; 2000. [Google Scholar]