Abstract

In this chapter, we summarize the isotopic labeling strategies used to obtain high-quality solution and solid-state NMR spectra of biological samples, with emphasis on integral membrane proteins (IMPs). While solution NMR is used to study IMPs under fast tumbling conditions, such as in the presence of detergent micelles or isotropic bicelles, solid-state NMR is used to study the structure and orientation of IMPs in lipid vesicles and bilayers. In spite of the tremendous progress in biomolecular NMR spectroscopy, the homogeneity and overall quality of the sample is still a substantial obstacle to overcome. Isotopic labeling is a major avenue to simplify overlapped spectra by either diluting the NMR active nuclei or allowing the resonances to be separated in multiple dimensions. In the following we will discuss isotopic labeling approaches that have been successfully used in the study of IMPs by solution and solid-state NMR spectroscopy.

Keywords: Isotopic labeling, Integral membrane proteins, Nuclear Magnetic Resonance, solution NMR, solid-state NMR, PISEMA

2. INTRODUCTION

Isotopic enrichment has been an integral part of the advancements made by nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy for the characterization of biomacromolecules at atomic resolution. The first pioneering studies on isotopically labeled proteins were carried out in the late ’60s, resulting in the production of isotopically labeled proteins extracted from organisms (bacteria and plants) cultured in media containing isotopically labeled nutrients [1–4]. In the past few years, there has been a true explosion of labeling schemes and production techniques that enable NMR spectroscopic studies of larger proteins and protein complexes greater than 100 kDa [5–7].

While most of the structural biology has been focusing on soluble proteins, outstanding progress is being made both in liquid and solid-state NMR for the structural analysis of membrane-bound proteins. In fact, an estimated 30% of all proteins synthesized in most organisms are integral membrane proteins [8, 9], which necessitate lipid environments to properly fold and function. IMPs are involved in signal transduction, transport of molecules across the membrane, conduction of ions and many other vital cellular processes [10–13]. Despite their importance, only 308 IMPs (http://blanco.biomol.uci.edu/mpstruc/listAll/list) have been deposited in the protein data bank (PDB) as of 2011, which is a rather exiguous number compared to the thousands of high-resolution structures determined for their soluble counterparts. There are several reasons for the paucity of high-resolution IMP structures. First of all, IMPs are difficult to express and purify in large amounts (tens of milligrams) and with the proper folding. Second, IMPs need lipids or detergents for structural and functional studies. The membrane mimetic environments coat the proteins forming large and slowly tumbling complexes that complicate NMR analysis. In recent years however, improvements in protein production systems, NMR hardware, pulse sequences and isotopic labeling strategies have made possible a number of successes in the study of IMPs [6, 14].

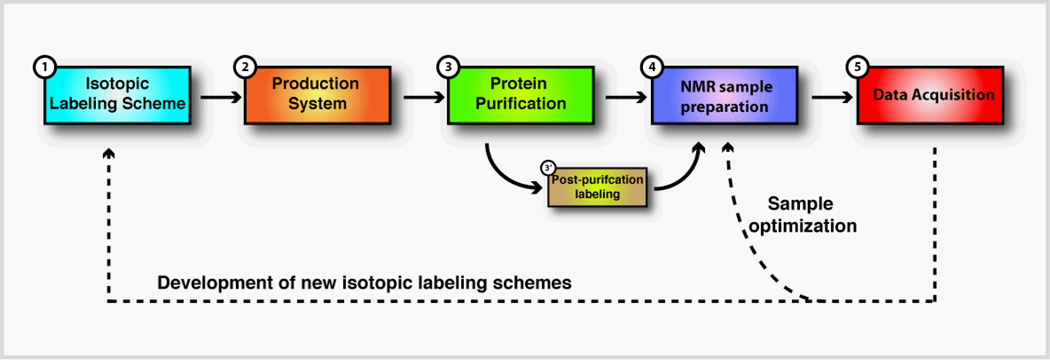

This chapter highlights the recent progress in isotopic labeling technologies to aid solution and solid-state NMR studies of IMPs. Although only four isotopes (1H, 15N, 13C, 2H) are routinely used in biomolecular NMR, there are several ways of introducing them along the amino acid sequence (see Figure 1). We focus on the recent progress from our laboratory and other research groups in the production of isotopically labeled IMPs for both liquid- and solid-state NMR studies. In addition, we review how isotopic labeling schemes can be exploited for studying protein-protein interactions in micelles and lipid vesicles. Finally, we will discuss some of the most common techniques to engineer spin-labels and isotopically labeled chemical groups to image large mammalian membrane proteins.

Figure 1.

Production of isotopic labeled membrane proteins for NMR spectroscopy

3. RECENT ADVANCES IN THE PRODUCTION OF IMPs

The main isotopes routinely used in protein NMR spectroscopy are 1H, 2H, 13C and 15N, with a more sparse use of 31P, 19F and 17O. Among the main isotopes, only 1H is found naturally at high abundance (>99.9 %), whereas the others must be artificially introduced in proteins. Isotopic labeling schemes can be divided into two broad categories: uniform and selective labeling. In the first category, we list all methods that produce a protein with uniform incorporation of NMR active isotope (i.e., uniformly 13C labeled or U-13C). Conversely, if a protein is enriched with an isotope only at particular sites, the protein will be defined as selective labeled.

Because of the inherent insensitivity of NMR, it is generally necessary to have an expression system capable of yielding milligram amounts of IMPs properly folded and biologically active. There are three well-established approaches: 1) heterologous overexpression, 2) total chemical synthesis and 3) cell-free expression. Depending on the protein under investigation each one of these approaches can be a viable choice. However, each system has advantages and drawbacks that need to be evaluated on a case-by-case basis.

3.1 Heterologous overexpression systems for membrane proteins

Heterologous overexpression consists of the use of living cells to synthesize proteins. It involves manipulation of the host DNA in such a way that the foreign gene is transcribed and translated at high levels. There are several heterologous systems for the expression and purification of IMPs [15–17], but the most widely used for isotopic labeling are: bacteria, yeasts, and insect cells. Each system has its own advantages and drawbacks, nonetheless a number of IMPs have been successfully produced for NMR studies [6]. When choosing an expression system, there are at least three important parameters to consider and eventually optimize: 1) the amount of final product (pure protein) per liter of growth medium, 2) whether the protein is properly folded and 3) whether biological activity of the expressed protein is retained.

3.1.1 Bacteria

The use of bacteria (especially E.coli strains) for heterologous expression of proteins was established in the 1980s when molecular cloning techniques became widely available [18]. Bacteria offer a number of advantages over other expression systems: they can grow at high densities in a variety of synthetic media, foreign genes can be readily inserted in their genome using simple molecular cloning techniques, and growth rates are fast (doubling time is on the order of 30 minutes). E.coli strains can be grown in fermenter vessels, where important parameters such as pH, temperature and dissolved oxygen are monitored to increase biomass and protein expression levels. Several strategies for efficient isotopic labeling of recombinant proteins in E.coli have been proposed [4, 19–21]. All these methods focus on obtaining high cell densities using inexpensive unlabeled media and subsequent transfer in labeled medium immediately before expression. High expression levels for IMPs have also been obtained using a clever manipulation of the common T7 expression system, which cause autoinduction of the recombinant gene [22].

A promising new strategy for the efficient expression of labeled proteins in E.coli is the single protein production system [23, 24]. By expression of an mRNA interferase (MazF) that cleaves RNA at ACA nucleotide sequences, it is possible to stop cellular growth. If the mRNA of the gene of interest is engineered so that no ACA sequences are present, MazF will not cleave it and translation will continue undisturbed. By using this expression system, it has been estimated that up to 30% of total cellular content is comprised of the recombinant protein, making it possible to acquire NMR spectra without substantial purification. When such a system is used for the production of isotopically labeled protein, the savings in terms of materials could be substantial. Indeed its success has been demonstrated by the production of several IMPs [23, 24].

Although E.coli is a robust and reliable host cell, it can present a number of problems for the expression of IMPs. Overexpression of IMPs is often toxic to the cell, thereby decreasing the viability of the cell itself. When IMPs are expressed at high levels they often tend to aggregate into inclusion bodies [25] which require unfolding and refolding strategies in order to extract the target protein. Although these problems can be circumvented by expressing the IMPs at lower temperature, or using soluble fusion tags, the IMPs might not be in an active form since E. coli bacteria do not possess post-translational modification machinery.

In addition to E.coli bacteria, other prokaryotes have been investigated for the overexpression of IMPs. The two most promising organisms are Pseudomonas Aeruginosa and Lactococcus lactis. P. Aeruginosa is a gram-negative bacterium that breaks down glucose using the Entner-Doudoroff pathway rather than glycolysis, producing alternative labeling patterns. McDermott and coworkers produced Pf1 coat protein labeled with 13C only at the carbonyl position by feeding P. aeruginosa with 1-13C-glucose [26]. Although this labeling scheme was used for solid-state NMR investigation of Pf1, it has great potential for studying the dynamics of IMPs by solution NMR as well.

The second promising prokaryote for the production of IMPs is L. lactis. This gram-positive bacterium offers several attractive features: 1) it has a single cellular membrane, which facilitates the insertion of heterologous IMPs and reduces the formation of inclusion bodies, 2) it can grow at high cell densities in the absence of oxygen and 3) it possesses a tightly regulated inducible expression system that uses the peptide nisin for induction [27]. IMPs have been successfully produced using this system [28], although the use for isotopic labeling in NMR studies has yet to be demonstrated.

3.1.2 Yeasts

The inability to introduce complex post-translational modifications and obtain properly folded and functional proteins are among the most significant drawbacks for the expression of IMPs in bacteria. A solution to these problems is to use more sophisticated expression systems, such as eukaryotic cells. The simplest and most studied eukaryotic systems for the expression of IMPs are yeasts such as Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Pichia pastoris.

Both systems have been used to produce many IMPs for NMR and X-ray studies [29, 30]. As for E.coli, yeast can be cultured in completely defined media composed of simple sugars and salts. Moreover, molecular biology techniques for the recombinant expression of foreign genes are available and readily applicable for the isotopic labeling of IMPs.

3.1.3 Higher eukaryotes

Other eukaryotic organisms have been used for the production of IMPs. The major advantage of using higher eukaryotes over simpler systems is the presence of more complex folding machinery and post-translational patterns. Some of the promising systems for the isotopic labeling of IMPs are baculovirus-infected insect cells and transfected mammalian cells. Recently, a simple and inexpensive protocol for the selective isotopic labeling of proteins in insect cells has been proposed [31]. Despite their utility, insect cells suffer from some important drawbacks: 1) cost of labeled media can be prohibitive, 2) deuteration has not yet been reported and 3) the yield of pure protein can be substantially lower than other systems.

Transfected mammalian cells are another useful system to express active and properly folded IMPs. Isotopically labeled IMPs have been produced with CHO and HEK293 cells at levels comparable to simpler systems [32]. Moreover, growth media for the incorporation of 15N and 13C are commercially available.

3.2 Total chemical synthesis

All the production systems described so far involve the use of living cells from different organisms. There are, however, chemical methods for the synthesis of proteins of up to 100 amino acids, which can be easily adapted for isotopic labeling purposes. Chemical synthesis is usually carried out using the standard solid-phase peptide synthesis (SPPS) developed by Merrifield and coworkers [33]. SPPS uses solid resins composed of beads with amino acids covalently linked to them. Protected amino acids are added to the reaction vessel where they form peptide bonds through a series of couplings and deprotection reactions. Thanks to microwave-assisted technologies which increase yields during difficult couplings or make more efficient use of isotopically labeled reagents during syntheses, it is now possible to routinely produce IMPs isotopically labeled at single sites in the primary sequence (Figure 2F and Figure 4C).

Figure 2.

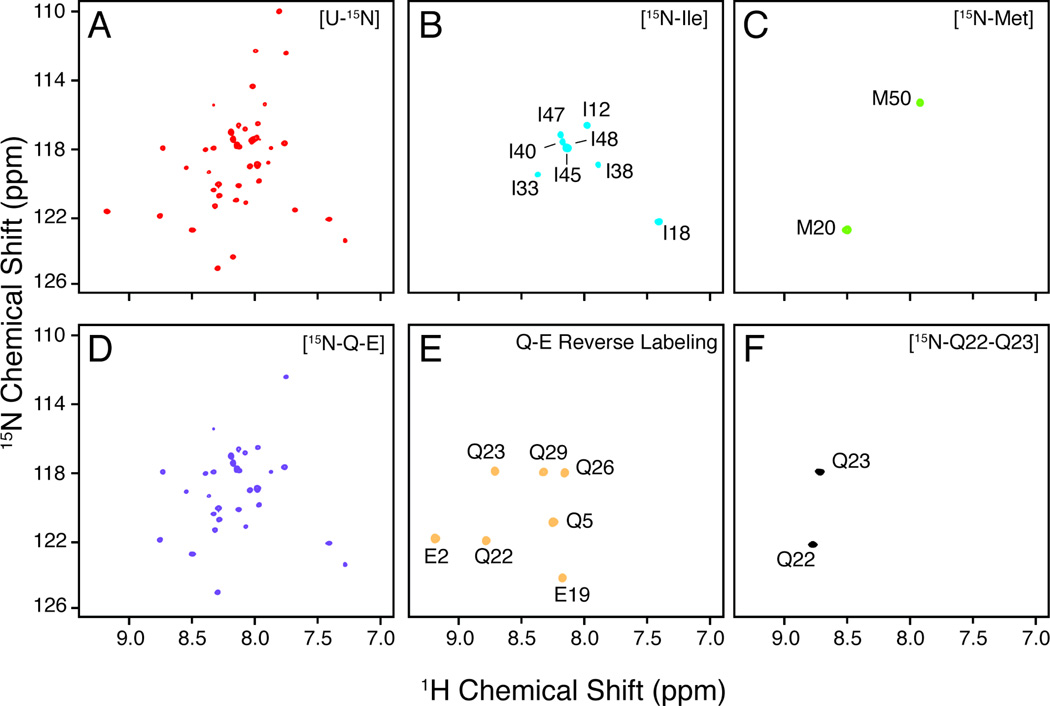

Examples of 15N uniform and selective labeling of the membrane protein PLN. A) 15N-1H HSQC of [U-15N] recombinant PLN in 300 mM DPC. B–C) Selective 15N-Ile and 15N Met labeled recombinant PLN. Notice the absence of isotopic scrambling. D) An attempt to label PLN at Gln and Glu residues using 15N-Gln and 15N-Glu labeled amino acids in the growth medium resulted in significant isotopic scrambling. E) Labeling of Glu and Gln in PLN using the reverse labeling approach. No isotopic scrambling is present. F) PLN selective labeled at Q22–Q23 produced by peptide synthesis.

Figure 4.

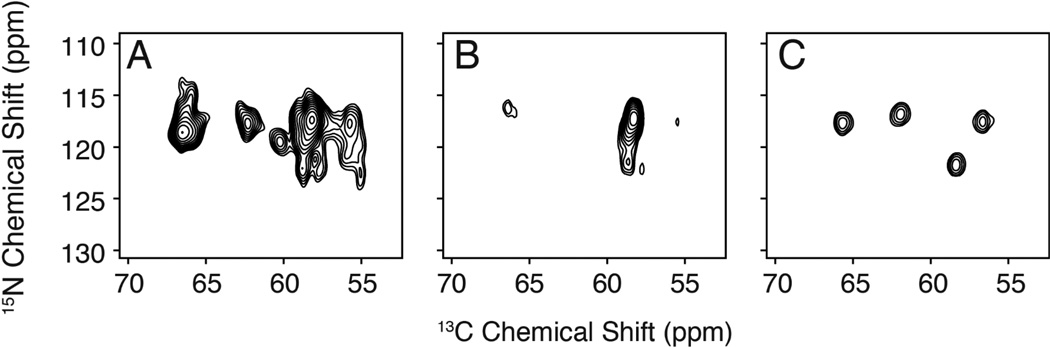

MAS N-CA 2D correlation spectra of PLN in lipid vesicles. A) uniformly labeled, [U-13C,15N] PLN. B) Selective Leu and Val labeled PLN obtained by addition of [Ile-13C,15N] to the growth medium. Notice the severe overlap in both dimensions. C) PLN labeled with 13C,15N at residues Asn30-Leu31-Phe32-Ile33 produced by peptide synthesis.

3.3 Cell-free expression systems

Cell-free systems are in-vitro transcription/translation systems extracted from a variety of cells (bacteria, wheat germ, insect cells etc) [34–36]. For cell-free systems to work, a mixture of all the 20 amino acids must be added in the reaction vessel. Because of the absence of other enzymes other than those necessary for transcription and translation, isotopic scrambling is nearly eliminated for most amino acids. In addition, this approach provides an alternative avenue to obtain IMPs that may be toxic to host cells during overexpression.

Cell-free systems can be used not only to produce residue-type selectively labeled proteins, but also for some ingenious applications such as combinatorial labeling [37–40] and stereo array isotopic labeling (SAIL) [41].

3.4 Membrane Protein purification

So far, we reviewed biological and chemical systems to introduce isotopes in different positions of a protein. However, once the protein has been recombinantly expressed or chemically synthesized it must be purified to high levels (generally more than 90% purity) before NMR experiments can be undertaken. For solid-phase peptide synthesis, purification involves cleavage of the peptide from the resin and subsequent precipitation of the peptide in organic solvents. A final step of reverse-phase chromatography usually yields pure protein suitable for structural studies.

For heterologous expression of IMPs, the purification process is more involved and it usually requires the use of fusion tags [42, 43].

A fusion tag is a protein or short peptide included in the same reading frame as the gene of the target protein. When the gene is transcribed and translated, the final protein will be fused to the tag through a peptide bond. Fusion tags are engineered either at C-terminus or N-terminus and are usually separated from the protein of interest by a flexible loop.

Two important classes of fusion tags in this context are: 1) solubility tags and 2) affinity tags. To the first category belong all those tags that are used to improve solubility of the target protein. The most widely used solubility tags are: maltose binding protein (MBP), glutathione S-transferase (GST), N-utilization substance A (NusA), and Thioredoxin [43, 44].

Affinity tags are used to aid the purification of the target protein. The most common affinity tags for IMPs are: hexahistidine, GST, biotin acceptor peptide, MISTIC (acronym for membrane-integrating sequence for translation of IM protein constructs), and streptavidin binding peptide. Affinity tags bind strongly to solid supports (usually resins or gels) together with their fusion partners. The bound fusion protein can be subsequently eluted off the resin and the affinity tag removed by chemical or proteolytic cleavage [44].

Removal of the fusion tag by proteases requires the presence of specific recognition sequences that must be engineered in the gene. Tobacco etch virus (TEV) protease, factor Xa, thrombin, and enterokinase are the most commonly used enzymes to cleave off fusion tags from the target protein [45–47]. Factor Xa has a four amino acid recognition sequence (IEGR), while TEV has a more stringent seven amino acid recognition sequence (ENLYFQ/G). TEV, however, leaves one amino acid at the C-terminus side of the cleavage site that in most cases can be constructed to coincide with a native N-terminal residue in the protein sequence [48].

Some fusion tags such as MBP and GST act as both solubility and affinity tags. The MBP system is one of the most versatile systems for the expression and purification of IMPs.

In the commercially available pMal plasmid, the gene of interest is inserted upstream of the MBP gene. A recognition sequence for TEV or Factor Xa proteases can also be engineered between the two fusion partners. The plasmid is transformed into E.coli BL21(DE3) competent cells and the protein is expressed under the control of the inducible Ptac promoter. Upon expression, the cells are lysed and loaded onto an amylose resin [49], which binds MBP at high affinity. After washing the resin with buffer, the fusion protein is eluted off the resin by addition of maltose, which competes with amylose to bind MBP. Purified fusion protein is cleaved using TEV protease. After cleavage, the reaction can be separated by reverse-phase HPLC or gel filtration to the desired purity. Alternatively, solvent extraction has been successfully used in some cases [50].

4. LABELING STRATEGIES IN SOLUTION STATE NMR

4.1 Uniform isotopic labeling

Uniform isotopic labeling consists of replacing all nuclei of a certain element with its respective isotope. As of today, the only cost-effective way to produce uniformly labeled proteins is to make use of recombinant expression in heterologous systems (see previous section). The isotope of interest is incorporated into the polypeptide by providing the organism with labeled substrates, which are then converted to labeled amino acids in the metabolic pathways [51, 52]

In the 1980s and 1990s, the development of multidimensional NMR techniques for structure and dynamics studies required proteins to be uniformly enriched in 15N and/or 13C. In general, 15N and 13C are easily introduced in the polypeptide by growing cells in minimum media containing 15N ammonium salts and 13C glucose as the sole nitrogen and carbon sources, respectively [51]. New media containing algal lysate have been recently used to produce uniformly labeled protein in bacteria, achieving higher yields at lower costs [53, 54]. 15N uniform labeling has become a standard strategy to enable NMR studies. Figure 2A shows an example of a well-dispersed and homogenous correlation spectrum for a uniformly 15N labeled membrane protein.

For large IMPs, the strong 1H-1H dipolar and heteronuclear (1H-13C or 1H-15N) relaxation pathways introduced with uniform 13C and 15N labeling becomes a source of sensitivity loss. To circumvent this problem, partial and complete deuteration of proteins has been introduced [55–57]. Deuterium is a quadrupolar nucleus with a significantly lower gyromagnetic ratio compared to a proton, therefore the previous relaxation pathways are largely eliminated [56]. Triple labeled proteins (U-2H-13C-15N) are now routinely produced and used for resonance assignment purposes [57]. However, complete deuteration has some inconveniences. First, the absence of 1H sites does not allow the detection of the structurally important 1H-1H NOE connectivities. Second, most pulse sequences end with detection of the proton resonances to increase sensitivity; therefore they would be useless with a completely deuterated protein. Fortunately, amide deuterons are readily exchanged with water protons and for most soluble proteins 1H amide exchange is achieved during the purification steps. However, for IMPs the back exchange of amides might be more difficult due to the reduced accessibility and strong hydrogen bonding of the hydrophobic domains buried in the interior of the detergent micelle [58, 59]. In such cases, the protein must be unfolded and refolded in the presence of protonated buffers, which may generate misfolded proteins [60]. For the detection of short-range NOE contacts in large proteins, deuteration can still be useful if it is carried out at lower levels (60–70 %). It has been demonstrated that partial deuteration can improve resolution and sensitivity, while enabling the detection of NOE contacts with the remaining protons [56].

As for the other isotopes, uniform deuteration is accomplished by growing cells in media containing only deuterated water as solvent and deuterated carbon sources [1]. Historically, the first isotopic labeling strategy used in protein NMR was selective deuteration in order to simplify the spectra (by dilution of the natural abundance 1H signals) and decrease the linewidths (by removing the broadening effect of dipolar spin relaxation) [2, 4]. Proteins were enriched in 2H by growing cells in minimum media containing deuterated carbon sources (2H-amino acid mixtures derived from algae grown in deuterated water or 2H glucose) and deuterated water [2, 4]. Crespi and coworkers demonstrated how completely deuterated organisms were still able to survive and reproduce, although plant and mammalian cells could only be enriched at 20–60 % with 2H [61]. However, extensive deuteration can alter the structure and activity of proteins [62, 63]. Although uniform isotopic labeling still represents the first step for most protein NMR studies, this strategy does not provide the same gain for very large helical IMPs. The main obstacle when using uniform isotopic labeling of IMPs is spectral overlap, which is caused by different factors: 1) increase in the rotational correlation times, which causes line broadening, 2) degenerate chemical shifts due to the presence of only a small number of residue types (mostly Ile, Leu, Val) in transmembrane regions and 3) high occurrence of α-helical secondary structures, which decrease the breadth of chemical shifts. These problems can be alleviated by using selective isotopic labeling schemes.

4.2 Selective isotopic labeling

For the selective labeling scheme, we indicate any labeling strategy that results in the incorporation of isotopes at specific sites along the polypeptide sequence. This results in NMR spectra of particular residue types in a protein sequence. An alternative approach, introduced by Oschkinat and co-workers [64],involves spectroscopic identification of individual or groups of residue types such as Gly, Ala, Thr, Val, Ile, Asn, and Gln. This approach is based on the clever use of INEPT transfer steps. However, the easiest and most widespread approach is the isotopic labeling of specific residue types using 15N (and more recently 13C) labeled amino acids. Traditionally, the 15N and/or 13C labeled amino acids are included in the growth media along with all the other “unlabeled” (14N/12C) amino acids. Residue-type selective labeling is extensively used to simplify spectra for assignment purposes. Not all 20 amino acids can be labeled using this strategy. In fact, the use of some amino acids results in isotopic dilution or scrambling [65]. Scrambling occurs for those amino acids that serve as precursors for the synthesis of other amino acids and results in isotopic dilution and/or distribution of the labels among the other amino acids. A classic example is the amino acid glutamate, which is a central precursor for most of the other residues [66]. If 15N-glutamate is used in the growth medium, the protein synthesized will have most of the other residues labeled as well. In the case of 15N-labeling in heterologous expression systems, there are two ways to overcome this problem: 1) use of mutated strains (auxotrophs) and 2) reverse labeling approach. In the first case, libraries of E.coli bacteria strains have been engineered so that the metabolic pathways leading to the synthesis of each amino acid are altered through mutations [66–68]. For the amino acids Arg, Cys, Gln, Gly, His, Ile, Lys, Met, Pro and Thr, a single lesion is sufficient to eliminate isotopic scrambling [66]. This is because all of these amino acids (except Thr and Ile) are located at the end of metabolic pathways and are not used as precursors for other residues [52]. For the other amino acids, more than one genetic deletion is necessary [66]. An alternative approach is reverse labeling, which does not require mutant strains of E.coli. With this approach, all of the amino acids are included in the growth medium in the unlabeled (14N) form, whereas the amino acid(s) of interest is omitted. 15N-ammonium chloride is also included in the medium [69]. When cells grow, they will use the unlabeled amino acids for protein synthesis, but they will use 15N-ammonium chloride to make up the missing amino acid(s). The result will be identical to the traditional method, but isotope scrambling can be significantly reduced. Figure 2 shows the comparison between an attempt to label Glu and Gln in a membrane protein using the traditional selective labeling method, resulting in severe isotopic scrambling, (Figure 2D) and the reverse labeling method (Figure 2E).

The use of cell-free expression systems has also been applied to a number of membrane proteins, alleviating the scrambling encountered in protein expression within bacterial host cells. In this manner, high resolution spectra of membrane proteins have been obtained from in vitro protein synthesis [36, 70]. A number of labeling strategies, including combinatorial, sequence-optimized, or SAIL approaches, have been used in cell-free protein synthesis to aid in resonance assignment and improve the spectral quality of membrane proteins [71–73]. These approaches are different variations of selective-labeling of amino acids into a target protein sequence during cell-free protein expression. However, since in vitro expression is not complicated by various catabolic and metabolic pathways, unique protein labeling patterns can be obtained.

Another promising approach for studying large proteins is to incorporate isotopically labeled unnatural amino acids such as p-methoxy-phenylalanine (p-OMePhe), o-nitrobenzyl-tyrosine (oNBTyr), 2-amino-3-(4-(trifluoromethoxy)phenyl)propanoic acid (OCF3Phe), trifluoromethyl-l-phenylalanine [74–76] into specific single positions along the primary sequence of a protein. This is possible by using orthogonal tRNA/tRNA synthetase pairs, which generates tRNA charged with the unnatural amino acid [75, 77, 78]. The validity of this approach was demonstrated by incorporating three unnatural amino acid in the 33 kDa thioesterase domain of human fatty acid synthase without perturbation of the protein structure [74].

Fluorine can also be selectively introduced in proteins by using fluorinated tryptophan, tyrosine or phenylalanine amino acids in E.coli strains auxotrophic for those amino acids [79]. Fluorine labeled amino acids have been used extensively to study protein folding, ligand binding, dynamics [79, 80], membrane immersion depth [81] and more recently solvent accessibility [82].

Finally, a new method for the labeling of specific domains of proteins has been proposed with the name “segmental labeling”. This method exploits the post-translational modification, known as splicing, performed by inteins [78]. For a detailed description of this technique see previous reviews [83]. The main point of this approach is that it is possible to label (with 15N and/or 13C) only specific domains, while the rest of the protein remains unlabeled. This has important consequences in NMR, since the spectra are considerably simplified while retaining important inter-residue information for the labeled domain. Although useful, this technique has not been extensively applied for the preparation of IMPs.

4.3 Methyl labeling

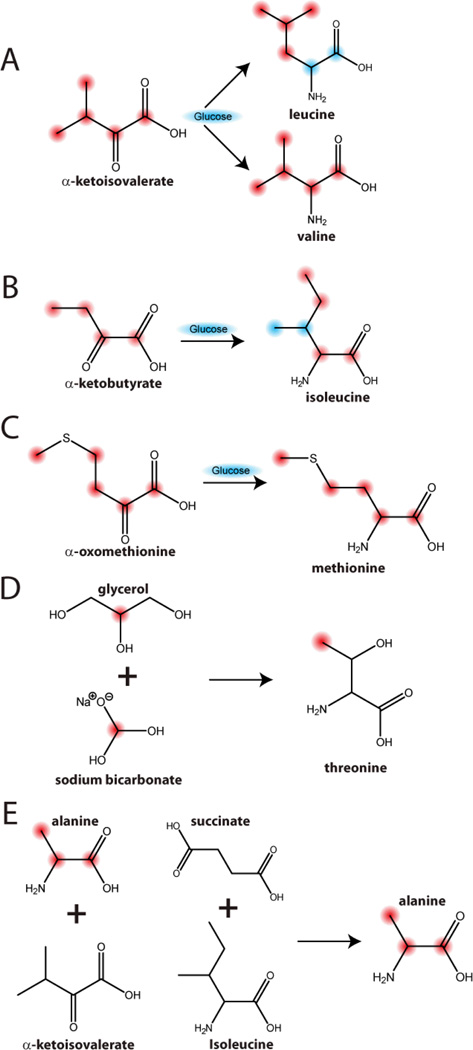

In highly deuterated proteins, it is advantageous to reintroduce some of the protons at specific positions [84]. For the methyl groups of isoleucine, leucine and valine, this is achieved by adding protonated precursors to the deuterated growth medium just before induction [84]. The most common of these precursors are α-ketobutyrate (yielding isoleucine) and α-ketoisovalerate (yielding leucine and valine) (Figure 3A–B). Due to the high degree of sensitivity via TROSY NMR detection of deuterated, methyl labeled proteins, a number of commercially available precursors with specific labeling patterns have been developed. For the methyl labeling of methionine, alpha-oxomethionine is added as precursor in the presence of glucose (Figure 3C), whereas labeling of the methyl group of threonine can be achieved by growing cells in a medium containing a mixture of 2-13C-glycerol and NaH13CO3 [7] (Figure 3D). Slightly more involving is the 13C labeling of alanine, which requires the addition of 13C-labeled alanine supplemented with unlabeled succinate, α-ketoisovalerate and isoleucine to reduce isotopic scrambling (Figure 3E)[7].

Figure 3.

Selective 13C enrichment of methyl containing amino acids using different precursors in the presence of glucose. Carbons derived from the precursors are indicated in red. Note that these precursors lead to very high 13C incorporation for all sites (>90%). We did not include other carbon sources (such as 13C-pyruvate) that lead to lower enrichment levels at the methyl

Methyl group labeling has proven to be a very useful strategy for membrane proteins since hydrophobic amino acids Ile, Leu and Val occur at high frequency in transmembrane domains and they are often involved in the packing of those domains [85–87]. Selective methyl labeling has been successfully applied for the study of several IMPs by solution NMR in past few years [88–92].

5. LABELING STRATEGIES IN SOLID STATE NMR

Unlike in solution NMR where rapid reorientation leads to isotropic chemical shifts and averaging of dipolar interactions, SSNMR spectra are dominated by anisotropic interactions such as anisotropic chemical shifts, quadrupolar, and dipolar couplings. The two primary classes of SSNMR methodology are the oriented (static) and magic angle spinning (MAS) experiments. MAS experiments most commonly result in solution-like isotropic spectra, whereas oriented solid-state NMR (O-SSNMR) gives orientation dependent parameters, which can be used to determine the orientation of membrane proteins in lipid bilayers or single/liquid crystals such as bicelles. Highly anisotropic systems for MAS or O-SSNMR have primarily utilized detection on 15N or 13C, since 1H observation is hindered due to strong 1H-1H dipolar couplings that give rise to severe line-broadening. Techniques such as fast MAS (> 60 kHz) in combination with 2H labeling have made proton detection feasible in biological samples [93]. In addition, stroboscopic detection allows for the detection of signals while simultaneously decoupling them in a windowed-fashion [94]. Both windowed PMLG in MAS and PISEMO in O-SSNMR have benefited from these approaches. Advancements in these techniques will play an important role in the future of SSNMR due to the significant gains in sensitivity.

The following section will be broken down into labeling approaches in (1) O-SSNMR and (2) MAS NMR. Subcategories of isotopic labeling strategies will be discussed that (a) reduce spectral complexity and (b) decrease the linewidth of the resonances. These two approaches are often used synergistically for optimal spectral quality.

5.1 Labeling strategies in magic-angle-spinning (MAS)

5.1.1 Uniform Isotopic Labeling

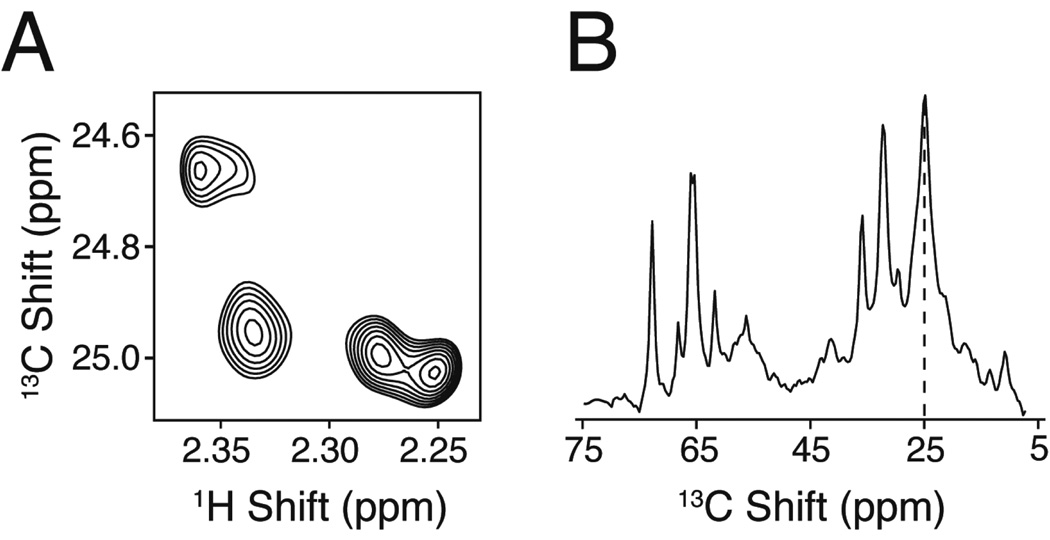

While SSNMR lines of the best-behaving samples can approach the quality of solution NMR spectra, the majority of proteins give substantially broader spectra. As an example, consider the following typical backbone 15N and 13C linewidths of the 6 kDa transmembrane protein phospholamban monomer (PLN) at a magnetic field of 14.1 T (600 MHz 1H frequency): (a) solution NMR in detergent micelles ~0.25–0.35 ppm, (b) MAS-SSNMR in lipids ~0.75–1.5 ppm, (c) O-SSNMR in lipid bicelles ~3–6 ppm, and (d) O-SSNMR in mechanically aligned lipid bilayers ~5–10 ppm. As expected from these linewidths, the ability to resolve peaks is substantially reduced in the case of MAS and O-SSNMR. An MAS N-CA 2D correlation spectrum of uniformly labeled 13C, 15N spectra, [U-13C,15N] PLN is shown in Figure 3A. From the known labeling in the sample, 52 peaks are expected. One alternative is to use 3D experiments to improve the resolution by carrying out experiments such as N-CA-C’, N-C’-CX, CA-N-C’, and other sequential experiments in SSNMR. However, for redundant primary sequences and helical structures such as membrane proteins, 3D experiments alone are not sufficient to resolve all the peaks. The 15N dimension typically has only ~5–10 ppm in resolution (not including glycine residues). In addition, the sensitivity of multiple magnetization transfers considerably attenuates signal-to-noise, further complicating the scenario. For these reasons, reduction of spectral complexity is needed for unambiguous assignment purposes.

Similar to solution state NMR, deuteration of protein MAS samples eliminates the dipolar interactions involving protons, thus reducing the linewidths of the detected nuclei [95]. A portion of the dipolar network can be reintroduced by back-exchanging the amide protons, while the magnetization transfer to the non-exchangeable side chains for PDSD or DARR (Takegoshi K. 2001 Chem Phys Lett 344:631) is achieved by expressing the proteins in the media containing minor amounts of protonated substrates (Reif B. 2001 J Magn Reson 151:320) [96, 97]. Since the majority of MAS pulse sequences have cross polarization as an essential block for boosting the sensitivity of low γ nuclei, deuterated samples require either direct polarization of heteronuclei (long T1 values and therefore costly from the experimental time standpoint), but can be shortened by paramagnetic doping [98]. Protein deuteration has also been observed to be beneficial in dynamic nuclear polarization experiments, yielding higher sensitivity relative to the protonated samples [99]. Furthermore, aside from providing line-narrowing of heteronuclear lineshapes (vide supra), deuterium itself can be employed for the assignment purposes. Utility of 2H in triple uniformly labeled proteins has been demonstrated for the assignment of spin systems in 13C edited spectra [100]. We note that the acquisition of such experiments can be facilitated with the help of DUMAS approach [101].

5.1.2 Synthetic Labeling

The simplest strategy that yields the most unambiguous assignment is to label a single residue. In this case, the assignment problem is reduced (or eliminated), and a single broad line does not cause the same problems as when several signals are present. For 2H or 17O quadrupoles, the inherent linewidths in the spectra are on the order of ~50–100 kHz, with mosaic spread and IMP dynamics further increasing the linewidths, requiring the use of single labeled samples [102, 103]. Interpretation of quadrupolar splitting can give orientation as well as dynamics of peptides and proteins (see Section 5.2) [104]. This approach is very similar to EPR spectroscopy that also utilizes site-specific labeling, often with the methanesulfonothioate (MTSL) spin-label if samples are made by single cysteine mutants, or 2,2,6,6-tetramethyl-piperidine-1-oxyl-4-amino-4-carboxy (TOAC), prepared by SPPS.

An extension of single site-specific labeling strategy is the incorporation of two nuclear probes in which distance and dynamics information can be obtained. This is the foundation for a number of rotational-echo double-resonance (REDOR) experiments which have been used extensively in the SSNMR studies of peptides and proteins [105–109]

A further step is to selectively label stretches of residues in the primary sequence in a contiguous fashion. Such an approach has been successfully implemented by a number of MAS research groups for studying fibrils. For example, Jaroniec et al. [110] relied on three samples to assign the chemical shifts from a fragment of transthyretin (residues 105–115) fibrils. In each case the spectra are substantially simplified, since one can avoid overlap from unlike amino acids by carefully choosing the stretches of amino acids to label. Also due to the limited labeling, 2D spectra are usually sufficient to assign the spectra, without the need for longer 3D acquisitions that can take several weeks to acquire. Many other research groups have used this strategy in the amyloid fibrils, where broad lines similar to membrane proteins are present [111, 112]. We recently implemented this strategy for membrane proteins to understand the complicated folding pathways of amphipathic helices at the membrane interface [113]. Figure 4C shows an example of the simplification that is expected when solid-phase peptide synthesis is used to introduce a limited number of labeled residues. The main disadvantages of this technique are (a) limited applicability for large proteins (>50–75 residues in length), (b) high costs associated with purchasing some of the isotopically labeled and protected amino acids, and (c) difficulty in measuring long-range distances, since only a limited number of labeled sites are present. Nevertheless, if the protein of interest can be synthesized using standard solid-phase chemistry, spectral quality and the ability to unambiguously assign peaks is improved.

5.1.3 Residue-type Labeling

Another way to reduce spectral complexity and overlap is to incorporate isotopically labeled amino acids into the growth media. Unfortunately for IMPs this does not reduce a primary problem in the [U-15N,13C] spectra: overlap of peaks of the same residue-type (Figure 4B). However, when multiple [U-13C,15N] amino acids are labeled at the same time, pairwise-selective labeling can be obtained. For example, consider the stretch of six residues Val1-Ala2-Ile3-Ile4-Asn5-Ala6. If all the residues were labeled [U-13C,15N], there would be five 13C’-15N peptide bonds. Alternatively, residue-type selective labeling with [13C,15N]-Ile and [13C,15N]-Ala would give only two 13C’-15N pairwise peptide bonds (Ala2-Ile3 and Ile3-Ile4). A 2D N-CO MAS correlation experiment would give five cross-peaks for the [U-13C,15N] labeling pattern and only two for the selective labeling, thus improving unambiguous assignment.

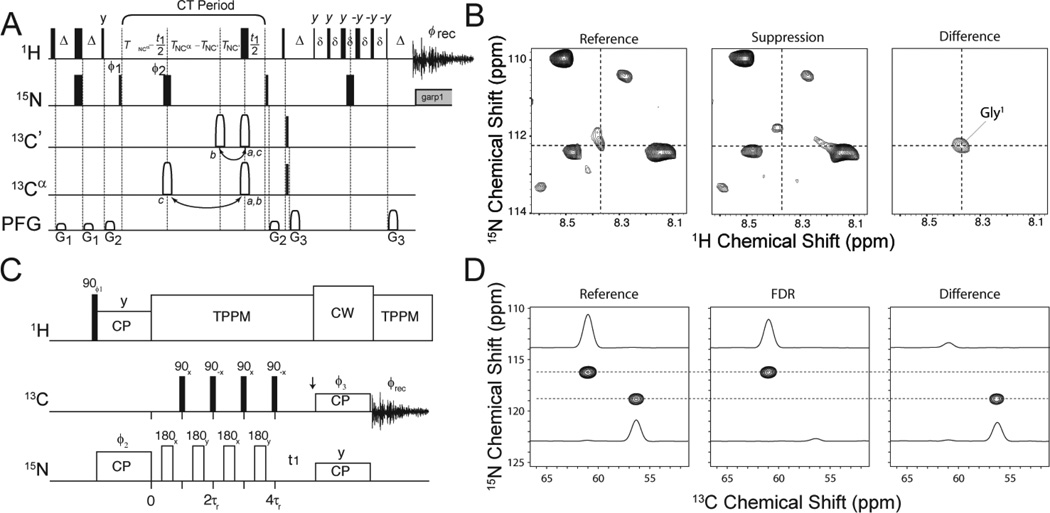

Sensitivity of the experiment in connection with the labeling pattern can be improved with new pulse sequences. We recently implemented a complementary approach to the standard backbone experiments that increases the sensitivity of 2D correlation spectra by ~25–40%. Our filtering approach is similar to the spin-echo difference technique developed by Bax and co-workers for solution NMR [114]. This pulse sequence with a schematic and the results are shown in Figure 6. Broadly, we classify this approach as selective labeling with filtering blocks in pulse sequences to reduce the amount of peaks in the spectrum. This approach incorporates frequency selective REDOR with the N-CA selective CP of Baldus et al. [115]. Recently, this approach has been extended to acquire multiple heteronuclear correlation datasets at the same time using afterglow magnetization from the cross-polarization experiment [116].

Figure 6.

A–B) CCLS-HSQC. A) Schematic of the CCLS-HSQC pulse sequence. The reference spectrum is obtained by executing the pulse sequence with the 180° 13C′ pulse (open rectangle) at position a; the 13C′ suppressed spectrum is obtained with this pulse at position b. B) Examples of…. C–D) Frequency-selective heteronuclear dephasing and selective carbonyl labeling to deconvolute crowded spectra of membrane proteins by magic angle spinning NMR. C) Pulse sequence used to obtain 2D FDR-15N–13Cα. D) FDR-15N–13Cα spectra for N-acetyl-valyl-leucine. Spectra were acquired with (FDR – red spectrum) and without 13C 90° pulses (reference – black spectrum) (Reproduced with permission from Traaseth and Veglia [195].

Residue-type labeling can also be employed in MAS SSNMR with selective amino acids that are not prone to scrambling. For instance, this approach has been utilized with 4-19F-phenylalanine and 4-13C-tyrosine to probe distances in the α2β2 tetrameric enzyme tryptophan synthase using REDOR spectroscopy [117]. However, an extension of residue-type labeling is achieved using reverse labeling or unlabeling. These approaches utilize U-13C glucose in the growth medium with isotopically unlabeled amino acids to produce a labeling pattern that labels those amino acids that were not supplied in the growth medium [118, 119]. This can be very advantageous, since several of these amino acids can be quite expensive to purchase, especially since they would often times scramble in the growth as previously mentioned above.

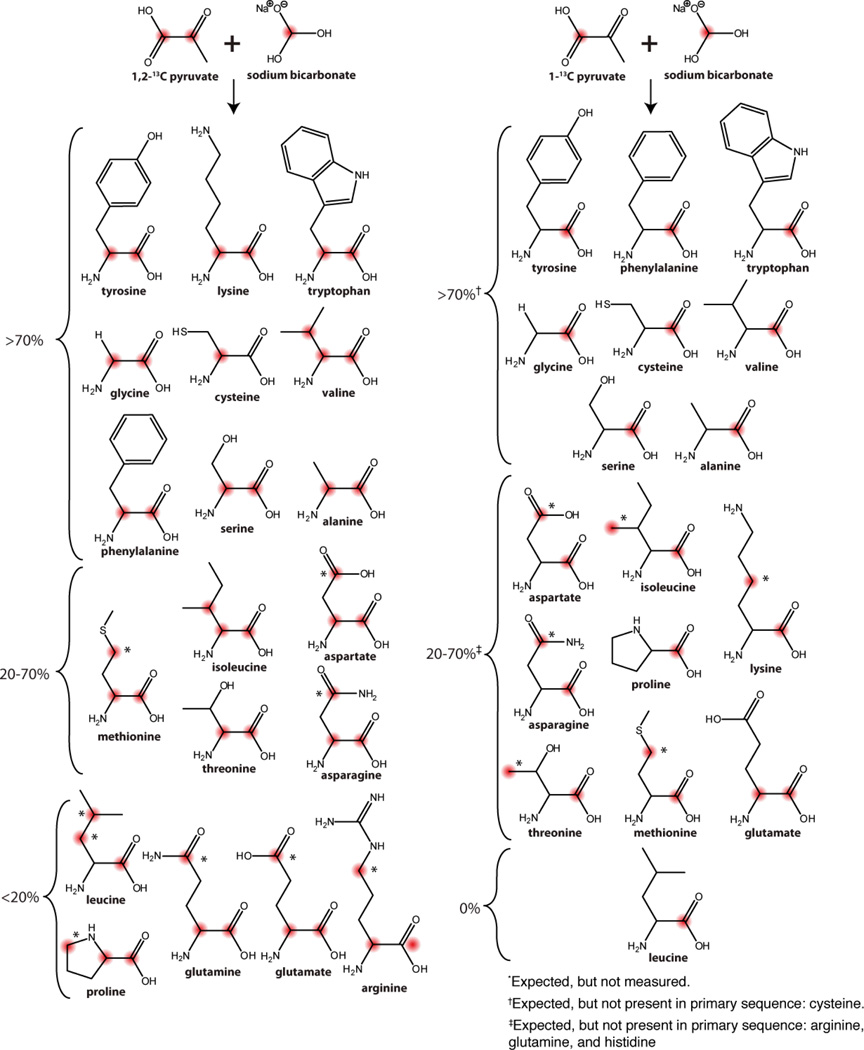

5.1.4 Metabolic Labeling with Precursors in MAS NMR

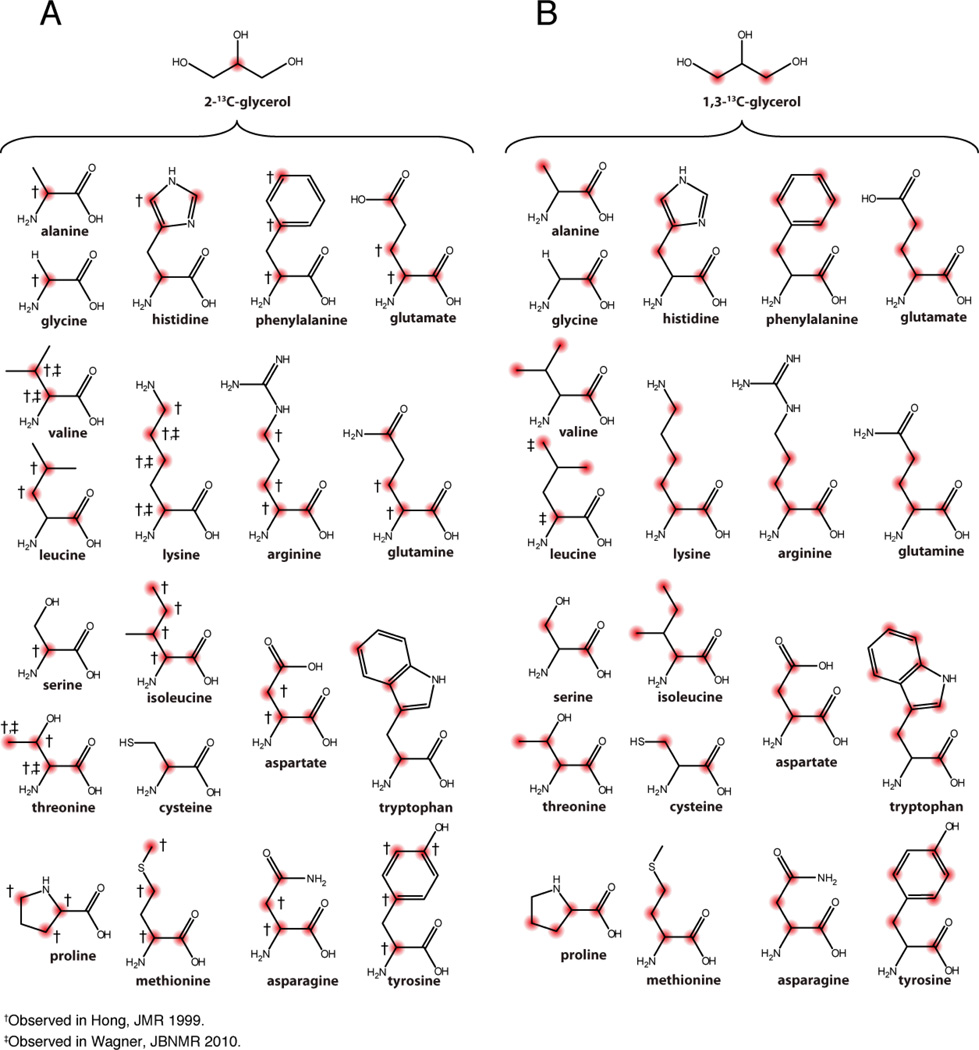

An emerging approach for diluting the spin system in MAS SSNMR is the use of metabolic precursors. This method is beneficial when 13C is the nucleus for direct observation. Since the presence of J-couplings (35–60 Hz)can cause line broadening, removing one-bond J-couplings can substantially improve 13C spectra resolution [120]. For broader resonances > 1 ppm, only minor improvement is expected. The most common ways of diluting the 13C spins is by fractional labeling or use of specifically labeled precursors: glycerol (1,3-13C-glycerol and 2-13C-glycerol) (Figure 4), glucose (1-13C-glucose and 2-13C-glucose) (Figure 5), or pyruvate with bicarbonate labeling (Figure 9). Note that there are many other precursors that can be used such as keto-acids (Figure 3), but these labeling patterns are less common or primarily target methyl group spectroscopy. In the following section, we will focus on obtaining the backbone labels, since these are the foremost challenge to assign crowded SSNMR spectra.

Figure 5.

Expected 13C distribution using 2-13C-glycerol or 1,3-13C-glycerol as the sole carbon source and E.coli BL21(DE3) strain. 13C labeled carbons are indicated in red. Two studies [193, 194] reported different results using 2-13C-glycerol therefore both are indicated in the labeling pattern for each amino acid.

Figure 9.

Expected 13C distribution using pyruvate and sodium bicarbonate as the sole carbon sources in E.coli BL21(DE3). A) 1,2-13C-pyruvate and NaH13CO3 and B) 1-13C-pyruvate and NaH13CO3

The original approach to dilute the spin system was simply to fractionally label the protein by using a mixture of unlabeled and labeled carbon source [121]. With this approach, the labels are distributed in a stochastic manner. A significant disadvantage is the lack of pairwise labeling to assign the simplified spectra. To overcome these problems, Hong and Jakes introduced the TEASE approach (ten-amino acid selective and extensive labeling), which utilizes 2-13C-glycerol and 15NH4Cl isotopic sources and ten unlabeled amino acids (Asp, Asn, Arg, Gln, Glu, Ile, Lys, Met, Pro and Thr) [122]. This labeling scheme results in 100% 13C’ for Gly, Ala, Ser, Cys, Phe, Tyr, Trp, His, Val and 100% incorporation at 13Cα for Leu. To avoid or limit the fractional 13C or 15N labeling of these ten amino acids, they are added at natural abundance. Due to the use of unlabeled amino acids such as glutamine and glutamate, a two-fold dilution of 15N is obtained by this method. Likewise, the 1,3-13C-glycerol, gives 100% incorporation for nine amino acids (Gly, Ala, Ser, Cys, Phe, Tyr, Trp, His, Val) at the 13Cα site. If unlabeled amino acids are not provided as in the TEASE approach, the other ten amino acids are fractionally labeled [123]. In addition to direct J-coupling removal, diluting the 13C spins can also reduce cross-relaxation between 13C nuclei leading to both increased resolution and sensitivity [124]. While 1,3-13C-glycerol and 2-13C-glycerol labeling patterns are not ideal for backbone walk due to non-contiguous 13C labels, improved 13C-13C correlations in spin diffusion experiments have been observed due to the reduction in dipolar truncation effects. Additionally, the 1,3-13C-glycerol labeling scheme is useful to reduce spectral overlap in N-CO correlation spectra (Hiller M. et al. Application note 22, Cambridge Isotope Laboratory, Inc.).

To obtain isolated 13C spins (i.e., non-bonded 13C-13C pairs in the backbone or side chain carbon atoms), it is possible to use 2-13C-glucose (Figure 5B). This method generates 20–45% enrichment at the 13Cα position, with virtually no labeling at the 13C’ for all residues with the exception of Leu, which is labeled at the 13C’ position. In addition, all residues are devoid of 13Cβ labeling with the exception of Leu, Val, and Ile residues. It is also possible to use 1-13C-glucose (Figure 5B). This labeling scheme enables the introduction of 13C at the α-position of Leu and Ile, which are very abundant in membrane protein sequences. This labeling scheme also gives stretches of 13C atoms such as 13Cα-13Cβ-13Cγ for many residues, which can be useful for side chain detection. For a detailed summary of labeled atoms in 1-13C-glucose and 2-13C-glucose, see Figure 3 in Lundstrom et al. [125]. A combination of fractional labeling with selectively labeled precursors has also been used to achieve isolated spin systems. Wand et al. [121] used 15% [1-13C-acetate], 15% [2-13C-acetate], and 70% [1,2-12C-acetate] to achieve isolated 13C spins for relaxation experiments on ubiquitin.

5.2. Labeling Strategies for Oriented Solid-State NMR (O-SSNMR) Studies

While MAS has been used to study membrane proteins, fibrils, amorphous proteins, and crystalline proteins, O-SSNMR has been primarily used to study membrane protein structure and orientation [126–128]. Complete membrane protein structure determination requires characterization of the orientation of the membrane protein with respect to the lipid bilayer, i.e. topology. Since the energetic penalty for distorting the hydrogen bonding network is high in the lipid bilayer environment with low dielectric permeability [129], the O-SSNMR data has been often successfully interpreted assuming an idealized α-helical environment. Alternatively, O-SSNMR data can be incorporated in a total potential for structure minimization, restraining both protein topology and geometry [130–133]. Furthermore, the analysis of OSS NMR data from multiple isotopes can yield whole body dynamics of the transmembrane segments as well [134]. The O-SSNMR signal is dependent upon the angle θ between the interaction tensor components and the applied magnetic field according to the second order Legendre polynomial, . The essential requirement for interpreting the θ angle in scope of the transmembrane domain orientation is that the NMR-active label must be rigidly attached to the polypeptide backbone. Below we discuss three different approaches in O-SSNMR, based on 15N, 2H and 19F labeling.

5.2.1. Nitrogen labeling in OSS NMR

The most common way to determine the topology of the membrane protein is through separated local field experiments (SLF) such as PISEMA [135]. The PISEMA spectrum is considered the fingerprint for oriented membrane proteins, and is the most popular of the SLF class. The PISEMA experiment measures the anisotropic chemical shift of spin S and correlates it to the corresponding I-S dipolar coupling. Typically, the S spin is 15N (although applicability of 13C PISEMA has been illustrated [136] and the dipolar coupling is 1H-15N, and correspondingly membrane proteins are either uniformly or selectively labeled with 15N.

The PISEMA spectra result in periodic spectral patterns called PISA wheels [137–139]. From these wheels, it is possible to immediately obtain the tilt angles of helices or sheets with respect to the lipid bilayer normal, while determination of the rotation angle requires the assignment of the PISEMA spectrum.

As an initial step, the macroscopic alignment of the protein is verified by acquiring a PISEMA spectrum using a U-15N labeled protein. Often, small adjustments to the lipid composition, buffer, and temperature are necessary to find the best (homogenous) alignment.. Once conditions are optimal, a high quality U-15N PISEMA can be obtained that can be fit to obtain the global angle of orientation of the helices [137, 138]. One significant challenge that arises is how to assign a labeled PISEMA spectrum. There are several ways this can be done, the most used being: (1) spin diffusion experiments with a single [U-15N] sample [140, 141]; (2) assignment of isotropic 1H and 15N chemical shifts from solution NMR or MAS SSNMR in conjunction with a pair of flipped and unflipped aligned bicelle SLF spectra, requiring selective labeling [142]; (3) use of periodic assignment algorithms (based on PISA wheel) with uniform and/or selective labeled samples (“shotgun” approach) [143, 144].

Since chemical shifts are anisotropic in O-SSNMR, the orientation of the internuclear NH vector with respect to the magnetic field rather than residue-type or secondary structure determines the resonance position. This significantly helps to resolve spectral overlap in highly degenerate transmembrane helical segments. Nevertheless, uniformly labeled samples can still present severe spectral overlap and are often difficult to assign and selective labeling represents a reliable source for completing the assignments. Fortunately, the majority of the transmembrane helices are enriched with amino acids with aliphatic side chains, which are not prone to isotopic scrambling. By labeling a protein sample with U-15N-Leu or U-15N-Ile, one can substantially decrease the complexity of the spectra. One can also use residue-specific labeling to determine accessibility as in H/D accessibility or proximity to a spin-label as is commonly done in solution NMR for membrane proteins [145].

Pairwise labeling utilized in solution NMR has not been extensively utilized in O-SSNMR. This labeling scheme will be useful to resolve backbone resonances, when triple-resonance experiments will become routine for membrane proteins aligned in bicelles or mechanically aligned bilayers. In addition, isotopic dilution will reduce strong dipolar couplings and enable to acquisition of high quality spectra.

5.2.2. Deuterium labeling in OSS NMR

While the SLF experiments provide an initial picture of the IMP topology in lipid bilayers, they suffer from an intrinsically low sensitivity due to the orientation of the internuclear 15N-H bond vectors, and in many cases where more precision is required it is often advantageous to employ isotopic labels which axes of interactions are positioned close to the magic angle relative to the helix axis. The combination of Φ-Ψ dihedral angles in a regular α-helix along with the tetrahedral geometry of the Cα carbon dictates that the Cα-Cβ and Cα-Hα bond vectors form angles close to the magic angle with the helix axis, thus providing the maximum sensitivity for the interactions which are directed along these bonds. Alanine with a deuterated methyl group is therefore a natural choice for determining the topology of IMPs. Initial proof of concept has been carried out by labeling only a few residues at a time [146, 147] and the first systematic study was performed utilizing model Ala-rich peptides in a variety of lipid bilayers [148]. Since then deuterium NMR of methyl groups has been extensively applied for the investigation of antimicrobial peptides [149], IMPs [150], numerous model systems [151] and peptaibols [152].

Since deuterium NMR is recorded in a one-dimensional fashion typically employing a quadrupolar echo experiment [153] or quadrupolar CPMG [154], the spectral resolution precludes labeling of multiple sites, typically limiting the IMP to one or two labeled alanines. Unlike 1H-15N dipolar couplings, which retain a constant sign for transmembrane segments of IMPs, quadrupolar couplings oscillate between positive and negative values, but the sign typically cannot be determined experimentally, unless it exceeds ¾ of the quadrupolar coupling constant (i.e. >37 kHz for the methyl groups) in which case the sign must be positive. Such sign ambiguity necessitates employing multiple labels, or combining the methyl restraints with other O-SSNMR labels. Limited resolution that can be achieved in 1D experiment along with the complexity of the metabolic pathways limits deuterium NMR to the synthetic sequences.

The deuteron at an α-carbon presents an appealing supplement to the alanine methyl groups, since it is present in each of the canonical amino acids and its quadrupolar coupling undergoes major changes upon the transmembrane domain tilt or rotation. The attempts to employ 2Hα O-SSNMR had limited success so far. In multiple single-span IMPs the backbone deuteron either could not be detected, or observed with extremely low sensitivity [148, 155]. Interestingly in several cases a significant increase in 2Hα signal intensity has been observed, which potentially relates to the peptide plane and/or whole body dynamics of IMPs [156].

These examples by no means cover all the uses of deuterium in oriented solid-state NMR of IMPs (for its use in solution and MAS NMR see above). Other applications include probing the aliphatic side chain dynamics [157–159], orientation of the Trp indoles [134, 160], IMPs oligomerization [161], mobility of the lipidated IMPs [162, 163] as well as a multitude of studies of lipid bilayer membranes – IMPs hosts.

5.2.3. Fluorine labeling in OSS NMR

For detailed considerations of 19F OSS NMR the reader is referred to the excellent recent review by Ulrich and co-workers [164], while we present a brief overview below. Fluorine is a highly appealing nucleus in biological NMR. High gyromagnetic ratio, 100% natural abundance of the NMR-active 19F isotope and the lack of natural background leads to the high sensitivity [165]. Care must be taken to exclude fluorinated solvents (e.g. trifluoroacetic acid, a frequent ion pairing additive) as well as fluorinated polymers from the probe assembly. Close Larmor frequencies of fluorine and hydrogen exert stringent requirements on the NMR hardware. Since biomolecules do not contain fluorine, unnatural amino acids, usually based on Phe, Pro or Aib, need to be introduced in the sequence synthetically, although promising results have been achieved with genetic incorporation [166].

6. ISOTOPIC LABELING FOR PROTEIN-PROTEIN INTERACTION STUDIES

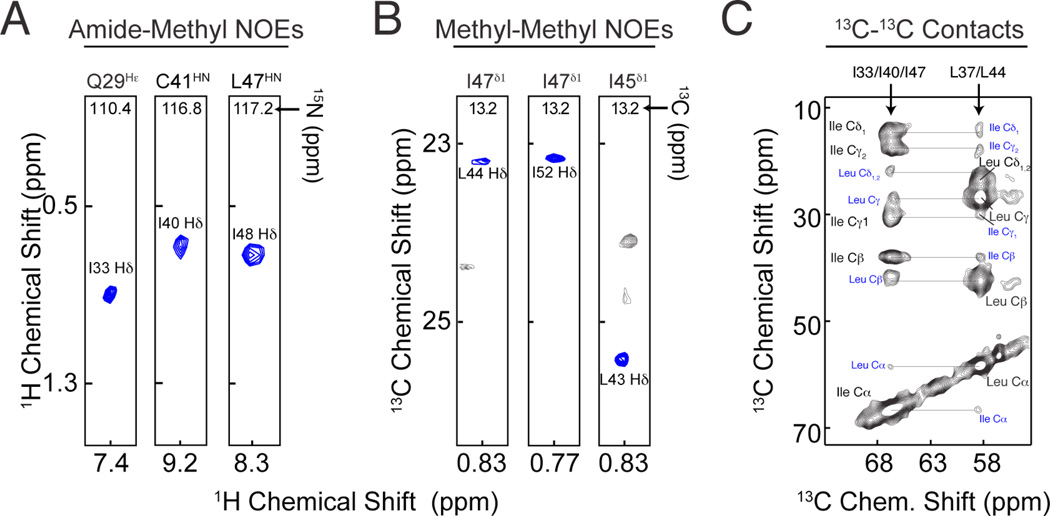

A very useful application of methyl labeling (see section 5.1.4) and uniform isotopic labeling (see section 5.1.1) is found in the study of homo-oligomeric membrane proteins by NMR. Because of the symmetry of such molecules, the NMR signals are chemically equivalent; therefore only one set of resonances is observed. In order to obtain structural information about symmetric oligomers, asymmetric labeling strategies have been developed [167–169]. The objective of these strategies is to introduce “isotopic asymmetry” in the complexes. This can be done by labeling one of the protomers with a certain isotopic scheme and the other with a different scheme. Upon formation of the complex or oligomer, the intermolecular contacts can be unambiguously assigned. Pulse sequences can be designed to detect the dipolar contacts between the protomers [90, 170, 171].

We recently proposed two asymmetric labeling schemes to measure inter-protomer contacts in the pentameric phospholamban (PLN) for solution and solid-state NMR [90, 170]. PLN is a homo-pentamer composed of five identical protomers (52 residues each). The transmembrane portion of each protomer consists of mainly hydrophobic amino acids Ile, Leu and Val, which are involved in keeping the oligomer together thorough hydrophobic interactions. The first labeling scheme was devised in order to probe inter-protomer contacts in detergent micelles by solution NMR. In this scheme, half of the protomers were labeled [U-2H, 12C, 14N] and 13CH3 at the Ileδ1 (using 2-ketobutyric acid-4-13C,3,3-d2 as precursor), whereas the other half was labeled [U-2H, 12C, 14N] and 13CH3 at the Leuδ1/2/Valγ1/ (using 2-keto-3-(methyl-d3)-butyric acid-4-13C as precursor). Using a methyl-methyl NOESY pulse sequence, it was possible to easily identify and unambiguously assign inter-protomer contacts, which were used for structure calculations (Figure 7B). This I-LV methyl labeling scheme is very powerful since Ileδ1 resonates at significantly different frequencies compared to Leuδ1/2/Valγ1/2. Therefore the presence of inter-protomer contacts is straightforward to identify and correctly assign. This scheme can easily be extended to measure inter-protomer contacts between methyls and backbone amides, where half of the protein is uniformly (or selectively) labeled with 15N at the amide groups in a deuterated background and half of the protein is methyl labeled at either Ile, or Leu/Val (Figure 7A)[90]. A similar approach was used to identify inter-protomer contacts in lipid vesicles using MAS-NMR. In this case half of the protein was selectively labeled with 13C using [13C-Ile] amino acid and the other half was labeled with 13C using [13C-Leu] amino acid. The inter-protomer contacts were detected using a dipolar assisted rotational resonance (DARR) pulse sequence (Figure 7C).

Figure 7.

Asymmetric labeling scheme for the detection of inter-protomer contacts in homo-oligomeric membrane proteins using solution and solid-state NMR. A) 2D planes from 3D [1H, 1H, 15N]-NOESY-HSQC (400 ms mixing time) on a mixed PLN sample with 1:1 ratio of [2H-15N] and [2H-14N-13CH3-Ileδ1] PLN. B) 2D planes from 3D [1H, 13C, 13C]-HSQC-NOESY-HSQC experiment performed on a sample containing 1:1 ratio [2H-14N-13CH3-Ileδ1] and [2H-14N-13CH3-Leuδ1/Valγ1] PLN. C) 2D-DARR experiments (200 ms mixing time) on a 50% [U13C]-Leu/ 50% [U13C]-Ile PLN sample. Intra-residue and interprotomer cross-peaks are labeled in black and blue, respectively (Reproduced with permission from Verardi et al. [90].

7. POST-EXPRESSION LABELING

7.1 Post-expression isotopic labeling

There are several chemical methods to modify reactive amino acid side-chain groups after protein expression and purification [172]. By using isotopically labeled reagents, it is possible to selectively enrich amino acids with molecules containing NMR active isotopes. The most common residues whose side-chains can be chemically modified for NMR studies are cysteines, tyrosine and lysines.

The sulfhydryl group (-SH) of free cysteine in a protein can easily react in mild conditions with different chemical groups. Two applications that make use of the high nucleophilicity of free thiol groups in cysteines are the introduction of fluorine atoms and site directed methyl group substitution. In the first case, the NMR active 19F is attached to cysteine by reacting the free thiol with trifluoromethyl derivatives such as: 3-bromo-1,1,1-trifluoroacetone (BTFA) [173], trifluoroethylthio group (TET) [174], S-ethyl-trifluorothioactetate (SETFA) [175] and trifluoroacetamidosuccinicanhydride (TFASAN) [176]. This labeling approach has been successfully applied to the study of several proteins such as: citrate synthase [177], G-actin [178, 179], Myosin S-1/F-actin complex [180], SH3 domain [181], rhodopsin [174] and β2-Adrenergic Receptor [182]. Recently, Kay and co-workers introduced isotopically labeled methyl groups in cysteine side chains using methyl methanethiosulfonate to form 13C-S-methylthiocysteine [183]. This labeling is very promising considering the advantages of observing methyl resonances by NMR and the fact that S-methylthiocysteine is very similar to a methionine residue, therefore it should not substantially alter the secondary structure of the protein. We have recently applied this approach to the selective methyl labeling of accessible cysteines in the 110kDa integral membrane protein SERCA (Sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ ATPase) and obtained high-resolution solid and solution state NMR spectra (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Cysteine methylation of SERCA1a by methyl methanethiosulfonate (MMTS) reaction. A) 1H–13C HSQC spectrum of 13C methylthiocysteine in 100 mM 2H dodecylphosphocholine acquired at 14.1 T field strength. B) MAS one-dimensional cross-polarization of 13C methylthiocysteine labeled SERCA1a in 2H DMPC lipid vesicles run at −20°C and spinning rate of 8000Hz acquired at 14.1 T field strength. Dashed lines indicate the peak corresponding to the labeled cysteines.

Another residue whose side chain can be modified is tyrosine. Richards et al have proposed an electrochemical method for the nitration of the tyrosine ring at positions 3 in different proteins [184]. Tyrosine can also be mono-fluorinated by electrophilic substitution using acetyl hypofluorite in mild conditions and high yields (50–65%) [185].

Reductive methylation of lysine side chain has been used in many solution NMR studies to detect protein-protein interactions and ligand binding. The reaction occurs by addition of 13C labeled formaldehyde to the protein solution in reducing condition [186]. If sufficient formaldehyde is present, the side-chain of lysine residues will form a tertiary ammine with two methyl-group substitutions [187]. This approach has been successfully applied by Kobilka and co. for the solution NMR study of the β2-Adrenergic Receptor [188].

7.2 Spin labeling in NMR

Spin labeling refers to the covalent attachment of molecules with one or more unpaired electrons to proteins. Traditionally spin labeling has been used to study polypeptides by electron spin resonance, however, the effects of unpaired electron on the relaxation of nuclei is becoming routine in protein NMR studies [92, 189, 190]. Paramagnetic-based distance restraints have been used for the refinement of membrane protein structures [145] and for the positioning of membrane proteins in the lipid bilayers or detergent micelle [92].

Spin labeling is usually achieved post-translationally by in-vitro chemical reactions involving cysteines through disulfide formation [191, 192] or lysines [172].

All these chemical methods must be used with caution to ensure that the reaction does not jeopardize the structural integrity or function of the protein. Furthermore, if the residues to be labeled are found buried in the in the core of soluble proteins or in trans-membrane segments of membrane proteins, they might not be accessible to the labeling reagent.

8. CONCLUSIONS

The investigation of membrane proteins by NMR is a complex endeavor, but thanks to the development of improved instrumentation and production methods it is becoming increasingly feasible. New pulse sequences are continuously being devised that require specific labeling schemes, such as those described in this chapter. At the same time methods for the production of larger and more complex membrane proteins are also being actively developed.

Taken together, these accomplishments will permit an increasing number of medically relevant membrane proteins and protein complexes to be studied.

Finally, we should point out that this chapter is not exhaustive of this field, which is in continuous evolution. Most of the examples reported are based on our own experience with membrane protein structural biology. The inevitable gaps present in this Chapter are filled in the other chapters of this book by outstanding scientists in the field of structural biology.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the U.S. National Institutes of Health (GM064742 and GM072701 to GV).

ABBREVIATIONS

- SolNMR

Solution NMR

- SSNMR

Solid-State NMR

- O-SSNMR

Oriented SSNMR

- MAS-SSNMR

Magic-Angle-Spinning SSNMR

- PISEMA

Polarization Spin Exchange at the Magic Angle

REFERENCES

- 1.Crespi HL, Katz JJ. High resolution proton magnetic resonance studies of fully deuterated and isotope hybrid proteins. Nature. 1969;224:560–562. doi: 10.1038/224560a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Crespi HL, Rosenberg RM, Katz JJ. Proton magnetic resonance of proteins fully deuterated except for 1H-leucine side chains. Science. 1968;161:795–796. doi: 10.1126/science.161.3843.795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Putter I, Barreto A, Markley JL, Jardetzky O. Nuclear magnetic resonance studies of the structure and binding sites of enzymes. X. preparation of selectively deuterated analogs of staphylococcal nuclease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1969;64:1396–1403. doi: 10.1073/pnas.64.4.1396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Markley JL, Putter I, Jardetzky O. High-resolution nuclear magnetic resonance spectra of selectively deuterated staphylococcal nuclease. Science. 1968;161:1249–1251. doi: 10.1126/science.161.3847.1249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ohki S, Kainosho M. Stable isotope labeling methods for protein NMR spectroscopy. Prog Nucl Magn Reson Spectrosc. 2008;53:208–226. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim HJ, Howell SC, Van Horn WD, Jeon YH, Sanders CR. Recent advances in the application of solution NMR spectroscopy to multi-span integral membrane proteins. Prog Nucl Magn Reson Spectrosc. 2009;55:335–360. doi: 10.1016/j.pnmrs.2009.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ruschak AM, Kay LE. Methyl groups as probes of supra-molecular structure, dynamics and function. J Biomol NMR. 2010;46:75–87. doi: 10.1007/s10858-009-9376-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wallin E, von Heijne G. Genome-wide analysis of integral membrane proteins from eubacterial, archaean, and eukaryotic organisms. Protein Sci. 1998;7:1029–1038. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560070420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ahram M, Litou ZI, Fang R, Al-Tawallbeh G. Estimation of membrane proteins in the human proteome. In Silico Biol. 2006;6:379–386. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gilman AG. G proteins: Transducers of receptor-generated signals. Annu Rev Biochem. 1987;56:615–649. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.56.070187.003151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wettschureck N, Offermanns S. Mammalian G proteins and their cell type specific functions. Physiol Rev. 2005;85:1159–1204. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00003.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hille B. Ion channels of excitable membranes. Sunderland, MA: Sinauer Associates; 2001. p. 814. [8]. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brini M, Carafoli E. Calcium pumps in health and disease. Physiol Rev. 2009;89:1341–1378. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00032.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Traaseth NJ, et al. Structural and dynamic basis of phospholamban and sarcolipin inhibition of ca(2+)-ATPase. Biochemistry. 2008;47:3–13. doi: 10.1021/bi701668v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Page RC, et al. Comprehensive evaluation of solution nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy sample preparation for helical integral membrane proteins. J Struct Funct Genomics. 2006;7:51–64. doi: 10.1007/s10969-006-9009-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eshaghi S, et al. An efficient strategy for high-throughput expression screening of recombinant integral membrane proteins. Protein Sci. 2005;14:676–683. doi: 10.1110/ps.041127005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tate CG. Overexpression of mammalian integral membrane proteins for structural studies. FEBS Lett. 2001;504:94–98. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(01)02711-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sambrook J, Fritsch EF, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ross A, et al. Optimised fermentation strategy for 13C/15N recombinant protein labelling in escherichia coli for NMR-structure analysis. J Biotechnol. 2004;108:31–39. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2003.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cai M, et al. An efficient and cost-effective isotope labeling protocol for proteins expressed in escherichia coli. J Biomol NMR. 1998;11:97–102. doi: 10.1023/a:1008222131470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Marley J, Lu M, Bracken C. A method for efficient isotopic labeling of recombinant proteins. J Biomol NMR. 2001;20:71–75. doi: 10.1023/a:1011254402785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Studier FW. Protein production by auto-induction in high density shaking cultures. Protein Expr Purif. 2005;41:207–234. doi: 10.1016/j.pep.2005.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Suzuki M, Mao L, Inouye M. Single protein production (SPP) system in escherichia coli. Nat Protoc. 2007;2:1802–1810. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schneider WM, et al. Efficient condensed-phase production of perdeuterated soluble and membrane proteins. J Struct Funct Genomics. 2010;11:143–154. doi: 10.1007/s10969-010-9083-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Baneyx F, Mujacic M. Recombinant protein folding and misfolding in escherichia coli. Nat Biotechnol. 2004;22:1399–1408. doi: 10.1038/nbt1029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Goldbourt A, Day LA, McDermott AE. Assignment of congested NMR spectra: Carbonyl backbone enrichment via the entner-doudoroff pathway. J Magn Reson. 2007;189:157–165. doi: 10.1016/j.jmr.2007.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kunji ER, Slotboom DJ, Poolman B. Lactococcus lactis as host for overproduction of functional membrane proteins. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2003;1610:97–108. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2736(02)00712-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Janvilisri T, Shahi S, Venter H, Balakrishnan L, van Veen HW. Arginine-482 is not essential for transport of antibiotics, primary bile acids and unconjugated sterols by the human breast cancer resistance protein (ABCG2) Biochem J. 2005;385:419–426. doi: 10.1042/BJ20040791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Koth CM, Payandeh J. Strategies for the cloning and expression of membrane proteins. Adv Protein Chem Struct Biol. 2009;76:43–86. doi: 10.1016/S1876-1623(08)76002-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lin-Cereghino J, Lin-Cereghino GP. Vectors and strains for expression. Methods Mol Biol. 2007;389:11–26. doi: 10.1007/978-1-59745-456-8_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gossert AD, et al. A simple protocol for amino acid type selective isotope labeling in insect cells with improved yields and high reproducibility. J Biomol NMR. 2011 doi: 10.1007/s10858-011-9570-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Werner K, Richter C, Klein-Seetharaman J, Schwalbe H. Isotope labeling of mammalian GPCRs in HEK293 cells and characterization of the C-terminus of bovine rhodopsin by high resolution liquid NMR spectroscopy. J Biomol NMR. 2008;40:49–53. doi: 10.1007/s10858-007-9205-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stewart JM, Young JD. Solid phase peptide synthesis. Rockford, Ill.: Pierce Chemical Co.; 1984. p. 176. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Klammt C, et al. Cell-free production of G protein-coupled receptors for functional and structural studies. J Struct Biol. 2007;158:482–493. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2007.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Klammt C, et al. Cell-free expression as an emerging technique for the large scale production of integral membrane protein. FEBS J. 2006;273:4141–4153. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2006.05432.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Klammt C, et al. High level cell-free expression and specific labeling of integral membrane proteins. Eur J Biochem. 2004;271:568–580. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.2003.03959.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wu PS, et al. Amino-acid type identification in 15N-HSQC spectra by combinatorial selective 15N-labelling. J Biomol NMR. 2006;34:13–21. doi: 10.1007/s10858-005-5021-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ozawa K, Wu PS, Dixon NE, Otting G. N-labelled proteins by cell-free protein synthesis. strategies for high-throughput NMR studies of proteins and protein-ligand complexes. FEBS J. 2006;273:4154–4159. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2006.05433.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jeremy Craven C, Al-Owais M, Parker MJ. A systematic analysis of backbone amide assignments achieved via combinatorial selective labelling of amino acids. J Biomol NMR. 2007;38:151–159. doi: 10.1007/s10858-007-9157-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Parker MJ, Aulton-Jones M, Hounslow AM, Craven CJ. A combinatorial selective labeling method for the assignment of backbone amide NMR resonances. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:5020–5021. doi: 10.1021/ja039601r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kainosho M, Güntert P. SAIL – stereo-array isotope labeling. Q Rev Biophys. 2009;42:247–300. doi: 10.1017/S0033583510000016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Xie H, Guo XM, Chen H. Making the most of fusion tags technology in structural characterization of membrane proteins. Mol Biotechnol. 2009;42:135–145. doi: 10.1007/s12033-009-9148-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Waugh DS. Making the most of affinity tags. Trends Biotechnol. 2005;23:316–320. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2005.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Arnau J, Lauritzen C, Petersen GE, Pedersen J. Reprint of: Current strategies for the use of affinity tags and tag removal for the purification of recombinant proteins. Protein Expr Purif. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.pep.2011.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kapust RB, Waugh DS. Controlled intracellular processing of fusion proteins by TEV protease. Protein Expr Purif. 2000;19:312–318. doi: 10.1006/prep.2000.1251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Abdullah N, Chase HA. Removal of poly-histidine fusion tags from recombinant proteins purified by expanded bed adsorption. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2005;92:501–513. doi: 10.1002/bit.20633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jenny RJ, Mann KG, Lundblad RL. A critical review of the methods for cleavage of fusion proteins with thrombin and factor xa. Protein Expr Purif. 2003;31:1–11. doi: 10.1016/s1046-5928(03)00168-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kapust RB, Tozser J, Copeland TD, Waugh DS. The P1' specificity of tobacco etch virus protease. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2002;294:949–955. doi: 10.1016/S0006-291X(02)00574-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Buck B, et al. Overexpression, purification, and characterization of recombinant ca-ATPase regulators for high-resolution solution and solid-state NMR studies. Protein Expr Purif. 2003;30:253–261. doi: 10.1016/s1046-5928(03)00127-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hu J, et al. Structural biology of transmembrane domains: Efficient production and characterization of transmembrane peptides by NMR. Protein Sci. 2007;16:2153–2165. doi: 10.1110/ps.072996707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.McIntosh LP, Dahlquist FW. Biosynthetic incorporation of 15N and 13C for assignment and interpretation of nuclear magnetic resonance spectra of proteins. Q Rev Biophys. 1990;23:1–38. doi: 10.1017/s0033583500005400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hoogstraten CG, Johnson JE. Metabolic labeling: Taking advantage of bacterial pathways to prepare spectroscopically useful isotope patterns in proteins and nucleic acids. Concepts in Magnetic Resonance Part A. 2008;32A:34–55. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Fiaux J, Bertelsen EB, Horwich AL, Wuthrich K. Uniform and residue-specific 15N-labeling of proteins on a highly deuterated background. J Biomol NMR. 2004;29:289–297. doi: 10.1023/B:JNMR.0000032523.00554.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Suzuki H, et al. Isotopic labeling of proteins by utilizing photosynthetic bacteria. Anal Biochem. 2005;347:324–326. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2005.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.LeMaster DM, LaIuppa JC, Kushlan DM. Differential deuterium isotope shifts and one-bond 1H-13C scalar couplings in the conformational analysis of protein glycine residues. J Biomol NMR. 1994;4:863–870. doi: 10.1007/BF00398415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Grzesiek S, Anglister J, Ren H, Bax A. Carbon-13 line narrowing by deuterium decoupling in deuterium/carbon-13/nitrogen-15 enriched proteins. application to triple resonance 4D J connectivity of sequential amides. J Am Chem Soc. 1993;115:4369–4370. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gardner KH, Kay LE. The use of 2H, 13C, 15N multidimensional NMR to study the structure and dynamics of proteins. Annu Rev Biophys Biomol Struct. 1998;27:357–406. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.27.1.357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.White SH, Wimley WC. Membrane protein folding and stability: Physical principles. Annu Rev Biophys Biomol Struct. 1999;28:319–365. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.28.1.319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Veglia G, Zeri AC, Ma C, Opella SJ. Deuterium/hydrogen exchange factors measured by solution nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy as indicators of the structure and topology of membrane proteins. Biophys J. 2002;82:2176–2183. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3495(02)75564-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Oxenoid K, Kim HJ, Jacob J, Sonnichsen FD, Sanders CR. NMR assignments for a helical 40 kDa membrane protein. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:5048–5049. doi: 10.1021/ja049916m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Katz JJ, Crespi HL. Deuterated organisms: Cultivation and uses. Science. 1966;151:1187–1194. doi: 10.1126/science.151.3715.1187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Meilleur F, Contzen J, Myles DA, Jung C. Structural stability and dynamics of hydrogenated and perdeuterated cytochrome P450cam (CYP101) Biochemistry. 2004;43:8744–8753. doi: 10.1021/bi049418q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Brockwell D, et al. Physicochemical consequences of the perdeuteriation of glutathione S-transferase from S. japonicum. Protein Sci. 2001;10:572–580. doi: 10.1110/ps.46001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Schubert M, Smalla M, Schmieder P, Oschkinat H. MUSIC in triple-resonance experiments: Amino acid type-selective (1)H-(15)N correlations. J Magn Reson. 1999;141:34–43. doi: 10.1006/jmre.1999.1881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]