Abstract

Purpose

Until now there have been many reports on hemivertebra resection. But there were no large series on the posterior hemivertebra resection with bisegmental fusion. This is a retrospective study to evaluate the surgical outcomes of posterior hemivertebra resection only with bisegmental fusion for congenital scoliosis caused by fully segmented non-incarcerated hemivertebra.

Methods

In our study, 36 consecutive cases (19 males, 17 females) diagnosed with congenital scoliosis, resulting from fully segmented non-incarcerated hemivertebra, treated by posterior hemivertebra resection with bisegmental fusion were investigated retrospectively, with at least a 3 year follow-up period (36–106 months).

Results

The total number of resected hemivertebra was 36. Mean operation time was 188.6 min with average blood loss of 364.2 ml. The segmental scoliosis was corrected from 36.6° to 5.1° with a correction rate of 86.1 %, and segmental kyphosis(difference to normal segmental alignment) from 21.2° to 5.8° at the latest follow-up. The correction rate of the compensatory cranial and caudal curve is 76.4 and 75.1 %. Unanticipated surgeries were performed on eight patients, including one delayed wound healing, two pedicle fractures, one progressive deformity and four implants removals.

Conclusions

Posterior hemivertebra resection with bisegmental fusion allows for early intervention in very young children. Excellent correction can be obtained while the growth potential of the unaffected spine could be preserved well. However, it is not indicated for the hemivertebra between L5 and S1. The most common complication of this procedure is implant failure. Furthermore, in the very young children we noted that although solid fusion could be observed in the fusion level, implants migration may still happen during the time of adolescence, when the height of the body developed rapidly. So a close follow-up is necessary.

Keywords: Posterior instrumentation, Bisegmetal fusion, Hemivertebra

Introduction

As a kind of failures of formation, hemivertebra is the most frequent pathology of congenital scoliosis. The natural history of hemivertebra has been well understood. Except for the incarcerated, unsegmented or balanced ones, hemivertebra usually create a wedge-shaped deformity, which progresses during further spinal growth. Besides the local deformity, the imbalance of spine will lead to compensatory deformities. Because of the predicted poor prognosis of most hemivertebra, early surgical intervention is required in most cases [1, 2]. Since Royle first reported on hemivertebra resection, several surgical procedures have been introduced to deal with this kind of deformity [4–21, 25]. In this study, we will discuss the results and complications of posterior hemivertebra resection with bisegmental fusion for the congenital scoliosis causing by a single fully segmented, non-incarcerated hemivertebra.

Materials and methods

Thirty-six consecutive patients with hemivertebra treated by posterior hemivertebra resection with bisegmental fusion were evaluated by retrospective chart and radiograph. The patients included 19 boys and 17 girls with a mean age of 4 years and 11 months at surgery (Table 1). All surgeries were performed by the same surgeon.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics

| Sex | Age (months) |

Location | Op-time (min) |

Blood loss (ml) |

Bonegraft/anterior reconstruction | Follow up (months) |

Implants | Complications | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | F | 19 | Between T4 and T5 | 165 | 80 | Autograft/N | 106 | Isola | N |

| 2 | M | 66 | Between L1 and L2 | 160 | 450 | Autograft/N | 102 | CDH | N |

| 3 | M | 37 | T11 | 175 | 300 | Autograft/N | 93 | USS | Junctional Kyphosis |

| 4 | F | 49 | L2 | 240 | 200 | Autograft/N | 101 | Moss-Miami | N |

| 5 | F | 36 | L2 | 195 | 200 | Autograft/N | 92 | USS | N |

| 6 | F | 123 | T12 | 180 | 1,000 | Autograft/N | 92 | Moss-Miami | N |

| 7 | F | 121 | L1 | 165 | 400 | Autograft/N | 91 | TSRH | N |

| 8 | F | 37 | Between L4 and L5 | 220 | 300 | Autograft/N | 90 | USS | Rod breakge |

| 9 | M | 49 | T10 | 180 | 370 | Autograft + novabone/N | 86 | CDH | Pedicle Fracture |

| 10 | M | 18 | T9 | 200 | 200 | Autograft + allograft/N | 78 | CDH | N |

| 11 | M | 86 | Between L3 and L4 | 145 | 600 | Autograft/N | 76 | CDH | N |

| 12 | F | 129 | Between L3 and L4 | 185 | 500 | Autograft/N | 74 | CDH | N |

| 13 | M | 72 | Between L1 and L2 | 140 | 300 | Autograft/N | 66 | CDH | N |

| 14 | F | 75 | L3 | 400 | 400 | Autograft/Mesh cage | 64 | CDH | N |

| 15 | F | 24 | Between L4 and L5 | 150 | 300 | Autograft + allograft/N | 63 | CDH | N |

| 16 | M | 29 | Between T11 and T12 | 300 | 800 | Autograft + allograft/N | 63 | CDH | N |

| 17 | M | 90 | Between L3 and L4 | 215 | 340 | Autograft + allograft/N | 56 | CDH | N |

| 18 | M | 125 | Between T12 and L1 | 180 | 420 | Autograft + allograft/N | 54 | CDH | N |

| 19 | F | 47 | L1 | 210 | 300 | Autograft + allograft/N | 54 | CDH | Wound delayed union |

| 20 | M | 28 | L2 | 160 | 120 | Autograft + novabone/N | 52 | CDH | N |

| 21 | M | 62 | Between T13 and L1 | 180 | 400 | Autograft + novabone/N | 52 | CDH | N |

| 22 | M | 96 | Between L3 and L4 | 210 | 400 | Autograft + novabone/N | 52 | CDH | N |

| 23 | M | 28 | L1 | 190 | 500 | Autograft + novabone/N | 52 | USS | N |

| 24 | F | 28 | L2 | 190 | 250 | Autograft + novabone/N | 46 | CDH | N |

| 25 | F | 57 | L2 | 200 | 240 | Autograft + novabone/N | 46 | CDH | Pedicle Fracture |

| 26 | F | 78 | Between L3 and L4 | 180 | 500 | Autograft/N | 43 | CDH | N |

| 27 | F | 76 | Between L4 and L5 | 180 | 250 | Autograft/N | 43 | CDH | N |

| 28 | M | 58 | T12 | 185 | 370 | Autograft/N | 43 | USS | N |

| 29 | M | 38 | Between L3 and L4 | 130 | 260 | Autograft + allograft/N | 42 | CDH | N |

| 30 | M | 50 | L2 | 120 | 260 | Autograft + novabone/N | 42 | USS | N |

| 31 | F | 98 | Between L2 and L3 | 310 | 380 | Autograft + novabone/N | 41 | USS | N |

| 32 | F | 61 | Between L4 and L5 | 150 | 270 | Autograft + Novabone/N | 39 | CDH | N |

| 33 | M | 25 | T12 | 140 | 300 | Autograft + novabone/Mesh cage | 37 | USS | N |

| 34 | M | 40 | Between L1 and L2 | 155 | 500 | Autograft + novabone/Mesh cage | 37 | CDH | N |

| 35 | F | 48 | Between L3 and L4 | 165 | 420 | Autograft + novabone/Mesh cage | 37 | USS | N |

| 36 | M | 34 | T12 | 140 | 230 | Autograft + novabone/N | 36 | USS | N |

| Average | 59 | 188.6 | 364.2 | 62.3 |

The locations of the hemivertabra were as follows: 2 thoracic (T1-T9), 21 thoracolumbar (T10-L2), and 13 lumbar (L3-L5). Nine cases had contralateral bar or rib synostosis.

Measurements were taken from standing long cassette anterior–posterior and lateral radiographs. The segmental scoliosis was measured from the upper endplate of the vertebra above the hemivertebra to the lower endplate of the vertebra below the hemivertebra. And the cranial and caudal were also measured as Ruf described in 2002 [14]. Trunk shift is defined as the perpendicular distance (mm) from the sacrum center to the plumb line drawn from the midpoint of the C7 vertebra body. The segmental kyphosis was measured in the same way as the segmental scoliosis on the coronal plane; differences between the measured values and the normal alignment were recorded.

Surgical technique

All patients were treated by posterior hemivertebra resection with pedicle screws.

After general anesthesia the patient was placed in the prone position on a radiolucent operating table. A standard midline incision was made, and sub-periosteal dissection was performed to expose the hemivertebra and the vertebra that needed to be fused, including the lamina, transverse processes, facet joints, and the surplus rib head on the convex side of the thoracic spine. Gauge 20 needles were inserted into the pedicles of the hemivertebra and the adjacent vertebra. Fluoroscopy was used to confirm the hemivertebra, and the pedicle screws were inserted after tapping.

The posterior elements of the hemivertebra, including the lamina, upper and lower facets, and the transverse process were removed to expose the pedicle, and the nerve roots above and below. In the thoracic spine, the rib head and the proximal part of the surplus rib on the convex side were exposed and resected. The pleura was protected carefully. The dura was cautiously elevated posteriorly, and the epidural veins were pre-cauterized by bipolar cautery. Then the lateral cortex of the hemivertebra was exposed by blunt dissection. A pre-contoured rod was connected to the screws on the concave side before removing the vertebra body to stabilize the spine. Osteotomies were used to remove the vertebra body along the cartilage endplate. The cancellous bone was preserved for grafting. We made sure that the upper and lower discs, including the cartilage endplate, were completely removed until the bleeding bone was reached. The opposite disc was also removed. Then, the endplate was adequately shaped to form a “V” shaped space. In patients with contralateral bar and rib synostosis, the bar was cut, and the synostosed rib heads were removed.

A pre-contoured rod was then connected to the screws on the convex side. Gradual compression was applied while leaving the concave rod unlocked until the gap was closed. Anterior reconstruction with a titanium mesh cage was performed when a larger hemivertebra made the gap hard to close by compression. This procedure could help correct the kyphosis deformity and achieve lordosis. Caution was taken to make sure that the exiting nerve roots and the dura were not impinged. If the dura was buckled severely, part of the upper and lower lamina was removed, or a mesh cage was inserted anteriorly.

Decortication of the posterior elements was performed after the correction. Autogenous bone from the hemivertebra was used for the posterolateral fusion.

Sensory evoked potential (SEP) and motor evoked potential (MEP) were used intra operatively.

When the patient started to walk after surgery, a two-piece plastic brace was used for at least 3 months.

Results

A total of 36 hemivertabra were resected in 36 patients. The average follow-up was 62.3 months (36–106 months). The average operation time was 188.6 min (120–400 min), the average intra operative blood loss was 364.2 ml (80–1,000 ml).

General correction results

The correction in the coronal and sagittal plane was presented in Table 2. There was 86.1 % of segmental scoliosis correction with a 1.1° loss of correction. In the sagittal plane, the correction rate was 72.6 % and 1° improvement was noted at the latest follow-up. The trunk shift had a progressive improvement during the follow-up.

Table 2.

Correction results

| Segmental curve (o) | Trunkshift (mm) | Compensatory cranial curve (o) | Compensatory caudal curve (o) | Segmental kyphpsis (difference to norm) (o) | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre | Post | Follow-up | Pre | Post | Follow-up | Pre | Post | Follow-up | Pre | Post | Follow-up | Pre | Post | Follow-up | |

| 1 | 40 | 15 | 12 | 10 | 30 | 20 | 4 | 8 | 6 | 40 | 23 | 25 | 3 | −1 | −1 |

| 2 | 20 | 1 | 3 | 10 | 16.7 | 5 | 18 | 3 | 4 | 10 | 4 | 5 | 31 | 7 | 7 |

| 3 | 33 | 2 | 6 | 10 | 7.1 | 14.4 | 12 | 18 | 5 | 20 | 8 | 7 | 21 | 8 | 10 |

| 4 | 39 | 3 | 6 | 15 | 10 | 5 | 14 | 12 | 4 | 22 | 8 | 1 | 12.5 | 7.5 | 9.5 |

| 5 | 30 | 1 | 1 | 2.1 | 3.3 | 1.5 | 20 | 18 | 8 | 18 | 6 | 8 | 31 | 6 | 9 |

| 6 | 30 | 3 | 4 | 25 | 5 | 7 | 22 | 7 | 4 | 25 | 15 | 6 | 12 | 8 | 4 |

| 7 | 26 | 1 | 2 | 3.1 | 5 | 15.3 | 20 | 6 | 2 | 16 | 4 | 3 | 20 | −1 | 6 |

| 8 | 39 | 8 | 10 | 40 | 3 | 8 | 10 | 6 | 8 | 16 | 4 | 6 | 19 | 1 | 3 |

| 9 | 22 | 4 | 6 | 10 | 11 | 5 | 14 | 8 | 6 | 8 | 3 | 4 | 14 | 10 | 9 |

| 10 | 34 | 6 | 7 | 5 | 22 | 9 | 10 | 8 | 6 | 18 | 8 | 9 | 21 | 1 | −2 |

| 11 | 38 | 1 | 0 | 23 | 3 | 2 | 12 | 7 | 1 | 24 | 4 | 1 | 11 | 6 | 7 |

| 12 | 40 | 5 | 5 | 13 | 10 | 2 | 35 | 16 | 18 | 8 | 3 | 1 | 20 | 1 | 0 |

| 13 | 30 | 1 | 3 | 50 | 15 | 2 | 24 | 2 | 1 | 8 | 2 | 3 | 22 | 17 | 12 |

| 14 | 46 | 1 | 1 | 60 | 20 | 30 | 42 | 4 | 1 | 30 | 6 | 4 | 48.5 | −2.5 | 15.5 |

| 15 | 38 | 4 | 4 | 45 | 40 | 10 | 12 | 1 | 2 | 29 | 4 | 6 | 53 | 23 | 15 |

| 16 | 36 | 2 | 4 | 12.2 | 16.7 | 20 | 16 | 8 | 2 | 24 | 4 | 4 | 14 | 9 | 9 |

| 17 | 35 | 3 | 1 | 5 | 13.3 | 5 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 20 | 8 | 6 | 10 | 3 | 3 |

| 18 | 32 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 13.3 | 10 | 8 | 2 | 6 | 22 | 6 | 2 | 30 | 8 | 6 |

| 19 | 40 | 2 | 3 | 23.3 | 5 | 2 | 16 | 2 | 1 | 16 | 4 | 2 | 35 | 14 | 6 |

| 20 | 34 | 0 | 3 | 7 | 10 | 5 | 8 | 1 | 2 | 12 | 2 | 1 | 8 | 8 | 7 |

| 21 | 50 | 10 | 12 | 1 | 4 | 2 | 14 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 10 | −1 | −2 | −3 |

| 22 | 40 | 1 | 1 | 10 | 5 | 1 | 25 | 1 | 3 | 20 | 1 | 2 | 2 | −2 | −3 |

| 23 | 35 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 9.2 | 2 | 20 | 5 | 2 | 10 | 2 | 1 | 10 | −3 | −4 |

| 24 | 36 | 1 | 1 | 5 | 12.5 | 3 | 12 | 5 | 2 | 18 | 1 | 8 | 31 | 15 | 9 |

| 25 | 56 | 10 | 11 | 18 | 25 | 10 | 30 | 15 | 8 | 26 | 6 | 2 | 18 | 14 | 12 |

| 26 | 34 | 9 | 11 | 19 | 30 | 17.5 | 30 | 10 | 4 | 10 | 8 | 2 | 31 | 19 | 15 |

| 27 | 36 | 8 | 8 | 10 | 35 | 15 | 15 | 4 | 5 | 20 | 9 | 5 | 18 | 3 | 2 |

| 28 | 44 | 6 | 8 | 35 | 20 | 15 | 34 | 8 | 4 | 38 | 6 | 8 | 23 | 11 | 13 |

| 29 | 40 | 6 | 8 | 30 | 35 | 18 | 15 | 4 | 6 | 20 | 1 | 2 | 26.5 | 11.5 | 12.5 |

| 30 | 40 | 1 | 2 | 14.1 | 3 | 2 | 10 | 8 | 6 | 28 | 1 | 0 | 40 | 8 | 10 |

| 31 | 30 | 2 | 8 | 22.5 | 10 | 5 | 15 | 1 | 7 | 24 | 3 | 10 | 23 | 0 | −1 |

| 32 | 40 | 6 | 2 | 21.5 | 5 | 4 | 18 | 2 | 5 | 23 | 5 | 9 | 19.5 | 7.5 | −0.5 |

| 33 | 35 | 2 | 2 | 5 | 5 | 2 | 15 | 10 | 0 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 16.5 | 1.5 | 6.5 |

| 34 | 36 | 10 | 11 | 6.7 | 15 | 5 | 15 | 1 | 10 | 21 | 13 | 5 | 5 | 1 | −2 |

| 35 | 42 | 4 | 5 | 25.5 | 4.5 | 2 | 10 | 0 | 10 | 30 | 2 | 8 | 24.5 | 0.5 | −0.5 |

| 36 | 40 | 5 | 4 | 10.5 | 15.5 | 5 | 25 | 2 | 2 | 30 | 15 | 5 | 36 | 5 | 2 |

| Average | 36.6 | 4.0 | 5.1 | 17.1 | 14.6 | 7.4 | 17.4 | 6.7 | 4.1 | 19.3 | 5.5 | 4.8 | 21.2 | 6.8 | 5.8 |

Complications and unanticipated surgeries

There were no neurologic complications. Convex pedicles were overloaded and broken in two patients, and revision surgery was indicated, necessitating the inclusion of one additional segment above and below into the instrumentation. One rod breakage was noted 6 months after surgery, no revision surgery is needed because of the presented solid fusion. No rod migration or correction loss was noted during the following observation. One case developed delayed wound union. The wound healed 3 weeks after debridement. There was a progressive deformity of kyphosis 2 years after the operation and revision surgery was indicated.

Implants removal were performed in four patients. Two of them complained of the prominent implants. The X-ray and CT scan showed that the correction maintained well without any sign of implant failure. Solid fusion of the posterior elements and intervertebral space involved in the fusion region could be noted. In two patients we noted that when the height of the body developed fast during the time of adolescence, the pedicles of the instrumented vertebra were lengthened and implant migration happened, without loss of the correction. The CT scan showed that the posterior and interbody fusion was solid, and it was confirmed by the detection during the surgery of implants removal. As the bone mature has been nearly achieved in both the patients, the correction still maintained well, we only removed their implants and after that no correction loss happened until the latest follow-up.

Discussion

Fully segmented non-incarcerated hemivertebra has normal growth plates, leading to progressive deformity of the spine during further growth. As primarily unaffected neighboring vertebra will show asymmetric growth resulting from the local deformity and asymmetric loads, secondary deformities will develop gradually. Delayed treatment of this kind of deformity requires longer fusion with a high-risk of neurologic complications [1, 2]. So early surgical intervention is indicated to achieve correction of the local deformities. And with early correction of the primary deformities, secondary changes can be avoided.

The local deformity due to hemivertebra usually is mild during the early period of growth. And secondary deformities are limited. In the past several decades, many types of procedures have been introduced, including combined anterior and posterior epiphysiodesis, combined anterior and posterior epiphysiodesis with concave distraction, hemivertebra osteotomy by the egg-shell technique, hemivertebra resection by a combined anterior and posterior approach, and hemivertebra resection with a posterior-only approach [3–21, 25]. Ruf and Harms advocated early surgical intervention with posterior hemivertebra resection with transpedicular instrumentation. They reported that it was safe to use pedicle screws even in very young children [15]. In 2003, they reported 28 cases younger than 6 years old with a mean follow-up time of 3.5 years. Twenty-five cases were treated by bisegmental fusion of the adjacent vertebra. Pedicle screws were used, and the mean correction rate of the segmental scoliosis was 71.1 %. The cranial and caudal compensatory curve decreased with rate of 78 and 65 %. The correction of segmental kyphosis is 63 %. Complications included two pedicle fractures, three instrumentation failures, two additional surgeries for curve progression, and one infection [16]. In 2009, they reported 41 cases younger than 6 years old with a mean follow-up of 6 years and 2 months, 23 of which were treated with bisegmental fusion. In patients without bar formation, there was a correction rate of 80.5 % of the main curve. The cranial and caudal compensatory curve improved with rate of 80 and 76.5 %. The segmental kyphosis improved from 22° to 8°. In patients with bar formation, the improvement of the main curve was 66.7 %, and the correction rate of cranial and caudal compensatory curve is 74.8 and 75.1 %. The segmental kyphosis improvement was 62.5 % (from 24° to 9°). The complications included three implant failures, three convex pedicle breakages and two progressed deformities after the surgery. Revision surgeries were performed on these cases [19].

In the current study, the correction of segmental scoliosis was 86.1 %. The cranial and caudal compensatory curve improved spontaneously with rate of 76.4 and 75.1 %. The correction of segmental kyphosis is 72.6 %. The continuous improvement of trunk shift has been observed during the follow-up (from 17.1 to 7.4 mm). Although only segmental deformities were corrected and fused, secondary deformities were all nearly corrected after the operation and no significant loss was noted during the follow-up. With this procedure we can achieve a straight spine with normal sagittal alignment. As the diameter of the spinal canal is fully mature within the first year of life [22–24], the pedicle screw will not result in spinal stenosis even in very young children.

Implant failure is a big challenge of the posterior hemivertebra resection of children [16, 19, 25]. Fractures of the convex pedicle are the most common complications. Except for technical error and improper instrumentation, poor quality of bone in very young patients is the main cause of failure. In our series, both the pedicle fractures required revision. To deal with this problem, we suggest that besides bony parts of hemivertebra, we should remove the annulus and cartilage completely. The proper size of screws should be chosen with the help of pre operative CT scans. During the surgery, the pedicle tunnel must be prepared delicately under the guide of fluoroscopy. The contralateral bar or rib synostosis should be removed before the compression. Thus, release of the correction zone could be attained, which is helpful to decrease the stress of the convex pedicles during the compression. If the gap left after resection of a large hemivertebra is hard to close or pronounced kyphosis is noted (>40°), anterior reconstruction with mesh cage is indicated to decrease the stress during the compression and provide a fulcrum for the correction of the kyphosis (Fig. 1). As the thoracic cage can provide extra power of resistance and increase the stress during the compression, it is necessary to remove the rib head completely, when treating with thoracic hemivertebra. Ruf reported that temporary extraperiosteal instrumentation could be used to help decrease the chance of implant failure [19]; and the additional implants should be removed 3 months after the surgery. We used brace in all the patients for at least 3 months after the surgery to help maintain stability and confirm fusion.

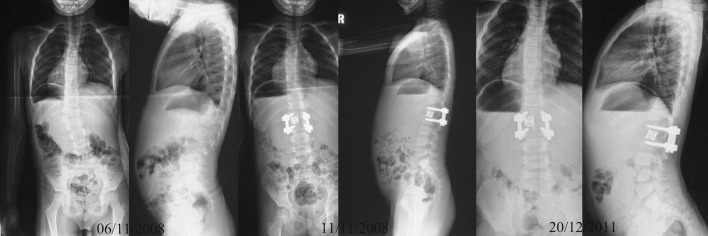

Fig. 1.

A 3-year-old boy with hemivertebra between T12 and L1, pre operative radiograph showed pronounced segmental scoliosis and kyphosis. Anterior reconstruction with a mesh cage was used to help to correct the kyphosis and decrease the stress of the convex pedicle. The correction was good. And it maintained well during the follow-up

In the current study, these procedures were all performed on young children. As the growth potential is great, late complications may occur. Ruf reported that vertical growth still existed within the fused level after posterior hemivertebtra resection [19]. And in our series, although solid posterior fusion was detected in the surgery and CT scan, two implants migration without significant loss of correction occurred in two cases after the adolescence. The pedicles of the upper vertebra were lengthened, suggesting the growth of the anterior column. Both of them were instrumented with monoaxial screw which might be the problem. As the fusion was solid, no correction loss occurred (Fig. 2). There was a progressive deformity of junctional kyphosis. The hemivertebra resected was located in the thoracolumbar region (between L1 and L2). And before the revision surgery we noted on the CT scan that there is a segmental failure of anterior column between L2 and L3, that may be the reason of the progressive kyphosis after the initial surgery. This case suggested that the surgeon should think carefully when treating a single hemivertebra combing with other deformities in adjacent spine.

Fig. 2.

A 7-year-old boy with hemivertebra between L3 and L4, presenting segmental scoliosis while the compensatory deformities was mild. We performed posterior hemivertebra and instrumentation with monoaxial pedicle screws. The post operative X-ray showed that the correction was excellent. His body height developed from 125 to 177 cm during 76 months follow-up. Although the correction was maintained well, the screws of the upper vertebra migrated downwards. Solid fusion could be noted on the X-ray and CT scan. We removed the implants. The fusion of the posterior elements was confirmed during the surgery. No correction loss was noted on the X-ray, 6 months after implants removal

Most of the time, hemivertebra resection with bisegmental fusion in lumbar spine is safe and provides stable correction. But the treatment of hemivertebra between L5 and S1 may be difficult. We failed when we tried to treat three patients with this kind of deformity with posterior hemivertebra resection and bisegmental fusion. During the surgeries we found that the gap left by the hemivertebra was hard to close only with one screw above and below on the convex side. Furthermore, under the guide of fluoroscopy, we found that it was difficult to achieve and maintain coronal balance during the surgery. So we gave up and changed to the longer fusion. As there is obvious stress concentration in the lumbosacral region, it is more unstable. After the resection, the space left by hemivertebra was very hard to close with limited power of two screws. And the balance on the coronal plane of the body was hard to reconstruct, especially in patients with oblique sacrum. The release and distraction of the concave side combing with a mesh cage in the convex side may be helpful. So bisegmental fusion is not quite indicated here. Longer fusion can achieve better results. Furthermore, besides the hemivertebra exists, the endplate of S1 developed abnormally in some cases. The preoperative CT scan is very important and the surgeon should pay attention to the deformity of S1. Except for the hemvertebra resection, an osteotomy of the endplate of S1 may be needed to get a stable and balanced base for the spine.

Conclusion

Posterior hemivertebra resection with bisegmental fusion can be performed effectively and safely on very young children, saving motion segments. Thus, it is a good choice for children with congenital scoliosis, due to a single hemivertebra. To date, the results of most patients are excellent, with very little loss of correction during the follow-up. However, this procedure is not indicated for the hemvertebra between L5 and S1 according to our experiences. Monoaxial screw should not be used for this procedure. Implant failure is the biggest challenge, especially in the thoracic spine. As most of the patients in our series are very young and far from bone maturity, the follow-up duration is short. Late complications may still occur in the future.

IRB approval statement This study has been approved from the Institutional Review Board.

Conflict of interest

None.

References

- 1.McMaster MJ, Ohtsuka K. The natural history of congenital scoliosis: a study of 251 patients. J Bone Joint Surg[AM] 1982;64A:1128. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Winter RB, Moe JH, Eilers VE. Congenital scoliosis: a study of 234 patients treated and untreated. J Bone Joint Surg. 1968;50A:1. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bollini G, Docquier PL, Viehweger E, et al. Lumbar hemivertebra resection. J Bone Joint Surg [Am] 2006;88:1043–1052. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.E.00530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bollini G, Docquier PL, Viehweger E, et al. Thoracolumbar hemivertabra resection by double approach in a single procedure: long-term follow-up. Spine. 2006;31:1745–1757. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000224176.40457.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bradford DS, Boachie-Adjei O. One-stage anterior and posterior hemivertebral resection and arthrodesis for congenital scoliosis. J Bone Joint Surg [Am] 1990;72(4):536–540. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hedequist DJ, Hall JE, Emans JB. Hemivertebra excision in children via simultaneous anterior and posterior exposures. J Pediatr Orthop. 2005;25:60–63. doi: 10.1097/00004694-200501000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hedequist DJ, Hall JE, Emans JB. The safety and efficacy of spinal instrumentation in children with congenital spine deformities. Spine. 2004;29:2081–2086. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000138305.12790.de. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Holte DC, Winter RB, Lonstein JE, et al. Excision of hemivertabra and wedge resection in the treatment of congenital scoliosis. J Bone Joint Surg [Am] 1995;77:159–171. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199502000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.King KD, Lowery GL. Results of lumbar hemivertebral excision for congenital scoliosis. Spine. 1991;18:778–782. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199107000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lazar RD, Hall JE (1999) Simultaneous anterior and posterior hemivertebra excision. Clin Orthop Relat Res (364):76–84 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Leatherman KD, Dickson RA. Two-stage corrective surgery for congenital deformities of the spine. J Bone Joint Surg [Br] 1979;61:324–328. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.61B3.479255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bergoin M, Bollini G, Taibi L, et al. Excision of hemivertabra in children with congental scoliosis. Ital J Orthop Traumatol. 1986;12:179–184. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shono Y, Abumi K, Kaneda K. One-stage posterior hemivertebra resection and correction using segmental posterior instrumentation. Spine. 2001;26:752–757. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200104010-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ruf M, Harms J. Hemivertebra resection by a posterior approach: innovative operative technique and first results. Spine. 2002;27:1116–1123. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200205150-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ruf M, Harms J. Pedicle screws in 1- and 2-year-old children: technique, complications, and effect on further growth. Spine. 2002;27:E460–E466. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200211010-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ruf M, Harms J. Posterior hemivertebra resection with transpedicular instrumentation: early correction in children aged 1–6 years. Spine. 2003;28:2132–2138. doi: 10.1097/01.BRS.0000084627.57308.4A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nakamura H, Matsuda H, Konishi S, et al. Single-stage excision of hemivertabra via the posterior approach alone for congenital spine deformity: follow-up period longer than 10 years. Spine. 2002;27:110–115. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200201010-00026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Smith JT, Gollogly S, Dunn HK. Simultaneous anterior-posterior approach through a stotransversectomy for the treatment of congenital kyphosis and acquired kyphoscoliotic deformities. J Bone Joint Surg [Am] 2005;87:2281–2289. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.D.01795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ruf M, Jensen R, Letko L, et al. Hemivertebra resection and osteotomies in congenital spine deformity. Spine. 2009;34:1791–1799. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181ab6290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yaszay B, O'Brien M, Shufflebarger HL et al (2011) Efficacy of hemivertebra resection for congenital scoliosis: a multicenter retrospective comparison of three surgical techniques. Spine 24:2052–2060 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Polly DW, Jr, Rosner MK, Monacci W, et al. Thoracic hemivertebra excision in adults via a posterior-only approach: report of two cases. Neurosurg Focus. 2003;14(2):9–11. doi: 10.3171/foc.2003.14.2.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Papp T, Porter RW, Aspden RM. The growth of the lumbar vertebral canal. Spine. 1994;19:2770–2773. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199412150-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Porter RW, Pavitt D. The vertebral canal: I. Nutrition and development, an archaeological study. Spine. 1987;12:901–906. doi: 10.1097/00007632-198711000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zindrick MR, Knight GW, Sartori MJ, et al. Pedicle morphology of the immature thoracolumbar spine. Spine. 2000;25:2726–2735. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200011010-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang JG, Wang SR, Qiu GX, et al. The efficacy and complications of posterior hemivertebra resection. Eur Spine J. 2011;20:1692–1702. doi: 10.1007/s00586-011-1710-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]