Abstract

Introduction

The relation between radiological abnormalities on lumbar spine and low back pain (LBP) has been debated, presumably because of potential biases related to heterogeneity in selection of the subjects, radiological abnormalities at entry, or its cross-sectional observation in nature. Therefore, the aim of this study of a selected population of asymptomatic Japanese Self Defense Forces (JSDF) young adults male with normal lumbar radiographs was to investigate the incidence of newly developed lumbar degenerative changes at middle age and to study their association to LBP.

Subjects and methods

In 1990, 84 JSDF male military servicemen aged 18 years, without a history of LBP and radiological abnormal findings, were enrolled. After 20 years, 84 subjects were underwent repeated X-ray and completed questionnaires on current LBP and lifestyle factors.

Results

The prevalence of LBP was demonstrated 59 %, with 85 % of them showing mild pain. Analysis of lumbar radiographs revealed that 48 % had normal findings and 52 % had degenerative changes. The association between LBP and life style factors was not demonstrated. Lumbar spine in subjects with LBP was more degenerated than in those without. Although disc space narrowing and LBP did not achieve a statistical significance, a significant correlation existed between vertebral osteophyte and LBP in univariate and multivariate analysis (OR 3.0; 95 % CI 1.227–7.333).

Discussion and conclusions

This longitudinal study demonstrated the significant association between vertebral osteophyte and incidence of mild LBP in initially asymptomatic and radiologically normal subjects. These data provide the additional information concerning the pathology of LBP, but further study is needed to clarify the clinical relevance.

Keywords: Longitudinal study, Low back pain, Vertebral osteophytes, Military personnel

Introduction

Many investigations have been conducted to identify possible risk factors for low back pain (LBP). Certain evidences have been reported that psychological status and LBP on adolescence might be important predictors of LBP in adult [1, 2]. Although positive associations between LBP and some of lifestyle factors were reported [3], possible causal links have not been established. For the relation between LBP and radiological findings, previous studies have shown a lack of high concordance between LBP and radiologic abnormalities. Although Torgerson and Dotter [4] found that current LBP was associated with disc space narrowing in a hospital-based study, Hult [5] found no relationship between lumbar degenerative changes and LBP. MRI studies by Borenstein et al. [6] demonstrated that the findings on MRI were not predictive of the development of LBP. These reflect the fact that LBP is a difficult problem to investigate. It has a highly variable natural history and is thought to be multifactorial in origin with a broad range of risk factors involved in its cause and course. However, inconsistent findings concerning the association of LBP seemed to be originated from the potential biases related to heterogeneity in selected subjects, radiological findings at baseline, the nature of LBP, cross-sectional observation in nature and so on. Therefore, the aim of this study was to investigate the relationship between LBP at middle age and the newly developed lumbar degenerative changes during a 20-year follow-up using a selected population of asymptomatic young adult Japanese Self Defense Forces (JSDF) male servicemen with normal lumbar radiographs at entry. We also explored the relationship between LBP and lifestyle factors.

Materials and methods

Subjects

For research on incidence of lumbar degenerative change in military personnel approved by JSDF, 90 male young recruits aged from 18 to 20 who enlisted for a certain infantry company were investigated in 1990. Subjects included in this study had no history of LBP, sciatica, or neurogenic claudication. After taking anteroposterior, lateral and bilateral oblique lumbar spine radiographs, subjects were excluded if they had abnormal radiologic findings such as vertebral osteophyte (VOs), disc space narrowing (DSN), spondylolysis, spinal deformity, wedged vertebra, or irregularity of the endplate on plain X-ray. Six subjects, four with L5 spondylolysis and two with scoliosis, were excluded. As a result, 84 JSDF male recruits were selected for entry. In 2010, all 84 subjects were able to participate in this follow-up study. For these subjects, the same radiological examination and postal questionnaires were performed. The letter requested information concerning episodes of LBP, habit of smoking, and alcohol consumption. Height and weight were taken from JSDF health records and BMI was calculated as weight (kg)/height (m2). All variables were expressed as binary outcomes for analysis: current smoker versus non-smoker, alcohol consumption ≥1 day/week versus none, habit of sporting activity ≥1 day/week versus none, weight gain ≥10 kg versus <10 kg. The question concerning LBP did not ask specifically about the etiology of LBP. We asked about the non-specific pain localized between the gluteal folds and the 12th ribs, and LBP was defined as a current pain lasting ≥7 consecutive days experienced during the year prior to this study, according to the report by Hassett et al. [7]. Radiographs of each patient were obtained in the supine position and their findings were assessed by a single trained observer (ON). The incidence of VOs was defined as ≥2 mm in length according to the classification of Macnab et al. [8]. DSN was defined as ≥1/3 decrease of the disc height, compared to that of at entry. A summary grade reported by Lane et al. [9] was assigned to each lumbar spine based on the presence and severity of VOs and DSN: grade 0 = normal, grade 1 = mild, and grade 2 = moderate-severe.

Within-observer variation was assessed by test–retest analysis of 20 randomly selected radiographs from the study. Good within-observer reproducibility (κ = 0.78–0.89) was found.

Statistical method

A univariate analysis of independent variables using Pearson’s Chi-squared test with or without Yates control for qualitative variables, and Mann–Whitney for quantitative variables (5 % was chosen as the level of statistical significance) was performed. The independent variables for analysis were as follows: significant weight gain, habits of smoking, sporting activity or alcohol consumption, and degenerative changes such as DSN or VOs during the intervening 20 years. Variables that were significantly associated with LBP were subsequently included in a multiple logistic regression analysis to determine their independent effects. Statistical analysis was performed by SPSS statistical software package version 11, and statistical significance was assigned to p values <0.05.

Results

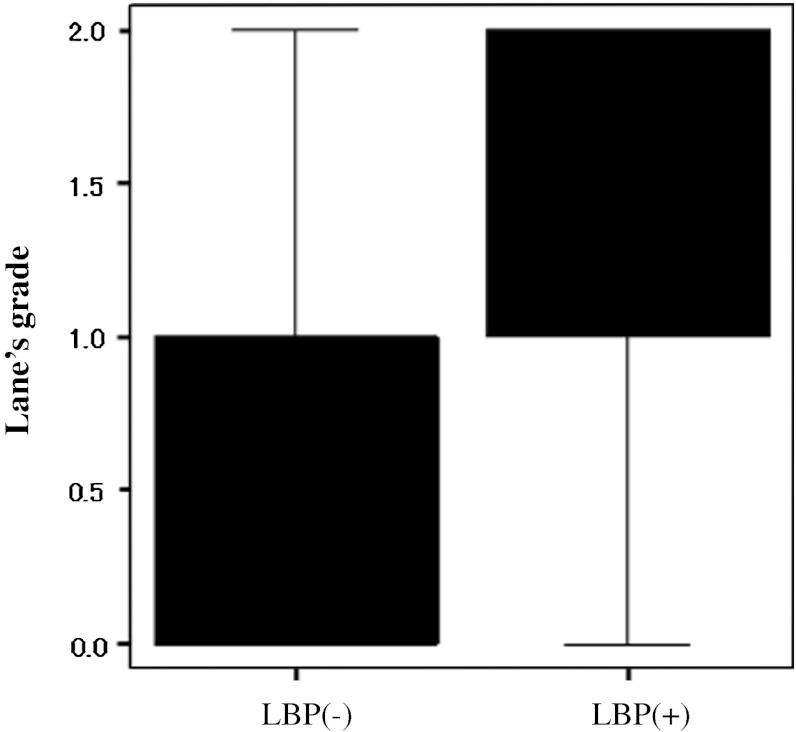

All subjects were noncommissioned officers with similar socioeconomic status and life styles. During the study period, no subjects died and moved from the camp. All subjects replied to written requests for clinical information. Their mean ages were 18.3 ± 0.5 years at entry and 38.5 ± 0.5 years at follow-up. Analysis of the 84 lumbar radiographs made for the 2010 study revealed that 40 (48 %) had normal findings and 44 subjects (52 %) had degenerative changes in the lumbar spine, including 24 subjects (28 %) with grade 1 (mild) and 20 subjects (24 %) with grade 2 (≥moderate). VOs was observed in 39 subjects (46 %), showing the greatest prevalence in L4 followed by L5 and L3 (Fig. 1a). For the type of VOs, claw type VOs were found in 34 subjects and traction type VOs were found in 8 subjects. In five subjects, both types of VOs existed together. In two cases, we had difficulty in distinguishing between claw and traction VOs because of the intermediate appearance. We analyzed the frequency of LBP in subjects with claw type VOs and compared to those with traction type VOs. Subjects with coexistence of both types were excluded. Occurrence of LBP was 62 % in 29 subjects with claw type VOs and 66 % in 3 subjects with traction type VOs without significant statistical difference. DSN was detected in 25 subjects (30 %) and the total number of DSN was increased in the caudal direction (Fig. 1b).

Fig. 1.

a Distribution of vertebral osteophyte. Bar chart showing the total number of osteophytes in different vertebral level. b Distribution of disc space narrowing. Bar chart showing the total number of narrowed disc spaces in different disc level

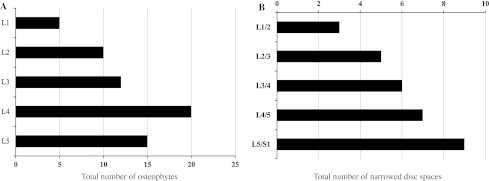

LBP lasting for more than seven consecutive days in the year of 2010 had been experienced by 44 subjects (52 %), but the nature of their LBP was mild and did not affect the ability to perform military services. According to their LBP, two groups were identified: those with LBP and those without. The association between LBP and lifestyle factors or radiological parameters was investigated. With regard to age, height and body weight, there was no significant difference between the two groups both at the 1990 (Table 1a) and the 2010 study (Table 1b). Univariate analysis showed that none of lifestyle factors was significantly associated with LBP (Table 2). The analysis of the degenerative changes estimated by Lane’s grade revealed the significantly greater score in LBP group than in the group without LBP, demonstrating that degenerative change was more prevalent in the subjects with LBP (Fig. 2). In order to assess which radiological parameter is strongly associated with LBP, univariate analysis was performed. As a result, VOs demonstrated a significant association with LBP (OR 3.00; 95 % CI 1.23–7.33), although DSN showed a trend toward association with LBP (Table 3). Multiple logistic regression analysis also confirmed the significant association between VOs and LBP. Table 4 shows the prevalence rate of the VOs at different vertebral levels. Although there was no statistically significant association, LBP group showed the greater prevalence rate of VOs in each vertebral level compared to the subjects without LBP (Table 4), while there was no significant difference in the prevalence rate of DSN by disc level between the subjects with LBP and those without.

Table 1.

Demographic data of 84 subjects with or without LBP

| Subjects with LBP (n = 44) | Subjects without LBP (n = 40) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| (a) At 1990 | |||

| Age | 18.3 ± 0.5 | 18.4 ± 0.5 | 0.352 |

| Height (cm) | 172.8 ± 4.8 | 171.1 ± 4.7 | 0.116 |

| Weight (kg) | 68.2 ± 8.2 | 67.4 ± 7.0 | 0.677 |

| (b) At 2010 | |||

| Age | 38.6 ± 0.5 | 38.4 ± 0.5 | 0.160 |

| Height (cm) | 171.3 ± 5.1 | 170.7 ± 3.9 | 0.281 |

| Weight (kg) | 74.5 ± 10.9 | 73.3 ± 9.6 | 0.618 |

Values are expressed as mean ± SD

Table 2.

Unadjusted odds ratio for various factors related to LBP

| No. of subjects (%) | OR (95 % CI) | p value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LBP(+) (n = 44) | LBP(−) (n = 40) | |||

| Sports | 24 (54) | 27 (67) | 0.578 (0.238–1.405) | 0.225 |

| Smoking | 19 (43) | 15 (38) | 1.267 (0.528–3.039) | 0.596 |

| Alcohol | 27 (61) | 29 (73) | 0.602 (0.240–1.515) | 0.280 |

| Weight gain | 13 (29) | 11 (27) | 1.086 (0.329–3.580) | 0.893 |

Fig. 2.

Score of the Lane’s grade. Box whiskerplot shows the upper and lower quartiles (box), and the maximum and minimum values (whiskers). Median value of the score is compared between subjects with LBP and those without

Table 3.

Unadjusted odds ratio for various factors related to LBP

| No. of subjects (%) | OR (95 % CI) | p value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LBP(+) (n = 44) | LBP(−) (n = 40) | |||

| VOs | 26 (59) | 13 (32) | 3.000 (1.227–7.333) | 0.013 |

| DSN | 14 (32) | 11 (27) | 1.230 (0.480–3.150) | 0.666 |

Table 4.

Prevalence rate of vertebral osteophyte related to LBP by vertebral level

| No. of subjects (%) | p value | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| LBP(+) (n = 44) | LBP(−) (n = 40) | ||

| L1 | 4 (9) | 1 (3) | 0.202 |

| L2 | 6 (14) | 4 (10) | 0.607 |

| L3 | 8 (18) | 4 (10) | 0.285 |

| L4 | 11 (25) | 9 (23) | 0.807 |

| L5 | 10 (23) | 5 (13) | 0.222 |

Discussion and conclusion

A number of studies on different athletes and heavy physical workers have reported high but variable rate of degenerative changes in the lumbar spine [10, 11]. This study also showed a high prevalence rate of degenerative changes, even though the subjects were middle aged military personnel. Accumulations of vertical stress on lumbar spine in ordinary physical stress in military basic training might be contributing factors. Compared with the high prevalence of radiological abnormalities, intensity of current LBP was mild, not disrupting their military jobs, although 52 % of the subjects reported LBP. Lundin et al. [12] showed in the analysis of LBP and radiological abnormalities among athletes that regular participation in exercise and sports was associated with less back pain, despite an increase in degenerative disc changes. This finding is similar to that of military personnel in the present study. The cause remains speculative, but there is a possibility that during their training, military personnel gain a higher tolerance for pain, as proposed by Granhed et al. [11]. With regard to the association of LBP with physical characteristics or lifestyle factors, literature reviews provide conflicting views. Review of the literature by Leboeuf-Yde et al. [13] reveals that smoking should be considered as a weak risk indicator and not as a cause of LBP. For the link between obesity or weight gain and LBP, the increased mechanical demands resulting from these factors have been suspected of causing LBP through excessive wear and tear. However, a closer examination of the literature also reveals some confusion [14]. Excessive alcohol consumption is another prevalent lifestyle factor that is generally known to contribute to certain diseases, such as cardiovascular disease and disorders of the liver. A review of the literature reveals that alcohol in relation to LBP has not evoked the same amount of interest as smoking and obesity in relation to LBP [15]. We found no significant associations of these factors with LBP. With a larger sample size, some factors may well prove to be significant contributors to LBP development.

The relation between radiological abnormalities in the lumbar spine and LBP has been published in a number of reports. In a cross-sectional study, Kellgren and Lawrence [16] found some association between radiological changes and past LBP. Frymoyer [17], on the other hand, concluded that single DSN and VOs were equally prevalent in symptomatic and asymptomatic men. In the analysis of athletes of different sports, Lundin et al. [12] found no correlation between LBP and any specific radiological abnormalities; however, they demonstrated a significant correlation between LBP and a decrease in disc height during a 13-year follow-up period. Thus, the relation between radiological abnormalities in lumbar spine and LBP has been debated. However, recent large scale epidemiological studies reported lumbar degenerative changes as main risk factors for LBP. The cross-sectional study of 2,256 twin pairs with a mean age of 50 years by Livshits et al. [18] revealed that lumbar disc degeneration and being overweight were highly significantly associated with non-specific LBP. Cheung et al. [19] also demonstrated in a cross-sectional population study of MRI obtained in 1,043 volunteers that there is a significant association of lumbar disc degeneration with LBP. In addition, recent research may suggest that LBP and lumbar degenerative change are governed by some common genetic factors, the nature of which remains to be determined [20]. Although DSN showed a trend toward association without a statistical significance, the present results are in good agreement with published data, including a previous study by O’Neill et al. [21] suggesting an association between LBP and VOs, particularly in men. The cause for positive association between LBP and VOs in this small scale study is not known, but homogeneity in life style, working environment and socio-economic circumstances of the subjects and longitudinal observation in nature may contribute to the results. Assessment of radiographic DSN is difficult and has not proved to be very reliable. Accordingly, careful comparison of the films at both entry and follow-up was performed to have as good internal validity as possible. However, positive significant association between LBP and DSN was not obtained in this study. From these facts, it seems plausible to infer that the detected differences between the two radiological parameters reflect differences in their pathophysiology, although further research is necessary to determine.

As with any study, this study has several weak points that may limit potential generalization of the results. Greatest weakness lies that we retrospectively reviewed the prospective database. If osteophytes >2 mm were admitted in certain number of the subjects at entry and followed up to the middle age to observe the development of LBP, this study would be a definite prospective cohort study with no doubt. However, osteophytes >2 mm were not admitted except for the excluded subjects with L5 spondylolysis. This may have originated from the age of the subjects and the unique design of this study, in that the heterogeneity of radiological findings at entry was excluded, since inconsistent findings concerning the association between LBP and radiological abnormalities in reported studies seemed to be related to heterogeneous radiological findings at baseline. So, we would like to regard this study as a retrospective longitudinal study. The small sample size and the rather weak power is another problem. Given the complexity of the initial and repeated X-ray after 20 years, it was not easy to include more subjects in this trial. Other drawbacks were not including females, a limited subject pool of military personnel, and a restricted radiological analysis using plain X-ray. Therefore, we are planning to conduct a similar study targeting the general population including female by MRI as well as plain X-ray.

Despite the aforementioned limitations, this is the first study to investigate the development of lumbar degenerative changes with such a longitudinal design using asymptomatic young adult without radiological abnormalities at baseline.

In conclusion, this small sample, but a long follow-up, study showed that current mild LBP is significantly associated with the developed VOs.

Acknowledgments

The authors did not receive any outside funding or grants in support of their research for or preparation for this work. Neither they nor a member of their immediate families received payments or other benefits or a commitment or agreement to provide such benefits from a commercial entity. No commercial entity paid or directed, or agreed to pay or direct, any benefits to any research fund, foundation, division, center, clinical practice, or other charitable or non-profit organization with which the authors, or a member of their immediate families, are affiliated or associated.

Conflict of interest

None.

References

- 1.Harreby M, Neergaard K, Hesselsoe G, Kjer J. Are radiologic changes in the thoracic and lumbar spine of adolescents risk factors for low back pain in adults? Spine. 1995;20(21):2298–2302. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199511000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mattila VM, Sillanpaa P, Visuri T, Pihlajamaki H (2008) Incidence and trends of low back pain hospitalization during military service- An analysis of 387070 Finnish young males. BMC Musculoskeletal Disord 10:10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Mattila VM, Sahi T, Jormanainen V, Pihlajamaki H. Low back pain and its risk indicators: a survey of 7040 Finnish male conscripts. Eur Spine J. 2008;17(1):64–69. doi: 10.1007/s00586-007-0493-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Torgerson WR, Dotter WE. Comparative roentogenographic study of the asymptomatic and symptomatic lumbar spine. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1976;58(6):850–853. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hult (1954) Cervical, dorsal and lumbar spinal syndromes. Acta Orthop Scandinavica 17:1–102 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Borenstein DG, O’Mara JW, Boden SD, Lauerman WC, Jacobson A, Platenberg C, Schellinger D, Wiesel SW. The value of magnetic resonance imaging of the lumbar spine to predict low back pain in asymptomatic subjects. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2001;83(9):1306–1311. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200109000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hassette G, Hart DJ, Manek NJ, Doyle DV, Spector TD. Risk factors for progression of lumbar spine disc degeneration. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;48(11):3112–3117. doi: 10.1002/art.11321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Macnab I (1971) The traction spur. An indicator of segmental instability. J Bone Joint Surg Am 53(4):663–670 [PubMed]

- 9.Lane NY, Nevitt MC, Genant H, Hochberg MC. Reliability of new indices of radiographic osteoarthritis of the hand and hip lumbar disc degeneration. J Rheumatol. 1993;20(11):1911–1918. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schmitt H, Dubljanin E, Schneider S. Radiographic changes in the lumbar spine in former elite athletes. Spine. 2004;29(22):2554–2559. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000145606.68189.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Granhed H, Morelli B. Low back pain among retired wrestlers and heavyweight lifters. Am J Sports Med. 1988;16(5):530–533. doi: 10.1177/036354658801600517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lundin O, Hellstrom M, Nilsson I, Sward L. Back pain and radiological changes in the thoraco-lumbar spine of athletes. A long-term follow up. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2001;11(2):103–109. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0838.2001.011002103.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Leboeuf-Yde C. Smoking and low back pain. A systematic literature review of 41 journal articles reporting 47 epidemiologic studies. Spine. 1999;24(14):1463–1470. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199907150-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Leboeuf-Yde C. Body weight and low back pain. A systematic literature review of 56 journal articles reporting 65 epidemiologic studies. Spine. 2000;25(2):226–237. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200001150-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Leboeuf-Yde C. Alcohol and low back pain: a systematic literature review. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2000;23(5):343–346. doi: 10.1067/mmt.2000.106866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kellgren JH, Lawrence JS. Osteoarthrosis and disc degeneration in an urban population. Ann Rheum Dis. 1958;17:388–396. doi: 10.1136/ard.17.4.388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Frymoyer JW, Newberg A, Pope MH, Wilder DG, Clements J, MacPherson B (1984) Spine radiographs in patients with low back pain. J Bone Joint Surg 66-A(7):1048–1054 [PubMed]

- 18.Livshits G, Popham M, Malkin I, Sambrook PN, MacGregor AJ, Spector T, Williams FM. Lumbar disc degeneration and genetic factors are the main risk factors for low back pain in women: the UK twin spine study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011;70:1740–1745. doi: 10.1136/ard.2010.137836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cheung KM, Karppinen J, Chan D, Ho DW, Song YQ, Sham P, Cheah KS, Leong JC, Luk KD. Prevalence and pattern of lumbar magnetic resonance imaging changes in a population study of the one thousand forty-three individuals. Spine. 2009;34(9):934–940. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181a01b3f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu J, Pei Y, Papasian CJ, Deng HW. Bivariate association analyses for the mixture of continuous and binary traits with the use of extended generalized estimating equations. Genet Epidemiol. 2009;33:217–227. doi: 10.1002/gepi.20372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.O’Neill TW, McCloskey EV, Kanis JA, Bhalla AK, Reeve J, Reid DM, Todd C, Woolf AD, Silman AJ. The distribution, determinants, and clinical correlates of vertebral osteophytosis: a population based survey. J Rheumatol. 1999;26(4):842–848. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]