Abstract

BACKGROUND

Despite ongoing efforts to improve the quality of pediatric resuscitation, it remains unknown whether survival in children with in-hospital cardiac arrest has improved.

METHODS & RESULTS

Between 2000 and 2009, we identified children (<18 years) with an in-hospital cardiac arrest at hospitals with ≥ 3 years of participation and ≥ 5 cases annually within the national Get With The Guidelines-Resuscitation registry. Multivariable logistic regression was used to examine temporal trends in survival to discharge. We also explored whether trends in survival were due to improvement in acute resuscitation or post-resuscitation care and examined trends in neurological disability among survivors. Among 1031 children at 12 hospitals, the initial cardiac arrest rhythm was asystole and pulseless electrical activity in 874 children (84.8%) and ventricular fibrillation and pulseless ventricular tachycardia in 157 children (15.2%), with an increase in cardiac arrests due to asystole and pulseless electrical activity over time (P for trend <0.001). Risk-adjusted rates of survival to discharge increased from 14.3% in 2000 to 43.4% in 2009 (adjusted rate ratio per 1-year 1.08; 95% CI [1.01,1.16]; P for trend 0.02). Improvement in survival was largely driven by an improvement in acute resuscitation survival (risk adjusted rates: 42.9% in 2000, 81.2% in 2009; adjusted rate ratio per 1-year: 1.04; 95% CI [1.01,1.08]; P for trend 0.006). Moreover, survival trends were not accompanied by higher rates of neurological disability among survivors over time (unadjusted P for trend 0.32), suggesting an overall increase in the number of survivors without neurological disability over time.

CONCLUSION

Rates of survival to hospital discharge in children with in-hospital cardiac arrests have improved over the past decade without higher rates of neurological disability among survivors.

Keywords: cardiopulmonary resuscitation, pediatrics, survival

INTRODUCTION

In-hospital cardiac arrest in children occurs in 2% to 6% of all pediatric intensive care unit patients1, 2 and is associated with poor survival.3 Over the past decade, various strategies have been promoted by clinical practice guidelines to improve survival after in-hospital cardiac arrests. These include earlier recognition and management of at-risk patients, greater emphasis on quality of resuscitation (e.g., high-quality chest compressions with minimal interruptions, use of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation during resuscitation [ECPR]) and post-resuscitation care (e.g., multidisciplinary care).4–7

Despite increased emphasis on these initiatives, no study has yet examined temporal trends in survival for pediatric in-hospital cardiac arrests. This is, in part, due to the lack of a national pediatric cardiac arrest registry with standardized definitions and uniform data reporting. Although indirect comparisons across single-center studies may suggest that cardiac arrest survival in hospitalized children has improved from 9% in the 1980s8, 9 to 27% in 2005,3 these comparisons do not account for important differences across centers or in patient characteristics over time (e.g., age, co-morbid conditions, etiology of cardiac arrest, or initial rhythm). For example, advances in the management of children with complex congenital heart diseases may have resulted in a temporal decrease in the proportion of cardiac arrests due to ventricular fibrillation (VF) and pulseless ventricular tachycardia (VT) rhythms - which are associated with better survival than asystole or pulseless electrical activity (PEA). Furthermore, survivors of a cardiac arrest are at significant risk of neurological impairment and it is unknown whether any improvement in survival in this population has occurred at the cost of higher rates of neurological disability.

To address these existing gaps in knowledge, we examined trends in survival and neurological disability in children with an in-hospital cardiac arrest using data from a large, national, hospital-based clinical registry. A better understanding of trends in survival after pediatric in-hospital cardiac arrest would provide an informed assessment of ongoing quality improvement efforts in pediatric cardiopulmonary resuscitation and lay the foundation for monitoring future improvements in care.

METHODS

Data Source and Study Population

Our study patients were derived from Get With The Guidelines-Resuscitation (GWTG-Resuscitation), formerly known as the National Registry of Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation. This is a large, hospital-based, clinical registry of in-hospital cardiac arrests that has been enrolling patients since January 2000. Its design has been previously described in detail.10 Briefly, the registry enrolls patients with a pulseless cardiac arrest, defined as the absence of a palpable central pulse, apnea, and unresponsiveness in children without Do-Not-Resuscitate (DNR) orders in whom a resuscitation effort is attempted. Although data on children who received cardiopulmonary resuscitation for bradycardia and hypotension are also collected, these were not included, as they did not meet our study definition of cardiac arrest.

To ensure that consecutive cardiac arrest patients are enrolled, multiple case-finding methods are used. These include centralized collection of cardiac arrest flow sheets, review of hospital page system logs, and routine checks of code carts, pharmacy tracer drug records, and hospital billing charges for use of resuscitation medications. The registry uses Utstein-style definitions, which are a standardized template of reporting guidelines developed by international experts, for defining clinical variables and outcomes.11 Data completeness and accuracy in GWTG-Resuscitation is ensured by rigorous training and certification of study personnel, a periodic re-abstraction process and use of standardized software with internal data checks. The American Heart Association oversees the entire process of data collection, analysis, and reporting through its national center staff, clinical working group, and executive database steering committee.

Study Population

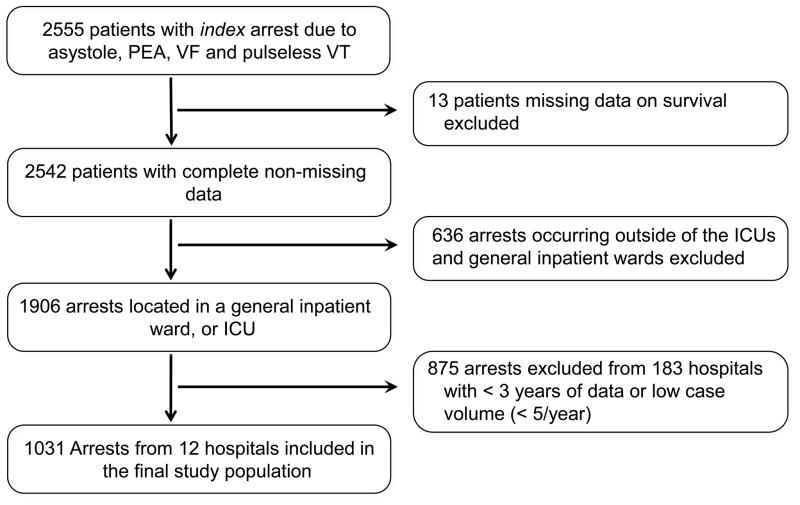

Between January 1, 2000 and November 19, 2009, we identified 2555 patients who were younger than 18 years of age with an index in-hospital cardiac arrest (Figure 1). We excluded 13 patients with missing information on survival. We also restricted our sample to cardiac arrests occurring in inpatient locations (e.g., intensive care units including pediatric and neonatal units, inpatient wards, labor & delivery) and excluded cardiac arrest patients from emergency departments, operating rooms, and procedural suites, due to the distinct clinical circumstances and outcomes with cardiac arrest in these locations (n=636). Since we were interested in examining trends in survival over time, we also excluded 875 patients from 183 hospitals with fewer than 3 years of data submission or low cardiac arrest volume (<5 cases per year). Our final sample was comprised of 1031 patients from 12 hospitals.

Figure 1.

Study Cohort

Study Outcome Measures

The primary outcome was survival to discharge. To better understand which specific phase of resuscitation care was associated with temporal improvement in survival, we also examined, as secondary outcomes, 1) acute resuscitation survival, defined as return of spontaneous circulation for at least 20 minutes after the initial pulseless arrest and 2) post-resuscitation survival, defined as survival to hospital discharge among patients who survived the acute resuscitation. Finally, to confirm that any temporal trend in survival was clinically important, we also examined rates of significant neurological disability among survivors. This was done using previously developed pediatric cerebral performance category (PCPC) scores.12 A PCPC score of 1 describes children with normal age-appropriate neuro-developmental functioning; 2 for mild cerebral disability; 3 for moderate disability; 4 for severe disability; 5 for coma/vegetative state, and 6 for brain death. For our study, we defined significant neurological disability as a PCPC score of 4 or higher among survivors.13

Study Variables

The main independent variable was calendar year. Patient factors included demographics (age groups [< 1 month, 1 month to 5 years, ≥ 5 years], sex, race [white, black, other]), initial cardiac arrest rhythm [asystole, PEA, VF, pulseless VT], co-morbidities or medical conditions present prior to the cardiac arrest (congestive heart failure; diabetes; renal, hepatic, or respiratory insufficiency; pneumonia; hypotension; arrhythmia; sepsis; major trauma; metabolic or electrolyte abnormality; metastatic or hematologic malignancy, pre-arrest PCPC score; baseline motor, cognitive, or functional deficits [CNS depression]; acute stroke; acute non-stroke neurological disorder); therapeutic interventions in place prior to the arrest (mechanical ventilation, anti-arrhythmic drugs, vasopressors, dialysis or extracorporeal filtration) and cardiac arrest characteristics (use of ECPR, hospital location [intensive care unit, monitored, non-monitored]; time [work hours: 7am to 10:59pm vs. after hours: 11pm to 6:59am] and day [weekday vs. weekend] of cardiac arrest); and use of a hospital-wide cardio-pulmonary arrest alert. Finally, as hospitals began participation in the registry at different years, we adjusted for the numerical year of hospital participation (e.g., first, second, etc) for each arrest to confirm that any observed calendar year trend was independent of the duration of hospital participation in the registry.

Statistical Analyses

We evaluated changes in baseline characteristics by calendar year using Mantel-Haenszel test of trend for categorical variables and linear regression for continuous variables. To assess whether survival to discharge has improved over time, we determined risk-adjusted rates of survival for each calendar year. To accomplish this, we constructed multivariable logistic regression models using generalized estimation equations (GEE) with an exchangeable correlation matrix, to account for clustering of patients within hospitals. As survival rates exceeded 10%, we estimated rate ratios (RR) with modified Poisson regression with robust variance estimates at all steps.14, 15 Our independent variable, calendar year, was included in the model as a categorical variable, with year 2000 as the reference year. To derive risk-adjusted rates of survival, we then multiplied the adjusted rate ratios for each subsequent year (2001 through 2009) with the survival rate of the reference year (2000). We also evaluated calendar year as a continuous variable in the model to obtain adjusted RRs for year-over-year survival trends.

Variables for model inclusion were selected based on clinical and statistical criteria. All variables with a significant unadjusted association with the outcome (p < 0.10) were included in the models, as well as the following variables chosen a priori regardless of statistical significance: age, sex, race, hospital location of arrest, initial cardiac arrest rhythm, and numerical year of hospital participation. Similarly, we constructed multivariable models using the approach above for the secondary end points of acute resuscitation and post-resuscitation survival. We also examined whether survival trends were similar within important patient subgroups (age groups, sex, and whether initial rhythm was treatable by defibrillation or not) by including an interaction term with calendar year. Finally, we explored whether use of ECPR was a mediator of improved survival trends over time by comparing the adjusted rate ratios for calendar year derived from models which included and excluded ECPR as a variable. These analyses were performed separately for overall survival, acute resuscitation survival and post resuscitation survival.

Overall rates of missing data were low, except for pre-arrest PCPC scores (missing in 19.8%). These data were assumed to be missing at random and were imputed using multiple imputation with IVEWARE software.16 Results with and without imputation were not meaningfully different, so only the former are presented. All statistical analyses were conducted using SAS Version 9.1.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC), IVEWARE (University of Michigan, MI), and R Version 2.6.0 (Free Software Foundation, Boston, MA). All tests for statistical significance were 2-tailed and were evaluated at a significance level of 0.05. The Institutional Review Board at the University of Iowa waived the requirement for informed consent.

RESULTS

Our study included 1031 pediatric in-hospital cardiac arrests from 12 hospitals. Of the participating hospitals, all were urban teaching hospitals with a pediatric residency or fellowship program (Supplemental Table 1).

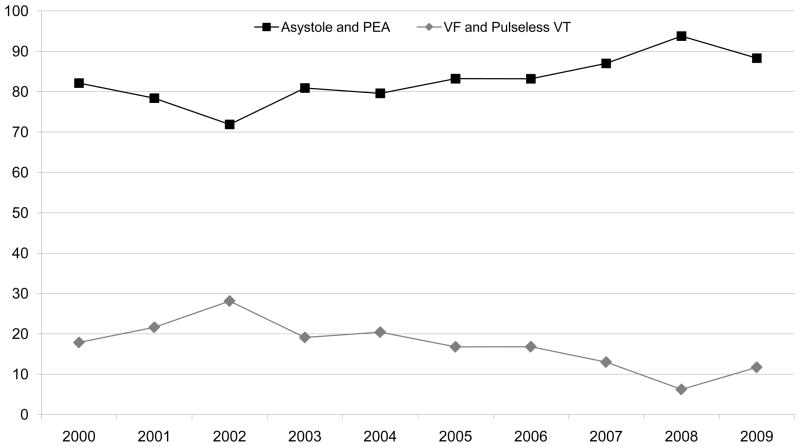

The initial cardiac arrest rhythm was asystole or PEA in 874 children (84.8%) and VF or pulseless VT in 157 children (15.2%). Table 1 shows trends in patient characteristics over time. The proportion of cardiac arrests due to PEA increased from 26.6% during 2000–2003 to 70.3% from 2007–2009, resulting in an overall increase in the proportion of cardiac arrests due to non-shockable rhythms over time (P for trend <0.001, Figure 2). The proportion of the study cohort who were newborns increased over time, whereas the proportion of children ≥ 5 years of age decreased (Table 1, P for trend <0.001). There was also a decrease over time in patients with baseline depression in neurological status, an acute non-stroke neurological event, respiratory insufficiency and pre-existing or concurrent heart failure (P for trend <0.001 for all). In contrast, the proportion of patients with an arrest in an intensive care unit, on mechanical ventilation or receiving intravenous vasoactive agents at the time of cardiac arrest increased over time (P for trend <0.05 for all).

Table 1. Trends in Baseline Characteristics in Children with In-hospital Cardiac Arrest.

For illustrative purposes, trends in baseline characteristics are presented as 3 time periods. The P for trend is for temporal changes in patient characteristics by each calendar year.

| Year Groups | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2000–2003 n = 218 | 2004–2006 n = 372. | 2007–2009 n = 441 | P for Trend | |

| Demographics | ||||

| Age Groups | < 0.001 | |||

| Infant (< 1 month) | 39 (17.9%) | 110 (29.6%) | 182 (41.3%) | |

| Toddler (1 month to <5 years) | 100 (45.9%) | 157 (42.2%) | 171 (38.8%) | |

| Children (≥ 5 years) | 79 (36.2%) | 105 (28.2%) | 88 (20.0%) | |

| Male Sex, % | 119 (54.6%) | 206 (55.4%) | 259 (58.7%) | 0.31 |

| Black Race, % | 41 (21.2%) | 79 (23.2%) | 88 (23.0%) | 0.04 |

| Arrest Characteristics, % | ||||

| Initial Cardiac Arrest Rhythm | 0.02 | |||

| Asystole | 112 (51.4%) | 140 (37.6%) | 88 (20.0%) | |

| Pulseless Electrical Activity | 58 (26.6%) | 166 (44.6%) | 310 (70.3%) | |

| Ventricular Fibrillation | 29 (13.3%) | 36 (9.7%) | 19 (4.3%) | |

| Pulseless Ventricular Tachycardia | 19 (8.7%) | 30 (8.1%) | 24 (5.4%) | |

| Arrest at Night (11pm to 7am) | 70 (32.1%) | 116 (31.3%) | 131 (29.8%) | 0.34 |

| Arrest on Weekend | 67 (30.7%) | 136 (36.6%) | 131 (29.7%) | 0.70 |

| ECPR | 17 (8.1%) | 28 (7.7%) | 63 (14.3%) | 0.004 |

| Hospital Location of Arrest | 0.001 | |||

| Intensive Care Unit | 188 (86.2%) | 344 (92.5%) | 417 (94.6%) | |

| Monitored unit | 10 (4.6%) | 10 (2.7%) | 12 (2.7%) | |

| Non-monitored unit | 20 (9.2%) | 18 (4.8%) | 12 (2.7%) | |

| PCPC Category on Admission | 0.013 | |||

| 1 | 98 (53.8%) | 160 (53.5%) | 175 (50.6%) | |

| 2 | 22 (12.1%) | 33 (11.0%) | 36 (10.4%) | |

| 3 | 20 (11.0%) | 35 (11.7%) | 24 (6.9%) | |

| 4 or higher | 42 (23.1%) | 71 (23.7%) | 111 (32.1%) | |

| Hospital-wide response activated | 34 (15.6%) | 44 (11.8%) | 32 (7.3%) | 0.003 |

| Pre-Existing Conditions, % | ||||

| Heart Failure this admission | 73 (33.5%) | 93 (25.0%) | 36 (8.2%) | < 0.001 |

| Prior Heart Failure | 51 (23.4%) | 70 (18.8%) | 22 (5.0%) | < 0.001 |

| Arrhythmia | 48 (22.0%) | 107 (28.8%) | 122 (27.7%) | 0.22 |

| Hypotension | 90 (41.3%) | 188 (50.5%) | 220 (49.9%) | 0.08 |

| Respiratory Insufficiency | 150 (68.8%) | 263 (70.7%) | 333 (75.5%) | 0.01 |

| Renal Insufficiency | 30 (13.8%) | 50 (13.4%) | 47 (10.7%) | 0.12 |

| Hepatic Insufficiency | 17 (7.8%) | 22 (5.9%) | 22 (5.0%) | 0.13 |

| Metabolic or Electrolyte Abnormality | 46 (21.1%) | 86 (23.1%) | 116 (26.3%) | 0.19 |

| Diabetes Mellitus | 2 (0.9%) | 5 (1.3%) | 2 (0.5%) | 0.36 |

| Baseline Depression in CNS Function | 48 (22.0%) | 66 (17.7%) | 48 (10.9%) | < 0.001 |

| Acute Stroke | 3 (1.4%) | 9 (2.4%) | 5 (1.1%) | 0.51 |

| Acute Non-Stroke CNS event | 32 (14.7%) | 33 (8.9%) | 29 (6.6%) | 0.007 |

| Pneumonia | 27 (12.4%) | 31 (8.3%) | 34 (7.7%) | 0.07 |

| Septicemia | 28 (12.8%) | 68 (18.3%) | 64 (14.5%) | 0.80 |

| Major Trauma | 14 (6.4%) | 27 (7.3%) | 25 (5.7%) | 0.69 |

| Metastatic or Hematologic Malignancy | 12 (5.5%) | 21 (5.6%) | 23 (5.2%) | 0.35 |

| Interventions in Place Prior to the Arrest, | ||||

| Mechanical Ventilation | 147 (67.4%) | 281 (75.5%) | 360 (81.6%) | < 0.001 |

| Intravenous Antiarrhythmic Therapy | 10 (4.6%) | 23 (6.2%) | 29 (6.6%) | 0.34 |

| Intravenous Vasopressor Medication | 114 (52.3%) | 180 (48.4%) | 262 (59.4%) | 0.02 |

| Dialysis/Extracorporeal Filtration | 10 (4.6%) | 24 (6.5%) | 22 (5.0%) | 0.94 |

Abbreviations: CNS, central nervous system; ECPR, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation during cardiopulmonary resuscitation; PCPC, pediatric cerebral performance category

Figure 2. Proportion of Cardiac Arrests Due to Asystole or Pulseless Electrical Activity (PEA) and Ventricular Fibrillation (VF) or Pulseless Ventricular Tachycardia (VT) By Calendar Year.

Over the past decade, the proportion of cardiac arrests treatable by defibrillation (VF and pulseless VT) has decreased (P for trend <0.001).

Survival to Discharge

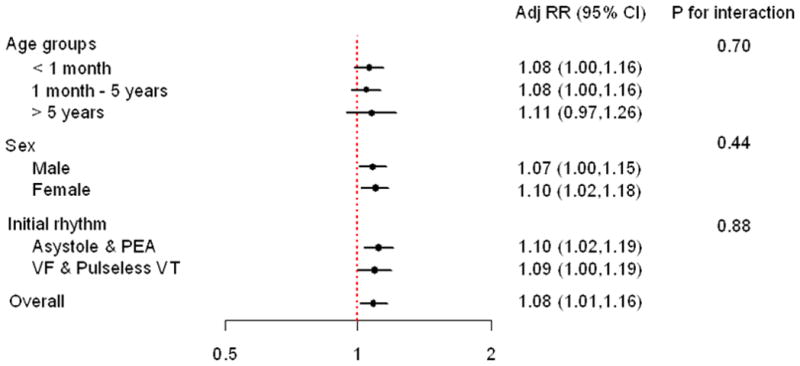

During the study period, 359 (34.8%) children with in-hospital cardiac arrest survived to hospital discharge, with an increase in the unadjusted survival rate over time in the overall cohort (Table 2) and by initial rhythm (Table 3). After adjusting for differences in patient characteristics, we found a significant improvement in overall survival to discharge (risk-adjusted rates: 14.3% in 2000, 43.4% in 2009; adjusted rate ratio per 1-year 1.08; 95% CI [1.01, 1.16]; P for trend 0.02, Table 4). Temporal trends in survival were similar between age groups (< 1 month, 1 month-5 years, ≥ 5 years), as well as by sex (male vs. female) and initial cardiac arrest rhythm (VF and pulseless VT vs. asystole and PEA) (P for all interactions > 0.40; Figure 3 and Supplemental Table 2). Notably, duration of hospital participation in the registry was not significantly associated with overall survival (P=0.36, Supplemental Table 3).

Table 2. Observed (Unadjusted) Rates of Survival Outcomes and Neurological Disability by Calendar Year.

Unadjusted rates for survival to discharge, acute resuscitation survival, post-resuscitation survival and significant neurological disability are reported for the overall cohort by calendar year.

| 2000 N=28 |

2001 N=37 |

2002 N=64 |

2003 N=89 |

2004 N=98 |

2005 N=149 |

2006 N=125 |

2007 N=154 |

2008 N=193 |

2009 N=94 |

P for Trend | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Survival to Discharge, % (n) | 14.3 (4) | 24.3 (9) | 34.4 (22) | 30.3 (27) | 29.6 (29) | 23.5 (35) | 44.0 (55) | 41.6 (64) | 39.9 (77) | 39.4 (37) | <0.001 |

| Acute Resuscitation Survival,†% (n) | 42.9 (12) | 62.2 (23) | 70.3 (45) | 55.1 (49) | 71.4 (70) | 62.4 (93) | 77.6 (97) | 74.7 (115) | 77.7 (150) | 77.7 (73) | <0.001 |

| Post-Resuscitation Survival,‡ % (n) | 33.3 (4) | 39.1 (9) | 48.9 (22) | 55.1 (27) | 41.4 (29) | 37.6 (35) | 56.7 (55) | 55.7 (64) | 51.3 (77) | 50.7 (37) | 0.04 |

| Significant Neurological Disability,§ % (n/survivors) | 0 (0/3) | 0 (0/8) | 12.5 (2/16) | 17.4 (4/23) | 4.4 (1/23) | 12.0 (3/25) | 16.0 (8/50) | 13.2 (7/53) | 9.2 (6/65) | 21.9 (7/32) | 0.32 |

Acute Resuscitation Survival was determined by the number of patients with return of spontaneous circulation for at least 20 minutes divided by the number of patients with a cardiac arrest.

Post-resuscitation Survival was determined by the number of patients with acute resuscitation survival who survived to hospital discharge divided by the number surviving the acute resuscitation.

Neurological Disability in Survivors. Neurological Disability was defined as the proportion of patients surviving to hospital discharge with a PCPC Score of > 3 (i.e., at least severe neurological disability). Discharge PCPC scores were missing in 17% of survivors

Table 3. Rhythm-Specific Rates of Unadjusted Survival to Discharge by Calendar Year.

Unadjusted rates for survival to discharge are reported separately for patients with asystole, pulseless electrical activity, and ventricular fibrillation & pulseless ventricular tachycardia by calendar year.

| 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | P for Trend | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Asystole, % (n/N) | 20.0 (3/15) | 38.1 (8/21) | 21.2 (7/33) | 23.3 (10/43) | 20.5 (8/39) | 20.6 (13/63) | 47.4 (18/38) | 45.0 (18/40) | 31.3 (10/32) | 31.3 (5/16) | 0.05 |

| PEA, % (n/N) | 12.5 (1/8) | 12.5 (1/8) | 46.5 (6/13) | 34.5 (10/29) | 33.3 (13/39) | 26.2 (16/61) | 39.4 (26/66) | 39.4 (37/94) | 40.9 (61/149) | 41.8 (28/67) | 0.03 |

| VF & Pulseless VT, % (n/N) | 0 (0/5) | 0 (0/8) | 50.0 (9/18) | 41.2 (7/17) | 40.0 (8/20) | 24.0 (6/25) | 52.4 (11/21) | 45.0 (9/20) | 50.0 (6/12) | 36.4 (4/11) | 0.11 |

Abbreviations: PEA, pulseless electrical activity; VF, ventricular fibrillation; VT, ventricular tachycardia

Table 4. Risk-Adjusted Rates of Survival Outcomes by Calendar Year.

Risk-adjusted rates* and adjusted rate ratios per 1-year for the study outcomes of survival to discharge, acute resuscitation survival, and post-resuscitation survival are reported for the overall cohort by calendar year.

| 2000 N=28 |

2001 N=37 |

2002 N=64 |

2003 N=89 |

2004 N=98 |

2005 N=149 |

2006 N=125 |

2007 N=154 |

2008 N=193 |

2009 N=94 |

Adjusted RR per 1-year (95% CI) | P for Trend | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Survival to Discharge, % | 14.3 | 22.5 | 37.9 | 31.0 | 30.8 | 24.3 | 44.5 | 42.0 | 42.1 | 43.4 | 1.08 [1.01, 1.16] | 0.02 |

| Acute Resuscitation Survival,† % | 42.9 | 64.3 | 74.9 | 55.6 | 72.3 | 63.3 | 79.7 | 74.6 | 80.3 | 81.2 | 1.04 [1.01, 1.07] | 0.006 |

| Post-Resuscitation Survival,‡ % | 33.3 | 36.3 | 49.8 | 53.1 | 42.4 | 38.9 | 56.4 | 56.7 | 52.5 | 53.6 | 1.04 [0.98, 1.09] | 0.17 |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; RR, rate ratio

Risk-adjusted rates for each calendar year were obtained by multiplying the observed rate for the reference year (2000) with the corresponding rate ratios for 2001 through 2009 from a model evaluating calendar year as a categorical variable. Rates are adjusted for age groups, sex, race, initial cardiac arrest rhythm, heart failure this admission, heart failure prior to admission, hypotension/hypoperfusion, respiratory insufficiency, baseline depression in CNS function, acute CNS non-stroke event, pneumonia, assisted/mechanical ventilation, use of vasoactive agents, use of ECPR, hospital location, use of a hospital-wide response, and years of participation in the registry.

Acute Resuscitation Survival was determined by the number of patients with return of spontaneous circulation for at least 20 minutes divided by the number of patients with a cardiac arrest.

Post-resuscitation Survival was determined by the number of patients with acute resuscitation survival who survived to hospital discharge divided by the number surviving the acute resuscitation.

Figure 3. Temporal Trends in Survival in Patient Sub-groups.

Adjusted rate ratio per 1-year for survival to hospital discharge are presented by age groups (<1 month, 1 month to <5 years, ≥ 5 years), sex, and initial cardiac arrest rhythm (asystole and pulseless electrical activity [PEA] vs. ventricular fibrillation [VF] and pulseless ventricular tachycardia [VT]).

Secondary Outcomes

The increase in overall survival over time was accompanied by a significant improvement in acute resuscitation survival, which increased from 42.9% in 2000 to 81.2% in 2009 (adjusted rate ratio per 1-year 1.04; 95% CI [1.01, 1.07]; P for trend 0.006, Table 4). Rates of post-resuscitation survival similarly increased over time (Table 2), but this finding was not significant in adjusted analyses (P for trend 0.17, Table 4). Data on neurological disability was missing in 61 (17%) survivors. Although the number of survivors was small, unadjusted rates of neurological disability did not change significantly during the study period (P for trend 0.32, Table 2).

Use of ECPR

During acute resuscitation, ECPR was used in 108 patients (10.5%); of them 37 (34.3%) survived to hospital discharge. The use of ECPR during resuscitation increased from 8.1% of cases in 2000–2003 to 14.3% in 2007–2009 (P for trend 0.004, Table 1). While use of ECPR was associated with higher acute resuscitation survival (adjusted rate ratio 1.22 [1.13, 1.32], P value <0.001), it was associated with lower post resuscitation survival (adjusted rate ratio 0.80 [0.67, 0.97], P value 0.02). Taken together, use of ECPR was not associated with overall survival to discharge (adjusted risk ratio 0.96 [0.78, 1.19], P value 0.73). Moreover, inclusion of ECPR did not result in a meaningful change in the adjusted rate ratios for calendar year; therefore, higher ECPR use over time was not a mediator of temporal trends in overall survival, acute resuscitation survival or post resuscitation survival (results not shown)

DISCUSSION

We found that overall survival in children with an in-hospital cardiac arrest has increased nearly three-fold during the past decade, despite an increase in cardiac arrests due to non-shockable rhythms. This improvement was mediated by higher rates of survival during the acute resuscitation period and was not accompanied by increased rates of significant neurological disability among survivors. Our results highlight the substantial progress that has occurred in pediatric resuscitation care in hospitals over the past decade.

To our knowledge, this is the first study that has documented improved survival over time in children with an in-hospital cardiac arrest. Most of the earlier studies of pediatric inhospital cardiac arrest were single-center and retrospective in nature with only a few years of data collection, thus precluding a trend analysis.1, 2, 8, 9 Although indirect comparisons with studies done in the 1980s may suggest that cardiac arrest survival in hospitalized patients has improved, differences in inclusion criteria (e.g., inclusion of pediatric trauma patients), definitions of cardiac arrest (e.g., inclusion of patients with bradycardia), and changing patient and cardiac arrest characteristics over time make these comparisons difficult to interpret. 8, 9 The larger size, scope and high quality of data within GWTG-Resuscitation, along with its use of standardized Utstein-style definitions for variables, allowed us to perform an evaluation of survival trends in children to address an important knowledge gap in pediatric in-hospital resuscitation.

We found that the marked improvement in survival was largely driven by a temporal improvement in rates of acute resuscitation survival. A number of factors may have played an important role in achieving these trends. First, clinical practice guidelines over the past decade have emphasized several aspects of the acute resuscitation survival chain.17 These include greater vigilance and closer monitoring, which may have resulted in shorter response times. In fact, we found that over time, a higher proportion of patients were located in a monitored unit or an intensive care unit at the time of cardiac arrest, which may have allowed earlier recognition of cardiopulmonary compromise and prompt initiation of resuscitation efforts. This might also explain the temporal increase in non-shockable rhythms due to PEA that was observed in our study. Second, it is possible that hospital-specific quality improvement efforts may have led to improved survival over time. Initial studies suggest improved patients outcomes with use of routine mock codes in pediatric hospitals, audiovisual feedback during resuscitation, and post-event debriefing.18–20 Additional resuscitation factors, such as availability of trained personnel, quality of chest compressions (e.g., depth, rate) with minimal interruptions, better adherence to resuscitation algorithms, as well as improved coordination between code team members may have also played an important role. Unfortunately, data on these aspects of resuscitation process and quality are difficult to assess accurately and are not collected within GWTG-Resuscitation limiting our ability to examine their impact on survival. Third, although the success of ECPR in salvaging cardiac arrest patients who otherwise face imminent death due to failure of standard resuscitation efforts has been described, 7, 21 we found that benefit was only limited to acute resuscitation survival without a significant impact on overall survival to discharge. Further, increase in use of ECPR did not account for the temporal trends in cardiac arrest survival in this study.

It is possible that improvements in post-resuscitation care have also contributed to increased survival over time in this population. Although our risk-adjustment models did not detect a significant improvement in post-resuscitation survival over time, these analyses were likely underpowered since only patients who survived the initial resuscitation are eligible for this analysis.

An important finding of our study was the notable reduction in the proportion of cardiac arrests due to VF and pulseless VT over time. These rhythms are more common in children with underlying cardiac disease. Although the exact mechanisms behind this changing epidemiology of cardiac arrest rhythms are not clear, it is possible that greater use of minimally invasive approaches in repair of congenital heart disease, advances in intra-operative management of children undergoing cardiac surgery with reduction of ischemia time, and better post-operative management of surgical patients have resulted in a reduction of VF and pulseless VT rhythms in this population.22, 23 At the same time, increasing severity of non-cardiac illness in pediatric intensive care unit patients may have led to an increase in the proportion of cardiac arrests due to non-shockable rhythms, especially PEA. In our analyses, we explicitly accounted for the above temporal shifts in cardiac arrest rhythms given that survival due to VF and pulseless VT rhythms is better than survival due to asystole and PEA arrest rhythms.3

It may be argued that an improved temporal trend in survival simply represents a decrease in baseline risk over time. However, our data suggest a more complex picture. Although some factors that are associated with in-hospital mortality decreased over time (e.g., previous and concurrent heart failure, worse baseline neurological function), other factors associated with a poor prognosis increased over time (e.g., cardiac arrest due to non-shockable rhythms, use of mechanical ventilation and use of intravenous vasoactive agents prior to cardiac arrest). Importantly, we adjusted for these variables in our multivariable models to control for potential confounding.

While it is encouraging to note that in-hospital cardiac arrest survival has improved substantially over the past decade, several questions remain unanswered. First, it is unknown to what extent improved survival trends have occurred at the hospital-level and whether this trend is consistent across all hospitals. Future studies are needed to examine hospital variation in survival trends. Second, the specific factors that are associated with improvements in hospital survival rates remain unknown. These may include non-structural hospital characteristics, such as timeliness and quality of resuscitation, teamwork, hospital leadership and culture, care coordination, and innovative quality improvement initiatives. Ultimately, a better understanding of practices and interventions at hospitals that achieve superior outcomes with in-hospital resuscitation will likely require a mixed methods approach using data from detailed site interviews and quantitative surveys. Once identified, these ‘best practices’ can be disseminated to all hospitals and measured, to ensure they lead to improved resuscitation outcomes.24

Our study should be interpreted in the context of the following limitations. First, although the rich data in GWTG-Resuscitation allowed us to adjust for a number of variables in our models, the potential for residual confounding remains. Second, data on specific resuscitation variables (e.g., quality of chest compressions), treatments (e.g., use of hypothermia) and hospital facility characteristics (e.g., number of pediatricians, quality improvement efforts) were not available, precluding an assessment of their potential impact on improved survival over time. Third, given the smaller sample size and high rates of missing data (17%), we were only able to examine unadjusted trends in rates of neurological disability. Therefore, our findings on this secondary outcome should be interpreted with caution. Fourth, the size of our study sample did not allow us to compute risk-adjusted survival by calendar year within important patient subgroups (e.g., initial cardiac arrest rhythm, monitored vs. non-monitored unit). Fifth, our study was limited to inhospital survival, and information on long-term survival and neurological function are not collected within GWTG-Resuscitation. Sixth, we were unable to calculate cardiac arrest incidence rates due to lack of information on hospitals’ pediatric admission volume. As a result, we are unable to examine how cardiac arrest incidence over time relates to survival trends. Finally, although this is the largest study to examine survival trends in pediatric inhospital cardiac arrests, our study included 12 hospitals and 1031 patients. It is possible that hospitals participating in a quality improvement registry differ from non-participating hospitals in important ways, limiting the generalizability of our results.

In conclusion, we found that overall survival in children with an in-hospital cardiac arrest has improved substantially over the past decade without higher rates of significant neurological disability. Future studies are needed to identify which factors are responsible for the improvements in cardiac arrest survival in children.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

FUNDING SOURCES

Dr. Paul Chan is supported by a Career Development Grant Award (K23HL102224) from the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute. Dr. John Spertus is supported by a Clinical and Translational Science Award (1UL1RR033179).

GWTG-Resuscitation is sponsored by the American Heart Association, which had no role in the study design, data analysis or manuscript preparation and revision.

Footnotes

DISCLOSURES

None

References

- 1.Suominen P, Olkkola KT, Voipio V, Korpela R, Palo R, Rasanen J. Utstein style reporting of in-hospital paediatric cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Resuscitation. 2000;45:17–25. doi: 10.1016/s0300-9572(00)00167-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Reis AG, Nadkarni V, Perondi MB, Grisi S, Berg RA. A prospective investigation into the epidemiology of in-hospital pediatric cardiopulmonary resuscitation using the international Utstein reporting style. Pediatrics. 2002;109:200–209. doi: 10.1542/peds.109.2.200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nadkarni VM, Larkin GL, Peberdy MA, Carey SM, Kaye W, Mancini ME, Nichol G, Lane-Truitt T, Potts J, Ornato JP, Berg RA. First documented rhythm and clinical outcome from inhospital cardiac arrest among children and adults. JAMA. 2006;295:50–57. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.1.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berg MD, Schexnayder SM, Chameides L, Terry M, Donoghue A, Hickey RW, Berg RA, Sutton RM, Hazinski MF. Part 13: pediatric basic life support: 2010 American Heart Association Guidelines for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care. Circulation. 122:S862–875. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.971085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.de Mos N, van Litsenburg RR, McCrindle B, Bohn DJ, Parshuram CS. Pediatric in-intensive-care-unit cardiac arrest: incidence, survival, and predictive factors. Crit Care Med. 2006;34:1209–1215. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000208440.66756.C2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Raymond TT, Cunnyngham CB, Thompson MT, Thomas JA, Dalton HJ, Nadkarni VM. Outcomes among neonates, infants, and children after extracorporeal cardiopulmonary resuscitation for refractory inhospital pediatric cardiac arrest: a report from the National Registry of Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2010;11:362–371. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0b013e3181c0141b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thiagarajan RR, Laussen PC, Rycus PT, Bartlett RH, Bratton SL. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation to aid cardiopulmonary resuscitation in infants and children. Circulation. 2007;116:1693–1700. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.680678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gillis J, Dickson D, Rieder M, Steward D, Edmonds J. Results of inpatient pediatric resuscitation. Crit Care Med. 1986;14:469–471. doi: 10.1097/00003246-198605000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zaritsky A, Nadkarni V, Getson P, Kuehl K. CPR in children. Ann Emerg Med. 1987;16:1107–1111. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(87)80465-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Peberdy MA, Kaye W, Ornato JP, Larkin GL, Nadkarni V, Mancini ME, Berg RA, Nichol G, Lane-Trultt T. Cardiopulmonary resuscitation of adults in the hospital: a report of 14720 cardiac arrests from the National Registry of Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation. Resuscitation. 2003;58:297–308. doi: 10.1016/s0300-9572(03)00215-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jacobs I, Nadkarni V, Bahr J, Berg RA, Billi JE, Bossaert L, Cassan P, Coovadia A, D’Este K, Finn J, Halperin H, Handley A, Herlitz J, Hickey R, Idris A, Kloeck W, Larkin GL, Mancini ME, Mason P, Mears G, Monsieurs K, Montgomery W, Morley P, Nichol G, Nolan J, Okada K, Perlman J, Shuster M, Steen PA, Sterz F, Tibballs J, Timerman S, Truitt T, Zideman D. Cardiac arrest and cardiopulmonary resuscitation outcome reports: update and simplification of the Utstein templates for resuscitation registries: a statement for healthcare professionals from a task force of the International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation (American Heart Association, European Resuscitation Council, Australian Resuscitation Council, New Zealand Resuscitation Council, Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada, InterAmerican Heart Foundation, Resuscitation Councils of Southern Africa) Circulation. 2004;110:3385–3397. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000147236.85306.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fiser DH, Long N, Roberson PK, Hefley G, Zolten K, Brodie-Fowler M. Relationship of pediatric overall performance category and pediatric cerebral performance category scores at pediatric intensive care unit discharge with outcome measures collected at hospital discharge and 1- and 6-month follow-up assessments. Crit Care Med. 2000;28:2616–2620. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200007000-00072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Samson RA, Nadkarni VM, Meaney PA, Carey SM, Berg MD, Berg RA. Outcomes of in-hospital ventricular fibrillation in children. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:2328–2339. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa052917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Greenland S. Model-based estimation of relative risks and other epidemiologic measures in studies of common outcomes and in case-control studies. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;160:301–305. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwh221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zou G. A modified poisson regression approach to prospective studies with binary data. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;159:702–706. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwh090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Raghunathan TESP, Van Hoeyk J. IVEware: Imputation and Variance Estimation Software - User Guide. Michigan: Survey Research Center, Institute for Social Research University of Michigan; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kleinman ME, Chameides L, Schexnayder SM, Samson RA, Hazinski MF, Atkins DL, Berg MD, de Caen AR, Fink EL, Freid EB, Hickey RW, Marino BS, Nadkarni VM, Proctor LT, Qureshi FA, Sartorelli K, Topjian A, van der Jagt EW, Zaritsky AL. Part 14: pediatric advanced life support: 2010 American Heart Association Guidelines for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care. Circulation. 122:S876–908. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.971101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Abella BS, Edelson DP, Kim S, Retzer E, Myklebust H, Barry AM, O’Hearn N, Hoek TL, Becker LB. CPR quality improvement during in-hospital cardiac arrest using a real-time audiovisual feedback system. Resuscitation. 2007;73:54–61. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2006.10.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Edelson DP, Litzinger B, Arora V, Walsh D, Kim S, Lauderdale DS, Vanden Hoek TL, Becker LB, Abella BS. Improving in-hospital cardiac arrest process and outcomes with performance debriefing. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168:1063–1069. doi: 10.1001/archinte.168.10.1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hunt EA, Walker AR, Shaffner DH, Miller MR, Pronovost PJ. Simulation of in-hospital pediatric medical emergencies and cardiopulmonary arrests: highlighting the importance of the first 5 minutes. Pediatrics. 2008;121:e34–43. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-0029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kane DA, Thiagarajan RR, Wypij D, Scheurer MA, Fynn-Thompson F, Emani S, del Nido PJ, Betit P, Laussen PC. Rapid-response extracorporeal membrane oxygenation to support cardiopulmonary resuscitation in children with cardiac disease. Circulation. 122:S241–248. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.928390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vida VL, Padalino MA, Motta R, Stellin G. Minimally invasive surgical options in pediatric heart surgery. Expert Rev Cardiovasc Ther. 2011;9:763–769. doi: 10.1586/erc.11.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bronicki RA, Chang AC. Management of the postoperative pediatric cardiac surgical patient. Crit Care Med. 39:1974–1984. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31821b82a6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chan PS, Nallamothu BK. Improving outcomes following in-hospital cardiac arrest: life after death. JAMA. 2012;307:1917–1918. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.3504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.