Abstract

Summary

Consensus views on osteoporosis in men are reported

Background

Workshop within a meeting on osteoporosis in men to identify areas of consensus amongst a panel (the authors) and the participants of the meeting.

Methods

Public debate with an expert panel on preselected topics

Results and conclusions

Consensus views reached on diagnostic criteria for osteoporosis in men and defined aspects of the pathophysiology and treatment of osteoporosis in men

Keywords: Bone mineral density, Bone quality, Fracture risk, Gonadal hormone status, Obesity, Testosterone, Treatment, T-score

Introduction

The 5th international conference on osteoporosis in men was held in Genoa, 23–25th September 2010 during which a workshop was held on ‘Diagnostic and therapeutic controversies in male osteoporosis’. The aim of the workshop was in part to recognise the uncertainties, but also to identify areas of consensus amongst the panel (the authors) and the participants of the meeting. The findings are summarised below.

Diagnosis of osteoporosis in men

The operational definition of osteoporosis is based on the T-score for bone mineral density (BMD). A threshold T-score of −2.5 SD or less, provided by a WHO report, is now a well accepted threshold [1, 2]. A strength of this diagnostic threshold as a reference standard has been the fashioning of a common approach to describe the disease. Developments since 1994, however, have eroded its value. These include the introduction of many new technologies for the measurement of bone mineral, the plethora of skeletal sites available for assessment, and an increased understanding of osteoporosis in men (not provided for in the WHO report).

The T-score varies in the same individual according to the skeletal site measured and the technique used. It is also critically dependent on the reference data used to describe the value in young healthy individuals and the variance of the measurements in the reference population. For these reasons, the WHO and IOF have supported the use of a single reference population (the NHANES III, women aged 20–29 years), a single reference site (the femoral neck) and a single technology (DXA) [3, 4]. Thus osteoporosis in men would be defined as a BMD value at the femoral neck that lay 2.5 SD or more below the average value of young healthy women (the NHANES III values). This view, supported by the meeting and panellists was based on the clinical observations summarised below.

The appropriateness of uniform thresholds for men and women depends upon gender-specific clinical correlates of BMD and fracture outcomes. The many studies that have examined fracture risk in men and women have come to disparate conclusions concerning the relationship between fracture risk and BMD [9–13]. There are several reasons for these discrepancies: Firstly, the relation between BMD and fracture risk changes with age [5–9], so that age-adjustment is required. Second, a difference between sexes in the gradient of risk (relative risk per SD decrease in BMD) could be the result of differences in the SD of measurements [10]. Third, data derived from separate male and female populations or from referral populations of osteoporotic men and women [6, 11] are likely to be biased.

These problems can be avoided by sampling populations at random and expressing risk as a function of BMD or standardised T-scores and with age adjustment. There are two components of risk that need to be addressed. The first is whether there are differences in the gradient of risk (the increase in fracture risk for each unit decrease in BMD) between men and women. The second is to determine whether there are differences in absolute risk between men and women for any given BMD.

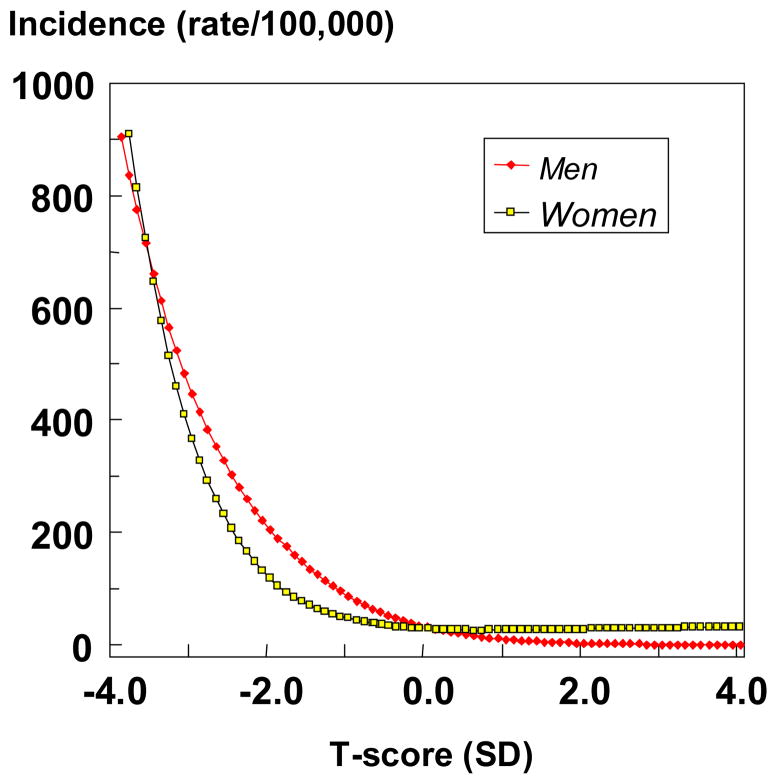

The gradient of risk has been examined most extensively in a meta-analysis of the primary data from 12 population based cohorts comprising 39,000 men and women [12]. The gradients of risk conferred by femoral neck BMD was highest for hip fracture, intermediate for osteoporotic fracture and lowest for any fracture. There was however, no difference in the gradient of risk between men and women for any of these fracture outcomes. Although gradients of risk are similar between men and women, absolute risks may differ. The comparative studies available show that the risk of hip fracture (and all osteoporotic fractures combined) is similar in men and women for any given absolute value for BMD measured mainly at the hip [7, 12–16]. In the meta-analysis described above the relationship between hip fracture incidence and BMD at the proximal femur was identical in men and women at any given age (Figure 1). These studies indicate that a similar cut-off value for femoral neck BMD that is used in women should be used in the diagnosis of osteoporosis in men. The use of female- rather than male-derived thresholds affects the apparent prevalence of osteoporosis but the effect is modest. In Sweden, for example, the prevalence of osteoporosis in men is 2.4% at the age of 50 years and rises to 14% at the age of 80 years. When the NHANES III reference values for men are used the apparent prevalence is 2.8 and 15.4%, respectively [17].

Figure 1.

The age-adjusted incidence of hip fracture in men and women according to the T-score for femoral neck BMD in the cohorts used to construct FRAX. Derived from the data reported in [12]

This recommendation should not be taken to infer that the use of other techniques or other sites do not have clinical utility for the management of patients where they have been shown to provide information on fracture risk. Nor should it be assumed that femoral neck BMD provides the same information in men and women for all fracture outcomes other than for hip fracture or all fractures combined. Although the implementation of probability based fracture risk assessment (e.g. FRAX) will decrease the clinical utility of the T-score, diagnostic criteria remain of value in quantifying the burden of disease and the development of strategies to combat osteoporosis in the foreseeable future. The standardisation of the T-score and its uniform application in men and women will assist these goals.

Qualities of bone in men

Fracture is the result of failure of the material composition and the structural design of bone to tolerate the loads imposed upon it [18]. These properties, or bone ‘qualities’, are compromised with the emergence of age-related abnormalities in bone modelling and remodelling, the cellular machinery responsible for the attainment of peak bone strength during growth and its maintenance during adulthood [19, 20].

The abnormalities contributing to material and structural decay are (i) a negative bone balance produced by each basic multicellular unit (BMU) in both sexes [21], (ii) a sustained increase in remodelling intensity in midlife in women but not in men [22] unless frankly hypogonadal [22, 23], (iii) reduced periosteal apposition after completion of longitudinal growth in both sexes [24], and (iv) secondary hyperparathyroidism in both sexes. However, the most important cause of bone loss is the increase in the intensity of bone remodelling on the trabecular, intracortical and endocortical bone surfaces. The high intensity of remodelling upon trabecular surfaces is likely to contribute to the complete loss of trabecular plates and loss of connectivity in women. By contrast, trabecular bone loss proceeds mainly by thinning in men [25]. Remodelling on intracortical surfaces results in intracortical porosity, particularly in cortex adjacent to the marrow cavity, trabecularisation of the endosteal cortex and a decrease in cortical width [26]. The effect is likely greater in women than in men [27, 28]. Periosteal apposition slows after completion of growth [29]. Some, but not all, studies suggest that men have greater periosteal apposition than women [30, 31]. Cross sectional studies are confounded by sex- specific secular trends in growth [32].

In addition to the changes in trabecular and cortical morphology, abnormalities in bone remodelling produce changes in bone ‘qualities’ at higher levels of resolution. In some studies for example, advancing age is associated with a reduction in osteonal size [33– 35], accompanied by an increase in Haversian canal diameter due to the reduced bone formation by each BMU [33]. Smaller osteons result in less resistance to crack propagation through interstitial bone [36]. Also, smaller osteons give rise to a greater proportion interstitial (rather than osteonal) bone which has a higher tissue mineralization density, fewer osteocytes and is liable to accumulate microdamage and offer less resistance to crack propagation [37]. These phenomena are likely to occur in both sexes but in women, osteonal density (the number per unit volume) may increase because of the high intracortical remodelling; the osteons are smaller but there are more of them. This may protect against the deleterious effect of a higher amount of interstitial bone.

Abnormalities in the material properties of bone are reported in women [38–41] but little is known of these properties in men

Sex differences in bone size are often cited as contributing to the lower incidence of fractures in men than women but men also have larger muscle mass and higher body weight so that compressive stress (load/area) is similar in young adult men and women [42]. This notion is also difficult to reconcile with the observation that Asians have a smaller skeleton yet lower fracture rates than Caucasians, and that women with hip fractures have larger femoral neck diameter than controls. Men and women have similar cortical thickness which confers a greater cortical area in men (because their bones have a larger perimeter). Peak trabecular number and thickness is similar in men and women at the iliac crest and vertebral bone. Some studies report men have thicker trabeculae at the distal radius which may be more resistant to perforation.

Reasons for sex differences in bone fragility are likely to be multifaceted. These include sex differences in trabecular morphology (thinning in men and perforation in women), less cortical porosity, endocortical remodelling and thinning in men than in women, particularly and possibly greater periosteal apposition in men than in women. Other factors that may contribute to sex differences in bone fragility, but require further study include differences in osteonal morphology, tissue mineralisation and matrix composition.

Against this background, it is perhaps surprising that for any given bone mineral density measured by DXA at the femoral neck, the hip fracture risk is similar in men and women. The sexual dimorphism described above suggests that this may not be true for other sites of BMD measurement and other fracture outcomes. Rather, the phenomenon may be a fortuitous artefact occasioned by the larger bone size of men and areal nature of the measured density. Ultimately, the hope is that understanding the major determinants of differences in strength will give rise to new technologies to be used in combination or in addition to DXA.

Therapeutic issues in male osteoporosis

Agents approved by the USA FDA for the treatment of osteoporosis in men are fewer compared to those approved for women (Table 1). The clinical trials that have led to the registration of these drugs for women have typically been based upon large multinational trials. These trials have been randomized and placebo-controlled with well designed fracture end points. Fracture efficacy in all cases has been demonstrated at the spine and less consistently at non-vertebral sites.

Table 1.

Agents approved by the FDA for the prevention and treatment of osteoporosis

| Agent | Postmenopausal osteoporosis | Glucocorticoid induced osteoporosis in men and women | Osteoporosis in men | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Prevention | Treatment | Prevention | Treatment | ||

| Estrogen | + | ||||

| Calcitonin | + | ||||

| Raloxifene | + | + | |||

| Denosumab | + | ||||

| Ibandronate | + | + | |||

| Alendronate | + | + | + | + | |

| Risedronate | + | + | + | + | + |

| Zoledronic acid | + | + | + | + | + |

| Teriparatide | + | + | + | ||

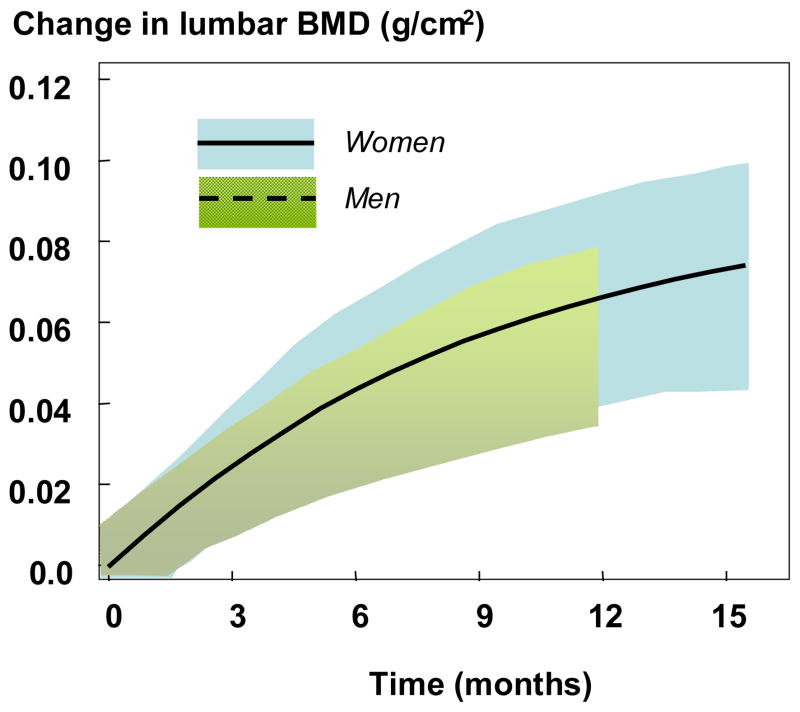

Clinical trials that have led to the registration of these agents in men differ in a number of ways. First, the numbers of male subjects are small relative to the thousands of postmenopausal women who have been studied. Indeed, in phase III studies, the proportion of men who constitute the database of results of these clinical trials, only about 10% [43–54]. The clinical trials in men were conducted and reported several years after the definitive trials in women. Rather than fracture efficacy as the end point, the clinical trials in men have, with the occasional exception [55, 56] used surrogate markers such as BMD and at times, markers of bone turnover. The use of these surrogate markers are based upon the principle of therapeutic equivalence. For example, if treatment-induced changes in BMD over the same period of time do not differ from the changes seen in postmenopausal women, then the expectation is that the fracture end point would also be the same. Figure 2 shows an example of the equivalence teriparatide in men and women using BMD as the equivalence parameter. Over the 11 months of the clinical trial of teriparatide in male osteoporosis, the increase in BMD was virtually identical to the increase in bone mineral density in the registration trial for women [46, 47].

Figure 2.

Changes in bone mineral density and 95% confidence intervals (shaded) after teriparatide administration 20μg daily in men (dashed line) and women (solid line) [data from 46 and 47].

The use of equivalence studies with a focus on surrogate markers for the fracture end point relies upon an assumption that the surrogate markers predict accurately the end point. It is important to recognize, however, that increases in bone mineral density account, in general, for less than 50% (4–30%) of the variance in fracture reduction. There is, thus, an inherent uncertainty about using endpoints other than the fracture end point.

Other points are noteworthy with regard to the equivalence concept. First, clinical trials in men have been conducted separately from the clinical trials in women. Second, the pathogenesis of osteoporosis in men is not necessarily the same as it is for women. If underlying abnormalities are different between men and women, the premise that similar changes in surrogate markers will predict fracture reduction equally well, could be challenged. Based in part on this uncertainty, sensitivity to the therapeutic agent might differ even though changes in the surrogate marker might be similar.

Although these caveats are potentially important, it is noteworthy that the responsiveness of drugs approved for postmenopausal and men appear to show similar results with regard to the end points that have been monitored, including a limited data base on fracture outcomes. Since osteoporosis in men now constitutes a sizable proportion of all persons with bone fragility, it seems reasonable to suggest that future trials should include larger numbers of male subjects and also that the endpoints to be defined in women are applied similarly to men. Indeed there is a case for the inclusion of men and women together in the design of phase III studies [57]

The use of non-skeletal factors in the assessment of fracture risk

Physical function tests, fall risk and fractures

Fractures occur because force exerted on bone exceeds its strength. Hence it is to be expected that estimates of both bone strength and of trauma (usually a fall) are associated with fracture risk, and indeed there is abundant evidence that both are true in men and in women [58–60]. Whereas assessments of bone strength (usually DXA) are routinely incorporated into clinical algorithms for assessing fracture risk, there are no well accepted measures of the propensity to fall. This is not because data are not available to link assessments of falls to fracture risk, but rather that a single, easy to perform measure has not been widely validated and adopted as a reference standard.

A variety of measures of prospective fall risk has been shown to be useful in predicting fractures in men. They include questions or questionnaire based tools, simple physical performance tests, and devices that measure some aspect of strength, balance or integrated function. For the purposes of the clinical assessment of future fracture risk it is important that questions or simple physical performance tests provide risk prediction [61] and do not require devices inherently more expensive to purchase and maintain.

The strong association between lower levels of physical performance and fracture risk suggests that the inclusion of one of these assessments should be recommended in the routine diagnostic evaluation of osteoporosis in men. On the other hand, doing so assumes that there is some practical benefit to be derived from gathering the information in terms of interventions that could reduce the risk of fracture. Whereas exercise programmes have been shown to reduce fall risk in the frail elderly [62], the benefits for fracture prevention are less clearly documented. It is nevertheless a reasonable assumption that physical therapy programmes should have beneficial effects on fracture risk. In addition, evidence suggests that correction of vitamin D deficiency may reduce fracture risk in part because of a reduction in falls [62, 63]. Whether pharmacological therapies used to increase bone strength (e.g. bisphosphonates, teriparatide) can be used to reduce fractures in men who are at risk of falls is untested and, in women, the evidence is equivocal [64].

Obesity and fractures

Individuals with higher body mass index (BMI) have been considered to be at lower risk of fracture and those with low weight are consistently noted to have a higher incidence of fracture [65]. To some extent this may be because BMD is positively associated with BMI, thus perhaps providing an increase in bone strength and fracture resistance even when fall forces may be higher due to greater body mass. Most studies of the effect of BMI on fracture risk have considered cohorts that are not particularly obese [65].

Unfortunately, obesity is increasingly prevalent in many Western societies. In the US the majority of the adult male population is overweight or obese [66, 67] and very few are of low weight. It is perhaps surprising that most studies of the impact of BMI on fracture rates have not studied obese populations. Recent results from MrOS show that, whereas men of normal weight have a slightly lower risk of hip and other non-vertebral fractures than the overweight or moderately obese, most fractures (>60%) occur in overweight and obese men [68]. In large part that is because most men are overweight or obese; so despite their slightly lower overall risk of fracture the larger number of fractures occur in this segment of the population. But also, the most obese men are actually not protected from fracture (their fracture risk is as high as in normal weight men) and when adjusted for BMD their fracture risk is considerably higher (5 fold higher) than men with normal BMI [68]. Many obese men have a lower BMD than would be predicted from their BMI so are not protected. In addition, the MrOS analysis suggested that poor physical function, and thus perhaps a greater risk of falls, contributes to the increased risk in the most obese [68]. Finally, regardless of weight hip tissue thickness doesn’t seem to protect men from hip fracture as it may in women [69], probably because there is a sex difference in weight distribution (more truncal obesity in men) and tissue thickness over the hip is usually much less in men than in women [69].

These data are important because there is little recognition of the public health importance of fractures in the obese, and clinical approaches to fracture risk assessment in the obese are not well developed. As a result, many clinicians are not aware of the potential for fractures in overweight and obese men, and may indeed believe them to be at very low risk. Thus diagnostic and therapeutic measures may not be adequately provided.

More data are needed about this issue, but we recommend that clinicians be aware of the importance of fractures in overweight and obese men, that appropriate assessment of fracture risk be undertaken in men regardless of weight, and that interventions to prevent fractures be offered in overweight/obese men when appropriate. Physical therapy may be useful in the presence of reduced physical performance. The appropriateness of recommending weight loss is unknown.

Pathophysiology of osteoporosis in men

There are three predominant factors that contribute to bone fragility in men: genetic factors, alterations in sex steroid levels, and diseases causing secondary osteoporosis [70]. The vast majority of studies addressing the genetic contributions to bone mass and fracture risk have been done in women; however, evidence suggests that the genetic determinants of bone mass may not be identical in women and in men. For example, Peacock et al. [71] measured spine and hip BMD in 515 pairs of brothers, aged 18–61 years, and performed linkage analysis in this sample which was compared with results in a previous sample of 774 sister pairs in order to identify possible sex-specific quantitative trait loci (QTLs). In the analysis in men, the investigators identified significant QTLs (LOD > 3.6) for BMD on chromosome 4q21 (hip), 7q34 (spine), 14q32 (hip), 19p13 (hip), 21q21 (hip), and 22q13 (hip). In comparing the female data, the QTLs on chromosomes 7, 14, and 21 were male-specific, whereas the others were not. Collectively, these data highlight the complexity of the genetics of a trait such as BMD, as well as the fact that the genes determining BMD are likely, at least partly, to be gender-specific.

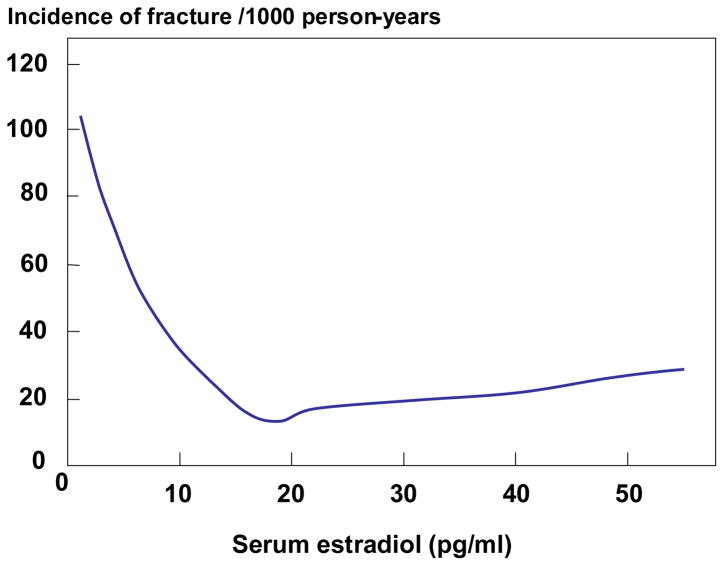

There is compelling evidence that declining levels of bioavailable estrogens (non-sex hormone binding globulin [SHBG]-bound) levels with age contribute to bone loss and fracture risk in men [70, 72]. Previous work has demonstrated that estrogen plays an important, and perhaps dominant, role in regulating bone density [73], bone resorption [74, 75], and bone loss [76, 77] in elderly men as well as in the acquisition of peak bone mass and in the pathogenesis of idiopathic osteoporosis in young men [78]. In addition, there appeared to be a threshold serum estradiol level below which the male skeleton became estrogen deficient [76, 79]. The most definitive data addressing this issue have come from the MrOS cohort. Mellstrom et al [80] analyzed sex steroids using gas chromatography-mass spectroscopy in 2639 elderly men (mean age, 75 years) from the Swedish arm of MrOS and evaluated fractures over a mean follow up period of 3.3 years. In multivariable proportional hazards regression models, free estradiol and SHBG, but not free testosterone, were independently associated with fracture risk. In further sub-analyses, free estradiol was inversely associated with clinical vertebral fractures (HR per SD decrease, 1.57; 95% CI, 1.36–1.80), non-vertebral osteoporotic fractures (HR per SD decrease, 1.42; 95% CI, 1.23–1.65), and hip fractures (HR per SD decrease, 1.44; 95% CI, 1.18–1.76). Furthermore, and consistent with a threshold effect, the inverse relation between serum estradiol and fracture risk was non-linear (Figure 3). Specifically, the yearly incidence of fractures was inversely associated with serum estradiol levels at estradiol levels less than 16 pg/ml; above this level, there was no relationship between fracture incidence and estradiol levels.

Figure 3.

Yearly incidence of fractures as a function of serum estradiol levels in men from MrOS Sweden. Poisson regression models were used to determine the relation between serum estradiol levels and fracture risk. Reproduced from Mellstrom et al. [80], with permission of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research

These findings also have potential clinical implications. First, from a diagnostic standpoint, measurement of serum sex steroid levels, particularly estradiol levels, in men with osteoporosis may be useful. However, this has to await further evaluation following standardization of sex steroid assays, likely using mass spectroscopy. Second, these data strengthen the rationale for assessing the use of selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERMs) in preventing bone loss in aging men. Third, these findings raise potential concerns about the utility of non-aromatizable selective androgen receptor modulators (SARMs) in preventing bone loss in men, since to the extent that the major sex steroid effect on bone is mediated by estrogen, these non-aromatisable compounds may have minimal skeletal effects, at least in humans. Nonetheless, SARMs may be useful in enhancing muscle strength and reducing fall risk, and have anti-fracture effects through these non-skeletal actions.

There are also a number of possible secondary causes of secondary osteoporosis in men that may be superimposed on underlying age-related bone loss. Indeed, in some series, secondary causes may account for, or contribute significantly to, up to 40% of the cases of osteoporosis in men [81]. The three major causes of secondary osteoporosis in men are alcohol abuse, glucocorticoid excess (either endogenous or, more commonly, chronic glucocorticoid therapy), and overt hypogonadism, with the latter increasingly due to hormonal suppressive therapy for the treatment of prostate cancer [82]. Of these, glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis is the most common cause of secondary osteoporosis in men. Other causes of secondary osteoporosis (discussed in detail elsewhere [83] should be considered and ruled out in the appropriate clinical context.

The use of testosterone in men

In hypogonadism before puberty with failure of timely and full pubertal development, and thus suboptimal androgen and oestrogen exposure, osteoporosis results from deficient accretion of bone mass and size. The potential reversibility by restoring normal serum testosterone levels is dependent on the stage of skeletal maturation.

Acquired profound hypogonadism in adulthood induces a state of high bone turnover with accelerated bone loss and increased fracture risk [84–87], which results from combined deficiency of testosterone and oestradiol - the main aromatisation product of testosterone [74, 79, 88]. Profound hypogonadism is usually symptomatic with a broad spectrum of adverse effects on health and quality of life. For this reason, symptomatic hypogonadism is considered an indication for testosterone substitution at all ages, unless there are specific contra-indications [89]. Observational data indicate that treatment with testosterone will reduce bone turnover and prevent further bone loss, and even increase BMD, at least in some patients. Effects on fracture risk have not been assessed [70, 88, 90].

In the case of low serum testosterone due to long-term treatment with systemic glucocorticoid administration, few data are available showing beneficial effects of testosterone treatment on BMD [91]. Considering the now well established role of oestradiol in the regulation of bone homeostasis [79], treatment with non-aromatisable androgens should not be assumed to ensure adequate protection against bone loss. In view of the lack of documentation of anti-fracture efficacy of testosterone, treatment of osteoporosis should include established osteoporosis treatments whether or not on testosterone substitution. Similarly, in men with profound hypogonadism due to androgen deprivation therapy for prostate cancer, treatment with testosterone is contra-indicated. In such cases, established antiresorptive osteoporosis medication such as SERMs, bisphosphonates and denosumab, can effectively reduce bone turnover, prevent bone loss [92–95] and reduce fracture risk [56].

Aging is accompanied by progressive moderate decrease in the population mean serum concentration of testosterone. A marked age-related increase of serum sex hormone-binding globulin (SHBG) levels is also found which results in a decrease in the non-SHBG-bound fractions of testosterone available for biological action, i.e. decreased free- and bioavailable testosterone, as well as a moderate decrease of free- and bioavailable oestradiol [95]. With aging, there is an increasing prevalence of men with serum (free, bioavailable) testosterone levels that lie below the range for young men. Aging in men is, on the other hand, accompanied by increasing prevalence of signs and symptoms, including osteoporosis, that are reminiscent of those observed in young hypogonadal men, but which in the elderly are at most only in part related to the decline of testosterone production. The minimal testosterone needs in the elderly are not established and, moreover, are likely to vary between individuals and depending on the target tissue under consideration. Thus, with age, both low serum testosterone and symptoms and signs consistent with hypogonadism become increasingly prevalent but also less specific [95]. In this elderly population, effects of testosterone treatment on BMD have been inconsistent [70, 88, 95, 96], with the most convincing effects being observed in men with very low serum testosterone [97, 98]. In elderly men, testosterone treatment may have additional beneficial effects on muscle mass and strength, which may help decrease fracture risk through a reduced propensity to fall. Nevertheless, the effect of testosterone treatment on fracture risk is unknown and the long-term risk-benefit ratio of prolonged treatment in elderly men is not established. The potential adverse effects on haematocrit, prostate and cardiovascular risk requires appropriate alertness [89, 99, 100]. By contrast, treatment with bisphosphonates and teriparatide has been shown to be effective in men with low baseline serum testosterone in subgroup analysis of clinical trials of treatment [43, 47, 51].

In this context, hypogonadism in older men requires a conservative approach and testosterone treatment should be considered only for men with frankly low serum testosterone as measured on repeated occasions with a reliable assay on blood samples obtained in the morning, in the presence of unequivocal signs and (preferably spontaneously reported) symptoms of hypogonadism, after exclusion of reversible causes of hypogonadism and contra-indications for testosterone treatment [89, 95, 101].

In summary, testosterone replacement therapy is indicated in well established symptomatic hypogonadism independently of age, but although this treatment has beneficial effects on the maintenance of skeletal integrity, osteoporosis is neither a sufficient nor a specific indication for testosterone treatment.

Conclusions

Consensus views include

The use of a single reference population (the NHANES III, women aged 20–29 years), at single reference site (the femoral neck) and a single technology (DXA) should be used for the diagnosis of osteoporosis in men.

Despite good evidence for sex-specific differences in the structural and material properties of bone, further research is necessary before this can be clinically applied to aid in fracture risk assessment.

The level of evidence that treatment decreases the risk of fracture in men is less than in women. The similarity between sexes in the effects on BMD and the few available data on fracture endpoints are consistent with the view that efficacy of intervention in men does not differ from that shown in women.

The strong association between falls and lower levels of performance with fracture risk in men suggests that they should be used in the assessment of fracture risk in men. An easy to perform validated measure of falls and of performance should be adopted and included in future trials and observational studies as reference standards. This is expected to aid in assessing their utility in targeting intervention.

Obese men are not protected from fracture. In the very obese, fracture risk appears to be increased when adjusted for BMD.

The genetic determinants of the variance in bone mass may not be identical in women and in men.

Decreasing levels of bio available estrogens (non-sex hormone binding globulin [SHBG]-bound) levels with age contribute significantly to bone loss and fracture risk in men.

There is a limited place for testosterone in men with osteoporosis. Whereas testosterone replacement is indicated in symptomatic hypogonadism, osteoporosis should be treated with agents shown to decrease fracture risk whether or not patients are taking testosterone.

Footnotes

Competing interests

JAK has nothing to declare for FRAX and the context of this paper, but numerous ad hoc consultancies for governmental, non-governmental agencies and the pharmaceutical industry. GB and ES have no competing interests with regard to this manuscript. SK; Advisory board for Amgen. JPB is a consultant for Amgen.

Contributor Information

John A Kanis, WHO Collaborating Centre for Metabolic Bone Diseases, University of Sheffield Medical School, UK.

Gerolamo Bianchi, Division of Rheumatology, ASL3 Genovese, Genoa, Italy.

John P Bilezikian, Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons, New York, New York 10032, USA.

Jean-Marc Kaufman, Department of Endocrinology, Ghent University Hospital, Gent, Belgium.

Sundeep Khosla, College of Medicine, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN, USA.

Eric Orwoll, Bone and Mineral Unit, Oregon Health and Science University, Portland, Oregon, USA.

Ego Seeman, Department of Endocrinology and Medicine, Austin Health, University of Melbourne, Melbourne, Australia.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Technical Report Series. WHO; Geneva: 1994. Assessment of fracture risk and its application to screening for postmenopausal osteoporosis; p. 843. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kanis JA, Melton LJ, Christiansen C, Johnston CC, Khaltaev N. The diagnosis of osteoporosis. J Bone Miner Res. 1994;9:17–1141. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.5650090802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kanis JA, McCloskey EV, Johansson H, Oden A, Melton LJ, Khaltaev N. A reference standard for the description of osteoporosis. Bone. 2008;42:467–475. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2007.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kanis JA, Glüer CC for the Committee of Scientific Advisors, International Osteoporosis Foundation. An update on the diagnosis and assessment of osteoporosis with densitometry. Osteoporos Int. 2000;11:192–202. doi: 10.1007/s001980050281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Orwoll E. Assessing bone density in men. J Bone Miner Res. 2000;15:1867–1870. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2000.15.10.1867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Selby PL, Davies M, Adams JE. Do men and women fracture bones at similar bone densities. Osteoporos Int. 2000;11:153–157. doi: 10.1007/PL00004177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lunt M, Felsenberg D, Reeve J, et al. Bone density variation and its effects on risk of vertebral deformity in men and women studied in thirteen European centers: the EVOS Study. J Bone Miner Res. 1997;12:1883–94. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.1997.12.11.1883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nguyen T, Sambrook P, Kelly P, et al. Prediction of osteoporotic fractures by postural instability and bone density. Br Med J. 1993;307:1111–1115. doi: 10.1136/bmj.307.6912.1111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Melton LJ, III, Atkinson EJ, O’Connor MK, O’Fallon WM, Riggs BL. Bone density and fracture risk in men. J Bone Miner Res. 1998;13:1915–1923. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.1998.13.12.1915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Melton LJ, III, Orwoll ES, Wasnich RD. Does bone density predict fractures comparably in men and women? Osteoporos Int. 2001;12:707–709. doi: 10.1007/s001980170044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cummings SR, Cawthon PM, Ensrud KE, et al. BMD and risk of hip and nonvertebral fractures in older men: a prospective study and comparison with older women. J Bone Miner Res. 2006;21:1550–6. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.060708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Johnell O, Kanis JA, Oden A, et al. Predictive value of bone mineral density for hip and other fractures. J Bone Miner Res. 2005;20:1185–1194. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.050304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kanis JA, Johnell O, Oden A, De Laet C, Mellstrom D. Diagnosis of osteoporosis and fracture threshold in men. Calcif Tissue Int. 2001;69:218–221. doi: 10.1007/s00223-001-1046-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.DeLaet CED, van Hout BA, Burger H, Hoffman A, Pols HAP. Bone density and risk of hip fracture in men and women: cross sectional analysis. Brit Med J. 1997;315:221–225. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7102.221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.DeLaet CEDH, Van Hout BA, Burger H, Hofman A, Weel AEAM, Pols HAP. Hip fracture prediction in elderly men and women: validation in the Rotterdam Study. J Bone Miner Res. 1998;13:1587–1593. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.1998.13.10.1587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wasnich RD, Davis JW, Ross PD. Spine fracture risk is predicted by non spine fractures. Osteoporos Int. 1994;4:1–5. doi: 10.1007/BF02352253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kanis JA, Johnell O, Oden A, Jonsson B, De Laet C, Dawson A. Risk of hip fracture according to World Health Organization criteria for osteoporosis and osteopenia. Bone. 2000;27:585–590. doi: 10.1016/s8756-3282(00)00381-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Currey JD. Bones: structure and mechanics. Princeton, N.J: Princeton University Press; 2002. pp. 1–380. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Parfitt AM. Skeletal heterogeneity and the purposes of bone remodeling: Implications for the understanding of osteoporosis. In: Marcus R, Feldman D, Nelson DA, Rosen CJ, editors. Osteoporosis. San Diego, CA: Academic; 2008. pp. 71–89. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Seeman E, Delmas PD. Bone quality the material and structural basis of bone strength and fragility. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:2250–61. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra053077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lips P, Courpron P, Meunier PJ. Mean wall thickness of trabecular bone packets in the human iliac crest: changes with age. Calcif Tissue Res. 1978;26:13–7. doi: 10.1007/BF02013227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Garnero P, Sorney-Rendu E, Duboeuf F, Delmas PD. Markers of bone turnover predict postmenopausal bone loss over 4 years: the OFELY study. J Bone Miner Res. 1999;14:1614–21. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.1999.14.9.1614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Smith MR, Goode M, Zietman AL, McGovern FJ, Lee H, Finkelstein JS. Bicalutamide monotherapy versus leuprolide monotherapy for prostate cancer: Effects on bone mineral density and body composition. J Oncol. 2004;22:2546–63. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.01.174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Balena R, Shih M-S, Parfitt AM. Bone resorption and formation on the periosteal envelope of the ilium: A histomorphometric study in healthy women. J Bone Miner Res. 1992;7:1475–1482. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.5650071216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Aaron JE, Makins NB, Sagreiya K. The microanatomy of trabecular bone loss in normal aging men and women. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1987;215:260–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zebaze R, Ghasem-Zadeh A, Bohte A, et al. Intracortical remodeling and porosity: rational targets for fracture prevention. Lancet. 2010;375:1729–36. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60320-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Burghardt AJ, Buie HR, Laib A, Majumdar S, Boyd SK. Rreproducibility of direct quantitative measures of cortical bone microarchitecture of the distal radius and tibia by HR-pQCT. Bone. 2010;47:519–28. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2010.05.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Burghardt AJ, Kazakia GJ, Ramachandran S, Link TM, Majumdar S. Age- and gender-related differences in the geometric properties and biomechanical significance of intracortical porosity in the distal radius and tibia. J Bone Miner Res. 2010;25:983–93. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.091104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bass S, Delmas PD, Pearce G, Hendrich E, Tabensky A, Seeman E. The differing tempo of growth in bone size, mass and density in girls is region-specific. J Clin Invest. 1999;104:795–804. doi: 10.1172/JCI7060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Duan Y, Wang XF, Evans A, Seeman E. Structural and biomechanical basis of racial and sex differences in vertebral fragility in Chinese and Caucasians. Bone. 2005;36:987–98. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2004.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Riggs BL, Melton LJ, III, Robb RA, et al. A population-based study of age and sex differences in bone volumetric density, size, geometry and structure at different skeletal sites. J Bone Miner Res. 2004;19:1945–54. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.040916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Seeman E. Periosteal bone formation — a neglected determinant of bone strength. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:320–3. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp038101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ural A, Vashishth D. Interactions between microstructural and geometrical adaptation in human cortical bone. J Orthop Res. 2006;24:1489–98. doi: 10.1002/jor.20159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nalla RK, Kruzic JJ, Kinney JH, et al. Role of microstructure in the aging-related deterioration of the toughness of human cortical bone. Materials Science and Engineering C. 2010;26:1251–1260. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yeni YN, Brown CU, Wang Z, Norman TL. The influence of bone morphology on fracture toughness of the human femur and tibia. Bone. 1997;21:453–9. doi: 10.1016/s8756-3282(97)00173-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Currey JD. The effect of porosity and mineral content on the Young’s modulus of elasticity of compact bone. J Biomech. 1988;21:131–139. doi: 10.1016/0021-9290(88)90006-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ciarelli TE, Fyhrie DP, Parfitt AM. Effects of vertebral bone fragility and bone formation rate on the mineralization levels of cancellous bone from white females. Bone. 2003;32:311–5. doi: 10.1016/s8756-3282(02)00975-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Qiu S, Rao DS, Fyhrie DP, Palnitkar S, Parfitt AM. The morphological association between microcracks and osteocyte lacunae in human cortical bone. Bone. 2005;37:10–15. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2005.01.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zebaze R, Seeman E, Ghasem-Zadeh A, et al. Australian provisional Patent No. 2009904407 Analysis System and Method. 2010

- 40.Saito M, Marumo K. Collagen cross-links as a determinant of bone quality: a possible explanation for bone fragility in aging, osteoporosis, and diabetes mellitus. Osteoporos Int. 2010;21:195–214. doi: 10.1007/s00198-009-1066-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tang SY, Zeenath U, Vashishth D. Effects of non-enzymatic glycation on cancellous bone fragility. Bone. 2007;40:1144–51. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2006.12.056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Duan Y, Seeman E, Turner CH. The biomechanical basis of vertebral body fragility in men and women. J Bone Mineral Res. 2001;16:2276–2283. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2001.16.12.2276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Orwoll E, Ettinger M, Weiss S, et al. Alendronate for the treatment of osteoporosis in men. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:604–610. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200008313430902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ho YV, Frauman aG, Thomson W, Seeman E. Effects of alendronate on bone density in men with primary and secondary osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int. 2000;11:98–101. doi: 10.1007/PL00004182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kurland ES, Cosman F, McMahon DJ, Rosen CJ, Lindsay R, Bilezikian JP. Parathyroid hormone as a therapy for idiopathic osteoporosis in men: effects on bone mineral density and bone markers. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2000;85:3069–3076. doi: 10.1210/jcem.85.9.6818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Neer RM, Arnaud CD, Zanchetta JR, et al. Effect of parathyroid hormone (1–34) on fractures and bone mineral density in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis. N Eng J Med. 2001;344:1434–1441. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200105103441904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Orwoll ES, Scheele WH, Paul S, et al. The effect of teriparatide [human parathyroid hormone (1–34)] therapy on bone density in men with osteoporosis. J Bone Miner Res. 2003;18:9–17. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2003.18.1.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gonnell S, Cepoliano C, Montagnani A, et al. Alendronate treatment in men with primary osteoporosis: a three-year longitudinal study. Calcif Tissue Int. 2003;73:133–159. doi: 10.1007/s00223-002-1085-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Drake WM, Kendler DL, Rosen CJ, Orwoll ES. An investigation of the predictors of bone mineral density and response to therapy with alendronate in osteoporotic men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88:5759–5765. doi: 10.1210/jc.2002-021654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Miller PD, Schnitzer T, Emkey R, et al. Weekly oral alendronic acid in male osteoporosis. Clin Drug Invest. 2004;24l:333–341. doi: 10.2165/00044011-200424060-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Boonen S, Orwoll ES, Wenderoth D, Stoner KJ, Eusebio R, Delmas PD. Once-weekly risedronate in men with osteoporosis: results of a 2-year, placebo-controlled, double-blind, multicenter study. J Bone Miner Res. 2009;24:719–725. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.081214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ringe JD, Farahmand P, Faber K, Dorst A. Sustained efficacy of risedronate in men with primary and secondary osteporoosis: results of a 2-year study. Rheumatol Int. 2009;29:311–315. doi: 10.1007/s00296-008-0689-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Orwoll ES, Miller PD, Adachi JD, et al. Efficacy and safety of a once-yearly i.v. infusion of zoledronic acid 5 mg versus a once-weekly 70-mg oral alendronate in the treatment of male osteoporosis: a randomized, multicenter, double-blind, active-controlled study. J Bone Miner Res. 2010;25:2239–2250. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Orwoll ES, Binkley NC, Lweiecki EM, Gruntmanis U, Fries MA, Dasic G. Efficacy and safety of monthly ibandronate in men with low bone density. Bone. 2010;46:970–976. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2009.12.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Steven Boonen S, Kaufman J_M, Reginster J-Y, et al. Antifracture efficacy and safety of once-yearly zoledronic acid 5mg in men with osteoporosis: a prospective, randomised, controlled trial. Osteoporos Int. 2011;22(Suppl 1) Abstract in press. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Smith MR, Egerdie B, Hernandez Toriz N, et al. Denosumab HALT Prostate Cancer Study Group (2009) Denosumab in men receiving androgen-deprivation therapy for prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 361:745–55. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0809003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.World Health Organization. Guidelines for preclinical evaluation and clinical trials in osteoporosis. WHO; Geneve: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lang T, Cauley JA, Tylavsky F, Bauer D, Cummings S, Harris TB. Computed tomographic measurements of thigh muscle cross-sectional area and attenuation coefficient predict hip fracture: The health, aging, and body composition study. J Bone Miner Res. 2010;25:513–519. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.090807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lewis CE, Ewing SK, Taylor BC, et al. Predictors of non-spine fracture in elderly men: the MrOS study. J Bone Miner Res. 2007;22:211–219. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.061017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Cummings SR, Nevitt MC, Browner WS, et al. Risk factors for hip fracture in white women. Study of Osteoporotic Fractures Research Group. N Engl J Med. 1995;332:767–773. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199503233321202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Cawthon PM, Fullman RL, Marshall L, et al. Physical performance and risk of hip fractures in older men. J Bone Miner Res. 2008;23:1037–44. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.080227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Michael YL, Whitlock EP, Lin JS, Fu R, O’Connor EA, Gold R. Primary care-relevant interventions to prevent falling in older adults: a systematic evidence review for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2010;153:815–825. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-153-12-201012210-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Bischoff-Ferrari HA, Orav EJ, Dawson-Hughes B. Effect of cholecalciferol plus calcium on falling in ambulatory older men and women: a 3-year randomized controlled trial. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:424–430. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.4.424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.McClung MR, Geusens P, Miller PD, et al. Effect of risedronate on the risk of hip fracture in elderly women. Hip Intervention Program Study Group. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:333–340. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200102013440503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.De Laet C, Kanis JA, Oden A, et al. Body mass index as a predictor of fracture risk: a meta-analysis. Osteoporos Int. 2005;16:1330–8. doi: 10.1007/s00198-005-1863-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Flegal KM, Carroll MD, Ogden CL, et al. Prevalence and trends in obesity among US adults, 1999–2008. JAMA. 2010;303:235–41. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sundquist J, Johnansson S-E, Sundquist K. Levelling off of prevalence of obesity in the adult population of Sweden between 2000/01 and 2004/05. BMC Public Health. 2010;2010:10. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-10-119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Nielson CM, Marshall LM, Adams AL, et al. BMI and fracture risk in older men: the osteoporotic fractures in men (MrOS) study. J Bone Miner Res. 2010 doi: 10.1002/jbmr.235. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Freitas SS, Barrett-Connor E, Ensrud KE, et al. Rate and circumstances of clinical vertebral fractures in older men. Osteoporos Int. 2008;19:615–623. doi: 10.1007/s00198-007-0510-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Khosla S, Amin S, Orwoll E. Osteoporosis in men. Endocr Rev. 2008;29:441–464. doi: 10.1210/er.2008-0002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Peacock M, Koller DL, Lai D, Hui S, Foroud T, Econs MJ. Bone mineral density variation in men is influenced by sex-specific and non sex-specific quantitative trait loci. Bone. 2009;45:443–448. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2009.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Khosla S, Melton LJ, III, Atkinson EJ, O’Fallon WM, Klee GG, Riggs BL. Relationship of serum sex steroid levels and bone turnover markers with bone mineral density in men and women: A key role for bioavailable estrogen. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1998;83:2266–2274. doi: 10.1210/jcem.83.7.4924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Rapado A, Hawkins F, Sobrinho L, et al. Bone mineral density and androgen levels in elderly males. Calcif Tissue Int. 1999;65:417–21. doi: 10.1007/s002239900726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Falahati-Nini A, Riggs BL, Atkinson EJ, O’Fallon WM, Eastell R, Khosla S. Relative contributions of testosterone and estrogen in regulating bone resorption and formation in normal elderly men. J Clin Invest. 2000;106:1553–1560. doi: 10.1172/JCI10942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Leder BZ, LeBlanc KM, Schoenfeld DA, Eastell R, Finkelstein JS. Differential effects of androgens and estrogens on bone turnover in normal men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88:204–210. doi: 10.1210/jc.2002-021036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Khosla S, Melton LJ, Atkinson EJ, O’Fallon WM. Relationship of serum sex steroid levels to longitudinal changes in bone density in young versus elderly men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001;86:3555–3561. doi: 10.1210/jcem.86.8.7736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Van Pottelbergh I, Goemaere S, Kaufman JM. Bioavailable estradiol and an aromatase gene polymorphism are determinants of bone mineral density changes in men over 70 years of age. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88:3075–3081. doi: 10.1210/jc.2002-021691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Lapauw B, Taes Y, Goemaere S, Toye K, Zmierczak H-G, Kaufman J-M. Anthropometric and skeletal phenotype in men with idiopathic osteoporosis and their sons is consistent with deficient estrogen action during maturation. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;94:4300–4308. doi: 10.1210/jc.2009-0568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Khosla S, Melton LJ, Riggs BL. Estrogen and the male skeleton. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002;87:1443–1450. doi: 10.1210/jcem.87.4.8417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Mellstrom D, Vandenput L, Mallmim H, et al. Older men with low serum estradiol and high serum SHBG have an increased risk of fractures. J Bone Miner Res. 2008;23:1552–1560. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.080518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Riggs BL, Melton LJ. Medical progress series: Involutional osteoporosis. N Engl J Med. 1986;314:1676–1686. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198606263142605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Smith MR. Androgen deprivation therapy for prostate cancer: new concepts and concerns. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes. 2007;14:247–254. doi: 10.1097/MED.0b013e32814db88c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Lowe H, Shane E. Osteoporosis associated with illnesses and medications. In: Marcus R, Feldman D, Nelson DA, Rosen CJ, editors. Osteoporosis. Elsevier Press; San Diego, CA: 2008. pp. 1283–1314. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Stepan JJ, Lachman M, Zverina J, Pacovsky V, Baylink DJ. Castrated men exhibit bone loss - effect of calcitonin treatment on biochemical indexes of bone remodeling. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1989;69:523–527. doi: 10.1210/jcem-69-3-523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Stoch SA, Parker RA, Chen LP, Bubley G, KOYJ, Vincelette A, Greenspan SL. Bone loss in men with prostate cancer treated with gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001;86:2787–2791. doi: 10.1210/jcem.86.6.7558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Mittan D, Lee S, Miller E, Perez RC, Basler JW, Bruder JM. Bone loss following hypogonadism in men with prostate cancer treated with GnRH analogs. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002;87:3656–3661. doi: 10.1210/jcem.87.8.8782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Shahinian VB, Kuo Y, Freeman JL, Goodwin JS. Risk of fracture after androgen deprivation for prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:154–164. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa041943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Vanderschueren D, Vandenput L, Boonen S, Lindberg MK, Bouillon R, Ohlsson C. Androgens and bone. Endocrine Rev. 2004;25:389–425. doi: 10.1210/er.2003-0003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Bhasin S, Cunningham GR, Hayes FJ, Matsumoto AM, Snyder PJ, Swerdloff RS, Montori VM. Testosterone therapy in adult men with androgen deficiency syndromes: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91:1995–2010. doi: 10.1210/jc.2005-2847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Behre HM, Kliesch S, Leifke E, Link TM, Nieschlag E. Long-term effect of testosterone therapy on bone mineral density in hypogonadal men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1997;82:2386–2390. doi: 10.1210/jcem.82.8.4163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Crawford BA, Liu PY, Kean MT, Bleasel JF, Handelsman DJ. Randomized placebo-controlled trial of androgen effects on muscle and bone in men requiring long-term systemic glucocorticoid treatment. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88:3167–3176. doi: 10.1210/jc.2002-021827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Smith MR, Fallon MA, Lee H, Finkelstein JS. Raloxifene to prevent gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist-induced bone loss in men with prostate cancer: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89:3841–3846. doi: 10.1210/jc.2003-032058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Michaelson MD, Kaufman DS, Lee H, et al. Randomized controlled trial of annual zoledronic acidto prevent gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist-induced bone loss in men with prostatz cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:1038–1042. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.07.3361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Greenspan SL, Nelson JB, Trump DL, Resnick NM. Effect of once weekly oral alendronate on bone loss in men receiving androgen deprivation therapy for non-metastatic prostate cancer. Ann Intern Med. 2007;146:416–424. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-146-6-200703200-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Kaufman JM, Vermeulen A. The decline of androgen levels in elderly men and its clinical and therapeutic implications. Endocrine Rev. 2005;26:833–876. doi: 10.1210/er.2004-0013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Isidori AM, Giannetta E, Greco EA, Gianfrilli D, Bonifacio V, Isidori A, Lenzi AFabbri A. Effects of testosterone on body composition, bone metabolism and serum lipid profile in middle-aged men: a meta analysis. Clin Endocrinol (oxford) 2005;63:280–293. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2005.02339.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Snyder PJ, Peachey H, Hannoush P, Berlin JA, Loh I, Holmes JH, Dlewati A, Staley J, Santanna J, Kapoor SC, Attie MF, Haddad JG, Jr, Strom BL. Effect of testosterone treatment on bone mineral density in men over 65 years of age. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1999;84:1966–1972. doi: 10.1210/jcem.84.6.5741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Amory JK, Watts NB, Easley KA, Sutton PR, Anawalt BD, Matsumoto AM, Bremner WJ, Tenover JL. Exogenous testosterone or testosterone with finasteride increases bone mineral density in older men with low serum testosterone. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89:503–510. doi: 10.1210/jc.2003-031110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Fernandez-Balsells MM, Murad MH, Lane M, et al. Adverse efects of testosterone therapy in adult men: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95:2560–2575. doi: 10.1210/jc.2009-2575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Basaria S, Coviello AD, Travison TG, et al. Adverse events associated with testosterone administration. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:109–122. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1000485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Wang C, Nieschlag E, Swerdloff R, Behre HM, Hellstrom WJ, Gooren LJ, Kaufman JM, Legros JJ, Lunenfeld B, Morales A, Morley JE, Schulman C, Thompson IM, Weidner W, Wu FC. Investigation, treatment and monitoring of late-onset hypogonadism in males: ISA, ISSAM, EAU, EAA and ASA recommendations. Eur J Endocrinol. 2008;159:507–14. doi: 10.1530/EJE-08-0601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]