Abstract

Background

Select retrotransposons in the long terminal repeat (LTR) class exhibit interindividual variation in DNA methylation that is altered by developmental environmental exposures. Yet, neither the full extent of variability at these “metastable epialleles,” nor the phylogenetic relationship underlying variable elements is well understood. The murine metastable epialleles, Avy and CabpIAP, result from independent insertions of an intracisternal A particle (IAP) mobile element, and exhibit remarkably similar sequence identity (98.5%).

Results

Utilizing the C57BL/6 genome we identified 10802 IAP LTRs overall and a subset of 1388 in a family that includes Avy and CabpIAP. Phylogenetic analysis revealed two duplication and divergence events subdividing this family into three clades. To characterize interindividual variation across clades, liver DNA from 17 isogenic mice was subjected to combined bisulfite and restriction analysis (CoBRA) for 21 separate LTR transposons (7 per clade). The lowest and highest mean methylation values were 59% and 88% respectively, while methylation levels at individual LTRs varied widely, ranging from 9% to 34%. The clade with the most conserved elements had significantly higher mean methylation across LTRs than either of the two diverged clades (p = 0.040 and p = 0.017). Within each mouse, average methylation across all LTRs was not significantly different (71%-74%, p > 0.99).

Conclusions

Combined phylogenetic and DNA methylation analysis allows for the identification of novel regions of variable methylation. This approach increases the number of known metastable epialleles in the mouse, which can serve as biomarkers for environmental modifications to the epigenome.

Keywords: Epigenetics, DNA methylation, Metastable epiallele, Phylogeny, Transposon, Mouse

Background

Across mammalian genomes, the retrotransposon class of repeat elements make up nearly half the nuclear DNA, with long terminal repeats (LTRs) alone accounting for 8-10% [1]. Many retrotransposons retain the ability to move (transpose) to new locations in the genome, a potentially deleterious phenomenon that can result in direct disruption to coding regions [2,3]. Therefore, the suppression of retrotransposons is vital to organismal survival, particularly through sensitive life stages, and is primarily accomplished via epigenetic mechanisms, including DNA methylation [4,5]. Epigenetic suppression is typically established early in development at the blastocyst stage and maintained during differentiation of the primordial germ cells [6]. Importantly, in certain cases suppression is incomplete, leading to adverse consequences [7]. Alternatively, this incomplete suppression may be an evolutionarily selected method of fine-tuning gene expression [8]. Genome-wide, little is known about the extent to which interindividual variation of DNA methylation at these elements is affected by environmental factors and/or their phylogenetic lineage [9].

Intracisternal A particles (IAP) are a class of murine retrotransposons named for the appearance of budding doughnut shaped particles in the cisternae of the endoplasmic reticulum [10]. IAPs are members of the endogenous retrovirus family (ERV) class II [11]. Structurally, a full length IAP consists of gag, pro, and pol genes capped at each end by a direct pair of LTRs, each approximately 350 bp in length [12]. However, the largest majority of IAP transcripts issue from truncated 5.4 kb copies of IAP of subtype IΔ1 rather than full length 7.2 kb copies [13]. Previous work has identified only a subset of elements likely to be active, due to genomic position, sequence mutation, or methylation status [13]. The number of paralogous IAP LTRs in the genome has been uncertain with estimates ranging from less than 1000 to over 9000 with significant polymorphism among strains [10,14,15]. This family of ERVs is highly active and rapidly transposing, with estimates of 60% of elements being strain specific [15]. It is advantageous for these mobile elements to be kept under tight control by heavy DNA methylation and tight chromatin structure.

A small number of “metastable epialleles” have been identified in mice (e.g. Avy, CabpIAP, and AxinFu) in which variable methylation of the 5′ LTR of an antisense IAP insertion results in dysregulation of gene expression concomitant with the level of methylation [16-20]. Metastable epialleles show variable expression among individuals with epigenetic profiles that are consistent across tissues and are thus likely to have been set prior to germ line differentiation [21-23]. Further, the distribution of variable expressivity has been shifted at these metastable epialleles following maternal exposure to nutritional and environmental factors [21,22,24,25]. To date, no studies have determined the genetic relationship underlying the ability of these IAP LTRs to be variably methylated. Two of the epialleles, Avy and AxinFu, were identified due to dramatic phenotypes induced by their insertion into nearby protein-coding genes [18,26]. Conversely, CabpIAP was identified by a search of Genbank cDNA databases for chimeric sequence containing IAP LTR and genic sequence [20].

To systematically investigate the relationship of genetics and metastability we applied phylogenetic methods to identify candidate IAP retrotransposons and validate their variable methylation status. Through this approach, we find the phylogeny of metastable loci sheds light on the evolutionary basis of metastability. Additionally, the validated analysis of epigenetic state across individual isogenic mice now increases the number of known metastable epialleles, which can serve as a test panel for environmental modifications to the epigenome.

Results

IAP distribution in the genome

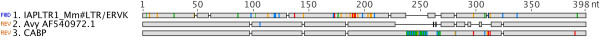

Initial pairwise alignment of the two most well-studied metastable epialleles, Avy and CabpIAP revealed that the LTRs of these two insertions exhibit 98.5% sequence identity over the length of shared sequence (Figure 1). RepeatMasker was used to scan the C57BL/6 (mm9) mouse genome and identified 10802 IAP LTR elements. The majority of these LTRs were pairs found on the 5’ and 3’ end of the same IAP insertion, however a fraction were present as solo LTRs. Since the IAPs underlying both Avy and CabpIAP are of the class IΔ1, type IAPLTR1_Mm as identified in RepBase, this subtype was used to filter the complete list of transposons, resulting in a total list of 1388 IAPLTR1_Mm elements after removing 65 unmapped, short, or non-alignable elements. There was no bias in the orientation of insertion as 691 sense and 707 anti-sense IAPLTR1_Mm elements were identified throughout the genome.

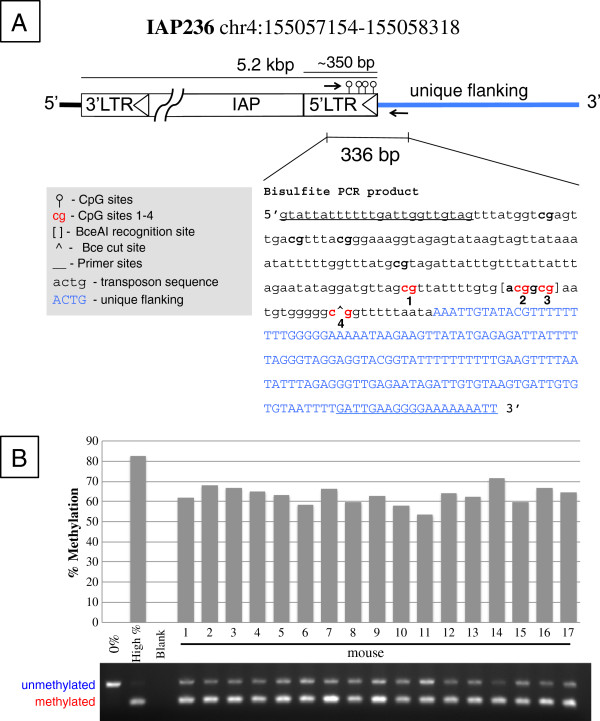

Figure 1.

Multiple sequence alignment. The sequence of the Avy and CabpIAP LTR insertions are compared to the IAPLTR1_Mm consensus sequence. Avy shares 98.5% sequence identity with CabpIAP (85% sequence identity over the length of CabpIAP). Colors indicate base changes from consensus (A = red, T = blue, C = yellow, G = green).

Phylogenetic similarity of known metastable IAPs

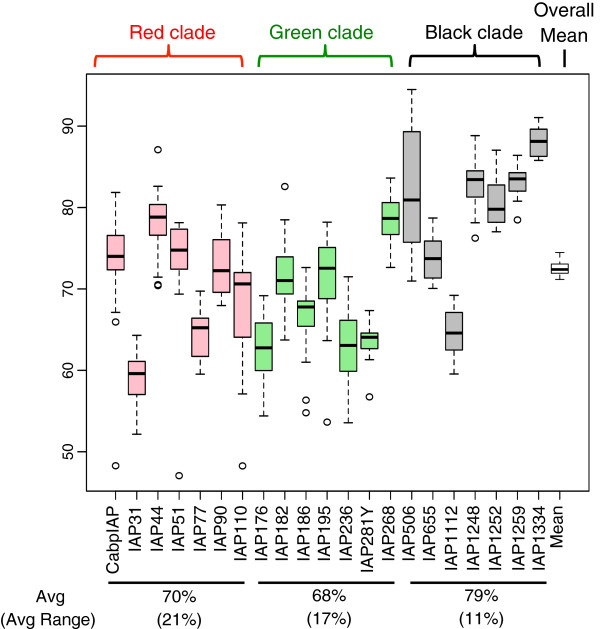

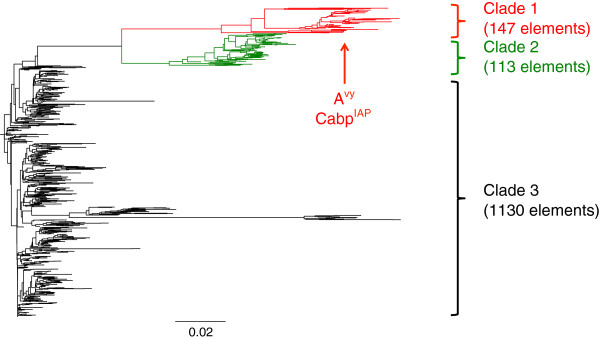

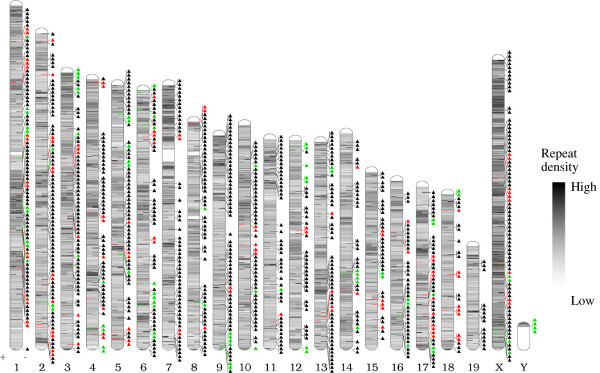

A neighbor-joining tree of these 1388 elements revealed three distinct clades with Avy and CabpIAP clustering within clade 1 (red), more closely than 99% of all other elements (Figure 2). The largest cluster, clade 3 (black), contains the most conserved elements, and consists of 1130 sequences with an average sequence divergence of only 1.8% from the consensus. Clade 1 (red) and clade 2 (green) contain 147 and 113 elements each, and are more divergent, with 9.1% and 12.9% average differences from the consensus respectively. Bias in location of these insertions was not identified, with members of each clade represented across numerous chromosomes and locations (Figure 3). Unique identifiers were assigned to each element in our list, in the format IAP27-IAP1414, used throughout the study.

Figure 2.

Neighbor-joining tree. Illustrated are 1388 IAPLTR_Mm elements drawn from the C57BL/6 genome and including Avy and CabpIAP elements for a total of 1390. Subclades are highlighted in red (clade 1) and green (clade 2), with the remaining elements in black (clade 3). The bifurcation of subclades 1 and 2 demonstrates duplication and divergence events followed by rapid radiation of these subfamilies. Scale bar indicates number of nucleotide substitutions per site.

Figure 3.

IAP element insertions. The 1388 insertions of IAPLTR1_Mm are plotted against their genomic location. The color of the clade corresponding to the insertion’s position on the phylogenetic tree is highlighted to the right of each chromosome. Elements from each clade in the tree are found dispersed throughout the genome. The color scale internal to the chromosomes corresponds to overall repetitive element density.

Characterization of interindividual metastability

From these candidates 7 from each clade were randomly selected to test for variable methylation using combined bisulfite and restriction analysis (CoBRA). Primers for CoBRA were designed with the forward primer internal to the IAP sequence and the reverse primer located in the flanking sequence (Figure 4A), providing an amplicon specific to an insertion and containing homologous IAP element sequence (Table 1). BceAI enzyme was chosen since each element contains two CpG sites as part of a BceAI restriction site, ACGGCG. Loss of methylation at either or both would prevent BceAI activity. Consequently, the relative intensity of cut vs. uncut bands gives a semi-quantitative measurement of methylation at these sites (Figure 4A). Uncut bands correspond to unmethylated DNA while cut bands correspond to methylated DNA. The two CpG sites examined here exhibited interindividual variation in previous studies from our group [24,27], and are identified as sites 2 and 3 in this study. A quantitated CoBRA gel image of IAP236 is depicted in Figure 4B, revealing an 18% range of methylation at the cut site.

Figure 4.

CoBRA design. For each candidate locus we amplify a portion of the antisense strand of the 5′ LTR and unique flanking sequence (arrows) containing a BceAI recognition site. (A) The product of IAP236 is shown with cut sites and CpGs indicated by numbers 1–4. Sites 2 and 3 are conserved in all candidate loci and cut. PCR primers are underlined. (B) Percent methylation is derived from relative intensity of the cut vs. uncut bands. This locus exhibits an 18% range in variable methylation. Controls are shown in lanes 1 and 2, indicating the specificity and completeness of the digestion.

Table 1.

PCR primers and conditions for CoBRA analysis

| IAP | Clade | Position | Forward primer | Reverse primer | Nearest gene | Distance | Cycles | Temperature (°C) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CabpIAP |

1 (red) |

chr2:154179911-154180159 |

ATTATTTTTTGATTGGTTGTAGTTTATGG |

CACCAACATACAATTAACA |

Cdk5rap1 |

intron |

39 |

47 |

| iap31 |

1 (red) |

chr1:89356306-89357454 |

TAAGAAGTAAGAGAGAGAAGTAA |

CCAAACAAATCCAAAAACCTAA |

- |

- |

45 |

52 |

| iap44 |

1 (red) |

chr10:77413077-77414228 |

GGTTAGGAAGAATATAATAATTAG |

CTAAAAATAAAACCCAAAAACCC |

Trpm2 |

Intron |

45 |

52 |

| iap51 |

1 (red) |

chr12:53835543-53836696 |

GGGAAAAATAGAGTATAAGTAG |

TCTAACAACTACCCACAAAAAAT |

Akap6 |

Intron |

40 |

52 |

| iap77 |

1 (red) |

chr17:64098002-64099153 |

AAGTAAGAGAGAGAGAAAAT |

TATAACCCCCAAATAACTAACAT |

- |

- |

45 |

52 |

| iap90 |

1 (red) |

chr18:47812857-47814008 |

GGGAAAAATAGAGTATAAGY |

CACTAAAAACAACAATCTAACAAC |

Gm5095 |

Intron |

43 |

52 |

| iap110 |

1 (red) |

chr2:72112889-72114056 |

AAGTAAGAGAGAGTAAGAAGTAA |

CATATACAACACTTAAAACAAAACC |

Rapgef4 |

18 kb upstream |

45 |

52 |

| iap176 |

2 (green) |

chr1:127212941-127214106 |

TTTATATTTTTGGGAGTTAGG |

AACACTCTTCTACAATAACATCT |

- |

- |

40 |

52 |

| iap182 |

2 (green) |

chr1:26288894-26290059 |

TGTTTATATTTTTGGGAGTTAG |

AACCTACTTCATCTTAAAAC |

- |

- |

45 |

52 |

| iap186 |

2 (green) |

chr10:24567718-24568883 |

GTATTATTTTTTGATTGGTTGTAG |

AAACCCACTAATTCTTCCTAT |

Enpp3 |

12 kb upstream |

40 |

52 |

| iap195 |

2 (green) |

chr12:25079835-25080998 |

TTGTTTATATTTTTGGGAGT |

CACCTTATATTCTCCAAAAAAAC |

- |

- |

40 |

52 |

| iap236 |

2 (green) |

chr4:155057154-155058318 |

GTATTATTTTTTGATTGGTTGTAG |

AATTTTTTTCCCCTTCAATC |

Mib2 |

15 kb upstream |

45 |

52 |

| iap268 |

2 (green) |

chr9:123106561-123107725 |

TTTATATTTTTGGGAGTTAGG |

ACACCTAACATCATCTAAAT |

Cdcp1 |

Intron |

45 |

52 |

| iap281y |

2 (green) |

chrY:2136760-2137925 |

GGTTAGGAAGAATATTATAGA |

TACACCAAAAACAAACCAAA |

Rbmy1a1 |

8 kb downstream |

45 |

52 |

| iap506 |

3 (black) |

chr12:74416066-74417247 |

AGTAAGAAGTAAGAGAGTAAGAA |

CTACACCCCAAAAATAATAAAAAC |

Slc38a6 |

Intron |

45 |

52 |

| iap655 |

3 (black) |

chr15:11992027-11993248 |

AGAGAAAAGTAAGAGAGAGAAAA |

AAAACAAAAAAAACTACACCC |

- |

- |

45 |

52 |

| iap1112 |

3 (black) |

chr6:101092968-101094168 |

TAAGAGAGAGAGAAAAGTAAGAGA |

CCACCAAAATAAAAACTCAAAAC |

Pdzrn3 |

6 kb downstream |

43 |

52 |

| iap1248 |

3 (black) |

chr8:63849572-63850723 |

TTTTTAGGAGTTAGAGTGTA |

CTCCTTTCTAATTTTATTCTCCA |

Sh3rf1 |

Intron |

45 |

53 |

| iap1252 |

3 (black) |

chr8:47435363-47436559 |

AGAAAAAGTAAGAGAGAGAGAAA |

AACCCTAAAATTCCTCAAAAAAC |

Helt |

56 kb upstream |

40 |

54 |

| iap1259 |

3 (black) |

chr8:8319882-8321071 |

AAGAAGTAAGAGAGTAAGAAGTAA |

ACAAAAAATCAACTAAACTCTAC |

- |

- |

45 |

53 |

| iap1334 | 3 (black) | chr9:121236806-121238001 | AAGTAAGAGAGAGAGAAAAGTAA | RACTACTACTAAAAACCCACAA | Trak1 | Intron | 40 | 54 |

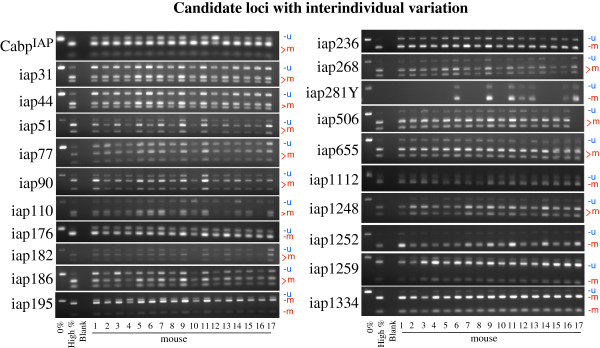

A group of 17 isogenic Avy/a genotype mice of both genders (N = 7 males and N = 10 females) from 7 litters was sacrificed at weaning and DNA was extracted from the liver. Following bisulfite conversion, candidate regions were amplified via PCR and digested with BceAI (Figure 5). A total of 21 representative loci, 7 from the red clade including CabpIAP, and 7 each from the green and black clades were evaluated. The 0% control (lane 1) was uncut in all loci, while the high percent methylated control was nearly completely digested in all loci (lane 2) indicating sufficient enzyme activity and specificity.

Figure 5.

Candidate loci with interindividual variation. DNA from 17 isogenic mouse livers at d21 was isolated and bisulfite converted. Amplification and digestion of 21 representative IAP elements show variable levels of methylation per locus and mouse. Upper bands indicate uncut PCR product corresponding to the unmethylated BceAI site. Lower bands indicate a fully methylated BceAI site consisting of CpGs 2 and 3 from Figure 4. Locus 281Y is located on the Y chromosome and is therefore amplified only from male animals.

The mean methylation across all mice for all IAP insertions was 72.5% and no mouse deviated by more than 3% (range 71-74%), showing no statistical difference (p > 0.99) (Table 2). Specific loci however, exhibited much greater variability. We found that mean methylation of individual IAPs fluctuated from a low of 59% to a high of 88% and standard deviations varied from 1.9 to 7.3, indicating that individual transposons can differ dramatically in both average value and standard deviation among mice. Thus, methylation variability ranged from 9% for the least variable element to greater than 34% for the most variable element. There were no significant differences in methylation between sexes. Importantly, the average methylation was significantly lower for both red clade elements, 70% (p = 0.017), and green clade elements, 68% (p = 0.040) than for black clade elements, 79%. Interestingly, the range through which a particular element can be methylated is also correlated with its position within the phylogenetic tree (Figure 6). The average range for red clade elements is 21%, 17% for green clade elements, and just 11% for black clade elements. The element with the greatest range is in the red clade (CabpIAP) while the element with the greatest dispersion as measured by interquartile range is found in the black clade (IAP506).

Table 2.

CoBRA quantitated percent methylation across 17 mice and 21 IAP elements

| |

Red clade |

Green clade |

Black clade |

|

||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CabpIAP | IAP31 | IAP44 | IAP51 | IAP77 | IAP90 | IAP110 | IAP176 | IAP182 | IAP186 | IAP195 | IAP236 | *IAP281Y | IAP268 | IAP506 | IAP655 | IAP1112 | IAP1248 | IAP1252 | IAP1259 | IAP1334 | Average | |

| Mouse 1 |

74 |

52 |

70 |

77 |

60 |

80 |

71 |

69 |

70 |

61 |

70 |

62 |

|

77 |

77 |

76 |

66 |

LOD |

83 |

82 |

88 |

72 |

| Mouse 2 |

77 |

60 |

77 |

75 |

60 |

71 |

72 |

60 |

71 |

68 |

76 |

68 |

|

84 |

86 |

70 |

69 |

83 |

77 |

78 |

86 |

73 |

| Mouse 3 |

81 |

57 |

77 |

78 |

66 |

76 |

72 |

66 |

74 |

55 |

73 |

67 |

|

76 |

71 |

76 |

68 |

84 |

78 |

84 |

LOD |

72 |

| Mouse 4 |

72 |

61 |

80 |

77 |

65 |

68 |

69 |

56 |

77 |

56 |

54 |

65 |

|

73 |

82 |

70 |

60 |

89 |

80 |

81 |

86 |

71 |

| Mouse 5 |

74 |

59 |

71 |

78 |

61 |

80 |

75 |

65 |

70 |

69 |

69 |

63 |

|

80 |

81 |

70 |

LOD |

76 |

78 |

82 |

90 |

73 |

| Mouse 6 |

76 |

57 |

78 |

74 |

65 |

73 |

71 |

63 |

64 |

67 |

76 |

58 |

64 |

77 |

94 |

76 |

63 |

78 |

LOD |

85 |

86 |

72 |

| Mouse 7 |

66 |

62 |

80 |

75 |

61 |

73 |

78 |

54 |

67 |

65 |

64 |

66 |

|

75 |

75 |

74 |

60 |

85 |

78 |

82 |

86 |

71 |

| Mouse 8 |

76 |

60 |

75 |

78 |

62 |

72 |

64 |

63 |

71 |

65 |

73 |

60 |

|

78 |

93 |

70 |

62 |

81 |

79 |

84 |

LOD |

72 |

| Mouse 9 |

67 |

62 |

83 |

73 |

64 |

70 |

67 |

69 |

75 |

69 |

74 |

63 |

67 |

76 |

76 |

74 |

68 |

87 |

83 |

86 |

86 |

73 |

| Mouse 10 |

82 |

62 |

80 |

47 |

68 |

69 |

57 |

57 |

78 |

73 |

65 |

58 |

|

82 |

92 |

79 |

60 |

84 |

82 |

81 |

91 |

72 |

| Mouse 11 |

70 |

60 |

87 |

69 |

65 |

71 |

73 |

65 |

70 |

68 |

72 |

54 |

64 |

80 |

76 |

73 |

63 |

87 |

87 |

84 |

90 |

73 |

| Mouse 12 |

48 |

61 |

77 |

70 |

66 |

71 |

57 |

63 |

74 |

71 |

76 |

64 |

61 |

84 |

94 |

75 |

64 |

81 |

82 |

81 |

89 |

72 |

| Mouse 13 |

79 |

64 |

81 |

73 |

64 |

69 |

66 |

67 |

69 |

68 |

75 |

62 |

64 |

80 |

81 |

72 |

66 |

LOD |

77 |

84 |

86 |

72 |

| Mouse 14 |

79 |

58 |

79 |

72 |

68 |

76 |

57 |

63 |

69 |

68 |

78 |

71 |

|

79 |

82 |

77 |

69 |

84 |

84 |

84 |

90 |

74 |

| Mouse 15 |

74 |

55 |

80 |

75 |

68 |

74 |

71 |

60 |

72 |

66 |

71 |

60 |

|

81 |

80 |

71 |

64 |

83 |

84 |

85 |

89 |

73 |

| Mouse 16 |

73 |

56 |

81 |

71 |

70 |

69 |

48 |

60 |

83 |

71 |

75 |

67 |

57 |

83 |

74 |

73 |

66 |

82 |

79 |

85 |

88 |

72 |

| Mouse 17 |

76 |

59 |

71 |

78 |

62 |

78 |

72 |

66 |

66 |

67 |

68 |

65 |

65 |

78 |

LOD |

77 |

65 |

82 |

79 |

83 |

91 |

72 |

| mean |

73 |

59 |

78 |

73 |

64 |

73 |

67 |

63 |

72 |

66 |

71 |

63 |

63 |

79 |

82 |

74 |

65 |

83 |

81 |

83 |

88 |

72 |

| median |

74 |

60 |

79 |

75 |

65 |

72 |

71 |

63 |

71 |

68 |

73 |

63 |

64 |

79 |

81 |

74 |

65 |

83 |

80 |

84 |

88 |

72 |

| stdev |

8 |

3 |

4 |

7 |

3 |

4 |

8 |

4 |

5 |

5 |

6 |

4 |

3 |

3 |

8 |

3 |

3 |

3 |

3 |

2 |

2 |

1 |

| min |

48 |

52 |

70 |

47 |

60 |

68 |

48 |

54 |

64 |

55 |

54 |

54 |

57 |

73 |

71 |

70 |

60 |

76 |

77 |

78 |

86 |

71 |

| max |

82 |

64 |

87 |

78 |

70 |

80 |

78 |

69 |

83 |

73 |

78 |

71 |

67 |

84 |

94 |

79 |

69 |

89 |

87 |

86 |

91 |

74 |

| range | 34 | 12 | 17 | 31 | 10 | 12 | 30 | 15 | 19 | 18 | 25 | 18 | 11 | 11 | 24 | 9 | 10 | 13 | 10 | 8 | 5 | 3 |

* IAP located on the Y chromosome, only measured in male animals.

LOD = Limit of Detection.

Figure 6.

Boxplot of methylation values. Interindividual variation in each IAP correlates with phylogenetic clade. Average methylation values are lower for red and green clades (70% and 68%) than for the black clade (79%) suggesting higher methylation for older insertions. The average range per clade, in parentheses, is also lower, however the standard deviation is similar across clades.

Discussion

Our bioinformatic analysis identified 10802 IAP LTRs, consistent with recent estimates of ~5400 IAP transposons in the mouse genome as the vast majority of detected insertions in our analysis were paired on either end of a single IAP insertion [15,28]. To validate candidate LTRs as metastable, we focused primarily on sequences of the specific subtype of IAP known in two cases to be variably methylated (IAPLTR1_Mm). Both the Avy and CabpIAP epialleles exhibit variable DNA methylation at specific CpG sites, which can be influenced by developmental environmental exposure [24]. Phylogenetic analysis revealed that both epialleles clustered in one of two divergent subclades in the IAPLTR1_Mm family. Combined bisulfite and restriction analysis performed on 20 additional loci found interindividual methylation to be a common feature of all elements in this family. Though the degree of variation ranged from 9% to 34% among elements within each mouse, average methylation across all LTRs varied only 3%, a confirmation that global methylation of repetitive loci does not necessarily reflect locus specific deviation. Interestingly, on average, IAP methylation was higher and less variable in the more numerous, phylogenetically conserved elements (black clade 3). While the standard method of dating LTR insertions by measuring accumulated mutations in the 5′ and 3′ LTRs is inapplicable in this case because of their young age, the percent divergence from consensus strongly suggests the two derived subclades are younger. The increased methylation of the older IAPs here fits with the evidence of Reiss et al. who found a positive correlation of age with methylation in another family of ERVs, the Early Transposon (ETn) class and hypothesized this would be a general finding in ERVs [29].

Though retrotransposons, including IAPs, are generally highly methylated, important windows of vulnerability exist in which genomic methylation is globally reprogrammed [4,6,21]. Reactivation during genomic reprogramming is likely responsible for the frequent germ line insertion in this lineage of IAPs in rodents, counterbalanced by selective pressure to maintain epigenetic silencing in somatic cells [17]. The presence of two diverged clades in our phylogeny suggests that the ancestor of the Avy and CabpIAP alleles at two times collected advantageous mutations that allowed it to escape genomic control and proliferate successfully throughout the genome following the master gene model [30]. Their genomic distribution also suggests that they retained retrotranspositional activity after divergence, a finding also supported previously [15].

Epigenomic studies are increasingly cataloging variation across tissues, disease states, ages, and environmental exposures. It is therefore important to understand the baseline naturally extant variation in a population of isogenic, unexposed, age-matched animals and to provide assays to detect shifts in variation mediated by other conditions. Determination of interindividual variation in DNA methylation has followed a number of methods, including coat color shifts in Avy mice [27], bisulfite sequencing, northern blots for transcript quantity [31], methylation specific PCR, and pyrosequencing [32]. The method we use here, combined bisulfite and restriction analysis (CoBRA), exploits site-specific enzyme digestion to determine methylation status. Advantages of CoBRA include semi-quantitative analysis, and relatively inexpensive costs, thereby facilitating the high throughput necessary for epidemiological testing. Indeed, CoBRA has been used to assess the epigenotype of colorectal tumors, providing direct health implications [33]. Additionally, automation platforms such as the QIAxel system (Qiagen Inc., Valencia, CA) would increase the speed of sample quantitation after enzyme digestion. Our candidate loci were also mined from the C57BL/6 genome, and as such, they are more likely to be useful as epigenetic markers in both mutant and exposed mice than previous epialleles (Avy and AxinFu), which are restricted to specific lines.

Previous studies utilizing non-phylogenetic methods of variably methylated candidate identification have identified retroelements co-located with active histone modification (H3K4me3) [34]. Further, IAPs, unlike other transposons, can induce changes in nearby chromatin marks, but no phylogenetic basis underlying epigenetic states has been explored [2]. The close sequence identity of Avy and CabpIAP insertions may be associated structurally with directed epigenetic modifications by targeting enhanced recruitment of trans factors governing their metastability. Alternatively, high sequence similarity in the divergent clades may have resulted from very recent mobilization and high activity of the parent element and its rapid proliferation. We speculate that variable DNA methylation, being a general property of elements we tested from these clades, explains both the success of this lineage in duplication, and their interindividual variation. This hypothesis is borne out by the average methylation being higher in the black clade, containing the largest number, most conserved, and likely oldest, elements. Though in general, new insertions are considered deleterious, some have been co-opted by the genome as a mechanism of driving gene expression, and epigenetically labile insertions may be under selection to “fine tune” that expression [35]. Our analysis supports the notion that mutation to escape genomic control is correlated with both increased retrotranspositional activity and decreased methylation. Consequently, these data are a strong indication that interindividual variation in methylation at repetitive elements is the default condition, rather than a rare occurrence, and that shifts in methylation profiles could affect numerous transcripts in the genome. Thus, environmental exposures capable of altering the epigenome could potentially have widespread effects for gene regulation.

Conclusions

Combined phylogenetic and DNA methylation analysis resulted in the identification of novel regions of variable methylation. The phylogenetic analysis revealed two duplication and divergence events subdividing this family into three clades. Importantly, average methylation was significantly lower for both the red and green clade elements, compared to black clade elements, supporting the notion that phylogenetically older and more uniform elements tend to be more highly methylated than younger and diverged elements. Thus, through this endeavor the number of known metastable epialleles in the mouse has dramatically increased. These sites can now serve as biomarkers for environmental modifications to the epigenome. Parallel approaches in humans are underway.

Methods

Computational analysis

For the Avy allele, the LTR studied was obtained from Genbank accession number [GenBank:AF540972.1], position 10–345. For CabpIAP, the LTR sequence was obtained from [GenBank:AL732601.16], position 179834–180227. For CoBRA and pyrosequencing analysis, four CpG sites were referenced from the Avy allele coordinates, [GenBank:AF540971.1], positions 365, 378, 380, and 393. These are annotated as positions 1–4 in this report.

Mouse genome version 37.61(mm9, 2007) was downloaded from NCBI and scanned with a local installation of RepeatMasker version open-3.3.0 http://www.repeatmasker.org using the RMblast engine http://www.repeatmasker.org/RMBlast.html with the following parameters, “RepeatMasker -xsmall -s -species mouse”. The repeat database was obtained from RepBase release 20090604 http://www.girinst.org[36]. The output was filtered for elements annotated as IAPLTR and counted to 10802. Since each IAP element contains two LTRs, this represents approximately 5000 full-length IAP elements of all subtypes. We next filtered for elements of type IΔ1, subtype IAPLTR1_Mm and removed non-chromosomal elements and 40 short elements below 330 bp. The resulting dataset contained 707 elements on the sense strand and 691 on the complementary strand (Additional file 1: Table S1). A further 10 elements were removed for lack of alignment to the IAPLTR1_Mm consensus. Alignment was performed by Geneious software version 5.6.5 http://www.geneious.com/ using the Geneious alignment algorithm with default parameters (cost matrix = 65% similarity, gap open penalty = 12, gap extension penalty = 3). The phylogenetic tree was built using neighbor-joining, no outgroup, Jukes-Cantor genetic distance model. Bootstrap of 1000 iterations showed no substantial differences in the divergence of the major clades (data not shown).

Genomic sequence for each element (for alignment and tree building) and 400 bp of flanking sequence (for primer design) was obtained by submission of the RepeatMasker generated coordinates to the Galaxy Project https://main.g2.bx.psu.edu/[37]. Unique numbers were assigned to each IAP here to aid in reference and used throughout the study (Additional file 1: Table S1). A second alignment was performed with flanking sequence to select all sites with 5’ LTR sequence, complete IAP structure, and 3’ LTR sequence. Removal of duplicate entries that matched to the 3’ LTR copy and other LTRs with repetitive flanking sequence resulted in a total of 366 candidate elements for CoBRA [38,39]. All primers were designed to amplify the antisense strand of the 5’ LTR and proximal flanking sequence (Table 1).

DNA extraction and conversion

Mice were obtained from a forced heterozygous colony carrying the Avy allele that has been maintained with sibling mating for over 220 generations, resulting in a genetically invariant background initially based upon the C3H strain [21]. Virgin wild-type dams, 6 weeks of age, were fed phytoestrogen free AIN-93 G diets (diet 95092 with 7% corn oil substituted for 7% soybean oil; Harlan Teklad, Madison, WI) and were mated. Avy/a offspring were sacrificed at d21 and livers flash frozen for DNA extraction. A total of 17 animals (N = 7 males and N = 10 females) and some sets of littermates were used for this study. DNA extraction was performed using a standard Phenol-Chloroform protocol. Using the Qiagen Epitect kit automated on the Qiagen QIAcube® purification system, approximately 1 μg of genomic DNA was treated with sodium bisulfite. The treatment converts unmethylated cytosines to uracil, read as thymine during polymerase chain reaction (PCR), whereas the methylated cytosines are protected and remain unconverted [40].

Animals used in this study were maintained in accordance with the Guidelines for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (Institute of Laboratory Animal Resources, 1996) and were treated humanely and with regard for alleviation of suffering. The study protocol was approved by the University of Michigan Committee on Use and Care of Animals.

Combined bisulfite restriction analysis

CoBRA [39] was performed with enzyme BceAI (New England Biolabs®) using the following conditions for PCR: 50 ng DNA, 0.5 μl each forward and reverse primer at 10pM/μl concentration, 15 μl HotStarTaq master mix (Qiagen Inc., Valencia, CA), 3 μl Rediload™ (Invitrogen Inc., Grand Island, NY), 10 μl water for a total of 30 μl reaction volume. The reaction was run at 52°C annealing temperature for 45 cycles on a C1000 Bio-Rad thermal cycler pcr machine (Hercules, CA). Some reactions were run with altered conditions (Table 1). Enzyme digestion was performed according to manufacturer protocol, briefly, 10 μl of PCR product, 3 μl BSA (10×), 3 μl Rediload™, 3 μl NEB buffer 3 (10×), 1 μl BceAI enzyme (1 Unit), and 10 μl of water were combined for a 30 μl reaction and incubated at 37°C for 8 hours, followed by 65°C for 20 minutes and run out on a 2% agarose gel. Gels were visualized on a Gel Doc XR™ by Bio-Rad. Image quantitation was performed with Quantity One version 4.6.7 using default options (all lanes, auto detect = yes, normalize = yes, sensitivity = 10, size scale = 5) and reporting relative quantity of each band per lane. Lanes with top bands too faint for detection were considered below the limit of detection (LOD) and removed from further analysis (marked as blank in Table 2). Statistical analysis to determine significance of clade methylation differences was performed using SPSS (IBM, New York, NY) by ANOVA with multiple comparisons Tukey adjustment.

Control DNA was generated in-house by whole genome amplification using the GenomePlex® kit (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) for 0% methylated DNA and by CpG methylase, M.SssI treatment (Zymo Research, Irvine CA) for highly methylated control, both according to manufacturer protocols.

Abbreviations

IAP: Intracisternal A particle; LTR: Long terminal repeat; Avy: Viable yellow agouti; CabpIAP: CDK5 activator binding protein, IAP insertion; CoBRA: Combined bisulfite and restriction analysis; PCR: Polymerase chain reaction; LOD: Limit of detection.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

CF and DCD conceived the study. CF carried out the repeat masking, sequence alignment, and tree building. CF and AB performed the DNA extraction, conversion, primer design, and CoBRA testing. CF, AB, and DCD performed data analysis. CF and AB were responsible for animal husbandry. CF and AB drafted the manuscript and created the figures with editorial guidance from DCD. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Supplementary Material

Table S1. IAPLTR1_Mm elements derived from the mm9 genome.

Contributor Information

Christopher Faulk, Email: faulkc@umich.edu.

Amanda Barks, Email: akbarks@umich.edu.

Dana C Dolinoy, Email: ddolinoy@umich.edu.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by NIH grant ES017524, University of Michigan NIEHS/EPA Children’s Environmental Health Formative Center P20 ES018171/RD83480001, and the University of Michigan National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS) Core Center P30 ES017885. Support for CF was provided by Institutional Training Grant T32 ES007062. The authors declare no conflict of interests.

References

- McCarthy EM, McDonald JF. Long terminal repeat retrotransposons of Mus musculus. Genome Biol. 2004;5:R14. doi: 10.1186/gb-2004-5-3-r14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rebollo R, Karimi MM, Bilenky M, Gagnier L, Miceli-Royer K, Zhang Y, Goyal P, Keane TM, Jones S, Hirst M. et al. Retrotransposon-induced heterochromatin spreading in the mouse revealed by insertional polymorphisms. PLoS Genet. 2011;7:e1002301. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rebollo R, Romanish MT, Mager DL. Transposable elements: an abundant and natural source of regulatory sequences for Host genes. Annu Rev Genet. 2012;46:21–42. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genet-110711-155621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faulk C, Dolinoy DC. Timing is everything: the when and how of environmentally induced changes in the epigenome of animals. Epigenetics. 2011;6:791–797. doi: 10.4161/epi.6.7.16209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoder JA, Walsh CP, Bestor TH. Cytosine methylation and the ecology of intragenomic parasites. Trends Genet. 1997;13:335–340. doi: 10.1016/S0168-9525(97)01181-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lees-Murdock DJ, Walsh CP. DNA methylation reprogramming in the germ line. Epigenetics. 2008;3:5–13. doi: 10.4161/epi.3.1.5553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolinoy DC, Weidman JR, Jirtle RL. Epigenetic gene regulation: linking early developmental environment to adult disease. Reprod Toxicol. 2007;23:297–307. doi: 10.1016/j.reprotox.2006.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singer T, McConnell MJ, Marchetto MC, Coufal NG, Gage FH. LINE-1 retrotransposons: mediators of somatic variation in neuronal genomes? Trends Neurosci. 2010;33:345–354. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2010.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenfeld CS. Animal models to study environmental epigenetics. Biol Reprod. 2010;82:473–488. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.109.080952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lueders KK, Kuff EL. Intracisternal A-particle genes: identification in the genome of Mus musculus and comparison of multiple isolates from a mouse gene library. PNAS. 1980;77:3571–3575. doi: 10.1073/pnas.77.6.3571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maksakova IA, Romanish MT, Gagnier L, Dunn CA, van de Lagemaat LN, Mager DL. Retroviral elements and their hosts: insertional mutagenesis in the mouse germ line. PLoS Genet. 2006;2:e2. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0020002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuff EL, Lueders KK. The intracisternal A-particle gene family: structure and functional aspects. Adv Cancer Res. 1988;51:183–276. doi: 10.1016/s0065-230x(08)60223-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dupressoir A, Heidmann T. Expression of intracisternal A-particle retrotransposons in primary tumors of oncogene-expressing transgenic mice. Oncogene. 1997;14:2951–2958. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1201148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin C, Wang Z, Shang J, Bekkari K, Liu R, Pacchione S, McNulty KA, Ng A, Barnum JE, Storer RD. Intracisternal A particle genes: distribution in the mouse genome, active subtypes, and potential roles as species-specific mediators of susceptibility to cancer. Mol Carcinog. 2010;49:54–67. doi: 10.1002/mc.20576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Maksakova IA, Gagnier L, van de Lagemaat LN, Mager DL. Genome-wide assessments reveal extremely high levels of polymorphism of two active families of mouse endogenous retroviral elements. PLoS Genet. 2008;4:e1000007. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolinoy DC, Weinhouse C, Jones TR, Rozek LS, Jirtle RL. Variable histone modifications at the A(vy) metastable epiallele. Epigenetics. 2010;5:637–644. doi: 10.4161/epi.5.7.12892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maksakova IA, Mager DL, Reiss D. Keeping active endogenous retroviral-like elements in check: the epigenetic perspective. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2008;65:3329–3347. doi: 10.1007/s00018-008-8494-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasicek TJ, Zeng L, Guan XJ, Zhang T, Costantini F, Tilghman SM. Two dominant mutations in the mouse fused gene are the result of transposon insertions. Genetics. 1997;147:777–786. doi: 10.1093/genetics/147.2.777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rakyan VK, Blewitt ME, Druker R, Preis JI, Whitelaw E. Metastable epialleles in mammals. Trends Genet. 2002;18:348–351. doi: 10.1016/S0168-9525(02)02709-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Druker R. Complex patterns of transcription at the insertion site of a retrotransposon in the mouse. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:5800–5808. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waterland RA, Jirtle RL. Transposable elements: targets for early nutritional effects on epigenetic gene regulation. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:5293–5300. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.15.5293-5300.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolinoy DC, Weidman JR, Waterland RA, Jirtle RL. Maternal genistein alters coat color and protects Avy mouse offspring from obesity by modifying the fetal epigenome. Environ Health Perspect. 2006;114:567–572. doi: 10.1289/ehp.8700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolinoy DC, Jirtle RL. Environmental epigenomics in human health and disease. Environ Mol Mutagen. 2008;49:4–8. doi: 10.1002/em.20366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolinoy DC, Huang D, Jirtle RL. Maternal nutrient supplementation counteracts bisphenol A-induced DNA hypomethylation in early development. PNAS. 2007;104:13056–13061. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0703739104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson OS, Nahar MS, Faulk C, Jones TR, Liao C, Kannan K, Weinhouse C, Rozek LS, Dolinoy DC. Epigenetic responses following maternal dietary exposure to physiologically relevant levels of bisphenol A. Environ Mol Mutagen. 2012;53:334–342. doi: 10.1002/em.21692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickies MM. A new viable yellow mutation in the house mouse. J Hered. 1962;53:84–86. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jhered.a107129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolinoy DC. The agouti mouse model: an epigenetic biosensor for nutritional and environmental alterations on the fetal epigenome. Nutr Rev. 2008;66(Suppl 1):S7–S11. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2008.00056.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magiorkinis G, Gifford RJ, Katzourakis A, De Ranter J, Belshaw R. Env-less endogenous retroviruses are genomic superspreaders. PNAS. 2012;109:7385–7390. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1200913109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiss D, Zhang Y, Rouhi A, Reuter M, Mager DL. Variable DNA methylation of transposable elements: the case study of mouse Early Transposons. Epigenetics. 2010;5:68–79. doi: 10.4161/epi.5.1.10631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchani EE, Xing J, Witherspoon DJ, Jorde LB, Rogers AR. Estimating the age of retrotransposon subfamilies using maximum likelihood. Genomics. 2009;94:78–82. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2009.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rakyan VK, Chong S, Champ ME, Cuthbert PC, Morgan HD, Luu KV, Whitelaw E. Transgenerational inheritance of epigenetic states at the murine Axin(Fu) allele occurs after maternal and paternal transmission. PNAS. 2003;100:2538–2543. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0436776100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Claus R, Wilop S, Hielscher T, Sonnet M, Dahl E, Galm O, Jost E, Plass C. A systematic comparison of quantitative high-resolution DNA methylation analysis and methylation-specific PCR. Epigenetics. 2012;7:772–780. doi: 10.4161/epi.20299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karpinski P, Szmida E, Misiak B, Ramsey D, Leszczynski P, Bebenek M, Sedziak T, Grzebieniak Z, Jonkisz A, Lebioda A, Sasiadek MM. Assessment of three epigenotypes in colorectal cancer by combined bisulfite restriction analysis. Mol Carcinog. 2011;51:1003–1008. doi: 10.1002/mc.20871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekram MB, Kang K, Kim H, Kim J. Retrotransposons as a major source of epigenetic variations in the mammalian genome. Epigenetics. 2012;7:370–382. doi: 10.4161/epi.19462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiss D, Mager DL. Stochastic epigenetic silencing of retrotransposons: does stability come with age? Gene. 2007;390:130–135. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2006.07.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jurka J, Kapitonov VV, Pavlicek A, Klonowski P, Kohany O, Walichiewicz J. Repbase Update, a database of eukaryotic repetitive elements. Cytogenet Genome Res. 2005;110:462–467. doi: 10.1159/000084979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goecks J, Nekrutenko A, Taylor J. Galaxy: a comprehensive approach for supporting accessible, reproducible, and transparent computational research in the life sciences. Genome Biol. 2010;11:R86. doi: 10.1186/gb-2010-11-8-r86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark SJ, Statham A, Stirzaker C, Molloy PL, Frommer M. DNA methylation: bisulphite modification and analysis. Nat Protoc. 2006;1:2353–2364. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiong Z, Laird PW. COBRA: a sensitive and quantitative DNA methylation assay. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:2532–2534. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.12.2532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grunau C, Clark SJ, Rosenthal A. Bisulfite genomic sequencing: systematic investigation of critical experimental parameters. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:E65–E65. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.13.e65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1. IAPLTR1_Mm elements derived from the mm9 genome.