A computer-based cancer specific geriatric assessment was developed and tested among patients age 70 and older receiving treatment for gastrointestinal malignancies at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute. The feasibility endpoints were met, although half of the sample required assistance and the results did not affect immediate clinical decision-making.

Keywords: Gastrointestinal cancer, Geriatric oncology, Geriatric assessment, Clinical decision-making

Abstract

Background.

The Cancer-Specific Geriatric Assessment (CSGA) is a primarily self-administered paper survey of validated measures.

Methods.

We developed and tested the feasibility of a computer-based CSGA in patients ≥70 years of age who were receiving treatment for gastrointestinal malignancies at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute. From December 2009 to June 2011, patients were invited to complete the CSGA at baseline (start of new treatment) and follow-up (at the first of 4 months later or within 4 weeks of completing treatment). Feasibility endpoints were proportion of eligible patients consented, proportion completing CSGA at baseline and follow-up, time to complete CSGA, and proportion of physicians reporting CSGA results that led to a change in clinical decision-making.

Results.

Of the 49 eligible patients, 38 consented (76% were treatment naive). Median age was 77 years (range: 70–89 years), and 48% were diagnosed with colorectal cancer. Mean physician-rated Karnofsky Performance Status was 87.5 at baseline (SD 8.4) and 83.5 at follow-up (SD 8). At baseline, 92% used a touchscreen computer; 97% completed the CSGA (51% independently). At follow-up, all patients used a touchscreen computer; 71% completed the CSGA (41% independently). Mean time to completion was 23 minutes at baseline (SD 8.4) and 20 minutes at follow-up (SD 5.1). The CSGA added information to clinical assessment for 75% at baseline (n = 27) and 65% at follow-up (n = 17), but it did not alter immediate clinical decision-making.

Conclusion.

The computer-based CSGA feasibility endpoints were met, although approximately half of patients required assistance. The CSGA added information to clinical assessment but did not affect clinical decision-making, possibly due to limited alternate treatment options in this subset of patients.

Implications for Practice:

The Cancer-Specific Geriatric Assessment (CSGA) developed by Hurria and colleagues has been shown to predict treatment-related toxicity in older adults with solid tumor malignancies. We investigated a computer-based version among adults age 70 and older initiating chemotherapy treatment for gastrointestinal cancer at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute. The feasibility criteria used were: (1) proportion of eligible patients consenting, (2) proportion completing CSGA at baseline and follow-up, (3) total time to complete the CSGA, and (4) proportion of physicians reporting change in clinical decision-making based on CSGA results. The feasibility endpoints were met, although approximately half of the patients required assistance. While the CSGA added information to clinical assessment, results did not impact immediate clinical decision-making, possibly because of limited alternate treatment options in this subset of patients. Further evaluation of the computer-based CSGA is warranted to determine its impact on treatment decisions in a general population of older cancer patients.

Introduction

Aging is an individualized process, reflecting a decline in functional status and physiologic reserve. As the population ages, the number of older persons diagnosed, dying, and living with cancer also increases. Older individuals (≥65 years old) accounted for 39% and 27% of all new cancer cases and cancer-related deaths among men and women, respectively, in the United States during 2001 to 2003 [1]. Older adults comprise 61% of all cancer survivors, the majority of whom are expected to live at least 5 years after cancer diagnosis [2–5]. Older patients are disproportionately affected by toxicity and functional decline during cancer treatment than their younger counterparts [6–16], yet little is known regarding factors modifying treatment outcome for this large subset of patients. Geriatric assessment is a tool that may provide a way to identify those older individuals who are most vulnerable to toxicity and functional decline from cancer therapy and to select patients for appropriate levels of care [17–19].

Geriatric assessment is a composite measure of life expectancy, physical function, and physiologic reserve [18]. It was initially defined in 1989 and includes validated measures of functional status, comorbid medical conditions, cognition, mental health, social functioning and support, medication review, and nutritional status [20, 21]. However, the full composite assessment as initially described can be time consuming and labor intensive, possibly precluding its usefulness in clinical care [17].

The Cancer Specific Geriatric Assessment (CSGA) developed by Hurria et al. is a brief geriatric assessment developed specifically for older patients with cancer that captures the data of the more lengthy and resource-intensive comprehensive geriatric assessment [17]. It is comprised of seven domains using validated measures to assess functional status, comorbid medical conditions, psychological state, cognition, nutritional status, social support, and medications. This abbreviated tool is a written questionnaire that has been evaluated for feasibility in a pilot study of 43 patients with cancer (mean age: 74 years), the majority of whom had stage IV disease. Nearly 80% of this cohort completed the CSGA without assistance in an average time of 27 minutes. The CSGA has been shown to predict treatment-related toxicity in older adults with solid tumor malignancies [22].

The CSGA has recently been modified as a computer-based self-report assessment. A version is presently being evaluated in individuals ≥65 years of age with hematologic malignancies but has yet to be evaluated in older patients with solid tumors (A. Hurria, personal communication). Self-report tools have been reported to be feasible among older individuals [23–25]. Yarnold et al showed high satisfaction among individuals ≥65 years of age reporting functional status using computer-based format, particularly the touchscreen computer format, with similar scores compared to a paper-and-pencil format (mean score: 8.7 ± 1.9 on a 10-point scale with standard deviation) [26]. Similarly, Goldstein et al. noted a high level of acceptance (76%) among 154 computer-inexperienced individuals ≥65 years of age reporting quality of life and functional status using a computer-based assessment tool [27].

Given increased utilization of the CSGA, we investigated a computer-based version of the CSGA among adults age 70 and older initiating chemotherapy treatment for gastrointestinal cancer at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute. The objectives of this feasibility study were (a) to develop a computer-based CSGA that can be completed and scored via computer survey methodology, (b) to assess administration feasibility, and (c) to assess the added clinical utility for health care providers with the ultimate goal of informing intervention strategies to optimize the treatment outcomes of older adults.

Patients and Methods

The CSGA feasibility study was conducted at the Gastrointestinal Cancer Center of the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston, MA. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Dana-Farber/Harvard Cancer Center.

Eligibility Criteria

Patients were considered eligible for inclusion if they (a) had the ability to understand and the willingness to sign a written informed consent document; (b) were diagnosed with gastrointestinal cancer at any stage under consideration for initiation of or change in cytotoxic chemotherapy regimen, excluding neuroendocrine cancers given infrequent use of cytotoxic chemotherapy; (c) were starting chemotherapy within 4 weeks of study enrollment (for those initiating treatment); (d) were age 70 or older at enrollment; (e) were able to read English and able to complete the web-based computer questionnaire. Patients were considered ineligible if they stated having a physical limitation preventing computer use (visual impairment, inability to use computer mouse or touchscreen) or were hospitalized or enrolled in hospice.

Computer-Based Geriatric Assessment Tool

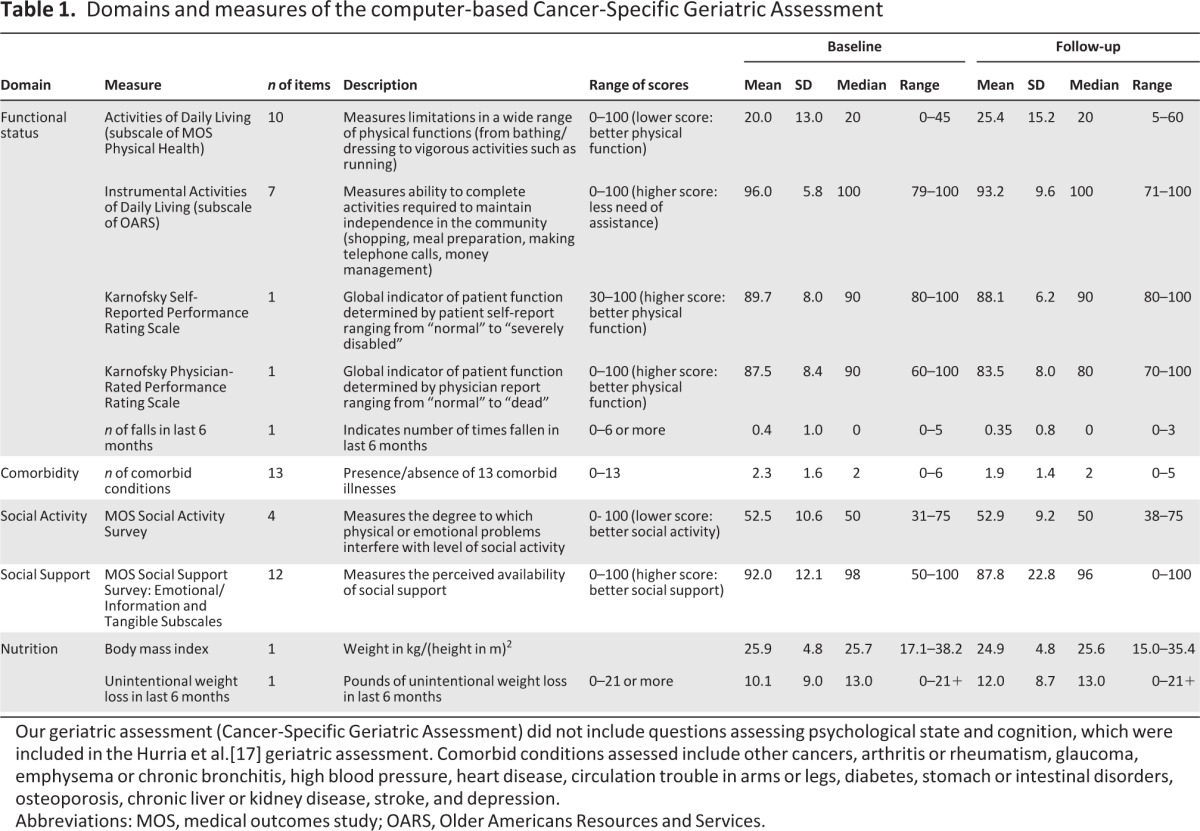

The seven domains and respective validated measures comprising the CSGA are described in detail elsewhere [28]. In contrast to the paper-and-pencil format of the CSGA, which includes a patient portion and a health care provider portion, the computer-based version is entirely self-administered. The assessment includes questions regarding patient demographics, functional status, comorbid medical conditions, cognition, social functioning and support, and nutrition (Table 1).

Table 1.

Domains and measures of the computer-based Cancer-Specific Geriatric Assessment

Our geriatric assessment (Cancer-Specific Geriatric Assessment) did not include questions assessing psychological state and cognition, which were included in the Hurria et al.[17] geriatric assessment. Comorbid conditions assessed include other cancers, arthritis or rheumatism, glaucoma, emphysema or chronic bronchitis, high blood pressure, heart disease, circulation trouble in arms or legs, diabetes, stomach or intestinal disorders, osteoporosis, chronic liver or kidney disease, stroke, and depression.

Abbreviations: MOS, medical outcomes study; OARS, Older Americans Resources and Services.

The computer-based CSGA utilized in this study differs from that of Hurria et al.[17] in that scores were converted to a 0–100 scale to allow ease of interpretation. Additionally, questions assessing psychological state and cognition were not included. Patients were instructed by a research assistant regarding completion of the CSGA using a touchscreen tablet computer. For patients unable to complete the tool, the assistant provided help. Questions regarding patient satisfaction or distress related to the CSGA were also assessed. Patients were asked to give feedback regarding the questionnaire's length, ability to comprehend questions, and if any question was either not easily understandable or upsetting. Efforts were made to increase computer familiarity by altering font size and color, limiting to one question per screen, and using touchscreen tablet computers.

Endpoints

The feasibility endpoints were as follows: (a) proportion of eligible patients consenting; (b) proportion completing CSGA at each of two time points (baseline defined as within 1 month of initiation or change in cytotoxic chemotherapy and follow-up defined as 4 months of enrollment or within 1 month of completion of therapy, whichever occurred first); (c) total time to complete the CSGA; and (d) proportion of physicians reporting change in clinical decision-making due to CSGA.

Study Implementation

A waiver of the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act allowed weekly review of clinic visit schedules to identify individuals age 70 and older initiating chemotherapy treatment for gastrointestinal cancer. Once potentially eligible patients were identified, the study team contacted the treating physician to request permission to contact the patient. Eligible patients were approached in clinic prior to their clinic visit for consent.

After completion of informed consent, subjects were enrolled in the study. Enrolled subjects were assigned a unique log-in code, ensuring secure and confidential collection of data. Subjects completed the CSGA in the clinic prior to their provider visit or during chemotherapy infusion. For subjects requiring assistance with completion of the CSGA, the research assistant provided help by either clarifying questions or completing the CSGA on the participant's behalf. Eligible and consented subjects who remained unable to complete the computer-based format were allowed to complete the paper-and-pencil format of the same tool. Degree of independence in completing the CSGA and format of CSGA used was recorded. Patients were provided with printed results of the CSGA directly following completion. The time required to complete the CSGA was recorded starting at the point of log-in to completion of the final question. Participating subjects also completed the CSGA at a second time point, at 4 months of enrollment or within 1 month of completion of therapy, whichever occurred first.

A unique patient identifier was created for each patient, linked to their CSGA log-in code and stored in a password-protected, separate database at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute. The unique patient identifier was linked to baseline characteristics of the patient, including age, sex, current treatment, and stage of cancer obtained from review of the longitudinal medical record. In this manner, the clinical data was deidentified for the purposes of statistical analysis.

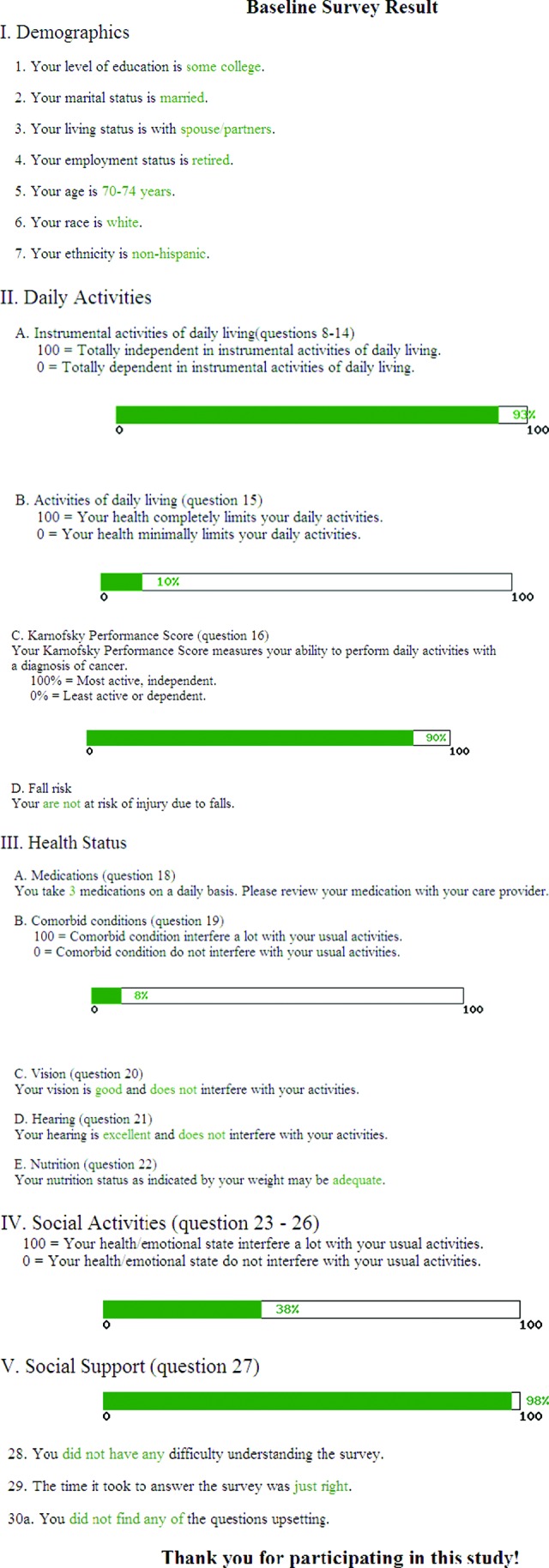

Treating physicians in the Gastrointestinal Cancer Center for each enrolled patient were consented to participate. A single consent was used for each physician regardless of the number of their patients enrolled. Consenting physicians were provided with the results of their patient's first CSGA ideally at the time of chemotherapy treatment initiation (Fig. 2). Patient CSGA results were provided as a printed summary by CSGA domain for physicians to review. Email requests for completion of the Physician Utility Questionnaire (PUQ) were sent to the physicians along with their patient's CSGA results, ideally on the same day as CSGA completion. If there was no response after 1 week, a repeat e-mail was sent, followed by a phone call after an additional week.

Figure 2.

Sample Cancer-Specific Geriatric Assessment report for patients.

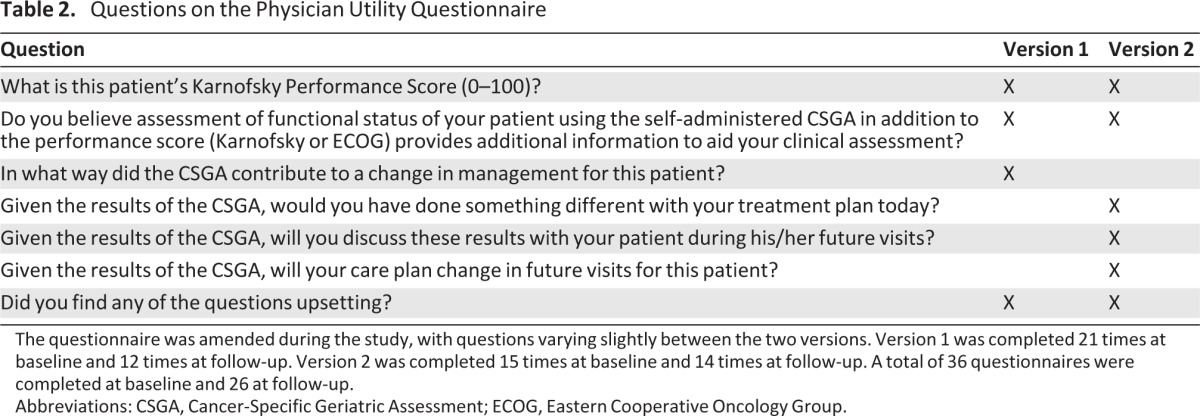

The PUQ was a series of questions administered to physicians via e-mail following the patient's completion of both the baseline and follow-up CSGA. The PUQ was amended midway through the study, with questions varying slightly between the two versions to capture additional details from responding providers (Table 2). Version 1 of the PUQ included four questions and was completed by seven physicians, 21 times at baseline and 12 times at follow-up. Version 2 of the PUQ included six questions and was completed by six physicians, 15 times at baseline and 14 times at follow-up. A total of 36 PUQs were completed at baseline and 26 PUQs at follow-up. The proportion of physicians selecting each choice for each question on both versions of the PUQ was measured and analyzed.

Table 2.

Questions on the Physician Utility Questionnaire

The questionnaire was amended during the study, with questions varying slightly between the two versions. Version 1 was completed 21 times at baseline and 12 times at follow-up. Version 2 was completed 15 times at baseline and 14 times at follow-up. A total of 36 questionnaires were completed at baseline and 26 at follow-up.

Abbreviations: CSGA, Cancer-Specific Geriatric Assessment; ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group.

Statistical Considerations

The CSGA was administered as a series of 34 questions (one question per computer screen page). There are 7 questions on demographics and 27 questions covering the seven domains of the CSGA. Three questions measure the level of distress the subject may experience attributable to completing the CSGA. Data were summarized using descriptive statistics, including means with standard deviations and medians with ranges. Sample size was based on estimated 50% of population being able to complete 70% of the CSGA at each time point. Feasibility was defined as the proportion of individuals ≥70 years old completing 70% or more of the CSGA at each time point (start of new treatment regimen and at 4 months of enrollment or 1 month of completion of the regimen, whichever occurred first) using a one-sided test with 5% type I error. We estimated the proportion of completion of 50% for the null hypothesis and 70% for the targeted population. The planned sample size allowed >90% power to reject the null hypothesis if it was not true.

Results

Patient Enrollment and Characteristics

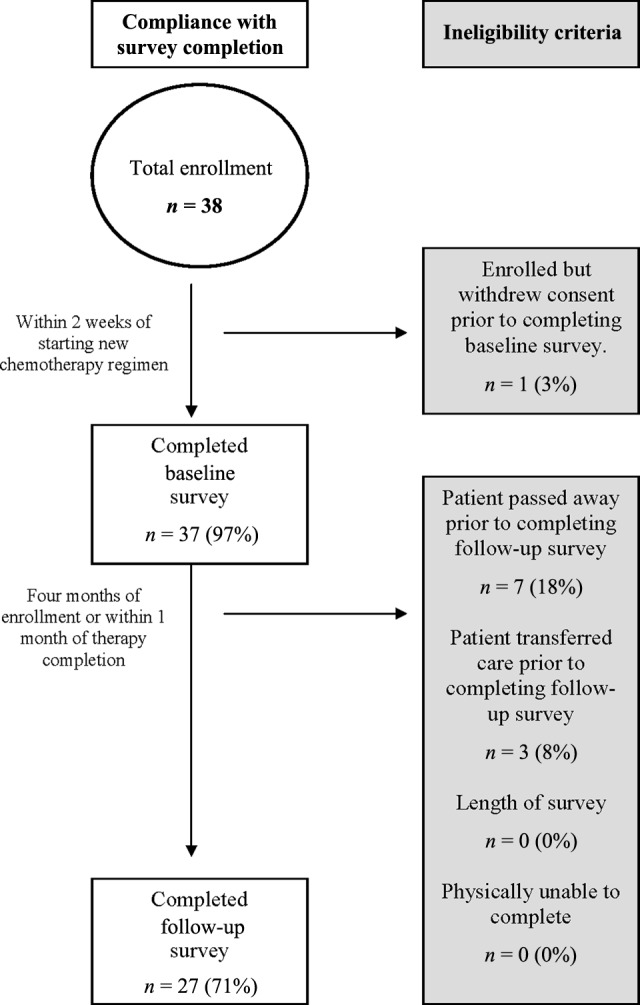

The computer-based CSGA feasibility study was open to accrual from December 2, 2009 to June 21, 2011 at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute. During that period, 38 patients were enrolled (Fig. 1). One patient subsequently withdrew consent prior to completing the baseline survey due to rapid functional decline. The remaining 37 patients (97%) completed the baseline CSGA within 2 weeks of initiating or changing to a new cytotoxic chemotherapy regimen. Of those, 27 patients (71%) completed a follow-up CSGA within 4 months of study enrollment or within 1 month of completing cytotoxic chemotherapy started at enrollment. Of the 10 patients not completing the second CSGA, 7 (18%) were deceased by that time point. The remaining three patients (8%) transferred care prior to completing the second CSGA.

Figure 1.

Derivation of the Cancer-Specific Geriatric Assessment cohort.

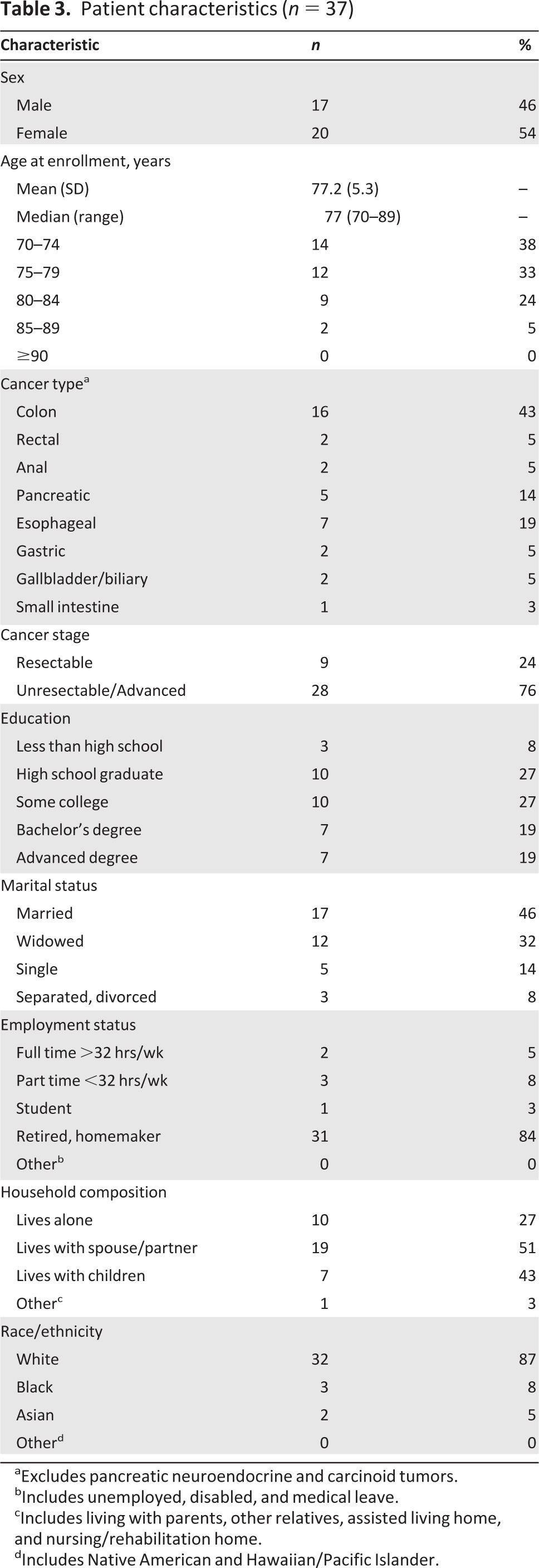

Over half of the enrolled patients were female and the majority of those enrolled were white (Table 3). The mean age of this cohort was 77 years (SD 5.3), with 11 patients age 80 or older. Most patients (76%) had unresectable or advanced disease. The majority of patients were diagnosed with colorectal cancer (48.6%), with at least one patient in each type of major gastrointestinal cancer. The cohort was well-educated; 65% had at least some college education. Nearly half were married (46%) and 27% lived alone. Although the majority of patients were retired (84%), 13.5% reported being employed either part-time or full-time.

Table 3.

Patient characteristics (n = 37)

aExcludes pancreatic neuroendocrine and carcinoid tumors.

bIncludes unemployed, disabled, and medical leave.

cIncludes living with parents, other relatives, assisted living home, and nursing/rehabilitation home.

dIncludes Native American and Hawaiian/Pacific Islander.

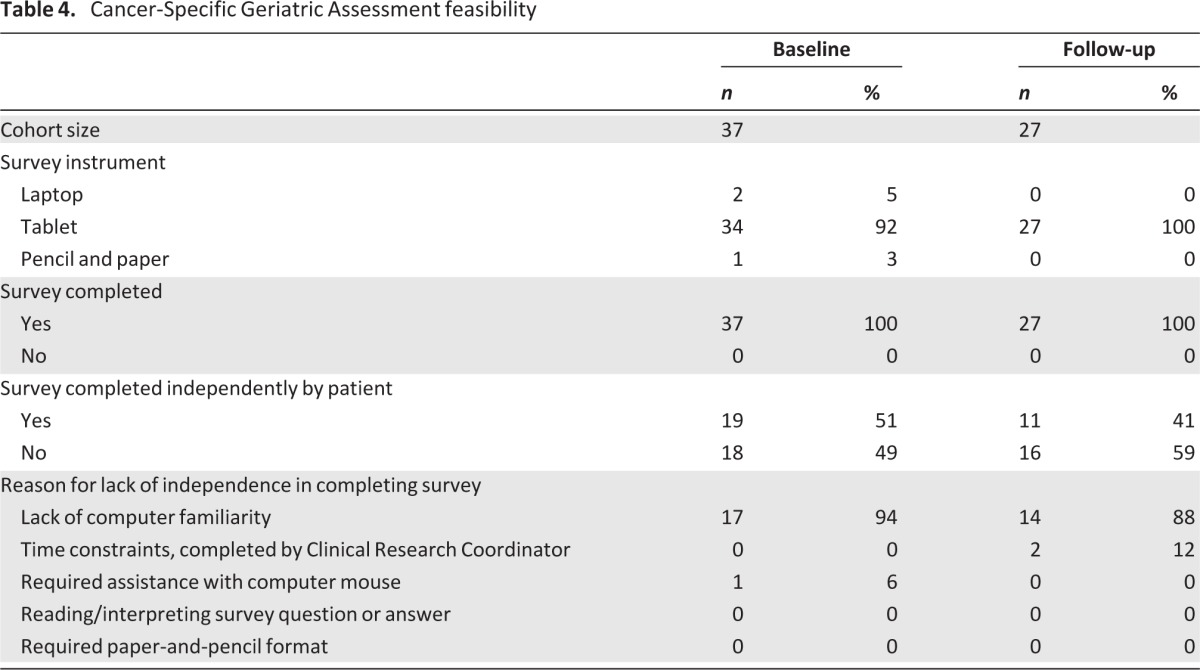

Feasibility of Computer-Based CSGA

Due to a change in computer equipment at the start of the study, the first two patients used a laptop with mouse for the baseline CSGA (Table 4). The subsequent patients used a touchscreen tablet computer at baseline, with one person requiring paper-and-pencil format. The one person withdrawing consent did not complete the baseline CSGA. Although 51% of patients independently completed the survey, 49% were unable to do so due to lack of computer familiarity (n = 17) or needing assistance with the computer mouse (n = 1). There was no indication of time constraints or assistance needed in reading or interpreting the survey questions or answers.

Table 4.

Cancer-Specific Geriatric Assessment feasibility

All 27 patients who completed both time points did so using touchscreen tablet format (Table 4). Of the 11 patients unable to complete the survey, the majority were deceased by that time point (n = 7, 64%) and three transferred care to another institution. Sixteen of the 27 patients (59%) completing the follow-up CSGA were unable to do so independently, primarily due to lack of computer familiarity, reported by 14 patients (88%). In contrast to the baseline assessment, two patients reported time constraints and required help provided by the research assistant. No patient reported needing assistance with reading/interpreting the survey questions or response choices.

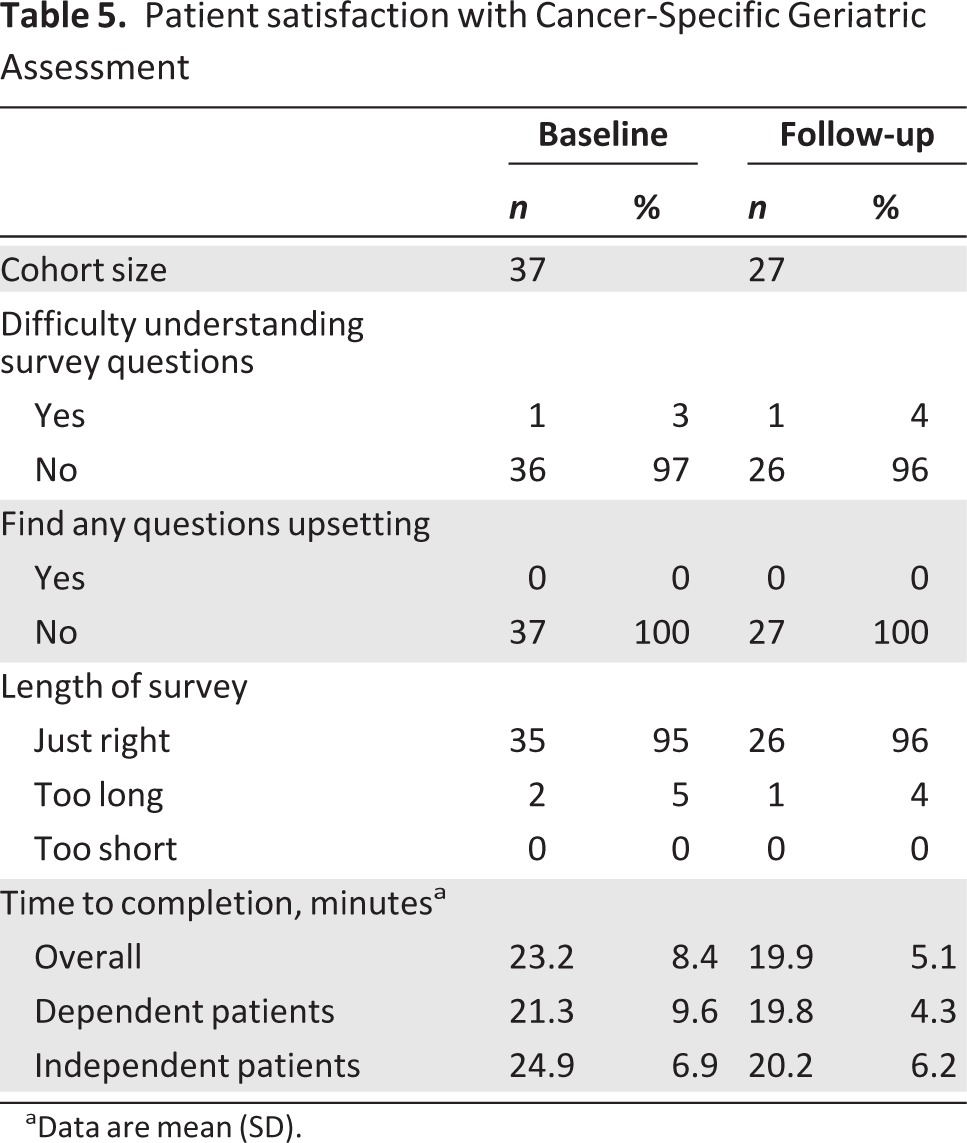

Average time to completion of the CSGA was comparable at baseline (23 ± 8.4 minutes, SD) and follow-up (20 ± 5.1 minutes; Table 5). This remained true for those requiring assistance with completion of the assessment (baseline: 21 ± 9.6 minutes; follow-up: 20 ± 4.3 minutes).

Table 5.

Patient satisfaction with Cancer-Specific Geriatric Assessment

aData are mean (SD).

Cancer-Specific Geriatric Assessment

Functional Status

The mean scores on the activities of daily living scale (ADL) was 20 ±13 and instrumental activities of daily living scale (IADL) was 96 ± 5.8. Both measures declined at follow-up, indicating lower physical function (ADL) and increased need of assistance (IADL). Both patients and physicians rated high performance on the physician-rated Karnofsky Performance Status (KPS) at both baseline (patient: 89.7 ± 8; physician: 87.5 ± 8.4) and follow-up (patient: 88.1 ± 6.2; physician: 83.5 ± 8). Few patients reported having fallen in the past 6 months.

Comorbidity

The average number of comorbid medical conditions in this cohort was 2.3 ± 1.6 at baseline, decreasing to 1.9 ± 1.4 at follow-up due to attrition. The most common comorbid condition was hypertension (49% at baseline, 52% at follow-up), yet it did not interfere with usual activities. Arthritis was the second most common comorbid condition (49% at baseline, 41% at follow-up), which did interfere with function (22% at baseline and follow-up). Patients reported that the presence of comorbid illnesses other than their cancer diagnosis interfered with usual activities at both time points.

Social Activity

Patients reported that physical or emotional problems interfered with social activity to a moderate degree, similarly at baseline (52.5 ± 10.6) and follow-up (52.9 ± 9.2).

Social Support

Patients reported a high level of social support (92 ± 12.1), decreasing by the time of follow-up (87.8 ± 22.8).

Nutrition

Mean body mass index (BMI) in this cohort was 25.9 ± 4.8 at baseline, similar to that at follow-up (24.9 ± 4.8). At both time points, nine patients (24% baseline, 33% follow-up) reported low BMI of <22. In contrast, 16% were obese (BMI >30) at baseline and 15% at follow-up. Over half of the baseline cohort (51.4%) reported unintentional weight loss of 10 or more pounds within the prior 6 months, increasing to two thirds of the cohort at follow-up (66.7%).

Participant Distress

With the exception of one patient at baseline and follow-up, nearly all patients reported comprehension of the survey questions (Table 5). No one reported finding the questions distressing. The majority of patients reported satisfaction with the length of the survey.

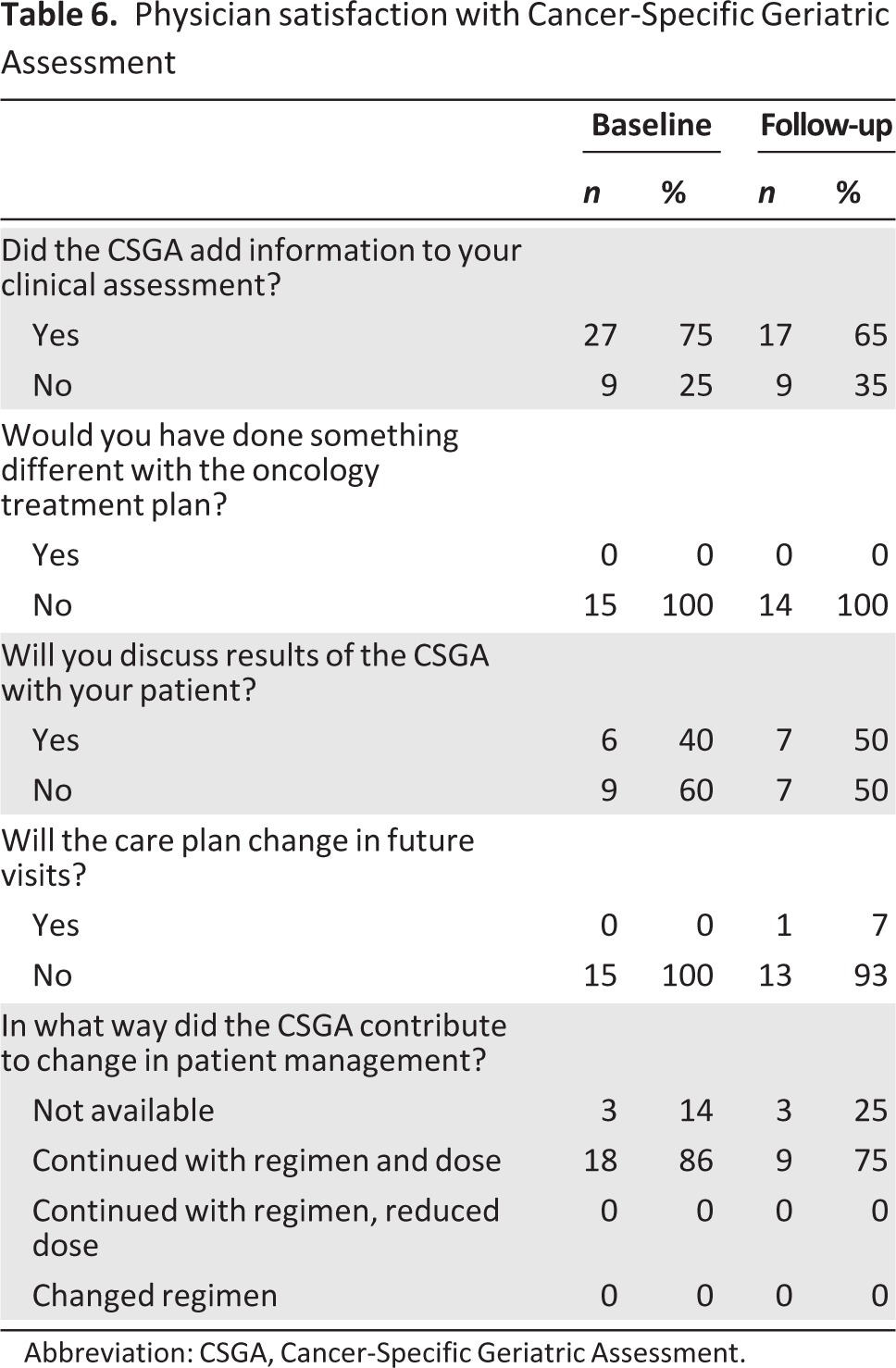

Physician Utility Questionnaire

The majority of physicians reported that the CSGA results added to their clinical assessments of patients (75% at baseline, 65% at follow-up; Table 6). However, nearly all of the physicians reported that the assessment would not alter their current (100% at both baseline and follow-up) or future treatment plan (100% at baseline, 93% at follow-up). Interestingly, up to half of the physicians noted that they would discuss the assessment results with their patients.

Table 6.

Physician satisfaction with Cancer-Specific Geriatric Assessment

Abbreviation: CSGA, Cancer-Specific Geriatric Assessment.

Discussion

We evaluated the feasibility of a computer-based CSGA in an older population of patients diagnosed with gastrointestinal cancer, beginning or changing cytotoxic chemotherapy at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute. Of the 38 patients age 70 or older eligible to enroll during the study period, 97% and 71% completed 100% of the baseline and follow-up surveys, respectively. The dominant reason for not completing the survey was death by the second time point.

At least 50% of patients were unable to complete the computer-based CSGA without assistance. These results suggest appreciably fewer patients were able to complete the CSGA unassisted in comparison to the feasibility results of completing this assessment via paper/pencil format as reported in Cancer and Leukemia Group B (CALGB) 360401 [28], in which 87% of the 85 evaluable patients completed the CSGA independently. Unlike the paper CSGA, functional limitations (e.g., visual disturbance) did not impact ability to complete the computer CSGA independently. The dominant reason for lack of independence in completing the CSGA was lack of computer familiarity. Nearly all patients expressed satisfaction with the CSGA length and question structure with minimal distress, similar to that observed in the CALGB 360401 study.

Time to completion of the CSGA was similar to that of the paper format. The results of the paper format for the CSGA recently published from CALGB 360401 [28] noted the 85 evaluable patients had a median time to completion of 22 minutes (range: 6–60 minutes). In contrast to the paper format, we did not include two of the three health care professional portions using the timed up-and-go test or cognitive screen with the Blessed Orientation-Memory-Concentration test. We did not record time to completion of the physician-rated KPS, which which was incorporated in the PUQ as previously noted. However, physicians did not report any dissatisfaction with their portion of the assessment.

Although the majority of physicians note that the CSGA added information to their clinical assessment at both time points, most noted no impact on actual treatment plan recommended. In this feasibility study, we did not measure the impact of the CSGA on supportive care referrals. To our knowledge, prior reports of geriatric assessment tools have not demonstrated how the results directly affect clinical decision-making. There is no indication that geriatric assessment should alter oncology treatment decisions, but it could add to clinical information used to guide overall management of older patients. In fact, experts suggest that because geriatric assessment can identify patients at risk of increased treatment-related toxicity [22], it could be used as an intervention tool to screen patients in need of additional supportive care to minimize that risk [29]. However, there are active clinical trials within the National Cancer Institute-sponsored ALLIANCE cooperative group (formerly CALGB) for older adults incorporating with colorectal cancer, acute myeloid leukemia, and pending studies in lung cancer and multiple myeloma. Given this, data regarding integration of assessment results into treatment decisions is forthcoming.

The generalizability of these results is limited by a sample of mainly highly educated and physically functional older adults at a single site. In comparison to participants enrolled in CALGB 360401 (which evaluated the feasibility of the paper-and-pencil CSGA in patients enrolled in cooperative group studies) and the Cancer and Aging Research Group study (which used the CSGA to identify specific items which predicted the risk of chemotherapy toxicity), our cohort had higher scores on the patient and physician KPS. Interestingly, although patient and physician KPS at baseline was high, seven patients died prior to the second time point for completion of the CSGA. Although we do not know the exact cause of death in this subset, it is possible that KPS did not capture those at risk of mortality following start or change in cytotoxic chemotherapy.

A second limitation may be the lack of a summary score for the entire CSGA. Thus far, the tool is defined by individual scores from each domain. These individual scores were converted to percentages depicted on each patient's CSGA report as bar graphs on a 0%–100% scale to allow easier visualization for patients and providers. A third limitation is that clinical assessments by providers at an academic institution may differ from community-based colleagues with regard to anticipated treatment tolerance for older adults beginning or changing cytotoxic chemotherapy.

Lastly, the CSGA results were not consistently available for providers prior to a treatment decision being made and discussed with patients. As such, the CSGA did not affect clinical decision-making, a fact which may be further explained by limited subsequent treatment options for some patients.

Although the CSGA did not affect clinical decision-making in this cohort, early reporting of results prior to the visit to discuss treatment options may affect this outcome in future study. Further study of the computer-based CSGA is warranted to evaluate its utility in a more general older population with solid tumors, with prospective enrollment of a balanced cohort of patients with resectable or unresectable/advanced disease. Further study should also measure how CSGA affects referral patterns for supportive care. To overcome lack of computer familiarity reported by a subset of patients (46% at baseline, 52% at follow-up), a brief computer tutorial should be included at the start of the assessment. If successful, the computer-based CSGA could be a time-efficient method of obtaining geriatric assessment information, eliminating the errors and cost of data entry, and providing additive information to inform treatment decisions for older adults.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the American Society of Clinical Oncologists Young Investigator Award and the National Institutes of Health Program in Cancer Outcomes Research Training (R25CA092203) and Dana-Farber Cancer Institute Gastrointestinal SPORE Career Development Award (5P50CA127003–05). We also acknowledge the assistance of the Survey and Data Management Core of the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute.

Disclosures

Peter Enzinger: Taiho, Boehringer-Ingleheim, Sanofi (C/A); Charles S. Fuchs: Genentech, Roche, Amgen, Metamark Genetics, Sanofi, Pfizer, Momenta, Bayer, Infinity (C/A); Arti Hurria: GTX, Seattle Genetics (C/A); GlaxoSmithKline, Celgene (RF). The other authors indicated no financial relationships.

(C/A) Consulting/advisory relationship; (RF) Research funding; (E) Employment; (H) Honoraria received; (OI) Ownership interests; (IP) Intellectual property rights/inventor/patent holder; (SAB) Scientific advisory board

References

- 1.Cancer Facts & Figures 2007. Atlanta, GA: American Cancer Society; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carver JR, Shapiro CL, Ng A, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical evidence review on the ongoing care of adult cancer survivors: Cardiac and pulmonary late effects. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:3991–4008. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.10.9777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rao AV, Demark-Wahnefried W. The older cancer survivor. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2006;60:131–143. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2006.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rowland JH, Yancik R. Cancer survivorship: The interface of aging, comorbidity, and quality care. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98:504–505. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djj154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.SEER. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute; 2011. Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results. Available at http://seer.cancer.gov/popdata. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Repetto L. Greater risks of chemotherapy toxicity in elderly patients with cancer. J Support Oncol. 2003;1:18–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Balducci L, Carreca I. Supportive care of the older cancer patient. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2003;48:S65–S70. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2003.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Balducci L. Management of cancer in the elderly. Oncology. 20:135–143. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rosti G, Kopf B, Cariello A, et al. Prevention and therapy of neutropenia in elderly patients. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2003;46:247–253. doi: 10.1016/s1040-8428(03)00024-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carbone PP. Advances in the systemic treatment of cancers in the elderly. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2000;35:201–218. doi: 10.1016/s1040-8428(00)00049-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lichtman SM. Chemotherapy in the elderly. Semin Oncol. 2004;31:160–174. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2003.12.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wedding U, Rohrig B, Klippstein A, et al. Age, severe comorbidity and functional impairment independently contribute to poor survival in cancer patients. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2007;133:945–950. doi: 10.1007/s00432-007-0233-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Serraino D, Fratino L, Zagonel V. Prevalence of functional disability among elderly patients with cancer. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2001;39:269–273. doi: 10.1016/s1040-8428(00)00130-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Extermann M, Overcash J, Lyman GH, et al. Comorbidity and functional status are independent in older cancer patients. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16:1582–1587. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1998.16.4.1582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gross CP, McAvay GJ, Krumholz HM, et al. The effect of age and chronic illness on life expectancy after a diagnosis of colorectal cancer: Implications for screening. Ann Intern Med. 2006;145:646–653. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-145-9-200611070-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lichtman SM. Management of advanced colorectal cancer in older patients. Oncology. 2005;19:597–602. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hurria A, Gupta S, Zauderer M, et al. Developing a cancer-specific geriatric assessment: A feasibility study. Cancer. 2005;104:1998–2005. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Balducci L. Aging, frailty, and chemotherapy. Cancer Control. 2007;14:7–12. doi: 10.1177/107327480701400102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Extermann M, Hurria A. Comprehensive geriatric assessment for older patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:1824–1831. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.10.6559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Repetto L, Fratino L, Audisio RA, et al. Comprehensive geriatric assessment adds information to Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status in elderly cancer patients: An Italian Group for Geriatric Oncology Study. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:494–502. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.20.2.494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hurria A, Lachs MS, Cohen HJ, et al. Geriatric assessment for oncologists: Rationale and future directions. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2006;59:211–217. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2006.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hurria A, Togawa K, Mohile SG, et al. Predicting chemotherapy toxicity in older adults with cancer: A prospective multicenter study. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:3457–3465. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.34.7625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nikolaus T, Bach M, Oster P, et al. Prospective value of self-report and performance-based tests of functional status for 18-month outcomes in elderly patients. Aging. 1996;8:271–276. doi: 10.1007/BF03339578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Reuben DB, Siu AL, Kimpau S. The predictive validity of self-report and performance-based measures of function and health. J Gerontol. 1992;47:M106–M110. doi: 10.1093/geronj/47.4.m106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee Y. The predictive value of self assessed general, physical, and mental health on functional decline and mortality in older adults. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2000;54:123–129. doi: 10.1136/jech.54.2.123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yarnold PR, Stewart MJ, Stille FC, et al. Assessing functional status of elderly adults via microcomputer. Percept Mot Skills. 1996;82:689–690. doi: 10.2466/pms.1996.82.2.689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Goldstein MK, Miller DE, Davies S, et al. Quality of life assessment software for computer-inexperienced older adults: multimedia utility elicitation for activities of daily living. Proc AMIA Symp. 2002:295–299. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hurria A, Cirrincione CT, Muss HB, et al. Implementing a geriatric assessment in cooperative group clinical cancer trials: CALGB 360401. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:1290–1296. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.30.6985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Balducci L. New paradigms for treating elderly patients with cancer: The comprehensive geriatric assessment and guidelines for supportive care. J Support Oncol. 2003;1:30–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]