Abstract

Small interfering RNA (siRNA) is a promising tool for the treatment of dominant diseases. Autosomal dominant eye disease like retinitis pigmentosa, are a leading cause of blindness. Mutations in rds/peripherin lead to the degeneration of photoreceptors and are associated with several autosomal retinal diseases. Our goal is to develop a gene therapy for rds mutations. We describe a siRNA based mutation-independent approach, targeting rds in which levels of endogenous mutant and wild-type mRNA were reduced, and a siRNA-resistant version of rds gene was supplied simultaneously. siRNAs and resistant rds were delivered to the photoreceptors by recombinant adeno-associated virus (rAAV) vector through subretinal injections. The retinal phenotype was examined, both structurally and functionally at different time points after rAAV delivery. We demonstrate suppression of rds transcript by up to 50% with concomitant expression of replacement transcript in the retina of mice in vivo. These results validate the concept of suppression of rds and replacement strategies of gene therapy with rAAV vectors containing siRNA.

29.1 Introduction

Autosomal dominant retinitis pigmentosa (ADRP) is a genetically heterogeneous disease and the most prevalent hereditary cause of blindness, with more than 1 million individuals affected worldwide (Hartong et al. 2006). Mutations in rds (retinal degeneration slow/peripherin) are one of the most common associated with ADRP, accounting for approximately 10% of the cases (Fingert et al. 2008). RDS is a transmembrane glycoprotein localized to the rim region of outer segment (OS) disks in rods and cones (Wrigley et al. 2000). Mice carrying a naturally occurring null mutant fail to form photoreceptor outer segments. Heterozygotes have a partial phenotype of short, disorganized outer segments (Ma et al. 1995) suggesting a haploinsufficiency. Thus far, over 90 human mutations in rds have been identified and result in a wide spectrum of retinal dystrophies, in which the common feature is the visual loss associated with the gradual death of photoreceptor cells. To date, attempts to achieve structural and functional rescue in animal models of rds-induced retinal degeneration have not been successful. Disease may be caused by reduction in the level of wild-type protein (haploinsufficiency), by a gain of a deleterious function or by a combination of both.

Gene therapy may be a promising approach for treating RDS/peripherin disease. Upon subretinal injection of recombinant adeno associated virus (rAAV) vector containing rds, null mice responded with increases in rhodopsin synthesis, correction of rod outer segment formation and restoration of visual function over the first 14 weeks following treatment (Ali et al. 2000; Schlichtenbrede et al. 2003). However, treatment did not result in long-term preservation of photoreceptors (Sarra et al. 2001). Because of the dominant nature of this class of disease, simple gene replacement therapy is usually insufficient to overcome the expression of the mutant allele. Rather, the therapeutic approach for dominant negative mutations must be to either eliminate the mutated gene or repair its mutation together with gene replacement. The critical importance of RDS in photoreceptor OS integrity suggests that a suppression and replacement strategies may be useful. Because there are at least 90 different disease-causing dominant mutations in rds, targeted gene elimination or repair for each separate mutation becomes problematic. Therefore, gene therapy aimed at dominant genes, like rds, requires either mutation-independent suppression of mutated allele expression or an increase in the expression of the wild-type allele, or both. One approach to suppress expression is with small interfering RNA (siRNA). The silencing mechanism is based on ubiquitous cellular processes, in which the interference RNA degrades mRNA in a sequence-specific manner, upon introduction of double-stranded RNA (Hammond et al. 2000).

The objective of this work is to develop an effective therapy for genetic retinal disease associated with mutations in rds. For this, we propose the development of a siRNA to eliminate the endogenous rds mutant and wild-type mRNA, followed by a replacement therapy where a siRNA-resistant version of rds is supplied simultaneously. The siRNA and the resistant rds will be delivered to photoreceptor cells of diseased mice retinas through rAAV.

29.2 Materials and Methods

29.2.1 Cell Transfection

HEK-293 cells were grown in 24-well plates at 30-50% confluence for overnight then co-transfected with 10 pmol of synthetic siRNA (Applied Biosystems) and 200ng of plasmid using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). A scrambled siRNA was used as negative control. After 72hs mRNA was collected.

29.2.2 RNA Isolation and Semi-Quantitative Real-Time PCR

Total RNA was extracted using RNeasy Kit as manufacturer’s instructions (Qiagen). Total RNA (2μg) was reverse-transcribed (RT) using First Strand Kit (GE), with the same amount of RNA for each reaction. RT- RNA was mixed with SYBER Green and applied to 96 well plates for real-time PCR using commercially available primer pairs from SA.Biosciences (Qiagen). A two-step cycling program was employed (1 cycle 10 min at 95°C followed by 40 cycles of 15 sec at 95°C and one minute at 60°C). Data analysis was done following SA.Biosciences protocol.

29.2.3 AAV Production

AAV vectors were produced by plasmid co-transfection of HEK-293 cells as described by Zolotukhin et al. Vector titer was determined as DNase-resistant vector genomes by real-time PCR relative to a standard.

29.2.4 Subretinal Injection

All procedures in animals were handled according to the ARVO Statement for the Use of Animals in Ophthalmic and Vision Research and the guidelines of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Florida. Eyes were injected as described by Timmers et al.

29.2.5 Electroretinogram

Mice were dark adapted overnight, and all procedures were carried out under dim red light. Mice were anesthetized and eyes were dilated. Hydroxypropyl methylcellulose 2.5% was applied to each eye to prevent corneal dehydration and to allow for optimal electrical conductivity. Mice were placed onto a platform with their entire head inside the Ganzfeld stimulus dome. ERGs were recorded using gold loop cornea electrodes. Aluminum hub needles placed subcutaneously between the eyes and in a hind leg were used for the reference and ground electrodes, respectively. ERGs were recorded using a PC-based control and recording unit (Toennies Multiliner Vision). Scotopic rod ERG luminance response functions were elicited through a series of 5 white flashes of high intensity (0.7 log cd s/m2).

29.2.6 Statistical Analysis

Differences between groups were evaluated using one-way-ANOVA for analysis of variance followed by Dunnett’s post-test for group comparison. Differences were considered significant at P value of less than 0.01.

29.3 Results

29.3.1 Synthetic siRNAs Targeted to rds Reduces Transduction in Vitro in HEK-293 Cells

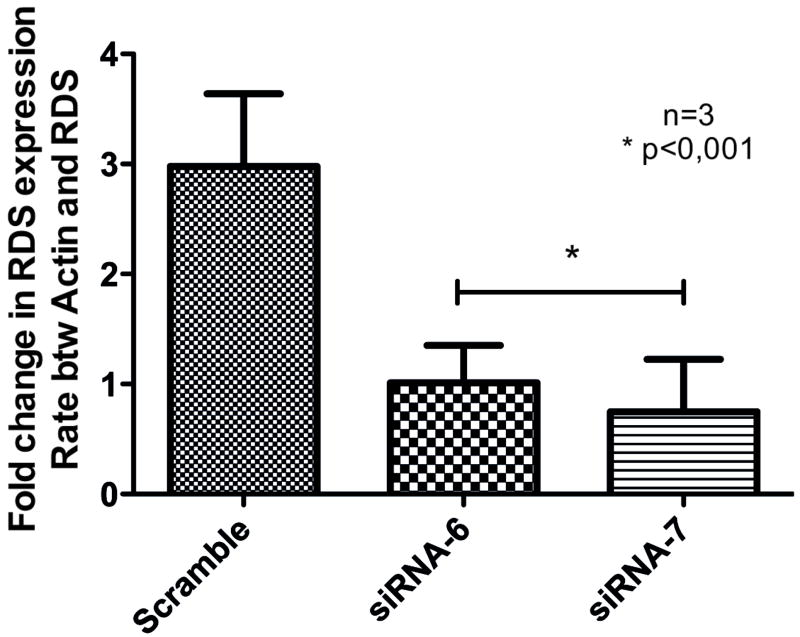

Initially two synthetic siRNAs were tested for its specificity and efficacy to decrease rds expression in HEK-293 cells co-transfected with siRNAs and a plasmid expressing rds from the CMV promoter, through semi-quantitative real-time PCR. Both siRNAs were able to reduce more than 50% of rds expression in vitro, when compared with a scrambled siRNA used as a control (Fig. 29.1).

Fig. 29.1.

HEK-293 cells co-transfected with plasmid containing rds and synthetic siRNA for 72hs followed by RNA extraction and real time PCR to analyze rds expression.

29.3.2 Effect of siRNA Directed to rds in Vivo in Photoreceptors by rAAV-5 Vector

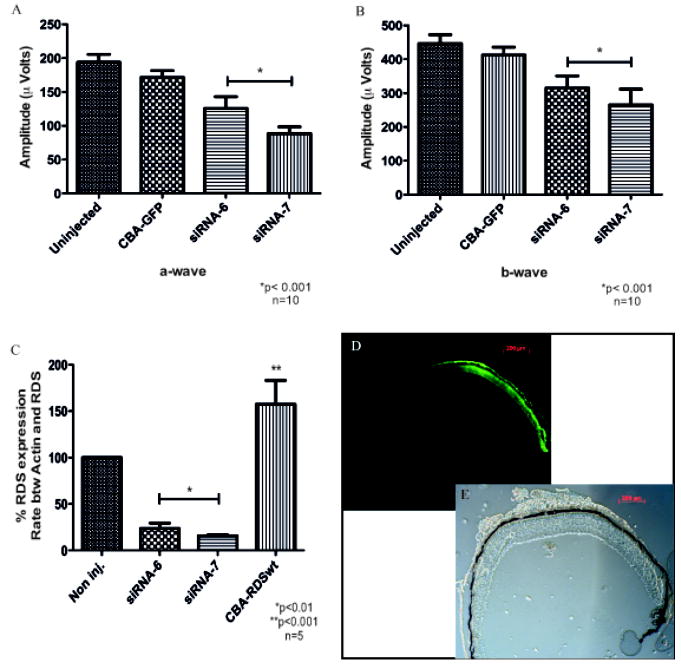

To determine the effect of these siRNAs targeted to rds in vivo, both siRNAs were cloned in rAAV vector under the control of the H1 RNA polymerase III promoter. As a reporter we used the green fluorescent protein (GFP) gene under the control of chicken beta-actin (CBA) promoter in the same AAV5 vector. Six week old C57Bl/6 mice were injected subretinally with 1μl of the vectors (109 vg). Right eyes received rAAV with siRNA and left eyes were uninjected or received rAAV with only GFP. One month after infection, full-field scotopic electroretinograms (ERG) were recorded.. Both a- and b-wave amplitudes were reduced around 30 to 50% with both siRNAs directed to rds (Fig. 29.2A and B). Control injected or uninjected eyes showed no change in ERG response. Reduction in ERG responses was paralleled by a reduction in RDS mRNA content in the retinas measured by real-time PCR at the same time point (Fig. 29.2C). In contrast injection with rAAV containing the rds gene led to an increase in rds mRNA levels. The distribution of AAV infection was determined by detection of GFP expression through fluorescence microscopy (Fig. 29.2D). Since we do not transduce the entire retina, RNA knockdown by siRNA must have been very efficient on a per cell basis.

Fig. 29.2.

Reduction of rds in mice by siRNA delivered by rAAV to photoreceptors. Functional analysis by ERG: graphics show maximal amplitude of a-wave (A) and b-wave (B). Analysis of rds expression in the presence of siRNA 6 or 7 (C): total RNA was extracted and analyzed using real-time PCR. Transverse section of the retina showing its intact structure thought bright field (D) and a fluorescent picture of the same field (E) showing GFP expression in approximately ½ of the retina, corresponding to rAAV transduced area.

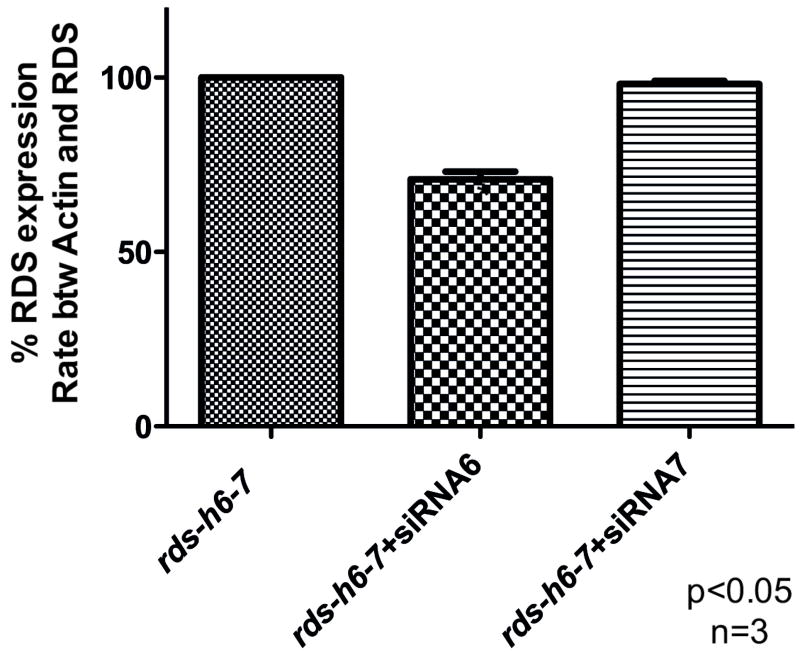

29.3.3 Construction of rds Resistant to siRNA

In order to construct a rds gene resistant to the action of siRNAs 6 and 7, we changed all possible nucleotides in each siRNA recognition site without changing the amino acid coding and called the modified cDNA, rds h6-7. The resistance of the rds-h6-7 to siRNAs 6 and 7 was initially analyzed in HEK-293 cells. Cells were co-transfected with the rds-h6-7 under CBA promoter plus each synthetic siRNA. At 72hs post infection, total RNA was collected and the amount of rds expression was analyzed through real-time PCR. Rds-h6-7 was completely resistant to siRNA7 but was only partially resistant to siRNA6 in vitro (Fig. 29.3).

Fig. 29.3.

HEK-293 cells co-transfected with plasmid containing resistant rds-h6-7 and siRNA 6 or 7 for 72hs followed by RNA extraction and real time PCR to analyze rds-h6-7 expression.

29.3.4 Proof of Principal for Combination Therapy for rds Using AAV Vector in Photoreceptors in Vivo

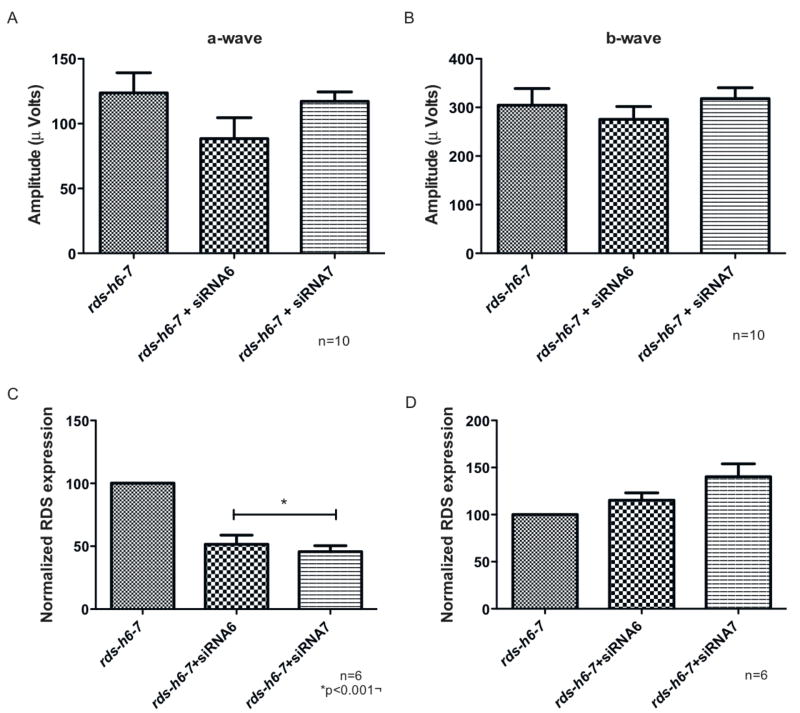

To test the feasibility of a combination therapy for rds related diseases, a rAAV vector containing rds-h6-7 was constructed. Combination injection was done with rAAV2/5 expressing siRNA6 or 7 and the rds-h6-7 in the subretinal space of C57Bl/6 mice. A total of 1μl of the vectors were injected, both at 109 vg/μl. One month after injection, simultaneous full-field scotopic ERGs were recorded. There was a slight decrease in a-wave amplitude in the presence of siRNA6, confirming that rds-h6-7 is not completely resistant to the action of siRNA6 (Fig. 29.4A). However there was no significant change in amplitude in the combination rds-h6-7 and siRNA7 (Fig. 29.4A). There was no significant difference in b-wave amplitudes between the eyes injected with rds-h6-7 alone and rds-h6-7 plus either siRNA. It is important to note that siRNA7 was the most effective reducing ERG (Fig. 29.2). These results suggests that even in the presence of siRNA-7 directed to down regulate the expression of the wild-type rds in mouse photoreceptors, the co-expression of an rds allele resistant to this siRNA is capable of maintaining the function of these cells in vivo.

Fig. 29.4.

Co-infection of photoreceptors in vivo with siRNA 6 or 7 plus resistant rds delivered by rAAV – reposition of rds expression by its resistant version. Functional analysis by ERG: graphics show maximal amplitude of a-wave (A) and b-wave (B). Analysis by real-time PCR of total rds expression (C) and only of resistant rds with a distinct primer (D). PCR values for rds were normalized to the levels of β-actin in the same samples.

To examine RNA replacement, we analyzed rds expression by real time PCR. First we analyzed the total amount of rds expression, including endogenous and resistant genes, using a pair of primers that recognize both transcripts. We measured a reduction of 50% of the total rds with both siRNAs, indicating that some rds was degraded. We also designed a pair of primers specific for the resistant version of the rds delivered by AAV. There was no reduction of the exogenous rds with either siRNA-6 or siRNA-7. These results confirm that the resistant version of rds is resistant to the action of the siRNA-7 and partially resistant to siRNA-6, that down regulate only the endogenous transcript.

29.4 Discussion

The results showed that siRNA-based small hairpin RNA can efficiently and specifically silence RDS in vivo one month after AAV2/5-mediated delivery to the photoreceptors, leading to a nearly 50% reduction in rds expression in the retina, and also leading to a reduction in the electrophysiological function of the photoreceptors detected by decrease of the electoretinogram a-and b- wave amplitudes.. The reduction of 50% in rds expression might be related with the area of the retina covered by the injection that was also around 50%. In this study we also designed a version of rds resistant to the action of the siRNA, and we showed that the presence of this resistant version together with siRNA preveneted the decrease in the ERG response, while endogenous rds expression was reduced by the siRNA. This result suggests that the exogenous resistant version of rds was able to provide the amount of rds expression necessary to preserve the physiological function of the photoreceptors.

These results represent the proof of principle for the effectiveness of a combination therapy using siRNA to suppress rds expression and gene replacement by adding a copy of rds resistant to the action of the siRNA. This strategy can be applied by gene therapy using rAAV vector to deliver both the siRNA and the resistant gene into photoreceptor cells in order to treat retinal diseases caused by mutations in rds/peripherin. The strategy of knocking down gene expression with siRNA delivered by rAAV vectors could also be adapted to other autosomal dominant eye diseases.

The heterogeneity in many dominant disease-causing genes represents a significant challenge with respect to development of viable gene therapy. As an example, rds related retina diseases are caused by over 90 different mutations within the gene, each of which could require a unique gene therapy. However our approach overcomes this problem with a siRNA directed to a region in which no mutations have been described. This siRNA would be effective for the down regulation of all the mutants described so far in rds gene and also the normal allele. In order to maintain rds expression the resistant version of rds would complement this RNA knockdown. This approach should be applicable for most exon mutations in the rds/peripherin gene leading to autosomal dominant disease. For loss-of-function mutations, however, using AAV to deliver the wild-type gene might be sufficient.

References

- Ali RR, Sarra GM, Stephens C, et al. Restoration of photoreceptor ultrastructure and function in retinal degeneration slow mice by gene therapy. Nat Genet. 2000;25:306–310. doi: 10.1038/77068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fingert JH, Oh K, Chung M, et al. Association of a novel mutation in the retinol dehydrogenase 12 (RDH12) gene with autosomal dominant retinitis pigmentosa. Arch Ophthalmol. 2008;126:1301–1307. doi: 10.1001/archopht.126.9.1301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammond SM, Bernstein E, Beach D, Hannon GJ. An RNA-directed nuclease mediates post-transcriptional gene silencing in Drosophila cells. Nature. 2000;404:293–296. doi: 10.1038/35005107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartong DT, Berson EL, Dryja TP. Retinitis pigmentosa. Lancet. 2006;368:1795–809. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69740-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma J, Norton JC, Allen AC, et al. Retinal degeneration slow (rds) in mouse results from simple insertion of a t haplotype-specific element into protein-coding exon II. Genomics. 1995;28:212–219. doi: 10.1006/geno.1995.1133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarra GM, Stephens C, de Alwis M, et al. Gene replacement therapy in the retinal degeneration slow (rds) mouse: the effect on retinal degeneration following partial transduction of the retina. Hum Mol Genet. 2001;10:2353–2361. doi: 10.1093/hmg/10.21.2353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlichtenbrede FC, da Cruz L, Stephens C, et al. Long-term evaluation of retinal function in Prph2Rd2/Rd2 mice following AAV-mediated gene replacement therapy. J Gene Med. 2003;5:757–764. doi: 10.1002/jgm.401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timmers AM, Zhang H, Squitieri A, et al. Subretinal injections in rodent eyes: effects on electrophysiology and histology of rat retina. Mol Vis. 2001;7:131–137. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wrigley JD, Ahmed T, Nevett CL, et al. Peripherin/rds influences membrane vesicle morphology. Implications for retinopathies. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:13191–13194. doi: 10.1074/jbc.c900853199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zolotukhin S, Potter M, Zolotukhin I, et al. Production and purification of serotype 1, 2, and 5 recombinant adeno-associated viral vectors. Methods. 2002;28:158–167. doi: 10.1016/s1046-2023(02)00220-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]