Abstract

Background:

The aim of this study was to evaluate the shear bond strength of an antimicrobial and fluoride-releasing self-etch primer (clearfil protect bond) and compare it with transbond plus self-etch primer and conventional acid etching and priming system.

Materials and Methods:

Forty-eight extracted human premolars were divided randomly to three groups. In group 1, the teeth were bonded with conventional acid etching and priming method. In group 2, the teeth were bonded with clearfil protect bond self-etch primer, and transbond plus self-etch primer was used to bond the teeth in group 3. The samples were stored in 37°C distilled water and thermocycled. Then, the SBS of the sample was evaluated with Zwick testing machine. Descriptive statistics and the analysis of variances (ANOVA) and Tukey's test and Kruskal-Wallis were used to analyze the data.

Results:

The results of the ANOVA showed that the mean of group 3 was significantly lower than that of other groups. Most of the sample showed a pattern of failure within the adhesive resin.

Conclusion:

The shear bond strength of clearfil protect bond and transbond plus self-etch primer was enough for bonding the orthodontic brackets. The mode of failure of bonded brackets with these two self-etch primers is safe for enamel.

Keywords: Acid etching, antimicrobial, bond strength, fluoride, self etch primer

INTRODUCTION

Placement of fixed orthodontic appliances usually colonizes streptococcus mutans, and enhances the risk of dental caries.[1–3]

Fluoride-releasing bonding materials for bonding the brackets showed almost no demineralization inhibiting effect.[4]

Buyukilmaz and Ogaard in an earlier study suggested the combined use of antimicrobials and fluoride to enhance the cariostatic effect of fluoride.[5]

A new fluoride releasing and antimicrobial bonding material Clearfil Protect Bond self-etch primer (CPB) (Kurrary Medical Inc., Okayama, Japan) has been introduced in dental materials. This two-step self-etch primer (SEP) consists of a specially treated sodium fluoride to resist against demineralization.[6] Additionally, it contains 12-methacryloyloxydodecyl pyridinium bromide (MDPB); the antibacterial agent of this SEP. MDPB is a functional monomer and destroys the cell membrane of bacteria.[7]

Recently, another self-etching primer has been developed for orthodontic practice (Transbond Plus self-etching primer, 3M Unitek, Monrovia, CA, USA).

This one-step SEP combines the etching, priming, and bonding in one-step application and reduces the bonding time, increases the cost-effectiveness for the clinician and the patient, and not requiring a separate acid etching step and the need for rinsing.[8]

However, effective bonding of these two self-etching primers is controversial. Korbmacher et al.[9] and Cal-Neto and Miguel[10] reported that the SBS of brackets bonded with CPB, in comparison with conventional method (CM) (acid etching and priming) did not show any significant difference, while Bishara et al.[11] and Tuncer et al.[12] found that CPB had significantly higher SBS than CM.

On the other hand, Ulker et al.,[13] and Holzmeier et al.,[14] stated that the SBS of brackets bonded with CPB was significantly lower than CM.

Arnold et al.,[15] and Dorminey et al.,[16] reported no significant difference in the bond strength between the brackets bonded with TP and CM, whereas Aljubouri et al.,[17] and Grubisa et al.,[18] observed significantly lower SBS in brackets bonded with TP and conversely, Buyukilmaz et al.,[19] and Bishara et al.,[20] reported significantly higher SBS values in brackets bonded with TP, in comparison with CM.

Based on the controversial results of the previous studies, the purpose of this study was to evaluate and compare the SBS and adhesive remnant index (ARI) of brackets bonded with conventional acid etching and priming, Transbond Plus, and Clearfil Protect Bond self-etch primers.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

In this prospective in vitro study accomplished in Torabinejad Dental Research Center of Isfahan Dental School, we examined 48 human maxillary premolars, extracted for orthodontic purposes.

The selection criteria included intact buccal enamel, the absence of pretreatment with chemical agents and the absence of cracks and dental caries. After storage of the sample in thymol (0.1% wt/vol) for a week, they were rinsed with distilled water and then the roots of them were embedded into a self-cure acrylic resin (Rapid Repair, Detrey Dentsply Ltd. Surrey, UK) cylindrical block. The long axis of each tooth was aligned parallel to the cylindrical base with a jig. The teeth were cleaned and polished with a fluoride-free pumice (Prophylaxis Paste, Golchai Co., Tehran, Iran) using a low-speed handpiece for 10 seconds, and then, they were washed and air dried with an oil free air spray thoroughly. The samples were randomly divided into three groups of 16 teeth each.

Bonding procedures

For bonding the samples with Transbond XT adhesive resin (3 M Unitek, Monrovia, CA, USA) [Figure 1], 0.018” stainless steel brackets (Standard edge, Orthoorganizer, CA, USA) were used. The bonding procedure was performed for each self-etch primer as follows:

Figure 1.

Transbond XT adhesive resin

Group 1 (conventional acid etching and priming with Transbond XT primer) (group CM)

The teeth were etched with 37% phosphoric acid (American Orthodontics Co., WI, USA) for 30 seconds.

Then, they were washed completely and dried for 10 seconds to chalky white appearance. After application of a thin layer of the Transbond XT primer (3 M Unitek, Monrovia, CA, USA) [Figure 2] on the etched enamel surface, the brackets were bonded with Transbond XT adhesive resin and light cured with Dr's Light (Prestige Dental Products Inc. CA, USA) for 40 seconds.

Figure 2.

Transbond XT primer

Group 2 (Clearfil protect bond) (group CPB)

CPB consists of two bottles: Primer and bond [Figure 3]. First, the self-etching primer was applied using slight agitation for 20 seconds and dried with a mild air flow. Then, Clearfil Protect Bond was applied and gently air flowed. After that, the adhesive system was cured for 10 seconds and the brackets were bonded with Transbond XT adhesive resin similar to Group 1.

Figure 3.

Clearfil Protect Bond (self etching primer and bond)

Group 3 (Transbond Plus self-etching primer) (group TP)

According to the manufacturer's instruction, TP [Figure 4] was applied to the teeth for 5 seconds and the brackets were bonded with Transbond XT adhesive resin and light cured for 40 seconds.

Figure 4.

Transbond Plus (one step self etching primer)

All the samples were stored in 37°C distilled water for 24 hours and were thermocycled from 5°C to 55°C for 500 cycles.

Evaluation of shear bond strength

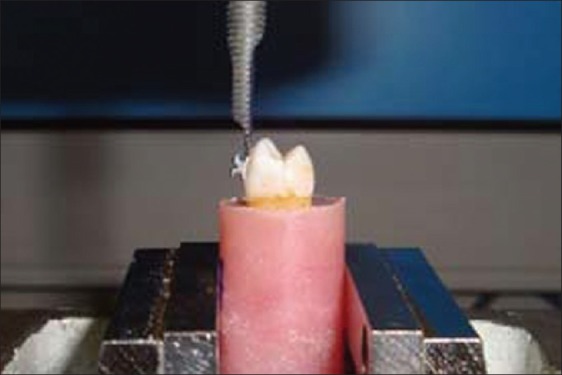

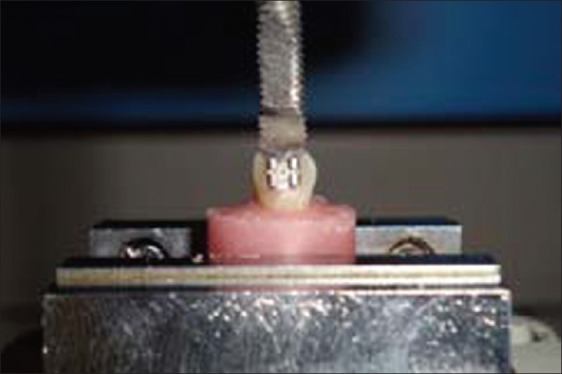

SBS of the sample was evaluated by a universal testing machine (Zwick 2020, Zwick Gmbh and Co., Ulm, Germany). The blade of machine was placed vertically between the base of bracket and the resin [Figures 5 and 6] and started to apply force in and occluso-gingival direction with a crosshead speed of 1 mm/min.

Figure 5.

Placing the blade of Zwick machine vertically between the base of the bracket and the resin (lateral view)

Figure 6.

Placing the blade of Zwick machine vertically between the base of the bracket and the resin (frontal view)

To determine the shear bond strength in MPa, the measured SBS in Newton was divided by the bracket surface area 11.55 mm2.

Residual adhesive

The mode of failure was assessed with optical stereomicroscope (×10 magnification, Olympus SZX9, Olympus Corporation, Shinjuku- Ku, Japan). Failures were scored, according to Adhesive Remnant Index (ARI) developed by Artun and Bergland.[21]

The following scale is used to quantify the amount of remaining adhesive on the teeth surfaces:

“O”: No adhesive remains on the tooth; “1”: Less than 50% of adhesive remains on the tooth; “2”: More than 50% of adhesive remains on the tooth; “3”: All adhesive remains on tooth and the imprint of bracket base is visible on it.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were preformed with the Statistical Package for Special Science (SPSS 11.0, SPSS Inc., Chicago, Illinois, USA). Descriptive statistics, including the mean, standard deviation, minimum, and maximum, were calculated for each of the three groups. After analysis the normal distribution of SBSs of the samples with Kolmogorov-Smirnov test and test of homogeneity of variances, comparisons of the means of SBS in the three groups were carried out with one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA).

Multiple comparisons were undertaken using Tukey's honestly significant difference (HSD) test. The Kruskal-Wallis test was used to determine significant differences in the ARI values of the groups. The level of significance was determined at P<0.05.

RESULTS

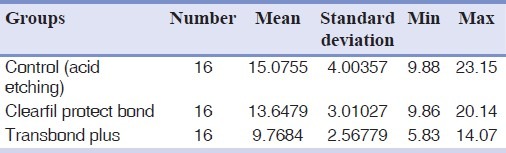

The descriptive statistics for each group are presented in Table 1. The results of the ANOVA showed statistically significant difference in SBS among the three groups (P<0.001). The Tukey's HSD test indicated that the SBS of group CM (mean: 15.08±4.00 MPa) and group CPB (mean: 13.65±3.01 MPa) were significantly higher than group TP (mean: 9.77±2.57 MPa) (P<0.001), but there was no significant difference in SBS of group CM and group CPB (P=0.435).

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics of shear bond strength in study groups

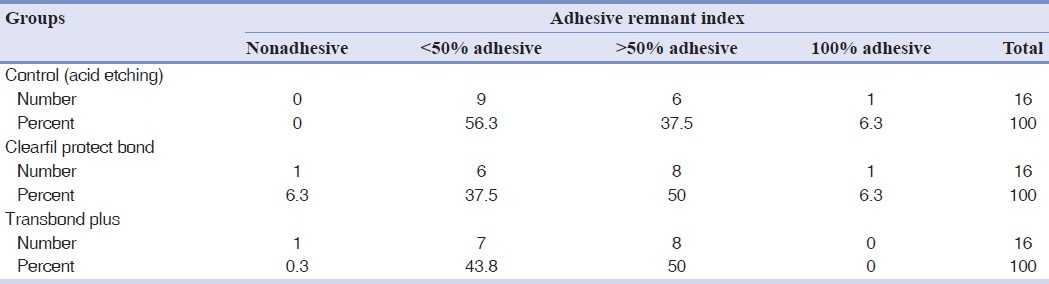

The distribution of the ARI scores is shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Distribution of adhesive remnant index scores in study groups

The Kruskal–Wallis test showed no significant difference in the ARI scores of the groups (P=0.287).

DISCUSSION

The potential risk of new enamel caries among patients with fixed appliances is estimated between 13 and 75%.[22,23] Patients’ oral hygiene status and diet during treatment are the significant factors for developing dental caries.[24] MDPB in Clearfil Protect Bond has revealed great antibacterial effect because it has the potential to destruct the cell membrane of bacteria.[25,26]

The specially treated sodium fluoride (NaF) in CPB makes the enamel resistant to the acid generated by bacteria.[6]

In the current study the mean SBS of group CPB in comparison with the mean SBS of group CM did not show any significant difference, according to post hoc Tukey's test (P=0.435). The obtained result was consistent with the results of studies conducted by Korbmacher et al.[9] and Cal-Neto and Miguel.[10] In spite of the results of the present study, the higher SBS of brackets bonded with CPB, has been reported by Bishara et al.,[11] and Tuncer et al.,[12] Conversely, Ulker et al.,[13] and Holzmeier et al.,[14] showed lower SBS of brackets bonded with CPB than conventional acid etching and priming. However, according to our study CPB has fulfilled the requirement to bond orthodontic brackets, because it shows the SBS higher than the minimum recommended by Reynold et al.,[27] and is not such greatly high that could damage the periodontium during debonding.

Self-etching systems have become an accepted bonding technique, since they combine the etching and priming steps and do not need a rinsing and drying step after etching; so, diminishes chair time and are cost-effective for the clinician.[8]

According to the results of this study, one-step TP self-etching primer revealed lower SBS than CM and CPB (P<0.001).

Reynold et al. stated that the SBS of bonded brackets should be more than 6–8 MPa for adequate adhesion in orthodontics.[27] Thus, TP has the mean SBS, high enough to resist against accidental debonding during treatment.

The results of the present study were in agreement with other studies.[17,18,28] Notwithstanding, higher mean SBS of brackets bonded with TP has been observed by Buyukilmaz et al.,[19] and Bishara et al.,[20] while Arnold et al.,[15] and Dorminey et al.,[16] reported that there was no significant difference in the mean SBS of brackets bonded with TP and CM.

The contradictory results of the studies, conducted to evaluate and compare the mean SBS between brackets bonded with CM, CPB, and TP, could be related to difference in the conditions of the sample storage, operators techniques, duration of light curing, doing or not doing thermocycling, and the evaluation of the SBS with different methods.[29–32]

According to the results presented, in Table 2, the ARI scores of 1 and 2 are the most prevalent for all three groups and the Kruskal–Wallis test detected no significant difference in the ARI between groups (P=0.287).

The site of failure could be within the bracket-adhesive-enamel complex and the ARI scores of 1 and 2 in this study indicate that in the most of the samples, the bond failure has occurred within adhesive and some adhesive remained on the enamel.

This mode of failure in group CPB similar to the findings of other studies[9,14,33] and dominant score of “1” and “2” for group TP is supported by the reports of the previous studies.[15,19,29,34,35]

There are two opinions about the remaining adhesive on teeth after debonding. The first opinion supports the bracket adhesive interface failure and believes that this mode of failure is safe for enamel and diminishes the risk for enamel crack and damage.[8] Our findings support this opinion.

Another opinion involves failure at the enamel–adhesive–resin interface[36] and states that this mode of failure takes less time to remove the adhesive and polish the surface of enamel. This pattern of failure is supported by some authors,[35,37] but we believe that failure close to enamel is not safe, and, the findings of the present study support our belief.

CONCLUSIONS

CPB has enough SBS to use for bonding of orthodontic brackets and the pattern of debonding is safe for enamel.

Despite that brackets bonded with TP has a lower mean SBS than those bonded with CM, but the SBS of brackets bonded with TP is high enough for clinical practice. In addition, the mode of failure with TP is safe for enamel.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This study (No. 390048) was supported financially by Research Center of Isfahan University of Medical Sciences and Health Services, Isfahan, Iran. Also, the authors wish to express their sincere respect to the deans and staff members of Professor Torabinejad Dental Research Center and Dental Research Center of Shaheed Beheshti University of Medical Sciences.

Footnotes

Source of Support: This report is based on a thesis which was submitted to the School of Dentistry, Isfahan University of Medical Sciences, Isfahan, Iran, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the MSc degree in Orthodontics (#390048). The study was approved by the Medical Ethics and Research Office at the Isfahan University of Medical Sciences and financially supported by this University.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Corbett JA, Brown LR, Keene HJ, Horton IM. Comparison of Streptococcus mutans concentrations in non-banded and banded orthodontic patients. J Dent Res. 1981;60:1936–42. doi: 10.1177/00220345810600120301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Balenseifen JW, Madonia JV. Study of dental plaque in orthodontics patients. J Dent Res. 1970;49:320–4. doi: 10.1177/00220345700490022101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mattingly JA, Sauer GJ, Yancey JM, Aronld RR. Enhancement of Streptococcus mutans colonization by direct bonded orthodontic appliances. J Dent Res. 1983;62:1209–11. doi: 10.1177/00220345830620120601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Derks A, Katsaros C, Frencken JE, van’t Hof MA, Kuipers-Jagtman AM. Caries-inhibiting effect of preventive measure during orthodontic treatment with fixed appliances. Caries Res. 2004;38:413–20. doi: 10.1159/000079621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Buyukyilmaz T, Ogaard B. Caries preventive effects of fluoride-releasing materials. Adv Dent Res. 1995;9:377–3. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Waidyasekera K, Nikaido T, Weerasinghe D, Ichinose S, Tagami J. Reinforcement of dentin in self etch adhesive technology: A new concept. J Dent. 2009;37:604–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2009.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Imazato S. Bio-active restorative materials with antibacterial effects: New dimension of innovation in restorative dentistry. Dent Mater J. 2009;28:11–9. doi: 10.4012/dmj.28.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bishara SE, Oonsombat C, Ajlouni R, Laffoon JF. Comparison of the shear bond strength of 2 self-etch primer/adhesive systems. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2004;125:348–50. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2003.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Korbmacher H, Huck L, Adom T, Kahl–Nieke B. Evaluation of an antimicrobial and fluoride–releasing self-etching primer on the shear bond strength of orthodontic brackets. Eur J Orthod. 2006;28:457–61. doi: 10.1093/ejo/cjl013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cal–Neto JP, Miguel JA. Scanning electron microscopy evaluation of the bonding mechanism of a self etching primer on enamel. Angle Orthod. 2006;76:132–6. doi: 10.1043/0003-3219(2006)076[0132:SEMEOT]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bishara SE, Soliman M, Laffoon J, Warren JJ. Effect of antimicrobial monomer-containing adhesive on shear bond strength of orthodontic brackets. Angle Orthod. 2005;75:397–9. doi: 10.1043/0003-3219(2005)75[397:EOAMAO]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tuncer C, Tuncer BB, Ulusoy C. Effect of fluoride releasing light cured resin on shear bond strength of orthodontic brackets. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2009;135:14e1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2008.09.016. discussion 14-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ulker M, Uysal T, Ramoglu SI, Ucar FI. Bond strengths of an antibacterial monomer-containing adhesive system applied with and without acid etching for lingual retainer bonding. Eur J Orthod. 2009;31:658–63. doi: 10.1093/ejo/cjp037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Holzmeier M, Schaubmayr M, Dasch W, Hirschfelder U. A new generation of self-etching adhesives: Comparison with traditional acid etch technique. J Orofac Orthop. 2008;69:78–93. doi: 10.1007/s00056-008-0709-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Arnold RW, Combe EC, Warford JH. Bonding of stainless steel brackets to enamel with a new self etching primer. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2002;122:274–6. doi: 10.1067/mod.2002.125712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dorminey JC, Dunn WJ, Taloumis LJ. Shear bond strength of orthodontic brackets bonded with a modified 1-step etchant-and-primer technique. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2003;124:410–13. doi: 10.1016/s0889-5406(03)00404-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Aljubouri YD, Millet DT, Gilmour WH. Laboratory evaluation of a self etching primer for orthodontic bonding. Eur J Orthod. 2003;25:411–5. doi: 10.1093/ejo/25.4.411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grubisa HS, Heo G, Raboud D, Glover KE, Major PW. An evaluation and comparison of orthodontic bracket bond strengths achieved with self-etching primer. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2004;126:213–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2004.01.016. quiz 255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Buyukyilmaz T, Usumez S, Karaman A. Effect of self-etching primers on bond strength-are they reliable? Angle Orthod. 2003;73:64–70. doi: 10.1043/0003-3219(2003)073<0064:EOSEPO>2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bishara SE, Oonsombat C, Soliman MM, Warren JJ, Laffoon JF, Ajlouni R. Comparison of bonding time and shear bond strength between a conventional and a new integrated bonding system. Angle Orthod. 2005;75:233–8. doi: 10.1043/0003-3219(2005)075<0233:COBTAS>2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Artun J, Bergland S. Clinical trials with crystal growth conditioning as an alternative to acid-etch enamel pretreatment. Am J Orthod. 1984;85:333–40. doi: 10.1016/0002-9416(84)90190-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wenderoth CJ, Weinstein M, Borislow AI. Effectiveness of a fluoride releasing sealant in reducing decalcification during orthodontic treatment. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1999;116:629–34. doi: 10.1016/s0889-5406(99)70197-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fornell AC, Sköld-Larsson K, Hallgren A, Bergstrand F, Twetman S. Effect of a hydrophobic tooth coating on gingival health, mutans streptococci, and enamel demineralization in adolescents with fixed orthodontic appliances. Acta Odontol Scand. 2002;60:37–41. doi: 10.1080/000163502753471989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zimmer BW, Rottwinkel Y. Assessing patient-specific decalcification risk in fixed orthodontic treatment and its impact on prophylactic procedures. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2004;126:318–24. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2003.09.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Imazato S, Kinomoto Y, Tarumi H, Torii M, Russell RR, McCabe JF. Incorporation of antibacterial monomer MDPB into dentin primer. J Dent Res. 1997;76:768–72. doi: 10.1177/00220345970760030901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Imazato S, Kuramoto A, Takahashi Y, Ebisu S, Peters MC. in vitro antibacterial effects of the dentin primer of Clearfil protect bond. Dent Mater J. 2006;22:527–32. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2005.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Reynolds IR. A review of direct orthodontic bonding. Br J Orthod. 1975;2:171–8. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Arhun N, Arman A, Sesen C, Karabalut E, Korkmaz Y, Gokop S. Shear bond strength of orthodontic brackets with 3 self etch adhesives. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2006;129:547–50. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2005.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fitzgerald I, Bradley GT, Bosio JA, Hefti AF, Berzins DW. Bonding with self-etching primers–pumice or pre-etch? An in vitro study. Eur J Orthod. 2012;34:257–61. doi: 10.1093/ejo/cjq197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yonekura Y, Iijima M, Muguruma T, Mizoguchi I. Effects of a torsion load on the shear bond strength with different bonding techniques. Eur J Orthod. 2012;34:67–71. doi: 10.1093/ejo/cjq168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Montasser MA. Effect of applying a sustained force during bonding orthodontic brackets on the adhesive layer and on shear bond strength. Eur J Orthod. 2011;33:402–6. doi: 10.1093/ejo/cjq096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Iijima M, Ito S, Muguruma T, Saito T, Mizoguchi I. Bracket bond strength comparison between new unfilled experimental self-etching primer adhesive and conventional filled adhesives. Angle Orthod. 2010;80:1095–9. doi: 10.2319/012010-43.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Attar M, Taner TV, Tulumen E, Korkmaz Y. Shear bond strength of orthodontic brackets bonded using conventional vs.one and two step self etching adhesive systems. Angle Orthod. 2007;77:518–23. doi: 10.2319/0003-3219(2007)077[0518:SBSOOB]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Iijima M, Ito S, Yuasa T, Muguruma T, Saito T, Mizoguchi I. Bond strength comparison and scanning electron microscopic evaluation of three orthodontic bonding systems. Dent Mater J. 2008;27:392–9. doi: 10.4012/dmj.27.392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bishara SE, VonWald L, Laffoon JF, Warren JJ. Effect of a self-etch primer/adhesive on the shear bond strength of orthodontic brackets. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2001;119:621–4. doi: 10.1067/mod.2001.113269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bishara SE, VonWald L, Laffoon JF, Jakobsen JR. Effect of altering the type of enamel conditioner on the shear bond strength of a resin-reinforced glass ionomer adhesive. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2000;118:288–94. doi: 10.1067/mod.2000.104903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bishara SE, Gordan VV, VonWald L, Jacobsen JR. Shear bond strength of composite, glass ionomer and an acidic primer adhesive system. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1999;115:24–8. doi: 10.1016/s0889-5406(99)70312-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]