Abstract

Taxes and subsidies are increasingly being considered as potential policy instruments to incentivize consumers to improve their food and beverage consumption patterns and related health outcomes. This study provided a systematic review of recent U.S. studies on the price elasticity of demand for sugar-sweetened beverages (SSBs), fast food and fruits and vegetables as well as the direct associations of prices/taxes with body weight outcomes. Based on the recent literature, the price elasticity of demand for SSBs, fast food, fruits and vegetables was estimated to be −1.21, −0.52, −0.49 and −0.48, respectively. The studies that linked soda taxes to weight outcomes showed minimal impacts on weight; however, they were based on existing state-level sales taxes that were relatively low. Higher fast-food prices were associated with lower weight outcomes particularly among adolescents suggesting that raising prices would potentially impact weight outcomes. Lower fruit and vegetable prices were generally found to be associated with lower body weight outcomes among both low-income children and adults suggesting that subsidies that would reduce the cost of fruits and vegetables for lower-socioeconomic populations may be effective in reducing obesity. Pricing instruments should continue to be considered and evaluated as potential policy instruments to address public health risks.

Keywords: Food prices, taxes, subsidies, food consumption, body weight, body mass index, obesity

Introduction

Given the obesity epidemic in the U.S. and the escalation of associated diet-related co-morbidities, taxes and subsidies are increasingly being considered as potential policy instruments to incentivize consumers to improve their food and beverage consumption patterns and related health outcomes. In 2009–10, obesity rates among children and adults were 16.9% and 36.9%, respectively.1;2 The annual health care cost burden associated with obesity was recently estimated to be as high as $209.7 billion.3

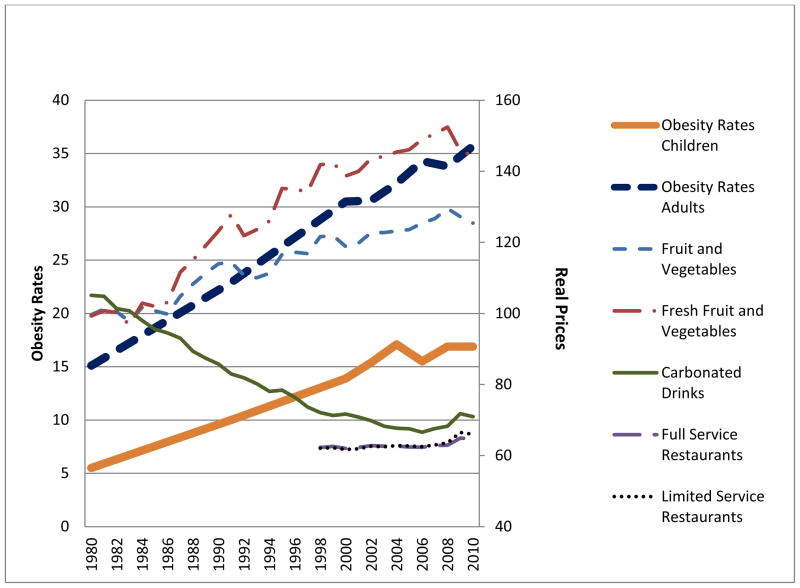

Parallel to the rise in obesity over the past few decades, the real inflation-adjusted price of fruits and vegetables has risen, while the price of carbonated soda has fallen and that of fast-food prices have remained fairly flat (Figure 1); although it should be noted that such price indices, particularly for fresh fruits and vegetables, may not account for changes in quality or variety.4 In particular, between 1980 and 2011 it became 2.2 times more expensive to purchase fresh fruits and vegetables compared to purchasing carbonated beverages.

Figure 1.

Trends in Selected Food and Beverage Prices and Obesity Rates among Children and Adults in the U.S., 1980–2011

Note: Authors' calculations based on data obtained from the Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2012.

Intakes of sugar-sweetened beverages (SSBs) and fast food have been significant contributors to increased caloric intake and higher body weight.5–7 SSBs have been identified as the leading source of added sugar and calories in the American diet.8–10 Estimates from 1988–94 to 1999–2004, show that among adults average daily caloric intake of SSBs increased from 157 to 203 kcal, with 63% of adults consuming SSBs daily.11 Over the same period, SSB intake among children aged 2 to 19 increased from 204 to 224 kcal, and was particularly prevalent (84%) among adolescents aged 12 to 19 with an average SSB intake of 301 kcal in 1999–2004.5 However, recent evidence shows that between 1999–2000 and 2007–2008 intake of sugared beverages decreased across all age groups, although sugar intake from energy drink sources rose for adults.10 Consumption of food-away-from home, particularly fast food, has increased over time across all age groups. Between 1977–78 and 1994–96, the contribution of fast food to total energy intake increased from 4% to 12% for adults and from 2% to 10% for children; and was highest among older children aged 12–19 reaching 19%.12 Recent evidence for children aged 2–19 shows that fast-food restaurant sources contributed 13% of daily energy intake by 2003–06.13 At the same time, studies show that fruit and vegetable consumption is relatively low with less than one-half of Americans meeting the USDA guidelines for fruit and vegetable intake and recent trend analyses show that there has been limited change in such intake over the last two decades.14–16

In order to incentivize healthy versus unhealthy food consumption patterns with the related aim of reducing obesity rates, taxes on SSBs and fast food have been suggested along with subsidies targeted to fruits and vegetables.17;18 Soda, other SSBs, and restaurant consumption are currently taxed in some states and localities, but at relatively low rates that were not intended to impact behavior but for revenue-generation purposes.19;20 Limited specific subsidies for fruits and vegetables have been introduced through a federal food security program.21

Standard economic theory provides a framework for using pricing instruments to alter the relative prices of less- versus more-healthful food and beverage products with the aim of changing consumer demand at the broad population level.18 A previous comprehensive review of studies of consumer demand that ranged from 2007 back to 1938 reported that, on average, a 10% increase in price would reduce consumption of soft drinks, food away from home, fruits and vegetables by 7.9%, 8.1%, 7.0% and 5.8%, respectively.22 More recent empirical studies reviewed herein suggest SSB and regular soft drink consumption to be more price sensitive than previously reported, which is particularly important given the current policy debates and legislative activity related to SSB tax proposals in jurisdictions nationwide.

Whether changes in prices for particular products result in overall weight changes hinges on both the extent to which consumption responds to own-price and the extent of cross-price effects that result in substitution across products which, in turn, affects net caloric intake and ultimately weight and obesity outcomes. Previous reviews showed that the studies that examined associations between food prices/taxes and weight outcomes found mixed or small effects suggesting that taxes would need to be significantly higher in order to translate into any meaningful changes in weight.18;23 In the US, evidence on the effectiveness of higher taxes in reducing tobacco use and its consequences has led to sharp increases in tobacco taxes and prices, with taxes accounting for nearly half of cigarette prices in recent years. These tax and price increases have contributed to significant reductions in tobacco use among youth and adults, as have mass media anti-smoking campaigns, smoke-free policies, and other tobacco control interventions. At the same time, the tax increases have generated considerable new revenues that some states have used to support tobacco use cessation and prevention efforts that have further reduced tobacco use.24

This study extends a previous review study22 to provide a systematic review of recent U.S. studies on the price elasticity of demand for SSBs, fast food, and fruits and vegetables. It also builds on prior reviews18;20 to systematically review the direct associations of prices/taxes with weight outcomes. The paper provides a detailed description of the way in which SSBs and restaurant items are currently taxed and fruit and vegetables are subsidized in the U.S. And, it provides examples of the nature and scope of current fiscal pricing proposals in the U.S. The paper concludes by outlining fiscal policy instrument designs that are likely to be the most effective for improving diet and weight outcomes and highlights areas of future work that are needed to build the evidence base.

Methods

We reviewed studies published between January 2007 and March 2012. English-language studies were identified from computer-assisted searches from the following databases: Medline, PubMed, Econlit, and PAIS. To assess the relationship of prices with consumption each of the following six terms “price elasticity,” “demand elasticity,” “tax,” “taxation,” “price,” and “prices” were separately included in searches with the combined terms of “soda” or “soft drinks” or “sugar sweetened beverages” or “beverage” or “beverages” or “fast food” and the following five terms “price elasticity,” “demand elasticity,” “subsidy,” “price,” and “prices” were each included in searches with the combined terms of “fruits” or “vegetables”. This yielded a total of 2047 studies (including duplicates) for consideration across the four databases. To assess prices and weight outcomes, the searches included the terms “price”, “prices”, “tax”, “taxation”, and “subsidy” each with the following combined terms of “obesity” or “body mass index” or “BMI” or “body weight” yielding a total of 1102 papers (including duplicates) for consideration across the four databases. In addition, research reports from the Economic Research Service (ERS) of the US Department of Agriculture were reviewed.

The criteria for including a study in this review were that the paper: (i) used US data; (ii) was a peer-reviewed study (exception for ERS studies); (iii) provided original quantitative evidence on the relationship between prices/taxes/subsidies and consumption or weight outcomes; (iv) was not an intervention study; (v) was not a pilot study; (vi) assessed demand for product categories (i.e. regular carbonated soda) rather than brands (i.e. Coke or Pepsi); and, (vii) for weight outcomes, contained direct estimates and was not a modelling study that drew on price elasticity estimates to derive simulated impacts on weight. Initial screening for relevance was based on titles, information in the abstracts, and used U.S. data. Next, based on the subset of potentially relevant papers from the initial screening, the final screening was undertaken to check whether it met our full list of inclusion criteria. The papers were reviewed independently by two study authors. A total of 21 and 20 studies met the full set of criteria for inclusion as part of the review of the effect of prices on consumption and body weight outcomes, respectively.

Consumer Demand Analysis

The aim of the consumer demand review was to provide an examination of the price elasticity of demand for (i) SSBs, including specific selected subcategories of regular carbonated soft drinks, sports drinks and fruit drinks; (ii) fast food; and, (iii) fruits and vegetables. SSBs are generally defined to include any beverage with added sugar such as regular carbonated soft drinks, fruit drinks (non-100% fruit juice), sports and energy drinks, ready to drink teas and coffees, and flavoured waters. In this review, we were particularly interested in identifying the elasticity of demand for SSBs, in general, compared to narrower sub-categories of SSBs and in distinguishing SSB demand from soft drink demand where the latter includes both regular and diet versions of soft drinks. For comparative purposes, elasticity estimates were reported for soft drinks.

Price elasticity is a common metric defined as the percentage change in quantity demanded (consumption or purchases) of a good resulting from a 1% change in the own-price of the good. Demand for a good is said to be “price inelastic” when the price elasticity is smaller than the absolute value of one and “price elastic” when its price elasticity is greater than one in absolute value. For example, an inelastic price elasticity of demand for soft drinks of −0.8 implies that the consumption of soft drinks will fall by 8% if the price of soft drinks rises by 10%. If a study presented both compensated and uncompensated price elasticity estimates, the uncompensated measure which accounts for the income effect of the price change was used. If a study reported multiple results across different populations such as low- and high-income or if it reported results based on multiple model specifications, we reported those in the detailed review presented in Table 1 and used mean estimates across models and subpopulations to derive a mean estimate which then went into the summary measures for each category reported in Table 2. To derive an overall mean estimate of the elasticity of demand for SSBs, we used all available SSB estimates from both the studies that focused on aggregated SSB measures and the estimates available for the three subcategories of SSBs (regular carbonated soda, sports drinks, and fruit drinks) and we weighted each estimate by its relative consumption share of SSBs based on caloric intake data from 24-hour dietary recalls for individuals ages two and older from the 2007–2008 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey.25

Table 1.

Evidence on Price Effects on Consumption

| Author | Price/Tax Variable [Source] | Data Set | Population (Sample size) | Model | Outcome Variable | Price Effect: Direction/ElasticityA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Panel A: Evidence for Sugar Sweetened Beverages and Soft Drinks

| ||||||

| Brown (2008)32 | Price ($/gallon) [Nielsen Retailer Scanner Data] | Nielsen Retail Scanner Data, 2003–06 | National sample of retailers (n=NRB) | Rotterdam model (two specifications) | Juice drink sales (per capita gallons) | −1.715, −1.527 |

| CSDC sales (per capita gallons) | −1.756, −1.956 | |||||

|

| ||||||

| Zheng and Kaiser (2008a)33 | Price ($/gallon) [CPID Detailed Report from BLSE] | Food Availability (Per Capita) Data System from ERSF, 1974–2005 | Aggregated US national sample (n=NR) | AIDSG, Rotterdam Model | CSD consumption per capita (gallons /person) | −0.521, −0.306 |

|

| ||||||

| Zheng and Kaiser (2008b)34 | Price ($/gallon) [CPI Detailed Report from BLS] | Food Availability (Per Capita) Data System from ERS, 1974–2005 | Aggregated US national sample (n=NR) | AIDS | CSD consumption per capita (gallons /person) | −0.609 |

|

| ||||||

| Duffey, Gordon-Larsen, Shikany, Guilkey, Jacobs, and Popkin (2010)29 | Price ($) [C2ER\ACCRAH] | CARDIAI, 1985–86, 1992–93, 2005–06 | Adults aged 18–30 in baseline year (n=5115) | Cross-sectional | RCSDJ consumption probability | −0.30 |

| RCSD consumption (kcal/day) | −0.712 | |||||

|

| ||||||

| Finkelstein, Zhen, Nonnemaker and Todd (2010)27 | Price ($)[Nielsen Homescan Data] | Nielsen Homescan Data, 2006 | National sample of households (n=NR) | Demand System | Carbonated SSB1K purchases | −0.73 |

| All SSB2L purchases | −0.87 | |||||

|

| ||||||

| Fletcher, Frisvold and Teft (2010)51 | State-level soft drink tax [LexisNexis Academic, States’ Departments of Revenue] | NHANESM, 1988–1994, 1999–2006 | Children 3–18 years old (n=20,968) | Cross-sectional | SSB3N consumption (kcal) | - |

|

| ||||||

| Fletcher, Frisvold and Tefft (2010)50 | State-level soft drink tax [LexisNexis Academic, States’ Departments of Revenue] | NHANES, 1989–1994, 1999–2006 | Children aged 3–18 (n=21,040) | Cross-sectional | SSB3 consumption probability | - |

| SSB3 consumption (grams) | - | |||||

| SSB3 consumption (kcal) | - | |||||

|

| ||||||

| Smith, Lin and Lee (2010)28 | Price ($/gallon) [Nielsen Homescan Data] | Nielsen Homescan Data, 1998–2007 | National sample of households (n=NR) | AIDS | SSB2 purchases (oz/day) | −1.264 |

|

| ||||||

| Sturm, Powell, Chriqui, and Chaloupka (2010)52 | State-level carbonated soda sales tax [BTGO] | ECLS-KP, 2004 | 5th grade children (n=7300) | Cross-sectional | SSB2 consumption (times/week) | All Students: Tax amt/ind: −/− Tax amt/ ind: −/− |

| SSB2 purchases in- school (times/week) | Available in school: Tax amt/ind: −/− Tax amt/ind: −/− |

|||||

|

| ||||||

| Zheng, Kinnucan and Kaiser (2010)35 | Price ($/gallon) [CPI Detailed Report from BLS] | USDAQ Food Disappearance Data, 1970–2004 | Aggregated US national sample (n=NR) | Linear, Semi-log, Rotterdam and AIDS model | CSD consumption per capita (gallons /person) | −0.604, −0.366, −0.428, −0.772 |

|

| ||||||

| Dharmasena and Capps (2011)30 | Price ($/gallon) [Nielsen Homescan Data] | Nielsen Homescan Data, 1998–2003 | National sample of households (n=NR) | AIDS | RCSD purchases (per capita gals/month) | −2.2552 |

| Sports/energy purchases (per capita gals/month) | −3.8650 | |||||

| Fruit drink purchases (per capita gals/month) | −0.6892 | |||||

|

| ||||||

| Lin, Smith, Lee and Hall (2011)26 | Price ($/gallon) [Nielsen Homescan Data] | Nielson National Consumer Panel R, 1998–2007 | National sample of households (n=NR) | AIDS | SSB2 purchases (grams/day) | Low income: −0.949 High income: −1.292 |

| SSB2 (calories/day) | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Sturm and Datar (2011)39 | Prices ($) [C2ER\ACCRA] | ECLS-K, 2004 | 5th grade children (n=4896) | Cross-sectional | SSB2 consumption (times/week) | + |

|

| ||||||

| Zhen, Wohlgenant, Karns and Kaufman (2011)31 | Price ($/gallon) [Nielsen Homescan Data] | Nielsen Homescan Data, 2004–06 | National sample of households (n=NR) | AIDS | RCSD purchases (oz/month) | −1.06 to −1.54 |

| Sports/energy beverage purchases (oz/month) | −0.53 to −1.52 | |||||

| Fruit drink purchases (oz/month) | −1.44 to −2.65 | |||||

|

| ||||||

|

Panel B: Evidence for Fast Food (FF)

| ||||||

| Beydoun, Powell, and Wang (2008)37 | Prices ($)[C2ER\ACCRA] | CSFIIS, 1994–96 | Adults aged 20–65 (n=7331) | Cross-sectional | FFT consumption (items/24hours) | − |

|

| ||||||

| Duffey, Gordon-Larsen, Shikany, Guilkey, Jacobs, and Popkin (2010)29 | Price ($) [C2ER\ACCRA] | CARDIA, 1985–86, 1992–93, 2005–06 | Adults aged 18–30 in baseline year (n=5115) | Cross-sectional | FF consumption probability | Pizza: −0.70; Burger: 0 |

| FF consumption (change kcal) | Pizza:−1.150; Burger: + 0.203 Pizza &Burger: − |

|||||

|

| ||||||

| Gordon-Larsen, Guilkey and Popkin (2011)40 | Price ($) [C2ER\ACCRA] | Add HealthU,, 1996 and 2001–02 | 7th–12th grade children in wave I and adults aged 18–28 in wave II (n=11,088) | Longitudinal | FF consumption (days/week) | − |

|

| ||||||

| Beydoun, Powell, Chen and Wang (2011)38 | Price ($)[C2ER\ACCRA] | CSFII, 1994–98 | Children aged 2–9 (n=6,759) | Cross-sectional | FF consumption (items/24hours) | Children: − |

| Adolescents aged 10–18 (n=1679) | Low-income children: − Adolescents: − |

|||||

|

| ||||||

| Sturm and Datar (2011)39 | Price ($) [C2ER\ACCRA] | ECLS-K, 2004 | 5th grade children (n=4896) | Cross-sectional | FF consumption (times/week) | + |

|

| ||||||

| Khan, Powell and Wada (2012)36 | Price ($) [C2ER\ACCRA] | ECLS-K, 2004, 2007 | 5th and 8th grade children (n=11,700) | Longitudinal | FF consumption (times/week) | − 0.565 |

|

| ||||||

|

Panel C: Evidence for Fruits and Vegetables (FV)

| ||||||

| Powell, Auld, Chaloupka, O’Malley and Johnston (2007) 41 | Price ($)[C2ER\ACCRA] | MTFV, 1997–2003 | 8th and 10th grade adolescents (n=47,675) | Cross-sectional | FVW consumption (prevalence of frequent consumption) | −0.08 |

|

| ||||||

| Beydoun, Powell, and Wang (2008)37 | Prices ($) [C2ER\ACCRA] | CSFII, 1994–96 | Adults aged 20–65 (n=7331) | Cross-sectional | FV consumption (grams/day) | + |

|

| ||||||

| Dong and Lin (2009)43 | Price ($)[Nielsen Homescan Data] | Nielsen Homescan Data, 2004 | National sample of households (n=NR) | Demand System | FV purchases (cups/day) | Fruit: −0.52 low income; −0.58 high income |

| Vegetable: −0.69 low income; −0.57 high income | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Powell, Zhao and Wang (2009)44 | Price ($) [C2ER\ACCRA] | NLSY97X, 2002 | Young Adults aged 18–23 (n=3739) | Cross-sectional | FV consumption (times/week) | − 0.32 |

|

| ||||||

| Lin, Yen, Dong and Smallwood (2010)42 | Price ($/lb) [National Food Stamp Program Survey] | National Food Stamp Program Survey, 1996–97 | Households using food stamps (n=900) | Translog Demand System | FV purchases ($/week) | Vegetable:−0.717 Fruit: −0.813 |

|

| ||||||

| Sturm and Datar (2011)39 | Price ($) [C2ER\ACCRA] | ECLS-K, 2004 | 5th grade children (n=4896) | Cross-sectional | FV consumption (times/week) | − 0.26 |

|

| ||||||

| Beydoun, Powell, Chen and Wang (2011)38 | Price ($) [C2ER\ACCRA] | CSFII, 1994–98 | Children aged 2–9 (n=6,759) | Cross-sectional | FV consumption (grams/day) | Children: + Adolescents: + |

| Adolescents aged 10–18 (n=1679) | ||||||

All directions and elasticity are statistically significant when in bold. Elasticity measures provided when available. Results for selected sub samples noted.

NR: Not reported

CSD: Regular and diet carbonated soft drinks

CPI: Consumer price index

BLS: Bureau of Labor Statistics

ERS: Economic Research Service

AIDS: Almost Ideal Demand System

C2ER\ACCRA: Council for Community and Economic Research formerly American Chamber of Commerce Researchers Association

CARDIA: Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults

RCSD: Regular carbonated soft drinks

SSB1: Regular carbonated soft drinks

SSB2: Regular carbonated soft drinks, sports/energy drinks, and fruit drinks

NHIS: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey

SSB3: Non-alcoholic beverages with added natural or artificial sweeteners (carbonated & non-carbonated)

BTG: Bridging the Gap- Robert Johnson Foundation-supported project, Health Policy Center, University of Illinois at Chicago

ECLS-K: Early Childhood Longitudinal Study- Kindergarten cohort 1998

USDA: United States Department of Agriculture

Also formerly known as Nielsen Homescan Data

CSFII: Continuing Survey of Food Intakes by Individuals

FF: Fast Food

Add Health: National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health

MTF: Monitoring the Future Survey

FV: Fruits and Vegetables

NLSY97: National Longitudinal Study of Youth 1997

Table 2.

Mean Estimates of Price Elasticity of Demand for Selected Beverages, Fast Food and Fruits and Vegetables, 2007–2012.

| Food and Beverage Category | Mean Price Elasticity Estimate | Range | No. of Estimates |

|---|---|---|---|

| Panel A: Sugar-Sweetened Beverages (SSBs and Soft Drink Beverages) | |||

| SSBs Overalla | −1.21 | −0.71 to −3.87 | 12 |

| SSBs | −1.08 | −0.87 to −1.26 | 3 |

| Regular Carbonated Soft Drinks | −1.25 | −0.71 to −2.26 | 4 |

| Sports Drinks | −2.44 | −1.01 to −3.87 | 2 |

| Fruit Drinks | −1.41 | −0.69 to −1.91 | 3 |

| Soft Drinks | −0.86 | −0.41 to −1.86 | 4 |

| Panel B: Fast Food | |||

| Fast Food | −0.52 | −0.47 to −0.57 | 2 |

| Panel C: Fruits &Vegetables | |||

| Fruits | −0.49 | −0.26 to −0.81 | 4 |

| Vegetables | −0.48 | −0.26 to −0.72 | 4 |

Notes: a: Overall mean (weighted mean based on SSB consumption shares) SSB elasticity estimate based on the estimates from the aggregated SSB category and the estimates from the various disaggregated (regular carbonated soda, sports drinks, and fruit drinks) categories within the beverage demand system.

Body Weight Analysis

The aim of this review of studies that examined prices and weight outcomes was to assess the extent to which changes in food or beverage prices have the potential to translate into significant changes in body weight. These studies can be thought of as reduced form studies that assess the direct effect on weight implicitly accounting for all changes in food consumption including substitution across food products. Weight outcomes were measured by, body weight, body mass index (BMI; weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared), and obesity prevalence (BMI ≥ 30 for adults and defined by age-and gender -specific BMI ≥ 95th percentile for children). We assessed direction, magnitude, and significance of associations. If available, price elasticity estimates of weight outcomes were reported.

Results

SSB Consumer Demand

As shown in Panel A of Table 1, the review identified 14 studies that estimated price effects for SSB and soft drink demand with 10 studies that provided price elasticity of demand measures. Four studies provided estimates of soft drink demand that combined regular (calorically-sweetened) and non-caloric soft drinks using retail scanner data. Three papers used annual national time series data. Five papers were based on individual-level survey data, four of which did not provide price elasticity estimates.

Summary measures of mean price elasticities for SSBs overall and by each beverage category are presented in Table 2. The results suggest that SSBs are more price elastic than implied by the previously reported estimate of −0.79 for soft drinks which included regular and diet soft drinks.22 The estimated overall mean price elasticity of demand for SSBs was −1.21. This estimate was based on all 12 available SSB elasticity estimates including those for the aggregated SSB measures and those estimates available for each of the three subcategories of SSBs (regular soft drinks, sports drinks, and fruit drinks) where each estimate was weighted by its relative consumption share of SSBs. The mean SSB price elasticity estimate of −1.21 implies that a tax that raises the price of SSBs by 20% would reduce overall consumption of SSBs by 24%.

As summarized in Table 2, based on the three studies that included an aggregated SSB category within the beverage demand system, the price elasticity of SSBs was −1.08 (range of −0.87 to −1.26).26–28 Consistent with economic theory, the estimates from models that separately assessed subcategories of SSBs generally were found to be more price elastic. The mean price elasticity of demand for regular carbonated soda of −1.25 (range −0.71 to −2.26)27;29–31 suggested that a 20% increase in price would reduce consumption by 25%. Only two studies provided specific estimates for sports drinks with an average elasticity of −2.44 (range −1.01 to 3.87)30;31 and three studies assessed fruits drinks with a mean elasticity of −1.40 (range −0.69 to −1.91).30–32 With respect to model specification, all but one29 of the SSB elasticity measures reported in Table 1 were based on estimates from demand system models. The one study on regular carbonated soda that was not based on a demand system yielded the lowest estimated elasticity. Excluding this study increased the mean elasticity of demand for regular carbonated soda from −1.25 to −1.44 and increased the overall mean SSB elasticity from −1.21 to −1.27.

Four recent studies assessing soft drink demand aggregated both regular and artificially-sweetened soft drinks and one study included bottled water.32–35 Using such estimates to assess the potential impact of SSB taxes would not be appropriate given that SSB-specific taxes would not be applied to non-SSB soft drinks. If consumers faced higher prices for both SSB and non-SSB soft drinks they are likely to reduce overall soft drink demand to a lesser extent than demand for regular soft drinks would be reduced in response to a tax on regular soft drinks only, given that they would be unable to substitute to a lower priced non-caloric alternative soft drink. Indeed, the estimated price elasticity of demand for soft drinks based on our review was inelastic at −0.86 which was similar to the previous soft drink estimate of −0.79.22

Fast Food Consumer Demand

As shown in Panel B of Table 1, six studies provided price parameter estimates for fast-food consumption. All six studies merged fast-food price data available from the Council for Community and Economic Research (C2ER) formally known as the American Chamber of Commerce Researchers Association (ACCRA) to individual-level survey data using geographic identifiers and the majority (4 of 6) of the studies estimated cross-sectional models. Only two29;36 of the six studies reported price elasticity estimates with a mean elasticity of −0.52 which is lower than the food away from home estimate of −0.81 reported previously.22 The elasticity estimates from one study that examined adults found that higher fast-food pizza prices (−1.15) but not burger prices (0.20) were associated with significantly lower consumption (based on caloric intake)29 and another study found fast-food prices were negatively associated with consumption but the parameter estimates were not statistically significant.37 Among a sample of children, higher fast-food prices were associated with significantly lower frequency of weekly fast-food consumption (−0.52).36 Overall, there were mixed results among the studies on children with two finding significant negative associations36;38 but one finding an unexpected positive association.39 Two studies that included adolescent populations found negative but statistically insignificant effects.38;40

Fruit and Vegetable Consumer Demand

Panel C of Table 1 summarizes the seven studies that provided price estimates for fruits and vegetables. Two studies did not report price elasticities nor did they find statistically significant associations between prices and fruit and vegetable consumption.37;38 Table 2 reports that the mean price elasticity for fruit and vegetables was −0.49 and −0.48, respectively. The one study that examined the probability of frequent consumption rather than a continuous or count of consumption was not included in the overall summary estimate.41 The studies with estimates based on demand system models yielded relatively higher elasticity estimates of −0.52 to −0.81 for fruits and −0.57 to −0.72 for vegetables.42;43 The two studies that had outcome measures that combined fruits and vegetables had the lowest prices elasticity estimates of −0.26, and −0.32.39;44

Weight Outcomes

Table 3 summarizes the 20 studies identified that examined the relationship between weight outcomes and SSB, fast-food restaurant or fruit and vegetable prices/taxes from 2007 to 2012, parallel to the period of our consumption review. Building on our previous reviews18;20, fifteen are new studies published after 2008, ten of which have been published since 2009. Also, it is worth noting that adding the search term “body weight” in addition to body mass index, BMI and obesity used in our previous review work yielded two additional papers in this review that otherwise would not have been retrieved. Another recent review45 that covered five of the fifteen weight-related studies published from 2009 through 2012 reported coefficient estimates, whereas we report elasticities when available. Other recent reviews provide international evidence and focus to a large extent on studies that use price elasticities to simulate effects on weight outcomes.23;46 The weight outcome papers in this present review all used individual-level survey data that were directly linked to prices or taxes by geographic identifiers. Thirteen studies drew their price data from C2ER/ACCRA, one from the Economic Research Service (ERS) Quarterly Food-at-Home Price Database (QFAHPD), and one from the Bureau of Labor Statistics Consumer Price Index series, and five studies used state-level soda taxes. Even if included in the models as controls, we did not report on price effects for items such as general food at home price indices, general food-away from-home prices or full-service restaurant prices since the focus of this review was on evidence for SSBs and fast food as possible items for taxation and fruits and vegetables as candidates for subsidies. Overall, eleven of the studies were cross-sectional and nine used longitudinal estimation methods to control for unobserved individual-level heterogeneity. The study findings for the seven papers on adults are described in Panel A and Panel B presents the 13 papers focused on child and adolescent populations.

Table 3.

Evidence on Price Effects on Body Weight Outcomes

| Author | Price/Tax Measure [Source] | Data Set | Population (Sample size) | Model | Outcome Measure | Evidence for Tax Effects- Fast Food Prices and Sugar Sweetened Beverage prices/taxes: Direction/ElasticityA | Evidence for Subsidy Effects-Fruit and Vegetable Prices: Direction/ElasticityA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Panel A: Evidence for Adults

| |||||||

| Beydoun, Powell, and Wang (2008)37 | Prices ($) of fast food and fruits and vegetables [C2ER\ACCRAB] | CSFIIC, 1994–1996 | Adults aged 20–65 (n=7331) | Cross-sectional | BMID | FFPE: + | FVPF

: − FVP: - near poor |

| Obesity | FFP: + | FVP: − FVP: - near poor |

|||||

|

| |||||||

| Schroeter and Lusk (2008)56 | Prices ($) of fast food, [state-level BLSG CPIH series] | BRFSSI, 2003 | Adults aged 18 and older (n=202,323) | Cross-sectional | BMI | FFP: −0.044, quadratic | N/AJ |

| Weight | FFP: −0.044, log-linear FFP: −0.036, translog |

||||||

|

| |||||||

| Fletcher, Frisvold and Tefft (2010)47 | State-level soft drink tax [LexisNexis Academic, States’ Departments of Revenue] | BRFSS, 990–2006 | Adults aged 18 and older (n=2,709,422) | Cross-sectional | BMI | SDTK: - (- in 17 subpopulations) | N/A |

| Obese | SDT: - (- in 9 subpopulations) | ||||||

| Overweight | SDT: - (- in 15 subpopulations) | ||||||

|

| |||||||

| Han and Powell (2011)48 | Prices ($) of regular carbonated soft drinks and fruits and vegetables [C2ER\ACCRA] | MTFL, 1992–2003 | Young adults 12th grade through age32 (n=5324 men and 6537 women) | Longitudinal | Obese | FFP: − men REM; − men FEN FFP: − women RE; − women FE RCSDPO: + men RE; + men FE RCSDP: − women RE; + women FE |

FVP: − men RE; − men FE FVP: − women RE; − women FE |

|

| |||||||

| Powell and Han (2011)55 | Prices ($) of fast food and fruits and vegetables [C2ER\ACCRA] | PSIDP1999, 2001, 2003, 2005 | Adults aged 18–65 years old (n=17,479 men and 19,747 women) | Cross-sectional and Longitudinal | BMI | FFP: − men, CSQ; + men FE FFP: − women CS; + women FE |

FVP: + men CS; + men FE FVP: + women CS; + 0.02, women FE FVP: + 0.09, poor women FE; + 0.03, women with children FE |

|

| |||||||

| Zhang, Chen, Diawara and Wang (2011)57 | Prices ($) of fast food [C2ER\ACCRA] | NLSY79R, 1985–2002 | Female adults aged 20–45 eligible for SNAPS (n=6622) | Longitudinal | BMI |

Non-SNAPS

participants: FFP: + RE; + FE; − RE IV; − FE IV SNAP vs Non-SNAP: FFP: − RE; − FE; − RE IV; − FE IV |

N/A |

| Obesity |

Non-SNAP participants: FFP: + RE; + FE; + RE IV; + FE IV SNAP vs Non-SNAP: FFP: +RE; +FE; + RE IV; + FE IV |

||||||

|

| |||||||

| Han, Powell and Isgor (2012)54 | Prices ($) of fast food and fruits and vegetables [C2ER\ACCRA] | PSID, 1999, 2001, 2003 | Low-income adults aged 18–65 (n=1351 men and 2391 women) | Cross-sectional and Longitudinal | BMI |

Non-SNAP participants: FFP: − men CS; − men FE FFP: − women CS; + women FE |

Non-SNAP participants: FVP: + men CS; − men FE FVP: + women CS; + women FE SNAP vs Non-SNAP: FVP: + men CS; + men FE FVP: + women CS; + women FE |

| Obesity |

Non-SNAP participants: FFP: − men CS; − men FE FFP: − women CS; − women FE |

Non-SNAP participants: FVP: − men CS; − men FE; FVP: + women CS; + women FE |

|||||

|

| |||||||

|

Panel B: Evidence for Children and Adolescents

| |||||||

| Powell, Auld, Chaloupka, O’Malley and Johnston (2007)41 | Prices ($) of fast food and fruits and vegetables [C2ER\ACCRA] | MTF, 1997–2003 | Adolescents in 8th and 10th grade (n=72,854) | Cross-sectional | BMI | FFP: − 0.04 | FVP: + |

| Overweight | FFP: − 0.59 | FVP: + | |||||

|

| |||||||

| Chou, Rashad, and Grossman (2008)58 | Price ($) of fast food [C2ER\ACCRA] | NLSY79, 1996, 1998, and 2000 | Children aged 3–11 years (n=6034) | Cross-sectional | BMI | FFP: − children FFP: − adolescents FFP: − adolescent female |

N/A |

| NLSY97T, 1997–1999 | Adolescents aged 12–18 years (n=7069) | Overweight | FFP: − children FFP: − children female FFP: − adolescents |

N/A | |||

|

| |||||||

| Sturm and Datar (2008)63 | Price (S) of fruits and vegetables [C2ER\ACCRA] | ECLS-KU, 1998–2004 | Children K through 5th grade (n=4557) | Longitudinal | BMI | N/A | FVP: + |

|

| |||||||

| Auld and Powell (2009)59 | Prices ($) of fast food and fruits and vegetables [C2ER\ACCRA] | MTF, 1997–2003 | Adolescents in 8th and 10th grade (n=34,451 male, 38,590 female) | Cross-sectional | BMI | FFP: − 0.03 male FFP: − 0.10 male at 90th quantile FFP: −0.03 female FFP: − 0.11 female at 90th quantile |

FVP: + 0.01 male FVP: + 0.05 male at 95th quantile FVP: +0.03 female FVP: +0.03 female at 50th quantile; +0.04 female at 90th quantile; + 0.06 female at 95th quantile |

|

| |||||||

| Powell (2009)60 | Price ($) of fast food [C2ER\ACCRA] | NLSY97, 1997–2000 | Adolescents aged 12–17 in 1997 (n=11,900) | Cross-sectional and longitudinal | BMI | FFP: − 0.10 CS; − 0.08 RE; − 0.08 FE FFP: − 0.13 mother low education FE; − 0.31 middle income FE |

N/A |

|

| |||||||

| Powell and Bao (2009)62 | Prices ($) of fast food and fruits and vegetables [C2ER\ACCRA] | NLSY79, 1998–2002 | Children aged 6–18 (n=6594) | Longitudinal | BMI | FFP: − 0.07 FFP: − 0.26 low income; − 0.13 mother low education |

FVP: + 0.07 FVP: + 0.14 low income; + 0.09 mother low education |

|

| |||||||

| Powell, Chriqui, and Chaloupka (2009)49 | State-level carbonated soda sales tax (Grocery store & VMV) [BTGW] | MTF, 1997–2006 | Adolescents aged 13–19 (n=153,673) | Cross-sectional | BMI | Grocery CSTX: + VM CST:+ |

N/A |

|

| |||||||

| Fletcher, Frisvold and Tefft (2010)50 | State-level soft drink tax [Council of State Governments, LexisNexis Academic] | NHANESY, 1989–1994, 1999–2006 | Children aged 3–18 (n=22,132) | Cross-sectional | BMI z-score | SDT: + | N/A |

| Obese | SDT: + | ||||||

| Overweight | SDT: + | ||||||

| Underweight | SDT: − | ||||||

|

| |||||||

| Fletcher, Frisvold and Tefft (2010)51 | State-level soft drink tax [LexisNexis Academic, States’ Departments of Revenue] | NHANES, 1988–1994, 1999–2006 | Children 3–18 years old (n=20,968) | Cross-sectional | BMI z-score | SDT: + | N/A |

| Obese | SDT: + | ||||||

|

| |||||||

| Sturm, Powell, Chriqui, and Chaloupka (2010)52 | State-level carbonated soda sales tax [BTG] | ECLS-K, 2004 | Children in 5th grade (n=7300) | Cross-sectional | BMI | CST: − CST: - at risk of overweight |

N/A |

|

| |||||||

| Beydoun, Powell, Chen and Wang (2011)38 | Prices ($) of fast food and fruits and vegetables [C2ER\ACCRA] | CSFII, 1994–1998 | Children aged 2–9 (n=6759) Adolescents aged 10–18 (n=1679) |

Cross-sectional | BMI | FFP: − children FFP: + adolescents |

FVP: + children FVP: + children low income FVP: − adolescents |

|

| |||||||

| Powell and Chaloupka (2011)61 | Prices ($) of fast food and fruits and vegetables [C2ER\ACCRA] | CDS-PSIDZ, 1997 and 2002/2003 | Children aged 2–18 (n=1629) | Cross-sectional and Longitudinal | BMI | FFP: − 0.16 CS; + 0.24 FE FFP: − 0.77 low income CS |

FVP: + 0.24 CS; + 0.25 FE FVP: + 0.60 low income, FE |

|

| |||||||

| Wendt and Todd (2011)53 | Prices ($) of carbonated beverages, fruit drinks and green vegetables [QFAHPDAA] | ECLS-K, 1998–2007 | Children K through 8th grade (n=51,160) | Cross-sectional and Longitudinal | BMI | CBPAB: − 0.03 CS; −0.04 FE CBP: −0.06 male FE; −0.09 near- poor FE; −0.03 white FE; −0.07 Hispanic FE; −0.03 children metro areas FE CBP: −0.03 at 25th quantile FE; − 0.03 at 50th quantile FE FDPAC:: +0.00 CS; −0.01 FE FDP: −0.02 at 25th quantile FE; −0.01 at 50th quantile FE |

GVPAD: +0.05 CS; + 0.01 FE GVP: +0.03 female FE; −0.07 near-poor FE; +0.02 children metro areas FE GVP: +0.04 at 50th quantile FE; +0.08 at 85th quantile FE SVPAE: −0.03 CS; −0.03 FE SVP: −0.04 male FE; −0.02 female FE; −0.04 white FE; − 0.03 poor FE SVP: −0.04 at 25th quantile FE; −0.02 at 50th quantile FE |

All directions and elasticity are statistically significant at 5% or 1% level when in bold. Elasticity measures provided when available. Results for selected sub-samples noted when statistically significant.

C2ER\ACCRA: Council for Community and Economic Research formerly American Chamber of Commerce Researchers Association

CSFII: Continuing Survey of Food Intakes by Individuals

BMI: Body Mass Index

FFP: Fast food price

FVP: Fruit and vegetable price

BLS: Bureau of Labor Statistics

CPI: Consumer Price Index

BRFSS: Behavior Risk Factor Surveillance System

N/A: Not Available

SDT: Soft drink tax- “Soft drinks” are defined broadly to include non-alcoholic, artificially sweetened or “diet” drinks and carbonated water.

MTF: Monitoring the Future Survey

RE: Longitudinal individual-level random effects

FE; Longitudinal individual-level fixed effects

RCSDP: Regular carbonated soft drink price

PSID: Panel Study of Income Dynamics

CS: Cross sectional model

NLSY79: National Longitudinal Study of Youth 1979

SNAP: Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program

NLSY97: National Longitudinal Study of Youth 1997

ECLS-K: Early Childhood Longitudinal Study- Kindergarten cohort 1998

VM: Vending Machine

BTG: Bridging the Gap- Robert Johnson Foundation-supported project, Health Policy Center, University of Illinois at Chicago

CST: Carbonated soda sales tax

NHANES: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey

CDS-PSID: Child Development Supplement – Panel Study of Income Dynamics

QFAHPD: Quarterly Food-at-Home Price Database

CBP: Carbonated beverage price

FDP: Fruit drink price

GVP: Green vegetable price

SVP: Starchy vegetable price

Overall, the evidence on the extent to which changes in food or beverage prices may significantly impact weight outcomes remains mixed. A recent study that examined associations between existing soda sales taxes and weight outcomes among adults found statistically significant but small associations,47 whereas a study of young adults found no significant association between obesity and the price of regular carbonated soft drinks.48 The studies that assessed associations between existing soda sales taxes and children’s or adolescents’ weight outcomes found no or limited associations with weight outcomes.49–52 Just one study found that higher soda sales taxes were significantly associated with lower weight gain, particularly among those children who were overweight.52 Another study that examined carbonated beverage prices rather than taxes found that higher prices were statistically significantly related to lower BMI among children in a longitudinal model.53 Further, this latter study found that the negative relationship between carbonated beverage prices and BMI were greater for near-poor compared to poor and non-poor children and greater for Hispanic and white compared to black children but did not find differential effects across the BMI distribution.53

Among adults, the six recent studies identified that examined fast-food prices generally found statistically insignificant associations with weight outcomes.37;48;54–57 However, one study found that among adults who were eligible for the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) higher fast-food prices were significantly associated with lower BMI among SNAP versus non-SNAP recipients.57 For adolescents, among the five studies that examined associations of weight outcomes with fast-food prices, there was fairly consistent evidence (in four out of five studies) that suggested that higher fast-food prices were significantly associated with lower weight outcomes, particularly among those who were low- to middle-SES and in the upper tail of the BMI distribution.41;58–60 Further, the associations between fast-food prices and weight outcomes were generally found to be significant in longitudinal estimations models that controlled for individual-level fixed effects; although, the cross-sectional versus longitudinal estimate was shown to over-estimate the association by about 25%.60 No significant effect of fast-food prices on younger children’s (age 2–9) BMI was found overall or among lower-income children in one study38 and in another study of children aged 2–18 the effect among low-income children was significant in the cross-sectional analysis but not in the longitudinal analysis.61 However, one longitudinal study of children aged 6–18 found that higher fast-food prices were statistically significantly associated with lower BMI among low-socioeconomic status children.62

The potential effect of reducing adult weight through subsidies to fruits and vegetables was mixed for the adult population overall but significant effects were found for female adults, including in longitudinal models, with larger effects for poor women and those with children.55 Further, one study found that reductions in the price of fruits and vegetables would decrease BMI significantly more for SNAP participants than non-SNAP participants.54 These findings are particularly pertinent to the policy debate given that subsidies are likely to be targeted to low-income or SNAP participants. Further, in all of the studies that examined child populations38;53;61–63 (with the exception of two individual fixed effects estimates) and in all but two studies38;41 focused on adolescents, lower fruit and vegetable prices were consistently estimated to be associated with lower weight outcomes. One study53 that drew price data from the ERS QFAHPD which was able to distinguish dark green versus starchy vegetable prices found that higher prices for dark green vegetables was positively associated with children’s BMI, whereas higher prices for starchy vegetables had the opposite effect. In general, the evidence suggested that fruit and vegetable subsidies would have the greatest effects on improving weight outcomes among children and adolescents from low-SES families38;53;61;62 and among those in the upper tail of the BMI distribution.53;59

Current and Proposed Food and Beverage Fiscal Pricing Policies

No jurisdictions in the United States currently apply sizeable taxes (i.e. in the order of 20% as have been recently proposed) to SSBs or fast-food purchases and subsidies for fresh fruit and vegetable purchases are often limited in scope or magnitude and are not readily available nationwide. The following discussion summarizes where the current system of taxation and subsidies stand and provides examples of recent policy proposals.

A patchwork system of food and beverage taxation exists in the United States. Currently, there are no federal taxes on foods and/or beverages, and some, but not all, states and localities apply relatively small taxes at variable rates.19;64 Most food and beverage items are exempt from state sales taxes or are included in a general definition of food products that, when taxed, are taxed at a markedly lower rate than sales taxes applied to other goods and services.20

For the most part, any foods or beverages purchased in a restaurant, including both fast-food restaurants and full-service or sit-down establishments, follow the general state sales tax scheme. The few exceptions are in the District of Columbia, New Hampshire, and Vermont — each applies a restaurant-specific tax that is higher than the state’s general sales tax (i.e., restaurant taxes of 10%, 8%, and 9%, respectively). As of the beginning of 2012, the average state sales tax on restaurant (including fast food) sales was 5.31 percent across all states and the District of Columbia and was 5.76 percent in the 47 states with such a tax.65

As Table 4 illustrates, state sales taxes on beverages vary greatly by beverage category. For example, as of January 1, 2012, 35 states apply their sales tax to regular and diet carbonated beverages, while 31 states tax isotonic beverages or sports drinks and 28 tax ready-to-drink teas which often contain added sugars. Across all states, the average sales taxes on beverages range from 3.55 percent for regular and diet sodas to 0.99 percent on 100-percent juices; in taxing states, the average rates range from 5.17 percent for regular and diet carbonated beverages to 3.59 percent for 100-percent juices.65 As the table illustrates, the taxes on some beverage categories are higher than food products generally and, thus, they are considered “disfavored” relative to other food products.19;20;66 Notably, none of the revenues generated from beverage sales taxes are dedicated to obesity prevention efforts or programs.

Table 4.

State sales taxes on selected beverages as of January 1, 2012 (Source: Bridging the Gap Program 2012)

| Type of beveragea | State Sales Taxes on Beverages | Disfavoredc Sales Taxes on Beverages | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| # states applying a sales tax to beverage | Mean sales tax, taxing states only | Mean sales tax, all statesb | # states with a disfavored sales tax | Mean disfavored sales tax, taxing states only | Mean disfavored sales tax, all statesb | |

| Regular soda | 35 | 5.17 | 3.55 | 23 | 5.68 | 2.56 |

| Diet soda | 35 | 5.17 | 3.55 | 23 | 5.68 | 2.56 |

| Isotonic beverages (sports drinks) | 31 | 5.07 | 3.08 | 19 | 5.63 | 2.10 |

| <50% juice | 30 | 5.04 | 2.97 | 18 | 5.61 | 1.98 |

| Ready-to-drink teas | 28 | 5.01 | 2.75 | 16 | 5.68 | 1.77 |

| Bottled water | 18 | 3.85 | 1.36 | 4 | 4.75 | 0.37 |

| 51–99% juice | 16 | 3.77 | 1.18 | 2 | 5.00 | 0.20 |

| 100% juice | 14 | 3.59 | 0.99 | 0 | -- | -- |

Type of beverage assumes beverages available for individual purchase from a supermarket/grocery store.

All states includes the 50 states and the District of Columbia.

Disfavored sales tax refers to the amount of the given beverage sales tax that is greater than the state sales tax on food items generally.

At the same time, in addition to sales taxes, seven states — Alabama, Arkansas, Rhode Island, Tennessee, Virginia, Washington, and West Virginia — currently impose other types of taxes or levy fees for the sale of certain beverages.19;20;65;67 These additional taxes generally apply to bottles, syrups, and/or powders/mixes and are targeted at various levels of the distribution chain, including wholesalers, bottlers, manufacturers, and distributors; however, none of the revenue generated from these additional taxes/fees is currently dedicated to obesity prevention programming. With the exception of the license fees and taxes imposed on manufacturers, wholesalers, and/or retailers in Alabama (Ala. Code §§ 40-12-65, -69, -70 [2010]), most of these additional taxes or levies are based on volume of beverage (typically in gallons).19;20

In recent years, a number of jurisdictions have proposed placing sizeable and specific excise taxes on SSBs as recommended in the above-mentioned literature and, most recently, by the Institute of Medicine.68 The impetus behind such taxes generally is based on the fact that, as noted earlier, SSBs are the leading source of calories and added sugars in the American diet and that over-consumption of SSBs is associated with obesity, combined with the budgetary shortfalls faced by governments nationwide. Table 5 illustrates a few such examples from 2012 alone (although, to date, none have been enacted into law). While each of the examples included in Table 5 aims to dedicate a portion of the revenue generated from the tax to health-related programs, none are specifically calling for funding obesity-specific programs as recommended by the public health community.17

Table 5.

Examples of state excise tax-related proposals with legislative action during calendar year 2012

| Statea | Bill Number | Proposed Tax/Fee | Proposed Revenue Dedication |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hawaii | S.B. 2480 | $0.01 per teaspoon of added sugar | Revenues would be dedicated to community health centers special fund, the trauma system special fund, and establish the John A. Burns School of Medicine medical loan forgiveness program special fund |

| Illinois | S.B. 396 | $0.01 per ounce | Revenues would be used to create the Illinois Health Promotion Fund |

| Mississippi | S.B. 2642 | $2.56 per gallon of sweetened beverage produced or $.02 per ounce | 20% of revenue would go to the Children’s Health Promotion Fund |

| Vermont | H.B. 615 | $0.01 per ounce | Revenue would be used t to create the Vermont Oral Health Improvement Fund |

State examples were identified through the Yale Rudd Center for Food Policy & Obesity Legislative Database available at http://www.yaleruddcenter.org/legislation/search.aspx (Last Access: May 24, 2012)

Subsidies available for food in the U.S. have not generally been designed with the aim to change consumption patterns but rather to alleviate food insecurity for low-income individuals and families through programs such as the SNAP; the Women, Infant and Children (WIC) Nutrition Program; the Child and Adult Care Food Program; and the National School Lunch and Breakfast Programs. However, there have been some recent changes that were made, for instance, to the WIC program that added monthly cash value vouchers specifically for fruits and vegetables in the amount of $10 for fully breast-feeding women, $8 for non-breast-feeding women, and $6 for children.21 In addition, recent changes have been made to the national school breakfast and lunch programs to ensure that all foods and beverages sold/served are aligned with the latest scientific evidence and the 2010 Dietary Guidelines for Americans.69 The new regulations, effective as of the the 2012–2013 school year, will ensure that school meals will offer more fruits and vegetables, more whole grains, only fat-free or low fat milk, less sodium, and will limit the number of calories to within a range appropriate for each of three grade groupings.70 At the same time, as part of the congressionally mandated wellness policy required of all school districts in the United States participating in the federal school meal programs (P.L. 108–265, Section 204), some districts have taken specific steps to require a minimum number of fruits and vegetables, whole grains, and skim/low-fat milk daily as part of the school meal offerings.71

Although no formal subsidies for fruits and vegetables beyond those in the WIC package presently exist in the U.S., the potential provision of providing such subsidies more broadly for low-income populations is increasingly being assessed. The USDA undertook a “Healthy Purchase” pilot program in California that targeted subsidies within the SNAP program such that for each dollar of food stamps spent on fresh produce, participants were subsidized a portion of the cost.72 Currently, the USDA is undertaking the Healthy Incentives Pilot project in Hampden County, Massachusetts to test whether point-of-sale subsidies provided to SNAP participants increases purchases of fruits and vegetables.73

Discussion

The recent studies reviewed from 2007 to 2012 showed that the empirical evidence on prices, food and beverage demand, and weight outcomes continues to emerge. Our search yielded a total of 21 recent consumption-related papers and 20 weight-related studies. Most of the SSB related consumption papers were based on models of demand systems and provided elasticity estimates, whereas the methods and outcomes in studies for fast food and fruits and vegetables were more varied. An increasing number of currently reviewed weight papers used longitudinal estimation methods (almost one half), whereas the evidence base previously reviewed was mainly comprised of cross-sectional or modeling studies18;20;23. Studies that provided both cross-sectional and longitudinal estimates53–55;60;61 revealed that the associations mostly but not always remained statistically significant in the longitudinal models. However, the longitudinal fixed effects estimates showed that the cross-sectional estimates often over-estimated the associations highlighting the importance of controlling for individual-level unobserved heterogeneity.

This review is timely given the recent recommendations by the IOM Committee to Accelerate Progress in Obesity Prevention that suggested consideration be given to fiscal pricing instruments for beverages.68 The new evidence presented herein suggested that SSBs are price elastic and that a tax that raises prices by 20% would reduce SSB consumption by 24% (elasticity of −1.21). As expected, narrower categories of SSBs were found to be more price elastic with elasticity estimates for regular carbonated soda, sports drinks and fruit drinks of −1.25, −2.44, and −1.41, respectively. Soft drink demand was estimated to be less price elastic (−0.86), consistent with previous available estimates.22 However, studies that aim to assess the potential impact of existing SSB or regular soda/soft drink taxes should not draw on soft drink elasticity estimates since they typically include diet alternatives which would not likely be included as part of the tax base for a SSB-specific tax.

Despite evidence on the price responsiveness of SSB and carbonated soda consumption, the studies that linked existing soda sales taxes to weight outcomes showed the least consistent impact on weight, although one study53 that used a carbonated beverage price rather than tax measure found a significant association with children’s weight. The results based on studies that used existing tax measures are not surprising given that current taxes imposed, primarily state-based sales taxes, are relatively low. All 35 states that apply a sales tax to regular, sugar-sweetened soda also apply the sales tax to diet varieties and fewer states apply their sales taxes to other SSBs although a number of jurisdictions in recent years have considered imposing sizeable excise taxes specifically on SSBs which, if enacted, could lead to reduced SSB consumption and improved weight outcomes, particularly at the broad population level. In addition to the magnitude of the tax, the design of a given SSB tax is important to ensure its effectiveness in incentivizing behavior change. In this regard, several key arguments can be made in favor of an excise versus a sales tax, regardless of whether the tax is at the federal, state, or local level.20 Excise taxes have the benefit of being incorporated into the shelf price of the given product (and, hence, are part of the visible price seen by consumers), whereas a sales tax is only applied at the point of purchase, after the decision to select and purchase the item has been made. Excise taxes that are applied on a per unit measure are more effective in raising prices when volume discounts are given, compared to sales taxes that generally are applied as a percentage of price. Finally, consideration should be given to the harmonization between tax policies and broader public program design as it is preferable not to have certain segments of the population exempt from the given tax as is currently the case where food or beverage purchases under the SNAP are exempt from any state and local-level tax (7 CFR §272.1).

A smaller body of evidence examined price effects on fast-food consumption and the limited number of price elasticity estimates available suggested that consumption was price inelastic with an average estimate of −0.52, suggesting that a tax that raised the price of fast food by 20% would reduce consumption by about 10%. Previous studies similarly found that food away from home was price inelastic with a mean estimated price elasticity of −0.81.22 Nonetheless, such a tax could have large implications at the population level given the extent of caloric intake from fast food among the U.S. population, particularly among youths. Indeed, the review of fast-food prices and weight outcomes revealed that there was fairly consistent evidence suggesting that higher fast-food prices would reduce body weight among adolescents.

However, taxing fast-food consumption is more challenging than taxing a specific category of beverages. Fast-food restaurants often sell a variety of food and beverage items including both healthy options (e.g., salads and bottled water) as well as other options that tend to be high in fats, sugars, and calories; however, given the prevalence of fast-food consumption in the US and its association with increased BMI, fiscal policies including specific excise taxes and subsidies, should be considered to ensure that a variety food and beverage options are available and that healthier options that are lower in fats, calories, and added sugars are readily available, promoted, and competitively priced at such outlets.68

The evidence for fruits and vegetables showed that consumption was price inelastic with a mean estimated price elasticity of demand for fruits at −0.49 and vegetables at −0.48, suggesting that subsidizing fruits and vegetables by 20% would increase consumption by 10%. The evidence that linked prices to weight outcomes demonstrated fairly consistent findings that lower fruit and vegetable prices were associated with lower body weight among low-income populations, including SNAP participants. These results also suggest that the income effect of the subsidy would not likely result in higher overall net caloric intake. The weight-related evidence base for fruit and vegetable prices has grown substantially since our previous reviews18;20 including an increasing number of studies that used longitudinal data. The consistent findings provide increased evidence on the potential effectiveness of using fruit and vegetable subsidies targeted to low-income populations. Also, new evidence that was able to take advantage of the more detailed price data from the ERS QFAHPD, suggested that subsidies that would lower the price of dark green vegetables may be expected to reduce children’s weight outcomes, whereas subsidies inclusive of starchy vegetables may have unintended effects of increasing weight.53 Further research linking the more detailed ERS QFAHPD price data versus the more limited but commonly used C2ER/ACCRA to additional individual-level data sets including those for adult and adolescent populations and analyses by income levels is needed to provide important evidence relevant to the effective design of subsidies aimed at improving weight outcomes.

This review documented the recent evidence relevant to current fiscal policies being considered as potential pricing instruments to incentivize individuals to consume more healthy diets and improve weight outcomes. Given the consistent evidence that lower prices for fruits and vegetables were associated with lower weight outcomes among SNAP participants and low-income populations, it is important to continue to pilot test the delivery of subsidies such as is currently being done through the Healthy Incentives Pilot program and to test their associations with consumption and if possible with weight outcomes using longitudinal study designs. It is also important that future research assesses the extent to which subsidies for more healthy food products impact on total caloric intake as some recent research based on an experimental study design suggests such subsidies may increase total energy intake.74 Experimental studies were not assessed in this review due to the fact that such designs often require participants to spend their entire budget, have limited choices, and generally may lack external validity.75

Particularly relevant to the SSB tax debate, this present study was the first to our knowledge to review the price sensitivity of SSB demand specifically with comparisons to aggregated and disaggregated measures and to broader soft drink estimates. In particular, a substantial body of new evidence emerged on the price elasticity of SSBs – 12 estimates were provided in seven new studies published since a previous review22 of studies through to 2007. However, despite the increasing evidence base, more study estimates are needed to improve the precision and applicability of the expected effect. Future studies on demand should avoid grouping sugar sweetened and non-sugar sweetened drinks in the same category. Additional research is needed to assess price elasticity of demand for SSBs. In particular, sensitivity analysis within demand systems on single versus multiple categorization of SSBs would make a strong contribution to the literature and would help us understand the nature of substitution between and across SSBs and non-SSBs. Additional research also is needed on linking soda and SSB prices to weight outcomes given the limited variability in current soda taxes and the fact that they apply equally to diet soda. Most of the price elasticity estimates were derived from household-level or time series data which did not provide differential impacts by age groups. Future studies that use individual-level data would provide further evidence on the extent of differential effects across various populations. Indeed, evidence for other risky behaviors shows that young people are more responsive than adults to changes in the prices of tobacco products and alcoholic beverages.76;77

The growing evidence base assessed herein indicates that changes in the relative prices of less healthy and healthier foods and beverages can significantly change consumption patterns and, may have significant impacts on weight outcomes at the population level, particularly among populations most at risk for obesity and its consequences. Raising the prices of less healthy options by taxing them has the added benefit of generating considerable revenues that can be used to support costly programs and other interventions aimed at improving diets, increasing activity, and reducing obesity, including subsidies for healthier foods and beverages.

Acknowledgments

This study was commissioned by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (RWJF) through its Healthy Eating Research Program. We also gratefully acknowledge research support from grant number R01 DK089096 from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK). The manuscripts contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official view of the RWJF, NIDDK or the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

The authors have no conflict of interests for this manuscript.

Contributor Information

Lisa M. Powell, Health Policy and Administration, School of Public Health and Institute for Health Research and Policy, University of Illinois at Chicago.

Jamie F. Chriqui, Institute for Health Research and Policy, University of Illinois at Chicago.

Tamkeen Khan, Department of Economics, University of Illinois at Chicago.

Roy Wada, Institute for Health Research and Policy, University of Illinois at Chicago.

Frank J. Chaloupka, Institute for Health Research and Policy and Department of Economics, University of Illinois at Chicago.

Reference List

- 1.Flegal KM, Carroll MD, Kit BK, Ogden CL. Prevalence of obesity and trends in the distribution of body mass index among US adults, 1999–2010. JAMA. 2012;307:491–497. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Kit BK, Flegal KM. Prevalence of obesity and trends in body mass index among US children and adolescents, 1999–2010. JAMA. 2012;307:483–490. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cawley J, Meyerhoefer C. The medical care costs of obesity: An instrumental variables approach. Journal of Health Economics. 2012;31:219–230. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2011.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kuchler F, Stewart H. Price Trends Are Similar for Fruits, Vegetables, and Snack Foods. USDA ERS Economic Research Report # 55. 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang YC, Bleich SN, Gortmaker SL. Increasing Caloric Contribution From Sugar-Sweetened Beverages and 100% Fruit Juices Among US Children and Adolescents, 1988–2004. Pediatrics. 2008;121:e1604–e1614. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-2834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Malik VS, Schulze MB, Hu FB. Intake of sugar-sweetened beverages and weight gain: A systematic review. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006;84:274–288. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/84.1.274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vartanian LR, Schwartz MB, Brownell KD. Effects of Soft Drink Consumption on Nutrition and Health: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. American Journal of Public Health. 2007;97:667–675. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.083782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reedy J, Krebs-Smith SM. Dietary Sources of Energy, Solid Fats, and Added Sugars among Children and Adolescents in the United States. J Am Diet Assoc. 2010;110:1477–1484. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2010.07.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.U.S. Department of Agriculture and U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2010. 7. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office; 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Welsh JA, Sharma AJ, Grellinger L, Vos MB. Consumption of added sugars is decreasing in the United States. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2011;94:726–734. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.111.018366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bleich SN, Wang YC, Wang Y, Gortmaker SL. Increasing consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages among US adults: 1988–1994 to 1999–2004. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009;89:372–381. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2008.26883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guthrie JF, Lin BH, Frazao E. Role of food prepared away from home in the American diet, 1977–78 versus 1994–96: Changes and consequences. Journal of Nutrition Education & Behavior. 2002;34:140–150. doi: 10.1016/s1499-4046(06)60083-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Poti JM, Popkin BM. Trends in Energy Intake among US Children by Eating Location and Food Source, 1977–2006. J Am Diet Assoc. 2011;111:1156–1164. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2011.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guenther PM, Dodd KW, Reedy J, Krebs-Smith SM. Most Americans eat much less than recommended amounts of fruits and vegetables. J Am Diet Assoc. 2006;106:1371–1379. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2006.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Blanck HM, Gillespie C, Kimmons JE, Seymour JD, Serdula MK. Trends in fruit and vegetable consumption among U.S. men and women, 1994–2005. Prev Chronic Dis. 2008;5:A35. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Casagrande SS, Wang Y, Anderson C, Gary TL. Have Americans increased their fruit and vegetable intake? The trends between 1988 and 2002. Am J Prev Med. 2007;32:257–263. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2006.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brownell KD, Frieden TR. Ounces of prevention--the public policy case for taxes on sugared beverages. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:1805–1808. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp0902392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Powell LM, Chaloupka FJ. Food Prices and Obesity: Evidence and Policy Implications for Taxes and Subsidies. The Milbank Quarterly. 2009;87:229–257. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2009.00554.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chriqui JF, Eidson SS, Bates H, Kowalczyk S, Chaloupka FJ. State sales tax rates for soft drinks and snacks sold through grocery stores and vending machines, 2007. J Public Health Policy. 2008;29:226–249. doi: 10.1057/jphp.2008.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Powell LM, Chriqui JF. Food Taxes and Subsidies: Evidence and Policies for Obesity Prevention. In: Cawley J, editor. The Handbook of the Social Science of Obesity. Oxford, U.K: Oxford University Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Oliveira V, Frazao E. Economic Research Report No 73. 2009. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service; 2009. The WIC Program Background, Trends, and Economic Issues. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Andreyeva T, Long M, Brownell KD. The impact of food prices on consumption: a systematic review of research on price elasticity of demand for food. American Journal of Public Health. 2010;100:216–222. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.151415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thow AM, Jan S, Leeder S, Swinburn B. The effect of fiscal policy on diet, obesity and chronic disease: a systematic review. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 2010;88:609–614. doi: 10.2471/BLT.09.070987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chaloupka FJ. ImpacTeen Research Paper Number 38. Chicago: ImpacTeen, Health Policy Center, Institute for Health Research and Policy, University of Illinois at Chicago; 2010. Tobacco Control Lessons Learned: The Impact of State and Local Policy. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey Data. Hyattsville, MD: U.S., Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2011. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lin BH, Smith TA, Lee JY, Hall KD. Measuring weight outcomes for obesity intervention strategies: The case of a sugar-sweetened beverage tax. Economics & Human Biology. 2011;9:329–341. doi: 10.1016/j.ehb.2011.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Finkelstein EA, Zhen C, Nonnemaker J, Todd JE. Impact of targeted beverage taxes on higher- and lower-income households. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170:2028–2034. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Smith TA, Lin BH, Lee JY. Economic Research Report Number 100. Economic Research Report Number 100. United States Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service; 2010. Taxing caloric sweetened beverages: Potential effects on beverage consumption, calorie intake, and obesity. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Duffey KJ, Gordon-Larsen P, Shikany JM, Guilkey D, Jacobs DR, Jr, Popkin BM. Food Price and Diet and Health Outcomes: 20 Years of the CARDIA Study. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170:420–426. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2009.545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dharmasena S, Capps O. Intended and unintended consequences of a proposed national tax on sugar-sweetened beverages to combat the U.S. obesity problem. Health economics. 2011 doi: 10.1002/hec.1738. n/a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhen C, Wohlgenant MK, Karns S, Kaufman P. Habit Formation and Demand for Sugar-Sweetened Beverages. American Journal of Agricultural Economics. 2011;93:175–193. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brown MG. Impact of income on price and income responses in the differential demand System. Journal of agricultural and applied economics. 2008;40:593–608. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zheng Y, Kaiser HM. Advertising and U.S. Nonalcoholic Beverage Demand. Agricultural and Resource Economics Review. 2008;37:147–159. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zheng Y, Kaiser HM. Estimating Asymmetric Advertising Response: An Application to U.S. Nonalcoholic Beverage Demand. Journal of agricultural and applied economics. 2008;40:837–849. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zheng Y, Kinnucan H, Kaiser H. Measuring and testing advertising-induced rotation in the demand curve. Applied Economics. 2010;42:1601–1614. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Khan T, Powell LM, Wada R. Fast Food Consumption and Food Prices: Evidence from Panel Data on 5th and 8th grade Children. Journal of Obesity. 2012 doi: 10.1155/2012/857697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Beydoun MA, Powell LM, Wang Y. The association of fast food, fruit and vegetable prices with dietary intakes among US adults: Is there modification by family income? Social Science & Medicine. 2008;66:2218–2229. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.01.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Beydoun MA, Powell LM, Chen X, Wang Y. Food prices are associated with dietary quality, fast food consumption, and body mass index among U.S. children and adolescents. J Nutr. 2011;141:304–311. doi: 10.3945/jn.110.132613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sturm R, Datar A. Regional price differences and food consumption frequency among elementary school children. Public Health. 2011;125:136–141. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2010.11.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gordon-Larsen P, Guilkey DK, Popkin BM. An economic analysis of community-level fast food prices and individual-level fast food intake: A longitudinal study. Health & Place. 2011;17:1235–1241. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2011.07.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Powell LM, Auld CM, Chaloupka FJ, O’Malley PM, Johnston LD. Access to fast food and food prices: Relationship with fruit and vegetable consumption and overweight among adolescents. Advances in Health Economics and Health Services Research. 2007;17:23–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lin BH, Yen ST, Dong D, Smallwood DM. Economic Incentives for Dietary Improvement Among Food Stamp Recipients. Contemporary Economic Policy. 2010;28:524–536. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dong D, Lin BH. Economic Research Report No (ERR-70) United States Department of Agriculture; 2009. Fruit and Vegetable Consumption by Low-Income Americans: Would a Price Reduction Make a Difference? pp. 1–23. Economic Research Service, Report Number 70. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Powell LM, Zhao Z, Wang Y. Food prices and fruit and vegetable consumption among young American adults. Health & Place. 2009;15:1064–1070. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2009.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wilde P, Llobrera J, Valpiani N. Household Food Expenditures and Obesity Risk. Curr Obes Rep. 2012;1:123–133. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Oliver TM, Dushy C, Mike R. Taxing unhealthy food and drinks to improve health. BMJ. 2012:344. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e2931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fletcher JM, Frisvold D, Tefft N. Can Soft Drink Taxes Reduce Population Weight? Contemporary Economic Policy. 2010;28:23–35. doi: 10.1111/j.1465-7287.2009.00182.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Han E, Powell LM. Effect of food prices on the prevalence of obesity among young adults. Public Health. 2011;125:129–135. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2010.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Powell LM, Chriqui J, Chaloupka FJ. Associations between State-level Soda Taxes and Adolescent Body Mass Index. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2009;45:S57–S63. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2009.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fletcher JM, Frisvold DE, Tefft N. The Effects of Soft Drink Taxes on Child and Adolescent Consumption and Weight Outcomes. Journal of Public Economics. 2010;94:967–974. [Google Scholar]