Abstract

Researchers have long studied the causes and prevention strategies of poor household water quality and early childhood diarrhea using intervention-control trials. Although the results of such trails can lead to useful information, they do not capture the complexity of this natural/engineered/social system. We report on the development of an agent-based model (ABM) to study such a system in Limpopo, South Africa. The study is based on four years of field data collection to accurately capture essential elements of the communities and their water contamination chain. An extensive analysis of those elements explored behaviors including water collection and treatment frequency as well as biofilm buildup in water storage containers, source water quality, and water container types. Results indicate that interventions must be optimally implemented in order to see significant reductions in early childhood diarrhea (ECD). Household boiling frequency, source water quality, water container type and the biofilm layer contribution were deemed to have significant impacts on ECD. Furthermore, concurrently implemented highly effective interventions were shown to reduce diarrhea rates to very low levels even when other, less important practices were sub-optimal. This technique can be used by a variety of stakeholders when designing interventions to reduce ECD incidences in similar settings.

Introduction

Poor access to adequate water and sanitation infrastructure is an important contributor in over 2 million deaths and 82 million disability-adjust life years (DALYs) that occur throughout the world each year (1). This disease burden has a number of negative effects including child growth stunting which can result from episodes of early-childhood diarrhea (ECD) (2).

Previous researchers have attempted to pinpoint the causes and prevention strategies for such preventable diseases using meta-analyses of conventional intervention-control trials (3–5). However, these studies looked at the effectiveness of each intervention in isolation, a technique that fails to acknowledge the complexities of water and sanitation in such settings. The large heterogeneity seen in these meta-analyses is a further indicator of the inability of single-intervention studies to elucidate the problem. It could also partially be due to difficulties in using self-reported ECD as an indicator of poor water quality (6) or heterogeneity in intervention effectiveness.

The myriad of pathogen sources within a typical developing-world community and the potential for biological regrowth (7) leads one to consider the fact that poor quality water is related to multiple technological, environmental and behavioral factors (8). It is this sort of thinking that has led some to suggest that a systems approach to enteric pathogen transmission would contextualize transmission and inform prevention and control efforts (9). Along these lines, one study found that single-pathway intervention strategies are not effective at preventing diarrhea and that successful interventions must interrupt all significant pathways (10). However, this study was based on a hypothetical disease transmission scenario using adjusted parameters. A second study used the quantitative microbial risk assessment technique although their study was limited to household water treatment devices (11).

One promising approach is to use an agent-based model (ABM). ABMs are object-oriented, spatial models that are currently used in diverse fields to study complex systems. Complex systems do not have any central, coordinating mechanism so that system-level behaviors cannot be predicted based on knowledge of the individual components. These systems can exhibit emergent behavior which can lead to valuable information that would have been difficult to predict a priori.

ABMs typically consist of agents who operate under certain behavior rules in a constructed environment (12). The technique is increasingly being used by public health experts who have studied the H1N1 influenza (13) and insecticide-treated mosquito nets for the prevention of malaria (14). ABMs allow researchers to investigate the essential components of a system in silico negating the need for costly intervention-control trials.

Therefore, the purpose of this research is to develop a robust, quantitative understanding of the complex water chain whose contamination leads to ECD. This model focuses on the transmission of coliform bacteria, but could be generalized to other pathogens. This will be done using an ABM informed by four years of data from adjacent communities in Limpopo, South Africa that will be used to learn more about the causes and prevention strategies of poor household water quality and ECD in such settings. The results of this study can be used by future researchers to design the most effective interventions in similar communities worldwide.

Methods

Community Setting

This ABM is based on four years of data from the adjacent communities of Tshapasha and Tshibvumo in Limpopo, South Africa. Limpopo is the second poorest and most rural province in South Africa. Diarrhea is the second leading cause of death amongst children under four years of age (15). In addition, diarrhea rates are 1.7 times higher than the national average and have increased 170% between 2003 and 2008 in Vhembe District (16).

Residents of Tshapasha and Tshibvumo get water from one of three different systems (7). The first source, referred to herein as “surface water” (SW), is a stream bisecting the communities. Community piped (CP) is a community water system that was improved through a joint effort between the University of Virginia and the University of Venda (17). In this system a series of pipes brings river water from above the community. This water is then sent through a slow-sand filter system, a chlorination tank and into a piped water system for distribution to households. However, the slow sand filter system is currently inoperable and community members report that the chlorination tank is infrequently chlorinated. Municipal tap (MT) is a municipal water system operated by Mutale municipality which is considered to have good water quality (18), but is highly unreliable.

Modeling Environment

The ABM was written in Netlogo, a graphical multi-agent programming language useful for modeling complex systems (19, 20). The model was adapted from an earlier version (21). It includes two types of agents: households and children. The 410 households are laid out across the two communities using measured GPS coordinates. Children are born to individual households in the community at a randomized average rate of 21.9 per year, consistent with a community census performed in 2009.

Each model ‘tick’ corresponds to a ‘day’ of life in the communities and simulation runs are typically 30 years in length. This period allows the simulation to reach equilibrium while providing enough statistical significance for the results to be interpretable. This period corresponds to approximately 657 children being born and 4.49×106 household-days.

Variables ‘owned’ by each one of the two agent types are summarized in Supporting Information Table S1. Variables such as primary water source and sex are constant for each respective household and child, while variables such as child ECD status can change daily. Global variables used by all agents are shown in Supporting Information Table S2. Further details about how variable values were measured are given in subsequent sections and the supporting information.

Water Chain

The water chain model developed for this study was based on an 8-month investigation of community water quality and practices which was published previously (7). That study focused on 50 households within the communities and found significant monthly inter and intra-household water quality variability along with consistently higher levels of total coliform bacteria present at the household level compared to source water. It also found significant total coliform bacteria levels associated with the sidewalls of storage containers, on water transfer devices used to scoop water (typically a ladle or cup) and associated with participants’ hands. The study also found significant bacteria regrowth in stored water containers indicating an important contributor to household bacteria levels. ‘Narrow neck’ containers were generally cleaner.

Unpublished results taken concurrently and described in detail in the Supporting Information section surveyed participants about water source preferences and reliability, the number of days participants kept water, the maximum number of days a household could keep their water as well as the frequency of water boiling, water container cleaning, and hand-washing. To minimize the effects of report bias, the same information was asked during caregiver interviews and daily report calendars multiple times using multiple different questions. These results are then stochastically varied between the minimum and maximum reported values in the model to more realistically represent actual behavior for each respective household surveyed. Households not surveyed are then given the same characteristics as the closest household that was surveyed.

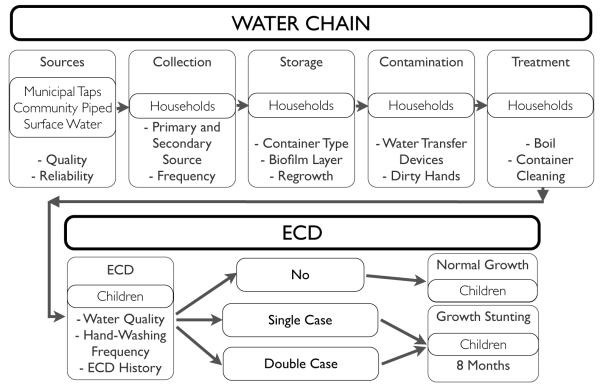

During each model ‘day’ the water quality parameter of the ith household is represented by WQi (cfu/100mL) and can change according to the water chain shown in Figure 1. For this study, WQi is represented by total coliform bacteria.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of ABM routines. Source water can be of three different types, municipal tap (MT), community piped (CP) and surface water (SW) with related quality and reliability. Households collect water from either a primary or secondary source with a given rate. During storage the water can be contaminated by a biofilm layer or biological regrowth which depends on container type and source water. Water can be further contaminated by water transfer devices or dirty hands for ‘wide neck’ containers. Finally, it can be treated by boiling or water quality can be improved through container cleaning. This water chain determines WQi - the water quality of the ithhousehold - which in turn makes children more or less likely to get ECD. A child’s propensity to get ECD can be decreased through hand-washing frequency or increased through previous ECD cases. Children then grow according to their ECD status. They experience stunted growth during ‘single’ cases of ECD and are further stunted if they get two or more cases of ECD within 8 months.

Initially, if a household’s primary water source is operational and if a household needs water, it can collect it from the three main water sources, MT, CP or SW which have associated reliability and quality. If a household wants to collect water, but their primary water source is inoperable, they wait for some number of days. If a household cannot wait any longer (i.e. they have exceeded their ‘Maximum days can keep water’) they then revert to a secondary water source, which is frequently of inferior quality.

Once a household has collected water, it is put into their water storage container where it may be contaminated by the biofilm layer on the inside of the container. The contamination amount is based on field measurements previously reported (7) and detailed in the Supporting Information. Likewise field measurements also found significant coliform bacteria associated with households’ water transfer devices (typically cups or ladles) and hands. If a household uses a ‘wide neck’ storage container their water can be contaminated by water transfer devices and hands as detailed in the Supporting Information. During the storage period WQi can increase or decrease daily as a result of bacteria regrowth or death which is a function of storage period, water source type and water container type (7).

Households can treat their water by boiling at a frequency determined as being stochastically between the minimum and maximum values reported during field surveys. Boiling efficiency is estimated through a literature review to be 98.57% effective in similar settings (22–24). It is modeled using a normalized distribution with SD = 0.111. Finally, households can choose to clean their water storage containers at a frequency determined by the field surveys. This reduces coliform levels by a stochastically varying amount determined by field measurements of between 20 and 27%.

During each model day, WQi is calculated for each household as outlined above. The propensity of a child living in a given household to get ECD is based on WQi and a stochastic variable calculated daily ranging between the low and high values of the best available dose-response literature for E. coli (25, 26) and summarized in Supporting Information Table S3. A child can decrease their ECD risk by up to 43% if they practice optimal hand-washing (27) which has been estimated to require people to wash their hands 32 times per day (28). This is modeled by taking a stochastically varying number of daily hand-washing events between the minimum and maximum reported values for each household. A child’s propensity to get ECD is then reduced by dividing this number by 32 and multiplying by 0.43.

Children typically do not consume water during their first months of life. This is reflected in the fact that those children cannot get ECD from the consumption of water during that period and is based on field data about child water consumption in the communities. Children in the communities receive a rotavirus vaccine which has been shown to reduce total ECD cases by 44.1% in South Africa (29). This reduced risk is used in the model. Finally, a child’s future risk can be increased by a factor of 1.93 if ECD occurs during their first year of life (30).

Child Growth

Child growth stunting is a sensitive measure of ECD incidences (2). One convenient measure of child growth are HAZ scores which, for the purposes of this work, is the number of standard deviations above or below World Health Organization (WHO) normal values (31). This age and gender neutral metric is positive for children that are growing faster than normal, and negative for children whose growth is below normal.

A project entitled The Interactions of Malnutrition & Enteric Infections: Consequences for Child Health and Development (Mal-ED) has been tracking ECD incidences and child height of children under two years of age for more than two years and has accrued 3,847 child height measurements of 313 children in the immediate vicinity of the communities (32). That data indicate that children are born at approximately 0.84 standard deviations below WHO median values. The ABM children are therefore born according to a normalized height distribution whose mean value is –0.84 with standard deviations of 1.90 and 1.86 cm for boys and girls respectively. These standard deviations represent world average values at birth (31). After birth, children follow a piecewise linear fit of standard WHO median growth curves until they get ECD (33).

If a child gets ECD, their growth is stunted by an amount calculated from Mal-ED results. These data indicate that during the 4-month period before and after an ECD incidence, children’s HAZ scores are reduced by an average amount of 0.237 (t(59) = 4.68, p < 0.001) compared to healthy children. Furthermore, children with two or more cases of ECD within that eight-month period have their HAZ reduced by 0.424 on average more than healthy children (t(70) = 4.91, p < 0.001). These two scenarios will henceforth be called ‘single’ and ‘double’ ECD cases respectively. This HAZ data is incorporated into the model as outlined in the Supporting Information section.

Model results can be summarized using three main metrics. These are the median daily household water quality (WQi), mean ECD cases per child over the first two years of life and mean HAZ at age two (HAZ2).

Statistical Methods

A chi-squared test (34) was performed on daily WQi values to compare the modeled data with field household water quality measurements. The data was divided into the following ranges: 0 – 10, 10 – 100, 100 – 1000 and 1000+ cfu/100 ml for the test.

Behavior Space Analysis

Netlogo allows users to easily vary parameters to better understand the sensitivity of a model to those parameters and to understand how given agent behaviors might affect model outcomes. Parameters and ranges were chosen based on field measurements and are outlined in Supporting Information Table S4. For each parameter variation, the model was run for 100 different 30-year runs. This gave reasonable statistical significance while being computationally manageable. Four of the most interesting analyses are summarized below, while eleven other analyses are included in the supporting information.

In order to further elucidate the model’s controlling parameters a large scale behavior space analysis was conducted in which the eleven model parameters deemed most likely to generate meaningful changes in HAZ2 were simultaneously varied. These parameters were varied across ranges that generated the most interesting responses during the single parameter analysis. These parameter combinations resulted in 46,656 30-year runs with each parameter combination being run only once. Results were analyzed by comparing the varied parameter values for the top 1% of simulation runs in terms of HAZ2.

Results

Model Validation

The model represents all of the essential elements of the water chain system identified in the field work. Calculated WQi values also reasonably reproduce the 8-months of field measurements of household water quality as can be seen with the cumulative distribution function in Supporting Information Figure S1. The chi-squared test indicates that the fit is statistically significant (χ2 = 5.8116, p = 0.121).

The average ECD cases per child for the two year period were 8.49 cases, which is consistent with a 2010 survey of African children which found a rate of 8.45 cases during the first two years of life (35).

The plot of monthly mean HAZ scores in Supporting Information Figure S2 indicates a reasonable fitting of the data. In that plot, the ABM children’s monthly average HAZ scores are plotted along with the Mal-ED data set. One sample t-tests indicate that the model reasonably represents the community growth curves for 22 of the 25 months (See Supporting Information Table S5).

Single Parameter Behavior Space Analysis

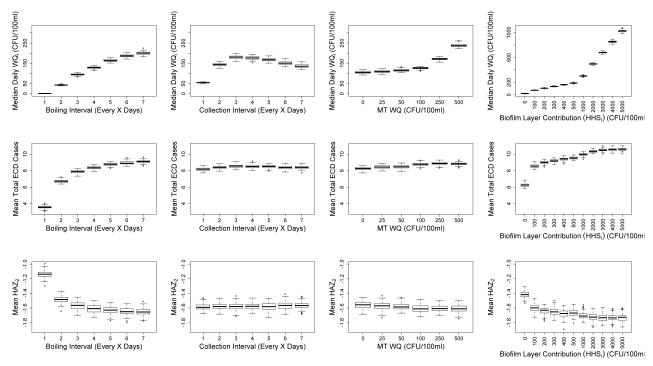

Results from the single parameter behavior space analysis are summarized in Figure 2. That figure summarizes the results of four different behavior space analyses in terms of median daily water quality, mean number of ECD cases per child over the first two years of life and mean HAZ2. Boiling and collection intervals are in terms of those behaviors occuring every X days, where X varies from 1 to 7. The third experiment is municipal tap water quality (MT WQ) in which the municipal tap water quality was varied over the non-linear range given in Supporting Information Table S4. Finally, in the last experiment the container biofilm layer (HHSi) was varied over the non-linear range shown in Supporting Information Table S4.

Figure 2.

Single parameter behavior space analysis of model summarizing the results from four different behavior space runs with median daily WQi, mean total ECD cases, and mean HAZ2. The boiling and collection interval experiments are in terms of those behaviors occurring every X days. Municipal tap (MT) water quality is the water quality of the MT water system and is varied according to typical ranges found in field data. Biofilm layer contribution (HHSi) is the amount of coliform bacteria associated with the water storage container sidewalls and is also varied across ranges typical of the field data. Results indicate that only optimal interventions (e.g. daily boiling and HHSi = 0 cfu/100 mL) produced large reductions in growth stunting as reported by HAZ2 values. Other variables such as daily water collection and low coliform levels in the MT water system improved water quality, but failed to decrease ECD rates or child stunting.

Median WQi varied significantly across boiling frequencies (F = 18,965, p < 0.001), collection frequencies (F = 166, p < 0.001), MT water quality (F = 31658, p < 0.001) and biofilm layer contri-bution (HHSi) (F = 166,629, p < 0.001). Optimal behaviors and conditions resulted in reasonable median WQi in all four cases presented. However, daily water boiling and having an HHSi of 0 cfu/100 mL resulted in the best overall median WQi.

Increased boiling frequency was associated with improved WQi. For the water collection experiment, WQi was better when it was collected daily and deteriorated markedly in simulation runs when households collected their water every 2 or more days. Interestingly, water quality improved slightly for houses who kept their water for more than 3 days. These two trends are due to biological regrowth and eventual death. MT water quality had a significant impact on household WQi, although even perfect source water quality resulted in less than perfect household quality. Biofilm layer contributions (HHSi) proved to be the most significant factor in poor WQi, especially when HHSi was very high.

Mean ECD cases also varied statistically across boiling frequencies (F = 1955.2, p < 0.001), collection frequencies (F = 17.061, p < 0.001), MT water quality (F = 293.96, p < 0.001) and biofilm layer contribution (HHSi) (F = 989.82, p < 0.001). However, large ECD reductions were seen in only a few cases. ECD cases were much lower during simulation runs when all households boiled their water every day compared to those who did so less frequently. Furthermore, during runs in which all households had 0 cfu/100mL of HHSi there were fewer ECD cases. Despite WQi improvements seen, collection frequency and MT water quality had little impact on mean ECD cases.

HAZ2 varied across boiling frequencies (F = 1079.2, p < 0.001), collection frequencies (F = 12.194, p = 0.001), MT water quality (F = 46.214, p < 0.001) and biofilm layer contribution (HHSi) (F = 472.35, p < 0.001). However, most of these differences were modest and were similar to ECD results. Significant improvements in HAZ2 scores are only seen when interventions such as boiling are done every day. Likewise, having 0 cfu/100mL of HHSi resulted in improved HAZ2 levels. Collection frequency and MT water quality were not strongly correlated to HAZ2 changes.

Behavior space analyses for all other parameters are summarized in the supporting information section. In brief those results indicate a moderate relationship between median daily WQi and the percentage of houses that have ‘narrow neck’ containers, water transfer devices coliform levels, coliform regrowth, CP water quality, the increased use of the CP and MT water systems and slow sand filter (SSF) status. These relationships translated into meaningful differences in ECD incidences and hence HAZ2 for households with ‘narrow neck’ containers, CP water quality and the prevalence of CP and MT water systems. ECD rates as a function of hand-washing frequency also showed a strong correlation to ECD cases and HAZ2. The model was less sensitive to water container cleaning intervals, SW water quality and CP and MT operational rates.

Multiple Parameter Behavior Space Analysis

The multiple parameter behavior space analysis provided further insight about which parameters have the most potential to improve HAZ2 scores. Each varied parameter is listed in Table 1. Table 1 also has the values over which each parameter was varied. Alongside each of those values is the percent of runs with that value that were in the top 1% of all 46,656 runs in terms of HAZ2. The top 1% corresponded to runs with HAZ2 values of -0.663 or greater. This can happen when there is an average of less than one ECD case per child during those simulations. These HAZ2 scores are notable because they are significantly lower than any single intervention from Figure 2. These results can be interpreted by comparing the percents for each parameter value. Large differences in the percentages corresponds to important parameters. Likewise, small differences in the percentages means that those parameters are less important. For instance, parameters such as biofilm layer contribution where 100.0% of the runs in the top 1% had 0 cfu/100mL indicate that that HAZ2 scores are highly sensitive to it. Conversely, CP reliability is less important since 49.7% of runs in the top 1% of all runs had the CP operational every day, while 50.3% of the runs had CP only operational every week.

Table 1.

Multiple parameter behavior space analysis of ABM. Parameter and values tested along with the percent of runs for each value that were in the top 1% of all 46,656 runs in terms of HAZ2. Large differences in these percents indicate important parameters, while small differences mean that the parameter is less important. Data indicate that container type, biofilm layer contribution, boiling interval, MT water quality and CP water quality are the most important controlling system parameters.

| Parameter | Parameter Values | Percent of Runs in Top 1% |

|---|---|---|

| MT Use | 25% 50% 75% |

13.9 20.8 65.3 |

| ‘Narrow Neck’ Container Use | 0% 50% 100% |

0.6 0 99.4 |

| Biofilm Layer Contribution (cfu/100 ml) | 0 250 500 |

100.0 0.0 0.0 |

| Water Transfer Device Contribution (cfu/100 ml) | 0 500 4000 |

33.0 32.5 34.5 |

| Slow Sand Filter | ON OFF |

54.6 45.4 |

| CP Reliability (Days per Week Operational) | 1 7 |

49.7 50.3 |

| Collection interval (Every X Days) | 1 2 3 7 |

7.7 12.8 22.9 56.5 |

| Cleaning interval (Every X Days) | 1 7 |

54.0 46.0 |

| CP Water Quality (cfu/100 ml) | 0 100 500 |

69.4 19.9 10.7 |

| MT Water Quality (cfu/100 ml) | 0 100 |

91.0 9.0 |

| Boiling interval (Every X Days) | 1 2 7 |

69.4 18.6 12.0 |

Based on these results it is clear that HAZ2 scores are sensitive to container type, biofilm layer contribution, boiling frequency, MT water quality and CP water quality. Conversely, the water transfer device contribution, SSF status, CP reliability, collection frequency and cleaning frequency were not as important. Most importantly, these results suggest that optimal ECD re-ductions might be realized even when less important parameters are sub-optimal and that highly effective intervention combinations can reduce ECD to very low levels.

Discussion

This study has described the development of a novel agent-based model informed by four years community data and its ability to dissect the complex natural/engineered/social system that leads to poor household water quality and ECD. Household boiling frequency, source water quality, water container type and biofilm layers are all potential intervention areas that might lead to large reductions in ECD. However, the model indicates that these interventions must be optimally implemented before significant improvements can be attained. Furthermore the model suggests that, intervention combinations, when optimally implemented can effect large reductions in ECD even when other areas remain unimproved.

The results indicate that although single interventions can significantly reduce risk, intervention combinations can reduce it much further. This is especially notable since the model indicates that only the most important contributors need to be minimized to realize this goal. This work is supported by the work of Eisenberg et al. (10), who found that all significant transmission pathways must be stopped to effect maximum benefits. The results herein also show how much the combined effects of multiple interventions might be able to reduce ECD rates and what interventions in particular are most important. In addition, this model has its foundation in field data from two well-studied communities. The model does differ somewhat from previous results that looked at the effectiveness of multiple interventions. For instance, the Fewtrell meta-analysis (4) found multiple interventions to be less effective than some other individual interventions including handwashing and household water treatment. However, as the authors state, it is likely that those multiple intervention trials looked at sub-optimal implementation.

The behavior space analyses summarized in Figure 2 provide an interesting insight into the system complexities. In the case of boiling frequency, median water quality increases at a near linear rate, while ECD cases and HAZ2 follow a highly non-linear trend. This is due to the non-linear dose-response curve. This diagram also points to the difficulty in implementing water boiling campaigns especially in regions where household water treatment is rarely and inconsistently practiced (36) and in any community where behavior change is challenging (37). Similar results were also found by Enger et al. (11) who emphasized the importance of compliance for household water treatment interventions.

The collection frequency simulations point to the potential importance of biological regrowth and other contamination sources in such communities (7). This analysis found that although household water quality was much better for houses that collected water everyday, this improvement did not directly translate into a large decrease in ECD cases or HAZ2 scores. This might be why researchers have found mixed results on diarrhea rates when studying water system reliability. In South Africa Majuru et al. found that the health gains of new water systems were largely lost if they were unreliable (38), while Lee and Schwab’s meta-analysis suggested that risk assessment of diarrheal diseases due to system failure is tenuous (39).

Improving MT water quality led to significant improvements in household water quality in the model. However, this improvement again did not lead directly to large ECD reductions or improvements in HAZ2. MT improvements would have been more effective at improving ECD rates if all residents used this system. The fact that improved source water quality does not necessarily lead to large reductions in ECD rates is well-known in the literature (4, 5). The results presented here may explain why improving source quality does not always drastically reduce ECD rates.

The biofilm layer contribution experiments showed the largest variation in household water quality in the model. These variations led to significant variations in ECD rates and HAZ2 scores. This is one indicator as to why point-of-use ceramic filters have proven to be effective at reducing ECD rates (40) worldwide and why safe water systems that prevent biological layer formation have improved water quality in South Africa (41). The container cleaning experiment results are given in the supporting information section. They do not predict large improvements because of the measured ineffectiveness of container cleaning in the communities. It is unfortunate that container cleaning is not more effective at removing biological layers in these communities and is an obvious area for improvement. More consistent chlorination should also reduce biological layer development.

The multiple parameter analysis added further insight into the complex system by elucidating the most important controlling parameters. It is these parameters that might, if properly addressed, lead to the largest ECD reductions in the communities. As was seen in the case with the single parameter experiments, biofilm layers and boiling frequency were both important parameters. In addition, the use of ‘narrow neck’ containers provided important protection against ECD. These containers usurp the need for water transfer devices, have generally less biological regrowth (7) and are less likely to be contaminated by fingers. This finding is supported by previous researchers who have likewise seen some improvement with narrow neck containers in Pakistan (42) or who have found that covered water storage containers in Zimbabwe are generally cleaner (43).

The importance of MT and CP source water quality is somewhat surprising given that most researchers have found that source water protection does not always lead to substantial reductions in ECD rates (4). However, other researchers in Mozambique have shown an association between source and household water quality (44).

The modeled results presented herein are likely reasonable representations of results obtainable in the field. First of all, the water chain model described in Figure 1 represents all elements of the system as measured in field work and reproduces WQi values measured in household water. This water chain model was loosely based on the F-diagram (45), but goes far beyond it in terms of the system complexity and is fully quantified using field data (7).

Secondly, given the water quality data, and the dose-response relations used, the average ECD rate of 8.49 cases during the first two years is consistent with previous studies (35). Furthermore, the average yearly ECD rates for 0-5, 6-11 and 12-24 month old children are 2.1, 4.4 and 5.1 which is statistically equivalent to the Walker study for those same age ranges in Africa (35). The relative risk associated with daily boiling from this study, 0.42, is statistically identical to the relative risk of 0.65 (0.39 - 0.94) seen by others for household water treatment (4). The results are closer if one assumes more irregular boiling in the ABM. Furthermore, the relative risk associated with the increased use of MT was 0.85 in this study which compares favorably to the 0.94 (0.65 - 1.35) seen previously for a community water connection (4).

Lastly, the stunting seen in the communities is consistent with that seen in a similar Brazilian study (30) which found stunting to decrease by 0.31 for ECD cases lasting less than 7 days and 0.59 for ECD cases lasting 7 to 13 days. The ABM child growth curve shown in Supporting Information Figure S2 does an accurate job of recreating the Mal-ED data. In both cases children start off stunted, but remain at approximately the same level during the first 6 to 8 months of life. This is likely due to the fact that those children are getting ECD at lower rates because many are not consuming water daily. The lower rates for children under 6 months old are seen in previous meta-analyses of African children (35).

Although the model is based on data obtained from the two South African communities the risk factors and proposed interventions are generalizable to other similar settings in the developing world. First of all, the water sources used are typical of those found in other parts of Africa (46) and other developing regions. Secondly, the community’s source water quality is likewise typical. The recontamination of water between source and household is well documented in the literature for many parts of the world (47) and the sources of recontamination are similar to those found in previous studies in Honduras (48) and Tanzania (49). Finally, the water and sanitation behaviors and practices of the residents have likewise been observed in a number of previous studies (36, 46).

Although the model is well validated, the use of the E. coli dose-response relations summarized in Supporting Information Table S3 to predict the dose-response relationships for total coliform bacteria is sub-optimal. However, total coliform bacteria is a indicator of bacterial regrowth (50) and inadequate water treatment (51) two of the critical components of the model. Furthermore, the presence of total coliform bacteria can indicate that other harmful bacteria may be present (51). The use of the discretized risk categories in Supporting Information Table S3 based on total coliform concentration is a reasonable approach because it is likely that water with high total coliform concentrations is somewhat more likely to have high levels of pathogenic bacteria. Furthermore, the sensitivity analysis given in the supporting information indicates that linear variations of the dose-response relation does not affect the overall shapes of the HAZ2 output data and hence has little impact on the qualitative conclusions reached in this analysis (Supporting Information Figure S14). Finally, the water chain framework developed for this model can be easily adapted for other pathogens by future researchers.

It is also true that nutritional intake and acquisition of protective immunity against pathogens that cause ECD (i.e. through breast-feeding) are important and are not fully reflected in this model. One area for further study would be to incorporate the currently evolving understanding of the relationships between malnutrition and immunity (52).

Although three susceptibility parameters (hand-washing reductions, rotavirus vaccination status and the doubling of ECD susceptibility for previously infected children) are based on other reviews, the susceptibility to get ECD is based on household drinking water quality. Since these three parameters are applied uniformly to all children irrespective of their water quality, changing these parameter values only leads to uniform linear changes in HAZ scores and have no impact on the main conclusions of this study. This is seen in the sensitivity of the model to hand-washing frequency which is documented in the Supporting Information - the other parameters would perform similarly.

The ABM can be used to guide policies and community interventions. For instance, it allows one to identify the ‘tipping points’ at which certain levels of compliance or intervention effectiveness might vastly reduce ECD rates.

Next, the ABM can be used to quickly and easily test multiple hypotheses about the effectiveness of different interventions or intervention combinations. For instance, it can be used to model ECD reductions from implementing a household ceramic water filter intervention using field data about declining microbiological effectiveness, realistic filter usage and breakage rates. A willingness-to-pay for improved water quality and water and sanitation knowledge diffusion could also be implemented. Using the model in this manner can save time and money while providing the most effective interventions for communities.

Next, the geo-spatial aspect of the model enables researchers to identify key areas of the community that might require additional attention allowing more targeted interventions for the most vulnerable. Finally, the ABM is already proving useful as it guides university researchers as they plan upcoming interventions.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgement

This research was supported by the Fogarty International Center at the National Institutes of Health (Grant numbers 1R25TW007518-01 and 1R24TW008798-01) as well as the EPA STAR Program. We would like to thank a number of our collaborators without whose help this project would not have been possible. The Mal-ED project and their helpful researchers provided us with a great deal of data used to substantiate the model. Jeffrey Demarest developed the first version of the ABM software with Sheree Pagsuyoin also being a integral part of that work. Univen students Elly Mboneni and Kwathiso Netshifhefhe served the project through their excellent community work. UVA Wise student Rachel Hensley was integral in her efforts at field data collection. Finally, we would like to thank all of the other members of the Water and Health in Limpopo Project whose framework made this work possible.

Footnotes

Supporting Information Supporting figures and tables, information about how data was collected, detailed model structure and additional sensitivity and behavior space analyses are available as supporting information. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- (1).Prüss A, Kay D, Fewtrell L, Bartram J. Estimating the burden of disease from water, sanitation, and hygiene at a global level. Environmental Health Perspectives. 2002;110:537–542. doi: 10.1289/ehp.110-1240845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Checkley W, Buckley G, Gilman R, Assis A, Guerrant R, Morris S, Mølbak K, Valentiner-Branth P, Lanata C, Black R. Multi-country analysis of the effects of diarrhoea on childhood stunting. International Journal of Epidemiology. 2008;37:816. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyn099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Esrey S, Feachem R, Hughes J. Interventions for the control of diarrhoeal diseases among young children: improving water supplies and excreta disposal facilities. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 1985;63:757. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Fewtrell L, Kaufmann R, Kay D, Enanoria W, Haller L, Colford J. Water. sanitation, and hygiene interventions to reduce diarrhoea in less developed countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet Infectious Diseases. 2005;5:42–52. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(04)01253-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Clasen T, Schmidt W, Rabie T, Roberts I, Cairncross S. Interventions to improve water quality for preventing diarrhoea: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2007;334:782. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39118.489931.BE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Schmidt W, Arnold B, Boisson S, Genser B, Luby S, Barreto M, Clasen T, Cairncross S. Epidemiological methods in diarrhoea studies an update. International Journal of Epidemiology. 2011;40:1678–1692. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyr152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Mellor J, Smith J, Dillingham R. Pathogen Sources and Mechanisms for Regrowth in Household Drinking Water in Limpopo, South Africa. 61st ASTMH Meeting; Atlanta, GA. November 11-15; Deerfield, IL: American Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- (8).Ezzati M, Utzinger J, Cairncross S, Cohen A, Singer B. Environmental risks in the de-veloping world: exposure indicators for evaluating interventions, programmes, and policies. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. 2005;59:15–22. doi: 10.1136/jech.2003.019471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Eisenberg J, Trostle J, Sorensen R, Shields K. Toward a Systems Approach to Enteric Pathogen Transmission: From Individual Independence to Community Interdependence. Annual Review of Public Health. 2012;33:239. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031811-124530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Eisenberg J, Scott J, Porco T. Integrating disease control strategies: balancing water sanitation and hygiene interventions to reduce diarrheal disease burden. American Journal of Public Health. 2007;97:846. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.086207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Enger K, Nelson K, Clasen T, Rose J, Eisenberg J. Linking Quantitative Microbial Risk Assessment and Epidemiological Data: Informing Safe Drinking Water Trials in Developing Countries. Environmental Science & Technology. 2012;46:5160–5167. doi: 10.1021/es204381e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).An G. Dynamic knowledge representation using agent based modeling: ontology instantiation and verification of conceptual models. Methods in Molecular Biology: Systems Biology. 2009;500 doi: 10.1007/978-1-59745-525-1_15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Shi P, Keskinocak P, Swann J, Lee B. Modelling seasonality and viral mutation to predict the course of an influenza pandemic. Epidemiology and Infection. 2010;138:1472–1481. doi: 10.1017/S0950268810000300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Gu W, Novak R. Predicting the impact of insecticide-treated bed nets on malaria transmission: the devil is in the detail. Malaria Journal. 2009;8 doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-8-256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Bradshaw D, Nannan N, Laubsher R, Groenewald P, Joubert J, Nojilana B, et al. Mortality Estimates for Limpopo Province 2000. South Africa National Burden of Disease Study. 2000;10 [Google Scholar]

- (16).Sello E. District and Province Profiles. South Africa National Burden of Disease Study. 2010 Available at: http://www.healthlink.org.za/uploads/files/dhb0708_secB_lp.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- (17).Harshfield E, Jemec A, Makhado O, Ramarumo E. Water Purification in South Africa: Reflections on Curriculum Development Tools and Best Practices for Implementing Student-Led Sustainable Development Projects in Rural Communities. International Journal for Service Learning in Engineering. 2009;4:1–14. [Google Scholar]

- (18).DWA Blue Drop Report. 2012.

- (19).Tisue S, Wilensky U. International Conference on Complex Systems. 2004:16–21. [Google Scholar]

- (20).Railsback S, Grimm V. Agent-based and individual-based modeling: A practical introduction. Princeton University Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- (21).Demarest J. M.Sc. thesis. The University of Virginia; Charlottesville, VA: 2011. An Agent-Based Model of Water and Health. [Google Scholar]

- (22).Clasen T, Thao D, Boisson S, Shipin O. Microbiological effectiveness and cost of boiling to disinfect drinking water in rural Vietnam. Environmental Science & Technology. 2008;42:4255–4260. doi: 10.1021/es7024802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Rosa G, Miller L, Clasen T. Microbiological effectiveness of disinfecting water by boiling in rural Guatemala. The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 2010;82:473–477. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2010.09-0320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Clasen T, McLaughlin C, Nayaar N, Boisson S, Gupta R, Desai D, Shah N. Micro-biological effectiveness and cost of disinfecting water by boiling in semi-urban India. The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 2008;79:407–413. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Brown J, Proum S, Sobsey M. Escherichia coli in household drinking water and diarrheal disease risk: evidence from Cambodia. Water Science and Technology. 2008;58:757–763. doi: 10.2166/wst.2008.439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Jensen P, Jayasinghe G, Hoek W, Cairncross S, Dalsgaard A. Is there an association between bacteriological drinking water quality and childhood diarrhoea in developing countries? Tropical Medicine & International Health. 2004;9:1210–1215. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2004.01329.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Curtis V, Cairncross S. Effect of washing hands with soap on diarrhoea risk in the community: a systematic review. The Lancet Infectious Diseases. 2003;3:275–281. doi: 10.1016/s1473-3099(03)00606-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Graeff J, Elder J, Booth E. Communication for health and behaviour change: a developing country perspective. Jossey Bass; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- (29).Madhi S, Cunliffe N, Steele D, Witte D, Kirsten M, Louw C, Ngwira B, Victor J, Gillard P, Cheuvart B. Effect of human rotavirus vaccine on severe diarrhea in African infants. New England Journal of Medicine. 2010;362:289–298. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0904797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Moore S, Lima N, Soares A, Oriá R, Pinkerton R, Barrett L, Guerrant R, Lima A. Prolonged episodes of acute diarrhea reduce growth and increase risk of persistent diarrhea in children. Gastroenterology. 2010;139:1156–1164. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.05.076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).De Onis M. WHO Child Growth Standards: length/height-for-age, weight-for-age, weight- for-length, weight-for-height and body mass index-for-age. WHO; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- (32).Lang D. The Mal-Ed Project: Deciphering The Relationships Among Normal Gut Flora, Enteric Infection And Malnutrition And Their Association With Immune Response To Vaccines. 2011 [Google Scholar]

- (33).WHO The WHO Growth Charts. 2012 Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/growthcharts/who_charts.htm. [Google Scholar]

- (34).Kottegoda T, Rosso R. Applied Statistics for Civil and Environmental Engineers. Blackwell Publishing; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- (35).Walker C, Perin J, Aryee M, Boschi-Pinto C, Black R. Diarrhea incidence in low-and middle-income countries in 1990 and 2010: a systematic review. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:220. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Rosa G, Clasen T. Estimating the scope of household water treatment in low-and medium-income countries. The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 2010;82:289–300. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2010.09-0382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Mosler H. A systematic approach to behavior change interventions for the water and sanitation sector in developing countries: a conceptual model, a review, and a guideline. International Journal of Environmental Health Research. 2012;22:431–449. doi: 10.1080/09603123.2011.650156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (38).Majuru B, Michael Mokoena M, Jagals P, Hunter P. Health impact of small-community water supply reliability. International Journal of Hygiene and Environmental Health. 2011;214:162–166. doi: 10.1016/j.ijheh.2010.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).Lee E, Schwab K. Deficiencies in drinking water distribution systems in developing countries. Journal of Water and Health. 2005;3:109–127. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (40).Hunter P. Household water treatment in developing countries: comparing different intervention types using meta-regression. Environmental Science & Technology. 2009;43:8991–8997. doi: 10.1021/es9028217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (41).Potgieter N, Becker P, Ehlers M. Evaluation of the CDC safe water-storage intervention to improve the microbiological quality of point-of-use drinking water in rural communities in South Africa. Water SA. 2009;35:505–516. [Google Scholar]

- (42).Jensen P, Ensink J, Jayasinghe G, Van Der Hoek W, Cairncross S, Dalsgaard A. Domestic transmission routes of pathogens: the problem of in-house contamination of drinking water during storage in developing countries. Tropical Medicine & International Health. 2002;7:604–609. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3156.2002.00901.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (43).Mazengia E, Chidavaenzi M, Bradley M, Jere M, Nhandara C, Chigunduru D, Murahwa E. Effective and culturally acceptable water storage in Zimbabwe: maintaining the quality of water abstracted from upgraded family wells. Journal of Environmental Health. 2002;64:15–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (44).Cronin A, Breslin N, Gibson J, Pedley S. Monitoring source and domestic water quality in parallel with sanitary risk identification in Northern Mozambique to prioritise protection interventions. Journal of Water and Health. 2006;4:333–346. doi: 10.2166/wh.2006.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (45).Wagner E, Lanoix J. Excreta disposal for rural areas and small communities. World Health Organization; Geneva: 1958. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (46).Thompson J. Drawers of water II: 30 years of change in domestic water use & environmental health in east Africa. Summary. Vol. 3. Iied; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- (47).Wright J, Gundry S, Conroy R. Household drinking water in developing countries: a systematic review of microbiological contamination between source and point-of-use. Tropical Medicine & International Health. 2004;9:106–117. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3156.2003.01160.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (48).Trevett A, Carter R, Tyrrel S. Mechanisms leading to post-supply water quality deterioration in rural Honduran communities. International Journal of Hygiene and Environmental Health. 2005;208:153–161. doi: 10.1016/j.ijheh.2005.01.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (49).Pickering A, Davis J, Walters S, Horak H, Keymer D, Mushi D, Strickfaden R, Chynoweth J, Liu J, Blum A. Hands, water, and health: fecal contamination in Tanzanian communities with improved, non-networked water supplies. Environmental Science & Technology. 2010;44:3267–3272. doi: 10.1021/es903524m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (50).LeChevallier M. Coliform Regrowth in drinking water. A review. American Water Works Association. 1990;82:74–86. [Google Scholar]

- (51).EPA Drinking Water, National Primary Drinking Water Regulations, Total Coliforms (Including Fecal Coliforms and E. Coli) Final Rule. Federal Register. 1989;54 [Google Scholar]

- (52).Korpe P, Petri W. Environmental enteropathy: critical implications of a poorly understood condition. Trends in Molecular Medicine. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2012.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.