Abstract

Parent communication of BRCA1/2 test results to minor-age children is an important, yet understudied, clinical issue that is commonly raised in the management of familial cancer risk. Genetic counseling professionals and others who work with parents undergoing this form of testing often confront questions about the risks/benefits and timing of such disclosures, as well as the psychosocial impact of disclosure and nondisclosure on children’s health and development. This paper briefly reviews literature on the prevalence and outcome of parent-child communication surrounding maternal BRCA1/2 test results. It also describes a formative research process that was used to develop a decision support intervention for mothers participating in genetic counseling and testing for BRCA1/2 mutations to address this issue, and highlights the conceptual underpinnings that guided and informed the intervention’s development. The intervention consists of a print-based decision aid to facilitate parent education and counseling regarding if, when, and potentially how to disclose hereditary cancer risk information to children. We conclude with a summary of the role of social, behavioral, and decision science research to support the efforts of providers of familial cancer care regarding this important decision, and to improve the outcomes of cancer genetic testing for tested parents and their nontested children.

Keywords: parents, children, adolescents, cancer genetic testing, BRCA1/2, decision support, decision aid, family communication

Introduction

Genetic counseling and testing for susceptibility to breast and/or ovarian cancer vis-à-vis BRCA1 and BRCA2 (BRCA1/2) testing is now widely available to women and men with suggestive personal and family histories of these cancers. To date, over 250,000 individuals have undergone predictive testing for hereditary cancer risk, most frequently for BRCA1/2 mutations [1]. Mutations in these genes are associated with lifetime breast cancer risks of up to 75% and ovarian cancer risks up to 51% [2]. Given these risks, it is recommended that, by age 25, mutation carriers undergo heightened surveillance for breast cancer; in addition, options for chemoprevention and risk-reducing mastectomy should be considered [3]. Risk-reducing oophorectomy by age 35–40 is also recommended given the lack of effective screening for ovarian cancer [3].

Because of the substantial medical implications associated with BRCA1/2 mutations, carriers are advised to inform adult relatives of their possible risk status. Consistent with autosomal dominant inheritance, this risk is 50% in first-degree relatives. Indeed, a major reason why some individuals seek testing is to learn whether hereditary risk may be passed on to others in the family, especially children [4–6]. However, the social and behavioral impact of the knowledge of a mother’s BRCA1/2 test result on her at-risk children’s psychosocial and developmental functioning has not been well studied. Among fathers who seek BRCA1/2 testing, even less is known about the effect of disclosure among minor-age children, although men who pursue such information may do so when their children are at or approaching adulthood [4].

Past works indicate that among mothers who undergo BRCA1/2 testing, the rate of disclosure to children is about 50%, and may be associated with the age of the child (older versus younger) and the presence of a more open parent-child communication style [7–9]. In mothers who have had early-onset breast cancer, regardless of whether the family history was consistent with hereditary breast cancer, Miesfeldt and colleagues reported 81% were concerned about their children’s breast cancer risk, and 71% felt childhood was the most appropriate time in life to begin providing education about hereditary cancer [10]. A majority of mothers believed that parents play an important role in providing such education and many also wanted professional guidance in doing so. That desire is understandable in light of work demonstrating that the decision to disclose results may be associated with elevated distress in mothers [8, 9]. However, in children, disclosure does not appear to be associated with negative outcome [11, 12], although daughters of mothers with breast cancer may be prone to significant worry about their health and genetic risk, and may be especially susceptible to distress during the genetic testing process itself [13, 14]. This literature is also small, and therefore may not fully capture the range and type of concern held by parents and their children. Not surprisingly, notification of their mother’s positive BRCA1/2 status may result in heightened interest in genetic testing and proactive adoption of lifestyle changes [11]; this is true despite the fact that testing of minors is uniformly discouraged by medical professionals owing to the lack of medical benefit and concerns about autonomous decision making and children’s psychological well-being in this circumstance [15, 16].

Given the aforementioned issues, there has been increasing attention to the phases of decision making and disclosure of BRCA1/2 test results between parents and children, including how parents navigate issues of if, when, and how to disclose to children, and how to appropriately handle their own and their children’s responses to these discussions [17]. Although it is recommended that discussions about family communication be included in cancer genetic counseling sessions [18, 19], physicians and genetic counselors may have little involvement in assisting parents with decisions regarding communication of test results to minor children specifically [7]. Lack of such discussion by health professionals may be due, in part, to parents not seeking advice--turning to family members instead [7]. Indeed, mothers (especially those with higher decisional conflict about whether or not to discuss their BRCA1/2 result with children) have indicated a strong desire to receive additional resources to assist in this process, including literature, access to prior testing participants who faced the same situation, support groups, and other forms of normative guidance [20].

To fill this gap, we conducted formative research to further inform the development of a decision support intervention--specifically, a decision aid--to assist mothers undergoing BRCA1/2 testing with their choices about whether, when, and how to discuss their cancer genetic test results with their children, and to help them anticipate their and their children’s needs and responses related to this decision. Our decision aid is designed to be shared with mothers after their initial genetic counseling session, but prior to when they receive their test results. The decision aid is currently being evaluated in a randomized controlled trial to determine whether communication and related outcomes among genetic testing participants are improved by providing a decision support intervention in addition to standard pre- and posttest genetic counseling.

The purpose of the current paper is to highlight the conceptual frameworks that informed the development of the intervention. In addition, we provide an overview of the formative research process used to develop its content and other specific aspects of the decision aid. Finally, we conclude with a discussion of directions for future research and evaluation efforts in this area.

Conceptual Frameworks

Medical advances have expanded the range of options from which patients may choose to manage their health care, and this has added to the complexity of medical decision making. Simultaneously, the Internet has made a voluminous amount of health care information available to patients, though the quality of this information is highly variable. In addition, there has been a trend toward an ethos of shared decision making between patients and their health care providers, especially for complex decisions for which established recommendations are nonexistent, not standardized, or evidence-based [21, 22]. Patient decision aids have helped to fill this void, and are rapidly becoming an increasingly popular method of facilitating communication and decision exchanges, particularly when there is a lack of consensus regarding how to proceed [21].

Standardizing the development, content domains, and measures of effectiveness for decision aids is of high importance. Indeed, the International Patient Decision Aids Collaboration published a set of quality criteria for such tools that encompass three domains: 1) the development process (e.g., practitioner and patient input, field testing), 2) content (e.g., information, pros and cons of various options, review of potential outcomes, next steps, value clarification, balancing options, use of patient stories), and 3) establishment of effectiveness (e.g., it helps patients recognize the decision at hand, the available options and features, the values they embody that affect their decision and the decision aid facilitates consistency between patients’ decisions and the features that are most important to them) [23]. These criteria formed a foundation for our work in developing a decision aid-based intervention.

In addition to these general domains, our work incorporated information from a review of non-intervention studies of parents making health-related decisions for children, including those about surgical treatment, immunization, and end of life issues [24]. Common themes in parents’ decision making needs included their desire to have accurate, accessible, and understandable information well in advance of when they needed to make such a decision; the opportunity to learn about other parents’ experiences in similar situations (i.e., normative referencing); and the desire to retain control over the decision making process. Parents also wanted health care providers to initiate discussions about the decision at hand and to acknowledge and discuss the emotional aspects of the decision (e.g., shared decision making, social support).

The development and content of the decision aid described in this paper adheres to many of these quality components and reflects many of the themes noted above [24]. Other frameworks that influenced our formative research included commonly utilized approaches in the health education and counseling field: the PRECEDE portion of the PRECEDE-PROCEED framework [25] and the Ottawa Decision Support Framework (ODSF) [26, 27].

Briefly, PRECEDE refers to Predisposing, Reinforcing, and Enabling Causes in Educational Diagnosis and Evaluation [25]. This health education framework was used herein to foster educational priorities and identify gaps between available and needed resources for mothers surrounding communication of BRCA1/2 test results to their children.

With respect to the format and content of the decision aid, we were guided primarily by key tenets of the ODSF [26, 27]. The ODSF addresses cognitive as well as affective and social components of decision making [28]. Decision aids based on the ODSF often provide information on the pros, cons, and likely outcomes of each decision option; help individuals to weigh these pros and cons according to their own values and preferences; tailor support to factors contributing to decisional conflict, thus clarifying expectations; and provide guidance in the steps of decision making [26, 28]. Decision aids have demonstrated improvements in knowledge, risk comprehension, psychological distress and satisfaction with decision making [21].

With this background, our research then proceeded in two logically-ordered and prescribed phases. In the first phase (Phase I), qualitative interviews were performed with mothers and daughters and feedback from experts was obtained to identify fundamental themes for the content of the intervention. In the second phase (Phase II), a draft version of the interventional decision aid was piloted using a pre-post design with a combination of quantitative and qualitative evaluation tools. The format of the final decision aid is organized around key components of the ODSF.

Methods

Phase I: Development of the Intervention

The study was approved by the host institution’s Institutional Review Board. Informed consent (and assent as applicable) was obtained with all participants. Acritical component in the development of decision support tools is to first assess patient-oriented needs related to information and decision making [25, 28]. The overarching goal was to obtain sufficient information that would be useful in developing educational materials for mothers. At the outset, we remained open to the possibility that one or more intervention formats might be appropriate to support parental decision making in this area.

Participants

During Phase I, a convenience sample of mothers was identified based on their prior participation in our genetic counseling and testing studies, and who had consented to be contacted for ancillary studies on this topic. Mothers were eligible to participate if they had a history of breast cancer (the majority) or were unaffected with breast or ovarian cancer but had a relative with a BRCA1/2 mutation. The final sample contained 17 mothers who received positive, uninformative, or true negative BRCA1/2 results. In addition, they had to be the biological mother of at least 1 daughter between 13–17 years old at the time mothers learned their BRCA1/2 results or who was still in that age range at the time mothers were contacted for study. Because mothers may be more likely to disclose cancer genetic test results to daughters versus sons [8], and because of the more significant medical implications for females, we emphasized the latter in our formative research. However, issues related to disclosure to sons were also addressed and covered in the decision aid so that it would be applicable to children of both genders.

Disclosure of genetic test results to children was not required for participation, although the vast majority of mothers had disclosed to their children by the time of the interview. Following informed consent from mothers, two daughters of mothers with BRCA1/2 positive results who had previously disclosed this information to their children were also enrolled and completed brief qualitative interviews to further inform the intervention development process.

Interviews

Following a standardized method [29], a list of topics to explore with participants was generated by the researchers, who have expertise in cancer genetics, genetic counseling and decision support, and child and family development. The interview guide followed a diachronic reporting format and was organized according to general topic areas and specific probes. Questions focused on the process/rationale for communication decision making, communication process and content, children’s (especially daughters’) reactions to disclosure (if applicable), children’s awareness of their mothers’ cancer history and treatment (if applicable), prior (or desired) information and support resource utilization, and speculation about what information would be helpful for inclusion in an intervention. All interviews were audio recorded and were accompanied by detailed notes taken during the interviews. The interviewers (B.N.P., T.A.D.) are both highly experienced cancer genetic counselors with active research interests in psychosocial and behavioral aspects of BRCA1/2 testing.

Overview of Findings

A formal inductive process was not used to analyze interviews data; rather, our purpose was to identify key themes that could inform the development of the intervention. The themes identified by the mothers included the importance of assessing the readiness and developmental level of each child before deciding whether or not to share information, or proceeding to a discussion about issues related to cancer genetic testing. If the choice to share information about testing is made, mothers emphasized the importance of being reassuring about testing and why the information was pursued; presenting information in a positive light; acknowledging that the process of testing is empowering (e.g., so that steps could be taken to protect the mother’s health); and being as open, honest, and as available as possible to children.

Several mothers also raised the idea of genetic determinism and fatalism (e.g., that biological children, and daughters in particular, may believe that testing positive for a BRCA1/2 mutation is synonymous with actually developing breast cancer, or that dying from cancer is inevitable) and expressed that this concept should be broached in an intervention on this topic and dispelled as untrue. Finally, mothers were interested in specific information about lifestyle and behavioral factors (e.g., diet and nutrition, exercise and physical activity, oral contraceptive use, and cancer screening recommendations for daughters) related to breast cancer onset and severity, as well as a discussion about when it is appropriate to consider predictive genetic testing in children. The brief interview with two daughters revealed that they had vague recollections of their initial conversation about genetic testing with their mothers, with shifting concerns for their mothers’ well-being and their own risk for cancer in the future.

Intervention Outline Development

Based on the interview data, a detailed annotated outline of the content for the intervention was developed by the study team. Sample text, ideas for “tip boxes”, and illustrative quotations were generated.

Advisory Panel

The study retained the services of an outside group of experts to serve on an advisory panel to further guide and inform the development of the intervention. Panel members were leading experts in genetic counseling, medical oncology, child, adolescent and family medicine, psychology and behavioral science, medical decision making, and sociolinguistics. In addition, two patient advocates participated on the advisory panel.

Development of the Decision Aid

Based upon all of the data collected from the interviews as well as the advisory panel’s recommendations, the study team expanded upon the educational content and incorporated formal elements of decision support tools (e.g., sample narratives about mothers undertaking the decision to talk or not talk to their children regarding BRCA1/2 test results). A complete draft of the decision aid was prepared that closely resembled the content of the final version that is currently being evaluated as part of an ongoing randomized controlled trial. This version was sent to advisory panel members for additional commentary and editing, and was used as part of our pilot test.

Phase II: Pilot Test

Mothers who participated in our initial interviews and who expressed an interest in further reviewing the intervention, as well as an additional set of mothers meeting identical eligibility criteria to those described above, were invited to participate in the pilot test phase of the study. This phase involved the completion of a baseline telephone interview prior to reviewing the decision aid, followed by an additional interview approximately one month later. In addition to collecting sociodemographic data, we used a combination of study-specific and standardized measures to assess parent-adolescent communication, family support, knowledge, and decision making. During the follow-up interview, we also administered a study-specific process evaluation tool and several open-ended items assessing the acceptability, understandability, relevance, and sensitivity of the decision aid adapted from prior work [30]. A subset of mothers (n=4) was then chosen to complete a debriefing interview (with B.N.P.) to elicit additional feedback about their reactions to the decision aid. Additionally, they were asked about suggestions for editing, additional resources, responses to the quotations, and usefulness of the worksheets.

Twenty-three mothers completed both assessments; data were summarized quantitatively and examined for trends in change over time. The preliminary data suggested that knowledge was favorably impacted by the intervention, in that mothers tended to score higher after receipt of the decision aid than at baseline. Also, we observed a high rate of confidence and satisfaction in decision making related to family communication about BRCA1/2 testing, which suggested that the decision aid may affect these important domains when implemented prospectively. Subjective feedback from mothers who reviewed the decision aid informed us that although some had concerns about the length of the resource and that some of the content might be repetitive, most thought that the significant strengths of the material included its narrative stories, worksheets, and quotations.

Description of Decision Aid Structure and Content

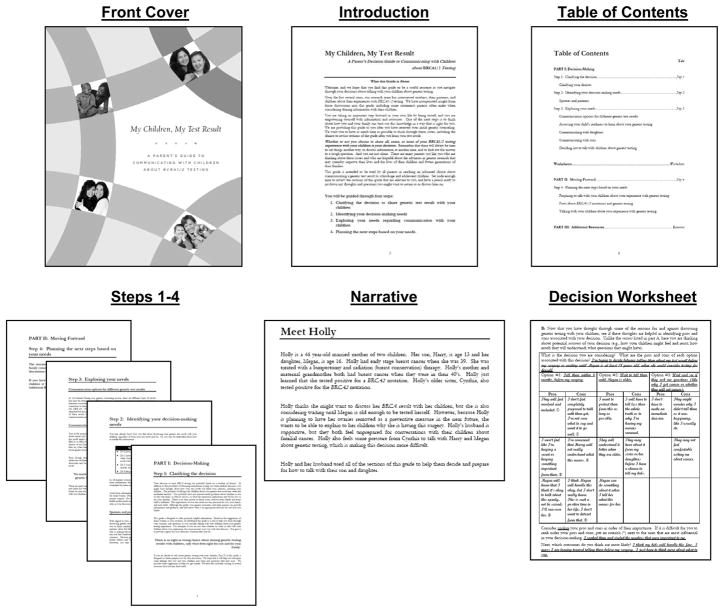

Comments from advisory panel members and participants who took part in the pilot test were then used to finalize the structure and content of the decision aid. Our decision aid is a full-color, spiral-bound 8 1/2″ × 11″ printed guide organized into two main parts, with dividers separating major sections. Figure 1 shows sample pages from the decision aid. Multicultural elements were incorporated throughout via the use of photographs of racially and ethnically diverse models of different ages. Several design elements were also used to enhance the text. For example, major points, themes, and summary statements are set apart from the main text in larger, bolded font (see Table 1). In addition, 20 composite quotations were included throughout the decision aid and they were selected to represent a variety of viewpoints about communication decisions, concerns, and potential outcomes. These quotations were adapted from prior research participants and those who were interviewed as part of this work. Each quotation is attributed to a speaker, identified by pseudonym, age, cancer and/or BRCA1/2 mutation status, and age(s) and gender(s) of children; see Table 2 for examples. Finally, the decision aid contains several text boxes with summary questions and tips (see Table 3).

Fig. 1.

Decision aid: My Children, My Test Result

Table 1.

Sample Summary Statements/Themes

|

Note. Summary statements of key themes were integrated throughout the decision aid to illustrate salient points.

Table 2.

Sample Quotations Integrated into Decision Aid

| I think I would try to get myself to an emotionally healthy point before talking with my children. |

| -Aileen, age 47; mother of a teenage son and daughter |

| I’m usually very open with my children and want them to know everything that’s happening so they feel involved. |

| Mary, age 54; mother of daughters ages 12, 15, and 17 |

| My husband felt helpless. He said that limiting himself to a support role felt unnatural for him. |

| -Robin, age 46; breast cancer survivor and mother of a daughter age 15 |

| It’s a difficult subject for me. I can’t see that sharing this right now would be helpful. Maybe I’ll tell her when she’s older. |

| -Karen, age 51; ovarian cancer survivor and mother of a daughter age 13 |

| Don’t overestimate the importance of a single test result. In some cases, the genetics don’t really matter. |

| -Rochelle, age 17; daughter of a breast cancer survivor with a BRCA1 mutation |

Note, Quotations were integrated throughout the decision aid to illustrate parental views.

Table 3.

Topics for Text Boxes

|

Note. Topics were briefly expanded upon in text boxes throughout the decision aid

Part I of the guide is focused around decision making and consists of three steps, consistent with the ODSF [27]: (1) Clarifying the decision about whether or not to communicate BRCA1/2 test results with adolescent children. This content underscores the personal nature of this decision and helps mothers recognize their feelings about and responses to genetic testing. (2) Identifying decision making needs. In this section, questions are posed such as whether mothers have enough information to make the decision about communicating with their children about genetic testing; whether they understand the factors that go into making this decision and the pros and cons of various decisions; whether they want support, what type and from whom; and the role of partners or spouses in decision making. (3) Exploring needs. This section discusses communication options for different BRCA1/2 testing outcomes, including positive, negative, and uncertain test results. Information is provided to help mothers assess their children’s readiness to learn about genetic testing, including key cognitive, developmental, behavioral, and emotional considerations. Points regarding specific considerations pertaining to communication with both daughters and sons are included. Importantly, a section is included here about factors related to the decision not to talk with children about genetic testing, and parental prerogatives not to do so.

Following Part I of the guide is a tabbed section of worksheets. The worksheets are designed to reinforce key issues discussed in the first three steps of the guide, as outlined above, and to help parents make an informed choice. As mentioned, the format was based on the ODSF [27] and some worksheet self-exercises were adapted with permission from a decision aid for high risk women considering prophylactic mastectomy [31, 32]. The worksheets are first introduced with two hypothetical vignettes, followed by completed worksheet examples for each woman depicted in the vignettes. These vignettes illustrate mothers who have tested positive for a BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation, one of whom needs guidance about talking with her children, the other of whom is unsure about discussing her test results with her children. The worksheet exercises consist of many open-ended questions about the mothers’ decision making process, as well as their information and support needs.

A critical aspect of decision making is related to exploring needs. In this step, an objective exercise was included in which mothers review a list of 18 total potential pros and cons of the decision at hand, check those that apply to them, and add others if they choose. These are organized around the needs, desires, and preferences held by mothers, their spouses/partners, and children (see Table 4). Second, they complete open-ended responses focused on the pros and cons of the outcomes of the decision to which they are leaning (as opposed to the reasons for their decision as described in the checklist). Mothers are then asked to rank their pros and cons in order of importance and to write down which outcomes are most likely. In the third component, mothers are asked to indicate who is involved in their decision making and who provides support and what his or her opinion is about the decision. Finally, this step concludes with an open-ended exercise where mothers are asked to consider some of the problems or challenges they may face in implementing the decision and possible action plans. In the final step of the worksheets, planning the next steps, mothers consider all of their previous responses. Tips are provided if they want more information, are not sure what the most important considerations are in making their decision, feel like they need more support, or are feeling pressure from others. The worksheets end with an exercise in affective forecasting -- a technique to help people imagine their emotional reactions to future events [33]. A journal-style page is provided in which mothers are asked to imagine the process and outcomes of their communication decisions, regardless of whether or when they decide to discuss their genetic testing results. Though the guide can and is intended to be used in its entirety, parents may opt to complete some or all sections that are most relevant to their own decision making.

Table 4.

Potential Reasons Mothers May Cite For and Against Discussing Genetic Testing with Children

Reasons For

|

Reasons Against

|

Note. This list was utilized in the decision worksheet section under “Exploring Your Needs”. Mothers were instructed to check those that apply and to add their own potential reasons for talking about their genetic testing experience with their children

Part II of the guide incorporates the fourth major step related to the ODSF -- planning next steps. In this section, geared toward mothers who are leaning toward or who have made a decision to talk with their children about their genetic testing results, specific tips are included about how to discuss genetic testing (e.g., preparing and initiating discussions, events that may prompt questions from children, anticipating responses from children, etc.), what to discuss with children (e.g., inheritance, cancer risks, management issues, genetic testing in children), and how to help children cope with this information. The last section of the guide, Part III, contains an annotated list of Internet resources and books that may be helpful to parents and children relevant to this topic.

Discussion

The issues parents face regarding whether, when, and how to talk with their children about hereditary cancer risk is a topical one that is receiving increasing attention. The largest support group for individuals with concerns about BRCA1/2 testing, FORCE (Facing Our Risk of Cancer Empowered), recently featured this topic at a national conference in Tampa, Florida, USA which was followed by a “How To” article about this topic in one of their published newsletters [34]. The questions and concerns raised with BRCA1/2 testing are not unique, given that genetic testing for many other adult-onset conditions is currently available, with more tests expected in the future. In light of these considerations, it is important to formally assess the effect of educational and support materials to determine the outcomes of decision making on parent and child well-being and satisfaction.

In this paper we have described an empirical approach to developing a novel interventional decision aid for mothers undergoing BRCA1/2 testing. The process we employed has been used previously [35–38] and has led to the development of validated and effective health education interventions and decision aids for patients [21, 39]. Our decision aid incorporates the features of an effective decision aid [23], and preliminary data and feedback from a convenience sample of mothers suggest that it is likely to be of interest to parents and may be effective in assisting them with their decision making processes. Once data from our randomized controlled trial are obtained, we will know the extent of this effect. If deemed useful and promising, it could be modified for dissemination to a broader audience (e.g., fathers who test positive for a BRCA1/2 alteration) and adapted to parents facing a host of genetic testing circumstances. In addition, further study on developing resources for children and adolescents, both male and female, of various ages, may be important to pursue. Finally, further research into the process and outcomes of parent-child communication about hereditary cancer will shed light on longitudinal questions such as the effect on health promotion behaviors, children’s interest in and utilization of genetic testing, and psychosocial adjustment. Resources such as the one we have developed and are evaluating serve an important role for patients and providers. Although the topic of communication with children may arise in the course of genetic counseling sessions, it is oftentimes not feasible to explore this issue in sufficient depth given the multitude of complex issues that may require more immediate discussion, and providers’ lack of training and expertise in this sensitive area. Parents can utilize decisional resources at a time when it is convenient and helpful to them, which may not always be at the time that they are undergoing the process of genetic testing. They may also return to the materials at a later time when subsequent conversations arise with their children. As parents navigate the process of communicating with their children, it would be desirable for them to have access to a multi-disciplinary team of health care providers, including genetic counselors, nurses, physicians, and psychologists, all of whom can be instrumental in helping families acclimate to this information and make decisions that are consistent with their values and preferences. As this standard of care may not exist in all settings and may not be possible, the use of self-directed decision support interventions appear promising in this respect.

Acknowledgments

Grant support was provided by the National Institutes of Health/National Human Genome Research Institute (R03HG003686 to B.N.P. and R01HG02686 to K.P.T.). The authors would like to thank the mothers and children who participated in this study. We are also grateful to the following individuals for their assistance: Kate Barasz, Karen Brown, Kristi Brown, Mary Daly, Rebecca Fisher, Kristi Graves, Lauren Grella, Michael Green, Heidi Hamilton, Chanita Hughes Halbert, Allyn McConkie-Rosell, Rachel Nusbaum, Jill Trimbath, Heiddis Valdimarsdottir, Erica Wahl, Jeanne Wagner, Leslie Walker, and Lara Wilson. We also thank Annette O’Connor of the Ottawa Health Research Institute and Mary McCullum for permission to use and adapt materials.

References

- 1.Myriad Genetics Inc. Annual shareholder report 2008. 2008 http://files.shareholder.com/downloads/MYGN/515983598x0-x239318/1DDB4C05-419A-400A-A121-545D02F86E6A/2008_Myriad_Annual_Report.pdf. Cited 14 Jan 2009.

- 2.Antoniou A, Pharoah PD, Narod S, et al. Average risks of breast and ovarian cancer associated with BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations detected in case series unselected for family history: a combined analysis of 22 studies. Am J Hum Genet. 2003;72:1117–1130. doi: 10.1086/375033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology. Genetic/familial high-risk assessment: breast and ovarian--v.1.2008. 2008 doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2021.0001. http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/PDF/genetics_screening.pdf. Cited 14 Jan 2009. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Hallowell N, Ardern-Jones A, Eeles R, et al. Men’s decision-making about predictive BRCA1/2 testing: the role of family. J Genet Couns. 2005;14:207–217. doi: 10.1007/s10897-005-0384-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Patenaude AF, Dorval M, DiGianni LS, Schneider KA, Chittenden A, Garber JE. Sharing BRCA1/2 test results with first-degree relatives: factors predicting who women tell. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:700–706. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.01.7541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Peshkin BN, Demarco TA, Garber JE, et al. Brief assessment of parents’ attitudes toward testing minor children for hereditary breast/ovarian cancer genes: development and validation of the Pediatric BRCA1/2 Testing Attitudes Scale (P-TAS) J Pediatr Psychol. 2008 Apr 1;2008 doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsn033. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bradbury AR, Dignam JJ, Ibe CN, et al. How often do BRCA mutation carriers tell their young children of the family’s risk for cancer? A study of parental disclosure of BRCA mutations to minors and young adults. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:3705–3711. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.09.1900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tercyak KP, Hughes C, Main D, et al. Parental communication of BRCA1/2 genetic test results to children. Patient Educ Couns. 2001;42:213–224. doi: 10.1016/s0738-3991(00)00122-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tercyak KP, Peshkin BN, Demarco TA, Brogan BM, Lerman C. Parent-child factors and their effect on communicating BRCA1/2 test results to children. Patient Educ Couns. 2002;47:145–153. doi: 10.1016/s0738-3991(01)00192-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Miesfeldt S, Cohn WF, Jones SM, Ropka ME, Weinstein JC. Breast cancer survivors’ attitudes about communication of breast cancer risk to their children. Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet. 2003;119C:45–50. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.c.10012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bradbury AR, Patrick-Miller L, Pawlowski K, et al. Should genetic testing for BRCA1/2 be permitted for minors? Opinions of BRCA mutation carriers and their adult offspring. Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet. 2008;148C:70–77. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.c.30163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tercyak KP, Peshkin BN, Streisand R, Lerman C. Psychological issues among children of hereditary breast cancer gene (BRCA1/2) testing participants. Psychooncology. 2001;10:336–346. doi: 10.1002/pon.531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cappelli M, Verma S, Korneluk Y, et al. Psychological and genetic counseling implications for adolescent daughters of mothers with breast cancer. Clin Genet. 2005;67:481–491. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2005.00456.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.van Oostrom I, Meijers-Heijboer H, Duivenvoorden HJ, et al. Experience of parental cancer in childhood is a risk factor for psychological distress during genetic cancer susceptibility testing. Ann Oncol. 2006;17:1090–1095. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdl069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.American Society of Human Genetics Boards of Directors, American College of Medical Genetics Board of Directors . Points to consider: ethical, legal, and psychosocial implications of genetic testing in children and adolescents. Am J Hum Genet. 1995;57:1233–1241. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.American Society of Clinical Oncology. American Society of Clinical Oncology policy statement update: genetic testing for cancer susceptibility. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:2397–2406. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.03.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Clarke S, Butler K, Esplen MJ. The phases of disclosing BRCA1/2 genetic information to offspring. Psychooncology. 2008;17:797–803. doi: 10.1002/pon.1344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Peterson SK. The role of the family in genetic testing: theoretical perspectives, current knowledge, and future directions. Health Educ Behav. 2005;32:627–639. doi: 10.1177/1090198105278751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Trepanier A, Ahrens M, McKinnon W, et al. Genetic cancer risk assessment and counseling: recommendations of the National Society of Genetic Counselors. J Genet Couns. 2004;13:83–114. doi: 10.1023/B:JOGC.0000018821.48330.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tercyak KP, Peshkin BN, Demarco TA, et al. Information needs of mothers regarding communicating BRCA1/2 cancer genetic test results to their children. Genet Test. 2007;11:249–255. doi: 10.1089/gte.2006.0534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.O’Connor AM, Stacey D, Entwistle V, et al. Decision aids for people facing health treatment or screening decisions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003:CD001431. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stacey D, Samant R, Bennett C. Decision making in oncology: a review of patient decision aids to support patient participation. CA Cancer J Clin. 2008;58:293–304. doi: 10.3322/CA.2008.0006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Elwyn G, O’Connor A, Stacey D, et al. Developing a quality criteria framework for patient decision aids: online international Delphi consensus process. BMJ. 2006;333:417. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38926.629329.AE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jackson C, Cheater FM, Reid I. A systematic review of decision support needs of parents making child health decisions. Health Expect. 2008;11:232–251. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-7625.2008.00496.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Green WL, Kreuter WM. Health promotion planning: an educational and ecological approach. 3. Mayfield Publishing Company; Mountain View, California: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 26.O’Connor AM, Jacobsen MJ, Stacey D. An evidence-based approach to managing women’s decisional conflict. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2002;31:570–581. doi: 10.1111/j.1552-6909.2002.tb00083.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.O’Connor AM. Ottawa Decision Support Framework to address decisional conflict. 2006 doi: 10.1177/0272989X06290492. http://decisionaid.ohri.ca/docs/develop/ODSF.pdf. Cited 14 Jan 2009. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 28.O’Connor AM, Drake ER, Fiset V, Graham ID, Laupacis A, Tugwell P. The Ottawa patient decision aids. Eff Clin Pract. 1999;2:163–170. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Weiss RS. Learning from strangers: the art and method of qualitative interview studies. Free Press; New York: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Swanson S, Bennett E. Patient & family education materials development kit. 2005. Children’s Hospital & Regional Medical Center; Seattle, Washington: 2005. http://74.125.47.132/search?q=cache:Xgfa2eKL6jYJ:www.cshcn.org/forms/MatDevKit05.pdf+patient+%26+family+education+materials+development+kit+cshcn&hl=en&ct=clnk&cd=1&gl=us. Cited 14 Jan 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 31.McCullum M. Hereditary Cancer Program. BC Cancer Agency; Vancouver, British Columbia: 2002. Prophylactic mastectomy: a decision-making guide for women at high risk for breast cancer. [Google Scholar]

- 32.McCullum M, Bottorff JL, Kelly M, Kieffer SA, Balneaves LG. Time to decide about risk-reducing mastectomy: a case series of BRCA1/2 gene mutation carriers. BMC Womens Health. 2007;7:3. doi: 10.1186/1472-6874-7-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wilson TD, Gilbert DT. Affective forecasting: knowing what to want. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 2005;14:131–134. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Friedman S. Hereditary cancer: how do I tell my children? FORCE Newsletter. 2008 Winter;2008 http://www.facingourrisk.org/TTInc/viewpage.php?url=.%2Fnewsletter%2F2008winter%2Fhereditary_cancer.html&needle=karen+hurley). Cited 14 Jan 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Taylor KL, Turner RO, Davis JL, III, et al. Improving knowledge of the prostate cancer screening dilemma among African American men: an academic-community partnership in Washington, DC. Public Health Rep. 2001;116:590–598. doi: 10.1093/phr/116.6.590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Juan AS, Wakefield CE, Kasparian NA, Kirk J, Tyler J, Tucker K. Development and pilot testing of a decision aid for men considering genetic testing for breast and/or ovarian cancer-related mutations (BRCA1/2) Genet Test. 2008;12:523–532. doi: 10.1089/gte.2008.0035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Metcalfe KA, Poll A, O’Connor A, et al. Development and testing of a decision aid for breast cancer prevention for women with a BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation. Clin Genet. 2007;72:208–217. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2007.00859.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kaufman EM, Peshkin BN, Lawrence WF, et al. Development of an interactive decision aid for female BRCA1/BRCA2 carriers. J Genet Couns. 2003;12:109–129. doi: 10.1023/A:1022698112236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.O’Connor AM, Bennett C, Stacey D, et al. Do patient decision aids meet effectiveness criteria of the international patient decision aid standards collaboration? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Med Decis Making. 2007;27:554–574. doi: 10.1177/0272989X07307319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schaefer CE, DiGeronimo TF. Specific questions and answers and useful things to say. Jossey-Bass Publishers; San Francisco, California: 1999. How to talk to teens about really important things. [Google Scholar]