Abstract

Objective

Evaluate persistence with treatment, healthcare costs, and utilization in stably enrolled Aetna Behavioral Health members receiving extended-release naltrexone (XR-NTX) for alcohol use dependence compared with oral medications and psychosocial therapy only.

Study Design

Historical cohort study

Methods

Aetna beneficiaries with stable enrollment (at least 6 months before and after index treatment) who initiated pharmacotherapy with XR-NTX (n = 211), disulfiram (n = 1,043), oral naltrexone (n = 1,408), acamprosate (n = 2,479), or psychosocial therapy only (n = 6,374) for alcohol use disorders between 1/1/07 and 12/31/08 were extracted and de-identified from Aetna’s nationwide claims and utilization database. Survival analysis compared persistence with XR-NTX versus oral pharmacotherapies. Difference-in-differences analysis compared healthcare costs and utilization among patients receiving XR-NTX versus oral pharmacotherapies and psychosocial therapy only. Multivariate analyses controlled for demographics.

Results

Patients taking acamprosate and disulfiram were more likely to discontinue treatment than patients taking naltrexone, and oral naltrexone patients were more likely to discontinue treatment than XR-NTX patients. Outpatient behavioral health treatment visits increased in all study groups. Non-pharmacy healthcare costs and utilization of inpatient and emergency services decreased in the XR-NTX group relative to other study groups.

Conclusions

XR-NTX patients persisted with treatment longer than patients receiving oral alcohol use disorder medications or psychosocial therapy only, and decreased inpatient and emergency healthcare costs and utilization to a greater extent than other study groups.

INTRODUCTION

The Food and Drug Administration approved three medications for treatment of alcohol dependence disorder in the past 15 years: oral naltrexone (NTX) in 1994; acamprosate in 2004; and extended release naltrexone (XR-NTX) in 2006. A fourth medication, disulfiram, was approved in 1949. Adoption of alcohol pharmacotherapies, however, has remained limited. One analysis estimates that fewer than 9% of Americans with alcohol dependence fill prescriptions.1

Reasons for limited adoption of alcohol use disorder (AUD) medications are numerous, including lack of organizational support, incompatibility with treatment model and philosophy, limited provider exposure to information, provider concerns regarding efficacy and side effects, and reimbursement difficulties.2–4 The two most commonly cited barriers to adoption of oral NTX in a 2001 survey of addiction physicians were poor adherence and medication cost.4

Poor adherence is a recognized problem among alcohol dependence pharmacotherapies. Side effects, difficulty “feeling” the effect of medication, and lack of understanding of the need for consistent dosing contribute to discontinuation.5 Acamprosate requires thrice-daily dosing and disulfiram produces unpleasant deterrent effects when alcohol is consumed. Oral NTX has a narrow therapeutic window.6 Approximately 15% to 20% of patients continue to fill prescriptions for oral NTX regularly over 6 months.7–9 Kranzler and colleagues found that persistence (a surrogate for adherence) was associated with lower utilization of expensive inpatient healthcare services.9 Subsequent work reported that patients taking oral NTX decreased healthcare spending relative to control patients with and without AUD diagnoses, even when the cost of treatment was included.10

XR-NTX was developed with improved pharmacokinetic properties and a monthly dosing regimen to address the adherence limitations of oral AUD pharmacotherapies.11 Despite these pharmacokinetic advantages, XR-NTX prescribing remains limited due in part to its high cost, the complexity of delivery (must be administered by a qualified healthcare professional), and lack of information about the medication.1,12 Available data suggest that XR-NTX is associated with fewer heavy drinking days and longer time to first drink than placebo over 12-week13 and 24-week periods.14,15,16 Studies conducted in primary care clinics17 and privately funded substance abuse treatment clinics12 found that 70% to 75% of patients who initiated treatment with XR-NTX returned for a second injection, and adherence was associated with decreased alcohol consumption.17 Patients who received XR-NTX, moreover, incurred lower healthcare costs and decreased utilization in the 6 months following treatment initiation compared with those who took oral pharmacotherapies.18

This study takes a different analytic approach and uses a different patient population from those employed by Mark and colleagues18 to compare treatment adherence and healthcare costs of XR-NTX with oral medications and psychosocial therapy. We hypothesized that (a) treatment adherence would be greater for XR-NTX, given its unique pharmacokinetics, and (b) XR-NTX would be associated with decreased healthcare costs (excluding the cost of the medication itself) and utilization of inpatient and emergency treatment.

METHODS

Study Design

For this historical cohort study, the population of interest included all continuously enrolled Aetna Behavioral Health (Aetna) members who began pharmacologic or psychosocial treatment for AUDs between January 1, 2007 and December 31, 2008. Patient-level data on allowed behavioral, physical, and prescription drug claims are stored in an integrated national database. Aetna uses the database to coordinate management of physical healthcare with services for alcohol, drug and mental health problems among members who receive physical, behavioral health, and pharmacy benefits from Aetna. Concurrent review of claims and utilization data identified patients with AUD diagnoses.

Patients were eligible if they met all inclusion criteria: (1) claims review flagged the patient as treated for an AUD, and (2) a prescription for AUD pharmacotherapy (XR-NTX, oral NTX, acamprosate, disulfiram) was filled or psychosocial therapy was initiated. Treatment initiation (the index date) for the psychosocial therapy only group was the date of the first claim with a full psychiatric evaluation (CPT code 90801) and an AUD diagnosis.

There were 4 exclusion criteria: (1) lack of continuous enrollment for 6 months before and after the index date, (2) single claims over $25,000, (3) prescriptions for AUD pharmacotherapies in the 3 months prior to the index date, or (4) prescriptions for multiple AUD pharmacotherapies during the 6 months following the index date. The exclusion criteria were designed to eliminate loss to follow-up (number 1), remove outliers (number 2), and prevent exposure misclassification (numbers 3 and 4). Patients receiving psychosocial therapy only were excluded if they had taken AUD pharmacotherapy at any time in the past. All pharmacotherapy patients who met selection criteria were included as well as a random sample of psychosocial therapy only patients.

There were 73,292 Aetna beneficiaries with AUD diagnoses between January 1, 2007 and December 31, 2008 and 12,994 (18%) with at least 1 claim for an alcohol dependence medication: 241 XR-NTX; 3779 oral NTX; 6059 acamprosate; and 2915 disulfiram. The random sample of psychosocial therapy only patients included 13,968. After exclusion criteria, the final analytic data set contained 211 XR-NTX, 1408 oral NTX, 2479 acamprosate, 1043 disulfiram, and 6374 psychosocial therapy only patients. The Oregon Health & Sciences Institutional Review Board determined that the study was a secondary analysis of de-identified data and qualified for exemption.

Variables

Primary outcome variables were (1) persistence with medication, (2) healthcare spending, and (3) healthcare utilization. Spending and utilization data were aggregated over 6 months before and after the index date.

Persistence measured the number of consecutive days the patients had alcohol dependence pharmacotherapy in their possession. Patients were considered to be in possession of AUD pharmacotherapy from the date they filled a prescription until the date the prescription should have been exhausted. Non-persistence (discontinuation) was defined as the first time after the index date that patients went more than ten consecutive days without medication in their possession. The ten-day cutoff was determined empirically. Patients who refilled within ten days tended to continue to fill prescriptions regularly, whereas patients who waited ten days or longer to refill tended to discontinue.

Healthcare spending measured total non-pharmacy healthcare costs recorded in the Aetna claims database during the 6 month pre- and post-index periods, including out-of-pocket and health plan expenses. Healthcare utilization encompassed inpatient admissions, days spent in inpatient treatment, outpatient behavioral health visits, and emergency room visits. Outpatient behavioral health visits included psychosocial therapy (psychiatrist and therapist visits) and outpatient visits to hospitals/inpatient facilities (intensive outpatient treatment, partial hospitalization).

Primary predictors were (1) time relative to initiation of AUD treatment, and (2) medication (study) group. There were 5 distinct study groups: XR-NTX; oral NTX; acamprosate; disulfiram; and, psychosocial therapy only. The dichotomous time variable tested 6-months pre-index versus 6-months post-index periods.

Covariates included age, gender, beneficiary status, plan type, region, pre-treatment period mental health and substance abuse diagnoses, and pre-treatment period physical health diagnoses. Age was a 4-level categorical variable (<35, 35–44, 45–54, ≥55). Region was a 6-level categorical variable (West, Southwest, North Central, Southeast, Mid Atlantic, and Northeast).

Comorbidities included physical health, mental health, or substance use disorders diagnosed in the 6-month pre-treatment period. Diagnoses were grouped into mental health and substance abuse (MH/SA) categories by ICD-9 code following Ettner et al.19 The MH/SA groups represented schizophrenia and other non-mood psychosis, bipolar disorder, major depression, anxiety disorders, and drug use disorders. The Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) represented physical health comorbidities.20 Due to low prevalence of physical health comorbidities, the CCI score was collapsed into a 3-level categorical variable (zero, 1 to 2, 3 or more).

Statistical Analysis

Survival analysis compared persistence with XR-NTX versus oral pharmacotherapies. Discontinuation of medication was the “failure event,” and it was defined as allowing 10 days to elapse after a prescription was exhausted without refill. Prescriptions filled after the first episode of discontinuation were not included in the analysis. Patients who remained persistent at 180 days were censored at that time. The primary predictor was study group (XR-NTX, oral NTX, acamprosate, disulfiram). Covariates included all demographic variables and pre-treatment comorbidities indicators. Kaplan-Meier survival curves plotted persistence over the 180 day follow-up period. A Cox proportional hazards model compared the risk of discontinuation for XR-NTX versus oral pharmacotherapies.

Difference-in-differences analysis estimated the impact of XR-NTX versus oral NTX, acamprosate, disulfiram, and psychosocial therapy only on healthcare costs and utilization. We compared XR-NTX and comparison groups on the basis of the change in healthcare costs and utilization that each group experienced in the 6 month period before versus after treatment initiation. Primary predictors were (1) a time dummy variable that had the value 1 in the post-treatment period and 0 in the pre-treatment period, and (2) four study group dummy variables with XR-NTX as the reference group. Interactions between the time and study group dummy variables were the primary estimands of interest and tested the difference (between XR-NTX and comparison groups) in the differences (between pre- and post-treatment).

A 2-part model estimated the difference-in-differences for average spending per patient per half-year.21 Logistic regression determined the probability of any spending and utilization, and generalized linear modeling determined average spending conditional on use. Negative binomial regression modeled utilization outcomes. We used the method of recycled predictions, based on the estimated regression model, to calculate the average effects of the predictor variables on spending/utilization. Bootstrapping (500 replications) generated 95% confidence intervals. Demographic variables were included as covariates in all regression models. Pre-treatment comorbidities were not included in the cost and utilization analyses due to poor overlap between study groups. All analyses were conducted using Stata/IC version 11.0 (StataCorp, College Station, TX).

RESULTS

Table 1 summarizes the characteristics of the 5 study groups. Overall, the sample included 62% men with a mean age of 41 years. Most had a preferred provider organization (PPO) health plan (72%) and no physical (85%) or mental health (79%) comorbidities. Study groups significantly differed with respect to gender, age, geographic region of residence, plan type (HMO vs. PPO), beneficiary status (subscriber vs. dependent), and pre-treatment physical health, mental health, and substance abuse diagnoses. Psychosocial therapy only patients were younger, more likely to be male, and less likely to have physical health, mental health, or drug use disorder comorbidities than patients receiving medication-assisted treatment. XR-NTX and acamprosate groups had the highest prevalence of pre-treatment physical health comorbidities (25%), while the XR-NTX and oral NTX groups had the highest prevalence of mental health (41%) and drug abuse (14%) comorbidities.

Table 1.

Sample characteristics by study group in percent.

| Study Group | Chi- | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Psychosocial | Squared | |||||||

| Variable | XR-NTX | Oral NTX | Acamprosate | Disulfiram | Therapy Only | (d.f.)a | p-valuea | |

| N | 211 | 1,408 | 2,479 | 1,043 | 6,374 | |||

| Gender (% male) | 65.4 | 53.3 | 57.5 | 59.8 | 65.5 | 209 (4) | < 0.001 | |

| Region (%) |

West | 11.4 | 13.7 | 15.2 | 21.3 | 8.3 | 2,100 (24) | < 0.001 |

| Southwest | 22.3 | 12.9 | 14.6 | 10.4 | 5.4 | |||

| North Central |

21.8 | 12.4 | 18.4 | 21.3 | 25.7 | |||

| Southeast | 13.3 | 15.3 | 21.2 | 15.6 | 8.7 | |||

| Mid Atlantic |

12.3 | 14.8 | 9.5 | 15.8 | 19.0 | |||

| Northeast | 18.9 | 30.8 | 21.0 | 15.6 | 32.9 | |||

| Unknown | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | |||

| Beneficiary Status (% subscriber) |

63.0 | 58.2 | 64.6 | 65.3 | 58.9 | 76 (4) | < 0.001 | |

| Plan Type (% PPO) |

100.0 | 66.1 | 65.0 | 68.0 | 76.2 | 468 (4) | < 0.001 | |

| Age Group (%) |

< 35 | 23.2 | 30.3 | 17.1 | 21.6 | 37.0 | 836 (12) | < 0.001 |

| 35 – 44 | 35.1 | 27.3 | 27.2 | 29.9 | 24.0 | |||

| 45 – 54 | 30.8 | 27.8 | 37.2 | 34.1 | 25.7 | |||

| 55 or older | 10.9 | 14.5 | 18.5 | 14.4 | 13.3 | |||

| Mean Age (s.d.) | 42.0 (11.2) | 40.5 (13.3) | 45.1 (10.9) | 43.4 (11.1) | 39.1 (14.4) | |||

| Charlson Score (%) |

0 | 73.5 | 81.6 | 74.6 | 80.4 | 90.2 | 862 (12) | < 0.001 |

| 1 – 2 | 20.8 | 13.8 | 20.0 | 16.1 | 8.9 | |||

| > 2 | 5.7 | 4.6 | 5.4 | 3.5 | 0.9 | |||

| Mean Charlson Score (s.d.) | 0.51 (1.16) | 0.44 (1.62) | 0.49 (1.19) | 0.37 (1.04) | 0.14 (0.53) | |||

| Schizophrenia (%) | 3.8 | 2.1 | 2.3 | 1.3 | 0.4 | 160 (4) | < 0.001 | |

| Bipolar Disorder (%) | 11.4 | 11.4 | 8.2 | 6.9 | 1.9 | 654 (4) | < 0.001 | |

| Major Depression (%) | 24.2 | 23.8 | 23.3 | 17.4 | 4.3 | 1,800 (4) | < 0.001 | |

| Anxiety Disorder (%) | 10.0 | 14.1 | 12.9 | 11.8 | 1.1 | 1,300 (4) | < 0.001 | |

| One or More Mental Health Diagnoses (%) |

40.8 | 40.8 | 37.9 | 30.8 | 7.2 | 1,600 (4) | < 0.001 | |

| Drug Use Disorder Diagnoses (%) |

14.2 | 13.0 | 6.8 | 5.9 | 3.8 | 413 (4) | < 0.001 | |

Chi-squared statistics with degrees of freedom (d.f.) in parentheses test for differences in the distribution of each categorical variable across study groups. The p-value for each chi-squared test is presented in the adjacent column.

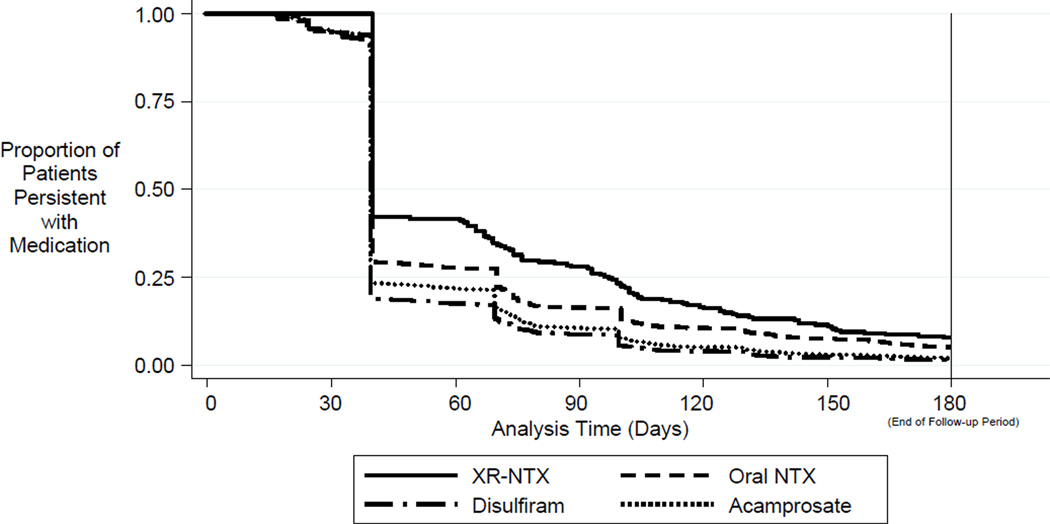

Persistence

Survival analysis assessed duration of alcohol pharmacotherapy. Figure 1 provides Kaplan-Meier survival curves for each study group. Most (89%) patients began treatment with 30-day index prescriptions. Each study group had a steep drop in persistence at 40 days (ten days after expiration of the 30-day index prescriptions). Approximately 40% of XR-NTX patients filled a second prescription, as opposed to 30% of oral NTX patients, 25% of acamprosate patients, and 20% of disulfiram patients. The XR-NTX group had the highest level of persistence (15%) after the full 6 months of follow-up.

Figure 1.

Persistence with Medication over Time a

a Survival curves are adjusted for demographics (gender, age, region, beneficiary status, plan type), pre-treatment physical health comorbidities (Charlson score), pre-treatment drug abuse comorbidities, and pre-treatment mental health comorbidities (schizophrenia, bipolar, major depression, anxiety).

Table 2 presents the results of Cox proportional hazards regression that compared the risk of discontinuation for XR-NTX versus oral pharmacotherapies. The analysis controlled for demographics and all pre-treatment comorbidities. Patients taking oral medications were more likely to discontinue treatment than XR-NTX patients (P <.05). Throughout the 6-month follow-up, patients taking oral NTX, disulfiram, and acamprosate were 27%, 47%, and 49% more likely to discontinue treatment than XR-NTX patients, respectively. Patients taking disulfiram and acamprosate were 16% and 17% more likely to discontinue treatment than oral NTX patients (P <.05).

Table 2.

Persistence Survival Analysis to compare the risk of discontinuing AUD medication among study groups over the 6-month follow-up period.a

| Study Group | Hazard Ratio (95% CI) for Treatment Discontinuation | |

|---|---|---|

| Comparison with XR-NTX | Comparison with Oral NTX | |

| XR-NTX | Reference | 0.79 (0.70 to 0.89)** |

| Oral NTX | 1.27 (1.12 to 1.43)** | Reference |

| Acamprosate | 1.49 (1.32 to 1.67)** | 1.17 (1.11 to 1.23)** |

| Disulfiram | 1.47 (1.30 to 1.66)** | 1.16 (1.09 to 1.23)** |

Cox proportional hazards model compares study groups on the basis of time to treatment discontinuation. The model includes predictor variables representing demographics (gender, age, region, plan type, beneficiary status), pre-treatment physical health comorbidities (Charlson score), pre-treatment mental health comorbidities (schizophrenia, bipolar, major depression, anxiety), and pre-treatment drug use disorders.

Indicates p < 0.01

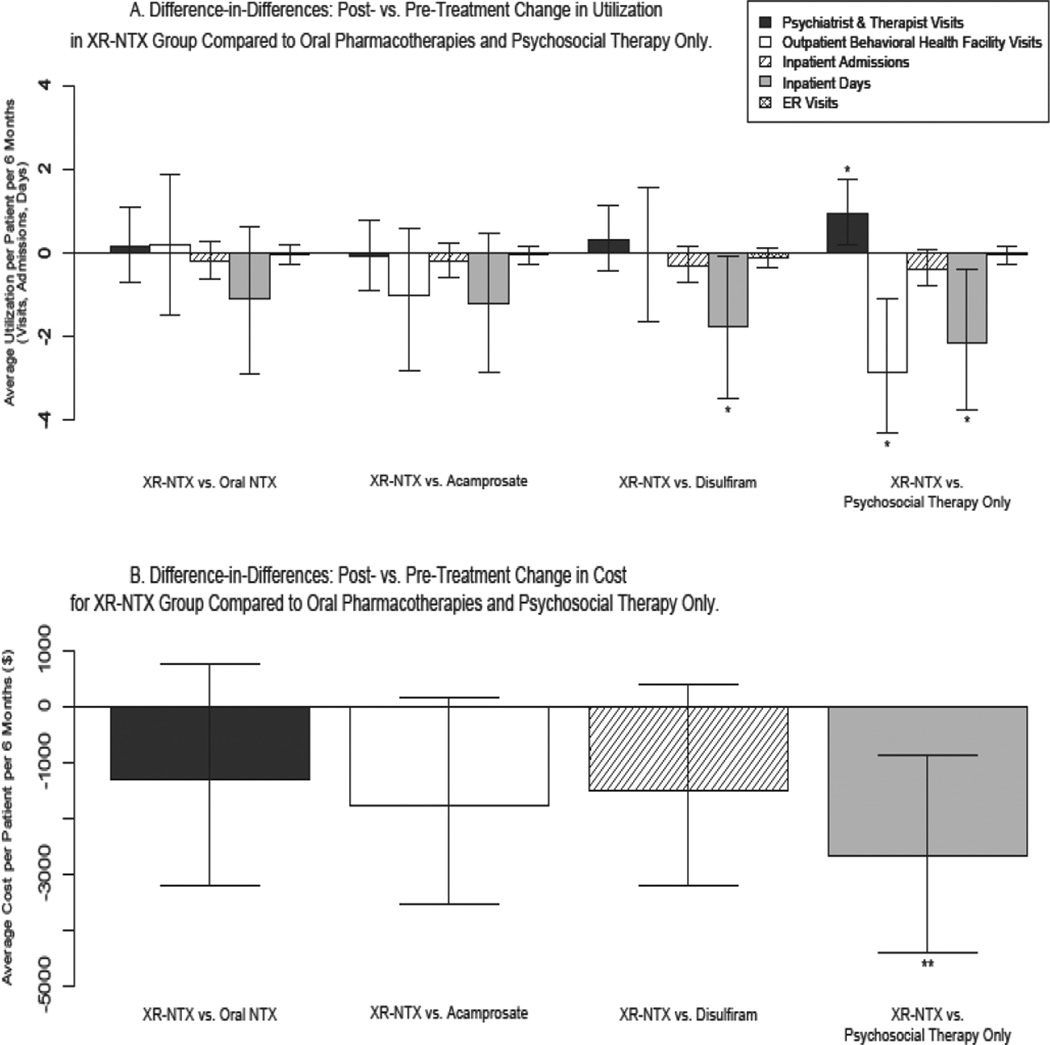

Expenditures and Utilization

Figures 2A and 2B display the difference-in-differences estimates comparing the post- vs. pre-treatment differences in average costs and utilization between XR-NTX and comparison groups. An electronic appendix includes mean expenditure and utilization per patient per 6 months in the pre- and post-treatment periods, pre/post differences, and comparisons of the pre/post differences between the XR-NTX and comparison groups (the difference-in-differences). All analyses controlled for demographics.

Figure 2.

Utilization and Costs of Health Care Services a,b

a Difference-in-Differences method with two-part model was employed. Logistic (part 1) and linear (part 2) regressions modeled cost and utilization outcomes with predictor variables representing demographics (gender, age, region, beneficiary status, plan type), study group, time relative to index date, and the study group*time interaction.

b Figures 2A and 2B depict the difference-in-differences estimates that compare the effect of XR-NTX on health care costs and utilization to oral pharmacotherapies and psychosocial therapy only. Each bar represents the post- vs. pre-treatment difference in average utilization/costs in the XR-NTX group relative to the specified comparison group. Positive bars indicate that patients receiving XR-NTX increased their average utilization/costs in the 6-month post-treatment period relative to the comparison group. Negative bars indicate a relative decrease in utilization/costs in the XR-NTX group following treatment relative to comparison groups. The magnitude of the bars indicates the amount of relative increase/decrease in units of average utilization/cost per patient per six months. All comparisons are absolute differences (as opposed to ratios).

* p<0.05

** p<0.01

Mean pre-treatment spending and utilization of outpatient psychosocial therapy (psychiatrist and therapist visits), outpatient visits to behavioral health hospitals/inpatient facilities, inpatient services, and emergency services were higher in the XR-NTX group (mean = $7,882) than all comparison groups: oral NTX = $7,388, acamprosate = $6,312, disulfiram = $5,369, psychosocial only = $4,137 (see electronic appendix for detail). Psychosocial therapy only patients had very low utilization of outpatient behavioral health services in the pre-treatment period, and the lowest average pre-treatment spending.

All study groups increased outpatient psychosocial therapy visits in the post-treatment period. On average, there was 1 additional psychosocial therapy visit in the post-treatment period for every 1 to 2 medication-assisted patient(s) or 33 psychosocial therapy only patients. The increases in utilization of outpatient psychosocial therapy did not significantly differ between the XR-NTX and oral pharmacotherapy groups, but the increase in the XR-NTX group was significantly greater (P <.05) than psychosocial therapy only.

Outpatient visits to behavioral health hospitals/inpatient facilities (intensive outpatient treatment, partial hospitalization) increased in the post-treatment period compared with the pre-treatment period for all study groups. There were 1 to 2 additional visits in the post-treatment period for each patient receiving medication-assisted treatment, and nearly 5 additional visits per psychosocial therapy only patient. Increases did not significantly differ between XR-NTX and oral medication groups, but the increase in the XR-NTX group was significantly less (P <.05) than psychosocial therapy only.

Utilization of inpatient hospital and emergency room (ER) services decreased following treatment initiation compared with pre-treatment levels in all study groups, more so for XR-NTX patients than comparison patients. Compared with pre-treatment utilization levels, 1 admission (average length of stay: 5 days) was prevented in the post-treatment period for every 2 XR-NTX patients, 5 oral medication patients, and 13 psychosocial therapy only patients. One ER visit was prevented for every 4 XR-NTX patients, 6 oral NTX, acamprosate, or psychosocial therapy only patients, and 9 disulfiram patients. XR-NTX patients decreased the number of days spent in inpatient treatment to a greater extent than disulfiram and psychosocial therapy only patients (P <.05).

Non-pharmacy healthcare spending decreased significantly in the post-treatment period compared with the pre-treatment period for the XR-NTX and oral medication groups, but increased for the psychosocial therapy only group. Spending in the XR-NTX group decreased nearly $2700 per patient per half-year more than in the psychosocial therapy only group (P <.01).

DISCUSSION

Aetna Behavioral Health provided claims data from their national database to examine persistence with AUD medications and healthcare costs incurred. Study patients were drawn from a “real world” population, meaning that patients received AUD pharmacotherapy based on their regular providers’ clinical judgment. AUD pharmacotherapies were prescribed to older and sicker patients than those receiving psychosocial therapy alone. XR-NTX patients had more comorbid diagnoses, higher pre-treatment spending and utilization of outpatient behavioral health services, inpatient services, and emergency services than any other group.

Patients taking XR-NTX persisted with treatment longer than patients receiving oral pharmacotherapies, controlling for demographics and pre-treatment physical health, mental health, and drug abuse comorbidities. Oral and XR-NTX patients persisted with treatment significantly longer than acamprosate and disulfiram patients, suggesting a naltrexone drug effect. XR-NTX patients persisted significantly longer than oral NTX patients, indicating a naltrexone delivery mode effect as well. However, persistence needs to be interpreted carefully, since no direct information on alcohol-related health outcomes was available.

Although direct health outcomes were not available in this study, cost and utilization outcomes were. XR-NTX patients decreased non-pharmacy healthcare spending and utilization of inpatient and emergency services relative to oral pharmacotherapies and psychosocial therapy only. One potential explanation for the decrease in spending and utilization is that patients were avoiding necessary healthcare. Arguing against avoidance is the observation that utilization of outpatient behavioral health services increased in all groups. Further evidence to suggest that patients were not simply avoiding healthcare in the post-treatment period lies in the statistic that over 90% of each medication group had nonzero healthcare spending in both pre- and post-treatment periods (data not shown). The relatively healthy psychosocial therapy only group had lower proportions of patients with nonzero healthcare spending in the pre-treatment (87%) and post-treatment (74%) periods.

This study demonstrated persistence, utilization, and spending patterns similar to those reported in other analyses. 5,7–10,14,17,18,22 Lower levels of persistence in the current study may reflect a more stringent definition of persistence, differences in the health of the study populations, or unique features of the Aetna Behavioral Health system. Spending outcomes differed from a recent study10 of oral NTX spending and utilization because we did not include pharmacy costs in the analyses, but overall patterns were similar. Notably, our cost and utilization results replicated findings that suggest XR-NTX is associated with decreased healthcare costs and utilization compared with oral medications when treating alcohol dependence.18,22 The consistency of results across different patient populations and different analytic approaches lends robustness to these findings. We have also demonstrated an advantage of XR-NTX over oral medications in terms of persistence with treatment. Prior work has found that persistence with XR-NTX is associated with improved drinking outcomes,17 and nonpersistence with oral NTX has been linked with increased healthcare utilization.9 The persistence benefit with XR-NTX provides a plausible explanation for the observed cost and utilization advantages, but the relationship between persistence, health outcomes, and costs/utilization demands further study.

Study Strengths

There are several strengths in this study’s design and analytic approach. The data come from Aetna’s nationwide claims and utilization database, which provides a geographically diverse sample of patients and accurate cost and utilization information. All patients included in the study were continuously enrolled with Aetna Behavioral Health for at least 6 months before and after treatment initiation, so there is no loss to follow-up. Survival analysis provided temporal data on medication persistence throughout the follow-up period. The difference-in-differences analytic approach minimized the effects of unmeasured confounding factors by controlling for time-independent baseline differences between groups. Available confounders were explicitly accounted for in multivariate regression models.

Study Limitations

In addition to its strengths, the study was subject to several limitations. First, treatment was not randomly allocated and the study was limited in its capacity to control for underlying differences between study groups. Considerable differences in demographics, pre-treatment comorbid diagnoses, and pre-treatment utilization patterns between study groups suggest that unmeasured factors could have influenced treatment allocation and confounded outcome measurements. Important variables that were not available included AUD severity and psychometrics such as motivation to change drinking behavior. High pre-treatment utilization suggests that XR-NTX was prescribed to patients with more severe AUDs. Severity is likely to be a negative confounder that biases the results towards the null, but the overall confounding effects of unmeasured factors and non-random treatment allocation is unknown. At the same time, the number of patients receiving each medication reflected current utilization patterns and the number in each group is relatively large. The large number of patients increases confidence in the stability of the results.

The application of selection criteria to study groups with considerable underlying differences could have introduced selection bias. A lower proportion of patients who received XR-NTX (13%) were excluded than oral medication or psychosocial therapy only patients (54% to 64%). Excluded patients are likely to represent individuals who lost their jobs and lacked continuous enrollment, individuals who were prescribed 2 or more AUD medications, and individuals with single claims over $25,000. These exclusions should preferentially omit individuals with relatively poor outcomes, thereby biasing our results towards the null.

The difference-in-differences method is a repeated measures design that renders the analysis susceptible to regression to the mean. We cannot exclude the possibility that regression to the mean is responsible for the observed spending and utilization patterns over time. The analysis is also susceptible to types I and II statistical errors. However, the consistency of the results across several outcomes increases confidence that the observed differences are not statistical artifacts. It is unlikely that such consistency would be observed if the results were attributable to chance.

Conclusions

Continuously enrolled patients with AUDs who were prescribed XR-NTX persisted with treatment longer and experienced larger decreases in non-pharmacy healthcare spending and utilization than those who received oral medications or psychosocial therapy only. Although this study was not able to account for the cost of medication, XR-NTX demonstrated favorable persistence and utilization patterns among a cohort of patients in clinical practice. Future research on this topic is necessary to clarify the associations between persistence, healthcare spending and utilization, and direct health outcomes. Cost-effectiveness analyses of XR-NTX and oral medications would provide critical information for practicing clinicians and insurance providers.

Supplementary Material

Take-Away Points.

Compared with other medications for alcohol use disorders, extended-release naltrexone is associated with increased days on medication. The utilization and cost of inpatient and emergency care also declined more among patients using extended-release nalterxone.

Acknowledgments

Funding: MPH thesis without external support. Dr. Korthuis’ time was supported by the National Institutes of Health, National Institute on Drug Abuse (K23DA019809).

The study was completed without external funding. An award from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (K23DA019809) supported P. Todd Korthuis. Dennis McCarty provides consultation for Purdue Pharma.

Footnotes

"This is the pre-publication version of a manuscript that has been accepted for publication in The American Journal of Managed Care (AJMC). This version does not include post-acceptance editing and formatting. The editors and publisher of AJMC are not responsible for the content or presentation of the prepublication version of the manuscript or any version that a third party derives from it. Readers who wish to access the definitive published version of this manuscript and any ancillary material related to it (eg, correspondence, corrections, editorials, etc) should go to www.ajmc.com or to the print issue in which the article appears. Those who cite this manuscript should cite the published version, as it is the official version of record."

Author Disclosures

There are no additional potential conflicts of interest.

Authorship Information

The analysis was completed as William Bryson’s MPH thesis with the support of his OHSU thesis advisory committee (Dennis McCarty, Chair, John McConnell, Todd Korthuis). Aetna Behavioral Healthcare provided the data.

REFERENCES

- 1.Mark TL, Kassed CA, Vandivort-Warren R, Levit KR, Kranzler HR. Alcohol and opioid dependence medications: prescription trends, overall and by physician specialty. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2009;99:345–349. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.07.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thomas CP, Wallack SS, Lee S, McCarty D, Swift R. Research to practice: adoption of naltrexone in alcoholism treatment. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2003;24:1–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fuller BE, Rieckmann T, McCarty D, Smith KW, Levine H. Adoption of naltrexone to treat alcohol dependence. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2005;28:273–280. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2005.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mark TL, Kranzler HR, Song X. Understanding US addiction physicians’ low rate of naltrexone prescription. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2003;71:219–228. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(03)00134-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weiss RD. Adherence to pharmacotherapy in patients with alcohol and opioid dependence. Addiction. 2004;99:1382–1392. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00884.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Volpicelli JR, Rhines KC, Rhines JS, Volpicelli LA, Alterman AI, O’Brien CP. Naltrexone and alcohol dependence: role of patient compliance. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1997;54:737–742. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1997.01830200071010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Harris KM, DeVries A, Dimidjian K. Trends in naltrexone use among members of a large private health plan. Psychiatr Serv. 2004;55:221. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.55.3.221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hermos JA, Young MM, Gagnon DR, Fiore LD. Patterns of dispensed disulfiram and naltrexone for alcoholism treatment in a veteran patient population. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2004;28:1229–1235. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000134234.39303.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kranzler HR, Stephenson JJ, Montejano L, Wang S, Gastfriend DR. Persistence with oral naltrexone for alcohol treatment: implications for healthcare utilization. Addiction. 2008;103:1801–1808. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02345.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kranzler HR, Montejano LB, Stephenson JJ, Wang S, Gastfriend DR. Effects of naltrexone treatment for alcohol-related disorders on healthcare costs in an insured population. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2010;34 doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2010.01185.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Johnson BA. Naltrexone long-acting formulation in the treatment of alcohol dependence. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2007;3:741–749. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Abraham AJ, Roman PM. Early adoption of injectable naltrexone for alcohol use disorders: findings in the private treatment sector. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2010;71:460–466. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2010.71.460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kranzler HR, Wesson DR, Billot L. Naltrexone depot for treatment of alcohol dependence: a multicenter, randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2004;28:1051–1059. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000130804.08397.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pettinati HM, Gastfriend DR, Dong Q, Kranzler HR, O’Malley SS. Effect of extended-release naltrexone (XR-NTX) on quality of life in alcohol-dependent patients. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2009;33:350–356. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2008.00843.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Garbutt JC, Kranzler HR, O’Malley SS, Gastfriend DR, Pettinati HM, Silverman BL, et al. Efficacy and tolerability of long-acting injectable naltrexone for alcohol dependence: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2005;293:1617–1625. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.13.1617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.O’Malley SS, Garbutt JC, Gastfriend DR, Dong Q, Kranzler HR. Efficacy of extended-release naltrexone in alcohol-dependent patients who are abstinent before treatment. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2007;27:507–512. doi: 10.1097/jcp.0b013e31814ce50d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee JD, Grossman E, DiRocco D, Truncali A, Hanley K, Stevens D, et al. Extended-release naltrexone for treatment of alcohol dependence in primary care. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2010;39:14–21. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2010.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mark TL, Montejano LB, Kranzler HR, Chalk M, Gastfriend DR. Comparison of healthcare utilization among patients treated with alcoholism medications. Am J Man Care. 2010;16:879–888. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ettner SL, Frank RG, McGuire TG, Hermann RC. Risk adjustment alternatives in paying for behavioral health care under Medicaid. Health Serv Res. 2001;36:793–811. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.D’Hoore W, Sicotte C, Tilquin C. Risk adjustment in outcome assessment: the Charlson comorbidity index. Methods Inf Med. 1993;32:382–387. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Manning WG, Mullahy J. Estimating log models: to transform or not to transform? J Health Econ. 2001;20:461–494. doi: 10.1016/s0167-6296(01)00086-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Baser O, Chalk M, Rawson R, Gastfriend DR. Cost and utilization outcomes with alcohol dependence treatments. Am J Manag Care. in submission. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.