Abstract

Purpose

To present a novel method for meta-analysis of the fractionation sensitivity of tumors as applied to prostate cancer in the presence of an overall time factor.

Methods and Materials

A systematic search for radiation dose-fractionation trials in prostate cancer was performed using PubMed and by manual search. Published trials comparing standard fractionated external beam radiation therapy with alternative fractionation were eligible. For each trial the α/β ratio and its 95% confidence interval (CI) were extracted, and the data were synthesized with each study weighted by the inverse variance. An overall time factor was included in the analysis, and its influence on α/β was investigated.

Results

Five studies involving 1965 patients were included in the meta-analysis of α/β. The synthesized α/β assuming no effect of overall treatment time was −0.07 Gy (95% CI −0.73-0.59), which was increased to 0.47 Gy (95% CI −0.55-1.50) if a single highly weighted study was excluded. In a separate analysis, 2 studies based on 10,808 patients in total allowed extraction of a synthesized estimate of a time factor of 0.31 Gy/d (95% CI 0.20-0.42). The time factor increased the α/β estimate to 0.58 Gy (95% CI −0.53-1.69)/1.93 Gy (95% CI −0.27-4.14) with/without the heavily weighted study. An analysis of the uncertainty of the α/β estimate showed a loss of information when the hypofractionated arm was underdosed compared with the normo-fractionated arm.

Conclusions

The current external beam fractionation studies are consistent with a very low α/β ratio for prostate cancer, although the CIs include α/β ratios up to 4.14 Gy in the presence of a time factor. Details of the dose fractionation in the 2 trial arms have critical influence on the information that can be extracted from a study. Studies with unfortunate designs will supply little or no information about α/β regardless of the number of subjects enrolled.

Introduction

Fifteen years ago, a bioeffect modeling study recommended hyperfractionation as a potential strategy for improving the therapeutic ratio in prostate cancer (1), on the basis of the presumed absence of an overall time factor for prostate cancer combined with the dogma of the time that the fractionation sensitivity of late effects was higher than that of tumors. Later, Brenner and Hall (2) used the clinically observed equivalent outcome after permanent implant brachytherapy and external beam radiation therapy to derive a low α/β ratio of 1.5 Gy (95% confidence interval [CI] 0.8-2.2) for prostate cancer. A flurry of modeling studies and overviews followed Brenner and Hall’s pioneering article, almost invariably concluding that α/β for prostate cancer was indeed low. Only few studies challenged the general assumption that the overall time factor was zero, although a study by Wang et al in 2003 (3) indicated that the inclusion of a time factor would increase the α/β ratio to 3.1 Gy. However, in 2008, D’Amrosio et al (4) showed that in a series of 1796 patients, a model with a nonzero time factor gave a statistically superior fit to the outcome data. Thames et al (5) arrived at the same conclusion in 2010 in an independent dataset. In an editorial, Baumann et al (6) speculated that this could give rise to increased α/β estimates, which in turn could imply that hypofractionated schedules could turn out to be inferior to standard fractionation, in accordance with Wang et al’s predictions from 2003 (3).

In parallel with the fractionation sensitivity discussion, advances in radiation delivery techniques have allowed delivery of very high radiation doses to the prostate, with acceptable toxicity. A key quantity in estimating the clinical gain from target dose escalation is the steepness of the radiation dose-control curve, which was recently derived for prostate cancer from a meta-analysis of a series of randomized dose-escalation studies (7).

Here, a method for estimating the α/β ratio from clinical fractionation studies of external beam radiation therapy is presented, and a meta-analysis of the results is performed. Second, a best estimate of the time factor from 2 recent publications is derived and its impact on the synthesized estimate of α/β explored.

Methods and Materials

Assuming no effect of overall time, an estimate of α/β from 2 isoeffective trial arms with different dose fractionation is

| (1) |

where Dexp and Dctr are the total doses in the experimental and control (normo-fractionated) arms, and dexp and dctr are the corresponding fraction doses.

However, trial arms are rarely isoeffective. We assumed a logistic dose-response model of the tumor control probability p with normo-fractionation

| (2) |

Here, γ50 is the normalized steepness of the dose-response curve at 50% tumor control probability and D50 the dose required to reach 50% control (8). From the observed tumor control in the control arm, pctr, and Dctr, the dose-response curve allows estimation of Dequi, the dose in the normo-fractionated arm that would have produced an isoeffective tumor outcome. Note that these calculations rely on having an estimate of g50 from Eq. 2

Here pexp is the observed tumor control probability in the experimental arm. We used the hazard ratio to estimate the control probability in the experimental arm as , which is preferable to a point estimate of pexp because it uses the events from the whole range of observation times. In the presence of a time factor, the expressions are

| (3) |

where δprolif is the dose lost per day, and ΔT is the overall treatment time in the control arm minus that of the experimental arm. Traditionally, δprolif has been denoted Dprolif, but to avoid confusion with the total doses in the equation, we chose to deviate from this convention and follow the statistical convention of using Greek letters to denote model parameters. The index “prolif” is also partly conventional, referring to the hypothesis that the tumor time factor reflects (accelerated) tumor cell proliferation.

The standard error of Dequi, SDequi, may be found by propagation of error from the standard error of γ50, Sγ50, and the reported hazard ratio θ and its standard error Sθ

Finally, the standard error of the α/β estimate was calculated by propagation of error .

Thus, the standard error of α/β is derived from the uncertainty of the hazard ratio of control between the trial arms, θ, and the statistical uncertainty of γ50 and δprolif. Further details are given in Appendix e1 (available online).

The inverse variance of α/β was then used as the weight assigned to each estimate, to synthesize results across trials.

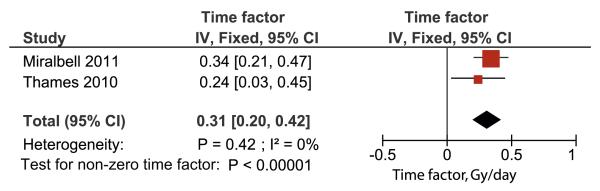

Estimates of γ50 = 0.78 and its standard error 0.16 came from our recently published meta-analysis (7, 9). When modeling the effect of proliferation, we used the synthesized value of 0.31 Gy/d with a standard error of 0.056 Gy/d from the studies of Thames et al (5) and Miralbell et al (10) as detailed below (compare Fig. 1). Furthermore, we use a modified value of γ50 = 1.0 (standard error 0.20), which was calculated as in reference 7 but with the synthesized time factor taken into account.

Fig. 1.

A synthesis of the observed time factors of Thames et al (5) and Miralbell et al (10). It should be noted that a formal systematic search and meta-analysis was not possible, and several studies discuss the effect of overall treatment time without providing data amenable for synthesis in the present analysis (see, eg, reference 4). IV = inverse variance weighted; fixed = fixed-effects model; CI = confidence interval.

Studies were identified from PubMed using the search string “radiotherapy[mh] AND prostate AND (hypofractionated OR hypofractionation OR fractionation) NOT brachytherapy” complemented by a hand search of included articles and recent reviews. The search was performed July 13, 2011 and was limited to English-language articles published after 1990. For a study to be eligible, the patients should suffer from prostate cancer (any risk) treated with radiation without previous prostatectomy, and the study should report treatment outcome as biochemical no evidence of disease (any definition) after a standard (1.8-2 Gy per fraction) and an altered fractionation schedule. Thus, single-arm studies were excluded, but no other restrictions were imposed on study design. The α/β estimates were synthesized in a meta-analysis by inverse variance weighting of the α/β estimate as explained above. I2 and Cochran’s Q were used as measures of heterogeneity between studies. I2 is a measure of the percentage of heterogeneity not explained by chance alone (ie, a high value of I2 [50% is sometimes used as the limit] suggests heterogeneity among studies). Statistical analyses were performed using Review Manager software version 5.1.2 (11).

Results

The search resulted in 327 unique articles. Most of these were excluded because they (1) did not report original clinical data (eg, reviews, models, planning studies), (2) were focused on radiation therapy technique rather than clinical outcome, or (3) did not include a normo-fractionated arm. Table 1 summarizes the 5 eligible studies comprising a total of 1965 patients (12-16).

Table 1.

Summary of included studies

| Study (reference) | Patients (n) | Risk groups included | Design | ADT | bNED definition |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arcangeli 2010 (12) | 168 | High | Randomized | Yes (9 mo) | Phoenix |

| Leborgne 2011 (13) | 274 | All | Retrospective | Mixed | Phoenix |

| Lukka 2005 (14) | 936 | All | Randomized | No | ASTRO |

| Valdagni 2005 (15) | 370 | All | Prospective nonrandomized |

Mixed | ASTRO |

| Yeoh 2011 (16) | 217 | All | Randomized | No | Phoenix |

| Standard arm |

Experimental arm |

Follow-up (mo) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study (reference) | Difference in treatment time (d) |

Dose (Gy)/fx |

bNED (%) |

Dose (Gy)/fx | bNED (%) (risk group) |

Median (std arm/exp arm) |

at bNED evaluation |

| Arcangeli 2010 (12) | 21 | 80/40 | 79 | 62/20 | 87 | 35/32 | 36 |

| Leborgne 2011 (13) | 22 | 78/39 | 88.7 | 60 or 63 Gy/20 | 89.4 | 63/66 | 60 |

| Lukka 2005 (14) | 17 | 66/33 | 47 | 52.5/20 | 40 | 68 | 60 |

| Valdagni 2005 (15) | 0 | 74/37 | 70 | 79.2/66* | 83 | 25/38 | 60 |

| Yeoh 2011 (16) | 16.8 | 64/32 | 56 | 55/20 | 57 | 90 | 60 |

Abbreviations: ADT = androgen deprivation therapy; ASTRO = American Society for Radiation Oncology; bNED = biochemical no evidence of disease; exp = experimental; fx = fractions; std = standard.

Median of varying prescription: 1.2 Gy/fraction to 70-82.8 Gy.

Two recent studies found an influence of overall treatment time on the outcome of prostate cancer radiation therapy (5, 10). The results of these 2 studies are synthesized by inverse variance weighting of the reported δprolif in Fig. 1. A detailed derivation of δprolif and its standard error in EQD2 terms from reference 10 is supplied as Appendix e2. The synthesized estimate is δprolif = 0.31 Gy/d (95% CI 0.20-0.42). However, a formal systematic search resulted in several studies that investigated the effect of treatment protraction but did not provide data amenable for meta-analysis. Our estimate of δprolif is therefore, to the best of our knowledge, based on all published, analyzable data.

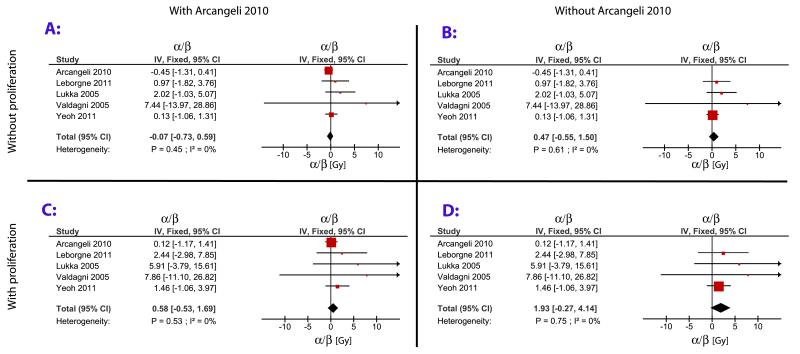

Figure 2 presents the results of the meta-analysis as forest plots, with the weight of each study proportional to the area of the square and the horizontal line representing its 95% CI. The 4 panels display analyses with and without an overall time factor and with and without the heavily weighted study by Arcangeli et al (12). Our α/β estimate from Leborgne et al (13) differs from the value reported in their original publication, 1.86 Gy(95% CI 0.7-5.1), because we used a different approach in calculating α/β.

Fig. 2.

Meta-analysis of the α/β ratio including all studies (A and C) and excluding the heavily weighted study by Arcangeli et al (12) (B and D). Assuming no effect of overall treatment time (A and B) and assuming δprolif = 0.31 Gy/d (C and D). IV = inverse variance weighted; Fixed = fixed-effects model; CI = confidence interval.

Analysis without an overall time factor gave a negative α/β = −0.07 Gy (95% CI −0.73-0.59). Excluding the heavily weighted study by Arcangeli et al (12) increased α/β to 0.47 Gy (95% CI −0.55-1.50).

Accounting for overall treatment time, the 5 studies gave α/β = 0.58 Gy (95% CI −0.53-1.69), but if Arcangeli et al’s study (12) was excluded the estimate increased to α/β = 1.93 Gy (95% CI −0.27-4.14).

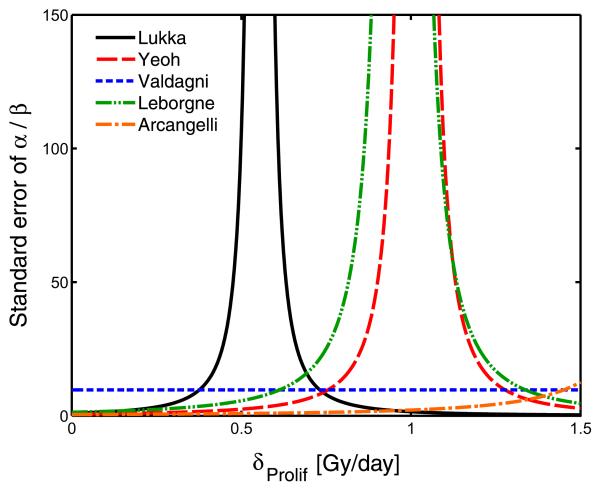

The large influence of Arcangeli et al’s study (12) was surprising in view of the relatively modest number of patients and the short follow-up. Figure 3 shows the standard error of the α/β estimate (which is inversely correlated with study weight) as a function of δprolif. Apart from the Valdagni et al study (15), in which overall treatment time was identical in both arms, all of the standard errors depend strongly on the value of the δprolif, with a mathematical singularity occurring at Dequi=Dexp + δprolifΔT (compare Eq. 3). This causes the standard error of the α/β estimate to tend to infinity, and consequently the study weight tends to zero. Larger studies show a steeper divergence, but this behavior is seen regardless of trial size. In particular, if Dequi=Dexp + δprolifΔT, no information on α/β could be extracted, irrespective of the sample size.

Fig. 3.

The standard error of the α/β ratio vs. the time factor, δprolif. A singularity, where the uncertainty of the estimate explodes, exists for all studies except Valdagni et al (15), which is insensitive to δprolif because both arms have same overall treatment time. The large number of patients in the study by Lukka et al (14) results in a narrower peak, but the standard error of the α/β estimate is still larger than in Arcangeli et al (12) for a wide range of δprolif, including δprolif = 0.

Discussion

Two studies reporting an influence of overall treatment time show good mutual agreement: the synthesized δprolif is estimated at 0.31 Gy/d and is highly significantly different from zero. Although a risk of publication bias in selecting these studies is possible, the high number of patients involved and the highly significant result support the hypothesis that overall treatment time affects the outcome of prostate cancer radiation therapy. This will influence α/β estimates from trials in which the duration of the compared schedules differs.

A low α/β for prostate cancer is estimated, with or without the study by Arcangeli et al (12), as long as overall treatment time is not included in the model.

Including all studies in the analysis produces a low α/β estimate even in the presence of a time factor, but this result is driven by the heavily weighted study by Arcangeli et al (12), producing α/β estimates with low dependence on δprolif (Fig. 2). However, the Arcangeli study was not large and had relatively short follow-up. Possibly this study was assigned a very high weight, owing to a random variation of the odds ratio rendering the α/β estimate from this trial very low and thereby making Dequi − (Dexp + δproligΔT) large by coincidence. Such a weighting bias has previously been described in meta-analyses performed directly on risk ratios or risk differences (17), and the nonlinear equations involved in this meta-analysis may amplify the problem. In a sensitivity analysis, excluding the study by Arcangeli et al (12), the upper limit of the 95% CI for α/β is 4.14 Gy.

Another assumption of our analysis is that response follows a logistic dose-response curve (Eq. 2), which allows some control at zero dose but assumes 100% control at infinite dose. Thus it is implicitly assumed that disease outside of the irradiated region does not contribute to the observed biochemical failures.

Two recently published α/β estimates derived from multi-institutional case series using different data analytical approaches are in very good agreement with the present estimate. Miralbell et al (10) estimate α/β at 4.0 Gy (95% CI 2.0-6.2 Gy) with overall treatment time included in the model. Synthesizing these 2 estimates yields an α/β value of 3.0 Gy (95% CI 1.50-4.54) (data not shown). Additionally, Proust-Lima et al (18) analyzed several cohorts but without adjusting for overall treatment time, obtaining an α/β estimate of 1.55 Gy (95% CI 0.46-4.52) (18). If our result is synthesized with Proust-Lima, we find α/β = −0.69 Gy (95% CI −0.23-1.60) (data not shown). Williams et al (19) used individual fraction size data in a large patient database to reach estimates of α/β in the range of 3.7 Gy but with wide CIs. The good agreement with published studies when Arcangeli et al (12) is excluded leads us to have a slight preference for the analyses shown in Figure 2B and D. These data also yield more conservative and perhaps more realistic CIs.

Another insight provided by this analysis is that the singularity in the α/β estimate for a certain value of the time factor may assign very low weight to a trial despite a large sample size. In case of a zero time factor, the singularity corresponds to Dequi=Dexp (ie, the predicted dose of the standard fractionated arm resulting in the same control probability as the test arm is equal to the physical dose in the test arm). This explains the low weight of Lukka et al’s study (14) compared with Arcangeli et al’s (12): the schedules compared by Lukka et al are much closer to the singularity and therefore provide a relatively uncertain α/β estimate despite a large sample size. However, the large sample size of Lukka et al results in a relatively narrow peak of uncertainty around the singularity (compare Fig. 3). The Valdagni et al study (15) is insensitive to the value of δprolif because the overall treatment time was identical in the compared schedules.

The fact that inclusion of an overall time factor leads to increased α/β estimates (3) could potentially affect the bio-effective dose of some of the hypofractionation schemes that are currently being tested. Table 2 shows the effective dose and estimated control probability of some illustrative fractionation schedules. The calculations are performed with α/β = 0.47 Gy without an overall time factor, α/β = 1.93 Gy with an overall time factor, and finally for the “worst-case” scenario of α/β = 4.14 Gy and an effect of overall treatment time.

Table 2.

Equivalent doses in 2-Gy fractions (EQD2) for a standard dose fractionation scheme and illustrative hypofractionated regimens

| α/β = 0.47 Gy δprolif = 0 |

α/β = 1.93 Gy δprolif = 0.31 Gy/d |

α/β = 4.14 Gy δprolif = 0.31 Gy/d |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dose (Gy) | Fractions | Dose/ fraction (Gy) |

OT (d) | EQD2 | bNED @ 5 y (%) | EQD2 | bNED @ 5 y (%) | EQD2 | bNED @ 5 y (%) |

| 78 | 39 | 2 | 53 | 78 | 70 | 78 | 70 | 78 | 70 |

| 72 | 30 | 2.4 | 42 | 84 | 76 | 83 | 76 | 80 | 73 |

| 57 | 19 | 3 | 25 | 80 | 72 | 80 | 73 | 75 | 66 |

| 60 | 20 | 3 | 26 | 84 | 76 | 84 | 77 | 78 | 70 |

| 58 | 16 | 3.63 | 26 | 96 | 85 | 90 | 83 | 82 | 75 |

| 51.6 | 12 | 4.3 | 19 | 100 | 88 | 92 | 85 | 81 | 74 |

| 42.7 | 7 | 6.1 | 15 | 114 | 94 | 99 | 89 | 83 | 76 |

| 38 | 5 | 7.6 | 7 | 124 | 96 | 106 | 93 | 87 | 80 |

| 40 | 5 | 8 | 29 | 137 | 98 | 108 | 94 | 87 | 80 |

Abbreviation: OT = overall treatment time.

We assumed 5-y biochemical no evidence of disease (bNED) of 70% of the current clinical standard (78 Gy/39 fractions) and used a steepness of the dose-response curve, γ50 = 0.78 Gy for δprolif = 0 and γ50 = 1.0 when the synthesized time factor was taken into account (δprolif = 0.31 Gy/d).

Although there is a potential loss of tumor control of up to 4% in the worst-case scenario, the selected hypofractionated regimens deliver tumor control probabilities on par with the standard fractionated regimen when the most probable values of α/β and δprolif are used. However, sufficient uncertainty remains, so that hypofractionated schedules should only be tested in controlled clinical trials. In particular, the above assumptions of the present study mean that the safety of the hypofractionated regimens from Table 2 should still be tested, and the results of randomized trials are therefore eagerly awaited.

To summarize, the present meta-analysis supports a low α/β ratio for prostate cancer even in the presence of a time factor. Much more knowledge will be gained when the present fractionation studies are finished and the data reported. In particular, the United Kingdom CHHiP trial (20), having recently closed after enrolling 3163 patients, will likely be very informative. This study randomizes between a standard fractionation schedule and 2 hypofractionated arms with the same dose per fraction, meaning that a within-study hypofractionated dose response curve can be estimated.

In conclusion, if it is assumed that there is no effect of overall treatment time, the outcome of the clinical fractionation studies points toward a very low α/β ratio. Somewhat surprisingly, the uncertainty of the α/β estimate of a fractionation study depends heavily on the exact schedules chosen and not just the sample size. If an effect of overall treatment time is taken into account, the α/β estimate increases as seen in previous studies (3). The best estimate of α/β remains low, but this estimation is largely driven by the results of a single study with a—in this context—fortunate choice of treatment arms. If that study is excluded, α/β values exceeding 4 Gy can still not be ruled out by the outcomes of the published studies.

Supplementary Material

Summary.

This was a meta-analysis of the α/β ratio for prostate cancer from 5 fractionation studies of external beam radiation therapy involving a total of 1965 patients. An overall time factor is included in the analysis, and its influence on α/β is investigated.

Acknowledgments

Supported by Danish Cancer Society Grant No. R27-A1358-10-S4. S.M.B. is supported by National Cancer Institute Grant No. 2P30-CA-014520-34. I.R.V. is supported by The Lundbeck Foundation Center for Interventional Research in Radiation Oncology and The Danish Council for Strategic Research.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: none.

Supplementary material for this article can be found at www.redjournal.org.

References

- 1.Fowler JF, Ritter MA. A rationale for fractionation for slowly proliferating tumors such as prostatic adenocarcinoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1995;32:521–529. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(95)00545-A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brenner DJ, Hall EJ. Fractionation and protraction for radiotherapy of prostate carcinoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1999;43:1095–1101. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(98)00438-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang JZ, Guerrero M, Li XA. How low is the alpha/beta ratio for prostate cancer? Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2003;55:194–203. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(02)03828-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.D’Ambrosio DJ, Li T, Horwitz EM, et al. Does treatment duration affect outcome after radiotherapy for prostate cancer? Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2008;72:1402–1407. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2008.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thames HD, Kuban D, Levy LB, et al. The role of overall treatment time in the outcome of radiotherapy of prostate cancer: an analysis of biochemical failure in 4839 men treated between 1987 and 1995. Radiother Oncol. 2010;96:6–12. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2010.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baumann M, Holscher T, Denham J. Fractionation in prostate cancer—is it time after all? Radiother Oncol. 2010;96:1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2010.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Diez P, Vogelius IS, Bentzen SM. A new method for synthesizing radiation dose-response data from multiple trials applied to prostate cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2010;77:1066–1071. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2009.06.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bentzen SM, Tucker SL. Quantifying the position and steepness of radiation dose-response curves. Int J Radiat Biol. 1997;71:531–542. doi: 10.1080/095530097143860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vogelius IR, Bentzen SM. In response to Dr. Williams. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2010;80:639–640. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Miralbell R, Roberts SA, Zubizarreta E, et al. Dose-fractionation sensitivity of prostate cancer deduced from radiotherapy outcomes of 5969 patients in seven international institutional datasets: alpha/beta = 1.4 (0.9-2.2) Gy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2012;82:e17–e24. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2010.10.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.The Cochrane Collaboration . Review Manager (RevMan) [computer program] The Nordic Cochrane Centre; Copenhagen: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Arcangeli G, Saracino B, Gomellini S, et al. A prospective phase III randomized trial of hypofractionation versus conventional fractionation in patients with high-risk prostate cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2010;78:11–18. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2009.07.1691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Leborgne F, Fowler J, Leborgne JH, et al. Later outcomes and alpha/beta estimate from hypofractionated conformal three-dimensional radiotherapy versus standard fractionation for localized prostate cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2012;82:1200–1207. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2010.12.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lukka H, Hayter C, Julian JA, et al. Randomized trial comparing two fractionation schedules for patients with localized prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:6132–6138. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.06.153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Valdagni R, Italia C, Montanaro P, et al. Is the alpha-beta ratio of prostate cancer really low? A prospective, non-randomized trial comparing standard and hyperfractionated conformal radiation therapy. Radiother Oncol. 2005;75:74–82. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2004.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yeoh EE, Botten RJ, Butters J, Di Matteo AC, Holloway RH, Fowler J. Hypofractionated versus conventionally fractionated radiotherapy for prostate carcinoma: final results of phase III randomized trial. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2011 Dec 1;81(5):1271–1278. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2010.07.1984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tang JL. Weighting bias in meta-analysis of binary outcomes. J Clin Epidemiol. 2000;53:1130–1136. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(00)00237-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Proust-Lima C, Taylor JM, Secher S, et al. Confirmation of a low alpha/beta ratio for prostate cancer treated by external beam radiation therapy alone using a post-treatment repeated-measures model for PSA dynamics. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2011;79:195–201. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2009.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Williams SG, Taylor JM, Liu N, et al. Use of individual fraction size data from 3756 patients to directly determine the alpha/beta ratio of prostate cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2007;68:24–33. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2006.12.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Khoo VS, Dearnaley DP. Question of dose, fractionation and technique: ingredients for testing hypofractionation in prostate cancer—the CHHiP trial. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol) 2008;20:12–14. doi: 10.1016/j.clon.2007.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.