Abstract

The serrated pathway to colorectal tumor formation involves oncogenic mutations in the BRAF gene, which are sufficient for initiation of hyperplastic growth but not for tumor progression. A previous analysis of colorectal tumors revealed that overexpression of splice variant Rac1b occurs in around 80% of tumors with mutant BRAF and both events proved to cooperate in tumor cell survival. Here, we provide evidence for increased expression of Rac1b in patients with inflamed human colonic mucosa as well as following experimentally induced colitis in mice. The increase of Rac1b in the mouse model was specifically prevented by the nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug ibuprofen, which also inhibited Rac1b expression in cultured HT29 colorectal tumor cells through a cyclooxygenase inhibition.independent mechanism. Accordingly, the presence of ibuprofen led to a reduction of HT29 cell survival in vitro and inhibited Rac1b-dependent tumor growth of HT29 xenografts. Together, our results suggest that stromal cues, namely, inflammation, can trigger changes in Rac1b expression in the colon and identify ibuprofen as a highly specific and efficient inhibitor of Rac1b overexpression in colorectal tumors. Our data suggest that the use of ibuprofen may be beneficial in the treatment of patients with serrated colorectal tumors or with inflammatory colon syndromes.

Introduction

Colorectal cancer (CRC) represents one of the leading causes of cancer mortality in the Western world. The majority of cases are sporadic tumors that present an adenoma-carcinoma sequence involving somatic mutations in the adenomatous polyposis coli (APC) tumor suppressor gene and in the oncogene KRAS [1]. In addition, about 10% to 15% of cases are characterized by a high level of DNA microsatellite instability as a result of somatic inactivation of a DNA mismatch repair gene. These tumors mainly occur in the proximal colon segment and carry a global CpG island hypermethylation phenotype (eventually including the mismatch repair gene hMLH1) and oncogenic mutations in the BRAF gene [2]. They follow a different neoplastic pathway that is independent of KRAS and has been designated as the serrated polyp pathway [3]. Genotyping of microdissected polyps has confirmed that mutations in KRAS and BRAF are alternative early, tumor-initiating events and that serrated polyps harbor BRAF mutations with a DNA methylation phenotype [4–7].

The most frequent BRAF mutation is BRAF-V600E and occurs predominantly inmelanoma, thyroid, and colorectal tumors. Although the mutation activates the protein's kinase activity and stimulates mitogenactivated protein (MAP) kinases, BRAF-V600E alone has less oncogenic potential than mutant KRAS in cell transformation assays [8]. We recently described that about 80% of BRAF-V600E-positive colorectal tumors also overexpress Rac1b [9], a highly activated splice variant of the signaling GTPase Rac1. Rac1b lacks down-regulation by Rho-GDI, exists predominantly in the GTP-bound active conformation, and promotes cell cycle progression and cell survival through activation of the transcription factor nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (NF-κB) [10–12]. Importantly, colorectal tumor cells expressing BRAF-V600E and Rac1b were highly sensitive to combined inhibition of both events, leading to 80% cell death [9]. Based on the findings that BRAF-V600E and hyperactive Rac1b functionally cooperate in tumor cells, a genetic pathway was proposed for a subtype of colorectal tumors [9,13] that are initiated by a BRAFV600E mutation but later require overexpression of hyperactive Rac1b to allow further tumor progression. It remains to be established, however, how the overexpression of Rac1b is triggered in tumor cells.

Tumor cells are known to interact with the stromal microenvironment. For instance, tumor cells produce cytokines to which stromal cells respond with the secretion of proteases that remodel the extracellular matrix, of pro-angiogenic factors that attract blood vessels, and of mitogenic factors that feedback on tumor cell survival. Vice versa, cytokines released by the tumor microenvironment are now known to further promote tumor cell growth at various stages of tumor development [14,15]. In addition, stimulation of the NF-κB pathway is simultaneously promoting an inflammatory response and a pro-survival signal for epithelial cells [16,17]. Interestingly, colon tumors with microsatellite instability or BRAF mutation are characterized by abundant lymphocytic infiltration. Besides inflammation caused by infectious or environmental agents, chronic inflammatory states in organs or tissues have also been identified as a risk factor for cancer development and promoted the prophylactic administration of anti-inflammatory drugs to patients [18–20].

Here, we describe an increase in Rac1b expression in inflamed colonic as well as following experimental induction of colitis in laboratory mice. We further identified the anti-inflammatory drug ibuprofen as a specific inhibitor of both the increase in Rac1b expression and the survival of corresponding Rac1b overexpressing tumor cells in vivo.

Materials and Methods

Human Tissue Samples

All research programs involving the use of human tissue were approved and supported by the INSERM (French National Institute for Health and Medical Research) Ethics Committee and these tissues are considered as surgical waste in accordance with French ethical laws (L.1211-3–L.1211-9).

Human colonic mucosa specimens were obtained from patients who had undergone surgery for colonic inflammation (two patients with Crohn's disease and four patients with diverticulitis). Four of the six inflamed samples were matched with the corresponding distant macroscopically healthy mucosa (the two patients with Crohn's disease and the two patients with diverticulitis). Two additional samples of control mucosa were obtained from colonic resections for colon cancer and dissected from at least 10 cm from the tumors. Tissue samples were snap frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at -80°C until use.

Cell Culture, Transfection, and Selection Conditions

HT29 cells were maintained in RPMI and SW480 in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium, both supplemented with 10% (vol/vol) fetal calf serum (all reagents from Gibco Invitrogen Corporation, Barcelona, Spain). The normal colonocyte cell line NCM460 [21] was received by a licensing agreement with INCELL Corporation (San Antonio, TX). The cells were routinely propagated under standard conditions in M3:10 medium (INCELL) containing 10% fetal calf serum.

For biochemical assays, cells were seeded in 24- or 96-well plates at 2 x 105 or 3 x 104 cells/well and treated with either vehicle (DMSO) or the indicated concentrations of the various DMSO-diluted anti-inflammatory compounds (all from Sigma-Aldrich, Madrid, Spain). Cells were then analyzed at the indicated time points by various methodologies (see below).

To generate cell lines stably expressing ectopic green fluorescent protein (GFP) or GFP-Rac1b wild type (wt) [10], HT29 cells were transfected with either vector using LIPOFECTAMINE 2000 (Invitrogen), according to the manufacturer's instructions, and selected for 4 weeks with G418 (Sigma-Aldrich) at 500 µg/ml. Brighter clones were then collected, pooled and cultured for 2 additional weeks before use in biochemical assays or mouse xenografts and maintained at 250 µg/ml G418 while in culture.

SiRNA and Inducible BRAF-V600E Expression

SiRNA-mediated depletion of endogenous Rac1b and BRAF-V600E expression in HT29 cells was performed as previously described [9]. For inducible expression of BRAF-V600E in NCM460, the complete BRAF coding sequence was amplified by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) from a pEGFP-BRAF-V600E construct [9] and subcloned using SacI and SalI restriction sites into the pPTuner vector of the ProteoTuner Shield System N (Clontech, Mountain View, CA). This vector generates a fusion protein with the FKBP (L106P) destabilization domain that causes the rapid constitutive degradation of the fusion protein until the addition of Shield1 to the culture medium. Shield1 is a membrane permeable stabilizing ligand that binds to the destabilization domain tag, “shielding” the fusion protein from proteasomal degradation and thus allowing its rapid accumulation.

Reverse Transcription-PCR and Real-Time PCR

Colonic mucosa and xenograft-derived tumors were disrupted using a Polytron apparatus and RNA was isolated using NucleoSpin RNA II Kit (Macherey-Nagel, Hoerdt, France). RNA from cell line cultures was extracted with the RNAeasy Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). One microgram of total RNA was then reverse transcribed using random primers (Invitrogen) and Ready-to-Go You-Prime Beads (GE Healthcare, Buckinghamshire, United Kingdom).

Real-time relative quantification was performed as described [9] with minor alterations, namely, all mouse samples were analyzed against a cDNA sample prepared from total RNA from NIH 3T3 cells, and the reverse primer from the “total Rac1 detector” pair was changed to 5′-GAT GAT AGGAGT ATT GGG ACA GT to eliminatemouse/human mismatches.

Immunofluorescence Microscopy

Cells grown on coverslips were fixed with 4% (vol/vol) formaldehyde (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) in phosphate-buffered saline and permeabilized with 0.2% (vol/vol) Triton X-100 (Sigma) in phosphate-buffered saline. Cells were then stained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI; Sigma), and images were recorded on a Leica TCS-SPE confocal microscope and processed with Adobe Photoshop software.

Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate-Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis and Western Blot Analysis

Samples were prepared and detected as described [9]. The antibodies used in this study were rabbit anti-GFP ab290 from Abcam (Cambridge, United Kingdom), polyclonal rabbit anti-Rac1b (Millipore, Billerica, MA, #09-271), and mouse anti-β-tubulin clone Tub2.1 from Sigma-Aldrich (as a loading control). For densitometric analysis, film exposures from at least three independent experiments were digitalized and analyzed using ImageJ software National Institutes of Health (NIH).

Cell Viability and Prostaglandin E2 Assays

HT29 cells seeded in 96-well plates were treated for the indicated periods with the given nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) concentrations. Cell viability was evaluated using the CellTiter-Glo ATP-based luminescence assay (Promega, Madison, WI) and plotted as percent of DMSO-treated cells at the same time points. The amount of prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) released by the cells to the culture medium was determined using the DetectX PGE2 Chemiluminescent Enzyme Immunoassay (Arbor Assays, Ann Arbor, MI) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Luminescent signals were recorded with a Lucy 2 microtiter plate luminometer (Anthos, Krefeld, Germany). All results were confirmed by at least three independent experiments.

Mice Dextran Sulfate Sodium Treatment and Tumor Xenografts

All experiments on mice were performed in accordance with institutional and national guidelines and regulations, and ethics approval was obtained from the INSERMEthics Committee. Male C57BL/6 and nude mice were purchased from Charles River Laboratories (Lille, France).

To induce colitis, C57BL/6 mice (10–12 weeks old) received dextran sulfate sodium (DSS; 36–50 kDa; MP Biomedicals Europe, Illkirch, France) dissolved in sterile tap water (3% wt/vol) or ibuprofen (1 mg/ml) or a combination of the two compounds. DSS treatment was carried out for 5 days, followed by two recovery days, whereas ibuprofen was administered throughout the 7 days. Control groups received sterile tap water. Body weight was monitored daily in all groups. Mice were killed by cervical dislocation. The cecum was removed and the remainder of the colon was divided into proximal and distal halves.

For tumorigenicity assay in nude mice, exponentially growing parental, GFP, or GFP-Rac1b wt stably expressing HT29 cells were harvested and resuspended to a concentration of 2 x 107/ml. Cells (2 x 106) were inoculated in the right flank of mice (day 0). Animals were then fed with aspirin or ibuprofen in drinking water at doses adjusted for body mass from regular human posologies (1 mg/ml). Tumor development was followed weekly by caliper measurement along two orthogonal axes, length (L) and width (W). The volume (V) of tumor was calculated by the equation for ellipsoid (V = L x W2 x π/6). After euthanasia on day 28, tumors were dissected from neighboring connective tissues and weighed. Then, they were divided into three parts and snap frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at -80°C until further processing.

Statistical Analysis

All results are expressed as means ± SEM. Differences between controls and the multiple treatments applied to mice or cultured cells were evaluated by one-way analysis of variance test, followed by unpaired two-tailed Student's t tests when significant results were obtained. When relevant, direct statistical comparisons between two groups were made using unpaired two-tailed t tests. The level of significance was set at P ≤ .05.

Results

BRAF-V600E Mutation and Rac1b Overexpression Constitute Two Independent Events in Colorectal Tumorigenesis

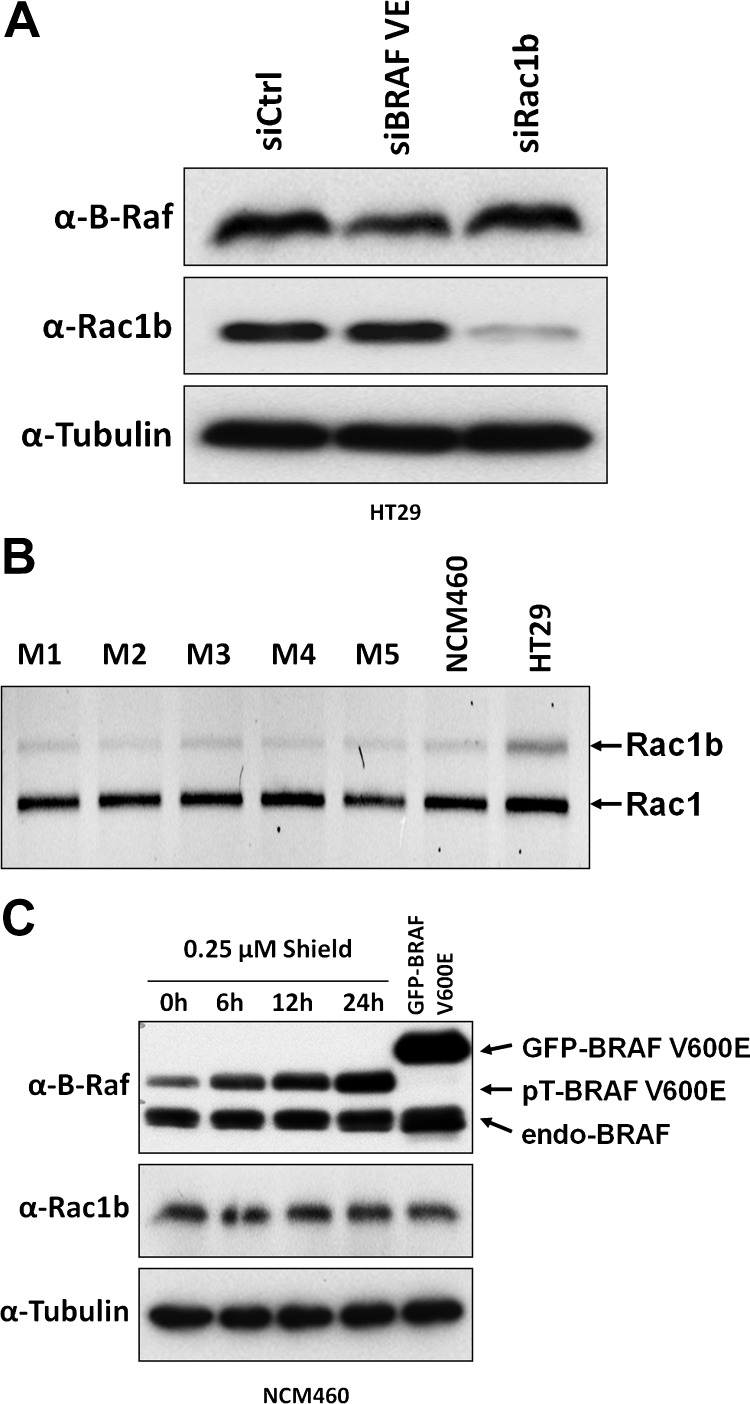

We previously found that most colorectal tumors carrying the BRAF-V600E mutation also show Rac1b overexpression and that Rac1b was required to sustain survival and tumorigenicity of colorectal tumor cells [9]. To understand how the overexpression of Rac1b was triggered in colorectal tumors, we asked whether mutant BRAF, which has been widely considered as the tumor-initiating event, was sufficient to cause Rac1b overexpression. For this, we first used HT29 tumor cells, which were previously identified as a model for the BRAF-V600E/Rac1b tumor type, and depleted expression of the mutant BRAF-V600E allele by RNA interference. We observed that under these conditions the expression levels of endogenous Rac1b remained unaffected (Figure 1A). Next, we overexpressed oncogenic BRAF-V600E in nontransformed human colonocyte NCM460 [21] that we found to express endogenous Rac1b at levels comparable to normal colon mucosa (Figure 1B); however, no evidence for an increase in Rac1b expression was observed (Figure 1C). Together, these data strongly suggest that the presence of mutant BRAF alone was not sufficient to induce overexpression of Rac1b and that BRAF mutation and Rac1b overexpression constitute two independent events in colorectal tumorigenesis.

Figure 1.

The presence of oncogenic BRAF is insufficient to increase Rac1b expression. (A) HT29 colon cancer cells, expressing one endogenous mutated BRAF-V600E allele and Rac1b, were transfected with either BRAF-V600E-specific, Rac1b-specific, or control siRNA oligonucleotides, as described [9]. Following 48 hours, the resulting expression levels of BRAF and Rac1b proteins were analyzed by Western blot. Note that specific reduction in the accumulation of the oncogenic BRAF variant had no effect on Rac1b levels. (B) NCM460 normal colonocytes present endogenous Rac1b mRNA levels comparable to that observed in five healthy human colonic mucosa (M) samples. (C) Inducible overexpression of BRAF-V600E in NCM460 cells did not induce any changes in Rac1b protein levels.

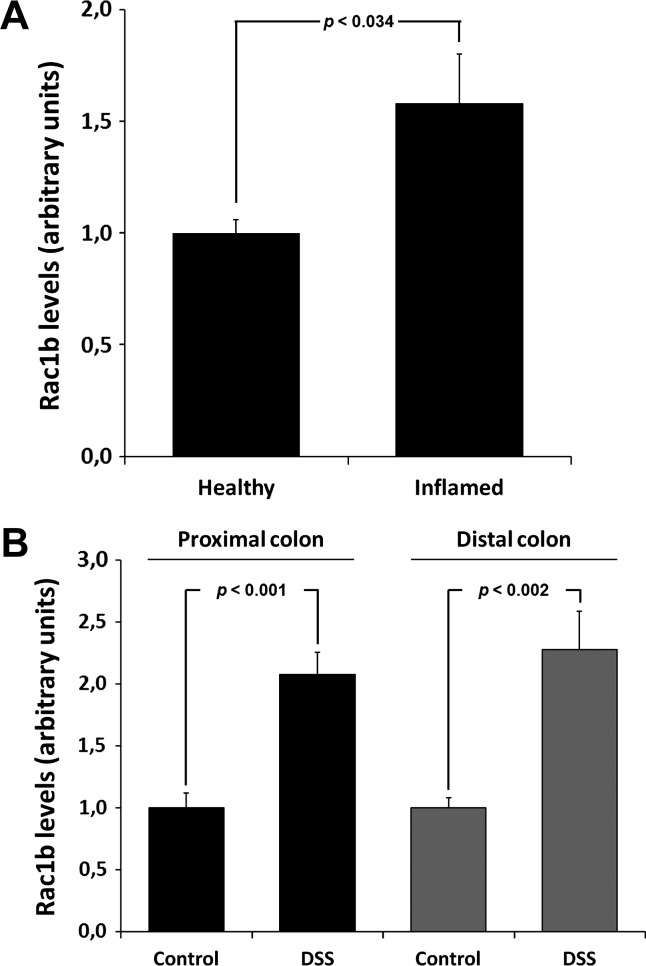

Pro-inflammatory Cues Are Associated with Rac1b Overexpression In Vivo

Another well-known factor promoting tumor cell progression is the surrounding tumor cell microenvironment [14–16]. Inflammation, for example, constitutes a persistent challenge of the mucosa tissue and has been associated with increased risk for CRC [22,23]. This prompted us to determine whether patients with inflammatory diseases of the colon would reveal altered Rac1b expression in the affected mucosa cells. RNA samples from surgery specimens of inflamed and control colonic mucosa from six affected individuals were analyzed by quantitative reverse transcription. PCR (qPCR) and showed a mean increase of 1.6-fold in Rac1b transcript (Figure 2A).

Figure 2.

An inflammatory microenvironment enhanced Rac1b expression in colonic cells. (A) The relative accumulation of Rac1b transcripts was evaluated by qPCR in RNA samples isolated from six surgical samples of inflamed colonic mucosa and in six samples of healthy colonic tissue. (B) Induction of Rac1b transcript accumulation during acute experimental colitis. Mice (n = 20) were treated with the polymer DSS to induce acute colonic inflammation, and Rac1b mRNA levels were determined by qPCR in both the proximal (A) and distal (B) colons of the DSS-treated and control mice.

This is comparable to the roughly two-fold increase in the alternative splicing of Rac1b that we observed in the colorectal cell line HT29 [9] and which was sufficient to yield a high level of active Rac1b protein due to the hyperactivation properties of this variant [10,24,25].

To further investigate the hypothesis that pro-inflammatory cues may promote Rac1b expression, a mouse model for experimentally induced colitis was employed. Mice were fed with the polymer DSS in drinking water for 5 days. After 2 days of recovery with water (acute colitis), animals were sacrificed. Expression of Rac1b in proximal and distal colon segments was analyzed by qPCR and revealed a more than two-fold up-regulation of the alternative transcript Rac1b (Figure 2B). These in vivo experiments strongly supported the possibility that the inflammatory process is involved in Rac1b overexpression.

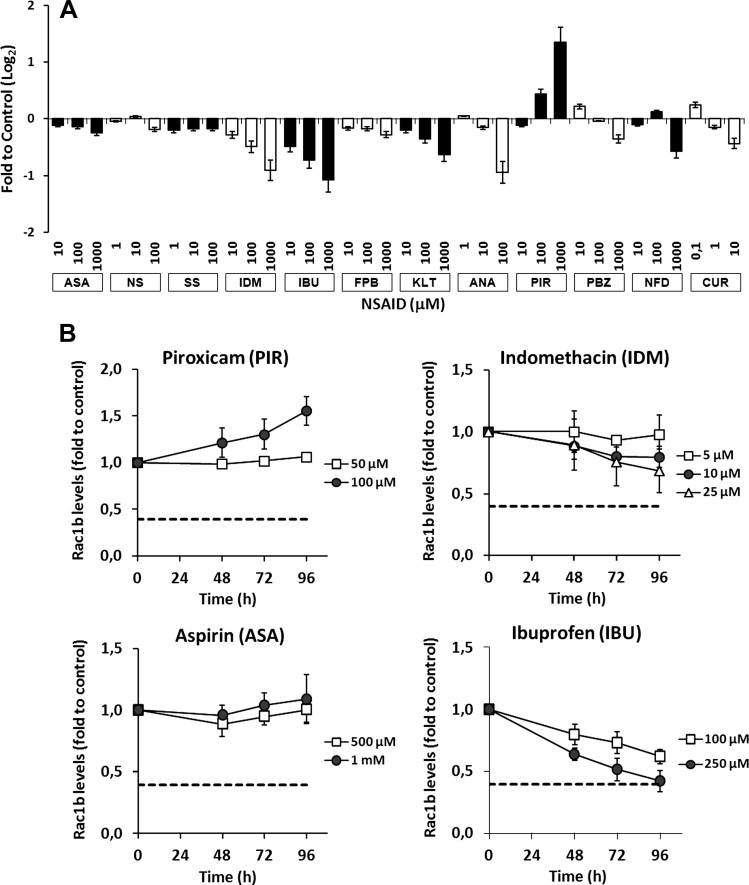

Ibuprofen Selectively Downregulates Rac1b Expression in CRC Cells

NSAIDs are widely used to treat inflammatory processes and their regular administration has been reported to delay sporadic colorectal tumor growth and to cause regression of polyps [18–20]. Because most of the anti-tumorigenic effects of NSAIDs were derived from in vitro studies using cancer cell lines, including HT29 [26–28], we tested whether a panel of NSAIDs and other compounds, previously described to have an ameliorative effect in CRC [26,27,29,30], would also affect Rac1b expression levels in these cells. Following 48 hours of treatment with a broad range of drug concentrations [26,29–32], only ibuprofen and indomethacin appeared to decrease Rac1b expression in a dose-dependent manner, whereas eight of the nine remaining drugs, including aspirin, had either no effect or lacked dose dependency (see Figure 3A). Unexpectedly, the drug piroxicam actually increased expression of the Rac1b transcript. Experiments were then repeated for four selected drugs using a time course and the concentration range found in the plasma of patients on continuous therapeutic regimens [29,31–33]. The results confirmed that at usual therapeutic concentrations only ibuprofen treatment caused a significant decrease in Rac1b expression in these cells (Figure 2B), reaching levels close to those found in healthy colon mucosa [9]. Aspirin had no effect on Rac1b expression and indomethacin failed to produce an effect as robust as ibuprofen. Notably, piroxicam reproducibly induced an increase in Rac1b (Figure 3B).

Figure 3.

Effect of NSAIDs on Rac1b mRNA levels in HT29 cells. (A) Cells were incubated for 48 hours with a panel of NSAIDs at the indicated concentrations and lysed for RNA extraction in order to analyze the respective Rac1b mRNA accumulation by qPCR. Abbreviations are given as follows: ASA = aspirin, IBU = ibuprofen, FBP = flurbiprofen, NPX = naproxen, SS = sulindac sulfide, IDM = indomethacin, KLT = Ketorolac, PIR = piroxicam, PBZ = phenylbutazone, NS = NS398, CUR = curcumin. (B) HT29 cells were incubated with clinically relevant concentrations described in patient plasma of either indomethacin, piroxicam, aspirin, or ibuprofen for up to 96 hours before Rac1b mRNA levels were determined by qPCR. Rac1b levels found in normal colon mucosa are shown as a dotted line.

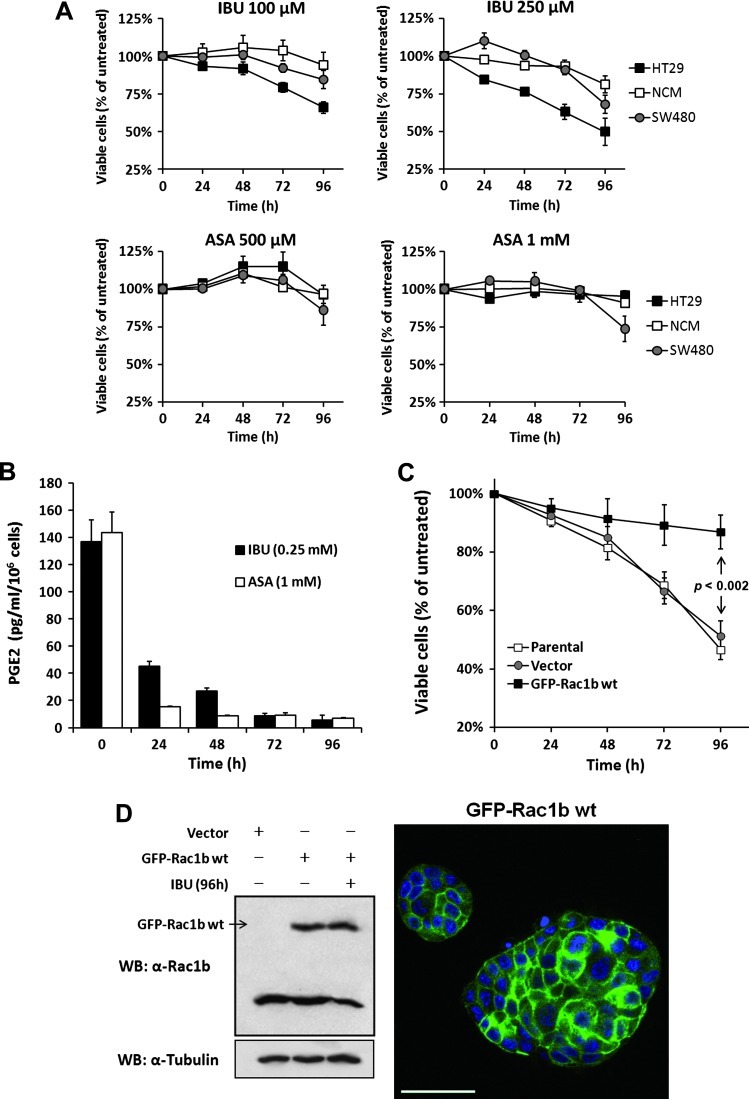

Ibuprofen Decreases the Viability of HT29 Cells through a COX-Independent Mechanism Requiring Rac1b Down-Regulation

Rac1b signaling has been previously described to sustain colorectal tumor cell survival [9,12]. We thus asked whether the changes in Rac1b expression were reflected by changes in HT29 cell viability. Indeed, cell treatment with ibuprofen, but not aspirin, significantly decreased the viability of HT29 cells by 50% (Figure 4A). We further reasoned that if ibuprofen treatment was reducing HT29 cell viability through Rac1b down-regulation, treatment should have no effect on SW480 cells that do not express this Rac1 variant. Indeed, at these low but therapeutically relevant concentrations, the viability of SW480 cells was unaffected. Only after 96 hours of treatment with the highest concentrations of aspirin or ibuprofen (Figure 4A) a reduction in cell viability was observed, compatible with a general cytotoxic effect at later time points. To test the effect of ibuprofen on normal colon cells, these experiments were also performed in nontransformed human colonocyte NCM460. Neither ibuprofen nor aspirin treatment had any significant effect on NCM460 viability (Figure 4A). These results suggested that ibuprofen specifically acts on Rac1b overexpressing cells.

Figure 4.

Effect of aspirin and ibuprofen on the viability of cultured colonic cells. (A) The effect on cell survival of the indicated drug treatments was determined for HT29 cells (Rac1b overexpression), SW480 cells (no endogenous Rac1b expression), and normal human colonocyte NCM460 (low-level Rac1b expression). Note that only ibuprofen affected cell viability and this occurred selectively in Rac1b overexpressing HT29 cells. (B) Comparison of the production of PGE2 in HT29 cells treated with either ibuprofen or aspirin, as an index of COX inhibition. (C) Survival of HT29 cells in the presence of ibuprofen following transfection with a control or a GFP-Rac1b expression vector. (D) Western blot analysis of endogenous and ectopic GFP-tagged Rac1b in the total protein extracts from HT29 cells treated with ibuprofen or untreated. A fluorescence microscopy image of a stable GFP-Rac1b expressing clone demonstrating plasma membrane localization of Rac1b, as previously described [10], is also shown.

The inhibition of cyclooxygenases (COXs), particularly of COX-2, which is frequently overexpressed by tumor cells [34], has been correlated with the anti-tumorigenic activity of NSAIDs. Moreover, HT29 cells have been reported to express higher levels of COX-2 than SW480 cells [35], and ibuprofen is a more potent COX-2 inhibitor than aspirin [36]. We therefore asked whether the observed effect of ibuprofen on HT29 cell viability correlated with COX-2 activity. COX-2 catalyzes the conversion of arachidonic acid to a number of prostaglandins including pro-tumorigenic PGE2 [34], which was therefore chosen to monitor COX-2 activity in HT29 cells treated with either ibuprofen or aspirin. We found that both drugs significantly inhibited PGE2 production just after 24 hours of treatment (Figure 4B). Thus, although the treatment conditions with either aspirin or ibuprofen yielded equivalent degrees of COX inhibition, only ibuprofen affected Rac1b expression levels and cell viability. These data suggested that the effect of ibuprofen on Rac1b is unrelated to COX activity.

To examine whether the effect of ibuprofen on HT29 cell viability is directly dependent on Rac1b, we generated HT29 cells that stably express either GFP alone (control) or an ectopic GFP-Rac1b cDNA. This way, ectopic GFP-Rac1b should bypass the inhibitory effect that ibuprofen had on expression of endogenous Rac1b, which is known to be regulated at the alternative splicing level. As shown in Figure 4C, this ectopic Rac1b protein clearly rescued the inhibitory effect of ibuprofen on cell viability, although in these cells ibuprofen still led to the reduction in endogenous Rac1b protein described above (Figure 4D). Together, these results strongly indicated that ibuprofen inhibits HT29 cell viability by directly interfering with Rac1b overexpression.

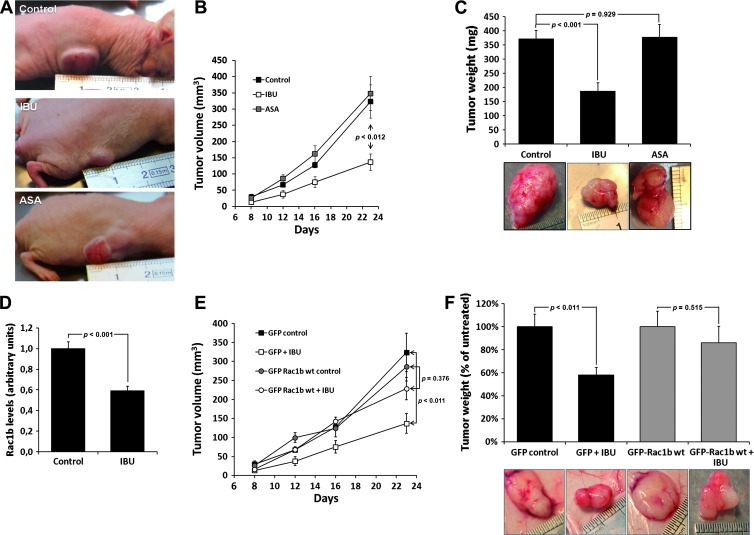

Ibuprofen Inhibits Rac1b-Dependent Tumor Growth of HT29 Xenografts

Encouraged by these observations, we next determined whether ibuprofen would also inhibit the growth of these BRAFV600E/Rac1b overexpression-positive tumor cells under in vivo conditions. Xenografts of HT29 cells were produced by subcutaneous injection into nude mice and animals fed with aspirin or ibuprofen in drinking water at doses adjusted for body mass from regular human posologies (1 mg/ml). Tumor growth was followed for 4 weeks (Figure 5, A and B), animals were then killed, the tumors resected and weighed, and RNA was extracted for qPCR analysis of Rac1b (Figure 5, C and D). Ibuprofen treatment clearly restrained tumor growth (P < .001), whereas aspirin produced no significant effect (P = .929). This correlated with a corresponding and significant decrease in Rac1b expression levels in the ibuprofen-treated tumors (Figure 5D). To further support the conclusion of a crucial role of Rac1b in this process, xenografts of the HT29 cells stably expressing GFP-Rac1b or GFP alone (control) were produced and the ibuprofen treatments were repeated. As shown in Figure 5, E and F, a clear reduction in the growth-inhibitory effect of ibuprofen was observed with the GFP Rac1b xenografts, whereas the GFP control cells responded to ibuprofen with a growth arrest equivalent to that observed for parentalHT29 cells. Together, these data show that ibuprofen, besides its general anti-inflammatory effect, targets the expression of alternative spliced Rac1b and this action is the underlying mechanism for the observed growth inhibition of xenograft-derived tumors.

igure 5.

Effect of anti-inflammatory drugs on HT29 xenograft growth in nude mice. HT29 cancer cells (2 x 106) were injected in flank of nude mice (n = 18) to generate xenograft tumors. Animals were divided into three groups and treated with either ibuprofen or aspirin (1 mg/ml) in drinking water, whereas the control group received water. (A) Representatives images of tumor xenograft at the time of sacrifice, and (B) graphic growth curve of the tumor volume. (C) The weight of the excised tumors was obtained and presented as means ± SEM. (D) Rac1b mRNA levels were determined by qPCR analysis under the indicated treatments. (E) HT29 GFP or HT29 GFP-Rac1b cells (2 x 106) were injected as subcutaneous xenografts into nude mice (n = 18), which were treated with ibuprofen or left untreated. The weight comparison and (F) representative images of the xenograft-derived tumors recovered after 28 days are shown. Note that ectopic Rac1b expression prevented ibuprofen from inhibiting tumor growth.

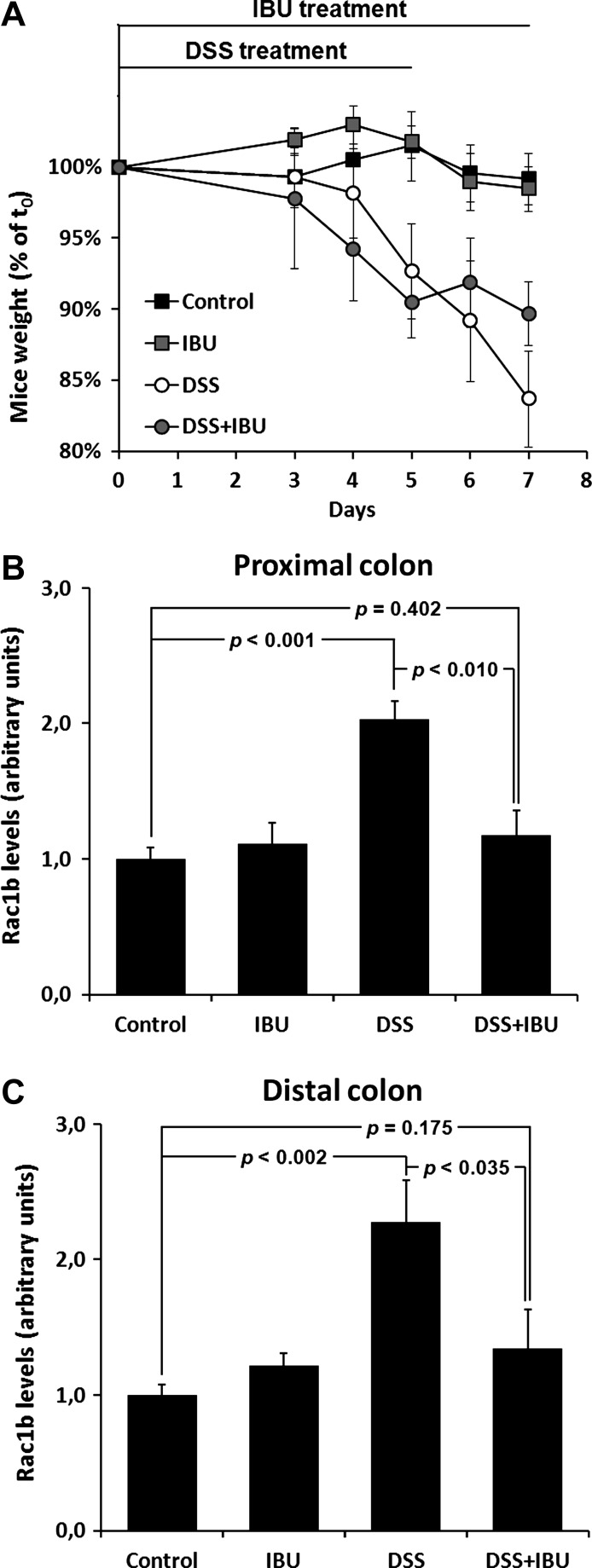

Ibuprofen Prevents the Acute Inflammation-Induced Rac1b Overexpression

As described above, we observed an increase in Rac1b levels in patients with colon inflammatory disorders and following acute colitis induction in mice. Because ibuprofen was able to inhibit Rac1b expression and tumor growth in HT29 xenografts, we investigated whether ibuprofen was also able to counteract the acute inflammation-induced increase in Rac1b expression. Mice were treated with DSS as described above either in the presence or absence of ibuprofen. As expected for an anti-inflammatory drug, ibuprofen treatment attenuated weight loss of DSS-treated mice (Figure 6A). In addition, the treatment strongly inhibited Rac1b elevation in both the proximal and distal mouse colons (Figure 6, B and C, respectively).

Figure 6.

Ibuprofen attenuates the weight loss and the increase in Rac1b expression during acute colitis in mice. Mice (n = 6) were treated with the polymer DSS to induce acute colitis in the absence or presence of ibuprofen (1 mg/ml) in the drinking water. The weight curves of treated mice during the 7-day period (A) are shown. Rac1b mRNA levels were determined by qPCR in both the proximal (B) and distal (C) colons isolated from sacrificed animals.

Discussion

Rac1b is an alternative splicing variant of the small GTPase Rac1 found overexpressed in colon [37], breast [38], and lung tumors [39–41]. In colon, Rac1b overexpression preferentially occurred in a specific subgroup of tumors that are characterized by mutation in the BRAF oncogene [9]. This is of interest because recent transgenic mouse models revealed that expression of mutant BRAF in either skin [42], lung [43], or colon [44] drives an initial proliferative response but then leads to oncogene-induced senescence. The observed overexpression of Rac1b in BRAF-mutated colon tumors thus represents one candidate mechanism involved in oncogene-induced senescence escape. Consistently, we previously described that the survival of representative tumor cells such as HT29 depends on both BRAF-V600E and Rac1b overexpression [9]. It remains, however, unclear how Rac1b expression is induced, in particular because the mere presence of mutant BRAF was insufficient to alter Rac1b expression levels (see Figure 1). Whereas in a mammary carcinoma cell model the activity of extracellular matrix metalloproteinase 3 was able to induce Rac1b [45], it is unknown whether this also applies to other cell types such as colon.

One major novel finding of this work is that colon inflammation can trigger increased Rac1b expression. This was observed during experimentally induced acute colitis in mice but also in surgical samples from patients with inflammatory diseases of the colon. These data suggest that stroma-derived signals can induce changes in the generation or stability of the alternative spliced Rac1b transcript in colonocytes.

The last decade has revealed numerous examples of cytokines produced by stromal fibroblasts or immune cells, including tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNFα), interleukins-1 (IL-1), IL-6, and IL-23, which stimulate tumor cell progression in a paracrine manner [15,17]. In addition, tumor cells produce cytokines to which stromal cells respond with the secretion of proteases, angiogenesis, or release of mitogenic factors that feedback on tumor cell survival. These latter mitogenic signals frequently activate NF-κB in the tumor cell [16,17], a pathway also activated downstream of Rac1b signaling [10,11]. Thus, stroma-derived signals may favor tumorigenesis of the mentioned subgroup of colorectal tumors through the switch in Rac1b expression in cancer cells, the subsequent NF-κB stimulation leading to increased cell survival. The molecular identity of such signals is currently being investigated, but preliminary data indicate that the overexpression of IL-8, a previously described marker of chronic colonic inflammation [46] and CRC progression [47], may be involved (data not shown). In this sense, our data indicate that the emergence of Rac1b overexpression may not be the consequence of a second mutational event in a BRAF mutant cell but rather a response of the initiated tumor cell to stroma-derived signals.

A second major finding of this work is that ibuprofen has a specific inhibitory effect on Rac1b overexpression. We found in cultured HT29 cells that Rac1b expression and, consequently, Rac1b-mediated tumor cell survival were significantly and selectively reduced upon incubation with ibuprofen but not with other commonly used NSAIDs, namely, aspirin. In contrast, the survival of SW480 cells that do not express Rac1b was not significantly affected under the same conditions (Figure 4A). Although inflammation is a complex process, these in vitro studies indicate that ibuprofen exerts a direct and specific action on Rac1b-positive CRC cells that is not activated by other NSAIDS such as aspirin. Consequently, ibuprofen was able to specifically inhibit the Rac1b-dependent growth of HT29 tumor xenografts. Moreover, this inhibitory effect of ibuprofen was rescued by constitutive overexpression of wild-type Rac1b in derivatives of HT29 cells. The HT29 cell line is a model for the specific subgroup of colorectal tumors characterized by mutation in the BRAF oncogene and Rac1b overexpression [9]. In these cells, aspirin had no effect on xenograft growth, although it has been clearly shown to inhibit the growth of other colon tumor cells, which mostly harbor other oncogenic mutations.

Ibuprofen shares with other NSAIDs such as aspirin the ability to inhibit the activity of COX-1 and COX-2 and thus to reduce the generation of pro-inflammatory stimuli. Consistently, we found that under the experimental conditions employed ibuprofen as well as aspirin inhibited COX activity; however, only ibuprofen affected Rac1b levels, demonstrating that its mechanism of action is COX-independent. Because we used therapeutically relevant ibuprofen concentrations that are comparable to those found in patient plasma, the observed reduction in Rac1b is not an unspecific off-target effect but rather an additional mode of action of ibuprofen. Indeed, several NSAIDs were described to have COX-independent mechanisms of action [28,48,49], but how ibuprofen inhibits Rac1b expression remains to be determined. Rac1b expression is most likely regulated at the alternative splicing level and so far no data were reported on any effect of ibuprofen on this process. In one case, ibuprofen was found to increase mRNA stability mediated through the p38 MAPK pathway [50]. Our results are in agreement with previous reports showing that ibuprofen treatment of colorectal tumor cells markedly decreased their viability, both in vitro and in vivo [51,52].

In this sense, the presented experimental data suggest potential clinical implications for our findings. First, the group of patients with proximal colorectal tumors of the serrated polyp type that usually contains oncogenic BRAF mutations is likely to benefit from adjuvant and preventive therapy with ibuprofen. This can be clearly deduced fromthe inhibitory effect on the HT29 xenograft. Second, feeding mice with ibuprofen reduced the experimental inflammation-mediated increase in Rac1b in their colon, suggesting a beneficial effect of ibuprofen in colon cancer chemoprevention, namely, by inhibiting the progression of BRAF-mutated tumor-initiated cells through Rac1b overexpression. It is important to note that previous analyses of inflammatory disease-associated colon tumors found BRAF mutation frequencies comparable to sporadic colon cancer, including the high prevalence in tumors with microsatellite instability [53,54].

Moreover, our findings indicate that the beneficial effect of NSAIDs in CRC may not rely solely on an anti-inflammatory response. Although aspirin has been successfully used to inhibit colon cancer growth on the one hand, it likely provides less prevention against the growth of serrated tumors than ibuprofen. However, the administration of some NSAIDs, such as piroxicam, may even promote this type of Rac1b-related tumor development. Thus, our data imply that the efficacy of NSAID treatment may show discrepancies depending on the subtype of the initiated tumor that is present.

Footnotes

This work was supported by the Fundaçaã Calouste Gulbenkian (grant 96495) and Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia, Portugal (grant PEst-OE/BIA/UI4046/2011 to the BioFIG Research Unit and contract Ciência2007 to P.M. Competing interests: None.

References

- 1.Fodde R, Smits R, Clevers H. APC, signal transduction and genetic instability in colorectal cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2001;1:55–67. doi: 10.1038/35094067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shen L, Toyota M, Kondo Y, Lin E, Zhang L, Guo Y, Hernandez NS, Chen X, Ahmed S, Konishi K, et al. Integrated genetic and epigenetic analysis identifies three different subclasses of colon cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:18654–18659. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0704652104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Snover DC, Jass JR, Fenoglio-Preiser C, Batts KP. Serrated polyps of the large intestine: a morphologic and molecular review of an evolving concept. Am J Clin Pathol. 2005;124:80–91. doi: 10.1309/V2EP-TPLJ-RB3F-GHJL. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Velho S, Moutinho C, Cirnes L, Albuquerque C, Hamelin R, Schmitt F, Carneiro F, Oliveira C, Seruca R. BRAF, KRAS and PIK3CA mutations in colorectal serrated polyps and cancer: primary or secondary genetic events in colorectal carcinogenesis? BMC Cancer. 2008;8:255. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-8-255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carr NJ, Mahajan H, Tan KL, Hawkins NJ, Ward RL. Serrated and non-serrated polyps of the colorectum: their prevalence in an unselected case series and correlation of BRAF mutation analysis with the diagnosis of sessile serrated adenoma. J Clin Pathol. 2009;62:516–518. doi: 10.1136/jcp.2008.061960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim KM, Lee EJ, Ha S, Kang SY, Jang KT, Park CK, Kim JY, Kim YH, Chang DK, Odze RD. Molecular features of colorectal hyperplastic polyps and sessile serrated adenoma/polyps from Korea. Am J Surg Pathol. 2011;35:1274–1286. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e318224cd2e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boparai KS, Dekker E, Polak MM, Musler AR, van Eeden S, van Noesel CJ. A serrated colorectal cancer pathway predominates over the classic WNT pathway in patients with hyperplastic polyposis syndrome. Am J Pathol. 2011;178:2700–2707. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2011.02.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Davies H, Bignell GR, Cox C, Stephens P, Edkins S, Clegg S, Teague J, Woffendin H, Garnett MJ, Bottomley W, et al. Mutations of the BRAF gene in human cancer. Nature. 2002;417:949–954. doi: 10.1038/nature00766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Matos P, Oliveira C, Velho S, Goncalves V, da Costa LT, Moyer MP, Seruca R, Jordan P. B-RafV600E cooperates with alternative spliced Rac1b to sustain colorectal cancer cell survival. Gastroenterology. 2008;135:899–906. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.05.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Matos P, Collard JG, Jordan P. Tumor-related alternatively spliced Rac1b is not regulated by Rho-GDP dissociation inhibitors and exhibits selective downstream signaling. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:50442–50448. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M308215200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Matos P, Jordan P. Expression of Rac1b stimulates NF-κB-mediated cell survival and G1/S-progression. Exp Cell Res. 2005;305:292–299. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2004.12.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Matos P, Jordan P. Increased Rac1b expression sustains colorectal tumor cell survival. Mol Cancer Res. 2008;6:1178–1184. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-08-0008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Seruca R, Velho S, Oliveira C, Leite M, Matos P, Jordan P. Unmasking the role of KRAS and BRAF pathways in MSI colorectal tumors. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;3:5–9. doi: 10.1586/17474124.3.1.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Joyce JA, Pollard JW. Microenvironmental regulation of metastasis. Nat Rev Cancer. 2009;9:239–252. doi: 10.1038/nrc2618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grivennikov SI, Greten FR, Karin M. Immunity, inflammation, and cancer. Cell. 2010;140:883–899. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.01.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Clevers H. At the crossroads of inflammation and cancer. Cell. 2004;118:671–674. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Aggarwal BB, Shishodia S, Sandur SK, Pandey MK, Sethi G. Inflammation and cancer: how hot is the link? Biochem Pharmacol. 2006;72:1605–1621. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2006.06.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Oshima M, Taketo MM. COX selectivity and animal models for colon cancer. Curr Pharm Des. 2002;8:1021–1034. doi: 10.2174/1381612023394953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rüegg C, Zaric J, Stupp R. Non steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and COX-2 inhibitors as anti-cancer therapeutics: hypes, hopes and reality. Ann Med. 2003;35:476–487. doi: 10.1080/07853890310017053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rao CV, Reddy BS. NSAIDs and chemoprevention. Curr Cancer Drug Targets. 2004;4:29–42. doi: 10.2174/1568009043481632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moyer MP, Manzano LA, Merriman RL, Stauffer JS, Tanzer LR. NCM460, a normal human colon mucosal epithelial cell line. In Vitro Cell Dev Biol Anim. 1996;32:315–317. doi: 10.1007/BF02722955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.O'Connor PM, Lapointe TK, Beck PL, Buret AG. Mechanisms by which inflammation may increase intestinal cancer risk in inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2010;16:1411–1420. doi: 10.1002/ibd.21217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ullman TA, Itzkowitz SH. Intestinal inflammation and cancer. Gastroenterology. 2011;140:1807–1816. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.01.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fiegen D, Haeusler LC, Blumenstein L, Herbrand U, Dvorsky R, Vetter IR, Ahmadian MR. Alternative splicing of Rac1 generates Rac1b, a self-activating GTPase. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:4743–4749. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M310281200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Singh A, Karnoub AE, Palmby TR, Lengyel E, Sondek J, Der JC. Rac1b, a tumor associated, constitutively active Rac1 splice variant, promotes cellular transformation. Oncogene. 2004;23:9369–9380. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hixson LJ, Alberts DS, Krutzsch M, Einsphar J, Brendel K, Gross PH, Paranka NS, Baier M, Emerson S, Pamukcu R, et al. Antiproliferative effect of nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs against human colon cancer cells. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 1994;3:433–438. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shiff SJ, Koutsos MI, Qiao L, Rigas B. Nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs inhibit the proliferation of colon adenocarcinoma cells: effects on cell cycle and apoptosis. Exp Cell Res. 1996;222:179–188. doi: 10.1006/excr.1996.0023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Smith ML, Hawcroft G, Hull MA. The effect of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs on human colorectal cancer cells: evidence of different mechanisms of action. Eur J Cancer. 2000;36:664–674. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(99)00333-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.John-Aryankalayil M, Palayoor ST, Cerna D, Falduto MT, Magnuson SR, Coleman CN. NS-398, ibuprofen, and cyclooxygenase-2RNA interference produce significantly different gene expression profiles in prostate cancer cells. Mol Cancer Ther. 2009;8:261–273. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-08-0928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Carroll RE, Benya RV, Turgeon DK, Vareed S, Neuman M, Rodriguez L, Kakarala M, Carpenter PM, McLaren C, Meyskens FL, Jr, et al. Phase IIa clinical trial of curcumin for the prevention of colorectal neoplasia. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 2011;4:354–364. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-10-0098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Famaey JP. Correlation plasma levels, NSAID and therapeutic response. Clin Rheumatol. 1985;4:124–132. doi: 10.1007/BF02032282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang D, Miller R, Zheng J, Hu C. Comparative population pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic analysis for piroxicam-beta-cyclodextrin and piroxicam. J Clin Pharmacol. 2000;40:1257–1266. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Owen SG, Roberts MS, Friesen WT, Francis HW. Salicylate pharmacokinetics in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1989;28:449–461. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.1989.tb03526.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang D, Dubois RN. The role of COX-2 in intestinal inflammation and colorectal cancer. Oncogene. 2010;29:781–788. doi: 10.1038/onc.2009.421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhang H, Ye Y, Bai Z, Wang S. The COX-2 selective inhibitor-independent COX-2 effect on colon carcinoma cells is associated with the Delta1/Notch1 pathway. Dig Dis Sci. 2008;53:2195–2203. doi: 10.1007/s10620-007-0139-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Noreen Y, Ringbom T, Perera P, Danielson H, Bohlin L. Development of a radiochemical cyclooxygenase-1 and -2 in vitro assay for identification of natural products as inhibitors of prostaglandin biosynthesis. J Nat Prod. 1998;61:2–7. doi: 10.1021/np970343j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jordan P, Brazao R, Boavida MG, Gespach C, Chastre E. Cloning of a novel human Rac1b splice variant with increased expression in colorectal tumors. Oncogene. 1999;18:6835–6839. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schnelzer A, Prechtel D, Knaus U, Dehne K, Gerhard M, Graeff H, Harbeck N, Schmitt M, Lengyel E. Rac1 in human breast cancer: overexpression, mutation analysis, and characterization of a new isoform, Rac1b. Oncogene. 2000;19:3013–3020. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhou C, Licciulli S, Avila JL, Cho M, Troutman S, Jiang P, Kossenkov AV, Showe LC, Liu Q, Vachani A, et al. The Rac1 splice form Rac1b promotes K-ras-induced lung tumorigenesis. Oncogene. doi: 10.1038/onc.2012.99. (in press) [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stallings-Mann ML, Waldmann J, Zhang Y, Miller E, Gauthier ML, Visscher DW, Downey GP, Radisky ES, Fields AP, Radisky DC. Matrix metalloproteinase induction of Rac1b, a key effector of lung cancer progression. Sci Transl Med. 2012;4(142):142ra95. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3004062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Liu J, Lee W, Jiang Z, Chen Z, Jhunjhunwala S, Haverty PM, Gnad F, Guan Y, Gilbert H, Stinson J, et al. Genome and transcriptome sequencing of lung cancers reveal diverse mutational and splicing events. Genome Res. 2012;22:2315–2327. doi: 10.1101/gr.140988.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pritchard C, Carragher L, Aldridge V, Giblett S, Jin H, Foster C, Andreadi C, Kamata T. Mouse models for BRAF-induced cancers. Biochem Soc Trans. 2007;35:1329–1333. doi: 10.1042/BST0351329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dankort D, Filenova E, Collado M, Serrano M, Jones K, McMahon M. A new mouse model to explore the initiation, progression, and therapy of BRAFV600E-induced lung tumors. Genes Dev. 2007;21:379–384. doi: 10.1101/gad.1516407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Carragher L, Snell K, Giblett S, Aldridge V, Patel B, Cook S, Winton D, Marais R, Pritchard C. V600EBraf induces gastrointestinal crypt senescence and promotes tumour progression through enhanced CpG methylation of p16INK4a. EMBO Mol Med. 2010;2:458–471. doi: 10.1002/emmm.201000099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Radisky DC, Levy DD, Littlepage LE, Liu H, Nelson CM, Fata JE, Leake D, Godden EL, Albertson DG, Nieto MA, et al. Rac1b and reactive oxygen species mediate MMP-3-induced EMT and genomic instability. Nature. 2005;436:123–127. doi: 10.1038/nature03688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Daig R, Andus T, Aschenbrenner E, Falk W, Scholmerich J, Gross V. Increased interleukin 8 expression in the colon mucosa of patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Gut. 1996;38:216–222. doi: 10.1136/gut.38.2.216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rubie C, Oliveira Frick V, Pfeil S, Wagner M, Kollmar O, Kopp B, Graber S, Rau BM, Schilling MK. Correlation of IL-8 with induction, progression and metastatic potential of colorectal cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:4996–5002. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v13.i37.4996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tegeder I, Pfeilschifter J, Geisslinger G. Cyclooxygenase-independent actions of cyclooxygenase inhibitors. FASEB J. 2001;15:2057–2072. doi: 10.1096/fj.01-0390rev. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.van Leeuwen JS, Unlu B, Vermeulen NP, Vos JC. Differential involvement of mitochondrial dysfunction, cytochrome P450 activity, and active transport in the toxicity of structurally related NSAIDs. Toxicol In Vitro. 2012;26:197–205. doi: 10.1016/j.tiv.2011.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Quann EJ, Khwaja F, Djakiew D. The p38 MAPK pathway mediates aryl propionic acid induced messenger rna stability of p75 NTR in prostate cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2007;67:11402–11410. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-1792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yao M, Zhou W, Sangha S, Albert A, Chang AJ, Liu TC, Wolfe MM. Effects of nonselective cyclooxygenase inhibition with low-dose ibuprofen on tumor growth, angiogenesis, metastasis, and survival in a mouse model of colorectal cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:1618–1628. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-1696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Janssen A, Maier TJ, Schiffmann S, Coste O, Seegel M, Geisslinger G, Grosch S. Evidence of COX-2 independent induction of apoptosis and cell cycle block in human colon carcinoma cells after S- or R-ibuprofen treatment. Eur J Pharmacol. 2006;540:24–33. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2006.04.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sanchez JA, Dejulius KL, Bronner M, Church JM, Kalady MF. Relative role of methylator and tumor suppressor pathways in ulcerative colitis-associated colon cancer. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2011;17:1966–1970. doi: 10.1002/ibd.21526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Svrcek M, El-Bchiri J, Chalastanis A, Capel E, Dumont S, Buhard O, Oliveira C, Seruca R, Bossard C, Mosnier JF, et al. Specific clinical and biological features characterize inflammatory bowel disease associated colorectal cancers showing microsatellite instability. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:4231–4238. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.10.9744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]