Abstract

Antiviral responses must be tightly regulated to rapidly defend against infection while minimizing inflammatory damage. Type 1 interferons (IFN-I) are crucial mediators of antiviral responses1 and their transcription is regulated by a variety of transcription factors2; principal amongst these is the family of interferon regulatory factors (IRFs)3. The IRF gene regulatory networks are complex and contain multiple feedback loops. The tools of systems biology are well suited to elucidate the complex interactions that give rise to precise coordination of the interferon response. Here we have used an unbiased systems approach to predict that a member of the forkhead family of transcription factors, FOXO3, is a negative regulator of a subset of antiviral genes. This prediction was validated using macrophages isolated from Foxo3-null mice. Genome-wide location analysis combined with gene deletion studies identified the Irf7 gene as a critical target of FOXO3. FOXO3 was identified as a negative regulator of Irf7 transcription and we have further demonstrated that FOXO3, IRF7 and IFN-I form a coherent feed-forward regulatory circuit. Our data suggest that the FOXO3-IRF7 regulatory circuit represents a novel mechanism for establishing the requisite set points in the interferon pathway that balances the beneficial effects and deleterious sequelae of the antiviral response.

Systems biology approaches were used to identify the gene regulatory circuits that control the anti-viral response. We combined gene expression analysis with transcription factor binding site motif scanning algorithms to infer a network of associations between transcription factors and target genes that were activated in macrophages by polyinosinic-polycytidylic acid (PIC), a widely used surrogate for dsRNA viruses that stimulates the interferon response4 (Supplementary Fig. 1 and Supplementary Table 1). Transcription factor binding site (TFBS) motifs for IRF, STAT and FOXO transcription factors were significantly over represented within cluster 2, which includes antiviral genes like Gbp2, Ccl5, Ifit1, Irf7 and Oasl1 (Supplementary Fig. 2 and Supplementary Tables 1 and 2). Although all FOXO transcription factors bind a common DNA element5, we decided to focus on FOXO3 since it was the sole member of the family that was significantly repressed after PIC stimulation of macrophages (Supplementary Table 3). Interestingly, the repression of Foxo3 transcription was mirrored by increased transcription of Irf5, Irf7, Irf8, Stat1, Stat2, Stat3, and Stat5a genes (Supplementary Fig. 3). This result suggested that Foxo3 might act as a repressor of the IRF and STAT TFs, master regulators of the IFN-I pathways.

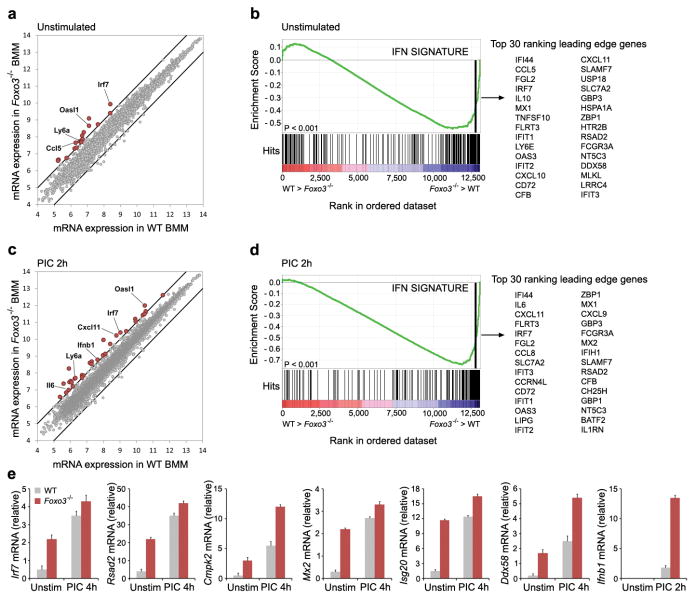

In order to investigate the role of FOXO3 in the regulation of the IFN-I pathway we examined the global gene expression profile in macrophages derived from Foxo3-null mice (Fig. 1). We detected significantly increased transcription of a subset of interferon-stimulated genes (ISG's) under basal conditions in Foxo3-null macrophages when compared to their wild type (WT) counterparts, suggesting that FOXO3 functions as a repressor of these genes (Fig. 1a, b and Supplementary Table 4). Stimulation of Foxo3-null macrophages with PIC further increased the levels of this subset of ISGs (Fig. 1c, d and Supplementary Table 5), and also revealed the transcription of additional ISGs (Fig. 1c, d and Supplementary Tables 4 and 5). The induction of these ISGs was validated by quantitative RT-PCR (Fig. 1e). Importantly, IFNB1 itself was super-induced in PIC-stimulated macrophages from Foxo3-null mice (Fig. 1c, e and Supplementary Fig. 4b), suggesting the possibility that the additional subset of ISGs were regulated by autocrine feedback. In order to distinguish whether the enhanced expression of ISGs in Foxo3-null macrophages was due to direct effects of the transcription factor, or due to autocrine effects of the cytokine we performed genome-wide chromatin immunoprecipitation/DNA sequencing (ChIP-Seq) analysis in unstimulated macrophages as well as in macrophages stimulated by PIC. Direct FOXO3 target genes included Cmpk2, Ddx58, Ifih1, Irf7, Mx2 and Rsad2, all of which have antiviral functions1, 6 (Fig. 2b, Supplementary Fig.5 and Supplementary Table 6).

Figure 1. FOXO3 is a negative regulator of the antiviral response.

a, Scatter plot comparing global gene expression profiles between unstimulated WT and Foxo3-null BMMs. The black lines indicate a two-fold cutoff for the difference in gene expression levels. Data represent the average of three independent experiments. mRNA expression levels are on the log2-scale. b, Gene-set enrichment analysis (GSEA) reveals the overrepresentation of IFN transcriptional signature genes in unstimulated Foxo3-null BMMs. Genes are ranked into an ordered list based on relative expression in wild type and Foxo3-null BMMs. The middle part of the plot shows the distribution of the genes in the IFN transcriptional signature gene set (“Hits”) against the ranked list of genes. The list on the right shows the top 30 genes in the leading edge subset. Data represent the average of three independent experiments. c, Global gene expression in PIC-stimulated WT and Foxo3-null BMMs was analyzed as in a. d, Gene-set enrichment analysis demonstrates up-regulation of IFN transcriptional signature in PIC-stimulated Foxo3-null BMMs. Data represent the average of three independent experiments. e, mRNA levels of Cmpk2, Ddx58, Irf7, Isg20, Mx2, Rsad2 and Ifnb1 in WT and Foxo3-null macrophages in the presence or absence of PIC stimulation. Data are representative of three experiments (average of three values ± standard error).

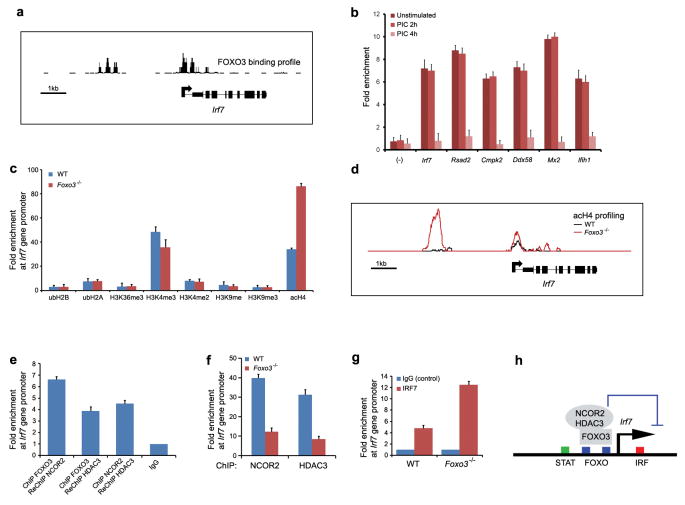

Figure 2. FOXO3 keeps the Irf7gene in check.

a, ChIP-Seq analysis demonstrates FOXO3 binding profile at Irf7 gene promoter in wild type BMMs. Data are representative of two experiments. b, ChIP of FOXO3 from unstimulated wild-type macrophages shows binding of FOXO3 to the promoters of the target genes. FOXO3 recruitment was not observed at control regions lacking FOXO binding sites (-). Data was normalized to IgG (negative control) and represent the average of three independent experiments ± standard error. c, ChIP analysis of histone acetylation, ubiquitination and methylation at Irf7 gene promoter in WT and Foxo3-null macrophages. Data represent the average of three independent experiments (± standard error). d, ChIP-Seq analysis demonstrates increased histone H4 acetylation levels in Foxo3-null cells. Data are representative of two experiments. e, FOXO3, NCOR2 and HDAC3 are present in the ternary complex at Irf7 promoter, as shown by ChIP-ReChIP assays in unstimulated BMMs. Data was compared to IgG and represent the average of three independent experiments ± standard error. f, ChIP analysis of NCOR2 and HDAC3 binding at Irf7 gene promoter in WT and Foxo3-null macrophages. Data represent the average of three independent experiments (± standard error). g, ChIP assay demonstrates increased recruitment of IRF7 at Irf7 gene promoter in Foxo3-null macrophages relative. Data was normalized to IgG and represent the average of three independent experiments ± standard error. h, A model depicting the mechanism of FOXO3-mediated repression of Irf7 gene. See text for details.

The Irf7 gene was of particular interest because of its critical role in the establishment of the antiviral response7, and we therefore examined the relationship between it and FOXO3 in more detail. Quantitative RT-PCR demonstrated that basal levels of Irf7 mRNA from Foxo3-null macrophages were 5.5-fold higher than those in WT cells, whereas PIC-induced Irf7 mRNA levels were similar in WT- and Foxo3-null cells (Fig. 1e). These results were validated by Western blot analysis (Supplementary Fig. 4a). Furthermore, deletion of FOXO3 TFBS in the Irf7 gene promoter resulted in an increased basal Irf7 promoter activity, and thus recapitulated the phenotype of Foxo3-null macrophages (Supplementary Fig. 6). These results suggest that FOXO3 functions as a negative regulator of basal Irf7 transcription.

In order to identify the mechanism by which FOXO3 suppresses the transcription of Irf7, we quantified histone acetylation, ubiquitination and methylation at Irf7 gene promoter in WT and Foxo3-null macrophages (Fig. 2c). Histone acetylation was significantly increased in Foxo3-null macrophages suggesting an epigenetic mechanism for FOXO3-mediated repression of the Irf7 gene (Fig. 2c, d). It is worth noting that enhanced histone acetylation correlates with increased transcription of Irf7 gene in activated macrophages (Supplementary Fig. 7). Histone acetylation is associated with an open chromatin structure that allows access of transcription factors to the DNA8; decreased acetylation results in the chromatin closing thereby impeding the binding of TFs to the promoter. A protein-protein interaction map9 predicted 8 histone deacetylases that might mediate this effect (data not shown), and direct biochemical approaches including co-immunoprecipitation and ChIP-ReChIP demonstrated the existence of a ternary complex consisting of FOXO3, nuclear co-repressor 2 (NCOR2) and histone deacetylase 3 (HDAC3) on the Irf7 promoter (Fig. 2e and Supplementary Fig. 8). A functional role for this complex is supported by the observation that treatment of macrophages with HDAC inhibitors, valproic acid (VPA) and apicidin10, results in increased levels of Irf7 mRNA (Supplementary Fig. 9). Most importantly, the binding of NCOR2 and HDAC3 to the Irf7 promoter was significantly reduced in Foxo3-null macrophages (Fig. 2f).

In order to ascertain the transcriptional circuitry underlying the regulation of the Irf7 gene we needed to identify all of the participating TFs. Motif scanning of the Irf7 gene promoter predicted STAT, IRF and FOXO binding sites (Supplementary Table 7). The potential presence of the IRF site raised the possibility of auto-regulation of the Irf7 gene by IRF7 itself, a contention supported by previous overexpression studies11. ChIP analysis validated the prediction that IRF7 binds to its own promoter (Fig. 2f), and importantly, FOXO3 restrained this interaction (Fig. 2g). Taken together, these results suggest a model in which a ternary complex of FOXO3, NCOR2 and HDAC3 facilitates a closed chromatin structure and limits IRF7 auto-regulation in macrophages under basal conditions (Fig. 2h).

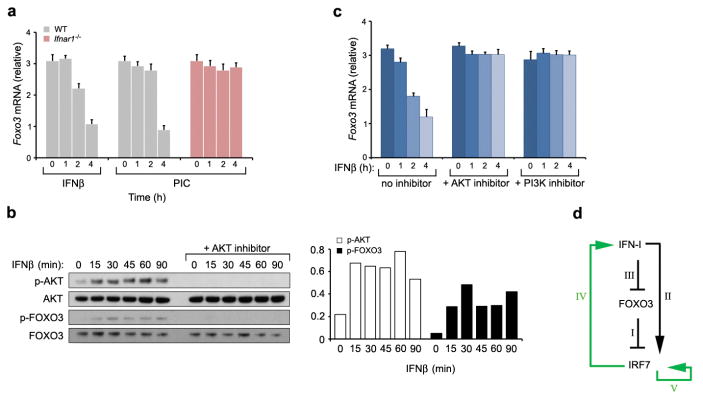

If the FOXO3, NCOR2 and HDAC3 ternary complex keeps basal transcription of Irf7 in check, how then does PIC-stimulation overcome this inhibition? We have observed that PIC-stimulation of macrophages results in the clearance of FOXO3, NCOR2 and HDAC3 from the Irf7 promoter, and that this clearance is temporally associated with PIC-induced Ifnb1 production (Fig. 2b, Supplementary Figs 8b and 10). The most plausible hypothesis is that PIC-stimulated IFN production regulates the association of FOXO3with the Irf7 promoter. This hypothesis was confirmed by the observation that stimulation of macrophages with IFNβ induced the phosphorylation of FOXO3, and this was accompanied by a decrease in Foxo3 mRNA and protein levels (Fig. 3a, b and Supplementary Fig. 10a). Furthermore, PIC-dependent repression of Foxo3 mRNA and protein levels did not occur in macrophages isolated from IFN-I receptor (IFNAR1) null mice (Fig. 3a and Supplementary Fig. 10b). The decrease in mRNA levels is explained by the observation that FOXO3 is required for its own transcription (Supplementary Fig. 11). The decrease in protein levels can be explained as follows. It has previously been shown that the serine–threonine kinase AKT phosphorylates FOXO3, leading to its translocation from the nucleus and its degradation in the cytosol12,13. We show here that stimulation of macrophages with IFNβ induced the phosphorylation of AKT that was accompanied by phosphorylation of FOXO3 at the Thr32 residue, a known AKT phosphorylation site (Fig. 3b). Furthermore, treatment of the cells with AKT inhibitor IV abrogated IFN-I-dependent AKT and FOXO3 phosphorylation and prevented IFN-I-mediated decrease in Foxo3 mRNA and protein levels (Fig. 3b, c and Supplementary Fig. 10c). Taken together, these results suggest that IFN-I activates the PI3K/AKT pathway, which in turn leads to FOXO3 degradation and to the cessation of Foxo3 transcription.

Figure 3. IFNβ represses FOXO3.

a, IFNβ- or PIC-stimulation of wild type macrophages was associated with a significant decrease in Foxo3 mRNA levels. PIC-induced decrease of Foxo3 mRNA levels was not observed in Ifnar1-null cells. Data are representative of three experiments (average of three values ± standard error). b, IFNβ induces activation of AKT in macrophages. Bar graph demonstrates densitometric quantification of phosphorylated AKT and FOXO3 protein levels. c, IFNβ-induced repression of Foxo3 mRNA levels in WT BMMs was measured in the presence and absence of PI3K and AKT inhibitors. Data are representative of three experiments (average of three values ± standard error). d, A model depicting FOXO3/IRF7/IFN-I regulatory circuit. See text for details.

FOXO3 has been shown to control CTLA-4 mediated regulation of IL-6, TNFα, MCP-1 and IFNγ in dendritic cells14,15,16, and this was proposed to occur via increased transcription of superoxide dismutase (SOD2)15. This mechanism does not appear to function in FOXO3-mediated repression of antiviral responses in macrophages since no differences in Sod2 mRNA levels in Foxo3-null macrophages were detected (data not shown). Taken together, the data suggest that FOXO3 acts in a coherent feed-forward loop, thereby modulating the antiviral response (Fig. 3d). Under basal conditions FOXO3 activity serves to limit Irf7 expression (I). IFN-I induces the transcription of Irf717; this represents the direct, rapid, arm of the feed-forward motif (II). Concomitantly, IFN-I inhibits the transcription of Foxo3 (III), which leads to the depletion of FOXO3 and alleviates the repression of Irf7. This represents the indirect, slow, arm of the feed-forward motif. Thus activation of both arms of the feed-forward motif is required to achieve the high level of IRF7 that is essential for the maximal antiviral response. In addition, this feed-forward pathway is aided by positive feedback regulation of IRF7 on IFN-I (IV) (Supplementary Fig. 12), and by positive auto-regulation of IRF7 (V). By limiting the transcription of Irf7, FOXO3 prevents leakiness of IRF7-induced genes in the absence of a viral infection. In addition, FOXO3 prevents spurious noise in the activity of IFN-I since it is capable of dampening the IRF7-induced positive feedback on IFN-I production.

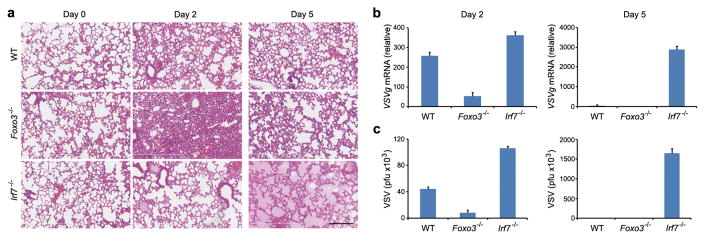

A fine balance exists between optimal immune clearance of a virus and the collateral damage that is inflicted on infected tissue during the host response. The FOXO3-IRF7 regulatory circuit represents an ideal mechanism for balancing host defense with inflammatory damage. Since we discovered and explored the FOXO3-IRF7 regulatory circuit in macrophages we needed an in vivo model system in which macrophages are the principal cells that produce IFN-I in a viral infection. The vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV)-lung infection model fully meets this criterion since it has been shown that alveolar macrophages are the primary interferon producers to intranasal infection, and that this response is cell intrinsic since depletion of alveolar macrophages completely ablates host defense to the virus18. Furthermore, VSV is an RNA virus19 which triggers similar pathways to PIC and which is controlled in an IRF7-dependent manner7. Intranasal infection of WT mice resulted in a low-grade inflammatory response by day two following infection that was accompanied by intermediate viral load (Fig. 4a-c). By day five the inflammatory response had resolved and viral titers were at basal levels (Fig. 4a-c). By contrast, Foxo3-null mice had significantly decreased viral loads at day two when compared with WT mice (Fig. 4b, c); however, this response was accompanied by significant lung pathology including pronounced neutrophil influx, hemorrhage and tissue damage (Fig. 4a and Supplementary Fig. 13). The virus was cleared by day five and lung inflammation was mostly resolved (Fig. 4a-c). Finally, viral replication was not controlled in Irf7-null mice (Fig. 4b, c). By day five these mice had developed severe pulmonary edema and were sacrificed (Fig. 4a).

Figure 4. Antiviral responses lead to increased lung injury in the absence of FOXO3 and IRF7.

a, H&E staining of lung tissue sections from wild-type, Foxo3-null and Irf7-null mice 0, 2 and 5 days after intranasal infection with VSV serotype Indiana 105 p.f.u. Data are from one experiment that is representative of three independent experiments (n=6 mice per group). Scale bar, 200μm. The viral burden in lungs was determined by measurement of VSVg mRNA levels in lung samples using quantitative real-time PCR assay (b) and by standard plaque assays in Vero cells (c). Data are representative of three experiments (average of three values ± standard error).

As discussed above, we chose the VSV model system since the anti-viral response is intrinsic to alveolar macrophages18. Consistent with this, we demonstrated that alveolar macrophages, isolated from VSV infected Foxo3-null animals, expressed considerably greater levels of mRNA encoding Irf7, Ifnb1, and other inflammatory cytokines including Ccl5, Ccl7 and Ccl12 than their WT counterparts (Supplementary Fig. 14 and data not shown). The increased basal levels of Irf7 mRNA in Foxo3-null alveolar macrophages further support a cell intrinsic role for FOXO3, although it is formally possible that other targets are also involved. A recent study demonstrated a cell intrinsic increase in CD8 T cell expansion in Foxo3-null mice20. We detected comparable T cell numbers in the lungs of VSV-infected WT and Foxo3-null mice, suggesting that T cells are not contributing to the phenotype (data not shown). The data presented above is consistent with the proposed role of the FOXO3/IRF7 circuit in host defense against viruses. The model predicts that FOXO3 suppresses the IRF7-dependent antiviral response in order to curb the collateral damage associated with host defense. We argue that the dynamic interplay between FOXO3, IRF7 and IFN-I, optimizes the antiviral response to achieve the appropriate balance between host defense and rampant inflammation.

Methods Summary

Cell culture

BMMs were isolated from C57BL/6, Foxo3-/- Irf7-/- and Ifnar1-/- mice essentially as described21. BMMs collected from femurs were plated on non–tissue culture–treated plastic in complete RPMI medium containing 10% (vol/vol) FBS (Hyclone Laboratories), 2 mM L-glutamine, 100 IU/ml of penicillin and 100 g/ml of streptomycin (all from Cellgro, Mediatech) and supplemented with recombinant human macrophage colony-stimulating factor (50 ng/ml; Peprotech). BMMs were treated for various length of time with high-purity LPS (10 ng/ml; Salmonella minnesota; List Biologicals), Pam3CSK4 (300ng/ml; EMC Microcollections), PIC (6μg/ml; Amersham), purified murine IFNβ (1.45×10-9 U/ml; PBL-interferon source), VPA (5mM; Sigma), Apicidin (2.5μM; Sigma), Ly294002 (50μM; Sigma) and AKT inhibitor IV (20μM; EMD Chemicals).

Microarrays and qRT-PCR

RNA isolation for transcriptome analysis of BMMs was performed using the Trizol reagent (Invitrogen). Gene expression profiling was performed using Affymetrix GeneChip Mouse Genome 430 2.0 and GeneChip Mouse Exon 1.0 ST arrays. Details of the analytical methods are provided in the Methods. For qRT-PCR, total RNA was reverse transcribed to complementary DNA and amplified using primers specific for murine transcripts. Expression values were calculated relative to the Eef1a1 mRNA transcripts.

ChIP-Seq and ChIP

For ChIP-Seq, immunoprecipitated DNA samples were sequenced on a Illumina HiSeq 2000 sequencing system and aligned using the ELAND software package (Illumina). Peaks identification was performed according to standard methods and is described in full in Methods. For quantitative ChIP, immunoprecipitated DNA samples were amplified with target promoter-specific primers.

Full Methods

Mice

C57BL/6 mice were obtained from Jackson Laboratories. Ifnar1-/-22 and Irf7-/-23 mice were obtained through the Swiss Immunological Mutant Mouse Repository (Zurich, Switzerland). Foxo3-/- mice in the FVB background24 were obtained from MMRRC and were backcrossed to C57BL/6 mice at least 5 times to generate congenic mice. C57BL/6 Foxo3+/- heterozygotes were intercrossed to generate Foxo3-/- mice. Mice were maintained at the animal facility of the Institute for Systems Biology and used at 8–12 weeks of age. All animals were housed and handled according to the approved protocols of University of Washington and Institute for Systems Biology's Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees.

Microarray analysis

Total RNA was extracted using a Trizol solution (Invitrogen) and overall RNA quality was analyzed with an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer. Sample mRNA was amplified, labeled and hybridized to GeneChip Mouse Genome 430 2.0 and GeneChip Mouse Exon 1.0 ST arrays according to the array manufacturer's instructions (Affymetrix). Probe intensities were measured and then processed with Affymetrix GeneChip operating software into image analysis (.CEL) files. The Affymetrix CEL files were normalized with robust multiarray average expression measure25 and baseline scaling using the software Bioconductor26, then exported to Matlab (MathWorks, Natick, MA) for further analysis. The raw data from Affymetrix GeneChip Mouse Genome 430 2.0 arrays are posted at ArrayExpress27 (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/arrayexpress/) with accession number E-TABM-310. Statistical analysis and data post-processing were performed with in-house developed functions in Matlab. For transcriptome analysis of TLR-induced responses in wild-type, Foxo3-/- and Irf7-/- BMMs, genes were selected for inclusion based on filtering for minimum log2 expression intensity (> 6) in at least one time point. Genes having differential expression (3-fold up- or down-regulated relative to wild-type unstimulated BMMs, in at least one time point) were selected for gene-clustering analysis to identify groups of genes that were co-expressed across the diverse set of TLR-stimulation experiments in wild-type BMMs, based on the assumption that genes within a cluster are likely to share common cis-regulatory elements28. Gene cluster analysis was performed using the K-means algorithm with squared Euclidean distance29, with 500 iterations. Expression measurements were transformed based on a single universal reference experiment (wild-type unstimulated BMMs) so that the transformed measurements would all lie between -1 and 1, with zero indicating the intensity in the reference experiment30.

Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA)

GSEA is an analytical tool for relating differentially regulated genes to transcriptional signatures and molecular pathways associated with known biological functions31. The statistical significance of the enrichment of known transcriptional signatures in a ranked list of genes was determined as described31. To assess the phenotypic association with FOXO3 deficiency, we used the list of genes that was ranked according to differential gene expression in Foxo3-/- and Foxo3+/+ BMMs. We used 1,294 gene sets from the Molecular Signature Database C2 version 2.5 and 24 custom gene sets including interferon-stimulated gene set (Supplementary Table 8).

Quantitative real-time PCR

For measurement of the expression of mRNA transcripts in BMMs, total RNA was collected by Trizol (Invitrogen). RNA was reverse-transcribed and analyzed by real-time PCR with TaqMan Gene Expression assays (Applied Biosystems). Data were acquired using a 7900HT Fast Real-Time PCR system (Applied Biosystems) and CF×96 Real-Time PCR Detection System (BioRad) and were normalized to the expression of Eef1a1 mRNA transcripts (encoding eukaryotic translation elongation factor 1 α1) in individual samples. Taqman primers are listed in Supplementary Table 9.

Western blots

Whole cell extracts of BMMs and immunoprecipitations were prepared as previously described32. Proteins were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and subsequently by Western blot using the following antibodies against: FOXO3 (75D8) (Cell Signaling); phospho-FOXO3 (T32) (Cell Signaling); beta-actin (ab20272) (Abcam); IRF7 (Invitrogen); phospho-AKT (T308) (C31e5e) and AKT (C67e7) (Cell Signaling). Densitometric quantification of western blot bands was performed using the NIH Image J software.

Elisa

BMMs were treated for various lengths of time with PIC (6μg/ml) and supernatants were harvested and analyzed by ELISA to measure production of IFNβ (PBL Biomedical Laboratories, Piscataway, NJ).

Motif scanning

Promoter sequences encompassing 3kb on either side of the transcriptional start site of a gene were scanned using the software tool MotifLocator33 as described21. Briefly, a total of 390 murine transcription factor matrices were obtained from the TRANSFAC database Professional version 9.334. These matrices were used to scan gene promoters where the individual matrix thresholds were set to report predictions above the percentile of 0.067%, i.e. an expectation of observing a prediction for a matrix every 1500bp. For a pair-wise enrichment of transcription factors (TFi) in promoter regions of a particular cluster of genes, we calculated a cumulative relative number of a TF pair as follows

| (1) |

where l is the gene cluster index (l ∈ {1, …,N}), N is the number of gene clusters, Nl is the number of genes in cluster l, is the number of predicted (P ≤ 10-3) TF binding site pairs for TFi and TFj. The enrichment score for a (TFi,TFj),Tnscription factor pair was calculated as follows

| (2) |

where k is the gene cluster index (k ∈ {1, …, N} [−i]) reflects a specific enrichment of the (TFi, TFj) transcription factor pair across gene clusters of interest.

ChIP-Seq and quantitative chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP)

For ChIP-Seq analysis formalin-fixed cells were sonicated and processed for immunoprecipitation essentially as described17. Briefly, 1.5 × 107 BMMs were crosslinked for 10 min. in 1% paraformaldehyde, washed and lysed. Chromatin was sheared by sonication (5 × 60 s at 30% maximum potency) to fragments of approximately 150bp. The sheared chromatin was incubated with anti-rabbit IgG Dynabeads (Invitrogen) pre-conjugated with antibodies to FOXO3 (H-144), HDAC3 (sc-11417) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology); IRF7 (Invitrogen), ubH2B (5546), ubH2A (8240), H3K36me3 (4909), H3K4me3 (9727) and H3K4me2 (9726) (Cell signaling); H3K9me (ab8896) and H3K9me3 (ab8898) (Abcam); NCOR2 (PA1-843) (Thermo Scientific) and acH4 (06-598) (Upstate), washed and eluted. The eluted chromatin was reverse-cross-linked, and DNA was purified using phenol/chloroform/isoamyl extraction. The purified ChIP DNA was prepared for sequencing with the Illumina ChIPSeq Sample Prep kit and processed in according to the manufacturer's protocol.

The ChIP-Seq data was aligned to the mouse genome (NCBI37/mm9; July 2007) using the ELAND alignment software (Illumina). Regions where the ChIP signals were enriched relative to the normal rabbit serum (NRS) control were determined as described35. We used a false discovery rate of less than 1%. For quantitative ChIP, immunoprecipitated DNA samples were amplified with target promoter–specific primers using Taqman quantitative PCR analysis. DNA region lacking FOXO binding sites served as a negative control36. Primers and probe sequences are listed in Supplementary Table 10.

Viral pathogenesis in mice

8–12 weeks old female mice were used in this study. Baseline body weights were measured before infection. Body weight and survival were monitored daily for 5 days and mice with body weight loss of more than 25% of pre-infection values were euthanized. For virological and pathological examinations, 6 mice per group were anaesthetized with ketamine/xylazine and intranasally infected with 105 p.f.u. (30μl) of VSV serotype Indiana (Mudd-Summers isolate), originally obtained from Dr. D. Kolakofsky (University of Geneva, Geneva, Switzerland). The virus titers in lungs were determined by standard plaque assays in Vero cells, as described37 and by measurement of VSVg mRNA levels in lung samples using quantitative real-time PCR assay. The primers used for the detection of VSVg mRNA were: Forward, 5′-CCTGGGTTTTTAGGAGCAAGATAG-3′; Reverse, 5′-AAGAAACCTGGAGCAAAATCAGA-3′ and FAM labeled probe, 5′-CGGGTCTTCCAATCTCTCCAGTGGATCT-3′

To assess viral pathogenesis, lungs of control and experimentally infected mice were processed for haematoxylin and eosin staining. In addition to determine the extent of neutrophil influx, the lung samples were processed for immunohistochemistry staining with antibodies against LY6B (Serotec).

Luciferase Assay

RAW 264.7 cells were transfected with Irf7- and Foxo3-promoter luciferase reporter constructs, and with constitutively active FOXO3 (FOXO3-TM) construct obtained from Addgene (plasmid 1788)12. Luciferase assays were performed as described38. All luciferase activity was normalized to the expression of the co-transfected Renilla luciferase.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Kathleen A. Kennedy and Jacques J. Peschon for discussions and critical reading of the manuscript; and Samuel A. Danziger, Tetyana Stolyar and Elena van Gaver for technical assistance. This work was supported by grants and contracts from the National Institutes of Health R01AI025032, R01AI032972, HHSN272200700038C, HHSN272200800058C and U54GM103511. Microarray and ChIP-Seq raw data have been submitted to the Gene Expression Omnibus under accession number GSE37052.

Footnotes

Supplementary Information is linked to the online version of the paper at www.nature.com/nature.

Author contributions V.L. designed experiments, did all experimental studies and drafted the manuscript; A.V.R. did data mining and microarray data analysis; A.E.L. provided technical assistance for experiments, including quantitative real-time PCR, ChIP and in vivo studies; F.S. did Western blots; A.C.H. and A.R. did ChIP-Seq data analysis; A.G.R. did genome-wide motif scanning analysis; A.B. did in vivo studies; J.D.A. supervised the computational analysis and A.A. supervised the study and wrote the manuscript.

Author information Reprints and permissions information is available at www.nature.com/reprints. The authors declare that they have no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Liu SY, Sanchez DJ, Cheng G. New developments in the induction and antiviral effectors of type I interferon. Curr Opin Immunol. 2011;23:57–64. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2010.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Panne D, Maniatis T, Harrison SC. An atomic model of the interferon-beta enhanceosome. Cell. 2007;129:1111–1123. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.05.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tamura T, Yanai H, Savitsky D, Taniguchi T. The IRF family transcription factors in immunity and oncogenesis. Annu Rev Immunol. 2008;26:535–584. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.26.021607.090400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barbalat R, Ewald SE, Mouchess ML, Barton GM. Nucleic Acid Recognition by the Innate Immune System. Annu Rev Immunol. 2011;29:185–214. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-031210-101340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Benayoun BA, Caburet S, Veitia RA. Forkhead transcription factors: key players in health and disease. Trends Genet. 2011;27:224–232. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2011.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schoggins JW, et al. A diverse range of gene products are effectors of the type I interferon antiviral response. Nature. 2011;472:481–485. doi: 10.1038/nature09907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Honda K, et al. IRF-7 is the master regulator of type-I interferon-dependent immune responses. Nature. 2005;434:772–777. doi: 10.1038/nature03464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shahbazian MD, Grunstein M. Functions of Site-Specific Histone Acetylation and Deacetylation. Annu Rev Biochem. 2007;76:75–100. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.76.052705.162114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Szklarczyk D, et al. The STRING database in 2011: functional interaction networks of proteins, globally integrated and scored. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:D561–D568. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Khan N, et al. Determination of the class and isoform selectivity of small-molecule histone deacetylase inhibitors. Biochem J. 2008;409:581–589. doi: 10.1042/BJ20070779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ning S, Huye LE, Pagano JS. Regulation of the transcriptional activity of the IRF7 promoter by a pathway independent of interferon signaling. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:12262–12270. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M404260200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brunet A, et al. Akt promotes cell survival by phosphorylating and inhibiting a Forkhead transcription factor. Cell. 1999;96:857–868. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80595-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Plas DR, Thompson CB. Akt activation promotes degradation of tuberin and FOXO3a via the proteasome. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:12361–12366. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M213069200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dejean AS, et al. Transcription factor Foxo3 controls the magnitude of T cell immune responses by modulating the function of dendritic cells. Nat Immunol. 2009;10:504–513. doi: 10.1038/ni.1729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fallarino F, et al. CTLA-4-Ig activates forkhead transcription factors and protects dendritic cells from oxidative stress in nonobese diabetic mice. J Exp Med. 2004;200:1051–1062. doi: 10.1084/jem.20040942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang ST, et al. RNA interference-mediated silencing of Foxo3 in antigen-presenting cells as a strategy for the enhancement of DNA vaccine potency. Gene Ther. 2011;18:372–383. doi: 10.1038/gt.2010.146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ning S, Pagano JS, Barber GN. IRF7: activation, regulation, modification and function. Genes Immun. doi: 10.1038/gene.2011.21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kumagai Y, et al. Alveolar macrophages are the primary interferon-alpha producer in pulmonary infection with RNA viruses. Immunity. 2007;27:240–252. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lyles DS, Rupprecht CE. In: Fields Virology. 5th. Howley PM, Knipe DM, editors. Vol. 1. 2007. pp. 1363–1408. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sullivan JA, Kim EH, Plisch EH, Peng SL, Suresh M. FOXO3 regulates CD8 T cell memory by T cell-intrinsic mechanisms. PLoS Pathog. 2012;8(2):e1002533. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gilchrist M, et al. Systems biology approaches identify ATF3 as a negative regulator of Toll-like receptor 4. Nature. 2006;441:173–178. doi: 10.1038/nature04768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Muller U, et al. Functional role of type I and type II interferons in antiviral defense. Science. 1994;264:1918–1921. doi: 10.1126/science.8009221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Honda K, et al. IRF-7 is the master regulator of type-I interferondependent immune responses. Nature. 2005;434:772–777. doi: 10.1038/nature03464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Castrillon DH, Miao L, Kollipara R, Horner JW, DePinho RA. Suppression of ovarian follicle activation in mice by the transcription factor Foxo3a. Science. 2003;301(5630):215–8. doi: 10.1126/science.1086336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Irizarry RA, et al. Exploration, normalization, and summaries of high density oligonucleotide array probe level data. Biostatistics. 2003;4:249–264. doi: 10.1093/biostatistics/4.2.249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gentleman RC, et al. Bioconductor: open software development for computational biology and bioinformatics. Genome Biol. 2004;5 doi: 10.1186/gb-2004-5-10-r80. research80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Parkinson H, et al. ArrayExpress--a public database of microarray experiments and gene expression profiles. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:D747–D750. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chiang DY, Brown PO, Eisen MB. Visualizing associations between genome sequences and gene expression data using genome-mean expression profiles. Bioinformatics. 2001;17:S49–S55. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/17.suppl_1.s49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dollar P. Piotr Dollar's Image and Video Toolbox for Matlab. San Diego, CA: University of California, San Diego; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ramsey SA, et al. Uncovering a macrophage transcriptional program by integrating evidence from motif scanning and expression dynamics. PLoS Comput Biol. 2008;21:e1000021. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Subramanian A, et al. Gene set enrichment analysis: a knowledge-based approach for interpreting genome-wide expression profiles. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:15545–15550. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506580102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gilchrist M, McCauley SD, Befus AD. Expression, localization, and regulation of NOS in human mast cell lines: effects on leukotriene production. Blood. 2004;104:462–469. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-08-2990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Thijs G, et al. INCLUSive: integrated clustering, upstream sequence retrieval and motif sampling. Bioinformatics. 2002;18:331–332. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/18.2.331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Biobase TRANSFAC Professional v9.3. Available at: http://www.biobase.de.

- 35.Ramsey SA, et al. Genome-wide histone acetylation data improve prediction of mammalian transcription factor binding sites. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:2071–2075. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Renault VM, et al. FoxO3 regulates neural stem cell homeostasis. Cell Stem Cell. 2009;6:527–539. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2009.09.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McCaren L, Holland JJ, Syverton JT. The mammalian cell–virus relationship. I. Attachment of poliovirus to cultivated cells of primate and non-primate origin. J Exp Med. 1959;109:475–485. doi: 10.1084/jem.109.5.475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Smith KD, et al. Toll-like receptor 5 recognizes a conserved site on flagellin required for protofilament formation and bacterial motility. Nat Immunol. 2003;4:1247–1253. doi: 10.1038/ni1011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.